Abstract

Perfluoropolyethers (PFPEs) have attracted much attention due to their exceptional chemical stability, thermal resistance, and wide application in high-performance industries such as aerospace, semiconductors, and automotive engineering. One of the most important properties of PFPEs as lubricants is their viscosity. However, experimental determination of viscosity is time-consuming and expensive. In this study, four intelligent models, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and Adaptive Boost Support Vector Regression (AdaBoost-SVR), were used to predict the viscosity of perfluoropolyethers based on parameters such as temperature, density, and average polymer chain length. Statistical error analysis showed that the GPR model had higher accuracy than other models, achieving a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.4535 and a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.999. To evaluate the innovation and effectiveness, we compared the GPR model with the predictions obtained from the traditional Waterton and Vogel-Fulcher-Thamman (VFT) correlations. Furthermore, the GPR model not only provided high accuracy, but also successfully captured the underlying physicochemical trends. To further evaluate the performance of the GPR model, the leverage technique was utilized, which demonstrated that 98.33% of the data points fell within the valid range, emphasizing the robustness and reliability of the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For many years, achieving water and oil repellency has been a primary objective in the development of functional polymer-based materials. Traditionally, this goal has been met through the widespread use of long-chain perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs, CnF2n+1, where n ≥ 7), which have been extensively incorporated into products such as textiles, polymer coatings, and surfactants across a broad range of industries, up until more recent times1,2,3,4 .However, the environmental persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxic effects of PFASs on humans, wildlife, and ecosystems have become increasingly evident, leading to their gradual elimination from industrial use and commercial applications. Perfluoropolyethers (PFPEs), which feature backbone structures composed of –CF₂–, –CF₂–CF₂–, and –CF(CF₃)–CF₂– segments interspersed with oxygen atoms, are currently regarded as promising and potentially safer alternatives to traditional PFASs1,5,6. Since the 1960s, PFPEs have gained widespread international attention due to their remarkable properties, including exceptional resistance to heat, oxidation, and corrosion, stability under radiation, low volatility, superior chemical inertness, and reliable lubricating performance7,8,9. Thanks to its exceptional properties, PFPE stands out as a dependable lubricant for extreme environments. Moreover, it has found widespread application across multiple engineering disciplines and industries as a stable lubricant for computer hard drives in electronics, as a working fluid in vacuum pumps within the chemical sector, in uranium enrichment processes in the nuclear industry, and the mechanics of aerospace systems used in aviation and space exploration10,11,12,13,14,15. PFPE demonstrates outstanding thermal stability and exceptional resistance to corrosion, making it particularly well-suited for use in high-temperature environments16,17. However, its exceptionally low surface tension poses a significant challenge in forming a robust oil film at frictional interfaces, leading to less effective lubrication performance18.

The inclusion of fluorine-based materials in batteries helps create a protective layer at the metal-electrolyte interface, which in turn improves the overall stability of the battery19,20,21,22,23,24. Fluorine-containing polymers are known for their exceptional properties, including high thermal stability, chemical resilience, and biocompatibility25,26. For instance, PFPE exhibits remarkable attributes such as resistance to high temperatures, oxidation, low volatility, and non-flammability, even when exposed to oxygen at temperatures ranging from 270 to 300 °C27. Recent studies indicate that PFPE-based materials are increasingly being utilized as electrolytes and solid electrolyte phases in metal-ion batteries, selective membranes for metal-air batteries, and microporous layers for gas diffusion electrodes in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. In addition to these benefits, PFPE’s low volatility, excellent temperature-viscosity characteristics, non-flammability, and superior thermal and chemical stability have made it widely used as a lubricant in various industries, including high-vacuum pump oils, hard disk drives, rigid magnetic media, and space mechanical components9,28,29,30.

Bell and Howell31 provided an overview of the composition and physical behavior of these polymers. While their characteristics have generally been assessed with a focus on engineering applications, a thorough and all-encompassing analysis remains limited. Among the key parameters for evaluating lubricants, viscosity stands out as a fundamental property. The viscosity of PFPE is a key factor that influences the performance of PFPE-based lubricants. It plays a crucial role in the lubricant’s ability to minimize friction and wear, particularly under changing temperature and pressure conditions. For example, the viscosity-temperature slope of PFPE fluids is closely linked to their carbon-to-oxygen ratio, which affects their suitability for different applications32. Accurate prediction of PFPE viscosity is essential for designing effective lubricants tailored to specific operational environments. Experimental determination of the viscosity of PFPEs is particularly challenging due to their unique physicochemical properties, including high thermal and oxidative stability, low volatility, and strong intermolecular forces, requiring specialized equipment and tightly controlled conditions to achieve accurate and reproducible results. To estimate the viscosity, researchers used empirical correlations such as the Waterton and Vogel-Fulcher-Thamman (VFT) equations to predict the viscosity. While these correlations can provide acceptable estimates within certain temperature ranges, they lack predictive power outside these ranges. To overcome these limitations, we used machine learning models. Machine learning models offer nonlinear pattern recognition capabilities to more accurately and efficiently predict the viscosity of PFPEs over a wide range of conditions. Machine learning models provide powerful predictive capabilities by learning complex, nonlinear relationships directly from data, without the need for predefined equations or simplifying assumptions. They can generalize well over a wide range of temperatures, pressures, and compositions, making them highly adaptable to diverse and complex systems. Unlike empirical correlations, which are often limited to specific conditions and require manual parameter tuning, machine learning models can process large data sets and provide more accurate and robust predictions33,34,35,36. Machine learning models offer a promising alternative by analyzing molecular structures and properties to predict viscosity efficiently. These models can process large datasets to identify patterns and relationships that may not be apparent through conventional approaches, thereby accelerating the development of PFPE lubricants with desired performance characteristics37. This study is the first to use machine learning models to predict the viscosity of perfluoropolyether. This research predicts the viscosity of Perfluoropolyether using the three main input parameters of temperature, density and average polymer chain length. In this work we predict viscosity with minimal input information over a wide range of temperatures. This study significantly advances our understanding of the rheological properties of perfluoropolyether. Perfluoropolyether viscosity is an essential parameter used in addition to electrolytes in lithium metal and lithium-ion batteries for high-performance lubricants used in the aerospace and automotive industries.

Theory and methodology

Dataset construction and description

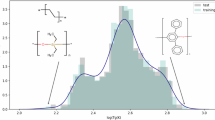

Pure viscosity data were collected for perfluoropolyether oils38. The retrieved viscosity data for perfluoropolyether oils add up to a total of 120 experimental results for dynamic viscosity. The working set includes viscosity values from 3.096 to 917.7 mPa.s at temperatures of 263.15 to 373.15 K and at constant pressure and in density from 1690.048 to 1924.38 kg.m−3 is evaluated. Table 1 presents a comprehensive statistical summary of the dataset employed in this research. It outlines essential descriptive metrics, including the minimum, maximum, average, median, and skewness values of the variables. The input parameters in this study are temperature (T), PFPE density (ρ), and average polymer chain length (n). Using these inputs, the viscosity of perfluoropolyether oils (η) is predicted. A box-and-whisker plot is a visual representation of five statistical values, namely the minimum, median, maximum, first quartile, and third quartile of a given data set. The lowest point represents the minimum, while the highest peak indicates the maximum. The box displays the range between Q1 and Q3, with a line running through the center to mark the median. Figure 1 shows a box plot of the database included in this study.

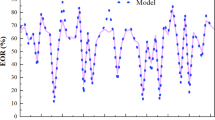

Machine learning models

Multilayer perceptron (MLP)

MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) is one of the most widely used artificial intelligence techniques, developed in the 1980s. MLP models consist of one or more input layers where the data is processed, and one or more output layers where the predictions are generated39,40. The hidden layer acts as a communication bridge between the input and output layers, utilizing various transfer functions41. In this model, layers with specific weights are connected to establish a relationship between input and output values through activation functions42,43. The activation functions used in this study are listed below:

Designing an effective MLP architecture requires careful adjustment of the hidden layer configuration, including both the number of layers and neurons per layer. In this study, these architectural choices were refined using hyperparameter tuning rather than relying solely on intuition or manual selection. The optimal setup identified consisted of two hidden layers, each comprising six nodes. A visual overview of the implemented MLP model is presented in Fig. 2. For readers interested in further theoretical background on MLP structures, detailed information can be found in the reference44.

Support vector regression (SVR)

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a supervised machine learning technique designed to predict continuous outcomes, especially when working with limited datasets45,46. Rather than fitting a model that perfectly matches all training points, SVR seeks a balance between prediction accuracy and model simplicity by creating a margin of tolerance around a decision boundary, known as the hyperplane.

The algorithm uses kernel functions such as linear, polynomial, or radial basis function (RBF) to transform input data into a higher-dimensional space, making complex relationships easier to model. Support vectors, which lie close to or outside the margin, determine the position of the hyperplane and heavily influence the final model.

Key parameters like the regularization constant \(C\) , error tolerance \(\epsilon\) , and kernel-specific values such as \(\gamma\)(for RBF) or \(\nu\) play critical roles in tuning the model’s performance. SVR handles nonlinear trends effectively and is resistant to noise and outliers. Its optimization relies on solving a quadratic programming problem, where Lagrange multipliers are used to weight influential data points47,48.

Gaussian process regression (GPR)

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a versatile supervised learning method commonly applied to regression and probabilistic classification problems. It relies on the concept of a Gaussian Process (GP), which represents a collection of random variables where any subset has a joint Gaussian distribution. The behavior of a GP is governed by its mean and covariance functions. Unlike conventional regression models that aim to find a single best-fit function, GPR operates by inferring a distribution over a range of plausible functions, enabling it to capture uncertainty and provide a probabilistic prediction for new data points49,50. In contrast to many traditional regression methods, GPR does not rely on a predefined functional form. Rather, it treats the observed data as realizations from a multivariate Gaussian distribution, where each data point corresponds to a location in the input space drawn from this distribution. The GP is formally represented by the function \(f\left(x\right)\) which defines an implicit function composed of a collection of random variables51:

here, \(K\) denotes a covariance function52. During the training of the GPR model, the kernel’s hyperparameters are tuned by maximizing the log-marginal likelihood (LML) through the chosen optimization algorithm. The optimization process always starts from the kernel’s default hyperparameter settings on the first attempt, whereas subsequent attempts initialize the hyperparameters randomly within their allowable ranges. If the hyperparameters are intended to stay fixed, the optimization step is bypassed entirely.

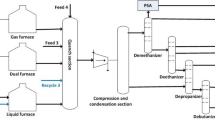

Adaptive boosting support vector regression (AdaBoost-SVR)

Freund and Shapier53 introduced the AdaBoost algorithm, a supervised learning technique widely used for classification and regression tasks52. The AdaBoost method, shown in Fig. 3, is based on the sequential implementation of weak learners on the reweighted data type. In Fig. 3, these simple models, which are known weak learners, predict slightly better than random guessing. In addition to these strong learners, some basic models provide more accurate predictions. In this study, SVR is used as a weak learner in the AdaBoost framework. Weights are adjusted based on learner performance. When difficult items are given more weight, the next learner will focus more on these challenging points54. In the present work, this method is applied to regression tasks, with SVR as weak learners responsible for predicting the results. Each AdaBoost regression follows five main steps55:

-

(1)

Starting with equal weights, each is set as \(w_{j} = \frac{1}{N},j = 1,,2,{ }3, \ldots ,N,\) where N represents the total count of learners;

-

(2)

Calculate the error for each i by feeding the training subset into \(w{l}_{i}(x)\), the weak learner. This error can be determined using the equation shown below:

$$Error_{i} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{n} w_{j} I\left( {t_{j} \ne wl_{i} \left( x \right)} \right)}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{n} w_{j} }},{ }I\left( x \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {1 if x = True} \\ {0 if x = False} \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(5) -

(3)

Determine the weight of the estimator for each i using the formula \(\beta_{i} = \log (\frac{1}{{Error_{i} }} - 1);\)

-

(4)

Update the weights calculated for each i;

-

(5)

Finally, adjust the weak learner to produce the desired output value.

Hyperparameter tuning and industrial implementation of machine learning models

In this study, the dataset was randomly partitioned into two subsets, with 80% allocated for training and 20% reserved for testing to evaluate the model’s generalization on unseen data. Before training, all input and output features were normalized using the StandardScaler function from the Scikit-learn library. This transformation standardized the variables to have zero mean and unit variance, which helps reduce the influence of differing scales and units among features. Standardization plays a key role in improving model stability, accelerating the convergence of learning algorithms, and enhancing overall predictive accuracy56.

To fine-tune the performance of the machine learning models, hyperparameter optimization was conducted by the GridSearchCV method from the Scikit-learn library. This approach systematically explored a predefined range of hyperparameter combinations using tenfold cross-validation. This method divides the dataset consisting of 120 data points into ten equal subsets, using nine for training and one for validation in each iteration, rotating through all subsets. Compared to leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), which involves training the model 120 times (once per data point), tenfold cross-validation offers a more efficient alternative with reduced computational cost, and lower variance in performance estimates. Additionally, it provides an advantage over simpler methods like a single train-test split, which can lead to biased or unstable results depending on how the data is partitioned. Unlike repeated random subsampling or holdout validation, tenfold cross-validation ensures that each data point is used exactly once for validation and multiple times for training, leading to a more reliable and consistent evaluation of model generalization. This balance of efficiency, stability, and representativeness makes it a preferred choice for moderate-sized datasets like the one used in this study.

Three evaluation metrics were utilized as scoring functions: negative mean squared error (neg_mean_squared_error), negative mean absolute error (neg_mean_absolute_error), and negative root mean squared error (neg_root_mean_squared_error). Upon comparison, the scoring criterion neg_mean_squared_error consistently yielded superior results across all models, leading to its selection for final optimization. GridSearchCV not only identified the optimal hyperparameters that minimized the selected loss function, but also ensured that each model reached its highest predictive accuracy with the lowest validation error. Detailed configurations and the corresponding best hyperparameters for each model are summarized in Table 2.

Once the models were optimized and trained using the best hyperparameter sets on the training data (X_train, y_train), the final versions were saved as .pkl files for ease of reuse. These serialized models, optimized through cross-validation, are suitable for direct application in industrial settings. By simply inputting relevant process parameters, such as temperature, density, and average polymer chain length, engineers and practitioners can quickly obtain accurate viscosity predictions without requiring an internet connection or high-performance computing infrastructure. This streamlined approach facilitates real-time decision-making and efficient deployment in practical scenarios.

Statistical error analysis

In this study, we applied GPR, SVR, AdaBoost-SVR and MLP models to predict the viscosity of perfluoropolyether oils. The reliability of the model is evaluated by measuring the error between the predicted viscosity data (ηpred) and the actual viscosity (ηexp). A set of statistical criteria is utilized to examine the performance of these models (with Eqs. 6–10)57,58.

Average percent relative error (APRE)

Average absolute percent relative error (AAPRE)

Root mean square error (RMSE)

Standard deviation (SD)

Determination coefficient (R2)

Results and discussion

Table 3 provides a detailed statistical summary of all the established models for training, testing, and the overall database. As depicted in Table 3, all the intelligent models exhibit a strong correlation between the estimated and actual experimental values, demonstrating a high level of agreement. Among these models, the GPR model outperforms the others, achieving the highest accuracy with AAPRE values of 0.073 and an R2 of 0.999. Figure 4 illustrates a comparison of the AAPRE and RMSE metrics for various machine learning algorithms, where the GPR model clearly stands out with the smallest error values. To further assess the consistency between predicted and experimental viscosity values, a Taylor diagram is employed. In this diagram, models demonstrating higher prediction accuracy are located closer to the reference point, whereas models with lower precision are situated farther from it. As presented in Fig. 5, the GPR model achieves the closest proximity to the observed data point for both the training and testing phases, underscoring its superior predictive capability over the other models.

Graphical error analysis

Alongside statistical analysis, graphical error assessment serves as a powerful tool for evaluating model performance. It is particularly beneficial for comparing multiple models. This study employed various graphical techniques to highlight the effectiveness of the developed model.

Figure 6 presents cross-plots of the AI-based models developed for viscosity estimation. The plots clearly illustrate the strong performance of all the proposed models, with the points closely clustered around the X = Y line, indicating a high level of accuracy.

The distribution of relative error versus actual viscosity measurements for each model is displayed in Fig. 7. This type of error analysis visualizes how the relative error varies with the actual output values. A model demonstrates higher accuracy when its data points are closely aligned with the y = 0 error line. As observed in Fig. 7, the GPR model aligns almost perfectly with the zero-error line, indicating minimal relative error and a strong agreement between its predictions and the experimental data.

Figure 8 illustrates the cumulative frequency distribution of the dataset based on the absolute relative error. The graph shows that the GPR model achieves a relative error under 0.8% for 90% of the data, underscoring its excellent predictive performance. As can be seen in the figure, after the GPR model, the AdaBoost-SVR, MLP, and SVR models have higher accuracy and lower error, respectively.

Using group error plots is an effective way to evaluate the performance of models in different temperature and density ranges. These plots for all models for four temperature and density ranges are presented in Fig. 9. According to this figure, the absolute relative error of the GPR model in all temperature and density ranges is lower than that of other models, which indicates the high accuracy of this model compared to other models.

Analyzing the relationship between predicted and experimental viscosity values across all datasets offers valuable insights. A stronger correlation between predicted and actual values signifies greater model accuracy. Figure 10 provides a visual representation of this relationship, emphasizing the close alignment between the experimental results and the predictions produced by the GPR model. This indicates the model’s exceptional performance and reliability in predicting PFPE viscosity.

Figure 11 compares the prediction errors of the models for the test data. It reflects the deviation between the model’s output and the actual viscosity measurements. As shown in Fig. 11, the GPR model has the lowest error distribution range from − 1.66 to 4.48. The SVR, MLP and AdaBoost-SVR models have a wider range of predicted errors, which indicates the low accuracy of these models compared to the GPR model.

Various equations have been suggested in previous studies to correlate experimental viscosity data59. In this research, alongside evaluating machine learning models, we also assessed the performance of two traditional correlation equations in comparison with the top-performing machine learning model. The first equation considered is the Vogel–Fulcher–Tammann (VFT) equation (Eq. 11)60,61,62 .

In this equation, Tr represents the reduced temperature (the ratio of the PFPE temperature in Kelvin to 273.15 K), η0 is equal to 1 mPa.s, and β1, β2, and β3 are constant coefficients specific to each PEPF. Equation 11 is a well-established formula in scientific literature for modeling the temperature-dependent viscosity of liquids, initially devised to analyze the viscosity behavior of glass-forming liquids. Another formula, introduced by Waterton63, is presented in Eq. 12.

This correlation was included due to recent findings that suggest it outperforms the VFT correlation64,65,66. After Mauro et al. rediscovered Waterton’s correlation64, it became known as the “Mauro–Yue–Ellison–Gupta–Allen (MYEGA) model of liquid viscosity” in their subsequent publications.

In Fig. 12, we present a comparison of the Average Absolute Deviation (AAD%) for the GPR model, the Waterton correlation, and the VFT correlation. The results in Fig. 12 indicate that the GPR model achieves higher accuracy than both the Waterton and VFT correlations, demonstrating its superior ability to predict the viscosity of PFPE with greater reliability.

Model trend analysis

Trend analysis is a common method for illustrating how the output varies in response to changes in input variables67. The GPR model, which is the most appropriate model developed, was utilized to predict changes in viscosity with changes in density and temperature. Figure 13 illustrates the effect of temperature on viscosity for six perfluoropolyethers. As illustrated in this figure, viscosity exhibits a decreasing trend with rising temperature, a pattern that the GPR model successfully captures. Figure 14 depicts how viscosity varies with density across six perfluoropolyether materials, revealing that viscosity increases as density rises, an effect accurately predicted by the GPR model.

Evaluating and enhancing the generalizability of the viscosity prediction model for PFPEs

Indeed, PFPEs are utilized across a wide range of extreme operating conditions, and accurately capturing this variability is essential for developing a robust and generalizable predictive model. To provide an initial assessment of the model’s extrapolation capability, we evaluated it using viscosity data for Krytox GPL102 oil reported by Harris68. Given the frequent application of these materials in high-temperature environments, we specifically selected data at 363.15 K to test the model’s performance under such conditions. The model achieved an RMSE of 0.1764 and an AAPRE of 2.8549, demonstrating its high accuracy in predicting the viscosity of PFPEs beyond the range of the training data.

Sensitivity analysis

The relevance factor (r) and the GPR model’s output were utilized to evaluate the relative importance of each input parameter in influencing viscosity. The correlation coefficient corresponding to each input variable was calculated using Eq. 1369,70,71:

\(I_{i,k}\) and \(\overline{{I_{k} }}\) represent the ith average values of the kth input, respectively. k represents the density or temperature. \(y_{i}\) and \(\overline{y}\) represent the ith predictive value and average output values, respectively. A positive \(r\) suggests that as the input increases, the output also increases, whereas a negative \(r\) signifies an inverse relationship. The closer the value of \(r\) is to 1, the more strongly the input and output of the model are correlated. The findings of the sensitivity analysis on the results of the GPR model as the best-obtained model are presented in Fig. 15. As shown in this figure, density has a direct relationship with viscosity and greatly affects the predictions of the model with a correlation coefficient of 0.6429. Also, n directly affects viscosity predictions with a factor of 0.416. On the other hand, temperature had an inverse relationship with viscosity estimation with a corresponding value of 0.473.

Implementation of the leverage method

Leverage analysis allows for the detection of outliers and the establishment of boundaries within which forecasts are considered reliable, as illustrated by the Williams plot in Fig. 16. Consequently, detecting outliers plays a vital role in improving the model’s precision and robustness. The Williams plot, which maps standardized residuals (R) against leverage values (H), serves as a diagnostic tool for identifying such anomalies. The essential parameters required to generate this plot are calculated using the following expressions (Eqs. 14–16)72,73:

-

Hat matrix (H):

Here, XT represents the transpose of the matrix X, which is a (y × d) matrix. In this case, y refers to the number of data points, and d refers to the number of input variables used by the model.

-

Leverage limit (H*):

-

standardized residuals (SR):

The variables zi and Hii correspond to the error and hat indices associated with the ith data point. Data points with leverage values (H) exceeding the critical threshold (H*) lie outside the model’s applicability domain. Meanwhile, points with H values below H* but standardized residuals (R) beyond ± 3 are flagged as potential outliers. Conversely, points with H < H* and R within the range of –3 to + 3 are regarded as reliable. As illustrated in Fig. 16, two observations are classified as suspected data due to their position outside the model’s valid zone. This results in 118 valid points, accounting for approximately 98.33% of the dataset. The Williams plot thus verifies that the vast majority of the data (98.33%) fall within acceptable bounds, reflecting the robustness of both the data acquisition process and the reliability of the dataset employed in this work74. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 16, the predicted viscosity values show excellent agreement with the experimental data, yielding minimal residuals across the full range of Hat values. This consistent performance suggests that the model was trained on high-quality, well-distributed data characterized by strong underlying patterns. Additionally, it highlights the capability of the GPR model to accurately capture complex, nonlinear relationships within the dataset, which contributes significantly to its robust predictive accuracy.

Study limitations and future recommendations

The dataset used, although reliable, may not fully capture the variability present in broader industrial and environmental conditions, which can limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the current input features may not include all relevant physicochemical properties influencing viscosity. Incorporating a wider range of experimental data covering broader temperature and pressure conditions, as well as including critical properties of PFPEs such as molecular weight, critical temperature, and critical pressure could further enhance the model’s predictive accuracy and robustness. Another key concern is the possibility of inherent biases within the dataset, such as overrepresentation or underrepresentation of certain input conditions, which may influence the model’s learning and reduce its generalizability. Additionally, since machine learning models are data-driven, their ability to make accurate predictions is limited to the range and distribution of the training data. This introduces a risk when the model is applied to extrapolate beyond the observed data range, potentially leading to unreliable or misleading outcomes in real-world scenarios. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for responsible deployment and highlights the need for continuous validation with new, diverse data to ensure robust and reliable model performance. Future work should also explore model validation with external datasets, and the integration of domain knowledge to improve interpretability and facilitate broader industrial deployment.

Conclusion

Understanding the viscosity behavior of Perfluoropolyether (PFPE) oils is essential for ensuring effective lubrication and protecting equipment, especially in high-precision applications such as aerospace, semiconductors, and other advanced technologies where traditional lubricants are inadequate. In this study, the viscosity of six PFPE oil compounds was predicted using four machine learning models: Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and AdaBoost-SVR. Among these models, the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) approach demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy and reliability. It achieved the lowest prediction errors with an average absolute percentage relative error (AAPRE) of 0.07380 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.45354. Based on AAPRE values, the overall model performance ranked as follows: GPR > AdaBoost-SVR > MLP > SVR. To further evaluate the innovation and effectiveness of the GPR model, its predictions were compared with those from conventional Waterton and VFT empirical correlations. The comparison revealed that the GPR model not only delivered superior accuracy, but also effectively captured the underlying physicochemical trends governing PFPE viscosity. Specifically, the model correctly identified that viscosity increases with higher density, lower temperature, and longer alkyl or polymer chains. Sensitivity analysis confirmed that density is the most influential factor affecting PFPE oil viscosity. Moreover, the robustness and reliability of the dataset were validated using the leverage method, which showed that 98.33% of the data points fell within the model’s domain of applicability, with only a few considered potential outliers. In summary, this work highlights the power of machine learning, particularly GPR, as an advanced tool for accurately predicting the viscosity of PFPE oils. It underscores the importance of data-driven approaches in optimizing lubricant performance for demanding environments where conventional models and materials may fall short.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Buck, R. C. et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: Terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 7, 513–541 (2011).

Kissa, E. Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellents Surfactant Science Series (CRC Press, 2001).

Soto, D., Ugur, A., Farnham, T. A., Gleason, K. K. & Varanasi, K. K. Short-fluorinated iCVD coatings for nonwetting fabrics. Adv. Func. Mater. 28, 1707355 (2018).

Walters, K. B., Schwark, D. W. & Hirt, D. E. Surface characterization of linear low-density polyethylene films modified with fluorinated additives. Langmuir 19, 5851–5860 (2003).

Camaiti, M. et al. An environmental friendly fluorinated oligoamide for producing nonwetting coatings with high performance on porous surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 37279–37288 (2017).

Demir, T. et al. Toward a long-chain perfluoroalkyl replacement: Water and oil repellency of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) films modified with perfluoropolyether-based polyesters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 24318–24330 (2017).

Masuko, M., Jones, W. R. Jr. & Helmick, L. S. Tribological characteristics of perfluoropolyether liquid lubricants under sliding conditions in high vacuum. J. Synth. Lubr. 11, 111–119 (1994).

Wang, X. et al. Synthesis and properties of cyclotriphosphazene and perfluoropolyether-based lubricant with polar functional groups. Lubr. Sci. 29, 31–42 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Highly thermally stable cyclotriphosphazene based perfluoropolyether lubricant oil. Tribol. Int. 90, 257–262 (2015).

Zhao, M. et al. The Phase rule, its Deduction and Application. In: The Boundary Theory of Phase Diagrams and its Application: Rules for Phase Diagram Construction with Phase Regions and their Boundaries. pp. 3–28 (2011).

Xie, Y. Perfluoroalkylpolyethers lubricant. Synth. Lubr. 32, 38r42 (2005).

Feng, D.-P., Weng, L.-J. & Liu, W.-M. Progress of tribology of perfluoropolyether oil. Mocaxue Xuebao Tribol. 25, 597–602 (2005).

Song, J. et al. Perfluoropolyether/poly (ethylene glycol) triblock copolymers with controllable self-assembly behaviour for highly efficient anti-bacterial materials. RSC Adv. 5, 64170–64179 (2015).

Bai, Y. et al. Supramolecular PFPE gel lubricant with anti-creep capability under irradiation conditions at high vacuum. Chem. Eng. J. 409, 128120 (2021).

Shanmugapriya, S. et al. Recent research trends in perfluoropolyether for energy device applications: A mini review. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 61, 1–14 (2024).

Sadeghi, F., Trope, E. J. & Schnell, T. J. Performance characteristics of perfluoroalkylpolyether synthetic lubricants. Tribol. Trans. 39, 849–854 (1996).

Zhu, L., Dong, J. & Zeng, Q. High temperature solid/liquid lubrication behaviours of DLC films. Lubr. Sci. 33, 229–245 (2021).

Sun, J., Li, A. & Su, F. Excellent lubricating ability of functionalization graphene dispersed in perfluoropolyether for titanium alloy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 1391–1401 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Dual fluorination of polymer electrolyte and conversion-type cathode for high-capacity all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 7914 (2022).

Yang, Q., Hu, J., Meng, J. & Li, C. C-F-rich oil drop as a non-expendable fluid interface modifier with low surface energy to stabilize a Li metal anode. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3621–3631 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Solid electrolytes reinforced by infinite coordination polymer nano-network for dendrite-free lithium metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 41, 436–447 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. Confinement effect and air tolerance of Li plating by lithiophilic poly (vinyl alcohol) coating for dendrite-free Li metal batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 22257–22264 (2019).

Meng, J. et al. Lithium ion repulsion-enrichment synergism Induced by core-shell ionic complexes to enable high-loading lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23256–23266 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Open framework perovskite derivate SEI with fluorinated heterogeneous nanodomains for practical Li-metal pouch cells. Nano Energy 113, 108523 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. A new fluorine-containing star-branched polymer as electrolyte for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Polymer 146, 249–255 (2018).

Lee, M.-J. et al. Ethylene oxide–based polymer electrolytes with fluoroalkyl moieties for stable lithium metal batteries. Ionics 26, 4795–4802 (2020).

Cong, L. et al. Role of perfluoropolyether-based electrolytes in lithium metal batteries: Implication for suppressed Al current collector corrosion and the stability of Li metal/electrolytes interfaces. J. Power Sources 380, 115–125 (2018).

Khurshudov, A. & Waltman, R. The contribution of thin PFPE lubricants to slider–disk spacing. Tribol. Lett. 11, 143–149 (2001).

Tao, Z. & Bhushan, B. Bonding, degradation, and environmental effects on novel perfluoropolyether lubricants. Wear 259, 1352–1361 (2005).

Wang, S. et al. Chemical grafting fluoropolymer on cellulose nanocrystals and its rheological modification to perfluoropolyether oil. Carbohyd. Polym. 276, 118802 (2022).

Rudnick, L. R. Synthetics, Mineral Oils, and Bio-Based Lubricants: Chemistry and Technology (CRC Press, 2020).

Jones, W. R. Jr. Properties of perfluoropolyethers for space applications. Tribol. Trans. 38, 557–564 (1995).

Alatefi, S., Agwu, O. E., Amar, M. N. & Djema, H. Explainable artificial intelligence models for estimating the heat capacity of deep eutectic solvents. Fuel 394, 135073 (2025).

Agwu, O. E., Elraies, K. A., Alkouh, A. & Alatefi, S. Mathematical modelling of drilling mud plastic viscosity at downhole conditions using multivariate adaptive regression splines. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212584 (2024).

Agwu, O. E., Alatefi, S., Alkouh, A., Abdel Azim, R. & Wee, S. C. Carbon capture using ionic liquids: An explicit data driven model for carbon (IV) oxide solubility estimation. J. Clean. Prod. 472, 143508 (2024).

Alatefi, S., Agwu, O. E. & Alkouh, A. Explicit and explainable artificial intelligent model for prediction of CO2 molecular diffusion coefficient in heavy crude oils and bitumen. Res. Eng. 24, 103328 (2024).

Qin, Z., Wang, F., Tang, S. & Liang, S. A machine learning approach to predict fluid viscosity based on droplet dynamics features. Appl. Sci. 14, 3537 (2024).

Fortin, T. J., Laesecke, A. & Widegren, J. A. Measurement and correlation of densities and dynamic viscosities of perfluoropolyether oils. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 8460–8471 (2016).

Sheshpari, M. A review of underground mine backfilling methods with emphasis on cemented paste backfill. Electron. J. Geotech. Eng. 20, 5183–5208 (2015).

Zabihi, R., Mowla, D. & Karami, H. R. Artificial intelligence approach to predict drag reduction in crude oil pipelines. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 178, 586–593 (2019).

Karimi, M., Vaferi, B., Hosseini, S. H. & Rasteh, M. Designing an efficient artificial intelligent approach for estimation of hydrodynamic characteristics of tapered fluidized bed from its design and operating parameters. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 259–267 (2018).

Gardner, M. W. & Dorling, S. R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 32, 2627–2636 (1998).

Zabihi, R., Schaffie, M., Nezamabadi-Pour, H. & Ranjbar, M. Artificial neural network for permeability damage prediction due to sulfate scaling. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 78, 575–581 (2011).

Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Larestani, A., Menad, N. A. & Hajirezaie, S. Applications of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in the Petroleum Industry (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2020).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Fu, Y. et al. Prediction of the solubility of fluorinated gases in ionic liquids by machine learning with COSMO-RS-based descriptors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 364, 132413 (2025).

Ben-Hur, A. & Weston, J. In: Data Mining Techniques for the Life Sciences pp. 223–239 (Springer, 2009).

Rabbani, Y., Shirvani, M., Hashemabadi, S. H. & Keshavarz, M. Application of artificial neural networks and support vector regression modeling in prediction of magnetorheological fluid rheometery. Colloids Surf. A 520, 268–278 (2017).

Wilson, A. G., Knowles, D. A. & Ghahramani, Z. Gaussian Process Regression Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1110.4411 (2011).

Seeger, M. Gaussian processes for machine learning. Int. J. Neural Syst. 14, 69–106 (2004).

Wang, B. & Chen, T. Gaussian process regression with multiple response variables. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 142, 159–165 (2015).

Obaid, R. J. et al. Novel and accurate mathematical simulation of various models for accurate prediction of surface tension parameters through ionic liquids. Arab. J. Chem. 15, 104228 (2022).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 55, 119–139 (1997).

Amar, M. N., Shateri, M., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. & Alamatsaz, A. Modeling oil-brine interfacial tension at high pressure and high salinity conditions. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 183, 106413 (2019).

Mohammadi, M.-R. et al. Modeling the solubility of light hydrocarbon gases and their mixture in brine with machine learning and equations of state. Sci. Rep. 12, 14943 (2022).

Sheikhshoaei, A. H., Sanati, A. & Khoshsima, A. Deep learning models to predict CO2 solubility in imidazolium-based ionic liquids. Sci. Rep. 15, 26445 (2025).

Hajinajaf, N., Rabbani, Y., Mehrabadi, A. & Tavakoli, O. Experimental and modeling assessment of large-scale cultivation of microalgae Nannochloropsis sp. PTCC 6016 to reach high efficiency lipid extraction. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 5511–5528 (2022).

Hajinajaf, N., Fallahi, A., Rabbani, Y., Tavakoli, O. & Sarrafzadeh, M.-H. Integrated CO2 capture and nutrient removal by microalgae chlorella vulgaris and optimization using neural network and support vector regression. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 13, 4749–4770 (2022).

Brush, S. G. Theories of liquid viscosity. Chem. Rev. 62, 513–548 (1962).

Vogel, H. Das temperaturabhangigkeitsgesetz der viskositat von flussigkeiten. Phys. Z. 22, 645–646 (1921).

Fulcher, G. S. Analysis of recent measurements of the viscosity of glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 8, 339–355 (1925).

Tammann, G. & Hesse, W. Die Abhängigkeit der Viscosität von der Temperatur bie unterkühlten Flüssigkeiten. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 156, 245–257 (1926).

Waterton, S. The viscosity-temperature relationship and some inferences on the nature of molten and of plastic glass. J. Soc. Glass Technol 16, 244–247 (1932).

Mauro, J. C., Yue, Y., Ellison, A. J., Gupta, P. K. & Allan, D. C. Viscosity of glass-forming liquids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 19780–19784 (2009).

Kushima, A. et al. Computing the viscosity of supercooled liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 130, 224504 (2009).

Zheng, Q., Mauro, J. C., Ellison, A. J., Potuzak, M. & Yue, Y. Universality of the high-temperature viscosity limit of silicate liquids. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 83, 212202 (2011).

Sheikhshoaei, A. H. & Sanati, A. New insight into viscosity prediction of imidazolium-based ionic liquids and their mixtures with machine learning models. Sci. Rep. 15, 22672 (2025).

Harris, K. R. Temperature and pressure dependence of the viscosities of Krytox GPL102 oil and di (pentaerythritol) hexa (isononanoate). J. Chem. Eng. Data 60, 1510–1519 (2015).

Chen, G. et al. The genetic algorithm based back propagation neural network for MMP prediction in CO2-EOR process. Fuel 126, 202–212 (2014).

Esfahani, S., Baselizadeh, S. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. On determination of natural gas density: Least square support vector machine modeling approach. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 22, 348–358 (2015).

Sheikhshoaei, A. H. & Khoshsima, A. Machine and deep learning models for predicting high pressure density of heterocyclic thiophenic compounds based on critical properties. Sci. Rep. 15, 25465 (2025).

Gramatica, P. Principles of QSAR models validation: Internal and external. QSAR Comb. Sci. 26, 694–701 (2007).

Rousseeuw, P. J. & Leroy, A. M. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection (John Wiley & sons, 2003).

Sheikhshoaei, A. H., Khoshsima, A. & Zabihzadeh, D. Predicting the heat capacity of strontium-praseodymium oxysilicate SrPr4(SiO4)3O using machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid models. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 17, 100154 (2025).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amir Hossein Sheikhshoaei: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation Reza Zabihi: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikhshoaei, A.H., Zabihi, R. Machine learning approach to predict the viscosity of perfluoropolyether oils. Sci Rep 15, 35273 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19042-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19042-2