Abstract

To address the challenges of difficult rock excavation and low mechanical breaking efficiency in vertical shafts, a gravity-driven shaft tunneling machine with improved adaptability for medium-hardness rock tunneling has been developed. By integrating numerical simulation and field testing, this study clarifies the dynamic rock-breaking mechanism of the cutter under the combined action of gravitational force and the tunneling machine’s rotational force. The approach aims to investigate the dynamic destruction process of rock under varying drum rotation speeds, analyzing rock crack development, crushing characteristics, and the variation laws of the cutter’s rolling and normal forces. Research results indicate that once the cutter of the new shaft tunneling machine penetrates the rock, driven by its self-gravity and the machine body’s rotational force, the tensile and shear stresses exerted on the rock exceed its inherent tensile strength, compressive strength, and shear strength thresholds. This leads to rock disintegration and separation from the main rock structure. The findings provide an effective reference for actual shaft construction projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the construction of roadways, tunnels, shafts, and other projects, rock breaking primarily relies on mechanical methods and explosion processes. The mechanical method, renowned for its safety, high efficiency, and low investment, is widely adopted in roadway and tunnel engineering. However, in the field of shaft boring construction, mechanical technologies remain relatively archaic, with mechanization levels stagnating at 1990s standards1,2. Facing the demands of ultra-deep, super-large cross-section shafts under complex geological conditions3,4obsolete mechanical equipment has become a critical bottleneck, severely restricting the progress of vertical shaft construction5,6.

The traditional vertical shaft tunneling machine relies on cylinder support against the vertical rock wall to effect rock breaking. However, this approach requires the rock wall to have appropriate hardness and stability to withstand the significant self-gravity of the tunneling machine. Additionally, the process necessitates pre-excavating downward guides within the shaft for removing broken rock debris, leading to a construction process that is complex, discontinuous, and lacks versatility for diverse vertical shaft construction scenarios7.

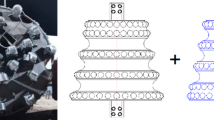

To address the limitations of existing equipment and shaft construction challenges, a gravity-driven shaft tunneling machine has been developed. This novel gravity shaft tunneling machine drives the drum to rotate through the vertical shaft, leveraging its self-gravity and the rotational force generated by cutter rolling to fracture the rock, enabling the boring operation. The rear drive mechanism’s drum assembly rotation propels the tunneling machine forward and steers its movement, completing shaft project construction (Fig. 1).

Characterized by flexible operation, rapid construction, continuous digging capability, and strong stratum adaptability, this equipment sets a new standard for vertical shaft engineering. Moreover, such technological innovation paves the way for groundbreaking rock-breaking methodologies in vertical shaft construction.

Currently, scholars have conducted extensive research on enhancing the rock-breaking efficiency of heading equipment cutters, yielding valuable results applied in tunnel excavation, mine shaft construction, and related projects. Their findings revealed that, for the same rock type, the degree of crushing is directly proportional to the cutter’s cutting force magnitude. Additionally, when the cutting force is constant, the crushing degree is inversely proportional to the rock’s compressive strength. Li et al.8 performed a series of true triaxial unloading stress path tests, integrating CT scanning technology to explore rock failure characteristics under diverse stress paths. This research provided a crucial foundation for understanding the evolution law of rock mass fractures in engineering applications. Drawing on meso-damage mechanics and the dynamic finite element method, Lastra G et al., Zhang et al., Qi et al., and Wang et al.9,10,11,12 simulated and analyzed the damage and fracture processes of rocks subjected to dynamic cutter loads. They elucidated how rock joint spacing and angle impact cutter rock-breaking efficiency, advancing the theoretical understanding of rock-cutting mechanics.

Scholars have conducted systematic research on pick structures. For example, Liao et al.13 proposed a novel theoretical formula for calculating the symmetrical peak cutting force in planar cutting slots by investigating the impact of pick half-cone angles on rock failure. They also employed RFPA2D for numerical simulations of rock cutting, revealing that the propagation speed of rock cracks under cutter action is a primary factor influencing rock failure. Xiao et al.14 established a numerical model of rock breaking via pick impact penetration using the continuous–discontinuous element method (CDEM), analyzing how different penetration angles affect pick rock-breaking performance. The results indicate that a smaller penetration angle correlates with a higher degree of rock fragmentation. Dong et al.15 used the particle flow simulation software PFC2D to model single-tooth cutting of rock as a granular material, deriving the variation law of the pick’s three-dimensional force with cutting parameters and the characteristics of debris ejection.

In these studies, the horizontal rock-cutting process by cutters is often idealized as vertical cutting. However, research on simulating the damage process of cutters rolling and intruding into rock under varying drum rotation speeds remains limited16,17. Specifically, there is a scarcity of analyses on the rock crushing process when cutters are subjected to the combined action of self-gravity, drum rotational force, and resultant rolling/normal forces18,19,20.

Based on the novel rock-breaking mechanism of the new shaft boring machine, this paper employs coupled finite-element analysis software to simulate the rock-breaking process of its rolling cutters at different drum rotation speeds. The methodology involves:

-

1.

Establishing a cutter-rock interaction model using SolidWorks;

-

2.

Performing mesh generation, material parameter setting, motion definition, and constraint configuration via HyperMesh;

-

3.

Conducting numerical calculations, cutter stress field visualization, and data processing with LS-DYNA.

Through comparative analysis of rock crushing morphology and specific energy consumption, the dynamic rock damage mechanism is investigated. Furthermore, field tests are conducted to analyze the rock-breaking distance, penetration depth, and fragmentation range of rolling cutters under different rotation speeds. By integrating simulation and test data, this study reveals the dynamic rock-breaking mechanism of the new shaft boring machine across varying drum speeds, bridging the gap in existing research on gravity-rotational coupled rock cutting.

Description of the numerical model

Analysis of the process of rock breaking of cutter teeth

The new shaft tunneling machine comprises a hydraulic mechanism, a driving mechanism, and a boring mechanism (Fig. 2). Four groups of drums are symmetrically positioned on the crossbeam of the boring mechanism, with multiple cutters evenly distributed along each drum. Leveraging the equipment’s self-gravity, the rolling and normal forces generated by drum rotation are transmitted via the drums to the cutters. When the force exerted by the cutters on the rock exceeds the rock’s compressive and shear strength thresholds, the cutters penetrate the rock, inducing numerous cracks in the vicinity of the contact points and causing rock detachment.

As the drums rotate, the cutters continuously roll to break the rock, prompting further cracking of the surrounding rock and ultimate formation of small fragments. Rock failure under the influence of a rotating drum is a highly complex dynamic process, significantly impacting rock-breaking efficiency. Thus, investigating the cutter’s rock-breaking mechanism under rotating drum conditions is of paramount importance for optimizing operational performance.

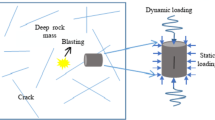

The geometry of the cutter directly influences the rock-breaking efficiency of the tunneling machine. To minimize wear and enhance efficiency, a conical design is adopted, which facilitates the application of concentrated stress to the rock, promoting shear and tensile fracture21. This study further investigates the stress distribution law of rock under the action of the cutter indenter, verifying the correctness and rationality of the internal stress distribution at different penetration stages by analyzing the interaction mechanism between the rolling cutter and rock. When the cutter tip indenter contacts the rock, an equivalent normalized concentrated force is applied to an infinite elastic body. Using elasticity theory, the stress distribution within the body under the normalized concentrated force is calculated, as illustrated in Fig. 3. A Cartesian coordinate system is established with the normal force concentration point as the origin, enabling the derivation of stress component distributions within the body under the action of the normal concentrated force F2223.

In the formula, σ denotes the stress (MPa), with tensile stress defined as positive and compressive stress as negative; F represents the normal concentrated force (N); v is Poisson’s ratio (dimensionless); x, y, and z are the Cartesian coordinates of any point in the plane.

When an infinitely long line load acts in the plane, the stress components within the rock are derived as follows:

In the formula, q is the homogeneous load per unit length, N/m2.

According to Eq. (7), the distribution of the internal stress σz in the rock under the action of the line-averaged load q can be derived. The normal stress within the rock propagates as stress waves spreading downward and radially, exhibiting a symmetric distribution pattern. The stress magnitude is extremely high in the rock-cutter contact area, while it follows an exponential decay trend with increasing distance from the cutter’s action point. In rock-breaking efficiency evaluation, specific energy SE (J/mm3) is commonly adopted as a key metric in tunneling engineering, defined as the energy consumed by the cutter to excavate a unit volume of rock24,25. This parameter simplifies the model by excluding the influence of rock fragment size: a smaller SE value indicates lower energy consumption for rock breaking and higher operational efficiency.

In the formula, SE is the specific energy of rock breaking (J/mm3), WN is the work performed by the combined force of the cutters (J), Fy is the normal force (kN), Fz is the rolling force (kN), P is the depth of intrusion, D is the rolling distance of the cutters to break the rock (mm), and V is the volume of the broken rock (mm3.

Establishment of a 3D model

Before performing the finite-element analysis of cutter rock-breaking, the drum, cutter, and rock were initially modeled in 3D using SolidWorks software. The model simplification adheres to the principle of maintaining key mechanical characteristics while minimizing calculation time26. Additionally, the drum, cutter, and rock models were scaled down at a 1:2 ratio, which reduces computation time and enhances analysis efficiency in HyperMesh and LS-DYNA finite-element software. The cutter has a length of 103 mm and a tooth-body end-face diameter of 20 mm, while the drum has a diameter of 580 mm with multiple cutters arranged at equal circumferential spacing. The cutter rock-breaking model and its dimensional specifications are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Selection of material parameters

The material parameters were defined in HyperMesh software. The cutter is fabricated from a novel titanium alloy with a density of 7900 kg/m³, elastic modulus of 270 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. For rock materials (e.g., mudstone and sandstone), parameters are based on the original HJC constitutive model27. Compressive and tensile strength parameters were derived from uniaxial unconfined compression tests and splitting tests. Dynamic compression and dynamic splitting tests were conducted using the Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) test to calibrate the original HJC parameters. By comparing the differences between static and dynamic parameters and optimizing parameter values, the experiment is shown in Fig. 5. The optimized rock model parameters based on the HJC framework are summarized in Table 1.

In this equation, ρ denotes the rock material density; \(\:G\) is the shear modulus; \(\:N\) represents the pressure hardening index; fc is the rock compressive strength; \(\:T\) is the rock tensile strength; \(\:{S}_{max}\) is the maximum dimensionless strength coefficient of the rock; \(\:{P}_{c}\) is the rock crushing pressure; \(\:{D}_{1}\) and \(\:{\upepsilon\:}{f}_{min}\) are material damage parameters; \(\:{K}_{1}\) are \(\:{K}_{2}\) are the material pressure parameters; \(\:{f}_{s}\) indicates the rock failure type.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, HyperMesh software is employed to configure model parameters, enabling refinement of the cutter’s vertical penetration into the rock formation. The simulation of rock breaking by the cutter has a calculation duration of 0.3 s with a time step of 9 × 10⁻⁶ s, optimizing computation time while ensuring data rationality. To realistically model stress propagation within the rock, the rock model’s upper surface is defined as a free boundary, the left/right and lower surfaces utilize non-reflective boundaries, and the front/back surfaces adopt a zero horizontal displacement boundary. The effect of rock self-weight is excluded from the analysis28,29.

Results and discussion

Rock damage processes in dynamic rock breaking by cutters

Based on field conditions, numerical simulations of the rock failure process were conducted at a drum horizontal translation speed of 20 mm/s. The objective was to analyze the stress variation laws and damage characteristics of rock during the cutter’s rolling penetration, considering the combined effects of the gravity shaft tunneling machine’s self-gravity and drum rotational forces at different speeds. Simulation results show that when the new shaft tunneling machine is stationary, only a small portion of the cutter contacts the rock surface, subjecting the rock to significant vertical concentrated forces. At this stage, the rock’s microcracks and pores remain in a closed compressed state, as depicted in Fig. 7(a). When the cutter tooth rolls into the rock, significant color variation in the simulation indicates that the rock-cutter contact zone experiences intense compressive and shear stresses, triggering crack initiation.

As the cutter continuously rolls to break the rock, the damage evolution rate of the rock’s internal structure accelerates, eventually leading to material yielding30,31,32. As depicted in Fig. 7(b) and Fig. 7(c), with the rolling cutter’s continuous penetration, the rock’s mechanical load-bearing capacity declines rapidly, culminating in catastrophic failure. At a specific depth of cutter rolling penetration, the stress contour color variation in the rock-cutter contact zone becomes pronounced, and the area of failed elements expands, as illustrated in Fig. 7(d). This observation indicates that the rock enters the structural and geometric failure stage, exhibiting prominent principal cracks and a broader rock fragmentation zone33. Once the rock’s structural damage reaches the critical damage threshold, it undergoes global failure, as evidenced by the complete disintegration of its mass.

In the finite element method rooted in continuum mechanics, the rock model is assumed to be spatially continuous. To simulate element disappearance or complete rock failure during damage fracture, LS-DYNA incorporates an element deletion function. This function triggers when the tensile stress applied to the rock exceeds the critical threshold of maximum principal stress, equivalent stress, or shear stress, removing the failed model parts from the working mechanism simulation.

Rock damage induced by cutter compressive and shear stresses is visualized in Fig. 8. Stress magnitudes are distinguished by color gradients in the contour plot, revealing that the rock experiences greater compressive stress than shear stress. This phenomenon arises because continuous cutter rolling penetration causes significant crushing, plastic deformation, and damage in the contact region. Theoretically, shear stress is the primary mechanism for rock fragmentation; however, damaged rock requires less shear stress to break, explaining the smaller shear stress values observed in the contour plot.

The peak of rock-breaking force strictly aligns with the spatial distribution of cutting teeth (arranged at 40° intervals) and the rotation angle of the drum, forming a multi-peak cycle within 360°. When the cutter teeth penetrate the rock at a 0° rotation angle, the breaking force surges abruptly to its peak. At this stage, the rock, subjected to the maximum force, generates multiple fractures. The crack network formed by initial fragmentation reduces the mechanical demands for subsequent rock breaking, leading to a decreasing trend in peak force—an outcome that embodies the “first hard, then easy” principle of rock breaking. When the drum rotation angle increases by multiples of 40°, the cutter penetrates the rock again, and the force rises to the peak value once more. Then, due to drum rotation, the cutter gradually stops contacting the rock, and the force trend tends to stabilize, as shown in Fig. 9.

Data analysis of simulation results

The rotational speed of the drum significantly influences cutter rock-breaking efficiency. Based on field conditions, drum rotation speeds of 25–40 rpm were set for simulation analysis. The continuous rock-breaking process of rolling cutters can be modeled as a cyclic mechanism, where multiple cutters repeatedly roll through a full rotation to fracture the rock. Specifically, a segment of the cutter’s rolling rock-breaking process within the simulation time range of 0–0.3 s was selected as the research object. LS-DYNA finite-element software was employed to derive the stress variation contours during rock damage.

Under different drum rotation speeds, the cutter-rock contact zones and failure areas exhibit distinct stress contour patterns and failed element distributions. The color gradient of the contours reflects varying stress magnitudes: higher stress appears in regions close to the cutter’s action area, while stress gradually diminishes with distance. A larger failed element area indicates a longer cutter rolling distance and more severe rock fragmentation. Stress contours propagate downward and radially from the failure sites, demonstrating stress wave diffusion.

Drum rotation speeds of 25 rpm, 30 rpm, 35 rpm and 40 rpm correspond to cutter rolling distances of 21.02 mm, 31.11 mm, 57.65 mm and 63.24 mm, respectively. Stress analyses within and around fragmented zones show that increasing drum speed enhances rock crushing severity, stress magnitude, and cutter rolling distance, thereby extending the rock-breaking range. Notably, when the speed increases from 35 to 40 rpm, the cutter rolling distance grows by only 8.8%, accompanied by negligible stress variation and marginal efficiency gains in rock breaking, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

To further analyze the influence of drum rotation speed on cutter rock-breaking, dynamic numerical curves were generated through numerical simulations using HyperMesh and LS-PrePost software. The cutter’s penetration process involves uninterrupted shedding of rock fragments in alternating sizes. Between shedding events, the cutter continuously advances to crush rock at the contact interface, with debris expelled from the dense core region. The breaking force increases as the cutter contacts and crushes the rock, gradually decreases during small-fragment shedding, and drops to zero after each unit shedding cycle. The size and timing of dense core formation and shedding are non-deterministic, resulting in an irregular fluctuating force curve.

A 0.3-second period is selected from the cutter’s repetitive rolling rock-breaking process. The cutter’s rolling force \(\:{F}_{z}\) and normal force \(\:{\:F}_{y}\) are key factors in studying the effect of drum rotation speed on rolling rock-breaking efficiency (the lateral force \(\:{F}_{x}\) is smaller and generally negligible). The force variations induced by drum rotation are shown in Fig. 11.

As depicted in Fig. 12, the cutter requires different force magnitudes to break rock under varying drum rotation speeds. Perform at least three simulation studies and calculate the average. At drum speeds of 25 rpm, 30 rpm, 35 rpm and 40 rpm, the maximum normal force \(\:{\:F}_{y}\)values are 1332 N, 1222 N, 1266 N and 1924 N, respectively, while the maximum rolling force \(\:{F}_{z}\) values are 2402 N, 1638 N, 2320 N and 4547 N. The respective maximum errors are 30 N and 27 N. With increasing drum speed, both the normal and rolling forces exhibit a non-monotonic trend of first decreasing and then increasing. A critical factor governing this trend is whether the cutter performs secondary fragmentation of rock debris after initial crushing, which influences the subsequent force fluctuations.

Figure 11 illustrates that the variation pattern of rolling and normal forces during cutter penetration is irregular, characterized by large amplitude between the force maxima and minima. Notably, the peak rolling force is significantly greater than the peak normal force, indicating that the Z-direction force constitutes the primary resistance during cutter intrusion into rock.

Numerical simulation software was employed to calculate the cutter’s rock-breaking volume at drum rotation speeds of 25–40 rpm, yielding values of 515 mm³, 743 mm³, 2327 mm³, and 2506 mm³. The maximum error is 35 mm³. Using Formula (7), the specific energy for rock-breaking under numerical simulation was computed. The results show that at 25 rpm, the specific energy is 20.1 J/mm³; as the speed increases to 30 rpm, 35 rpm and 40 rpm, the specific energy values are 13.4 J/mm³, 7.9 J/mm³ and 14.5 J/mm³, respectively. The curves of rock-breaking volume and specific energy are plotted in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13, increasing drum rotation speed correlates with larger rock-breaking volume and higher destruction severity, accompanied by a gradual decrease in cutter specific energy. This indicates that the energy consumed per unit volume of rock broken by the rolling cutter is reduced, signifying improved rock-breaking efficiency. Notably, the specific energy exhibits an inflection point at a drum speed of 35 rpm, reaching a minimum of 7.9 J/mm³. However, at 40 rpm, specific energy increases due to insufficient cutter force to generate large rock chips. The cutting force fails to produce adequate chip size, preventing energy consumption from decreasing. Consequently, specific energy does not decline with further increases in drum rotation speed beyond 35 rpm.

Simulation tests with similar materials in the field

The rock-breaking targets of the new shaft tunneling machine include mudstone, sandy mudstone, partial sandstone, and other rocks with medium hardness or below. Since the initial damage defects in natural rocks are difficult to quantify, C35 concrete was selected as the test material to reduce the randomness in the physical property distribution of the test objects and improve test repeatability. In line with the similar material theory, C35 concrete was chosen because its compressive strength and other physical-mechanical properties are comparable to those of sandy mudstone, sandstone, and other medium-hardness or softer rocks. The mechanical property parameters of the specimens were measured through uniaxial compression and splitting tests, as presented in Table 2.

Test program for concrete breaking by cutters

To validate the existence of an optimal drum rotation speed for cutter rock-breaking, the test used drum speeds matching those in numerical simulations as the variable. A high-speed camera was employed to record the cutter rock-breaking process, enabling observation of rock damage severity and fragmentation extent.

The cutting mechanism is equipped with a hydraulic motor providing 35 kN·m torque, sufficient to drive the cutter for rock-breaking, as shown in Fig. 14(a). The apparent volume method was employed to determine the volume of crushed stones. Initially, the crushed stones were submerged in water until they reached saturation. After removal from the water, any excess surface moisture was carefully wiped off using a damp cloth. Multiple sets of experiments were conducted, and the average value was calculated to minimize potential errors in measurement. The Lt425 is a 4-megapixel USB3.0 industrial camera with 5.5 μm² pixels, offering 2048 × 2048 resolution at a high frame rate of 90 fps. This configuration enables precise recording and measurement of the cutter’s rolling distance and rock-breaking depth, as illustrated in Fig. 14(b).

Process and results of the cutter rock-breaking test

As shown in Fig. 15: At a drum rotation speed of 25 rpm, the rock surface exhibits minimal fragmentation, with a cutter penetration depth of 8.5 cm. Increasing the speed to 30 rpm leads to more rock fragments, an expanded damage zone, and a penetration depth of 10 cm. At 35 rpm, rock fragmentation significantly increases with smaller debris, a broader damage area, and a deeper penetration of 12.5 cm, witch driven by the drum’s accelerated rotation. This correlates with higher rolling force, normal force, and rock damage depth. When the speed increases from 35 to 40 rpm, both cutter penetration depth and rock damage range show no significant change, indicating marginal improvements in rock-breaking efficiency.

To further validate the test results, numerical simulation data were compared with field rock-breaking test data. The differential rate of the cutter’s rolling rock-breaking distance and the growth rate of cutter penetration depth were calculated using Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively.

In the equations, \(\:{L}_{1}\) denotes the measured cutter rolling rock-breaking distance (mm); \(\:{L}_{2}\) denotes the simulated cutter rolling rock-breaking distance (mm), and δ represents the differential rate of the cutter rolling rock-breaking distance (%).

Additionally, ∆ represents the growth rate of cutter penetration depth (%), and \(\:{H}_{i}\) denotes the cutter penetration depth corresponding to various drum rotation speeds (cm).

The numerical simulation breaking distances of 21.02, 31.11, 57.65, and 63.24 mm, and the field test breaking distances of 25, 40, 62, and 70 mm were substituted into Formula (10). By substituting the field test breaking depths of 8.5, 10, 12.5, and 13 cm into Formula (11), the differential rate curves of the cutter’s rolling breaking distance and the growth rate curves of the penetration depth were obtained, as shown in Figs. 16 and 17, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 16, the growth rate of the cutter’s rolling distance peaks when the drum rotation speed increases from 30 rpm to 35 rpm, whereas the growth rate diminishes notably from 35 rpm to 40 rpm. Comparative analysis of test and simulation data reveals a low average differential rate of 16.4%, indicating strong consistency between numerical results and field tests. This finding validates the accuracy of the numerical model in reflecting the mechanical properties of the test specimens.

Figure 17 shows that at 40 rpm, the cutter’s rock penetration depth reaches 13 cm—52.9%, 30.0%, and 4.0% deeper than at 25, 30, and 35 rpm, respectively. However, the rate of increase in penetration depth decelerates with rising drum speed. Notably, the growth rate from 35 to 40 rpm is only 4.0%, demonstrating marginal depth increment in this speed range.

To further verify the rock-breaking efficiency of the cutter at different drum rotation speeds, the field test rock-breaking volumes of 42,500, 80,000, 155,000, and 182,000 mm³, along with the cutter normal forces of 89, 94, 100, and 123 kN, were substituted into Formula (9) to calculate the specific energy. The specific energy curve is plotted in Fig. 18.

As shown in Fig. 18, the rock-breaking specific energy at a drum rotation speed of 25 rpm is 17.8 J/mm³. Notably, at 30 rpm, 35 rpm and 40 rpm, the specific energy values are 11.8, 8.1, and 8.8 J/mm³, respectively. From 25 rpm to 35 rpm, the specific energy decreases with increasing drum speed, reaching the minimum at 35 rpm. This trend aligns with the simulated rock-breaking specific energy results.

The primary reason for the increase in the specific energy required for rock breaking is that the growth rate of energy consumption outpaces that of the effective breaking volume. On one hand, there is a significant rise in ineffective energy expenditures, such as those associated with friction, cuttings transport, and vibration. On the other hand, a mismatch between rotational speed and rock-breaking efficiency results in heightened energy demands for effective crushing.

Under dynamic impact loading, the rock mass in front of the cutting teeth is dominated by tensile fracture, with energy primarily expended to overcome the rock’s surface energy. The variation in specific rock-breaking energy essentially reflects the dynamic matching relationship among “impact frequency, rock mass response, and energy distribution”: the low-speed stage is limited by static crushing efficiency, the high-speed stage is constrained by a surge in dynamic energy consumption, while the rotational speed range around 35 rpm achieves mechanical adaptation between the impact loading and the rock mass’s crushing characteristics.

Conclusion

(1) The cutter of the drum in the gravity shaft tunneling machine penetrates the rock under the combined action of the machine body’s self-gravity and the rolling force and normal force generated by drum rotation. When the tensile and shear stresses experienced by the rock exceed its inherent tensile and shear strength, the rock cracks and detaches from the rock mass. As the drum rotation speed increases, the cracks and damage area of the rock gradually expand, ultimately leading to rock failure due to tensile and shear forces.

(2) The rock-breaking process is characterized by irregularly fluctuating loads, as the cutter does not maintain continuous contact with the rock in either the normal or rolling directions. Consequently, there is a significant disparity between the peak values of the cutter’s normal force and rolling force, with the rolling force being substantially higher. As the drum rotation speed increases, the force required by the cutter to crush the rock exhibits a trend of first decreasing and then increasing.

(3) For the rock materials used in the experiment, there exists an optimal drum rotation speed that minimizes the specific energy of rock breaking and maximizes rock-breaking efficiency. Therefore, when determining the penetration depth, high-efficiency rock breaking can be achieved by optimizing the drum rotation speed. Additional research is required for materials exhibiting substantial internal variations.

(4) Through a combined analysis of the field test for the gravity shaft tunneling machine’s rolling cutter rock-breaking, the differential rate of rolling distance (δ), growth rate of penetration depth (∆), and specific energy of breakage (SE) were evaluated. This analysis explores the variation laws of rock damage range and crushing depth, facilitating an in-depth and comprehensive exploration of the cutter’s dynamic rock-breaking mechanism.

Data availability

In response to the request for data availability, interested parties seeking access to the data from this study should contact the Professor Chen. His contact details are as follows: Chen Xinming, 2210960141@qq.com. Professor Chen is the primary contact for all data-related inquiries and will facilitate the process of data access in accordance with the journal’s policies and any relevant data sharing agreements.

References

Xiong, C. et al. Characteristics and mechanism of rock breaking by conical PDC teeth. Rock. Soil. Mech. 44, 2432–2444 (2023).

Song, Y., Fan, B. & Wang, H. P. Research on shear mechanics modeling of anchored jointed rock body considering normal stress and rock strength. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 42, 1325–1335 (2023).

Yuan, W. & Li, J. C. Research on the effect of shear rate on the frictional behavior of flat nodules and its mechanisms. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40, 3241–3252 (2021).

Jiao, H. Z. et al. Solidification/Stabilization mechanisms of heavy metal ions in cemented paste backfill for green mine operations: A review. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-025-3231-6 (2025).

Wang, S. F. Research on cutting characteristics of deep hard rock and nonexplosive mechanized mining. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40, 1080 (2021).

Li, H. B., Feng, H. P. & Liu, B. Study on strength behaviors of rock joints under different shearing deformation velocities. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 25, 2435–2440 (2026).

Xu, H. L., Zhu, W. Y. & Song, Y. M. Experimental study on deformation and failure evolution characteristics of rock with weak intercalation. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40, 2402–2410 (2021).

Li, Z. L. et al. Study on unloading characteristics and fracture characteristics of rocks under different true triaxial paths. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 39, 480–488 (2022).

Lastra, G., Jokovic, V. & Kanchibotla, S. Understanding the impact of geotechnical ore properties and blast design on comminution circuits using simulations. Miner Eng. 170.1, 107001 (2021).

Zhang, J., Xi, X., Guo, Q. F. & Wu, X. H. Meso multiphase particle flow simulation of granite failure with preexisting crack. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technology: Nat. Sci. 49, 79–85 (2021).

Qi, Q. L., Yang, Y. X., Niu, S. W., Chen, L. & Chen, X. Experiment and simulation research on rock damage mechanism in tooth indentation. Processes 11, 464 (2023).

Wang, H. Investigation of the Influence of Cutting Parameters on Conical Pick Cutting Performance and Rock Damage. Machines, 10 (2022).

Liao, Z. Y., Liang, Z. Z., Yang, Y. F., Wang, Y. & Tang, C. A. Numerical simulation of fragmentation process of jointed rock mass induced by a drill bit under dynamic loading. Rock. Soil. Mech. 35, 1147–1155 (2013).

Xiao, J. C., Lu, J. J., Zhou, H., Xu, F. T. & Feng, C. Study on the influence of penetration angle on rock breaking performance and geometric arrangement of the pick. Rock. Soil. Mech. 43, 3372–3384 (2022).

Dong, L., Zhang, H., Lu, J. S. & Shi, R. M. Research on cutting characteristics of rock single tooth based on force chain and prediction of cutting force. Rock. Soil. Mech. 43, 3036–3046 (2022).

Jiao, H. Z., Zhang, Q., Yang, Y. X. & Yang, T. Y. Effect of interface roughness on mechanical properties of layered cemented tailings backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 8, 409 (2023).

Chen, X. M. et al. The new gravity vertical shaft continuous tunneling machine rolling cutter rock breaking mechanism. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 39, 576–583 (2022).

Zhang, H. F. et al. Effect of tool plunge depth on the microstructure and fracture behavior of refill friction stir spot welded az91 magnesium alloy joints. Int. Journal Minerals Metall. Materials. 28, 11 (2021).

Chen, X. M. et al. Characterization of fiber distribution based on search cone algorithm and enhancement mechanism for BFRC. Mater. Rep. 35, 4061–4066 (2021).

Xue, Y. D., Zhou, J., Zhao, F. & Li, X. Research on rock breaking mechanism of TBM hob based on MatDEM. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 41, 337–346 (2020).

Ding, B. et al. Investigating grouting body nonuniform expansion in anisotropic underground soil mechanics. Sci. Rep. 14, 32004 (2024).

Tan, H., Ji, H. G., Zeng, Z. Y. & Liu, Z. Q. Analysis of optimal weight on bit of tapered hob based on characteristic particle size of hard and brittle rock. J. Geotech. Eng. 2, 782–789 (2020).

Liu, W., Qu, Z. & Wang, P. Study of Rock Damage Behavior Based on Configurational Mechanics. Chemistry and Technology of Fuels and Oils (2023).

Xi, Y., Wang, W., Zha, C. Q., Li, J. & Liu, G. H. Numerical investigations on rock breaking mechanism and parameter influence of torsional percussive drilling with a single PDC cutter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 210, 110077 (2022).

Shen, T. et al. Numerical simulation and optimization study of faceted blasting in rock tunnel with Slit charge package. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 37, 674–680 (2020).

Li, T. B. et al. X. Creep damage constitutive model of rock based on the mechanisms of crack-initiated damage and extended damage. Undergr. Space. 18, 2096–2754 (2024).

Fan, P. X., Wang, M. Y. & Fang, X. Discussion on boundary conditions and its simulation method of deep engineering model test. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 33, 146–151 (2016).

Cheng, H. G., Yang, X. B. & Lan, Y. Investigating rock mutation characteristics and damage state warning model based on energy conversion. Energy Sci. Eng. 3, 12 (2024).

Zhai, S. F., Cao, S. H., Zhou, X. P. & Bi, J. Numerical simulation study on the influence of confining pressure on rock breaking by TBM hob. J. Geotech. Eng. 41, 154–160 (2019).

Wang, Y. F., Jiao, H. Z., Li, Z. & Su, H. Characteristics of unloaded perimeter pressure strength and damage destruction of white sandstone. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 2787–2794 (2020).

Wang, Y. F., Su, H., Wang, L. P., Jiao, H. Z. & Li, Z. Comparative analysis of deformation and strength characteristics of three sandstones. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 1367–1374 (2020).

Guo, Y., Ren, G. Y., Yang, F., Yang, Y. & Dmitry, O. Bokov. & Irina N. Fardeeva. An analytical method to select appropriate linear and non-linear correlations on the effectiveness of penetration rate parameter towards mechanical specific energy. Energy Rep. 7, 3647–3654 (2021).

Chen, X. M. et al. Research on dynamic characteristics of cutter breaking frozen soil and optimal drum rotation speed of the new shaft tunneling machine. Sci. Rep. 14, 5807 (2024).

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52374121), the Central Plains Talents: Young Top Talents Found (z2023136) and the 14th Five-Year Plan Key R&D Projects Fund (2023YFC2907203).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X.F. conducted the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; C.X.M., J.H.Z., and Y.Z. participated in field sampling and experiment; Z.J.L. revised and finalized the manuscript. L.Y,. and C.J.F. provided experimental supports; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, XF., Chen, XM., Jiao, HZ. et al. Research on rock damage characteristics of gravity tunneling machine based on different rotational speeds. Sci Rep 15, 34920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18653-z