Abstract

Animal manures (AMs) are widely utilized as organic fertilizers but often contain significant levels of emerging pollutants, posing environmental and health risks. This experimental study investigated the impact of 650-million-year natural mineral biochar (NMB) and animal manure (CWM:PUM) on the fate of pollutants in the process of intermittent aeration and mixing composting. 12 treatments were monitored over 60 days to evaluate the fate of pollutants, nutrients, and environmental risks. The cumulative temperatures (°C) recorded for treatments T1–T12 were 897, 858, 836, 981, 926, 898, 1007, 999, 959, 1056, 1025, and 972, respectively. At the start of the process, the Zn concentrations in treatments T1, T4, T7, and T10 were 197.15, 336.32, 287.53, and 244.16 mg/kg, respectively. By day 60, they had decreased to 185.78, 296.14, 197.52, and 129.58 mg/kg, respectively. Cu concentration in mature compost was 228.31, 109.36, 76.11, and 131.5 mg/kg. The removal efficiency rankings varied across treatments: in control, Zn > Cu > Cr, in 5% NMB: Cr > Cu > Zn, and in 10% and 15% NMB: Zn > Cr > Cu. Zn, Cu, and Cr showed significant reductions due to adsorption, surface complexation, and pH-mediated mechanisms, with final concentrations below the USEPA standards. This study highlights the efficacy of NMB in improving compost quality, reducing pollutant bioavailability, and mitigating environmental risks, underscoring its potential as a sustainable solution for managing animal manure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, animal food production in developing countries has increased rapidly, leading to large volumes of animal manures (AMs) being dumped near urban areas1. In Iran, the annual production of manure is estimated at 251,313 tons for livestock and 744.77 million tons for poultry (including chickens and turkeys).

For the past, humans who engaged in agricultural activities have used AMs in agricultural fields as phosphate and nitrogen-rich fertilizers. However, the presence of heavy metals (HMs) has limited this practice. This is a potential concern to limit the use of animal fertilizers in the future if precautions are not taken to reduce the HMs2. If not properly managed, these pollutants can accumulate in soil, increase their bioavailability, be absorbed by plants, contaminate ground and surface water, and pose risks to public health3.

The presence of HMs in AMs is often linked to contamination in crops and animal feed4. Therefore, it is essential to assess the composition of metals to reduce the risk of off-site contamination and ensure a safe agricultural ecosystem5,6. The results of the simulation model estimation for heavy metals in soil showed that the environmental risk of zinc, copper, and cadmium will exceed threshold values in the next few decades7. In the UK, the concentration of zinc and copper in soil has increased by approximately 60% after long-term use (over 160 years) of manure in agriculture8. Long-term consumption of products contaminated with heavy metals may lead to serious health problems, including skin problems, cancer, high blood pressure, bone weakening, endocrine disruption, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, intrauterine growth retardation, neurological disorders, etc.9,10.

In animal husbandry, elements such as zinc, chromium, and copper are widely used in poultry and livestock diets to prevent diseases, improve weight gain, and increase egg production. Feeding these elements to animals results in increased concentrations in AMs11,12. However, in Iran, there is no standard or guideline like the European Union for the addition of copper, zinc, and chromium to animal feed, so that the aforementioned additives may often be provided in excess of the animals’ needs in Iran.

Despite the importance of the emerging pollutants (EPs), there is limited information on their residues and fate in AMs in Iran. Investments in waste recycling and conversion, particularly the production of organic fertilizers, have shown significant long-term benefits and should be prioritized as part of sustainable development efforts13.

Interestingly, Kerman, Iran, has the only biochar mine in the country, a prehistoric resource dating back 650 million years.

On the other hand, no study has been conducted so far on the effect of the noted biochar on the reduction or elimination of emerging and toxic compounds in the composting process of livestock and poultry manure in a combined form. This economic biochar is found abundantly in the mines of Kerman province, and given that it has a lower carbon content than other produced biochars, it is expected that it will not have an undesirable effect such as scaling on the soil in the long term. Therefore, in the current study, an attempt has been made to investigate the physicochemical properties, the presence of emerging pollutants, and their ecological effects in animal compost mixed with biochar.

Materials and methods

Source and characteristics of compost materials

Pea straw (PS) was sourced from pea fields in Kermanshah city, Iran and crushed into 1–3 cm pieces. CWM and PUM were obtained from cow and poultry farms in Kermanshah. The physicochemical properties of the raw materials are presented in Table 1. Powder of Natural mineral biochar (NMB) was sourced from a natural mine in Kerman, Iran, that is entirely natural and, according to geological studies, was formed through natural processes approximately 650 million years ago14.

Experimental setup and composting process

Composting was conducted using a galvanized bioreactor with intermittent aeration and mixing (IAMBR) over 60 days. The IAMBR had a vertical oval cross-section (H: 50 cm, L: 60 cm, W: 30 cm, freeboard: 15 cm) and was equipped with four sharp-edged agitators (L: 54 cm, W: 6 cm, RPM: 24). Ambient humidity and temperature, as well as chamber temperature, were monitored using an online thermometer and hygrometer kit (HTC-2, China) installed on the IAMB.

Aeration was provided by an electromagnetic aeration pump (Aqua AP-9805, China) with a power rating of 6.5 W, a pressure of over 0.025 MPa, and an output flow rate of 5.5 L/min. The pump supplied air to 15 aeration diffusers installed along the bottom sides of the BR. Aeration was automatically controlled using a dial timer (Zhejiang, China) set to operate five times daily for 20 min.

To homogenize the compost pile, mixing was performed daily using the four agitators. The pile’s core temperature was measured three times daily before turning the pile using a digital thermometer (TP101, China). Compost turning was performed every two days, alternating between fresh and mature compost.

Twelve treatments (T1–T12) (Table 2) were tested to evaluate the effects of NMB (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%) and CWM:PUM (1:1, 1:3, 3:1), as detailed in Table 2. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) and moisture content were adjusted to 24–25:1 and 60%, respectively.

Samples (600 g) were collected on days 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 using a five-point sampling method to ensure representative samples from the early mesophilic, thermophilic, secondary mesophilic, and maturation phases.

Physicochemical analysis

The collected samples were dried, ground, and stored, then divided into two portions: one portion was used to determine the physicochemical properties, while the other was air-dried, ground, and stored at 4 °C for HMs and chemical properties analysis. The pH was measured by mixing the samples in a 1:10 ratio with water and allowing the mixture to sit for 0.5 h before using a pH meter. Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined using the modified Walkley–Black wet oxidation method15. Total nitrogen was analyzed through the Kjeldahl digestion method using an automatic Kjeldahl apparatus, while nitrate levels were measured following the method described by16. Heavy metals, including copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), and zinc (Zn), were extracted using acid digestion with sulfuric acid and quantified via atomic absorption spectrometry17.

Ecological risk assessment

The ecological risk potential of Cu, Cr, and Zn was calculated following the approach outlined by Negahban et al.18:

Cf = Contamination factor, for zinc, copper and chromium is 175, 50 and 90 mg/kg, respectively19.

Tr = Toxicity index, for copper, chromium and zinc is 5, 2 and 1, respectively.

Er = Ecological risk potential index.

RI = Ecological risk of the total metals.

Where

RI values less than 150, 150–300, 300–600 and more than 600 indicate low risk, moderate risk, significant (high) risk and very high risk, respectively.

Er values less than 40, 40–80, 80–160, 160–320 and more than 320 indicate low risk, moderate risk, significant risk, high risk and very high risk, respectively20.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software, applying the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to assess data normality, parametric and non-parametric tests, and Pearson correlation coefficients, with a significance level of 0.05. Microsoft Excel was used for data organization, Grapher for graphing, and Design-Expert software for response surface methodology analysis at three levels (− 1, 0, + 1) for CWM/PUM (factor A) and NMB (factor B).

Results

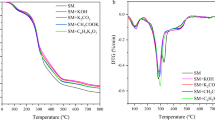

Change in pH

Initially, the pH of the compost was neutral but increased over time, reaching the alkaline range during the curing stage (Figs. 1 and 2a) (P < 0.05). Treatments with NMB and a higher proportion of CWM exhibited relatively higher pH values compared to T1–T5 (P < 0.05). While the initial pH was not significantly affected by the amount of NMB and the CWM/PUM ratio (P > 0.05), the final compost showed a greater influence of NMB (P < 0.05) (Table 3). Among the treatments, T2 exhibited the smallest pH changes at the beginning and the end of the process, while T6 and T7 showed the largest variations.

Change in temperature

The overall temperature trends in all treatments followed a similar pattern. Initially, the compost pile temperature ranged between 20 and 40 °C. It then entered the thermophilic phase, reaching 40–60 °C, before cooling down as mesophilic bacteria resumed activity, bringing the pile temperature closer to ambient levels (Figs. 2 and 3). The retention time at high temperatures increased with higher NMB levels and lower CWM/PUM ratios (P < 0.05). The cumulative temperatures (°C) recorded for treatments T1–T12 were 897, 858, 836, 981, 926, 898, 1007, 999, 959, 1056, 1025, and 972, respectively. The thermophilic phase lasted 14, 16, and 16 days for piles containing 75% PUM combined with 5%, 10%, and 15% NMB, respectively. The shortest thermophilic phase duration (9 days) was observed in T3, while the longest (16 days) occurred in T10 and T7 (Fig. 3).

Fate of carbon

On the first day of composting, TOC concentrations ranged from 40 to 42.32% (Fig. 4a). As the decomposition process progressed, TOC levels decreased significantly (P < 0.05). NMB had a notable effect on TOC reduction (P < 0.05), while the CWM/PUM ratio did not significantly influence TOC reduction (P > 0.05). However, higher CWM content was associated with smaller TOC reductions (Figs. 2c and 4a). TOC levels in the control group differed significantly from those in the other treatments (P < 0.05). During the stability phase, TOC reduction efficiencies were highest in T10, T11, and T12 at 39%, 38.51%, and 35.01%, respectively, and slightly lower in T7, T8, and T9 at 43.39%, 42.39%, and 41.84%, respectively. Treatments containing 15% NMB exhibited a lower rate of TOC reduction compared to those with 5% or 10% biochar (P < 0.05). The piles with 15% NMB also had the highest initial organic carbon content.

Fate of nitrogen compounds

NH4 +–N/NO3⁻–N

The NH4+–N/NO3⁻–N ratio in treatments T1–T12 ranged between 1.96 and 1.58 (Fig. 2d and 4b). Over time, the NH4+–N/NO3⁻–N ratio increased during the first 15 days and then began to decrease, with the most significant decrease observed in piles containing 15% NMB. A significant difference in nitrate levels was detected between treatments with 10% and 15% NMB compared to those with 5% NMB and between treatments with and without NMB (P < 0.05). A significant negative correlation was observed between the decrease in the NH4+–N/NO3–N ratio and NMB content (P < 0.05). However, the CWM/PUM ratios of 1:3, 3:1, and 1:1 showed no significant effect on this ratio (P > 0.05).

Total nitrogen kjeldahl

In this study, the total nitrogen (TKN) concentration was affected by NMB and CWM/PUM (Fig. 5). During composting, the TKN in all treatments had a similar trend, decreasing significantly until the thermophilic stage and then increasing, and was maintained within a small range of fluctuation at the end of the period. The final TKN concentration in percent for treatments T1–T14 was 1.42, 1.4, 1.57, 1.71, 1.7, 1.62, 1.64, 1.7, 1.51, 1.6, 1.49, 1.65, 1.71, and 1.78, respectively. Compared with the control group, the addition of NMB significantly increased the TKN (P < 0.05). TKN content was significantly positively correlated with the number of days of composting (P < 0.05).

Fate of Heavy Metals (HMs)

In this study, the changes in heavy metals were examined under the optimized CWM: PUM ratio of 1:3 and varying NMB levels (0%, 5%, 10%, and 15%) (Fig. 6).

At the start of the process, the Zn concentrations in treatments T1, T4, T7, and T10 were 197.15, 336.32, 287.53, and 244.16 mg/kg, respectively. By day 60, these concentrations had decreased to 185.78, 296.14, 197.52, and 129.58 mg/kg, respectively. Similarly, Cu concentrations in T1, T4, T7, and T10 were initially 240.25, 127.63, 97.4, and 189.55 mg/kg, respectively, and declined to 228.31, 109.36, 76.11, and 131.5 mg/kg in the final compost.

Cr concentrations in the control treatment began at 26.12 mg/kg and remained largely unchanged in the mature compost. However, in treatments containing 5%, 10%, and 15% NMB, Cr concentrations decreased to 6.76, 12.15, and 7.05 mg/kg, respectively, representing a significant reduction. The removal efficiency rankings varied across treatments: in control, Zn > Cu > Cr, in 5% NMB: Cr > Cu > Zn, and in 10% and 15% NMB: Zn > Cr > Cu.

A positive correlation was observed between pH and HM removal efficiency, with increasing pH enhancing the removal efficiency from the beginning to the end of the process. ANOVA results confirmed that removal efficiency differences between the control and other treatments were statistically significant (P < 0.05). NMB had a direct and significant positive effect on the removal of Zn, Cu, and Cr (P < 0.05). HMs exhibited a positive correlation with humification (Fig. 7).

Ecological risk assessment

The average contamination factor (CF) for zinc, chromium, and copper was 0.97, 0.27 and 2.44, respectively. The survey of the contamination degree (Cdegree) shows that T10 and T3 have low contamination (1.5 < Cdegree < 2) and other treatments have very low contamination (Cdegree < 1.5). The ER and RI parameters show that the studied heavy metals (individually and in total) have low risk in compost piles and are not considered a threat to the environment (Table 4).

Discussion

pH is a key indicator in composting as it affects the survival of microorganisms. With aeration and the improved decomposition of organic matter, microbial activity intensified, reducing the environment’s acidity and increasing the pH. Chen et al.21 reported that under favorable conditions, organic acids are completely decomposed, causing compost to transition from an acidic to a neutral range, aligning with the findings of this study. Biochar was also observed to increase pH due to the availability of mineral nutrients, which is consistent with the findings of Choudhary et al.22. Research suggests that pH values in the range of 5.5–8.0 are optimal for composting23, matching the results of this study. Similarly, Awasthi et al.24 found that using bamboo biochar (2–10%) in composting sheep manure led to a pH increase, further corroborating these findings. The final pH of the compost in this study complied with international standards25.

In general, temperature showed a significant positive correlation with NMB and a significant negative correlation with CWM/PUM. Treatments containing NMB exhibited a relatively higher heating rate and an extended thermophilic phase, indicating improved mineralization and compost maturity26. Maintaining temperatures above 55 °C for at least 3 days is crucial for eliminating pathogens and parasites in compost27. In this study, all treatments met standard hygiene requirements.

The findings of Afriliana et al.28 align with the current study, reporting a maximum composting temperature of 60 °C. The increased temperatures with higher NMB levels may be attributed to NMB’s high surface area and porosity, which facilitate oxygen transport and improve microbial proliferation conditions29. In contrast, Abd El-Rahim et al.30 observed a maximum temperature of 73.5 °C, with slower temperature increases. This difference might be due to cooler ambient conditions during autumn and winter.

Wang et al.31 reported that biochar addition resulted in higher temperatures for a shorter duration, with compost entering the cooling phase more quickly, which contradicts the results of this study. The duration of the thermophilic phase was also influenced by the CWM/PUM ratio. Higher PUM levels enhanced temperature retention and duration in the thermophilic phase, likely due to the nutrient content in PUM, which supports microbial activity and heat production.

Total organic carbon (TOC) is a critical parameter for evaluating compost quality. Various studies have reported similar trends, indicating an increase in TOC during the early stages of composting when NMB is introduced, despite the lower carbon content of natural biochar compared to other mineral biochar32,33. For instance, Awasthi et al.24 observed an increase in TOC from 45.83 to 49.97% with the addition of biochar.

During composting, some carbon is consumed and released as CO₂, while the remainder contributes to cellular structure formation alongside nitrogen34. TOC reductions occur due to mineralization and the formation of humic substances. In a study by Biyada et al.35, TOC followed a similar trend, decreasing from 32.64% at the start of composting to 23.53% in mature compost.

These findings suggest that treatments with higher biochar content experience reduced carbon losses because biochar’s carbon is resistant to decomposition and highly stable. Conversely, higher CWM/PUM ratios resulted in lower TOC reduction efficiency, likely due to decreased microbial activity associated with increased CWM content, which in turn affected carbon breakdown.

The conversion of organic nitrogen to inorganic nitrogen during composting is a potential mechanism for inhibiting the growth of host bacteria. The large surface area and high adsorption capacity of NMB facilitated nitrogen fixation, resulting in increased uptake of organic nitrogen ions by NMB and reduced nitrogen loss. However, nitrogen reduction trends were similar between biochar and non-biochar treatments, indicating a compensatory effect of biochar addition.

The increase in NH4+–N observed until day 15, concurrent with rising temperatures, may be attributed to the rapid decomposition of organic nitrogen compounds and relatively weak nitrification activity by nitrifying bacteria. This aligns with the findings of Li et al.36, who reported a significant increase in NH4–N in all treatments during the initial stages of composting as temperatures increased. A similar result was observed by Rong et al.37, who co-composted chicken manure and corn leaves.

The mechanisms underlying biochar-assisted reductions in NH4–N may include the high adsorption capacity of NMB. This capacity is attributed to the large specific surface area and internal pore volume of NMB, as well as the presence of surface acidic functional groups, cation exchange sites, and micropores, which collectively limit the release of NH4–N during composting29.

Agyarko-Mintah et al.38 demonstrated that NH3 adsorption primarily occurs within the pore spaces of biochar. Additionally, NMB enhances aerobic conditions, supports the proliferation of aerobic nitrifying bacteria, and provides a habitat for microorganisms, further aiding in NH4–N retention and overall compost efficiency39. During the bio-oxidation stage, the NH4–N/NO3–N ratio fluctuates due to competition between ammonification and nitrification40. The decrease in NH4–N and the simultaneous increase in NO3–N are attributed to the rapid conversion of NH4–N to NO3–N by nitrifying microorganisms 41. Proteins, amino acids, and other organic materials are initially used by microorganisms as energy and nitrogen sources. Once these materials are depleted, the NH4–N formed during microbial deamination becomes unstable, evaporates as ammonia gas, and is partially converted to NO3–N by ammonia-oxidizing microbes 42. Since nitrifying bacteria cannot grow at temperatures above 40 °C, nitrification primarily occurs during the cooling and compost maturation stages. Bernal et al. 25 reported that an NH4–N/NO3–N ratio below 0.16 is an indicator of compost maturity. The National Standards Organization of Iran defines an acceptable NH4–N/NO3–N ratio range of 0.5–3.0 for grades 1 and 2 compost.

In the aerobic composting process, the total nitrogen content of the pile affects the degree of compost decomposition and is used to evaluate the quality of compost products, so the change in the total nitrogen content in a compost pile can be used as another important indicator of the degree of compost maturation 43. The activity of microorganisms causes the reduction of nitrogen in the compost, the mineralization of organic nitrogen, the denitrification of nitrate, and the release of ammonia, which together cause the reduction of nitrogen 44. However, in the decomposition of compost, a large amount of organic matter is converted into CO2, and the release of ammonia is relatively small. Therefore, at the end of composting, the total nitrogen content of the compost pile had an upward trend compared to the initial value, which may be due to the fact that the rate of decrease in the total nitrogen content is less than the rte of decrease in the total dry matter weight33.

TKN decreased slowly in the early mesophilic stage, but increased rapidly in the thermophilic stage, which progressed to a steady state. The increase in TKN in the later stages in all treatments was probably due to the continuous decomposition of organic compounds, loss of CO2 and water moisture due to heat generation during the oxidation of organic matter34. Nitrogen transformation in compost mainly involves ammonification, nitrification and denitrification reactions45. On the other hand, the treatment containing NMB showed significantly higher nitrogen values compared to the treatment without NMB during the composting. This suggests that biochar may have created a suitable environment for nitrifying bacteria, which can convert ammonia to nitrate, thereby helping to retain nitrogen in the compost matrix46. Final TKN was positively correlated with NMB content, with the highest value indicating the richest nutritional conditions in the 10 and 15% amended composts. These changes showed a significant positive effect of biochar amendment on reducing nitrogen losses.

Shan et al.47 observed a slight reduction in total nitrogen with increasing NMB levels. Similarly, Steiner et al.48 found comparable nitrogen losses in PUM composting with 5% or without NMB, but in piles with 20% biochar, nitrogen loss was significantly reduced by up to 52%.

The study of HMs in AMs provides valuable insights into their bioavailability and environmental pollution potential. HMs are non-degradable and can persist in manure and compost, leading to their accumulation with long-term application4. NMB reduces HM bioavailability through adsorption and fixation. By adsorbing nutrients in its micropores, biochar reduces the efficiency of organic pollutant degradation, blocking microbial contact and enhancing HM removal49.

Another mechanism contributing to the inactivation of HMs is biochar adsorption, which involves physical trapping in micropores and the formation of complexes between Zn, Cu, and Cr and the functional groups on biochar, such as –OH, –COOH, and C–O50. For cations, the primary mechanisms include surface precipitation with anions on NMB, the substitution of exchangeable cations, and the formation of surface complexes with –OH groups or delocalized π electrons from biochar51.

The pH changes in compost with biochar influence the complexation behavior of functional groups such as –OH, –COOH, and –NH₂, which play a role in metal adsorption. Electrostatic interactions and cation exchange are identified as the dominant mechanisms of metal adsorption by biochar52. Increasing NMB from 5 to 15% significantly enhanced the immobilization of HMs.

A one-sample t-test revealed that the concentrations of Zn, Cr, and Cu in the final compost were significantly lower than the standards set by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)53. Humification is a critical process in reducing the bioavailability of HMs during aerobic composting. In this process, metal cations combine with organic acids and polymerize into stable humic substances54, supporting the findings of this study.

Humic molecules are rich in carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, which form stable complexes with metal cations. During aerobic composting, the mineralization and humification of organic carbon regulate the bioavailability of HMs. Metal cations released through organic carbon mineralization can react with organic acids, forming more stable complexes55. Similarly, during dehumidification, metal cations readily combine with organic acids to form stable complexes, as adsorbed inorganic cations reduce competition with metal cations. In summary, biochar enhances the deactivation of Zn, Cu, and Cr primarily through surface adsorption mechanisms, significantly contributing to the reduction of their bioavailability. The contamination factor (CF) for Zn was highest in T4 and lowest in T10. In general, the CF of Cr was much lower than that of Cu and Zn (CF: Cu > Zn > Cr). Contamination degree (Cdegree) revealed that treatments T4, T7, and T10 exhibited very low contamination (Cdegree < 1.5), while the control treatment (T1) showed low contamination (1.5 < Cdegree < 2)56. The ecological risk (ER) and risk index (RI) parameters indicate that the studied heavy metals, both individually and collectively, pose a low risk in compost piles and do not threaten the environment.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the significant role of NMB in optimizing the composting process of cow and poultry manure. The addition of NMB significantly enhanced the removal efficiency of heavy metals (Zn, Cu, and Cr), reducing their bioavailability and mitigating associated environmental risks. Treatments containing higher NMB (10–15%) exhibited the most effective pollutant immobilization and nutrient stabilization, while meeting international safety standards, including the US EPA.

The findings emphasize that NMB improves compost quality by facilitating microbial activity, enhancing adsorption, and stabilizing nutrients through mechanisms such as surface complexation, electrostatic interactions, and pH regulation. Environmental risk assessments confirmed that composting transitions raw manure with medium to high risks into safer compost products with low or free risk.

These results highlight the potential of NMB as a sustainable and eco-friendly solution for managing AMs while addressing emerging pollutants. Animal manure may contain antibiotics and heavy metals, some of which have moderate to high environmental risks, but composting can reduce these risks. Finally, the compost produced in this study was assessed as safe and can be used as agricultural fertilizer, but precautions should be taken regarding contamination. These results indicate the importance of developing regulations for manure pretreatment and controlling biological and chemical contamination. The importance of this study is the design and implementation of the pasteurized manure production process and the development and generalization of the studied process in small rural communities and small institutions. Among the limitations of this method were the consumption of electrical energy for mixing. Also, in unfavorable environmental conditions such as cold weather, the bioreactor cannot be operated well and requires a coverage.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript files.

References

Quaik, S. et al. Veterinary antibiotics in animal manure and manure laden soil: Scenario and challenges in Asian countries. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 32(2), 1300–1305 (2020).

Sharafi, S. & Salehi, F. Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal (HMs) contamination and associated health risks in agricultural soils and groundwater proximal to industrial sites. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 7518 (2025).

Liu, X., et al., Frontiers in environmental cleanup: Recent advances in remediation of emerging pollutants from soil and water. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 100461 (2024).

Zheng, X. et al. Review on fate and bioavailability of heavy metals during anaerobic digestion and composting of animal manure. Waste Manag. 150, 75–89 (2022).

De Silva, S. et al. Land application of industrial wastes: Impacts on soil quality, biota, and human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(26), 67974–67996 (2023).

Alengebawy, A. et al. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 9(3), 42 (2021).

Qian, X. et al. Heavy metals accumulation in soil after 4 years of continuous land application of swine manure: A field-scale monitoring and modeling estimation. Chemosphere 210, 1029–1034 (2018).

Fan, M.-S. et al. Evidence of decreasing mineral density in wheat grain over the last 160 years. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 22(4), 315–324 (2008).

Saravanan, P. et al. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources, identification, treatment strategies, and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 258, 119440 (2024).

Jomova, K. et al. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 99(1), 153–209 (2025).

Xue, J. et al. Occurrence of heavy metals, antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance genes in different kinds of land-applied manure in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(29), 40011–40021 (2021).

Wang, M., Liu, H. & Zhou, W. Chemical speciation, contamination, human health risk assessment, and source identification of heavy metals in soils composted with swine manure. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 34(4), 586–606 (2025).

Diaz, L. F. et al. Composting and Recycling Municipal Solid Waste (CRC Press, 2020).

Daraei, E., Bayat, H. & Gregory, A. S. Impact of natural biochar on soil water retention capacity and quinoa plant growth in different soil textures. Soil Tillage Res. 244, 106281 (2024).

Sikora, F. & Moore, K. Soil test methods from the southeastern United States. South. Coop. Ser. Bull. 419, 54–58 (2014).

Leege, P. B. & Thompson, W. H. Test Methods for the Examination of Composting and Compost (US Composting Council, 1997).

Hseu, Z.-Y. Evaluating heavy metal contents in nine composts using four digestion methods. Biores. Technol. 95(1), 53–59 (2004).

Negahban, S. et al. Ecological risk potential assessment of heavy metal contaminated soils in Ophiolitic formations. Environ. Res. 192, 110305 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Distribution and dispersion of heavy metals in the rock–soil–moss system of the black shale areas in the southeast of Guizhou Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(1), 854–867 (2022).

Lajmiri Orak, Z. et al. Investigation of Ecological Risk (ER) and Available Ratio (AR) of some heavy metals in drill cutting of Ahvaz Oil Field in 2019. J. Environ. Health Eng. 8(3), 329–342 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Effects of lime amendment on the organic substances changes, antibiotics removal, and heavy metals speciation transformation during swine manure composting. Chemosphere 262, 128342 (2021).

Choudhary, T. K. et al. Nutrient availability to maize crop (Zea mays L.) in biochar amended alkaline subtropical soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21(2), 1293–1306 (2021).

Ji, Z. et al. Evaluation of composting parameters, technologies and maturity indexes for aerobic manure composting: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 886, 163929 (2023).

Awasthi, M. K. et al. Effect of biochar on emission, maturity and bacterial dynamics during sheep manure compositing. Renew. Energy 152, 421–429 (2020).

Bernal, M., Alburquerque, J. & Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment. A review. Bioresour. Technol. 100(22), 5444–5453 (2009).

Jiang, Z., Zheng, H. & Xing, B. Environmental life cycle assessment of wheat production using chemical fertilizer, manure compost, and biochar-amended manure compost strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 143342 (2021).

Febrisiantosa, A., Ravindran, B. & Choi, H. L. The effect of co-additives (Biochar and FGD Gypsum) on ammonia volatilization during the composting of livestock waste. Sustainability 10(3), 795 (2018).

Afriliana, A. et al. Studies on composting spent coffee grounds by Aspergillus sp. and Aspergillus sp. in aerobic static batch temperature control. J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 10(1), 91–112 (2020).

Nguyen, M. K. et al. Evaluate the role of biochar during the organic waste composting process: A critical review. Chemosphere 299, 134488 (2022).

Abd El-Rahim, M. G. et al. Effect of biochar addition method on ammonia volatilization and quality of chicken manure compost. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 108 (4) (2021).

Wang, S.-P. et al. Biochar addition reduces nitrogen loss and accelerates composting process by affecting the core microbial community during distilled grain waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 337, 125492 (2021).

Zahra, M. B. et al. Mitigation of degraded soils by using biochar and compost: A systematic review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21(4), 2718–2738 (2021).

Zhan, Y. et al. Effects of different C/N ratios on the maturity and microbial quantity of composting with sesame meal and rice straw biochar. Biochar 3, 557–564 (2021).

Yan, R. et al. Soil decreases N2O emission and increases TN content during combined composting of wheat straw and cow manure by inhibiting denitrification. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 147306 (2023).

Biyada, S. et al. Advanced characterization of organic matter decaying during composting of industrial waste using spectral methods. Processes 9(8), 1364 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Veterinary antibiotics and estrogen hormones in manures from concentrated animal feedlots and their potential ecological risks. Environ. Res. 198, 110463 (2021).

Rong, R. et al. The effects of different types of biochar on ammonia emissions during co-composting poultry manure with a corn leaf. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 28(5), 3837–3843 (2019).

Agyarko-Mintah, E. et al. Biochar lowers ammonia emission and improves nitrogen retention in poultry litter composting. Waste Manag. 61, 129–137 (2017).

Wang, H.-K. et al. A review of research advances in the effects of biochar on soil nitrogen cycling and its functional microorganisms. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 38(6), 689–701 (2022).

Sun, R. et al. Effect of NH4+ and NO3− cooperatively regulated carbon to nitrogen ratio on organic nitrogen fractions during rice straw composting. Bioresour. Technol. 395, 130316 (2024).

Hoang, H. G. et al. The nitrogen cycle and mitigation strategies for nitrogen loss during organic waste composting: A review. Chemosphere 300, 134514 (2022).

Huang, D. et al. Carbon and N conservation during composting: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 840, 156355 (2022).

Tang, R. et al. Effect of moisture content, aeration rate, and C/N on maturity and gaseous emissions during kitchen waste rapid composting. J. Environ. Manag. 326, 116662 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Humus formation driven by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria during mixed materials composting. Bioresour. Technol. 311, 123500 (2020).

Liu, N. et al. Characteristics of denitrification genes and relevant enzyme activities in heavy-metal polluted soils remediated by biochar and compost. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 139987 (2020).

Gao, S. et al. Biochar co-compost improves nitrogen retention and reduces carbon emissions in a winter wheat cropping system. GCB Bioenergy 15(4), 462–477 (2023).

Shan, G. et al. Additives for reducing nitrogen loss during composting: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 307, 127308 (2021).

Steiner, C. et al. Reducing nitrogen loss during poultry litter composting using biochar. J. Environ. Qual. 39(4), 1236–1242 (2010).

Gholizadeh, M. & Hu, X. Removal of heavy metals from soil with biochar composite: A critical review of the mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(5), 105830 (2021).

Vithanage, M. et al. Kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanistic studies of carbofuran removal using biochars from tea waste and rice husks. Chemosphere 150, 781–789 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Preparation and modification of biochar materials and their application in soil remediation. Appl. Sci. 9(7), 1365 (2019).

Liu, C. & Zhang, H.-X. Modified-biochar adsorbents (MBAs) for heavy-metal ions adsorption: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(2), 107393 (2022).

U.E.P. Agency. Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, and Soils (USEPA, 1996).

Shan, G. et al. The transformation of different dissolved organic matter subfractions and distribution of heavy metals during food waste and sugarcane leaves co-composting. Waste Manag. 87, 636–644 (2019).

Piccolo, A. et al. Soil washing with solutions of humic substances from manure compost removes heavy metal contaminants as a function of humic molecular composition. Chemosphere 225, 150–156 (2019).

Urrutia-Goyes, R. et al. Insights on trace metal enrichments in tourists beaches of Santa Elena Province, Ecuador. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 73, 103452 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for its financial support (No. 4010775). The authors of the article would also like to thank Mr. Mohammad Majidi Kohbanani for providing natural mineral biochar.

Funding

Fundingwas provided by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 4010775).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M: Methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; A.A: conceptualization, supervisor, project administration; S.A.M: Advisor; P.M: Advisor; M.H: writing—original draft preparation in English.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, M., Almasi, A., Mousavi, S.A. et al. The fate of pollutants in the co-composting of natural mineral biochar and animal manures in an intermittent aeration and mixing bioreactor (IAMB). Sci Rep 15, 33225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18122-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18122-7