Abstract

This study evaluates the effectiveness of a small particle reagent (SPR) formulation based on Phloxine B dye for developing latent fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces. The primary objectives were to assess the formulation’s ability to produce fingerprints over time and determine its shelf life. The reagent was tested on three non-porous surfaces—glass, aluminium foil, and plastic transparency sheets—submerged in tap water for a duration of 30 days. Additionally, the study extended to evaluate the reagent’s performance on surfaces submerged in sewage water. The results demonstrated that the formulation successfully developed high quality identifiable fingerprints over a period of 27 days on glass, 29 days on transparency sheets, and 24 days on aluminium foil, after submersion in tap water. In the case of surfaces submerged in sewage water for 84 h, metal produced higher-quality and more durable prints compared to glass and plastic. On average, the Phloxine B-based SPR formulation demonstrated a shelf life of about 60 days. This Phloxine B-based SPR composition offers a non-toxic, cost-effective, and highly efficient approach, in the recovery of latent fingerprints from submerged non-porous surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recovery of latent fingerprints plays a pivotal role in criminal investigations, often serving as a crucial link between the evidence and suspect1. However, obtaining usable fingerprints from wet or submerged surfaces remains a significant challenge. This is particularly relevant given the common practice of criminals disposing of weapons or evidence into water bodies to evade detection2. Developing fingerprints from surfaces submerged in harsh environments, such as sewage water, presents further challenges. Sewage water, a complex mixture of water, waste, salts, chemicals, and microorganisms, exacerbates fingerprint degradation due to microbial activity and environmental contaminants3,4.

Small particle reagent has emerged as a specialised technique for developing latent fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces5. Unlike traditional powdering methods, which are ineffective on moist or water-exposed surfaces, SPR involves a suspension of fine particles that adhere to the fingerprint residues, rendering the ridges visible for analysis3.

The SPR technique has proven valuable for visualising fingerprints on non-porous surfaces but conventional formulations do not always provide adequate contrast or durability. Traditional small particle reagents, such as those based on molybdenum disulphide, have limitations, particularly with regard to contrast and sensitivity, which restrict their effectiveness in forensic applications1. As a result, researchers have sought to enhance existing SPR formulations to address these shortcomings. One promising alternative involves the use of Phloxine B dye, a fluorescent compound known for its strong contrast properties6. Owing to its fluorescent nature, weak and faint fingerprints can be developed, and fingerprints on multi-coloured surfaces can also be visualised.

In this method, the lipid component of sweat are primarily targeted. The ionic end of the detergent exhibits an affinity for basic zinc carbonate, while the hydrophobic (organic) end shows an affinity for the lipid fraction of the fingerprint residue. This dual affinity facilitates the formation of a bridge between the lipids and the basic zinc carbonate. Subsequently, the Phloxine B dye becomes adsorbed onto this hydrophobic–hydrophilic complex, thereby imparting contrast and rendering the latent prints visible.

The present study evaluates the efficacy of a Phloxine B-based SPR formulation in terms of contrast, sensitivity, and shelf life for developing fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces, specifically glass, metal (aluminium foil), and plastic (transparency sheets), which are commonly encountered in forensic investigations. The selection of these substrates was guided by key surface properties that make them particularly suitable for latent fingerprint research. Their high durability ensured that the materials could withstand handling during experiments; their excellent resistance to water allowed them to maintain structural integrity and avoid degradation during immersion; and their low chemical reactivity minimised potential interactions with fingerprint residues or processing reagents, thereby preserving latent print quality for accurate analysis.

Additionally, the study extends its scope to assess fingerprint development on surfaces submerged in sewage water, including stainless steel, glass, and plastic. Stainless steel was selected instead of aluminium foil for sewage water testing because it offers a smoother, more uniform, and corrosion-resistant surface. Unlike aluminium foil, which can rapidly pit or corrode when exposed to the chemical and biological components of sewage, stainless steel maintains its integrity for longer periods, ensuring more reliable fingerprint recovery. Moreover, the substitution of the metal substrate between these two parts of the study was intended to simulate diverse real-world conditions and examine the formulation’s performance across different metal surfaces frequently encountered in forensic casework. This research aims to address existing gaps in forensic methodologies and contribute to the advancement of fingerprint recovery techniques.

Materials and methods

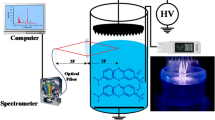

Reagent preparation

The SPR formulation used in this study was prepared by combining 45 g of basic Zinc carbonate (Sigma-Aldrich™) with 600 mL of distilled water, 900 mg of Phloxine B dye (Sigma-Aldrich™), and 0.53 mL of liquid detergent (Ezee™), which served as a surfactant due to its suitable chemical and physical properties, such as surface tension, miscibility, and particle dispersion ability. The formulation was stored in a reagent bottle and kept in a cool, dark environment to prevent contamination or evaporation, thereby maintaining its stability and effectiveness.

Surfaces submerged in tap water

Three types of non-porous surfaces—glass slides, aluminium foil, and transparency sheets (biaxially oriented polyethylene terephthalate)—were selected for the study. A total of 60 samples were prepared for each surface type, resulting in 180 fingerprint-bearing samples overall. Each sample bore a single latent fingerprint, deposited by a single donor (with informed written consent).

To ensure consistency, all fingerprints were collected from the same donor so that ridge characteristics remained uniform across samples. The donor was instructed to touch the thumb to the nose to ensure the transfer of both eccrine and sebaceous secretions. The thumb was then rubbed uniformly to evenly distribute the secretions before deposition. During deposition, the applied pressure was qualitatively controlled to maintain comparable intensity across imprints, while the angle of finger placement was kept consistent throughout the collection process. For standardisation of positioning and size, pre-marked fingerprint slips were used to guide finger placement, ensuring uniform orientation and dimensions across all prints. Each prepared surface was then used to obtain a single latent print under controlled conditions. The procedure was repeated until all 180 samples were completed.

To allow for duplicate testing, two samples of each surface type were retrieved daily over a 30-day immersion period. All 180 samples were simultaneously submerged in tap water within five minutes of fingerprint deposition, minimising potential degradation from environmental exposure.

Upon retrieval each day, the samples were immediately subjected to fingerprint development using the Phloxine B-based SPR formulation. The SPR suspension was agitated by gentle shaking prior to use to ensure uniform particle distribution and consistent suspension properties. Care was taken to avoid excessive shaking that could cause foam formation or alter particle characteristics. Fingerprint development was carried out by immersing each sample in the reagent for 1–2 min, followed by gentle rinsing with distilled water to remove excess SPR.

The developed fingerprints were then air-dried under natural conditions. Alternatively, drying may be facilitated using a hair dryer (no adverse effect on the quality of the developed fingerprints is observed in either case, indicating that post-immersion drying methods or minor delays before development does not influence the final fingerprint quality). Developed prints were then assessed using the five-grade quality scale as described by Castello et al.1. This scale clearly defines each grade from 0 (no visible ridge detail) to 5 (excellent-quality prints), providing uniform criteria for factors such as image crispness, ridge alignment, and contrast with the background. The lowest detectable threshold was determined based on ridge clarity and the ability to discern sufficient fingerprint minutiae for forensic identification. By using this common reference scale, all examiners applied the same standards, ensuring consistency and reliability in grading.

As a safety precaution, appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves and safety goggles, was routinely used during fingerprint processing.

Surfaces submerged in sewage water

Three types of non-porous surfaces—glass slides (glass), stainless steel sheets (metal), and transparency sheets made of biaxially oriented polyethylene terephthalate (plastic)—were selected for this part of the study. A total of 14 samples were prepared for each surface type, resulting in 42 fingerprint-bearing samples overall. Each sample bore a single latent fingerprint, deposited by a single donor following the same method as previously described. All samples were submerged in sewage water, collected from a local sewer pipeline, within five minutes of deposition, to replicate realistic environmental exposure and minimise external degradation.

The immersion duration was set for 84 h, and two samples of each surface type were retrieved every 12 h to allow for duplicate analysis at each time interval. Upon retrieval, each sample was immediately subjected to latent fingerprint development using the Phloxine B-based SPR formulation. The reagent was agitated beforehand to ensure a uniform particle suspension, and samples were immersed in the SPR solution for 1–2 min. Following development, excess reagent was rinsed off using distilled water, and the samples were air-dried. The developed fingerprints were evaluated using the five-grade fingerprint quality assessment scale described by Castello et al.1, with Grade 5 representing excellent-quality ridge detail and Grade 0 indicating no visible print.

Shelf life

The shelf life of the formulation was evaluated by developing fresh latent fingerprints daily on the non-porous surfaces used in this study. Each day, fresh fingerprints were developed by immersing the surface in the same batch of the SPR formulation for 1–2 min. The quality of the developed fingerprints was assessed using the five-grade fingerprint quality assessment scale1.

Results

Surfaces submerged in tap water

Glass

Latent fingerprints developed on glass slides maintained excellent quality (Grade 5) for the first 15 days of submersion. After this period, a gradual decline in quality was observed, with prints classified as Grade 4 between days 16 and 23, and as Grade 3 from days 24 and 27. By the 28th day, fingerprints had degraded to Grade 2, indicating a significant loss of clarity and ridge detail. Notably, no fingerprints were classified as Grade 1 (poor quality) throughout the 30-day observation period, underscoring the reagent’s efficacy on glass surfaces (Fig. 1).

Plastic

On plastic transparency sheets, fingerprints retained excellent quality (Grade 5) for 10 days before showing a gradual decline. Prints were classified as Grade 4 from days 11 and 21 and as Grade 3 between days 22 and 29. By day 30, fingerprint quality further declined to Grade 2 (Fig. 2). The absence of Grade 1 prints highlights the reagent’s effectiveness; however, the faster degradation compared to glass suggests a lower retention of fingerprint clarity on transparency sheets.

Metal

Fingerprint quality on aluminium foil deteriorated the fastest among the three surfaces (Fig. 3). Grade 5 prints remained visible for a duration of 8 days, followed by a decline to Grade 4 between days 9 and 13. From days 14 to 24, prints were categorised as Grade 3 before further degrading to Grade 2 between days 25 and 28. By days 29 and 30, only poor-quality (Grade 1) prints were observed, indicating the reagent’s lowest efficacy on this substrate. Table 1; Fig. 4 summarise the detailed results.

Surfaces submerged in sewage water

In sewage water samples, minor background staining was occasionally observed, primarily due to organic impurities. This background, however, did not significantly interfere with ridge visibility. Excess stain was minimised by gently rinsing the developed samples with distilled water, which effectively reduced visually distracting interference while maintaining ridge clarity. Air-drying of the samples further stabilised the developed fingerprints for assessment.

Glass

Fingerprint quality initially remained at Grade 5 during the first 12 h. Between 12 and 36 h, quality declined to Grade 4, followed by a further reduction to Grade 3 between 37 and 48 h. A continued deterioration was observed, with prints dropping to Grade 2 between 49 and 72 h. By 73 h, fingerprints had degraded to Grade 1, indicating significant loss of clarity and ridge detail (Fig. 5).

Metal

Fingerprints on stainless steel maintained excellent quality (Grade 5) throughout the 72-hour immersion period, with no noticeable degradation. After 72 h, a slight decline to Grade 4 was observed, indicating minor deterioration, though the prints remained well-developed and of high quality (Fig. 6).

Plastic

Fingerprints on transparency sheets deteriorated rapidly, reaching Grade 1 or lower within the first 12 h. This rapid degradation highlights the poor retention of latent fingerprints on this surface when submerged in sewage water (Fig. 7). Table 2; Fig. 8 provide a detailed summary of the results.

Shelf life

The shelf life of the SPR formulation was evaluated by developing fresh fingerprints daily on the non-porous surfaces utilised in this study (Fig. 9). Throughout the testing period, fingerprints consistently developed at Grade 5 quality, demonstrating excellent ridge clarity and detail. These results confirm the formulation’s stability and prolonged effectiveness, establishing it as a reliable and durable reagent for forensic fingerprint development over extended periods.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop and evaluate a Phloxine B-based SPR formulation for visualising latent fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces under realistic environmental conditions.

The findings indicate that surface type influences the retention and development quality of submerged latent fingerprints. In both tap and sewage water experiments, smoother and less reflective surfaces like glass and stainless steel facilitated better preservation of ridge detail compared to more textured or hydrophobic surfaces such as aluminium foil or plastic transparency sheets.

Furthermore, a clear difference in the quality of fingerprint development was observed between freshly deposited prints and those aged during submersion. Under tap water immersion (Table 1), latent fingerprints on glass retained Grade 5 quality for up to 15 days, followed by a gradual decline to Grade 1 by Day 30. Plastic surfaces exhibited a faster decline, maintaining Grade 5 quality only until Day 10 and dropping to Grade 1 by Day 30. Metal surfaces demonstrated the most rapid deterioration, with Grade 5 quality persisting only until Day 8 and falling to Grade 1 by Day 29–30. In sewage water immersion (Table 2), the rate of degradation was markedly higher. On glass, Grade 5 quality persisted for the first 72 h, after which it declined to Grade 4 by 84 h. Stainless steel prints began to deteriorate earlier, reaching Grade 1 by 84 h. Plastic surfaces demonstrated the least persistence, with fingerprint quality falling to Grade 0 as early as 13 h post-immersion. These observations suggest that both the age of the print and the immersion medium substantially influence detection efficiency. Freshly deposited prints yield higher grades, whereas prolonged immersion—particularly in contaminated water—accelerates the loss of ridge detail. From a forensic perspective, these findings emphasise the importance of rapid recovery of submerged evidence in order to maximise the likelihood of successful fingerprint development.

The study further highlights the comparatively superior performance of the new SPR formulation on glass and stainless steel surfaces, where high-quality (Grade 5 and 4) fingerprints were recoverable even after extended submersion durations. However, degradation was notably accelerated on plastic surfaces in sewage water, possibly due to their higher hydrophobicity and biofilm formation that interfered with fingerprint residue adherence and SPR reagent action. Additionally, microbial activity and background staining became more evident over time.

The performance of the Phloxine B-based SPR formulation was comparable to, and in some cases exceeded, previously reported formulations. While a direct side-by-side comparison under identical experimental conditions was not conducted, existing studies provide a useful reference for contextualising these findings. For instance, black powder and Sudan black powder-based SPRs developed Grade 5 fingerprints on glass for 5 days1, whereas crystal violet-based SPR extended this duration to 15 days7. Basic fuchsin dye-based SPRs achieved Grade 5 fingerprints for 25 days on stainless steel, 20 days on aluminium foil, and 5 days on glass slides2. Similarly, fluorescent dye-based SPRs using Rhodamine 6G and Rhodamine B yielded high-quality prints for up to 12 days8, while natural dye-based SPRs maintained Grade 5 prints for 16–20 days on stainless steel and 11–15 days on glass slides9.

In terms of stability, the Phloxine B-based SPR formulation demonstrated an average shelf life of approximately 60 days, matching or exceeding the stability of previously reported SPR formulations. For instance, crystal violet-based SPR remained effective for seven weeks7, whereas basic yellow-40 dye-based SPR exhibited a shorter shelf life of 25 days10. Similarly, SPRs utilising activated charcoal and basic fuchsin dye retained effectiveness for 52 days and 50 days, respectively11,2. Notably, the 60-day stability of the current formulation exceeds the conventional 6–8 week range commonly cited for SPRs12. This extended shelf life enhances the formulation’s practical applicability minimising the need for frequent preparation, making it a reliable option for both controlled laboratory settings and field operations.

For operational use outside the laboratory, the reagent can be used effectively within this 60-day window, provided it is stored in airtight, light-protected containers and gently agitated before application to maintain uniform particle suspension and consistent development quality. While field application is feasible when necessary, it is strongly recommended that evidence be processed under controlled laboratory conditions to ensure optimal results and reduce the risk of contamination. These measures enhance reproducibility and facilitate consistent application across different investigators.

Conclusion

This study presents a promising method for the development of latent fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces using a Phloxine B-based small particle reagent formulation. The formulation effectively developed fingerprints on evidence submerged in both tap water and sewage water, demonstrating reliability under environmentally challenging conditions.

A notable strength of the formulation lies in its extended shelf life of about 60 days, on average, which meets or exceeds that of many conventional SPR formulations. This prolonged usability, combined with its effectiveness across diverse surface types, enhances its practical utility in forensic investigations, particularly in cases involving submerged evidence. The technique demonstrates strong performance on submerged items, as the fatty acid component of sweat is immiscible with water, and has shown effectiveness even in turbid water conditions. However, significant variations in pH may adversely affect performance due to the sodium salt of Phloxine B in the formulation, as the organic dye can precipitate under such conditions.

In the present study, Ezee™ detergent was selected as the surfactant for the SPR mix due to its favourable chemical and physical properties, including surface tension, miscibility, and particle dispersion ability. A comparative evaluation of its performance against other surfactants was not undertaken here, but future research should explore this aspect to further validate and optimise its effectiveness.

Although Phloxine B possesses inherent fluorescence properties, fluorescence-based detection was not explored in the present study. Its integration with electronic detection approaches could potentially enhance contrast on complex or multi-coloured backgrounds where conventional cyanoacrylate fuming may yield low-visibility ridge detail. Such fluorescent enhancement could be particularly advantageous for recovering fingerprints from patterned, reflective, or highly textured submerged substrates. Glazed and other reflective surfaces are also expected to yield prints with this formulation; however, the challenge of light reflection necessitates the use of appropriate optical filters and light sources for effective visualisation and photography. Future studies should assess the compatibility of fluorescence-based enhancement within submerged-item recovery workflows.

While the current work utilised fingerprints from a single donor, the chemical composition of glandular secretions—eccrine, apocrine, and sebaceous—remains broadly consistent across individuals, comprising water, amino acids, proteins, fatty acids, glycerides, and metal ions. Since the SPR mechanism primarily targets the lipid component of fingerprint residue, similar performance is anticipated across multiple donors. Nonetheless, minor inter-individual variations may influence development quality; therefore, future studies should validate the formulation on a larger and more diverse donor pool to strengthen the generalisability of results.

To increase real-world applicability, subsequent research should also focus on naturally deposited fingerprints rather than those placed under controlled conditions. Evaluating the reagent’s performance on prints left after routine activities such as handwash or daily tasks (e.g., 2–3 h post-deposition) could provide meaningful insights into operational relevance. Additionally, testing on a broader array of substrates such as high-density polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, and semi-porous materials would help establish its full potential in forensic casework.

The authors consider that future work on advancing the recovery of latent fingerprints from submerged forensic items should focus on extending the duration of submersion and testing the influence of varying water temperatures in subsequent experimental batches. Since temperature can significantly affect bacterial growth, chemical stability, and the rate of fingerprint degradation, systematic evaluation of this parameter is particularly important. Similarly, the influence of complex environments such as acidic, basic, saline, or muddy waters should be examined, as prolonged exposure to such media may affect formulation stability and performance due to chemical interactions or particulate interference.

In sewage water, a substrate-specific effect was observed. No method was used to directly monitor biofilm growth on plastic; however, rapid deterioration of fingerprints on transparency sheets (falling to Grade 1 or lower within 12 h) suggests microbial colonisation, surface roughening, and biofilm deposition. In contrast, glass and stainless steel supported higher-quality prints for longer durations (up to 36–72 h before degradation), highlighting the role of substrate properties in resisting or promoting biofilm formation. Future research could incorporate microscopy or surface analysis to quantify biofilm accumulation and link it to fingerprint degradation kinetics.

Automation of the SPR application or the subsequent quality review process has not yet been implemented in this study; however, its potential advantages are recognised. Automated application could ensure uniform spray coverage and reduce operator-related variability, while automated image analysis could standardise quality grading and improve reproducibility. Future work should explore integrating automated or semi-automated systems—both for reagent application under controlled conditions and for digital quality assessment—to enhance scalability, consistency, and operational utility.

Finally, extrapolating this approach to evidence recovered from soil matrices, where items may remain buried for varying periods, would provide valuable insights into the applicability of this method under complex environmental exposures. Collectively, these directions represent important steps toward refining Phloxine B-based SPR formulation for robust and field-ready fingerprint recovery across diverse forensic scenarios.

Data availability

All data are available with the corresponding author and can be made available upon request.

References

Castelló, A., Francés, F. & Verdú, F. Solving underwater crimes: Development of latent prints made on submerged objects. Sci. Justice. 53 (3), 328–331 (2013).

Rohatgi, R. & Kapoor, A. Development of latent fingerprints on wet non-porous surfaces with SPR based on basic Fuchsin dye. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 6 (2), 179–184 (2016).

Bumbrah, G. S. Small particle reagent (SPR) method for detection of latent fingermarks: A review. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 6 (4), 328–332 (2016).

Trapecar, M. Finger marks on glass and metal surfaces recovered from stagnant water. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2 (2), 48–53 (2012).

Sodhi, G. & Kaur, J. A novel fluorescent small particle reagent for detecting latent fingerprints on wet non-porous items. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2 (2), 45–47 (2012).

Sodhi, G. & Kaur, J. Organic fingerprint powders based on fluorescent phloxine B dye. Def. Sci. J. 50 (2), 213 (2000).

Rohatgi, R., Sodhi, G. & Kapoor, A. Small particle reagent based on crystal Violet dye for developing latent fingerprints on non-porous wet surfaces. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 5 (4), 162–165 (2015).

Jasuja, O., Singh, G. D. & Sodhi, G. Small particle reagents: Development of fluorescent variants. Sci. Justice. 48 (3), 141–145 (2008).

Doibut, T. & Benchawattananon, R. Small particle reagent based on natural dyes for developing latent fingerprints on non-porous wet surfaces. In 2016 Management and Innovation Technology International Conference (MITicon), IEEE, 2016, pp. MIT-225-MIT-228.

Verma, A., Nisha, B. T., Sodhi, G. & Campus, B. Development of latent fingerprints on non-porous surface with fluorescent dye based small particle reagent. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 443–447. (2021).

Kaur, K., Sharma, T. & Kaur, R. Development of submerged latent fingerprints on Non porous substrates with activated charcoal based small partical Reagant. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 14 (3), 388–394 (2020).

Haque, F., Westland, A. D., Milligan, J. & Kerr, F. M. A small particle (iron oxide) suspension for detection of latent fingerprints on smooth surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. 41 (1–2), 73–82 (1989).

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design. Formal analysis, investigation, and methodology were performed by Dimpal Kushwaha. Conceptualisation, Writing - original draft, review and editing, and Supervision were performed by Jaisleen Kaur. Conceptualisation and Supervision were done by Gurvinder Singh Sodhi. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Department of Forensic Science, College of Traffic Management-Institute of Road Traffic Education, India. Informed consent was obtained from participants included in the study (ET/F/2022/15). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Department of Forensic Science, College of Traffic Management-Institute of Road Traffic Education (CTM-IRTE), India. Informed consent was obtained from participants included in the study (ET/F/2022/15). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kushwaha, D., Kaur, J. & Sodhi, G.S. Latent fingerprint recovery on submerged non-porous surfaces using phloxine B-based small particle reagent. Sci Rep 15, 35190 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19190-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19190-5