Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate oxygen uptake kinetics and biomechanics during two and six minute walk tests in individuals with lower limb prosthesis (iLLA) and unimpaired persons. Participants performed both 2MWT and 6MWT, oxygen uptake (VO2), heart rate (HR) and temporal-spatial parameters were recorded. Repeated measures factorial ANOVAs analyzed differences between tests and groups, Alpha was set at 0.05. There were no significant differences in VO2 or HR between iLLA and unimpaired groups at any time point during either walk (p > 0.05), and neither group achieved steady state during the 2MWT, whereas steady-state HR appeared after minute 4 of the 6MWT in both groups. iLLA walked significantly less distance (p < 0.05) but had similar cadence and total steps during each test compared with unimpaired (p > 0.05). iLLA also had significantly greater stance ratios and shorter stride length compared with the unimpaired group (p < 0.05) and stride length was also shorter in iLLA during the 6MWT compared to the 2MWT (p < 0.05). The 2MWT is a strong predictor of 6MWT in the unimpaired group (r = 0.76, p = 0.001) and stronger in those using prostheses (r = 0.94, p = 0.001). Although 2MWT was a strong predictor of 6MWT performance in both groups, marked physiological and biomechanical differences were observed. Our findings do not support use of 2MWT as a proxy for 6MWT in lower limb prosthesis users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Timed walking tests evaluate mobility of individuals with lower limb amputation (iLLAs) quite well. The two-minute walk test (2MWT) and six-minute walk test (6MWT) evaluate maximum distance a person with lower limb prosthesis walks over two or six minutes respectively1,2,3. Although these tests may not be sensitive enough for assessing effect of prosthetic changes4,5, they are useful in determining mobility and perhaps functional capacity. Duration appears to be the distinguishing factor between the two tests, however, the increased duration of the 6MWT places additional physiological strain on the individual beyond that required for the 2MWT6. Still, some scholars have suggested using the 2MWT as a direct replacement of the 6MWT7. Although the 2MWT distance was predictive of the 6MWT distance (R2 = 0.91)7, the claim that the 2MWT can be used to “gain the same knowledge” as that of the 6MWT may be debatable7.

The 6MWT was originally developed as an alternative to the longer 12-min walk test which was an alternative to the Cooper 12-min run test8. The Cooper test was strongly correlated with maximal volume of oxygen uptake (VO2) max (0.89) and was recommended as a suitable alternative for measuring aerobic capacity. Thus, the American Thoracic Society guidelines for assessing cardiorespiratory endurance and aerobic capacity have recommended the 6MWT as a suitable noninvasive alternative of the aforementioned tests6,9. Hence, although the 2MWT is wonderful at testing walking function (mobility), it may not be long enough to determine functional capacity in iLLAs.

The functional physical capacity of prosthesis users is a reflection of their aerobic capacity to perform activities of daily living10. The simple act of walking is effective at eliciting an increase in the cardiovascular and skeletal muscle systems. Volume of oxygen uptake (VO2) measurement provides an index of a person’s ability to transport oxygen to the working muscle. Measurement of VO2 has helped to better understand human locomotion and gait pathology11,12,13,14,15,16, and there is a linear relationship between work rate and oxygen uptake17,18,19. However, similar to resting oxygen uptake20, people do not immediately achieve “steady-state” oxygen uptake when beginning to walk. During continuous exercise, “steady-state” occurs when the body’s demand for oxygen is met21. Steady-state assumes invariant VO2, carbon dioxide (CO2) and heart rate (bpm), and typically occurs within 3 min at a constant moderate work load22,23. Various factors, including delays in metabolism, age, fitness, disease, and familiarity with testing may prolong attainment of steady-state oxygen uptake24. Hence, temporal dynamics of VO2 during walking tests may offer an index of a person’s fitness level.

Functional (aerobic) capacity is typically measured through a staged VO2 max test19. However, the test is physiologically demanding and necessitates costly equipment. Of practical timed walking tests, the 6MWT is a validated alternative assessment of functional capacity. The test is correlated with VO2 max in a variety of populations25,26,27, and has been used to determine functional capacity of iLLAs28,29. To our knowledge, comparison of VO2 kinetics of prosthesis users during the 2MWT and 6MWT has yet to be explored. A better understanding of oxygen uptake dynamics may better distinguish the two tests from one another, and elucidate steady-state VO2 dynamics in these individuals. Therefore, this study was undertaken to evaluate the oxygen uptake kinetics during the two and six minute walk tests in iLLAs. In addition, we evaluated oxygen uptake kinetics during tests between amputee and unimpaired persons. This was done to examine if prosthesis use would increase time to steady state.

Methods

Participants

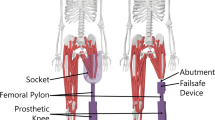

The study was approved by the Texas A&M University San Antonio Institutional Review Board (Log # 2021-38) with participants signing an informed consent form prior to study commencement. All procedures were performed in accordance with university guidelines, regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. Twenty-two lower limb prosthesis users (iLLA) and 17 unimpaired persons participated in this study (Table 1). The selection criteria included people with a lower limb amputation who could ambulate with their prosthesis without an assistive device, and excluded those who might be pregnant. All participants were asked to not eat a heavy meal four hours prior to testing, not to exercise, and maintain hydration prior to data collection. Height was measured wearing prostheses without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Seca® 213, Hamburg, Germany). Body mass was then measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (BOD POD®, COSMED, USA Inc., Concord, CA, USA). Body mass index was determined by mass divided by stature squared (kg/m2). All measurements were carried out according to manufacturer instructions.

Testing protocol

Each participant reported to the lab and were counter-balanced to first perform either a 2MWT or 6MWT, and within one week return to the lab to perform the other. Participants were instructed on the procedures for the walk test on each the testing day. They were told to walk as fast as possible in a safe manner while covering as much ground as possible. Participants were told they were permitted to stop but that time would continue and that they were to resume when able to do so. At the end of the walk, they were instructed to stop as quickly as possible. Participants were fitted with a Polar heart rate monitor chest strap (Polar, Kempele, Finland) to measure heart rate and a Cosmed K5 portable metabolic analyzer (COSMED, Rome, Italy), which was calibrated following manufacturer’s guidelines.

Participants were also fitted with Opal wearable triaxial Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) (Clario APDM, Philadelphia, PA) on each foot and ankle, as well as the lumbar and chest to collect cadence, gait speed, stance ratio, and stride length30,31,32,33. These data were collected at 128 Hz and calibration was performed for each participant prior to data collection.

Participants sat for three minutes while resting heart rate (HR) and oxygen consumption (VO2) was collected. After the three minutes, participants stood behind a start line, with the metabolic analyzer marked to indicate the start of the walk. Two investigators followed the participant to avoid pacing, one keeping time and filming (to later manually count steps with a hand tally counter) and the other with a measuring wheel to mark distance at 1 and 2 min of the 2 min walk, and 2 and 6 min of the 6 min walk. Participants walked along a flat, indoor level floor with a right turn approximately every 50 m for either two or six minutes depending on the test. The metabolic analyzer was marked to indicate the end of the walk, and a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) (Borg’s 6–20 scale) was recorded34. Distance walked was recorded and metabolic data was analyzed OMNIA software (COSMED, Rome, Italy). Gait data was analyzed using Mobility Lab software (Clario APDM, Philadelphia, PA) interfaced with the Opal sensors.

Statistical analysis

A 2 (group) by 2 (walk test) by 3 (time point) factorial ANOVA was used to identify differences in VO2 as well as in HR at rest, 1-min, and 2-min of each walking test. To evaluate steady state in the 6-min test, 2 (group) × 6 (time point) factorial ANOVAs with repeated measures on the second factor were used to explore differences in VO2 and in HR at minutes 1 through 6. Differences in steps taken and for distance walked at 1 min and 2 min of each walking test, as well as between groups at minute 6, were analyzed with a 2 (group) by 2 (walk test) by 4 (time point) factorial ANOVA. Differences in cadence, gait speed, stance ratio, and stride length of each walking test were analyzed with a 2 (group) by 2 (walk test) factorial ANOVA. Bonferroni technique was applied when examining pairwise comparisons. Values are expressed as means (m) ± standard deviations (sd). Pearson’s correlations were used to establish the relationship between the 2MWT and 6MWT, and regression analysis was used to assess the predictability of the 6MWT from the 2MWT. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all tests.

Results

VO 2 at rest, minute 1, and minute 2 of each walking test

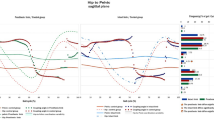

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.014, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. No significant interaction was evident for group and walk (F(2.37, 75.79) = 2.21, p = 0.107, ηp2 = 0.065), however, there was a main effect of time (F(2.37, 75.79) = 136.6, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.810), such that VO2 of iLLAs during the 2MWT increased from minute 1 (5.9 ± 1.8 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (10.6 ± 3.2 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001) as well as during the 6MWT from minute 1 (5.8 ± 2.1 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (10.6 ± 2.9 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001). These same trends occurred in the unimpaired group, with VO2 significantly increasing during the 2MWT from minute 1 (5.2 ± 1.4 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (11.9 ± 3.1 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001), and during the 6MWT from minute 1 (5.2 ± 1.1 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (12.2 ± 3.9 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001), Fig. 1.

While there were no significant differences in oxygen consumption (VO2) between prosthesis users and unimpaired groups at any time point (p > 0.05), VO2 increased significantly in both groups from rest, to minute 1, and to minute 2 (p < 0.001) during both walking tests. Note: 2MWT: 2 minute walk test, 6MWT: 6 minute walk test.

There were no significant differences in VO2 between groups at rest (p = 0.092), at 1 min (p = 0.240), and at 2 min (p = 0.265) during the 2MWT. Non-significant findings were also evident for VO2 during the 6MWT at rest (p = 0.938), at 1 min (p = 0.312), and at 2 min (p = 0.190), Fig. 1.

There was no significant difference in VO2 of those with prothesis between walking tests at rest (p = 1.0), at 1 min (p = 1.0), and at 2 min (p = 1.0), or VO2 of the unimpaired group at rest (p = 0.704), at 1 min (p = 1.0), and at 2 min (p = 1.0), Fig. 1.

HR at rest, minute 1, and minute 2 of each walking test

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.041, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. While there was no significant interaction for group and walk (F(2.26, 63.28) = 0.376, p = 0.714, ηp2 = 0.013), there was a main effect of time (F(2.26, 63.28) = 105.19, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.796). Following the same trends in VO2, there was a significant difference in HR of iLLA during the 2MWT between minutes 1 (107.7 ± 15.9) and 2 (115.7 ± 22.1) (p = 0.001) as well as during the 6MWT between minutes 1 (105.3 ± 14.4) and 2 (112.8 ± 16.9) (p = 0.001). This occurred similarly in the unimpaired group, with HR significantly increasing during the 2MWT from minute 1 (97.5 ± 11.8) to minute 2 (105.9 ± 13.7) (p = 0.002), and during the 6MWT from minute 1 (97.9 ± 11.2) to minute 2 (107.2 ± 13.6) (p = 0.001), Fig. 2.

While there were no significant differences in heart rate (HR) between prosthesis users and unimpaired groups at any time point (p > 0.05), HR increased significantly in both groups from rest, to minute 1, and to minute 2 (p < 0.001) during both walking tests. Note: 2MWT: 2 minute walk test, 6MWT: 6 minute walk test.

There were no significant differences in HR between groups at rest (p = 0.0107), at 1 min (p = 0.071), and at 2 min (p = 0.149) during the 2MWT. Non-significant findings were also evident for HR during the 6MWT at rest (p = 0.053), at 1 min (p = 0.127), and at 2 min (p = 0.330), Fig. 2.

There was also no significant difference in HR of those with prosthesis between walking tests at rest (p = 1.0), at 1 min (p = 1.0), and at 2 min (p = 1.0), or in HR of the unimpaired group at rest (p = 1.0), at 1 min (p = 1.0), and at 2 min (p = 1.0), Fig. 2.

VO2 during minutes 1 through 6 of the 6MWT

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.007, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. There was a significant interaction for group and time (F(1.67, 53.49) = 4.30, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.118), where VO2 in iLLA increased from minute 1 (5.8 ± 2.1 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (10.6 ± 2.9 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001), and from minute 2 to minute 3 (12.7 ± 3.3 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001). This was also evident in the unimpaired group from minute 1 (5.2 ± 1.1 ml/kg/min) to minute 2 (12.2 ± 3.9 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001), and from minute 2 to minute 3 (14.7 ± 3.7 ml/kg/min) (p = 0.001). The only other significant difference in time point was between minute 3 and minute 5 (15.8 ± 4.3 ml/kg/min) of the unimpaired, p = 0.038, Fig. 3.

There was a significant increase in VO2 of both groups from minute 1 to minute 2, and from minute 2 to minute 3 (*p > 0.05). VO2 in minute 5 was also significantly higher than minute 3, but only in the unimpaired group (†p > 0.05). No significant difference in VO2 existed between groups at any time point (p > 0.05). Note: 6MWT: 6 minute walk test.

There were no significant differences in VO2 between groups at any of the time points (p > 0.05), Fig. 3.

HR during minutes 1 through 6 of the 6MWT

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.004, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. There was no significant interaction for group and time (F(1.51, 45.50) = 0.361, p = 0.640, ηp2 = 0.012), however, HR in iLLA increased from minute 1 (104.3 ± 13.9 b/min) to minute 2 (111.4 ± 16.3 b/min) (p = 0.001), from minute 2 to minute 3 (114.9 ± 17.7 b/min) (p = 0.007), and from minute 3 to minute 4 (117.2 ± 17.9 b/min) (p = 0.002). This same tend followed with the unimpaired group, with significant increases from minute 1 (97.9 ± 11.2 b/min) to minute 2 (107.2 ± 13.6 b/min) (p = 0.001), from minute 2 to minute 3 (110.3 ± 15.3 b/min) (p = 0.032), and from minute 3 to minute 4 (112.7 ± 16.6 b/min) (p = 0.001), Fig. 4.

There was a significant increase in HR of both groups from minute 1 to minute 2, from minute 2 to minute 3, and from minute 3 to minute 4 (*p > 0.05). No significant difference in HR existed between prosthesis users and unimpaired persons at any time point (p > 0.05). Note: 6MWT: 6 minute walk test.

There were no significant differences in HR between groups at any of the time points (p > 0.05), Fig. 4.

Differences in steps taken and distance walked

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.021, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. There was no significant interaction with steps taken between groups (F(1.12, 34.98) = 2.08, p = 0.156, ηp2 = 0.063). There were no significant differences between groups in steps taken at any of the time points during each walk test (p > 0.05), Fig. 5.

Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(14) = 0.002, p = 0.001, thus the Greenhouse–Geisser was used for the critical F. There was a significant interaction with distance between groups (F(1.05, 33.65) = 6.44, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.168). Those with prosthesis walked significantly less distance compared to the unimpaired group at minute 1 (81.3 ± 20.2 m and 94.2 ± 12.2 m, respectfully, p = 0.030) and 2 (164.9 ± 41.1 m and 190.7 ± 23.5 m, respectfully, p = 0.031) of the 2MWT, as well as minute 2 (159.8 ± 38.2 m and 192.3 ± 23.5 m, respectfully, p = 0.005) and minute 6 (480.0 ± 120.6 m and 574.9 ± 87.5 m, respectfully, p = 0.013) of the 6MWT, Fig. 6.

There were no significant differences in distance walked at the 2 min time point between walking tests in those with amputations (p = 0.319) and in those without amputations (p = 1.0).

Differences in cadence and gait speed

There was no significant interaction with cadence between groups (F(1, 32) = 2.81, p = 0.103, ηp2 = 0.081), nor were there main effects for group (p > 0.05) or time (p > 0.05). Both groups had similar cadence during each test, Fig. 7.

There was also no significant interaction with gait speed between groups (F(1, 32) = 3.74, p = 0.062, ηp2 = 0.105); however, the unimpaired group walked significantly faster (1.50 ± 0.16 m/s) than iLLA (1.23 ± 0.31 m/s) during the 6MWT (p = 0.005), but not the 2MWT.No significant differences in gait speed were evident in unimpaired group between walking tests (p = 0.068), nor for iLLA (p = 0.402), Fig. 8.

Differences in stance ratio and stride length

There was no significant interaction with stance ratio between groups (F(1, 32) = 1.17, p = 0.286, ηp2 = 0.036), however, the unimpaired group had significantly lower stance ratio (59.0 ± 2.0% of ground contact time) compared to iLLA (60.9 ± 2.1% of ground contact time) during the 2MWT (p = 0.013) as well as the 6MWT (59.0 ± 1.8 and 61.5 ± 2.2% of ground contact time, respectively, p = 0.002). There were no significant differences in stance ratio of the unimpaired group between walking tests (p = 0.851), nor for iLLA (p = 0.094), Fig. 9.

A significant interaction between group and stride length existed (F(1, 32) = 4.46, p = 0.042, ηp2 = 0.123) such that the unimpaired group had significantly longer strides (1.44 ± 0.11 m) than iLLA (1.26 ± 0.25 m) during the 2MWT (p = 0.013). This same trend was evident during the 6MWT (1.46 ± 0.11 m and 1.23 ± 0.26 m respectively, p = 0.003). While there were no significant differences in stride length of the unimpaired group between the two walking tests (p = 0.355), iLLA had significantly longer strides during the 2MWT compared to the 6MWT, p = 0.048 (Fig. 10).

Those wearing prosthesis had significantly shorter stride length compared to the unimpaired group during the 2 min (*p = 0.013) and 6 min walk (†p = 0.003). Furthermore, prosthesis wearers had significantly shorter stride length during the 6 min walk compared to the 2 min walk (‡p = 0.048). Note: 2MWT: 2 minute walk test, 6MWT: 6 minute walk test.

While the relationship between the distance walked between the 2MWT and the 6MWT was strong and significant in unimpaired participants (r(15) = 0.76, p = 0.001), it was much stronger in iLLAs (r(15) = 0.94, p = 0.001) (Fig. 11). Simple regression analysis for unimpaired was significant (p = 0.001) with a resulting equation of predicted 6MWT distance = 21.6 + (2MWT distance * 2.9), with an SEE of 58.2 m and a mean absolute error of 35.7 ± 42.7 m. The simple regression equation for iLLAs was also significant (p = 0.001) and is as follows: predicted 6MWT distance = 27.0 + (2MWT distance * 2.7), with an SEE of 43.2 m and a mean absolute error of 33.4 ± 26.6 m.

Discussion

This study compared metabolic and biomechanical dynamics of lower limb prosthesis users and unimpaired persons in two widely used walking outcome measures. Neither iLLAs users nor unimpaired persons achieved steady state oxygen uptake during the 2MWT nor during the first two minutes of the 6MWT. This was evident from significant differences in oxygen uptake during the first two minutes of both tests. There were no significant differences in oxygen uptake at any time point between iLLAs and unimpaired persons during the 2MWT. Based on these results, it is clear that 2MWT was not long enough for either group to have reached a metabolic steady state. Similarly, during the 6MWT both groups exhibited significant increases in VO2 from minutes 1 to 2, but also minutes 2 to 3. Prosthesis users achieved steady state oxygen uptake after 3 min, however, unimpaired persons had significantly different VO2 from minute 3 to 5. Although prosthesis users had reduced VO2 during the 6MWT, these differences were not significant. Others have also observed no differences in VO2 between iLLAs and unimpaired persons during overground walking35,36. Perhaps a higher exercise intensity or work load may have elicited a higher physiological demand resulting in differences in VO2. This was the case when iLLAs and unimpaired controls carried a 32.7 kg external load, with iLLAs increasing their VO2 compared to unimpaired controls37.

Heart rate responses followed a similar trend to VO2 data. Heart rates differed significantly between the first two minutes of the 2 and 6MWT for both iLLAs and unimpaired persons. Prosthesis users had significantly higher HR at minute 1 and 2 compared to unimpaired persons during the 2MWT. Although heart rate and VO2 have a linear relationship18, internal factors (i.e., fitness, mood) and external factors (i.e., environment, hydration) can influence HR response in a highly variable manner38. This may explain why although a plateau in VO2 was observed for iLLAs midway through the 6MWT, heart rates continued to increase significantly even at minute 4. This trend was also observed in unimpaired persons. When comparing groups, although HR was higher in iLLAs, differences were not significant. Others have also observed increased heart rates in iLLAs compared to unimpaired during walking36,39. However, an individual’s cardiovascular fitness level can improve with exercise training, which can improve the heart rate response to a given exercise40,41. The results of this study suggest that the 6MWT is long enough in duration for prosthesis users to achieve steady state VO2 and HR, but that the 2MWT is not.

Differences in iLLAs biomechanics between walking tests help elucidate possible mechanisms influencing the observed physiological responses. Prosthesis users walked slower during the 6MWT (1.18 ± 0.031 m/s) than in the 2MWT (1.22 ± 0.32 m/s). These speeds are similar to that seen in a recent study by Younesian et al. who observed a speed of 1.13 m/s during the 6MWT and decreases in stance ratio across time. Stance ratio, however, did not differ between walking tests in our iLLA participants. Although, iLLA stride lengths were significantly lower (3 cm) during the 6MWT. Reducing stride length to increase the backward margins of stability (BW MoS) is a gait strategy often used in persons with gait impairments42,43. Prosthesis users have reduced push-off power from their prosthesis and often employ stride and step adaptations for successful gait44. Thus, reducing gait speed and stride length during the 6MWT with concomitant plateaus in physiology suggest that iLLAs adjusted gait for successful performance of the 6MWT. Although unimpaired persons walked faster than iLLAs during both tests (0.20 and 0.32 m/s for 2MWT and 6MWT, respectively), their speed was 0.08 m/s faster during the 6MWT than in the 2MWT. Stride lengths were greater in unimpaired compared to iLLAs for both tests (18 and 23 cm for 2MWT and 6MWT, respectively), and although not significant, unimpaired stride lengths increased during the 6MWT compared to the 2MWT. Unimpaired cadence was 16.2 steps/min higher than iLLAs during the 6MWT but not 2MWT. Both groups optimized biomechanics for 6MWT completion. Prosthesis users reduced stride length and speed in a manner that may have spared energy expenditure whereas unimpaired persons appear to have done the opposite. As such, unimpaired persons performed better on the 2MWT and 6MWT covering greater distances than iLLAs.

Similar to prior scholarship, we found the 2MWT to be a strong predictor of 6MWT in iLLA7. This predictability was also observed for our unimpaired participant group. However, based off the results of this research it is clear that iLLAs employ markedly different gait strategies with altered physiology when completing the 6MWT. Thus, although test distances may be correlated, the 6MWT offers a direct challenge to a iLLAs users fitness and functional capacity. Thereby providing the prosthetist an outcome measure for evaluating their patient’s adaptability to a prolonged arduous walking task. Moreover, in unimpaired older adults, the 2MWT has recently shown to have no correlation with maximal aerobic capacity45. However, the utility of the 2MWT is its reduced burden on the iLLAs and pragmatic administration. Furthermore, there may be contraindications to the 6MWT for those with underlying health issues. Thankfully, the clinician has the option of either of these performance based assessments to choose from46.

This study is not without its limitations. Our heterogenic convenient sample recruited transtibial prosthesis users and excluded transfemoral prosthesis users. This may have influenced our findings as transfemoral prosthesis users require greater energy expenditure of walking compared to transtibial users47. Moreover, Gaunaurd et al., have observed significant differences across amputation levels in distance walked on timed walking tests (152.9 ± 43.0 m vs. 135.6 ± 43.0 m) (p < 0.05), for transtibial and transfemoral users respectively3. Future work should assess transfemoral prosthesis users performances during these tests. However, transtibial prosthesis users make up a majority of the iLLAs receiving prosthetic rehabilitation48. Moreover, exploring age related differences in our group of iLLAs was not performed. Others have discovered age related differences in spatiotemporal measures between 2 and 6MWT healthy adults49. As we did not repeat tests, we were unable to observe the possibility of a learning effect. This is an important consideration when administrating performance based outcome measures that should be pursued. Our sample was primarily K3 level users with one K2 participant. Exploring the physiological and biomechanical responses to timed walking tests in K2 level users is an important next step in this research.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated marked physiological and biomechanical differences in prosthesis users between the 2MWT and 6MWT. Despite the pragmatic utility, ease of administration, and distance predictability of the 2MWT, our findings do not support its use as a surrogate assessment of the 6MWT in iLLAs. Although a case can be made for selecting either of these tests. The 2MWT is appropriate for assessing gait performance in iLLAs over a short duration, whereas the 6MWT assesses steady state gait performance and functional capacity. Notwithstanding contraindications or other barriers, we encourage clinicians to utilize the 6MWT as it permits a comprehensive assessment of prosthesis users abilities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to university regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Resnik, L. & Borgia, M. Reliability of outcome measures for people with lower-limb amputations: Distinguishing true change from statistical error. Phys. Ther. 91, 555–565 (2011).

Cox, P. D. et al. Impact of course configuration on 6-minute walk test performance of people with lower extremity amputations. Physiother. Can. 69, 197–203 (2017).

Gaunaurd, I. et al. The utility of the 2-minute walk test as a measure of mobility in people with lower limb amputation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 101, 1183–1189 (2020).

Gailey, R. S. et al. Application of self-report and performance-based outcome measures to determine functional differences between four categories of prosthetic feet. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 49, 597–612 (2012).

Wurdeman, S. R., Schmid, K. K., Myers, S. A., Jacobsen, A. L. & Stergiou, N. Step activity and 6-minute walk test outcomes when wearing low-activity or high-activity prosthetic feet. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 96, 294–300 (2017).

Butland, R. J., Pang, J., Gross, E. R., Woodcock, A. A. & Geddes, D. M. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br. Med. J. Clin. Res. Ed. 284, 1607–8 (1982).

Reid, L., Thomson, P., Besemann, M. & Dudek, N. Going places: Does the two-minute walk test predict the six-minute walk test in lower extremity amputees?. J. Rehabil. Med. 47, 256–261 (2015).

Cooper, K. H. A means of assessing maximal oxygen intake. Correlation between field and treadmill testing. JAMA 203, 201–204 (1968).

American Thoracic Society. ATS committee on proficiency standards for clinical pulmonary function laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 166, 111–117 (2002).

van Velzen, J. M. et al. Physical capacity and walking ability after lower limb amputation: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil. 20, 999–1016 (2006).

Weyand, P. G. et al. Predicting metabolic rate across walking speed: One fit for all body sizes?. J. Appl. Physiol. 115, 1332–1342 (2013).

Weyand, P. G., Smith, B. R., Puyau, M. R. & Butte, N. F. The mass-specific energy cost of human walking is set by stature. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3972–3979 (2010).

Das Gupta, S., Bobbert, M. F. & Kistemaker, D. A. The metabolic cost of walking in healthy young and older adults—a systematic review and meta analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 9956 (2019).

Maxwell Donelan, J., Kram, R. & Arthur, D. K. Mechanical and metabolic determinants of the preferred step width in human walking. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268, 1985–1992 (2001).

Le, H. et al. Oxygen consumption and speed performance of a runner with amputation wearing an elevated vacuum running prosthesis. JPO J. Prosthetics Orthot. 33, 73–79 (2021).

Maltais, D., Bar-Or, O., Galea, V. & Pierrynowski, M. Use of orthoses lowers the O2 cost of walking in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200102000-00023 (2001).

Waters, R. L. & Mulroy, S. The energy expenditure of normal and pathologic gait. Gait Posture 9, 207–231 (1999).

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Advanced Exercise Physiology (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012).

Wasserman, K. et al. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2012).

McClave, S. A. et al. Achievement of steady state optimizes results when performing indirect calorimetry. JPEN. J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 27, 16–20 (2003).

Bock, A. V., Vancaulaert, C., Dill, D. B., Fölling, A. & Hurxthal, L. M. Studies in muscular activity. J. Physiol. 66, 162–174 (1928).

Ferretti, G., Fagoni, N., Taboni, A., Bruseghini, P. & Vinetti, G. The physiology of submaximal exercise: The steady state concept. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 246, 76–85 (2017).

Roston, W. L. et al. Oxygen uptake kinetics and lactate concentration during exercise in humans. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 135, 1080–1084 (1987).

Whipp, J. B. & Ward, A. S. Pulmonary gas exchange dynamics and the tolerance to muscular exercise: Effects of fitness and training. Ann. Physiol. Anthropol. 11, 207–214 (1992).

Cahalin, L. P., Mathier, M. A., Semigran, M. J., Dec, G. W. & DiSalvo, T. G. The six-minute walk test predicts peak oxygen uptake and survival in patients with advanced heart failure. Chest 110, 325–332 (1996).

Zhang, Q. et al. 6MWT performance and its correlations with VO2 and handgrip strength in home-dwelling mid-aged and older Chinese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 473 (2017).

Li, A. M. The six-minute walk test in healthy children: Reliability and validity. Eur. Respir. J. 25, 1057–1060 (2005).

Lin, S.-J. & Bose, N. H. Six-minute walk test in persons with transtibial amputation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89, 2354–2359 (2008).

Slater, L., Finucane, S. & Hargrove, L. J. Knee extensor power predicts six-minute walk test performance in people with transfemoral amputations. PM R 14, 445–451 (2022).

Washabaugh, E. P., Kalyanaraman, T., Adamczyk, P. G., Claflin, E. S. & Krishnan, C. Validity and repeatability of inertial measurement units for measuring gait parameters. Gait Posture 55, 87–93 (2017).

He, Y. et al. Accuracy validation of a wearable IMU-based gait analysis in healthy female. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 16, 2 (2024).

Kaufman, K. R. et al. Fall Prevention training for service members with an amputation or limb salvage following lower extremity trauma. Mil. Med. 189, 980–987 (2024).

Prado, M., Oyama, S. & Giambini, H. Marker-based versus IMU-based kinematics for estimates of lumbar spine loads using a full-body musculoskeletal model. J. Appl. Biomech. https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.2023-0202 (2024).

Borg, G. A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14, 377–381 (1982).

Bell, J. C., Wolf, E. J., Schnall, B. L., Tis, J. E. & Potter, B. K. Transfemoral amputations: Is there an effect of residual limb length and orientation on energy expenditure?. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 472, 3055–3061 (2014).

Russell Esposito, E., Rodriguez, K. M., Ràbago, C. A. & Wilken, J. M. Does unilateral transtibial amputation lead to greater metabolic demand during walking?. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 51, 1287–1296 (2014).

Schnall, B. L., Wolf, E. J., Bell, J. C., Gambel, J. & Bensel, C. K. Metabolic analysis of male servicemembers with transtibial amputations carrying military loads. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 49, 535–544 (2012).

Ludwig, M., Hoffmann, K., Endler, S., Asteroth, A. & Wiemeyer, J. Measurement, prediction, and control of individual heart rate responses to exercise-basics and options for wearable devices. Front. Physiol. 9, 778 (2018).

Hagberg, K., Tranberg, R., Zügner, R. & Danielsson, A. Reproducibility of the physiological cost index among individuals with a lower-limb amputation and healthy adults. Physiother. Res. Int. 16, 92–100 (2011).

Hickson, R. C., Hagberg, J. M., Ehsani, A. A. & Holloszy, J. O. Time course of the adaptive responses of aerobic power and heart rate to training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 13, 17–20 (1981).

Carter, J. B., Banister, E. W. & Blaber, A. P. Effect of endurance exercise on autonomic control of heart rate. Sports Med. 33, 33–46 (2003).

Hak, L., Houdijk, H., Beek, P. J. & van Dieën, J. H. Steps to take to enhance gait stability: The effect of stride frequency, stride length, and walking speed on local dynamic stability and margins of stability. PLoS ONE 8, e82842 (2013).

Curtze, C., Hof, A. L., Postema, K. & Otten, B. Over rough and smooth: Amputee gait on an irregular surface. Gait Posture 33, 292–296 (2011).

Houdijk, H., Wezenberg, D., Hak, L. & Cutti, A. G. Energy storing and return prosthetic feet improve step length symmetry while preserving margins of stability in persons with transtibial amputation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 15, 76 (2018).

Gil-Calvo, M. et al. The 2-minutes walking test is not correlated with aerobic fitness indices but with the 5-times sit-to-stand test performance in apparently healthy older adults. Geriatrics 9, 43 (2024).

Heinemann, A. W., Connelly, L., Ehrlich-Jones, L. & Fatone, S. Outcome instruments for prosthetics. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 25, 179–198 (2014).

Czerniecki, J. M. & Morgenroth, D. C. Metabolic energy expenditure of ambulation in lower extremity amputees: What have we learned and what are the next steps?. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 143–151 (2017).

Raichle, K. A. Prosthesis use in persons with lower- and upper-limb amputation. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 45, 961–972 (2008).

Swanson, C. W., Haigh, Z. J. & Fling, B. W. Two-minute walk tests demonstrate similar age-related gait differences as a six-minute walk test. Gait Posture 69, 36–39 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDS and GG wrote the main manuscript text, and GG prepared all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, J.D., Guerra, G. Oxygen uptake kinetics differentiates two from six minute walk tests in lower extremity prosthesis users. Sci Rep 15, 32914 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18094-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18094-8