Abstract

Readmissions following strokes are a significant concern due to their association with adverse outcomes. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services regard hospital readmissions as a measure of suboptimal hospital care and have made reducing readmission rates a national healthcare reform goal. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to identify factors associated with 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year ischemic stroke readmissions. We reviewed the databases PubMed and Web of Science for English-language studies on stroke readmissions published between January 1, 2000, and February 5, 2024. A total of 135 studies from 18 countries met the inclusion criteria. Higher 30-day readmissions were linked to advanced age, insurance type, employment status, socioeconomic disadvantage, discharge destination, and conditions such as heart failure and diabetes. Reduced 30-day readmissions were associated with effective discharge planning, post-primary care visits, and thrombolytic therapy administration. Weekend admissions and the COVID-19 period were not significant contributing factors. Our meta-analysis on 30-day readmissions in the U.S. found increased odds with atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.12–1.36]), and cancer (OR, 1.50 [95% CI, 1.19–1.89]), while discharge to home (OR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.55–1.02]) and private insurance (OR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.66–0.75]) decreased the odds. Advanced age, comorbidities, and discharge planning impacted 90-day readmissions, while 1-year readmissions were influenced by advanced age, discharge location, functional independence, and diseases including diabetes and coronary artery disease. The study highlights the importance of hospital discharge procedures and follow-up care as modifiable factors for mitigating the risk of readmission in stroke patients. Prioritization in care transition enhancements and proper discharge planning for at-risk patients could help improve stroke readmission rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hospital readmissions pose a significant challenge within the healthcare landscape, with profound implications for patient outcomes1 and healthcare costs2. In the United States, annual expenditures on hospital readmissions exceed $50 billion, with Medicare bearing a substantial portion of these costs2. As a crucial quality metric for healthcare institutions, hospital readmissions can indicate potential issues at discharge or post-hospital care deficiencies, prompting national healthcare reform initiatives to reduce readmission rates by enhancing patient care quality3. Research has shown that 1-year readmission rates for stroke patients can vary widely, ranging from 30–62.2%[3], with approximately 16% experiencing two or more readmissions within 30 days of their initial stroke incident4. Patients with stroke readmissions face elevated mortality risks, increased disability levels, and greater healthcare resource utilization compared to those without readmissions1.

The complexity of stroke hospital readmissions lies in its multifaceted nature, encompassing patient, organizational, and environmental factors. While previous reviews have explored and found common associated factors such as advanced age, they were limited by a small number of studies (10–24 studies) leading to narrow scopes of inquiry, typically covering only a fraction of potential influences3,5,6,7. Consequently, the narrower scope of these reviews left less frequently studied or emerging predictors of stroke readmission insufficiently explored. Of the four existing reviews on stroke readmissions, three (Litchman et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2016; Rao et al., 2016) were published nearly a decade ago, and the most recent (Deng et al., 2021) focused solely on 30-day readmissions3,5,6,7. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review in nearly ten years to examine 90-day and 1-year readmissions alongside 30-day readmissions. Conflicting findings for 30-day readmission factors, such as atrial fibrillation reported as significant by Deng et al. (2021) but not by Zhong et al. (2016) and coronary artery disease, found significant by Zhong et al. (2016) but not by Deng et al. (2021), further underscore the need for a more comprehensive investigation5,7. To address these gaps, our research conducts a rigorous systematic review approach, synthesizing findings from over 100 studies across 18 countries to examine 132 factors associated with 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year ischemic stroke readmissions. Additionally, a meta-analysis was performed to identify factors specifically associated with 30-day readmissions in the United States.

Method

Literature search

Our literature review on factors associated with ischemic stroke readmissions involved a systematic search of PubMed and Web of Science for studies published between January 1, 2000, and February 5, 2024. PubMed was chosen for its extensive biomedical literature, making it a valuable resource for stroke readmission topics. Web of Science was selected for its multidisciplinary scope and citation tracking capabilities. We conducted an electronic search using predefined search terms in article titles or abstracts, specifically “Readmission” and “Stroke” or “Cerebral Infarction” or “Brain Infarction.” In PubMed, our search query was structured as follows: “readmission [Title/Abstract] AND (stroke [Title/Abstract] OR ‘cerebral infarction’ [Title/Abstract] OR ‘brain infarction’ [Title/Abstract]).” In Web of Science, we used the following query format: “readmission AND stroke (Topic) OR readmission AND ‘cerebral infarction’ (Topic) OR readmission AND ‘brain infarction’ (Topic).”

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies focused on adults aged 18 years and older and examined associated factors for ischemic stroke or stroke readmissions within a 30-day, 90-day, or 1-year timeframe. Studies on stroke readmissions were included, as ischemic stroke is the most common stroke subtype. The exclusion criteria encompassed non-English studies; studies that excluded ischemic stroke; those focused on stroke prevention interventions such as carotid artery stenting (CAS) or carotid endarterectomy (CEA); studies examining readmissions solely related to specific patient sub-groups such as individuals with diabetes; trend analyses, literature reviews, meta-analyses, opinion pieces, abstracts, and posters; studies that did not stratify stroke in their analysis when other diseases were involved; studies not stratifying stroke readmission and mortality; and investigations into postpartum or preoperative stroke. When studies provided data stratified by stroke subtypes, we prioritized ischemic stroke data. If stroke subtypes were reported but not stratified, we confirmed that ischemic stroke was the most common subtype represented. Studies with a timeframe of 28 to 31 days were categorized as 30-day readmission studies. The outcome measures were defined as factors associated with readmission within a 30-day, 90-day, or 1-year timeframe.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Identified studies were imported into Microsoft Excel to create the initial dataset. Duplicate records and non-English articles were removed. The remaining titles and abstracts were screened by EM using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text eligibility concerns were reviewed independently by NH, VA, and ZR, with discrepancies resolved through discussion and consensus. No automation tools were used in the selection process.

Risk of bias and quality assessments were performed by EM using the appropriate tool for each study design. Oversight and guidance were provided by coauthors with relevant methodological and clinical expertise (NH, ZR, VH, SZ, and ZT). Discrepancies were resolved through group discussion and consensus. For quality assessment, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for non-randomized studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies, and the Modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Modified NOS) for cross-sectional studies (refer Tables S4–S11, provided in full in the supplementary information).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Study characteristics, including country of origin, readmission rate range, mean, and standard deviation, were reported. Studies lacking explicit readmission rates were excluded from calculations of the mean and standard deviation of readmission rates8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. A pie chart depicting the number of studies per country is provided. Tables organized by readmission timeframe, categorizing the studies by design, sample size, readmission rate, readmission type, population, stroke type, country, model used, and identified factors, are included in the supplementary information (see Tables S1–S3).

A meta-analysis of 30-day ischemic stroke readmission factors in the U.S. was performed using R Studio with the metafor package. Studies were selected from the final dataset if they reported 30-day readmission factors in U.S. populations. Only factors investigated in at least five independent studies were included in the quantitative synthesis; this threshold was applied to ensure sufficient data for meaningful meta-analysis. Log odds ratios for 30-day readmissions were used for forest plots, with reported odds ratios converted where necessary. For studies that lacked odds ratios but provided frequency data, log odds ratios were manually calculated. A random-effects model accounted for heterogeneity, assessed using Chi-squared and I² statistics. For studies with substantial heterogeneity (P ≤ 0.10 and I² > 50%) where the source of heterogeneity could not be identified, pooled estimates were presented but interpreted with caution. Publication bias was evaluated using inverted funnel plots and Egger’s test.

Results

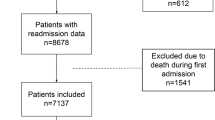

In our systematic search across PubMed and Web of Science databases, we initially identified 2,922 relevant studies. After removing 37 non-English studies and 1,072 duplicates, our dataset was reduced to 1,813 unique studies. Abstract screening excluded 1,675 studies due to incorrect disease focus, literature reviews, meta-analyses, or opinion pieces, leaving 138 potentially eligible studies for full-text retrieval. Upon further review, we excluded two studies involving participants under 18 years old20,21 and another study exclusively focused on subtypes of ischemic stroke1 resulting in a final inclusion of 135 studies. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram.

Descriptive characteristics of the included studies

Of the analyzed studies, 104 (70%) focused on 30-day readmissions1,4,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,17,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114, 21 (14%) on 90-day readmissions10,18,24,36,71,73,86,91,94,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126, and 23 (16%) on 1-year readmissions16,35,60,66,72,116,121,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142 (some studies examined more than one readmission timeframe). Publication trends indicated a notable increase, with seven studies published between 2000 and 2010 and 128 published between 2011 and 2024. The study spanned 18 countries, with the United States leading (84), followed by Taiwan (10), China (9), Australia (7), Denmark (4), and Sweden (3). Other countries, including Canada, England, Japan, Norway, Singapore, and South Korea, contributed 2 studies each, while France, Israel, Italy, Malaysia, Portugal, and Turkey each had 1 study (see Fig. 2).

Readmission rates

The 30-day readmission rates ranged from 1.7 to 28.8% (mean 11.0%, SD = 4.2%), 90-day readmission rates ranged from 8.6 to 31.5% (mean 19.2%, SD = 6.4%), and 1-year readmission rates varied between 11.6 and 67.0% (mean 40.6%, SD = 13.8%). The 30-day readmission rates varied across different countries, with the United States rates ranging from 2.9 to 21.0%. In comparison, readmission rates in other countries were 5.0–15.1% in Australia, 7.0–28.8% in China, 9.1–11.5% in Denmark, and 8.1–15.5% in Taiwan.

Factors associated with 30-day readmissions

Examined readmission factors can be grouped into seven categories: sociodemographic, discharge location, patient social behavior, hospital level, chronic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, complex conditions, and stroke-related factors. Sociodemographic factors associated with increased 30-day readmissions included older age, which was significant in 16 studies: 15 of good quality1,25,35,48,49,57,68,76,78,83,84,93,94,99,111 and one of moderate quality106. Reliance on public health insurance (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid) or self-payment was significant in 11 studies: nine of good quality37,38,41,64,80,83,90,101,111 and two of moderate quality61,63. Unemployment or retirement was significant in two good quality studies66,101, and socioeconomic disadvantage status was significant in three good quality studies37,83,84.

Discharge location and hospital level factors associated with significantly higher readmission rates included discharge to a nursing home (four good quality studies)38,53,64,83; discharge to a rehabilitation center (five good quality studies)34,38,53,64,83; care from a neurologist (three good quality studies)15,93,108; urban hospital settings (four good quality studies)35,64,67,76; and patient transfers from hospitals or emergency departments (two good quality studies)37,84. Comorbidities significantly associated with elevated readmission rates included atrial fibrillation (two good quality studies)83,93, heart failure (seven good quality studies)42,76,78,80,83,93,101, and peripheral vascular disease (three good quality studies)1,76,83.

Stroke-related factors significantly associated with higher readmission rates included feeding tube presence (five good quality studies)1,34,42,64,68; intracerebral hemorrhage (five good quality studies)25,34,35,84,111; subarachnoid hemorrhage (two good quality studies)25,35; a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score between 5 and 23 (six good quality studies)35,38,64,65,81,93; and medical complications during hospitalization (two good quality studies)59,102; a history of more than two prior hospitalizations (four good quality studies)57,68,101,105, and low functional independence (seven high quality studies)29,39,53,59,73,101,103. Conversely, effective discharge planning, supported by two good quality studies92,107, three moderate quality studies36,54,98, and two low quality studies70,97, thrombolytic therapy (two high quality studies)38,83, and post-primary care visits (two high quality studies)50,71 were significantly linked to lower readmission rates. Notably, factors such as weekend admissions58,84,85, tobacco use23,57,83,99, chronic liver disease78,80,83, obesity57,80,83,93,142, and the COVID-19 period44,55 showed no significant impact on 30-day readmissions. The Fig. 3 below represents only those associated factors examined in at least five studies.

Meta-analysis results

We conducted a meta-analysis on factors associated with 30-day readmissions in the United States (Figs. 4 and 5). Our findings indicate that the odds of readmission increased with the presence of atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.12–1.36]), cancer (OR, 1.50 [95% CI, 1.19–1.89]), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.15–1.26]), congestive heart failure (OR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.22–1.52]), coronary artery disease (OR, 1.61 [95% CI, 1.24–2.10]), dementia (OR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.12–1.79]), diabetes (OR, 1.19 [95% CI, 1.12–1.26]), peripheral vascular disease (OR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.13–1.45]), and seizure disorder (OR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.04–1.18]).

Conversely, certain factors were associated with decreased odds of readmission: administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) (OR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.89–0.95]), having private insurance compared to other types of insurance (OR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.66–0.75]), being White compared to other races (OR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.84–0.98]), and hypertension (OR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.88–0.97]).

The following factors were not significantly associated with readmissions: being female (OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.98–1.03]), depression (OR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.93–1.20]), dyslipidemia (OR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.57–1.05]), dysphagia (OR, 1.30 [95% CI, 0.97–1.75]), prior stroke (OR, 1.45 [95% CI, 0.99–2.10]), having ischemic stroke as the stroke type (OR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.90–1.06]), and discharge to home compared to other locations (OR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.55–1.02]). Figures 4 and5 present the forest plot findings, with additional panels included in the supplementary information as Figure S1. Figure S2 shows the inverted funnel plots, and the results of Egger’s test are also included in the supplementary information. Publication bias was ruled out through Egger’s test and the inverted funnel plots.

Factors associated with 90-day readmissions

For 90-day readmissions, advanced age115,120,125,126, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)118,120, lower functional independence73,115,116,122, and prior hospitalizations36,120 correlated with increased readmission rates. Conversely, effective discharge planning86,91,119 was linked to reduced readmissions during this timeframe.

Factors associated with 1-year stroke readmissions

Older age35,72,128,131,132,133,136,139,141, lower income35,66,132, discharge to a rehabilitation center121,138, prior stroke136,138, diabetes72,129,131, high comorbidity burden (indicated by a high Charlson Comorbidity Index)35,60,132,139, prolonged length of stay35,72,129,136,141, non-ischemic stroke types35,60, lower functional independence128,129,136,138,139, and medical complications during the index hospitalization136,139 were associated with increased 1-year readmissions. Conversely, discharges to home129,134,139 and higher hospital rankings35,141 were linked to reduced 1-year readmission rates.

Factors associated with both 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year stroke readmissions

Advanced age1,25,35,48,49,57,68,72,76,78,83,84,93,94,99,106,111,115,120,125,126,128,131,132,133,136,139,141, reduced functional independence29,39,53,59,73,101,103,116,122,128,129,136,138,139, high comorbidity burden (CCI)35,60,78,90,132,139, and prior hospitalizations/ED visits36,57,60,68,101,105,120 were associated with increased readmission rates at 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year intervals.

Discussion

Our study identified a multitude of factors contributing to 30-day stroke readmissions, ranging from socio-demographic variables to clinical indicators and healthcare system-related factors. Older age, reliance on public health insurance, non-home discharge locations, neurologist care, multiple comorbidities, and low functional independence at discharge were associated with increased readmissions. Conversely, effective discharge planning, thrombolytic therapy administration, and post-primary care visits were linked to lower readmission rates, while tobacco use, obesity, weekend admissions, and the COVID-19 period showed no significant impact on 30-day readmissions. In cases of conflicting associated factors, our meta-analysis found that atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.12–1.36]) and coronary artery disease (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.24–2.10) significantly increased the odds of 30-day readmissions in the United States. Our results also found that dyslipidemia (OR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.57–1.05]) and gender (OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.98–1.03]) were non-significant factors in the United States, consistent with the conclusions of Deng et al.7.

Moreover, we found that the average 30, 90, 365-day readmission rates were 11.0%, 19.2%, and 40.6% which are similar to other studies3,5,7. The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year readmissions rates had wide ranges which can be explained by a variety of things particularly like different patient populations, sample sizes, and study types. Hospitals vary in the demographic characteristics of their patients, the types of health conditions they treat, and the prevalence of social risk factors such as food insecurity, housing instability, and low income. Research has shown that adjusting for these social risk factors significantly impacts hospital performance evaluations and helps reduce disparities in Medicare penalties143. Since 2019, Medicare has accounted for these factors by comparing each hospital’s readmission rate to that of peer institutions143,144. Hospitals are penalized only if their risk-adjusted readmission rate exceeds the median rate of their peer group, with adjustments made for patient age, sex, and comorbidities143,144.

Contextualizing these findings within the broader healthcare landscape unveils the pivotal role of resource allocation, policy interventions, and patient engagement strategies in mitigating readmission risks. Effective discharge planning, highlighted as a cornerstone strategy, emphasizes the importance of seamless care transitions and robust post-discharge support mechanisms. Effective discharge planning also necessitates clear communication of discharge plans, proactive scheduling of follow-up appointments, and coordination of therapies tailored to individual patient needs23,50,71,92,98. Particularly for high-risk patient cohorts, such as older individuals, those with complex medical histories, and patients treated by neurologists (likely due to the intricate nature of cases they oversee)15,42,93 personalized care coordination emerges as paramount for reducing risk of readmission.

Beyond the confines of hospital walls, the imperative for comprehensive coordinated care extends to diverse care settings, including nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and home health care services. Early post-discharge follow-ups, coupled with empathetic communication54 and patient education initiatives51 emerge as critical interventions in bolstering patient engagement and reducing adverse outcomes. A casual and optimistic communication style, especially regarding expected length of stay, has proven to be more effective in engaging patients and reducing discharge against medical advice incidents100. Additionally, empowering patients through lifestyle modifications114 and early rehabilitation interventions holds promise in mitigating readmission risks and fostering functional independence24. While high-intensity physical therapy is the preferred and recommended approach, low-intensity physical therapy also demonstrated a significant reduction in readmission rates for patients who received it as compared to those who did not24.

In navigating the challenge of high readmission rates, it is important to adopt a multifaceted approach. This includes enhancing discharge planning protocols, conducting rigorous patient risk stratification, evaluating the nurse working environment (as improved environments have been shown to decrease readmission rates57, and continually assessing care delivery processes. Embracing a culture of quality improvement and benchmarking against best practices can further catalyze efforts to optimize care delivery and enhance patient outcomes in stroke management.

Future directions

Current research on readmissions primarily emphasizes patient-level factors and care transitions as a key hospital-level factor. However, few studies have explored what distinguishes hospitals with lower stroke readmission rates. Future research should focus on additional hospital-level factors to identify strategies that could further reduce readmission rates, beyond improving care transitions and nursing work environments.

Limitations

While this comprehensive review aimed to identify factors influencing 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year stroke readmissions, several limitations should be noted. First, because the search was finalized in February 2024, more recent studies may not have been captured. Second, methodological heterogeneity among included studies may have introduced variability in the findings and their interpretation. Third, the overrepresentation of studies from the United States may limit the generalizability of our conclusions to a broader international context. Finally, restricting inclusion to English-language, peer-reviewed publications may have introduced publication and language bias, potentially excluding relevant studies published in other languages and favoring those with positive findings.

Conclusion

In summary, our analysis of 135 publications highlights diverse factors influencing 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year ischemic stroke readmissions, including sociodemographic characteristics, clinical conditions, and healthcare system elements. Key contributors to increased 30-day readmissions include older age, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, depression, and higher NIHSS scores. In contrast, effective discharge planning, post-primary care visits, and thrombolytic therapy administration reduce readmission rates. These modifiable factors present opportunities to reduce readmission for ischemic stroke patients.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper and its supplementary materials. Additional raw data files in alternative formats can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bjerkreim, A. T. et al. The impact of ischaemic stroke subtype on 30-day hospital readmissions. Stroke Res. Treat. 2018, 7195369. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7195369 (2018).

Quality AoHRa. Overview of Clinical Conditions With Frequent and Costly Hospital Readmissions by Payer. (2021). https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb278-Conditions-Frequent-Readmissions-By-Payer-2018.jsp#first

Lichtman, J. H. et al. Predictors of hospital readmission after stroke: a systematic review. Stroke Nov. 41 (11), 2525–2533. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.599159 (2010).

Nahab, F. et al. Avoidable 30-day readmissions among patients with stroke and other cerebrovascular disease. Neurohospitalist Jan. 2 (1), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874411427733 (2012).

Zhong, W., Geng, N., Wang, P., Li, Z. & Cao, L. Prevalence, causes and risk factors of hospital readmissions after acute stroke and transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci Aug. 37 (8), 1195–1202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2570-5 (2016).

Rao, A., Barrow, E., Vuik, S., Darzi, A. & Aylin, P. Systematic review of hospital readmissions in stroke patients. Stroke Res. Treat. 2016, 9325368. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9325368 (2016).

Deng, Z. et al. Risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients with ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10 (10), 11083–11105. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2884 (Oct 2021).

Cerullo, M. et al. Association between hospital private equity acquisition and outcomes of acute medical conditions among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open Apr. 1 (4), e229581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9581 (2022).

Gentile, C., Stein, L. & Dhamoon, M. S. Alcohol-Related hospital encounters trigger thrombotic and hemorrhagic vascular events. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Nov. 28 (11), 104395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104395 (2019).

Hong, I. et al. Is referral to home health rehabilitation after inpatient rehabilitation facility associated with 90-Day hospital readmission for adult patients with stroke?? Am J. Phys. Med. Rehabil Sep. 99 (9), 837–841. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001435 (2020).

Howrey, B. T., Kuo, Y. F. & Goodwin, J. S. Association of care by hospitalists on discharge destination and 30-day outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Med Care Aug. 49 (8), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182166cb6 (2011).

Kaufman, B. G. et al. The medicare shared savings program and outcomes for ischemic stroke patients: a retrospective cohort study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34 (12), 2740–2748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05283-1 (Dec 2019).

Liao, C. H., Lu, N., Tang, C. H., Chang, H. C. & Huang, K. C. Assessing the relationship between healthcare market competition and medical care quality under taiwan’s National health insurance programme. Eur J. Public. Health Dec. 1 (6), 1005–1011. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky099 (2018).

Lusk, J. B. et al. Association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and 30-Day mortality and readmission for patients with common neurologic conditions. Neurology Apr. 25 (17), e1776–e1786. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000207094 (2023).

Moody, K. A., Maillie, L. & Dhamoon, M. S. National patterns and outcomes of neurologist care in acute ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist Jan. 13 (1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/19418744221129428 (2023).

Nagayama, H., Tomori, K., Ikeda, K. & Yamauchi, K. Medical costs and readmissions after intensive poststroke rehabilitation: Japanese claims data. J Am. Med. Dir. Assoc Aug. 22 (8), 1762–1766e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.015 (2021).

Svendsen, M. L., Ehlers, L. H., Frydenberg, M., Ingeman, A. & Johnsen, S. P. Quality of care and patient outcome in stroke units: is medical specialty of importance? Med Care Aug. 49 (8), 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318213c024 (2011).

Tyagi, S. et al. Dyadic approach to post-stroke hospitalizations: role of caregiver and patient characteristics. BMC Neurol Nov. 4 (1), 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1510-4 (2019).

Yoon, J. et al. Outcomes of veterans treated in veterans affairs hospitals vs Non-Veterans affairs hospitals. JAMA Netw. Open Dec. 1 (12), e2345898. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.45898 (2023).

Kennedy, B. S. Does race predict stroke readmission? An analysis using the truncated negative binomial model. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 97 (5), 699–713 (2005).

Kao, A., Lanford, J., Wong, L. K. & Ranta, A. Do clinical nurse specialist led stroke follow-up clinics reduce post-stroke hospital readmissions and recurrent vascular events? Intern Med. J Oct. 50 (10), 1202–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14707 (2020).

Albert, G. P. et al. Hospital discharge and readmissions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic for California acute stroke inpatients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Aug. 32 (8), 107233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107233 (2023).

Allen, A. et al. Impact of neurological Follow-Up on early hospital readmission rates for acute ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist Jul. 7 (3), 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874416684456 (2017).

Andrews, A. W., Li, D. & Freburger, J. K. Association of rehabilitation intensity for stroke and risk of hospital readmission. Phys Ther Dec. 95 (12), 1660–1667. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140610 (2015).

Ang, S. H. et al. Risk of 28-day readmissions among stroke patients in Malaysia (2008–2015): trends, causes and its associated factors. PLoS One. 16 (1), e0245448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245448 (2021).

Bergholt, M. D. et al. Accreditation and clinical outcomes: shorter length of stay after first-time hospital accreditation in the Faroe Islands. Int J. Qual. Health Care Apr. 15 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac015 (2022).

Bhattacharya, P., Khanal, D., Madhavan, R. & Chaturvedi, S. Why do ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack patients get readmitted? J Neurol. Sci Aug. 15 (1–2), 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.022 (2011).

Boehme, A. K. et al. Infections increase the risk of 30-Day readmissions among stroke survivors. Stroke Dec. 49 (12), 2999–3005. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.118.022837 (2018).

Bondi, S., Yang, D., Croll, L. & Torres, J. Patient characteristics associated with readmission to 3 neurology services at an urban academic center. Neurohospitalist Jan. 11 (1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874420953320 (2021).

Brom, H., Brooks Carthon, J. M., Sloane, D., McHugh, M. & Aiken, L. Better nurse work environments associated with fewer readmissions and shorter length of stay among adults with ischemic stroke: A cross-sectional analysis of united States hospitals. Res Nurs. Health Jun. 44 (3), 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.22121 (2021).

Burke, J. F., Skolarus, L. E., Adelman, E. E., Reeves, M. J. & Brown, D. L. Influence of hospital-level practices on readmission after ischemic stroke. Neurology Jun. 17 (24), 2196–2204. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000514 (2014).

Cai, M. et al. Ambient particulate matter pollution of different sizes associated with recurrent stroke hospitalization in china: A cohort study of 1.07 million stroke patients. Sci Total Environ Jan. 15 (Pt 2), 159104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159104 (2023).

Carthon, J. M. B. et al. Racial disparities in stroke readmissions reduced in hospitals with better nurse staffing. Nurs Res Jan-Feb. 01 (1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000552 (2022).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Predicting 30-Day readmission for stroke using machine learning algorithms: A prospective cohort study. Front. Neurol. 13, 875491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.875491 (2022).

Chiou, L. J. & Lang, H. C. Potentially preventable hospital readmissions after patients’ first stroke in Taiwan. Sci Rep Mar. 8 (1), 3743. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07791-3 (2022).

Condon, C., Lycan, S., Duncan, P. & Bushnell, C. Reducing readmissions after stroke with a structured nurse practitioner/registered nurse transitional stroke program. Stroke Jun. 47 (6), 1599–1604. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.115.012524 (2016).

Crispo, J. A. G., Thibault, D. P., Fortin, Y., Krewski, D. & Willis, A. W. Association between medication-related adverse events and non-elective readmission in acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol Nov. 19 (1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1195-0 (2018).

Darabi, N., Hosseinichimeh, N., Noto, A., Zand, R. & Abedi, V. Machine Learning-Enabled 30-Day readmission model for stroke patients. Front. Neurol. 12, 638267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.638267 (2021).

Daras, L. C., Deutsch, A., Ingber, M. J., Hefele, J. G. & Perloff, J. Inpatient rehabilitation facilities’ hospital readmission rates for medicare beneficiaries treated following a stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil Jan. 28 (1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2020.1771927 (2021).

de Belvis, A. G. et al. Ischemic stroke: clinical pathway impact. Int J. Health Care Qual. Assur Apr. 15 (3), 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhcqa-05-2018-0111 (2019).

Dennis, J. A. et al. Sex differences in stroke hospitalization incidence, 30-Day mortality, and readmission in a regional medical center in the Southwestern united States. South Med. J Mar. 114 (3), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.14423/smj.0000000000001221 (2021).

Fehnel, C. R. et al. Post-Acute Care Data for Predicting Readmission After Ischemic Stroke: A Nationwide Cohort Analysis Using the Minimum Data Set. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 22 ;4(9):e002145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.115.002145 (2015).

Fonarow, G. C. et al. Hospital-level variation in mortality and rehospitalization for medicare beneficiaries with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke Jan. 42 (1), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.601831 (2011).

Galper, A., Magnezi, R., Ekka Zohar, A., Oberman, B. & Zimlichman, E. COVID-19 lockdown impact on quality of treatment and outcomes of STEMI and stroke patients in a large tertiary medical center: an observational study. Int J. Qual. Health Care Oct. 11 (4). https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac074 (2022).

Gardener, H. et al. Race-Ethnic disparities in 30-Day readmission after stroke among medicare beneficiaries in the Florida stroke registry. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Dec. 28 (12), 104399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104399 (2019).

Gold, C. A., Scott, B. J., Weng, Y., Bernier, E. & Kvam, K. A. Outcomes of a neurohospitalist program at an academic medical center. Neurohospitalist Jul. 12 (3), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/19418744221083182 (2022).

Hamadi, H. Y., Martinez, D., Palenzuela, J. & Spaulding, A. C. Magnet hospitals and 30-Day readmission and mortality rates for medicare beneficiaries. Med Care Jan. 59 (1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001427 (2021).

Han, K. T. et al. Positive correlation between care given by specialists and registered nurses and improved outcomes for stroke patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 353 (1–2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.034 (2015).

Hirayama, A., Goto, T., Faridi, M. K., Camargo, C. A. Jr. & Hasegawa, K. Age-related differences in the rate and diagnosis of 30-day readmission after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke. Int J. Stroke Oct. 13 (7), 717–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493018772790 (2018).

Hussein, H. M., Chrenka, E. A. & Herrmann, A. A. Rate and predictors of acute care encounters in the first month after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Jun. 31 (6), 106466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106466 (2022).

Hwang, P. J. Impact of NP follow-up calls on reducing 30-day readmissions in patients with stroke. Nurse Pract May. 1 (5), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NPR.0000827056.81217.5b (2022).

Jala, S. et al. In safe Hands - A costly integrated care program with limited benefits in stroke unit care. J Clin. Neurosci Jan. 59, 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.10.135 (2019).

Jun-O’Connell, A. H. et al. Association between the LACE + index and unplanned 30-day hospital readmissions in hospitalized patients with stroke. Front. Neurol. 13, 963733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.963733 (2022).

Kable, A., Pond, D., Baker, A., Turner, A. & Levi, C. Evaluation of discharge Documentation after hospitalization for stroke patients discharged home in australia: A cross-sectional, pilot study. Nurs Health Sci Mar. 20 (1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12368 (2018).

Kanazawa, N. et al. Implementation of rehabilitation and patient outcomes during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Prog Rehabil Med. 7, 20220031. https://doi.org/10.2490/prm.20220031 (2022).

Kapral, M. K. et al. Gender differences in stroke care and outcomes in Ontario. Womens Health Issues Mar-Apr. 21 (2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.002 (2011).

Keyhani, S. et al. Effect of clinical and social risk factors on hospital profiling for stroke readmission: a cohort study. Ann Intern. Med Dec. 2 (11), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-0361 (2014).

Khaksari, B. J., Kulick, E. R., Elkind, M. S. V. & Boehme, A. K. Weekend effect on 30-Day readmissions among stroke survivors: an analysis of the National readmission database. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra. 9 (2), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500611 (2019).

Kilkenny, M. F., Longworth, M., Pollack, M., Levi, C. & Cadilhac, D. A. Factors associated with 28-day hospital readmission after stroke in Australia. Stroke Aug. 44 (8), 2260–2268. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.111.000531 (2013).

Kilkenny, M. F. et al. Readmissions after stroke: linked data from the Australian stroke clinical registry and hospital databases. Med J. Aust Jul. 20 (2), 102–106. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja15.00021 (2015).

Kim, Y., Glance, L. G., Holloway, R. G. & Li, Y. Medicare shared savings program and readmission rate among patients with ischemic stroke. Neurology Aug. 25 (8), e1071–e1079. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000010080 (2020).

Kim, Y. et al. Institutional postacute care use May help reduce readmissions for ischemic stroke patients. Med Care Aug. 1 (8), 736–742. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001568 (2021).

Kim, Y. et al. The Effect of Medicare Shared Savings Program on Readmissions and Variations by Race/Ethnicity and Payer Status (December 9, 2020). Med Care. Apr 1. ;59(4):304–311. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001513

Kumar, A. et al. Use of hospital-Based rehabilitation services and hospital readmission following ischemic stroke in the united States. Arch Phys. Med. Rehabil Jul. 100 (7), 1218–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.12.028 (2019).

Kumar, A. et al. Medicare Claim-Based National institutes of health stroke scale to predict 30-Day mortality and hospital readmission. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 37 (11), 2719–2726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07162-0 (Aug 2022).

Langagergaard, V. et al. Socioeconomic differences in quality of care and clinical outcome after stroke: a nationwide population-based study. Stroke Oct. 42 (10), 2896–2902. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.611871 (2011).

Lee, S. A. et al. Patient and hospital factors associated with 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with stroke. J Investig Med Jan. 67 (1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2018-000748 (2019).

Lee, J. D. et al. Prediction model of early return to hospital after discharge following acute ischemic stroke. Curr. Neurovasc Res. 16 (4), 348–357. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202616666190911125951 (2019).

Leifheit, E. C., Wang, Y., Goldstein, L. B. & Lichtman, J. H. Outcomes after ischemic stroke for dual-eligible Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries in the united States. PLoS One. 18 (10), e0292546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292546 (2023).

Leonhardt-Caprio, A. M., Sellers, C. R., Palermo, E., Caprio, T. V. & Holloway, R. G. A Multi-Component transition of care improvement project to reduce hospital readmissions following ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist Apr. 12 (2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/19418744211036632 (2022).

Leppert, M. H. et al. Relationship between early follow-up and readmission within 30 and 90 days after ischemic stroke. Neurology Mar. 24 (12), e1249–e1258. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000009135 (2020).

Li, H. W., Yang, M. C. & Chung, K. P. Predictors for readmission of acute ischemic stroke in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 110 (10), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2011.08.004 (Oct 2011).

Li, C. Y. et al. Functional status across Post-Acute settings is associated with 30-Day and 90-Day hospital readmissions. J Am. Med. Dir. Assoc Dec. 22 (12), 2447–2453e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.07.039 (2021).

Lichtman, J. H. et al. Outcomes after ischemic stroke for hospitals with and without joint Commission-certified primary stroke centers. Neurology Jun. 7 (23), 1976–1982. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e54f3 (2011).

Lichtman, J. H., Leifheit-Limson, E. C., Jones, S. B., Wang, Y. & Goldstein, L. B. 30-Day risk-standardized mortality and readmission rates after ischemic stroke in critical access hospitals. Stroke Oct. 43 (10), 2741–2747. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.112.665646 (2012).

Lichtman, J. H., Leifheit-Limson, E. C., Jones, S. B., Wang, Y. & Goldstein, L. B. Preventable readmissions within 30 days of ischemic stroke among medicare beneficiaries. Stroke Dec. 44 (12), 3429–3435. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.113.003165 (2013).

Lichtman, J. H., Leifheit, E. C., Wang, Y. & Goldstein, L. B. Hospital quality metrics: america’s best hospitals and outcomes after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Feb. 28 (2), 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.10.022 (2019).

Lien, C.-H. et al. Readmission prediction for patients with ischemic stroke after discharge. Int. Symp. Comput., Consum. Control(IS3C) 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1109/IS3C50286.2020.00019 (2020).

Lin, Z. et al. Discharge against medical advice in acute ischemic stroke: the risk of 30-Day unplanned readmission. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36 (5), 1206–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06366-0 (May 2021).

Liu, C. et al. Predictors, timing, causes and cost of 30-day readmission after acute ischemic stroke: insights from a Chinese cohort 2015–2018. Neurol Res Nov. 44 (11), 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2022.2105489 (2022).

Loebel, E. M., Rojas, M., Wheelwright, D., Mensching, C. & Stein, L. K. High risk features contributing to 30-Day readmission after acute ischemic stroke: A single center retrospective Case-Control study. Neurohospitalist Jan. 12 (1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/19418744211027746 (2022).

Lv, J. et al. An interpretable machine learning approach for predicting 30-day readmission after stroke. Int J. Med. Inform Jun. 174, 105050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105050 (2023).

Man, S., Bruckman, D., Tang, A. S., Uchino, K. & Schold, J. D. The association of socioeconomic status and discharge destination with 30-Day readmission after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Dec. 30 (12), 106146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.106146 (2021).

Martin, S., Street, A., Han, L. & Hutton, J. Have hospital readmissions increased in the face of reductions in length of stay? Evidence from England. Health Policy Jan. 120 (1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.11.003 (2016).

Martin, G. P. et al. Readmission and processes of care across weekend and weekday hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure or stroke: an observational study of the National readmission database. BMJ Open Aug. 22 (8), e029667. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029667 (2019).

McClain JVt, Chance, E. A. The advanced practice nurse will see you now: impact of a transitional care clinic on hospital readmissions in stroke survivors. J Nurs. Care Qual Apr/Jun. 35 (2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncq.0000000000000414 (2020).

McGee, B. T. et al. Medicaid expansion and racial/ethnic differences in readmission after acute ischemic stroke. Inquiry Jan-Dec. 58, 469580211062438. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211062438 (2021).

Mitchell, E., Reynolds, S. S., Mower-Wade, D., Raser-Schramm, J. & Granger, B. B. Implementation of an advanced practice registered Nurse-Led clinic to improve Follow-up care for Post-Ischemic stroke patients. J Neurosci. Nurs Oct. 1 (5), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnn.0000000000000670 (2022).

Mittal, M. K., Rabinstein, A. A., Mandrekar, J., Brown, R. D. Jr. & Flemming, K. D. A population-based study for 30-d hospital readmissions after acute ischemic stroke. Int J. Neurosci Apr. 127 (4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2016.1207642 (2017).

Nakagawa, K., Ahn, H. J., Taira, D. A., Miyamura, J. & Sentell, T. L. Ethnic comparison of 30-Day potentially preventable readmissions after stroke in Hawaii. Stroke Oct. 47 (10), 2611–2617. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.116.013669 (2016).

Nathans, A. M. et al. Impact of a Pharmacist-Driven poststroke transitions of care clinic on 30 and 90-Day hospital readmission rates. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Apr. 29 (4), 104648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104648 (2020).

Nkemdirim Okere, A., Sanogo, V., Balkrishnan, R. & Diaby, V. A quantitative analysis of the effect of continuity of care on 30-day readmission and in-hospital mortality among patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Sep. 29 (9), 105053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105053 (2020).

Nouh, A. M., McCormick, L., Modak, J., Fortunato, G. & Staff, I. High mortality among 30-Day readmission after stroke: predictors and etiologies of readmission. Front. Neurol. 8, 632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00632 (2017).

Okere, A. N., Renier, C. M. & Frye, A. Predictors of hospital length of stay and readmissions in ischemic stroke patients and the impact of inpatient medication management. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Aug. 25 (8), 1939–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.04.011 (2016).

Parikh, S., George, P., Wilson, K., Rybin, D. & Hohler, A. D. Alcohol use and hospital readmissions following stroke: A safety net hospital experience. J Neurol. Sci Feb. 15, 385:83–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.12.016 (2018).

Patel, M. S. et al. Association of the 2011 ACGME resident duty hour reforms with mortality and readmissions among hospitalized medicare patients. Jama Dec. 10 (22), 2364–2373. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.15273 (2014).

Poston, K. M., Dumas, B. P. & Edlund, B. J. Outcomes of a quality improvement project implementing stroke discharge advocacy to reduce 30-day readmission rates. J Nurs. Care Qual Jul-Sep. 29 (3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000040 (2014).

Pruski, A. et al. Feasibility of an enhanced therapy model of care for hospitalized stroke patients. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Feb 1 (2S Suppl 1), S19–s23. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000002140 (2023).

Qiu, X. et al. Predictors, causes and outcome of 30-day readmission among acute ischemic stroke. Neurol Res Jan. 43 (1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2020.1815954 (2021).

Raja, A., Trivedi, P. D. & Dhamoon, M. S. Discharge against medical advice among neurological patients: characteristics and outcomes. Health Serv. Res Oct. 55 (5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13306 (2020).

Roberts, P., Aronow, H., Ouellette, D., Sandhu, M. & DiVita, M. Bounce-Back: predicting acute readmission from inpatient rehabilitation for patients with stroke. Am J. Phys. Med. Rehabil Jul. 1 (7), 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001875 (2022).

Shah, S. V. et al. Impact of poststroke medical complications on 30-Day readmission rate. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Sep. 24 (9), 1969–1977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.04.037 (2015).

Slocum, C. et al. Functional status predicts acute care readmissions from inpatient rehabilitation in the stroke population. PLoS One. 10 (11), e0142180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142180 (2015).

Sobhani, F. et al. Remote longitudinal inpatient acute stroke care via telestroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Jun. 30 (6), 105749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105749 (2021).

Strowd, R. E. et al. Predictors of 30-day hospital readmission following ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Am J. Med. Qual Sep-Oct. 30 (5), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860614535838 (2015).

Suri, M. F. & Qureshi, A. I. Readmission within 1 month of discharge among patients with acute ischemic stroke: results of the university healthsystem consortium stroke benchmarking study. J Vasc Interv Neurol Dec. 6 (2), 47–51 (2013).

Terman, S. W., Reeves, M. J., Skolarus, L. E. & Burke, J. F. Association between early outpatient visits and readmissions after ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes Apr. 11 (4), e004024. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.117.004024 (2018).

Thompson, M. P. et al. Regional variation in 30-Day ischemic stroke outcomes for medicare beneficiaries treated in get with the Guidelines-Stroke hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes Aug. 10 (8). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003604 (2017).

Tran, P. M., Warren, J. L., Leifheit, E. C., Goldstein, L. B. & Lichtman, J. H. Associations between Long-Term air pollutant exposure and 30-Day All-Cause hospital readmissions in US patients with stroke. Stroke Apr. 54 (4), e126–e129. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.122.042265 (2023).

Vahidy, F. S. et al. Nationwide estimates of 30-Day readmission in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke May. 48 (5), 1386–1388. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.116.016085 (2017).

Wen, T. et al. Risk factors associated with 31-day unplanned readmission in 50,912 discharged patients after stroke in China. BMC Neurol Dec. 26 (1), 218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1209-y (2018).

Wong, F. K. & Yeung, S. M. Effects of a 4-week transitional care programme for discharged stroke survivors in Hong kong: a randomised controlled trial. Health Soc. Care Community Nov. 23 (6), 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12177 (2015).

Yang, L., Liu, C., Huang, C. & Mukamel, D. B. Patients’ perceptions of interactions with hospital staff are associated with hospital readmissions: a National survey of 4535 hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res Jan. 29 (1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2848-9 (2018).

Yousufuddin, M. et al. Impact of multiple chronic conditions in patients hospitalized with stroke and transient ischemic attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Jun. 26 (6), 1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.01.015 (2017).

Bjerkreim, A. T., Thomassen, L., Brøgger, J., Waje-Andreassen, U. & Næss, H. Causes and predictors for hospital readmission after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Sep. 24 (9), 2095–2101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.05.019 (2015).

Claesson, L., Gosman-Hedström, G., Lundgren-Lindquist, B., Fagerberg, B. & Blomstrand, C. Characteristics of elderly people readmitted to the hospital during the first year after stroke. The Göteborg 70 + stroke study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 14 (3–4), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000065684 (2002).

Claesson, L., Gosman-Hedström, G., Fagerberg, B. & Blomstrand, C. Hospital re-admissions in relation to acute stroke unit care versus conventional care in elderly patients the first year after stroke: the Göteborg 70 + Stroke study. Age Ageing Jan. 32 (1), 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/32.1.109 (2003).

Gordon, C., Davidson, H., Dharmasiri, M. & Davies, T. Factors associated with emergency readmissions after acute stroke: A retrospective audit of two hospitals. J Eval Clin. Pract Feb. 29 (1), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13753 (2023).

Gzesh, D., Murphy, D. A., Peiritsch, H. & MacCracken, T. Benefit of a stroke management program. Popul Health Manag Dec. 23 (6), 482–486. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2019.0123 (2020).

Kilkenny, M. F. et al. Factors associated with 90-Day readmission after stroke or transient ischemic attack: linked data from the Australian stroke clinical registry. Stroke Feb. 51 (2), 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.119.026133 (2020).

Lynch, E. A. et al. Out of sight, out of mind: long-term outcomes for people discharged home, to inpatient rehabilitation and to residential aged care after stroke. Disabil Rehabil Jun. 44 (12), 2608–2614. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1852616 (2022).

Ottenbacher, K. J. et al. Hospital readmission in persons with stroke following postacute inpatient rehabilitation. J Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci Aug. 67 (8), 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr247 (2012).

Peng, L. N. et al. Functional outcomes, subsequent healthcare utilization, and mortality of stroke postacute care patients in taiwan: A nationwide propensity Score-matched study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. Nov 1 (11), 990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.020 (2017).

Xie, W., Zhao, Z-H., Yang, Q-M. & Wei, F-H. The efficacy of the seamless transfer of care model to apply for the patients with cerebral apoplexy in China. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. /03/01/ 2015;2(1):52–57. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2015.01.012

Xu, Y. et al. Extreme gradient boosting model has a better performance in predicting the risk of 90-Day readmissions in patients with ischaemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis Dec. 28 (12), 104441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104441 (2019).

Zhao, L. et al. Readmission rate and related risk factors of ischemic stroke patients after 3 months of discharge in Southwest China. Neurol. Asia. 06/01, 25:119–125 (2020).

Aydin, T., Kesiktas, N. & Çorum, M. Analysis of stroke patients requiring Re-hospitalisation for rehabilitation. Med. Bull. Haseki. 12/02, 58:422–427. https://doi.org/10.4274/haseki.galenos.2020.6591 (2020).

Bjerkreim, A. T. et al. One-year versus five-year hospital readmission after ischemic stroke and TIA. BMC Neurol Jan. 29 (1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1242-5 (2019).

Bohannon, R. W. & Lee, N. Association of physical functioning with same-hospital readmission after stroke. Am J. Phys. Med. Rehabil Jun. 83 (6), 434–438. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200406000-00005 (2004).

Cuccurullo, S. J. et al. Impact of modified cardiac rehabilitation within a stroke recovery program on All-Cause hospital readmissions. Am J. Phys. Med. Rehabil Jan. 1 (1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001738 (2022).

Heller, R. F. et al. Death and readmission in the year after hospital admission with cardiovascular disease: the Hunter area heart and stroke register. Med J. Aust Mar. 20 (6), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb123940.x (2000).

Hsieh, C. Y., Lin, H. J., Hu, Y. H. & Sung, S. F. Stroke severity May predict causes of readmission within one year in patients with first ischemic stroke event. J Neurol. Sci Jan. 15, 372:21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.026 (2017).

Jia, H. et al. Multiple system utilization and mortality for veterans with stroke. Stroke Feb. 38 (2), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000254457.38901.fb (2007).

Lainay, C. et al. Hospitalization within the first year after stroke: the Dijon stroke registry. Stroke Jan. 46 (1), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.114.007429 (2015).

Leitão, A. et al. Predictors of hospital readmission 1 year after ischemic stroke. Intern Emerg. Med Feb. 12 (1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1519-2 (2017).

Lin, H. J., Chang, W. L. & Tseng, M. C. Readmission after stroke in a hospital-based registry: risk, etiologies, and risk factors. Neurology. Feb 1. ;76(5):438 – 43. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820a0cd8

Reeves, M. J., Prager, M., Fang, J., Stamplecoski, M. & Kapral, M. K. Impact of living alone on the care and outcomes of patients with acute stroke. Stroke Oct. 45 (10), 3083–3085. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.114.006520 (2014).

Sennfält, S., Petersson, J., Ullberg, T. & Norrving, B. Patterns in hospital readmissions after ischaemic stroke - An observational study from the Swedish stroke register (Riksstroke). Eur Stroke J Sep. 5 (3), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396987320925205 (2020).

Tay, M. R. J. Hospital readmission in stroke survivors one year versus three years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation: prevalence and associations in an Asian cohort. J Rehabil Med Jun. 17 (6), jrm00208. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2849 (2021).

Torp, C. R. et al. Model of hospital-supported discharge after stroke. Stroke Jun. 37 (6), 1514–1520. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000221793.81260.ed (2006).

Tseng, M. C. & Lin, H. J. Readmission after hospitalization for stroke in taiwan: results from a National sample. J Neurol. Sci Sep. 15 (1–2), 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.009 (2009).

Zhou, L. W., Lansberg, M. G. & de Havenon, A. Rates and reasons for hospital readmission after acute ischemic stroke in a US population-based cohort. PLoS One. 18 (8), e0289640. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289640 (2023).

Rogstad, T. L., Gupta, S., Connolly, J., Shrank, W. H. & Roberts, E. T. Social risk adjustment in the hospital readmissions reduction program: A systematic review and implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood) Sep. 41 (9), 1307–1315. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00614 (2022).

Aswani, M. S. & Roberts, E. T. Social risk adjustment in the hospital readmission reduction program: pitfalls of peer grouping, measurement challenges, and potential solutions. Health Serv. Res. 58 (1), 51–59 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research received no financial support, and the authors declare no conflicts of interest. The review was not registered. All supplementary material is provided in the supplementary information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The team worked collaboratively throughout the research and writing process. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mauti, E., Hosseinichimeh, N., Abedi, V. et al. Factors associated with post-stroke readmission: a systematic review and meta analysis. Sci Rep 15, 34772 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18568-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18568-9