Abstract

Emerging evidence links epigenetic modifications, oxidative stress, and trace element imbalances to the pathogenesis of Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). This study investigates the interplay between these mechanisms in a rat model of PCOS and evaluates the ameliorative effects of quercetin, a flavonoid with phytoestrogenic properties. PCOS was induced in female rats using dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, 6 mg/100 g body weight). After confirmation of PCOS induction, Quercetin (15 mg/kg/day) was administered via oral gavage for 30 days post-induction. Expression of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) genes was assessed in ovarian tissue, while serum levels of trace elements (Zn, Cu, Mg, Fe) and oxidative stress markers in the liver were analyzed. PCOS induction significantly reduced hepatic Gpx, CAT, SOD, and GR activities, decreased GSH levels, and lowered serum concentrations of Zn, Cu, and Mg. Conversely, DNMT1 and DNMT3a expression, serum Fe levels, and hepatic MDA were elevated. Quercetin reversed these alterations, restoring antioxidant enzyme activities, GSH levels, and Zn concentrations while reducing MDA levels and DNMT3a expression. DNMT3b expression remained unchanged across groups. This study highlights the coordinated role of epigenetic dysregulation, oxidative stress, and trace element imbalances in the pathogenesis of PCOS. Quercetin appears to offer potential as an adjunctive treatment option for PCOS treatment when paired with trace element supplementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex hormonal condition impacting around 5–10% of women during their childbearing years, marked by elevated androgen levels, irregular ovulation, and the presence of cysts on the ovaries1,2. Beyond its reproductive manifestations, PCOS is associated with metabolic disturbances, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes2.

The pathogenesis of PCOS remains poorly understood, but emerging evidence suggests a complex interplay between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors3. Disrupted communication between oocytes and somatic cells in the ovarian cortex leads to follicular arrest and diminished oocyte developmental competence, further exacerbating infertility in affected individuals4,5. Recent studies have highlighted the role of epigenetic modifications, particularly DNA methylation, in the regulation of gene expression during oocyte maturation and folliculogenesis6,7.

DNA methylation, mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), is critical for maintaining genomic stability and silencing transposable elements, thereby protecting oocytes from intragenomic stress6,8. However, oxidative stress, a hallmark of PCOS, can disrupt these epigenetic processes by altering chromatin architecture and DNA methylation patterns9. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) not only induce DNA hypermethylation but also interfere with histone modifications, leading to impaired oocyte maturation and endometrial dysfunction10,11. Furthermore, oxidative stress exacerbates hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance, creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates PCOS pathology12,13,14.

Trace elements, such as zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe), play pivotal roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and enzymatic function, particularly in antioxidant defense systems15. Deficiencies or imbalances in these elements have been linked to metabolic syndrome and PCOS, likely due to their roles as cofactors for antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) reactions16. For instance, zinc deficiency has been associated with insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism, both of which are common in PCOS15,17. Conversely, Fe overload can exacerbate oxidative stress, further contributing to the disorder’s progression11.

Medicinal plants have shown promising potential in alleviating reproductive disorders such as PCOS, endometriosis, and infertility18,19. Therefore, natural remedies offer a complementary approach to conventional treatments, with fewer side effects, making them a valuable option for managing reproductive issues.

Quercetin is a bioactive flavonoid with antioxidant properties, widely used to treat metabolic and inflammatory disorders20,21. Numerous pharmacological studies indicate that quercetin supplements significantly regulate redox status, reduce inflammation, and enhance antioxidant defenses, potentially offering protective effects against oxidative stress-related diseases22. Quercetin can address multiple pathological processes associated with PCO through various targets and pathways, making it a promising candidate for a new treatment for this condition23,24. Despite numerous studies on quercetin and PCOS, the potential relationship between liver antioxidant enzyme activity, trace element status, and ovarian DNMT expression in this condition has not yet been thoroughly investigated.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the interplay between epigenetic modifications, oxidative stress, and trace element imbalances in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome using a dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-induced rat model. Specifically, we seek to evaluate the effects of PCOS on DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) gene expression (DNMT1, DNMT3a, DNMT3b), oxidative stress markers (glutathione peroxidase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, glutathione, and malondialdehyde), and trace element levels (zinc, copper, magnesium, and Fe) in ovarian tissue, serum, and liver. Furthermore, this study explores the therapeutic potential of quercetin, a natural flavonoid with antioxidant and phytoestrogenic properties, in reversing PCOS-associated alterations. By elucidating the coordinated roles of these mechanisms, this research aims to provide novel insights into PCOS pathogenesis and demonstrate the potential of quercetin as a complementary treatment, particularly when combined with trace element supplementation, to improve reproductive and metabolic outcomes in PCOS.

Results

Confirmation of the rat model of PCOS

Vaginal smear

A complete estrous cycle, encompassing the phases of proestrus, estrus, metestrus, and diestrus, typically spans four to five days. In the control group, all rats displayed regular cyclic changes. Conversely, in the PCOS group, the metestrus and diestrus phases were notably extended, lasting between 10 and 13 days in all rats. Rats in the PCOS group showed a significantly higher percentage of diestrus days (63.2%) compared with the control group (33.2%), with a statistical significance of p < 0.001.

Testosterone measurement

PCOS induction by DHEA resulted in a significant increase in testosterone serum levels (P < 0.001) (3.1 ± 0.54 ng/ml in the PCOS group vs. 0.47 ± 0.09 ng/ml in the control group).

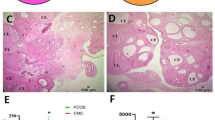

Ovarian histopathology

Histologically, the ovaries of control rats exhibited follicles at various stages of development. In contrast, the ovaries of the PCOS group primarily contained small follicles in the early developmental phase with numerous large cystic follicles (Fig. 1). The number of primordial, primary, Secondary, Graffian, and atretic follicles, as well as corpus Luteum and ovarian cysts, are presented in Table 1.

Zn, mg, cu, and Fe concentrations in the serum

As shown in Fig. 2A-C, the levels of zinc (Zn), magnesium (Mg), and copper (Cu) in the serum were significantly lower in the PCOS group compared with the control group, with reductions of 27% (P < 0.01), 25% (P < 0.05), and 30% (P < 0.05), respectively. Further investigation demonstrated that administering quercetin to the PCOS + Q group led to a 26% increase in Zn levels relative to the PCOS group, a statistically significant change (P < 0.01). However, quercetin treatment did not produce any statistically meaningful changes in the levels of Mg or Cu in the PCOS + Q group when compared with the PCOS group (P > 0.05). In contrast, Fe (Fe) concentrations in the serum were notably higher in the PCOS group than in the control group, showing a 42% increase (P < 0.05). No significant difference in Fe levels was observed between the PCOS + Q and PCOS groups (P > 0.05), as illustrated in Fig. 2D.

Changes in the serum (A) Zn, (B) Mg, (C) Cu, and (D) Fe concentration expressed as. Means ± S.D. Significant differences indicated as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS + Q: polycystic ovary syndrome + quercetin. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to analyze group differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of (P < 0.05), (n = 10/group).

Antioxidant effect of quercetin

Effect of quercetin on the antioxidant enzyme activity in liver tissue

Figure 3A-D represents a statistical comparison between the levels of antioxidant enzyme activity in all study groups. The induction of PCOS by DHEA led to a sharp decrease in the GR activity by 40%, CAT by 48%, Gpx by 47%, and SOD activity by 43% in the PCOS group compared with the control rats (P < 0.0001 for all). 30 days of treatment with quercetin markedly increased the activity of GR by 75%, CAT by 67%, Gpx by 76%, and SOD by 98% in the PCOS + Q group compared with the PCOS group (P < 0.0001 for all) (Fig. 3A-D).

Changes in the liver (A) GR, (B) CAT, (C) Gpx, and (D) SOD activity expressed as mean. ± S.D. Significant differences indicated as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS + Q: polycystic ovary syndrome + quercetin. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to analyze group differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of (P < 0.05), (n = 10/group).

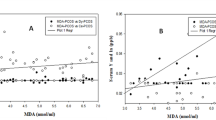

Effect of quercetin on the hepatic GSH and MDA levels

In the study, the levels of glutathione (GSH) in rats with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) showed a significant reduction when compared with the control group, with a decrease of 46% (P < 0.001). However, when the PCOS-induced rats were treated with quercetin (PCOS + Q group), the GSH content increased dramatically by 97% compared with the untreated PCOS group (P < 0.0001), as illustrated in Fig. 4A. Additionally, the liver malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the PCOS group were notably higher, showing a 75% increase relative to the control group (P < 0.0001). Treatment with 15 mg/kg of quercetin led to a significant reduction in MDA levels by 35% in both the PCOS + Q and quercetin-treated groups compared with the untreated PCOS and control groups (P < 0.0001), as depicted in Fig. 4B. These findings suggest that quercetin has a protective effect against oxidative stress in PCOS by enhancing GSH levels and reducing MDA levels in the liver.

Changes in the liver (A) GSH and (B) MDA levels expressed as mean ± S.D. Significant. differences indicated as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS + Q – polycystic ovary syndrome + quercetin. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to analyze group differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of (P < 0.05), (n = 10/group).

Effect of quercetin on the methyltransferase relative gene expression in the ovaries

Figure 5A Reveals the sharp increase in the relative expression of the DNMT1 gene in the ovaries of the PCOS group (P < 0.001). This elevation was 43% higher compared with the control group. However, treatment with quercetin has no significant effect on the expression level of this gene (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5A).

Changes in the relative expression of ovarian (A) DNMT1, (B) DNMT3a, and (C). DNMT3 expressed as mean ± S.D. Significant differences indicated as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001; ns: Not Significant. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS + Q: polycystic ovary syndrome + quercetin. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to analyze group differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of (P < 0.05). The PCOS and PCOS + Q groups were compared with the normal group, and the PCOS + Q group with the PCOS group (n = 10/group).

As provided in Fig. 5B, the expression level of ovarian DNMT3a in the PCOS-induced rats was 50% greater than the control group (P < 0.0001). Treatment with quercetin decreased the expression of DNMT3a by 16% in PCOS + Q rats compared with the PCOS-induced rats (P < 0.05).

Figure 5C illustrates a statistical comparison of DNMT3b gene expression levels in different groups. Surprisingly, the changes in the ovarian DNMT3b gene were negligible among the normal, PCOS, and PCOS + Q groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

In line with our previous study, PCOS was successfully induced in rats using DHEA and confirmed through vaginal smear analysis25. Our results showed decreased levels of GSH and activities of Gpx, SOD, CAT, and GR in the liver tissue of PCOS-induced rats, along with an increased level of MDA. This indicates an imbalance in oxidative stress, as these enzymes are essential for defense against it. Current understanding highlights that PCOS is associated with oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant levels14. Insulin resistance and dyslipidemia can elevate ROS production due to endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid peroxidation, affecting glucose and lipid metabolism. Recent studies indicate that quercetin significantly boosts antioxidant enzyme activity compared to the PCOS group. Consistent with this, Y. Hong et al. found that quercetin enhances the antioxidant system, particularly CAT, SOD, and Gpx, in a rat model.

Quercetin’s antioxidant properties stem from its ability to regulate intracellular pathways and increase GSH levels, which help scavenge free radicals26,27,28. Rashidi et al. (2019) showed that quercetin protected human granulosa cells from oxidative stress by reducing ROS production and apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide. It activated the Nrf2/ARE pathway, increased Nrf2 expression, and enhanced the thioredoxin system, further mitigating oxidative damage29.

Our study showed that Mg, Zn, and Cu decreased in the PCOS-induced rats. Previous studies have reported that Mg and Zn could increase insulin receptor sensitivity and enhance cellular glucose uptake30,31. Consequently, a deficiency in either of them leads to insulin resistance, which is often associated with PCOS32. Additionally, Mg, Zn, and Cu are crucial cofactors for the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD32. A deficiency in Mg, Zn, or Cu can therefore reduce the activity of these antioxidant enzymes and contribute to oxidative stress32. Furthermore, it has been indicated that their deficiency is linked to reduced DNA methylation due to the disruption of DNMT enzymes33,34. Our data analysis revealed no significant changes in serum Mg and Cu levels following quercetin treatment, which may be due to the strict physiological regulation of these minerals, which keeps serum concentrations within a narrow range even in pathological conditions35. It is also possible that the relatively short duration and dosage used in this study were not sufficient to produce detectable changes in systemic Mg and Cu levels. The correlation of PCOS with serum Zn/Cu deficits has been shown36.

In a study by Kanafchian et al., analyzing the relationship between serum selenium, zinc levels, and insulin resistance in patients with PCOS showed that the levels of both elements were significantly lower in the PCOS group compared with the control group. Furthermore, in the insulin-resistant PCOS patients, zinc levels had a negative correlation with HOMA-IR and a positive correlation with the glucose/insulin ratio and insulin levels37.

The current study revealed a high Fe concentration in the liver of rats with PCOS. Fe is known to induce oxidative stress, leading to damage in proteins, DNA, and lipids38. Consequently, the heightened Fe concentration observed in PCOS-induced rats is likely associated with a reduction in the activity of antioxidant enzymes within the PCOS group.

Alterations in serum Fe and ferritin levels have been observed in patients with PCOS and animal models of the condition, highlighting potential disruptions in Fe metabolism. While serum Fe levels often remain unchanged or show minimal variation in PCOS patients, elevated serum ferritin levels are frequently reported, indicating increased Fe storage and potential Fe overload39,40. These findings suggest that Fe overload, particularly in the liver, may contribute to the metabolic and inflammatory complications in PCOS.

Quercetin’s bioavailability and tissue distribution can vary significantly between organs due to differences in absorption, metabolism, and tissue uptake. Bioavailability of quercetin has been reported from about 16 to 53% in serum in different studies41,42.

Although quercetin itself exhibits antioxidant effects, its role in mitigating oxidative stress may be partly mediated through its influence on Zn, which in turn modulates the activity of antioxidant enzymes. Furthermore, elevated Zn levels have been shown to provide protective benefits against oxidative damage induced by Fe43. Thus, the interaction between quercetin, zinc, and Fe may play a critical role in alleviating oxidative stress in PCOS.

Considering its epigenetic correlation with antioxidant capacity and Zn, quercetin can synergistically employ these parameters to improve PCOS + Q rats, and it seems that if it is supplemented with Cu and Mg, its effects on PCOS may be much more remarkable.

Regarding the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3a, our results showed that the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3a in the ovary was significantly increased in the PCOS group, while quercetin treatment notably decreased their expression. Methylation in the ovary has an impact on ovulation and ovarian function, which can lead to issues such as anovulation, irregular menstruation, and infertility in women44. Numerous studies indicate that hypermethylation is associated with hyperandrogenism, overexpression of androgen receptors, and diabetes45,46. Previous research has shown that hypermethylation can result in the downregulation of various antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD47. Increased DNMT expression raises oxidative stress in PCOS models; however, a thorough investigation of methylation patterns is necessary to draw accurate conclusions48,49. Several studies have indicated that quercetin treatment decreases androgen receptor expression50,51. Therefore, quercetin modulates the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3a by decreasing androgen activity.

A key limitation of this study is that while quercetin’s bioavailability and tissue distribution have been previously reported, we did not directly measure its concentrations in the liver or ovary. Instead, our focus was on functional outcomes, such as oxidative stress modulation and DNMT activity. Future studies incorporating bioavailability assessments would help establish a clearer relationship between quercetin’s distribution and its functional impacts in target tissues.

This study shows the interacting cooperation of DNMTs, trace elements, and antioxidant-related factor changes in PCOS pathogenesis, but more molecular and biochemical studies such as assessing AMH and aromatase and global methylation exploration are critical to a better understanding of the PCOS pathology and the impact of Quercetin on various cellular and molecular changes that occur during PCOS induction.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that redox factors, mineral elements, and DNMTs coordinately exert worsening effects on PCOS, which are sufficiently alleviated by quercetin. Therefore, quercetin can be considered a proper treatment for PCOS, especially if its impact on methylation is precisely studied.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and induction of the PCOS rat model

The ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (IR.SUMS.AEC.1403.010). Fifty female Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 200 ± 20 g and aged eight weeks, were purchased from the Animal House of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. The rats were maintained on a standard diet of rat chow (14.7% Lipids, 33.0% protein, and 52.2% carbohydrates, with an energy content of 2.75 Kcal/g) and provided with water. They were housed in a controlled environment with temperatures ranging from 22 to 25 °C and a 12-hour light/dark cycle.

All animal procedures were conducted per the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the ARRIVE guidelines, to ensure the ethical treatment of research animals.

The primary inclusion criterion was the presence of regular estrous cycles, confirmed through vaginal smear evaluations under a light microscope over two consecutive cycles (approximately 8–10 days)52. To induce PCOS, the rats were administered dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (Sigma, 6 mg/100 g body weight dissolved in 0.2 ml sesame oil) via subcutaneous injection for 21 consecutive days24,53,54. Successful PCOS induction was confirmed through vaginal smear analysis, histological evaluation of ovarian tissue, and measurement of serum testosterone levels.

Fifty rats were randomly divided into five groups:

Control Group: Received distilled water (1 mL/day) via oral gavage for 30 days.

Ethanol Group: Administered a 3% ethanol solution (1 mL/day) as the vehicle for quercetin via oral gavage for 30 days.

Quercetin Group: Treated with quercetin (15 mg/kg dissolved in 3% ethanol) via oral gavage for 30 days.

PCOS Group: Received subcutaneous injections of DHEA (6 mg/100 g body weight dissolved in 0.2 ml sesame oil) for 21 days to induce PCOS, followed by no additional treatment for 30 days.

PCOS + Q Group: After 21 days of DHEA injections, this group was administered quercetin (15 mg/kg/day) via oral gavage for 30 days.

Verification of PCOS induction

Vaginal smears

The stages of estrus were identified through microscopic examination of vaginal smears, which were collected daily from the start of the experiment until its conclusion. Smears were prepared each morning and analyzed under a microscope (OLYMPUS, 200x, Japan) using Giemsa staining to determine the predominant cell type and assess the estrus phase55.

Blood sampling

Rats in the diestrus phase were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injections of Ketamine (50 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5 mg/kg) and blood samples were obtained via cardiac puncture. For testosterone measurement, 1 mL of blood was collected into plain tubes without anticoagulant and promptly centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting serum was separated and stored at − 20 °C for further analysis.

Testosterone assay

The serum testosterone levels of control and PCOS-induced rats were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with commercially available kits (Monobind Inc., USA). Optical density measurements were taken at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader (BioTek® Instruments, Highland Park, IL), with a reference wavelength set between 620 and 630 nm. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and both inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were maintained below 5%.

Histological analysis

Following blood collection, the ovaries were removed and preserved in 10% buffered formalin. They were then embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned into 5 μm slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The prepared sections were examined under a light microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Assessment of DNMT gene expression, oxidative stress, and trace elements

Evaluation of Cu, Zn, Fe, and Mg determination in serum

At the end of the treatment period, the rats were euthanized using a CO₂ chamber. The blood was obtained from the heart and the serum was isolated by allowing the blood to coagulate, followed by centrifugation at 1600 × g for 10 min, ensuring the separation of serum from other blood components for subsequent evaluations. The serum was kept at − 20 °C for further analysis of minerals.

The concentration of Cu, Zn, Fe, and Mg in the rat serum was quantified using commercially available colorimetric kits (Bionik) and a Hitachi Chemistry analyzer (Japan).

Assessment of antioxidant enzyme activity in liver

After dissection, the Livers were removed and weighed. The tissues were sheared in chilled 0.9% saline and homogenized for 30 s. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatants were used to assay various antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH), and glutathione peroxidase (Gpx), as well as the level of malondialdehyde (MDA).

Gpx activity evaluation

To assess Gpx (glutathione peroxidase) activity in the liver homogenates, glutathione reductase (GR), reduced glutathione (GSH), and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBuOOH) were added to the reaction mixture. The rate of NADPH oxidation was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 340 nm over a period of 150 s. Gpx activity was expressed as units per gram of protein (U/g protein).

Glutathione reductase (GR) activity

The activity of glutathione reductase (GR) was assessed using the Hafeman method with minor modifications56. Potassium phosphate buffer, EDTA, sodium azide, oxidized glutathione (GSSG), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added to the Liver homogenate supernatant. The reaction was initiated by the addition of NADPH. GR activity was determined by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm for 3 min. Results were expressed as units per gram of protein (U/g protein).

CAT activity evaluation

To determine catalase (CAT) activity, potassium phosphate buffer and deionized water were added to the liver homogenate supernatant, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). The decomposition of H₂O₂ by CAT activity was measured by monitoring the absorbance at 240 nm over a period of 2 min. Data are expressed as units per gram of protein (U/g protein)57.

Superoxide dismutase assay

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the liver homogenate supernatant was assessed using the method developed by Misra and Fridovich, with subsequent modifications by Yarahmadi et al.58. This method is based on the ability of SOD to inhibit the autoxidation of adrenaline to adrenochrome at pH 10.2. Sodium carbonate/sodium bicarbonate (Na₂CO₃/NaHCO₃) buffer (pH 10.2) and EDTA were added to the liver homogenate supernatant. One minute after the addition of adrenaline hydrochloride (HCl) solution (pH 2.0), SOD activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 480 nm. Data are expressed as units per gram of protein (U/g protein).

GSH level evaluation

The GSH levels of the Liver homogenate supernatants were assayed through the GSH reaction with 5,5’-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid. The resulting product from this reaction was measured using spectrophotometry (412 nm). The GSH level obtained from the liver was normalized to the concentration of total protein determined from each sample via the Bradford method. The results are presented as nmol/mg of protein59.

MDA level evaluation

To evaluate the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA), the supernatant obtained from Liver homogenate was treated with 2 mL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and subjected to heating at 100 °C for a duration of 15 min. Following this, the mixture was centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 min, maintaining a temperature of 4 °C. MDA levels were reported as nanomoles of MDA per milligram of protein. The protein concentration in the samples was determined using Bradford’s assay.

Evaluation of DNMT1 and DNMT3 expression in the ovary

After dissection, the ovaries were removed and kept at − 80 °C for analysis of gene expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from ovarian tissue using Tripure reagent (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis). To assess the quality of the RNA, it was electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with Gel Red for visualization. Subsequently, cDNA was generated via reverse transcription employing the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas), adhering strictly to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The quantification of DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b expression levels was performed using real-time PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7500 system. Each PCR reaction was prepared using cDNA derived from 1000 ng of total RNA, SYBR Green PCR master mix, and specific primers targeting β-actin, DNMT1, or DNMT3. The primer sequences utilized in this study are detailed in Table 2. β-actin was used to normalize the expression value as the reference gene. The relative expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3 was calculated via the 2^(−ΔΔCT) method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 software. All data and values are presented as the mean ± S.D. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test checked the normality of data. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to analyze group differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of (P < 0.05).

Data availability

The data used are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Alaee, S. et al. Nutritional intake and lifestyle in infertile women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: A Case-control study. J. Infertility Reproductive Biology. 12 (30-), 15 (2024).

Huo, M., Wang, Y., Yuan, X., Yuan, Y. & Zhang, X. Changing trends in the global burden of polycystic ovarian syndrome-related infertility over the past 30 years: retrospective data analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Womens Health. 25, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03537-7 (2025).

Bruni, V., Capozzi, A. & Lello, S. The role of genetics, epigenetics and lifestyle in polycystic ovary syndrome development: the state of the Art. Reprod. Sci. 29, 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-021-00515-4 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Multi-omics approach to reveal follicular metabolic changes and their effects on oocyte competence in PCOS patients. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1426517 (2024).

Lohrasbi, P. et al. The effects of melatonin and Metformin on histological characteristics of the ovary and uterus in letrozole-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome mice: A Stereological study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 20, 973–988. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijrm.v20i11.12365 (2022).

Vanselow, J. & Fürbass, R. Epigenetic control of folliculogenesis and luteinization. Anim. Reprod. (AR). 7, 134–134 (2018).

Seem, K., Kaur, S., Kumar, S. & Mohapatra, T. Epigenome editing for targeted DNA (de)methylation: a new perspective in modulating gene expression. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 59, 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409238.2024.2320659 (2024).

Gu, L., Wang, Q. & Sun, Q. Y. Histone modifications during mammalian oocyte maturation: dynamics, regulation and functions. Cell. Cycle. 9, 1942–1950. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.9.10.11599 (2010).

García-Giménez, J. L., Garcés, C., Romá-Mateo, C. & Pallardó, F. V. Oxidative stress-mediated alterations in histone post-translational modifications. Free Radical Biology Med. 170, 6–18 (2021).

Caplakova, V. et al. DNA methylation machinery in the endometrium and endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res. 36, 4407–4420. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.10984 (2016).

Dutta, S. et al. Crosstalk between oxidative stress and epigenetics: unveiling new biomarkers in human infertility. Cells 13, 1846 (2024).

Yin, J., Hong, X., Ma, J., Bu, Y. & Liu, R. Serum trace elements in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 572384. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.572384 (2020).

Cheng, T. F., Choudhuri, S. & Muldoon-Jacobs, K. Epigenetic targets of some toxicologically relevant metals: a review of the literature. J. Appl. Toxicol. 32, 643–653 (2012).

Alaee, S., Mirani, M., Derakhshan, Z., Koohpeyma, F. & Bakhtari, A. Thymoquinone improves folliculogenesis, sexual hormones, gene expression of apoptotic markers and antioxidant enzymes in polycystic ovary syndrome rat model. Vet. Med. Sci. 9, 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.958 (2023).

Osredkar, J. & Sustar, N. Copper and zinc, biological role and significance of copper/zinc imbalance. J. Clin. Toxicol. S. 3, 0495 (2011).

Dring, J. C. et al. Essentiality of trace elements in pregnancy, fertility, and gynecologic cancers—a state-of-the-art review. Nutrients 14, 185 (2021).

Salgueiro, M. J. et al. The role of zinc in the growth and development of children. Nutrition 18, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00812-7 (2002).

Alaee, S., Bagheri, M. J., Ataabadi, M. S. & Koohpeyma, F. Capacity of Mentha spicata (spearmint) extracts in alleviating hormonal and folliculogenesis disturbances in a polycystic ovarian syndrome rat model. 451–456 (2020).

Jahromi, B. N. et al. Comparing the effects of glycyrrhiza glabra root extract, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog (diphereline) in a rat model of endometriosis. Int. J. Fertility Steril. 13, 45 (2019).

Lakhanpal, P. & Rai, D. K. Quercetin: a versatile flavonoid. Internet J. Med. Update. 2, 22–37 (2007).

Bolouki, A., Zal, F. & Alaee, S. Ameliorative effects of Quercetin on the preimplantation embryos development in diabetic pregnant mice. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 46, 736–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14219 (2020).

Lesjak, M. et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Quercetin and its derivatives. J. Funct. Foods. 40, 68–75 (2018).

Vakili, S. et al. Effects of Quercetin and vitamin E on ovariectomy-induced oxidative stress in rat serum and tibia. Archives Biol. Sci. 72, 95–104 (2020).

Neisy, A., Zal, F., Seghatoleslam, A. & Alaee, S. Amelioration by Quercetin of insulin resistance and uterine GLUT4 and ERalpha gene expression in rats with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 31, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD18222 (2019).

Neisy, A., Koohpeyma, F., Khorchani, M. J., Karimi, F. & Zal, F. Quercetin modulates ovarian autophagy–related molecules and Stereological parameters in a rat model of PCOS. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 13, 9–16 (2023).

Boots, A. W., Haenen, G. R. & Bast, A. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 585, 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.008 (2008).

Xu, D., Hu, M. J., Wang, Y. Q. & Cui, Y. L. Antioxidant activities of Quercetin and its complexes for medicinal application. Molecules 24, 1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061123 (2019).

Qi, W., Qi, W., Xiong, D., Long, M. & Quercetin Its antioxidant mechanism, antibacterial properties and potential application in prevention and control of toxipathy. Molecules 27, 6545. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196545 (2022).

Rashidi, Z. et al. Quercetin protects human granulosa cells against oxidative stress via thioredoxin system. Reprod. Biol. 19, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repbio.2019.07.002 (2019).

Köse, S. A. & Nazıroğlu, M. Selenium reduces oxidative stress and calcium entry through TRPV1 channels in the neutrophils of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 158, 136–142 (2014).

Kirmizi, D. A. et al. Are heavy metal exposure and trace element levels related to metabolic and endocrine problems in polycystic ovary syndrome?? Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 198, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-020-02220-w (2020).

Srnovršnik, T., Virant-Klun, I. & Pinter, B. Heavy metals and essential elements in association with oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome—a systematic review. Antioxidants 12, 1398 (2023).

Wessels, I. Epigenetics and metal deficiencies. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 3, 196–203 (2014).

Kanafchian, M., Mahjoub, S., Esmaeilzadeh, S., Rahsepar, M. & Mosapour, A. Status of serum selenium and zinc in patients with the polycystic ovary syndrome with and without insulin resistance. Middle East. Fertility Soc. J. 23, 241–245 (2018).

Costello, R. B. et al. Perspective: the case for an evidence-based reference interval for serum magnesium: the time has come. 7, 977–993 (2016).

Das, J. et al. Exploring serum zinc and copper levels as potential biomarkers in polycystic ovary syndrome: A cross-sectional study from Northeast India. Cureus 16 (2024).

Kanafchian, M., Mahjoub, S., Esmaeilzadeh, S., Rahsepar, M. & Mosapour, A. J. M. E. F. S. J. Status of serum selenium and zinc in patients with the polycystic ovary syndrome with and without insulin resistance. Middle East. Fertility Soc. J. 23, 241–245 (2018).

Sousa, L., Oliveira, M. M., Pessoa, M. T. C. & Barbosa, L. A. Iron overload: effects on cellular biochemistry. Clin. Chim. Acta. 504, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.11.029 (2020).

Adamska, A., Łebkowska, A., Krentowska, A., Adamski, M. & Kowalska, I. The association between serum ferritin concentration and visceral adiposity estimated by whole-body DXA scan in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. 10, 873 (2020).

Virtanen, N. et al. Serum ferritin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 123, 1114–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2025.01.004 (2025).

Khaled, K. A., El-Sayed, Y. M. & Al-Hadiya, B. M. Disposition of the flavonoid Quercetin in rats after single intravenous and oral doses. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 29, 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1081/ddc-120018375 (2003).

Yang, C. Y. et al. Bioavailability and metabolic pharmacokinetics of Rutin and Quercetin in rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 13, 5 (2005).

Marreiro, D. D. et al. Zinc and oxidative stress: current mechanisms. Antioxid. (Basel). 6, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6020024 (2017).

Li, D., Jiao, J., Zhou, Y. M. & Wang, X. X. Epigenetic regulation of traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK) in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am. J. Transl Res. 7, 1152–1160 (2015).

Gravina, G. L. et al. Hormonal therapy promotes hormone-resistant phenotype by increasing DNMT activity and expression in prostate cancer models. Endocrinology 152, 4550–4561. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2011-1056 (2011).

Shiota, M. et al. Methyltransferase inhibitor adenosine dialdehyde suppresses androgen receptor expression and prostate cancer growth. J. Urol. 188, 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.2553 (2012).

Min, J. Y., Lim, S. O. & Jung, G. Downregulation of catalase by reactive oxygen species via hypermethylation of CpG Island II on the catalase promoter. FEBS Lett. 584, 2427–2432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.048 (2010).

Hurt, E. M., Thomas, S. B., Peng, B. & Farrar, W. L. Molecular consequences of SOD2 expression in epigenetically silenced pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Br. J. Cancer. 97, 1116–1123. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604000 (2007).

Hitchler, M. J. et al. Epigenetic regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase expression in human breast cancer cells. Epigenetics 1, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.1.4.3401 (2006).

Zappe, K. et al. Counteraction of oxidative stress by vitamin E affects epigenetic regulation by increasing global methylation and gene expression of MLH1 and DNMT1 dose dependently in Caco-2 cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 3734250. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3734250 (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Quercetin reverses docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer via androgen receptor and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.41686 (2020).

Ataabadi, M. S., Bahmanpour, S., Yousefinejad, S. & Alaee, S. Blood volatile organic compounds as potential biomarkers for Poly cystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): an animal study in the PCOS rat model. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biology. 226, 106215 (2023).

Kim, E. J., Jang, M., Choi, J. H., Park, K. S. & Cho, I. H. J. F. I. E. An I.proved dehydroepiandrosterone-induced rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): post-pubertal I.prove pcos’s features. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 735 (2018).

Wu, H., Zhao, B., Yao, Q. & Kang, J. Dehydroepiandrosterone-induced polycystic ovary syndrome mouse model requires continous treatments to maintain reproductive phenotypes. J. Ovarian Res. 16, 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01299-8 (2023).

Monsefi, M., Ghasemi, A., Alaee, S. & Aliabadi, E. Effects of anethum graveolens L. (dill) on oocyte and fertility of adult female rats. J. Reprod. Infertil. 16, 10–17 (2015).

Hafeman, D. G., Sunde, R. A. & Hoekstra, W. G. Effect of dietary selenium on erythrocyte and liver glutathione peroxidase in the rat. J. Nutr. 104, 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/104.5.580 (1974).

Shangari, N. & O’Brien, P. J. Catalase activity assays. Curr Protoc Toxicol 7, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471140856.tx0707s27 (2006).

Yarahmadi, A., Zal, F. & Bolouki, A. Protective effects of Quercetin on nicotine induced oxidative stress in ‘HepG2 cells’. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 27, 609–614 (2017).

Mashhoody, T., Rastegar, K. & Zal, F. Perindopril May improve the hippocampal reduced glutathione content in rats. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 4, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.5681/apb.2014.023 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, for their support. This research was funded by the Vice-Chancellor for Research Affairs at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran [Grant Number 14350].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Majid Jafari-Khorchani and Asma Neisy: Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Molecular analysis, Writing original draft, Review & editing. Mohammad Jalil Zare-Mehrjardi and Sanaz Alaee: Methodology, review and editing.Fatemeh Zal: Conceptualization, Visualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our research project has received approval from the Ethics Committee at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.AEC.1403.010).

Inform consent

All the authors of this manuscript declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jafari-Khorchani, M., Neisy, A., Alaee, S. et al. Quercetin modulates the interplay between DNMT gene expression, oxidative stress, and trace elements in DHEA-induced polycystic ovary syndrome rat model. Sci Rep 15, 34770 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18635-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18635-1