Abstract

Unexpected failures in rotating machinery can cause costly downtime and safety hazards in industrial systems, highlighting the need for accurate and robust fault diagnosis. However, fault-related signals are often weak and easily obscured by noise, making reliable diagnosis challenging in real-world environments. To address this, we propose Time-frequency and time-series dual-branch fusion network(TFDFNet), a novel dual-branch deep learning model designed to improve fault classification performance under noisy and complex conditions. The model combines two complementary types of information: time-frequency representations derived from continuous wavelet transform and raw time-sequence data captured through sliding-window sampling. A Swin Transformer is used to extract deep features from time-frequency images, while a specially designed module called Gated attention block(GABlock) learns key temporal patterns from the sequence data. These features are fused using a cross-attention mechanism to enhance fault-related information. Extensive experiments on two public bearing fault datasets (CWRU and Ottawa) show that TFDFNet achieves outstanding accuracy, even under severe noise interference. The model reaches up to 100% accuracy on CWRU and 99.44% on Ottawa, and consistently outperforms existing convolutional neural network (CNN) baselines. These results demonstrate the practical potential and robustness of TFDFNet for intelligent fault diagnosis in industrial applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of modern industry, rotating machinery is increasingly utilized across various fields. Bearings, as key components of these systems, operate under harsh conditions, including high loads, temperatures, and speeds. They are widely employed in industries such as wind power, aerospace, and railroad transportation1. However, in these extreme environments, bearings are highly susceptible to vibration, impact, and wear, making them the most vulnerable part of the machinery. Bearing failures not only lead to equipment damage but can also result in significant economic losses and safety risks. Therefore, timely fault diagnosis is critical to enhance equipment reliability and ensure safety. Since vibration signals in industrial environments are often contaminated by noise, and fault features are weak and difficult to extract, achieving accurate and robust fault diagnosis in such complex settings remains a significant challenge2,3. The issue of fault diagnosis has attracted considerable attention from researchers. Currently, bearing fault diagnosis methods are primarily divided into signal-based and data-driven approaches4.

Signal-based fault diagnosis

Signal analysis methods extract bearing fault features by processing the raw signal in the time domain, frequency domain, or time-frequency domain, thus enabling fault diagnosis. Especially in complex noise environments, many advanced signal processing techniques are used to achieve more accurate fault diagnosis, such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), Wavelet Transform (WT), Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)5,6,7,8,9,10.These methods effectively reduce noise interference and separate sensitive features, thereby reflecting the fault condition of the bearing in strong noise environments.

For example, Chen et al. proved their effectiveness in fault diagnosis through an improved integrated EMD and Hilbert square demodulation method11; Bin et al. proposed a method combining wavelet packet decomposition and EMD for extracting the fault eigenfrequencies12; and Jiang et al. introduced the neighboring singular value ratio based on the singular value decomposition concept and combined it with Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to realize the identification of bearing faults13; Although the methods based on signal analysis can improve the accuracy of fault diagnosis to a certain extent, they have limitations in dealing with high-noise signals under complex operating conditions due to the fact that the bearing signals are usually highly nonlinear and nonsmooth. In addition, they usually rely on manual feature extraction, which makes it difficult to comprehensively capture fault information and affects the robustness and generalization ability of diagnosis.

Data-driven fault diagnosis

With the development of deep learning technology, data-driven fault diagnosis methods based on data have gradually become a research hotspot.These methods can automatically learn complex features in vibration signals and show excellent performance in fault classification and identification14,15. Compared with traditional methods, data-driven methods do not rely on excessive a priori knowledge and have strong adaptive capability.Zhang et al.proposed a subset-based deep self-encoder feature learning model, developed an adaptive fine-tuning operation hey enhanced feature learning, and used a particle swarm algorithm to optimize the key parameters16. Wang et al.proposed an industrial motor bearing fault diagnosis algorithm based on multi-local model decision conflict resolution (MLMF-CR), which, after the initial characteristic signal selection and cleanup of industrial motor bearing vibration and current signals, digs deeper into the characteristics of the bearing signals in each fault state through the local fault diagnosis model based on bidirectional long- and short-term memory network (Bi-LSTM). Information to form a local diagnosis, and after making a decision, use the evidence theory for fusion17. Ma et al.proposed a new deep neural network by combining the advantages of CNN and long-term memory. The contribution of this method is the use of CNNs to process signals in the joint time-frequency domain, preserving feature information18. Dibaj et al. were able to identify unanticipated and untrained composite fault states19 by using a CNN model trained with three classes of healthy states, single bearing faults, and single gear faults in conjunction with probabilistic conditions.

Despite the significant results of deep learning-based methods in bearing fault diagnosis, they still face the impact of noisy environments on model robustness. Traditional convolutional neural networks mainly process one-dimensional signals, which are limited by a small receptive field and may lose critical information. In addition, current methods mainly rely on single-modal data and cannot fully utilize multimodal information for diagnosis, resulting in poor generalization ability in strong noise environments20,21,22,23,24. To address these challenges, researchers have developed various dual-/multi-channel and multimodal fusion models.For instance,Cross-domain time-frequency adaptive fusion network(CDTFAFN)25 introduced a coarse-to-fine dual-scale attention mechanism to fuse raw acoustic and vibration signals, achieving robust performance in noisy environments. Chen et al.26 proposed a self-supervised framework that jointly leverages original time-series signals and their Fourier-transformed counterparts to enhance performance under few-label conditions. These studies highlight the effectiveness of dual-stream architectures and attention-based modeling for robust and generalizable fault diagnosis.Multi-information fusion deep ensemble learning network(MIFDELN)27, which employs weighted sensor signal fusion and cross-scale attention modules to improve feature discriminability under noisy conditions; and Multi-sensor residual convolutional fusion network(MRCFN)28, which combines residual modules and global perception mechanisms to effectively extract features in small sample and high-noise scenarios. For instance, Jiang et al.29 proposed a deep convolutional multi-adversarial adaptation network with correlation alignment for cross-condition fault diagnosis, while Zhang et al.30 developed a multi-scale deep feature memory and recovery network tailored for multi-sensor fault diagnosis under channel-missing scenarios. These works not only present advanced architectures but also provide detailed parameter configurations, which inspire the way we present and clarify the setup of TFDFNet in this study. In addition, dual-channel technology has demonstrated great potential in other domains. For example, Chen et al.31 constructed a dual-channel SE-3DUNet-based detection model for cerebral aneurysm screening in the field of clinical medicine, which demonstrated a lower false alarm rate and better sensitivity in a noisy environment. In the field of instrumentation, Zhang et al.32 realized multi-signal detection and analysis by constructing a sensor technology based on dual-channel signal reading, which effectively reduces false-positive signals and improves the sensitivity and accuracy of detection.

Although dual-branch models have demonstrated strong performance by leveraging multimodal features, many existing approaches suffer from limitations such as inadequate interaction between branches, rigid fusion strategies (e.g., direct concatenation or addition), and insufficient adaptability to varying signal characteristics. Moreover, some methods rely heavily on manual architecture design without exploring lightweight or flexible attention mechanisms. These limitations motivate the development of a more dynamic and effective cross-modal fusion strategy. Motivated by the strengths and limitations of existing approaches, this paper proposes a novel dual-branch fault diagnosis framework,Time-frequency and time-series dual-branch fusion network(TFDFNet),which integrates both time-frequency image features and one-dimensional time-series features in a parallel structure. Unlike existing methods that focus on a single modality or use simple feature concatenation, TFDFNet adopts a lightweight cross-attention fusion mechanism and a GABlock-based signal encoder to better capture complementary and discriminative representations. The proposed model aims to improve robustness and classification accuracy in real-world, high-noise environments.

The primary contributionMotivated by the strengths and limitations of existings of this paper are as follows:

-

Proposes TFDFNet, a parallel dual-branch model for mechanical fault classification that leverages multimodal fusion of time-frequency image features and one-dimensional time-series signal features to fully exploit their complementary information and enhance fault recognition accuracy.

-

Designs a specialized signal feature extraction module, Gated attention block(GABlock), which accurately captures key information from sequential data and significantly improves the model’s representational power and classification performance.

-

Extensive experiments on multiple public datasets validate the effectiveness of the proposed method and demonstrate its strong robustness under various noise conditions.

Preliminaries

Swin Transformer

Swin Transformer33 is a hierarchical visual transformer architecture based on the sliding window mechanism, which demonstrates excellent performance in image feature extraction tasks.Swin Transformer introduces the Shifted Window Attention mechanism, which significantly reduces the computational complexity of the global self-attention by dividing the input features into fixed Swin Transformer introduces the Shifted Window Attention mechanism, by dividing the input features into fixed-size windows and locally calculating the self-attention within the windows, the computational complexity of the global self-attention is significantly reduced, which is especially suitable for the processing of high-resolution images. Meanwhile, the sliding window strategy effectively captures the contextual relationship between local and global through the information interaction across windows. In addition, Swin Transformer adopts a hierarchical feature extraction structure to extract multi-scale features while reducing the resolution of the feature map layer by layer, which makes it perform well in tasks such as image classification, target detection, and instance segmentation.

In terms of time-frequency map feature extraction, Swin Transformer’s local-awareness and multi-scale modeling capabilities have significant advantages. As a two-dimensional image representation, the time-frequency diagram can intuitively reflect the time-frequency distribution characteristics of the signal. By utilizing the layered architecture of Swin Transformer, key local and global features in the time-frequency diagram can be fully captured, while retaining the rich information of the signal in the time and frequency dimensions. Compared with traditional convolutional neural networks, Swin Transformer not only has stronger modeling capabilities, but also captures the long-distance dependencies between features in the time-frequency diagram through the self-attention mechanism, which improves the comprehensiveness and robustness of feature representation and provides a more efficient solution for signal processing and analysis tasks.

Gated Recurrent Unit

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is a simplified version of the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). The GRU combines the input and forget gates in the LSTM by integrating them into a single update gate and contains two key gate structures: the reset gate and the update gate. The update gate is responsible for controlling the relationship between the current hidden layer and the hidden layer at the previous moment. The larger the value of the update gate, the more influence the previous moment hidden layer has on the current hidden layer. On the contrary, the reset gate determines the extent to which the previous moment’s hidden layer information is ignored. The smaller the value of the reset gate, the more information from the previous moment is ignored. Specifically, the reset gate mainly controls how the previous hidden state and the current input information are combined, while the update gate determines how much a priori information should be retained at the current moment34. The gating structure of the GRU is shown in Fig. 1.

In Fig. 1, \(x_t\) denotes the input data at time t, \(h_t\) denotes the output of the GRU unit, and \(r_t\) and \(z_t\) are the reset gate and update gate, respectively. With \(r_t\) and \(z_t\), the GRU computes a new hidden state \(h_t\) based on the previous hidden state \(h_{t-1}\). The calculation process can be expressed as follows:

Here, \(\sigma (\cdot )\) denotes the sigmoid activation function, \(\tanh (\cdot )\) denotes the hyperbolic tangent activation, \(W_z, W_r, W_h\) are the input weight matrices, \(U_z, U_r, U_h\) are the recurrent weight matrices, and \(b_z, b_r, b_h\) are the bias terms. The update gate \(z_t\) controls the degree to which the previous hidden state contributes to the current hidden state, while the reset gate \(r_t\) decides how much past information should be ignored when computing the candidate hidden state \(\tilde{h}_t\). Finally, the hidden state \(h_t\) is obtained by interpolating between the previous hidden state \(h_{t-1}\) and the candidate state \(\tilde{h}_t\) according to the update gate.

Proposed methods

Overall framework

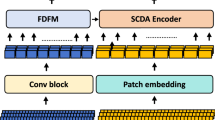

This study proposes a novel two-branch fault diagnosis model that incorporates time-frequency features and time-sequence features to achieve accurate fault classification. As shown in Fig. 2, the model mainly consists of a time-frequency feature extraction branch and a time-sequence feature extraction branch. These two branches respectively extract complementary information from the original signal and subsequently perform feature fusion to enhance the model’s characterization capability. In the time-frequency feature extraction branch, the original signal is first subjected to continuous wavelet transform to convert it into time-frequency images. These time-frequency images are then fed into Swin Transformer for feature extraction, which serves as an efficient image encoder capable of capturing multi-scale spatial dependencies while reducing computational complexity. Finally, the time-frequency features extracted in this branch are denoted as \(F_1\). In the time-series feature extraction branch, the original signal is first segmented using sliding window sampling to preserve its time-series information. The segmented signal is then fed into the feature extraction module (GABlock), which is used to capture the local and global information of the signal, and the extracted time-series features are noted as \(F_2\). Before feature fusion, a feature alignment strategy is applied to unify the feature dimensions of \(F_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{M \times d_1}\) and \(F_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times d_2}\). Specifically, we apply a linear transformation:

where \(W_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{d_1 \times d}\) and \(W_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{d_2 \times d}\) are learnable projection matrices, projecting both modalities into the same feature space \(\mathbb {R}^d\).

In order to effectively integrate the features extracted from the two branches, we introduce a feature fusion mechanism that enhances the cross-modal feature interaction. Through this mechanism, \(F_1\) and\(F_2\) are fused, so that the time-frequency features and the time-sequence features can complement each other, and the completeness and discriminative power of the feature representation are enhanced. Compared with simple fusion methods, cross-attention adaptively focuses on salient features from the other modality, defined as:

In this equation, Q, K, and V represent the query, key, and value matrices derived from the input features, and d is the feature dimension used for scaling the dot product.This operation allows the model to dynamically emphasize key parts of the counterpart signal, enabling finer discrimination of similar fault types. Finally, the fused feature representation F passes through the full connectivity layer (FC) and is classified by the Softmax classifier to obtain the final fault diagnosis results. The framework makes full use of the complementary nature of different types of features, improves the classification accuracy, and demonstrates good robustness under multiple operating conditions.To provide a clearer understanding of the processing steps in TFDFNet, Algorithm 1 summarizes the overall workflow of the proposed model from data preprocessing to fault diagnosis.

Multimodal feature extraction module

Time-frequency feature extraction branch

In order to fully utilize the time-frequency information of the signal, this study adopts the continuous wavelet transform to transform the one-dimensional signal into a time-frequency map, and extracts the time-frequency features using a deep network. Although CNNs have commonly been used in prior work for feature extraction on such maps, the Swin Transformer provides significant advantages. It utilizes window-based local self-attention to reduce computational complexity, while its shifted window mechanism enables effective cross-region modeling and enhances global context awareness.In addition, the hierarchical structure and patch merging strategy of the Swin Transformer allow for multi-scale feature modeling, which is particularly beneficial in capturing fault patterns at different temporal and frequency resolutions.

Let the input time-frequency map be denoted as \(S \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\), where \(H\) and \(W\) denote the frequency and time dimensions, respectively, and \(C\) is the number of channels. First, a linear projection layer is used to divide the input into a series of non-overlapping patches as the input feature representation of the Transformer:

where \(W_{emb}\) and \(b_{emb}\) are learnable parameters for feature mapping. The projected features are then passed through multiple Swin Transformer layers for feature extraction. Each Swin Transformer layer consists of Window Self-Attention (W-MSA) and Shift Window Self-Attention (SW-MSA), where the attention is computed as follows:

where \(Q, K, V\) is the query, key, and value matrix, and \(d\) is the scaling factor. W-MSA computes attention within local windows, while SW-MSA shifts the window positions to facilitate cross-region feature interactions, thereby enabling the network to model both local and global dependencies efficiently. This enables the model to maintain a balance between representation richness and computational efficiency, which is particularly important for large-scale industrial fault data.

Finally, after processing in multiple Transformer layers,the extracted time-frequency features are represented as:

where \(M\) is the feature sequence length and \(d_1\) is the feature dimension. The feature will be fused with the timing features in the subsequent branch fusion module to improve the fault diagnosis performance.

Time-series feature extraction branch

The temporal signal feature extraction method is in extracting deep temporal patterns from one-dimensional sensing signals to enhance the representation of technical fault characteristics. Given the original sensing signal \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \dots , x_R\}\), the signal is first reconstructed by applying the sliding window technique to obtain successive localized timing segments:

where \(N\) denotes the number of sequences after window division, \(w\) is the length of the window, and each \(X_i\) is passed as an independent input to the temporal feature extraction module.

To efficiently extract temporal patterns, we construct a feature extraction module named GABlock, which integrates the strengths of recurrent neural networks and attention mechanisms.Specifically, GABlock combines GRU-based modeling of sequential dependencies with a gated attention mechanism to adaptively emphasize critical time steps. Let \(H_0 \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times d}\) be the initialized representation of the input signals, where \(d\) denotes the feature dimensions of each window segment, and GABlock generates deep time-series features through a series of mapping functions \(f(\cdot )\):

in this process, the implicit representation \(h_t\) of each time step \(t\) is calculated from the dynamics of the signals before and after the correlation:

where \(W_h\) and \(b_h\) are trainable parameters and \(\varphi (\cdot )\) denotes the nonlinear activation function. Subsequently, the importance coefficient \(\alpha _t\) is computed for each time step using the feature weighting mechanism:

the global temporal feature representation is obtained after weighting:

In implementation, GABlock consists of two 1D convolution layers (kernel size = 5, stride = 1) with GELU activations and BatchNorm for robust feature learning. A global average pooling layer aggregates contextual cues, and the attention mechanism dynamically adjusts feature importance across time.This allows the model to capture both transient and long-term dependencies in the input signal.We also provide a comparative analysis in Sect. "Comparison of temporal feature extractors" to validate the effectiveness of GABlock against classical temporal models such as GRU and LSTM.

Finally, the timing features \(H_{TS}\) generated by GABlock serve as the time-series representation of the input signal and are passed to the subsequent fusion module.

Branch fusion

After completing the time-frequency feature extraction and the time-sequence feature extraction, the features from the two branches need to be fused to fully leverage their complementary information and improve fault classification performance. Let the output features of the time-frequency feature extraction branch be denoted as \(H_{TF} \in \mathbb {R}^{M \times d_1}\), and the output features of the time-sequence feature extraction branch as \(H_{TS} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times d_2}\), where \(M\) and \(N\) represent the feature lengths of the two branches, \(d_1\) and \(d_2\) represent their feature dimensions, respectively. To effectively utilize the complementary information from both branches, we introduce the Cross-Attention mechanism, which enhances the interaction between the time-frequency and time-sequence features, allowing them to focus on each other’s important information.

First, the time-frequency features \(H_{TF}\) and time-sequence features \(H_{TS}\) are mapped to Query, Key, and Value representations via learnable linear transformation matrices:

where \(W_Q, W_K, W_V, W'_Q, W'_K, W'_V\) are trainable parameter matrices used to project the features into the same attention space. Then, the attention scores between the two branches are computed to quantify the similarity between the feature sets:

where \(d\) is the scaling factor to prevent excessively large attention scores. The computed attention scores are used to weight the corresponding values to generate the enhanced feature representations:

which capture the important information from the complementary modality.

Finally, the final fused feature representation is obtained by concatenating the enhanced features and applying a nonlinear transformation:

where \(W_f\) and \(b_f\) are learnable parameters, and \(\sigma (\cdot )\) represents a nonlinear activation function, such as Rectified linear unit(ReLU) or Gaussian error linear unit(GELU). The resulting \(H_{fusion}\) is then passed to the final classification layer for fault classification. After the final fully connected layer and softmax classifier, the probability distribution over \(C\) fault classes is obtained:

where \(W_c\) and \(b_c\) are trainable parameters, and \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb {R}^{C}\) represents the predicted probability distribution. This cross-attention fusion mechanism enables the model to adaptively focus on the most salient and informative regions of the complementary modality, significantly enhancing the robustness and discriminability of the learned feature representations. The overall process of cross-attention feature interaction and fusion is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Experiments

In order to assess the validity, progress and robustness of the proposed model, experimental analyses are carried out in this paper using CWRU and Ottawa bearing failure datasets.

Dataset description

The Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center provides the CWRU dataset35, which serves as a widely recognized benchmark for bearing fault diagnosis research. As depicted in Fig. 4, the experimental setup includes a drive motor, torque sensor, dynamometer, and associated control electronics. The test bearings are mounted on the motor shaft. Single-point defects of varying severities were introduced into the bearings using electro-discharge machining (EDM), with fault diameters of 0.007 inches, 0.014 inches, 0.021 inches, and 0.028 inches. Owing to incomplete measurements for the 0.028-inch faults, only data corresponding to the other three fault sizes are utilized in this study.The complete dataset comprises 161 samples, categorized into four groups: 48k normal baseline, 48k drive-end fault samples, 12k drive-end fault samples, and 12k fan-end fault samples. Each category includes faults of different types, namely ball defects, inner race defects, and outer race defects. Furthermore, the outer race faults are classified according to their angular positions relative to the load zone: ‘centre’ (6 o’clock position), ‘orthogonal’ (3 o’clock), and ‘reverse’ (12 o’clock).The experiments were conducted under four distinct load conditions: 0 hp, 1 hp, 2 hp, and 3 hp. The rotational speed of the motor varied between 1797 rpm and 1730 rpm. Vibration signals were collected from three accelerometers mounted on the drive end, fan end, and motor base. Each sample was recorded over a duration of 10 seconds, with a consistent sampling frequency.

In this study, the experimental dataset is derived from the vibration signals collected at the drive end bearing. The data acquisition was performed using an accelerometer operating at a sampling frequency of 12kHz, under a load torque of 0hp and a rotational speed of 1797rpm. The fault location corresponds to the outer race at the 6 o’clock position. Detailed parameter settings of the dataset are summarized in Table 1, and the corresponding time-domain waveform is illustrated in Fig. 5.

The Ottawa dataset is generated through experimental studies using the SpectraQuest machinery fault simulator (MFS-PK5M)36. As illustrated in Fig. 6, vibration signals were acquired by accelerometers installed on the bearing housing, with a maximum sampling rate of 200 kHz. This dataset includes two core experimental factors: bearing health conditions and rotational speed variations. The health conditions encompass five types: healthy bearings, inner race (IR) faults, outer race (OR) faults, ball faults, and compound faults involving simultaneous defects in the IR, OR, and ball. For the speed variations, four scenarios are considered: monotonically increasing speed, monotonically decreasing speed, increasing then decreasing speed, and decreasing then increasing speed. By combining these two experimental factors, the dataset covers a total of 20 distinct operating conditions. In this study, we select the ramp-up speed condition as the experimental dataset. Detailed configuration parameters are listed in Table 2, and the time-domain waveform of the vibration signals is presented in Fig. 7.

Data preprocessing

Slide window resampling

The sliding window resampling technique is commonly employed in time-series analysis and signal processing to extract local features and capture temporal dependencies. It involves sliding a fixed-size window over the input data, where each window represents a subset of the sequence used for further analysis or model training. The primary advantage of this method lies in its ability to maintain the sequential structure of the data while reducing the impact of noise by focusing on localized segments. Mathematically, the sliding window approach can be described as follows: Given a time-series data\(\{x_1, x_2, \dots , x_T\}\),where \(T\) represents the total number of time steps,a sliding window of size \(W\) is defined.The window slides across the data with a step size \(S\),which determines the overlap between consecutive windows. The i-th window \(W_i\) can be expressed as:

Gaussian noise

In real industrial environments, noise usually originates from the superposition of a number of factors, including insufficient lubrication due to improper installation and external objects, friction due to indentation or rust, and irregular noise caused by cracks. Each of these noise sources has different probability distribution characteristics. Based on the central limit theorem, the sum of several independent random variables tends to follow a Gaussian distribution, regardless of the individual distributions of these variables. As such, by superimposing multiple random variables with different statistical characteristics, the resulting noise closely approximates the complex noise encountered in real industrial environments. In this study, Gaussian noise is introduced into the original vibration signals to emulate such real-world disturbances, enabling the evaluation of the diagnostic model’s robustness under noisy conditions. The noise intensity relative to the signal is quantified using the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is mathematically defined as:

where \(P_s\) and \(P_n\) represent the power of the signal and the noise, respectively. As the level of noise interference increases, the signal-to-noise ratio decreases accordingly. In the special case where the SNR equals zero, the noise power and the signal power are identical.

The quantities \(P_s\) and \(P_n\) denote the power of the signal and noise, respectively. As the degree of noise interference increases, the corresponding signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) decreases. Notably, when the SNR value reaches zero, the noise power equals the signal power. Let \(x_i\) denote the signal sequence, where \(i = 1, 2, \dots , T\). The signal power \(P_s\) can be computed using the following formula:

based on different SNR levels, the noise power \(P_n\) can be determined using:

Continuous wavelet transform

In fault diagnosis, sensor signals containing temporal information are usually recorded as time series of data points37. Due to the time-varying and non-stationary nature of the sensor signals, their global characteristics in the time or frequency domains are not sufficient for effective analysis and usually fail to reveal the intrinsic laws of the fault states. Therefore, Joint Time-Frequency Analysis (JTFA) is needed to reveal the evolution of the signal spectrum over time. The time-frequency diagrams obtained by JTFA calculation can provide comprehensive information about the signal. The continuous wavelet transform is one of the most commonly applied techniques within the framework of joint time-frequency analysis (JTFA). It possesses several important properties, including superposition, invariance under time shifts, and scale covariance. By adjusting the scale and translation parameters of the mother wavelet, CWT enables multi-resolution analysis, allowing the extraction of features from signals across a range of time and frequency domains. Specifically, larger scales correspond to broader time windows for analyzing low-frequency components, while smaller scales provide narrower time windows for capturing high-frequency details. This facilitates a comprehensive decomposition of the signal into its time-frequency representations.

Set \(\psi (t) \in L^2(\mathbb {R})\), \(\psi (t)\) is a basic wavelet or mother wavelet,then

where \(a \in \mathbb {R}\), \(a> 0\), is the scale parameter controlling dilation, and \(\tau \in \mathbb {R}\) is the translation parameter controlling time shift. For a square-integrable signal \(f(t) \in L^2(\mathbb {R})\), the CWT is mathematically expressed as:

When the scale parameter \(a\) increases, the transform captures low-frequency components; conversely, smaller \(a\) values emphasize high-frequency components in the signal.

A critical aspect of CWT is the selection of an appropriate wavelet basis function, as this choice directly impacts both the accuracy and efficiency of the transform. Common wavelet bases include the Haar wavelet, Coiflet wavelet, Morlet wavelet, and the complex Morlet (cmor) wavelet. Among these, the cmor wavelet, a complex extension of the Morlet wavelet, is frequently preferred due to its superior adaptability. By applying CWT to time-series signals, a two-dimensional time-frequency representation can be obtained, effectively revealing fault-related features within the signal.

Data preprocessing

In the original dataset, the raw vibration signals are represented as long discrete time series, characterized by a limited number of samples and a high temporal resolution within each sample. Such characteristics pose challenges for deep learning models: the small sample size may compromise training accuracy and increase the risk of overfitting, while the excessive time dimension in individual samples can negatively impact training efficiency. To address these issues, we first apply the sliding window sampling method described in Sect. “Gaussian noise”, selecting a window length of 1024. This window size is determined by balancing the sampling rates of the respective datasets with the need to effectively capture fault features. For instance, in the CWRU dataset, the drive-end sampling rate is 12 kHz and the motor rotates at 1797 rpm, producing approximately 403 data points per revolution. A window of 1024 thus spans roughly 2.54 rotations, sufficiently covering the complete vibration signature of the bearing. In contrast, the Ottawa dataset operates at a sampling rate of 200 kHz and a maximum rotational speed of 28.5 Hz under ramp-up conditions, yielding about 7018 points per rotation. Under these conditions, a 1024-point window corresponds to roughly 0.15 rotations, reducing computational complexity while still preserving key feature information. The use of sliding windows not only increases the total number of samples but also reduces the time dimension of each sample, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization performance. An overlap rate of 50% is applied during windowing to mitigate the loss of edge features in the original vibration signals. Following window segmentation, the data is divided into training, validation, and testing subsets in a ratio of 7:2:1. Finally, the continuous wavelet transform method introduced in Sect. “Gaussian noise” is employed to convert the segmented signals into two-dimensional time-frequency representations. Example time-frequency maps for four distinct locations are shown in Fig. 8.

To evaluate the bearing fault diagnosis performance under noise interference, we created datasets under three different operating conditions:

Condition 1: The training and validation sets are corrupted with Gaussian noise at SNRs of –4 dB and 4 dB, respectively. The model is then tested on signals with SNR of –8 dB, –6 dB, 0 dB, 6 dB, and 8 dB. This setting evaluates the model’s generalization ability under varying noise levels.

Condition 2: The original dataset is divided into three equal parts. Gaussian noise with an SNR of −8 dB is added to the first third, 0 dB to the middle third, and 8 dB to the final third. After noise injection, sliding window sampling is applied to construct the training, validation, and test sets.

Condition 3: The training and validation sets are segmented into three equal portions. The first third is corrupted with 4 dB noise, the middle third with 0 dB, and the final third with 8 dB. The model is then tested on a test set with an SNR of −4 dB to evaluate its generalization capability in unseen noisy environments.

Figure 9 shows the original vibration signal, Gaussian noise signals with SNRs of 8 dB, 0 dB, and −8 dB, and the mixed signal of the original signal and Gaussian noise. The original vibration signal corresponds to the ball defect fault bearing condition from the Ottawa dataset. It is evident that after adding Gaussian noise, the original vibration signal becomes significantly distorted, with the distortion becoming more severe as the SNR decreases. Therefore, accurately identifying bearing fault patterns in a noisy environment is challenging.

Experimental setup

Baseline systems

We have selected three high-level models as the baseline for our comparison experiments based on their excellent performance in fault diagnosis.These models will help us evaluate the effectiveness, progress and robustness of the proposed TFDFNet.In the following, we briefly describe the baseline models.For comprehensive details on their structure and implementation, please refer to the cited sources.

-

(1)

Efficient channel attention network (ECANet)38 is a neural network architecture designed for image processing tasks. It improves feature representation by efficiently capturing inter-channel relationships in images while maintaining high efficiency.ECANet achieves superior performance by introducing a channel attention mechanism to capture relationships between different channels. The weights of the channel features are adaptively adjusted to enhance the representation of the network without adding excessive parameters and computational cost.

-

(2)

The dense connection resNet (DResnet)39 utilizes ResNet18 as the backbone network and introduces dense connections between the residual blocks. In addition, a transition layer is used to adjust the feature channel dimensions, and a pre-activation layer is used to interact with the combined features across the channel information. Dense connections are introduced between the residual blocks to transfer the shallow feature information into the deeper feature information. The final classifier fuses the shallow features to enhance the utilization of the extracted features.

-

(3)

The Multi-sensor Residual Convolutional Fusion Network (MRCFN)28 is a deep learning model designed for robust fault diagnosis under noisy and small-sample conditions. By integrating vibration and acoustic signals, MRCFN enhances feature representation through a double ring residual structure, which captures local discriminative features efficiently. A spatial channel reconstruction module is introduced to suppress redundant information and highlight salient features, while a global interactive fusion mechanism enables effective cross-modal feature integration. This architecture achieves high diagnostic accuracy and strong robustness, outperforming existing multi-sensor fusion methods with relatively low computational overhead.

Implementation details

In our image branch, we use \(swin\_base\_patch4\_window7\_224\) as the image encoder. All input images are resized to \(224 \times 224\) and normalized with mean (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and standard deviation (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) before being fed into the network. In the signal branch, each signal is reconstructed into a sequence of 32 time steps with 32 features, which are then processed by a two-layer bidirectional GRU. The hidden sizes of the BiGRU layers are 32 and 64, respectively, resulting in a final output dimension of 128 due to bidirectionality. To further emphasize informative temporal patterns, a global attention module with a hidden size of 64 is applied on top of the BiGRU outputs.

The operating system of the running environment is Ubuntu 20.04, equipped with an RTX 4060Ti GPU with 24GB memory, Python 3.10, and PyTorch 2.0.1. To ensure fairness, all comparative experiments are conducted on the same hardware platform. The model is trained with the Adam optimizer, an initial learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-3}\) (reduced by a factor of 0.1 if the validation performance does not improve for 10 consecutive epochs), and the cross-entropy loss function. The batch size is set to 32, and training runs for 50 epochs with early stopping applied using a patience of 15 epochs. To ensure compatibility between the two feature branches during fusion, all features are projected into a unified dimension of 128 through learnable linear transformations before entering the attention module.

Result and analysis

Experimental results on the CWRU dataset

First we validate the diagnostic model for the bearing problem using the dataset without added noise and the results are shown in Table 3. The proposed model and the baseline model perform very well in the task of fault diagnosis on the test data without noise, with fault diagnosis accuracies exceeding 85% in all cases. ours exhibits excellent performance, achieving state-of-the-art results, and its fault diagnosis accuracy remains stable at 100% over multiple validations, which is significantly higher than that of the other baseline models. Compared with MRCFN (97.68%) and ECANet (95.74%), TFDFNet has a higher classification accuracy, which indicates that TFDFNet is able to learn the feature information in the bearing signals more fully through the dual-channel architecture in combination with the GABlock module, which effectively reduces the loss of information and achieves higher classification accuracy.

Subsequently, in order to evaluate the noise resistance of the models, experiments were conducted under three working conditions, and as can be seen from Table 4, under the first working condition, there is a significant difference in the fault diagnosis accuracy of the different models under different signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. Overall, the diagnostic accuracy of the models generally improves as the SNR increases. When \(SNR> 6\) dB, the accuracy of all models is above 85%, indicating that they are robust in weak noise environments. However, at SNR = −8 dB and −6 dB, the performance of DResNet and ECANet is lower, with accuracies of only 51.69% and 53.85% (DResNet) and 53.38% and 59.69% (ECANet), respectively, indicating that these two models are less adaptable to strong noise environments. MRCFN, on the other hand, still performs well under lower SNR conditions, achieving an accuracy of 81.99% at SNR = −8 dB, demonstrating some noise resistance. The proposed method (OURS) exhibits excellent fault diagnosis capability at all noise levels, especially at SNR = 0 dB, 6 dB, and 8 dB, where its accuracy is consistently 100%, far exceeding other baseline models.

From the results in Table 5, in Condition 2, the fault diagnosis accuracy of each model is improved compared to that of Condition 1, but there are still some differences.The accuracy of DResNet in this condition is 77.52%, and that of ECANet is 86.06%, which is improved compared to that of the low SNR test in Condition 1 improved.The performance of MRCFN is more stable at 95.87%, indicating that it still has strong feature extraction capability under different noise distributions. However, our accuracy is as high as 99.48%, which is again better than the other methods, indicating its high robustness in dealing with complex noise environments.

In the experiments of condition 3, we further evaluated the performance of each model under more complex noise conditions. As shown in Table 6, the fault diagnosis accuracy drops to 69.12% for DResNet and 80.01% for ECANet, indicating that these two methods are less adaptable to non-uniform noise. MRCFN, on the other hand, although still maintains a high accuracy rate (93.58%), it decreases compared to Case II. In this case, our model still maintained a high accuracy of 98.66%, which is much better than the other methods. This shows that the proposed method can still effectively capture the fault characteristics when facing the non-uniform noise with different signal-to-noise ratios, which demonstrates a strong noise-resistant capability.

Figure 10 shows the confusion matrix for the four models predicting the ten fault types in the CWRU test dataset at SNR = −8 dB. From the confusion matrix, it can be observed that DResNet has a poor ability to discriminate between fault categories, especially between faults C2(inner race fault 0.007), C3(ball fault 0.007), C8(inner race fault 0.021), and C9(ball fault 0.021), where the models show a high confusion rate. Particularly, the confusion between the fault categories C2 and C9 is such that DResNet can hardly distinguish them accurately, leading to more misclassifications. In addition, the C1 (normal) state is also misclassified into multiple fault types, which further shows the weak robustness of the model at low signal-to-noise ratios. The classification performance of ECANet is slightly better than that of DResNet, and from the confusion matrix, ECANet still has more obvious confusions although it is improved than DResNet. For example, the confusion between faults C2 and C9 is more serious, indicating that the model’s feature extraction capability needs to be further enhanced when dealing with these fault types. In addition, the C1 state is also misclassified as C3 and C9, which further proves that ECANet has some classification instability under noise interference. In contrast,MRCFN achieves more satisfactory classification results on most of the categories, especially the C1, C6 (ball fault 0.014), and C5 (inner race fault 0.014) categories with very high accurate classification rates. However, it can still be seen that there is some confusion between C2 and C9, which shows that the MRCFN has some errors in dealing with some similar types of faults. From the analysis of the confusion matrix, it can be seen that there is almost no misclassification in our model, and almost all fault categories can be classified accurately. Especially on the categories C1 and C10 (outer race fault 0.021), the correct classification rate is 100%.

To further investigate the feature extraction capability of the four comparative models in noisy environments, we performed a graphical demonstration of representative features for fault classification at SNR = −8 dB as shown in Fig. 11. We used a T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction method40 to map the feature vectors into a two-dimensional space. According to the t-SNE visualization graph, the performance of the four models in handling the test dataset varies significantly.DResNet (Fig. 11a) shows strong category confounding, in particular, the distinction between normal and fault categories is not obvious, which indicates that the model is weak in feature extraction under high noise conditions.ECANet (Fig. 11b), although improved, with a reduction in overlap between categories, still has some confusion between fault types, especially between “de_7_outer” and “de_14_inner”. MRCFN (Fig.11c) demonstrates a more distinct category separation, especially between normal and fault categories, showing stronger feature extraction. distinction, showing a stronger feature learning capability.OURS (Fig.11d), on the other hand, performs the best, with almost no category overlap and a clear distribution of data points across categories, highlighting the model’s strong robustness and classification accuracy in noisy environments.

Comprehensively, TFDFNet is able to achieve 100% classification accuracy in a noiseless environment, and still maintains a clear performance advantage under high noise conditions and complex working conditions, far exceeding existing methods such as DResNet, ECANet and MRCFN. Especially, under the extreme noise environment with SNR = −8 dB, the classification accuracy of TFDFNet is still as high as 96.48%, while the accuracy of DResNet and ECANet drops to 50.32% and 58.74%, respectively. This result indicates that TFDFNet is still able to extract stable and effective fault features under high noise conditions, improving the model’s anti-interference ability. This performance improvement is attributed to the introduction of the GAblock temporal feature extraction module, which enhances the modeling capability of temporal information through the global attention mechanism, making the dependence of fault features in the time dimension clearer and maintaining high-precision classification even under complex working conditions.

Experimental results on the Ottawa dataset

As shown in Table 7, the fault diagnosis accuracies of all models on the Ottawa test set are generally high under noise-free conditions. Specifically, DResNet achieves an accuracy of 87.43%, ECANet reaches 93.24%, and MRCFN attains 96.67%. Our proposed model achieves the highest accuracy of 99.44%, indicating its strong ability to learn discriminative fault features and achieve near-perfect classification performance in ideal environments.

In Table 8, the performance of all models declines after introducing Gaussian noise with varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). DResNet and ECANet exhibit poor robustness at SNR = −8 dB, with accuracies dropping to 50.76% and 54.41%, respectively, highlighting their vulnerability to strong noise. As the SNR increases, both models show gradual performance improvement, reaching 88.31% and 95.06% at SNR = 8 dB, respectively. In contrast, MRCFN maintains relatively high accuracy even under severe noise, achieving 80.03% at SNR = −8 dB and 98.26% at SNR = 8 dB, demonstrating moderate noise resistance. Our proposed model exhibits remarkable stability across all noise levels, achieving 98.82% at SNR = −8 dB and maintaining accuracy above 98% at SNRs of 0 dB, 6 dB, and 8 dB, significantly outperforming all other methods.

Table 9 presents the results under Condition 2. In this scenario, DResNet, ECANet, and MRCFN achieve accuracies of 75.33%, 86.87%, and 94.68%, respectively. Although MRCFN shows better noise robustness than DResNet and ECANet, it still fails to completely mitigate the effects of complex noise distributions. In contrast, our model maintains a high accuracy of 98.36%, further demonstrating its superior capability in handling intricate noisy environments.

Under Condition 3, which involves a more complex, non-uniform noise distribution (Table 10), the overall performance of the models deteriorates further. DResNet and ECANet experience significant accuracy drops to 67.21% and 78.17%, respectively, indicating their Limited adaptability in complex noise scenarios. MRCFN continues to exhibit a certain level of noise resilience with an accuracy of 94.25%. Notably, our proposed model still achieves a high accuracy of 98.41%, exceeding MRCFN by more than 4%, which further confirms its exceptional robustness and effectiveness in challenging noise conditions.

Figure 12 shows the confusion matrix for the four models predicting the five fault types in the ottawa test dataset at SNR = −8 dB. From the confusion matrix, it can be seen that DResNet has significant confusion between several categories, especially in the distinction between the C1 (ball fault) category and the other fault categories is more difficult. In addition, DResNet fails to show strong robustness in the identification of fault categories, resulting in a high misclassification rate, which indicates that the feature extraction capability and classification accuracy of the model have limited performance under complex noise conditions. Compared to DResNet, ECANet shows an improvement in classification over DResNet, but the confusion matrix still reveals the model’s confusion in some fault categories, especially between C2(composite fault) and C4(inner race fault). This indicates that despite ECANet’s optimization in feature learning, the model still has difficulty in distinguishing some similar faults in a low SNR environment.MRCFN significantly outperforms both DResNet and ECANet in this task, as can be seen from the confusion matrix, which shows that the MRCFN performs better on most of the categories, especially between C1 and C3(healthy) with a The classification accuracy is very high. However, despite the MRCFN’s better feature extraction ability when dealing with complex data, its confusion between categories C2 and C4 is still more significant, suggesting that the model’s robustness needs to be improved in the face of certain fault types. From the confusion matrix, ours shows almost no misclassification, and almost all categories are accurately classified, especially between categories C2 and C3, where the classification is almost error-free.From the confusion matrix, ours shows almost no misclassification, and almost all categories are accurately classified, especially between categories C2 and C3, where the classification is almost error-free. Despite the similarity between composite faults (C2) and inner race faults (C4), TFDFNet achieves nearly perfect classification, whereas other models suffer from category confusion, further demonstrating TFDFNet’s advantage in resolving closely related fault types.

According to the t-SNE visualization graph, the performance of the four models (DResNet, ECANet, MRCFN, and OURS) on the test dataset varies significantly.DResNet (Fig. 13a) shows strong category overlap, especially the distinction between fault categories and normal states is more ambiguous, which suggests that the model is weak in discriminating when dealing with complex tasks. ECANet (Fig. 13b) shows improvement compared to DResNet, but there is still some overlap between different categories, especially the distinction between C-A and H-A categories is not obvious.MRCFN (Fig. 13c) demonstrates better category separation, with less overlap between B-A and C-A categories, showing the effectiveness of the model in feature differentiation.OURS (Fig. 13d), on the other hand, shows the best performance that the distribution of all categories in 2D space is almost completely separated, showing its superior ability in feature extraction and classification accuracy.

Overall, the experimental results on the two datasets fully demonstrate the excellent performance of TFDFNet in different noise environments and complex working conditions. Its two-branch structure can effectively fuse timing and time-frequency information, and the cross-attention mechanism further optimizes the feature fusion strategy, thus improving the robustness and accuracy of fault diagnosis. TFDFNet significantly outperforms existing baseline models in terms of noise immunity in low SNR environments and stability under complex operating conditions, showing great potential for application in industrial environments.

Ablation experiments

To assess the contributions of key architectural components in TFDFNet, we conduct a series of ablation studies on the CWRU and Ottawa datasets. The analysis examines the effects of branch configurations, core modules, fusion mechanisms, temporal feature extractors, and image encoder choices on overall diagnostic performance.

Effect of dual-branch architecture

To verify the contribution of each input modality, we compare the performance of the model using only the raw time-series signal branch, only the time-frequency image branch, and the proposed dual-branch configuration. Table 11 summarizes the results.

From the experimental results, it is obvious that the model achieves a high accuracy rate (93.3%) on the CWRU dataset when only raw signal branching is used, which is significantly higher than the accuracy rate (89.73%) when only time-frequency image branching is used. This phenomenon suggests that the timing information of the original signal has a strong discriminative ability for fault diagnosis on the CWRU dataset. Furthermore, on the Ottawa dataset, the situation is different, using time-frequency image branching performs slightly better (96.57%) than the original signal branching (95.65%), which may be related to the signal characteristics of this dataset and the effectiveness of its time-frequency representation. Importantly, when we combine the image feature extraction branch and the signal feature extraction branch of the two-branch model, the performance is improved compared to any single-branch model. By fusing multimodal features, the model is able to capture key information from the signal timing and time-frequency representations more comprehensively, which improves the overall fault classification accuracy. The two-branch model on the CWRU dataset and the Ottawa dataset achieved 100% and 99.44% accuracy,(see Table 3 and Table 7 for specific results), which is a significant improvement in performance compared to the model that uses only the original signal branch and the time-frequency image branch. models, the performance is significantly improved. This demonstrates the advantage of multimodal information fusion, where the raw signal contains information about the temporal variation of the faults, while the time-frequency image reveals the frequency component of the signal, which is particularly expressive when dealing with nonlinear and complex fault modes.

Effect of key components in TFDFNet

To further investigate the contribution of each feature interaction mechanism in our model to fault diagnosis performance, we conducted ablation experiments by selectively removing specific modules from TFDFNet and evaluating the impact on classification accuracy using the CWRU and Ottawa datasets. The experimental results are summarized in Table 12.

The results demonstrate that each component contributes significantly to model performance. Removing the cross-attention fusion module–responsible for integrating time-frequency and time-series features–leads to a noticeable performance drop, confirming its effectiveness in enhancing inter-modality feature interaction. Eliminating the global attention mechanism from the temporal branch also results in decreased accuracy, highlighting the importance of dynamic temporal weighting in capturing long-term dependencies. When both components are removed, performance further degrades, though it remains better than removing either one individually. These findings underscore that the two mechanisms are complementary, and their joint use is key to achieving optimal performance in fault diagnosis.

Comparison of fusion strategies

To validate the superiority of the proposed cross-attention mechanism over simpler alternatives, we compare it with concatenation and weighted averaging fusion methods. The results are shown in Table13.

Cross-attention consistently outperforms simpler fusion strategies by a large margin, illustrating its effectiveness in selectively emphasizing relevant features across modalities.

Comparison of temporal feature extractors

We also compare GABlock with standard sequence modeling approaches such as GRU and LSTM. Each variant replaces the GABlock module in the time-series branch with a two-layer GRU or LSTM. Table14 shows the results.

GABlock outperforms both GRU and LSTM, as its hybrid structure–integrating convolutional processing, global average pooling, and attention-based weighting–provides enhanced capacity to capture both local and global temporal dependencies. This design enables more discriminative and robust representation of fault-related patterns in time-series signals.

Comparison of image encoders

To further verify the effectiveness of using Swin Transformer as the image encoder for time-frequency representations, we conducted comparative experiments against classical CNN-based backbones, including ResNet18 and a standard shallow CNN. For fair comparison, only the image branch is used, and all models share the same input resolution (224\(\times\)224) and training settings. The results are shown in Table15.

The results demonstrate that the Swin Transformer achieves the best performance among the evaluated encoders. Compared to the traditional CNN and ResNet18, Swin Transformer shows a clear advantage in modeling time-frequency images, benefiting from its ability to capture both local and global contextual information through shifted window self-attention mechanisms.

Complexity analysis

In addition to classification accuracy, it is essential to evaluate the computational complexity of different models, as complexity directly affects the feasibility of deployment in real-world industrial environments. A model with excessive parameters may achieve high accuracy but could be limited by hardware constraints in terms of memory consumption and inference efficiency. Therefore, we further compare the proposed TFDFNet with representative methods in terms of parameter size, training speed, and inference speed. The results are summarized in Table 16.

From Table 16, we observe that TFDFNet has a larger number of parameters (88.15M) compared with the other models, due to the introduction of the dual-branch architecture and attention mechanisms. As a result, both its training and inference speeds are relatively lower than those of Lightweight models such as MRCFN. Nevertheless, the inference speed of TFDFNet still reaches 166 FPS (6 ms per sample), which is sufficient for real-time fault diagnosis in most industrial scenarios. This result highlights a trade-off between model accuracy and computational complexity: TFDFNet achieves significantly higher diagnostic accuracy while maintaining acceptable efficiency, making it a practical solution for engineering applications where robustness and reliability are of paramount importance.

Conclusions and future work

In this paper, we propose a novel fault diagnosis model that integrates raw signal features with time-frequency image features to achieve more accurate fault classification. The model adopts a parallel two-branch architecture: one branch extracts features from time-frequency representations, while the other learns temporal features directly from the raw signals. To effectively fuse these heterogeneous modalities, we introduce a feature interaction mechanism that enhances information exchange between the two branches, thereby fully exploiting the complementarity of different feature types.Extensive experiments conducted on publicly available datasets demonstrate that the proposed dual-branch model outperforms traditional single-branch architectures, confirming the effectiveness of multimodal feature fusion. Furthermore, ablation studies verify the individual contributions of each model component, highlighting the significant role of combining diverse feature representations in boosting diagnostic performance. Notably, our model maintains high classification accuracy even under various noise conditions, indicating its strong robustness and practical potential for real-world fault diagnosis applications.

Despite these promising results, several limitations still exist when applying the proposed method in real-world industrial environments. The dual-branch architecture increases computational complexity, which may hinder real-time performance and deployment on resource-constrained devices. In addition, the model assumes consistent distributions between training and testing data, which is often not the case due to domain shifts caused by different machines, sensors, or operating conditions. The method also heavily relies on labeled training data, which are often limited or costly to obtain in practical scenarios.To address these limitations, we aim to enhance the practicality and adaptability of TFDFNet in future work. We will explore lightweight model designs to reduce computational cost and enable deployment on edge devices. Online learning mechanisms will be considered to allow the model to adapt dynamically to new data during operation. We also plan to investigate transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques to improve robustness across varying machines and conditions. Moreover, to alleviate reliance on large-scale annotated data, we will study few-shot learning and self-supervised learning strategies. These efforts will collectively improve the generalization ability, efficiency, and real-time applicability of the proposed framework.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study were derived from the following public domain resources: https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter/download-data-file; https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/v43hmbwxpm/1.

References

Sun, Y. & Li, S. Bearing fault diagnosis based on optimal convolution neural network. Measurement 190, 110702 (2022).

Song, B. et al. An optimized cnn-bilstm network for bearing fault diagnosis under multiple working conditions with limited training samples. Neurocomputing 574, 127284 (2024).

Zhang, W., Li, C., Peng, G., Chen, Y. & Zhang, Z. A deep convolutional neural network with new training methods for bearing fault diagnosis under noisy environment and different working load. Mech. systems signal processing 100, 439–453 (2018).

Gu, J., Peng, Y., Lu, H., Chang, X. & Chen, G. A novel fault diagnosis method of rotating machinery via vmd, cwt and improved cnn. Measurement 200, 111635 (2022).

Rai, V. & Mohanty, A. Bearing fault diagnosis using fft of intrinsic mode functions in hilbert-huang transform. Mech. systems and signal processing 21, 2607–2615 (2007).

Peng, Z., Chu, F. & He, Y. Vibration signal analysis and feature extraction based on reassigned wavelet scalogram. Journal of Sound and Vibration 253, 1087–1100 (2002).

Cheng, C., Zhou, B., Ma, G., Wu, D. & Yuan, Y. Wasserstein distance based deep adversarial transfer learning for intelligent fault diagnosis with unlabeled or insufficient labeled data. Neurocomputing 409, 35–45 (2020).

Wang, X., Liu, C., Bi, F., Bi, X. & Shao, K. Fault diagnosis of diesel engine based on adaptive wavelet packets and eemd-fractal dimension. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 41, 581–597 (2013).

Castejón, C., Gómez, M. J., Garcia-Prada, J. C., Ordonez, A. & Rubio, H. Automatic selection of the wpt decomposition level for condition monitoring of rotor elements based on the sensitivity analysis of the wavelet energy. Int. J. Acoust. Vib 20, 95–100 (2015).

Cocconcelli, M., Zimroz, R., Rubini, R. & Bartelmus, W. Stft based approach for ball bearing fault detection in a varying speed motor. In Condition Monitoring of Machinery in Non-Stationary Operations: Proceedings of the Second International Conference” Condition Monitoring of Machinery in Non-Stationnary Operations” CMMNO’2012, 41–50 (Springer, 2012).

Chen, H. et al. Wind turbine gearbox fault diagnosis based on improved eemd and hilbert square demodulation. Appl. Sci. 7, 128 (2017).

Bin, G. F., Gao, J. J., Li, X. J. & Dhillon, B. Early fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on wavelet packets-empirical mode decomposition feature extraction and neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 27, 696–711 (2012).

Jiang, H., Chen, J., Dong, G., Liu, T. & Chen, G. Study on hankel matrix-based svd and its application in rolling element bearing fault diagnosis. Mech. systems signal processing 52, 338–359 (2015).

Wang, J., Mo, Z., Zhang, H. & Miao, Q. A deep learning method for bearing fault diagnosis based on time-frequency image. IEEE Access 7, 42373–42383 (2019).

Zhu, Z., Peng, G., Chen, Y. & Gao, H. A convolutional neural network based on a capsule network with strong generalization for bearing fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 323, 62–75 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Li, X., Gao, L. & Li, P. A new subset based deep feature learning method for intelligent fault diagnosis of bearing. Expert. Syst. with Appl. 110, 125–142 (2018).

Wang, X., Li, A. & Han, G. A deep-learning-based fault diagnosis method of industrial bearings using multi-source information. Appl. Sci. 13, 933 (2023).

Ma, M. & Mao, Z. Deep-convolution-based lstm network for remaining useful life prediction. IEEE Transactions on Ind. Informatics 17, 1658–1667 (2020).

Dibaj, A., Ettefagh, M. M., Hassannejad, R. & Ehghaghi, M. B. A hybrid fine-tuned vmd and cnn scheme for untrained compound fault diagnosis of rotating machinery with unequal-severity faults. Expert. Syst. with Appl. 167, (2021).

Lu, C., Wang, Z. & Zhou, B. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearing using hierarchical convolutional network based health state classification. Adv. Eng. Informatics 32, 139–151 (2017).

Zhang, W., Li, X. & Ding, Q. Deep residual learning-based fault diagnosis method for rotating machinery. ISA transactions 95, 295–305 (2019).

Li, X., Zhang, W. & Ding, Q. A robust intelligent fault diagnosis method for rolling element bearings based on deep distance metric learning. Neurocomputing 310, 77–95 (2018).

Huang, W., Cheng, J., Yang, Y. & Guo, G. An improved deep convolutional neural network with multi-scale information for bearing fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 359, 77–92 (2019).

Li, F., Wang, L., Wang, D., Wu, J. & Zhao, H. An adaptive multiscale fully convolutional network for bearing fault diagnosis under noisy environments. Measurement 216, 112993 (2023).

Yan, X., Jiang, D., Xiang, L., Xu, Y. & Wang, Y. Cdtfafn: A novel coarse-to-fine dual-scale time-frequency attention fusion network for machinery vibro-acoustic fault diagnosis. Inf. Fusion 112, (2024).

Chen, X., Yang, R., Xue, Y., Song, B. & Wang, Z. Tfpred: Learning discriminative representations from unlabeled data for few-label rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Control. Eng. Pract. 146, (2024).

Ye, M., Yan, X., Jiang, D., Xiang, L. & Chen, N. Mifdeln: A multi-sensor information fusion deep ensemble learning network for diagnosing bearing faults in noisy scenarios. Knowledge-Based Syst. 284, (2024).

Ye, M. et al. Mrcfn: A multi-sensor residual convolutional fusion network for intelligent fault diagnosis of bearings in noisy and small sample scenarios. Expert. Syst. with Appl. 259, (2025).

Jiang, L., Lei, W., Wang, S., Guo, S. & Li, Y. A deep convolution multi-adversarial adaptation network with correlation alignment for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under different working conditions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. A multi-scale deep feature memory and recovery network for multi-sensor fault diagnosis in the channel missing scenario. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 145, (2025).

Chen, G. et al. Automated unruptured cerebral aneurysms detection in tof mr angiography images using dual-channel se-3d unet: a multi-center research. Eur. Radiol. 33, 3532–3543 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Xia, J., Zhang, F., Wang, Z. & Liu, Q. A dual-channel homogeneous aptasensor combining colorimetric with electrochemical strategy for thrombin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 120, 15–21 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Yuan, Y., Tian, C. & Lu, X. Auxiliary loss multimodal gru model in audio-visual speech recognition. IEEE Access 5573–5583, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2018.2796118 (2018).

University, C. W. R. Bearing data center. https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter (2025). Accessed: 2025-02-16.

Huang, H. & Baddour, N. Bearing vibration data collected under time-varying rotational speed conditions. Data in brief 21, 1745–1749 (2018).

Sun, H. et al. Multiwavelet transform and its applications in mechanical fault diagnosis – a review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2013.09.015 (2014).

Wang, Q. et al. Eca-net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 11534–11542 (2020).

Xu, X., Li, C., Zhang, X. & Zhao, Y. A dense resnet model with rgb input mapping for cross-domain mechanical fault diagnosis. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 26, 40–47 (2023).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-sne. J. machine learning research 9 (2008).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant No.2024YFB3312604.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.T. conducted the experiments, developed the methodology, and drafted the initial manuscript. M.C. contributed to the methodology and reviewed the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, W., Chen, M. TFDFNet: a dual-branch fault diagnosis model for bearings under noisy and complex industrial environments. Sci Rep 15, 35371 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19258-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19258-2