Abstract

Node classification tasks are predominantly tackled using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) due to their ability to capture complex node dependencies through message-passing. However, GNNs suffer from several limitations, including high computational costs, memory inefficiency, and the requirement for complete data including both training and test data to achieve robust generalization. These issues make GNNs less suitable for real-world applications and resource-constrained environments. In this work, we address these challenges by leveraging contrastive learning techniques within Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) to effectively capture both local and global graph structure information. Our proposed framework incorporates three contrastive learning strategies that enable MLPs to outperform GNNs in terms of classification accuracy, while also providing superior inference speed and lower memory consumption. Extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets demonstrate the efficacy of our approach, positioning it as a compelling alternative to traditional GNN-based methods for node classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Node classification is a fundamental task in graph-based machine learning, where the objective is to predict the labels of the nodes within a graph. This task has significant implications across various domains, including social network analysis,recommendation systems, biological networks, online vocational education, tourism demand forecasting, and knowledge graphs1. For instance, in social networks, node classification can be used to infer user attributes such as interests or political affiliations based on their connections and interactions2. Similarly, in recommendation systems, it enables the prediction of user preferences or item categories, facilitating personalized recommendations3. In biological networks, node classification aids in identifying functional roles of proteins or genes, thereby contributing to advancements in disease diagnosis and drug discovery4. In vocational education networks, node classification helps identify learners’ competency levels and course suitability, thereby enabling personalized learning paths and targeted skill development5. In tourism demand networks, node classification enables the categorization of cities by visitor demand levels, thereby supporting resource allocation and strategic planning for destination management6. The ability to accurately classify nodes is crucial for leveraging graph-structured data in diverse applications, making it a vital research area of both theoretical and practical importance.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as the dominant approach for node classification tasks due to their ability to effectively capture node dependencies and structural information1. GNNs leverage a message-passing mechanism, where each node iteratively aggregates information from its neighbors to learn a rich and expressive representation7. Based on how message-passing be used, GNNs can be broadly categorized into two types: Spatial GNNs and Spectral GNNs. Spatial GNNs, such as GraphSAGE and GAT, operate directly on the graph structure by defining a neighborhood for each node and aggregating features from these neighboring nodes8. They are flexible and can handle graphs of arbitrary structure, but their computational cost can grow rapidly with increasing neighborhood sizes. On the other hand, Spectral GNNs, like the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), are based on spectral graph theory and leverage graph Laplacian eigenvectors to define convolutions in the spectral domain9. These models can effectively capture global structural properties but often suffer from scalability issues and require pre-computed spectral components, which may limit their applicability to large-scale graphs. Both approaches, despite their strengths, share common limitations, such as (1) high computational and memory requirements, and (2) are heavily reliant on extensive labeled data for effective training.

Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) offer a promising alternative to GNNs by circumventing the high computational and memory requirements associated with the message-passing paradigm10. MLPs are computationally efficient and can be easily parallelized, making them well-suited for large-scale applications and resource-constrained environments. However, MLPs struggle to effectively capture the structural information inherent in graph data, leading to suboptimal performance in node classification tasks. This limitation often arises from their inability to leverage the graph topology, resulting in insufficient representation learning and poor generalization11. In addition, contrastive learning provides a powerful solution to these challenges by enabling MLPs to learn discriminative representations even in the absence of abundant labeled data12. By maximizing agreement between positive pairs (e.g., nodes with similar structural roles) while minimizing agreement with negative pairs, contrastive learning allows MLPs to capture both local and global graph structures without explicit message-passing. This approach not only alleviates the dependency on extensive labeled datasets but also enhances the expressive power of MLPs, making them competitive with, and in some cases superior to, GNNs for node classification tasks.

To achieve a balance between effectiveness and efficiency in node classification, we propose contrastive-learning driven MLPs, called cMLPs. Unlike traditional GNNs, which integrate graph structure into their feed-forward networks and consequently face high computational costs and memory inefficiencies, cMLPs utilize MLPs exclusively as the feed-forward networks. This approach significantly enhances both storage and computational efficiency. To further improve effectiveness, especially when labeled data is scarce, we introduce three types of contrastive learning strategies that capture both local and global information while stabilizing the training process. These contrastive techniques establish clear classification boundaries, leading to superior performance in node classification tasks.

Compared with other approaches to node classification, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

Unlike conventional GNNs commonly used for node classification, our method relies solely on MLPs, enabling faster inference and greater training flexibility.

-

We introduce three distinct types of contrastive learning to enhance MLPs for node classification. These techniques jointly capture both local and global information, significantly boosting the expressive power of MLPs.

-

Extensive experiments demonstrate the strong effectiveness of our method, achieving superior node classification performance as well as improved training and inference efficiency compared to existing GNNs.

Related work

Graph neural networks

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have gained significant attention in the field of node classification due to their ability to learn from graph-structured data by leveraging neighborhood information. The foundational concept behind GNNs is the message-passing mechanism, where each node aggregates features from its neighbors to update its own representation. This paradigm, first formalized in models like GCN13, enables GNNs to capture intricate relational information and achieve strong performance on various graph tasks.

However, message-passing suffers from several limitations. One notable issue is the over-smoothing problem, where the representations of nodes become indistinguishable as the number of layers increases14. This problem restricts the depth of GNNs and limits their ability to capture long-range dependencies. Furthermore, message-passing introduces high computational and memory overhead, especially on large-scale graphs with many nodes and edges. This results in inefficiencies during training and inference15. Additionally, GNNs are known to require extensive labeled data for effective training, which can be a bottleneck in scenarios with limited annotations16.

Spectral GNNs

Spectral Graph neural networks (GNNs), such as graph convolutional networks (GCNs)13 and ChebNet17, leverage the spectral properties of the graph Laplacian to perform convolutions in the frequency domain, effectively capturing global graph structure. However, these methods suffer from high computational costs due to the need to compute eigenvectors, which hinders scalability on large graphs. Solutions such as ChebNet17 use Chebyshev polynomial approximations to reduce this complexity, while FastGCN18 and AS-GCN19 employ sampling techniques to improve efficiency. Despite these improvements, the reliance on a fixed graph structure makes it challenging for spectral GNNs to handle dynamic or evolving graphs. More recent methods such as PolyCF20 propose optimal spectral filters specifically tailored for collaborative filtering tasks, addressing both computational efficiency and performance. Despite these improvements, spectral methods often assume a static graph structure, limiting their applicability to dynamic graphs.

Another significant issue is the over-smoothing problem, where node representations become indistinguishable as the number of layers increases14. APPNP21 addresses this by combining personalized PageRank with neural networks to retain local information over long-range propagation. Moreover, spectral GNNs often face memory inefficiency when dealing with large-scale graphs. SIGN16 alleviates this by pre-computing feature propagations, reducing memory usage and training time. To further improve efficiency and scalability, Hypergraph-enhanced Dual Semi-supervised Graph Classification22 leverages hypergraphs for more robust feature learning, effectively handling noisy and sparse data. Moreover, to address memory inefficiency in large-scale graphs, methods such as scGCL23 propose using graph contrastive learning frameworks for scRNA-seq data imputation, achieving better memory usage and training efficiency. Although these recent advances have made significant strides, spectral GNNs still face challenges in scalability, memory efficiency, and adaptability to diverse and dynamic graph structures.

Spatial GNNs

Spatial GNNs have become increasingly popular for graph-based tasks due to their ability to aggregate neighborhood information directly on graph structures. However, they face several challenges. One of the primary issues is scalability due to the exponential growth of neighborhood size with deeper layers, leading to high computational and memory costs. Recent methods have attempted to address this problem. For instance, GAT24 introduced attention mechanisms to focus on important neighbors, reducing the negative effects of over-smoothing. To further address this issue, PNA25 employs diverse aggregation functions to maintain the distinction between node features. Cluster-GCN26 introduces graph partitioning to enable mini-batch training on subgraphs, while GraphSAINT27 leverages graph sampling to limit the effective graph size during training, making it feasible for large-scale graph processing. More recently, STAG28 proposes a dynamic graph partitioning strategy to maintain low latency and staleness during GNN training, enhancing scalability and efficiency.

Another significant challenge of spatial GNNs, is the over-smoothing problem, similar to spectral GNNs. To counteract this, PNA (Principal Neighborhood Aggregation) employs diverse aggregation functions to maintain the distinction between node features. Similarly, DropEdge reduces over-smoothing by randomly removing edges during training to limit the propagation depth of information. Newer methods like TGOPT29 optimize temporal graph attention networks by reducing redundancy, and PiPAD30 utilizes pipelined and parallel training strategies to improve training efficiency without compromising performance. These advancements address key limitations in spatial GNNs, making them more scalable, efficient, and effective across various graph-based applications.

Contrastive learning

Contrastive learning is a self-supervised learning approach designed to learn robust representations by contrasting similar and dissimilar samples. It effectively tackles the problem of limited labeled data by exploiting information from the structure of unlabeled data, thereby learning meaningful features without the need for extensive annotations. This is particularly useful in scenarios where acquiring labeled data is challenging or expensive. However, traditional contrastive learning methods face challenges such as the need for large batch sizes, complex augmentation strategies, and difficulty in selecting appropriate negative samples. To address these issues, several methods have been proposed. For example, SimCLR31, MoCo32, and SwAV33 have developed strategies to efficiently use large batch sizes and memory banks for better negative sampling. While effective, these methods can significantly increase computational complexity and training time. To reduce this complexity, methods like BYOL34 and SimSiam35 avoid the use of negative samples or large memory banks, instead focusing on minimizing redundancy between representations. These approaches reduce the computational burden and simplify the training process, making them more suitable for practical applications where resources are limited. Overall, while contrastive learning with additional modules can enhance performance, methods that do not rely on such complexities offer a more scalable and efficient alternative for representation learning.

Contrastive learning with additional modules

Several graph contrastive learning (GCL) methods employ additional modules to enhance the model’s learning capacity. These approaches often introduce mechanisms such as graph structure learning, adversarial training, and rationale generation to better capture structural patterns or increase robustness. For example, AD-GCL36 introduces adversarial perturbations to reduce redundancy in graph views, while GraphACL37 actively generates difficult negative samples to train the model. Similarly, RGCL38 uses a rationale generator to identify discriminative subgraphs, and AutoGCL39 automatically learns the augmentation strategy. SUBLIME40 (Self-Supervised Learning with Augmented Graphs for Structure Learning) and GCS41 both employ complex graph structure learning to fine-tune augmentations.

These additional modules can improve the expressiveness of the learned representations, especially in scenarios where graph structures are noisy or incomplete. However, these techniques significantly increase the computational cost and model complexity, making training more challenging on large-scale graphs. The necessity of jointly optimizing the contrastive learning task along with the additional module can lead to instability during training and requires careful tuning of hyper-parameters. This increased complexity and computational burden make these methods less suitable for resource-constrained environments or real-time applications.

Contrastive learning without additional modules

In contrast, many GCL methods focus on simplicity and efficiency by avoiding additional modules, relying solely on data augmentations like stochastic perturbations, subgraph sampling, and structural augmentation. For instance, GRACE42 uses simple feature and structure perturbations to create graph views, while GraphCL43 employs various augmentation techniques such as node dropping and feature masking. SimGRACE44 leverages the original graph data and perturbed GNN encoders without relying on augmentation strategies. Another approach, DGI45, contrasts local node representations with a global graph summary to improve graph representation learning. Methods like MVGRL46 and GCA47 use simple diffusion processes or neighborhood sampling for contrastive pairs.

These approaches have the advantage of significantly reducing computational overhead since they do not require complex external modules. The simplification in architecture leads to faster training and inference times and lowers memory requirements, making these methods more suitable for large-scale graph tasks or when computational resources are limited. The ability to work effectively without extra modules also makes them more adaptable to different graph types and tasks. In comparison to the module-heavy methods, these simpler strategies are easier to implement, require fewer hyper-parameter adjustments, and exhibit better scalability.

Preliminary

We in this section provides some core preliminary knowledge to better understand our approach.

Notations

A graph is typically denoted as \({\textbf{G}} = ({\mathcal {V}}, {\mathcal {E}})\), where \({\mathcal {V}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^n\) represents the set of nodes and \({\mathcal {E}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{|{\mathcal {V}}| \times |{\mathcal {V}}|}\) represents the set of edges. The interactions between nodes are captured by a binary adjacency matrix \({\textbf{A}} \in [0,1]^{n \times n}\), where an element \(a_{ij}\) signifies the presence of an edge between nodes \({\textbf{v}}_i\) and \({\textbf{v}}_j\). The goal of the node classification task is to predict labels or categories for the nodes, using a partially labeled set of nodes with known labels, denoted as \({\textbf{Y}}_L\). To tackle the challenge of limited label information, graph-based message-passing is commonly utilized. This method facilitates the exchange of information between connected nodes, effectively smoothing their representations.

GNNs

We mathematically represent GNNs from Spectral GNNs and Spatial GNNs

Spectral GNNs

Spectral GNNs are based on the graph signal processing framework and operate in the spectral domain of the graph. The key idea is to define convolution operations on graphs using the graph Laplacian. Given the graph Laplacian, \(L\), which is defined as: \({\textbf{L}} = {\textbf{D}} - {\textbf{A}}\), where \({\textbf{A}}\) is the adjacency matrix of the graph and \({\textbf{D}}\) is the degree matrix, with diagonal elements \({\textbf{D}}_{ii} = \sum _{j} {\textbf{A}}_{ij}\). The normalized graph Laplacian is given by \({\textbf{L}}_{\text {norm}} = {\textbf{I}} - {\textbf{D}}^{-1/2} {\textbf{A}} {\textbf{D}}^{-1/2}\). The Laplacian can be decomposed as \({\textbf{L}} = {\textbf{U}} \Lambda {\textbf{U}}^\top\) where U is the matrix of eigenvectors and \(\Lambda\) is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues.

For a signal x on the graph, the graph Fourier transform is defined as \(\hat{{\textbf{x}}} = {\textbf{U}}^\top {\textbf{x}}\)

The convolution of \({\textbf{x}}\) with a filter \(g_\theta\) in the spectral domain is defined as:

where \(g_\theta (\Lambda )\) is a diagonal matrix representing the filter in the spectral domain.

Direct computation of the spectral convolution is computationally expensive. The Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)13 simplifies this operation using a first-order approximation as follows:

where \(\tilde{{\textbf{A}}} = {\textbf{A}} + {\textbf{I}}\) is the adjacency matrix with added self-loops. ChebNet17 introduces a computationally efficient approximation of spectral convolutions using Chebyshev polynomials. The layer-wise propagation rule is defined as:

where \({\tilde{L}} = \frac{2L}{\lambda _{\max }} - I\) is the scaled Laplacian. and \(T_k({\tilde{L}})\) is the Chebyshev polynomial of order k. \(\theta _k\) are the Chebyshev coefficients. \(\lambda _{\max }\) is the largest eigenvalue of L.

The Simplified GCN (SGC)15 removes non-linearities and collapses multiple layers into a single linear transformation:

This formula represents repeated propagation steps followed by a single linear transformation, effectively reducing the complexity of GCNs.

Although spectral GNNs show superior performance in node classification, they need to conduct spectral information of whole graph, leading to inefficiency in both training and inference.

Spatial GNNs

Spatial Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) operate directly in the spatial domain by defining convolution operations over the local neighborhoods of nodes. This section provides an overview of the mathematical foundations and key models associated with Spatial GNNs.

In Spatial GNNs, the convolution operation is defined as a neighborhood aggregation process. For each node i, the updated feature representation is obtained by aggregating features from its neighboring nodes. Formally, for a graph \({\textbf{G}} = ({\mathcal {V}}, {\mathcal {E}})\), the node features are updated as follows:

where \({\textbf{h}}_i^{(l)}\) represents the feature vector of node i at layer l, \({\mathcal {N}}(i)\) denotes the set of neighbors. \(c_{ij}\) is a normalization constant, such as \(\sqrt{|{\mathcal {N}}(i)|} \cdot \sqrt{|{\mathcal {N}}(j)|}\). \({\textbf{W}}^{(l)}\) and \({\textbf{W}}_0^{(l)}\) are trainable weight matrices. sigmais an activation function, such as ReLU.

GraphSAGE (Graph Sample and Aggregation)24 is a widely-used spatial GNN that improves scalability by sampling a fixed number of neighbors for each node. The update rule for each node is given by:

where the AGGREGATE function can be mean, LSTM-based, or pooling-based aggregation.

GAT (Graph Attnetion Networks)48 introduces an attention mechanism to spatial GNNs, allowing nodes to assign different importance weights to their neighbors. The attention coefficients between nodes \(i\) and \(j\) are computed as:

where \({\textbf{a}}\) is a learnable attention vector. \(\Vert\) denotes the concatenation operation. The normalized attention coefficients are obtained using the softmax function \(\alpha _{ij} = \frac{\exp (e_{ij})}{\sum _{k \in {\mathcal {N}}(i)} \exp (e_{ik})}\), and the node features are then updated as \({\textbf{h}}_i^{(l+1)} = \sigma \left( \sum _{j \in {\mathcal {N}}(i)} \alpha _{ij} {\textbf{W}} {\textbf{h}}_j^{(l)} \right)\)

Different from spectral GNNs which are based on eigen-decomposition of high-complexity, these spatial methods employ direct neighbor information with aggregation operators to ensure that spatial GNNs can scale to large graphs while maintaining performance.

Contrastive learning

Contrastive Learning is a self-supervised learning technique that aims to learn effective representations by pulling similar samples closer and pushing dissimilar samples apart in the embedding space. It has been widely adopted for tasks where labeled data is scarce, as it can leverage large amounts of unlabeled data to learn meaningful representations.

Basic formulation

The core idea of contrastive learning is to learn an encoder \(f(\cdot )\) that maps input data \(x\) into a representation space, such that similar inputs (positive pairs) have closer representations than dissimilar inputs (negative pairs). The encoded representation of an input \(x_i\) is given by:

For a given input \(x_i\), let \(x_i^+\) be a positive sample (e.g., an augmented version of \(x_i\)), and \(x_i^-\) be a negative sample (e.g., a different input from \(x_i\)). The goal is to minimize the distance between \({\textbf{h}}_i\) and \({\textbf{h}}_i^+\) while maximizing the distance between \({\textbf{h}}_i\) and \({\textbf{h}}_i^-\).

Contrastive loss

A common loss function used in contrastive learning is the contrastive loss49, which is defined as:

where N is the number of training samples. \(y_i = 1\) if \({\textbf{h}}_j = {\textbf{h}}_i^+\) (positive pair), and \(y_i = 0\) if \({\textbf{h}}_j = {\textbf{h}}_i^-\) (negative pair). \(d({\textbf{h}}_i, {\textbf{h}}_j) = \Vert {\textbf{h}}_i - {\textbf{h}}_j \Vert _2\) is the distance (e.g., Euclidean distance) between representations \({\textbf{h}}_i\) and \({\textbf{h}}_j\). m is a margin parameter that defines how far apart negative pairs should be.

A widely used variant of contrastive loss is the InfoNCE loss50, which is particularly useful for contrastive learning in high-dimensional embedding spaces. The InfoNCE loss is formulated as follows:

where \(\text {sim} \left( {\textbf{h}}_i, {\textbf{h}}_j \right) = \frac{{\textbf{h}}_i \cdot {\textbf{h}}_j}{\Vert {\textbf{h}}_i\Vert \Vert {\textbf{h}}_j\Vert }\) is the cosine similarity between representations \({\textbf{h}}_i\) and \({\textbf{h}}_j\). \(\tau\) is a temperature parameter that controls the concentration level of the distribution. The denominator sums over all positive and negative samples in the batch, encouraging the network to assign higher similarity to positive pairs compared to all other pairs.

A crucial aspect of contrastive learning is the use of data augmentation to generate positive pairs. Common augmentations include transformations such as cropping, color distortion, and rotation in computer vision, or subgraph extraction and node masking in graph-based tasks. Given an original input x, two augmented views \(x_i\) and \(x_i^+\) are created, and the model is trained to maximize their agreement in the representation space:

This strategy enables the model to learn invariances and robust features without requiring explicit labels.

Contrastive learning provides a powerful framework for self-supervised learning by utilizing unlabeled data to learn meaningful representations. The combination of carefully designed loss functions and effective data augmentation techniques allows contrastive learning models to achieve state-of-the-art performance across various domains, including computer vision, natural language processing, and graph-based learning.

Even thought contrastive learning is widely used in computer vision and natural language processing, most exiting techniques cannot directly applied to graph learning as graph structure has it unique characters. For instance, cropping, rotation, color jittering, flipping, and Gaussian blur are widely used in CV while cannot used in graphs. Moreover, some graph learning use contrastive learning to output better graph representation, while they usually introduce extra module to augment graph representation51, leading to inefficiency.

Approach

We provide details of our proposed approach’s which is based on contrastive learning-drive MLPs. The frameworks of our approach is demonstrated in Figure 1. We can know that our networks consist of two-layers MLPs merely, and employs three different-grained contrastive learning to augment MLPs to boost performance of node classification, as visualized in the framework. We will detailedly introduce each component of our method.

The framework of our proposed method. Our cMLPs are composed of two-layer MLPs, further enhanced by a three-grained contrastive learning approach–namely, edge-level, feature-level, and node-level contrastive learning–to refine the distribution of the learned node representations and improve their clarity.

Feed-forward networks

Conventional Networks for node classification, like Graph Neural Networks, depend on message-passing mechanism to augment node representation via integrating structure information. To do this, GNNs, usually designed the graph structure into feed-forward networks, shown as in section of preliminary. However, this design could increase the complexity in both training and inference. Specifically, in training phrase, GNNs need to feed the whole graph into the memory to enable message-passing, which could lead to heavy memory usage, limiting its applications especially that based on light-weight sensors or hardware. On the other hand, during the inference phrase after models being trained, it need to conduct message-passing to output reliable prediction, this reliability has to compromises the inference time, leading to inference inefficiency. To alleviate the inefficiency in both training and inference phrase, we employ MLPs for node classification, which can be mathematically represented as:

where \({\textbf{W}}^0\) and \({\textbf{W}}^1\) denotes as the trainable weights in the first and second layers of our approach, \(\sigma (\cdot )\) denote as the activation function, which is ReLU in our experiments. \(Dropout(\cdot )\) denotes as the dropout function which is a regularization technique used in neural networks to prevent overfitting by randomly dropping out units (i.e., setting their activations to zero) during training. The “LN” indicates the Layer Normalization. It is noting that the output can be different after dropout with the same input.

Different from previous GNNs, our MLPs does not integrate graph into networks, and thus prevent our method from inefficiency in both training and inference phrases. First, our method don’t need to feed the whole graph into memory, so it is memory-friendly. Besides, due to the unnecessary of the whole graph in memory, it support batch-training, enhance the applicability of our method in diverse real-world scenarios. Secondly, during inference, our method does not require message-passing, making it time-efficient and suitable for a wider range of practical applications, such as real-time recommendation systems, real-time fraud detection in financial transactions, where fast and efficient predictions are crucial.

However, enormous works has demonstrate that mere MLPs result in poor expressiveness and subsequently a worse performance in node classification. This is because that node classification tasks has insufficient label information, make training easily suffer from over-fitting. To address this issues, graph structure play a core role of inductive bias that can complement label information, which is the reason why GNNs show a large bargain in performance over MLPs.

Contrastive learning is a powerful technique for capturing inherent representations when labeled data is scarce. By encouraging similar samples to be closer and dissimilar samples to be further apart in the embedding space, contrastive learning helps models learn more intrinsic and discriminative features. This enables the model to generalize better and remain robust even with limited labeled data, making it particularly effective in scenarios such as unsupervised and semi-supervised learning52, where traditional methods struggle to extract meaningful information without extensive annotations. Therefore, we proposed three different-grained contrastive learning, including Edge-level Contrastive Learning, Feature-level Contrastive Learning, and Node-level Contrastive Learning, to enhance the expressiveness of MLPs.

Edge-level contrastive learning

In node classification, graph structure has been widely proved to be a core inductive biases that can improve its performance. Different from previous GNNs that merging graph structure into their networks, we pass the graph information into node representations using graph contrastive learning. In graphs, nodes with edges connection are generally share the same labels, known as the homophily assumptions53. Therefore, we can based on this edge information of graph structure to construct the edge-level constrictive learning.

Some observations indicate that successive message-passing over a graph is similar to a single-time message-passing over its multi-hop graph52, and moreover, some research has justified that enlarging receptive field of message-passing in a multi-hop graph could lead to better expressiveness7. Motivated by these two observations, we first constructed the multi-hop graph and then conduct contrastive over it. The construction of multi-hop graph can be mathematically represented as:

With above construction of multi-hop graph, more edge information is introduced. In other words, more sample-pair information can be utilized in contrastive learning. To conduct edge-level contrastive learning, we have

where \(\tau\) is a temperature parameter. \(sim(\cdot ,\cdot )\) denotes as the similarity of two nodes, and \({\mathcal {N}}_i\) denotes as the neighbor set of node i. To minimize the loss, it forces that the similarity of node representations of \(z_i\) and \(z_j\) to be similar to \(a_{ij}\), and thus the graph information can be passed into node representations. This indicate the MLPs can ultize the graph inductive bias like GNNs. Differently, our method don’t need to load the whole graph into memory and thus enable batch training, in a more flexible and memory-friendly way.

One of primary benefits of using contrastive learning instead for message-passing is that it can force similar node to be closer, which can more accurately capture local information of graph, i.e., local learning. This indicates the connected node could be compact and thus classification boundaries could be more clear, as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Feature-level contrastive learning

Even though multi-hop graph could enlarge receptive field for message-passing, while with the hop increase, more noisy edges are introduced54,55. This indicates that nodes with different labels are connected. This series nodes of usually located nearly classifier boundaries. To alleviate this situation, we introduce Feature-level Contrastive Learning. By introducing perturbation onto node representation, it can force model to capture more intrinsic pattern of graph information, so the model could have a clear classifier boundaries.

Most methods conduct feature-level contrastive learning by introduce perturbation into original features, This could destroys the semantic information of nodes. Alternatively, some works propose using extra model to conduct feature level perturbation, while their obviously increase complexity of models. Motivated by the paper56, we could know that different dropout could result in different outputs dues to its randomness. It can be regarded as a perturbation onto node representation. Motivated by this, we repeat the dropout in Eq. (12) to have another output to conduct feature-level contrastive learning, which is represented as:

where \({\textbf{Z}}^+\) is different from \({\textbf{Z}}\) in Eq. (12), and they can be regarded as the contrastive pairs. We can use the following contrasting learning loss to force them get similar as:

where \(\Vert {\textbf{Z}}\Vert _F=\sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^m\sum _{j=1}^n|z_{ij}|^2}\) denotes as Frobenius norm. This enforce two types of node representations to be similar, so it forces models to captures more intrinsic pattern of data to keep stable of output. In other words, this promotes the nodes located near by classifier boundaries to be far away from boundaries and get close to their cluster center, shown as in Fig. 1.

Node-level contrastive learning

We utilize feature-level contrastive learning to capture local information of graph structure. However, current research has explored that taking both local and global information can provides comprehensive information and as a consequence of enhancing expressive ability of models57,58. Motivated by this, we employs contrastive learning to capture global information.

It is challenging to capture global information without using extra module. To solve this issues, we have used the order-shuffle to generate negative sample-pairs via:

where \(shuffle(\cdot )\) denotes as the nodes-level order shuffle, which is set as negative samples-pair, which is parameterized by the following function as:

where \(sim({\textbf{z}},{\textbf{z}}^-)=\frac{{\textbf{z}}\cdot {\textbf{z}}^-}{\Vert {\textbf{z}}\Vert \Vert {\textbf{z}}^-\Vert }\).

There are two cases including inter-class shuffle and intra-class shuffle. Specifically, inter-class shuffle indicates that the negative samples after shuffle are from different class, based on the intuitive that these two nodes should be far away from each other. On the other hand, intra-class shuffle indicates that negative samples after shuffle are from the same class. This is also intuitive that each nodes has its own character show their should be keep different from other nodes from the same classes. For examples, in citation networks whose datasets are widely used for node classification, even two papers belong to the same class, e.g., Computers, one paper could focus on software while the other focus on AI, so they could be different to some degree.

The Node-level Contrastive Learning focus on inter-class and intra-class relationship of nodes, and thus focus on capture global information. Besides, This encourage nodes to far away from inter-class nodes to have clearer classifier boundaries, and also keep their characters. Both situations promote a accurate performance in node classification, shown as in Fig. 1.

It is noted that our approach does not follow the typical contrastive learning setup, which simultaneously considers both positive and negative pairs. Instead, our goal is to encourage node representations to align with more informative or “better” representations. Therefore, we employ Eqs. (14), (16) and (18) to explicitly pull positive pairs closer while pushing away representations that are less desirable, separately. Recent studies59,60 have shown that effective representation learning can be achieved using only positive pairs, as including negative pairs often provides limited additional benefit. By adopting this design, our method simplifies the training process while maintaining high performance and stability.

Loss Function

Our models is designed for node classification, so we use the commonly used cross-entropy for this task, as:

where \({\mathcal {Y}}_L\) denotes as the node set with labels and \({\textbf{Y}}\) is the labels.

We design different-grained contrastive learning to empower MLPs for node classification, so our final loss function is designed as:

where \(\alpha , \beta , \gamma\) are three turnable hyper-parameters for outputting the optimal results.

Overall, our method employs MLPs for node classification due to its efficiency over GNNs. However, its effectiveness can not be guaranteed due to insufficient labels. To improve the its effectiveness, we design three types of contrastive learning in different-grained. Specially, edge-level contrastive learning promote MLPs to capture local graph information and node-level contrastive learning promote capturing global information. Both two types of contrastive learning provide compressive information to improve MLPs’ expressive ability. In addition, we also design the feature-level contrastive learning to force MLPs to capture intrinsic pattern of global and local information. These three types of contrastive learning jointly polish classifier boundaries of MLPs to improve performance of node classification, shown as in Fig. 1. It is notating that three types of contrastive learning are parameter-free, and thus guarantee the efficiency of our proposed methods. We summarised the whole procedures in Algorithm 1.

Complexity analysis

We compare the computational complexity of our cMLPs versus a GNN for the node classification task. Suppose the graph contains n nodes and m edges, and the feature dimension and hidden dimension are both d. Our cMLPs processes each node independently, without explicit message passing across edges. For a single layer with weight matrix \(W \in {\mathbb {R}}^{d \times d}\), the cost of a forward propagation is \({\mathcal {O}}(nd^2)\), and for L layers, the total complexity is \({\mathcal {O}}(Lnd^2)\). Importantly, the computational cost depends only on the number of nodes and does not involve the edge set. In contrast, a standard GNN layer consists of two steps: (i) message passing (neighborhood aggregation), which typically requires a sparse-dense multiplication between the adjacency matrix and node features, incurring a cost of \({\mathcal {O}}(md)\); and (ii) linear transformation, similar to MLP, with cost \({\mathcal {O}}(nd^2)\). For L layers, the overall complexity is \({\mathcal {O}}(L(nd^2 + md))\). When the graph is sparse (\(m = {\mathcal {O}}(n)\)), the asymptotic complexity gap may be moderate. However, for large-scale graphs where \(m \gg n\), the additional \({\mathcal {O}}(md)\) term dominates, making GNNs considerably slower than our cMLPs. Since both models have the same parameterization in these two models, the extra cost comes entirely from the message passing step. Therefore, MLPs enjoy significantly higher efficiency in inference phase, at the expense of ignoring explicit structural information.

Experiments

We conduct extensive experiments to validate the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed method.

Datasets

We evaluate the performance in node classification on eight graph datasets. These datasets are collected from different domains, including citation networks and Wikipedia page networks. In addition, the statistics of datasets are diverse to keep it’s challenging to conduct node classification, like the class number range from 2 to 40. Moreover, we also employs one heterophily graph, i.e., Chameleon, and one large-scale dataset, i.e., Ogbn-arxiv, to evaluate the application of our method in different types of graph. The statistics of used graph data used is summarized in Table 1.

Comparison methods

Eight baseline methods are employed to evaluated the performance of our proposed methods. The brief introduction to each methods are summarized as the follows:

-

MLP61: A fully connected neural network that treats each node independently, ignoring the graph structure. It’s often used as a baseline model for node classification tasks.

-

GCN13: Uses spectral graph convolution to aggregate information from neighboring nodes, effectively learning node representations based on both features and graph topology.

-

GAT48: Introduces an attention mechanism to assign different importance weights to each neighboring node, allowing the model to focus on more relevant neighbors during information aggregation.

-

PPNP21: Combines the strengths of GCN and personalized PageRank, preserving the initial node features while propagating through the graph, which helps prevent over-smoothing and retain local information.

-

G-MLP62: replaces traditional message passing in GNNs with a pure MLP structure and introduces a Neighboring Contrastive loss to leverage graph structure implicitly, achieving efficient and robust node classification without explicit graph connections.

-

LTD63: introduces node-specific temperatures in a knowledge distillation framework for GNNs, optimizing the performance of distilled students by adaptively adjusting the distillation process based on individual node characteristics.

-

Node-F64: uses a scalable all-pair message passing scheme with a kernelized Gumbel-Softmax operator, reducing complexity to enable efficient node classification on large-scale graphs.

-

E2GNN65: an ensemble learning framework that compresses multiple GNN models into a single MLP using knowledge distillation, improving inference efficiency while maintaining high accuracy and robustness in node classification tasks.

In summary, MLP is a typical networks architecture which has been applied various domains. GCN, GAT and PPNP are three typical GNNs where GCN are spectral GNNs and other two are spatial GNNs. G-MLP is MLPs-based methods while only employ graph contrastive learning compared to our method. We also employ three recent methods, where LTD is a distillation method, Node-F is a graph transformer method and E2GNN is a new GNN method. All of them have employed techniques to improve models efficiency.

Implementation

For a fair comparison, all baseline models were obtained from the authors’ official pages or GitHub repositories and were run using the parameter settings recommended in their respective papers. For methods without recommended configurations, we train the models to achieve their best performance, similar to our approach. With the data split, we generally use the default splitting config. If not, we split the training/validation/test set as 5%, 5% and 90% to keep node classification challenging. The exception is large-scale dataset Ogbn-arxiv, due to inference cost. We list the split information in Table 1. Our method was implemented in PyTorch and all experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GPU 4090. The details of the parameter settings are provided in the subsequent experiments, where we utilized hierarchical search to find the optimal parameter combinations. All experiments were repeated five times, and the average results are reported.

Results analysis

We report all results of all methods over all eight dataset in Table 2. Analyzing this table, we have following observations.

Among all the evaluated methods, cMLPs lead the performance rankings, followed by Node-F, LTD, E2GNN, G-MLP, PPNP, GAT, GCN, and MLP. Specifically, cMLPs outperform the second-best method, Node-F, by 0.80% and exceed the baseline MLP by 17.71%. The results demonstrate that cMLPs consistently achieve the highest average performance across all datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of our approach in various graph structures.

Compared with three typical GNNs methods, i.e., GCN, GAT, PPNP, our cMLPs improve by 10.0% on average across all datasets and three methods, indicating that message-passing is not the only effective strategy for node classification; contrastive learning driven MLPs can also exhibit strong potential for this task. Since contrastive learning can effectively alleviate the dependence of label information, our cMLPs could outperform these GNNs in node classification where only a small part of labels are available.

Compared with MLP based methods, i.e., MLP and G-MLP, our method improve by 12.24%, indicating the effectiveness of the contrastive learning used in our cMLPs. Compared to G-MLP that use graph contrastive learning, i.e., edge-level contrastive learning, which focus on capturing local information, our cMLPs employ node-level contrastive learning to capture global information, and thus provide comprehensive information for model to improve its expressiveness.

Compared with recent methods, i.e., LTD, Node-F, E2GNN, our method improves by 3.83%. Even these methods employ more advanced architecture of networks to improve performance, our method employ three types of contrastive learning to empowered MLPs to capture different-grained information. This not only preserve the expressiveness but also guarantee the efficiency, which will be shown in the following section.

Moreover, our method demonstrate superiority in different types of graph data, including a heterophily graph, i.e., Chameleon and a large-scale graph, i.e., Ogbn-arxiv. This indicates the strong adaption of our MLP-based cMLPs. Moreover, by using batch training with batch size as 2000, i.e., cMLPS-2k, 0.59% decline can be observed compared to cMLPs, while outperform the best comparison method Node-F. This indicates that MLP-based support well for mini-batch training, validating the flexibility of our methods.

Ablation study

To better understand the contribution of each component in our proposed method, we conduct an ablation study by systematically removing or altering key modules. This allows us to assess the impact of each component on the overall performance and to provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of our approach. The results of these experiments in Table 3, are discussed in the following analysis.

no all- which removes all contrastive learning components, results in the lowest performance across most datasets. For example, the accuracy drops significantly to 59.67 from 83.96 on Cora (a decline of 24.29%) and 41.30 from 52.36 on Chameleon (a decline of 11.05%), indicating that the complete absence of contrastive learning severely limits the model’s capability to capture complex relationships, and trop down to MLP-level.

no edge- which removes edge-level contrastive learning keeps similar performance to no all- and MLPs. This indicates the importance of graph structure in node classification, as a critical inductive bias, being consistent with observation in previous GNNs work. Moreover, due to other two contrastive learning components, no edge- show a slight improvement of 0.90%, indicating the effectiveness of other two contrastive learning.

no feature- which removes feature-level contrastive learning and no node- which removes node-level contrastive learning show a slight decline respectively by 0.61% and 0.52%, compared with cMLPs. This validates that the effectiveness of two contrastive learning components. Intrinsically, after capture local graph information by edge-level contrastive learning, feature- and node- encourage MLPs to capture intrinsic and global information, so both promote the performance.

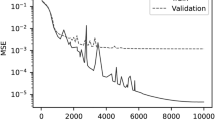

Hyper-parameter analysis

To evaluate the sensitivity of our proposed method to different hyper-parameters, we conduct experiments by varying the key loss function coefficients, i.e., \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\). This analysis provides insights into how different contrastive learning components affect the overall performance, as shown in Figure 2. In addition, we investigate the influence of the hop number and batch size on model performance, with the results summarized in Figure 3.

The performance of our cMLPs model is highly sensitive to the value of \(\alpha\), while it exhibits relatively lower sensitivity to variations in \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\). In particular, the model’s performance is generally suboptimal when \(\alpha\) is set to a low value around \(10^{-3}\). As \(\alpha\) increases, the incorporation of more graph information enhances the model’s performance, which then stabilizes. In contrast, variations in \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) result in relatively consistent performance across their respective ranges. This observation aligns with the findings from the ablation study, where edge-level contrastive learning, governed by \(\alpha\), was shown to have a more pronounced impact on overall performance compared to the other two types of contrastive learning.

For the impact of the hop number on the performance of our proposed method in Figure 3, the best performance is typically achieved when the hop number is set to 2 or 3, which is consistent with the general observation in GNNs that overly shallow or overly deep propagation is suboptimal. When the hop number increases beyond this point, the performance gradually declines. A possible reason is that, with larger hops, the neighborhood expansion introduces a higher proportion of dissimilar nodes. These dissimilar nodes may be incorrectly selected as positive pairs, making it difficult for our cMLPs to learn accurate neighborhood relationships, which in turn degrades performance.

We further investigate the effect of batch size on the performance of our method in Fig. 3. As the batch size increases, the ACC gradually improves, indicating that very small batch sizes may disrupt the integrity of graph information and adversely affect our method. However, even at a batch size corresponding to 10% of the nodes, our method still achieves competitive performance, demonstrating its superior flexibility in handling limited batch information.

Distribution of node representations

We visualize the distributions of node embeddings learned by standard GCNs and our proposed cMLPs, with the results shown in Fig. 4. The visualization indicates that cMLPs produce a more compact distribution with clearer class boundaries compared to GCNs, which naturally facilitates improved classification performance. This compactness can be attributed to our multi-grained contrastive learning strategies, which explicitly enforce that similar nodes are mapped close together in the embedding space, while dissimilar nodes are pushed farther apart. Consequently, the learned representations exhibit better separability, leading to enhanced downstream performance.

Inference efficiency

To assess the computational efficiency of our proposed method, we conduct experiments comparing the inference time across various models. We measure the inference time on a fixed set of nodes and analyze how our approach performs relative to other baseline methods. The results, as summarized in Fig. 5, provide insights into the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost, which are discussed in the following analysis.

The results in the figure demonstrate a clear trade-off between inference time and accuracy across various models. Our proposed method, cMLPs, achieves the highest accuracy while maintaining relatively low inference time (around 7.7 ms), showcasing its efficiency in node classification tasks. In comparison, traditional GNN models such as GCN and GAT require significantly longer inference times (50.6 ms and 83.64 ms, respectively) to achieve similar or slightly lower accuracy levels. This indicates that cMLPs can process data faster while providing superior or comparable performance.

Conclusion

We proposed using contrastive learning to empower MLPs for node classification. To do this, we designed three different-grained and parameter-free contrastive learning to improve the effectiveness and also efficiency of MLPs, where edge-level and node-level contrastive learning is employed respectively to capture local and global information of nodes, providing comprehensive information for MLPs to improve its expressiveness. In addition, feature-level contrastive learning is designed to capture more intrinsic information. Extensive experiments were conducted and results demonstrate that our method outperform typical GNNs and current methods in both effectiveness and efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the torch geometric.datasets repository, Click here to access the web of data information . https://pytorch-geometric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/modules/datasets.html

References

Xiao, S., Wang, S., Dai, Y. & Guo, W. Graph neural networks in node classification: survey and evaluation. Mach. Vis. Appl. 33(1), 4 (2022).

Bhagat, S., Cormode, G. & Muthukrishnan, S. Node classification in social networks. Soc. Netw. Data Anal. 2011, 115–148 (2011).

Li, S. S. & Karahanna, E. Online recommendation systems in a b2c e-commerce context: a review and future directions. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 16(2), 2 (2015).

Paul, S. G., Saha, A., Hasan, M. Z., Noori, S. R. H. & Moustafa, A. A systematic review of graph neural network in healthcare-based applications: recent advances, trends, and future directions. IEEE Access 2024, 652 (2024).

Hu, Y. & Bin, J. Research on online vocational education based on graph neural networks. In 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computational Networks (ICISCN) 1–7 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICISCN64258.2025.10934704.

Liang, X., Li, X., Shu, L., Wang, X. & Luo, P. Tourism demand forecasting using graph neural network. Curr. Issue Tour. 28, 982–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2024.2320851 (2025).

Feng, J., Chen, Y., Li, F., Sarkar, A. & Zhang, M. How powerful are k-hop message passing graph neural networks. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 4776–4790 (2022).

You, J., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Design space for graph neural networks. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 17009–17021 (2020).

Wang, X. & Zhang, M. How powerful are spectral graph neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 23341– 23362 (PMLR, 2022).

Chen, L., Chen, Z. & Bruna, J. On graph neural networks versus graph-augmented mlps. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.15116 (2020).

He, X., Hooi, B., Laurent, T., Perold, A., LeCun, Y. & Bresson, X. A generalization of vit/mlp-mixer to graphs. In International Conference on Machine Learning 12724– 12745 (PMLR, 2023).

Yuan, L., Jiang, P., Hou, W. & Huang, W. G-mlp: graph multi-layer perceptron for node classification using contrastive learning. IEEE Access 2024, 526 (2024).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Li, Q., Han, Z. & Wu, X.-M. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 32 (2018).

Wu, F., Souza, A., Zhang, T., Fifty, C., Yu, T. &Weinberger, K. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 6861– 6871 (PMLR, 2019).

Frasca, F. et al. Sign: scalable inception graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.11198 (2020).

Defferrard, M., Bresson, X. & Vandergheynst, P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29, 856 (2016).

Chen, J., Ma, T. & Xiao, C. Fastgcn: fast learning with graph convolutional networks via importance sampling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.10247 (2018).

Huang, W., Zhang, T., Rong, Y. & Huang, J. Adaptive sampling towards fast graph representation learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31, 859 (2018).

Qin, Y., Ju, W., Luo, X., Gu, Y. & Zhang, M. Polycf: towards the optimal spectral graph filters for collaborative filtering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12590 (2024).

Gasteiger, J., Bojchevski, A. & Günnemann, S. Predict then propagate: Graph neural networks meet personalized pagerank. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.05997 (2018).

Ju, W. et al. Hypergraph-enhanced dual semi-supervised graph classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04773 (2024).

Xiong, Z. et al. Scgcl: an imputation method for scrna-seq data based on graph contrastive learning. Bioinformatics 39(3), 098 (2023).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 856 (2017).

Corso, G., Cavalleri, L., Beaini, D., Liò, P. & Veličković, P. Principal neighbourhood aggregation for graph nets. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 13260–13271 (2020).

Chiang, W.-L. et al. Cluster-gcn: an efficient algorithm for training deep and large graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 257– 266 (2019).

Zeng, H., Zhou, H., Srivastava, A., Kannan, R. & Prasanna, V. Graphsaint: graph sampling based inductive learning method. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.04931 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Stag: enabling low latency and low staleness of gnn-based services with dynamic graphs. In 2023 IEEE 41st International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD) 170– 173 (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, Y. & Mendis, C. Tgopt: redundancy-aware optimizations for temporal graph attention networks. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGPLAN Annual Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming 354– 368 (2023).

Wang, C., Sun, D. & Bai, Y. Pipad: pipelined and parallel dynamic gnn training on gpus. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGPLAN Annual Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming 405– 418 (2023).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International Conference on Machine Learning 1597– 1607 (PMLR, 2020).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 9729– 9738 (2020).

Caron, M. et al. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9912–9924 (2020).

Grill, J.-B. et al. Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 21271–21284 (2020).

Chen, X. & He, K. Exploring simple siamese representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 15750– 15758 (2021).

Suresh, S., Li, P., Hao, C. & Neville, J. Adversarial graph augmentation to improve graph contrastive learning. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 15920–15933 (2021).

Luo, X. et al. Self-supervised graph-level representation learning with adversarial contrastive learning. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 18(2), 1–23 (2023).

Li, S., Wang, X., Zhang, A., Wu, Y., He, X. & Chua, T.-S. Let invariant rationale discovery inspire graph contrastive learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning 13052– 13065 (PMLR, 2022). PMLR

Yin, Y., Wang, Q., Huang, S., Xiong, H. & Zhang, X. Autogcl: Automated graph contrastive learning via learnable view generators. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 36 8892– 8900 (2022).

Liu, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhang, D., Chen, H., Peng, H. & Pan, S. Towards unsupervised deep graph structure learning. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022 1392– 1403 (2022).

Wei, C., Wang, Y., Bai, B., Ni, K., Brady, D. & Fang, L. Boosting graph contrastive learning via graph contrastive saliency. In International Conference on Machine Learning 36839– 36855 (PMLR, 2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Deep graph contrastive representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.04131 (2020).

You, Y. et al. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 5812–5823 (2020).

Xia, J., Wu, L., Chen, J., Hu, B. & Li, S. Z. Simgrace: a simple framework for graph contrastive learning without data augmentation. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022 1070– 1079 (2022).

Veličković, P. et al.. Deep graph infomax. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.10341 (2018).

Hassani, K. & Khasahmadi, A. H. Contrastive multi-view representation learning on graphs. In International Conference on Machine Learning 4116– 4126 (PMLR, 2020).

Zhu, Y. et al.. Graph contrastive learning with adaptive augmentation. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 2069– 2080 (2021).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903 (2017).

Hadsell, R., Chopra, S. & LeCun, Y. Dimensionality reduction by learning an invariant mapping. In 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06), vol. 2 1735– 1742 (IEEE, 2006).

Oord, A.v.d., Li, Y. & Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.03748 (2018).

Mo, Y., Chen, Y., Peng, L., Shi, X. & Zhu, X. Simple self-supervised multiplex graph representation learning. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia 3301– 3309 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Deng, Z., Chen, Y., Amor, R. & Witbrock, M. Chain of propagation prompting for node classification. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia 3012– 3020 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Beyond homophily in graph neural networks: current limitations and effective designs. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 7793–7804 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. Robust node classification on graph data with graph and label noise. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 38 17220– 17227 (2024).

Wang, G., Ying, R., Huang, J. & Leskovec, J. Multi-hop attention graph neural network. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.14332 (2020).

Gao, T., Yao, X. & Chen, D. Simcse: simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08821 (2021).

Zhu, Y., Huang, J., Chen, Y., Amor, R. & Witbrock, M. A graph transformer defence against graph perturbation by a flexible-pass filter. Inf. Fusion 107, 102296 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. Local and global structure preservation for robust unsupervised spectral feature selection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 30(3), 517–529 (2017).

Tian, Y., Chen, X., Ganguli, S.: Understanding self-supervised learning dynamics without contrastive pairs. In International Conference on Machine Learning 10268– 10278 (PMLR, 2021).

Wu, J. et al. Rethinking positive pairs in contrastive learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.18200 (2024).

Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 65(6), 386 (1958).

Hu, Y. et al. Graph-mlp: Node classification without message passing in graph. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.04051 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. Learning to distill graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining 123– 131 (2023).

Wu, Q., Zhao, W., Li, Z., Wipf, D. & Yan, J. Nodeformer: a scalable graph structure learning transformer for node classification. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2023).

Zhang, X., Zha, D. & Tan, Q. E2gnn: efficient graph neural network ensembles for semi-supervised classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.03401 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Guangxi Vocational and Technical College of Manufacture Engineering and Guangxi Academy Science of Industry-University-Research for their support or assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangxi Vocational and Technical College of Manufacture Engineering and the Guangxi Academy of Sciences of Industry-University-Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qi Bao designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Xiyu Huang and Wenbin Zhuang collected and analyzed the data. Pan Pan revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. No personal or sensitive data was collected. All datasets used in this study are publicly available, and no additional ethical approval was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, Q., Huang, X., Zhuang, W. et al. Multi-grained contrastive-learning driven MLPs for node classification. Sci Rep 15, 35156 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19189-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19189-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fault-class coverage–aligned combined training for AFDD of AHUs across multiple buildings

Scientific Reports (2025)