Abstract

Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3) is a sustainable alternative to Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), capable of significantly reducing CO₂ emissions. However, the mechanisms by which calcined clay affects fresh-state workability are not yet fully understood. In this study, different cements were formulated with variable content of calcined clay to investigate its effect on workability and early hydration. Advanced techniques, including 1H Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (TD-NMR) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), were applied to detect free water in fresh pastes and compared with rheological measurements. Results indicate that increasing the calcined clay content leads to rapid consumption of free water which in turn substantially raises superplasticizer demand, as shown by mortar flow-table tests, and alters paste rheology, as measured by rheometer. Analyses of the first hours of hydration reveal that the available free water can drop dramatically in the presence of calcined clay, providing a clear explanation for the observed increases in yield stress and viscosity. Despite these early rheological challenges, LC3 formulations achieved excellent mechanical performance at 28 days, in some cases surpassing that of OPC CEM I. These findings highlight the dual role of calcined clay in modifying fresh-state behavior and ensuring long-term strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The largest manufactured product on Earth by mass is cement. In combination with water and mineral aggregates it forms fundamental construction materials, like mortar and concrete. Cement has a large carbon footprint as clinker production is responsible for about 8% of the global CO2 emissions. Among different strategies to reduce this footprint, one solution is to increase the use of Supplementary Cementitious Materials, SCMs, as partial replacement of cement clinker1,2. For this reason, European Standard EN 197-5 published in 20213 allows cements of class CEM II/C-M, which contain from 50 to 64% of clinker, while in the previous version of this standard the class CEM II/B required a minimum 65% of clinker3. This paves the path to the use of Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3), a binder whose features have been studied over last few years, showing that this material has promising properties concerning cement reactivity and sustainability4,5.

In particular, it was shown that a kaolinite content of about 40% in clay for preparing a mixture of LC3-50 (50% ground clinker, 30% calcined clay, 15% Limestone, 5% gypsum) is sufficient to give mechanical properties comparable to the reference plain Portland cement from 7 days6,7. The good compressive strengths obtained at 7 and 28 days have been explained by the formation of carboaluminates phases and the porosity refinement8,9. LC3 blends incorporate more aluminum into C-S-H than Portland cement, forming C-A-S-H, with incorporation increasing alongside the kaolinite content in calcined clay10,11. Moreover, the reaction of clinker phases and metakaolin continues at 90 days and even 3 years, even after depletion of portlandite, providing satisfying ultimate mechanical and durability performances12. LC3 was shown to provide satisfying performances also in combination with recycled aggregates13,14.

However, while the introduction of calcined clay in cement formulation is well understood in terms of hydration and mechanical properties, some rheological studies showed that concrete viscosity is affected by binder containing calcined clay and slump retention performance of concrete with LC3 is poorer than concrete prepared with Ordinary Portland Cement15. It was shown that calcined clay is the main factor contributing to the increase of viscosity, yield stress, and initial thixotropy16,17. Some studies highlighted that the yield stress increases with the kaolinitic content of calcined clay, explaining that it reduces the absolute value of zeta potential with direct critical consequences on rheological properties18,19. Other studies investigated the negative impact of calcined clay on superplasticizer efficiency to improve paste workability, suggesting that novel admixtures with improved effectiveness in those cement blends need to be further developed20,21,22,23,24. A recent study analyzed the role of maximum packing of particles and how this presents a physical limitation to further reduce water that cannot be overcome by chemical admixtures exclusively25. Another study combined different methodologies, like rheological measurements, zeta potential’s evaluation and 1H Time Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (TD-NMR), concluding that specific surface area and negative surface charge of calcined clay are the main reason for thixotropic buildup of LC3 paste at 1 hour of hydration26. Despite these works, that contribute to understanding the role of calcined clay on rheological properties of LC3, the knowledge about the role of the water state and its interaction with calcined clay is still lacking and deserves further investigation. Indeed, it is known that one of the primary factors affecting the plastic viscosity and yield value is the water-to-cement ratio27. However, the amount of effective free water remaining after mixing, which directly contribute to the rheology of the cement paste, demands additional research.

A powerful non-destructive and non-invasive method to detect water in porous materials is 1H TD-NMR28. It was demonstrated that TD-NMR reveals water contained in pores of cement pastes29. Different studies were conducted on White Portland Cement (WPC) paste to understand its porosity evolution during hydration30,31, while few studies, always on WPC, analyzed the amount of water chemically bound in hydrates as a function of relative humidity32 or time33. Nevertheless, no studies have applied the 1H TD-NMR to analyse the role of free water to understand rheological properties of fresh materials.

Another method used to analyze water available in cement paste and its evolution over time is Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)34. This original approach provides a direct detection of the available water contained in cement paste by measuring the enthalpy of the melted water after a cycle of freezing35. However, this technique was never applied to understand the consequences of the amount of free water on fresh properties of cement paste.

The aim of this research is to analyze the influence of calcined clay on the fresh state behavior of pastes and mortars, providing experimental evidence that calcined clay rapidly consumes unbound water. We compared our model binders (commercial OPC CEM I and CEM II A/LL) with three low-carbon cements (LC3-50 2:1 with 52.63% CEM I, 31.58% calcined clay and 15.79% limestone powder; LC3-50 1:1 with 52.63% CEM I, 23.68% calcined clay and 23.68% limestone powder; LC3-70 2:1 with 73.68% CEM I, 17.55% calcined clay and 8.77% limestone powder). Characteristics of raw materials are given in the Supplementary Information. Specifically, the analysis of workability was performed by the standard test on mortars (flow table test) with different proportions of calcined clay, limestone and clinker, while rheological measurements were conducted on cement paste. The target workability of mortar was reached by adjusting superplasticizer dosage. Mechanical strength was also assessed to evaluate the suitability of formulated mix designs for real applications. A key revelation of this study is the understanding of the state and availability of free water in LC3 pastes and during the first hours of hydration, by the application of DSC and ¹H TD-NMR. These techniques provide insights into how calcined clay rapidly absorbs unbound water, reducing its availability for fluidification and increasing yield stress. By integrating rheological, thermal, and TD-NMR analyses, this study establishes a direct link between water availability, paste rheology, and workability loss, offering a mechanistic understanding of calcined clay’s role in LC3 systems. The findings contribute to optimizing mix designs and admixture strategies for enhanced performance in sustainable cementitious materials.

Results and discussion

Fresh and hardened mortar’s properties

The amount of superplasticizer (SP) was adjusted to achieve an average diameter of fresh mortar between 210 and 230 mm after 25 drops at the flow table test, according to standard ASTM C143736. Mortar diameters and obtained SP dosage are reported in Fig. 1a and b.

Mortar’s performances: workability and mechanical strength. (a) Mortar diameters obtained at the flow table test. (b) Correlation between superplasticizer dosage required to reach target workability and calcined clay content. (c) Mechanical strength of mortar at 2 and 28 days. The CC content shows high correlation with the superplasticizer dosage, proving the specific impact of this SCM on mortar workability.

The results show that equivalent workability can be obtained using the superplasticizer in different cements. Although the superplasticizer’s dosage increases in blended cements, its percentage is still acceptable, being highly beyond the maximum amount of 5% expressed in the standard EN 93437. It should be noted that superplasticizer dosage increases linearly with the amount of calcined clay (CC) in the binder, as shown in Fig. 1b, pointing out the direct and specific impact of CC on workability. Moreover, the mortar average spread is evolving similarly for all mortars from 0, to 5 to 25 drops. The impact of calcined clay on mortar workability is well documented in the literature. However, the strong correlation observed in this study suggests that specific interaction between water and calcined clay require further investigations. One hypothesis is that CC absorbs or retains water, thereby altering the effective water-to-cement ratio. This effect was investigated in the following parts of this study.

The mortar strength study was performed to show that the formulated mix designs provide enough performance to substitute commercial cements. Compressive strength values of hardened mortars at 2 and 28 days are shown in Fig. 1c. At 2-days, all LC3-based mortars provide lower compressive strength than CEM I, but LC3-70 2:1 that contains 70% clinker exhibits a higher value than CEM II. In the mortars containing LC3 with 50% clinker, a higher percentage of CC with respect to LS leads to higher strength, as expected due to some pozzolanic behaviour of CC in synergy with Limestone. At 28 days, the pozzolanic behavior of calcined clay significantly contributes to the development of compressive strength, and in fact all the LC3-based mortars perform better than the ones based on CEM II. Moreover, LC3 70 2:1 mortar exhibits a compressive strength even higher than mortar manufactured with CEM I, despite containing ~ 30% less clinker.

Rheological properties in respect to the water availability

After the verification of performances of the 5 cement’s type in respect to existing standard, the non-standard investigations were conducted on paste.

Impact of calcined clay on rheological properties

The viscosity and the flow curve of pastes prepared with different cements without superplasticizer is shown in Fig. 2 as a function of the shear rate measured at 10 min of hydration. For parameters of rheological measurements, refer to the Methods section. The calculation of the dynamic yield stress is reported in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

Rheological behavior of paste containing different amount of calcined clay. (a) Viscosity as a function of the shear rate for cement paste prepared with different binders measured at 10 min of hydration. (b) Dynamic yield stress evolution as function of time on pastes prepared with different binder compositions. The CC content is responsible of increased viscosity and reduction of workability retention.

The viscosity values (Fig. 2a) agree with results obtained with the flow table test. Indeed, higher superplasticizer dosage on mortar is required when higher viscosity of cement paste is detected. Moreover, flow curve shapes highlight the specific shear-thinning behaviour of cement pastes, showing that the viscosity increases with the decrease of the shear rate, possibly because of strong interparticle interactions as proposed in38. Specifically, these rheological results underline that the efficiency of shear for breaking up the particle suspension structure varies according to the amount of calcined clay, i.e. higher shear is necessary to allow flow of cement paste with higher calcined clay. This efficiency of shear for breaking up particle structures was shown to be particularly predictive of the ability of concrete to fill complex formworks39. Here, CEM II provides the lowest viscosity, likely because of the presence of limestone particles. CEM I is slightly more viscous than CEM II, but it exhibits much better flow properties than the LC3s. In particular, the higher the calcined clay content, the higher the viscosity of the pastes. Considering that CC is slightly coarser than the two cements and hence the lower flowability cannot be ascribed to the fineness of this material, this behaviour suggests the occurrence of some kind of interactions between water and CC.

The evolution of yield stress as a function of time on paste prepared with different binders is shown in Fig. 2b. For all the binders, the dynamic yield stress increases with time, due to cement hydration and consequent formation of interparticle structure. The two commercial cements, CEM I and CEM II, show similar trend, with CEM II slightly more fluid because of the limestone content decreasing interparticle forces in agreement with the literature40. At 10 min, the LC3s show higher yield stresses in comparison with commercial cements, especially in the case of LC3 50 − 2:1, whose dynamic yield stress was not measurable any more just after 30 min. As LC3 50 − 2:1 is the binder containing the highest amount of CC, these results confirm the results obtained with mortars and highlight that a specific interaction between calcined clay and water directly influences workability of mortar and paste. In terms of dynamic yield stress evolution with time, the samples LC3-50 1:1 and LC3-70 2:1 seem to exhibit a higher loss of flowability in the first 30 min compared to commercial cements, while their trend is similar in the following 30 min. These results were obtained without superplasticizer and the paste had a resting time between one flow curve and the other. This is usually not the case in real concrete that is transported in mixer truck and contains superplasticizer, conditions that promote material’s fluidity and mitigate the structuration of concrete.

Detection of free water in fresh paste by DSC

The thermal analysis by DSC was applied to detect the amount of free water in cement paste at different hydration time (see Fig. 3). The measurement principle relies on freezing the sample and recording the heat released during the melting process, which corresponds to the amount of free water available. The heat flow of water melting peak is decreasing as a function of time, showing that less and less free water is available in paste samples, being consumed during hydration process (Fig. 3a-e). Although the presence of ions in the pore solution may slightly influence the melting temperature of water, the rapid freezing approach used here (at −30 °C) minimizes phase transformations and ensures that any potential effects are consistent across samples, allowing reliable comparisons of binder behavior. It is also possible to see that the peak is reducing over time, possibly due to hydration and to the reduction in average pore size, as it is shown in section showing 1H TD-NMR results.

Water consumption during hydration in binders containing different amount of calcined clay. (a-e) Heat flow as a function of temperature for cement pastes hydrating over 48 h. (f) Free Water Index evolution over 24 h for different binders and materials. (g) Correlation between the FWI at 48 h and the compressive strength at 2 days. The measured free water provides a trace of the hydration kinetics and a consequent prediction of the mechanical strength.

The heat flow during melting (calculated from the area of the peak) allows to calculate the Free Water Index (FWI). The FWI refers to the proportion of water in a mixture (such as cement paste) that is not chemically bound or physically absorbed by the solid particles and is therefore freely available to contribute to the workability or hydration of the mixture. The evolution of the FWI during the first 48 h for different binders is shown in Fig. 3f. FWI is constantly decreasing for all binders, corresponding to the consumption of water during hydration. CEM I consumes free water faster than the other binders due to its higher clinker amount. The hydration kinetic classification according to the curves is: CEM I > CEM II ~ LC3-70 2:1 > LC3-50 2:1 > LC3-50 1:1. DSC test and calculation of the FWI was carried out also for LS and CC, for comparison. Notably, while all the water added to limestone remains in the free form over time (FWI = 100% in Fig. 3f), a significant amount of free water is immediately consumed by CC (FWI ~ 75% at 15 min and later on). This is a result that suggests an immediate consumption of free water by CC, possibly due to the spaces between the nano-layers of calcined clay that generates high specific surface area, as shown in Supplementary Table 4.

The amount of free water at 48 h gives an estimation of the amount of hydrate formed at that time. To validate this approach, and to show that the cycle of water freezing and melting in paste did not provide a major impact on cement hydration, these results were compared to the measured mechanical strength. Coherently, the mechanical strength values at 2 days well correlates to FWI at 48 h (see Fig. 3g). The calculated correlation coefficient is 0.96, indicating the possibility of approximately predicting mechanical strength development starting from the amount of consumed water, corresponding to the formation of hydrates. This result seems to demonstrate the validity of the DSC methodology to analyse cement hydration and the consistency of the data obtained. As far as we know, this method, proposed for the first time by Ridi et al.34 to study cementitious pastes, was never used to quantify unreacted residual water of pastes with limestone, calcined clay or LC3. Especially, the possibility of predicting mechanical strength starting from FWI was never highlighted.

Water detection by 1H TD-NMR

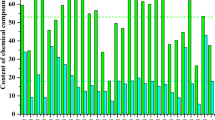

The 1H TD-NMR highlighted the percentage of capillary water and interhydrate water in pastes as a function of the hydration time (Fig. 4). Here, the term interhydrate water refers only to an indication of the pore sizes and water contained in them.

Water detection by 1H TD-NMR in pastes containing different amount of calcined clay during the first hours of hydration. (a-f) Quasi-continuous distribution of T2 relaxation time for cement paste and calcined clay paste. Capillary water (g) and interhydrate water (h) quantified as percentage of total detected water in pastes as function of time determined by tri-exponential fitting of the NMR signal using typical relaxation time attributed to different pore size: ~10 ms for capillary pores, ~ 1 ms for interhydrate water and ~ 0.5 ms for gel pores. However, the signal of gel pores was neglectable in the first 5 h of hydration. (i) Polynomial correlation between % of capillary water and dynamic yield stress. The amount of capillary water detected by NMR at 1 h is shown to play a key role in the rheological behavior of cement pastes at the same hydration time.

TD-NMR results showed that capillary water decreases and interhydrate water increases during hydration, as shown in Fig. 4a-f. Chemically bound water or strongly physically confined water is not detectable with the used experimental setting parameters, while interlayer water (contained in intralayer pores) resulted negligible for all the binders in the investigated time span, hence it was not reported. Indeed, the signal of interlayer water is low for two main reasons: from one side, a relatively small amount of water is confined in pores of this size, 3–5 nm, after 5 h of cement hydration; on the other side, the relaxation times are very short (~ 0.5 ms) for water molecules contained in 3–5 nm pores, and in the first 5 h of hydration it generates a small peak that results neglectable, as expected. For the five cements, the performed analysis showed a very small component of interlayer water, while only calcined clay-based paste gave some significative signal owing to interlayer water, as explained below.

Focusing on 1 h of hydration, CEM I and CEM II show a relatively high percentage of capillary water and low percentage of interhydrate water, while LC3s consume initial capillary water, generating high percentage of pores with size of about 10–20 nm (Fig. 4f, g and h). This data confirms what found by DSC, i.e. that CC immediately consumes most of the capillary water of the mix, leading to the formation of interhydrate water, which is present in higher percentages than the reference cements. This can be better observed through the quasi-continuous NMR transverse relaxation time (T2) distribution of three significant materials (Fig. 4a-f). While most of the water contained in the CEM I paste is in the form of capillary water (T2 = 8–10 ms), CC exhibits mostly interhydrate water (T2 = 1–2 ms), with also a slight peak in the region of interlayer pores (T2 = 0.1–0.2 ms). It should be noted that in CC paste, the terms interhydrate and interlayer refer only to specific pore sizes and do not imply the formation of hydrates, as CC does not hydrate when mixed with water. Moreover, according to the shape of the peak of CC, between 0.1 and 1 ms (Fig. 4f), it seems that spin populations with different relaxation times coexist in the same physical space. This may be due to different local surface relaxivity or to diffusion of water between pores of different size. Consistently, LC3-50 2:1 paste exhibits all the three forms of water, even if the peak of capillary water is slightly shifted but still in the expected range.

Focusing on 5 h of hydration (Fig. 4g and f), CEM I and CEM II provide an intensive consumption of capillary water, that decreases from ~ 80% to ~ 30% (difference 50%), due to hydration, while LC3s slowly consume capillary water, that decreases from ~ 50% or ~ 30% to ~ 10% (maximum difference 40%), thus revealing a relatively slower hydration of LC3s in comparison to commercial cements in the first 5 h of hydration.

The results obtained by DSC and NMR are in good agreement and seem to confirm that part of the water used for the paste preparation disappears because consumed by CC. This water is probably sucked or trapped into clay microstructure, increasing the initial solid volume fraction of paste with drastic consequences on paste rheology.

The correlation between % of capillary water detected by NMR and the measured Dynamic Yield Stress at 1 h of hydration is shown in Fig. 4i. As yield stress increases with solid volume fraction and this increase accelerates when approaching maximum packing fraction41, it is suggested that the water consumed by CC shifts the solid volume fraction of pastes to ranges where small variation in the amount of water have a much stronger impact on yield stress. Consequently, when the solid fraction increases (for instance, when water is consumed by hydration), yield stress increases more in pastes containing calcined clay than in commercial cements because the part of the initial amount of available water was already consumed by CC. The analysis of different types of calcined clay and the effective quantification of the solid volume fraction is not straightforward and requires additional measurements that will be the subject of a future paper.

Conclusion

The present study addresses the topic of the influence of low carbon binder composition on mortar and paste rheology, also quantifying the amount of water consumed in the cement paste in the very beginning of hydration.

The following conclusions can be drawn based on the results obtained:

-

1)

The consumption of free water by calcined clay has been identified as responsible for the significant impact on the rheological properties of mortars and pastes. Indeed, the superplasticizer dosage required to reach target workability is directly proportional to the amount of clay in the mixes. Moreover, rheological measurements on paste showed higher yield stress, higher workability loss over time and increased viscosity at low shear rate when the calcined clay content increases.

-

2)

The compressive strength resistance of LC3-based mortars is lower compared to commercial cements at 2 days but, at 28 days, all the LC3s show higher compressive strength than CEM II and even higher than CEM I for LC3-70 2:1. These exceptional results show that LC3 can serve as a valid low-carbon alternative to CEM II, with potential for replacing CEM I in the future.

-

3)

DSC resulted to be a suitable method to analyse the hydration kinetic of cement paste by detecting the amount of residual water by freezing-melting cycles. The obtained results show different hydration kinetics that can be quantitively reconducted to the measured mechanical strengths.

-

4)

1H TD-NMR was shown to be a valuable method to analyse not only White Portland Cement, but also grey cement and blended cements. Furthermore, 1H TD-NMR was applied to analyse the water consumed due to hydration at the fresh state, while other studies usually started the characterization of cement paste at 1 day of hydration.

-

5)

DSC and TD-NMR agreed in showing that calcined clay contained in LC3 consumes a partial amount of initial available water and drastically increases the solid volume fraction of fresh mixes, directly affecting both the initial workability and the fluidity retention of mortar or paste. This consumption is accompanied by the formation of interhydrate water and also a minimum amount of interlayer water in calcined clay, which seems to be the main reason for the negative effect of CC on workability. However, this rapid water absorption by the CC initially reduces the W/C thus serving as an internal water reservoir for hydration.

In the light of the results obtained with fresh mortars and pastes, one main open issue concerns the interaction between calcined clay and water. Further NMR investigations with a different approach to measure highly confined hydrogens may clarify the amount of water confined in intralayer of calcined clay. Better understanding of how water is trapped by calcined clay microstructure, also investigating different types of calcined clays, will surely help to find solutions to prevent high water demand and workability loss of low carbon cement. Moreover, it is necessary to specifically assess the impact of our findings on the mechanism of action of superplasticizers.

Materials and methods

Materials

The materials used to formulate low-carbon cement blends included:

-

CEM I: Portland cement CEM I 52.5 R.

-

CEM II: CEM II/A-LL with 12% limestone and the same clinker as CEM I.

-

CC: calcined clay.

-

LS: limestone.

The physic-chemical characteristics of the powders and the sand used to formulate pastes and mortars are reported in the Supplementary Information. The two commercial cements, CEM I and CEM II, were used as reference binders. Other three binders were formulated according to the mass proportion indicated in Table 1. The idea behind these formulations is to provide variable amounts of calcined clay and to detect its influence on materials’ performances.

The clinker to prepare LC3 was supplied by inserting CEM I in the mixes and considering the amount of clinker in CEM I equal to 95%. The remaining 5% was considered as calcium sulphate contribution.

The formulation of the binders was performed by mass substitution. Preliminary tests were carried out adopting also the volume substitution, to assess the possible influence of different densities of the powder, but the results obtained in terms of flowability and strength were basically identical, hence the mass substitution was adopted in this study.

Paste preparation was implemented starting from EN 196‑1142 and adapted to Quiet stirred system. The composition was (50.0 ± 0.2) g of binder and (20.0 ± 0.2) g of water. The water and the cement were placed into the bowl and mixed for 1 min at low speed (1800 rpm). Afterwards, the mixing speed was increased till 3000 rpm for 30 s then stopped for 90 s. During this time, the paste adhering to the internal surface of the bowl was removed by means of a scraper. Finally, the mixing continued at high speed (3000 rpm) for 60 s.

The mortar preparation and mixing were conducted in a Hobart mixer, according to standard EN 196-1:2016, using the binder proportion reported in Table 1 and the sand described above. The superplasticizer dosage was adjusted to provide target flowability, as explained in the following.

Methods

In this study, different methods were employed to analyse materials’ properties according to the 5 presented binders. Specifically, mortar was used for flow table tests to assess workability and compressive strength at 2 and 28 days, reflecting practical performance in construction. Paste was used for rheological measurements (viscosity and yield stress), as well as DSC and ¹H TD-NMR analyses, to study the intrinsic properties of the binders, such as water distribution and hydration behavior.

Test on mortar

Mortar flow immediately after mixing was measured by flow table test according to the ASTM C1437-20 standard. The superplasticizer was dosed to reach an average target diameter between 21 and 23 cm after 25 drops.

Compressive and flexural strength were evaluated on mortar cured for 2 and 28 days according to standard EN 196-143.

Rheological measurements on paste

Rheological measurements were conducted in a rheometer RotoVisco 1 from Thermo Haake, with a 4 blades 22 mm geometry and a gap of 8 mm. The cement paste was pre-sheared at 100 s−1 before each flow curve. The flow curve with a decreasing shear rate from 100 to 0.001 s−1, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3, was measured at 10, 30, 60 and 90 min. In the time between two flow curves, the sample was maintained in a period of rest. The yield stress was calculated by estimating the minimum of the flow curve, as reported in the literature39.

Thermal analysis of paste

DSC was used to detect the free water in pastes over 48 h after mixing. Besides the 5 binders, pastes prepared exclusively with calcined clay or limestone (water-to-powder ratio 0.4) were analysed. According to the literature44, the idea is to freeze the free water in a cement paste and to measure the enthalpy of water melting during the subsequent heating. The rapid cooling (less than 1 min) allows to make a photo of the free water contained in the sample at a specific time step. The measured enthalpy is considered a tracer of the amount free water remaining in cement paste. The measurements were conducted using a Q10 DSC TA Instruments, with aluminum hermetic pans. The temperature program was as in the following: equilibrate at −30 °C, isothermal for 1 min, from − 30 °C to −12 °C at 20 °C/min, from − 12 °C to + 35 °C at 4 °C min−1. The sample was kept at 20 °C between one measurement and the other, to allow the continuation of cement hydration. The Free Water Index (FWI) in pastes prepared with the same water-to-binder ratio of 0.4 is calculated, according to34, as follow:

where DHexp is the area of the water melting peak, fw is the weight fraction of water in the paste and DHtheor is the theoretical value of the specific enthalpy of melting water in paste, i.e. 334 J·g−1.

Water detection in paste by 1H TD-NMR

The objective of NMR measurements was to detect the water state in cement pastes. This is accomplished through the determination of the T2 of hydrogen nuclei of the water molecules contained in the sample. Following the model proposed in45, the amount of capillary, interhydrate and interlayer water in pastes was detected. As the relaxation time of hydrogen nuclei depends on water molecules mobility, this information can be related to the pore size in which the water molecules are confined28. NMR equipment allows the detection of the T 2 relaxation curves and the computed values of T2 provide information about water confinement in cement matrix and porous media in general.

The instrumental setup is composed of a permanent magnet (ARTOSCAN, Genova, Italy) with a magnetic field B0 ≈ 0.2 T (corresponding to 1H Larmor frequency ≈ 8 MHz), a 10 mm probe, and an NMR console (Stelar s.r.l., Mede, Italy).

Relaxation time T2 was detected using the Carr–Purcell–Mei-boom–Gill (CPMG) sequence with 512–1024 number of echoes, depending on the saturation level of the samples, with an echo time of 60 µs and 500 scans. Data acquisitions were conducted at 1 h, 2 h and 5 h of hydration and two repeated measurements were performed for each sample at each time step. As the two repeated measurements take around 20 min, the time steps were spaced of at least 1 h to provide significantly different results. Five binders and calcined clay pastes, prepared with deionized water, were analysed. The iron content was calculated as the Fe2O3 mass% in the cement paste and was considered comparable across different samples, ranging between 1.5 mass% and 2.2 mass% in the paste. Thus, relaxation curves should not be appreciably affected by these differences in iron content; therefore, any differences would be attributable to structural differences. Many repetitions of the measurements were performed, but only one representative curve is reported.

The T2 distributions were computed by the software UpenWin46, developed by the NMR group at the University of Bologna. To validate quasi-continuous results, also non-linear fitting was performed. To this aim, scripts in Psi-Plot (Poly Software International, U.S.A) were implemented47. For T2 tri-exponential fitting, the corresponding pore size was assumed in accordance with previous studies carried out on white cement48 as follow: T2 = 8–10 ms correspond to pore size ~ 1000 nm, labelled as capillary water; T2 = 1–2 ms corresponds to pore size 10–20 nm, labelled as interhydrate water; T2 = 0.2–0.5 ms correspond to pore size 3–5 nm, labelled as C-S-H gel pore water.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Scrivener, K. L., John, V. M. & Gartner, E. M. Eco-efficient cements: potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr Res. 114, 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.03.015 (Dec. 2018).

Li, X., Grassl, H., Hesse, C. & Dengler, J. Unlocking the potential of ordinary Portland cement with hydration control additive enabling low-carbon Building materials. Commun. Mater. 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00441-9 (Dec. 2024).

British, S. & Institution EN 197-5:2021 Cement. Part 5, Portland-composite cement CEM II/C-M and Composite cement CEM VI. (2021).

Scrivener, K. et al. Impacting factors and properties of limestone calcined clay cements (LC3). Green. Mater. 7 (1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgrma.18.00029 (Jul. 2018).

Scrivener, K., Martirena, F., Bishnoi, S. & Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (LC3), Dec. 01, Elsevier Ltd. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.08.017

Antoni, M., Rossen, J., Martirena, F. & Scrivener, K. Cement substitution by a combination of Metakaolin and limestone. Cem. Concr Res. 42 (12), 1579–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.09.006 (Dec. 2012).

Avet, F. & Scrivener, K. Investigation of the calcined kaolinite content on the hydration of limestone calcined clay cement (LC3). Cem. Concr Res. 107, 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2018.02.016 (May 2018).

Mathieu, A. N. T. O. N. I. Investigation of cement substitution by blends of calcined clays and limestone THÈSE N O 6001, ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE, Lausanne, (2013). https://doi.org/10.5075/epfl-thesis-6001

Zunino, F. & Scrivener, K. The reaction between Metakaolin and limestone and its effect in porosity refinement and mechanical properties. Cem. Concr Res. 140 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106307 (Feb. 2021).

Avet, F., Boehm-Courjault, E. & Scrivener, K. Investigation of C-A-S-H composition, morphology and density in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3). Cem. Concr Res. 115, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.10.011 (Jan. 2019).

Zunino, F. & Scrivener, K. Increasing the kaolinite content of Raw clays using particle classification techniques for use as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 244 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118335 (May 2020).

Zunino, F. & Scrivener, K. Microstructural developments of limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) pastes after long-term (3 years) hydration. Cem. Concr Res. 153 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106693 (Mar. 2022).

Jan, A. et al. Enhancement of mortar’s properties by combining recycled sand and limestone calcined clay cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 442, 137591. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2024.137591 (Sep. 2024).

Jan, A., Ferrari, L., Mikanovic, N., Ben-Haha, M. & Franzoni, E. Chloride ingress and carbonation assessment of mortars prepared with recycled sand and calcined clay-based cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 456 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139337 (Dec. 2024).

Nair, N., Mohammed Haneefa, K., Santhanam, M. & Gettu, R. A study on fresh properties of limestone calcined clay blended cementitious systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 254 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119326 (Sep. 2020).

Muzenda, T. R., Hou, P., Kawashima, S., Sui, T. & Cheng, X. The role of limestone and calcined clay on the rheological properties of LC3, Cem Concr Compos, vol. 107, Mar. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103516

Ferrari, L. et al. Disclosing the mechanism behind rheological challenges in calcined clay-based cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 492, 142837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.142837 (Sep. 2025).

Sposito, R., Maier, M., Beuntner, N. & Thienel, K. C. Evaluation of zeta potential of calcined clays and time-dependent flowability of blended cements with customized polycarboxylate-based superplasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 308 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125061 (Nov. 2021).

Lorentz, B., Shanahan, N. & Zayed, A. Rheological behavior & modeling of calcined kaolin-Portland cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 307 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124761 (Nov. 2021).

Schmid, M. & Plank, J. Dispersing performance of different kinds of polycarboxylate (PCE) superplasticizers in cement blended with a calcined clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 258 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119576 (Oct. 2020).

Li, R., Lei, L., Sui, T. & Plank, J. Approaches to achieve fluidity retention in low-carbon calcined clay blended cements. J. Clean. Prod. 311 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127770 (Aug. 2021).

Li, R., Lei, L., Sui, T. & Plank, J. Effectiveness of PCE superplasticizers in calcined clay blended cements. Cem. Concr Res. 141 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106334 (Mar. 2021).

Li, R., Lei, L. & Plank, J. Influence of PCE superplasticizers on the fresh properties of low carbon cements containing calcined clays: A comparative study of calcined clays from three different sources. Cem. Concr Compos. 139 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105072 (May 2023).

Ferrari, L., Bortolotti, V., Mikanovic, N., Ben-Haha, M. & Franzoni, E. Influence of calcined clay on workability of mortars with Low-carbon cement. J. NanoWorld. 9, S30–S34. https://doi.org/10.17756/nwj.2023-s2-006 (Sep. 2023).

Flatt, R. J. et al. From physics to chemistry of fresh blended cements. Cem. Concr Res. 172 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107243 (Oct. 2023).

Hou, P. et al. Mechanisms dominating Thixotropy in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3). Cem. Concr Res. 140 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106316 (Feb. 2021).

Taylor, H. F. W. Cement Chemistry (Academic Press, London, 1990).

Coates, G. R., Xiao, L. & Prammer, M. G. NMR Logging Principles and Applications (Halliburton Energy Services Publications, 1999).

Scrivener, K., Snellings, R. & Lothenbach, B. A practical guide to microstructural analysis of cementitious materials. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19074 (CRC Press, 2016).

Muller, A. C. A., Scrivener, K. L., Gajewicz, A. M. & McDonald, P. J. Use of bench-top NMR to measure the density, composition and desorption isotherm of C-S-H in cement paste, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, vol. 178, pp. 99–103, Sep. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.01.032

Muller, A. C. A., Scrivener, K. L., Gajewicz, A. M. & McDonald, P. J. Densification of C-S-H measured by 1H NMR relaxometry. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117 (1), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp3102964 (Jan. 2013).

Nagmutdinova, A., Brizi, L., Fantazzini, P. & Bortolotti, V. Investigation of the First Sorption Cycle of White Portland Cement by 1H NMR, Appl Magn Reson, vol. 52, no. 12, pp. 1767–1785, Dec. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00723-021-01436-w

Briki, Y. et al. Understanding of the factors slowing down metakaolin reaction in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) at late ages, Cem Concr Res, vol. 146, Aug. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106477

Ridi, F., Fratini, E., Luciani, P., Winnefeld, F. & Baglioni, P. Hydration kinetics of tricalcium silicate by calorimetric methods. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 364 (1), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2011.08.010 (Dec. 2011).

Ridi, F., Fratini, E. & Baglioni, P. Fractal structure evolution during cement hydration by differential scanning calorimetry: Effect of organic additives, Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 117, no. 48, pp. 25478–25487, Dec. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp406268p

International, A. S. T. M. ASTM C1437 – 20: standard test method for flow of hydraulic cement mortar. https://doi.org/10.1520/C1437

Publication, B. S. I. S. (ed), EN 934-7: 2024 Admixtures for concrete, mortar and grout. (2024).

Roussel, N., Lemaître, A., Flatt, R. J. & Coussot, P. Steady state flow of cement suspensions: A micromechanical state of the Art. Cem. Concr Res. 40 (1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.08.026 (Jan. 2010).

Ferrari, L., Boustingorry, P. & American Concrete Institute. The Influence of Paste Thixotropy on the Formwork-Filling Properties of Concrete, ACI Special Publication 11th International Conference on Superplasticizers and Other Chemical Admixtures in Concrete Ottawa, vol. 2015-January, no. SP 302, pp. 449–462, (2015). https://doi.org/10.14359/51688116

Flatt, R. J. & Bowen, P. Yodel: A yield stress model for suspensions, Journal of the American Ceramic Society, vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 1244–1256, Apr. (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2005.00888.x

Flatt, R. J. & Bowen, P. Yield stress of multimodal powder suspensions: an extension of the YODEL (yield stress mODEL). J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90 (4), 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2007.01595.x (Apr. 2007).

British Standard & Institution EN 196 – 11:2018 Methods of testing cement Heat of hydration. Isothermal Conduction Calorimetry method. (2018).

British Standards Institution. EN 196-1:2016, Methods of testing cement. Part 1, Determination of strength. London, (2016).

Ridi, F., Fratini, E., Luciani, P., Winnefeld, F. & Baglioni, P. Tricalcium silicate hydration reaction in the presence of comb-shaped superplasticizers: boundary nucleation and growth model applied to polymer-modified pastes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116 (20), 10887–10895. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp209156n (May 2012).

Gajewicz, A. M., Gartner, E., Kang, K., McDonald, P. J. & Yermakou, V. A 1H NMR relaxometry investigation of gel-pore drying shrinkage in cement pastes. Cem. Concr Res. 86, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2016.04.013 (Aug. 2016).

Borgia, G. C., Brown, R. J. S. & Fantazzini, P. Uniform-Penalty lnversion of Multiexponential Decay Data Il. Data Spacing, T 2 Data, Systerriatic Data Errors, and Diagnostics, doi: (2000). https://doi.org/10.1006/jmre.2000.2197

James, F. MINUIT Tutorial, Function Minimization, Geneva. Reprinted from the Proceedings of the 1972 CERN Computing and Data Processing School, Pertisau, 10-24 September 1972 (CERN 72-21) (2004).

Scrivener, K., Snellings, R. & Lothenbach, B. A Practical Guide To Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials 1st edn (Boca Raton, CRC, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1201/b19074

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Heidelberg Materials AG for the financial support. Paolo Carta and Anastasiia Nagmutdinova from University of Bologna are warmly thanked for their support during laboratory tests. Giovanni Ridolfi from Centro Ceramico is thanked for providing the analysis of particle size distribution of calcined clay and limestone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lucia Ferrari: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. Villiam Bortolotti: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis. Nikola Mikanovic: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Mohsen Ben-Haha: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Elisa Franzoni: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrari, L., Bortolotti, V., Mikanovic, N. et al. Understanding workability of low carbon cements through advanced water detection techniques. Sci Rep 15, 35112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19203-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19203-3