Abstract

Wheels are critical components of railway vehicles, and the dynamic measurement of wheel parameters is of paramount importance for the safe operation of trains.To enhance the matching accuracy in the existing dynamic measurement processes for train wheel parameters, this paper proposes an improved point cloud registration algorithm based on key point fusion of the Super Four-Points Congruent Sets (Super-4PCS) and Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm. Firstly, point cloud filtering and normal estimation are performed on the wheel point cloud data to obtain source and target point clouds with normal information. Subsequently, the Intrinsic Shape Signatures (ISS) algorithm is employed to extract key points, and the Fast Point Feature Histograms (FPFH) point cloud feature descriptor is utilized to characterize the extracted key points. Then, a two-level registration strategy is used to improve registration accuracy, in which the Super-4PCS algorithm is applied for primary coarse registration and the ICP algorithm is used for the secondary fine registration, respectively. Finally, the experiment is conducted to validate the proposed algorithm and the performance of the algorithm is further comparative analyzed through the listed registration evaluation metrics. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm significantly improves registration accuracy and robustness for wheel point cloud data, with the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) reduced from 0.0631 to 0.0002, and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) reduced from 0.0671 to 0.00026, compared to traditional algorithms. However, the algorithm’s performance is sensitive to point cloud density and noise levels, and its effectiveness may vary under different environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

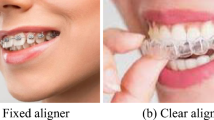

As a critical component of rail vehicles, wheel condition directly impacts operational safety and ride comfort. Current detection methods are classified into static and dynamic mode1,2,3. Static detection uses portable optical equipment for offline measurements but suffers from low efficiency4,5,6,7,8. In contrast, non-contact dynamic measurement enables high-precision, high-speed, and non-destructive acquisition of wheelset geometric parameters and tread damage without disrupting train operations, offering broad application potential. Thus, it has become the primary approach for wheel inspection.

The mainstream dynamic wheel inspection technologies, such as structured light scanning and binocular vision, rely on point cloud data processing. Significant progress has been made in wheel point cloud data processing in recent years, with researchers focusing on improving the precision and efficiency of wheel profile measurements. For example, Gao et al.9 developed a laser profilometry-based method using an angle-distance discriminant function and segmented filtering to obtain accurate wheel profile curves. Zhuang et al.10 applied structured light scanning and greedy projection triangulation for 3D surface reconstruction, enabling wear and damage assessment via comparison with standard models. Hu et al.11 improved Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) for tread feature matching and used Iterative Closest Point(ICP) to register and fuse point clouds for 3D worn tread modeling. Yi et al.12 proposed the Region of Interest-Robust and Scalable Iterative Closest Point (ROI-RSICP) method with weighted registration of worn and non-worn regions to recover affine-distorted profiles. Xing et al.13 combined least-squares fitting and feature extraction to compute flange height, width, and diameter. Zhou et al.14 achieved dynamic 3D tread reconstruction through outlier removal and composite denoising. Zhang et al.15 enhanced ICP with Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) and distance threshold attenuation, achieving full registration using calibration blocks. Ran et al.16 introduced a skeleton-based sub-pixel laser stripe center extraction algorithm for improved robustness under complex lighting. Fang et al.17 developed a handheld imaging system optimizing center extraction for rapid 3D modeling and multi-parameter measurement. Feng et al.18 utilized dual 1D laser sensors for accurate radius measurement with reduced snaking-induced errors at low speeds (< 15 km/h). Chen et al.19 built a line-structured light system for tread damage detection and parameter quantification.

Despite these advances, existing methods still lack sufficient accuracy in point cloud registration.In recent years, several new methods have emerged to address these challenges. For instance, Qin et al.20 introduced GeoTransformer, a geometry-aware Transformer model that improves point cloud registration speed by 100 times and eliminates the need for RANSAC. Slimani et al.21 proposed a deep learning-based method for 3D point cloud registration, demonstrating promising results on ModelNet40 and real-world Bunny datasets, outperforming state-of-the-art methods in most scenarios. Liu et al.22 developed RegFormer, a projection-aware Transformer network for large-scale point cloud registration. Chen et al.23 presented SIRA-PCR, using adaptive resampling to enhance deep learning model generalization to real-world scenarios.Zhang24 provides a comprehensive survey of point cloud registration, classifying methods as supervised or unsupervised and summarizing datasets, evaluation metrics, and open challenges.

Nevertheless, point cloud registration remains challenging in the presence of intricate geometric structures and large-scale datasets.Therefore, this paper proposes a train wheel point cloud registration algorithm based on key point fusion of the Super Four-Points Congruent Sets (Super-4PCS) and the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm. The methodology primarily consists of three components: (1) Perform point cloud filtering and normal estimation on wheel point cloud data to obtain source and target point clouds with normal information. Subsequently, extract keypoints using the Intrinsic Shape Signatures (ISS) algorithm and characterize the extracted keypoints through the Fast Point Feature Histograms (FPFH) point cloud feature descriptor; (2) Employ an improved Super-4PCS registration algorithm for coarse registration of wheel point clouds, followed by fine registration using the ICP algorithm upon completion of coarse alignment, ultimately achieving registration between the source and target point clouds; (3) Enumerate the registration evaluation metrics utilized in this study and conduct experimental validation and comparative analysis of various algorithms. Experimental results demonstrate that compared to traditional algorithms, the proposed algorithm exhibits significant improvements in registration accuracy and robustness for wheel point cloud data.

Preprocessing and key point extraction of wheel point cloud data

The bogie structure is relatively complex, and the acquired wheel point cloud data contain some point clouds of other components that are irrelevant to the main wheel point cloud. Meanwhile, due to factors such as field environment and equipment accuracy, the point cloud data obtained through sensors inevitably include redundant information, outliers, and noise points. Therefore, the wheel point cloud data captured by cameras often cannot be used directly. To improve point cloud registration accuracy, this study employs statistical filtering algorithms and conditional filtering algorithms to process the wheel point cloud data. Additionally, the point cloud data captured by cameras often only contain xyz coordinate information. To better describe the point clouds and prepare for subsequent computations, the minimum spanning tree-based normal orientation method is adopted to reorient the wheel point cloud normals.

Preprocessing of wheel point cloud data

The bogie structure is relatively complex, and the acquired wheel point cloud data often contain point clouds of other components that are irrelevant to the main wheel body. Therefore, the raw wheel point cloud data captured by the camera cannot be directly utilized. To improve point cloud registration accuracy, this study employs statistical filtering algorithms25 and conditional filtering algorithms to process the wheel point cloud data. In this study, statistical filtering parameters k = 30 and α = 5 were selected based on extensive comparative experiments. This combination was determined by optimizing noise removal while preserving significant data points, achieving the best compromise between denoising and geometric fidelity, as shown in Fig. 1 (original 263,475 points with 460 noise points identified).

Due to the low overlap rate of only 14.3% between pairs of the six frames of point clouds, misregistration may occur during subsequent point cloud registration. To improve the overlap rate, this study applies conditional filtering to segment the initial source and target point clouds, and computes the minimum bounding box of the point clouds, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The calculated minimum bounding box has dimensions of (448.68, 150.51, 72.25), with its center coordinates at (− 200.13, 361.81, 56.28). The point cloud ranges are: x-axis from (− 424.6, 21.7), y-axis from (288.05, 412.9), and z-axis from (0, 135.12). Based on these ranges, constraints are set along the x-axis and y-axis for filtering. The filtering results are shown in Fig. 2b, where the green portion represents the filtered overlapping region point cloud.

Surface normals are fundamental geometric attributes and are widely used in keypoint extraction and feature-descriptor construction. The wheel point clouds acquired by the camera contain only coordinates, thus requiring normal estimation. We evaluated two strategies: principal component analysis (PCA) for normal estimation with default orientation, and a minimum-spanning-tree (MST)–based orientation method. As shown in Fig. 3, PCA yields orientation errors in the highlighted region, whereas the MST approach produces consistent, physically plausible normals. Accordingly, we adopt the MST-based orientation for all subsequent experiment.

Key point extraction from wheel point cloud data

Keypoints are stable and distinctive point sets extracted through detection methods that preserve the main characteristics of point clouds. On one hand, keypoint extraction reduces computational burden; on the other hand, it decreases the number of feature matches and the probability of incorrect matching. Common keypoint extraction algorithms include Normal Aligned Radial Feature (NARF) algorithm, ISS algorithm, SIFT algorithm26, and Harris 3D corner detection.

SIFT algorithm keypoint extraction experiment

This study first employs the SIFT algorithm to extract keypoints from wheel point cloud data, with SIFT algorithm parameter values shown in Table 1. The SIFT keypoint extraction results for target and source point clouds are illustrated in Fig. 4. It can be observed that the keypoints extracted by the SIFT algorithm from wheel point clouds do not exhibit readily identifiable patterns upon direct visual inspection. Furthermore, the number of keypoints extracted from target and source point clouds varies slightly at different viewing angles, potentially leading to mismatched points.

ISS keypoint extraction experiment

The key parameters of the ISS algorithm include the search radius R, the threshold parameters \({\gamma _{21}}\) and \({\gamma _{32}}\) used in the key point selection stage, and the radius r and minimum number of neighboring points n required within that radius for the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) stage. As shown in Fig. 5, without NMS, the circular symmetry of the wheel point cloud leads to the detection of a large number of geometrically similar key points around the circumference. This redundancy significantly degrades the distinctiveness of features and severely interferes with subsequent point cloud registration algorithms, potentially causing incorrect correspondences and convergence failure. Therefore, the application of NMS is essential for processing train wheel point clouds.

Sensitivity analysis of the ISS parameters revealed their impact on keypoint extraction. The \({\gamma _{21}}\) parameter influences keypoint selection based on curvature, with higher values making the algorithm more sensitive to sharp features such as edges and ridges, typical of wheel geometries. The \({\gamma _{32}}\) parameter refines this selection by considering the proximity of neighboring points, resulting in fewer but more geometrically significant keypoints with larger values. The search radius R is critical for capturing wheel curvature: a radius too small may miss key features, while a larger radius could introduce noise. The NMS radius r suppresses irrelevant points from flat areas, ensuring that keypoints are extracted from regions with noticeable curvature, like the tread and flange, which are crucial for accurate registration.

The parameters \({\gamma _{21}}\) and \({\gamma _{32}}\) typically range between 0 and 1 and are empirically chosen based on the geometric characteristics of the wheel point cloud. After fixing the NMS parameters, iterative computations were performed to evaluate keypoint extraction results under varying threshold values, as shown in Fig. 6. Experimental results show that the number of detected keypoints is primarily influenced by \({\gamma _{21}}\). A significant change in the number and distribution of keypoints occurs only when \({\gamma _{32}}\) is set to a very small value (e.g., 0.001), indicating that the ISS algorithm is robust to moderate variations in parameter settings. However, excessive relaxation of the threshold can lead to the inclusion of geometrically insignificant points, particularly in low-curvature or noisy regions.

In this study, the search radius is set to 5 mm. The NMS radius r and the minimum number of neighboring points n within that radius are empirically determined as 5 mm and 6, respectively. The final ISS algorithm parameters and the corresponding key point extraction results are summarized in Table 2.

Key points are extracted from both the target and source point clouds using the ISS algorithm. The identical number of detected key points in both point clouds indicates that the ISS algorithm provides a clear and consistent description of local geometric features, demonstrating strong stability and repeatability with respect to rotation and translation transformations.Further analysis of a large number of experimental results reveals that, in this study, the measured wheel is relatively new and the acquired point cloud segment is short. As a result, the tread region exhibits nearly planar geometry, causing the second smallest eigenvalue ratio (e.g., \({{\lambda _{i}^{2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\lambda _{i}^{2}} {\lambda _{i}^{1}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\lambda _{i}^{1}}}\)) to approach 1 in this area. Consequently, very few key points are detected on the tread surface—consistent with the ISS criterion that suppresses feature responses in flat or low-curvature regions.

Selection of key point extraction algorithm for wheel point cloud data

Through experimental comparison of the ISS and SIFT algorithms, we found that the ISS algorithm offers superior robustness and generates more distinctive keypoints, which is crucial for train wheel point cloud data that requires stability and invariance under various transformations. However, the ISS algorithm has a tradeoff: slower computational speed and higher sensitivity to noise. As shown in Table 2, ISS achieves zero mismatched points, while SIFT generates 3% mismatched points, which can lead to misalignment during registration.

Although the SIFT algorithm is faster and better suited for real-time processing, it results in more mismatches, especially under varying viewing angles or noisy conditions, increasing the demands on subsequent registration steps. Figure 5 shows that SIFT produces more mismatched points across different test cases, complicating the registration process and affecting accuracy.

Given the need for both speed and accuracy, this study selects the ISS algorithm for keypoint extraction. Despite its higher computational cost, ISS provides more reliable and robust keypoints, making it more suitable for the precise wheel point cloud registration required in this study. Moreover, the ISS-based registration achieved significantly lower errors compared to SIFT-based registration.

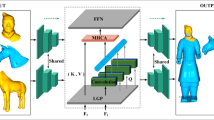

Wheel point cloud feature descriptor

A point cloud feature descriptor is an N-dimensional vector that describes the characteristics of point cloud features. The keypoints detected in point clouds are not directly suitable for feature matching. By describing the detected keypoints using point cloud feature descriptors, the robustness of features can be enhanced, improving the comparability and matching rate between feature points. Histogram-based descriptors exhibit stronger robustness in feature representation27, while feature-based descriptors demonstrate superior descriptive capability. Therefore, this study selects the Point Feature Histograms (PFH) descriptor28 to represent the wheel point cloud features, as illustrated in Fig. 8.

Wheel point cloud registration algorithm

Coarse registration of wheel point clouds based on key points using the Super-4PCS algorithm

The most commonly used method for coarse registration of point cloud data is the Super 4PCS algorithm29. The Super-4PCS algorithm is a robust method for point cloud registration. It works by selecting four point pairs from each point cloud and computing affine invariants between them. These pairs are used to compute an initial transformation that aligns the two point clouds. The Super-4PCS algorithm excels in situations with low overlap between the point clouds and is resistant to noise, making it particularly useful for coarse registratio.The Super 4PCS algorithm achieves fast registration speed; however, when point clouds exhibit symmetry as shown in Fig. 9, incorrect point pair identification can easily occur during the matching process. This is particularly problematic for rotational symmetric objects such as wheel point clouds, resulting in unstable registration outcomes.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a keypoint-based Super 4PCS algorithm built upon the original Super 4PCS framework. The main steps are as follows:

Step 1: Extract ISS keypoints from the source point cloud P and target point cloud Q to form the corresponding keypoint cloud P′ and Q′. This preserves the main geometric features while avoiding regions with strong symmetry, thereby reducing the influence of point cloud noise on the registration results.

Step 2: Select four coplanar points in as a point base (quadruplet), ensuring that all four points lie within the overlapping region. As shown in Fig. 10, this forms a coplanar four-point basis \(B=\{ {p_a},{p_b},{p_c},{p_d}\}\). According to Eq. (1), two affine invariants \({r_1}\) and \({{\text{r}}_2}\), the lengths of two line segments \({d_1}{\text{ and }}{d_2}\), and the included angle θ can be computed.

Step 3: Determine point pair sets S1 and S2 in the target point cloud Q′. Using a gridding-based approach, for any arbitrary point \({q_i}\) in Q, find all points that are at a distance of \({{\text{d}}_1} \pm \varepsilon\) from \({q_i}\) and form point pairs recorded in S1, and all points that are at a distance of \({{\text{d}}_2} \pm \varepsilon\) from \({q_i}\) and form point pairs recorded in S2.

Step 4: As illustrated in Fig. 11, compute the potential intersection points e1 and e2 on the line segments of point pairs in S1 and S2, respectively, according to Eq. (2).

Step 5: As shown in Fig. 12, identify point pairs whose intersection points e1 and e2 are approximately coincident and whose angle between the connecting line segments is approximately equal to θ, forming a four-point set \({U_i}\). For simplicity, only the two intersection points of each point pair are labeled in Fig. 12.

Step 6: In the point cloud Q′, find all four-point sets \(U=\{ {U_1},{U_2},...,{U_n}\}\) that correspond to the coplanar four-point base B. For each four-point set \({U_i}\), a rigid transformation matrix Ti can be computed based on B and the corresponding four-point set.

Step7: Given the set of transformation matrices \(T=\{ {T_1},{T_2},...,{T_{\text{n}}}\}\) obtained from the Super-4PCS registration based on keypoint correspondences, apply each transformation matrix \({T_{\text{i}}}\) to the source point cloud P to obtain the transformed point cloud P″. For each point \({\text{p}}{{{\prime }}_{\text{i}}}{{\prime }}\) in \(P''\), compute its distance \({d_i}\) to the nearest point \({q_i}\) in the target point cloud Q, and form the corresponding point pair. If the distance \({d_i}\) is less than a predefined threshold τ, the pair is regarded as an inlier and added to the inlier set \({S_I}\); otherwise, it is regarded as an outlier and added to the outlier set \({S_O}\). Finally, calculate the inlier ratio (IR) \({E_{IR}}\) for each transformation, and select the transformation matrix with the highest inlier ratio as the final registration transformation.

Fine registration of wheel point cloud data based on the ICP algorithm

Fine registration is performed based on the coarse registration results to achieve more precise and refined alignment. Common fine registration algorithms include the ICP algorithm30the Normal Distributions Transform (NDT) algorithm, and their respective improved variants. The ICP algorithm is a well-known technique used for fine registration of point clouds. It works by iteratively minimizing the distance between corresponding points in two point clouds. The algorithm refines the initial alignment provided by a coarse registration method (such as Super-4PCS) by iteratively adjusting the transformation until the point clouds are optimally aligned.This study employs the ICP algorithm to implement fine registration of wheel point cloud data.The implementation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Input the source point cloud P and the target point cloud Q. Apply an initial transformation to each point \({p_i}\)in the source point cloud P using the initial transformation matrix \({T_0}\)(taken from the coarse registration), resulting in the transformed point cloud \(p{'_i}\) .

Step 2: In the target point cloud Q, find the nearest point \({q_i}\) to point \(p{'_i}\), forming point pairs\({M_i}=(p{'_i},{\text{ }}{q_i})\).The collection of all such point pairs constitutes the correspondence set \(M=\{ {M_1},{M_2},...,{M_{\text{n}}}\}\).

Step 3: Compute the optimal transformation matrix \(\Delta T\)by applying the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) algorithm to the point pairs in M .

Determine convergence based on criteria such as the error p between consecutive iterations and the number of iterations. If convergence is achieved, output the final result: \(T=\Delta T * {T_0}\); otherwise, repeat steps 1–3.

Experimental results and analysis

Wheel point cloud dataset

The wheel point cloud data used in this study were acquired under dynamic measurement conditions, with data collection performed using the DeepVision Intelligence SR5320 depth camera, as shown in Fig. 13. The experimental setup involved capturing point clouds from the rotating wheels under dynamic measurement conditions. Data were collected in a controlled environment designed to minimize external interference and ensure high-quality point cloud acquisition. However, potential sources of error during data collection, such as sensor inaccuracies, environmental noise, and the alignment of the camera relative to the wheel, were considered. These factors may contribute to slight variations in the acquired data.

Using the above setup, multiple surface contour lines of the wheel were captured and integrated to form the raw, global wheel point cloud, as shown in Fig. 14. The proposed algorithm targets adjacent point-cloud frames acquired by a stereo camera. To emulate practical stereo acquisition and validate the subsequent algorithms, we partitioned the raw data into six segments, each spanning a central angle of 70° with 10% overlap between neighboring segments, as shown in Fig. 15. These six segments correspond to the six frames recorded by the measurement system, as shown in Fig. 16.

After segmenting the original data, the first and second frames of point cloud data were selected and Gaussian noise and random noise were added to obtain the corresponding noisy point clouds \({P_1}\) and \({P_2}\). The point cloud data after noise addition are shown in Fig. 17.

The second frame of point cloud \({P_2}\) data was subjected to a 3D transformation to obtain the point cloud \({P_2}'\), simulating real-world conditions. The transformation matrix is given in Eq. (4), where T represents the transformation matrix, R denotes the rotation matrix, and t represents the translation vector. The spatial position of the transformed point cloud data is illustrated in Fig. 18.

For computational convenience, the overlapping region of the first frame point cloud is defined as the source point cloud P, and the overlapping region of the transformed second frame point cloud is defined as the target point cloud Q .

Registration evaluation metrics

In research work, the performance of proposed methods must be evaluated using appropriate metrics. This section introduces several commonly used evaluation metrics for point cloud registration problems.

The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) are commonly used to measure the error between the transformed source point cloud (after applying the estimated motion parameters) and the ground truth point correspondences.

In Eqs. (5) and (6), p represents points in the source point cloud that correspond one-to-one with points q in the target point cloud, and \({M_{i,j}}\)denotes the set of all point pairs.

Rotation Error \({E_R}\) and Translation Error \({E_t}\) are generally used to measure the deviation between the estimated transformation matrix and the ground truth transformation matrix. These metrics are primarily applicable in scenarios where the true transformation matrix is known.

In Eq. (7), \({R_t}\) represents the ground truth rotation matrix, and \({R_e}\) represents the estimated rotation matrix. Since rotation matrices are orthogonal matrices, \({R_e}^{{ - 1}}\) in the equation can also be replaced by \({R_e}^{T}\) during computation.

In Eq. (8), \({t_t}\)represents the ground truth translation vector, and \({t_e}\) represents the estimated translation vector.

The inlier ratio (\({E_{IR}}\)) is commonly used to measure the proportion of valid correspondences between a pair of point clouds.

In Eq. (9), N represents the total number of point pairs, 1 [ ] denotes the Iverson bracket, which takes the value 1 when the expression inside the bracket is true and 0 otherwise, and τ is the distance threshold.

Experimental results and analysis

To verify the feasibility of the improved algorithm proposed in this study, different schemes were designed to perform registration on wheel point clouds, As shown in Table 3.

The coarse registration results and fine registration results are shown in Figs. 19 and 20, respectively. The registration evaluation metrics were calculated after registration, and the computational results are presented in Table 4. The heatmap of evaluation metrics for registration results under different schemes is illustrated in Fig. 21.

We have noted that the zero rotation error reported for Scheme 2 in Table 4 is an idealized result, which reflects the high accuracy achieved by the coarse registration step. This result indicates that the coarse alignment, aided by the Super-4PCS algorithm with ISS keypoints, provides a highly precise initial transformation. However, we acknowledge that in practical applications, slight rotation errors may arise due to data specificity, including variations in the point cloud quality, noise, and the inherent characteristics of the scanned objects. These factors could lead to small discrepancies that are not captured in the idealized result presented in the table. This has been clarified in the manuscript to ensure the reliability and reasonableness of the result.

In Fig. 20, the registration results of Scheme 1 and Scheme 2 are compared. While both schemes exhibit similar computational times, Scheme 2, which employs the proposed algorithm, achieves significantly higher accuracy. This improvement can be attributed to several factors:

-

(1)

Better noise handling: Scheme 2, using the improved Super-4PCS algorithm for coarse registration, is more effective at handling noisy data. The ISS keypoints, which are more stable and distinctive in Scheme 2, reduce mismatches and misalignments that often arise in noisy conditions. This results in a more accurate initial registration.

-

(2)

Improved coarse registration: The use of the ISS algorithm with Super-4PCS in Scheme 2 provides a more accurate coarse alignment. This reduces errors in the initial stage of registration, which in turn enhances the performance of the fine registration phase. A better starting alignment allows for more effective refinement during the fine registration, ensuring higher overall accuracy.

-

(3)

Complementary fine registration with ICP: After the initial coarse registration, the ICP algorithm in Scheme 2 refines the alignment, achieving further improvements in registration accuracy. This two-stage process—coarse registration followed by fine registration—results in a much more accurate final alignment compared to Scheme 1, which does not integrate the ISS keypoints and uses traditional methods for both coarse and fine registration.

Thus, despite the similar total computation time in both schemes, the higher accuracy in Scheme 2 can be attributed to its better handling of noise, more accurate coarse registration, and the complementary refinement achieved by ICP.

Through the aforementioned experiments, it was found that compared to other algorithms, Scheme 4, which employs the improved algorithm proposed in this study for coarse registration, achieves enhanced performance across all evaluation metrics, despite a slight increase in computational time relative to traditional algorithms. In Scheme 2, after applying the proposed algorithm for coarse registration, the registration time is comparable to that of traditional algorithms, while both registration accuracy and robustness outperform other schemes. Therefore, the final registration scheme adopted for the system in this study involves using the improved the Super-4PCS algorithm based on ISS keypoints for coarse registration, followed by the ICP algorithm for fine registration, thereby achieving the final wheel point cloud registration.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a train wheel point cloud registration algorithm based on key points by fusing the Super-4PCS and ICP. The algorithm employs the ISS algorithm to extract key points, achieving effective extraction of major wheel features while reducing the impact of point cloud noise on registration accuracy. Subsequently, the extracted ISS key points are used as input to the Super-4PCS algorithm, which accelerates the search process and improves coarse registration accuracy. Following coarse registration, the ICP algorithm is applied for fine registration, ultimately achieving accurate alignment between the source and target point clouds. Finally, the registration evaluation metrics used in this study are enumerated, and comprehensive experimental validation and comparative analysis are conducted on various algorithms. Compared to traditional algorithms, the wheel point cloud registration errors obtained using the proposed method in this paper are significantly reduced. Specifically, The RMSE decreased from 0.0631 to 0.0002, The MAE reduced from 0.0671 to 0.00026, The Rotational Error decreased from 0.0077 to 0, and The Translational Error reduced from 0.0146 to 0.0029.Experimental results demonstrate that compared to traditional algorithms, the proposed algorithm achieves significant improvements in registration accuracy and robustness for wheel point cloud data, providing important implications for non-contact dynamic measurement of train wheels.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ward, C. P. et al. Condition monitoring opportunities using vehicle-based sensors. In Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part F: Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit (2011).

Yang, K. Research on Detection Technology of Wheel Tread Scuffing and out-of-roundness (Southwest Jiaotong University, 2015).

Zhang, F., Wang, H., Zeng, Q., Wu, P. & Pan, M. Novel method for measuring high-frequency wheel-rail force considering wheelset vibrations. Sci. Rep.

Zhang, H. & Ye, H. Researching of inspecting method for wheelsets abrasion based on image processing. Machinery. (2004).

Feng, Q., Zhang, G., Zhao, H., Chen, S. & Wang, Z. New method for automatically measuring geometric parameters of wheel sets by laser. Int. Soc. Opt. Photonics. 5253, 110 (2003).

Torabi, M., Mousavi, S. G. M. & Younesian, D. A. High accuracy imaging and measurement system for wheel diameter inspection of railroad vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Online three-dimensional measurement technology for cast steel wheels based on rotational scanning with multiple line laser sensors. Chin. J. Lasers. 46, 7 (2019).

Li, M., L, L. & Y, Y., Y, B. & RC-IRLSCF method and its application in line laser-based tread measurement of in-service wheels. Chin. J. Lasers. 47, 8 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. Research on the line point cloud processing method for railway wheel profile with a laser profile sensor. Measurement 211, 112640 (2023).

Zhuang, R., Chen, P., Fu, Y. & Huang, Y. Research on Point Cloud Processing in Three-Dimensional Structured Light Inspection of Train Wheelsets (China Measurement & Testing, 2021).

Hu, C. et al. Surface defect and profile parameter detection method for train wheelsets based on binocular vision. China Meas. Test. 50, 101–108 (2024).

Yi, Q., Zhong, H., Liu, L., Liu, W. & Yi, B. Dynamic detection of vehicle contour based on ROI-RSICP algorithm. Chin. J. Lasers (2020).

Xing, Z., Chen, Y., Wang, X., Qin, Y. & Chen, S. Online detection system for wheel-set size of rail vehicle based on 2D laser displacement sensors. Optik: Z. Fur Licht- Und Elektronenoptik: = J. Light-and Electronoptic. 127 (2016).

Zhou, C., Gao, C., Li, L. & Wang, D. Design of teaching experiment for dynamic measurement of wheelset tread profile based on 3D point cloud. Exp. Technol. Manag. 41 (2024).

Zhang, X., Peng, C. & Qiu, C. A measurement method for train wheel size based on calibration block assisted whole wheel registration. Fifteenth Int. Conf. Inform. Opt. Photonics (CIOP 2024). 13418, 207–216 (2024).

Ran, Y., He, Q., Feng, Q. & Cui, J. High-accuracy on-site measurement of wheel tread geometric parameters by line-structured light vision sensor. IEEE Access. 9, 52590–52600 (2021).

Fang, Y. et al. Rapid measurement method for key dimensions of train wheelset based on improved image processing algorithm. Meas. Sci. Technol. 35, 086012 (2024).

Feng, Q., Zhao, Y. & Cui, J. A new method for dynamic quantitative measurement of wheel tread scuffing. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 38, 120–122 (2002).

Chen, X., Sun, J., Liu, Z. & Zhang, G. Dynamic tread wear measurement method for train wheels against vibrations. Appl. Opt. 54, 5270–5280 (2015).

Qin, Z. et al. Geotransformer: Fast and robust point cloud registration with geometric transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 9806–9821 (2023).

Slimani, K., Tamadazte, B. & Achard, C. Rocnet: 3D robust registration of points clouds using deep learning. Mach. Vis. Appl. 35, 100 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 8451–8460.

Chen, S. et al. Sira-pcr: Sim-to-real adaptation for 3d point cloud registration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 14394–14405 (2023).

Zhang, Y. X., Gui, J., Cong, X., Gong, X. & Tao, W. A comprehensive survey and taxonomy on point cloud registration based on deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.13830 (2024).

He, D., Shao, X., Wang, D. & Hu, S. Denoising method for plant 3D point cloud data acquired by kinect. Trans. Trans Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 47, 331–336 (2016).

Zhong, Y. Intrinsic shape signatures: A shape descriptor for 3D object recognition. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (2010).

Lowe, D. G. Distinctive image features from Scale-Invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 60, 91–110 (2004).

Rusu, R. B., Blodow, N. & Beetz, M. Fast Point Feature Histograms (FPFH) for 3D registration. In IEEE International Conference on Robotics & Automation (2009).

Mellado, N., Aiger, D. & Mitra, N. J. Super4PCS: fast global pointcloud registration via smart indexing. Comput. Graph. Forum. 33, 205–215 (2015).

Besl, P. J. & Mckay, H. D. A method for registration of 3-D shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 14, 239–256 (1992).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 52372327), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation [Grant number: 20242BAB26065].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X. and X.G.; methodology, Q.X. and Y.Z.; software, Z.Z.; validation, Q.X. and K.S.; formal analysis, X.G. and Z.X.; investigation, X.G. and Z.Z.; resources, X.G. and Y.Z.; data curation, X.G. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, Q.X. and Z.X.; visualization, Q.X.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Q.X. and Z.X.; funding acquisition, Q.X. and X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Q., Gao, X., Zhang, Z. et al. Research on train wheel point cloud registration algorithm based on key points by fusing Super-4PCS and ICP. Sci Rep 15, 32156 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18099-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18099-3