Abstract

Academic achievement is a key indicator of adolescents’ development and future potential. While physical activity is known to benefit physical and mental health, its indirect effects on academic performance through psychological mechanisms are less understood. A random sample of 458 adolescents from junior and senior high schools in China completed a structured questionnaire assessing physical activity, self-concept, physical and mental health, and academic achievement. Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and the PROCESS macro (Model 6) to test a chain mediation model. Physical activity was positively associated with academic achievement. Self-concept did not mediate this relationship independently, but physical and mental health emerged as a significant mediator. Moreover, a sequential pathway was identified, in which physical activity enhanced self-concept, which in turn improved physical and mental health, ultimately promoting academic achievement. Physical activity contributes to academic success not only through direct effects but also through a psychological pathway involving improved self-concept and health. These findings highlight the value of integrating physical activity into educational contexts to support both psychological well-being and academic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Academic achievement (AA) plays a central role in the developmental trajectory of adolescents, significantly shaping their future opportunities1. Hattie defines AA as the progress students make in their academic learning process, assessed through performance in tests, examinations, and other evaluations2. In China, AA is typically measured through students’ performance in key subjects such as Chinese, mathematics, and English3. The term “AA” in this research explicitly refers to students’ exam results in the three specified subjects. Extensive research has focused on adolescents’ AA, exploring its influencing factors and its predictive value for future outcomes3,4,5,6. Existing studies on the determinants of AA largely emphasize two dimensions: internal factors and external environmental factors. Internal factors include self-concept (SC)7, physical and mental health (PMH)8, and adverse childhood experiences6. External environmental factors, such as PA5, peer relationships3, and social activities4, also influence adolescents’ AA. This positive association has been consistently observed across age groups and genders, underscoring the universal benefits of regular PA for AA5,7. AA determines the potential for individual progress while serving as a fundamental criterion for assessing how well a country’s education system functions. Exploring the factors and mechanisms influencing AA, as well as developing effective intervention strategies, is of substantial practical importance for promoting adolescents’ holistic development.

Theories and hypotheses

Theoretical basis

Self-Concept Theory, as proposed by Shavelson, et al.9, provides a multidimensional framework for understanding how individuals perceive and evaluate their own abilities across different domains, including academic settings. Within this framework, SC refers to students’ beliefs and perceptions about their academic competence and performance. A positive SC is considered a critical predictor of motivation, emotional well-being, and AA. It fosters confidence, persistence, and engagement in learning tasks, directly contributing to higher academic success. Conversely, a negative SC may lead to anxiety, avoidance behaviors, and lower academic outcomes9,10. Recent longitudinal research corroborates these links, indicating that stronger adolescent SC positively predicts later academic performance and emotional well-being11.

For adolescents, PA plays a pivotal role in developing SC by providing mastery experiences, opportunities for skill acquisition, and social recognition from peers and teachers. Intervention and meta-analytic studies have consistently demonstrated that regular PA significantly enhances adolescents’ SC and self-esteem, with reported effect sizes around g = 0.49, which is considered a medium effect size12. Moreover, the benefits of PA extend beyond the domain of SC: recent longitudinal studies have shown that higher levels of physical fitness in early adolescence are associated with a reduced risk of mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, during later adolescence13. Improvements in SC derived from PA also contribute to PMH by fostering emotional resilience, supporting stress regulation, and promoting adaptive coping strategies14. Importantly, adolescents experiencing comorbid PMH difficulties often exhibit lower SC, underlining its central role in promoting psychological well-being.

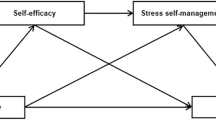

Drawing on this theoretical foundation, the present study proposes that PA indirectly promotes AA by enhancing SC, which subsequently supports adolescents’ PMH and facilitates academic success. This chain mediation framework aligns with Self-Concept Theory and highlights how positive self-perceptions cultivated through PA can be transformed into psychological well-being and improved academic outcomes.

Physical activity and academic achievement

For decades, enhancing adolescents’ AA through PA has been a focal issue in education. PA encompasses not only exercise but also various forms of physical movement, such as play, household chores, recreational activities, and active commuting methods like cycling or walking15. A substantial body of research has demonstrated that PA contributes positively to adolescents’ AA7,16,17. Similarly, analyzed data from a nationally representative U.S. adolescent sample, revealing a significant positive correlation between PA frequency and AA16. Additionally, evidence from Frikha17 study on female physical education majors in Saudi Arabia indicates that PA is positively associated with AA, but this association is primarily realized indirectly through enhancing pleasure, fostering intrinsic motivation, and promoting a healthier body mass index.

The mediating role of self-concept

SC is regarded as a cognitive psychological model that individuals construct about their abilities and attributes18. During adolescence, the role of SC becomes particularly prominent, being considered one of the key goals of education as it directly impacts adolescents’ mental health and developmental processes19. Research has shown that adolescents with a higher SC tend to achieve better academic outcomes, while those with a lower SC are more likely to encounter academic challenges, indicating a positive correlation between SC and AA20. Moreover, a growing body of evidence highlights the positive effects of PA on enhancing adolescents’ SC21,22,23. For example, González-Valero, et al.21 investigated the impact of PA on adolescents’ SC before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, finding a positive correlation between PA and SC, with gender acting as a moderator in this relationship. Palenzuela-Luis, et al.22 further compared the effects of PA on SC among adolescents from different countries, demonstrating the universally positive influence of PA in boosting SC. PA not only enhances adolescents’ SC but also positively impacts their AA7,24. For instance, Batista, et al.7 analyzed the effects of PA among students in public schools in Portugal, finding that students participating in PA exhibited a significantly improved SC. This improvement, in turn, positively influenced their AA, with SC explaining 41% of the variance in academic performance. These findings underscore the mediating role of SC in the relationship between PA and AA, revealing that PA can directly impact academic performance and indirectly enhance it through improved SC. Additionally, Galán-Arroyo, et al.25 further confirmed the positive correlation between adolescents’ SC and PMH, highlighting how a positive SC contributes to better physical and mental well-being among adolescents. Thus, SC not only plays a crucial role in the relationship between PA and AA but also serves as a vital factor in promoting adolescents’ PMH.

The mediating role of physical and mental health

PMH encompasses both physical well-being and psychological well-being26. Adolescents with better PMH often perform better academically, whereas those with physical or psychological health issues are more likely to face academic challenges8. As a result, improving adolescents’ PMH has become an essential strategy for enhancing AA. PA serves as an effective intervention for addressing mental health issues among adolescents27 and plays a positive role in improving their physical fitness28. A growing body of research has demonstrated the mediating role of PMH in the relationship between PA and AA29,30. For instance, Wang and Guo29 conducted a study on Chinese adolescents, revealing that PMH mediated the effects of PA on AA. Their findings underscore the indirect impact of PA on academic performance through enhanced PMH. Furthermore, Liu, et al.30 provided additional evidence that PA improves AA by promoting PMH and enhancing cognitive function, highlighting the critical mediating role of health in this process. These studies illustrate that PA not only directly influences adolescents’ AA but also indirectly enhances it by improving their PMH.

The chain mediating role of self-concept and physical and mental health

Building on prior research, most studies have predominantly focused on the singular mediating roles of SC or PMH in the relationship between PA and AA. However, substantial evidence indicates a significant positive correlation between SC and PMH31,32,33,34. For instance, Zhang, et al.31 examined the effects of PA on depression among college students and its underlying mechanisms, revealing that SC plays a pivotal mediating role in the relationship between PA and depression. PA was found to indirectly improve students’ PMH by enhancing their SC, leading to better overall well-being35. Additionally, according to Halat, et al.36, students with enhanced PMH exhibit a greater likelihood of excelling in their academic pursuits. These findings suggest that, beyond the independent mediating roles of SC and PMH, the potential chain mediating effect of these two factors in the relationship between PA and AA warrants attention. Exploring this chain mediating mechanism can provide deeper insights into the multifaceted pathways through which PA influences adolescents’ academic success.

The current study

This research is the first to investigate the chain mediation effect of SC and PMH on the link between PA and AA in adolescents. Building on previous empirical research, we constructed the theoretical model shown in Fig. 1 and proposed the following hypotheses:

-

H1: PA is positively correlated with adolescents’ AA.

-

H2: The role of SC as an independent mediator is evident in the link between PA and AA.

-

H3: The role of PMH as an independent mediator is evident in the link between PA and AA.

-

H4: PA enhances adolescents’ AA through the chain mediating effects of SC and PMH.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

This study adopted a cross-sectional quantitative survey design to examine the hypothesized chain mediation model linking PA, SC, PMH, and AA among Chinese adolescents. To minimize selection bias, ensure representativeness, and enhance the external validity and generalizability of the findings, this study employed a random sampling strategy for questionnaire distribution and data collection. Between September and December 2024, data were collected using the online platform Questionnaire Star (www.sojump.com) to examine the hypothesized model. Prior to participation, all respondents were clearly informed about the purpose of the study, and confidentiality of personal information was guaranteed. Participation was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Students from junior and senior high schools in China were randomly selected to ensure a representative sample. The research team coordinated with class teachers, who introduced the purpose and significance of the study to students during class sessions. Teachers then randomly selected students and distributed the questionnaire link via class communication platforms, allowing students to decide independently whether to participate.

A total of 465 questionnaires were collected. Inclusion criteria required participants to be current junior or senior high school students in China, able to understand and independently complete the questionnaire, and to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included incomplete responses, logical inconsistencies, severe physical or psychological conditions affecting normal study life, or recent participation in similar intervention studies. Based on these criteria, 7 questionnaires were deemed invalid due to incomplete responses or logical inconsistencies, resulting in a final valid sample of 458 participants. The demographic information is presented in Table 1. Among the respondents, 275 (60%) were male and 183 (40%) were female. Most participants were aged 13 to 18 years (87.1%), including 257 junior high school students (56.1%) and 201 senior high school students (43.9%).

Measurement instruments

The questionnaire was divided into two primary sections: the first collected participants’ demographic information, while the second gathered self-reported data on the key constructs. Validated scales were used to assess these constructs, with modifications made to suit the research context and objectives. In addition to demographic data, the questionnaire covered four key constructs: PA, SC, PMH, and AA.

Physical activity

Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Rating Scale-3 (PARS-3), revised by Liang37, which has been widely applied and validated in adolescent populations. The scale comprises three items evaluating PA intensity, duration, and frequency, each rated on a 5-point scale. For example, the frequency item asks, “How often do you engage in PA every month/week?” with options ranging from “less than once per month” (1 point) to “every day” (5 points). The total PA score is calculated using the formula: physical activity score = intensity score × (duration score − 1) × frequency score, resulting in a range from 0 to 100. Based on this score, participants are categorized into low (≤ 19 points), moderate (20–42 points), and high (≥ 43 points) physical activity levels38, a classification widely adopted in adolescent PA research to facilitate comparison across studies. In Liang37 validation study of the revised PARS-3, the scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.82, indicating acceptable reliability. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.761, further supporting its suitability as a concise yet effective tool for assessing adolescent PA. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.691, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), supporting the factor analysis approach in this study.

Self-concept

Self-concept was assessed using a 4-item scale developed by Schluchter, et al.39, which evaluates adolescents’ perceived competence in sports. Although the scale contains only four items, this concise design was chosen to reduce respondent burden in large adolescent samples while maintaining measurement precision. Schluchter, et al.39 reported robust psychometric properties of this scale, including satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77–0.79) and good structural validity confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis. The scale includes statements such as “I learn sports skills faster than my peers” and was rated on a 5-point Likert system from (1) “Strongly disagree” to (5) “Strongly agree.” In the present study, the scale demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.781, supporting its appropriateness as a concise yet reliable measure. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.785, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), supporting the factor analysis approach in this study. CFA results indicated a good model fit: χ²/df = 1.111, RMSEA = 0.016, GFI = 0.998, AGFI = 0.988, IFI = 0.999, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.999.

Physical and mental health

Physical and mental health scale adapted from Wang, et al.40 which included two dimensions: physical health and mental health. These dimensions measured adolescents’ overall physical well‑being and the frequency of negative feelings such as depression or despondency. Each dimension was assessed with one item, totaling two items (e.g., “Generally, how would you rate your health?”). Although the scale consists of only two items, this ultra‑brief design was intentional to minimize respondent burden and enhance completion rates in large adolescent samples. Importantly, similar brief self‑rated health measures have been validated in Chinese adolescent populations in SSCI‑indexed empirical studies. For example, Shi, et al.41 confirmed the validity of concise health items in a large‑scale survey of Eastern Chinese adolescents. In the present study, the scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.749. Because each dimension contained only one item, we could not calculate Cronbach’s α for each dimension separately. Therefore, we reported the overall internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.749. Furthermore, to verify the quality of the scale, we examined criterion-related validity. The results showed that the physical health item was significantly and positively correlated with PA (r = 0.281, p < 0.01), SC (r = 0.508, p < 0.01), and AA (r = 0.322, p < 0.01). Likewise, the mental health item was significantly correlated with PA (r = 0.227, p < 0.01), SC (r = 0.372, p < 0.01), and AA (r = 0.313, p < 0.01). These results align with theoretical expectations and support the measurement validity of the scale.

Academic achievement

Academic achievement was evaluated using adolescents’ most recent Chinese, mathematics, and English exam performance via a single-item scale adapted from prior studies3,42 (e.g., “What was the average score range of your last exams in Chinese, mathematics, and English?”). Participants first calculated the average score of the three subjects and then selected the corresponding score range based on the following 5-point scale: 1 = < 60%, 2 = 60–69%, 3 = 70–79%, 4 = 80–89%, 5 = ≥ 90%. Although this construct relies on just one item, the ultra-brief format was intentionally selected to simplify reporting, reduce cognitive burden, and minimize recall bias in large-scale youth surveys. Similar single-item academic achievement measures have been validated in Chinese adolescent populations and demonstrated strong criterion validity with objective exam scores43. In the present study, the scale showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.770), supporting its appropriateness and reliability for broad adolescent research.

Although some core variables in this study were measured using a small number of items (including single-item or two-item scales), this choice was based on established practices in adolescent survey research and the characteristics of our sample size. For medium-scale questionnaire surveys of this kind, brief scales can maintain acceptable reliability and validity while reducing participant response burden, improving completion rates, and minimizing recall bias. Prior validation studies in Chinese adolescent populations have also shown that these brief instruments exhibit high criterion validity with objective indicators (e.g., academic achievement, teacher evaluations) and demonstrate stable associations with theoretically related variables3,42,43,44. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that such simplified measurements may, to some extent, limit the ability to capture the full scope of the constructs.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 26. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and reliability and validity tests were performed for the measurement scales. Using PROCESS 4.0 Model 6, the analysis investigated how SC and PMH jointly mediated the link between PA and AA. Confidence intervals for the mediation effects of the main variables were derived through the Bootstrap method with 5000 resamples, strengthening the reliability of the results. Additionally, prior to multivariate analysis, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to ensure the reliability of the results and the appropriateness of the statistical methods.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

To verify the appropriateness of the construct structure, we conducted a CFA on all key latent variables in the study, including PA, SC, PMH and AA. The CFA was performed using AMOS 28.0 with the maximum likelihood estimation method, following the theoretical framework. This procedure aimed to test whether the empirical model reflected the expected dimensional configuration based on theoretical assumptions. Model fit indices are presented in Table 2. The results provide evidence that the specified model aligns well with the observed data, reflecting acceptable levels of model fit. All major fit statistics reached or were near the suggested cutoff values, indicating that the measurement structure aligns well with both theoretical assumptions and statistical requirements.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

According to the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis presented in Table 3, significant positive correlations were observed among PA, SC, PMH, and AA (p < 0.001, N = 458). These results suggest that moderate PA, higher levels of SC, and better PMH may contribute to improved AA among adolescents.

Mediation effect analysis

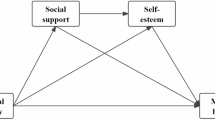

Controlling for gender, age, and grade, the results reveal a clear pattern: PA exerts a direct positive effect on SC, PMH, and AA. Moreover, PA enhances AA indirectly through PMH, confirming the mediating role of mental health. In contrast, SC does not directly predict AA, suggesting it does not mediate the PA–AA link. However, SC contributes to AA indirectly by improving PMH, highlighting PMH as a key psychological pathway in this model. Detailed results are presented in Table 4; Fig. 2.

The mediation analysis clarified the mechanisms linking PA and AA. PMH emerged as a significant mediator, accounting for 14.86% of the total effect. A sequential pathway through SC and PMH also contributed 8.86% to the total effect. This indicates that PA promotes AA not only directly but also indirectly through improved SC and enhanced PMH. In contrast, SC alone did not show a significant mediating effect. These results emphasize the important role of PMH, both on its own and in combination with SC, in explaining how PA influences AA. See Table 5 for detailed results.

Discussion

Focusing on the chain mediation of SC and PMH, this study examined how PA affects AA. The findings reveal that PA contributes to adolescents’ AA both directly and indirectly through the sequential mediating effects of SC and PMH. Adolescents who moderately engage in PA can improve their level of SC, promote PMH, and, in turn, enhance their academic performance. The proposed model provides new empirical evidence for understanding how PA impacts adolescents’ AA through psychological mechanisms, offering fresh perspectives for educators and policymakers.

PA was found to significantly and positively predict AA, supporting Hypothesis 1. Specifically, the direct effect of PA on AA was β = 0.241, accounting for 68.85% of the total effect. This medium effect size indicates that PA is not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful in predicting adolescents’ AA. This finding aligns with the results of Brown, et al.16, who analyzed data from a nationally representative sample of 13,677 U.S. adolescents and reported a significant positive correlation between the frequency of PA and AA. Their study revealed that adolescents who engaged in PA were more likely to report higher AA. Routine physical exercise plays a role in boosting adolescents’ cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, and processing speed, which are essential for academic performance45. According to self-concept theory, PA promotes a positive perception of one’s physical and mental capabilities, which enhances motivation and engagement in academic tasks, ultimately improving AA. Furthermore, PA stimulates the formation of neurons (neurogenesis) and blood vessels (angiogenesis)46. These biological changes enhance mental and emotional health, creating an optimal foundation for successful learning47. However, compared with the study by Brown, et al.16, the effect sizes observed in the present study were slightly higher. This difference may stem from variations in measurement methods: the PARS-3 scale used in this study captures both the intensity and duration of physical activity, whereas their study focused primarily on activity frequency. In addition, cultural background differences may also be an important factor. Physical activity in Chinese schools is typically more structured and regulated, and such organizational forms may, to some extent, strengthen the association between physical activity and academic performance. Therefore, incorporating PA into daily educational programs can offer adolescents opportunities for holistic development, enabling them to achieve superior academic performance.

The analysis revealed that SC did not act as a mediator in the link between PA and AA, rendering Hypothesis 2 unsupported. Specifically, the indirect effect of PA on AA through SC was β = 0.026, accounting for 7.43% of the total effect. Although the effect approached significance, the modest size of this pathway suggests that the role of SC in bridging PA and AA is likely context-dependent. This finding contradicts the study by Batista, et al.7, who reported that participation in PA significantly enhanced SC, which in turn positively predicted AA among Portuguese adolescents. The difference may reflect variations in cultural and educational contexts. According to self-concept theory, PA promotes positive self-perceptions that strengthen motivation and engagement in academic tasks. However, in the present sample, where adolescents may have less exposure to structured physical education or where family and school environments place limited emphasis on PA, the potential of PA to enhance SC may be reduced. Batista, et al.7 noted that in Portugal, PA programs are often designed to foster personal growth and social recognition, providing adolescents with opportunities to internalize positive experiences and strengthen their SC. In contrast, limited participation in PA and a lack of emphasis on its developmental value in the current context could explain why the mediating role of SC was not observed.

PMH was found to mediate the relationship between PA and AA, supporting Hypothesis 3. Specifically, the indirect effect of PA on AA through PMH was β = 0.052, accounting for 14.86% of the total effect. These findings are in agreement with those reported by Wang and Guo29 and Liu, et al.30, which highlighted that PA not only improves physical fitness but also contributes to psychological well-being, such as enhancing emotional regulation and reducing stress responses. This dual impact on PMH strengthens adolescents’ attention and increases their engagement and sense of accomplishment in academic activities5. As adolescents’ investment in academic endeavors increases, their AA improves, forming a positive feedback loop48. Thus, the benefits of PA extend beyond direct improvements in academic performance. Through its promotion of PMH, PA indirectly enhances AA. Unlike direct effects, this mediated relationship underscores the indirect benefits of PA, suggesting that educators and policymakers should view PA as a vital component of adolescent education, not only for physical development but also for supporting PMH and academic success. However, compared with some Western studies, the indirect effect observed in this study was relatively small. Cultural and educational context differences may partly influence the extent to which PA fosters PMH. In settings with limited sports resources, scarce extracurricular activity opportunities, or high academic pressure, the effectiveness of PA in improving mood and alleviating stress may be constrained, thereby weakening its indirect effect on AA through the enhancement of PMH.

SC and PMH were found to play a chain mediation role in the relationship between PA and AA, supporting Hypothesis 4. Specifically, the indirect effect of PA on AA through SC and PMH was β = 0.031, accounting for 8.86% of the total effect. This chain mediation model offers new insights into the relationship between PA and AA. Specifically, PA enhances adolescents’ SC, boosting their perception of their abilities and self-confidence, which in turn promotes their PMH23. This improvement stimulates higher learning motivation and a positive academic attitude49, ultimately contributing to improved academic performance. This enhanced self-perception further improves adolescents’ PMH by reducing anxiety and stress, increasing focus, and promoting learning engagement. These psychological and emotional improvements provide a strong foundation for better academic performance47. By unveiling the chain mediation mechanism, this study demonstrates that PA not only directly contributes to AA but also indirectly enhances academic performance through the combined effects of improved SC and PMH. This model provides theoretical support for educators and policymakers, highlighting the indispensable role of appropriate PA in the holistic development of adolescents. It is noteworthy that the chain mediation effect observed in this study was lower than that reported in some Western studies. This may be related to the relatively weaker association between PA and SC in the current sample, which in turn limited subsequent improvements in PMH. In addition, factors such as cultural background, frequency of participation in physical activity, and the emphasis placed on physical education in schools may influence the strength of this chain mediation pathway in different contexts.

Implications

Theoretical implications

By utilizing an innovative chain mediation framework, this study examines the intermediary roles of SC and PMH in linking PA to AA. The model provides new empirical evidence on how PA indirectly facilitates the improvement of adolescents’ academic performance, addressing the theoretical gap in previous studies regarding the complex interplay of psychological factors. Additionally, this research expands the theoretical framework of PA in the field of educational psychology. From the perspective of chain mediation, this study integrates SC and PMH into the theoretical system linking PA and AA. It demonstrates that engaging in positive PA not only enhances adolescents’ SC but also improves their PMH. These improvements lead to increased focus and engagement in learning, thereby indirectly boosting academic performance. This finding offers new theoretical support for educators and policymakers, emphasizing the dual impact of PA on adolescents’ physical and mental development as well as AA. It highlights the importance of incorporating PA into the educational process to foster both holistic development and academic success among adolescents.

Practical implications

The findings of this study hold significant value for educational practices, providing schools and educational policymakers with concrete guidance for fostering the holistic development of adolescents. The results indicate that PA not only serves as a means of enhancing physical fitness but also contributes to AA by improving SC and promoting PMH, thereby providing robust support for adolescents’ academic growth.

From the perspective of schools and educational administrators, schools can increase the proportion of PA in daily curricula to facilitate students’ comprehensive development in terms of PMH and AA50. Additionally, educational administrators can design more targeted PA programs, such as personalized exercises or team-based activities, to help adolescents enhance their SC, build self-confidence, and foster a sense of belonging.

From the students’ perspective, PA offers valuable opportunities for self-recognition and personal growth. Students can set individual exercise goals, such as improving their running speed or accomplishing specific fitness tasks, and work toward achieving them. This process helps them gradually strengthen their self-efficacy and sense of accomplishment. By continuously challenging themselves and overcoming difficulties, students can establish positive beliefs about their abilities, which in turn enhances their SC.

Moreover, parents and communities can encourage adolescents to participate in PA during their leisure time, creating a healthier environment for growth and fostering positive and healthy lifestyles51. By collaboratively engaging schools, families, and communities in diverse PA, the holistic promotion of adolescents’ PMH can be achieved. This multi-party educational ecosystem ensures sustained and comprehensive development for adolescents in both academic and health domains.

Limitations and future research

Although this study revealed the chain mediating role of SC and PMH in the relationship between PA and AA, it has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits our ability to make causal inferences about the relationships among PA, SC, PMH, and AA, as the temporal ordering of these variables remains unclear. In addition, the relatively small sample size (N = 458) may have reduced the statistical power to detect smaller effect sizes and affected the robustness of the results, suggesting the need for future studies to adopt larger and more representative samples to enhance generalizability and ensure stability across subgroups. Furthermore, all constructs, including AA, were measured using self-reported data, which may introduce potential biases such as social desirability and recall bias. While previous research supports the validity of self-reported academic performance among adolescents, it may not fully capture objective academic outcomes or health status. At the same time, some core variables in this study (e.g., AA and PMH) were measured using single-item or few-item scales, which may have, to some extent, limited the depth of construct measurement and increased the risk of measurement error. Future research should consider incorporating objective data sources, such as school records, teacher ratings, or device-based tracking, as well as multi-informant assessments, to improve measurement validity. Finally, as this study focused primarily on Chinese adolescents, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other age groups or cultural contexts. Future studies could include participants from diverse populations and cultural backgrounds to test the universality of these results.

Conclusion

This research sought to examine the influence of PA on adolescents’ AA and investigate the chain mediation roles of SC and PMH within this relationship. Using the Questionnaire Star platform, 458 valid responses were collected, and hypotheses 1, 3, and 4 were confirmed. PA showed a significant direct effect on AA (β = 0.241), while physical-mental health and the sequential pathway through SC and physical-mental health accounted for 14.86% and 8.86% of the total effect, respectively. These findings indicate that PA contributes to improved academic outcomes not only directly but also indirectly through enhanced self-perception and psychological well-being. This study extends educational psychology research by revealing the combined roles of SC and physical-mental health in linking PA to academic success. It also provides theoretical guidance for integrating PA into school curricula to promote adolescents’ holistic development. Future research should consider longitudinal designs and objective measurements, such as psychological assessments, activity tracking devices, or teacher evaluations, to strengthen the evidence base for these findings.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Dias, P., Veríssimo, L., Carneiro, A. & Figueiredo, B. Academic achievement and emotional and behavioural problems: The moderating role of gender. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 27, 1184–1196. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211059410 (2022).

Hattie, J. & Hattie, J. A. C. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. 1st ed. (2009).

Shao, Y. H., Kang, S. M., Lu, Q., Zhang, C. & Li, R. X. How peer relationships affect academic achievement among junior high school students: The chain mediating roles of learning motivation and learning engagement. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01780-z (2024).

López-Sánchez, M. et al. Academic performance and social networks of adolescents in a Caribbean city in Colombia. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01299-9 (2023).

Zhang, X. H., Zhang, D. Q., Yang, X. Y. & Chen, S. T. Cross-sectional association between frequency of vigorous physical activity and academic achievement in 214,808 adolescents. Front. Sports Active Living https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2024.1366451 (2024).

Muwanguzi, M. et al. Exploring adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among Ugandan university students: its associations with academic performance, depression, and suicidal ideations. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01044-2 (2023).

Batista, M. et al. Exercise influence on self-concept, self-esteem and academic performance in middle-school children. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala 14, 369–398. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/14.4Sup1/678 (2022).

Muluneh, B. N. & Bejji, T. D. Differences in behavior problems and academic achievement between students with and without health impairments in Ethiopia. Cogent Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2024.2309745 (2024).

Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J. & Stanton, G. C. Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 46, 407–441 (1976).

Marsh, H. W. & Martin, A. J. Academic self-concept and academic achievement: Relations and causal ordering. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 59–77 (2011).

Dempsey, C., Devine, R., Fink, E. & Hughes, C. Developmental links between well-being, self-concept and prosocial behaviour in early primary school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 425–440 (2024).

Liu, M., Wu, L. & Ming, Q. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents?. Evidence from a meta-analysis. PloS one 10, e0134804 (2015).

Lubans, D. et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: a systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 138 (2016).

Babic, M. J. et al. Physical activity and physical self-concept in youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 44, 1589–1601 (2014).

Crichton, M., Bigelow, H. & Fenesi, B. Physical activity and mental health in children and youth: Clinician perspectives and practices. Child Youth Care Forum 53, 981–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-023-09782-5 (2024).

Brown, D. M. Y. et al. Interactive associations between physical activity and sleep duration in relation to adolescent academic achievement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315604 (2022).

Frikha, M. Extracurricular physical activities and academic achievement in Saudi female physical education students: the mediating effect of motivation, enjoyment, and BMI. Front Psychol. 16, 1420286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1420286 (2025).

Nagy, G. et al. The development of students’ mathematics self-concept in relation to gender: Different countries, different trajectories?. J. Res. Adolesc. 20, 482–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00644.x (2010).

Fernández-Bustos, J. G., Infantes-Paniagua, A., Cuevas, R. & Contreras, O. R. Effect of physical activity on self-concept: Theoretical model on the mediation of body image and physical self-concept in adolescents. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01537 (2019).

Feng, X. L., Wang, J. L. & Rost, D. H. Subject-specific interests and subject-specific self-concepts. Zeitschrift Fur Padagogische Psychologie 37, 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000344 (2023).

González-Valero, G. et al. Analysis of self-concept in adolescents before and during COVID-19 lockdown: Differences by gender and sports activity. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187792 (2020).

Palenzuela-Luis, N., Duarte-Clíments, G., Gómez-Salgado, J., Rodríguez-Gómez, J. A. & Sánchez-Gómez, M. B. International comparison of self-concept, self-perception and lifestyle in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604954 (2022).

Ferrari, G. et al. Association of physical activity, muscular strength, and obesity indicators with self-concept in Chilean children. Nutr. Hosp. 39, 1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.20960/nh.04061 (2022).

Dapp, L. C. & Roebers, C. M. The mediating role of self-concept between sports-related physical activity and mathematical achievement in fourth graders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152658 (2019).

Galán-Arroyo, C., Mayordomo-Pinilla, N., Olivares, P. R. & Rojo-Ramos, J. Physical fitness and self-concept in students of different ages in Extremadura (Spain). Sportis-Sci. Tech. J. School Sport Phys. Educ. Psychomotricity 10, 377–400. https://doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2024.10.2.10548 (2024).

Hays, R. D., Spritzer, K. L., Schalet, B. D. & Cella, D. PROMIS®-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual. Life Res. 27, 1885–1891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1842-3 (2018).

Smith, P. J. & Merwin, R. M. Annual Review of Medicine, Vol. 72 (ed. Klotman, M. E.) 45–62 (2021).

Sabo, A., Kuan, G. & Kueh, Y. C. Structural relationship of the social-ecological factors and psychological factors on physical activity. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01825-3 (2024).

Wang, T. J. & Guo, C. B. Inverted U-shaped relationship between physical activity and academic achievement among Chinese adolescents: On the mediating role of physical and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084678 (2022).

Liu, G. Q., Li, W. J. & Li, X. T. Striking a balance: how long physical activity is ideal for academic success? Based on cognitive and physical fitness mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1226007 (2023).

Zhang, J. L., Zheng, S. & Hu, Z. Z. The effect of physical exercise on depression in college students: The chain mediating role of self-concept and social support. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841160 (2022).

Ferro, M. A., Dol, M., Patte, K. A., Leatherdale, S. T. & Shanahan, L. Self-concept in adolescents with physical-mental comorbidity. J. Multimorbidity Comorbidity https://doi.org/10.1177/26335565231211475 (2023).

Galán-Arroyo, C., Da Silva, M. A. B. & Rojo-Ramos, J. Self-concept in physical education for post-pandemic school health improvement. Revista Electronica Interuniversitaria De Formacion Del Profesorado 27, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.581361 (2024).

Harrigan, M., Mulrennan, S., Jessup, M., Waters, P. & Bennett, K. Who am I? Self-concept in adults with cystic fibrosis: Association with anxiety and depression. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10023-7 (2024).

Delgado-Floody, P., Soto-García, D., Caamaño-Navarrete, F., Carter-Thuillier, B. & Guzmán-Guzmán, I. P. Negative physical self-concept is associated to low cardiorespiratory fitness, negative lifestyle and poor mental health in Chilean schoolchildren. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132771 (2022).

Halat, D. H. et al. Exploring the effects of health behaviors and mental health on students’ academic achievement: a cross-sectional study on lebanese university students. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16184-8 (2023).

Liang, D. Stress level and its relation with physical activity in higher education. Chin. Ment. Health J 8, 5–6 (1994).

Li, C. Q., Hu, Y. B. & Ren, K. Physical activity and academic procrastination among Chinese university students: A parallel mediation model of self-control and self-efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106017 (2022).

Schluchter, T., Nagel, S., Valkanover, S. & Eckhart, M. Correlations between motor competencies, physical activity and self-concept in children with intellectual disabilities in inclusive education. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 36, 1054–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13115 (2023).

Wang, H., Yang, Y., You, Q. Q., Wang, Y. W. & Wang, R. Y. Impacts of physical exercise and media use on the physical and mental health of people with obesity: Based on the CGSS 2017 survey. Healthcare. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091740 (2022).

Shi, G. H. et al. 24-hour movement behaviours and self- rated health in Chinese adolescents: a questionnaire-based survey in Eastern China. PeerJ 11, 16. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16174 (2023).

Livermore, M., Duncan, M. J., Leatherdale, S. T. & Patte, K. A. Are weight status and weight perception associated with academic performance among youth?. J. Eat. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00329-w (2020).

Liu, F., Li, H., Sun, H., Wang, P. & Qin, M. Adolescents’ academic achievement and meaning in life: the role of self-concept clarity. Front. Psychol. 16, 1596061 (2025).

Scott, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Plotnikoff, R. C. & Lubans, D. R. Reliability and validity of a single-item physical activity measure for adolescents. J. Paediatr. Child Health 51, 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12836 (2015).

Zhang, M. et al. The association between physical activity and subjective well-being among adolescents in southwest China by parental absence: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04982-8 (2023).

Mori, T. et al. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors moderate the association between physical activity and relative age effect: a cross-sectional survey study with Japanese adolescents. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14052-5 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Psychological symptoms are associated with screen and exercise time: a cross-sectional study of Chinese adolescents. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09819-7 (2020).

Tannoubi, A. et al. Modelling the associations between academic engagement, study process and grit on academic achievement of physical education and sport university students. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01454-2 (2023).

Gut, V., Schmid, J., Imbach, L. & Conzelmann, A. Stability of context in sport and exercise across educational transitions in adolescence: hello work, goodbye sport club?. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12471-4 (2022).

Mateo-Orcajada, A., Abenza-Cano, L., Molina-Morote, J. M. & Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. The influence of physical activity, adherence to Mediterranean diet, and weight status on the psychological well-being of adolescents. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01906-3 (2024).

Xiang, H. Y. et al. Association between healthy lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life among Chinese adolescents: the moderating role of gender. Health Qual. Life Outcomes https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02201-2 (2023).

Funding

This work was sponsored in part by the Basic Research Support Program for Outstanding Young Teachers of Provincial Undergraduate Universities in Heilongjiang Province (YQJH2023110).2024 Heilongjiang Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research General Project (SJGYB2024533);2024 Heilongjiang Province Higher Education Society Project (24GJZXD027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Wenwen Pan, Long Xu; Methodology: Wenwen Pan; Formal analysis and investigation: Wenwen Pan; Writing - original draft preparation: Wenwen Pan; Review and editing: Wenwen Pan; Supervision: Hongbao Zhang. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The researchers confirms that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable when human participants are involved (e.g., Declaration of Helsinki or similar). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qiqihar University. The participants received oral and written information and provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, W., Zhang, H. & Xu, L. Association between physical activity and academic achievement in adolescents mediated by self-concept and physical and mental health. Sci Rep 15, 33561 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18559-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18559-w