Abstract

Based on an adapted monetary incentive delay task, this study involved 81 participants from China, including 40 from Experiment 1 and 41 from Experiment 2, we conducted behavioral experiments across two distinct gain conditions: one with an unknown expected return and the another with a fixed expected return. Our objective was to examine the effects of investment cost and reward-punishment cues on performance in a simple cognitive task. The findings from Experiment 1 revealed that reward cues significantly promoted individual behavioral performance.In Experiment 2, a significant main effect of investment cost was observed, with individuals facing lower investment costs showing better performance and higher payoffs under equivalent reward-punishment cue conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Studies on investment-based reward decisions1,2 people decide how much cognitive or physical effort to invest based on expected benefits.When cognitive or physical input reaches a certain limit, the willingness to continue to increase effort decreases3,4. However, as the probability or amount of reward increases, people are more willing to perform difficult tasks5 suggesting that they are willing to increase cognitive or physical inputs under higher monetary incentives.

Researchers have found that monetary rewards have a significant effect on an individual’s attentional bias and cognitive control, which motivates people to work harder on tasks to improve behavioral performance6,7,8. That is, monetary inputs as an input cost can also activate cognitive inputs, which in turn affects behavioral performance. This is despite the fact that both rewards and punishments are known to enhance performance on attentional switching tasks9 and that cognitive inputs are crucial for task performance10. However, there are studies that have explored effort only by, for example, changing the task difficulty4 less considering the impact of monetary input as a cost. Therefore, more in-depth research is necessary from the perspective of monetary inputs in the context of different expected benefits situations.

In the field of psychology, both behaviorist and cognitive psychology studies have shown that rewards and punishments motivate motivators and influence cognitive resource allocation and task performance11,12,13 but research on how input levels interact with rewards and punishments is limited and deserves to be in-depth exploration. Adapting to society by effectively processing reward and punishment information is an important aspect of human evolution that has allowed for survival. This process involves the interplay of attention, motivation, and emotion. For example, selective attention allocates resources to critical stimuli14 the motivational system defines task goals to elicit behavior15,16,17; and, motivation enhances executive functioning and task focus, which all have important effects on task performance17,18.

The cost of an individual’s inputs is critical in the pursuit of rewards, and it is often believed that higher costs lead to greater effort and better task performance19. This is because people weigh maximizing rewards and minimizing costs in their decision-making, which affects their attention and resource allocation, and more profoundly influences whether people focus on the task or choose to avoid excessive effort for fear of losing more than they gain3,20. Moreover, coevolutionary game theory provides an important framework for understanding the interaction between individual behavioral decisions and environmental dynamics. On the one hand, there is a dynamic coupling between behavioral decisions and dilemma intensity: changes in the proportion of cooperators in a group can inversely affect the intensity of dilemmas, and the introduction of institutional rewards can effectively promote the optimal state of high cooperation and low dilemmas, avoiding the worst outcome of full defection21. On the other hand, after incorporating an adaptive reward mechanism into public goods games, it was found that reward intensity can be dynamically adjusted with the level of cooperation, thereby forming a stable coexistence state between cooperation and reward intensity, and the minimum reward intensity can promote the emergence of full cooperation22. These findings on the coevolution of behavior and environment and the role of reward and punishment mechanisms provide an important reference for exploring how individuals calibrate their cognitive efforts according to investment costs and reward-punishment cues to adapt to variable cost-return structures, and especially lay a theoretical foundation for understanding the regulatory mechanisms of cognitive task performance under the interaction of social norms, institutional incentives, and individual motivation in group environments. The present study focuses on investigating the effects of investment costs and reward-punishment cues on the performance of simple cognitive tasks. Cooperative behavior, as a core issue in social interaction and group evolution, has been explored in relevant studies from multiple dimensions to reveal its dynamic mechanisms and influencing factors. Existing studies using models such as public goods games have found that global or local state feedback can effectively alleviate cooperation dilemmas, enhance and maintain cooperation levels, and are robust to variables such as punishment costs23. In structured populations, the coevolution of strategies and environmental states is affected by population structure (e.g., the number of neighbors), presenting diverse outcomes such as oscillations, bistability, and the coexistence of cooperation and defection24. In multi-strategy ecosystems, interaction rules within alliances (such as blocking mechanisms and internal rotation) can affect the stability of cooperative alliances25. Regarding the cost issue of reward mechanisms in social dilemmas, the sampling reward mechanism has been proven to effectively promote cooperation under specific conditions (e.g., high reward thresholds, small sample sizes), and there exists a critical threshold for reward intensity26. Meanwhile, computational tools such as large language models also provide new paths for simulating and understanding cooperative behaviors (e.g., fairness preferences, adherence to social norms), reproducing key characteristics similar to human cooperation27. These studies lay a foundation for exploring the driving logic of cooperative behavior from the perspectives of feedback mechanisms, population structure, strategy interaction, reward design, and computational simulation, and also provide a theoretical reference for further investigating how individuals adjust their behavioral performance based on investment costs and reward-punishment cues in task contexts.

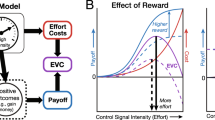

In terms of cognitive task performance, reward-punishment cues and investment cost have significant impacts. Regarding reward and punishment cues, both rewards and punishments can improve the neural mechanisms of cognitive control28 and improve attentional switching task performance29. Regarding investment cost, there are two theoretical controversies about cognitive investment. The ‘‘effort discounting effect” holds that people follow the principle of minimizing effort to avoid exertion, and tend to choose options with lower effort expenditure when the reward value is the same30,31. The ‘‘effort augmentation theory” proposes that effort can enhance the evaluation of reward value, and the brain has different neural activity patterns when processing rewards with different levels of effort, with higher effort levels accompanied by stronger neural representational activities32. Monetary rewards can promote individuals to invest more effort to improve behavioral performance33. Monetary investment can also activate cognitive investment and thus affect behavioral performance, but there are few studies that deeply explore the specific impact of monetary investment as an input cost on task performance.

Based on this, the present study used an adapted monetary incentive delay paradigm to explore the effects of input costs and reward and punishment cues on performance on a simple cognitive task under different payoff contexts (unknown and constant payoff).The aim is to reveal the complex relationship between these three elements and to provide scientific and effective motivational strategies for the fields of education and work management to promote comprehensive individual development and social progress.

Using an adapted Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) paradigm34 this study seeks to explore the brain’s decision-making processes in response to monetary rewards35. The flowchart of the MID is shown in Fig. 1. First, participants are presented with one of three reward cue prompts: a green circle with a “+” symbol indicates that the trial is a monetary incentive trial; a white empty circle indicates a neutral trial; a red circle with a “-” symbol indicates that the trial is a punishment trial. Following the cue prompt is an anticipation interval, during which a fixation point “+” is presented. Then, the target stimulus (i.e., a white square) appears, and participants are required to press the “/“ key on the keyboard as quickly as possible when the target appears on the screen. After the target stimulus disappears, a fixation point “+” is presented, during which participants wait for feedback. In monetary incentive trials, a successful keypress response (i.e., pressing the “/“ key on the keyboard within the target presentation time) will result in feedback of gaining 30 task coins, while an unsuccessful response (i.e., a keypress that occurs before the target appears or after the target disappears) will result in feedback of losing 0 task coins. At the end of the experiment, the task coins will be converted into RMB at a certain ratio and included in the participants’ remuneration. For neutral trials, regardless of whether the behavioral response is successful or unsuccessful, the feedback is “0”, meaning a break-even. For punishment trials, a successful behavioral response will result in feedback of gaining 0 task coins, while an unsuccessful one will result in a loss of 30 task coins.

As a typical goal-directed task, this paradigm reveals the collaborative operation rules of the attention system and the reward system. Specifically, during the execution of the MID task, the attention system plays a key role, responsible for effectively allocating and focusing on cue stimuli closely related to reward and punishment information, thereby prioritizing the processing of such information, enhancing the depth of processing of reward and punishment signals, and effectively inhibiting irrelevant interfering information. Monetary rewards and punishments improve participants’ task performance by enhancing cognitive sensitivity and strengthening exogenous spatial attention.

In the classic Monetary Incentive Delay task, participants are first presented with a cue signal (e.g., a circle) that represents different monetary outcomes (e.g., a reward, a loss, or a neutral situation with no effect). Following the presentation of this incentive cue, there is a brief delay period, namely the anticipation phase. Next, a target stimulus appears, requiring participants to respond to it, such as pressing a key rapidly. Finally, corresponding outcome feedback is provided based on participants’ behavioral responses. The initial incentive cue triggers individuals’ psychological expectations and motivational drive toward the target task, while the subsequent actual feedback results elicit the evaluation process of reward value. Therefore, from the perspective of time sequence, reward processing can be divided into two main phases: the reward anticipation phase and the reward realization phase.

The Monetary Incentive Delay task effectively distinguishes neural signals associated with reward anticipation from those linked to outcome responses, allowing for independent measurement of neural activity during both phases. Additionally, by using graphical cues, cognitive differences between reward types during the anticipation and realization phases can be compared, while controlling for variables such as physical attributes, familiarity, and self-relevance. Building on this classical MID paradigm, the present introduces a novel modification: a cueing phase for investment cost presented before the reward and punishment cues. By integrating this innovation with two distinct payoff scenarios — unknown expected payoff and constant expected payoff — the study aims to explore how investment costs and reward-punishment cues affect performance in a simple cognitive task. This investigation seeks to uncover the complex relationship between investment costs, reward-punishment cues, and task performance. Ultimately, the findings are expected to provide more scientific and effective motivational strategies, offering new perspectives in fields such as education and work management, and, contributing to the holistic development of individuals and societal progress.

Experiment 1: The impact of investment on task performance when the expected return is unknown

Research purpose and hypotheses

Experiment 1 aimed to examine the effects of investment cost and reward cues on task performance under conditions where the expected payoff is unknown. Specially, the study investigated differences in participants’ responses to varying levels of investment cost when faced with an unknown payoff. An adapted Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) paradigm was used to assess how investment costs and reward cues influence performance on a simple cognitive task. The following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1

Participants’ task performance differs significantly across levels of investment cost when facing either a reward (unknown expected payoff) or a neutral cue. At higher investment cost, participants are expected to show greater motivation and improved task performance, as reflected in behavioral outcomes such as faster response times and higher accuracy rates.

Hypothesis 2

Participants will demonstrate faster response time and greater accuracy under reward cues compared to neutral cue.

Hypothesis 3

There will be an interaction between investment cost and reward cue, such that participants respond faster and more accurately under conditions of high investment cost coupled with a reward cue.

Experiment methods

Participants

A total of 40 from a university in central China participated in the experiment(M = 21.71 years old, SD = 2.62). All participants were right-handed (psychological studies suggest that there may be differences in the functions of the left and right cerebral hemispheres between left-handed and right-handed individuals, and according to the rules of psychological experiments, this variable is usually unified as right-handedness). They had normal vision or corrected-to-normal vision, mainly to ensure that experimental stimuli could be accurately perceived and processed, and to reduce experimental errors caused by abnormal visual functions36. Participants were required to have no major physical, mental, or neurological diseases. The core purpose was to exclude the interference of diseases on the core variables of the experiment, ensure that the experimental results could accurately reflect the association between ‘‘monetary incentives’’ and target psychological processes such as ‘‘delayed processing’’ and ‘‘motivational response’’, and guarantee the validity, reliability, and scientificity of the experiment.Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed beforehand that the experiment involved a button-press response task. Upon completing the experiment, participants received compensation based on their task scores and performance. The research content and process were approved by the Ethics Committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by including a statement in the methods section.

Experimental design

The experiment employed a 2 × 2 within-subjects design, with two factors: investment cost (high, low) and reward cue (reward, neutral). Investment cost was treated as independent variable 1, and reward cues as independent variable 2. In this case, the expected payoff associated with two possible outcomes: large or small monetary rewards. The dependent variables included participants’ behavioral responses, especially response time and accuracy, under the different cue conditions.

Experimental materials and tasks

The experimental tasks were designed and presented using Matlab R2020a. Participants completed the tasks in a controlled laboratory environment, which was quiet and maintained at a stable room temperature. Extraneous variables such as noise and ambient temperature, were strictly controlled to ensure that external factors did not influence performance outcomes.

The formal experiment consisted of six independent cue-response groups, each containing 40 trials that were presented in a random order, for a total of 240 trials. These trials were divided into three blocks, each with the same task structure. After completing each block, participants were given the opportunity to rest and adjust before proceeding to the next block at their own pace. Cues were presented using numbers to indicate different levels of investment cost, and circles of different colors to represent reward cue (as shown in Fig. 2). Specially, following Gneezy’s experimental design37 “-1” denoted low investment, while “-10” indicated high investment. The white circle served as a neutral cue stimulus, signifying no reward on that trial, whereas the green circle represented a potentially rewarding trial. Participants were required to press the space bar as a response within a specified time frame upon the reappearance of white squares. For trials involving a reward cue, a successful response would lead to one of two possible reward outcomes, presented randomly with equal probability (50% each): a small reward (+ 6) or a large reward (+ 60). Incorrect responses or trails with a neutral cue would result in a feedback of “0”.

At the start of each experiment, a sequence of stimuli was presented on the screen: first, a 1000-ms gaze point “+”, followed by a 1000-ms display of the investment amount (-1 or -10), and then a 1000-ms reward cue (either a green circle or a white circle). Afterward, a randomly time target-waiting phase, lasting between 500ms to 1000ms, was presented at the center of the screen (“+”). Following this, the target stimulus, a white square, appeared for a random duration between 80ms-280ms. The participant’s task was to press the space bar as quickly as possible during the presentation of the target stimulus. A response made within the display time of the white square was considered a successful hit. Responses made either too early or too late were considered failures, resulting in no hit. After a 1000ms blank screen, the corresponding feedback (based on performance) was provided.

Experimental procedures

Participants were recruited through online postings and scheduled appointments in advance. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were asked to sign a paper version of the informed consent form, which provided a brief overview of the experimental procedure and details regarding the remuneration. Following this, participants completed a demographic questionnaire. After completing the questionnaires, participants were taken to a private experimental room. Given the lengthy duration of the experimental procedure, the researcher ensured that the room temperature was adjusted to the participants’ comfort. Participants were also reminded to sit in a comfortable position and maintain an appropriate distance from the computer monitor.

Once all preparations were completed, the experiment was initiated using Matlab R2020a. The main research provided a detailed explanation of the experimental task, requirements, and relevant precautions. Participants were then asked whether they fully understood the experimental procedure. To ensure familiarity with the task, participants completed a short practice session consisting of 24 trials, which mirrored the formal experiment in structure and procedure. Following the practice session, the formal experiment began. To minimize distractions, participants were instructed to set their cell phones to silent mode and leave them outside the laboratory, where they securely stored by the researcher.

During the formal experiment, participants began with an initial balance of 1000 units of currency displayed on the screen. Each round started with a coin toss, which determined the investment cost—either 1 units or 10 units. The system randomly controlled the presentation of these investment costs, ensuring an equal distribution of both values. After the coin toss, the incentive cue was presented randomly. A green cue indicated a potential reward, where participants could earn a random monetary reward if they successfully completed the ask in the subsequent trial. Failure to complete the task resulted in no reward. A white cue represented a neutral condition, where no reward or penalty was given regardless of task performance. In each trial, participants were required to respond with a keystroke, and their performance (gained or lost amount) was displayed during the feedback phase. The final total amount of money earned determined the participant’s compensation, with higher totals yielding higher rewards. Any irregular behavior, such as intentionally pressing the key too early or failing to press the key at all, resulted in a deduction from the subject fee.

Results

In this experiment, the raw data were processed and analyzed using Matlab R2020a and Excel. Reaction times and the number of correct key presses were extracted for each condition, based on different levels of investment cost and reward cue. Three participants were excluded from the analysis: those with reaction times of less than 100ms in any condition, participants with an early keystroke rate exceeding 20% (calculated as the number of early keystrokes divided by the total number of trials), and participants with a correct rate response rate below 70%. According to the 2 × 2 within-subjects design — two levels of investment cost (high investment, low investment) and two reward conditions (reward cue, neutral cue) — the reaction times and accuracy rates for participants’ responses to the cognitive task were analyzed. Data were processed using Matlab R2020a and Excel, with the results presented in Table 1; Figs. 3 and 4. To further examine the effects of investment cost and reward cue on performance, repeated measures ANOVA was conducted using SPSS 27.0. The analysis focused on participants’ reaction times and accuracy across the different conditions.

Response time

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of investment level and reward cue on response times. The results are shown in Table 2, the analysis revealed a nonsignificant main effect of investment level, \(\:F\)(1, 35) = 1.11, p > 0.05. However, there was a significant main effect of reward cue, \(\:\text{F}\)(1, 35) = 47.16, p < 0.001, \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{p}}^{2}\:\)= 0.57. Participants responded significantly faster under the reward cue condition (M = 224.27, SE = 2.71) compared to the neutral cue condition (M = 233.61, SE = 2.79). The interaction between investment level and reward cue was not significant, F(1, 35) = 1.68, p > 0.05.

Response correctness

A repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to assess the effects of investment condition and reward cue on response correctness. The results are shown in Table 3, the analysis revealed a nonsignificant main effect of investment condition, F(1, 35) = 1.23, p > 0.05. However, there was a significant main effect of reward cue, F(1, 35) = 37.14, p < 0.001, \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\) = 0.52. Participants had a significantly higher correctness rate under the reward cue condition (M = 0.80, SE = 0.01) compared to the neutral cue condition (M = 0.71, SE = 0.01). The interaction between investment and cue was not significant, F(1, 35) = 0.60, p > 0.05.

Discussion

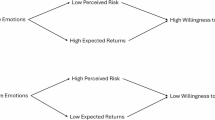

Experiment 1 examined individual task performance in response to varying investment costs under conditions of uncertain expected benefits. An adapted monetary incentive delay paradigm was used to compare participants’ reaction times and hit rates across different levels of investment cost and reward cue conditions. The results from Experiment 1 demonstrated a significant main effect of the reward cue on reaction times, with participants responding faster in trials featuring a reward cue compared to those with a neutral cue. Similarly, for response accuracy, there was a significant main effect of the reward cue, with higher correctness rates observed under the reward cue condition compared to the neutral cue condition. The results align with previous studies, which suggested that reward cues can enhance motivation, increase enthusiasm, and improve cognitive processing related to reward stimuli, thereby positively influencing task performance13,38,39. The reward cue’s ability to significantly enhance both response time and accuracy indicates that external rewards play a crucial role in motivating individuals to perform tasks more effectively.

The results of Experiment 1 showed that participants did not exhibit significant differences in task response time or accuracy across varying levels of investment cost, nor was there a significant interaction between investment cost and reward cue. This outcome contrasts with previous studies suggesting that greater cognitive effort expenditure increase the brain’s sensitivity to rewards, thereby enhancing task performance40. In prior research, the effect of investment on task performance was often explored by manipulating the level of cognitive effort required, typically by varying task difficulty. For instance, manipulating arithmetic problems with different difficulty levels has shown that the degree of cognitive effort is positively correlated with task complexity41. In contrast, the present experiment used monetary investment as the cost variable to investigate its influence on task performance. According to motivation theory and loss aversion theory, higher investment costs should prompt greater attention and allocation of cognitive resources. Thus, it was expected that participants facing high investment costs would exhibit enhanced task performance compared to those facing lower costs. However, the task in this experiment—a simple push-button response—did not demand complex cognitive efforts or intricate mental operations. As a result, while higher investment costs may have activated more cognitive resources, these additional resources may not have significantly influenced performance on such a straightforward task.

The inconsistency between the findings and the expected results may be attributed to the participants’ realization, after several trials, that the payoffs for successful hits under high-investment reward cues were random and similar to those under low-investment reward cues. As a result, participants were unable to form a clear expectation of the potential payoffs after making correct responses, so it resulted in the high investment cost fails to evoke high motivation in participants, and behavioral performance is not significant.

Experiment 2: The impact of investment on task performance when the expected return is constant

Research purpose and hypotheses

To further investigate the effects of investment cost and reward cues on simple cognitive task performance, Experiment 2 builds upon the design of Experiment 1 by introducing a punishment cue. To ensure participants had clear expectations and goal-directed motivation when responding to the reward-punishment cues under different investment costs, this experiment featured a known and fixed expected return. Additionally, a specific cue amount cue was provided alongside the reward and punishment cues to clarify the stakes involved.

Hypothesis 1

There will be a significant main effects of investment cost. Participants are expected to have shorter response times and higher accuracy rates under high investment cost compared to low investment cost.

Hypothesis 2

There will be a significant main effect of reward and punishment cues. Both cues will enhance participants’ task performance, with faster reaction times and higher correctness rates observed under the reward condition.

Hypothesis 3

There will be a significant interaction between investment cost and reward-punishment cues. Participants’ reaction times and accuracy rates will differ significantly depending on the combination of investment cost and the reward- punishment cue.

Experiment methods

Participants

A total of 41 participants (M = 22.2 years old, SD = 2.32) were recruited for the experiment. All participants were students from a university in central China, with normal or corrected to normal vision, were right-handed, and reported no significant physical, mental, or neurological disorders. None of the participants had participated in participate in this Experiment 1. At the end of the experiment, participants received appropriate remuneration based on their task scores and overall performance. The research content and process was approved by the Ethics Committee.

Experimental design

The experiment employed a two-factor within-participants design with two independent variables: investment cost (high investment, low investment) and reward-punishment cue (reward, neutral, punishment). This resulted in a 2 × 3 experimental design. Independent variable 1 being investment cost, with two levels—high and low. Independent variable 2 being reward-punishment cue, with three levels—reward, neutral, and punishment. The dependent variables were participants’ behavioral outcomes, specially response time and correctness in completing the simple cognitive task across the different conditions.

Experimental materials and tasks

The experimental materials and tasks used in Experiment 2 were identical to those in Experiment 1. The formal experiment comprised six independent cue response groups, each consisting of 40 trials, resulting in a total of 240 trials. These trials were divided into three blocks, with the task in each block remaining the same. Participants completed one block, took a break to rest and adjust, and then proceeded to the next block at their own pace. The cue were presented visually, with numerical indicators representing the two different levels of investment and colored circles representing the reward-punishment conditions. As shown in Fig. 5, the numbers “-1” and “-10” represented low and high investment, respectively. The white circle is a neutral cue, representing no reward or punishment for the current trial. The green circle is a reward cue, representing a potential reward for the current trial. The red circle is a punishment cue, representing a potential penalty for the current trial. Participants were tasked with pressing the space bar as quickly as possible within the time frame during which a white squares appeared. A correct keystroke response was considered a successful hit if the response time occurred within the presentation time of the white square. If the reaction time was outside this window—either pressing the key too early or too late—the response was classified as a failed keystroke, and the hit is not successful.

Experimental procedure

The experimental procedure followed the same format as in Experiment 1. Participants were recruited through online posting detailing the experimental task, and appointments were made in advance. Upon arriving at the laboratory, participants were first asked to complete a demographic information questionnaire. Given the length of the experimental process, the researcher ensured participants comfort by checking and adjusting the room temperature as needed. Participants were also reminded to settle into a comfortable sitting position and to maintain an appropriate distance from the computer monitor throughout the experiment.

After all preparations were completed, the experimental program was initiated using Matlab R2020a. The lead researcher explained the experimental task, the specific requirements, relevant precautions, and the criteria for remuneration based on task performance. Participants were then given a brief practice session to familiarize themselves with the procedure. The practice session consisted of 24 trials, which followed the same structure as the formal experiment. At the end of the practice session, participants were asked whether they understood and whether they needed further practice. Once participants confirmed their understanding, the formal experiment began. To minimize distractions, participants were instructed to set their cell phones to silent mode and leave them outside the laboratory in the safekeeping of the main experimenter during the session.

During the formal experiment, participants began with an initial capital of 1000. Each round started with a coin toss, determining the investment for that round. There were two possible investment amounts: 1 units or 10 units, both of which were randomly presented by the system. The number of trails for each investment level was balanced. The corresponding investment amount for each round was deducted from the total amount. Following the investment, an incentive cue was presented randomly, with three possible cues: green represents the reward cue—if the participants successfully complete the next task, they received the corresponding reward; if unsuccessful, no reward was given. White represents the neutral cue—there was no reward for the next task, regardless of task perfoemance. Red represents the punishment cue—if the participant failed to complete the next task, a penalty was deducted; if successful, no penalty or reward awas applied. Participants had to make a keystroke response after each cue. Presentation. Performance in the task affected their final score, and higher scores resulted in higher remuneration. Any irregular behavior, such as intentionally pressing a key too early or failing to respond, led to a deduction in the participant’s subject fee.

Results

The raw data exported from the experiment were filtered using Matlab R2020a and Excel. The filtering process involved selecting reaction times and number of correct keystrokes corresponding to each investment cost and reward-punishment cue condition. Data from three participants were excluded due to reaction times below 100ms in each condition, as well as data from participants whose early keystroke rate exceeded 20% (calculated as the number of early keystrokes divided by the total number of trials) or who had a accuracy rate below 70%. According to the two-factor within-participants experimental design involving 2 levels of investment cost (high investment, low investment) and 3 types of reward-punishment cues (reward, neutral, punishment), the reaction time and accuracy rate under each condition were analyzed. Matlab R2020a and Excel were used to calculate descriptive statistics, which are presented in Table 4; Figs. 6 and 7. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted using SPSS 27.0 to analyze the response times and correct rates of responses in each condition.

Response time

A repeated measures ANOVA on response time is shown in Table 5, and there was a significant main effect of investment cost, \(\:F\)(1, 37) = 5.76, p < 0.05, \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2\:}\)= 0.14. Participants responded faster under the low investment cost condition (M = 216.61, SE = 4.26) than under the high investment cost condition (M = 221.37, SE = 4.16). A significant main effect of reward-punishment cue was also found, \(\:F\)(2, 36) = 14.81, p < 0.001, \(\:{\eta\:}_{p\:}^{2}\)= 0.45. Participants had the faster response times to reward cue (M = 212.94, SE = 4.18), followed by the punishment cue (M = 217.11, SE = 4.26), and the slowest response times occurred under the neutral cue condition (M = 226.91, SE = 4.40). However, the interaction effect between investment cost and reward-punishment cue was not significant, F(2, 36) = 1.54, p > 0.05.

Response correctness

The repeated measures ANOVA on correctness is shown in Table 6, and the main effect of investment cost was nonsignificant, F(1, 37) = 8.53, p = 0.36, indicating that investment cost did not significantly affect participants’ accuracy. There was a significant main effect of reward-punishment cue, F(2, 36) = 24.12, p < 0.001, \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\:\)= 0.57. Correctness was significantly higher in the rewarded cue condition (M = 0.75, SE = 0.02), followed by the punishment cue condition (M = 0.73, SE = 0.02), and lowest in the neutral cue condition (M = 0.61, SE = 0.02). The interaction effect between investment cost and reward-punishment cue was not significant, F(2, 36) = 0.42, p = 0.66.

Discussion

In Experiment 2, participants were presented with fixed reward-punishment cues to explore the effect of investment cost on task performance within a constant expected reward context. The results for response times showed a significant main effect of investment cost, with faster responses observed at low investment cost. This suggests that participants applied their own value-calculation system, aligning with the effort discounting effect in previous studies. Individuals tend to make decisions by minimizing effort while maximizing payoffs3,20. Participants’ cost-benefit evaluations indicated that the low investment condition yielded the highest, expected net benefits. As a result, participants were more motivated to perform well under lower investment costs, leading to an enhanced task performance. This suggests that while investment cost does influence task performance, the effect of expected gain outweighs the direct impacts of investment cost.

The results also showed a significant main effect of reward-punishment cues on both response time and correctness. Task performance under the reward cue was superior to that under the punishment cue, and performance under the neutral cue was the worst. This result supports the theory of reinforcement sensitivity, which highlights the differential effects of rewards and punishments on behavior. The reward-punishment cues likely activated participants’ behavioral activation system and the behavioral inhibition system, influencing their decision-making and motivation to avoid harm. These findings align with prior research demonstrating that monetary incentives improve performance on cognitive tasks9,38,42 and they further suggesting that rewards are more effective than punishments.

General discussion

When comparing task performance under the reward cue at low investment cost across Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, it was found that participants’ response times were faster in Experiment 2. This suggests that when participants were provided with known and fixed cues for expected payoffs, they exhibited stronger motivation and consequently faster response times. This finding align with previous research, which indicates that a clear expected payoff can have a more substantial motivational effect on individuals, enhancing their behavioral performance43. Specially, when participants are aware of the reward’s value, their motivation to complete tasks efficiently increases. This result further reflects findings that higher reward amount lead to great effort expenditure44. When faced with larger rewards or higher probabilities of obtaining them, individuals are more likely to engage in difficult tasks5.

In Experiment 1, participants face a stochastic payoff situation with unknown expected returns under, while in Experiment 2, they operated in a more controlled scenario with constant expected returns. This distinction is crucial: in the consistent payoff situation of Experiment 2, participants under low investment cost performed better since they had a celar sense of their potential gains. The findings of both experiments are aligned with the principle of effort minimization3. When expected returns are equal across conditions, participants naturally exert less effort under low investment costs, as this results in a more favorable cost-benefit ratio. These results are consistent with the broader effort discounting framework, in which individuals tend to avoid unnecessary cognitive or physical effort when conditions allow.

This study introduces the novel variable of investment cost into the exploration of reward-punishment cues and cognitive task performance. The results of Experiment 1 confirm that reward cues significantly enhance behavioral performance, consistent with previous studies9. However, the effect of investment cost was not significant when expected benefit were unknown, likely because participants could not form stable reward expectations under random conditions. This highlights the importance of consistent payoff conditions in motivating individuals to perform optimally. In Experiment 2, where reward-punishment cues were fixed and the expected return was known, a significant main effect of investment cost emerged. Participants with low investment costs performed better when presented with the same reward-punishment cues as those under high investment costs. This supports the ideas that participants adjust their cognitive resource investment based on their expected returns. As reward values increase, so does the proportion of individuals willing to expend high effort45,46.

While this study has provided insights into the effects of investment cost and reward-punishment cues on cognitive task performance, it has not fully explored the underlying psychological mechanisms. Future research could benefit from combining neuroscience tools such as fMRI and EEG with computational modeling to examine cognitive processes at the neurophysiological level. This would allow for a deeper understanding of how investment cost, reward-punishment cues, and individual intrinsic motivation interact to influence performance. In recent years, brain imaging technology has become a valuable tool in studying the mechanisms of motivation and emotion. In the future, integrating these physiological measures could shed light on how external incentives and internal cognitive process jointly shape task outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Green, M. F., Horan, W. P., Barch, D. M. & Gold, J. M. Effort-based decision making: A novel approach for assessing motivation in schizophrenia. J. Schizophrenia Bull. 41 (5), 1035–1044 (2015).

Gold, J. M., Waltz, J. A. & Frank, M. J. Effort cost computation in schizophreni-a: A commentary on the recent literature. J Biol. Psychiatry. 78 (11), 747–753 (2015).

Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W. & Myers, J. An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 36 (6), 661–679 (2013).

Inzlicht, M., Schmeichel, B. J. & Macrae, C. N. Why self-control seems (but ma-y not be) limited. J. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18 (3), 127–133 (2014).

Reddy, L. F. et al. Effort-based decision-making paradigms for clinical trials in schizophrenia: part 1—psychometric characteristics of 5 paradigms. J. Schizophrenia Bull. 41 (5), 1045–1054 (2015).

Kiss, M., Driver, J. & Eimer, M. Reward priority of visual target singletons modulates event-related potential signatures of attentional selection. J. Psychol. Sci. 20 (2), 245–251 (2009).

Theeuwes, J. & Belopolsky, A. V. Reward grabs the eye: oculomotor capture by rewarding stimuli. J. Vis. Res. 74, 80–85 (2012).

Fröber, K. & Dreisbach, G. The differential influences of positive affect, random reward,and performance-contingent reward on cognitive control. J. Cogn. Affect. BehavioralNeuroscience. 14, 530–547 (2014).

Savine, A. C., Beck, S. M., Edwards, B. G., Chiew, K. S. & Braver, T. S. Enhancement of cognitive control by approach and avoidance motivational States. J. Cognition Emot. 24 (2), 338–356 (2010).

Kovanović, V. et al. Towards automated content analysis of discussion transcripts: A cognitive presence case. J. In Proceedings of the sixth international conference on learning analytics & knowledge.15–24, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2883851.2883950

Pessoa, L. & Engelmann, J. B. Embedding reward signals into perception and cognition. J. Front. Neurosci. 4, 1223 (2010).

Ballard, T., Sewell, D. K., Cosgrove, D. & Neal, A. Information processing Und-erReward versus under punishment. J. Psychol. Sci. 30 (5), 757–764 (2019).

Cheng, P., Rich, A. N. & Le Pelley, M. E. Reward rapidly enhances visual perception. J. Psychol. Sci. 32 (12), 1994–2004 (2021).

Egner, T. & Hirsch J.Cognitive control mechanisms resolve conflict through cortical amplification of task-relevant information. J. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1784–1790 (2005).

Schultz, W. Multiple reward signals in the brain. J. Nat. Reviews Neurosci. 1, 199–207 (2000).

Pessoa, L. How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? J. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 160–166 (2009).

Chelazzi, L., Perlato, A. & Santandrea, E. Della libera, C. Rewards teach visual selective attention. J. Vis. Res. 85, 58–72 (2013).

Padmala, S. & Pessoa L.Reward reduces conflict by enhancing attentional control and biasing visual cortical processing. J. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 (11), 3419–3432 (2011).

Vostroknutov, A., Tobler, P. N. & Rustichini A.Causes of social reward differences encoded in human brain. J. J. Neurophysiol. 107 (5), 1403–1412 (2012).

Gheza, D., Kool, W. & Pourtois, G. Need for cognition moderates the relief of avoiding cognitive effort. J. Plos One. 18 (11), e0287954 (2023).

Hua, S., Xu, M., Liu, L. & Chen, X. Coevolutionary dynamics of collective Cooperation and dilemma strength in a collective-risk game. J. Phys. Rev. Res. 6 (2), 023313 (2024).

Hua, S. & Liu, L. Coevolutionary dynamics of population and institutional rewards in public goods games. J. Expert Syst. Applications. 237, 121579 (2024).

Wang, Q., Chen, X. & Szolnoki, A. Evolutionary dynamics in state-feedback public goods games with peer punishment. J Chaos: Interdisciplinary J. Nonlinear Science 35(4) (2025).

Wang, Q., Chen, X. & Szolnoki, A. Coevolutionary dynamics of feedback-evolving games in structured populations. J. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 193, 116070 (2025).

Szolnoki, A. & Chen, X. When faster rotation is harmful: the competition of alliances with inner blocking mechanism. J. Phys. Rev. Res. 6 (2), 023087 (2024).

Xiao, J., Liu, L., Chen, X. & Szolnoki, A. Evolution of Cooperation driven by sampling reward. J. J. Physics: Complex. 4 (4), 045003 (2023).

Lu, Y., Aleta, A., Du, C., Shi, L. & Moreno, Y. Llms and generative agent-based models for complex systems research. J. Phys. Life Reviews. 51, 283–293 (2024).

Cubillo, A., Makwana, A. B. & Hare, T. A. Differential modulation of cognitive control networks by monetary reward and punishment. J. Social Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 14 (3), 305–317 (2019).

Hanadelansa, H. The impact of giving rewards and punishment on increasing employee performance. J. Adv. Hum. Resource Manage. Res. 1 (2), 66–77 (2023).

Bogdanov, M., Renault, H., LoParco, S., Weinberg, A. & Otto, A. R. Cognitive effort exertion enhances electrophysiological responses to rewarding outcomes. J. Cereb. Cortex. 32 (19), 4255–4270 (2022).

Klein-Flügge, M. C., Kennerley, S. W., Saraiva, A. C., Penny, W. D. & Bestmann, S. Behavioralmodeling of human choices reveals dissociable effects of physical effort and Temporal delay on rewarddevaluation. J. PLoS Comput. Biology. 11 (3), e1004116 (2015).

Wang, L., Zheng, J. & Meng, L. Effort provides its own reward: endeavors reinforce subjectiveexpectation and evaluation of task performance. J. Experimental Brain Res. 235 (4), 1107–1118 (2017).

Hansamali, H. G. C., Francis, S. J., Sirikumar, T. & Ganeshamoorthy, S. Impact of rewards system on employee performance. J (2024).

Knutson, B., Fong, G. W., Adams, C. M., Varner, J. L. & Hommer D.Dissociation Ofreward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. J. Neuroreport. 12 (17), 3683 (2001).

Lutz, K. & Widmer, M. What can the monetary incentive delay task tell Us about the neural processing of reward and punishment? J Neurosci. Neuroeconomics 33–45 (2014).

Ke Zengjin & Tingting, L. Yang xinguo.why does loyalty foster trustworthiness?? Empirical evidence on collectivism’s impact on college students’ integrity. J. Credit Ref. 43 (06), 22–30 (2025).

Gneezy, U. & Deception The role of consequences. J. Am. Economic Rev. 95 (1), 384–394 (2005).

Dreisbach, G. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: the cost and bene-fits ofreduced maintenance capability. J. Brain Cognition. 60 (1), 11–19 (2006).

Krawczyk, D. C. & D’Esposito, M. Modulation of working memory function by motivation through loss-aversion. J. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34 (4), 762–774 (2013).

Lallement, J. H. et al. K.Effort increases sensitivity to reward and loss magnitude in the human brain. J. Social Cogn. AndAffective Neurosci. 9 (3), 342–349 (2014).

Yeo, G. & Neal A.Subjective cognitive effort: A model of states, traits, and time. J. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 (3), 617 (2008).

Engelmann, J. B. & Pessoa L.Motivation sharpens exogenous Spatial attention. J. Emot. 7 (3), 668–674 (2007).

Kring, A. M. & Barch, D. M.The motivation and pleasure dimension of negative symptoms: neural substrates and behavioral outputs. J. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24 (5), 725–736 (2014).

Chelonis, J. J., Gravelin, C. R. & Paule, M. G.Assessing motivation in children using a progressive ratio task. J. Behav. Processes. 87 (2), 203–209 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. C.Anhedoniain schizophrenia: deficits in both motivation and hedonic capacity. J. Schizophrenia Res. 168 (1–2), 465–474 (2015).

Hagger, M. S. et al. A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. J. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 (4), 546–573 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for their efforts in our study.

Funding

This research was supported by the Soft Science Project of Henan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (242400410051) and the phased results of the 2022 Henan Province Undergraduate Research Teaching Series Project(2022SYJXLX103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X.C.;methodology, L.L.Y.;formal analysis, P.B.W.;writing—original draft, L.X.C.; data curation, W.H.M.; writing—review and editing, L.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board Statement: The research content and process were approved by the Ethics Committee of Henan University. (20240409001).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xuchu, L., Lingyuan, L., Bingwu, P. et al. The effects of investment cost and cues of reward and punishment on cognitive task performance. Sci Rep 15, 33674 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18510-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18510-z