Abstract

The clearance efficiency of allergen particles during nasal irrigation is a quantitative standard for evaluating the effectiveness of nasal irrigation. Due to the difficulty in obtaining various parameters in in vivo experiments, this study aims to establish a numerical model of the nasal cavity based on CT scan images of healthy adults. We chose four different levels of allergen particles, PM1, PM5, PM10, and PM25, as the subjects. A quantitative analysis was conducted to determine the clearance efficiency of the four levels of allergen particles by five different inlet flow rates of the irrigation solution. The results showed that the clearance efficiency of PM1 allergens was optimal at the inlet flow rate of 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent to 2.10 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\). In summary, selecting an appropriate flow rate is necessary to achieve the best clearance efficiency for different levels of allergen particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is an inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa. When an individual is exposed to allergens, various immune cells and cytokines become involved1, increasing the likelihood of allergic responses to occur2. Therefore, it is particularly important to reduce the accumulation of allergens in the nasal cavity and effectively remove them. Nasal irrigation is a commonly recommended method for treating allergic rhinitis, as outlined in primary treatment guidelines, and is widely applied in clinical practice3,4,5. As shown in Fig. 1, during nasal irrigation with the head in the anterior lateral position, the irrigation fluid enters the nasal cavity from one side, first filling the middle nasal meatus on the side where the fluid enters, then filling the lower nasal passage, and finally filling the upper nasal passage. A small portion of the irrigation fluid enters the nasopharynx, while the most irrigation fluid flows out through the nasal cavity on the discharge side. During the irrigation process, the irrigation fluid flushes out mucus, blood crusts, bacteria, and allergens from the nasal cavity, reducing the release of inflammatory factors6.

There is a lack of quantitative standards for evaluating irrigation effectiveness in existing literature. Dipak Gandhi et al.7 evaluated the effectiveness of nasal irrigation on sinusitis, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea based on patients’ subjective evaluations and doctors’ clinical judgments of symptoms. Wu et al.8 printed a three-dimensional model of the nasal cavity and used yogurt to simulate the environment of nasal mucus inside the nasal cavity. They compared the clearance rate of yogurt before and after irrigation. However, a single model can only evaluate the nasal irrigation effect of individual patients, and the experiment was cost-intensive and time-consuming. Therefore, by using Computational Fluid Dynamics to establish numerical modeling of individual nasal cavity, we can quantitatively study the flow state and distribution patterns of gas or liquid within the nasal cavity, which serves as the basis for customizing personalized nasal irrigation parameters.

With the development of Computational Fluid Dynamics, CFD has gradually been applied to the study of rhinology. CFD can simulate the movement state, physical characteristics, and interactions of fluids. As early as 1993, Elad D et al.9 began exploring the application of CFD technology to nasal airflow research. They used numerical simulation methods to analyze the airflow patterns in the human nasal cavity, laying the foundation for the application of CFD technology in nasal research. Salati et al.10 utilized the Volume of Fluid (VOF) model to quantitatively compare the effects of two different devices on nasal irrigation. They obtained the time-dependent changes in the water content ratio of water distribution within the nasal cavity. Our research team explored the effects of nasal cycles on nasal airflow11. We found nasal cycles cause alternating changes in nasal airway volume and resistance, resulting in differences in nasal cavity function between the congested side and the decongested side. This study uses CFD to perform the dynamic changes in the internal flow field of nasal cavity more efficiently and intuitively. We can quantitatively study the clearance rate of allergen particles during nasal irrigation, objectively evaluate the effectiveness of nasal irrigation, and provide a theoretical basis for selecting the optimal irrigation flow rate for effectively removing allergen particles.

Materials and methods

Nasal cavity model

The nasal cavity model was created based on high-resolution CT scan results from a healthy male volunteer. The volunteer had no nasal disease and was in good physical condition. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2023BZYLL1018). The volunteer has also given their informed consent to participate in this clinical study. All methods used in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The scanned CT image is a rough model of the nasal cavity, with a complex structure and an extremely uneven surface, containing numerous defects and holes, making it unsuitable for experimental research. Therefore this model has to be treated first. We imported the scanned CT images into the 3D reconstruction software Geomagic Studio 12.0 (https://sculptcad.com/geomagic-studio/) for processing, removing parts that did not affect the research results, repairing minor defects on the model surface, and generating a smooth, complete nasal cavity model. Finally, we imported the generated model into the ANSYS platform for numerical simulation.

Mesh generation

We used the “Mesh” section of ANSYS Fluent to perform mesh partitioning on the model. we utilized unstructured grids to solve flow problems with complex geometries. In this study the three-dimensional tetrahedral grid was selected. In this study, we divided the model into six groups with different numbers of grids. The grid nodes and grid numbers are shown in Table 1.

We evaluated the quality of six groups of grids. ANSYS’s “mesh” has four evaluation indicators for quality: Element quality, Aspect ratio, Skewness, and Orthogonality quality. The evaluation results are shown in Table 2:

According to our simulation results, we selected [Unit mass]\(\ge\) 0.75, [Aspect ratio \(] \le\) 2.1, [Skewness \(] \le\) 0.25 and [Orthogonal quality \(] \ge\) 0.75. As shown in Table 2, Group No.4, No.5, and No.6 all have good quality.

We performed irrelevance verification. We imported the divided grid into ANSYS Fluent, selected the VOF model, selected two phases of water and air, and set the inlet flow velocity as 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). We selected the coverage rate of water at the mid-nasal section at 0.1 s as the reference value, as shown in Table 3. We found that the water phase coverage tended to stabilize starting from Group No. 4 and showed no significant difference compared with Groups No. 5 and No. 6. Changes in adjacency group coverage rate reflect fluctuations in results after refining adjacent grids. When changes in adjacency group coverage rate are less than 2%, the results tend to stabilize, i.e., groups 4–5 and 5–6. The cumulative change rate gradually decreases and stabilizes as the grid becomes denser (e.g., the cumulative change from Group 4 to Group 6 fluctuates from 5.94 to 5.91%), indicating that the results are approaching the “grid-independent solution.” If the cumulative rate of change continues to increase (e.g., from Group 1 to Group 4), continue to refine the grid until the rate of change is less than the threshold (5%). When the cumulative change rate is less than the threshold, even if the number of grids can still be increased, the change in results is negligible, and grid refinement can be stopped at this point to save computing resources. Therefore, Group No. 4 was selected for subsequent experiments in this study.

Establishing numerical models

Selection of multiphase flow models

The nasal irrigation process involves two fluids, air and saline solution, and is therefore a multiphase flow problem. ANSYS Fluent offers three computational models for solving multiphase flow problems: the Mixture model12, the VOF model13, and the Eulerian model14.

Mixture models are used to simulate flow problems under different interphase coupling interactions. They are suitable for scenarios where the phases are thoroughly mixed and the interphase velocity slip is relatively small, or where there is significant interphase slip but it is not necessary to analyze the motion of each phase separately. This study involves the coupled action of water and air phases that cannot be uniformly mixed, so the Mixture model is not applicable. The VOF model is commonly used in fluid mechanics, primarily describing the interface between two or more fluids. The VOF model can maintain the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy of fluids, making it highly accurate and stable in simulation. The VOF model is suitable for complex free surface flow. This study involves nasal irrigation and the clearance of allergen particles, which are suitable for the VOF model. The Eulerian model is also suitable for complex multiphase flow scenarios where each phase needs to be treated as a continuous medium. Although the Eulerian model can theoretically handle multiphase interfaces, the interface deviation reaches 10%-15% under the same grid density, presenting the “blurred diffusion.” The Eulerian model requires a 20 million-level encrypted grid to approach the accuracy of the VOF model, at the cost of a threefold increase in computation time and a threefold increase in interface roughness.

We performed trial calculations using small data volumes for the VOF model and the Euler model, and found that the Eulerian model required excessive computation time. Therefore, we selected the VOF model, which has better computational speed.

The control equations for the solver are as follows:

Let the design calculation region be Ω, the region where fluid A is located be \({\Omega }^{A}\), and the region where fluid B is located be \({\Omega }^{B}\). First, define a function \(a\left( {\vec{x},t} \right)\):

For a flow field composed of two incompatible fluid groups, \(a\left( {\vec{x},t} \right)\) satisfies the characteristics of a Lagrangian fluid volume:

Among them, \(\vec{V}\left( {u,v} \right)\) is the velocity cloud map of the fluid, \({\Delta }V_{ij}\) is the volume of a single grid, and \(F_{ij}\) is defined as the integral of \(a\left( {\vec{x},t} \right)\) on each grid \(I_{ij}\):

Call it a VOF function, and it also satisfies:

It is called the VOF equation.

Selection of turbulence models

The model used in this study is the RANS model15. This model is based on the Reynolds-averaged method, which averages the transient turbulent pulsation terms over time and then establishes control equations for the average quantities. The RANS model includes numerous submodules: the most commonly used are the k-ω model16 and the k-ε model17.

The k-ω model describes turbulence based on two parameters: turbulent energy k and turbulent dissipation rate ω. The model is simple in form, easy to understand, and accurately reflects wall behavior. The k-ε model primarily describes turbulent structures by introducing the turbulent macroscopic physical quantities of kinetic energy k and dissipation rate ε. The k-ω model does not introduce nonlinear terms when dealing with flow behavior near walls. The k-ω model is only applicable to laminar flow between parallel walls and has certain limitations when modeling turbulent flow. Therefore, the standard k-ε model was selected in this paper.

Selection of discrete phase models

The selection of a discrete phase model (DPM)18 is related to the volume fraction of solid particles. Discrete phase models include the Lagrangian method and the Eulerian method19. The Lagrangian method ignores the interactions between particles and is suitable for solid particles with a volume fraction of less than 10% to 12%. The volume fraction of particulate matter in this study is far less than 10%. Therefore, the discrete phase flow model in this paper adopts the Lagrangian method, taking into account gravity and drag force. The following equation is the analytical expression of the force acting on the particles:

Among them, \(m_{p}\) is the mass of the particle; \(\vec{u}\) is the velocity of the continuous phase; \(\vec{u}_{p}\) is the velocity of the particle; \(\rho\) is the density of the continuous phase; \(\rho_{p}\) is the density of the particle; \(\tau_{\gamma }\) is the relaxation time of the particle.

Experimental verification

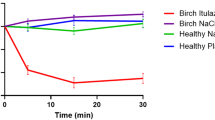

We validated the applicability of the model used by comparing nasal resistance measurement results with simulation results. The anterior nasal active pressure measurement method was used here. Before the measurement, the subjects sat quietly indoors for 20 min. Then, under room temperature conditions, nasal resistance was measured using a GM Instruments Ltd NR6 nasal resistance meter. The measurement lasted one minute, and the average pressure-flow correlation curve within one minute was obtained. Comparing the measurement results from the nasal resistance meter with the pressure drop-flow distribution obtained from CFD simulation, the two curves show consistent trends, as shown in Fig. 2. Therefore, the numerical model can be used to study the clearance rate of different allergen particles by nasal irrigation.

Deposition of allergen particles

When simulating the clearance rate of different allergen particles by nasal irrigation, we should first simulate the deposition of allergen particles in the nasal cavity.

Among the four levels of allergenic particles, PM1 was represented by cigarette particles; PM5 was represented by urban dust20; PM10 was represented by dust mite particles21 and PM10 was represented by pollen particles22. The pollen that causes allergies has a particle size of approximately 25 \(\mu \text{m}\), therefore we chose pollen as a representative of PM25. Based on pollen concentration standards and the human breathing rate per minute, the number of allergen particles in the nasal cavity was set at 91,600 as the initial condition.

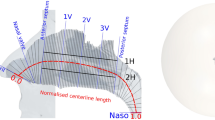

As shown in Fig. 3, the final results show the deposition of these four different allergen particles in the nasal cavity. Particles with smaller diameters have a higher deposition rate in the nasal cavity. In addition, we found that PM1 and PM5 allergen particles mainly deposit in the upper nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, while PM10 and PM25 allergen particles mainly deposit in the middle and lower nasal cavities.

Deposition of allergen particles. We used Geomagic Studio 12.0 (https://sculptcad.com/geomagic-studio/) to process the raw DICOM files obtained from CT scans and used the processed models to construct the nasal allergen deposition model.

Nasal irrigation parameters and solver settings

In our preliminary research, our team analyzed the nasal irrigation process for three different head positions, lateral position, supine position, and anterior lateral position23. The result has found that when subjects adopt lateral position, the irrigation fluid achieves high coverage in the nasal cavity and upper nasal cavity, and has a mild effect, making it recommended for children and teenagers. When using the supine position, the irrigation fluid covers a large area of the upper part of the nasal cavity on the inlet side, and it is difficult to drain from the nasal cavity on the outlet side. When using the anterior lateral position, the total coverage of the irrigation solution in the nasal cavity is high, and it is recommended for adults. Therefore, this study selected the anterior lateral position as the head position for nasal irrigation and investigated the flow process with five inlet flow rates of 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), and 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent to 1.17 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 1.40 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 1.75 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 2.10 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), and 2.33 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), respectively.

This study used a discrete phase model for calculations and set up interactions between particles and the continuous phase. The boundary conditions of the discrete phase model are shown in Table 4.

The nasal irrigation process involves three phases: gas, liquid, and solid. This study used both the Discrete Phase model and the VOF model. We set the liquid phase as water, the gas phase as air, and the solid phase as allergen particles.

In the simulation process, we set the wall surface as a rigid wall surface without slippage, set the outlet side nostrils and nasopharynx as pressure outlets, set the inlet side nostrils as velocity inlets, and lasting the flow time at 0.04 s. During nasal irrigation, the water flow is mainly affected by volume forces. Therefore, we used implicit volume forces to enhance the stability and convergence of the calculations. When performing multiphase flow calculations, the large time step causes the global Courant number to exceed 250, triggering floating-point overflow issues that prevent subsequent calculations from proceeding. Therefore, we set the time step to 10−5 s for subsequent calculations after optimization. We use the SIMPLE scheme to calculate pressure–velocity coupling, the grid-based least-squares gradient method for gradient discretization, Geo-Reconstruct for volume fraction discretization, the PRESTO! scheme for pressure discretization, and a second-order upwind scheme for momentum equation discretization.

Campos et al.24 compared and evaluated 26 nasal irrigation devices with flow rates ranging from 3.9 to 27.2 \({\text{ml}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent from 0.2 to 1.4 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). They concluded that a flow rate of 5 \({\text{ml}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent 0.3 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), is the minimum effective flow rate for nasal irrigation. Inthavong K et al. 25 reported that a nasal irrigation device can provide a flow rate of 1.79 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). Therefore, we analyzed flow rates in the range of 1.0–2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent from 1.17 to 2.33 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\).

Calculation of clearance rate

We introduced clearance rate (R) to quantitatively describe the deposition and escape of allergen particles in the nasal cavity. Its expression is as follows:

whereas \(N_{0}\) is the original number of allergen particles deposited, and \(N_{1}\) is the number of allergen particles remaining in the nasal cavity after nasal irrigation.

Results

Comparison of coverage rates at five different inlet flow rates

We analyzed the differences in the coverage of the irrigation fluid in the nasal cavity under five inlet flow rates in the range of 0–0.5 s, as shown in Fig. 4. We found that as the inlet flow rate increased, the coverage of the flushing fluid also increased. The inlet flow rate is proportional to the coverage rate. Under different flow rate, the trend of coverage is identical. In the range of 0–0.1 s, the coverage rate increases rapidly. In the range of 0.1–0.5 s, the coverage rate increases slowly. The trend of the coverage rate is gradually leveling off. At 0.5 s, the coverage rates were 49.16%, 58.94%, 61.56%, 64.74%, and 67.67%, corresponding to inlet flow rates of 1 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), and 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent to 1.17 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 1.40 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 1.75 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), 2.10 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), and 2.33 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\), respectively.

Particle clearance rate

When the allergen particles were PM1, the clearance rates of the allergen particles at the five flow rates are shown in Fig. 5. We found that the clearance rate of allergenic particles increases with increasing irrigation time, but the increase of the clearance rate slowed down gradually. At 0.5 s, the highest clearance rate by the flushing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) was 81.4%, followed by 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), which was 79.1%. The clearance rate is slightly lower at 75.4% by the flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). The clearance rates are relatively low at 67.7% and 68.6%, corresponding to the flow rates of 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), respectively. We found that the lowest flow rate at 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) did not result in the lowest clearance rate with 68.6%.

When the allergen particles were PM5, the clearance rates of the allergen particles at the five flow rates are shown in Fig. 6. We found that the clearance rate of allergenic particles of PM5 was similar to that of allergenic particles of PM1. At 0.5 s, the highest clearance rate by the flushing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) was 86.7%, followed by 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), which was 84.8%. The clearance rate is slightly lower at 79.7% by the flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). The clearance rates are relatively low at 76.9% and 77.6%, corresponding to the flow rates of 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), respectively.

When the allergen particles were PM10, the clearance rates of the allergen particles at the five flow rates are shown in Fig. 7. At 0.5 s, the highest clearance rate by the flushing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) was 83.9%, followed by 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), which was 82.2%. The clearance rates are relatively low at 79.8% and 79.4%, corresponding to the flow rates of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), respectively. The lowest clearance rate by the flushing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) was 77.5%.

When the allergen particles were PM25, the clearance rates of the allergen particles at the five flow rates are shown in Fig. 8. At 0.5 s, the clearance rates of allergen particles by flushing fluid with inlet flow rates of 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) are both relatively high and similar, at 88.5% and 89.2%, respectively. The clearance rate by the flushing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) is moderate, at 85.7%. The clearance rates are relatively low at 81.0% and 80.6%, corresponding to the flow rates of 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), respectively. In this allergen environment, the highest nasal irrigation flow rate did not result in the highest allergen particle clearance rate.

Distribution of residual allergens in the nasal cavity

We also analyzed the distribution of four types of allergen particles in the nasal cavity.

As shown in Fig. 9, when we rinsed the nasal cavity with the flushing fluid at the inlet flow rate of 1.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) lasting 0.5 s, the residual allergens were mainly distributed in the dorsal meatus area of the right nasal cavity and the lateral area of the inferior nasal meatus. Allergens were also found in all areas of the left nasal cavity.

As shown in Fig. 10, when we rinsed the nasal cavity with the flushing fluid at the inlet flow rate of 1.2 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) lasting 0.5 s, the residual allergens were mainly distributed in the dorsal meatus area of the right nasal cavity and the lateral area of the inferior nasal meatus. Allergens were retained in the left nasal cavity except for the inferior nasal meatus.

As shown in Fig. 11, when we rinsed the nasal cavity with the rinsing fluid at the inlet flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) lasting 0.5 s, the residual allergens were mainly distributed in the dorsal meatus of the right nasal cavity and the inner area of the left nasal cavity.

As shown in Fig. 12, when we used the rinsing fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) to rinse the nasal cavity lasting 0.5 s, the distribution of residual allergens was similar to that at 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), but the number of allergens was lower.

As shown in Fig. 13, when we rinsed the nasal cavity with the flushing fluid at the inlet flow rate of 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) lasting 0.5 s, the residual allergens were mainly distributed in the middle nasal meatus and inferior nasal meatus on the right side of the nasal cavity and the inferior nasal meatus on the left side of the nasal cavity.

As shown in Fig. 14, nasal irrigation fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and with the inlet flow rate of 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) have similar coverage ranges. However, the flow rate of nasal irrigation fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) in the middle nasal meatus and inferior nasal meatus is lower than that of nasal irrigation fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\). As shown in Fig. 15, we found that the flow rate affected the coverage range of the nasal cavity. Nasal irrigation fluid with the inlet flow rate of 1.8 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) can cover a wider range of the nasal cavity. The higher the flow rate passing through the nasal cavity is, the higher the clearance rate of allergen particles is.

Discussion

An important indicator for evaluating the effectiveness of nasal irrigation is the quantitative study of the clearance rate of allergenic particles. To solve this problem, we need to conduct an in-depth analysis of the complex multiphase flow dynamics involving particles, air, and water. This study established a relatively accurate model of the normal human nasal cavity for use in subsequent research. Our team conducted preliminary research comparing and analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of three different head positions during nasal irrigation: lateral position, supine position, and anterior lateral position. In this study, we selected the anterior lateral position as the head position for nasal irrigation.

We innovatively introduced allergen particles as a solid phase and constructed a high-precision three-phase flow numerical model of gas, liquid, and solid phases for nasal irrigation. We simulated the deposition and deposition distribution of four different allergen particles, PM1, PM5, PM10 and PM20, in the nasal cavity. We also revealed the clearance rates of four representative allergen particles with five different inlet flow rates, and accurately mapped the distribution of allergens remaining in the nasal cavity after rinsing, providing a rich theoretical basis for further optimizing the selection of nasal irrigation flow rates. This study simulated each flow rate condition three times, and the standard deviation of the clearance rate was less than 5%, indicating that the results have good repeatability. By comparing the clearance rates of four allergen particles using rinsing fluid at different flow rates, we can use the study results to assist in the clinical treatment of nasal allergic reactions. When dealing with allergic reactions caused by different allergen particles, we adjust the rinsing equipment based on the patient’s condition and select personalized rinsing speeds and methods to achieve optimal rinsing efficiency and precise rinsing of specific areas of the nasal cavity.

We found that PM1 and PM5 are more easily captured by the nasal mucosa and therefore mainly deposited in the dorsal meatus and paranasal sinuses. PM10 and PM25 mainly settle in the middle nasal meatus and Inferior nasal meatus. When studying the effect of different inlet flow rates on the clearance rate of allergen particles, we also found that increasing the flow rate can improve the clearance rate of allergen particles, but the improvement is relatively limited. It indicated that increasing the flow rate is not effective in clearance rate of PM10 and PM20.

However, it is worth noting that when we increased the inlet flow rate from 1.8 to 2.0 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), equivalent to an increase from 2.10 to 2.33 \({\text{L}}/{\text{min}}\) the clearance rate did not continue to increase, but decreased from 89.2 to 88.5% slightly instead. We speculate that there are two reasons for this phenomenon. On the one hand, high flow rates tend to generate eddies and turbulence in the nasal cavity. These complex fluid movements slow down the effective forward speed of the liquid, thereby reducing the clearance rate. When the inlet flow rate is close to 1.5 \({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), the volume fraction of the liquid is sufficient to cover most of the area where allergenic particles are deposited. If the flow rate is increased further, the liquid may overflow or bypass the deposition site due to excessive flow velocity, preventing additional contact with the particles and resulting in no further improvement in removal efficiency. On the other hand, the model assumes that the nasal wall is a smooth surface and does not take into account the actual mucous layer covering it. The viscosity and adsorption properties of mucus affect particle deposition behavior, and the interaction between the mucus layer and the rinsing fluid at high flow rates may alter particle clearance rates. DPM has not simulated the collision of allergen particles, and particle collisions at high flow rates may cause an increase in particle size, making them more likely to settle in the nasal meatus rather than on the mucous membranes. Furthermore, real allergen particles are hygroscopic or deformable, and liquid–solid interactions at high flow rates cause the particles to expand or deform, affecting their adhesion to the mucosa. However, the model treats the particles as rigid spheres, ignoring this characteristic. At the same time, we should also consider that using the irrigation fluid with an excessively high flow rate may cause damage to the inner wall of the nasal cavity, causing discomfort to the patient.

Conclusion

This study aimed to quantify the clearance rate of nasal allergen particles and investigated the effect of flow rate on the effectiveness of nasal irrigation. By comparing the clearance rates of allergen particles at five different flow rates, the results showed when the inlet flow rate was set to 1.8\({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), the clearance efficiency for PM1 and PM5 was the best. When the inlet flow rate is set as 1.5\({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\) and 1.8\({\text{m}}/{\text{s}}\), the clearance efficiency for PM10 and PM25 was optimal.

Nasal irrigation has become an important non-pharmacological method for treating allergic rhinitis and other nasal diseases. Research on nasal irrigation has limitations in terms of the depth of mechanism interpretation, standardization of efficacy assessment, and device universality. With the cross-application of computer technology, artificial intelligence, and materials science, nasal irrigation is rapidly developing in the direction of precision, intelligence, and personalization. In the future, with the deep integration of CFD and clinical practice, nasal irrigation is expected to become a core strategy in the comprehensive management of allergic diseases, providing global allergy patients with more efficient and sustainable adjunctive treatment options, and demonstrating significant medical value and social application potential.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhao, L. et al. Comparison of clinical research trends and hotspots in allergic rhinitis and asthma from 2013 to 2023 based on bibliometric analysis. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32829 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Short-term association of fine particulate matter and its constituents with oxidative stress, symptoms and quality of life in patients with allergic rhinitis: A panel study. Environ Int https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108319 (2023).

Park, D.-Y. et al. KAAACI allergic rhinitis guidelines: Part 2. Update in non-pharmacological management. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2023.15.2.145 (2023).

Kornmann, J., Kramer, B. & Haeussler, D. Grundlagen der Allergologie für die HNO-Sprechstunde. Laryngorhinootologie 103, 529–541. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2073-9474 (2024).

Shin, J. J. et al. Executive summary of the clinical practice guideline on the surgical management of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 172, 1807–1832. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.1286 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Nasal irrigation for the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract infection by SARS-CoV-2: A narrative review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 18, S81–S91. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.19234 (2024).

Abdullah, B., Periasamy, C. & Ismail, R. Nasal irrigation as treatment in sinonasal symptoms relief: A review of its efficacy and clinical applications. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 71, 1718–1726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-017-1070-0 (2017).

Wu, D., Chang, F., Hong, J., Su, B. & Wei, Y. A novel irrigation device with superior nasal irrigation efficiency to the classic rinse bottle. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-022-00575-9 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. CT analysis of frontal recess air cell and fluid dynamics simulation of frontal sinus in people with different frontal sinus development after Draf1–3 surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 281, 2463–2475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08433-8 (2024).

Salati, H., Khamooshi, M., Fletcher, D. F. & Inthavong, K. Computational investigation of nasal surface coverage from squeeze bottle and Neti Pot saline irrigation flow. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107223 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. Numerical simulation of the influence of nasal cycle on nasal airflow. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63024-9 (2024).

Hejazian, M., Moraveji, M. K. & Beheshti, A. Comparative study of Euler and mixture models for turbulent flow of Al2O3 nanofluid inside a horizontal tube. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 52, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2014.01.022 (2014).

Paz, C., Eduardo, S., Jesús, V. & Cabarcos, A. Analysis of the volume of fluid (VOF) method for the simulation of the mucus clearance process with CFD. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 22, 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2019.1569637 (2019).

Yan, Y., Li, X. & Ito, K. Numerical investigation of indoor particulate contaminant transport using the Eulerian-Eulerian and Eulerian-Lagrangian two-phase flow models. Exp. Comput. Multiph. Flow 2, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42757-019-0016-z (2019).

Bozzi, S., Dominissini, D., Redaelli, A. & Passoni, G. The effect of turbulence modelling on the assessment of platelet activation. J. Biomechan. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110704 (2021).

Semenzin, C. S., Simpson, B., Gregory, S. D. & Tansley, G. Validated guidelines for simulating centrifugal blood pumps. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 12, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13239-021-00531-0 (2021).

Sun, Y., Hao, M. & Wang, Z. Topology optimization of turbulent flow cooling structures based on the k-ε model. Entropy https://doi.org/10.3390/e25091299 (2023).

Jin, Z., Guo, G., Yu, A., Qian, H. & Tong, Z. Comparative analysis of micrometer-sized particle deposition in the olfactory regions of adult and pediatric nasal cavities: a computational study. Pharmaceutics https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16060722 (2024).

Sadeghi, T., Fatehi, P. & Pakzad, L. Effect of nasal inhalation on drug particle deposition and size distribution in the upper airway: With soft mist inhalers. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 52, 1195–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03423-7 (2024).

Muhammad, H., Saadia, N., Richard, E. G. & Zahid, A. Phleum pratense-pollen adaptive variations and pollen microbiome investigation under different climatic regions and prospects of allergenicity. Int. J. Biometeorol. 68, 2227–2240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-024-02740-3 (2024).

Korotkevich, A. O. Inverse cascade spectrum of gravity waves in the presence of a condensate: A direct numerical simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.264002 (2023).

Zanganeh Kia, H., Choi, Y., Nelson, D., Park, J. & Pouyaei, A. Large eddy simulation of sneeze plumes and particles in a poorly ventilated outdoor air condition: A case study of the University of Houston main campus. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164694 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. Numerical simulation of nasal irrigation with three different head positions. Beijing Biomed. Eng. 43, 331–337 (2024).

Campos, J., Heppt, W. & Weber, R. Nasal douches for diseases of the nose and the paranasal sinuses—A comparative in vitro investigation. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 270, 2891–2899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-013-2398-z (2013).

Inthavong, K., Shang, Y., Wong, E. & Singh, N. Characterization of nasal irrigation flow from a squeeze bottle using computational fluid dynamics. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22476 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from High-level Construction Discipline of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (zyyzdxk-2023272) and Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2021A02704).

Funding

This study was supported by the High-level Construction Discipline of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (zyyzdxk-2023272) & Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2021A02704).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yc L. and X S. wrote the main manuscript text . Q Y. prepared all figures. W F. and J Z. examined the thesis data. R Z. and Zb Y. corrected the paper as a whole. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Sui, X., Yang, Q. et al. Flow rate selection depends on the size of allergen particles to achieve optimal nasal irrigation. Sci Rep 15, 37595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19162-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19162-9