Abstract

Current evidence suggests a strong correlation between specific body hormones and skeletal maturation; however, there is very limited literature available on salivary hormonal levels and their correlation with craniofacial skeletal growth. The primary objective of this study was to collect preliminary data on the salivary Growth Hormone, Cortisol, Testosterone, and 17β-Estradiol levels of orthodontic patients with specific age groups. In this cross-sectional cohort study, a total of 80 patients (40 females and 40 males) were recruited. 5 ml saliva was collected by a passive drooling method for an ELISA test of Cortisol, 17β-Estradiol, Testosterone, and Growth Hormone (GH). Lateral cephalograms were acquired for the middle phalanx of the third figure (MP3) stages and Cervical Vertebral Maturity Indicator (CVMI). We observed that the GH concentration was highest for females between the ages of 10–11 years (12.0 ± 4.2 pg/ml) and for males between the ages of 13–14 years (13.4 ± 11.6 pg/ml). The prepubertal stage (10–12 years) for female subjects, MP3, and CVMI stages were observed to be 2.5. This study concludes that the salivary growth hormone was highest for ages 10–11 females and age 13–14 males, then gradually declined as the age of the subjects increased. The trend for the Testosterone level was identical between males and females till the age of 13; thereafter, males showed higher salivary Testosterone than female subjects. These findings show promising application of salivary hormonal analysis for the growth prediction. Specifically, level of salivary GH can be used as a non-invasive tool for the skeletal maturation assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate prediction of facial growth and assessment of skeletal maturity is essential to success of orthopedic treatment in children and surgical treatment planning in adolescent patients1. The peak of mandibular growth during puberty is a critical time to resolve skeletal discrepancies2,3,4. Milo Hellman’s observation that facial growth undergoes periods of acceleration and deceleration was a major advance in the understanding of facial growth5,6. Today, it is a common agreement that treatment during adolescent growth spurt increases the efficiency and effectiveness of orthodontic treatment, especially for a Class II malocclusion7,8,9.

The hand-wrist staging is perhaps the most established and reliable method of assessing skeletal maturation because of recognizable sequence of developmental stages and the ease with which radiographs can be obtained. However, several key hand-wrist events (e.g., the appearance of the adductor sesamoid) appear at or near the peak of pubertal growth spurt and thus have little use in predicting spurt’s onset10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Furthermore, Lamparski introduced skeletal maturity assessment by a well-defined changes in cervical vertebrae that are visible on routine lateral cephalograms17,18. Together, hand-wrist and lateral cephalogram might serve to assess a patient’s current development19. However, due to factors like individual variability of onset, duration, and velocity of growth, ethnic and demographic differences, limitations of imaging modalities, subjective interpretation, limitation with an accurate prediction of onset and completion of growth spurts, and other influential parameters such as hormonal imbalances, certain medical conditions, and medications can also affect growth patterns, making predictions based solely on skeletal maturity less reliable.

Recently, researchers have started studying different hormones secreted from the pituitary, thyroid, or adrenocortical glands, such as growth hormone and sex hormones, and their effects on skeletal development of individuals20. The growth hormone (GH), which is secreted by the pituitary, plays an important role in longitudinal bone growth21. Testosterone typically increases Growth Velocity (GV) in association with an increase in GH/ Insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1)22. In addition, GH and estrogen levels show positive correlations in prepubertal girls and boys21,22. Due to well-documented correlation between individual growth and hormonal activities, it is important to explore the possibility of utilizing salivary hormonal markers for orthodontic treatment planning.

Saliva is a potential source of biomarkers for accurately predict growth stages. Salivary biomarker analysis is non-invasive, which makes it advantageous for large-scale screening of orthodontic patients in which repeated samples are required. Similar to blood, saliva is a complex fluid containing a variety of enzymes, hormones, antibodies, antimicrobial constituents, and growth factors23. Very limited evidence regarding salivary hormonal analysis is available in the literature.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate salivary hormonal levels (Growth hormone, Cortisol, Testosterone, and 17β-Estradiol) in male and female patients between 10 and 18 years of age. Additionally, this study was focused on identifying the variation in the salivary hormones based on age and gender. It was also part of the study to correlate salivary hormones with cervical vertebral maturity indicators (CVMI) and skeletal maturity indicator (SMI) using middle phalanx of the third finger (MP3). Salivary hormonal levels were also assessed with skeletal classification, growth pattern, age, and gender. This study tried to identify a significantly higher level (if any) of salivary hormones in patients of certain age groups. The null hypothesis posited that there were no notable variations in salivary hormonal levels either between males and females or across different age groups.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the University of Louisville, Human Subject Research and Institutional Review Board (IRB# 20.0699) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki24. Informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian for all study participants prior to their inclusion in the study. In this cross-sectional cohort study, a total of 80 patients (40 females and 40 males) were recruited. Patients from 10 to 18 years of age who were screened for orthodontic treatment were included. Information such as age, gender, and date of birth was recorded in the datasheet. The inclusion criteria were: (1) healthy patient, non-smoker; (2) 10 to 18 years of age; (3) patient screening for orthodontic treatment and getting the lateral cephalogram as a standard of care for his or her orthodontic treatment. The exclusion criteria were set as follows because these might have affected the overall treatment duration: (1) evidence of extremely poor oral hygiene; (2) patients on medications that may alter bone metabolisms like bisphosphonates, oral contraceptives or PTH (parathormones); (3) chronic illness or syndromic patients. After confirming eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study is explained to the patients and/or their parents, who are then asked to provide informed consent and sign the HIPAA authorization form. No exclusion from the study was performed once the study participants were included in the study. This study followed the STORBE guidelines for reporting observational cohort studies25.

Study subjects were distributed in eight age groups (10–11, 11–12…, and 17–18 years of age), with five males and five females in each group. Random sequences were generated from random.org and were assigned to a patient in each group for blinding of salivary samples during processing. Lateral cephalograms and middle phalanx of third finger (MP3) were acquired in same radiograph by asking the patient to put his/her left middle finger closer to the nose during exposure. Six stages of CVMI and five stages of MP3 were used as the skeletal maturity index16,26. Team responsible for salivary hormonal analysis and skeletal maturity (CVMI and MP3) assessment were blinded to random sequences.

The morning appointment was chosen for salivary samples to maintain the consistency between different individuals. 5 ml saliva was collected by a passive drooling method in the sterile 50 ml falcon tube. Samples were aliquoted into a 1.5 ml tube and centrifuged at 4 °C at 13,600 rpm for 20 min, and the top aqueous layer was stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

Lateral cephalograms of all enrolled patients were assigned in different powerpoint slides. Based on the ANB angle, subjects were categorized into Class I (ANB = 1–4°), Class II (ANB > 4°), and Class III (ANB < 1°). Based on the FMPA, subjects were categorized as Hypodivergent (FMPA < 21°), Normodivergent (FMPA = 21–28°), and Hyperdivergent (FMPA > 28°). Also, Go-Gn to SN was used to determine the growth pattern: Hypodivergent (GoGn-SN < 27°), Normodivergent (GoGn-SN 27–37°), and Hyperdivergent (GoGn-SN > 37°). Two individual powerpoint files, one for CVMI and other for MP3, were provided to two experienced raters individually for grading. Raters were blinded for the age and sex of the patients.

The stored salivary samples were thawed to room temperature for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) hormonal analysis. We used Cortisol, 17β-Estradiol, and Testosterone ELISA kits by Enzo life sciences (NY, USA). These were highly sensitive colorimetric competitive ELISA kits with absorbance read at 405 nm. For the human growth hormone, we used the AuthentiKine™ human growth hormone ELISA kit by Proteintech (IL, USA). It was a solid phase sandwich ELISA kit with absorbance read at 450 nm. The manufacturer manual was followed for all four ELISA tests. All tests were done in duplication to eliminate the bias in readings.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to report the data on Cortisol, 17β-Estradiol, Testosterone, and Growth hormone based on the age groups, gender, CVMI stages, and MP3 stages. An unpaired sample t-test was conducted to compare the age-specific hormonal levels between male and female patients. Age and Gender-specific descriptive statistics were used to report 25% quartile (Q1), median, and 75% quartile (Q3) of CVMI and MP3 stages. Gender-specific CVMI and MP3 stages for prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal groups are reported as part of statistical analysis.

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare the salivary hormonal levels among different age groups for female and male patients. Tukey HSD test was used for the multiple comparisons of salivary hormones between different age groups. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the CVMI and MP3 stages amongst different age groups for female and male patients. Dunn’s test was used for the multiple comparisons of CVMI and MP3 stages between different age groups. Similar tests were used to compare salivary hormones, CVMI, and MP3 stages for prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal age groups for male and female patients. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for the salivary hormonal concentration with that of the Age, Age group, ANB, FMPA, GoGn-SN, CVMI, and MP3 stages. Inter-rater reliability of CVMI and MP3 stages was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa analysis. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism statistical software.

Results

Salivary hormonal analysis

Salivary hormonal levels across different age-groups and sexes

Salivary hormonal profiles varied across age groups and between sexes, with notable differences observed for specific biomarkers. A sex-specific comparison of salivary hormonal levels across different age groups revealed non-significant differences in Cortisol, 17β-Estradiol, and Testosterone (p-value > 0.05). However, GH showed significant differences for male subjects between specific age groups.

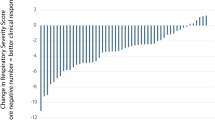

Among female subjects, mean Cortisol concentrations demonstrated a bimodal distribution, with peaks at ages 14–15 (150.3 ± 112.7 pg/mL) and 12–13 years (137.9 ± 86.6 pg/mL). In males, levels were more variable, peaking at age 15–16 (199.9 ± 170.7 pg/mL) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Although one-way ANOVA did not identify statistically significant age-related differences within sexes (p = 0.058 for females, p = 0.235 for males) (Table 2), unpaired t-tests (female vs. male) revealed a significant difference at 13–14 years (p = 0.033), with females exhibiting lower cortisol levels compared to males (Table 3).

For 17β-estradiol, mean levels were highly variable across age groups in both sexes. Females showed a peak at age 11–12 (94.4 ± 122.8 pg/mL), while males demonstrated a gradual increase with age, reaching a maximum at 17–18 years (113.5 ± 32.2 pg/mL) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Although no significant within-sex variation was observed (p > 0.3 in both groups) (Table 2), between-sex comparison indicated a significant difference at 17–18 years (p = 0.012), where males exhibited higher levels than females (Table 3).

Testosterone levels demonstrated a progressive rise with age in both sexes. In females, mean values increased from 80.5 ± 49.5 pg/dL at age 10–11 to 147.8 ± 160 pg/dL at age 16–17, followed by a slight decline at age 17–18. Among males, a pronounced and consistent increase was noted, with levels rising from 88.5 ± 24.9 pg/dL at age 10–11 to 255.1 ± 118.9 pg/dL at age 17–18 (Table 1, Fig. 1). However, ANOVA results indicated no significant differences within each sex (p = 0.609 for females, p = 0.064 for males), though the latter approached significance (Table 2). Between-sex comparisons reached significance at 17–18 years (p = 0.048), confirming expected sexual dimorphism in testosterone during late adolescence (Table 3).

GH concentrations displayed a distinct sex-related trend. In females, it remained relatively consistent across age groups with the highest concentration found between the ages of 10–11 years (12.0 ± 4.2 pg/mL). In males, a significant peak in GH levels was observed at ages 13–14 (13.4 ± 11.6 pg/mL) (Table 1, Fig. 1). ANOVA confirmed a significant age-related difference in males (p = 0.042), but not in females (p = 0.219) (Table 2). Additionally, unpaired t-test (female vs. male) results showed significantly higher growth hormone levels in females compared to males at age 10–11 (p = 0.044) (Table 3). Tukey HSD tests showed significant differences for males between age groups of 13–14 years vs. 12–13 years (p = 0.049) and 13–14 years vs. 16–17 years (p = 0.026) age groups. These findings suggest a transient elevation in growth hormone during peak growth spurt ages in males (Table 4).

Salivary hormonal levels across prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal groups

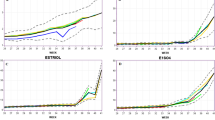

Salivary hormonal levels demonstrated significant age- and sex-related variations when stratified by both chronological age and developmental stages. When grouped by puberty stages (prepubertal: 10–12, pubertal: 12–14, post-pubertal: 14–16), Cortisol concentrations increased with maturation in both sexes. In females, levels increased from 70.2 ± 33.9 pg/mL (prepubertal) to 127.2 ± 80.5 pg/mL (post-pubertal), while in males, values peaked during puberty (128.7 ± 137.5 pg/mL) and slightly declined post-pubertally (117.6 ± 67.9 pg/mL) (Table 5, Fig. 2). However, these trends did not reach statistical significance in ANOVA (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

17β-Estradiol showed divergent patterns between sexes. In females, a non-linear trend was noted with a pubertal dip (22.7 ± 22.3 pg/mL) followed by a post-pubertal increase (60.5 ± 62.4 pg/mL), whereas males showed a steady rise across puberty stages from 53.7 ± 68.4 to 75.3 ± 43.4 pg/mL (Table 5, Fig. 2). Despite these shifts, statistical tests did not confirm significance across stages (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Testosterone levels rose consistently with pubertal development in both sexes. Female levels increased from 97.4 ± 66.6 pg/mL (prepubertal) to 120.2 ± 37.1 pg/mL (post-pubertal), while in males, levels increased more markedly from 123.5 ± 94.0 to 220.6 ± 88.3 pg/mL (Table 5, Fig. 2). No significant difference was found across stages (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

GH levels declined with pubertal progression in both sexes. In females, levels dropped from 10.0 ± 4.5 pg/mL (prepubertal) to 5.5 ± 3.2 pg/mL (post-pubertal), and in males from 8.1 ± 9.5 to 3.6 ± 3.4 pg/mL (Table 5, Fig. 2). Comparison between these three groups showed non-significant difference for GH for both males and females (Table 6).

Skeletal maturity indicators (CVMI and MP3)

Skeletal maturity indicators (CVMI and MP3) across different age-groups and sexes

The weighted kappa was 0.895 (z = 12.4) for CVMI and 0.966 (z = 11) for MP3, and the unweighted kappa was 0.817 (z = 13.8) for CVMI and 0.925(z = 13.4) for MP3, showing excellent inter-rater reliability for the CVMI and MP3 gradings.

Descriptive statistics for CVMI and MP3 stages (Table 7, Fig. 3) revealed consistent increases in maturity scores with age. Among females, the CVMI median reached stage 5 by age 12–13 and remained stable thereafter, with interquartile ranges narrowing indicating maturation plateau. A similar pattern was noted in MP3 stages, with all subjects reaching stage 5 by age 12–13, except for earlier age groups (Table 7, Fig. 3). Furthermore, CVMI comparison between different age groups for females showed statistically significant differences between early and mid-to-late adolescent groups. Specifically, the stages significantly increased between 10–11 vs. 15–16 (p = 0.043), 10–11 vs. 16–17 (p = 0.008), and 11–12 vs. 16–17 (p = 0.043). MP3 staging results also demonstrated strong significance across several pairings: 10–11 vs. 14–15, 15–16, 16–17, and 17–18 (p = 0.009), and 11–12 vs. those same groups (p = 0.039), indicating consistent and rapid maturation during early puberty in females (Tables 2 and 4).

In males, CVMI progression was more gradual; the median reached stage 5 at 17–18 years, with earlier ages showing broader interquartile ranges, reflecting individual variability in maturation timing. MP3 staging in males also revealed a wider distribution; by age 16–17, the median reached stage 5, but earlier age groups (especially 12–13) showed much lower medians and quartiles, reinforcing the delayed skeletal maturation compared to females (Table 7, Fig. 3). Furthermore, CVMI comparison between different age groups for males showed a significant advancement between ages 11–12 and 17–18 (p = 0.005), reflecting the expected pubertal maturation trajectory. Similarly, MP3 staging demonstrated progressive maturation, with significant differences between 12–13 vs. 16–17 (p = 0.028), 11–12 vs. 17–18 (p = 0.030), and 12–13 vs. 17–18 (p = 0.007). These findings support the sensitivity of MP3 and CVMI indicators in capturing the onset and progression of skeletal maturity during adolescence in males (Tables 2 and 4).

Skeletal maturity indicators (CVMI and MP3) across prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal groups

Significant differences in skeletal maturity were observed across prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal stages in both male and female subjects. As shown in Table 6, for CVMI, the p-values were highly significant in females (p = 0.00061) and males (p = 0.00371). Likewise, MP3 staging showed even greater significance in both sexes (p = 0.00002 in females, p = 0.00004 in males), indicating a strong association between skeletal maturity and pubertal progression (Table 6).

Descriptive quartile data from Table 8 support these findings. Among females, the CVMI median increased from 2.5 in the prepubertal group to stage 5 in pubertal and post-pubertal groups. Similarly, MP3 stages progressed from a median of 2.5 in prepubertal subjects to stage 5 by the pubertal stage, with post-pubertal subjects showing a stable plateau. This suggests that most females reach skeletal maturity earlier during adolescence (Table 8, Fig. 3).

In males, both CVMI and MP3 staging showed a more gradual progression. The CVMI median increased from stage 3 in pubertal subjects to 4 in post-pubertal subjects. MP3 staging was more variable: the prepubertal group had a median of stage 2, while the pubertal group reached a median of 3.5, and the post-pubertal group attained a median of stage 5.0. These values highlight the later skeletal maturation observed in males compared to females (Table 8, Fig. 3).

Dunn’s tests (Table 9) further validated these trends. In females, CVMI stages showed significant differences between prepubertal and pubertal (p = 0.010), and prepubertal and post-pubertal groups (p = 0.001). MP3 stages demonstrated even stronger contrasts, with adjusted p-values of 0.002 and 0.00002, respectively. In males, CVMI significantly increased between pubertal and post-pubertal stages (p = 0.002), while MP3 comparisons revealed progressive maturation from 12–14 to 14–16 (p = 0.00997) and from 12–14 to 16–18 (p = 0.00003) (Table 9).

Salivary hormonal trends across skeletal maturity stages (CVMI and MP3)

Salivary hormonal profiles varied meaningfully across skeletal maturity stages as defined by CVMI (CS1-CS6) and MP3 (Stages 1–5). For Cortisol, females exhibited an increasing trend from CS1 (72.5 pg/mL) to CS5 (101.1 pg/mL), with a slight decline at CS6 (96.1 pg/mL). In contrast, males showed a bimodal distribution, with a peak at CS4 (138.1 pg/mL) and a dip at CS5 (62.0 pg/mL). Cortisol levels measured by MP3 stages mirrored this variability, peaking at MP3 stage 5 in both sexes (Table 10).

For 17β-Estradiol, females displayed a peak at CS2 (71.2 pg/mL), followed by stabilization at CS4 and CS5. Male 17β-Estradiol levels steadily increased with CVMI stage, reaching their highest mean (132.5 pg/mL) at CS5. When analyzed by MP3 staging, estradiol levels in males rose from 62.1 pg/mL at MP3-1 to 77.8 pg/mL at MP3-3, stabilizing thereafter, while female levels were less consistent but highest at MP3-2 (Table 10).

Testosterone levels showed expected sex-specific patterns. In females, mean testosterone remained relatively stable across CVMI stages, ranging from 87.5–155.4 pg/mL between CS4 and CS6. In males, a marked increase was noted at CS4 (215.5 pg/mL), consistent with pubertal progression. MP3-based staging revealed a peak in testosterone at MP3-5 for both sexes, reaching 195.2 pg/dmL in males and 110.3 pg/mL in females (Table 10).

GH levels exhibited a declining trend with advancing skeletal maturity. In females, the highest values were observed at CS1 (14.9 pg/mL), decreasing to 4.4 pg/mL at CS6. A similar decline was noted across MP3 stages, from 11.0 pg/mL at MP3-2 to 6.1 pg/mL at MP3-5. Males showed relatively stable growth hormone concentrations across CVMI stages (mean range: 5.2–6.7 pg/mL), with slight variation across MP3 stages but no consistent directional trend (Table 10).

4-parametric logistic standard curves were utilized to calculate the concentration of unknown salivary samples by best-fit equations provided in Supplemental Figs. 1–4. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to assess the salivary hormones and age, age groups, ANB, FMPA, GoGn to SN, CVMI, and MP3. The correlation matrix in the form of a heat map is reported in Fig. 4. CVMI and MP3 showed a positive correlation (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) as skeletal maturity indicators.

Discussion

This study comprehensively evaluated salivary hormone profiles for Cortisol, 17β-Estradiol, Testosterone, and GH in relation to SMI defined by both chronological age and radiographic indicators (CVMI and MP3). While most hormones did not demonstrate statistically significant variation across narrow age bands, clear sex-specific and stage-specific patterns emerged when stratified by pubertal developmental stages and skeletal maturity indices. Notably, GH levels exhibited a transient elevation during mid-pubertal stages in males and a progressive decline in females with advancing skeletal maturity. Testosterone demonstrated a consistent increase with age and maturation in males, aligning with known pubertal physiology. Additionally, CVMI and MP3 indices proved to be a reliable indicator of skeletal development, with females reaching peak stages earlier than males. These findings underscore the potential clinical utility of combining salivary biomarkers with radiographic maturity indicators to enhance growth assessment during adolescence.

During puberty, the pulsatile secretion of growth hormone (GH) increases by approximately 1.5- to threefold27. Twenty-four-hour GH secretion reaches its peak during adolescence, largely contributing to the elevated serum levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) that characterize this developmental phase20,21. The rise in GH output during mid-to-late puberty is attributed to enhanced pulse amplitude and a greater mass of GH per secretory burst, rather than changes in pulse frequency. Interestingly, androgens such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and synthetic anabolic agents like oxandrolone have been shown to accelerate growth velocity in boys with delayed puberty without significantly altering circulating GH or IGF-1 levels28,29,30,31. In this study, the highest concentration of GH was observed for girls of age 10–11 years, and for boys, it peaked for age 13–14 years. Also, there is a significant drop in the levels of GH within a year after reaching the peak levels. This strengthens our understanding of the growth spurts and how their timeline differs for boys and girls.

The interaction between estrogen and GH plays a pivotal role in pubertal development. Estrogen’s stimulatory effect on GH secretion is primarily mediated through estrogen receptors α and β expressed in the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus. In peri-pubertal individuals, endogenous estrogen enhances GH sensitivity, and estrogen priming has been shown to augment GH release in normal adolescents32,33. Conversely, suppression of estrogen signaling is associated with reduced GH secretion34. These observations support a well-established correlation between estrogen and GH concentrations throughout normal female puberty, with GH levels generally higher in females than in males35,36,37. Consistent with these findings, the present study identified a definitive peak in GH concentrations, while 17β-estradiol levels showed more variable patterns. The lack of a clear estradiol peak may reflect biological variability or the limitations of sample size, warranting further investigation with a larger cohort.

Testosterone’s influence on GH secretion is largely attributed to its aromatization to estrogen28,29,30. While this study did not find statistically significant differences in testosterone levels across age groups, a consistent age-related increase was observed in both sexes, aligning with known endocrinologic patterns during puberty. The absence of significance may again be attributed to sample size constraints or the heterogeneity of pubertal timing among subjects.

Skeletal maturity remains a key determinant in assessing growth potential. While hand-wrist radiographs have traditionally served as maturity indicators, their predictive value for the onset of the pubertal growth spurt is limited, as key ossification events (e.g., adductor sesamoid appearance) often occur around peak height velocity10,11,12,13,14,15,16. In contrast, vertebral-based indices such as CVMI and MP3 offer greater clinical utility for assessing growth status and potential. The current study adopted these indices to classify subjects into prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal groups, providing a skeletal framework that correlates more directly with facial and skeletal development than chronological age alone.

The peak of the adolescent spurt is generally thought to occur at the approximate ages of 12 years in girls and 14 years in boys. The onset of the spurt occurs approximately two years before the peak10,11,27,38,39,40,41,42. The findings corroborate established patterns of sexual dimorphism in pubertal timing. Although mean chronologic age can serve as a guide to treatment timing, there are sufficient individual variations to prompt investigators to search for some skeletal age that might be better correlated with growth of the face42,43,44,45,46. Among females, the median CVMI and MP3 stages were both 2.5 in the prepubertal group (ages 10–12), advancing to stage 5 by the pubertal phase (ages 12–14). This transition occurred over a relatively short interval, suggesting a rapid and consolidated skeletal maturation phase. In contrast, males exhibited slower progression, with prepubertal CVMI and MP3 medians of 3 and 2, respectively (ages 12–14), and continued skeletal growth evident in the 14–16 age range, where CVMI remained at stage 3 and MP3 at stage 2. These trends reinforce the notion that female skeletal maturation precedes that of males by approximately two years, consistent with previous longitudinal studies.

Since this study included a limited number of patients in each group, statistical inferences should be interpreted with caution. Future direction of this project should be to expand the scope of the study to include patients younger than 10 years and older than 18 years of age with a significantly larger sample size. Irrespective of the limitations, this project provided valuable information regarding the trends and variability of salivary hormonal levels in different genders, age groups, and skeletal maturity indicators. This study opens a new horizon for future projects with a larger sample size and establishes the norms for the salivary hormonal levels in patients of different age groups.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant for orthodontic treatment planning, particularly in timing growth modification interventions. SMIs such as CVMI and MP3 remain more reliable than chronological age alone for assessing pubertal timing and residual growth potential. Our results demonstrated that females reached CVMI and MP3 stage 5 by ages 12–14, while males often remained at stages 3–4 until ages 14–16, suggesting a longer growth window in boys. This is consistent with large-scale longitudinal studies showing that peak mandibular growth typically occurs around CVMI stage 4 in females and stage 3–4 in males47. Moreover, previous research has shown that incorporating skeletal maturity assessments alongside endocrine biomarkers such as IGF-1 or GH may improve the prediction of individual growth trajectories48. Therefore, the integration of salivary hormone profiling with radiographic maturity indicatorsn as demonstrated in this study offers a promising non-invasive strategy to enhance growth prediction and optimize treatment timing in clinical orthodontics.

Summary

This study provides strong evidence that it is possible to detect traces of specific hormones in human saliva. This can serve as an easy, non-invasive, and inexpensive tool with tremendous potential for a variety of applications, including predicting the remaining growth of orthodontic patients.

Salivary growth hormone in female patients was highest for ages 10–11 and then gradually declined as the age of the subjects increased, with a consistently low level found after the age of 13 years. On the other hand, the highest salivary growth hormone for the male patient was found for ages 13–14 years and then declined after the age of 14 years onwards. The trend for the testosterone level was identical between males and females till the age of 13; thereafter, males showed higher salivary testosterone than female subjects. Cortisol and 17β-Estradiol levels showed alternative high and low levels as the age of the subjects increased.

CVMI and MP3 showed a positive correlation (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) as skeletal maturity indicators. CVMI stage was lowest (CS 2) for the females of 10–11 years of age, with a gradual increase toward CS 5 after the age of 12 years. Similarly, a fusion of the epiphyseal plate of MP3 was observed in females at the age of 12 years, indicating minimal growth afterward. On the other hand, the CVMI stage was lowest (CS 1) for the male patients 11–12 years of age, with a gradual increase towards CS 4 at the age of 13–14 years. Thereafter, it remained statically CS 4 until the age of 16–17 years; after that, CS 5 was observed at 17–18 years. Similarly, the MP3 stage was lowest for male patients at the age of 12–13 years, followed by a gradual increase in the maturation, and ultimately, fusion of the epiphysial plate was observed following the age of 16–17 years.

CVMI (r = − 0.101) and MP3 (r = − 0.186) stages showed a weak and non-significant correlation with the salivary growth hormone. Future studies with larger sample size are recommended to support this conclusion.

Data availability

All data associated with this study are presented in the paper or the Supplementary Information. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Baumrind, S. Prediction in the planning and conduct of orthodontic treatment. In Current Controversies in Orthodontics (ed. Melson, B.) 25–43 (Quintessence, 1991).

Bishara, S. E. Facial and dental changes in adolescents and their clinical implications. Angle Orthod. 70, 471–483 (2000).

Petrovic, A., Stutzmann, J., Lavergne, J. & Carlson, D. S. Mechanisms of craniofacial growth and modus operandi of functional appliances: A cell-level and cybernetic approach to orthodontic decision making. In Craniofacial Growth Theory and Orthodontic Treatment (ed. Carlson, D. S.) 13–73 (University of Michigan, 1990).

Malmgren, O., Omblus, J., Hägg, U. & Pancherz, H. Treatment with an orthopedic appliance system in relation to treatment intensity and growth periods. A study of initial effects. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 91, 143–151 (1987).

Hellman, M. Changes in the human face brought about by development. Int. J. Orthod. Oral Surg. Radiogr. 13, 475–516 (1927).

Hellman, M. The face in its developmental career. Dent. Cosmos 77, 685–699 (1935).

Johnston, L. E. Jr. A comparative analysis of Class II treatments. In Science and Clinical Judgement in Orthodontics (eds. McNamara, J. A. Jr., Carlson, D., Vig, P. & Ribbens, K.) Monograph 18, Craniofacial Growth Series (University of Michigan, 1986).

Bishara, S. E., Jakobsen, J. R., Vorhies, B. & Bayati, P. Changes in dentofacial structures in untreated Class II division 1 and normal subjects: A longitudinal study. Angle Orthod. 67, 55–66 (1997).

Johnston, L. E. Jr. Growth and the Class II patient: Rendering unto Caesar. Semin. Orthod. 4, 59–62 (1998).

Grave, K. C. Timing of facial growth: A study of relations with stature and ossification in the hand around puberty. Aust. Orthod. J. 3, 117–122 (1973).

Bowden, B. D. Epiphysial changes in the hand/wrist area as indicators of adolescent stage. Aust. Orthod. J. 4, 87–104 (1976).

Bambha, J. & Van Natta, P. Longitudinal study of facial growth in relation to skeletal maturation during adolescence. Am. J. Orthod. 49, 481–493 (1963).

Bowden, B. D. Sesamoid bone appearance as an indicator of adolescence. Aust. Orthod. J. 2, 242–248 (1971).

Tofani, M. I. Mandibular growth at puberty. Am. J. Orthod. 62, 176–195 (1972).

Grave, K. C. & Brown, T. Skeletal ossification and the adolescent growth spurt. Am. J. Orthod. 69, 611–619 (1976).

Hägg, U. & Taranger, J. Maturation indicators and the pubertal growth spurt. Am. J. Orthod. 82, 299–309 (1982).

Lamparski, D. Skeletal age assessment utilizing cervical vertebrae [thesis]. (University of Pittsburgh, 1972).

Hassel, B. & Farman, A. G. Skeletal maturation evaluation using cervical vertebrae. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 107, 58–66 (1995).

Bernard, D. O. Predetermination of the time of the facial growth spurt utilizing the cervical vertebrae [thesis]. (Case Western Reserve University, 1976).

Perry, R. J., Farquharson, C. & Ahmed, S. F. The role of sex steroids in controlling pubertal growth. Clin. Endocrinol. 68, 4–15 (2008).

Veldhuis, J. D., Roemmich, J. N. & Rogol, A. D. Gender and sexual maturation-dependent contrasts in the neuroregulation of growth hormone secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 2385–2394 (2000).

Kerrigan, J. R. & Rogol, A. D. The impact of gonadal steroid hormone action on growth hormone secretion during childhood and adolescence. Endocr. Rev. 13, 281–298 (1992).

Gandhi, V., O’Brien, M. H. & Yadav, S. High-quality and high-yield RNA extraction method from whole human saliva. Biomark. Insights 15, 1–8 (2020).

World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(2191–2194), 44 (2013).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61(344–349), 45 (2008).

Baccetti, T., Franchi, L. & McNamara, J. A. The cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) method for assessment of optimal treatment timing. Semin. Orthod. 11(119–129), 46 (2005).

Melmed, S., Polonsky, K. S., Larsen, P. R. & Kronenberg, H. M. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th edn, 1009–1037 (Saunders, 2012).

Eakman, G. D., Dallas, J. S., Ponder, S. W. & Keenan, B. S. The effects of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone on growth hormone secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81, 1217–1223 (1996).

Malhotra, A. et al. Effects of oxandrolone on growth hormone and gonadal axes in boys with delayed puberty. Clin. Endocrinol. 38, 393–398 (1993).

Crowne, E. C. et al. Effect of oxandrolone and testosterone on pituitary-testicular and GH axes in delayed puberty. Clin. Endocrinol. 46, 209–216 (1997).

Keenan, B. S. et al. Androgen-stimulated pubertal growth: Testosterone and IGF-I effects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 76, 996–1001 (1993).

Coutant, R. et al. Divergent effects of sex steroids on IGF-I response to GH in adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 6185–6192 (2004).

Marin, G. et al. Estrogen priming and puberty effects on GH response to exercise. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 79, 537–541 (1994).

Hero, M., Norjavaara, E. & Dunkel, L. Aromatase inhibition increases height in boys. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 6396–6402 (2005).

Wennink, J. M. et al. GH secretion patterns relative to LH and estradiol during puberty. Acta Endocrinol. 124, 129–135 (1995).

Ho, K. Y. et al. Effects of sex and age on GH secretion: role of estradiol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 64, 51–58 (1987).

Winer, L. M., Shaw, M. A. & Baumann, G. Rhythmicity of basal GH levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 70, 1678–1682 (1990).

Bambha, J. K. Longitudinal cephalometric roentgenographic study of face and cranium in relation to body height. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 63, 776–799 (1961).

Bjork, A. & Helm, S. Prediction of the age of maximum puberal growth in body height. Angle Orthod. 37, 134–143 (1967).

Tanner, J. M., Whitehouse, R. H., Marubini, E. & Resele, L. F. The adolescent growth spurt of boys and girls of the Harpenden growth study. Ann. Hum. Biol. 3, 109–126 (1976).

Bogin, B. Evolutionary perspective on human growth. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 28, 109–153 (1999).

Johnston, F. E., Hufham, H. P. Jr., Moreschi, A. F. & Terry, G. P. Skeletal maturation and cephalofacial development. Angle Orthod. 35, 1–11 (1965).

Bergersen, E. O. The male adolescent facial growth spurt: its prediction and relation to skeletal maturation. Angle Orthod. 42, 319–338 (1972).

Fishman, L. S. Chronological versus skeletal age, an evaluation of craniofacial growth. Angle Orthod. 49, 181–189 (1979).

Nanda, R. S. The rates of growth of several facial components measured from serial cephalometric roentgenograms. Am. J. Orthod. 41, 658–673 (1955).

Hunter, C. J. The correlation of facial growth with body height and skeletal maturation at adolescence. Angle Orthod. 36, 44–54 (1966).

Franchi, L., Baccetti, T. & McNamara, J. A. Jr. Mandibular growth as related to cervical vertebral maturation and body height. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 118, 335–340 (2000).

Masoud, M. I., Marghalani, A. A. & Masoud, I. M. The relationship between IGF-1 levels and skeletal maturation indicators. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 142, 654–661 (2012).

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dr. David Scott for allowing us to utilize the lab and the necessary equipment for this study. Special thanks to Ms. Gwyneth Lamont for helping with ELISA tests for the salivary hormonal analysis. I also would like to thank Dr. Lisa Sandell for her feedback and suggestions in building up the proposal for the grant application and securing the funding to execute this project. I want to thank Dr. Bhumika Patel and Dr. Amine Fattal for volunteer participation as blind evaluators for the CVMI and MP3 stages of my study subjects. Finally, I thank Dr. Sekula for helping me with the extensive statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.G.: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. S.G.: Contributed to conception, design, and critically revised the manuscript. G.B.: Contributed to conception, supervised, and critically revised the manuscript. S.A.: Contributed to conception, supervised, and critically revised the manuscript. T.D.: Contributed to conception, supervised, and critically revised the manuscript. S.Y.: Contributed to conception, supervised, and critically revised the manuscript. S.C.: Contributed to conception, supervised, and critically revised the manuscript. J.N.: Contributed to conception, design, and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gandhi, V., Gudhimella, S., Bradley, G.T. et al. Salivary hormonal analysis as a tool for skeletal maturity assessment. Sci Rep 15, 33538 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18182-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18182-9