Abstract

Titanium implants possess bioinert surfaces that limit osseointegration and are prone to bacterial colonization, necessitating functional coatings. This study investigated the electrophoretic deposition (EPD) of composite coatings composed of chitosan (CS), nanohydroxyapatite (nanoHAp), and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on grade 2 titanium using an ethanol–acetic acid suspension. The influence of deposition parameters (10–30 V; 3–5 min) on coating microstructure, adhesion, corrosion resistance, wettability, bioactivity, and silver release was systematically examined. The coatings reached a maximum thickness of ~ 7 μm at 30 V/5 min, while the most uniform and adherent coating (class 1, EN ISO 2409) was obtained at 10 V/3 min. Increasing voltage and time produced rougher (Sa up to 1.3 μm) and more porous surfaces, but decreased adhesion. Corrosion resistance improved with coating thickness, with open circuit potentials shifting positively up to + 0.15 V versus the reference electrode. Wettability tests revealed hydrophilic behavior with contact angles of ~ 80°. Bioactivity in simulated body fluid was confirmed by calcium phosphate precipitation on all coated samples, particularly thicker ones. Silver ion release was controlled by deposition parameters, ranging from 0.9 mg/L (10 V/3 min) to 1.8 mg/L (30 V/5 min) after 7 days, indicating a balance between antibacterial functionality and coating integrity. These results demonstrate that ethanol-based EPD can fabricate bioactive, corrosion-resistant CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings with tunable properties. Optimized coatings show potential for biomedical applications, particularly in reducing implant-associated infections while supporting bone integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing demand for advanced biomaterials in orthopedic and dental implantology has led to intensive research focused on modifying the surfaces of metallic substrates, particularly titanium, to improve their biofunctionality1,2. Titanium and its alloys are commonly used in biomedical applications due to their excellent mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility3. However, their naturally bioinert surfaces often hinder direct bonding with bone tissue and increase the risk of post-surgical infections. To address these issues, composite coatings that incorporate bioactive and antibacterial agents have emerged as a promising solution4.

Among the various surface modification techniques, including sandblasting, etching, plasma treatment, and laser texturing, electrophoretic deposition (EPD) offers significant advantages, including simplicity, cost-effectiveness, uniform coating distribution, and the ability to process complex geometries5,6. Beyond biomedical applications, electrophoretic deposition is widely used in energy storage devices, such as batteries and supercapacitors, as well as in environmental technologies for coating catalysts in wastewater treatment and air purification systems. Its versatility and efficiency make it an attractive method for coating complex surfaces across various industries7,8. The EPD method presents several process parameters that impact the properties of the deposited coatings. These parameters can be divided into two categories: those related to the suspension, such as particle concentrations of the coating material, type of liquid medium, pH, temperature, viscosity, zeta potential, and content of the dispersant; and those related to the technical aspects of the process, including voltages, deposition time, distance between electrodes, and drying methods for the coatings9,10. Recently, EPD has been widely used for producing functional coatings on stainless steel, magnesium alloys, and titanium and its alloys substrates for biomedical applications, enabling the incorporation of bioactive ceramics, polymers, and nanoparticles to tailor surface properties11,12,13. Unlike some chemical solution-based surface treatments, which may involve toxic reagents or generate hazardous waste, EPD is a relatively environmentally friendly technique that uses mild aqueous or alcoholic suspensions14. In the case of water-based suspensions, an unfavorable phenomenon occurs where hydrogen bubbles form on the cathode due to water electrolysis. These bubbles interfere with the uniform deposition of coating particles on the electrode surface, leading to porosity and defects in the coating structure. Additionally, this phenomenon can reduce the adhesion of the coating to the substrate and hinder the reproducibility of the process, particularly at higher voltages and longer deposition times5,15. While using EPD from aqueous suspensions is more environmentally friendly and cost-effective, the presence of water can cause undesirable side effects, particularly during cathode deposition. In biomedical applications, where the quality and uniformity of coatings are essential, employing ethanol as a liquid medium can offer significant advantages. Ethanol, as an organic solvent, does not undergo electrolysis at the typical voltage levels used in EPD. This characteristic helps minimize the formation of gas bubbles during the process. The more stable electrochemical environment that ethanol provides allows for coatings with greater uniformity and better control over the microstructure of the deposited material. This can result in lower porosity, which in turn enhances adhesion. Additionally, ethanol can be mixed with small amounts of organic acids, such as acetic acid, to improve the stability of the suspension or enhance the solubility of certain components16,17,18.

An important aspect of the EPD method is the ability to simultaneously coat conductive substrates with composite coatings. Chitosan (CS), a natural polysaccharide derived from chitin, offers several advantageous properties that make it a desirable material for biomedical applications such as drug delivery, wound healing, and implant coatings19. Key features of CS include its biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and capability to form membranes and coatings with controlled structures20. Additionally, due to the presence of amino groups, CS exhibits antimicrobial activity and the ability to bind and release active substances, which makes it an excellent matrix for composite coatings used on orthopedic and dental implants21. Despite its many benefits, CS is a soft and flexible material that lacks mechanical strength and stiffness. Under moist conditions, it tends to swell and degrade relatively quickly, which can compromise its structural integrity22. As a result, standalone CS coatings are often too soft and mechanically unstable to serve as a permanent protective layer on implants. To enhance both the bioactivity and mechanical properties of CS coatings, additional bioactive ingredients are frequently incorporated.

Hydroxyapatite (HAp) (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) is an inorganic ceramic material that has a chemical composition and crystal structure similar to the mineral phase of human bone tissue. It is known for its excellent bioactivity and osteoconductivity, which promote integration into bone and support regenerative processes, thus its application for bone grafts, dental implants, and as a coating for medical implants, facilitating bone regeneration and integration23,24. However, HAp is a brittle material, making it prone to fracture. It has low resistance to shear and tensile stresses, which means that stand-alone HAp layers can be easily damaged under dynamic loading conditions25,26.

Combining CS with HAp in a composite form improves the overall mechanical properties compared to each component used alone. In this composite system, CS serves as an elastic matrix, increasing HAp’s resistance to fracture and enhancing its adhesion to the substrate. Simultaneously, HAp particles can reinforce the CS structure, resulting in a composite that exhibits greater stiffness, compressive strength, and wear resistance. This combination can lead to a mechanically stable, bioactive coating that is both resistant to degradation and conducive to integration with bone tissue26,27. Furthermore, advancements in nanotechnology are leading to the use of nanometer-sized variants of HAp in biomedical applications. Nanohydroxyapatite (nanoHAp) has a higher surface-to-volume ratio, which enhances its surface reactivity. This results in improved bioactivity and accelerated bone mineralization. Coatings made from nanoHAp exhibit better integration with bone cells, a greater ability to induce apatite deposition in body fluids, and improved adhesion to substrates compared to coatings made from microcrystalline HAp28.

There are numerous examples in the literature of coatings that combine HAp or nanoHAp with CS and other additives obtained by electrophoretic deposition, mainly on titanium and its alloys. For instance, HAp/CS coatings have been deposited on titanium surfaces that were previously subjected to electrochemical oxidation, resulting in the formation of a nanotube oxide layer. The optimal parameters for the deposition of these coatings, determined using the Taguchi method, are set at a voltage of 13 V, a duration of 9 min, and an HAp content of 7.5 g/L29. Efforts were made to deposit CS and HAp coatings onto 316 L stainless steel using different alcohols, including methanol, ethanol, and isopropanol, as the liquid medium. The results indicated that the coatings containing 0.5 g/L of CS and 5 g/L of HAp deposited from ethanol exhibited the highest corrosion resistance in SBF15. Dispersing agents are added to the CS/HAp system to minimize particle agglomeration of the coating material. In study30polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl butyral, and triethanolamine were utilized for this purpose. The agents enhanced the coating process of the titanium substrate by improving the suspension uniformity during deposition (30 V, 10 min) and enabling the formation of highly homogeneous composite coatings. CS/nanoHAp coatings were deposited on a Ti-13Nb-13Zr alloy using the EPD method. In this process, HAp nanoparticles were dispersed in ethanol, leading to the formation of homogeneous coatings. These coatings enhance the corrosion resistance of the titanium alloy substrate in Ringer’s solution and improve its bioactivity31. The EPD method is employed to deposit multi-component coatings on different substrates by utilizing various process parameters. Additional materials such as graphene oxide27,32graphene33bio-glass34,35carbon nanotubes25,36,37iron oxide38collagen39or heparin40 can be incorporated into the CS/HAp or nanoHAp composite. These studies highlight the range of EPD parameters and processing conditions explored for titanium-based substrates, providing a comparative framework for current work on CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs composite coatings.

Bone implants are susceptible to bacterial colonization, so to minimize bacterial adhesion, implant coatings are often enhanced with antibacterial agents. CS, which has inherent antibacterial properties, interacts electrostatically with bacterial cell walls; however, its effectiveness varies depending on the type of bacteria. To improve antibacterial performance, metallic nanoparticles such as silver, copper, and gold, which have established antimicrobial effects, can be incorporated into these systems. Additionally, antibiotics like gentamicin and vancomycin, as well as natural plant compounds such as thymol, can also be used41,42. EPD-deposited CS/HAp systems containing an antimicrobial agent are less frequently reported in the literature.

The novelty of this study lies in the formulation and use of an ethanol-based suspension with acetic acid for the EPD of composite coatings composed of CS, nanoHAp, and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on commercially pure titanium. AgNPs were introduced into the CS/nanoHAp composite to impart potential antibacterial functionality, aiming to reduce the risk of implant-associated infections while maintaining the bioactive and osteoconductive properties of HAp. The use of ethanol as the main liquid medium significantly reduced the agglomeration of AgNPs, improving their dispersion stability in the suspension and enabling more homogeneous coating formation. While CS and HAp composites have been extensively studied, the application of nano-sized HAp, which better mimics the natural bone mineral structure, remains relatively rare. Moreover, there are very few studies investigating the EPD of CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs composite coatings on titanium or its alloys, despite their promising potential for biomedical applications, especially in implantology. This work addresses this gap by systematically analyzing the influence of deposition parameters on coating properties, including microstructure, adhesion, corrosion resistance, bioactivity, wettability, and silver release to SBF.

Materials and methods

Substrate preparations

Samples of grade 2 titanium (chemical composition is given in Table 1, provided by the manufacturer in the material certificate, EkspressStal, Poland) were cut from a bar into discs measuring 20 mm in diameter and 5 mm in thickness. These samples were then wet-grinded using an ATM GmbH grinder-polisher (Germany) until achieving a final grit of #800. After grinding, the samples were degreased and cleaned in an ultrasonic cleaner (MKD Ultrasonic, Poland) by immersing them in isopropanol (99.9%, POCH, Poland) and distilled water for 5 min each. Finally, the samples were dried with compressed air, and copper wires were attached to their incised sides.

Preparation of suspensions for coating deposition

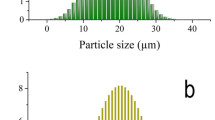

To prepare the suspension, a two-step process was utilized16involving the preparation of CS suspensions and mixtures of AgNPs with nanoHAp. First, for the chitosan suspension, 0.1 g of high-purity chitosan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, purity > 99%, HMW) was dissolved in 20 mL of 1% acetic acid (Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland, purity 99.5%). The chitosan was accurately measured using a laboratory balance (Ohaus, Poland). The resulting suspension was placed on a magnetic stirrer (Dragon Lab MS-H-Pro+, Schiltigheim, France) at room temperature and stirred continuously for 3 h at a speed of 400 rpm. In the second step, 0.005 g of AgNPs (Hongwu International Group Ltd, China, average particle size 30 nm) and 0.1 g of nanoHAp (MKnano, Canada, particle size 20 nm, purity 99.8%) were measured using the same laboratory balance and dispersed in 80 mL of ethanol. This mixture was then subjected to alternating mixing using an ultrasonic cleaner and a magnetic stirrer for a total duration of one hour. The mixing method was changed every 15 min to ensure proper dispersion of the components in the suspension. Next, the two suspensions were combined by slowly adding the acetic acid suspension to the ethanol suspension using an automatic pipette (Autoclavable, Poland). During this process, the ethanol suspension was stirred on a magnetic stirrer, with the stirring speed gradually increased to 1000 rpm to prevent particle sedimentation. After combining the two suspensions, the mixture was stirred for an additional 30 min. Finally, the pH of the prepared suspension was measured using a pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland).

Coatings deposition

The electrophoretic deposition process utilized a substrate made of grade 2 titanium, which served as the cathode. A platinum electrode was employed as the anode. The two electrodes were positioned parallel to each other in the suspension, maintaining a distance of approximately 10 mm. The power supply used for the process was the M10-TP-303E model from Shanghai MPC Corp., China. The process parameters, including deposition time and voltage, were established based on previous test trials as well as data from the literature16,43. The specific values of these parameters are detailed in Table 2. After the deposition process, the samples were extracted from the suspension and allowed to dry at room temperature for 24 h, and subjected to further testing.

Samples characterization

Microstructure, elemental, and phase composition

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique was utilized to analyze the surface of the coatings. SEM provides a detailed examination of the morphology and microstructure of samples, allowing for an assessment of their homogeneity and particle distribution. By capturing images at various magnifications, it is possible to identify potential defects and evaluate the surface structure of the coatings. Observations were conducted using a scanning microscope (Tescan Vega G4, Czech Republic), equipped with a secondary electron detector (SED), operating at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. Before imaging, the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold, 10 nm in thickness. This coating process was performed through magnetron sputtering (DC, EM SCD 500, Leica, Wetzlar, Austria) in an inert argon atmosphere (Argon, Air Products, Warsaw, Poland, 99.999%).

For the qualitative analysis of the chemical composition of the samples, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was employed. Measurements were conducted using an EDX system (Oxford Instruments, UK), which was integrated with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) operating at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV. The EDX spectra obtained facilitated a detailed examination of the chemical composition of the Ti grade 2 reference sample as well as the coated samples prepared using various electrophoretic deposition parameters.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Philips X’Pert Pro diffractometer (Netherlands) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm), operating at 30 kV and 50 mA. The diffraction patterns were collected in Bragg–Brentano geometry over a 2θ range of 10° to 90°, with a step size of 0.02°. A silicon standard was employed to evaluate and correct for instrumental broadening effects.

Surface roughness measurements

Surface topography was examined with a 3D optical profilometer based on confocal microscopy (Sensofar S Neox, Sensofar Metrology, Terrassa, Spain) using a Nikon EPI 20× objective. Analysis was performed with SensoSCAN S Neox 7.7 software on three randomly selected areas per sample, each measuring 1.33 × 1.68 mm. Roughness parameters (Sa – arithmetic mean height, Sq –root mean square height, Sp –maximum peak height, Sv –maximum pit depth, Sz – maximum height) were calculated in compliance with the ISO 25,178 standard.

Molecular structure testing

The attenuated total reflection - Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) technique was employed to analyze the types of chemical bonds formed between CS, nanoHAp, and AgNPs. The study utilized a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Frontier, Waltham, United States) and was conducted over a wavelength range of 550 cm⁻¹ to 4000 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 2 cm−1.

Coating thickness measurements

The thickness of the coatings was measured using a device from Helmut Fischer GmbH, which has a measurement error of 1 μm. Before taking measurements, the device was calibrated (on a grade 2 titanium reference sample after grinding) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations to ensure accurate results. For each sample, fifteen independent measurements were taken by applying the device’s sensor to various locations on the sample surface. From the data collected for each sample, the average coating thickness and standard deviation were calculated.

Wettability studies

The wettability angle was measured using a goniometer (Attention Theta Life, Biolin Scientific, Espoo, Finland) via the falling drop method at room temperature. A drop of approximately 2 µL of distilled water was placed on the surface of the samples. Measurements were taken for 10 s after the drop was applied. For each series of samples, produced under different deposition parameters, five measurements were recorded. The mean value of the wettability angle and the standard deviation were calculated for each analyzed series.

Corrosion studies

The corrosion resistance test was conducted on Ti grade 2 substrates and coated samples (placed in a holder exposing 1 cm² of surface area), which were immersed in a simulated body fluid (SBF) prepared according to PN-EN ISO 10993-15. The composition of the solution included the following substances: 7.996 g of NaCl, 0.35 g of NaHCO3, 0.224 g of KCl, 0.228 g of K2HPO4∙3H2O, 0.305 g of MgCl2∙6H2O, 0.278 g of CaCl2, 0.071 g of Na2SO4, and 6.057 g of (CH2OH)3CNH2, all dissolved in 1 L of distilled water.

The tests were carried out using a potentiostat (Atlas 0531, Atlas Sollich, Rebiechowo, Poland) at a constant temperature of 37 °C. A three-electrode measuring system was employed, with the test sample serving as the working electrode, a calomel electrode used as the reference electrode, and a platinum electrode functioning as the counter-electrode.

In the first stage of testing, an hour-long open circuit potential (OCP) test was performed to analyze potential changes over time. Following this, polarization curves were measured in potentiodynamic mode, ranging from − 1.0 V to 1.0 V, with a potential change rate of 1 mV/s. Based on the obtained polarization curves, the corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (jcorr) were determined from Tafel extrapolation of the potentiodynamic polarization curves, using standard linear fitting on both anodic and cathodic branches near the linear region. For each type of sample, the test was performed in triplicate. The data collected during the tests were processed using AtlasLab software (Atlas-Sollich, Gdańsk, Poland).

Silver release study

To determine the rate of silver release from composite coatings, samples produced under various EPD parameters were immersed in 100 mL of SBF, which has the same chemical composition used for corrosion testing. These samples were placed in a heating chamber (Pol-Eco Apparatus, Poland) set to a temperature of 37 °C. The silver release was assessed after 1, 3, and 7 days of incubation. After each time interval, the same sample was removed from the solution and transferred to fresh SBF, with the recorded concentration of released silver being summed after each transfer.

Quantitative determination of silver in model solutions simulating human body fluids was carried out using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). All measurements were performed using an Agilent 5800 ICP-OES instrument under standard operating conditions. External calibration was carried out using a series of silver standard solutions in the concentration range of 0.01–1.00 mg/L prepared from a 1000 mg/L Ag stock solution in 2% HNO3 (Sigma Aldrich). This range ensured adequate sensitivity, linearity, and accurate quantification of silver in the tested samples. Emission was monitored at the analytical wavelength of 328.068 nm, which is specific for silver. The resulting calibration curve was used for quantitative analysis.

To minimize matrix effects and reduce potential spectral or non-spectral interferences, all samples were subjected to a tenfold (1:10) dilution before analysis. The diluted samples were then measured using the established calibration model.

To verify the accuracy of the method, the standard addition approach was applied. Each sample was spiked with a known amount of silver standard, corresponding to the concentration previously determined in the unspiked solution. Both unspiked and spiked samples were analyzed in duplicate. For each sample, the two replicate results were compared, and the arithmetic mean was used for further calculations. The differences between replicates were minimal, demonstrating excellent repeatability of the method, which was further confirmed by low relative standard deviation (RSD) values calculated from the replicate results. Silver recovery was subsequently determined to assess method accuracy and confirm the absence of significant matrix interferences.

All solutions were prepared using Type I deionized water produced by a Hydrolab HLP 10SP water purification system.

Coatings adhesion evaluation

The adhesion of the coatings to the titanium substrate was assessed using the tape test method, following the European standard EN ISO 2409. The testing procedure involved making incisions in the surface of the samples with an edge knife (Elcometer 107), creating a grid of cuts in two perpendicular directions. After the incisions were made, tape was applied to the sample and gently pressed onto the surface with a finger. After five minutes, the tape was peeled off at an angle of approximately 60 degrees. Each sample was evaluated based on the adhesion class template, considering the degree of coating detachment from the grid area of notches. Additionally, the surface of each sample was examined using a light microscope (BX51, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immersion acellular bioactivity test

The immersion test was conducted in the previously mentioned SBF. Both the reference sample (ground titanium substrate) and the coated samples were placed in separate containers filled with 50 mL of SBF solution. These containers were then placed in a laboratory hothouse (Pol-Eco Apparatus, Poland) for a duration of 14 days. The test was conducted at a temperature of 36.6 °C, which mimics conditions in the human body. After the immersion period, the samples underwent detailed surface analysis using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy. This analysis aimed to evaluate changes in the surface structure and chemical composition of the coatings.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the collected data was performed using OriginPro software (version 8.5.0 SR1, OriginLab Corporation). To assess the normality of the data distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test was utilized. All results are presented as means with standard deviations. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, with statistical significance established at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Microstructure and elemental composition of coatings

During the electrophoretic deposition of CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings, the composition of the suspension and the physicochemical properties of the individual components are crucial in determining the deposition mechanism. The proposed suspension resulted in a mildly acidic medium with an estimated pH of 3.6 ± 0.2. This acidic environment significantly influences the charge and behavior of the particles involved. In an acidic environment, the amino groups (–NH2) of chitosan become protonated to form –NH3+, giving the polymer a positive charge. As a result, chitosan remains well-dispersed due to electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged chains44. The point of zero charge of hydroxyapatite is around pH 7 to 8. In the acidic suspension (pH 3 to 4), nanoHAp particles acquire a positive surface charge due to the protonation of their phosphate and hydroxyl groups (–OH → –OH2+ and PO43− → HPO42−), as well as an increased contribution of Ca2+ ions at the particle surface, leading to a positive surface potential45. In turn, AgNPs, typically found in a non-stabilized powdered form, tend to form agglomerates. In the acidic and ethanolic medium, AgNPs can adsorb protons or acetic acid anions, potentially acquiring a slightly positive or neutral charge, or they may remain agglomerated and neutral46.

When an electric field is applied, the positively charged chitosan molecules and nanoHAp particles migrate toward the cathode (the titanium substrate). Some AgNPs may also move toward the cathode due to proton adsorption or remain dispersed as agglomerates. Upon reaching the cathode, these particles undergo various interactions that stabilize the coating. The electrostatic attraction between the positively charged chitosan and nanoHAp and the negatively charged cathode surface aids in initial adherence. Chitosan, being a high molecular weight polymer, forms an interconnected network that can trap nanoHAp and AgNPs, enhancing the uniformity of the film. Additionally, hydrogen bonding between the protonated amino groups of chitosan and the hydroxyl groups of nanoHAp further strengthens the composite structure30.

Electrochemical reactions may also occur at the cathode surface, particularly the reduction of protons to hydrogen gas (2 H+ + 2e− → H2↑). This local generation of hydrogen can increase the pH near the electrode, leading to partial deprotonation of chitosan, which may enhance cross-linking and improve the mechanical stability of the film14.

After deposition, the samples were dried at room temperature for 24 h. During this period, the evaporation of ethanol and water causes the coating to densify, while partial crystallization of the residual CS film may enhance its mechanical properties. The resulting coating is a composite layer characterized by electrostatic cohesion, hydrogen bonding, and physical entrapment, with potential biomedical applications, particularly in bone tissue engineering5,47.

Figure 1 presents the results of SEM imaging and macroscopic images of the ground titanium substrate as well as the CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings (right after deposition and after drying). The grade 2 titanium sample exhibited a characteristic linear structure resulting from the grinding process. The deposited coatings demonstrated a porous structure, which is beneficial for osteointegration. As the voltage increased and the deposition time was extended, the coatings became thicker and more heterogeneous, a phenomenon also observed in other studies48. Macroscopic analysis indicated that the parameters of the deposition process, such as voltage and time, significantly influenced the appearance and uniformity of the coatings. The formation of gas bubbles (hydrogen) at higher deposition voltages and longer times was attributed to the intensified water electrolysis process, resulting in a more developed coating structure6,49. When a higher voltage (30 V) is applied during EPD, a more intense formation of hydrogen gas bubbles at the cathode was observed. The increased voltage accelerates the reduction reaction, leading to a rapid evolution of hydrogen. As a result, the accumulation of gas bubbles can disrupt the uniformity of the coating by creating voids or defects. A characteristic phenomenon associated with higher voltage is the formation of raised areas or ‘hills’ at the edges of the deposited layer. This edge effect occurs because the electric field is typically stronger at the periphery of the cathode. Consequently, local intensification of hydrogen evolution leads to bubble formation and accumulation near the edges, causing uneven deposition and the formation of thicker, uneven regions in the final coating. These edge hills result from the combined effects of localized gas pressure and uneven particle distribution during the rapid bubble release50. To minimize this effect, controlling the applied voltage and deposition time is essential to ensure more uniform coating morphology. When the deposition time was increased to 5 min, bumps originating from H2 bubble formation were visible throughout the samples. The most uniform coating was achieved at the lowest voltage and the shortest deposition time. Under these conditions, the particles exhibited adequate mobility, facilitating uniform deposition of the material on the substrate. While agglomerates were present on the coatings, they were distributed uniformly. However, at higher voltages, larger agglomerates were observed, which could potentially compromise the quality of the coatings.

The EDX analysis (Figs. 1 and 2a) confirms the successful incorporation of CS, nanoHAp, and AgNPs into the composite coatings produced by EPD. The characteristic peaks of carbon, oxygen, calcium, and phosphorus are consistent with the expected presence of CS and nanoHAp, respectively. The presence of silver, although less pronounced, confirms the integration of metallic nanoparticles within the deposited layer. The AgNPs appear to be fairly evenly distributed in the biopolymer-ceramic matrix and contributed to a slightly more granular surface texture, which may enhance surface area. The presence of AgNPs modifies the suspension’s conductivity and electrophoretic mobility. This can subtly influence deposition kinetics, particle co‑migration, and final coating microstructure. The reduction in titanium peak intensity at higher deposition parameters can be attributed to the increased thickness of the composite layer. As the thickness grows, the signal from the underlying titanium substrate becomes attenuated, while the signals from the coating components intensify. This trend highlights the efficient deposition of the composite material when higher voltage or longer deposition times are applied. The presence of silicon in the substrate spectrum should not be misinterpreted as contamination, as it results from the surface preparation procedure using SiC paper. Additionally, the appearance of gold peaks in all spectra is related to the sputtering process performed before SEM analysis, which is a standard practice to enhance conductivity and image quality. The successful detection of the intended coating components, combined with the absence of unexpected elements, indicates that the EPD process was well-controlled and did not introduce contaminants.

A high-magnification SEM micrograph of the coating deposited at 30 V for 5 min (Fig. 2b) reveals the characteristic needle-like morphology of nanoHAp crystals embedded within the chitosan matrix. The dense arrangement of these elongated crystals is consistent with the increased deposition yield observed under high-voltage, long-time EPD conditions. Due to the similar nanoscale dimensions and morphology of AgNPs and HAp particles, as well as the presence of the polymeric matrix, individual silver nanoparticles could not be distinguished in SEM images; however, their presence was confirmed by EDS elemental mapping. Cracks visible in high-magnification SEM images of the coatings result from the fracture of the sputtered gold layer deposited before SEM observation, caused by localized heating and stress under the focused electron beam. This phenomenon has been observed previously in our work and is well-known when imaging polymer-containing or composite coatings requiring conductive metal coating for charge dissipation51.

Figure 2c presents the XRD patterns of the uncoated titanium substrate and CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings deposited under different EPD parameters. The diffraction pattern of the titanium substrate shows characteristic peaks at 2θ ≈ 35.1°, 38.4°, 40.2°, 53.0°, 63.1°, 70.7°, 76.1°, and 77.3°, corresponding to the hexagonal close-packed Ti phase (JCPDS 44-1294). In the coated samples, additional peaks appear at approximately 2θ ≈ 25.9°, 31.8°, 32.9°, 34.0°, 39.8°, 46.7°, 49.5°, and 53.1°, which can be assigned to the (002), (211), (112), (300), (310), (222), (213), and (004) reflections of crystalline hydroxyapatite (HAp, JCPDS 09-0432). The relative intensity of HAp peaks increases with higher EPD voltage and longer deposition time, indicating a greater amount of HAp in the coating due to higher deposition yield under these conditions. In particular, the (211) peak at ~ 31.8° and the (112) peak at ~ 32.9° become more pronounced for coatings produced at 30 V compared to those at 10 V.

Although silver nanoparticles were incorporated into the coatings, their characteristic peaks are not clearly visible in the diffractograms. This is likely due to their low concentration (0.005 g/100 mL), nanoscale size (ca. 30 nm), and the fact that their main diffraction peaks overlap with intense reflections from Ti and HAp, making unambiguous identification difficult.

Roughness of the tested surfaces

Surface roughness measurements (Fig. 3; Table 3) demonstrated a systematic increase in Sa, Sq, Sp, Sv, and Sz values with rising EPD voltage and deposition time. The uncoated titanium substrate exhibited the lowest Sa (0.26 μm), while the highest value (1.30 μm) was recorded for the coating deposited at 30 V for 5 min. This trend was consistent across other roughness parameters, indicating the formation of progressively more textured surfaces under higher deposition rates. These quantitative findings align well with SEM observations, where coatings produced at low voltages and shorter times (e.g., 10 V, 3 min) displayed a relatively smooth and compact morphology, while those obtained at 30 V showed coarser, more irregular surfaces with visible agglomerates. The agreement between profilometry and SEM confirms that EPD parameters directly influence coating microstructure and surface topography. In addition to roughness, isotropy of the surfaces was assessed to evaluate the uniformity of the microstructure. The uncoated titanium surface exhibited the lowest isotropy value, which is characteristic of substrates after grinding. After the coating deposition, the isotropy value was increased. As the deposition voltage and time increased, the isotropy values also increased, meaning that the surface features of the coatings were more evenly distributed in all directions. This result implies that under higher voltages, more homogeneous coatings with a less directional structure were formed, improving the overall surface uniformity. In contrast, lower voltages (e.g., 10 V) resulted in coatings with lower isotropy, indicating the presence of more directional or heterogeneous structures, likely due to less stable deposition and particle agglomeration. These findings suggest that controlling EPD parameters such as voltage and deposition time can effectively modulate both surface roughness and isotropy, which may have implications for the coatings’ functional properties, such as corrosion resistance and bioactivity.

Molecular structure and thickness of the coatings

Figure 4a shows the FTIR spectra obtained for CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings deposited by EPD under various conditions. The spectra reveal distinct absorption bands characteristic of CS, nanoHAp, and minor contributions from AgNPs. The 3500–3200 cm−1 region corresponds to the stretching vibrations of –OH and –NH groups52. The intensity of this band decreases with increasing voltage and deposition time, indicating possible changes in the hydrogen bonding network due to the denser and thicker coating formation at higher parameters. The 2870 cm−1 band is attributed to the symmetric stretching of –CH₂ groups, typical of the CS backbone. 1641 cm−1 and 1550–1380 cm−1 peaks are associated with the amide I (C = O stretching) and amide II (N–H bending) vibrations of CS. The relative intensity of these bands increases at higher deposition parameters, suggesting an increase in chitosan content or improved integration within the composite layer. Also, the 1415–1380 cm−1 band represents the bending vibrations of CH₃ groups from chitosan and possible carbonate groups from nanoHAp53. Peaks at 1151 cm−1 and 1013 cm−1 correspond to the C–O–C stretching vibrations in chitosan and P–O stretching vibrations in nanoHAp, respectively. Peaks confirming the presence of phosphate groups were also visible at 885, 602, and 560 cm−154. No significant shifts in these peaks indicate that the deposition process does not significantly alter the crystalline structure of nanoHAp. The weak intensity of Ag-specific bands may result from the relatively low content of silver nanoparticles in the coating or their embedding within the organic-inorganic matrix, which reduces their visibility in the FTIR spectrum. Overall, the FTIR spectra validate the successful incorporation of both organic (CS) and inorganic (nanoHAp) phases within the coating. The effect of higher voltage and prolonged deposition time is associated with increased coating thickness and material density, reflecting the efficient EPD process5.

(a) FTIR spectra obtained for CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings, (b) coatings thickness measurements results, (c) measured contact angle values for all investigated samples, (d) images of distilled water droplets on tested surfaces, results of corrosion studies: (e) OCP curves, (f) potentiodynamic polarization curves, (g) results of silver release studies, (h) schematic representation of possible silver ion release, and (i) images of scratches made on tested surfaces with coatings after tape test (scale bar = 200 μm); * significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 4b shows the average coating thickness with standard deviations for different EPD parameters. The thickness of the composite coatings increases with both the applied voltage and deposition time. The lowest thickness was observed for coatings formed at 10 V for 3 min, while the highest was for coatings obtained at 30 V for 5 min. This trend reflects the influence of the electric field strength on particle mobility and deposition rate. Higher voltage increases the electrophoretic mobility of the positively charged CS and nanoHAp particles, leading to a faster and more efficient build-up of the coating layer. In turn, longer deposition time allows for continuous accumulation of particles on the cathode, resulting in a thicker composite layer47.

Coatings’ wettability

The contact angle measurement provides insight into the surface wettability, which is closely related to biological interactions such as protein adsorption, cell adhesion, and proliferation. It also reflects the surface energy and uniformity of the coating, which can influence both corrosion resistance and bioactivity55. The results of wettability measurements for CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings deposited at different EPD parameters are presented in Fig. 4c and d. The contact angle measurements were compared with the uncoated titanium substrate (grade 2). The images (Fig. 4d) display the droplet profiles on the coated and uncoated surfaces, while the graph (Fig. 4c) shows the average contact angle values with standard deviations for all samples. The uncoated titanium substrate exhibited a relatively low contact angle, indicating hydrophilic behavior. After coating, the contact angle increased for all deposition conditions, suggesting that the presence of the composite layer increased the surface hydrophobicity. The most significant increase in the contact angle was observed for coatings deposited at 30 V for 5 min. This indicates that higher voltage and longer deposition time lead to a denser and more compact coating structure, reducing surface wettability. It can be expected that surfaces with higher roughness parameters might exhibit larger apparent contact angles. This effect can be explained by the fact that a more developed micro/nano-scale topography can trap air pockets between the liquid droplet and the surface, thereby reducing the effective wetted area and increasing the measured contact angle. Such behavior is consistent with the Cassie–Baxter wetting model, where surface asperities influence the macroscopic wettability independently of the intrinsic surface chemistry56. The increase in hydrophobicity with higher deposition parameters can also be attributed to the more substantial presence of CS within the coating, which inherently exhibits hydrophobic characteristics due to its polymeric nature. This effect has been noted before (contact angle of CS-coated surfaces in the range of 76.4 ± 5.1°)57. It has been reported that coating the titanium surface with CS reduced titanium wettability but enhanced protein adsorption and cell adhesion. It may be beneficial for improving implant osteointegration. Additionally, the denser and thicker coating structure, formed at higher voltage, provides fewer accessible hydrophilic sites (e.g., hydroxyl groups from nanoHAp), thus possibly reducing the overall wettability.

Corrosion test results

Figure 4e shows the open circuit potential (OCP) variation over time for the investigated samples immersed in SBF at 37 °C. After approximately one hour, OCP stabilization was observed for all tested samples. The coatings exhibited OCP stabilization within the range of 0.10 V to around 0.15 V, while the reference titanium substrate stabilized at approximately − 0.10 V. The higher OCP values observed for coatings deposited at higher voltage and longer deposition time can be attributed to increased coating thickness. An elevated OCP value generally indicates improved corrosion resistance, suggesting that thicker coatings provide better protection. Previous studies also confirm an increase in OCP values for coatings containing chitosan and hydroxyapatite58,59.

The potentiodynamic polarization curves obtained for all samples in the SBF solution are presented in Fig. 4f. The corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (jcorr) values, derived from Tafel extrapolation, are summarized in Table 4. The cathodic branches of the polarization curves correspond to hydrogen evolution, while the anodic branches represent the dissolution process of the coating and substrate. Coated samples exhibited higher Ecorr values shifted towards the positive direction, indicating enhanced corrosion resistance compared to the uncoated titanium substrate. In some cases, composite coatings containing metallic nanoparticles demonstrated lower corrosion current densities (jcorr), reflecting reduced corrosion rates60. However, an upward trend in jcorr values was observed for coatings deposited at higher voltage settings, which may be associated with increased heterogeneity in the coatings.

The increased heterogeneity of coatings obtained at higher voltages can lead to the formation of so-called corrosion channels, reducing corrosion resistance despite the increased coating thickness. These channels may act as pathways for ion diffusion, compromising the protective function of the coating. The increased porosity and microstructural defects resulting from rapid particle movement and deposition under high voltage contribute to these heterogeneities60,61. Despite the potential drawbacks of higher voltage, the addition of AgNPs can still positively influence the coating’s corrosion resistance. Silver nanoparticles can fill the pores within the coating structure, enhancing the compactness and reducing the penetration of corrosive agents. The thicker coatings, while prone to heterogeneity, may still act as a diffusion barrier, hindering ion transport and reducing the substrate’s exposure to the corrosive environment.

The results indicate that optimizing voltage and deposition time is crucial to balancing coating thickness, structural homogeneity, and corrosion resistance. Coatings deposited at lower voltage and shorter times generally show improved adhesion and lower corrosion rates, while higher voltage conditions may introduce defects that can diminish corrosion protection despite increased thickness.

Surface wettability, although to a lesser extent, can also affect corrosion resistance, as more hydrophobic surfaces can limit the impact of corrosive agents on the substrate, reducing the intensity of corrosion reactions. In addition, hydrophobic coatings, which have less contact with water, can increase protection by preventing electrolyte penetration into the surface, thereby improving the durability of coatings in corrosive environments. However, no clear trend between wettability and corrosion resistance of the tested surfaces was observed in these studies.

Silver release results

The release of silver from the CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings into the SBF solution was measured after 1, 3, and 7 days of immersion. The results of these tests are presented in Fig. 4g. The results indicate that the release of silver ions increases over time for all tested samples, with the highest concentration observed after 7 days of immersion. The coating deposited at 30 V for 5 min exhibited the most significant silver release, while the coating prepared at 10 V for 3 min showed the lowest release rates. Coatings deposited at higher voltages (30 V) and longer deposition times (5 min) generally demonstrated increased silver ion release. This can be attributed to the thicker and more porous structure of these coatings, which facilitates the diffusion of ions from the embedded silver nanoparticles into the surrounding medium. The higher voltage accelerates particle movement during EPD, resulting in a less compact and more heterogeneous coating, which may create diffusion pathways for silver ions. In contrast, coatings produced at lower voltage and shorter time (10 V, 3 min) exhibit a slower and more controlled release profile. These coatings are typically thinner and more homogeneous, which reduces the rate of ion migration through the coating matrix. The gradual increase in Ag+ concentration over time in these samples suggests a more sustained and controlled ion release, which could be beneficial for applications requiring long-term antibacterial effects.

The release of silver ions from CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs composite coatings into the SBF appears to be governed by a combination of diffusion-controlled and matrix degradation-assisted mechanisms. Initially, silver ions are released from the surface and near-surface regions of the coatings, where AgNPs are more accessible to the surrounding medium. Over time, continuous exposure to SBF leads to the gradual degradation or swelling of the CS matrix, especially in coatings with higher porosity and lower structural integrity. This swelling enlarges the diffusion channels, particularly in more porous or loosely packed coatings (e.g., those deposited at higher voltages), facilitating further migration of Ag⁺ ions from deeper within the coating. Over prolonged immersion, partial degradation of the CS matrix occurs, especially in physiological conditions, which exposes embedded AgNPs and accelerates their oxidation and subsequent ion release. In denser coatings (e.g., those deposited at lower voltages and shorter times), probably, the diffusion of silver ions is more restricted due to limited pore size and lower porosity. As a result, these coatings exhibit a more gradual and sustained release pattern, which can be advantageous for long-term antimicrobial performance51,62,63,64. A schematic representation of the possible mechanisms of silver release from the fabricated composite coatings is shown in Fig. 4h.

The observed variation in silver ion release highlights the impact of deposition parameters on the microstructure and density of the composite coatings. Optimizing these parameters is crucial for achieving the desired balance between antibacterial efficacy and controlled ion release, minimizing the risk of cytotoxicity while maintaining effective antimicrobial action.

Coatings adhesion

The adhesion of the CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings was evaluated using the tape test following the EN ISO 2409 standard. The results are presented in Fig. 4i, while the adhesion classes of the coatings were assessed based on the reference from the standard. The coating deposited at the lowest voltage and shortest time (10 V, 3 min) exhibited minimal material loss at the edges of the cut grid. These detachments were limited to small areas along the cutting lines, with the detached area not exceeding 5%, corresponding to adhesion class (1) In the case of the coating deposited at 10 V for 5 min, more significant damage was observed, especially along the edges of the incisions. The detached area ranged from 5 to 15%, placing this coating in adhesion class (2) For the coating deposited at 30 V for 3 min, clear fragments were observed to detach both along the edges of the grid and in larger sections between cuts. The detachment area reached up to 35%, corresponding to adhesion class (3) The most extensive material detachment was noted for the coating deposited at 30 V for 5 min. A substantial portion of the coating was removed, exposing more than 35% of the substrate surface. This coating was classified as adhesion class 4.

The observed decrease in adhesion with increasing voltage and deposition time can be attributed to several factors related to the coating’s microstructure and surface properties. Lower voltage and shorter deposition times result in thinner and more compact coatings, which tend to have better adhesion to the titanium substrate. The lower thickness reduces internal stresses and minimizes the formation of defects within the coating, leading to stronger bonding with the substrate. In contrast, coatings formed at higher voltage and longer deposition times tend to be thicker and more porous, resulting from the rapid movement and accumulation of particles during the EPD process6. The increased thickness enhances the likelihood of forming microcracks and voids within the coating structure, which reduces mechanical integrity. Moreover, the rapid deposition at higher voltage can cause uneven particle distribution, leading to localized stress concentrations that weaken the adhesion. Additionally, the increased hydrogen evolution at higher voltages can lead to gas bubble formation at the substrate-coating interface, creating voids and weakening the bond. These gas-induced defects, combined with the increased coating thickness, contribute to the reduced adhesion observed at higher deposition parameters. The rougher surface of thicker coatings does not necessarily enhance adhesion, as previously suggested65. Although increased surface roughness can theoretically improve mechanical interlocking, the presence of defects and cracks within a thick, rapidly deposited layer outweighs this potential benefit. Consequently, the best adhesion was achieved with coatings deposited at the lower voltage (10 V) and shorter time (3 min), where a balanced, compact, and defect-free structure was obtained.

The presence of AgNPs at low concentration (0.005 g/100 mL) did not negatively affect coating adhesion. This may be due to their uniform dispersion in the chitosan matrix and their small size, which does not disrupt coating continuity. In some cases, they may even enhance mechanical interlocking due to slight increases in surface roughness.

Surface bioactivity test results

Figure 5 presents SEM images and the results of the chemical composition analysis obtained through EDS of the titanium substrate and CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings deposited at various EPD parameters after 14 days of incubation in Kokubo’s simulated body fluid. Changes in morphology and the presence of crystallized salts were observed on both the titanium surface and the electrophoretically deposited coatings, indicating mineralization processes. The most pronounced crystallization occurred on coatings deposited at higher voltages and longer times. The precipitation of calcium phosphate crystals was confirmed by the presence of calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) on the coating surfaces. However, some of the detected Ca and P could also be attributed to the presence of nanoHAp within the coatings. This finding aligns with literature reports emphasizing the high bioactivity of hydroxyapatite-based coatings, which promote osteointegration due to their structural similarity to the mineral component of bone.

The enhanced surface bioactivity of the CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings can be attributed, in part, to the presence of functional surface groups inherent to hydroxyapatite, such as hydroxyl (–OH) and phosphate (PO43−) moieties. These groups are known to act as active nucleation sites for calcium phosphate precipitation during immersion in SBF, thereby facilitating the growth of bone-like apatite layers. In our study, SEM observations after SBF exposure revealed mineral deposition on the coating surfaces, which is consistent with the interaction of these functional groups with Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻ ions in the solution. The availability and accessibility of these groups depend not only on the HA content but also on the microstructure and surface roughness of the coating, which are influenced by the EPD parameters19.

The increased mineralization observed on coatings deposited at higher voltage and longer times may be associated with the increased coating thickness and the availability of mineralization nucleation sites. The presence of hydroxyapatite within the coating structure likely facilitates the formation of calcium phosphate compounds on the surface when exposed to an SBF environment. On the other hand, coatings deposited at lower EPD parameters exhibited less precipitation of Ca and P, likely due to their reduced thickness and, consequently, lower content of mineralizing components. The titanium substrate itself displayed low bioactivity, characterized mainly by the crystallization of sodium chloride (NaCl), which is typical for pure titanium surfaces without additional bioactive modification. The presence of sodium (Na) and chlorine (Cl) on the sample surfaces is likely due to the precipitation of NaCl from the SBF solution. Rapid water evaporation from the surface could lead to local supersaturation, resulting in NaCl crystallization, a phenomenon commonly observed during immersion tests65,66.

The results suggest that coatings deposited at higher voltage and longer deposition times demonstrate enhanced bioactivity due to increased mineral content and hydroxyapatite presence. This improved bioactivity is essential for promoting osseointegration when the coatings are deposited on titanium-based implants.

Conclusions

The conducted research confirmed the feasibility of fabricating composite coatings based on CS and nanoHAp with the addition of AgNPs on titanium substrates using a one-step EPD method. The process parameters, including voltage and deposition time, significantly influenced the properties of the coatings.

The most homogeneous coatings with good adhesion to the substrate were obtained at 10 V for 3 min, achieving adhesion class 1 (EN ISO 2409). Higher voltage and longer deposition time produced thicker coatings, with a maximum thickness of ~ 7 μm (30 V, 5 min), but also led to gas bubble formation due to water electrolysis, which negatively affected adhesion. SEM and roughness analysis showed that coatings deposited at higher parameters exhibited a more developed surface morphology, with average surface roughness (Sa) increasing from ~ 0.5 μm (10 V, 3 min) to 1.3 μm (30 V, 5 min). EDS confirmed the expected chemical composition, and FTIR analysis demonstrated the incorporation of biomaterials into the chemical structure of the coatings. All coatings displayed corrosion resistance, with the open circuit potential (OCP) shifting positively up to + 0.15 V vs. SCE compared with the uncoated substrate. Wettability tests indicated hydrophilic behavior, with a contact angle of ~ 80°.Immersion tests in SBF confirmed the bioactive potential of the coatings, as evidenced by calcium phosphate precipitation. The release profile of silver ions revealed a more controlled and sustained release at low deposition parameters (0.9 mg/L after 7 days, 10 V, 3 min) and a faster release at high deposition parameters (1.8 mg/L after 7 days, 30 V, 5 min) due to increased coating porosity.

In summary, the optimized conditions (10 V, 3 min) provided the best balance between coating adhesion, corrosion resistance, and controlled silver release. The one-step ethanol-based EPD process enabled fabrication of multicomponent CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs coatings with promising potential for implantology applications, particularly in reducing postoperative infections while supporting osseointegration. Future biological studies, including cytotoxicity and antibacterial tests, are necessary to validate these findings prior to clinical translation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Durgalakshmi, D., Rakkesh, R. A. & Balakumar, S. Stacked Bioglass/TiO2 nanocoatings on titanium substrate for enhanced osseointegration and its electrochemical corrosion studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 349, 561–569 (2015).

Prasad, S., Ehrensberger, M., Gibson, M. P., Kim, H. & Monaco, E. A. Biomaterial properties of titanium in dentistry. J. Oral Biosci. 57, 192–199 (2015).

Nnamchi, P. S., Obayi, C. S., Todd, I. & Rainforth, M. W. Mechanical and electrochemical characterisation of new Ti–Mo–Nb–Zr alloys for biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 60, 68–77 (2016).

Ferraris, S. & Spriano, S. Antibacterial titanium surfaces for medical implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 61, 965–978 (2016).

Besra, L. & Liu, M. A review on fundamentals and applications of electrophoretic deposition (EPD). Prog Mater. Sci. 52, 1–61 (2007).

Corni, I., Ryan, M. P. & Boccaccini, A. R. Electrophoretic deposition: from traditional ceramics to nanotechnology. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 28, 1353–1367 (2008).

Liu, C. F., Huang, C. P., Hu, C. C., Juang, Y. & Huang, C. Photoelectrochemical degradation of dye wastewater on TiO2-coated titanium electrode prepared by electrophoretic deposition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 165, 145–153 (2016).

Urra Sanchez, O. et al. Cathodic electrophoretic deposition (EPD) of two-dimensional colloidal Ni(OH)2 and NiO nanosheets on carbon fibers (CF) for binder-free structural solid-state hybrid supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage. 81, 110373 (2024).

Seuss, S. & Boccaccini, A. R. Electrophoretic deposition of biological macromolecules, drugs, and cells. Biomacromolecules 14, 3355–3369 (2013).

Molaei, A., Amadeh, A., Yari, M. & Reza Afshar, M. Structure, apatite inducing ability, and corrosion behavior of chitosan/halloysite nanotube coatings prepared by electrophoretic deposition on titanium substrate. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 59, 740–747 (2016).

Singh, S., Singh, G., Bala, N. & Aggarwal, K. Characterization and Preparation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles loaded bioglass-chitosan nanocomposite coating on Mg alloy and in vitro bioactivity assessment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 151, 519–528 (2020).

Singh, S., Singh, G. & Bala, N. Analysis of in vitro corrosion behavior and hemocompatibility of electrophoretically deposited bioglass–chitosan–iron oxide coating for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Res. 35, 1749–1761 (2020).

Nawaz, Q. et al. Multifunctional stratified composite coatings by electrophoretic deposition and RF co-sputtering for orthopaedic implants. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 7920–7935 (2021).

Neirinck, B., Fransaer, J., Van der Biest, O. & Vleugels, J. Aqueous electrophoretic deposition in asymmetric AC electric fields (AC–EPD). Electrochem. Commun. 11, 57–60 (2009).

Mahmoodi, S., Sorkhi, L., Farrokhi-Rad, M. & Shahrabi, T. Electrophoretic deposition of hydroxyapatite–chitosan nanocomposite coatings in different alcohols. Surf. Coat. Technol. 216, 106–114 (2013).

Pawłowski, Ł., Akhtar, M. A., Zieliński, A. & Boccaccini, A. R. Electrophoretic deposition and characterization of composite chitosan/eudragit E 100 or poly(4-vinylpyridine)/mesoporous bioactive glass nanoparticles coatings on pre-treated titanium for implant applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 479, 130542 (2024).

Farrokhi-Rad, M., Fateh, A. & Shahrabi, T. Effect of pH on the electrophoretic deposition of Chitosan in different alcoholic solutions. Surf. Interfaces. 12, 145–150 (2018).

Aktan, M. K. et al. Alternating current electrophoretic deposition of maleic anhydride modified Chitosan on Ti implants to combat biofilm formation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 493, 131182 (2024).

Topuz, M., Karatas, E., Ruzgar, D., Akinay, Y. & Cetin, T. Ti3C2Tx mxene/halloysite nanotube functionalized films for antibacterial applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2025.2522746 (2025).

de Oliveira, W. F. et al. Pharmaceutical applications of Chitosan on medical implants: A viable alternative for construction of new biomaterials? Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 7, 100407 (2024).

Tian, M. et al. Electrophoretic deposition of Tetracycline loaded bioactive glasses/chitosan as antibacterial and bioactive composite coatings on magnesium alloys. Prog Org. Coat. 184, 107841 (2023).

Govindharajulu, J. P. et al. Chitosan-recombinamer layer-by-layer coatings for multifunctional implants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1–16 (2017).

Mohan, L., Durgalakshmi, D., Geetha, M., Narayanan, S., Asokamani, R. & T. S. N. & Electrophoretic deposition of nanocomposite (HAp + TiO 2) on titanium alloy for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 38, 3435–3443 (2012).

Topuz, M., Akinay, Y., Karatas, E. & Cetin, T. Ti3C2Tx MXene-functionalized hydroxyapatite/halloysite nanotube filled poly– (lactic acid) coatings on magnesium: in vitro and antibacterial applications. J. Magnes Alloy. 12, 3758–3771 (2024).

Zhong, Z., Qin, J. & Ma, J. Electrophoretic deposition of biomimetic zinc substituted hydroxyapatite coatings with Chitosan and carbon nanotubes on titanium. Ceram. Int. 41, 8878–8884 (2015).

Stevanović, M. et al. The chitosan-based bioactive composite coating on titanium. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 4461–4474 (2021).

Karimi, N., Kharaziha, M. & Raeissi, K. Electrophoretic deposition of Chitosan reinforced graphene oxide-hydroxyapatite on the anodized titanium to improve biological and electrochemical characteristics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 98, 140–152 (2019).

Drevet, R. et al. Electrophoretic deposition (EPD) of nano-hydroxyapatite coatings with improved mechanical properties on prosthetic Ti6Al4V substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 301, 94–99 (2016).

Pawlik, A. et al. Fabrication and characterization of electrophoretically deposited chitosan-hydroxyapatite composite coatings on anodic titanium dioxide layers. Electrochim. Acta. 307, 465–473 (2019).

Gaafar, M. S., Yakout, S. M., Barakat, Y. F. & Sharmoukh, W. Electrophoretic deposition of hydroxyapatite/chitosan nanocomposites: the effect of dispersing agents on the coating properties. RSC Adv. 12, 27564–27581 (2022).

Jugowiec, D. et al. Influence of the electrophoretic deposition route on the microstructure and properties of nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan coatings on the Ti-13Nb-13Zr alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 324, 64–79 (2017).

Saadati, A., Khiarak, B. N., Zahraei, A. A., Nourbakhsh, A. & Mohammadzadeh, H. Electrochemical characterization of electrophoretically deposited hydroxyapatite/chitosan/graphene oxide composite coating on Mg substrate. Surf. Interfaces. 25, 101290 (2021).

Đošić, M. et al. In vitro investigation of electrophoretically deposited bioactive hydroxyapatite/chitosan coatings reinforced by graphene. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 47, 336–347 (2017).

Singh, S., Singh, G. & Bala, N. Electrophoretic deposition of Fe3O4 nanoparticles incorporated hydroxyapatite-bioglass-chitosan nanocomposite coating on AZ91 Mg alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 26, 101870 (2021).

Molaei, A., Yari, M. & Afshar, M. R. Modification of electrophoretic deposition of chitosan–bioactive glass–hydroxyapatite nanocomposite coatings for orthopedic applications by changing voltage and deposition time. Ceram. Int. 41, 14537–14544 (2015).

Farrokhi-Rad, M., Shahrabi, T., Mahmoodi, S. & Khanmohammadi, S. Electrophoretic deposition of hydroxyapatite-chitosan-CNTs nanocomposite coatings. Ceram. Int. 43, 4663–4669 (2017).

Batmanghelich, F. & Ghorbani, M. Effect of pH and carbon nanotube content on the corrosion behavior of electrophoretically deposited chitosan-hydroxyapatite-carbon nanotube composite coatings. Ceram. Int. 39, 5393–5402 (2013).

Singh, S., Singh, G. & Bala, N. Characterization, electrochemical behavior and in vitro hemocompatibility of hydroxyapatite-bioglass-iron oxide-chitosan composite coating by electrophoretic deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 405, 126564 (2021).

Tozar, A. & Karahan, İ. H. A comprehensive study on electrophoretic deposition of a novel type of collagen and hexagonal Boron nitride reinforced hydroxyapatite/chitosan biocomposite coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 452, 322–336 (2018).

Sun, F., Pang, X. & Zhitomirsky, I. Electrophoretic deposition of composite hydroxyapatite–chitosan–heparin coatings. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 209, 1597–1606 (2009).

Wang, B., Peng, K., Xu, P., Jing, W. & Zhang, Y. Vancomycin-loaded porous chitosan-pectin-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite coating on Ti6Al4V towards enhancing prosthesis antiinfection performance. Mater. Lett. 351, 135080 (2023).

Akshaya, S., Rowlo, P. K., Dukle, A. & Nathanael, A. J. Antibacterial coatings for titanium implants: recent trends and future perspectives. Antibiotics 11, 1719 (2022).

Bartmański, M. et al. Electrophoretic deposition and characteristics of Chitosan–Nanosilver composite coatings on a nanotubular TiO2 layer. Coatings 10, 245 (2020).

Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: properties and applications. Prog Polym. Sci. 31, 603–632 (2006).

Harding, I. S., Rashid, N. & Hing, K. A. Surface charge and the effect of excess calcium ions on the hydroxyapatite surface. Biomaterials 26, 6818–6826 (2005).

Fernando, I. & Zhou, Y. Impact of pH on the stability, dissolution and aggregation kinetics of silver nanoparticles. Chemosphere 216, 297–305 (2019).

Amrollahi, P., Krasinski, J. S., Vaidyanathan, R., Tayebi, L. & Vashaee, D. Electrophoretic deposition (EPD): fundamentals and applications from Nano- to Micro-Scale structures. Handb. Nanoelectrochemistry. 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15207-3_7-1 (2015).

Hassan, A. G. et al. Effects of varying electrodeposition voltages on surface morphology and corrosion behavior of multi-walled carbon nanotube coated on porous Ti-30 at.%-Ta shape memory alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 401, 126257 (2020).

Besra, L., Uchikoshi, T., Suzuki, T. S. & Sakka, Y. Bubble-Free aqueous electrophoretic deposition (EPD) by Pulse-Potential application. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91, 3154–3159 (2008).

Angulo, A., van der Linde, P., Gardeniers, H. & Modestino, M. Fernández rivas, D. Influence of bubbles on the energy conversion efficiency of electrochemical reactors. Joule 4, 555–579 (2020).

Pawłowski, Ł. et al. Electrophoretically deposited chitosan/eudragit E 100/agnps composite coatings on titanium substrate as a silver release system. Mater. (Basel). 14, 4533 (2021).

Mohammadpourdounighi, N., Behfar, A., Ezabadi, A., Zolfagharian, H. & Heydari, M. Preparation of Chitosan nanoparticles containing Naja Naja oxiana snake venom. Nanomed. Nanatechnol. Biol. Med. 6, 137–143 (2010).

Queiroz, M. F., Melo, K. R. T., Sabry, D. A., Sassaki, G. L. & Rocha, H. A. O. Does the Use of Chitosan Contribute to Oxalate Kidney Stone Formation? Mar. Drugs 2015, Vol. 13, Pages 141–158 13, 141–158 (2014).

Wang, H., Sun, R., Huang, S., Wu, H. & Zhang, D. Fabrication and properties of hydroxyapatite/chitosan composite scaffolds loaded with periostin for bone regeneration. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Toffoli, A. et al. Thermal treatment to increase titanium wettability induces selective proteins adsorption from blood serum thus affecting osteoblasts adhesion. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 107, 110250 (2020).

Boonrawd, W., Awad, K. R., Varanasi, V. & Meletis, E. I. Wettability and in-vitro study of titanium surface profiling prepared by electrolytic plasma processing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 414, 127119 (2021).

Bumgardner, J. D. et al. Contact angle, protein adsorption and osteoblast precursor cell attachment to Chitosan coatings bonded to titanium. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 14, 1401–1409 (2003).

Zanca, C. et al. Composite coatings of Chitosan and silver nanoparticles obtained by galvanic deposition for orthopedic implants. Polym. (Basel). 14, 3915 (2022).

Ding, H. Y., Li, H., Wang, G. Q., Liu, T. & Zhou, G. H. Bio-Corrosion Behavior of Ceramic Coatings Containing Hydroxyapatite on Mg-Zn-Ca Magnesium Alloy. Appl. Sci. Vol. 8, Page 569 8, 569 (2018). (2018).

Pawłowski, Ł. et al. Influence of surface modification of titanium and its alloys for medical implants on their corrosion behavior. Materials (Basel) 15, 7556 (2022).

Bartmanski, M., Zielinski, A., Majkowska-Marzec, B. & Strugala, G. Effects of solution composition and electrophoretic deposition voltage on various properties of nanohydroxyapatite coatings on the Ti13Zr13Nb alloy. Ceram. Int. 44, 19236–19246 (2018).

Jamuna-Thevi, K., Bakar, S. A., Ibrahim, S., Shahab, N. & Toff, M. R. M. Quantification of silver ion release, in vitro cytotoxicity and antibacterial properties of nanostuctured ag doped TiO2 coatings on stainless steel deposited by RF Magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 86, 235–241 (2011).

Simchi, A., Tamjid, E., Pishbin, F. & Boccaccini, A. R. Recent progress in inorganic and composite coatings with bactericidal capability for orthopaedic applications. Nanomed. Nanatechnol. Biol. Med. 7, 22–39 (2011).

Wu, X. et al. The release properties of silver ions from Ag-nHA/TiO2/PA66 antimicrobial composite scaffolds. Biomed. Mater. 5, 044105 (2010).

Pawłowski, Ł., Mirowska, A., Gajowiec, G. & Dzionk, S. The effect of pretreated titanium surface topography on the properties of electrophoretically deposited Chitosan coatings from Ethanol-Based suspensions. Metall. Mater. Trans. Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 56, 2021–2039 (2025).

Lewandowska, K. & Furtos, G. Study of apatite layer formation on SBF-treated Chitosan composite thin films. Polym. Test. 71, 173–181 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Aleksandra Mirowska from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Ship Technology at Gdańsk University of Technology for conducting the surface roughness measurements, and to Prof. Maria Gazda from the Faculty of Applied Physics and Mathematics at Gdańsk University of Technology for performing the XRD analyses. This research was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ŁP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Founding acquisition, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. KK: Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. KS: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. KGT: Writing - Review & Editing. AMG: Methodology, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pawłowski, Ł., Kowalczyk, K., Szczepańska, K. et al. Electrophoretic deposition and characterization of CS/nanoHAp/AgNPs composite coatings on titanium from ethanol-based suspensions. Sci Rep 15, 32855 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18396-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18396-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Influence of Chitosan Concentration and Post-deposition Heat Treatment on Hydroxyapatite-Chitosan Coatings Produced by Electrophoretic Deposition on Ti-6Al-4V for Biomedical Applications

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)