Abstract

Programmable photonic circuits are versatile platforms that route light through multiple interference paths using reconfigurable optoelectronic elements to perform complex discrete linear operations. These circuits offer the potential for high-speed and low-power photonic information processing in various applications. The mainstream research on programmable photonics has focused on implementing linear operations on discrete signals encoded in the modal amplitudes of an array of spatially separated single-mode waveguides. However, many photonic device applications require simultaneous transformations in the space-frequency domain, where information is encoded in both the spatial modes of waveguides and their spectral content. Here, we experimentally demonstrate linear space-frequency transformations using a four-port programmable silicon photonic circuit with an alternating architecture. This design leverages the limited dispersion of coupled waveguide arrays to enable linear operations with reconfigurable frequency-dependent matrix elements. We utilize this device to perform wavelength demultiplexing and filtering. This architecture platform can pave the way for versatile devices with applications ranging from wavelength routing to programmable dispersion control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exploration of optical phenomena for computational tasks has been a research-intensive and evolving field, tracing back to free-space solutions based on lens arrays for performing Fourier transforms1 and progressing to the realization of unitary operations using beam splitters and mirrors2. Although the scalability of early implementations was limited due to bulky and vibration-sensitive elements, these efforts paved the way for more compact and efficient solutions. Rapid advances in nanotechnology over the past few decades3 have enabled the fabrication of optical structures that are, in turn, capable of performing complex mathematical operations by exploiting the fundamental properties of light propagation4,5,6. In this regard, on-chip programmable photonic linear transforms are of particular interest, as they create new opportunities in quantum information and quantum transport simulations7,8,9, optical signal processing10, neuromorphic computing11, optical neural networks12,13,14,15,16, and enable rapid prototyping of linear multiport photonic devices17,18,19.

Numerous techniques have been investigated in the literature to realize unitary linear transformations within compact on-chip photonic circuits. These include photonic architectures employing networks of Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZIs), such as the rectangular Clements mesh20, the diamond mesh21, and other configurations22. Topological photonic lattices featuring hexagonal MZI arrays provide another alternative approach23,24. Recent research has explored interleaved architectures that combine passive transfer matrices with tunable active phase layers25,26,27,28,29,30, where the active layer is implemented through tunable phase elements. A particular approach utilizes multimode slab waveguides to perform discrete Fourier transforms (DFT), achieving universal transformations when a sufficient number of layers are incorporated28. Metasurface-based structures have also emerged as another promising avenue for optical computing, enabling computational functionalities for large-scale31 and component-level devices through inverse-design approaches32,33. Alternative devices exploit the polarization degrees of freedom in multilayer structures34, whereas solutions utilizing multiple frequencies have been explored by embedding resonators35.

Recent studies have found rigorous numerical evidence that interleaved phase arrays and discrete fractional Fourier transform (DFrFT) layers render universal N-dimensional unitary transforms with only \(N+1\) phase array layers29. A further generalization using Haar random unitaries as the interlacing layer has yielded the desired universality as long as the passive layer satisfies a density criterion30. In our earlier work, we proved that the interlacing architectures are robust to fabrication defects and exhibit auto-calibrating properties36. Extensions to non-unitary optical computing have emerged as a natural application; this includes approaches that leverages the singular value decomposition in networks of MZIs37,38, interlaced structures incorporating amplitude modulation layers39, and by embedding lower-dimensional matrices in higher-dimensional optical linear transformers40.

This work introduces a programmable photonic integrated circuit (PIC) with enhanced capabilities to operate in the wavelength domain. The PIC design consists of \(4\times 4\) passive layers created using dispersive coupled waveguide arrays, along with active layers featuring phase shifters. Although individual waveguide arrays exhibit a low dispersive response, their combined effect yields a richer wavelength response. Phase shifters allow for parameterization of the transmission matrix, the components of which are trainable and wavelength-dependent. The device is fabricated as a four-port system on a silicon-on-insulator platform, integrating thermo-optic microheaters for active phase control and optimized to operate within the C-band. The fabricated chip is both optically and electrically packaged, interfacing with optical and electrical control units that are operated through a computer-assisted framework for real-time configuration. Unlike passive solutions for unitary control, such as inverse-designed units, the proposed device enables on-the-fly programming, allowing for corrections due to fabrication defects. The device supports space-frequency operations, which are enhanced through an in-situ training approach that employs optimization algorithms, such as gradient descent, hill climbing, and simulated annealing to evaluate the convergence of various target functions for both single and multiple wavelength operations.

Results

Theory and architecture design

The proposed PIC is mathematically represented by a parameterized unitary matrix \(\mathcal {U}({\Phi }) \in U(N)\), where \({\Phi }\) denotes a set of tunable parameters used to induce optical interference and steer light to the desired output distribution. The unitary nature of the architecture is particularly suitable for implementation in optical systems governed by coupled-mode theory, rendering a lossless device. In such systems, guided modes propagate through evanescently coupled dielectric waveguides41,42. In this context, for single-mode waveguides, the electric field of an excitation propagating through the waveguide array along the z-direction can be expressed as \(E(x,y,z)=\sum _{n=1}^{N}\mathcal {E}(x,y-y_{n})a_{p}(z)\), where \(\mathcal {E}(x,y-y_{n})\) is the unit-power normalized electric field of the guided-mode, and \(a_{p}(z)\in \mathbb {C}\) denotes the corresponding complex-valued mode amplitude of the p-th waveguide. The mode amplitudes govern the dynamics of the electric field in the structure, defined through the equation \(id{\bf{a}}(z)/dz=H{\bf{a}}\), with \(\textbf{a}(z):=(a_{1}(z),\ldots , a_{N}(z))^{T}\) and \(H\in \mathbb {C}^{N\times N}\) a tridiagonal tight-binding Hamiltonian that dictates the coupling among waveguides41. For the structures under consideration, all waveguides in the coupler are identical, while the spacing between adjacent waveguides is varied to induce the desired propagation. This configuration results in a Hermitian Hamiltonian H with matrix components defined as \(H_{n,m} := \kappa _{n+1}\delta _{n+1,m} + \kappa _{n}\delta _{n-1,m}\), where \(\kappa _{n}\) represents the coupling parameter between the n-th and \((n+1)\)-th waveguides for \(n \in \{1,\ldots ,N-1\}\). Although the waveguides are parallel, they are not necessarily equally spaced; thus, the coupling parameters and the Hamiltonian remain independent of the propagation distance z. This allows for a straightforward unitary evolution of the mode amplitudes, described by the equation \(\textbf{a}(z) = F(z)\textbf{a}(z=0)\), where \(F(z) \equiv F = e^{-izH}\). The evolution of the mode amplitudes highlights the unitary matrix-vector operation performed by the waveguide array on an initial excitation \(\textbf{a}(z=0)\), which is the cornerstone principle exploited throughout the rest of the manuscript.

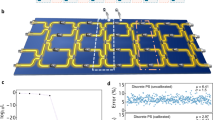

Reconfigurable programmable PIC design. (a) Block diagram of the proposed \(4\times 4\) unitary and programmable device. This design features low-dispersive mixing layers that work together to create a richer dispersive response. (b) Schematic representation of the proposed PIC, illustrating the dispersive waveguide arrays (passive units) and the phase shifters (active units) utilized in the interlacing structure. (c) Image of the as-fabricated packaged chiplet on the PCB assembly with optical fiber array and electrical wiring. (d) Image of the fabricated PIC. Lines starting near the bottom are the electrical traces connecting the metal heaters. (e) SEM micrograph of a zoomed-in view of the four-port waveguide array section. (f-i) Electromagnetic wave simulations of the proposed PIC at the central wavelength of 1550 nm. The phase elements have been simulated by changing the effective index of the waveguide arms to introduce desired phase changes. The phases were tuned to achieve the permutation \(\sigma (4,3,2,1)\) (cross routing), which routes light from input to output as \(1\rightarrow 4\) (f), \(3\rightarrow 2\) (g), \(2\rightarrow 3\) (h), and \(4\rightarrow 1\) (i). The simulations were conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics43.

The proposed device comprises four input and output ports, designed to perform space-frequency transformations on optical signals fed into the device inputs. The design is based on an interlacing structure29,36, which exploits the unitary nature of dispersive waveguide arrays F (passive layers), yielding wavelength-dependent light mixing across the different waveguides. Indeed, dispersion on such structures is known to be limited, with a linear and approximately flat wavelength response. However, the combined action of all these couplers in series induces richer behavior, allowing for wavelength-dependent tunability. See the Dispersive model section for details. The structure is completed by interspersed phase shifters \(e^{i\Phi ^{(k)}}\) (active layers), operating as the tunable elements in the structure and rendering a programmable device. The proposed design is summarized in the block diagram shown in Fig. 1a, which renders a wave evolution described by the unitary propagator

where each \(\Phi ^{(k)} = \operatorname {diag}(\phi _{1}^{(k)}, \ldots , \phi _{N}^{(k)})\) is a diagonal matrix representing a tunable phase-shifters in the k-th layer, and \(F \in U(N)\) is a fixed unitary matrix characterizing the waveguide array. We consider a four-port photonic processor with \(M=5\) layers of active elements, with each layer comprising \(N=4\) tunable phase shifters. Each phase shifter is controlled by the parameter \(\phi ^{(m)}_{n}\in (0,2\pi )\), representing the n-th applied phase in the m-th layer, leading to 20 active parameters. The corresponding universality has been numerically assessed for different classes of unitary couplers30.

Of particular interest is the group of permutation matrices \(S=\{P_{\sigma _{n}}\}_{n=1}^{N!}\) which serve as classic examples of sparse unitary matrices. In the context of photonic circuits, such permutations describe light routing from a single input to a unique output. For \(N=4\), we define the permutation operation through the rule

where \(\sigma _{n}\in \{1,2,3,4\}\) for \(n\in \{1,2,3,4\}\). The corresponding permutation matrix \(P_{\sigma }\) is constructed so that its first column has a ’1’ in the \(\sigma _1\)-th position and ’0’s elsewhere. Similarly, the second column contains a ’1’ in the \(\sigma _2\)-th position, and this pattern continues for each subsequent column. In this notation, the identity permutation is \(\sigma _{1}=(1\,2\,3\,4)\) and its matrix representation is the \(4\times 4\) identity matrix \(P_{\sigma _{1}}=\mathbb {I}\).

One of the most relevant aspects of the interlaced structure in Eq. (1) is its tolerance to defects caused by variations in the passive coupler. In experimental settings, achieving the ideal transfer function for F is often constrained by fabrication limitations. However, the proposed design has demonstrated robustness against these defects36. Although the transfer matrix of the fabricated coupler \(F_{\delta }\) may deviate from the ideal matrix F, it is possible to compensate for these defects by adjusting the phase shifters until the desired outcome is reached. This robustness stems from the flexibility in choosing F. In principle, any unitary matrix can be utilized as long as it meets the required density criterion30. These results are the basis for the choice of the current design. The PIC is intended to be trained in real-time, allowing it to address any defects on the fly. Such defects may include fabrication errors, thermal crosstalk between the phase shifters and couplers, or thermal crosstalk occurring among the phase shifters themselves.

PIC layout design and fabrication

The current device is fabricated according to the interlacing structure depicted in Fig. 1b. The passive layers are formed by identical waveguide arrays, the geometries of which are chosen to support a unique guided mode through each waveguide. This is achieved by fabricating the waveguides on a silicon-on-silica platform, which comprises a silicon (Si) core material with cross-sectional dimensions of 500 nm x 220 nm, buried in a silica cladding. The high-contrast refractive index ensures that a single mode is supported in this geometry for an operational wavelength of 1550 nm, thus minimizing artifacts due to mode crosstalk. The waveguide array is designed, simulated, and optimized by determining the optimal separation between neighboring waveguides and the coupling length that yields maximum mixing. That is, the transfer matrix of the coupler fulfills the density requirement, a property that theoretically ensures universality on the proposed PIC30. The transfer matrix of the fabricated sample does not need to precisely match the predicted one, since deviations due to manufacturing defects can be compensated by recalibrating the tunable phase elements36.

In turn, the active layer incorporates electrically tunable phase shifters that serve as training parameters in the in-situ training operations. Metal alloy microheaters implement a thermo-optical effect44,45, allowing a phase shift of at least \(\pi\). To prevent thermal crosstalk, thereby ensuring isolation between neighboring waveguide modes, the microheaters are strategically placed within the extended waveguide layer. The chip includes six waveguide arrays and five phase layers, rendering a total of 20 microheater elements, of which only 17 are functional due to broken wiring on three pads on the PCB board during handling in our lab. As shown in previous works36, this design is resilient to manufacturing defects; therefore, the broken metal heaters should not significantly impact device performance. See the experimental setup section below for more information.

Since our solution follows a simple design compatible with open-access foundries, the entire PIC layout was designed according to the previous prescriptions and submitted for fabrication to Applied Nanotools Inc. (ANT) using their silicon-on-insulator (SOI) technology Multi-Project Wafer (MPW) run. The fabricated chip was optically and electrically packaged by ANT, where the optical packaging included coupling and bonding of V-groove fiber arrays featuring an 8-degree polish angle and 250 \(\mathrm {\mu m}\) pitch. In turn, electrical packaging was accomplished by wire bonding to the electrical pads on a PCB. The packaged PCB is shown in Fig. 1c, a close-up of the PIC is shown in Fig. 1d, and an SEM micrograph of the coupling region in the coupled waveguide arrays is depicted in Fig. 1e.

Before manufacturing the device, we validate the layout design and its functionality through electromagnetic wave simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics. An individual waveguide array was initially simulated and characterized to ensure it produced sufficient mixing throughout all the waveguides. This waveguide array was then replicated and interconnected with the rest of the PIC using adiabatically bent waveguides. Additionally, circular bends with a radius of 15 \(\upmu\)m were employed to route light to the phase shifter section. The phase elements were simulated by adjusting the effective refractive index of the horizontal arms of the waveguide to induce the desired phase shift. The phases were optimized to produce an anti-diagonal identity matrix, which corresponds to the permutation operation \(\sigma =(4\,3\,2\,1)\) so that light entering the excitation ports {1, 2, 3, 4} is redirected to the output ports {4, 3, 2, 1}, respectively. Simulation results for the cross configuration are presented in Fig. 1f-i. These results illustrate how light from a single excitation propagates through the structure and ultimately emerges at the desired output. It is important to note that, although some power is leaked to ports other than the intended output during routing operations, the transmittance in the desired routing output remains close to one. This is illustrated in the right inset of Fig. 1g, where the routing operation from port 3 to port 2 is intended. Here, a small amount of power is visibly routed to ports 3 and 4; however, a transmittance of 0.98 is recorded at port 2. For reference, the insets illustrate the mixing nature of the waveguide array at different stages in the structure.

Design scalability

Design rules and device scalability. (a) Sketch of the generalized N-port interlaced design showcasing the relevant components. (b) Dispersive waveguide array section incorporating the coupling region, routing Bézier arms of length \(L^{(\text {arm})}\) and width \(s^{(\text {arm})}\), and L-bends of length \(L^{(\text {bend})}\) and separation \(s^{(\text {MH})}\) for thermal isolation purposes. (c) Zoomed-in view illustrating the waveguide separation \(s_{p}\), for \(p\in \{1,\ldots ,N-1\}\), and the coupling length \(L^{(\text {WGA})}\). (d) Typical structure of a metal heater performing the phase control, with \(L^{(\text {MH})}\) the total length of the metal layer.

The scalability of the proposed design can be evaluated by establishing design rules for each relevant component in the circuit and generalizing these rules for an N-port device. Figure 2a illustrates a sketch of a generalized N-port PIC with \(N+1\) layers, which is the optimal number of layers needed to achieve universal unitaries30,36. In this context, the individual coupled waveguide arrays, as shown in Fig. 2b, are the components whose dimensions are primarily influenced when the number of ports N increases. Practical design rules for waveguide arrays have been discussed previously40, and here we outline the main rules. The device size in the direction perpendicular to the propagation axis (\(L_{y}^{(\text {DUT})}\)) is mainly ruled by the spacing (\(s^{\text {(MH)}}\)) between the metal heaters performing the phase control. Such spacing is required to reduce the effects of thermal crosstalk, which becomes the most significant contribution to the vertical length. Thus, the total vertical length of the device under test becomes \(L_{y}^{(\text {DUT})}:=(N-1)s^{(MH)}+NW_{\text {WG}}\approx (N-1)s^{(MH)}\), where the approximation holds since the spacing between heaters is much larger than the waveguide width \(W_{\text {WG}}\).

The length in the direction of propagation, denoted as \(L_{x}^{(\text {DUT})}\), is determined by the length of the waveguide array and the metal heaters, as illustrated in Fig. 2b-d. Specifically, the waveguide arrays are defined by the coupling length \(L^{\text {(core)}}\) and the values of the coupling parameters, which are related to the spacing between the waveguides, as shown in Fig. 2b-c. For illustrative purposes, we consider the \(J_x\) lattice. This lattice is characterized by the coupling parameters \(\kappa _{n}=\frac{\widetilde{\kappa }}{2}\sqrt{(N-n)n}\), with \(\widetilde{\kappa }\) being a scaling coupling factor. In the \(J_x\) lattice, \(\kappa _{n=\lfloor \frac{N}{2} \rfloor }\) represents the strongest coupling in the array, which can be approximated as \(\kappa _{p=\lfloor \frac{N}{2} \rfloor }\approx N\frac{\widetilde{\kappa }}{4}\). Furthermore, the coupling length for any arbitrary N can be expressed in terms of the coupling length \(L^{\text {(core)}}_{(N=2)}\) for \(N=2\) ports, which serves as a reference for estimating sizes for arbitrary N. By combining these two observations, we derive the relation \(L^{\text {(core)}}\approx \frac{N}{2}L_{(\text {N=2})}^{\text {(core)}}\).

The coupling waveguides are then routed using cubic Bézier curves with a length of \(L^{(\text {arm})}\) and a width of \(s^{(\text {arm})}\). The length and width are adjusted with increasing values of N to maintain a low curvature and minimize radiation losses. Typically, we fix the ratio \(\ell =L^{(\text {arm})}/s^{(\text {arm})}\ge 3\) and set the length \(L^{(\text {arm})}=\ell (\frac{N-1}{2})s^{(\text {arm})}\), as indicated in40. The arms of the waveguide array are connected to the rest of the circuit using L-shaped bends of length \(L^{(\text {bend})}\). This design allows the waveguides to spread out, creating space for the metal heaters and ensuring sufficient separation \(s^{(\text {MH})}\) between them to minimize thermal crosstalk. Each L-bend is created using circular bends of radius R, which for single-mode waveguides on the silicon-on-silica platform, should be greater than \(15\,\mu m\) to mitigate radiation losses. From the architecture sketch, we notice that \(L^{(\text {bend})}=(\lfloor N/2 \rfloor -1) s^{(\text {arm})}+2R\). Thus, the total horizontal length per waveguide array becomes \(L^{\text {(WGA)}}=L^{\text {(core)}}+2L^{\text {(arm)}}+2L^{\text {(bend)}}\), which, from our previous results, is proportional to N.

Lastly, the length of the metal heaters to achieve a full rotation is fixed as \(L^{(\text {MH})}\) across the architecture (Fig. 2d). Thus, the total length of the device in the direction of propagation becomes \(L^{(\text {DUT})}_{x}=(N+2)L^{(\text {WGA})}+(N+1)L^{(\text {MH})}\). This indicates that the total length scales quadratically with N, resulting in a device with a larger footprint in the direction of propagation.

Dispersive model

Dispersive coupled-mode model and simulations. (a) Fitted model (solid lines) and FDTD simulated (markers) model of the dispersive coupling factor \(\kappa (\lambda )\) for waveguides separated at different gaps. The dispersive model under consideration is \(\kappa (\lambda )=(\nu _0+\nu _1 \lambda )e^{-\eta s}\) with s the gap size and \(\{\nu _{0},\nu _{1},\eta \}\) fitted from the simulation results. The gray shaded area denotes the C-band region. These results were obtained for fully etched silicon-on-silica waveguides of dimensions 500 nm \(\times\) 220 nm. (b) Intensity transmission of the dispersive coupled waveguide array model (solid lines) and the corresponding simulated results (markers). (c) Wavelength response of the proposed interlaced architecture for \(M=5\) layers (fabricated sample), and larger number of layers \(M=10,15,20\). This showcases an increased dispersion with respect to the individual coupler in (b). These simulations were conducted using the MODE and FDTD solvers in Flexcompute Tidy3D46.

The device response characterized by the unitary operator \(\mathcal {U}(\Phi )\) in Eq. (1) can be extended into the wavelength domain, which is required to understand the dispersion response. The main contribution to the dispersion comes from the waveguide array, represented by the unitary matrix \(F(\lambda ):=e^{-i L H(\lambda )}\). In the latter, the Hamiltonian characterizing the coupled waveguide array acquires an explicit dependence on the wavelength. It is well known that waveguide coupling can be approximated as \(\kappa \approx \nu e^{-\eta s}\) when the waveguides have a minimum spacing \(s_{0}\)41. For the rectangular waveguides in the silicon-in-silica platform under consideration, this is typically achieved for \(s_{0}\gtrapprox\)200 nm. To incorporate the dispersion effects, a series of finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations was conducted on a system of two coupled waveguides by varying the wavelength in the domain \(\lambda \in (1500 \, \text {nm}, 1600 \, \text {nm})\) and sweeping different waveguide gaps in the interval \(s\in (200\,\text {nm}, 1000\,\text {nm})\). Based on the simulation results, we calculated the coupling parameters, which are illustrated as markers in Fig. 3a for four representative waveguide gaps. These simulation results were then fitted to a dispersive coupling model defined as \(\kappa (\lambda , s):= (\nu _{0} + \nu _{1}\lambda )e^{\eta s}\), shown as solid-lines in Fig. 3a. The fitting process resulted in an error of 8.13% in the C-band.

The next step is to build the waveguide array with the previous dispersion behavior. To this end, we define the Hamiltonian \(H(\lambda )\) of a N-port coupled waveguide array through the matrix components \(H_{n,m}(\lambda )=\kappa _{n+1}(\lambda )\delta _{m,n+1}+\kappa _{n}(\lambda )\delta _{m,n-1}\), where \(\kappa _{n}(\lambda )\) are pairwise dispersive couplings, with \(n\in \{1,\ldots ,N-1\}\). The latter are designed by fixing the corresponding spacing between couplers and targeting a specific behavior at a fixed wavelength; in this case, we use 1550 nm as the reference wavelength. In Fig. 3b, we present the wavelength response of our dispersive model and compare it with the results obtained from FDTD simulations of the equivalent structure. In the simulated structure, we have included routing arms to interconnect the coupling region with the input and output ports (see Fig. 2b). The latter adds an extra, yet unavoidable, coupling length to the architecture, which makes the device slightly deviate from the ideal transmission. Nevertheless, the routing arms were picked so that such effects can be mitigated as much as possible. Indeed, this is illustrated in Fig. 3b, where the FDTD simulated and model-predicted transmission components show a satisfactory agreement, making the fitted model suitable for dispersion analysis.

With a reliable model for studying dispersion in coupled waveguide arrays, we can extend our approach to develop the interlaced architecture. Here, we ignore any dispersion caused by the phase shifters, as any phase deviation can be adjusted by retuning the phase shifter. Consequently, we generalize the interlaced architecture presented in Eq. (1) to include M layers, with \(M=5\) being the case considered in this work. Specifically, we define \(U(\Phi ;\lambda ) = F(\lambda )e^{\Phi ^{(M)}} F(\lambda ) \ldots F(\lambda )e^{\Phi ^{(1)}}F(\lambda )\), where \(M \in \mathbb {Z}^{+}\). Since this structure includes active components that modify the behavior of the transmission matrix, we set all phase values to zero. This approach ensures that any dispersive behavior results solely from the interference and dispersion of the individual couplers. In Fig. 3c, we illustrate the wavelength dependence of \(U(\Phi ;\lambda )\) for \(M=5,10,15,20\) layers. This reveals a deviation from the flat response of the individual coupler to a full oscillatory response in the wavelength range (1500 nm, 1600 nm) for \(M=5\) layers. Fig. 3c shows that the more layers added to the device, the more oscillations are embedded into the wavelength response.

Experimental setup and in-situ training

To effectively characterize and train the fabricated chip in situ, we have developed an automated process that can be fully controlled through a computer and programmed using Python. Fig. 4a summarizes the workflow of the experimental setup used during the training. This setup features a continuous wave (CW) laser source (Santec TSL-570), which can be remotely adjusted within the range of 1500 nm to 1600 nm. An optical switch (Santec OSX-100) directs the laser output, allowing the signal to be steered to individual fibers in a lensed fiber array connected to the PIC. Each of these fibers connects to mechanical polarization controllers, which enable the coupling of the mode necessary for the PIC operation. A second lensed fiber array is coupled at the output of the PIC and is interconnected to a multiport optical power detector that measures the real-time output power of the PIC. The phase elements of the PIC are externally controlled using an electrical source measure unit (SMU). This unit (Nicslab XDAC) powers all the metal heaters in the PIC individually and simultaneously. For the current operation, the heaters were operated in a current-controlled mode, where each heater is individually adjusted between 0 mA and 10 mA. This adjustment ensures that each metal heater produces an effect equivalent to a complete phase rotation.

Since the PIC integrates TE-mode grating couplers, the mechanical polarization controllers are adjusted so that the total power at the PIC output is maximal. This ensures that the proper mode has been injected and minimizes coupling losses. This step is the only manual calibration required in the experimental setup. The CW laser, optical switch, optical detectors, and SMU all have APIs compatible with Python scripting for control via an external computer, allowing for remote and automated access to the PIC measurement and phase tuning processes.

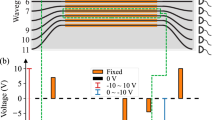

Experimental setup for in-situ training and wavelength-sweep measurements. (a) The measurement system consists of a CW laser source, an optical switch, an electrical source-measure unit (SMU) connected to the PIC to drive the electrical signals, and a power meter (optical detector) to gather the optical signals. Starting with an initial set of random currents, the PIC generates a set of optical signals that results in a transmission matrix. The figure of merit is then constructed in accordance with Eq. (2). The computer program automatically updates the currents and continues iterating until the figure of merit drops below a predefined threshold. (b) Figure of merit versus step for the target matrix shown in the lower-left inset. The transmission matrices obtained after various optimization methods are shown in the right insets. (c) Simulated wavelength response of the coupled waveguide array used as the dispersive mixing layer (\(F(\lambda )\)) in the device. (d) Experimental wavelength-sweep of the system optimized to perform the permutation \(\sigma =(2\,1\,4\,3)\) at the central wavelength of 1550 nm.

We developed an in-situ training approach to calibrate our device, allowing it to be steered toward the desired unitary intensity matrix in real-time. During the training process, we provide the intensity matrix as input, and the output generates the necessary currents to adjust the device to achieve this target. This process involves defining a figure of merit that needs to be minimized, taking into account the number of input and output ports, as well as the number of frequency points. The frequency points are discretely sampled around the C-band. Thus, given the target matrix \(T^{g}(\lambda )\in \mathbb {C}^{N_{1}\times N_{2}}\) and the measured matrix \(\mathcal {T}^{m}(\Phi ,\lambda )\), we define the figure of merit through the semi-positive definite function

where \(\Vert \cdot \Vert\) represents the Frobenius norm (\(L^2\) norm), and \(N_\lambda\) is the number of frequency channels. \(N_{1}\) and \(N_{2}\) are the number of rows and columns, respectively, of the target matrix. The measured matrix \(\mathcal {T}^{m}(\Phi ;\lambda )\) updates by manipulating the active parameter set \(\Phi\), which is tuned by the currents applied to the microheaters in the structure. In some configurations, the optimization is carried out by exciting only a single port and sweeping different wavelengths, resulting in \(N_{2}=1\) and \(N_{\lambda }>1\). For operations at a single frequency, we set \(N_{\lambda }=1\) and set \(N_{1}=N_{2}=4\) to characterize the transfer matrix of the device.

When addressing arbitrary targets, we expect numerous local minima in the optimization landscape defined by the figure of merit, making it challenging to reach the global minimum. The selection of optimization algorithms depends on the nature of the problem. In this case, we have utilized selective optimization techniques–such as gradient descent, hill climbing, and simulated annealing–each of which is effective and well-suited for fine-tuning the system to deterministically identify global minima and achieve convergence toward the target function. In each iteration of the algorithm under consideration, the current values of all heater elements are automatically adjusted to drive the figure of merit \(\mathcal {L}(\Phi )\) to a predefined threshold limit. In the class of programmable devices under investigation, the number of waveguide arrays and phase shifter layers is a crucial factor for conducting prompt convergence. Parameters for the various optimization algorithms include the initial applied currents, error-threshold limits, step sizes, and iteration boundaries.

In general, for all the optimization algorithms considered, we begin with a random initialization of currents across all phase shifters. The algorithm updates the set of currents based on a predefined step-size rule that varies depending on the chosen algorithm. The intensity of the transmission matrix is gathered from the photodectors, and the figure of merit is computed to determine if the optimization process has succeeded, should continue with the next step, or has failed. The success of the training is evaluated by verifying if the figure of merit falls below a predefined threshold.

The main distinction across all the algorithms lies in the way the steps are taken. For the hill climbing algorithm, the optimization code selects each thermo-optic phase shifter sequentially and makes small adjustments to the applied electrical current. Initially, the current is increased by a small amount, and the optical error is calculated. If the error decreases, the current is further increased until the error begins to rise again. Otherwise, the current is decreased until a stopping condition is met. Afterwards, a different thermo-optic phase shifter is chosen, and the current is adjusted following the same procedure. In the simulated annealing algorithm, all steps are randomized at first, changing the currents of all thermo-optic phase shifters simultaneously without considering the error. Gradually, for each step, a temperature parameter, which starts at a high value, is reduced, thereby decreasing the likelihood of making a move that increases the error. Eventually, as the temperature approaches zero, the algorithm only permits steps that decrease the error. For the gradient descent algorithm, the code cycles through each thermo-optic phase shifter but does not save any changes until data from all the currents of the phase shifters has been collected. This data forms a gradient vector. The learning rate is then applied to adjust the previous vector or currents towards a local optimum.

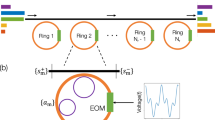

Port-selective wavelength demultiplexing. (a) Embedded 1x2 passthrough optimized for 1520 nm and 1580 nm through output 1, and not through output 2. (b) Embedded 1x2 demultiplexer optimized for 1530 nm through output 1 and 1570 nm through output 2. (c) Embedded bandpass filter optimized for 1550 nm through output 1, and 1540 and 1560 nm through output 2. (d) Embedded highpass filter optimized for 1530 nm through output 1, and 1540, 1550, 1560, and 1570 nm through output 2.

Figure 4b depicts the convergence rate by using the gradient descent, hill climbing, and simulated annealing algorithms for the permutation matrix 2143 as the target at the 1550 nm wavelength. Indeed, permutation matrices are prime examples of unitary sparse matrices, which are compatible with device capabilities. The experimentally measured normalized transmission is shown in the insets of Fig. 4b for all the optimization algorithms. Despite achieving similar accuracy across the different algorithms, the training history reveals a faster convergence rate with heuristic methods.

Although coupled waveguide arrays typically offer a linear wavelength response, the serial combination of them induces a richer wavelength dispersion. To illustrate this, Fig. 4c shows the simulated transmission matrix of the waveguide array used in the layout design. The latter is presented in dB scale and illustrates the lack of features in the dispersion, as is the case in typical ring resonators. In turn, the experimental wavelength response of the device was characterized and shown in Fig. 4d. In the latter, the device was programmed to perform the permutation \(\sigma (2\,1\,4\,3)\); that is, light from the sequence of input ports \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) is entirely routed to the output sequence \(\{2,1,4,3\}\). Indeed, these plots reveal a rich response that varies across different wavelengths, which corroborates the behavior predicted from our dispersive model and provides insight into the wavelength engineering of the device response.

Of particular interest is the wavelength demultiplexing and filtering operation in PICs, which enables the separation of optical signals carried over a single channel into discrete wavelength channels, each directed to a particular designated output port for parallel processing. The present device can indeed be operated to perform filtering operations. To this end, the continuous-wave laser used in the experimental setup is swept over a wavelength range of 1500 nm to 1600 nm, which excites a single input port. This effectively generates a transfer matrix for each wavelength, sampling \(N_{\lambda }\) wavelength points. The device is then trained to filter out up to five different wavelengths at the output ports one and two. This renders \(N_{2}=1\) (one column) and \(N_{1}=2\) (two rows) in the target matrices used in the figure of merit in Eq. (2). The following four demultiplexing configurations are used for training four different configurations as follows: (a) Optical signals at 1520 nm and 1580 nm are directed entirely to port one, with no power sent to port two (Fig. 5a). (b) Optical signals at 1530 nm are routed to port one, while those at 1570 nm are directed to port two (Fig. 5b). (c) Optical signals at 1540 nm and 1560 nm are routed to port two, while 1550 nm is steered to port one (Fig. 5c). (d) Optical signals at 1540 nm, 1550 nm, 1560 nm, and 1570 nm are routed to port two, while 1530 nm is steered to port one (Fig. 5d). The full wavelength sweep from 1500 nm to 1600 nm, along with the corresponding training history of the figure of merit, is shown in all cases. In the worst-performing scenario, the extinction ratio is above 10 dB, which highlights the effectiveness of the device for demultiplexing tasks.

Single-wavelength optimization for sparse matrix representation. Measured intensity transmission matrices for the complete set of 24 (4!) possible \(4\times 4\) permutation matrices. The device was programmed in-situ and operated at a central wavelength of 1550 nm. The label at the top of each panel indicates the specific permutation operation being performed.

For completeness, we performed a series of single-wavelength training sessions to assess the universality of unitary matrices at 1550 nm. During this process, we used the entire set of \(4 \times 4\) permutation matrices as our target matrices. We employed the gradient descent algorithm to train these sparse matrices, and the resulting transmission matrices are shown in Fig. 6. We successfully trained the phase shifters so that the experimentally trained transmission matrix accurately represented the \(4!= 24\) targets, despite the presence of three non-functional metal heaters. This resilience to faulty phase elements was discussed in previous studies36, which is a consequence of the device overparameterization, leading to an error-robust PIC.

Conclusion

We have successfully demonstrated a PIC capable of high-fidelity optical switching and multiwavelength demultiplexing. The device is programmed on-the-fly using in-situ optimization of integrated microheaters used for phase tuning, and driven by algorithms such as gradient descent, hill climbing, and simulated annealing. This approach achieves high accuracy and fast convergence, particularly for the sparse matrices crucial in optical routing applications. During the training, we noticed that hill climbing and simulated annealing algorithms typically reach convergence in shorter times compared to gradient descent. This is partly due to hardware limitations and also because the gradient descent algorithm requires the computation of gradient vectors at each iteration. This process involves measuring 17 additional transmission matrices in every iteration. Interestingly, although the device had three non-functional heaters, the training still converged successfully. This can be attributed to the over-parameterized nature of the PIC. Despite having three broken heaters, we still meet the minimum requirement of parameters (\(N^{2}\)) needed to achieve the unitary operation.

Thermal diffusion between neighboring microheaters can induce phase errors in adjacent elements and passive components, such as waveguide arrays. However, the strength of our approach lies in its use of in-situ optimization and the robustness of the design against manufacturing defects36. The optimization algorithms under consideration treat the PIC as a black box, iteratively updating the current until the desired target is achieved within the prescribed tolerance. Once a heater is powered, it adds the phase of its target waveguide and also slightly changes the temperature of its neighboring waveguides. However, these combined effects are captured in the measured optical output and, from an algorithmic perspective, such thermal crosstalk is viewed as a non-ideal characteristic of the physical system.

Our device serves as a proof of concept to showcase the range of operational tasks it can perform. Following the silicon-on-silica platform and the waveguide dimensions used in the current photonic integrated circuit (PIC), we can estimate the footprint of devices with additional ports. Based on our general scalability results and design rules, we can utilize waveguides with a curvature radius of \(R = 15\, \mathrm {\mu m}\), an arm spacing of \(s^{(\text {arm})} = 3.5\, \mathrm {\mu m}\), a Bézier ratio of \(\ell = 3.5\), microheaters with a length of \(L^{(\text {MH})} = 340 \, \mathrm {\mu m}\), and a spacing between microheaters of \(s^{(\text {MH})} = 70 \, \mathrm {\mu m}\) (refer to Fig. 2 for a visual reference). From the fitted model for \(\kappa (\lambda )\) at 1550 nm, and considering waveguide arrays with a minimum spacing of 220 nm, we calculate a coupling length of approximately \(L^{(\text {core})}_{N=2} \approx 21 \, \mu m\). These parameters allow us to estimate the footprint in terms of the number of ports while limiting the design area to a typical die size of 9 mm \(\times\) 9 mm. Under these constraints, we can accommodate a PIC with up to \(N = 10\) ports, resulting in an overall size of \(L_{x}^{(\text {DUT})} = 8090 \, \mathrm {\mu m}\) and \(L_{y}^{(\text {DUT})} = 630 \, \mathrm {\mu m}\). To enhance compactness further, we can implement deep trenches or phase shifter technologies that produce minimal excess heat. This could reduce the space required between phase elements in the layout, which currently comprises the largest footprint in the device.

In the fabricated sample, we chose microheaters as the active elements for phase control. Although these active components are known for their low switching speed, primarily limited by the thermal relaxation of the heaters, they are a simple and widely standardized solution in open-access foundries for fast prototyping. However, our design is versatile and can be adapted for use with other active components with a smaller footprint, like phase change materials47 (PCMs), or active components with a faster response, like doped nanoparticle silicon48 and direct metallization on ridge silicon waveguides49. Additionally, the design can be deployed in other material platforms that facilitate rapid phase modulation and better thermal isolation, such as lithium-niobate50.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goodman, J. W. Introduction to Fourier optics (Roberts and Company publishers, 2005).

Reck, M., Zeilinger, A., Bernstein, H. J. & Bertani, P. Experimental realization of any discrete unitary operator. Phys. review letters 73, 58. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.58 (1994).

Yang, Y. et al. Nanofabrication for nanophotonics. ACS nano https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.4c10964 (2025).

Joannopoulos, J. D., Villeneuve, P. R. & Fan, S. Photonic crystals: putting a new twist on light. Nature 386, 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1038/386143a0 (1997).

McMahon, P. L. The physics of optical computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-023-00645-5 (2023).

Yan, R., Gargas, D. & Yang, P. Nanowire photonics. Nat. photonics 3, 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2009.184 (2009).

Madsen, L. S. et al. Quantum computational advantage with a programmable photonic processor. Nature 606, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04725-x (2022).

Harris, N. C. et al. Quantum transport simulations in a programmable nanophotonic processor. Nat. Photonics 11, 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2017.95 (2017).

Slussarenko, S. & Pryde, G. J. Photonic quantum information processing: A concise review. Applied. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6, 10.1063/1.5115814 (2019).

Notaros, J. et al. Programmable dispersion on a photonic integrated circuit for classical and quantum applications. Opt. express 25, 21275–21285. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.021275 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. Neuromorphic computing based on wavelength-division multiplexing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 29, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2022.3203159 (2023).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. photonics 11, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2017.93 (2017).

Zhu, H. et al. Space-efficient optical computing with an integrated chip diffractive neural network. Nat. Commun. 13, 1044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28702-0 (2022).

Li, X.-K. et al. High-efficiency reinforcement learning with hybrid architecture photonic integrated circuit. Nat. Commun. 15, 1044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45305-z (2024).

Yang, X., Rahman, M. S. S., Bai, B., Li, J. & Ozcan, A. Complex-valued universal linear transformations and image encryption using spatially incoherent diffractive networks. Adv. Photonics Nexus 3, 016010–016010. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.APN.3.1.016010 (2024).

Zelaya, K., Honari-Latifpour, M. & Miri, M.-A. Integrated photonic programmable random matrix generator with minimal active components. npj Nanophotonics 2, 6, 10.1038/s44310-025-00054-9 (2025).

Tang, R. et al. Two-layer integrated photonic architectures with multiport photodetectors for high-fidelity and energy-efficient matrix multiplications. Opt. Express 30, 33940–33954. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.457258 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Parallel optical coherent dot-product architecture for large-scale matrix multiplication with compatibility for diverse phase shifters. Opt. Express 30, 42057–42068. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.471519 (2022).

Kondratyev, I. V. et al. Effective programming of a photonic processor with complex interferometric structure. arXiv:2508.15741 (2025).

Clements, W. R., Humphreys, P. C., Metcalf, B. J., Kolthammer, W. S. & Walmsley, I. A. Optimal design for universal multiport interferometers. Optica 3, 1460–1465. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.3.001460 (2016).

Shokraneh, F., Geoffroy-Gagnon, S. & Liboiron-Ladouceur, O. The diamond mesh, a phase-error-and loss-tolerant field-programmable mzi-based optical processor for optical neural networks. Opt. Express 28, 23495–23508. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.395441 (2020).

Mojaver, K. H. R., Zhao, B., Leung, E., Safaee, S. M. R. & Liboiron-Ladouceur, O. Addressing the programming challenges of practical interferometric mesh based optical processors. Opt. Express 31, 23851–23866. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.489493 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Topologically protected entangled photonic states. Nanophotonics 8, 1327–1335. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0058 (2019).

On, M. B. et al. Programmable integrated photonics for topological hamiltonians. Nat. Commun. 15, 629. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44939-3 (2024).

Tanomura, R., Tang, R., Ghosh, S., Tanemura, T. & Nakano, Y. Robust integrated optical unitary converter using multiport directional couplers. J. Light. Technol. 38, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2019.2943116 (2020).

Saygin, M. Y. et al. Robust architecture for programmable universal unitaries. Phys. review letters 124, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.010501 (2020).

Tanomura, R. et al. Scalable and robust photonic integrated unitary converter based on multiplane light conversion. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.17.024071 (2022).

Pastor, V. L., Lundeen, J. & Marquardt, F. Arbitrary optical wave evolution with fourier transforms and phase masks. Opt. Express 29, 38441–38450. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.432787 (2021).

Markowitz, M. & Miri, M.-A. Universal unitary photonic circuits by interlacing discrete fractional fourier transform and phase modulation. ArXiv:2307.07101 [physics.optics], 2023.

Zelaya, K., Markowitz, M. & Miri, M.-A. The goldilocks principle of learning unitaries by interlacing fixed operators with programmable phase shifters on a photonic chip. Sci. Reports 14, 10950. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60700-8 (2024).

Tzarouchis, D. C., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. Programmable wave-based analog computing machine: a metastructure that designs metastructures. Nat. Commun. 16, 908. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56019-1 (2025).

Piggott, A. Y., Petykiewicz, J., Su, L. & Vučković, J. Fabrication-constrained nanophotonic inverse design. Scientific reports 7, 1786 (2017).

Molesky, S. et al. Inverse design in nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 12, 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-018-0246-9 (2018).

Tanomura, R., Tanomura, T. & Nakano, Y. Multi-wavelength dual-polarization optical unitary processor using integrated multi-plane light converter. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 62, SC1029, 10.35848/1347-4065/acab70 (2023).

Buddhiraju, S., Dutt, A., Minkov, M., Williamson, I. A. & Fan, S. Arbitrary linear transformations for photons in the frequency synthetic dimension. Nat. communications 12, 2401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22670-7 (2021).

Markowitz, M., Zelaya, K. & Miri, M.-A. Auto-calibrating universal programmable photonic circuits: hardware error-correction and defect resilience. Opt. Express 31, 37673–37682. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.502226 (2023).

Miller, D. A. All linear optical devices are mode converters. Opt. Express 20, 23985–23993. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.20.023985 (2012).

Moralis-Pegios, M., Giamougiannis, G., Tsakyridis, A., Lazovsky, D. & Pleros, N. Perfect linear optics using silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 5468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49768-y (2024).

Markowitz, M., Zelaya, K. & Miri, M.-A. Learning arbitrary complex matrices by interlacing amplitude and phase masks with fixed unitary operations. Phys. Rev. A 110, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.033501 (2024).

Markowitz, M., Zelaya, K. & Miri, M.-A. Embedding matrices in programmable photonic networks with flexible depth and width. Opt. Lett. 50, 2318–2321. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.553436 (2025).

Yariv, A. & Yeh, P. Photonics: optical electronics in modern communications (Oxford university press, 2007).

Huang, W.-P. Coupled-mode theory for optical waveguides: an overview. JOSA A 11, 963–983. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.11.000963 (1994).

Comsol multiphysics®v.5.5; www.comsol.com, comsol ab, stockholm, sweden.

Parra, J., Navarro-Arenas, J. & Sanchis, P. Silicon thermo-optic phase shifters: a review of configurations and optimization strategies. Adv. Photonics Nexus 3, 044001–044001 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Thermo-optic phase shifters based on silicon-on-insulator platform: State-of-the-art and a review. Front. Optoelectronics 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12200-022-00012-9 (2022).

Tidy3d v.2.9; www.flexcompute.com/tidy3d; flexcompute.

Ríos, C. et al. Ultra-compact nonvolatile phase shifter based on electrically reprogrammable transparent phase change materials. PhotoniX 3, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43074-022-00070-4 (2022).

Harris, N. C. et al. Efficient, compact and low loss thermo-optic phase shifter in silicon. Opt. express 22, 10487–10493 (2014).

Chang, C., Li, T., Wu, Y., Zhou, P. & Zou, Y. Fast-response, energy-efficient thermo-optic silicon phase shifter based on non-hermitian engineering. In Optical Fiber Communication Conference, M3E–5 (Optica Publishing Group, 2022).

Maeder, A., Kaufmann, F., Pohl, D., Kellner, J. & Grange, R. High-bandwidth thermo-optic phase shifters for lithium niobate-on-insulator photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Lett. 47, 4375–4378 (2022).

Funding

This project is supported by the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) Award# FA9550-25-1-0200, the U.S. AFOSR Young Investigator Program (YIP) Award# FA9550-22-1-0189, by the Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP) Award# FA9550-23-1-0539, and by the National Science Foundation Award# CNS-2329021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F. carried out the experiment setup, in-situ training, and device characterization. K.Z. conducted the theoretical modeling, ran the wave simulations, and performed the numerical analysis. J.F. and K.Z. prepared the initial manuscript. M.H.-L. designed the PIC layout. M.-A.M. conceived the original idea and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Friedman, J., Zelaya, K., Honari-Latifpour, M. et al. Programmable space-frequency linear transformations in photonic interlacing architectures. Sci Rep 15, 35173 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19176-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19176-3