Abstract

This paper introduces an image classification-based technique for determining the moon’s age in a synodic month from a lunar picture. Before this study, no image classification-based approach has been applied for this purpose. Historically, mathematical methods have been employed for this determination, dating back to the Babylonian era. Our approach utilizes CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks) to analyze lunar images. We utilized a pre-trained ResNet18 architecture for transfer learning, leveraging its pre-trained weights to adapt to the new lunar dataset. The dataset was collected from Nasa’s moon phase and liberation website using the requests and selenium libraries. Finally, we trained and evaluated different models using accuracy metrics and confusion matrices. While experimenting in different experimental setups, the highest accuracy obtained in our study is 82.74%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Moon has fascinated and inspired humans throughout history. Ancient cultures celebrated it as a divine being1, while astronomers studied its phases, surface characteristics, and orbital dynamics2. The Moon is no mere satellite, but a vital determinant of Earth’s environment and biology, responsible for tides and weather patterns, including our own behavior and physiology. Indeed, many organisms, including humans, time their reproduction and foraging to the lunar cycle1.

Ancient civilizations were particularly attuned to this cycle; it influenced agricultural practices to religious rituals in a unique way. As inscribed in historical records, various civilizations practiced certain taboos, ceremonies, or celebrations around the lunar cycle3.

The lunar cycle consists of eight phases driven by the relative positions of the Sun, Earth, and Moon. It starts with a new moon, where the Moon lies between Earth and the Sun, leaving its near side dark. Next, we have the waxing crescent4, as sunlight begins to illuminate a sliver of the Moon’s surface. By the first quarter (half moon), half of the near side is visible. The waxing gibbous4 show more than half illuminated, leading to the full moon when Earth is between the Sun and Moon. As the Moon continues its orbit, the third quarter (last quarter) reveals the opposite half illuminated. The waning gibbous phase follows with a decreasing illuminated portion, and the waning crescent concludes the cycle, with only a small sliver visible before returning to the new moon phase. All eight different moon phases are shown in figure 1.

This complete cycle from one new moon to the next is known as a synodic month5, which takes approximately 29.53 days. The synodic month is fundamental to understanding lunar phases and forms the basis for many lunar calendars throughout history. During the synodic month, the Moon completes its full sequence of phases as it orbits around Earth relative to the Sun’s position.

It is important to note that when we refer to the Moon as being “N days old” (e.g., 5 days old), this refers to the number of days that have passed since the most recent new moon. For example, if the Moon is 5 days old, then the new moon occurred exactly 5 days ago. This terminology is crucial in discussing the age of the Moon during its phases.

Moon phases6.

The lunar cycle has been a key indicator of time, contributing to the structure of calendars, such as the Jewish lunisolar calendar7 and the Chinese lunar-solar calendar7, both of which developed from the observation of phases of the Moon. Although these earlier practices provided a valuable function in creating calenders, they had issues associated with errors derived from weather conditions and human interpretation. Although numerical models and science-based data now aid in determining lunar phases, the inherent visual connection found in historical practices is not present. The moon goes through a full synodic cycle that swells and wanes over the course of a synodic month. Although trying to discern a lunar day from an image was an ancient practice, it nonetheless had challenges associated with uncertainty of error.

To overcome these limitations, we propose a systematic automated approach to lunar phase identification and classification using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). CNNs are sophisticated and effective for image recognition and a natural means of detecting small differences between lunar phases. A custom data set was developed utilizing lunar images, obtained under various conditions, to train CNN showing greater accuracy than previously described methods.

Multiple variants of ResNet, including deeper architectures such as ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and ResNet-1528, have shown strong performance in various tasks. We chose ResNet-18 because of its favorable trade-off between model complexity and computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for our dataset size and experimental constraints. While deeper networks may achieve marginally better performance, they also introduce higher computational overhead and increased risk of overfitting, especially in settings with limited training data.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section “Introduction” provides an introduction and an overview of the importance of automated recognition of lunar phases using CNNs. Section “Related works” provides insight into the work related to traditional methods to the ML approach. Section “Methodology” presents the details of our study, such as data collection and augmentation methodology, CNN curation. Section “Results” describes our experimental results and model evaluation. Sections “Conclusion” and “Future work” conclude this work with key takeaways and give future work directions.

Related works

Lunar age estimation has historically relied on mathematical calculations. Ancient Greek astronomers such as Hipparchus and Ptolemy laid the foundation for understanding lunar motion and predicting phases9. During the Islamic Golden Age, scholars like Al-Battani and Al-Biruni extended this work to refine the lunar calendar and study lunar phases10,11, particularly in the context of the Hijri calendar, which consists of twelve lunar months.

This tradition of mathematical precision was carried forward into the Renaissance and modern era, with luminaries such as Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton revolutionizing our understanding of the moon and celestial mechanics through their groundbreaking calculations and formulas12.

In recent years, advances in computational methods have augmented this legacy, introducing new tools to understand and predict lunar phenomena. For example, the use of pattern recognition artificial neural networks (ANNs)13 for the prediction of new crescent visibility [cite 9]. In one of such studies, Allawi14 trained an ANN on a data set collected for Iraq consisting of parameters for the sighting of crescent moons. Similar calculations related to Hirji calender can be found in the article presented by Ahmed et al.15.

Expanding on these insights, Al-Rajab, Loucif, and Al Risheh explored machine learning techniques to predict the visibility of the crescent moon in 202316. They applied eight common classification algorithms, with the Decision Tree and Random Forest algorithms providing the highest accuracy of 93% in predicting the visibility of the crescent.

Similarly, Tafseer Ahmed, in his paper, predicted the visibility of the first crescent17, employed a machine learning approach to determine whether the first crescent of the lunar month would be visible to the naked eye on a given date.

Samia et al.18 introduce a machine learning framework designed to standardize lunar calendars worldwide by accurately predicting the visibility of the new crescent moon. The study used a comprehensive dataset that spans 13 years and covers various global regions, analyzing the 12 lunar months. The authors applied diverse machine learning techniques, including feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, ensemble learning, and region-based clustering, to enhance model performance. Among the models evaluated, the Gradient Boosting (GB) model achieved the highest F1 score of 0.882469 and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.901009. However, after feature selection and optimization, the Extra Trees model demonstrated superior performance with an F1 score of 0.887872 and an AUC of 0.906242. The ensemble model further improved performance, reaching an F1 score of 0.888058 and an AUC of 0.907482. Geographical segmentation of the dataset also enhanced predictive accuracy in specific regions, such as Africa and Asia. The findings suggest that machine learning techniques can effectively predict new crescent moon visibility, supporting the establishment of a globally unified lunar calendar18.

The SAZ algorithm steps & brief19.

Moshayedi, Chen, Liao and Li, in their paper ’Sunfa Ata Zuyan (SAZ) machine learning models for moon phase detection: algorithm, prototype and performance comparison’19, proposed an eight-step algorithm called SAZ (shown in Fig. 2) to determine the lunar phase from an image. Notably, also evaluated the performance of their algorithm on a Raspberry Pi, exploring the feasibility of a portable system. Their SAZ algorithm involves key steps such as isolating the region of interest, noise cancelation, and edge detection using a Canny filter19. After detecting the moon’s edge, they locate its center and draw concentric circles within it, ultimately calculating the lunar phase based on these measurements.

Compared to others, Fakhar, Moalem, and Badri utilized image processing algorithms in their paper, ’Lunar Crescent Detection Based on Image Processing Algorithms’20. Their methodology focuses on enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio and applying Circular Hough Transforms (CHT) to determine whether a crescent is present in an image.

Wahyuni et. al21explores the development of a mathematical model to predict the Islamic calendar’s months by analyzing lunar phases. The authors utilized Fourier and Moon Phase functions to approximate the lunar cycle, aiming to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the Islamic calendar system. Salih Hamza Abuelyamen presented a mathematical approach to align the Islamic (Hijri) calendar with the Gregorian calendar22. The author hypothesizes that every 300 solar years correspond exactly to 309 lunar years, based on interpretations of Quranic verses. This hypothesis serves as the foundation for developing a Hijri calendar that accurately aligns with the Gregorian system. The research aims to provide a stable and reliable Hijri calendar, correct past Islamic event dates, and predict future Islamic practices. The methodology includes detailed steps for constructing the Hijri calendar and its conformance with the Gregorian calendar, offering a comprehensive understanding of the subject22.

Following a similar approach, Sejzei and Jamzad in their paper, evaluation of various digital image processing techniques to detect critical crescent moons and introduction of CMD, a tool for critical detection of crescent moons23, employed image processing techniques to detect the crescent moon.

However, it is important to highlight the methodological distinctions between these works and ours. Although these studies used numerical data to make predictions as to when the new crescent will be visible on a specific date, our approach leverages convolutional neural networks (CNNs)24 to directly analyze images. By entering an image of the moon, we determine its age, emphasizing an image-processing-based methodology rather than prediction through numerical data. What distinguishes our work is the application of CNNs to a domain-specific and relatively underexplored problem, automatic moon phase classification, and our demonstration that CNNs can effectively replace traditional pipelines that rely on edge detection followed by handcrafted feature extraction and rule-based classification. In addition, we designed and evaluated our CNN model on a real-world dataset with natural variations in illumination, phase overlap, and noise, conditions under which traditional edge-based methods often fail.

Methodology

The primary objective of this research is to train an optimized CNN capable of accurately determining the lunar day of the synodic month.

Data collection

One of the significant challenges in this research was finding a suitable dataset containing lunar images with metadata corresponding to the moon age. To our knowledge, such a dataset had never been made publicly available. Consequently, we resorted to scraping data from NASA’s Moon Phase and Libration Visualization Studio25—a platform that provides visualizations of the moon, including relevant metadata like age.

Using Selenium26 and the requests library in Python, we developed a script to interact with NASA’s API27, which serves these visualizations along with their metadata in JSON format. The script generated dates from August 1st, 2024, back to January 1st, 2011 (the earliest available visualizations). For each day, individual API requests were made, retrieving the corresponding JSON data, which included the moon’s age and a link to the visualization. A demo snippet is shown in Fig. 3 using the Dial-A-Moon website of NASA [cite 16].

The visualizations were then classified by lunar day, with images of the same moon age stored in the corresponding 30 folders. The images have 30 classes (Days 1 to 30) in the Moon Phase and Libration Visualization Studio of NASA25. The detail numbers of images are provided in Table 1. Addition to the training and testing data, an external validation set comprising one year worth of lunar images across all classes was used.

We conducted a systematic search in various astronomical databases and archives, such as Google’s Dataset Search28, to identify lunar images that could enhance our dataset. Although numerous sources offered images, many were deficient in the necessary metadata, particularly the day of the synodic month, required for accurate labeling. Therefore, we prioritized sources that provided comprehensive documentation of their images.

To expand our way of working with lunar imaging, we reached out to professional and amateur astronomers to see if they had data sets that they were using that were privately held. Although we received very little response on any dataset for analysis, acquiring textbooks, other forms of constructs, as well as shared formula papers provided useful guidance on how to develop our own datasets.

Since we were developing our own dataset, it was essential to apply rigorous data cleaning practices. Our process was largely manual, focusing on identifying and eliminating redundancy, correcting labels, and removing low-quality images.

Data pre-processing

After gathering all the images, we applied data augmentation to artificially expand the dataset. Care was taken to avoid augmentations that could alter the moon’s age, such as flipping or rotating the images. We utilized the image libraries29 in Python to implement enhancements such as scaling, adding Gaussian noise, and blurring. Some images were augmented using combinations of these techniques based on a fixed seed30.

One of the primary goals was to simulate the appearance of lunar images captured with modern mobile phones, since a potential use case of our model was to develop a web app where users can take a photo of the moon and receive a predicted age.

Ultimately, our best-performing model was trained on all collected and augmented images, which included a total of 20,428 pictures. The training and validation data consist of grayscale images of the moon captured across 30 lunar days, stored in a structured directory format (day_number/image.jpg). This structure allowed us to automatically infer labels based on directory names.

The dataset includes variations in brightness, resolution, noise, and surface detail. To enhance generalizability, we used FastAI’s built-in augmentation via Resize(224) to normalize input size and applied additional image transformations using imgaug.

Annotation was inherent to the structure of the data set, as the label of each image was the lunar day of capture. An independent validation set, collected from different sources and unseen during training, was used to assess performance.

Convolutional neural network models

We used a stratified method to ensure that the training, validation, and testing splits of the data set proportionally represented all synodic month days, creating better training conditions for generalization. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are well suited for image classification tasks because of their ability to recognize spatial hierarchies in image data, making them ideal for capturing distinct lunar features.

These methods were crucial in refining the dataset and enhancing our CNN’s performance, enabling it to improve in estimating the given synodic day across diverse conditions. The model hyperparameters are provided in the result section.

Results

In our research, we tested various models using data sets created with NASA lunar images. Our principal goal was to classify the lunar day based on visual data, and we explored multiple approaches to optimize performance.

Model 1: two years of data and augmentations

The first model we trained used two years worth of lunar images, including their augmentations. This model was trained over 80 epochs, after which the performance started to plateau. The results yielded the following metrics shown in Table 2.

These metrics indicate a solid baseline performance, especially given the extensive data augmentation. Precision, in particular, was slightly higher than accuracy, suggesting that the model was better at minimizing false positives.

Model 2: Grayscale and binary thresholding

To explore whether simplifying the image data would enhance the results, we applied grayscale and binary thresholding techniques to the dataset. We trained the model for 100 epochs this time, recording the following results, shown in Table 3.

Interestingly, despite grayscale and thresholding, accuracy dropped slightly compared to the first model. Precision saw a minor improvement, but recall and F1 scores remained fairly close to the first model. This suggests that while simplification helped reduce false positives, it did not necessarily translate to better overall performance.

Model 3: lowering epochs on Grayscale images

Given the mixed results, we decided to reduce the number of epochs to 80 to match the first experiment. This resulted in a noticeable improvement in all metrics, shown in Table 4.

Reducing the number of epochs led to a better balance between precision and recall, with an overall improvement in accuracy. This model demonstrated the value of controlling overfitting, as the earlier experiment with 100 epochs likely led to diminishing returns.

Testing on new data

To evaluate how well these models would perform on unseen data, we tested the third model on a set of lunar images from 2018 that were not part of the training set. When tested on the exact prediction of the lunar day, the model achieved a 60% accuracy. However, allowing for a one-day error margin (for example, considering days 11 and 13 correct if the true day is 12), the precision increased dramatically to 98%. This substantial improvement suggests that the model captures lunar patterns well, but some noise or variability in the images might slightly misalign the exact prediction.

Final model—large dataset from 2011–2024

Our final and most comprehensive model used data from January 2011 through July 2024, totaling 21,000 augmented lunar images. Figure 4 shows the learning rate versus the loss plot of the final model.

This model, trained over 100 epochs, yielded the best results on all metrics, shown in Table 5. The comparative analysis is presented in Fig. 5 and Table 6.

The higher metrics across the board suggest that it generalizes well, and the improvement in precision and recall highlights its robustness in minimizing false positives and false negatives. This final model is used for our web demo.

Figure 6 shows an excerpt of our dataset. The number above the images represent the day of the month.

Discussion of results

Throughout the training of these models, it became clear that while increased data volume and augmentations can enhance performance, careful tuning of epochs and pre-processing techniques (like grayscaling) is crucial. Although adding more epochs helped initially, overtraining on the data began to reduce model performance, especially on unseen data.

Performance in the 2018 data set, particularly the jump from 60% to 98% accuracy when allowing a \(\pm 1\) day leeway, underscores the model’s ability to understand the moon’s growth path, even if minor visual variations occasionally skew exact predictions. This flexibility in lunar phase recognition supports the practical usage of our model in applications where a slight margin of error is acceptable.

To make the comparison easier to understand, the differences in performance between the CNN models mostly come down to the quality of the data used and how the models were trained. Model 1 used two years of images with added variations (called augmentations), but the mixed quality of the data and too much variation may have confused the model a bit, hurting its accuracy. Model 2 changed the images to black-and-white and applied a technique called thresholding, which helped remove noise but also got rid of some useful details, slightly lowering its performance. Model 3 used black-and-white images too but trained for fewer cycles (epochs), which may have helped avoid overfitting and improved the results. The final model did the best overall because it used the largest collection of images, allowing the CNN to learn more useful patterns. This shows that having more and better-quality images helps CNN models perform better.

As shown in Table 6, the Final Model consistently outperforms the others in all evaluation metrics. This improvement can be attributed to its more advanced architecture, which likely incorporates enhanced feature extraction mechanisms, better regularization, or a more effective learning strategy compared to previous models. For instance, the Final Model achieves an F1 score of 0.8279, surpassing Model 3 (0.8094), indicating an improved balance between precision and recall. The performance gap between the Final Model and Model 1 (F1-Score: 0.7879) suggests that incremental improvements in model design significantly contribute to the overall predictive capacity. These results highlight the importance of architectural refinements and optimization techniques in improving the performance of the model for the given classification task.

The reason we are getting such results lies in the movement of the moon through space. The moon shows different aspects as it moves through space. These are called librations, namely optical libration, libration in longitude and latitude, parallax libration, and physical libration. The concepts are presented briefly below.

-

Optical Libration: The apparent ’wobbling’ movement of the Moon as seen from Earth, caused by a combination of longitudinal and latitudinal libration. Optical libration allows us to see slightly beyond the normal visible edges of the Moon during its orbit.

-

Libration in Longitude: This occurs because the Moon’s orbit around Earth is not perfectly circular (it is elliptical). As a result, Moon rotation can lead or lag behind its orbital motion, allowing us to see slightly more of its eastern or western sides at different points in its orbit.

-

Libration in Latitude: This type of libration is due to the Moon’s axis of rotation being slightly inclined (about \(6.7^{\circ }\)) relative to the plane of its orbit around Earth. It allows us to occasionally see beyond the north and south poles of the Moon.

-

Parallax Libration: This Libration depends on the observer’s location on Earth, both in terms of longitude and latitude. As observers move to different points on Earth, the apparent position of the Moon changes slightly, allowing for a slight change in the visible lunar surface.

-

Physical Libration: The Moon’s actual physical oscillation, happening due to variations in its rotation and precession. These oscillations affect all three of the Moon’s axes but are very small, typically amounting to less than 1 second of arc as seen from Earth.

Another important point to consider is that the Moon’s orbit around Earth is elliptical. This means that at certain points in its orbit, the Moon appears closer to Earth, while at other points it appears farther away. This leads to phenomena like the supermoon, where the Moon is closest to Earth (at perigee, the point in its orbit where it is closest to Earth) while being in the phase of a full moon. This causes the Moon to look much bigger than on other days. We recently observed this phenomenon in August[reference, add date].

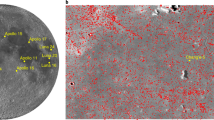

This leads us to an important observation: the percentage of the Moon’s illumination for the same day of different synodic months can vary significantly. In Fig. 7 we can see the differences between different dates. Let us break this down with examples:

-

On June 13, 2024, the Moon was 7 days old, and its illumination was 43.7%.

-

On May 15, 2024, the Moon was also 7 days old, yet the illumination was slightly higher at 47%.

-

On July 22, 2023, the Moon was 5 days old with an illumination of 21.5%.

-

On March 15, 2024, the Moon was again 5 days old, but the illumination was 31.84%.

-

On March 14, 2024, the Moon was 4 days old with an illumination of 21.96%, almost identical to the 5th day of the moon on July 22, 2023.

This variation highlights a critical challenge for our model: The Moon does not grow at a consistent rate across different synodic months. As a result, we sometimes provide data that might seem confusing to the model, since the same lunar day can show different illumination levels depending on the month. This inconsistency helps explain the significant improvement 38% in precision when we allow a margin of error of ± 1 day in our predictions.

Another important consideration is the performance gap in the model when images are captured using lower-quality cameras, such as those found on modern smartphones. The model was primarily trained on high-quality NASA images, and while it performs well with these, there is no way to accurately quantify how it would perform on datasets built with non-NASA images. Such data sets do not currently exist, and therefore, it is difficult to assess the generalizability of the model to these scenarios.

In fact, one of the most challenging aspects of this project was the determination of how to build a data set. Since a comprehensive and reliable lunar dataset was not available, we had to invest significant effort into collecting and curating data to train the model effectively. This limitation underscores the challenges of applying the model to real-world images taken from everyday devices, where factors such as image resolution, noise, and lighting conditions could degrade model performance.

Comparative assessment of edge detection methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed CNN-based moon phase recognition method, we performed a comparative assessment with traditional edge detection techniques commonly used in image analysis tasks. Specifically, we implemented the Canny31 and Sobel edge detection algorithms32 followed by a classical classification pipeline using hand-crafted features (e.g. shape descriptors, histogram of oriented gradients(HOG)33) and a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier34. Although these traditional approaches demonstrated moderate success in distinguishing clear moon phase boundaries, they were notably sensitive to variations in lighting conditions, occlusion, and background noise. The CNN model, in contrast, achieved superior performance by learning robust hierarchical features directly from the image data, enabling it to generalize better across diverse conditions. Quantitatively, CNN outperformed edge-based methods by a significant margin in terms of classification accuracy (e.g., CNN: 82.74%, Canny+SVM: 75.83%, Sobel+SVM: 72.15%). These results highlight the advantages of deep learning approaches over classical edge-based techniques for the task of moon phase recognition.

Variability of label based on user’s location

The moon looks different depending on the hemisphere from which we are observing it from. We are based out of Canada, which is in the northern hemisphere. So, for our results to be valid in the southern hemisphere, the pictures would have to be flipped on their x-axis.

Model hyperparameters

The hyperparameters of the CNN and Resnet18 model are provided in table 7 and 8. For generalizability and reproducibility of the model, we tuned the default settings.

Computation costs of methods

For a comparison of the computation costs of the methods used in this study, we have used one of the popular floating-point operations metrics (FLOP)35,36. FLOPs quantify the total number of these calculations required to process a single input, such as an image. A floating-point operation refers to any mathematical computation that involves decimal numbers. In neural networks, such operations are heavily used, especially in layers like convolutional and fully connected layers. We used the Python ptflops package37 that calculates the theoretical number of multiply-add operations required by a neural network. In addition, it can estimate the total number of parameters and display the computational cost for each layer of the model. The FLOPs values (in Giga) along with the parameters (in Millions) are shown in Table 9.

Conclusion

The inquiry into lunar cycles has remarkable historical significance, intertwined with human culture and scientific exploration. In this study, we presented a new technique for determining the age of a moon in a synodic month of the lunar phase via Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Using a dataset composed of 20,428 images obtained from NASA’s Moon Phase and Libration Visualization Studio27, our procedure was able to resolve the disparity between lunar descriptive observation and contemporary practices in computing the day of the lunar month.

The findings demonstrate that CNNs can accurately discriminate visual lunar images, within a certain range. These findings are a significant alteration from the historical situation of relying on mathematical descriptions and human inspection to identify lunar phases. The fact that the model gave reasonable results with variable images suggests potential for deep learning techniques for astronomical-based applications.

The findings of this paper established that machine learning techniques, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), can be employed effectively in remote sensing lunar phase determination operations. The approach therefore provides scope for further research and practical applications, including, but not limited to, mobile applications to facilitate the analysis of photographs of the moon taken by users. Our studies illustrate one way of how such automation can be used when researching the universe and its contents. Although the results are impressive and the best model achieves an accuracy level of 82.74%, challenges remain in terms of accurate daily predictions due to economic, grounding biases and lunar libration and orbital drift. This study aimed to integrate the classical methods of lunar observation into the field of technology and provide a new dimension to the enduring interest of mankind in building structures that help locate the lunar phases.

Future work

Looking ahead, the next step in advance of this project is to record and label lunar images from a wider range of devices, including Digital Single-Lens Reflex (DSLR) cameras, mobile phones, and other commonly accessible go-pro cameras. Collecting images from different geographic locations over time will also be critical. By doing this over the course of a full meteorological cycle (approximately 19 years), we will capture the full range of variations of the Moon under various atmospheric conditions, lighting scenarios, and angles of observation.

This extended dataset would address a significant limitation in our current model, which has been predominantly trained on high-quality NASA images. By introducing data from day-to-day devices, we can introduce variability in image quality, resolution, and noise that will better reflect real-world conditions. A broader, more diverse dataset will allow us to train models that not only perform better but are also more adaptable to different use cases, such as mobile phone-based lunar observation apps, educational tools, or personal stargazing applications.

An approach we can discuss is to train a model on the illumination percentage of the moon as the labels, which we could then use to calculate the lunar day using mathematical formulas that have already been developed. Ultimately, broadening the dataset and incorporating images from everyday cameras will allow for a model that can be generalized better, making it more accessible and useful to the public38.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Encyclopaedia Britannica: lunar calendar. https://www.britannica.com/science/lunar-calendar (2023, accessed 20 Oct 2023).

Encyclopaedia Britannica: astronomy. https://www.britannica.com/science/astronomy (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2023).

Encyclopaedia Britannica: the Early Roman Calendar. https://www.britannica.com/science/calendar/The-early-Roman-calendar (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2023).

U.S. Naval Observatory: Phases of the Moon and Percent of the Moon Illuminated. (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025). https://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/moon_phases.

Priskin, G. The eye of horus and the synodic month. Discuss. Egyptol. 2002, 75–82 (2002).

NASA Science: moon phases. https://science.nasa.gov/moon/moon-phases/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Library of Congress: ancient Greek Astronomy and Cosmology. https://www.loc.gov/collections/finding-our-place-in-the-cosmos-with-carl-sagan/articles-and-essays/modeling-the-cosmos/ancient-greek-astronomy-and-cosmology (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J.: Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. arXiv:1512.03385

Ajuntament de Barcelona: understanding the Islamic Calendar. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/oficina-afers-religiosos/en/blog/islam-understanding-islamic-calendar#:\(\sim\):text=The%20Islamic%20lunar%20year%20has,(yawm%20as%2Dsabt) (2023).

Al-Battani: Kitab al-Zij. Various publishers (1899). A comprehensive astronomical work by Al-Battani, contributing to the refinement of the lunar calendar.

Al-Biruni: Kitab Al-Athār al-Bāqiyah ’an al-Qurūn al-Khāliyah. Various publishers, (1873). Al-Biruni’s work on the history of ancient cultures, including studies on the lunar calendar and lunar phases.

Encyclopaedia Britannica: Scientific Revolution. https://www.britannica.com/science/Scientific-Revolution (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Zou, J., Han, Y. & So, S.-S. Overview of artificial neural networks. In Artificial neural networks: methods and applications 14–22 (2009).

Allawi, Z. T. A pattern-recognizer artificial neural network for the prediction of new crescent visibility in iraq. Appl. Sci. 10(10), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10010186 (2022).

Ahmed, D. Astronomy, moon sighting and hijri calendar. Retrieved from Researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283826321_Astronomy_Moon_Sighting_and_Hijri_Calendar (2006).

Al-Rajab, M., Loucif, S. & Al Risheh, Y. Predicting new crescent moon visibility applying machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 6674 (2023).

Ahmed, T. Predicting the visibility of the first crescent: predicting the visibility of the first crescent. KIET J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 3(2), 10 (2020).

Loucif, S., Al-Rajab, M., Abu Zitar, R. & Rezk, M. Toward a globally lunar calendar: a machine learning-driven approach for crescent moon visibility prediction. J. Big Data 11(1), 114 (2024).

Moshayedi, A. J., Chen, Z.-Y., Liao, L. & Li, S. Sunfa ata zuyan machine learning models for moon phase detection: algorithm, prototype and performance comparison. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control) 20(1), 129–140 (2022).

Fakhar, M., Moalem, P. & Badri, M. A. Lunar crescent detection based on image processing algorithms. Earth Moon Planet. 114(1), 17–34 (2014).

Wahyuni, R., Issaac, G., Rachmaputri, G. & Muchtadi-Alamsyah, I. Modelling of islamic calendar system based on moon phase. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1127, 012069 (2019).

Abuelyamen, S. H. The hijri calendar and its conformance with the gregorian calendar by mathematical calculations. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 9(1), 01–19. https://doi.org/10.20319/mijst.2023.91.0119 (2023).

Sejzei, A. H. & Jamzad, M. Evaluation of various digital image processing techniques for detecting critical crescent moon and introducing cmd-a tool for critical crescent moon detection. Optik 127(3), 1511–1525 (2016).

O’Shea, K. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08458 (2015).

NASA: A Year in the Life of Earth’s CO2: 2019. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/5187/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Selenium: selenium documentation: overview. https://www.selenium.dev/documentation/overview/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

NASA: Scientific Visualization Studio. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Google: Google Dataset Search. https://datasetsearch.research.google.com/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Contributors, O. OpenCV: Open Source Computer Vision Library. https://opencv.org/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Developers, A. Augmentor: image augmentation library. https://augmentor.readthedocs.io/ (2023, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Canny, J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intel. PAMI 8(6), 679–698 (1986).

Sobel, I. An isotropic 3x3 image gradient operator. In Presented at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Project (SAIL) (1968).

Dalal, N. & Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), vol. 1 886–893 (IEEE, 2005).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20(3), 273–297 (1995).

Schwartz, R., et al. Compute and energy consumption trends in deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.05472 (2021).

Jung, A. Components of machine learning: binding bits and flops. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.12387 (2019).

Sovrasov, V. Flops Counter for Convolutional Networks in PyTorch Framework. https://github.com/sovrasov/flops-counter.pytorch/ (2019, accessed 12 Nov 2019).

Lipton, Z. C. A critical review of recurrent neural networks for sequence learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.00019 (2017, accessed 20 Jan 2025).

Funding

No external funding acquired for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Formal analysis, Z. N. and F.S.; software, Z. N. and F.S.; original draft preparation, Z. N., F.S., A.A.M. and J.R.; conceptualization and methodology, Z. N., F.S. and A.A.M.; reviewing and editing, J.R. and R.A. supervision, R.A.?All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nissar, Z., Sheikh, F., Marouf, A.A. et al. Automated lunar age detection through determining the day of the synodic month using convolutional neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 35973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18165-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18165-w