Abstract

Associative learning, serve as the neurobiological basis of operant conditioning, is essential for adaptive fitness and survival optimization. The visual cue-guided reward acquisition is fundamental in associative learning. However, the pathological memory formed through excessive reward-associated visual cues is also a critical factor contributing to addictive disorders. Thus, it is essential to understand the dynamic mechanisms of visual processing during cue-reward learning. Superior Colliculus (SC) is an important structure that transforms sensory inputs into motor outputs for the purpose of directing orienting behaviors and attention. How SC encodes the association between visual cues and rewarding behavior through specific type of neurons remains unclear. In present study, fiber photometry was used to detect the activity of SC glutamatergic neurons during visual cue-reward associative learning in sucrose self-administration and the intervention targeting SC glutamatergic neurons was conducted to investigate the impact on visual cue-induced reinstatement. We demonstrate that the visual cue related to reward activated SC glutamatergic neurons and chemogenetic inhibition of SC glutamatergic neurons suppresses the visual cue-induced reinstatement. These findings suggest that SC glutamatergic neurons encode reward-related visual cues through associative learning and are necessary for retrieval of the memory which drives the reinstatement, which provides evidence for further understanding of addiction process and maybe a new way to intervene for addicts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Operant conditioning enables organisms to adapt their decision-making based on behavioral outcomes, thereby enhancing environmental adaptation and survival fitness1,2,3. Associative learning, serves as the fundamental neurobiological basis of operant conditioning, depends on the potential of neuronal networks to undergo experience-dependent modifications, such as through learning the association between specific sensory stimulus and rewards4,5. During associative learning, initially “neutral stimuli” in the natural environment acquires reward salience and motivational value through spatiotemporal pairing with rewards, ultimately transforming into “conditioned cue"6. Studies have shown that more than 80% of the external information is transmitted to the brain by the visual system, and the corresponding behavioral response is outputted after processing by the relevant brain areas7,8. Thus, the visual cue-guided reward acquisition is fundamentally important for adaptive survival and development. The pathological memory formed through excessive reward-associated visual cues is also a critical factor contributing to addictive disorders. Patients with addiction exhibit a 150% increase in sensitivity to reward-related cues9 with cue-induced dopamine release exceeding natural rewards by 2–3 fold10,11. However, the dynamic mechanisms of visual processing during cue-reward learning are poorly understood.

The superior colliculus (SC), located in the mammalian midbrain, is an early subcortical brain region12. It is an important brain structure that transforms sensory inputs into motor outputs for the purpose of directing orienting behaviors and attention13. SC has a distinct subzone structure, which can be divided into three layers: superficial layer, middle layer, and deep layer. The superficial layers are predominantly vision-related, receiving direct retinal inputs while also integrating projections from visual cortical areas, while the middle and deep layers integrate inputs from both the superficial SC and multiple other brain regions to orchestrate orienting behaviors, including gaze orientation, spatial attention, and spatial decision-making14. Therefore, SC is also considered as the “integration center” of sensory information15.

Notably, SC is one of the dominant sources of low-processed sensorial information (predominantly visual) reaching the midbrain reward system16,17,18,19. Primate experiments has illustrated how learning and expected reward values affect neuronal activity in SC20. Griggs et al. demonstrate that neurons in SC can discriminate objects based on reward values21. Thus, SC is likely to be involved in reward-related visual cues processing. In addition, responses of deep SC neurons increased if the visual stimulus predicted a reward in the pure passive stimulus model22. Nevertheless, how the associative memory of “visual cue-reward” is encoded by the SC, which specific neurons regulate this process, and direct evidence of its dynamic changes remain to be further investigated.

In the present research, we specifically addressed the role of SC glutamatergic neurons in visual cue associated with rewarding behavior in sucrose self-administration (SA) model by optogenetic and chemogenetic techniques. Firstly, we detected the activity of glutamatergic neurons in SC during sucrose-SA, extinction and reinstatement with fiber photometry, which aimed to determine the response of SC to reward-related visual cue. Secondly, the reversible modulation offered by chemogenetics was applied to inhibit the glutamatergic neurons in SC during visual cue-induced reinstatement, which to verify the role of SC in visual cue-induced reward-seeking behavior. Taken together, the present study demonstrats the critical involvement of SC glutamatergic neurons in encoding the association between visual cue and reward, which may provide further insights into the pathophysiological processes of addiction from the perspective of learning and memory.

Methods and materials

Animals

All experiments were performed with adult C57BL/6J (purchased from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd). The mice 8 weeks old were housed individually in a temperature and Humidity-controlled environment on 12h light-dark cycles (22 °C, 50–60% Humidity, 12:12 h light/dark cycle with Lights on at 8:00 a.m. and Lights off at 8:00 p.m.) and were provided with food and water ad libitum. After all experiments were completed, mice were humanely euthanized via CO₂ inhalation (40% chamber volume/min). The animal study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Beijing Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, and all experimental procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The authors complied with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Viruses

AAV2/9-CaMKIIα-GCaMP6m (titer: 2.84E + 12v g/mL); AAV2/9-CaMKIIα-hM4D(Gi)-EGFP (titer: 4.64E + 12vg /mL).

Drugs

Ketamine and xylazine were received from the Ministry of Public Security. Clozapine nitrogen oxide (CNO, Sigma-Aldrich LLC., St. Louis, USA) was dissolved in 2% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich LLC., St. Louis, USA) to obtain the indicated doses (5 mg/kg of solution). Sucrose (purity > 99%, Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., LTD, China).

Apparatus

The sucrose-SA experiments were conducted in operant test chambers (200 mm × 150 mm × 180 mm, L × W × H). Each test chamber has two nose-poke holes (Aes-110, ID = 2 cm) located 4.5 cm above the floor (Anilab SuperState Version 4.0, Anilab Software & Instruments Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). Anilab 8.52 software was applied to schedule the experimental events and collect the data.

The fiber photometry system was produced by Thinker Tech Nanjing Biotech Limited Co. (Nanjing, China). To record fluorescence signals, 470-nm excitation light was reflected by a dichroic mirror (MD498; Thorlabs, Inc., New Jersey, USA) and focused by a 20 × 0.4 objective. An optical fiber (230mmO.D., numerical aperture (NA) = 0.37, 2 m long) guided the light between the objective and the implanted optical fiber. The GCaMP fluorescence was bandpass filtered (MF525-39; Thorlabs, Inc., New Jersey, USA) and collected by a photomultiplier tube (H10721-210; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). An amplifier was used to convert the photomultiplier tube current output to voltage signals, which were further filtered through a 40-Hz lowpass filter.

Virus injection and implantation

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (25 mg/kg). Animals were then placed in a stereotaxic device (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China) for virus injection and optical fiber insertion. For fiber photometry, the virus AAV2/9-CaMKIIα-GCaMP6m (300nl, Unilateral injection) was injected in SC (the location is AP: −3.7 mm; ML: −0.8 mm; DV: −1.85 mm) (DV measured from the dura surface) at the rate of 30nl/min. The injector remained in place for an additional 10 min. Subsequently, a single optic fiber cannula (QA-HC, length = 2.5 mm, OD = 200 μm, ThinkerTech, Nanjing, China) was implanted unilaterally above the SC (junction between the middle and deep layers) at the following coordinates relative to bregma: AP: −3.7 mm, ML: −0.8 mm, and DV: −1.8 mm (DV measured from the dura surface). Fiber cannulas were secured using instant adhesive (Cat. No. 145401, TONSAN, Beijing, China) followed by the application of acrylic dental cement. For chemogenetic inhibition of SC, the virus AAV2/9-CaMKIIα-hM4D(Gi)-EGFP (300nl per side, Bilateral injection) was injected in the SC. Animals recovered for 3 weeks post-surgery.

Sucrose-SA experiments

Sucrose-SA training: In order to promote the formation of sucrose-SA behavior, the mice were restricted in food for 3 days before the experiment (the food was Limited to 3.0 g per mouse per day, about 80% of the normal food intake) until the end of the training. The mice were trained to self-administer sucrose in the operant test chamber on an FR1 reinforcement schedule. Active pokes of mice resulted in a pump of sugar (10 µl, 10% sucrose) simultaneously coupled with 5s’ cue Light. Inactive pokes resulted in nothing. Lick pokes refer to the Licking behavior of mice which consumes the delivered sucrose solution induced by active pokes. Mice were trained for 1h per day and the number of nose pokes was not limited. When sucrose-SA was established, the experimental animals underwent extinction training.

Extinction: There were no responses to active pokes during extinction. The number of active or inactive pokes of extinction was represented by the average of the last 3 days.

Cue-induced reinstatement: Active pokes resulted in 5s’ cue Light but without sugar and inactive pokes resulted in no responds. Active and inactive pokes were automatically recorded during the 1h’s test.

Fiber photometry

Mice expressing GCaMP6m on glutamatergic neurons of SC were used for the experiments. Recordings were performed during the sucrose-SA training. The instrument was preheated for 30 min before the experiment began. When the Light source kept stable, the power of 405 channel was adjusted to 20–25µW, and the power of 470 channel was adjusted to 40–60 µW. After 15 min of free movement in the cage, the mice were placed in the operant box. The activity of glutamatergic neurons in SC was recorded on the first, sixth and tenth days of SA training, the first and last days of extinction training, and the day of cue priming. The experimental procedure is detailed in Fig. 1A.

Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC during sucrose self-administration. (A) Experimental procedure. Firstly, three weeks post-viral expression, the mice underwent sucrose-SA. Following 14 days of acquisition and 10 days of extinction training, cue-light reinstatement was introduced on day 23. The excitability of glutamatergic neurons in the SC was recorded on the first, sixth, and tenth days of sucrose training, as well as on the first and tenth days of extinction training, and on the day of cue-light reinstatement. (B) Virus expression. a: Schematic of virus injection, b: Fluorescence map of GCaMP expression (Scale: 500 μm). (C) Curve of active pokes in the cue-light group (n = 8) and no-cue light group (n = 6) during SA, mean ± s. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with one repeated measurement followed by Bonferroni test. (D) Curve of inactive pokes in the cue-light group (n = 8) and no-cue light group (n = 6) during SA, mean ± s. (E) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the active poke in the cue-light group. (F) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the active poke in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 8. *P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks. (G) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the active poke in the no cue-light group. (H) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the active poke in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. *P < 0.05, Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance. (I) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the inactive poke in the cue-light group. (J) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the inactive poke in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 8. P>0.05, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks. (K) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the inactive poke in the no cue-light group. (L) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the inactive poke in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance. (M) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the lick poke in the cue-light group. (N) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the lick poke in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 8. P>0.05, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks. (O) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the lick poke in the no cue-light group. (P) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the lick poke in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. P>0.05, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks.

The ΔF/F trajectories were obtained using scripts provided by Thinker Tech Nanjing Biotech Limited Co. (Nanjing, China). The ΔF/F value, representing fluorescence intensity changes around events, was calculated as ΔF/F = (F-F0)/F0, where F is the current fluorescence intensity and F0 is the baseline fluorescence intensity. F0 was defined as the average of the integrated signal over the 1 s period preceding each nose-poke event. The analyzed time window for signal changes spanned 5 s, with fluorescence signals sampled at 100 Hz.

During data processing, the 405 nm excitation channel served as the reference. Using MATLAB, the raw data underwent preprocessing, including motion correction to remove background noise and the airPLS correction algorithm to mitigate photobleaching effects (i.e., the gradual baseline decline caused by prolonged recording of fluorescent signals or fiber autofluorescence). The lambda value for correction was set to 12.

The ΔF/F values are presented as means, with shaded regions indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Results are visualized as heatmaps and line graphs. In the line graphs, the light shading around the traces represents SEM. For heatmaps, all stimulus-aligned results were synchronized to the event onset (time zero). Fluorescence intensity changes are color-coded, with cool tones (e.g., blue) indicating weaker or decreased fluorescence and warm tones (e.g., red) representing enhanced fluorescence intensity.

Selection and analysis of mouse nose-poke events: Each time a mouse poked its nose into a hole was considered as one event (one trail). Since mice would perform multiple nose-poking behaviors in a short period of time, only the events where the mouse did not perform another nose-poke within 6 s after one nose-poke were selected for analysis during the processing. By processing all the nose-poke events that met the requirements for each mouse on the test day, the changes in the neurons of each mouse were obtained. Then, the average trail values of each mouse were integrated to obtain the changes in the neurons of the mice on the test day. Finally, the average trials of different days were integrated to obtain the final line graph and heat map of the neuronal fluctuations.

Chemogenetic Inhibition of glutamatergic neurons in SC

CNO preparation: 5 mg of CNO powder was dissolved in 0.2 ml of DMSO to prepare 25 mg/ml CNO mother liquor, which was stored at −20 °C. The CNO mother Liquor was diluted to 0.5 mg/ml with saline for injection before administration.

After extinction, mice expressing hM4D(Gi) on glutamatergic neurons of SC were randomly given CNO (5 mg/kg) or vehicle (2% DMSO solution) intraperitoneally 20 min before cue priming. After the administration, the mice were allowed to play in their cages. At the beginning of behavioral test, mice were placed in the operant box for cue challenge. The experimental procedure is detailed in Fig. 3A.

Immunofluorescence

To confirm GCaMP6m or hM4D(Gi) expression on glutamatergic neurons in SC, mice injected with GCaMP6m or hM4D(Gi)-EGFP were sacrificed to collect brain sections containing SC. Fluorescent images were obtained with confocal microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Data analysis and statistical tests

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM and analyzed by Sigma Stat.3.5 software. One-way ANOVA was used to compare same index of the same animal before and after the treatment. If the data of each group met the normal distribution but not the spherical assumption, Greenhouse-Geisser was used for post-correction test. If the data of each group did not meet the normal distribution, Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA on Ranks was used for test. Bonferroni test was used for pairwise comparison between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Activity of SC glutamatergic neurons altered during visual cue-reward associative learning

To explore the involvement of SC in visual cue-reward associative learning, the activity of glutamatergic neurons in the junction between the middle and deep layers was examined by fiber photometry in the formation of sucrose-SA. Recordings were performed on the first, sixth and tenth days of sucrose SA training, which is detailed in Fig. 1A. The expression of GCaMP6m on SC glutamatergic neurons is shown in Fig. 1B. Mice with GCaMP6m were randomly divided to two groups (cue-light group and no cue-light group) to trained for sucrose-SA. We found that mice trained with cue-light significantly completed more active pokes than mice trained without cue-light, while the number of inactive pokes had no difference between the two groups (Fig. 1C and D). It indicated that visual cues could enhance reward-seeking behavior. On the first, sixth and tenth days of SA training, the GCaMP6m signal was recorded to reflect the activity of SC glutamatergic neurons. In cue-light group, the activity of SC glutamatergic neurons significantly changed when mice poked the active hole on the 6th and 10th day as the cue-light was trained to associate the reward (Fig. 1E and F). In contrast, inactive pokes (resulted in nothing) and licking behavior had no effect on the activity of SC neurons (Fig. 1I, J, M and N). In no cue-light group, inactive pokes and licking behavior did not significantly modulate neuronal activity in the SC (Fig. 1K, L, O, and P). Interestingly, we found that active pokes in no cue-light group induced the similar trend of SC glutamatergic neurons as well as in cue-light group (Fig. 1G and H). For this phenomenon, we preferred that all reward-related visual cues, including but not limited to cue-light, were effective stimuli for SC which could impact SC neuronal activity. This point is supported by the finding that inactive pokes, which did not match visual cues with reward, had no effect on the activity of SC neurons. These results above suggested that SC glutamatergic neurons involve in the visual cue-reward associative learning and the visual cue reinforce the reward-seeking behavior.

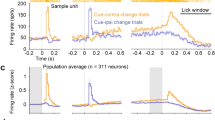

The visual cue activated SC glutamatergic neurons to reinstate reward-seeking

To further investigate the modulation of SC on reward-related cues, we trained mice for extinction and reinstatement. The activity of SC glutamatergic neurons was recorded during these processes. Extinction phase: Active pokes in Extinction-10 decreased significantly compared to Extinction-1(Fig. 2A and G) and inactive pokes had no change (Fig. 2D and J). In cue-light group, the activity of SC glutamatergic neurons gradually extinguished with extinction (compared Extinction-1 with Extinction-10 as shown in heatmap) (Fig. 2C). In no cue-light group, SC glutamatergic neurons remained silent throughout the process (Fig. 2I). Reinstatement phase: In cue-light group, when mice were challenged with cue-light, active pokes remarkably increased in cue priming compared to Extinction-10 (Fig. 2A) and inactive pokes had no change (Fig. 2D), which exhibited an obvious reward-seeking behavior. Meanwhile, SC glutamatergic neurons were activated when re-exposed to the visual cue (Fig. 2B and C). In contrast, inactive pokes (resulted in nothing) had no effect on the activity of SC neurons (Fig. 2E and F). In no cue-light group, though active pokes increased in cue priming compared to Extinction-10 (Fig. 2G), we believe that this phenomenon is caused by the “novelty response” of mice to the cue-light rather than a true reinstatement. And SC glutamatergic neurons did not respond to cue-light (Fig. 2H and I) and inactive pokes (Fig. 2K and L) in no cue-light group, which is consistent with our view above. These results suggested that SC glutamatergic neurons encode the memory for reward-related visual cues through associative learning, which cannot be eliminated by extinction. Upon re-exposure to the same visual cue, SC glutamatergic neurons will be aroused to drive the reinstatement.

Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC during extinction and reinstatement in mice. (A) Active pokes in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 7. *P < 0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance followed by Bonferroni test. (B) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the active poke in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 7. *P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks by Student-Newman-Keuls test. (C) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the active poke in the cue-light group. (D) Inactive pokes in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 7. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance followed by Bonferroni test. (E) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the inactive poke in the cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 7. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance. (F) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the inactive poke in the cue-light group. (G) Active pokes in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. **P < 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks by Student-Newman-Keuls test. (H) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the active poke in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance. (I) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the active poke in the no cue-light group. (J) Inactive pokes in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance followed by Bonferroni test. (K) AUC of GCaMP6m after touching the inactive poke in the no cue-light group, mean ± s, n = 6. P>0.05, One Way Analysis of Variance. (L) Excitability of glutamatergic neurons in SC after touching the inactive poke in the no cue-light group.

Silencing SC glutamatergic neurons inhibited the visual cue-induced reward-seeking reinstatement

Findings above had indicated that SC glutamatergic neurons activated when re-exposed to cue-light associated with reward. Chemogenetic inhibition of SC glutamatergic neurons was employed to verify its regulatory role in the reinstatement induced by the visual cue. The experimental procedure is detailed in Fig. 3A. The expression of hM4D(Gi) on SC glutamatergic neurons is shown in Fig. 3B. Mice with hM4D(Gi) were trained to acquire sucrose-SA and underwent extinction subsequently (Fig. 3C). After extinction, vehicle or CNO was microinjected into SC to observe the reinstatement induced by the visual cue. When mice were injected with vehicle, active pokes significantly increased compared to that in extinction, which exhibited a obvious reinstatement (Fig. 3D). When given CNO, mice displayed less response to cue-light and active pokes remarkably decreased compared to the injection of vehicle (Fig. 3D). The result demonstrated that SC glutamatergic neurons are necessary for retrieval of the “visual cue-reward” associated memory which drives the reinstatement induced by the visual cue.

Effect of inhibiting the glutamatergic neurons in the superior colliculus on cue-induced relapse to sucrose reinstatement. (A) Experimental procedure. Firstly, three weeks post-viral expression, the mice underwent sucrose-SA training. Following 12 days of acquisition and 12 days of extinction, cue-light reinstatement was introduced on day 25. CNO or Vehicle (i.p.) occurred 15 minutes prior to initiation of nose pokes behavior. Subsequent to the completion of the initial reinstatement session, mice underwent additional extinction training (3 days) for cue-light priming with the same method. (B) Virus expression; a: Schematic of virus injection, b: Fluorescence map of hM4Di-EGFP expression (Scale: 500μm). (C) Curve of active and inactive pokes during sucrose-SA. (D) The number of active pokes after inhabiting the glutamatergic neurons in SC during cue-light induced reinstatement. mean ± s, n = 6. *P< 0.05, extinction compared with the corresponding reinstatement group; #P< 0.05, the CNO group compared with the corresponding Vehicle group; two-way ANOVA with one repeated measurement followed by Bonferroni test.

Discussion

Learning the association of a specific sensory stimulus with reward is vital for adaptation to the environment and survival. Neuronal representations of visual stimuli in adult primary visual cortex (V1) have been shown to be modified by previous visual experience4,21,23,24. However, how visual information associated with the rewarding behavioral is encoded remains uncertain. SC is involved in the regulation of a variety of physiological functions, such as visual signal transmission and processing, innate defense response, oriented movement, attention, visual discrimination and so on25,26,27. In the present study, we explored the encoding role of SC glutamatergic neurons in visual cue associated with rewarding behavior in sucrose self-administration. Firstly, we found that visual cue could significantly change SC glutamatergic neurons when associated with reward through fiber photometry. Then, it was recorded that SC glutamatergic neurons could still respond to the visual cue when cue-light was introduced to mice after extinction. Lastly, the result that inhibition of SC glutamatergic neurons hindered the reinstatement induced by the cue verified the necessary role of SC in encoding visual cue associated with rewarding behavior. Our findings demonstrated that SC glutamatergic neurons encode the memory of reward-related visual cues through associative learning, which drives the reinstatement induced by the visual cue.

During the sucrose-SA experiment, by comparing the number of active pokes between the cue-matched and no cue-matched mice, we found that the mice trained with cue had more intense reward craving and more intense reward-seeking behavior. This is consistent with previous researches that reward-related cue exposure can lead to food or drug seeking and excessive consumption28,29,30. The mechanism for this phenomenon may be that as a secondary reinforcement factor, the cue itself has the reward effect and can maintain the compulsive drug-use behavior31,32.

SC is a highly visual structure: A fraction of its inputs is retinal and complemented by inputs from visual cortical areas, including the primary visual cortex12. The middle and deep layers integrate inputs from both the superficial SC and other brain regions to process multiple sensory information. Therefore, we recorded the location at the junction between the middle and deep layers of the SC. Our neuronal activity detection showed that SC glutamatergic neurons responded to visual cues predicting reward after associative learning. Based on fiber photometry recordings, the activity of SC glutamatergic neurons on the 10th day of sucrose self-administration was lower than that observed on the 6th day. Behaviorally, while sucrose self-administration frequencies remained comparable between the 6th day and the 10th day, we observed distinct visual cue responses in SC glutamatergic neurons. Critically, this divergence may cannot be explained by GCaMP signal decay, given its documented stability period (4–6 months with peak efficacy at 6 weeks33 and our adherence to this experimental window. The post-extinction neuronal reactivation shown in Fig. 2 further corroborates the physiological validity of our recordings. We propose this phenomenon reflects a reward-satiety dependent mechanism: During prolonged training, repeated reward consumption may progressively dampen SC neuronal responses to associated cues, while extinction-induced reward omission resets this adaptation, restoring high cue reactivity. This interpretation aligns with established frameworks of reward prediction error signaling5,34 and suggests dynamic, state-dependent modulation of cue salience encoding in the SC. Surprisingly, significant changes in SC glutamatergic neurons were also recorded in the no cue-light group when mice touched the active hole but not the inactive hole. We believe that environmental cues other than cue-light, such as context and pump noise, were associated with reward during sucrose-SA. Thus, despite the absence of cue-light, other reward-related cues are able to activate SC glutamatergic neurons. Subsequent findings supported this point. In the extinction training, we found that SC neurons were no longer activated indicating that the rewarding effects of the context cue had been eliminated. After extinction, only cue-light retained the rewarding effect to activate SC glutamatergic neurons and induced reinstatement. Although the visual cue and active poke co-occur in sucrose self-administration model, we propose two key lines of evidence suggesting that SC neuronal activity changes are specifically associated with the visual cue rather than the nose-poke behavior itself: (1) We also analyzed the changes in SC neurons before and after licking behavior (lick poke) in Fig. 1M. The results showed that the action of mice licking sucrose had no effect on SC activity. This result suggested that the behavior of obtaining a reward itself (including lick pokes and active pokes) may not activate SC glutamatergic neurons. (2) More importantly, following extinction training (during which active pokes no longer delivered either sucrose or light cues), the association between active poking and reward was effectively erased. Under these conditions, active pokes no longer influenced SC neuronal activity (Fig. 2H and I), whereas visual cues alone remained capable of activating SC glutamatergic neurons (Fig. 2B and C). This finding effectively dissociates the confounding effects of active poke behavior and conclusively demonstrates that SC neurons specifically respond to reward-predictive visual cues. Furthermore, existing studies have demonstrated that visual cues can modulate the pathogenesis of addiction and other psychiatric disorders through SC-mediated pathways, which provides supporting evidence for our findings14,22,35,36,37,38,39.

We observed that SC glutamatergic neurons exhibited a dynamic rather than continuous change over the period of cue-light exposure. The SC glutamatergic neurons were activated rapidly at the onset of the cue-light, then rapidly fell back, and finally gradually returned to the resting state. The mice were satisfied with the reward after the cue was presented, which may be the reason for the rest of SC neurons after activation. In contrast, the sustained activation of SC glutamatergic neurons in the reinstatement is due to the absence of reward when cue presentation. In addition to this, there is also evidence that visual stimulus-specific adaptation resulting in response suppression for repetitive stimuli40which is consistent with the quench of SC glutamatergic neurons.

Though SC has been known to respond to visual stimuli, the diversity and functional roles of such responses are unclear. In present study, chemogenetic inhibition of SC glutamatergic neurons interrupted the reinstatement induced by visual cues, which demonstrated that SC glutamatergic neurons are necessary for retrieval of the memory of visual cues related to reward. Our findings are supported by the results of previous studies such as SC activity during context encoding is necessary for choice behavior and transient inhibition of SC plays a causal role in visual perceptual decision-making during an orientation change detection task41,42. Together, these lines of evidence suggest an important role for SC excitatory neurons in visual cue-reward associative behavior, which indicates a target for intervention of addictive disorders caused by visual reward.

why does the SC play a pivotal role in reward-associated cue learning? The possible mechanisms are as follows: The connection from SC to dopamine neurons maybe important for value-based learning36,43. Dopamine neurons are activated by reward, which is a primary reinforcer for behavior44. Dopamine neurons then become sensitive to an event that precedes the reward, which is called conditioned reinforcer45. The sensitivity of SC neurons to good objects, which are based on both stable and flexible values, would be ideal for the conditioned reinforcement21. These hypotheses need to be further validated in the future.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that SC glutamatergic neurons encode the memory for reward-related visual cues through associative learning and are necessary for retrieval of the memory which drives the reinstatement induced by visual cues. It will provide experimental evidence for further understanding of visual cue associated with rewarding behavior and maybe a new way to intervene in visual cue-induced relapse for addicts.

Data availability

Data available on request from the corresponding authors.

References

Soltani, A. & Izquierdo, A. Adaptive learning under expected and unexpected uncertainty. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 635–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0180-y (2019).

Niv, Y. & Langdon, A. Reinforcement learning with Marr. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 11, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.04.005 (2016).

Gershman, S. J. & Daw, N. D. Reinforcement learning and episodic memory in humans and animals: An integrative framework. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68, 101–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033625 (2017).

Henschke, J. U. et al. Reward association enhances stimulus-specific representations in primary visual cortex. Curr. Biol. 30, 1866–1880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.018 (2020).

Schultz, W. Dopamine reward prediction error coding. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 18, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/wschultz (2016).

Tye, K. M. et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature 493, 537–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11740 (2013).

Zhaoping, L. Understanding Vision: Theory, Models, and Data (2014).

Gallivan, J. P. & Culham, J. C. Neural coding within human brain areas involved in actions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 33, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2015.03.012 (2015).

Childress, A. R. et al. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am. J. Psychiatry. 156, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.1.11 (1999).

Koob, G. F. & Volkow, N. D. Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8 (2016).

Volkow, N. D., Michaelides, M. & Baler, R. The neuroscience of drug reward and addiction. Physiol. Rev. 99, 2115–2140. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00014.2018 (2019).

Hafed, Z. M., Hoffmann, K. P., Chen, C. Y. & Bogadhi, A. R. Visual functions of the primate superior colliculus. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 9, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-vision-111022-123817 (2023).

Felsen, G. & Mainen, Z. F. Neural substrates of sensory-guided locomotor decisions in the rat superior colliculus. Neuron 60, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.019 (2008).

Baruchin, L. J., Alleman, M. & Schroder, S. Reward modulates visual responses in the superficial superior colliculus of mice. J. Neurosci. 43, 8663–8680. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0089-23.2023 (2023).

Basso, M. A. & May, P. J. Circuits for action and cognition: A view from the superior colliculus. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 3, 197–226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-vision-102016-061234 (2017).

Comoli, E. et al. A direct projection from superior colliculus to substantia Nigra for detecting salient visual events. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 974–980. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1113 (2003).

May, P. J. et al. Tectonigral projections in the primate: A pathway for pre-attentive sensory input to midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 575–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06596.x (2009).

McHaffie, J. G. et al. A direct projection from superior colliculus to substantia Nigra Pars compacta in the Cat. Neuroscience 138, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.015 (2006).

Takakuwa, N., Kato, R., Redgrave, P. & Isa, T. Emergence of visually-evoked reward expectation signals in dopamine neurons via the superior colliculus in V1 lesioned monkeys. Elife 6 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24459 (2017).

Ikeda, T. & Hikosaka, O. Positive and negative modulation of motor response in primate superior colliculus by reward expectation. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 3163–3170. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00975.2007 (2007).

Griggs, W. S., Amita, H., Gopal, A. & Hikosaka, O. Visual neurons in the superior colliculus discriminate many objects by their historical values. Front. Neurosci. 12, 396. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00396 (2018).

Ikeda, T. & Hikosaka, O. Reward-dependent gain and bias of visual responses in primate superior colliculus. Neuron 39, 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00464-1 (2003).

Goltstein, P. M., Meijer, G. T. & Pennartz, C. M. Conditioning sharpens the Spatial representation of rewarded stimuli in mouse primary visual cortex. Elife 7 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.37683 (2018).

Wilmes, K. A. & Clopath, C. Inhibitory microcircuits for top-down plasticity of sensory representations. Nat. Commun. 10, 5055. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12972-2 (2019).

Beltramo, R. & Scanziani, M. A collicular visual cortex: Neocortical space for an ancient midbrain visual structure. Science 363, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau7052 (2019).

Evans, D. A. et al. A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature 558, 590–594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0244-6 (2018).

Hoy, J. L. & Farrow, K. The superior colliculus. Curr. Biol. 35, R164–R168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.01.022 (2025).

Boswell, R. G. & Kober, H. Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: A meta-analytic review. Obes. Rev. 17, 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12354 (2016).

Brown, R. M., Dayas, C. V., James, M. H. & Smith, R. J. New directions in modelling dysregulated reward seeking for food and drugs. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 132, 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.043 (2022).

Kanoski, S. E. & Boutelle, K. N. Food cue reactivity: Neurobiological and behavioral underpinnings. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23, 683–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09724-x (2022).

Devoto, F., Zapparoli, L., Spinelli, G., Scotti, G. & Paulesu, E. How the harm of drugs and their availability affect brain reactions to drug cues: A meta-analysis of 64 neuroimaging activation studies. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01115-7 (2020).

Venniro, M. et al. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1520–1529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0246-6 (2018).

Geng, J. et al. Chronic Ca(2+) imaging of cortical neurons with long-term expression of GCaMP-X. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.76691 (2022).

Schutt, H. H., Kim, D. & Ma, W. J. Reward prediction error neurons implement an efficient code for reward. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1333–1339. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01671-x (2024).

Awathale, S. N. et al. Neuroplastic changes in the superior colliculus and hippocampus in self-rewarding paradigm: Importance of visual cues. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 890–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-021-02597-2 (2022).

Li, P. Y. et al. The neural circuit of superior colliculus to ventral tegmental area modulates visual cue associated with rewarding behavior in optical intracranial Self-Stimulation in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 842, 137997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2024.137997 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. A superior colliculus-originating circuit prevents cocaine reinstatement via VR-based eye movement desensitization treatment. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwae467. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwae467 (2025).

Najdzion, J. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide and calcium binding proteins immunoreactivity in the superficial layers of the superior colliculus in the Guinea pig: Implications for visual sensory processing. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 79, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchemneu.2016.11.006 (2017).

Vuilleumier, P. Affective and motivational control of vision. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 28, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000159 (2015).

Makino, H. & Komiyama, T. Learning enhances the relative impact of top-down processing in the visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1116–1122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4061 (2015).

Wang, L., McAlonan, K., Goldstein, S., Gerfen, C. R. & Krauzlis, R. J. A causal role for mouse superior colliculus in visual perceptual Decision-Making. J. Neurosci. 40, 3768–3782. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2642-19.2020 (2020).

Hu, F. et al. Prefrontal corticotectal neurons enhance visual processing through the superior colliculus and pulvinar thalamus. Neuron 104, 1141–1152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2019.09.019 (2019).

Redgrave, P. & Gurney, K. The short-latency dopamine signal: a role in discovering novel actions? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 967–975. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2022 (2006).

Hollerman, J. R. & Schultz, W. Dopamine neurons report an error in the Temporal prediction of reward during learning. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1038/1124 (1998).

Kelleher, R. T. & Gollub, L. R. A review of positive conditioned reinforcement. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 5, 543–597. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1962.5-s543 (1962).

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3304201 to R.S.) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7244408).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xingfang Cun: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology. Huimin Zhu: Methodology, Data curation. Ning Wu: Writing–review. Manyi Jing: Writing–review & editing. Rui Song:Investigation, Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional IACUC committee

Animal experiment in this study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Review Committee for the Use of Animals.

Informed consent statement for human subjects

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cun, X., Zhu, H., Wu, N. et al. Superior colliculus encodes the visual cue associated with rewarding behavior in sucrose self-administration in mice. Sci Rep 15, 35171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19192-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19192-3