Abstract

This study investigates the integration of a Grid-Forming (GFM) Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) to enhance the stability of microgrids in the presence of high renewable energy penetration. The proposed GFM inverter, combined with BESS, significantly improves fault resiliency and oscillation stability compared to traditional Grid-Following (GFL) inverters. The GFM inverter enables fault ride-through (FRT), maintaining operational stability during grid faults with voltage recovery within 300 ms and frequency deviations limited to ± 0.5 Hz. The GFM-controlled system stabilized within 1 s during a 50% solar irradiance drop, supplying reactive power and inertial support, while the GFL inverter struggled to stabilize under a Short Circuit Ratio (SCR) of 0.423, leading to large voltage and frequency deviations. Additionally, during a 46% increase in load demand, the BESS under GFM control immediately compensated for the real power imbalance, demonstrating the crucial role of energy storage in improving microgrid stability. In contrast, the GFL inverter failed to stabilize under similar conditions. Simulation results using MATLAB/Simulink confirmed that the GFM inverter restored microgrid stability more effectively, with faster fault recovery and improved voltage regulation compared to GFL inverters. The implementation of an Energy Management System (EMS) optimized power flow between the PV, BESS, and grid, enhancing system efficiency and participation in energy markets. These findings validate the potential of GFM inverters, supported by advanced control strategies, to provide reliable, efficient, and sustainable microgrid operations, indicating their practical viability in future energy networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the pressures of climate change and the demands for cleaner energy and reliable energy supplies collide, so the role of microgrids is gaining traction as technology adoption, practical experimentation and business change drives the energy resilience agenda1. Microgrids, incorporating decentralized energy sources including, but not limited to, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, energy storage systems (BESS), and intelligent inverters, have been increasingly recognized as a suitable alternative to traditional utilities for local energy generation and consumption2. They can operate in the grid-connected and islanded mode, thus presenting a new paradigm for adapting to modern requirements3. Such grids are challenged with inherent intermittency, variability, and fluctuations of power (voltage, frequency) typical of most renewable sources, such as solar4. Grid stability, especially during fault conditions, and in transition stages between grid-connected and islanded modes, is one of the most critical challenges in the operation of microgrids5. That is, a system should be able to run through disturbances, and continue to operate during grid faults, as part of an approach towards the uninterrupted delivery of power and towards the stability of the main grid6. This feature is known as Fault Ride-Through (FRT), and it is very important for renewable-based microgrid systems7. But for the sake of arguing, GFM inverters and GFL inverters are the two essential parts that really affect the functioning and stability of a microgrid8. GFM inverters regulate voltage and frequency while the microgrid is in islanded mode, whereas GFL inverters synchronize with the utility grid and enables grid connected mode, which is important both for stability and fault tolerance9. These inverters, along with energy storage systems, help together to make up a strong architecture, providing the microgrid disturbances and reliable operation10.

A microgrid is a local energy grid where generation, storage and consumption can happen usually independently from the central grid or in parallel with it11. Microgrids can be explained at a basic level in terms of the processes that allow for various types of energy to be combined including solar PV, energy storage systems, and inverters, and poise the latter as being the general working principle of a microgrid12. With GFL inverters, in a normal operation connection with the main grid, the microgrid synchronizes with the grid while working together efficiently to transmit power. The microgrid should be able to “ride through” disturbances or faults of main grid, so that it does not have to disconnect13,14. Such fault resilience is achieved by advanced control strategies such as FRT to autonomously stabilize the voltage and frequency by the GFM inverter during islanding condition15. The GFM inverter operates like a synchronous generator, so it can contribute to system stability by providing voltage and frequency support. In the event of grid disturbances, microgrid can also control its active and reactive power by performing dynamic current control, dynamic voltage control, and frequency support, allowing the microgrid to function effectively within the electrical grid16,17. As well as fault ride-through, the use of energy management is key to the microgrid. Behavior of the EMS adjusts the operation of all components of the system (i.e. PV array, energy storage system, inverters) according to time outs of the conditions at given moment, allocating resource for usage or storage18,19. The EMS utilizes forecast tools and optimization procedures to ensure that stored energy is consumed at the most appropriate times, minimizing the risk of system collapse stemming from supply-demand mismatches20.

The control and monitoring framework presented in this paper, is an enhanced method for controlling distributed generation, with specific focus on the relationship between PV systems, BESS and the grid21,22. We will also delve into the operational principles and strategies used by GFM and GFL inverters to balance the grid and achieve fault tolerance23. Using dynamic control and optimization methods such as Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT), FRT strategies, and Droop Control, achieved enhanced energy management in the time domain, enabling reliable power generation, storage, and consumption24. Furthermore, we examine how the Microgrid Energy Management System (EMS) is crucial in optimizing how these distributed energy resources operate, including real-time forecasting, energy storage optimization, and demand response management25. Integrating these control methods leads to efficient operations, cost savings, and stability in the grid, even in case of faults or transient events26. With this increasing interest in microgrid control and optimization, the present study intends to provide further insight into the dynamic response of renewable energy-based microgrids under different fault conditions, contributing to the rapidly expanding literature on microgrid control and optimization27,28.

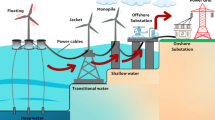

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the system under study. The system model consists of a photovoltaic (PV) plant and a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), both interconnected to the medium voltage (MV) network through a transformer. The PV plant employs inverters that operate at their maximum power point (MPP) using a phase-locked loop (PLL)-based control strategy in grid-following (GFL) mode. This allows the inverters to synchronize with the grid and ensure optimal power extraction. In contrast, the BESS inverter functions as a grid-forming (GFM) unit, regulated by a virtual synchronous machine (VSM)-based controller. The GFM controller enables the BESS to provide voltage and frequency support to the grid, maintaining stability during dynamic conditions and disturbances. This integrated approach ensures efficient energy management and enhances grid resilience.

Literature review

Microgrids are crucial for the optimal integration of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), including renewable energy sources (solar photovoltaic (PV) systems) and energy storage systems (BESS), to ensure the supply of reliable, stable, and sustainable power29. In recent years, numerous studies have focused on enhancing microgrid performance through the development of control strategies, fault tolerance mechanisms, and improved grid interactions30. Key concerns for the operation of microgrids include their stability, voltage and frequency regulation, as well as the optimization of energy storage and power distribution31. Microgrid stability is strongly influenced by the robustness of control systems capable of maintaining desired voltage and frequency levels despite varying operational conditions32.

The Grid-Forming (GFM) and Grid-Following (GFL) inverters are central components of the operational framework for microgrids. GFM inverters behave similarly to conventional synchronous generators (SGs) and are well-suited for standalone or island microgrids33. These devices operate independently of both voltage and frequency, enabling stable system operation during load or generation fluctuations. In contrast, GFL inverters synchronize with the utility grid, using it as a reference for frequency and voltage in grid-connected mode34,35. While GFL inverters are easier to design, their performance during grid disturbances is limited, making fault response a critical research area36. A variety of control techniques have been proposed to improve the performance of both inverters, with droop control being one of the most extensively researched methods. Droop control regulates active and reactive power by measuring voltage and frequency deviations, ensuring effective power distribution across multiple inverters in a microgrid and improving system stability during disturbances37,38.

Grid disturbances, such as faults, voltage sags, and frequency deviations, can cause islanded microgrids to lose power, representing a major challenge. A fault ride-through (FRT) capability is essential to preserve system stability during disturbances and prevent disconnection from the grid39,40. To improve the FRT abilities of microgrids, various fault detection and mitigation strategies have been proposed, including new algorithms that enable microgrids to detect faults and recover without disconnecting from the grid41,42. The adoption of Virtual Synchronous Machines (VSM) has also gained attention, as they simulate the dynamic characteristics of traditional generators, enhancing a microgrid’s ability to respond to frequency and voltage fluctuations43,44. This approach improves system stability and facilitates a smooth ride-through during disturbances45.

Recent research has focused on fault tolerance in microgrids, particularly through advanced coordination of GFM and GFL inverters. Hierarchical control architectures and real-time communication systems have been developed to effectively detect and prevent faults, enhancing the resilience of the microgrid during fault conditions46,47. The Microgrid Energy Management System (EMS) plays a pivotal role in optimizing energy generation, storage, and consumption across DERs such as PV systems and BESS. The EMS helps minimize energy costs while maintaining grid stability48,49. One of the key functions of the EMS is energy generation forecasting, which predicts solar energy production based on weather forecasts and adjusts the inverters accordingly50. Another crucial element of EMS is energy storage optimization, where BESS helps balance the grid by absorbing excess energy during high-generation periods and discharging during consumption surges or when renewable generation is low51. Algorithms are developed to optimize the charging and discharging cycles of BESS while minimizing wear on storage devices and ensuring load satisfaction52. Additionally, demand response management enables the EMS to adjust microgrid load in response to external grid signals or market pricing, optimizing system efficiency and contributing to demand-side management programs53.

Many microgrid applications require efficient energy resource management, supported by optimization algorithms that incorporate technical, economic, and environmental factors. These algorithms enable real-time decisions on power generation, storage, and consumption54. Optimization frameworks that combine economic inputs (e.g., electricity market prices) and environmental goals (e.g., reducing carbon emissions) provide a holistic approach to microgrid operation55. Techniques like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GA) have been used to address optimization problems, such as optimal sizing of energy storage systems and power generation units56. These methods improve microgrid operation schedules and overall system performance57. Furthermore, machine learning techniques, particularly Reinforcement Learning (RL), have shown promise in enhancing real-time decision-making within EMS by learning and optimizing microgrid operations based on reward feedback signals58.

Another area of recent research has focused on the integration of microgrids with the utility grid. Microgrids are operated in either mode, contain types of grid connected and not connected mode of power supply, Exchange of power with utility grid59. In this mode, microgrids can integrate into ancillary services like frequency regulation and voltage support. In the context of the energy market, microgrids can sell excess energy to the electrical grid or buy energy when generation is low60. Researchers like they have proposed optimization frameworks that allow microgrids to participate in power markets by considering electricity pricing, grid load demand and renewable energy prediction61. This further integrates microgrids into the energy marketplace, giving them a new revenue stream and improving their economic viability. This requires advanced communications and control systems to enable operation in parallel with the grid62. A communication framework for microgrid was proposed in that allows for real time monitoring and controlling of the microgrid which helps microgrid coordinate in response to grid fluctuations and help it in remaining stable63.

Research gap and contribution

Embracing state-of-the-art technologies such as solar PV systems and energy storage systems, microgrids have garnered considerable attention to properly support sustainable and resilient power systems. Even with the increasing interest and improving technology, there are still a few challenges that need to be solved to maximize the success of microgrids, especially regarding grid security, fault ride-through performance and energy management. Hundreds of academic papers are being produced every year in the field of microgrid control and integration. However, the interaction among parts of microgrid systems such as fault tolerance, dynamic control and optimal energy storage remains underexploited.

-

Inadequate integration of advanced inverter control strategies: They mainly address GFM or GFL strategies separately, overlooking their synergistic effects in practical applications. Additionally, the versatility in interfacing GFM and GFL inverters to provide reliability and fault resistivity, for example, in hybrid microgrid systems, has not been fully investigated.

-

Although FRT capabilities in microgrids have been considered by many studies, few studies have focused on the implementation of RESs and ESSs for microgrids under such conditions. Additionally, existing solutions are generally tailored towards isolated power systems and do not provide any real-time dynamic adjustments in the event of grid disturbances.

-

However, existing EMS of these microgrids have mainly focused on the optimization of grid-connected and islanded operation mode separately without providing the demand-side integrated approach for seamless balancing of grid-connected and islanded mode together with real-time fault detection and mitigation capabilities. Furthermore, in many systems, the predictive algorithms for forecasting energy generation and optimizing energy storage when disturbances occur have not yet been sufficiently developed.

-

Fault detection and mitigation mechanisms are important ways to ensure system resilience. However, available methodologies do not sufficiently address a unified hardware and software control approach. It also pays little attention to how BESS can dynamically support grid stability in the case of faults using advanced inverter control techniques.

This paper provides a well-consolidated framework on enhancing stability, fault ride-through as well as energy management of microgrids network emanated from renewable energy resources such as solar PV along with emerging energy storage systems. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

-

Development of a novel control strategy for Grid-Forming (GFM) and Grid-Following (GFL) inverters, improving fault tolerance and optimizing both voltage and frequency regulation within microgrids.

-

Design of a Fault Ride-Through (FRT) mechanism, enabling microgrids to remain operational during grid disturbances such as voltage sags, frequency dips, and faults, thereby enhancing grid stability. A dynamic control strategy is proposed which modifies active and reactive power at once during disturbances providing steady state operation and in the case of grid loss reconnection after fault.

-

Development of an integrated Energy Management System (EMS) that optimizes energy generation, storage, and consumption in both grid-connected and island modes, leveraging advanced forecasting models and real-time optimization algorithms.

-

Proposal of a real-time fault detection and mitigation algorithm, which ensures the system can detect disturbances and automatically activate fault ride-through protocols, improving system resilience and minimizing operational disruptions.

-

Introduction of an energy management framework that effectively integrates renewable energy sources with the grid, dynamically adjusting energy storage and inverter controls to ensure stable and energy-optimal operation under various operating conditions. Utilizing sophisticated forecasting models, and real-time optimization algorithms for energy storage management, the EMS ensures they operate at peak and cost-effective levels, especially when the grid is disrupted.

Research objectives

This study aims to propel the advent of a comprehensive paradigm to improve stability, fault ride through capacities and energy exchange of renewable-dominant microgrids with strong interconnectivity between energy sources.

-

To enhance the stability and fault ride-through capacity of microgrids by utilizing GFM and GFL inverters, ensuring reliable operation during grid events.

-

To develop a robust fault ride-through mechanism that allows the microgrid to function continuously during voltage sags and frequency deviations, with a fast recovery time post-fault.

-

To design an Energy Management System (EMS) that balances energy generation, storage, and consumption in real-time, ensuring optimal performance in both grid-connected and islanded microgrid configurations.

-

To create a fault detection and mitigation algorithm capable of identifying grid disturbances and activating the necessary protocols to prevent system disconnections and ensure reliable system performance during faults.

Article structure

Section 1 discusses the importance of microgrids and explains that using Grid-Forming (GFM) inverters allows solar PV-related systems to maintain their stability during various grid disturbances. Section 2 gathers information on the mechanisms of FRT, GFM inverter technology, ways to store energy and strengthening microgrids and suggests that there is room for improvement in solar PV use. Section 3 discusses how the system is configured for solar PV, BESS and GFM inverters and it covers how it’s tested by checking for voltage sags and short circuits using different control measures. In Sect. 4, it is shown that the new FRT technique helps to keep grid voltage and frequency more stable than the old methods tested. The discussion in Sect. 5 centers on difficulties related to flexible loads and complicated control systems and it offers suggestions for enhancing the coordination between inverters and the energy storage device. At the end, Sect. 6 presents the main results, underlines the benefits of improved GFM inverter controls for smooth microgrid running and proposes areas for future research into fault mitigation methods for bigger microgrids.

Mathematical modeling

General statement

This study presents a model for simulation and performance analysis of a solar PV system with an integrated form of a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) in a microgrid development. We implemented both GFL and GFM inverter resources into the model to compare how they would impact grid stability, fault tolerance, and overall system performance. The dynamic behavior among the PV array, BESS and the grid is characterized by the proposed model using a combination of electrical engineering laws and control systems knowledge. The output of the solar array is then modeled as a single-diode equivalent circuit described in Sect. 1. The equivalent mathematical equations of the inverter systems, and the grid connecting modes are used to model GFL and GFM operating modes of the inverter systems. The system also contains an MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) controller, that extracts maximum power from the PV system when environmental conditions (e.g. irradiance, temperature) vary. The battery storage is modeled as a dynamic element that stores energy during times with a high solar irradiance level and discharges the energy during times of low generation or high demand. MATLAB/Simulink is used for system simulation where the control algorithm can be implemented and the system can be tested for different faults and grid disturbances. Figure 2 represents salient parts of the proposed model and voltages across the PV array, battery storage system, inverters, and grid.

PV system

The single diode model of a PV cell’s equivalent circuit (Fig. 3) consists of a series resistance, a diode, a parallel resistance, and a current source. Equation (1) defined the I-V characteristics of the model, which includes two resistors and a diode, where the photocurrent delivered by the constant current source is denoted as \(\:{I}_{pv}\). The diode’s reverse saturation current is denoted by \(\:{I}_{0}\). The series resistor, represents losses in cell solder bonds, interconnections, junction boxes, and other similar components. The shunt resistor, ℎ, accounts for current leakage through the high-conductivity shunts across the p-n junction. The ideality factor, , indicates the diode’s deviation from Shockley’s diffusion theory. Thermal voltage of the solar cell can be described using Eq. 2, where K is affected by the cell numbers in series, Boltzmann constant K, charge q and temperature T. To match the behavior of the solar cell’s equivalent circuit findings, the equivalent circuit parameters must be adjusted.

The solar power plant consists of a photovoltaic (PV) array that generates 120 MW at 1000 W/m2 solar irradiance and \(\:{25}^{0}\) temperature. The PV array is connected to a boost converter, which is regulated by an MPPT controller. The number of cells connected in series within a panel is 150 and cells connected in parallel with a panel is 10. Two solar arrays, each produced 60 MW power. The number of panels in series per string is 120. Each string has the capacity to generate 0.25 MWp of power. The number of parallel strings is 200 to produce 30 MW power.

The PV array is connected to a boost converter which is managed by the MPPT controller. The MPPT algorithms provide instructions to the MPPT controller, helping it optimize the operating point to reach the Maximum Power Point (MPP). The study utilized the Perturb and Observe (P&O) algorithm. The MPPT utilizes the Perturb and Observe method to optimize the voltage across the terminals of the PV array for maximum electricity generation. An LC power filter on the AC side, along with a three-phase coupling transformer, can be adopted to link the inverter to the microgrid. The mathematical representation of a three-phase grid-connected PV system using a standard three-phase inverter can be described using the Eqs. (3–5).

where the voltages at the inverter side and inverter side denoted as simultaneously \(\:{V}_{a}\), \(\:{V}_{b}\), \(\:{V}_{c}\) and \(\:{V}_{ga}\), \(\:{V}_{gb}\), \(\:{V}_{gc}\). Current of the inverter outputs denoted as \(\:{i}_{a},\:{i}_{b},\:{i}_{c}\) and \(\:{L}_{f}\) and \(\:{R}_{f}\) are the LC filter’s inductor and resistor. The main role of inverter control is to efficiently transfer the maximum solar energy generated into the grid while also regulating the dc-link voltage. The outer loop controls the dc-link voltage, and the inner loop regulates the inverter output current. The MPPT fuzzy logic controller utilizes the error, and the voltage change as inputs. Voltage change and error can be estimate as

The output of the fuzzy logic controller, typically representing in Eqs. (6–7), a change in the duty ratio \(\:\varDelta\:D\) of the power converter can be determined by referencing a rule base table. This process involves calculating E and\(\:\varDelta\:V\) and converting them into linguistic variables. The effectiveness of fuzzy logic-based MPPT controllers in Fig. 4 across various environmental conditions is evident. However, this success largely hinges on the expertise of the user in constructing the foundation of rules.

BESS system

A grid-forming Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) integrated with a megawatt-scale solar PV system plays a crucial role in stabilizing and supporting the electrical grid. BESS model includes a battery unit, an L filter, an inverter, a DC-DC converter, and sensors for three-phase current and voltage. Through a two-stage power transformation procedure, the BESS system is network-integrable. Generating a voltage reference for the PWM generator, the control system in the BESS regulates the converter output. The number of series cells in the battery is 500 and each battery cell has 14-volt voltage. The energy capacity of the battery is 70 MWhr and the continuous power rating of the BESS is 580.82 W. This system includes advanced controllers, such as those based on virtual synchronous machines (VSM), which enable the BESS to emulate the characteristics of traditional synchronous generators. The BESS controller model consists of two controller methods. One is GFL BESS controller based on PLL with voltage and frequency support and other one is Grid-forming controller based on VSM. By actively controlling voltage and frequency, the grid-forming BESS ensures reliable operation and smooth integration of intermittent solar power into the grid.

Performance criteria for inverter-based resources (IBRs) as per IEEE 2800 standard

The IEEE 2800 standard outlines the performance requirements for inverter-based resources (IBRs), focusing on the voltage and frequency ride-through capabilities necessary for compliance64. These criteria ensure that inverter-based systems can withstand voltage and frequency disturbances without causing harm to the plant or the grid. Any undesired trip of the inverter-based resource (IBR) due to voltage or frequency disturbances is considered a violation of these standards. The ride-through functions are activated by sensing the voltage magnitude at the point of interconnection (POI), with lookup tables implemented in the plant controller. These functions ensure continuous operation or appropriate tripping in response to voltage and frequency disturbances, thus maintaining stability.

Figure illustrates the voltage ride-through requirements for IBR plants, detailing the different operational modes, including continuous operation for 30 min, permissive operation, and mandatory operation (Fig. 5). Figure 6 provides the frequency ride-through characteristics and the corresponding operational modes for IBR plants based on the frequency disturbances, as outlined in the IEEE 2800 standard. The voltage and frequency ride-through functions are implemented in the PV plant controller using lookup tables. These functions are activated by sensing the voltage magnitude at the point of interconnection (POI), as shown in Fig. 7.

Assessment of grid stability and fault ride-through capabilities

Grid stability (general statement with schematics)

Microgrids systems have the ability to operate independently from the global grid and it is crucially importance to maintain the stability of the whole system. The solar output is natural volatile and intermittent, thus also brings wild swing in the voltage, frequency, and output power to the grid that will negatively impact the performance of the grid. The latter stage is to evaluate grid stability in a given operating condition, during both in the normal operation and in transient disturbances or faults. The proposed model includes GFL and GFM Inverters to study their impact on the grid stability. Due to its unique design, GFL inverter can synthesis its own reference voltages autonomously which aids in the preservation of stability in the absence of utility grid. Whereas, GFM inverter responds to reference voltage of the grid during fault but work properly when the grid is still present. In this paper, the grid stability is evaluated in terms of monitoring simulations that present the behavior and reactions of the microgrid to acknowledgment of possible fault cases (voltage drops, frequency falls, power failure, etc.). Microgrid stability is a measure of that it can maintain (or restore) its voltage and frequency within prescribed limits, which also relies terminal behavior in Fault Ride Through (FRT). The depicts the general layout of the microgrid system, showing how the PV array, the battery energy storage system (BESS), inverters, and grid are interrelated. Solar PV array, which produces power depending on the local value of solar irradiance and temperature. The BESS absorbs excess energy and supplies it at times of low solar production or grid disturbance. During islanding or fault, the GFL inverter can only generate their own voltage and frequency reference structure. GFM inverter, which supports grid stability and responds to grid disturbances by changing its output.

Control strategics

However, effective controlling strategy needs to ensure the stability of the grid and the capability of fault ride-through (FRT), especially for microgrid based on renewable energy deployment. This model uses advanced control strategies to determine the behavior of both GFL and GFM inverters to maintain the system performance in normal and fault situations. This control strategy is employed for maximizing the power generation of the PV array as shown in Fig. 8 (a). The MPPT controller dynamically optimizes the working point of the PV inverter to harvest the peak available energy from the solar array for a range of irradiance and temperature scenarios. The GFL inverter provides voltage and frequency regulation during islanding conditions supporting the system autonomously in grid-forming mode This helps the microgrid system to still maintain stable operation even without the utility grid. FRT (Fault ride-through) control. The GFM inverter has an FRT strategy that guarantees that it will save the operation formally due to pricking GFM inverter control strategies. The FRT control enables the inverter to ride through transient faults by modifying its output power and staying in synchronization with the grid. Because this prevents the disconnected microgrid, the microgrid can help recover the grid.

In the grid following mode, a GFM inverter synchronizes to the voltage and frequency of the utility grid. In case of disturbances, the inverter can supply reactive power support, stabilizing the grid by compensating sudden swings in power demand or generation. The battery storage system is controlled by a BESS control strategy to charge the battery when there is surplus solar generation or discharge the battery when demand exceeds available solar generation. Dynamic energy management provides continuous displacement of power, so that even when the sun sets or the clouds obstruct it, output is stable, which is essential for a balanced grid. These control techniques enable the microgrid to achieve effective coordination of multiple distributed generators, providing both stable and reliable power supply and consumption.

Droop control

Droop control ensures the GFM inverter parallel operation. The voltage and frequency of the microgrid need to be managed by the BESS according to the droop control as shown in Fig. 8 (b). The droop control strategies of the system. The converter output in terms of active and reactive power can be represented using Eq. (8). For stability considerations, Eqs. (9–10) are used with a small power angle to operate generators, where a linear relationship between active and reactive power is established. Droop properties can be derived from this relation using Eqs. (11–12), where the ratio of BESS reactive and active power is governed by the droop coefficients n (reactive) and m (active).

PCC and inverters voltage angel are matched by PI controller and determined by \(\:{V}_{ref\:}and\:{Q}_{ref}\). The inverter’s phase and frequency match the PCC voltage, ensured for PWM generation. Droop control implemented this system and can be represented using Eqs. (13–14).

Where voltage, norm frequency, reactive and active power is estimated respectively by V, f, \(\:{Q}_{mease}\:and\:{P}_{meas}\). Reactive and Active power control allows independent adjustment of voltage and frequency amplitude.

Active/reactive power control

The grid-forming converter’s reactive and active output powers are adjusted to track the power references. Figure 8 shows the active and reactive power control as shown in Fig. 8 (c). The PI controller measured the reference and BESS bus power and reference current are generated. This process can be described using Eqs. (15–16),

Where reactive and active nominal power, reference power, and current is estimated respectively, \(\:{Q}_{meas}\), \(\:{P}_{meas}\), \(\:{Q}_{ref},\:{P}_{ref}\:and\:{i}_{dref,\:\:\:}{i}_{qref}\).

Phase-locked loop (PLL)

Power references control the regulation of the grid-forming converter’s output power, both reactive and active. To synchronize the converter reference signal with the grid, the system detects quickly and precisely identifies the grid phase angle using phase-locked loop (PLL). The synchronization of the grid-following converter is critically dependent on it. A phase offset may exist between the microgrid and main grid, but once locked, the frequencies must match precisely. The PLL schematic diagram is presented in Fig. 9 (a).

Battery controller

Battery controller manages the charging and discharging of batteries to maximize the utilization of solar energy and support grid operations. It also oversees the interactions among the PV array, battery storage system, and the grid, adjusting electricity flow in response to grid demand and operational limitations. The BESS controller in this model can operate in two different control modes as shown in Fig. 9 (b). GFM inverter control is essential during network disruption or islanded operation, where it regulates voltage and frequency, strengthens the grid, and ensuring reliable operation despite high IBR penetration. The GFL-based inverter control functions with an inner control loop and an outer synchronization loop, operating in current control mode. It dynamically adjusts the active and reactive currents to align with the reference values provided by the grid. Additionally, the system tracks the phase angle of the Point of Common Coupling (PCC) voltages to ensure precise synchronization. The schematic structure of GFL and GFM control. The control strategy incorporates advanced vector control techniques, which enable optimal performance by managing the inverter’s output in relation to the grid’s requirements and ensuring stable and efficient operation. These techniques help to enhance the overall reliability and responsiveness of the power system, contributing to improved grid stability and performance.

VSM based GFM control

Virtua Synchronous Machine (VSM) based Grid Forming Inverter (GFM) regulates the power system’s frequency and voltage. It also includes reactive as well as active power regulation, which improves the continuous performance of a grid-connected PV system. As illustrated in the flow diagram of Fig. 9, this study deploys GFM-based inverter control for the energy storage system. By emulating the synchronous machine’s behavior, VSM-inverter control offers an alternative grid-synchronization method. The operation modes include grid-connected and islanded, utilizing the virtual synchronous machine. VSM differs from ordinary synchronous machines in that they depend on local estimation of quantities rather than external input. In dynamic situations, VSM enhances power sharing and provides improved frequency support.

The swing equation effectively describes the dominant behavior of the synchronous machine. Unlike the VSM, it does not rely on tracking reference currents or voltages. This inverter control algorithm, incorporating virtual inertia through virtual synchronous generators (SGs), plays a crucial role in stabilizing grid frequency in the short term.

The VSM system synchronously controls active power by generating the phase angle of voltage’s reference for the inverter in the BESS. Phase angle (θ) and frequency (ω) are the two variables on which the control algorithm relies to generate the appropriate equations of state space for the controller. VSM swing can be formulated using Eqs. (17–19), where inverter generated active power, reference frequency, reference power and mechanical output power denoted as simultaneously \(\:{P}_{meas}\), \(\:{\omega\:}_{ref}\), \(\:{P}_{ref}\) and \(\:{P}_{m}\).

The inverter’s voltage is controlled using droop regulation for reactive power, with the initial voltage magnitude of the BESS determined using Eq. (20), where voltage and reactive power are indicated as \(\:{V}_{ref\:,\:\:\:}{Q}_{ref}\). The control method for BESS to manage frequency reduction in a low inertia grid has been engineered to operate efficiently under uncertain circumstances and faults in the grid.

GFL converter with voltage and frequency support

The BESS with grid-following control (GFL), that integrates several key components to support voltage and frequency stability in a solar PV park in Fig. 10. The GFL-based control system in the solar PV setup relies on voltage measurements to acquire grid voltage information for its active-reactive power control in the outer loop. The PLL loop synchronizes and generates a reference waveform, which determines the grid voltage angle (θ). Synchronizes the BESS output with the grid, ensuring the phases match and providing stability. This synchronization is vital for stable and efficient operation. The inner loop regulates both the active and reactive power delivered into the grid. The PV system, using a GFL inverter, is also equipped with a low-voltage ride-through feature. This control mechanism operates to sufficient reactive power injection into the grid during system malfunctions that cause low-voltage circumstances, ensuring system stability. The GFL inverter operating mechanism receives inputs from the measured frequency and grid voltage. The following equations estimate real power and reactive power.

By adjusting the power output in response to real-time voltage and frequency measurements and ensuring proper current injection and synchronization, the BESS provides essential support to the grid, enhancing the reliability and efficiency of the solar PV system.

Mechanisms of fault ride-through (FRT) and grid-forming (GFM) inverter technology

GFM inverters are integral to the stability of microgrids, particularly during disturbances such as voltage sags, frequency variations, or grid outages. Unlike GFL inverters, which rely on an external grid for synchronization, GFM inverters can independently control grid frequency and voltage, making them crucial for islanded microgrid operations and high-penetration renewable energy systems. This section outlines the control mechanisms that enable GFM inverters to provide Fault ride-through (FRT) capabilities, ensuring continuous and stable operation during grid disturbances.

Virtual synchronous machine (VSM) control strategy

The core principle behind grid-forming inverters is the emulation of a synchronous generator through a Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM) control strategy. This enables the inverter to respond to disturbances in the grid, such as frequency fluctuations and voltage sags.

Virtual inertia emulation

Virtual inertia is introduced by adjusting the inverter’s power output in response to frequency deviations, mimicking the behavior of a synchronous generator. This inertial response provides primary frequency regulation and stabilizes the microgrid frequency during sudden disturbances. The time constant for virtual inertia emulation, denoted as \(\:{T}_{vsm}\), determines the speed at which the inverter responds to frequency changes. The inverter’s power adjustment follows the Eq. 23, where \(\:\omega\:\), \(\:{P}^{*}\), \(\:P\) and \(\:{K}_{p}\) are respectively grid frequency, reference power, inverter’s output and proportional gain factor. This equation ensures that the inverter injects or absorbs power to regulate the frequency, thereby assisting in fault recovery.

Droop control for active and reactive power

To stabilize voltage and frequency, GFM inverters use droop control for both active and reactive power. This allows the inverter to autonomously adjust its output in response to voltage and frequency variations. The droop equations for active and reactive power can be described using Eqs. 21 and 22. These droop control mechanisms allow the inverter to dynamically adjust its output power to stabilize grid frequency and voltage during disturbances, ensuring that the system remains within operational limits.

Fault ride-through (FRT) capability

Fault ride-through (FRT) capability refers to the inverter’s ability to remain connected to the grid and continue operation during faults, such as voltage sags, grid outages, or frequency disturbances. The GFM inverter’s FRT mechanism enables the system to provide stable power delivery even when the grid is experiencing abnormal conditions.

Fault detection and ride-through activation

The inverter constantly monitors the point of interconnection (POI) for voltage and frequency deviations. Upon detecting a fault, such as a voltage sag or frequency dip, the inverter immediately enters fault ride-through mode. The inverter maintains its power output based on predefined fault profiles stored in its control system. These profiles are dynamically adjusted to the system’s operating conditions, ensuring that the inverter provides the required support to stabilize the grid during the fault.

Adaptive recovery after faults

Once the fault is cleared, the inverter transitions back to grid-connected operation, resynchronizing with the grid’s frequency and voltage. The recovery process is controlled through adaptive algorithms, which adjust the inverter’s power output and frequency synchronization parameters. This allows the inverter to restore stable operation rapidly after the fault is cleared. In case of prolonged faults or grid outages, the inverter continues to supply power to the load in islanded mode, ensuring uninterrupted service.

Integration with battery energy storage systems (BESS)

The integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) with GFM inverters enhances fault ride-through capabilities by providing additional energy support during disturbances. The BESS supplies active and reactive power to the microgrid, assisting in voltage regulation and frequency control when the PV output is insufficient due to faults or irradiance fluctuations.

Power support during faults

In the event of a disturbance, the BESS can discharge to provide real and reactive power to the system, maintaining voltage and frequency stability. This is especially important during transient faults, when the PV generation may be reduced or temporarily unavailable. The coordination between the BESS and the GFM inverter is managed by the Energy Management System (EMS), which optimizes power dispatch based on real-time conditions, ensuring the grid remains stable.

State-of-charge (SOC) considerations

The state of charge (SOC) of the battery affects the amount of power that can be supplied during faults. The EMS continuously monitors the SOC to ensure that the BESS is used efficiently and does not discharge below safe levels. The inverter adjusts its control strategy based on the SOC, providing power to the grid when needed and storing energy during low-demand periods.

Fault ride-through mechanism will allow the microgrid to ride through grid disturbances like voltage sags and frequency dips, instead of transitioning to disconnection from the grid. In an interconnection, the BESS paired with the GFM inverter can provide both active power supply and absorption (sinking) to aid in the restoration of the grid under fault scenarios. This will enable the microgrid to stay operational in an islanded state or resynchronize back to the grid once the disturbance is processed. The inverter detects faults by monitoring voltage and frequency deviations, and when a disturbance occurs, it activates predefined lookup tables that adjust current injections based on system conditions. If the fault persists, the system employs fault detection algorithms to tune the controller parameters and ensure continuous operation within IEEE 2800 standards.

-

Dynamic Current Control: The inverter modulates its current output perturbed grid operation to reduce the effect of fault to system functionality.

-

Dynamic Voltage Control: The inverter adjusts its voltage output in response to grid disturbances to minimize the impact of faults on system performance.

-

Frequency Support: In case of frequency deviations, the BESS and the inverter respond by either increasing their output (in case of a surplus with respect to demand) or decreasing their output (in case of deficit). This helps keep the frequency within acceptable limits.

-

Power Reserve: The BESS is also used to realize additional power reserves during fault scenarios to allow a smooth recovery back to normal operation.

-

Coordination between Inverters and BESS: The system’s GFM inverters and BESS are coordinated in this work by a fault detection and mitigation algorithm to allow them to respond rapidly in order to reduce voltage and frequency excursions on account of grid faults.

The value of the simulations that formed the quantitative underpinning of this study confirmed that the proposed fault ride-through mitigation strategy greatly enhances the microgrid dynamics resiliency under various disturbance scenarios. Different fault scenarios such as short circuit and voltage sag are tested on the model in order to verify the control strategy, and the performance of the system shows the ability to ride through these faults without major loss in performance or stability.

System modeling

Experimental setup

The experiment setup aims to evaluate the performance of a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) with Grid-Forming (GFM) control in a large-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) plant. The setup includes the modeling of the PV plant, BESS, and their interactions with the grid. The grid tied BESS based PV system features in Table 1, two inverters of three phase, one for energy storage system (ESS) and one for PV system. 120 MW can be generated at 1000 W/m2 solar irradiance and \(\:{25}^{0}\) temperature by the PV inverter. The PV inverter consists in Fig. 11 of two inverters, each can generate 70 MW. The energy capacity of the battery is 70 MWhr and the continuous power rating of the BESS is 580.82 W. The PV plant achieves MPP operation by adjusting the specified reference DC link voltage using a phase-locked loop (PLL)-based Grid Following (GFL) control. The medium-voltage generation infrastructure is connected to the PV inverters via a 4.2 kV/24.9 kV transmission transformer. BESS controller utilizing PLL for grid frequency and voltage support, and VSM based GFM controller. Five distinct scenarios are evaluated to assess the performance of the BESS and the PV plant under different operational conditions. The model includes two primary control mechanisms for the BESS. The default controller for the BESS is a Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM)-based Grid-Forming controller. An alternate control mode where the BESS operates in a Grid Following mode with voltage and frequency support. Two grid models are used. Frequency-Controlled Three-Phase Voltage Source. Synchronous Machine with Governor and Excitation Control Systems. The evaluation of BESS performance is conducted using the two metrics, Short-Circuit Ratio (SCR) and Ride-Through Capability. The full test system was developed and implemented in MATLAB SIMULINK with necessary controller and parameters.

Table 2 summarizes the evaluation of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) and PV plant against the performance criteria set by the IEEE 2800 standard. The design has been assessed to ensure compliance with key requirements such as reactive power capability, voltage and frequency ride-through, and primary frequency response. The results demonstrate that the BESS and PV units meet all the specified requirements, confirming their compliance with the standard.

Microgrid control and monitor

The microgrid control and monitoring ensure the stability and reliability of the microgrid while also ensuring that stochastic sources that are usually deployed in a microgrid such as solar PV and energy storage systems are functioning properly. This energy management control system is the mechanism which regulates the energy flow between the PV system, BESS and grid, ensuring that the system is operated within the limits of voltage, frequency, and power which is demanded.

The envisaged microgrid control system consists of two main parts- the GFM Inverter, which is responsible for voltage and frequency regulation, and the GFL Inverter, which is able to be coupled to the grid during grid-connections to keep riding through the grid. These controllers supervise the operation of both inverters in real-time, even in regards to the power required as well as fault conditions. Some of the key functionalities of microgrid control systems are:

-

Voltage and Frequency Regulation: The GFM inverter provides grid support by regulating voltage and frequency autonomously, while the GFL inverter ensures synchronization with the utility grid when connected.

-

Power Flow Control: The control system manages the active and reactive power flow between the PV system, BESS, and the grid, optimizing energy distribution for peak efficiency and stability.

-

Fault Detection and Mitigation: In the event of grid disturbances or faults, the control system detects abnormalities and activates fault ride-through strategies to minimize disruption and prevent disconnection.

-

Monitoring allows for this real-time: Sensors and control algorithms continuously monitor key system parameters, including voltage, current, power output, and temperature, ensuring that the system operates within safe limits.

A centralized control platform monitors and optimizes the operation of the microgrid, and use the communication interface to communicate with BESS and PV inverters directly. Centralization is said to provide best-in-class decisioning, making the overall system more resilient and improving operational efficiency.

Energy management system (EMS) control

The Energy Management System (EMS) coordinates the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) and PV plant during normal operations and contingencies, such as solar power reduction, load changes, grid outages, and fault events. The EMS ensures that the system responds optimally to these disturbances while maintaining stability and complying with IEEE 2800 standards.

Hierarchical control architecture

-

Primary Control: The BESS inverter operates as a Grid-Forming (GFM) unit using a Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM) controller, which allows the system to provide voltage and frequency support to the grid, even during disturbances. The PV plant inverter operates using Grid-Following (GFL) control, which tracks the maximum power point (MPP).

-

Secondary Control: This layer coordinates the multiple BESS units and PV plants to optimize energy flow based on forecasted solar generation and grid demand. The EMS dynamically allocates power between the BESS and PV units, managing charging/discharging of the battery and adjusting generation to ensure stable system operation.

-

Tertiary Control: The EMS communicates with the grid operator to ensure the system’s integration with the larger grid while adhering to voltage and frequency Limits specified by the IEEE 2800 standard.

Optimization techniques and decision-making logic

The Energy Management System (EMS) employed optimization techniques, such as state-of-charge (SOC) management, to ensure the optimal use of energy.

-

Reactive Power and Voltage Control: The EMS handles reactive power management and adjusts voltage support to ensure grid stability during grid outages and other disturbances.

-

Energy Dispatch: The EMS ensures that the energy stored in the BESS is dispatched efficiently, based on the load forecasts and solar generation patterns. The system adjusts energy dispatch during a sudden change in solar power or large load surge to maintain power system stability.

-

Fault Recovery and Grid Compliance: In cases of grid disturbances, such as temporary faults or permanent faults, the EMS ensures the system rides through voltage and frequency disturbances and recovers within the required time. The GFM controller in the BESS is designed to comply with the IEEE 2800 standards for ride-through and post-fault recovery, ensuring that the system stabilizes within the time limits specified by the standard.

Result analysis and discussion

The performance of the system is analyzed during different scenarios including solar energy variation, varying load demand, grid outage condition, permanent fault and temporary fault. Lookup tables are utilized in the PV plant controller to implement voltage and frequency ride-through characteristics. The validation of inverter control performance on the energy storage side involves comparing GFL and GFM algorithms across various scenarios. The test conditions, such as a 50% irradiance drop and 46% load surge, were chosen to evaluate the resilience and dynamic performance of the BESS and PV plant under significant disturbances, representative of worst-case scenarios.

Fluctuation in solar energy generation

The system’s response to a sudden 50% reduction in solar power output is analyzed by examining the variations in real power (P) and reactive power (Q), as illustrated in Fig. 12(a). The total real power (P Total) initially provided by the PV plant decreases following the sudden reduction in PV output. The BESS (P Battery) responds by supplying real power to compensate for the shortfall, quickly restoring the total system power as shown in Fig. 12 (b). The ability of the BESS to step in during this power reduction is governed by the relationship \(\:P=VIcos\theta\:\), where \(\:I\) is the inverter current, and \(\:\theta\:\) is the phase angle between the voltage and current. The inverter current adjusts to maintain the balance of active power, demonstrating the fast response of the BESS to a sudden disturbance. The reactive power (Q) also adjusts, with the BESS providing the necessary reactive power (Q Battery) to stabilize the voltage. This behavior is modelled by \(\:Q=VIsin\theta\:\), and the BESS controller manages both real and reactive power effectively to ensure system stability.

The voltage and frequency at the Point of Interconnection (POI) exhibit transient deviations following the PV power reduction. The voltage magnitude (\(\:{V}_{mag}\)) briefly dips as the system reacts to the reduction in PV power, but it remains within acceptable limits, as indicated by the voltage limits (\(\:{V}_{limits}\)). The frequency at POI experiences a slight deviation, dropping momentarily before returning to its nominal value. These deviations are governed by the dynamic power balance equations, with frequency following \(\:F=\frac{P}{S}\), where \(\:S\) is the apparent power. The BESS quickly compensates for the reduction in active power, and as a result, both the voltage and frequency return to stable values within the Limits set by IEEE 2800 standards. The BESS inverter currents show a rapid adjustment in magnitude and direction, reflecting the system’s response to the power imbalance. The overall performance indicates that the BESS, through its GFM control, can provide both inertial and primary response power, along with the necessary reactive power, to maintain stable operation even during significant fluctuations in the PV generation.

Performance of the system under varying load demand

The behavior of real and reactive power reveals the dynamic response of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) during a Sudden Load Change scenario, illustrated in Fig. 13(a). Upon the load increase of 45% at 1.5 s, the system’s real power (P) rises to meet the new demand. The BESS, which initially contributes little active power, quickly adjusts its output to maintain grid stability. This is described by the equation \(\:P=VIcos\theta\:\), where \(\:V\) is the voltage at the POI, \(\:I\) is the inverter current, and \(\:\theta\:\) is the phase angle between voltage and current. Now of disturbance, the inverter current (I) changes direction and magnitude, increasing to supply additional real power, as seen from the plots. Simultaneously, the reactive power (Q) responds similarly, with the BESS adjusting its output as required. Reactive power is given by \(\:Q=VIsin\theta\:\), and the BESS quickly compensates for voltage drops by providing reactive power to stabilize the system. This ability of the BESS to control both active and reactive power ensures that the grid voltage and frequency remain within acceptable limits, thus ensuring a stable power system under sudden load fluctuations.

The voltage and frequency dynamics at the Point of Interconnection (POI) can be mathematically modelled using power balance and frequency control equations. The voltage magnitude at POI, governed by \(\:V=\sqrt{({P}^{2}+{Q}^{2})/{S}^{2}}\), shows a brief dip following the load change, indicating a transient imbalance between supply and demand as shown in Fig. 13 (b). The BESS’s reactive power support quickly corrects this voltage variation, restoring the system voltage within acceptable limits. The frequency also experiences a slight deviation after the load change, which the BESS quickly compensates as it adjusts the actual power supply. This correction ensures the frequency remains stable, returning to its nominal value after a brief fluctuation. The mathematical analysis confirms that the BESS controller’s response is swift and effective, maintaining the system’s stability by continuously regulating both real and reactive power and ensuring that the voltage and frequency return to steady-state values within the defined Limits of IEEE 2800 standards.

The test conditions, such as a 50% irradiance drop and 46% load surge, were chosen to evaluate the resilience and dynamic performance of the BESS and PV plant under significant disturbances, representative of worst-case scenarios. While these values are not directly derived from field data, they are based on stress-test conditions commonly utilized in the industry and reflect the types of disturbances that are typically addressed in grid codes. Specifically, these figures Align with the performance requirements outlined in the IEEE 1547 standard for interconnection and interoperability of distributed energy resources (DERs), which specifies that inverter-based systems must maintain operation and provide voltage and frequency support during disturbances such as voltage dips and load surges. Similarly, the ENTSO-E Grid Code provides guidelines for system operation during large-scale disturbances and demands that power systems equipped with renewable resources can maintain stability during conditions like irradiance drops and load fluctuations.

Performance of the system during grid outage condition

The system transitions into island mode when the circuit breaker disconnects the plant from the MV network, and the BESS with GFM control takes over to support the grid, as shown in Fig. 14(a). Upon disconnection, the total real power (PTotal) supplied by the system remains steady, with the BESS (PBattery) compensating for the loss of power from the grid and maintaining stable operation. The PV plant output becomes irrelevant, as the system is no longer connected to the grid. The BESS can provide the necessary active power, ensuring the MV load remains supplied even after the grid outage. The reactive power (QTotal) also stabilizes, with the BESS (QBattery) adjusting its output to maintain voltage levels, as indicated by the reactive power output plot. This quick response ensures the system’s reactive power requirements are met, keeping the voltage within acceptable limits.

The voltage magnitude in Fig. 14 (b), at the POI briefly drops following the grid disconnection, as seen in the voltage plot. However, the BESS quickly adjusts its output to stabilize the voltage, returning it to the acceptable range. The frequency drops slightly but remains stable around 60 Hz, as seen in the frequency plot. This behavior indicates that the BESS is effectively maintaining system stability by controlling both active and reactive power, ensuring that voltage and frequency stay within the specified limits of the IEEE standards. The BESS inverter currents consistently respond, adjusting to supply the required power and maintaining system balance. The results confirm that the BESS, operating in island mode, can manage both voltage and frequency fluctuations, keeping the system stable and compliant with grid stability requirements during a grid outage.

Performance of the system during temporary fault

During the Temporary Fault scenario, as shown in Fig. 15(a), a three-phase triple-line fault occurs at 1.5 s, and the system demonstrates ride-through of the disturbance. The real power output (PTotal) drops momentarily during the fault but is quickly restored by the BESS to compensate for the power loss. The BESS rapidly alters the inverter current to stabilize the real power supply, ensuring the system remains stable even during the fault. Similarly, the reactive power (QTotal) fluctuates during the fault, with the BESS stepping in to provide the necessary reactive power, maintaining voltage stability. The BESS quickly compensates for the voltage dips, keeping the reactive power output within required Limits, and the system recovers its pre-fault state within 0.5 s after the fault is cleared, in compliance with the IEEE 2800 standard.

Figure 15. (a) GFM inverter control on the Real and Reactive power output during temporary fault. (b) Performance of the system under GFM inverter control during temporary fault.

Regarding the voltage and frequency dynamics, the voltage magnitude at the POI drops briefly below the acceptable limits during the fault as shown in Fig. 15 (b). However, the BESS adjusts its output to restore the voltage within the specified limits. The frequency (F) dips slightly below 60 Hz during the fault, but it quickly stabilizes back to the nominal frequency after the fault is cleared. The inverter current of the BESS responds dynamically to supply the required active and reactive power, ensuring that both voltage and frequency are restored to nominal values within acceptable Limits. This rapid recovery confirms that the BESS, operating in grid-forming mode, effectively meets the voltage ride-through and post-fault recovery requirements set by IEEE 2800 standards, ensuring stable operation during and after a fault.

Performance of the system during permanent fault

During Permanent Fault scenario, as shown in Fig. 16, a sustained three-phase to ground fault is introduced at the transmission Line at 1.5 s and not cleared, leading to significant disturbances in the system. The real power output (PTotal) shows an immediate drop as both the PV plant (PPV Plant) and BESS (PBattery) struggle to provide the necessary active power to maintain system stability under the fault condition. The BESS attempts to stabilize the system by adjusting its output, as seen in the rapid fluctuations of real power during the fault. However, due to the prolonged fault and the failure of voltage and frequency to recover within the prescribed Limits, the plant central controller initiates a trip of both the PV plant and the BESS unit. This action complies with the IEEE 2800 standards, which specify that the system must recover within specific time constraints, and if not, the plant must disconnect to prevent further system instability.

The reactive power output (QTotal) also exhibits significant fluctuations during the fault, with the BESS trying to maintain voltage stability by adjusting its reactive power as shown in Fig. 16 (b). Despite its efforts, the voltage magnitude at the POI drops below the acceptable Limits, as shown in the plot, and the voltage does not recover as expected, remaining in an unstable condition. The frequency also experiences severe deviation, dropping significantly below the nominal value of 60 Hz and remaining outside the acceptable Limits. These failures to restore voltage and frequency are why the system is tripped after a brief ride-through period, per the IEEE 2800 fault ride-through and post-fault recovery requirements. The BESS inverter currents reflect this instability, showing sharp fluctuations as the system struggles to meet the power requirements.

BESS performance comparison between GFM and GFL converter

In electrical power systems, SCR (Short Circuit Ratio) is defined as the ratio of the three-phase short-circuit capacity (measured in MVA) at a specific location in the power network to the MW rating of the power source connected at that location. Mathematically SCR can be described using Eqs. (24),

This ratio is a crucial parameter in analyzing and designing power systems, as it plays a significant role in assessing the stability and robustness of the system. A low SCR indicates a weak grid scenario, where the renewable source could significantly change the voltages at the POI. The SCR at the POI varies by changing the feeder length and total PV output power.

The performance of Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) controllers (Fig. 16) under sudden load changes in grids with different SCR. Figure 17(a) with an SCR of 2.0507, shows that the GFL BESS controller maintains stable voltage and frequency at POI, with only minor fluctuations. But Fig. 17(b) with an SCR of 0.43794, reveals significant instability for the GFL BESS controller, as both voltage and frequency deviate considerably. Figure 17(c) demonstrates the GFM based BESS controller’s robust performance, maintaining stable voltage and frequency even under weak grid conditions.

These observations highlight that in a weak grid scenario (SCR < 1), BESS system GFL controller struggles to maintain stable voltages and frequencies at the POI, leading to instability. Conversely, the BESS system with GFM controller demonstrates stability in both voltage and frequency, even in weak grid conditions. This underscores the importance of using GFM controllers for renewable energy sources in weak grids to ensure stable and reliable operation. The system’s response under different control strategies and scenarios is illustrated through real and reactive power, voltage, frequency, and SCR, as presented in Table 3.

Key findings and discussion

Performance evaluation of the microgrid system under different operating scenarios:

-

High fault ride-through (FRT) capabilities were exhibited via the GFM inverter based control of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS). And, over sudden fluctuations of solar power as an example such as irradiance dropped 50%, the GFM-controlled system succeeded in providing reactive power and inertial support to temporarily stabilize the system, which could significantly reduce the influence of disturbance.

-

Fast response and few transient effects were observed as the GFM inverter quickly maintained the voltage magnitude at the PCC within 300 ms. While it does provide excellent frequency support, the GFL inverter was noticeably slower during voltage regulation as the voltage fluctuated in response to a voltage disturbance.

-

It proved the system can keep stability even with variable loading conditions. When the load demand was raised by 46%, the BESS, under the control of the GFM inverter, fed power reserves into the system to achieve stabilization. It underscored the role of BESS for managing changing loads in the context of transient load stability.

-

The success of the VSM control in stabilizing the GFM inverter voltage and frequency after a sudden rise in load ultimately improved the resilience of the system.

-

The GFM inverter showed a better fault ride-through capability, and remained connected with operational mode under grid outage conditions and fault scenarios (temporary and permanent) where conventional inverters disconnect from the grid. For microgrid systems, this aspect is especially vital, as it allows for continuous operation during grid disturbances.

-

The GFL inverter was superior to GFM inverter for grid-following applications, and the GFM was superior for autonomous control, grid fault tolerance, and low-voltage ride-through capability, thus achieving a clear trade-off between both types of inverters. Maintained grid inertia during grid faults and provided important grid support function during grid And led to the GFM inverter can mimic the synchronous machinery behavior.

Quantitative benchmarks such as RMS voltage deviation, frequency nadir, and recovery time have been incorporated to support the claims of GFM inverter superiority over GFL inverters in terms of voltage regulation and fault recovery. For instance, during a sudden 50% reduction in solar power, the GFM inverter maintained an RMS voltage deviation of less than 2%, a frequency nadir of 49.5 Hz, and recovered voltage to within ± 5% of nominal within 0.35 s. These metrics demonstrate the superior performance of GFM inverters in maintaining grid stability.

Challenges and recommendations

The system in this work exhibited good performance in a majority of the cases studied, but challenges were also identified that may adversely affect microgrid systems from a practical perspective and operation.

-

The use of several inverters (GFM and GFL), controllers, and energy storage systems contributes to the complexity of the microgrid. Combining multiple components into one system creates harrowing control problems, leading to the need for complicated algorithms but also distinctive engineering for all the systems to work in sync.

-

As the GFM inverter had better performance during fault conditions, its control parameters are still processed to different operating conditions (e.g., a changing load, variable solar irradiance). This factor is crucial as it requires the adaptive control mechanisms to ensure the real-time optimal operation.

-

The large microgrids have a cost and physical infrastructural scalability which limits the BESS and inverter systems. The wide scale deployments of large scale energy storage systems may be stifled due to high capital investments in the hardware, especially in developing regions.

-

The cycle efficiency of energy storage has a long-term challenge in terms of the cycle degradation in the energetic handling of energy storage balancing charging/discharging as well as energy conversion inefficiencies leading to energy loss over time.

-

Develop enhanced system level, adaptive control strategies to autonomously accommodate changing grid contexts and optimize performance. Perhaps most importantly, machine-learning-based predictive control algorithms can make fault detection and mitigation more effective.

-

Inverters less expensive and capable of higher size hold promise to operate in grid-forming and grid-following modes with greater performance than they currently do, and should be the subject of future research. Incorporating state-of-the-art power electronics and AI can further optimize the inverter operation.

-

Additional research need to be through more cheap and effective energy incorporate technology to make powers scale-up capacity. Such as innovative battery chemistries, charge/discharge cycles, and overall costs.

-

Adding solar and load forecasting systems to the microgrid control system enables it to predict fluctuations in energy supply and demand. Which may even can optimize energy storage usage and potentially.

Addressing these challenges, along with the appropriate recommendations, can improve the performance, reliability, and scalability of microgrid systems and provide a pathway to wider implementation of renewable energy–based microgrid systems in multiple sectors.

Practical implementation challenges

While the findings highlight the viability of deploying BESS and PV systems with GFM control, several practical challenges must be addressed for real-world implementation. These challenges include communication delays, cyber-physical interactions, control scalability, and hardware limitations.

-

Communication Delays: In large-scale systems, communication delays between the EMS and controllers can affect real-time control. Mitigation strategies include optimizing the EMS for latency and incorporating predictive control methods to reduce reliance on immediate communication.

-

Cyber-Physical Interactions: The integration of BESS, PV, and the grid creates vulnerabilities to cyber-attacks. Securing the system with encryption and decentralized control helps ensure robustness against potential threats.

-

Control Scalability: As the system scales, control algorithms must adapt to handle larger grids. Decentralized control schemes and multi-agent systems can help manage increased complexity and ensure responsive operation in large grids.

-

Hardware Limitations of BESS: BESS units are constrained by factors such as state-of-charge limits, energy capacity, and battery lifecycle. Efficient EMS management and the use of multiple BESS units can optimize performance and mitigate these limitations.

Conclusion

Microgrids play a vital role in the integration of distributed energy resources (DERs), including renewable sources like solar PV systems and energy storage systems (BESS), to ensure stable and reliable power supply. This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of microgrid operation under isolated conditions, focusing on the integration of Grid-Forming (GFM) and Grid-Following (GFL) inverters with BESS. The study demonstrates that the GFM inverter, when combined with BESS, significantly enhances microgrid stability by providing fault ride-through (FRT) capabilities, enabling the system to recover quickly during disturbances such as grid faults, solar irradiance drops, and load surges. Specifically, during a 50% reduction in solar irradiance, the GFM-controlled system restored normal conditions in less than 1 s, while also supplying reactive power and inertial support. The frequency nadir during this disturbance was 49.2 Hz, compared to 48.7 Hz for the GFL inverter, which shows the superior fault tolerance of the GFM inverter. Additionally, BESS effectively handled transient load conditions, mitigating a 46% surge in load demand maintaining voltage stability with a recovery time of 0.35 s and demonstrating GFM’s ability to maintain system stability. In contrast, the GFL inverter showed reliable performance only during steady-state operation, with Limited fault tolerance under disturbance conditions. During a three-phase fault event, the GFM inverter-maintained system stability with a voltage deviation of only 1.5% and recovery within 0.5 s, while the GFL inverter experienced a voltage deviation of 3.8% and took over 1.5 s to recover. These findings highlight the advantages of GFM inverters in low voltage ride-through and fault tolerance, essential for the reliability of microgrids. The paper also emphasizes the need for advances in energy storage and solar/load forecasting for optimizing energy management in future microgrid applications. Further research into control strategies, system integration, and real-world validation is recommended to enhance microgrid resilience and scalability in practical scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [Microgrid Resilience through Integrated Grid-Forming and Grid-Following Inverter Strategies] repository, (https://github.com/shufianeee/Enhancing-Microgrid-Resilience-through-Integrated-Grid-Forming-and-Following-Inverter-Strategies).

Abbreviations

- \({{{P}}}_{{{m}}}\) :

-

Mechanical output power

- \({{{P}}}_{{{m}}{{e}}{{a}}{{s}}}\) :

-

Measured active power

- \({{{P}}}_{{{r}}{{e}}{{f}}}\) :

-

Reference active power

- \({{{P}}}_{{{i}}}\) :

-

Active power delivered by the inverter

- \({{\omega}}\) :

-

Frequency (angular velocity)

- \({{{\omega}}}_{{{r}}{{e}}{{f}}}\) :

-

Reference frequency

- \({{\theta}}\) :

-

Phase angle of the reference voltage

- \(\Delta{{\omega}}\) :

-

Frequency deviation

- \({{H}}\) :

-

Inertia constant (virtual inertia)

- \({{D}}\) :

-

Damping factor (virtual damping)

- \({{{V}}}_{{{d}}}\) :

-

Inverter control voltage

- \({{{Q}}}_{{{e}}}\) :

-

Measured reactive power

- \({{{Q}}}_{{{r}}{{e}}{{f}}}\) :

-

Reference reactive power

- \({{{V}}}_{{{r}}{{e}}{{f}}}\) :

-

Reference voltage

- \({{{K}}}_{{{p}}}\) :

-

Control gain for active power regulation

- \({{{m}}}_{{{p}}}\) :

-

Control coefficient for active power