Abstract

Opiliones (Arachnida) comprises approximately 7,000 species. Due to their lack of venom glands, their defense is mainly based on the secretion of scent glands, which also play roles in communication and antimicrobial activity. This odoriferous secretion has a diverse composition according to harvestmen species but frequently contains benzoquinones. Studies of benzoquinone synthesis intermediates suggest a pathway based on lipid metabolism from diet. This study provides the first transcriptomic and enzymatic analysis of the midgut of Mischonyx squalidus to understand the acquisition of nutrients. The enzymatic analysis tested 11 digestive enzymes and found high lipase activity and moderate and low activity for peptidases and carbohydrases, respectively. Transcriptome sequencing yielded 19,658 unigenes, predominating enzymes and binding proteins closely associated with Xiphosura and Scorpiones proteins; a third of which are hydrolases. A multigene lipase family is expressed. Cathepsin L peptidases were prominently abundant, indicating their relevance for protein digestion. Additionally, toxin-like proteins and lipid metabolism-related enzymes, such as phospholipase A2 and NPC cholesterol transporters, were represented, indicating a sophisticated digestive and metabolic system for lipids. These findings suggest a link between lipid digestive metabolism and defensive and communicative molecule synthesis, underscoring Opiliones’ unique evolutionary adaptations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Opiliones is one of the largest orders in Arachnida, containing approximately 7,000 species distributed worldwide1. The group is omnivorous, with a preference for animal matter, and is the only group of arachnids that does not perform extra-oral digestion but bites off small pieces to ingest solid tissues2. Due to their lack of venom glands, Opiliones have not been mainly explored as a source of new enzymes and toxins even though the scent secretion produced by this Arachnida group has been the focus of studies regarding the production of benzoquinones and other organic compounds as antibiotics, such as gonyleptidine, a 2,5-dimetil-1,4-benzoquinone identified in Acanthopachylus aculeatus2.

Biologically, the scent gland (SG) or repugnatorial glands are exocrine structures mainly involved in the Opiliones’ defense from microorganisms and predators and communication with conspecifics. The chemistry of the scent gland has been detailed for about 2% Opiliones species since the discovery of Ernest Hofer of the European harvestmen Phalangium opilio quinones3,4,5,6,7. The major chemical classes of secretion components are phenols, benzoquinones, ketones, and alkaloids8. The nature of some of those molecules indicates that their synthesis starts with molecules derived from lipid metabolism, such as acetate and propionate identified in Iporangaia pustulosa9 and Mischonyx squalidus10 which are produced via the malonyl-CoA pathway. These data suggest that fatty acids and/or acetyl-CoA from food catabolism would be essential to odour molecule synthesis.

Information regarding nutrient acquisition and digestive physiology are scarce in Opiliones, although the midgut is the largest organ in harvestmen. The foregut and hindgut, as usually in other arthropods, are cuticular lining tissues due to their ectodermic origins, while the midgut is a secretory epithelium due to its endodermic origin11. Similarly to other Arachnida species, the harvestmen midgut is divided into ventriculus and diverticula, and the monolayer digestive epithelium is composed mainly of secretory and digestive cells. However, harvestmen have a specific kind of cell, the resorptive cells, with vesicles containing material for the peritrophic membranes12. Although the morphology of the midgut is quite well known, the molecular physiology of harvestmen digestion is still unexplored.

Combined studies of enzymology and transcriptomic sequencing of Arachnida midgut samples have shed light on the molecular aspects of digestion in scorpions13 spiders14,15 ticks16 and mites17 allowing comparative and evolutive studies among predators with preoral digestion and hematophagous Arachnida, but data on saprophytic arachnids are missing. M. squalidus (former M. cuspidatus18 is an omnivorous animal with saprophytic habits19. Several aspects of the biology of M. squalidus have been extensively studied, including the chemical composition of the scent glands’ secretion, defensive behavior20,21,22odour sensitivity23 and synanthropic behavior24.

In order to amplify the knowledge on Opiliones digestion and understand the possible communication between the digestive system as a source of lipids to the synthesis of odour molecules in this work, we have performed the first transcriptomic and carbohydrases, peptidases, and lipase activity analysis of the midgut of harvestmen, using M. squalidus as our studied model to understand the molecular aspects of digestion in Opiliones.

Results

Specific activities of digestive enzymes

Enzyme activities of lipases (561 ± 71 mU/mg), chitinase (0.2 ± 0.05 mU/mg), hexosaminidase (0.2 ± 0.08 mU/mg), alpha-L-fucosidase (0.41 ± 0.07 mU/mg), alpha-D-mannosidase (0.37 ± 0.1 mU/mg), cysteine peptidase (cathepsin L) (2.44 ± 1.4 mU/mg), aminopeptidase (6.77 ± 4.5 mU/mg) and carboxypeptidase (0.35 ± 0.08 mU/mg) were quantified in the midgut samples of M. squalidus (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Serino-peptidases (trypsin), metallopeptidases and α-amylase activities were indetectable.

Specific activities (mU/mg) of digestive enzymes measured at the soluble fraction of midgut samples from M. squalidus. Enzyme assays were performed, as shown in Table 6. N = 8 to each enzyme, except for carboxypeptidase (1 C) N = 7. The error bars are SEM.

Transcriptome assembly and gene ontology

The transcriptome of M. squalidus was assembled using trimmed reads from midgut samples, totalling 15,146,657 paired-end reads. De novo assembly resulted in 71,463 contigs. The translation of transcripts, considering only sequences with a predicted domain, yielded 25,462 protein sequences. The final transcript set, obtained after isoform removal, comprised 19,658 unigenes with BUSCO completeness scores of 64.5% for the Arachnida dataset and 77.3% for the Eukaryota dataset. The depth of the libraries for this assembly was between 13.8 and 26.7 (Supplementary Table 1).

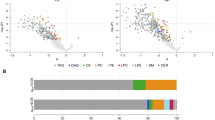

Protein sequence annotation with Blastp analysis against the Invertebrate NCBI database resulted in a total of 16,957 sequences (86%) with Blast hits. The remaining 14% of sequences that did not show any identity with other annotated proteins at this stage were not investigated further. Most of the hits had as best hits sequences from Limulus polyphemus (2,945 sequences), followed by Centruroides vittatus (2,005 sequences), and Centruroides sculpturatus (1,390 sequences). Gene Ontology (GO) mapping has revealed that the predominant biological processes involve metabolic processes (2392 genes) and cellular processes (3186 genes), biological regulation (993 genes), and cellular component organisation or biogenesis (913 genes). The predominant molecular functions are catalytic activity (2368 genes) and binding (3535 genes) (Fig. 2).

The top thirty unigenes with higher TPM values (ranging from 2,159.51 to 11,326.92) from M. squalidus midgut are mainly housekeeping genes and metabolic demands proteins (Supplementary Table 2). The only genes directly related to digestion are two peptidases annotated as putative cathepsins L (the top two most expressed transcripts in Table 2), indicating some relevance to digestive enzymes. Other highly expressed genes are from oxidative stress response elements (e.g., Glutathione S-Transferase; soma ferritin-like), which might be indirectly associated with food intake.

Functional annotation and classification based on EC numbers of the enzymes revealed a set of 2434 sequences annotated across the seven EC classes (Fig. 3A), with the majority corresponding to hydrolases and transferases. Focusing on hydrolases (EC 3.-), which mainly represent the enzymes involved in digestion, the classification by subclass revealed significant functional diversity. Among the 824 hydrolase sequences, 334 were classified as acting on acid anhydrides (EC 3.6.-), while 159 as acting on peptide bonds (peptidases) (EC 3.4.-), 152 as acting on ester bonds (EC 3.1.-), 123 as general hydrolases (EC 3.-.-), 39 as glycosylases (EC 3.2.-) and 27 as acting on carbon-nitrogen bonds, other than peptide bonds (EC 3.5.-). Other hydrolases EC were annotated for 10 unigenes (Fig. 3B).

The most abundant genes in the midgut (TPM > 50) that are effectively associated with digestion (Table 2) provide a clear view of this arachnid’s digestive adaptations. The cysteine peptidase group comprises five annotated genes for cathepsin L, two of which have TPM values higher than 4000; one for cathepsin B, one for cathepsin O, and one for legumain. Among the other endopeptidases are nine serine endopeptidases: three trypsin-like isoforms (sum of TPM = 3540), two chymotrypsin-like (sum of TPM = 161,77), and two prolyl endopeptidases (sum of TPM = 185,73). Four metallopeptidases from the astacin family were identified (sum of TPM = 362). Exopeptidases totalize 20 distinct contigs with a sum of TPM of 4042, being the three most abundant expressed transcripts annotated as dipeptidyl-peptidase, carboxypeptidase B and aminopeptidase (Table 3).

Enzymes hydrolysing ester bonds, which include lipases and phospholipases, are the third hydrolase class with a higher number of transcripts assembled at the midgut transcriptome of M. squalidus (Fig. 3). When comparing the expression values, the pancreatic triacylglycerol lipases are the most highly expressed genes (with four transcripts totalling 586.1 TPMs) among this class, although gastric triacylglycerol lipases and monoglyceride lipases are also present (Table 4), as well as other 13 related transcripts. Blastp analysis of lipase evidenced best hits with spider lipases. Lipase sequence molecular modelling (Fig. 4) of human lipase opened conformation, closed horse lipase (Fig. 4A), M. squalidus lipase (Fig. 4B), insect lipase (Fig. 4C) and, spider lipase (Fig. 4D) evidenced the conservation of the catalytic triad (Ser, His Asp), the absence of a lid at M. squalidus and insect lipase structure suggesting an opened conformation25the presence and distinct structure organisation at the surroundings of the active site at spider lipase (Fig. 4D).

Molecular modelling of distinct lipases. The catalytic residues are in red in all lipase structures. (A) Human pancreatic lipase in open conformation (PDB 1LPA, in green) and horse pancreatic lipase in close conformation (PDB 1HPL, in grey). In dark blue, the lid of LPA and in orange the lid of HPL, in wheat the colipase structure bound to LPA. (B) LPA and M. squalidus lipase DN4626_c0_g1_i1.p1 (this work in cyan), (C) LPA and Spodoptera frugiperda (GenBank accession number XP_050561712.1PTL in brown) and, (D) M. squalidus lipase in cyan and spider Nephilingis cruentata lipase (SRR3943479) in magenta.

Besides the classic lipases involved in digestion, two phospholipases, patatin-like and phospholipase A2, were also identified with TPM values ranging from 50 to 120. Alpha-L-fucosidase-like (TPM = 1120), is the most expressed glycosidase transcript, followed by sucrase-isomaltase (TPM = 376.48) and alpha-mannosidase (TPM = 374.90), which were moderately expressed. Two chitinase-3-like (TPM = 271.87 and 238.92) and a beta-hexosaminidase (TPM = 207) indicate a moderate expression for the chitin-degrading enzymes complex. A unigene annotated for pancreatic alpha-amylase (TPM = 93.68) was also found (Table 5).

Analysis of digestive physiology-related and toxin-like proteins

Besides transcripts coding for digestive enzymes, some other essential transcripts were highly expressed in the midgut from M. squalidus (Supplementary Table 3). The most variable and expressed ones are peptidase inhibitors such as four-domain peptidase inhibitors (six unigenes, TPM sum = 3,061) and intracellular coagulation inhibitor 1 & 2 (three unigenes, TPM sum = 869). Another protein related to the digestive process in Arthropoda is peritrophin-like, identified by its domain CBM_14, with its highest unigene presenting TPM value of 2,071 at M. squalidus midgut transcriptome.

Although harvestmen do not present a venom gland nor venomous secretions, some toxin-like proteins, typical of other arthropods’ venoms, are present as transcripts at the midgut of this harvestmen species, such as U-24 ctenitoxin (average identity of 45%, e-value 6 × 10− 37, scoloptoxin (identity = 48,97%, e-value = 0), and dermo necrotic toxin (identity = 45,79%, e-value = 2 × 10− 96) and phospholipase A2 (identity = 42,92%, e-value = 4 × 10− 64), usually associated to Hymenoptera venoms26.

Transferases and translocases are groups of enzymes that are also highly expressed in M. squalidus midgut. Among transferases, glutathione S-transferases had 35 isoforms (TPM > 50) and high TPM values (Supplementary Table 3). Among translocases, V-type proton ATPase and sodium/potassium transporting ATPase were the most common and expressed genes.

NPC intracellular cholesterol transporters, which are likely involved in lipid metabolism, particularly in the intracellular transport and regulation of cholesterol export from lysosomes27were also highly represented (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

Digestive physiology in M. squalidus based on biochemical and transcriptomic analysis

In this work, the midgut of a harvestmen species was molecularly characterised for the first time through enzyme assays and RNA sequencing analyses. The enzymological analysis revealed high lipase activity, mainly acidic endopeptidase activities and a high activity of some exopeptidase, and lysosomal-like carbohydrases as the most active enzymes. The biochemical data agree with the transcriptomic data. The prevalence of hydrolases acting on acid anhydrides (EC 3.6.-) among the hydrolases (Fig. 3B) suggests that the majority of hydrolase genes in the midgut are essential for processes of translation (e.g. Elongation Factor 1-alpha) and stress response (e.g. heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha-like) suggesting high protein synthesis in this tissue (Supplementary Table 2). The subsequent high percentage of hydrolases functioning as peptidases, glycosylases, and hydrolases acting on ester bonds indicates enzymes that play a role in digestion and nutrient acquisition, breaking down peptides, carbohydrates, and lipids, respectively.

Sequence annotation of enzymes involved in carbohydrate processing highlights the presence of transcripts for chitinase, fucosidase, mannosidase, and hexosaminidase, which were usually identified as digestive enzymes in previous Arachnida digestion analyses13,14,15. Among these carbohydrases, an alpha-L-fucosidase (Table 5) is the most abundant carbohydrase transcript in the digestive tissue, followed by an alpha-mannosidase-like transcript. Experiments of cell fractionation and proteomic analysis of the midgut diverticula from the spider Nephilingis cruentata evidenced that fucosidase, mannosidase and a series of carbohydrases involved in monomers removing are lysosomal enzymes involved in the intracellular phase of digestion. Similar results were obtained in the proteomic analysis of the digestive fluid and abdomen from Acanthoscurria geniculata28suggesting that fucosidase and mannosidase are lysosomal enzymes. M. squalidus is the first Arachnida species that has higher expression and activity of typical lysosome-like carbohydrases as the main enzymes processing carbohydrates instead of chitinases. Thus, comparing data obtained from M. squalidus with those from spiders’ digestive enzymes suggests that Opiliones have a more relevant carbohydrate degradation during intracellular digestion than extracellular digestion. Only a single transcript with a very low TPM value was identified in the transcriptome as pancreatic alpha-amylase, which is coherent with the absence of activities at the enzymatic assays. This enzyme’s low expression and activity might suggest that starch/glycogen digestion is not a metabolic priority for M. squalidus, likely due to its saprophytic feeding habit or specific ecological niche. However, these animals had sucrase-isomaltase (TPM = 376.48) and maltase-glucoamylase (TPM = 94.98), which might catalyse the hydrolysis of glucose oligomers shorter than starch or glycogen. This hypothesis is coherent with the harvestmen saprophytic feeding habit. Complex carbohydrates like starch might have already been partially digested and ingested as oligosaccharides, suggesting adaptations for digesting partially degraded carbohydrates. However, this distribution of carbohydrases is distinct from the pattern presented by spiders, scorpions, and even mites and ticks, where transcripts coding depolymerases such as chitinases and amylases are the most abundant transcripts and amylase and chitinase activities are higher in comparison to lysosomal-like carbohydrases, such as fucosidase and mannosidase14.

Distinctly from carbohydrases, peptidase activities from M. squalidus are similar to those peptidases identified in ticks, scorpions and spiders midgut: acidic peptidases, mainly cathepsin L-like cysteine peptidases of multiple isoforms. M. squalidus has 10 annotated cathepsin L unigenes, four of which are highly expressed with a TPM of 4,698.18 coding pro cathepsin L-like. Other RNA sequence coding cysteine peptidases and also highly expressed codes legumain and cathepsins B and O. Although the level of expression of cathepsin L is similar to other Arachnida species, the activity measured to M. squalidus is significantly lower compared to species, such as Uloborus sp.15 and T. serrulatus13 (Fig. 5). Some possible hypotheses for that are an insufficient cathepsin L zymogen activation; high degree of autolysis or inhibition by an excess of substrate in a complex midgut homogenate sample. Another possibility is the inhibition by the cathepsin propeptide inhibitor domain (I29), also identified at the M. squalidus cathepsin L sequences in the transcriptome, which can be a competitive inhibitor with the substrate even after enzyme activation (Table 1).

Specific activity comparison between lipase and cathepsin L activities of M. squalidus and other Arachnida. The specific activities of lipase (5 A) for M. squalidus (561 ± 71 mU/mg), Uloborus sp15. (9.3 ± 1.8 mU/mg), and Amblyomma cajennense57 (6 ± 3 mU/mg) and specific activities of cysteine peptidase (5B) (cathepsin L) for M. squalidus (2.44 ± 1.4 mU/mg), Uloborus sp15. (21,400 ± 6,700 mU/mg), and Tityus serrulatus13 (15,000 ± 5,000 mU/mg).

Regardless of this, transcriptomic and biochemical data indicated that cathepsin L is the most active and expressed endopeptidase, suggesting that protein digestion predominantly occurs via cysteine peptidases in this animal. This is a common adaptive feature among predatory arachnids such as the scorpion T. serrulatus13 and mite hematophagous species28. mRNA coding serine peptidases and metallopeptidases were also identified in the transcriptomic analysis (Table 2); however, the enzyme activity was undetectable. As previously reported13,14,16the levels of these classes of endopeptidases are also less significant to protein digestion in scorpions, mites, and ticks. On the other hand, spiders present high levels of mRNA coding metallopeptidase and a variety of genes coding distinct isoforms of astacins. Metallopeptidase activity measure could be associated with envenomation and web recycling15. As we have demonstrated for carbohydrate digestion in M. squalidus, the hypothesis that nutrients ingested by harvestmen are already, at least partially, in decomposition is also corroborated by the analysis of peptidases with high activity of enzymes hydrolysing preferentially short oligomers substrates such as carboxypeptidases and aminopeptidases and also the of abundance and diversity of mRNA coding exopeptidases (Table 3).

Finally, efficiency in lipid metabolism is the M. squalidus most remarkable characteristic, as revealed by enzymatic analyses. In agreement, the lipase-related transcripts were abundant in the RNA-seq analysis (Table 4), with pancreatic triacylglycerol lipase-like being the most expressed lipase gene. The predominance of lipases is a striking distinction, making the enzymatic profile of this arachnid unique and suggesting a greater reliance on lipids as an energy source or structural component in its diet. Although not among the most abundant transcripts in the transcriptome, high catalytic efficiency and/or the cumulative activity of several isoforms could explain the elevated value of lipase enzymatic activity observed. Mammalian lipases have two distinct structural forms: the closed one, where the lid covers the active site, and the open one where a colipase binds to lipase β barrel and also to the lid in the presence of substrate. Insects´ lipases do not have the lid and are permanently in their open form29which suggests an adaptation to the absence of a colipase since this protein is not present in Insects. However, Arachnida lipases alignment sequences, other than Opiliones, suggest the presence of a lid covering the active site (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, modelling results suggested that the alpha-helix structure of the mammalian lid was replaced by a shorter loop at M. squalidus digestive lipase and a long alpha-helix at spider lipases. This might be related to the differences observed in lipase velocities among M. squalidus and other Arachnida lipases and suggests possible differences of substrate specificities of these enzymes. Apparently, till now the sequence data banks do not suggest a colipase-like protein for this group. Thus, structural studies of Arachnida lipases are paramount in understanding their mechanism of regulation, specificity and catalysis.

Opiliones and its digestive enzymes in arachnid phylogeny

The phylogenetic position of the Opiliones within the arachnids and even Arachnida as a monophyletic group remains a subject of debate30. A study that combined cladistic and molecular analyses, focusing on the 18 S rRNA gene and the D3 region of the 28 S rRNA gene, suggests that Opiliones belong to the Dromopoda clade, along with other arachnids such as scorpions and solifugae31. A more recent study utilizing a substantial dataset comprising up to 3,644 loci has proposed an alternative clade comprising Opiliones, Ricinulei, and Solifugae32. However, knowledge regarding the digestive physiology and transcriptomics of species from these groups is still unexplored. The increase in molecular data of this group can help in new phylogeny studies to support new phylogenies. Our data Xiphosura, Scorpiones, and Araneae sequence identities among Euchelicerata already based on Blastp results of M. squalidus midgut transcriptome reveal a prevalence of sequenced and available at public databank (Supplementary Fig. 2). The most frequent species matches found in the unigenes’ best hits of M. squalidus midgut are with the Xiphosura species, Limulus polyphemus (2,945), underscoring the molecular similarities between M. squalidus and basal arachnids/Chelicerata, essentially in-housekeeping genes, but also for critical digestive enzymes (e.g. alpha-L-fucosidase-like isoform x1 - TPM 1120.54). The following main matches are with two Scorpiones, Centruroides vittatus (2,005) and Centruroides sculpturatus (1,390). These occurrences agree with the phylogeny proposed by Giribet et al., 2001. The increase in data on digestive enzymes and/or other tissue transcriptome might help in future phylogenetic analysis of Opiliones.

Genes involved in inhibitory, defense mechanisms, and toxin-like functionalities present at opiliones midgut

Midgut transcriptomic analyses of non-venomous spiders and other non-venomous Arachnida species have shown that some genes usually translated as proteins found at the venom gland, such as some metallopeptidases13,14,15peptidase inhibitors33phospholipase A213,14, and toxins15 are present at the digestive system and mainly at the midgut. These data had also been confirmed by proteomic midgut analysis of different Arachnida species suggesting a common ancestor between digestive and venom enzymes with a specialization of the last ones to gain distinct catalytic function and specificities14,34.

This is also true for Opiliones. Transcripts encoding toxin-like proteins, such as U-24 ctenitoxin, scoloptoxin, dermo necrotic toxin, and phospholipase A2 were detected. Although M. squalidus lacks venom glands, these proteins may have non-venomous roles, such as predigestion or defense, for this harvestmen species. Furthermore, the significant presence of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), with multiple isoforms highly expressed, highlights their potential involvement in detoxification pathways and protection against oxidative stress35possibly to neutralize ingested toxins or other products of its saprophytic digestion.

Four-domain peptidase inhibitors (FDPI) and leukocyte elastase inhibitors (LEI) were the most expressed peptidase inhibitors in M. squalidus and showed significant transcription levels (Supplementary Table 3). These inhibitors likely play critical roles in protecting midgut tissues from enzymatic damage caused by peptidases, thus maintaining the structural integrity of the digestive system. However, some common serine peptidase inhibitors identified in spiders are not identified in M. squalidus suggesting distinct adaptations to prey peptidases ingested during feeding.

Additionally, the identification of peritrophin-like proteins suggests the formation of a peritrophic membrane. Peritrophic membranes in insects usually provide a barrier against pathogens and digestion compartmentalisation36,37. However, to harvestmen, indigestible particles and cellular excretes are first enveloped by peritrophic membranes in the anterior part of the midgut and then pass into the posterior section where they are wrapped in a peritrophic envelope consisting of many peritrophic membranes and pressed together to form a sizeable faecal pellet11. This compartmentalization of the faecal pellet by the peritrophic membrane is similar to that already described in ticks. Mites and ticks present a peritrophic membrane as an uneven single layer with a variable thickness between larvae, nymphs, and adult females, covering the whole surface of the midgut epithelium. After food repletion, the peritrophic membrane becomes thicker and thicker, winding and multi-layered.

The NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter genes, also highly expressed, point to active lipid metabolism, specifically in cholesterol regulation, transport, and efflux of cholesterol. This suggests that M. squalidus may rely on efficient cholesterol transport mechanisms to support its metabolic processes, possibly reflecting adaptations to specific dietary and ecological requirements, such as the transport of lipids.

As previously mentioned, harvestmen produce and secrete volatile compounds, mainly quinone derivatives. The characterisation of their intermediate products suggests acetate, propionate, and malonyl-CoA as synthesis precursors derived from fat acids and use the fatty acid synthesis pathway associated with polyketide synthase. The association of the dependence of fat acid-derived products to odour synthesis at the scent glands and our data that M. squalidus present high lipase activities suggests the connection between digestion and the scent gland products.

The corroboration of this hypothesis would be possible by analysing the expressed genes and protein production at the scent gland of harvestmen species to identify the molecules involved in each step of odoriferous molecule synthesis.

Methodology

Sample collection and maintenance

Specimens of M. squalidus used in this project (SISBIO authorization for sampling 87645-1 / CEUA ethics declaration 4715300123) were collected during two field expeditions, the first in March 2023 and the second in January 2024, at the Rio dos Pilões Private Natural Heritage Reserve (RPPN), located in the municipality of Santa Isabel, São Paulo, Brazil. Species identification was confirmed by Dr. Ricardo Pinto-da-Rocha, from the Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo.

The collected adult female and male harvestmen were transported to the Laboratory of Biochemistry at the Instituto Butantan, where they were dissected to obtain sections of the midgut (MG), scent glands (SG), and carcass. Tissue dissection was performed under a stereomicroscope, using scissors and tweezers, and after immobilization of the specimens on ice for approximately 5 min. To dissect the tissues, the carapace was peeled back from the posterior to the anterior margin. The SGs were located internally, attached to the ozopores (Supplementary Fig. 3-A), while the MG was accessed through the ventral part of the animal’s carcass (Supplementary Fig. 3-B). The dissected sections were separately stored in microtubes and kept at -80 °C until further use for homogenate preparation or genetic material extraction. Specimens not immediately dissected were housed in acrylic boxes with water and fed ad libitum on a diet of crickets.

Enzymatic activity analyses

Sample preparation and assay conditions

The MG of a single adult harvestman (male or female) was prepared in 500 µL of ultrapure water for the enzymatic activity assays. MG tissues were macerated using a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 30 min. The soluble fraction obtained from this step was used for total protein quantification and enzymatic assays. In total, 8 distinct homogenate samples were analysed. This study has measured 11 distinct enzymes, categorised into three primary classes: carbohydrases (α-amylase, hexosaminidase, α-L-fucosidase, α-mannosidase, and chitinase), peptidases (serine peptidase, cysteine peptidase, aminopeptidase, carboxypeptidase, and metallopeptidase) and, lipases (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The total protein content in the homogenates was estimated using the BCA method (bicinchoninic acid) with absorbance readings at 562 nm38. This value was determined by comparing the slopes of standard curves prepared with diluted egg albumin (10x) and MG homogenates.

Enzymatic reactions were conducted using specific substrates and assay conditions (Table 6). All enzymatic assays were performed at 30 °C under pH and molarity conditions previously tested for the spider Uloborus sp15. The Cathepsin L enzyme assay involved a 30 min pre-incubation period at 30º in pH 3.5 of the homogenate to activate the zymogen before the addition of the substrate.

Enzyme assays employed substrates with chromogenic or fluorescent properties, whose concentrations were measured over time. Standard curves for each detectable product were generated. MG homogenates from eight individuals (five males and three females) were individually analyzed for total protein quantity estimation and enzymes activity detection. Specific activities were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean.

Calculation of enzymatic activities (U)

-

Data collected over time for each sample and enzyme assay were plotted, and a line of best fit was determined. The slope of this line represented the rate of product formation and was divided by the slope of the standard curve to calculate enzymatic activity (U) in nmol/min.

-

The obtained value was corrected for dilution by multiplying it by the dilution factor (2x, 5x, 10x, or 20x).

-

Absolute activity (mU) was calculated by extrapolating Ucorrected to 1 mL of enzyme used per assay:

-

Specific activity (mU/mg) was obtained by dividing the absolute activity by the total protein concentration in the homogenate:

Midgut transcriptomic analysis

Total RNA was individually extracted from the midgut (MG) of three adult females of M. squalidus. Tissue samples were preserved at − 80 °C until processing. Three RNA extractions were performed using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, tissues were homogenized in 500 µL of TRIzol using a plastic pestle. After homogenization, RNA was isolated following the reagent’s standard protocol and resuspended in 20 µL of DEPC water. The quality of the three extracted RNA was evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to assess purity, and quantitative analyses were performed by Qubit, with an RNA HS Assay kit. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded RNA Core Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions and 2 × 100 bp reads sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform.

The raw reads quality was assessed using FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Low-quality bases (Phred score < 30) and adapter sequences were removed using Trimmomatic39 with the parameters CROP:98, HEADCROP:13, TRAILING:30, LEADING:30, SLIDINGWINDOW:5:30, and ILLUMINACLIP. Ribosomal RNA contaminants were removed using BBDuk (BBTools package) using reference sequences from the ribokmers.fa.gz file.

A de novo assembly was performed using Trinity v2.15.140 with default parameters. Protein-coding sequences were predicted using TransDecoder.LongOrfs and TransDecoder.Predict (http://transdecoder.sf.net), validated with HMMER341 against PFAM database42 for domain recognition. Only the longest isoforms obtained with the Trinity script get_longest_isoform_seq_per_trinity_gene.pl were retained in the final transcript set from the protein predicted transcript set. he completeness of the transcriptome assembly was evaluated with BUSCO v543 using the Arthropoda and Eukaryota single-copy ortholog databases.

Functional annotation of the assembled transcripts was performed using OmicsBox v3.3.2 (BioBam)44. Transcripts were compared to the RefSeq invertebrate protein database (ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/release/invertebrate/ - September/2024) using BLASTp with an e-value threshold of 1E-3. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned to transcripts, and protein domains were identified using InterProScan45. The online tool WEGO (Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot)46 was used to generate the summarized GO annotation plot from the data exported from OmicsBox. All annotation results, in table format, were integrated and analyzed using Blast2GO. Pie charts were assembled with GraphPad Prism software version 8.2.1.

Gene expression levels were quantified using RSEM47with alignment performed using Bowtie248. Expression values were normalized and reported as TPM (Transcripts Per Million)and the mean between the three samples was calculated and used as the TPM value. The depth of the libraries was measured using the transcript.bam data generated by RSEM, using the samtools49. To analyse the digestive enzyme annotations, only those unigenes with a TPM value greater than 50 were used.

Data availability

The raw RNA-seq sequence data from the three *M. squalidus* midgut samples will be available in the Short Read Archive (SRA) GenBank database https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank: BioProject (PRJNA1197991), BioSample (SAMN45817013).

References

Kury, A. B., Mendes, A. C., Cardoso, L., Kury, M. S. & Granado, A. D. A. WCO-Lite: online world catalogue of harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones): Version 1.0—checklist of all valid nomina in Opiliones with authors and dates of publication up to 2018. (2020).

Cohen, A. C. Extra-oral digestion in predaceous terrestrial arthropoda. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 40 (1), 85–103 (1995).

Eisner, T., Rossini, C., González, A. & Eisner, M. Chemical defence of an opilionid (Acanthopachylus aculeatus). J. Exp. Biol. 207 (8), 1313–1321 (2004).

Höfer, E. Über Das Sekret der sogenannten Stinkdrüsen der opilionen. Archiv Für Die Gesamte Physiologie Des. Menschen Und Der Tiere. 118 (9), 599–630 (1907).

Raspotnig, G., Fauler, G., Leis, M. & Leis, H. J. Chemical profiles of scent gland secretions in the cyphophthalmid opilionid harvestmen, Siro duricorius and S. exilis. J. Chem. Ecol. 31, 1353–1368 (2005).

Raspotnig, G., Schaider, M., Stabentheiner, E., Leis, H. J. & Karaman, I. On the enigmatic scent glands of dyspnoan harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones): first evidence for the production of volatile secretions. Chemoecology 24, 43–55 (2014).

Vieira, M. L. S. et al. Chemical and evolutionary analysis of the scent gland secretions of two species of gonyleptes kirby, 1819 (Arachnida: opiliones: Laniatores). Chemoecology 33 (1), 1–15 (2023).

Raspotnig, G. et al. Chemosystematics in the opiliones (Arachnida): a comment on the evolutionary history of alkylphenols and benzoquinones in the scent gland secretions of L aniatores. Cladistics 31 (2), 202–209 (2015).

Rocha, D. F., Wouters, F. C., Machado, G. & Marsaioli, A. J. First biosynthetic pathway of 1-hepten-3-one in Iporangaia pustulosa (Opiliones). Sci. Rep. 3 (1), 3156 (2013).

Rocha, D. F. et al. Harvestmen phenols and benzoquinones: characterisation and biosynthetic pathway. Molecules 18 (9), 11429–11451 (2013).

Pinto-da-Rocha, R., Machado, G. & Giribet, G. (eds) Harvestmen: the Biology of Opiliones (Harvard University Press, 2007).

Becker, A. & Peters, W. The ultrastructure of the midgut and the formation of peritrophic membranes in a harvestmen, phalangium Opilio (Chelicerata Phalangida). Zoomorphology 105 (5), 326–332 (1985).

Fuzita, F. J. et al. Biochemical, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of digestion in the Scorpion tityus serrulatus: insights into function and evolution of digestion in an ancient arthropod. PloS One, 10(4), e0123841. (2015).

Fuzita, F. J., Pinkse, M. W., Patane, J. S., Verhaert, P. D. & Lopes, A. R. High throughput techniques to reveal the molecular physiology and evolution of digestion in spiders. BMC Genom. 17, 1–19 (2016).

Valladão, R., Neto, O. B. S., de Oliveira Gonzaga, M., Pimenta, D. C. & Lopes, A. R. Digestive enzymes and Sphingomyelinase D in spiders without venom (Uloboridae). Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 2661 (2023).

Moreti, R., Perrella, N. N. & Lopes, A. R. Carbohydrate digestion in ticks and a digestive α-l-fucosidase. J. Insect. Physiol. 59 (10), 1069–1075 (2013).

Erban, T. & Hubert, J. Digestive physiology of synanthropic mites (Acari: Acaridida). SOAJ Entomol. Stud. 1, 1–37 (2012).

Gueratto, C., Benedetti, A. & Pinto-da-Rocha, R. Phylogenetic relationships of the genus Mischonyx bertkau, 1880, with taxonomic changes and three new species description (Opiliones: Gonyleptidae). PeerJ, 9, e11682. (2021).

Pereira, W., Elpino-Campos, A., Del-Claro, K. & Machado, G. Behavioral repertory of the Neotropical harvestman Ilhaia cuspidata (Opiliones, Gonyleptidae). J. Arachnology. 32 (1), 22–30 (2004).

Dias, B. C. & Willemart, R. H. The effectiveness of post-contact defences in a prey with no pre-contact detection. Zoology 116 (3), 168–174 (2013).

Dias, B. C., da Silva Souza, E., Hara, M. R. & Willemart, R. H. Intense leg tapping behavior by the harvestmen Mischonyx cuspidatus (Gonyleptidae): an undescribed defensive behavior in opiliones?? J. Arachnology. 42 (1), 123–125 (2014).

Willemart, R. H. & Pellegatti-Franco, F. The spider Enoploctenus Cyclothorax (Araneae, Ctenidae) avoids preying on the harvestmen Mischonyx cuspidatus (Opiliones, Gonyleptidae). J. Arachnology. 34 (3), 649–652 (2006).

Dias, J. M. O uso do olfato nos opiliões Neosadocus maximus e Mischonyx cuspidatus (Arachnida: Opiliones: Laniatores) (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo). (2017).

Mestre, L. A. M. & Pinto-da-Rocha, R. Population dynamics of an isolated population of the harvestmen Ilhaia cuspidata (Opiliones, Gonyleptidae), in araucaria forest (Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil). J. Arachnology. 32 (2), 208–220 (2004).

Roussel, A. et al. Crystal structure of human gastric lipase and model of lysosomal acid lipase, two lipolytic enzymes of medical interest. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (24), 16995–17002 (1999).

Guimarães, D. O. et al. Transcriptomic and biochemical analysis from the venom gland of the Neotropical ant odontomachus chelifer. Toxicon 223, 107006 (2023).

Pfeffer, S. R. NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1)-mediated cholesterol export from lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 294 (5), 1706–1709 (2019).

Clara, R. O. et al. Boophilus Microplus cathepsin L-like (BmCL1) cysteine protease: specificity study using a peptide phage display library. Vet. Parasitol. 181 (2–4), 291–300 (2011).

Han, W. K., Zhang, H. H., Tang, F. X. & Liu, Z. W. Characterization of lipases revealed tissue-specific triacylglycerol hydrolytic activity in spodoptera Frugiperda. Insect Science (2024).

Ballesteros, J. A. et al. Comprehensive species sampling and sophisticated algorithmic approaches refute the monophyly of arachnida. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39 (2), msac021 (2022).

Giribet, G., Edgecombe, G. D., Wheeler, W. C. & Babbitt, C. Phylogeny and systematic position of opiliones: A combined analysis of chelicerate relationships using morphological and molecular data 1. Cladistics 18 (1), 5–70 (2002).

Sharma, P. P. et al. Phylogenomic interrogation of arachnida reveals systemic conflicts in phylogenetic signal. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31 (11), 2963–2984 (2014).

Neto, O. B. S. et al. Spiders’ digestive system as a source of trypsin inhibitors: functional activity of a member of atracotoxin structural family. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 2389 (2023).

Walter, A. et al. Characterisation of protein families in spider digestive fluids and their role in extra-oral digestion. BMC Genom. 18, 1–13 (2017).

Ranson, H. & Hemingway, J. Mosquito glutathione transferases. Methods Enzymol. 401, 226–241 (2005).

Dias, R. O. et al. Domain structure and expression along the midgut and carcass of peritrophins and cuticle proteins analogous to peritrophins in insects with and without peritrophic membrane. J. Insect. Physiol. 114, 1–9 (2019).

Terra, W. R., Ferreira, C. & Silva, C. P. Molecular Physiology and Evolution of Insect Digestive Systems (Springer International Publishing AG, 2023).

Smith, P. E. et al. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150 (1), 76–85 (1985).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 (15), 2114–2120 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 (7), 644 (2011).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7 (10), e1002195 (2011).

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (D1), D222–D230 (2014).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31 (19), 3210–3212 (2015).

Götz, S. et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (10), 3420–3435 (2008).

Hunter, S. et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (suppl_1), D211–D215 (2009).

Ye, J. et al. WEGO 2.0: a web tool for analysing and plotting GO annotations, 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (W1), W71–W75 (2018).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 1–16 (2011).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9 (4), 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25 (16), 2078–2079 (2009).

Baker, J. E. & Woo, S. M. ß-glucosidases in the rice weevil, sitophilus oryzae:purification, properties, and activity levels in wheat- and legume-feeding strains. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 22, 495–504 (1992).

Alves, L. C., Almeida, P. C., Franzoni, L., Juliano, L. & Juliano, M. A. Synthesis of N alpha-protected aminoacyl 7-amino-4-methyl-coumarin amide by phosphorous oxychloride and Preparation of specific fluorogenic substrates for Papain. Pept. Res. 9, 92–96 (1996).

Noelting, G. & Bernfeld, P. Sur les enzymes amylolytiqucs III. La β-amylase: dosage d’activité et contrôle de l’absence d’α-amylase. Helv. Chim. Acta. 31, 286–290 (1948).

Twining, S. S. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled casein assay for proteolytic enzymes. Anal. Biochem. 143, 30–34 (1984).

Nicholson, J. A. & Kim, Y. S. A one-step l-amino acid oxidase assay for intestinal peptide hydrolase activity. Anal. Biochem. 63, 110–117 (1975).

Erlanger, B. F., Kokowsky, N. & Cohen, W. The Preparation and properties of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 95, 271–278 (1961).

Choi, S. J., Hwang, J. M. & Kim, S. I. A colorimetric microplate assay method for high throughput analysis of lipase activity. BMB Rep. 36, 417–420 (2003).

Filietáz, C. F. T. Caracterização da digestão de lipídeos em vetores hematófagos e o papel fisiológico das lipases (Doctoral thesis, Universidade de São Paulo). (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge Ighor Fernandes and Ryan Romão for the specimen collecting support; Erica Fiadi and Jaderlina Todão for the material preparation and sequencing support; and Chris Cardoso and the Bioinformatics DOJO group for the bioinformatics expertise shared. This work used resources from two High-Performance Computing Systems: one from the Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (NBBC) at Butantan Institute, and the other from the Genetics and Biodiversity Laboratory (LGBIO) at Goiás Federal University, which was supported by the National Institutes for Science and Technology (INCT) in Ecology, Evolution and Biodiversity Conservation, supported by MCTIC/CNPq (proc. 465610/2014-5) and FAPEG (proc. 201810267000023). The research was supported by the Brazilian research agencies FAPESP (Grant number 2017/08103-4) and CAPES.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O.S. Specimens collection; experimental execution, bioinformatics, data analysis and manuscript composition; V.L.V. Critical reading, experimental design and execution; R.O.D. Critical reading and bioinformatics analysis; C.F. Critical reading; W.R.T. Critical reading; R.P.R. Critical reading and species identification; A.R.L. Experimental design, data analysis and manuscript composition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, J.O., Viala, V.L., Dias, R.O. et al. Digestion in the arachnid Mischonyx squalidus as a probable source of lipids to synthesize opiliones defense and communication molecules. Sci Rep 15, 32732 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18180-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18180-x