Abstract

Although biochar can mitigate the incidence of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) bacterial wilt under continuous cropping conditions, the underlying soil micro-ecological mechanisms remain unclear. Therefore, this study evaluated the diversity and structure of the rhizosphere microbial community under different biochar application rates (Y0 = 0; Y1 = 3.75; Y2 = 7.50; Y3 = 15.00; Y4 = 30.00; t ha–1) and health statuses (H = healthy and D = diseased) during the mature period of sesame under continuous cropping conditions using 16 S rDNA and ITS amplicon sequencing. The results indicated that the sesame yield under Y3 (15.00 t ha–1) increased by 6.29% compared with that of the control (Y0). Compared with that in Y3H, the relative abundance (RA) of Macrophomina in Y3D increased significantly, by 2.03 percentage points. Moderate biochar application reduced the relative abundance of Ralstonia and Macrophomina in diseased plants, with D having a greater RA than H did. The fungal species with notable differences in Y3H were g_Parasola; however, g_Alternaria was present in Y3D. Compared with those in Y3D, the RAs of p_Chloroflexota, o_Rhizobiales_A_504721, and g_Ohtaekwangia in Y3H increased by 0.850, 0.213, and 0.094 percentage points, respectively. However, those of the bacterial genera g_Nitrospira_C, g_Phenylobacteria, g_KBS296, and g_Sinomonas were opposite in Y3D. Overall, moderate biochar (15.00 t ha–1) was beneficial for the growth of continuously cropped sesame.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rice husk biochar (RHB) is produced through the pyrolysis of rice husks, an agricultural byproduct, under limited oxygen conditions at temperatures typically ranging from 300 to 700 °C1,2. It is characterized by its high porosity, large surface area, alkaline pH, and significant carbon content, which contribute to its effectiveness as a soil amendment3,4,5. Additionally, RHB contains essential macro- and micronutrients, including nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and silicon (Si), which are gradually released into the soil, increasing nutrient availability1,6,7. Several studies have reported that RHB application significantly enhances soil physicochemical properties, including pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), water retention, and nutrient availability1,2,8,9. For example, RHB application at 7.5 t ha–1 shifted the soil pH toward slightly alkaline conditions, improving nutrient solubility and reducing aluminum toxicity2. Moreover, RHB enhances soil organic carbon (SOC) and total nitrogen (TN), promoting long-term carbon sequestration9 and improving the availability of nutrients, particularly exchangeable NH4+, NO3–, and available P1.

RHB significantly influences soil microbial diversity and enzymatic activities, fostering beneficial microbial communities that enhance nutrient cycling. Metagenomic analyses have revealed that RHB application increases the abundance of Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Nitrospira, which are crucial for organic matter decomposition and nitrogen fixation9. Additionally, RHB promotes the growth of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria such as Thiobacillus, Pseudomonas, and Flavobacterium, thereby increasing phosphorus availability10. Furthermore, RHB application also increased the abundances of the bacterial genera Massilia and Bacillus and the fungal genus Trichocladium, which have plant growth-promoting abilities11. Moreover, biochar increases the population of biocontrol and plant growth-promoting microbes, reduces the survival of Fusarium in soil, increases the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria, and effectively prevents tomato Fusarium crown and root rot disease12,13. The effectiveness of RHB varies with application rate, soil type, and crop species. Studies suggest that moderate RHB doses (5–15 t ha–1) are optimal for improving soil fertility and crop yield. For example, 5 t ha–1 significantly increased N, P, and K uptake in rice, increasing grain yield by increasing soil TN and NH4+-N without increasing greenhouse gas emissions1,14. Moreover, 10–20 t ha–1 improved SOC, P availability, and microbial biomass, leading to increased yields of rice and radish9,10,15. However, excessive biochar application (22.5 t ha–1) reduces the effectiveness of soil water storage, leads to salt accumulation, decreases the soil profile nitrate nitrogen content, and increases maize water consumption16. Therefore, a balanced approach that combines RHB (5–20 t ha–1) with organic or chemical fertilizers is recommended for sustainable soil management9,14. Optimal application rates should be tailored to specific soil and crop requirements to maximize benefits while avoiding potential negative effects.

Continuous cultivation over several years has led to a significant decline in soil bacterial populations and α diversity (as measured by the Shannon index)17. This practice alters bacterial community composition by increasing the abundance of Actinobacteria and Chloroflexi while reducing Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria17. Such disturbances in soil micro-ecology can result in severe crop diseases, posing a major barrier to continuous cropping systems18. Furthermore, distinct differences exist between healthy and diseased plants regarding the composition and function of microbial communities in rhizosphere soil19. For example, rhizosphere soil from diseased plants presents a markedly reduced ratio of gram-positive bacteria to Actinomycetes, with Proteobacteria dominating in infected Panax notoginseng20. In contrast, the rhizosphere of healthy plants accumulates beneficial bacterial phyla involved in nitrogen cycling, such as Gemmatimonadetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Nitrospirae21. Many studies have explored the structure, composition, and function of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil of healthy and diseased sesame plants under various conditions, including varying nitrogen fertilizer levels, nitrate-ammonium nitrogen ratios, and sampling periods22,23,24. Soil-borne diseases caused by pathogenic fungi and bacteria often lead to substantial crop production losses. While chemical control methods are commonly employed, they impose a heavy ecological burden and have become less effective because of the evolving resistance of pathogenic microorganisms25. Excessive use of chemical agents not only poses pollution risks but also accelerates pathogen resistance, further complicating disease management25.

Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.), a high-value oil crop in China and globally, faces significant agricultural challenges, particularly bacterial wilt, a devastating soil-borne disease26. Currently, effective prevention and control technologies for this disease are lacking26,27. Crop health is intricately linked to the interplay between soil physicochemical properties and plant-associated microbial communities. The incidence of sesame bacterial wilt is closely associated with imbalances in the rhizosphere soil microbial community structure22,23,24,28. Core microbial species, such as Nitrospirillum and Singulisphaera, play a vital role in plant health by enhancing microbial community cooperation and network complexity. These taxa are strongly linked to disease suppression and are crucial for modulating network cohesion and modularity29. Research has shown that rice husk biochar-induced changes in soil physicochemical properties and structure can benefit crop growth. However, the effects of various biochar quantities remain inconsistent, particularly under continuous cultivation conditions. Further investigations are needed to elucidate how rice husk biochar influences bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame plants, especially during the bacterial wilt phase. Given the potential of biochar to mitigate continuous cropping challenges in many crops30, we hypothesized that biochar could optimize the diversity and structure of microbial communities in sesame rhizosphere soil, including increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria. Nevertheless, the application of biochar to address continuous cropping issues in sesame remains poorly understood. Addressing these knowledge gaps is essential for improving sesame soil conditions under continuous cropping and promoting healthy crop growth. To this end, a field study was conducted in which five biochar application rates were applied to rhizosphere soil from both healthy and diseased sesame plants during continuous cropping. This study aimed to address the following questions:

(1) How do disease severity (healthy vs. diseased) and varying biochar doses affect the microbial community composition and diversity indices in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame? (2) Which bacterial and fungal species, along with environmental factors, contribute to preventing sesame bacterial wilt? (3) What are the correlations—positive or negative—between bacterial/fungal species and key environmental factors?

Materials and methods

The production process and main characteristics of rice husk biochar

The biochar used in this study was produced by Fengxin Ruitian New Energy Co., Ltd. (Jiangxi Province, China) using a Huifeng-800 model rice husk carbonization system. The production process involved pyrolyzing rice husks (moisture content < 10%) in a gasifier at about 500 °C. During pyrolysis, volatile components in the rice Husks are converted into combustible gas, while the remaining fixed carbon and ash form the biochar. The production yield was about 28%, with the resulting biochar containing 53.95% fixed carbon and 43.03% ash. Prior to use, the rice husk biochar was sieved through a 5 mm mesh. The complete physicochemical characteristics of the biochar are presented in Table 1. Most of the properties and characteristic data of the rice husk biochar in this table1 were sourced from the table S1 in the supplementary materials of the author’s recently published paper[00] (Wang et al., 2025)31.

Study site and experimental design

The experimental site was situated in Xiangcheng Town, Gao’an City, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, China (28°14’31.05” N; 115°07’40.60” E). The average monthly temperatures from July to September 2022 were 29.8 °C, 28.4 °C, and 28.5 °C, respectively, accompanied by rainfall amounts of 85.6 mm, 265.0 mm, and 6.4 mm, respectively. Since August 21, 2022, rainfall has decreased significantly, and the combination of high temperatures and drought conditions has affected sesame production.

The soil texture type was loam, and the occurrence type was red soil dryland. Before sesame cultivation, the soil had the following characteristics: pH of 6.51, soil organic matter (SOM) content of 8.72 g kg–1, available phosphorus (AP) content of 17.60 mg kg–1, available potassium (AK) content of 205.0 mg kg–1, available boron (AB) content of 0.31 mg kg–1, and total nitrogen (TN) content of 0.095%. The soil nutrient parameters were analyzed following Bao32, using standardized methods. The soil organic matter (SOM) was determined by the potassium dichromate volumetric method, total nitrogen (TN) by the Kjeldahl method, available potassium (AK) by flame photometry with ammonium acetate extraction, available phosphorus (AP) by the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method with sodium bicarbonate extraction, pH by the electrode method (soil: water ratio = 2.5:1), and available boron (AB) by the curcumin colorimetric method with boiling water extraction.

These investigations were conducted under continuous sesame cropping for two years, which is equivalent to ongoing planting into the third year and the planting of rapeseed every year in winter. Sesame seeds were planted in the first two years, but no biochar treatment was carried out. Only in the third year were comparative experiments conducted on the effectiveness of different biochar dosages. The local sesame variety Jinhuangma (non-wild species) was used in this study. Sesame seeds were independently collected and propagated by the Institute of Soil Fertilizer and Resources Environment of the Jiangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences. This study investigated the effects of five biochar treatments derived from rice husks (Y0: 0; Y1: 3.75; Y2: 7.50; Y3: 15.00; Y4: 30.00 t ha–1) on the diversity and structural composition of rhizosphere soil microbial communities in the presence of healthy plants (H; level 0) and severely diseased plants (D; level 9; where the diseased plants had withered and died) affected by bacterial wilt disease during sesame maturation. The experiment consisted of five treatments with three replicates each, totaling 15 experimental plots, in a random block design. Each plot measured 15 m2 (3 m × 5 m) and was planted with a density of 300,000 plants ha–1 across eight rows spaced 9.0 cm apart, with about 35 cm between rows. Sesame was planted on July 2, 2022, and harvested on September 14, 2022. The fertilizer applied included 25 kg ha–1 of 48% compound fertilizer (N: P2O5:K2O = 16:16:16) and 15 kg ha–1 of boron fertilizer. The biochar was mixed evenly with the compound fertilizer and boron fertilizer and applied as basal fertilizer on the soil surface one day before sesame sowing, followed by thorough plowing. The same wilt disease classification followed the criteria outlined in Li, et al.26. Concurrent measurements of soil environmental factors such as pH, SOM, TN, AP, AK, and AB were conducted. The field management practices included sesame disease prevention, weed and pest control, thinning, and seedling planting.

Determining sesame yield and collection of rhizosphere soil samples

At maturity, the severity of bacterial wilt disease was evaluated using the methods described by Li, et al.26 and Wang, et al.33. Five healthy plants from the rhizosphere soil of each biochar treatment at maturity were mixed to form a rhizosphere soil sample, and the rhizosphere soil of these plants was collected using the shaking root method. Additionally, rhizosphere soil samples were also taken from five diseased plants in the same plot and mixed into one rhizosphere soil sample. In total, 30 rhizosphere soils were sampled from 15 plots. These samples were divided into two parts: one for analyzing the soil chemical properties and the other for assessing the diversity and structural composition of the rhizosphere soil microbiota. The soil samples designated for microbiological analysis were promptly placed in sample boxes with dry ice, stored at − 80 °C, and promptly sent to Tianjin Novogene Biological Information Technology Co., Ltd., for ITS and 16 S rDNA amplicon sequencing after impurities were removed. Moreover, basic agronomic characteristics, yield, yield components, and other relevant indicators were examined in five healthy plants.

Following the collection of rhizosphere soil samples, all the sesame seeds were harvested from the field, placed in mesh bags, dried outdoors for about seven days, and then threshed and weighed. Additionally, the sesame yield from healthy plants was determined using rhizosphere soil samples and converted to yield per unit area.

PCR amplification, library construction, and sequencing

Genomic DNA extraction, as well as the assessment of DNA purity and concentration, followed methods described in other studies23. For soil fungi, the ITS1F (5’-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGTAAGTAA-3’) and ITS2R (5’-GCTGTGTTCATCGATGC-3’) primers were used to amplify the ITS1-1 F variable region via PCR34. The V3 ~ V4 variable region of soil bacteria was amplified by PCR using the primers 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGGGGCAGCA-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’)23. The reaction system and PCR conditions were described previously Ren, et al.34. In brief, the PCR process included an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by cycling at 94 °C for 30 min, 48 °C for 50 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, resulting in a final elongation step at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplified products were quantified in New Taipei City, Taiwan, China, via Qsep-400 after purification with an Omega DNA purification kit (Omega Inc., USA). The amplicon library (2 × 250) was sequenced by Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd., via an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system. Each rhizosphere soil sample was sequenced with a single biological and technical replicate, resulting in 60 datasets of bacterial and fungal sequences from rhizosphere soil sequences. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1078122?reviewer=5b7ljf2ug4as2ajlgstbknhn1d, accession number - PRJNA1078122.

High-throughput sequencing

Second-generation data processing workflow: First, Trimomatic35 (version 0.33) was used to perform quality filtering on the raw data. Then, Cutadapt36 (version 1.9.1) was used to identify and remove primer sequences. Afterwards, USEARCH37 (version 10) was used to concatenate the two-end reads, and chimeras were removed (UCHIME38version 8.1). Finally, high-quality sequences were obtained for subsequent analysis. The specific parameters were as follows: the Trimomatic parameter was set to a 50 bp window. If the average quality value within the window was less than 20 bp, the backend bases would be truncated from the window. Primer sequence identification and removal were performed. Cutadapt software was used to identify primer sequences based on parameters that allowed a maximum mismatch rate of 20% and a minimum coverage of 80%. PE reads were stitching. Usearch v10 software was used to stitch the reads of each sample according to the minimum overlap length of 10 bp, the minimum similarity allowed in the overlap area of 90%, and the maximum number of mismatched bases of 5 bp. If each of the two parent sequences had a sequence that was more than 80% similarity to the query sequence, it was determined that the query was a chimera.

Amplicon sequence variations (ASVs) were generated using Dada2, samples with ASV counts less than three were filtered out, and clean read feature classification was conducted39. The representative sequences of the OTUs were aligned to the pre-trained UNITE database (ITS, version 8.2) using the QIIME2 (version 2020.6) feature classifier plugin, which produced a table of fungal classification information at the species level. Similarly, for bacterial classification, representative sequences were aligned to the pre-trained GREENGENES2 database (version 2022.10; V3-V4 region) with 99% similarity. Mitochondrial and chloroplast sequences were removed using QIIME2 following species identification. The QIIME2 core diversity plugin was used to construct the diversity matrix. Alpha diversity indices at the feature sequence level, including the Shannon index, were computed to assess sample diversity. Beta diversity analysis uses the binary jaccard algorithm to calculate the distance between samples and obtain the beta values between samples. Beta diversity indices were used to evaluate differences in microbial community structure among samples. Principal component analysis (PCA), UPGMA tree clustering (python2, v3.0.0b35), and PERMANOVA were subsequently performed to analyze the results40.

Statistical analysis

Agronomic traits, yield, yield composition factors, and sesame incidence rates were analyzed by ANOVA and the least significant difference (LSD) test at the 0.05 level. ANOVA and LEfSe were performed to identify bacteria and fungi that differed in abundance between the groups41. Redundancy analysis (RDA) and mantel tests were performed using the “vegan” package in R (version 2.3–0) to evaluate potential relationships between microbial communities and environmental factors42. Default parameter settings were used unless otherwise specified for all analyses mentioned above. When the random forest method was used to analyze the importance of differential microorganisms in the current group, the higher the importance, the more likely the substance was to be a differential marker that distinguished the current group.

Results

Sesame yield and yield component factors

No significant differences were detected in sesame agronomic traits across the five treatments, including parameters such as plant height and initial capsule position, as well as yield components, such as thousand-grain weight, number of seeds per capsule, number of capsules per plant, and sesame yield (Table 2). Compared with the control, the Y3 treatment (15 t ha–1 biochar) significantly increased the sesame yield by 6.29% (Y0; p < 0.05), which was greater than that in the other biochar treatments. The variation pattern of the disease index was similar to that of the sesame yield (Table 2).

There was a highly significant positive correlation between plant height and the initial capsule part, number of capsules per plant, number of grains per capsule, and thousand-grain Weight, and there was also a significant positive correlation between the number of capsules per plant and the number of grains per capsule and thousand-grain Weight. There was a significant positive correlation between 1000-grain weight and the number of grains per capsule, whereas there was a significant negative correlation between yield and incidence rate (Table S1).

Microbial diversity in rhizosphere soil

Analysis of rarefaction curves revealed that both fungal and bacterial communities followed similar patterns—an initial rapid accumulation of observed species followed by stabilization—confirming that our sequencing efforts captured sufficient microbial diversity (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). There was no significant difference in the number of ASVs or reads of fungi among the 10 treatments, but there was a significant difference in the number of bacteria. Specifically, the number of ASVs from Y3H for clarity increased significantly by 13.10% and 17.87% compared with those from Y3D and Y0D, respectively, and the read count of Y3H increased significantly by 14.87% compared with that of Y0D (Table S2). The Shannon indices of fungi treated with Y3D were 26.53% and 25.20% greater than those of fungi treated with Y0H and Y4H, respectively. However, the bacterial Shannon indices of Y1H, Y2H, and Y3H significantly increased by 3.76%, 3.07%, and 3.23%, respectively, compared with those of the Y1D, Y2D, and Y3D treatments, respectively (Fig. 1a and b). The results indicated that as the biochar application rate increased, the Shannon indices of bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere soil of diseased plants first decreased but then increased (Fig. 1a and b). Conversely, the Shannon index of fungi and bacteria in the rhizosphere soil from healthy plants first increased but then decreased. Across all the treatments, with the exception of the Shannon index in the Y1 treatment, greater fungal diversity was observed in the soil from diseased plants than in that from healthy plants. Conversely, the bacterial diversity of the fungal community in the Y3D-treated plants was greater than that in the Y0H-treated plants.

Comparison of the fungal (a) and bacterial (b) Shannon indices among the different treatments. The symbols in the box plot have the following meanings: the upper and lower lines of the box represent the interquartile range (IQR); the median line represents the median; the upper and lower edges represent the maximum and minimum inner perimeter values (1.5 times IQR); and the different letters on the bar chart represent significant differences at the 0.05 level. Principal component analysis results of fungal (c) and bacterial (d) community diversity in sesame rhizosphere soil. Analysis of variance of the beta diversity of fungal (e) and bacterial (f) communities in sesame rhizosphere soil treated with different methods. Vertical sitting represents the beta distance.

The PCA of β diversity indicated that the first principal component explained 46.25% and 27.98% of the fungal and bacterial differences, respectively, between treatments, whereas the second principal component explained 12.48% and 21.87% of the fungal and bacterial differences, respectively, between treatments (with totals of 58.73% and 49.85%, respectively) (Fig. 1c and d). The PERANOVA results revealed that the differences in the β diversity of fungi and bacteria were highly significant (R2 = 0.322, p = 0.012; R2 = 0.323, p = 0.001). Among them, the Y1 and Y2 treatments presented higher binary_jaccard values for fungi from diseased plants than for those from healthy plants, whereas the other three treatments presented the opposite trend (Fig. 1e). The binary_jarad values of bacteria in the Y3 and Y4 treatment groups were greater for the healthy plants than for the diseased plants, whereas the other three treatments had the opposite effect (Fig. 1f). The results of the clustering analysis revealed that both fungi and bacteria could be categorized into two distinct groups: those originating from healthy plants and those from diseased plants (Figures S3a and S3b).

Composition of the microbial community

The fungal community was composed mainly of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, accounting for 53% of the total relative abundance. However, the RA of the healthy plants exhibited the opposite trend, and the abundance of Ascomycota in the D treatment first decreased but then increased with increasing biochar application. The changes in Basidiomycota showed an opposite pattern to that of Ascomycota (Figure S4a). Aspergillus and Fusarium were the predominant fungal genera. The RAs of Aspergillus in D first tended to increase but then decreased and then increased and then decreased with increasing biochar application, whereas in healthy plants, the RAs tended to increase first, then decrease, and then increase again. The RA of Fusarium in the D treatment first decreased, then increased, and finally decreased again with increasing biochar application, in contrast with its trend in healthy plants. The RAs of Aspergillus and Fusarium were greater in the D treatment than in the H treatment (Figure S4b). LEfSe analysis revealed significant differences in fungal species, such as Y0D, Y1D, Y3D, Y3H, and Y4D, among the five treatments (Fig. 2a). The g_Macropomina significantly differed in the Y0D treatment group (Fig. 2a). In Y3D, significant variations were observed in fungal species such as g_Alternaria. However, the number of fungal species with notable differences in Y3H was low, with g_Parasola (Fig. 2a). These findings indicated that biochar could not only optimize the fungal community composition but also decrease the abundance of pathogenic fungi (Fig. 3a). Moreover, random forest analysis revealed that Macrophomina_phaseolina had the most important effect on the fungal community structure in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame (Fig. 2b).

The vertical axis displays the relative abundance of fungi (a) and bacteria (c) accompanied by LEfSe analysis highlighting differences in community structure (fungi: LDA ≥ 3.0; bacteria: LDA ≥ 3.0). The vertical axis represents the classification units with significant differences between groups, whereas the horizontal axis visually displays the logarithmic score values of LDA analysis for each classification unit using a bar chart. Random forest analysis of key fungal (b) and bacterial (d) community species in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame between different treatments. The horizontal axis is a measure of species importance. The larger the value is, the greater the accuracy of sample classification decreases after removing the species.

The bacterial phyla were mainly composed of Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, etc., with a total proportion greater than 70% (Figure S4c). When the dose of biochar increased, the RA of Actinobacteria from the D treatment first increased but then decreased, whereas that from the H treatment increased steadily (Figure S4c). However, in the Y4 treatment, the abundance in the D treatment was greater than that in the H treatment. The RA of Proteobacteria from the H treatment first increased but then decreased, whereas the abundance of Acidobacteriota decreased steadily. The RAs of Proteobacteria and Acidobacteriota from the H treatment were greater than those from the D treatment (Figure S4c).

The predominant bacterial genera included Streptomyces_G_399870, Sphingomicrobium_483265, and AG11. Generally, as biochar application increased, the RA of Streptomyces_G_399870 first increased but then decreased in the D treatment, whereas in the H treatment, it steadily increased. A significant difference was detected only in the low-biochar treatments (Y0, Y1, and Y2), with the RA of Streptomyces_G_399870 being greater in the D treatment than in the H treatment. Conversely, the RA of Sphingomicrobium_483265 in the H treatment exhibited a fluctuating pattern of decreasing, increasing, decreasing, and increasing again with increasing biochar level, whereas in the D treatment, it initially decreased, then increased, and decreased again. Overall, the RA of Sphingomicrobium_483265 was greater in the H treatment than in the D treatment (Figure S4d).

Significant variations in bacterial types among the 10 treatments were evident from the LEfSe analysis. In Y0H, there were nineteen bacterial species with significant differences in RA, such as g_Bog_209, c_Limnocylindria, and g_Udaeobacter (Fig. 2c). Y3H was significantly different in several bacterial groups, such as g_Ohtaekwangia, o_Rhizobiales_A_504721, and p_Chloroflexota (Fig. 2c). Compared with those in Y3D, the RAs of those in Y3H increased by 0.850, 0.213, and 0.094% points, respectively (Table S3). Conversely, Y3D was significantly different for bacterial species such as g_Sinomonas, g_KBS_96, and s_Phenylobacterium_kunshanense (Fig. 2c). In particular, the RAs of g_Nitrospira_C, g_Phenylobacterium, g_KBS_96, and g_Sinomonas in Y3D increased by 0.304, 0.441, 0.127, and 0.218 percentage points, respectively, compared with their RAs in Y3H (Table S3).

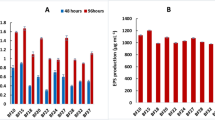

RF analysis revealed that Macrophomina phaseolina had a significant effect on the fungal community structure in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame (Fig. 2b). Because only one species, Macrophomina phaseolina, was detected in the rhizosphere soil, its relative abundance was the same as that of Macrophomina. Therefore, this study revealed only the changes in the relative abundance of Macrophomina under the different treatments. The results of the ANOVA revealed that the RAs of Macrophomina in Y0D and Y1D increased significantly, by 7.10–7.55 percentage points and 5.94–6.39 percentage points, respectively, compared with those in the other three D treatments (Fig. 3a). Compared with that in Y3H, the RA of Macrophomina in Y3D increased significantly, by 2.03 percentage points (Fig. 3a).

The random forest analysis revealed that Udaeobacter_sp003221195 had a significant effect on the bacterial community structure in the rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped sesame (Fig. 2d). Moreover, Ralstonia solanacearum could not be specifically identified by 16 S rDNA amplicon sequencing, and only s_Unclassified_Ralstonia was detected. The relative abundance of s_Unclassified_Ralstonia was consistent with that of Ralstonia. Moderate biochar application reduced the RA of Ralstonia in diseased plants, but excessive biochar (Y4) promoted its proliferation, with D having a higher RA than H did (Fig. 3b).

The impact of biochar on environmental factors and the correlation between microbial communities and environmental factors

The amount of biochar used had a significant effect on the contents of SOM, TN, AP, AK, and AB in terms of environmental factors, with Y3H showing significant increases of 363.65%, 38.73%, 46.78%, 53.92%, and 92.40%, respectively, compared with Y0H (Table S4). According to the VIF analysis, there was no multicollinearity among the six environmental factors, whether they were fungi or bacteria. Its VIF value was within the range of 2.14–6.53. The RDA results revealed that the explanatory rates of RDA1 and RDA2 for changes in fungal species abundance were 4.98% and 4.27%, respectively (Fig. 4a). Their explanations for the changes in bacterial species abundance were 5.81% and 4.25%, respectively (Fig. 4b). The RDA and Mantel test results revealed that pH and AK had the most significant effects on the fungal community structure, whereas pH and SOM had the most significant effects on the bacterial community structure (Fig. 4a and b). According to the VPA results, in terms of fungal influence, the pH + SOM group had an adj-R2 of 0.04, whereas the other four indicators had an adj-R2 of 0.02. In terms of bacteria, the pH + SOM group had an adj-R2 of 0.10, whereas the other four indicators had an adj-R2 of 0.01. Correlation heatmap analysis revealed that Leucoagaricus was positively correlated with environmental factors, such as TN, AB, SOM, AP, and AK, in fungal communities. Coprinellus had a significant negative association with SOM, whereas Condenascus had strong positive correlations with AP (Fig. 4c). In the bacterial community, AC-16, AG11, and VBCG01 presented opposite polar patterns to those of Nocardioides_A_392796 and Streptomyces_G_399870, with considerable or extremely strong negative correlations with pH (Fig. 4d).

RDA between fungal (a) and bacterial (b) communities and environmental factors among different amounts of biochar. Heatmap of the correlation between environmental factors and the structure of fungal (c) and bacterial (d) communities. The longer the arrow is, the greater the impact of the environmental factor. The smaller the angle is, the greater the correlation. The sample is located in the same direction as the arrow, indicating a positive correlation, whereas the opposite direction of the arrow indicates a negative correlation. The color corresponds to the legend, with red indicating a positive correlation and blue indicating a negative correlation. The darker the color is, the greater the correlation; if there is an *, it indicates a significant correlation (*<0.05, * *<0.001).

In terms of fungi, pH was highly significantly positively correlated with Albifibria in the Y3D treatment, while it was highly significantly negatively correlated with Clonostachys, Coprinellus, Cyanhus, and Matsushimamyces. The correlation between AK and these five species was exactly opposite to that between AK and pH. In the Y3H treatment, pH was highly significantly positively correlated with Aspergillus, Fusarium, Fusicolla, Leucoagaricus, and Xenomyrothecium, while it was negatively correlated with Coprinellus. AK was highly significantly positively correlated with Agrocybe, Condenascus, Marasmius, and Psathyrella (Figure S5a and b). In terms of bacteria, pH and SOM in the Y3D treatment were highly significantly positively correlated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and VBCG01, whereas the opposite was true for AG11 and Ramlibacter-582307. In Y3H, there was a highly significant positive correlation between pH and Usitatibacter, whereas the opposite was true for Nocardioid A_392796 and Sphingochromium-483265. SOM was highly significantly positively correlated with Chryseotalea, whereas it was exactly opposite to AC-16, AG11, Amycolatopsis-D_380830, and Mycoplasma (Figure S5c and d).

Discussion

An appropriate amount of biochar significantly improves the yield and microbial diversity of Sesame continuously

The development of healthy soil ecosystems relies heavily on soil microbes, which play critical roles in determining soil fertility and quality43. Variations in the diversity and number of soil microorganisms can influence the stability and function of these ecosystems44. Recent studies have investigated how varying concentrations of biochar affect the yields of continuously cropped plants, although the findings have been inconsistent. For example, previous research demonstrated that applying biochar at a rate of 15 t ha–1 increased the survival rate of Panax notoginseng from 6.0% in the control group to 69.5% and decreased the occurrence and severity of tobacco bacterial wilt13,45. Furthermore, biochar had been shown to increase soil pH, AP, AK, SOM, and microbial diversity while reducing NH4+-N13,45. Another study revealed a biochar dose-response curve shaped like an inverted U curve for disease severity reduction, revealing a notable 59.11% decrease in plant disease severity with 3%–5% biochar application to field soil46. These results were similar to those reported by Chen, et al.13 and Zhao, et al.45. An optimal biochar application rate of 15,000 kg ha–1 was found to increase soil fertility in fields with continuously cropped sesame, where the soil pH increased by 0.54–0.70, the SOM content increased by 36.50–36.96 g kg–1, the AK content increased by 88.67–109.63 mg kg–1, and the AB content increased by 0.12–0.25 mg kg–1 (Table S4). In rhizosphere soil, the community structures of bacterial and fungal species are significantly altered by these environmental conditions. Overall, the application of biochar reduced the frequency of plant disease under continuous sesame cropping and increased the sesame yield. The beneficial effects of biochar might be attributed to its alkaline nature and the high contents of K, Ca, Na, and other metallic minerals in its ash, which can effectively decrease the exchangeable H+ in soil and increase the pH of acidic soils47. Owing to its extensive internal surface area, high pore structure, and abundant functional groups48, biochar can absorb a variety of ions, delay the release of nutrients, and enhance the retention of soil fertility and the carbon-nitrogen ratio49. The habitat for soil microbial colonization was modified, and as the biochar application rates increased, the concentrations of SOM, TN, AP, and AK also increased50,51,52,53. Concurrently, microorganisms may use part of the easily decomposed carbon in biochar as a growth substrate. Biochar may also induce a priming effect on soil bacteria, promoting their proliferation54. The significant increase in SOM in this study could be due to the difficulty in differentiating between biochar carbon and soil carbon during analyses. Another factor is that biochar neutralizes soil acidity and increases the content of refractory organic carbon.

Some studies have shown that biochar increases the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices of soil bacterial communities, decreases fungal uniformity, and increases the abundance of beneficial bacteria55,56. However, other studies noted that biochar significantly increased maize yield and altered the β diversity of soil microbial communities, although it had no discernible effect on α diversity57. These findings matched those of Hu, et al.57, Cheng, et al.55, and Zhang, et al.56, which may be related to the settings of biochar dose treatments in their studies, where the biochar dosage was expressed either as a percentage (0.0, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0% (w/w)) or as a dosage per plant (0, 5, 10, 15 kg plant–1), whereas in this study, the dosage was expressed as per unit area. Furthermore, this study also differentiated fungal and bacterial diversity indices between root-soil disease and healthy soils. Thus, an appropriate amount of biochar can significantly increase the production and microbial diversity of continuously growing sesame crops.

Biochar can optimize the composition of fungal and bacterial community structures

Biochar can influence the composition of the soil microbial community structure by modifying the physicochemical properties of the soil58,59,60. It can regulate the nitrification process in the soil, weaken competition and cooperation between surface and subsoil microorganisms, and alter key species, thus reducing the incidence of plant diseases58,59,60. For example, the moderate application of biochar (10–20 t ha–1) effectively changed the soil aggregation patterns, size aggregate distributions, microbial habitats, and populations60. Moreover, the application of biochar (15 t ha–1) to acidic soil provides a sufficient negative charge because of its good expansion of specific surface area and pore volume, thereby absorbing additional Al 3+ and improving the soil pH61. The various biochar treatments (15, 30, and 45 t ha–1) increased the RA of potentially beneficial bacteria in the soil, whereas denitrifying bacteria and the pathogen Ralstonia presented lower RAs13. According to Wei, et al.62, most of the carbon in biochar is composed of phenolic compounds and aromatic hydrocarbons, which biochar can adsorb effectively63. The heterogeneous carbon source input from biochar can alter the abundance of fungal communities that selectively utilize organic carbon, thereby affecting the structural characteristics of the soil fungal community64,65. In this study, 6 species, including g_Macrophomina, a pathogen responsible for sesame charcoal rot, whose RA decreased with increasing biochar dosage, significantly differed in the Y0D treatment, indicating the ability of biochar to better adsorb pathogens and reduce the incidence of sesame diseases66. Parasola was the only fungal species that was significantly different in the Y3H treatment, whereas g_Alternaria was the fungal species that was significantly different in the Y3D treatment. These findings indicate that the application of biochar can decrease the abundance of pathogens and optimize the composition of the fungal community structure. The genus Parasola, within Basidiomycota, is characterized by small, delicate, short-lived, veil-less basidiocarps with deeply grooved, parasol-like pilei67 and is typically found on exposed soil, grass debris, forest litter, and herbivorous animal feces68,69,70. Members of Alternaria, belonging to Dematiaceae, can produce secondary metabolites with unique structures and biological activities71. Various Alternaria species, such as A. tenuissima, A. citri, A. brassicicola, and A. alternata, are major producers of these compounds72. Appropriate levels of biochar may increase the diversity and richness indices of the soil bacterial community; however, beyond a certain threshold, the quantity of harmful bacteria increases, whereas the number of bacterial OTUs decreases73. This might be associated with the detrimental effects of high quantities of biochar on soil properties74. This study revealed that the soil bacterial communities in the biochar treatment presented relatively high alpha diversity indices, especially those in the 15 t ha–1 treatment.

LEfSe of bacteria revealed three bacterial genera with significant differences in the Y3H treatment, namely, g_Ohtaekwangia, and four in the Y3D treatment, namely, g_Phenylobacterium, g_Sinomonas, g_KBS_96, and g_Nitrospira_C. These findings suggest that biochar application can improve the composition of the bacterial community structure, benefiting the control of disease outbreaks associated with continuous sesame cultivation. g_Ohtaekwangia belongs to the family Cyclobacteraceae_9000466 and the phylum Bacteroidetes, and the genus Ohtaekwangia is a key microorganism involved in carbon and nitrogen cycling in soil75. Moreover, it was previously described as a nitrifying bacterium76. Another advantage of this genus may be the production of compounds called marinequinolines with antibiotic, antifungal, and insecticidal properties, which can protect the rhizosphere from pathogens and predators77. It includes three species, namely, Ohtaekwangia_flava, Ohtaekwangia_koreensis, and Ohtaekwangia_kribbensis. Among the three species, Ohtaekwangia_flava accounts for the majority, but no relevant literature reports on the function of this species have been published. Furthermore, Ohtaekwangia koreensis and Ohtaekuangia ribensis were isolated from sand samples collected from the west coast of the Korean Peninsula using low-nutrient culture medium78.

The nitrogen-fixing species Phenylobacterium can increase the nitrogen content of soil79. The increased abundance of Phenylobacterium in healthy soil facilitates nutrient transformation, absorption, and secretion of glycopeptide antibiotics80. Sinomonas, originally proposed by Zhou et al. (2009) as part of Actinobacteria, comprises 10 different species (https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/sinomonas). Certain members of g_Sinomonas have demonstrated activities in nitrogen fixation, cellulose breakdown, phosphate dissolution, antimicrobial action, and plant growth promotion81,82,83,84. However, further comprehensive studies and verification are needed to determine whether these populations can contribute to the prevention and detection of bacterial wilt or provide regulatory technology for biological prevention and control. Additionally, isolating and screening disease-resistant microbial communities from the soil of healthy sesame rhizospheres can provide valuable microbial resources for the biological control of sesame bacterial wilt in the future. Lehmann, et al85. suggested that biochar might promote the reproduction of antagonistic microorganisms, compete for nutrients, and inhibit the growth of pathogens. It might also directly adsorb some antibacterial compounds. In conclusion, biochar may influence the diversity and organization of soil bacterial and fungal communities in two distinct ways. First, biochar can create an optimal environment for the growth of bacteria and fungi by providing ample nutrients and a suitable habitat. Second, the growth of bacteria and fungi is indirectly affected by biochar through the alteration of soil physicochemical properties and the activity of other microbial communities.

Conclusions

The application of 15 t ha–1 biochar improved rhizosphere microbial diversity, increased the abundance of beneficial taxa such as Ohtaekwangia and Parasola, and reduced pathogen abundance, contributing to a lower incidence of bacterial wilt. Although the application of 15.00 t ha–1 biochar helped control diseases in continuous sesame cropping and improved the structure of rhizosphere soil microbial communities, the cost and labor intensity of applying high biochar rates may limit its capacity for large-scale farming. Future research should assess alternative biochar sources, application methods (e.g., ditching), and synergistic microbial inoculants. Therefore, future research should focus on improving biochar application methods, such as ditch application, to reduce dosage and cost and provide a theoretical foundation for the large-scale promotion and application of this technology. Additionally, this study was limited to rice husk biochar and did not assess biochar from other sources. In the future, we aim to include comparative studies on the effects of different biochar sources to identify the most suitable biochar for controlling sesame diseases and enhancing soil structure and function. We aim to investigate new technologies for using less biochar without compromising its effectiveness, thereby reducing production costs and paving the way for large-scale applications in the future.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study were available in the NCBI repository, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1078122?reviewer=5b7ljf2ug4as2ajlgstbknhn1d, accession number - PRJNA1078122.

References

Selvarajh, G. et al. Enriched rice husk biochar superior to commercial biochar in ameliorating ammonia loss from urea fertilizer and improving plant uptake. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32080 (2024).

Adebajo, S. O. et al. Impacts of rice-husk biochar on soil microbial biomass and agronomic performances of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05757-z (2022).

Sashidhar, P. et al. Biochar for delivery of agri-inputs: Current status and future perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134892 (2020).

Mnyango, J. I. et al. Sustainable wastewater treatment: Mechanistic, environmental, and economic insights into biochar for synthetic dye removal. Next Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxmate.2025.100974 (2025).

Verma, A., Sharma, G., Kumar, A., Dhiman, P. & Stadler, F. J. Recent advancements in Biochar and its composite for the remediation of hazardous pollutants. Curr. Anal. Chem. 21, 15–56. https://doi.org/10.2174/0115734110286724240318051113 (2025).

Singh, C., Tiwari, S., Gupta, V. K. & Singh, J. S. The effect of rice husk Biochar on soil nutrient status, microbial biomass and paddy productivity of nutrient poor agriculture soils. Catena 171, 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.07.042 (2018).

Abdillah, A. N. et al. Impact of rice husk Biochar on soil properties and microbial diversity for paddy cultivation. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutri. 24, 7507–7524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-024-02055-7 (2024).

Abukari, A. Influence of rice husk Biochar on water holding capacity of soil in the Savannah ecological zone of Ghana. Turkish J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 7, 888–891. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v7i6.888-891.2488 (2019).

Gautam, K., Singh, P., Singh, R. P. & Singh, A. Impact of rice-husk biochar on soil attributes, microbiome interaction and functional traits of radish plants: A smart candidate for soil engineering. Plant. Stress https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100564 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Rice husk Biochar impacts soil phosphorous availability, phosphatase activities and bacterial community characteristics in three different soil types. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 116, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.03.020 (2017).

Akumuntu, A. et al. Biochar derived from rice husk: Impact on soil enzyme and microbial dynamics, lettuce growth, and toxicity. Chemosphere https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140868 (2024).

Jaiswal, A. K. et al. Molecular insights into biochar-mediated plant growth promotion and systemic resistance in tomato against fusarium crown and root rot disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 13934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70882-6 (2020).

Chen, S., Qi, G., Ma, G. & Zhao, X. Biochar amendment controlled bacterial wilt through changing soil chemical properties and microbial community. Microbiol. Res. 231, 126373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2019.126373 (2020).

Mon, W. W., Toma, Y. & Ueno, H. Combined effects of rice husk Biochar and organic manures on soil chemical properties and greenhouse gas emissions from two different paddy soils. Soil. Syst. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems8010032 (2024).

Munda, S. et al. Dynamics of soil organic carbon mineralization and C fractions in paddy soil on application of rice husk Biochar. Biomass Bioenergy. 115, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2018.04.002 (2018).

Ren, S. et al. Application of biochar in saline soils enhances soil resilience and reduces greenhouse gas emissions in arid irrigation areas. Soil Tillage. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2025.106500 (2025).

Li, J., Cheng, X., Chu, G., Hu, B. & Tao, R. Continuous cropping of cut chrysanthemum reduces rhizospheric soil bacterial community diversity and co-occurrence network complexity. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 185, 104801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104801 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Applications of Chaetomium globosum CEF-082 improve soil health and mitigate the continuous cropping obstacles for Gossypium hirsutum. Ind. Crops Prod. 197, 116586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116586 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Biochar amendment changes temperature sensitivity of soil respiration and composition of microbial communities 3 years after incorporation in an organic carbon-poor dry cropland soil. Biol. Fertility Soils. 54, 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-017-1253-6 (2018).

Wu, Z. X. et al. Comparison on the structure and function of the rhizosphere microbial community between healthy and root-rot Panax Notoginseng. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 107, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.05.017 (2016).

Ge, A. et al. Microbial assembly and association network in watermelon rhizosphere after soil fumigation for fusarium wilt control. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 312, 107336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2021.107336 (2021).

Wang, R. Q. et al. Bacterial community structure and functional potential of rhizosphere soils as influenced by nitrogen addition and bacterial wilt disease under continuous Sesame cropping. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 125, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.12.014 (2018).

Wang, R. Q. et al. Sampling period and disease severity of bacterial wilt significantly affected the bacterial community structure and functional prediction in the Sesame rhizosphere soil. Rhizosphere 26, 100704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2023.100704 (2023).

Wang, R. Q. et al. Optimizing the bacterial community structure and function in rhizosphere soil of Sesame continuous cropping by the appropriate nitrate ammonium ratio. Rhizosphere 23, 100550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2022.100550 (2022).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Research progress on the influence and mechanism of Biochar on soil-borne diseases of plants. J. Shenyang Agricultural Univ. 53, 611–619. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1700.2022.05.011 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Effects of bacterial wilt on the growth and yield traits of Sesame. J. Plant. Prot. 46, 762–769. https://doi.org/10.13802/j.cnki.zwbhxb.2019.2018104 (2019).

Li, X. S. et al. Feature and chemical control of Sesame bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 41, 932–937. https://doi.org/10.19802/j.issn.1007-9084.2019040 (2019).

Lyu, F. et al. Rhizosphere bacterial community composition was significantly affected by continuous cropping but not by Sesame genotype. Rhizosphere 27, 100750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2023.100750 (2023).

Qiao, Y. et al. Core species impact plant health by enhancing soil microbial cooperation and network complexity during community coalescence. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 188, 109231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109231 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Using Biochar for the treatment of continuous cropping obstacle of herbal remedies: A review. Appl. Soil. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105127 (2024).

Wang, R., Lyu, F., Lyu, R., He, J. & Wei, L. Mechanisms of furrow-applied biochar in enhancing rhizosphere soil microbiota and metabolites in continuous sesame cropping. Euro. J. Soil. Biol. 126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2025.103763 (2025).

Bao, S. D. Soil Agricultural-Chemical Analysis 3rd edn. (China Agriculture, 2000).

Wang, R. Q. et al. Sesame bacterial wilt significantly alters rhizosphere soil bacterial community structure, function, and metabolites in continuous cropping systems. Microbiol. Res. 282, 127649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2024.127649 (2024).

Ren, N., Wang, L., You, C. & Diversity,. Community structure, and antagonism of endophytic fungi from asymptomatic and symptomatic mongolian pine trees. J. Fungi https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10030212 (2024).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12. https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 10, 996–998. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2604 (2013).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high resolution sample inference from amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583. https://doi.org/10.1101/024034 (2016).

Ni, Y. et al. Distinct composition and metabolic functions of human gut microbiota are associated with cachexia in lung cancer patients. ISME J. 15, 3207–3220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00998-8 (2021).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

Caucci, S. et al. Seasonality of antibiotic prescriptions for outpatients and resistance genes in sewers and wastewater treatment plant outflow. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, fiw060. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiw060 (2016).

Yang, W. et al. Influence of Biochar and Biochar-based fertilizer on yield, quality of tea and microbial community in an acid tea orchard soil. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 166, 104005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104005 (2021).

Hu, W. et al. Aridity-driven shift in biodiversity–soil multifunctionality relationships. Nat. Commun. 12, 5350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25641-0 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Biochar increases Panax notoginseng’s survival under continuous cropping by improving soil properties and microbial diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 850, 157990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157990 (2022).

Yang, Y., Chen, T., Xiao, R., Chen, X. & Zhang, T. A quantitative evaluation of the biochar’s influence on plant disease suppress: a global meta-analysis. Biochar 4, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-022-00164-z (2022).

Van Zwieten, L. et al. Effects of Biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility. Plant. Soil. 327, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0050-x (2010).

Ghorbani, M. et al. How do different feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions effectively change biochar modification scenarios? A critical analysis of engineered biochars under H2O2 oxidation. Energy. Conv. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117924 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Effect of Biochar application on soil health and its potential risks to flue-cured tobacco production. Chin. Tob. Sci. 39, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.13496/j.issn.1007-5119.2018.06.013 (2018).

Zhang, G. et al. Regulation of Biochar on rhizosphere soil microecology and its control effect on tobacco bacterial wilt. Acta Tabacaria Sinica. 26, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.16472/j.chinatobacco.2020.135 (2020).

Jones, D. L., Rousk, J., Edwards-Jones, G., DeLuca, T. H. & Murphy, D. V. Biochar-mediated changes in soil quality and plant growth in a three year field trial. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 45, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.10.012 (2012).

Jaiswal, A. K. et al. Linking the belowground microbial composition, diversity and activity to soilborne disease suppression and growth promotion of tomato amended with Biochar. Sci. Rep. 7, 44382. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44382 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Effects of organic matter on nutrient, enzyme activity and functional diversity of microbial community in tobacco planting soil. Acta Tabacaria Sinica. 25, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.16472/j.chinatobacco.2018.195 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Priming effect of Biochar on the minerialization of native soil organic carbon and the mechanisms: A review. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 29, 314–320 (2018).

Cheng, J. et al. Effects of Biochar on cd and Pb mobility and microbial community composition in a calcareous soil planted with tobacco. Biol. Fertility Soils. 54, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-018-1267-8 (2018).

Zhang, M., Zhang, L., Riaz, M., Xia, H. & Jiang, C. Biochar amendment improved fruit quality and soil properties and microbial communities at different depths in citrus production. J. Clean. Prod. 292, 126062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126062 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Effects of Biochar addition on aeolian soil microbial community assembly and structure. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 3829–3845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-023-12519-y (2023).

Hou, Q. et al. Responses of nitrification and bacterial community in three size aggregates of paddy soil to both of initial fertility and Biochar addition. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 166, 104004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104004 (2021).

Yuan, M. et al. The addition of Biochar and nitrogen alters the microbial community and their cooccurrence network by affecting soil properties. Chemosphere 312, 137101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137101 (2023).

Ghorbani, M. & Amirahmadi, E. Insights into soil and biochar variations and their contribution to soil aggregate status – A meta-analysis. Soil Tillage. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2024.106282 (2024).

Ghorbani, M., Amirahmadi, E., Bernas, J. & Konvalina, P. Testing Biochar’s ability to moderate extremely acidic soils in tea-growing areas. Agronomy https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14030533 (2024).

Wei, S., Song, J., Peng, P., Yu, C. & Li, K. Characterization of pyrolysis products in Biochar prepared at different temperatures. GEOCHIMICA 48, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.19700/j.0379-1726.2019.05.008 (2019).

Wang, N., Hou, Y., Peng, J., Dai, J. & Cai, C. Research progess on sorption of orgnic contaminants to Biochar. Environ. Chem. 31, 287–295 (2012).

Wu, Y., Zhang, G., Lai, X., Liu, H. & Yang, D. Effects of Biochar applications on bacterial diversity in fluvor-aquic soil of North China. J. Agro-Environment Sci. 33, 965–971. https://doi.org/10.11654/jaes.2014.05.020 (2014).

Gu, M. et al. Effects of organic fertilizers and Biochar on microorganism community characteristics in saline-alkali sandy soil of Xinjiang. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 32, 1392–1404. https://doi.org/10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2023.08.005 (2023).

Yan, W. et al. The mechanism of sesame resistance against Macrophomina phaseolina was revealed via a comparison of transcriptomes of resistant and susceptible sesame genotypes. BMC Plant. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-02927-5 (2021).

Redhead, S. A., Vilgalys, R., Moncalvo, J. M., Johnson, J. & Jr, J. S. H. Coprinus Pers and the disposition of coprinus species sensu Lato. Taxon 50, 203–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1224525 (2001).

Schafer, D. J. The genus Parasola in Britain including Parasola cuniculorum sp. nov. Field Mycol. 15, 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fldmyc.2014.06.004 (2014).

Hussain, S., Afshan, N. S., Ahmad, H., Khalid, A. N. & Niazi, A. R. Parasola malakandensis sp. Nov. (Psathyrellaceae; Basidiomycota) from Malakand. Pakistan Mycoscience. 58, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.myc.2016.09.002 (2017).

Szarkándi, J. G. et al. The genus Parasola: phylogeny and the description of three new species. Mycologia 109, 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2017.1386526 (2017).

Chen, A. et al. Alternaria mycotoxins: an overview of toxicity, metabolism, and analysis in food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 7817–7830. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03007 (2021).

Meena, M. et al. Alternaria toxins: potential virulence factors and genes related to pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01451 (2017).

Deng, J. et al. Control effect of Biochar on soil microorganism in land consolidation region. Acta Tabacaria Sinica. 24, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.16472/j.chinatobacco.2017.291 (2018).

Wang, G. et al. Application-rate-dependent effects of straw Biochar on control of phytophthora blight of Chilli pepper and soil properties. Acta Pedol. Sin. 54, 204–215. https://doi.org/10.11766/trxb201604140027 (2017).

Chen, J. Y. et al. The effect of manure-borne doxycycline combined with different types of oversized microplastic contamination layers on carbon and nitrogen metabolism in sandy loam. J. Hazard. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131612 (2023).

Tabassum, S., Wang, Y., Zhang, X. & Zhang, Z. Novel mass bio system (MBS) and its potential application in advanced treatment of coal gasification wastewater. RSC Adv. 5, 88692–88702. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra11506j (2015).

Okanya, P. et al. Pyrroloquinolines from Ohtaekwangia kribbensis (Bacteroidetes). J. Nat. Prod. 74, 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1021/np100625a (2011).

Yoon, J. H., Kang, S. J., Lee, S. Y., Lee, J. S. & Park, S. Ohtaekwangia Koreensis gen. Nov., sp. Nov. and Ohtaekwangia kribbensis sp. Nov., isolated from marine sand, deep-branching members of the phylum bacteroidetes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 1066–1072. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.025874-0 (2011).

Qian, Y. L. et al. Effects of grass-planting on soil bacterial community composition of Apple orchard in Longdong arid region. Chin. J. Ecol. 37, 3010–3017 (2018).

Hu, Y. et al. Integrated biological control of tobacco bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) and its effect on rhizosphere microbial community. J. Biosci. Med. 9, 124–142. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbm.2021.93012 (2021).

Thijs, S. et al. Potential for plant growth promotion by a consortium of stress-tolerant 2,4‐dinitrotoluene‐degrading bacteria: isolation and characterization of a military soil. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12111 (2014).

Susilowati, D. N., Sudiana, I. M., Mubarik, N. R. & Suwanto, A. Species and functional diversity of rhizobacteria of rice plant in the coastal soils Indonesia. Indonesian J. Agricultural Sci. 16, 39–50 (2015).

Rao, M. P. N., Xiao, M. & Li, W. J. Chapter 12 - Characterization of the Genus Sinomonas: From Taxonomy to Applications in New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering (eds Singh, B. P., Gupta, V. K. & Passari, A. K.) 179–190 (Elsevier, 2018).

Manikprabhu, D. et al. Sunlight mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles by a novel actinobacterium (Sinomonas mesophila MPKL 26) and its antimicrobial activity against multi drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Photochem. Photobiol B: Biol. 158, 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.01.018 (2016).

Lehmann, J. et al. Biochar effects on soil biota – A review. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 43, 1812–1836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.022 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The basic research and talent training special project of the Jiangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences of PR China (JXSNKYJCRC202213) and the China agricultural research system (CARS-14, Special oil crops) provided funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruiqing Wang: Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Validation; Fengjuan Lyu: Visualization, Investigation; Rujie Lyu: Original draft preparation, Data curation; Junhai He: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software; Lingen Wei: Supervision.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Lyu, F., Lyu, R. et al. Applying an appropriate rate of rice husk biochar improves the microbial community structure of rhizosphere soil in continuously cropped sesame. Sci Rep 15, 35115 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19129-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19129-w