Abstract

With global climate change, extremely high temperatures are occurring frequently during summer, seriously affecting development of the apple industry. Heat-shock factors (HSFs) are important signaling proteins for plants to respond to heat stress. However, research on the effects of the apple HSF gene on the regulation of heat-stress tolerance is lacking. In this study, we analyzed the expression and function of MdHSFA2, an HSF, in apples. The MdHSFA2 expression level significantly increased under heat treatment, and Arabidopsis overexpressing MdHSFA2 showed significantly higher tolerance than that in the WT plants. In addition, we found that apple MdGolS4/6 had the highest expression levels among the eight MdGolSs under heat treatment. Using electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) and dual-luciferase assays, we found that MdHSFA2 could directly bind to the MdGols4 promoter region thereby promoting transcription. MdGolS4 overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances heat-stress tolerance. Our findings suggest that MdHSFA2 directly promotes MdGolS4 transcription, thereby enhancing heat-stress tolerance in apples. These results enhance our understanding of heat-stress tolerance mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) is a perennial deciduous fruit tree of the Rosaceae family that is widely planted in temperate regions worldwide because of its high nutritional value, good storage capacity, and long supply period. China is a major producer of apples and has the world’s largest cultivation area and the highest yield1. In recent years, owing to the impact of global climate change, China and the rest of the world have experienced frequent extremely high temperatures during summer, seriously affecting apple production and quality2,3. Therefore, exploring the mechanisms by which apples cope with heat stress is of great significance in solving the current problems in the apple industry.

The heat-shock factor (HSF) is considered a key regulator of high-temperature signals and plays an important regulatory role in plant responses to high-temperature stress4,5,6. HSFs specifically recognize and bind to heat-shock elements (HSE) containing nGAAnnTTCn or nTTCnnGAAn in the downstream target gene promoters7,8. Plant HSFs have been reported to be involved in multiple abiotic stress pathways9,10,11. AtHSFB1 directly regulates AtHSP101 transcription, thereby enhancing drought-stress resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana12. MdHSFA8a interacts with RELATED TO AP2 12 (RAP2.12) to enhance drought-stress tolerance13. AtHSFA6a and OsHSFB2b are involved in the regulation of salt- and drought-tolerance pathways14. Consistent with the naming convention of HSF, its earliest and most widely studied function in plants was heat tolerance. In Arabidopsis, HSFA2, a heat-induced transactivator, plays an important regulatory role in maintaining high expression of downstream heat-shock protein (HSP) genes, thereby significantly enhancing heat resistance15. Both HSFA1d and HSFA1e are located upstream of HSFA2 and activate its transcription, thereby participating in the high-temperature stress response in Arabidopsis. Double knockout of HSFA1d and HSFA1e severely impairs high-temperature tolerance16. In addition, HSFA1, HSFA2B, HSFA3, HSFA9, HSF17, HSF21, HSFB1, and HSFB2 play important roles in heat-stress tolerance17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

The inositol galactoside synthase (GolS) gene is a member of the GT8 glycosyltransferase family and the first key enzyme in the biosynthesis of raffinose oligosaccharides (RFOs). It uses UDP-galactose and myo-inositol as substrates and is responsible for the synthesis of inositol galactoside24. Both inositol galactoside and RFOs have been reported to play important roles in plant abiotic stress responses25,26. Soybean GmGolS2 enhances drought-stress resistance in plants27. Arabidopsis AtGolS2 and poplar PtrGolS3 are involved in the salt stress-resistance pathways28. There are eight GolS genes in apples, among which MdGolS2 is significantly differentially expressed during bud dormancy, with the highest levels of inositol galactoside and RFOs during bud dormancy. MdGolS2 overexpression in Arabidopsis results in higher levels of inositol galactoside and RFOs and enhanced tolerance to water deficit29. ZmGolS2 overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances heat-shock tolerance30.

Currently, the molecular mechanism of the response of apples to heat stress is unclear, and there is a lack of research on the involvement of HSF to heat stress. Therefore, we selected apple MdHSFA2, which was significantly upregulated by heat treatment. MdHSFA2 overexpression in Arabidopsis plants significantly enhanced their heat tolerance compared to that in the wild-type plants. MdHSFA2 can promote transcription of the downstream gene MdGols4, and MdGols4 overexpression in Arabidopsis plants significantly enhanced their heat tolerance compared to that of the wild type. These results indicated that apple MdHSFA2 regulates heat-stress tolerance by controlling MdGols4 transcription.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

‘Nagafu No. 2’ plants were grown on MS medium containing 0.1 mg·L−1 indolebutyric acid and 0.6 mg·L−1 6-benzylaminopurine under long-day conditions (16 h-light/8 h-dark) at 24 °C and were sub-cultured every 45 d. ‘Nagafu No. 2’ apple tissue culture seedlings are obtained by disinfecting the meristematic tissue of ‘Nagafu No. 2’ apple stem tips to obtain the first generation, which is then propagated. Arabidopsis plants (‘Columbia’) were grown on 1/2MS medium under long-day conditions (16 h-light/8 h-dark) at 22 °C. Arabidopsis seeds were previously preserved in our laboratory.

Protein alignment and phylogenetic relationship analysis

We downloaded the HSFA2 protein sequences of these nine plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Malus domestica, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Rosa chinensis, Prunus persica, Ananas comosus, Prunus dulcis, and Glycine max) from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database. A protein sequence alignment of these HSFA2s was performed using DNAMAN software. A phylogenetic tree comprising HSFA2 from nine species was constructed using the MEGA-X program.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from apple and Arabidopsis seedlings using an RNA Plant Plus Reagent Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). cDna was synthesized from the RNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). qRT-PCR analysis was conducted on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The reaction solution contained 10 µL of SYBR Green I Master Mix (CWBIO, Beijing, China), 0.5 µmol·L−1 primers (SANGON BIOTECH, Shanghai, China)(Table S1), and 1 µL of each template, resulting in a total volume of 20 µL. The PCR program was: 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. All the samples were analyzed with three biological replicates, each comprising three technical replicates. Relative gene expression levels were calculated in accordance with the 2−ΔΔCt method31.

Genetic transformation

We used ‘Nagafu No. 2’ apple cDNA as a cloning template and designed specific primers (Table S2) for PCR amplification to obtain CDS sequences of MdHSFA2 and MdGolS4. The CDSs of the MdHSFA2 and MdGolS4 genes were transformed independently into the pCAMBIA2300 vector to generate the 35 S::MdHSFA2 and 35 S::MdGolS4 recombinant plasmid, respectively. The recombinant plasmid was transformed independently into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 cells. Genetic transformations were performed in accordance with published methods for Arabidopsis32. The transgenic Arabidopsis Lines were grown on MS plates supplemented with 50 mg·L−1 kanamycin.

Heat-tolerance assays

The ‘Nagafu No. 2’ plants at 30 d after propagation were used for the Heat treatment(45℃). We collected leaf samples before and at 1, 3, and 6 h after Heat treatment. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C.

The transgenic Arabidopsis seeds were grown in 1/2MS medium and perform heat treatment(45℃ 2 h) at 10 days after germination. And the transgenic Arabidopsis seeds which were grown in soil were perform heat treatment(45℃ 12 h) at 12 days after germination.

Subcellular localization

The CDSs of the MdGolS4 gene was transformed independently into the pCAMBIA2300-EGFP vector to generate the 35 S::MdGolS4-EGFP recombinant plasmid. The recombinant plasmid was transformed independently into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 cells. The GV3101 cells containing the recombinant plasmid was then infiltrated into tobacco leaves. GV3101 cells containing the pCAMBIA2300-EGFP vector (35 S::EGFP) served as the control. After an additional 3 days of growth in the dark, green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals in transformed tobacco leaves were detected using a Leica TCS SP8 SR Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Leica, Germany).

EMSA assays

Construct the MdHSFA2-pGEX-4T-1 fusion vector, obtain the fusion protein through prokaryotic expression, and purify and recover it. The EMSA assay was performed as described by Guo et al.33, following the instruction manual (Thermo Scientific, Rockford).

Dual-luciferase assay

The coding sequence of MdHSFA2 was inserted into a pGreenII 62SK-LUC vector, and approximately 1500-bp sequences upstream of the initiation codons of MdGolS4 were inserted into a pGreenII 0800-LUC vector for a dual-luciferase assay. The dual-luciferase assay was performed as described by Guo et al.33, following the instruction manual (Beyotime, Shanghai).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. Data are reported as means ± SDs. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between treatments as assessed using Student’s t-test at P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test).

Results

Sequence and expression analysis of apple MdHSFA2

Multiple sequence alignment of HSFA2 homologs from 9 plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Malus domestica, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Rosa chinensis, Prunus persica, Ananas comosus, Prunus dulcis, and Glycine max) revealed a universally conserved HSF domain (Fig. 1A), suggesting that HSFA2 is conserved across these plants. A phylogenetic tree of HSFA2 from the 9 plant species was constructed using MEGA-X. MdHSFA2 was most closely related to the HSFA2 of peach and pear, both belonging to the Rosaceae family, whereas they were least closely related to the HSFA2 of pineapple and rice, both of which are monocotyledonous plants (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we exposed apple tissue-cultured seedlings to heat treatment. The expression level of MdHSFA2 was determined at different times during the high-temperature treatment (Fig. 1C). MdHSFA2 was significantly induced by heat, and its expression level was highest 6 h after exposure to heat. Thus, MdHSFA2 may be involved in the heat-resistance pathway in apples.

Bioinformatics and expression analysis of MdHSFA2. (A) The conservative domain of HSFA2 in 9 plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Malus domestica, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Rosa chinensis, Prunus persica, Ananas comosus, Prunus dulcis, and Glycine max). (B) The phylogenetic tree of HSFA2 from 9 species. (C) Analyses of MdHSFA2 expression levels in ‘Nagafu No. 2’ tissue-cultured seedling leaves at 0, 1, 3, and 6 d under heat treatment conditions. Different letters represent significant differences determined by analysis of variance (P < 0.05).

Overexpression of MdHSFA2 enhances heat-stress tolerance

To study the heat-stress tolerance phenotype of MdHSFA2, we performed Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of MdHSFA2 into Arabidopsis. We then exposed MdHSFA2-OE transgenic plants to high-temperature (45 °C) conditions (Fig. 2A, S1A). The survival rates of MdHSFA2-OE lines were significantly higher than those of WT lines (Fig. 2B, S1B). We also performed genomic PCR (Figure S1C) and qRT-PCR (Fig. 2C) to confirm the presence of the transgene in MdHSFA2-OE lines. Moreover, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of Arabidopsis HSPs (AtHSP70 and AtHSP70T) and GolSs (AtGolS1 and AtGolS2) (Fig. 2D) and found that their expression levels in transgenic A. thaliana increased under high-temperature conditions compared to normal growth conditions. These results indicated that MdHSFA2 enhanced plant heat-stress tolerance.

MdHSFA2 enhanced heat-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. (A) Phenotype of the MdHSFA2-OE Arabidopsis lines for heat-stress tolerance. Bar = 1cm. (B) Statistical analysis of survival rate of WT and MdHSFA2-OE Arabidopsis lines after the heat treatment. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of MdHSFA2 expression in Arabidopsis samples. Different letters represent significant differences determined by analysis of variance (P < 0.05). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of two AtHSPs and two AtGolSs expression in Arabidopsis samples after heat treatment. Asterisks denote significant differences as determined by a t-test (*P < 0.05)

Expression analysis of apple MdGolSs after heat treatment

To explore the function of MdGolSs in heat-stress tolerance, we studied the expression levels of MdGolSs family genes under heat stress (Fig. 3). Except for MdGolS2, which showed decreased expression under heat stress, the expression levels of all the other MdGolSs showed an increasing trend. Notably, the expression level of MdGolS4/6 increased the most after high-temperature treatment. The expression level increased more than 50 times after treatment for 1, 3, and 6 h, and the expression level increased the most after treatment for 3 h, exceeding 100 times. This suggests that MdGols4/6 may play an important role in heat-stress tolerance in apples.

Apple MdHSFA2 directly binds to the MdGols4 promoter

We cloned and analyzed the MdGols4 promoter region and identified potential binding sites for HSFs (Fig. 4A). To verify whether MdHSFA2 directly binds to the MdGols4 promoter, we cloned a 600 bp MdHSFA2 region containing the HSF protein domain into the pGEX-4t-1 vector and performed prokaryotic expression and protein purification to obtain the MdHSFA2200AA-GST fusion protein. Next, we labelled the potential binding sites of the MdGols4 promoter with biotin and conducted EMSA experiments. The EMSA results indicated that MdHSFA2 could directly bind to the MdGols4 promoter region (Fig. 4B). Moreover, we conducted a dual-luciferase assay and found that the LUC/REN ratio of tobacco leaves co-injected with MdHSFA2−62SK and MdGols4-LUC was significantly higher than that of leaves co-injected with 62SK and MdGols4-LUC (Fig. 4C). This indicates that MdHSFA2 promotes MdGols4 transcription.

MdHSFA2 directly promotes transcription of MdGolS4. (A) Diagram of the MdGolS4 promoter sequence used for promoter activity and EMSA analysis. The potential MdHSFA2-binding sequence (core ‘GAAnnTTC’ element) for the EMSA is marked by red. (B) EMSA of MdHSFA2 with the MdGolS4 promoter. + and − indicate the presence and absence of recombinant MdHSFA2::GST, biotin-labeled probe, or cold probe, respectively. Cold probe concentrations were tenfold (10×), 20-fold (20×), or 50-fold (50×) those of the labeled probes. The full-length membrane image of EMSA is shown in Figure S3. (C) MdHSFA2 activated LUC expression that was controlled by the promoters of MdGolS4.

Apple MdGolS4 sequence and subcellular localization analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of GolS4 homologs from 9 plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Malus domestica, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Rosa chinensis, Prunus persica, Ananas comosus, Prunus dulcis, and Glycine max) revealed a universally conserved PLN00176 domain (Fig. 5A), suggesting that GolS4 is conserved across these plants. A phylogenetic tree of GolS4 from these 9 plant species was constructed using MEGA-X. MdGolS4 was most closely related to GolS4 of peach and pear, both belonging to the Rosaceae family, whereas it was least closely related to GolS4 of pineapple and rice, both belonging to the monocotyledonous plant family (Fig. 5B).

Bioinformatics and Subcellular localization analysis of MdGolS4. (A) The conservative domain of GolS4 in 9 plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Malus domestica, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Rosa chinensis, Prunus persica, Ananas comosus, Prunus dulcis, and Glycine max). (B) The phylogenetic tree of GolS4 from 9 species. (C) Subcellular localization analysis of MdGolS4. The upper panel shows 35S::EGFP, the second is 35S::MdGolS4-EGFP. Bar = 50µm.

The subcellular localization of MdGolS4 was studied by introducing 35 S::MdGolS4-GFP into tobacco leaves. Tobacco leaves infiltrated with an empty vector displaying the instantaneous expression of 35 S::GFP were used as controls. In tobacco leaves expressing MdGolS4-GFP, fluorescence signals were observed in the nucleus and cytoplasm. In contrast, a fluorescence signal was detected in the control tobacco leaf cells expressing 35 S::GFP (Fig. 5C). These results indicated that MdGolS4 was localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm.

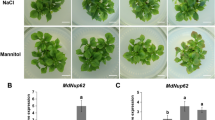

MdGolS4 overexpression enhances heat-stress tolerance

To study the heat-stress tolerance phenotypes of MdGols4, we performed an Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of MdGols4 into Arabidopsis. We then exposed MdGols4-OE transgenic plants to high-temperature (45 °C) conditions (Fig. 6A, S2A). The survival rates of MdMdGols4-OE lines were significantly higher than those of WT lines (Fig. 6B, S2B). We also performed genomic PCR (Figure S2C) and qRT-PCR (Fig. 6C) to confirm the presence of the transgene in MdGols4-OE lines.

MdGolS4 enhanced heat-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. (A) Phenotype of the MdGolS4-OE Arabidopsis lines for heat-stress tolerance. Bar = 1cm. (B) Statistical analysis of survival rate of WT and MdGolS4-OE Arabidopsis lines after the heat treatment. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of MdGolS4 expression in Arabidopsis samples. Different letters represent significant differences determined by analysis of variance (P < 0.05).

Discussion

HSFs integrate environmental heat cues into plants and provide information about cellular health by interacting with protein networks, thereby regulating response intensity4. This indicates that HSFs play crucial roles in plant responses to heat stress. HSFA1 positively regulates heat resistance in tomatoes, whereas the expression of HSFA2 depends on HSFA1. Silencing the expression of HSFA2 in protoplasts after HSFA1 transcription restores heat resistance18. In Arabidopsis, HSFA3 directly targets the upregulation of HSP18.1-Cl and HSP26.5-MII expression, and its deletion mutants and RNAi lines significantly reduced heat tolerance19, whereas overexpression of HSFA1a in Arabidopsis promoted the expression of HSP18.2 and HSP70, and enhanced heat resistance34. HSFA1b directly targets OPR3 expression, thereby regulating heat-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis and wheat via the methyl jasmonate signaling pathway35. This study also reached the same conclusion: MdHSFA2 overexpression in Arabidopsis lines significantly improved heat tolerance compared to that in the WT plants. Numerous studies have shown that HSPs play an important role in the regulation of plant tolerance to heat stress. For instance, under heat-stress conditions, HSP17.6B overexpression increased root elongation, improved the plant survival rate, and reduced electrolyte leakage, thereby enhancing heat tolerance36. In cotton, AsHSP70 overexpression in plants significantly enhanced heat tolerance37. There are also reports on the role of GolSs in the regulation of plant tolerance to heat stress30,38. Therefore, we performed qPCR analysis to determine AtHSP70, AtHSP70T, AtGolS1, and AtGolS2 expression levels in Arabidopsis. The results showed that the expression levels of the four genes in MdHSFA2-OE lines were significantly higher than those in WT plants under heat treatment. These results indicated that MdHSFA2 positively regulates plant tolerance to heat stress.

GolS is a key enzyme involved in the synthesis of raffinose in plants and various abiotic stress pathways, including heat-stress responses. Arabidopsis AtGolS2 is regulated by H3K9 demethylase, JMJ27. Under drought stress, JMJ27 reduced the H3K9me2 level of AtGolS2 to enhance its transcription and improve plant drought-stress resistance39. Arabidopsis overexpressing MdGolS2 had higher levels of inositol galactoside and RFO and enhanced water deficit tolerance29. Under salt stress, transgenic poplar lines overexpressing Arabidopsis AtGolS2 and poplar PtrGolS3 showed higher levels of soluble sugars and other stress-related metabolites (proline, salicylic acid, and phenylalanine), and significantly improved salt-stress resistance28. ZmGolS2 overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances heat-shock tolerance30,38. ZmHSFA2 can directly bind to the ZmGolS2 promoter, and ZmHSFA2 overexpression in Arabidopsis increases AtGolS1 and AtGolS2 expression and enhances plant tolerance to heat stress40. In addition, Arabidopsis AtHSFA3 can directly bind to the promoters of AtGolS1 and AtGolS241. These indicate that AtGolS is located downstream of AtHSF in Arabidopsis. Therefore, we speculate that MdGolS in apples is located downstream of the MdHSF genes. To test this hypothesis, we first measured the expression levels of eight MdGolS genes in apples subjected to high-temperature treatment. The expression level of MdGolS4/6 increased the most after heat treatment. We then analyzed the promoter region of MdGolS4 and identified potential binding sites for HSF. Subsequently, we conducted EMSA and confirmed that MdHSFA2 directly targets the MdGolS4 promoter region. We conducted a dual-luciferase assay and found that MdHSFA2 promoted MdGolS4 transcription. This indicates that MdHSFA2 may enhance heat-stress tolerance in apples by promoting MdGolS4 expression. To verify this hypothesis, we overexpressed MdGolS4 in Arabidopsis lines (MdGolS4-OE) and performed heat-stress treatment experiments. We found that MdGolS4-OE Arabidopsis lines had significantly higher heat-stress tolerance than the WT lines after heat-stress treatment. This is consistent with previous findings.

Based on the above experimental results, we constructed a model for apples to cope with heat stress through MdHSFA2, which induces MdHSFA2 expression, leading to MdHSFA2 protein accumulation. HSFA2 protein directly binds to the MdGolS4 promoter, promoting MdGolS4 transcription, thereby enhancing heat-stress tolerance in apples (Fig. 7).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Wang, J. & Liu, T. Spatiotemporal evolution and suitability of apple production in China from climate change and land use transfer perspectives. Food Energy Secur. 11(3), e386 (2022).

Yao, F., Song, C., Wang, H., Song, S. & Bai, T. Genome-wide characterization of the hsp20 gene family identifies potential members involved in temperature stress response in Apple. Front. Genet. 11, 609184 (2020).

Zhou, B. et al. Dwarfing Apple rootstock responses to elevated temperatures: a study on plant physiological features and transcription level of related genes. J. Integr. Agr. 15 (5), 1025–1033 (2016).

Bakery, A. et al. Heat stress transcription factors as the central molecular rheostat to optimize plant survival and recovery from heat stress. New. Phytol. 244, 51–64 (2024).

Myers, Z. A. et al. Conserved and variable heat stress responses of the Heat Shock Factor transcription factor family in maize and Setaria viridis. Plant. Direct 7(4), e489 (2023).

Schulz-Raffelt, M., Lodha, M. & Schroda, M. Heat shock factor 1 is a key regulator of the stress response in chlamydomonas. Plant. J. 52, 286–295 (2007).

Littlefield, O. & Nelson, H. C. M. A new use for the ‘wing’ of the ‘winged’ helix-turn-helix motif in the hsf-dna cocrystal. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 (5), 464–470 (1999).

Maria, C. A., Sunkel, C. E. & Moradas-ferreira, P. Rodrigues-pousada, C. Properties and partial characterization of the heat-shock factor from tetrahymena pyriformis. Eur. J. Biochem. 194, 331–336 (1990).

Fragkostefanakis, S., Roth, S., Schleiff, E. & Scharf, K. D. Hsfs and Hsps for improvement of crop thermotolerance. Plant. Cell. Environ. 38, 1881–1895 (2015).

Li, F. et al. Chrysanthemum CmHSFA4 gene positively regulates salt stress tolerance in Transgenic chrysanthemum. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 16, 1311–1321 (2018).

Nishizawa, A. et al. Arabidopsis heat shock transcription factor A2 as a key regulator in response to several types of environmental stress. Plant. J. 48, 535–547 (2006).

Zheng, L. et al. The heat shock factor HSFB1 coordinates plant growth and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant. J. 121, e17258 (2025).

Wang, N., Liu, W., Yu, L., Guo, Z. & Chen, X. Heat shock factor a8a modulates flavonoid synthesis and drought tolerance. Plant. Physiol. 184 (3), 1273–1290 (2020).

Hwang, S. M. et al. Role of AtHsfA6a under salt and drought conditions. Plant. Cell. Environ. 37, 1202–1222 (2014).

Charng, Y. Y. et al. A heat-inducible transcription factor, hsfa2, is required for extension of acquired thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 143 (1), 251–262 (2007).

Nishizawa, A. et al. HsfA1d and HsfA1e involved in the transcriptional regulation of HsfA2 function as key regulators for the Hsf signaling network in response to environmental stress. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 52 (5), 933–945 (2011).

Ikeda, M., Mitsuda, N. & Ohme-Takagi, M. Arabidopsis hsfb1 and hsfb2b act as repressors of the expression of heat-inducible Hsfs but positively regulate the acquired thermotolerance. Plant. Physiol. 157 (3), 1243–1254 (2011).

Mishra, S. K. In the complex family of heat stress transcription factors, HsfA1 has a unique role as master regulator of thermotolerance in tomato. Gene Dev. 16 (12), 1555–1567 (2002).

Schramm, F. et al. A cascade of transcription factor DREB2A and heat stress transcription factor HsfA3 regulates the heat stress response of Arabidopsis. Plant. J. 53, 264–274 (2008).

Song, N. et al. ZmHSFA2B self-regulatory loop is critical for heat tolerance in maize. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 23, 284–301 (2025).

Zhang, H. et al. Heat shock factor ZmHsf17 positively regulates phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase ZmPAH1 and enhances maize thermotolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 76 (2), 493–512 (2025).

Zinsmeister, J. et al. The seed-specific heat shock factor a9 regulates the depth of dormancy in medicago truncatula seeds via Aba signalling. Plant. Cell. Environ. 43 (10), 2508–2522 (2020).

Xie, Y. & Ye, Y. Maize class c heat shock factor zmhsf21 improves the high temperature tolerance of Transgenic Arabidopsis. Agriculture 14 (9), 1524 (2024).

Yin, Y., Mohnen, D., Gelineo-Albersheim, I., Xu, Y. & Hahn, M. G. Glycosyltransferases of the GT8 Family. In Annual Plant Reviews online, P. Ulvskov (Ed.), (2011).

Elsayed, A. I., Rafudeen, M. S., Golldack, D. & Weber, A. Physiological aspects of raffinose family oligosaccharides in plants: protection against abiotic stress. Plant Biol. 16 (1), 1–8 (2014).

Krasensky, J. & Jonak, C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 63 (4), 1593 (2012).

Qiu, S. et al. Overexpression of GmGolS2-1, a soybean galactinol synthase gene, enhances Transgenic tobacco drought tolerance. Plant. Cell. Tiss Org. 143 (3), 507–516 (2020).

Liu, L., Wu, X., Sun, W., Yu, X. & Zhu, Q. Galactinol synthase confers salt-stress tolerance by regulating the synthesis of galactinol and raffinose family oligosaccharides in Poplar. Ind. Crop Prod. 165 (7), 113432 (2021).

Falavigna, V. S. et al. Evolutionary diversification of galactinol synthases in rosaceae: adaptive roles of galactinol and raffinose during Apple bud dormancy. J. Exp. Bot. 5, 1247–1259 (2018).

Gu, L., Han, Z., Zhang, L., Downie, B. & Zhao, T. Functional analysis of the 5′ regulatory region of the maize GALACTINOL SYNTHASE2 gene. Plant. Sci. 213, 38–45 (2013).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant. J. 16, 735–743 (1998).

Guo, Z. H. et al. The NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2 transcription factor ppnac.a59 enhances pperf.a16 expression to promote ethylene biosynthesis during Peach fruit ripening. Hortic Res, (8), 209 (2021).

Qian, J. et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis HsfA1a enhances diverse stress tolerance by promoting stress-induced Hsp expression. J. Mol. Struct. 13 (1), 1233–1243 (2014).

Tian, X. et al. Heat shock transcription factor A1b regulates heat tolerance in wheat and Arabidopsis through OPR 3 and jasmonate signalling pathway. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 18 (5), 1109–1111 (2020).

Tawab, F., Munir, I., Ullah, F., Iqbal, A. & Over-expressed HSP 17.6B, encoding HSP20-like chaperones superfamily protein, confers heat stress tolerance in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Pak J. Bot. 51 (3), 855–864 (2019).

Batcho, A. A., Sarwar, M. B., Rashid, B., Hassan, S. & Husnain, T. Heat shock protein gene identified from Agave Sisalana (AsHSP70) confers heat stress tolerance in Transgenic cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Theor. Exp. Plant. Phys. 33, 141–156 (2021).

Gu, L. et al. ZmGOLS2, a target of transcription factor ZmDREB2A, offers similar protection against abiotic stress as ZmDREB2A. Plant. Mol. Biol. 90, 157–170 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. JMJ27-mediated histone H3K9 demethylation positively regulates drought-stress responses in Arabidopsis. New. Phytol. 232, 221–236 (2021).

Gu, L. et al. Maize HSFA2 and HSBP2 antagonistically modulate raffinose biosynthesis and heat tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant. J. 100, 128–142 (2019).

Song, C., Chung, W. S. & Lim, C. O. Overexpression of heat shock factor gene hsfa3 increases galactinol levels and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells. 39 (6), 477–483 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. X., and C. Z. conceived and designed the experiment. M. L., X. Z., and D. Z. performed the experiment. J. W., L. Z., X. X., X. Z., M. L., and C. Z. analyzed the data. M. L. and C. Z. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Zhang, X., Zuo, D. et al. MdHSFA2 enhances heat stress tolerance through promoting the MdGolS4 transcription in apple. Sci Rep 15, 35436 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19247-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19247-5