Abstract

This paper evaluates the properties of recycled polyethylene terephthalate (rPET) from bottle waste flakes for producing non-conductive injection-moulded composites for construction, specifically anchors and connectors. The work addresses the growing need for sustainable materials in civil engineering by exploring a high-value application of 100% recycled PET combined with alkaline-resistant glass fibres, suitable for use in cementitious and alkaline environments. Mechanical tests were conducted on composites reinforced with 30, 40 and 50 wt% fibres. Addition of fibres improved flow characteristics, crystallisation kinetics, and facilitated demoulding of the parts, enhancing mechanical properties (tensile modulus up to ~ 19 GPa, flexural strength up to ~ 234 MPa, and Charpy impact strength up to ~ 31 kJ/m²) and achieving properties comparable to commercial virgin PET composites. The micromechanical analysis and SEM observations confirmed the high quality and homogeneity of the composites. The favourable properties and processing characteristics pave the way for the application of these materials in injection-moulded construction components, including anchors, which are currently under further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing demand for thermoplastics, the volume of plastic waste has risen dramatically. In response, there has been a strengthening of environmental policies and the implementation of stringent legal measures aimed at effecting positive changes in waste management. One manifestation of this is Directive (EU) 2018/852 of the European Parliament, which sets minimum weight targets for the recycling of plastics from packaging waste: 50% to be achieved by 2025 and 55% by 20301. In 2022, the EU27 + 3 nations dealt with 18.5 million tons of plastic packaging, with 37.8% recycled, 44.9% used for energy recovery, and 17.3% landfilled. The recycling rate would need to increase significantly to meet the targets set by the packaging directive. Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany have already met the target, along with eliminating plastic waste landfilling. However, the plastics industry in Central Europe, including Poland, faces challenges in meeting reprocessing requirements, necessitating the import of raw materials2.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) ranks among the first in terms of the scale of global production, just behind polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC)2. Its popularity as a packaging material makes it widely represented in commingled and general waste streams. Recycling and reprocessing of PET lead to a reduction in molecular weight and melt viscosity, accompanied by the presence of impurities. These adversely affect the static and impact strength and hinder or prevent the stretch-blow moulding process of new packaging3. A potential solution to this problem is the application of post-consumer PET recyclate (rPET) as the matrix for structural composites. While an increase in melt viscosity is typically a disadvantage in filled systems, particularly for polymers filled with glass fibres (GF)4, it can be beneficial for low-viscosity rPET. As a structural material, PET possesses several important features, including a high modulus of elasticity and strength, a relatively broad operational temperature range (from − 40 to + 140 °C for semicrystalline material), fine abrasion resistance, low water absorption, favourable surface characteristics, and ease of processing5. In particular, PET composites are distinguished by their superior creep resistance and dimensional stability compared to standard PP or polyamide (PA) composites. These properties make PET composites a promising candidate for injection-moulded load-bearing products used in civil engineering.

In recent years, the possibility of using rPET as a matrix for E-GF-reinforced composites has been occasionally investigated6,7,8,9,10,11. Kráčalík et al. explored the rheological properties and structural changes in the rPET/GF (15–30 wt%) composites with talc (10 wt%). They found that a higher fibre content in the matrix resulted in an increase in melt viscosity at low shear rates and enhanced melt strength, which is considered advantageous for improving the processability of the material9. Regardless of the GF content, high fibre-matrix adhesion in the molten state was confirmed for the composites tested at a laboratory scale. Nonetheless, the researchers’ attempt to produce a PET/GF composite under production conditions failed due to the excessively high screw speed employed during extrusion. The processed composite was characterised by inhomogeneity, the presence of air bubbles, and poor adhesion of fibres to the matrix.

Mondadori et al.8 conducted research similar in scope to that presented in this paper. They focused on the influence of coupling agents used for E-type GF (20–40 wt%) on the mechanical properties of recycled PET composites. An optimal interfacial adhesion between the PET matrix and the fibres, along with good reinforcement effectiveness, were achieved for both aminosilane and epoxysilane-treated fibres. Another issue they analysed was the impact of Solid State Polymerisation (SSP) on the final properties of rPET composites. SSP is an industrial process carried out in a specialised reactor on PET regranulate or regrinds, leading to an increase in the molecular weight of rPET. In general, the authors observed a moderate improvement in tensile and impact strength for SSP-treated materials compared to the untreated ones, particularly for those containing 0–30 wt% GF. For their composites containing 30 wt% GF with SSP-treated matrix, the tensile strength of neat PET (approximately 40 MPa) increased by 200%, while the tensile modulus (initially around 3 GPa) demonstrated a 300% increase. In the present work, an SSP-treated rPET and a silane-based coupling agent were also selected for the preparation of composites with alkaline resistant (AR) GF.

Although AR-GF are typically used to reinforce construction materials, particularly concrete, they are not commonly selected for reinforcing thermoplastic matrices. Load-bearing structural composites are generally reinforced with E-glass or S-glass fibres, which are preferred for their balance of cost-effectiveness, strength, and heat resistance, as well as for the superior strength and rigidity that S-glass offers in demanding applications. Compared to E-GF, AR-GF contains a higher concentration of zirconia, which significantly enhances its alkali resistance, making it more suitable for applications in alkaline cementitious environments. As documented by Benmokrane et al.12, AR-GFused in thermoset resin rebarsdemonstrate superior durability in concrete, maintaining their mechanical properties when exposed to high pH conditions. It is also well known and documented that AR-GF exhibit significantly higher durability than E-glass fibres when directly reinforcing concrete, as in textile-reinforced concrete applications13,14. This attribute is particularly relevant for composite anchors embedded in cementitious grouts, where AR fibres are expected to provide enhanced resistance to alkali-induced degradation.

It is also interesting to consider that the resulting composite mouldings will eventually become waste and could potentially be recycled—specifically through chemical recycling, in line with current trends. Chemical recycling of PET and its composites has garnered significant research attention due to its ability to regenerate high-quality monomers, even from complex or contaminated waste. While current research primarily focuses on mechanical recycling to address immediate needs, it also acknowledges the ongoing shift in the field towards chemical recycling, particularly solvolysis methods, which include glycolysis, metanalysis, and alkaline hydrolysis. These solvolysis processes often occur in alkaline or specific chemical environments, which could affect the stability and degradation behaviour of fibre reinforcements. Future studies are planned to assess the recyclability of AR fibre composites under such solvolysis conditions, aiming to determine whether AR fibres maintain their structural integrity and performance advantages more effectively than E-GF during chemical recycling. This approach aligns with ongoing efforts towards sustainable materials management and circular economy principles for composite materials.

In this work, the aim was to improve the mechanical properties of rPET to make it a material suitable for the injection moulding of load-bearing products for construction and civil engineering, with a particular focus on adhesive anchors and connectors. As part of the TRL 4.0 project — a Polish initiative aimed at advancing technology readiness levels through research and development15,16 — such anchors were produced by our scientific team and are protected by patents: PL24371317 and PL24371418. Glass fibres were used as reinforcement due to their wide availability, consistent and reproducible properties, and well-established surface treatment methods that ensure good fibre-matrix adhesion as well as ease of handling and dosing. Alkaline-resistant GF were selected as a replacement for E-type GF due to their widespread use in construction and the potential for recycling and reuse in other building materials. To the authors’ knowledge, this was the first reported use of AR-GF in a PET matrix, and more broadly in a thermoplastic matrix, as well as the first study of rPET/GF composites evaluated as injection-moulded parts for construction applications. Test methods appropriate for construction materials were applied, including tensile, flexural, impact, and abrasive wear tests. The mechanical properties were correlated with the microstructure of the composites (DSC analysis, fibre volume fraction and fibre length distribution, SEM observations). The effectiveness of the reinforcement was evaluated against established mathematical models. Additionally, issues related to the processing of the manufactured composites were addressed.

Materials and methods

Materials

Selecting a matrix material with repeatable properties was one of the key stages in the preparation of composites based on PET recyclate. The grade chosen for this research was r + PET CL 80 M, a rPET regranulate made from PET flakes derived from a post-consumer material (ISO 14021). This rPET grade was supplied by PRT Radomsko Sp. z o. o., Poland. The rPET granulate exhibited a uniform bluish-grey colour and crystalline form, with a melting point of approximately 250 °C and intrinsic viscosity of 0.82 [dl/g] +/-0.02, according to the producer’s data. In the automatic sorting process, non-metallic materials were separated; state-of-the-art label removal was applied, followed by ballistic separation and automated colour and material sorting. After cutting, two hot washing steps and a swim-sink procedure were employed, along with further air separation, coarse grit separation, flake sorting, and homogenisation in mixing silos. The regranulate was obtained via extrusion using the SSP process, ensuring a high level of decontamination and the partial recovery of lost molecular weight.

In order to obtain material for load-bearing injection moulded parts in construction, alkaline-resistant (AR) glass fibres (GF) were added to the rPET at amounts of 30, 40, and 50 wt%. The selected fibres were ARcoteX ® 5326, manufactured using Owens Corning® Cem-FIL® AR glass chemistry. Although these fibres were initially developed for reinforcing concrete, it was considered appropriate to explore their potential as reinforcement for thermoplastic composites in construction. The nominal length of the chopped glass bundles was 3 mm, and the nominal fibre diameter was 14 μm. According to the manufacturer’s data, the fibres had a tensile modulus of 72 GPa and a density of 2.68 g/cm3. These values were then used to calculate the theoretical elastic modulus of the composites and their fibre volume fraction.

Specimen preparation

Composite granules were prepared at the Plastic Application Design and Development Centre of Grupa Azoty S.A., Tarnów, Poland, employing a compounding line with a FEDDEM FED26 MTS co-rotating twin-screw extruder (L = 91 mm, L/D = 3.5). The extrusion temperature was set at 270 °C, while the measured melt temperature was 264 °C. The fibres were introduced into the extruder using a standard side gravimetric dispenser.

Standard type ISO 527 1 A (dumb-bell shaped) and ISO 178 (80 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm) specimens were injection moulded on an Arburg 420 C 1300 150/60 2 K injection moulding machine. The temperature of the injection moulding barrel zones ranged from 270 °C to 310 °C, while the mould temperature was set to 130 °C. During injection moulding at a mould temperature of 130 °C, unfilled PET and PET containing up to 20 wt% GF (as determined in preliminary tests) exhibited low stiffness upon demoulding, making the samples prone to deformation during removal. Based on the preliminary studies, it was established that for the investigated material and the intended application, the recommended minimum fibre content should be 30 wt% rather than 20 wt%. Injection moulding of composites containing 30–50 wt% GF did not encounter any issues. Specimens with a uniform bluish-grey colour without visible injection defects were obtained.

Prior to compounding and injection moulding, rPET (filled and unfilled) was dried using dry air dryers at 120 °C for 6 h.

In the present study, the designation rPET refers to the reference material consisting of recycled PET without any filler. The designations rPET30GF, rPET40GF, and rPET50GF refer to composites containing AR-GF at 30 wt%, 40 wt%, and 50 wt% fibre content, respectively.

Methods of testing

To determine the average fibre length and actual fibre content in the tested composites, a burn-off method was applied according to ISO 3451 to extract the fibres from the matrix. The composite specimens were calcined in a muffle furnace at 600 °C until a constant mass of the residue was achieved. The fibre weight fraction was calculated and compared with the assumed filler content (30, 40, 50 wt%). Consequently, the fibre volume fraction in the composites was calculated. Based on microscopic observations, fibre length measurements were taken to estimate the fibre length distribution and to calculate the weight average fibre length for each composite. The weight average fibre length was calculated using the formula:

where \(\:{L}_{i}\) is the length of the i-th fiber in the sample and \(\:{n}_{i}\) is the sample frequency with the length increment range \(\:{L}_{i+1}-{L}_{i}\)19.

Differential scanning calorimetry was utilised to investigate the thermomechanical history of the tested materials. Samples weighing 6.2–6.9 mg were heated within the temperature range of 30–300 °C at a heating rate of 10 K/min in a helium inert atmosphere using the TA Instruments DSC Q1000 calorimeter. Phase transition temperatures were determined: glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm), along with the degree of crystallinity (χ) of the materials. The degree of crystallinity was calculated using the formula:

where: \(\:\varDelta\:{\text{H}}_{\text{m}}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\text{H}}_{\text{c}\text{c}}\) were experimental melting enthalpy and cold crystallization enthalpy, respectively, \(\:\varDelta\:{\text{H}}_{\text{m}}^{0}\)= 120 J/g was the literature data for equilibrium melting enthalpy of 100% crystalline PET8, and \(\:{W}^{f}\)was the fibre weight fraction. Cold crystallisation was not observed in the tested materials.

Static tensile tests were conducted according to ISO 527 on the universal testing machine Shimadzu AGS-X (10 kN force capacity), equipped with an axial extensometer. The modulus of elasticity, tensile strength, and strain at break were determined. Static flexural tests were performed on the MTS Criterion 45 universal testing machine (30 kN force capacity) in accordance with ISO 178 to establish flexural strength, modulus, and strain at the maximum load. The flexural strain at maximum load was found to be equal to the flexural strain at break for all of the composites. For unreinforced rPET, the flexural test was halted prior to failure due to significant deformation after exceeding the maximum force. Charpy impact strength without notch was measured using the Zwick/Roell HIT5.5P device under the ISO 179 1eU method. Abrasion tests were carried out in accordance with ISO 4649 using the Schopper-Schlobach apparatus. The volume loss was determined, and consequently, the abrasion resistance was assessed.

Microscopic observations were conducted on the gold-sputtered tensile fracture surfaces using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) Jeol JSM-IT200. SEM images were obtained to qualitatively evaluate fibre distribution, fibre/matrix adhesion, and failure modes and mechanisms.

Mathematical models

The most basic micromechanics models are those of Voigt and Reuss, which allow the determination of longitudinal (E1) and transverse (E2) moduli of elasticity for unidirectional continuous fibre composites. They take the form of a rule of mixture (Voigt) and an inverse rule of mixture (Reuss), permitting predictions of the upper and lower bounds of the elastic modulus, respectively. The Voigt model was employed in this study to establish a theoretical upper limit for the tensile modulus of rPET composites:

where \(\:{E}_{t}^{F}\) and \(\:{E}_{t}^{M}\) are the fibre and matrix tensile moduli and \(\:{V}^{F}\)is a volume fraction of fibres.

For short-fibre composites, a modified version of the Voigt model, known as the modified rule of mixtures, is used to determine the tensile modulus of elasticity:

Equation (4) was rearranged to calculate Fibre Tensile Modulus Factor (FTMF)20 for the tested rPET composites:

This parameter constitutes a simplified measure of the reinforcement effectiveness, representing the net contribution of fibres to the elastic modulus (FTMF) of a composite.

A different approach to predicting the tensile modulus of short-glass fibre composites was proposed by Manera21:

This equation was developed for composites with a random fibre arrangement using a laminate analogy, along with Puck micromechanical formulation and Tsai-Pagano invariants. Manera specified that his model applied to composites with 0,1–0,4 fibre volume fraction and matrix Young’s modulus of 2–4 GPa. These requirements were satisfied by all the tested rPET composites, thus justifying the use of the Manera model in this work.

None of the above models consider the influence of fibre aspect ratio on the mechanical properties of short-fibre composites. The Halpin-Tsai model accounts for the dependence of the longitudinal and transverse elastic modulus of the composite on the fibre length and diameter:

where L/D is the fibre length to diameter aspect ratio. Herein, weight average fibre length (L = Lw) and nominal fibre diameter D = 14 μm were used to calculate (7). The model assumes a unidirectional fibre orientation. For randomly arranged fibres, the Tsai-Pagano equation using Halpin-Tsai E1 and E2 values can be applied22:

The fit of the Halpin-Tsai model and Tsai-Pagano equation to the tensile test results of rPET composites was evaluated in this research.

Results

Thermomechanical history

Differential scanning calorimetry was employed to examine the effect of the composite manufacturing methods on the degree of crystallinity, the presence of internal stresses, and the characteristic temperatures associated with the observed phase transformations. The results are summarised in Table 1.

The composites with 30 wt% and 40 wt% glass fibres exhibited similar levels of crystallinity (χ), which were higher than those of the matrix. However, a significant reduction in crystallinity was noted in the composite with a fibre content of 50 wt%. Its crystallinity was even slightly lower than that of the neat matrix. This decline may be attributed to the limited molecular mobility during the crystallisation process, caused by the excessively high fibre loading, which can restrict the available space for crystal growth and disrupt the orderly arrangement of polymer chains. The presence of glass fibres (30 and 40 wt%) promoted nucleation during cooling, thereby enhancing the crystallisation of PET. The melting temperature (Tm) showed only minor variations and remained typical for PET.

No increase in the glass transition temperature (Tg) was observed as the glass fibre content increased. On the contrary, the Tg of the neat polymer matrix was slightly higher than that of the composites. This behaviour may not necessarily indicate poor interfacial adhesion between the fibres and the matrix; instead, it could be attributed to increased segmental mobility resulting from chain scission of the polymer, possibly intensified by the presence of glass fibres during processing. It may also result from differences in the thermo-mechanical history of the samples, particularly considering that the unreinforced rPET specimens exhibited significant flexibility upon demoulding and were prone to deformation, necessitating manual straightening prior to further characterisation. The absence of a detectable glass transition in the DSC trace of the 50% fibre composite may result from the reduced polymer fraction, which limits the measurable heat capacity change (ΔCp) at Tg.

The DSC thermograms of all samples (Fig. 1) exhibited a single, well-defined melting peak typical for PET. Only the glass transition and melting transitions were observed; no cold crystallization peaks were detected in any of the samples. No effect of enthalpy relaxation was observed; no extensive internal stress resulting from processing parameters was detected for any of the materials. However, the presence of a crystalline phase and the fibres in the composites could have hindered stress relaxation during the DSC heating process.

The factors related to the fibres were recognised based on burn-off test results and microscopic observations. There was a high consistency between the measured fibre weight fraction (actual filler content) and the assumed filler content (Table 2). This indicated that the dosing of the fibres during the compounding process was accurate. Isolating GF from the matrix also enabled the determination of the fibre length distribution (FLD). The FLD of thus manufactured composites is typically characterised by either a Weibull or a log-normal distribution23. For the tested rPET composites, the greater the fibre content, the more the FLD aligned with the log-normal distribution. However, selecting a single value to represent the FLD is more dependent on the significance of the influence of longer and shorter fibres on composite properties than on the type of distribution. By analogy to the molecular weight distribution of a polymer, the weight average fibre length (Lw) is more meaningful for predicting mechanical behaviour than the number average fibre length19. Thus, the obtained Lw values (Table 2) were further utilised to calculate the modulus of elasticity of the composites using the Halpin-Tsai model. With an increasing GF volume fraction, Lw decreased almost linearly. The Lw values corresponded closely to fibre aspect ratios ranging from 14 to 25, for a nominal fibre diameter of 14 μm.

Characterisation of mechanical properties

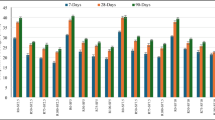

In general, there was a significant improvement in tensile strength and modulus, as well as in flexural strength and modulus, compared to the unfilled matrix (Table 3). The tensile test results revealed that adding GF to rPET ensured the most positive effect, increasing the elastic modulus from 2980 MPa for rPET to 18950 MPa for rPET50GF (a maximum increase of 536% was obtained).

A comparable increase in modulus and strength was observed in both the flexural and tensile test results – a maximum increase of 465% in flexural modulus and 152% in flexural strength was achieved for the rPET50GF composite.

Introducing fibres into the matrix reduced the tensile strain at break, while the reduction was more pronounced in the flexural test results. This effect is clearly illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows representative tensile and flexural curves of the tested materials.

Although the tensile and flexural strain at break decreased with the increasing amount of GF, the opposite trend in deformability changes was observed in the case of impact strength. The unnotched Charpy impact strength of 30–50 wt% GF-filled rPET was 10–50% higher than that of unfilled rPET. The positive effect of improving impact strength by adding fibres to a brittle matrix arose from the initiation of multiple matrix cracks and fibre pull-outs. It was assumed that these were the main mechanisms to increase energy dissipation capacity24.

In addition to standard static mechanical tests and impact strength measurements, abrasion tests were conducted. The smaller the difference in mass and volume, the more resistant the materials were to abrasion. As illustrated in Table 3, an increase in fibre content resulted in a slight decrease in abrasion resistance. However, the values remained moderate and still within an acceptable range of performance. The materials tested exhibited relative resistance to abrasion.

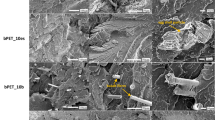

Obtaining favourable mechanical properties was associated with sufficient adhesion between the fibres and the matrix. This was confirmed by microscopic observations conducted on tensile fracture surfaces of the composites (Fig. 3). Regardless of fibre content, there were no voids present between the fibres and the matrix, and the visible fibre fragments were partially covered by a layer of matrix (Fig. 3 (b), (d), (f)). A well-developed fracture surface was observed across the entire cross-section of the composites (Fig. 3 (a), (c), (e)). Microscopic images confirmed a homogeneous distribution of fibres in all tested composites. The fracture surfaces were brittle, and a moderate number of voids left by pulled-out fibres were visible.

A micromechanics-based evaluation of reinforcement effectiveness

The effectiveness of reinforcement and the overall composite quality were assessed by comparing experimental data with model predictions and literature values for FTMF. Generally, the Halpin-Tsai (H-T) model shows a strong correlation with experimental results for the longitudinal modulus of short-fibre composites by considering the geometric parameters of the fibres25. However, this model assumes a unidirectional arrangement of fibres, which is not entirely applicable to injection-moulded samples or products26. It is often observed in the literature, particularly that dedicated to natural fibre composites, that the experimental results of injection-moulded materials can be well-fitted to the Tsai-Pagano (T-P) equation results derived for randomly oriented fibres27,28,29. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the elastic modulus of the tested rPET/GF composites exhibited values intermediate between the H-T model for parallel and H-P for randomly arranged fibres, but considerably closer to the E1 H-T model (the experimental results were approximately within three-quarters of the range between the model results for random and longitudinal fibres). This indicates a significant positive influence of the shell layer (where the primary direction of the fibre arrangement coincides with the main direction of material flow in the mould cavity) on the mechanical properties of the composites and justifies the high degree of reinforcement obtained. The consistency of the linear nature of the results derived from the H-T model and experimental data confirms the accuracy of describing the geometric and mechanical parameters of the tested material components.

The results obtained for the Manera model (Fig. 4) were slightly higher than those calculated from the T-P equation. This was somewhat expected, as Manera assumed the use of his model for composites with a high aspect ratio (L/D > 300), i.e., over ten times greater than that of the tested composites. Nonetheless, due to the similar results, both models could initially be used to predict the stiffness of the rPET/GF composites if a more random arrangement of fibres were achieved (e.g., thick cross-sections). It is worth emphasising that the Manera model is significantly simpler, as it does not require specifying the length or diameter of the fibres.

The values calculated using the Voigt model represent the theoretical maximum obtainable for the rPET/GF system, specifically for continuous fibres oriented parallel to the direction of force. The Voigt model is considered an upper limit for the elastic modulus if the composite constituents are not near their incompressibility limit30. The results obtained for disoriented short fibres were lower than the model predictions by 21–38%. This difference increased with the rising volume fraction of fibres due to increased fibre fragmentation (Table 1; Fig. 4). It should be noted that the achieved level of reinforcement concerning stiffness was very satisfactory for injection moulded short fibre composites.

To compare the reinforcement effectiveness of the tested system with other structural composites, the overall contribution of the fibres to the composite modulus of elasticity should be evaluated. The Fibre Tensile Modulus Factor (FTMF) serves as a valuable parameter for this assessment, calculable from the modified rule of mixtures (Voigt model) and tensile test results. FTMF can be derived from data on the tensile modulus of the matrix, the composite, and the volume fractions of the constituents. It is particularly beneficial for natural fibre-reinforced composites, where determining the intrinsic elastic modulus of the fibres poses a challenge20,27,28,29. Nonetheless, its applicability to other types of reinforcement remains justified due to the simplicity of its determination. FTMF is typically expected to be approximately constant, regardless of the fibre volume fraction. For the tested composites, FTMF was approximately 48.5 GPa, as indicated by the slope of the regression curve in Fig. 5.

Discussion

The analysis of the presented results enables the integration of experimental findings into a broader context, addressing both the mechanical and thermal performance of the composites and their relevance for construction applications, particularly in anchoring systems. The discussion also considers key aspects of long-term durability and the sustainability of the tested materials.

For all composite formulations, the addition of AR GF produced the expected beneficial effects on both processing and properties. During injection moulding, the fibres improved processability by reducing cycle time and imparting sufficient stiffness to the moulded parts, allowing for deformation-free demoulding, even at high fibre loadings. This was a crucial practical advantage, given the low viscosity and brittleness of rPET matrices. The thermal history analysis based on DSC results indicateed the nucleating effect of the fibres. The matrix of the composites achieved a degree of crystallinity comparable to or even higher than that of neat PET at the same mould temperature. The composites were found to be well-crystallised, with no evidence of cold crystallisation, which is favourable for maintaining dimensional and shape stability of the final moulded parts.

Regarding the mechanical properties, the composites exhibited a very satisfactory level of stiffness, with elastic moduli comparable to or even exceeding those reported in the literature for similar rPET-based systems reinforced with E-glass fibres. For comparison, Mondadori et al. reported lower tensile modulus values, in the range of approximately 12–14 GPa, for rPET/GF composites containing 30–40 wt% E-glass fibres (10 μm in diameter) and exhibiting a similar degree of crystallinity (33–38%)8. The tensile strength of their best-performing compositions was comparable to that of the present study, reaching 120–140 MPa. Similarly, Kráčalík et al. reported a tensile strength of approximately 120 MPa and a tensile modulus of nearly 14 GPa for rPET composites reinforced with 30 wt% E-glass fibres (10 μm in diameter)9. De M. Giraldi et al. reported a tensile modulus of 6–9 GPa for rPET composites with 30 wt% E-glass fibres (11 μm in diameter) with a much lower degree of crystallinity (~ 20%), while the tensile strength was not reported and the mould temperature was not specified11. Improving tensile strength is considerably more challenging for composites with non-homogeneous recycled matrices than improving the modulus of elasticity, which is less sensitive to internal flaws. Nevertheless, the tensile strengths achieved in our research — particularly at 30–40 wt% fibre content — were high, falling within or even above the range reported for commercial PET composites containing 20–50 wt% GF (typically 80–180 MPa, occasionally exceeding 200 MPa20. The strength of the composites increased significantly with 30–40 wt% AR-glass fibres, whereas at 50 wt% the improvement was less pronounced due to fibre fragmentation and intensified fibre–fibre interactions at high fibre loadings.

The mechanical tests were complemented by microstructural analysis, which enabled the evaluation of the reinforcement effectiveness through the Fibre Tensile Modulus Factor (FTMF), which was approximately 48.5 GPa. Results from Mondadori et al.8 indicated similar or slightly lower FTMF values for rPET/GF composites. For rPET composites containing 20, 30, and 40 wt% of E-type GF, the FTMF values were 45, 50, and 43 GPa, respectively. Lower FTMF values were often reported for GF-reinforced composites based on polyamide (PA), polypropylene (PP), or polybutylene terephthalate (PBT). For instance, FTMF for GF-reinforced PP composites has been reported as 32–34 GPa20,27,28,29, while S-type GF-reinforced PA and PBT composites exhibited FTMF values of 28 and 32 GPa, respectively31.

The weight-averaged fibre length decreased with increasing fibre content. Despite this reduction, the fibre–matrix interface remained effective, as indicated by both the mechanical results and microscopic observations. SEM images of fracture surfaces revealed a homogeneous fibre distribution, good fibre–matrix adhesion, and the absence of voids, which are often a problem in heterogeneous post-consumer recycled materials.

A challenge of the investigated composites was their brittleness, which was evident in both impact tests and static mechanical tests, where limited energy to failure (toughness, represented by the area under the tensile or bending curve) was observed. This behaviour contrasts with classical PET composites using virgin PET matrices, where the matrix itself is ductile and can reach elongations of up to approximately 50%, while the addition of fibres typically reduces this ductility. In the case of the rPET composites studied here, the matrix was inherently brittle; however, the incorporation of GF significantly improved impact resistance. The impact strength of the composites fell within the range typical for commercial virgin PET composites. The range is 20–70 kJ/m2 for Celanese Rynite®, Envalior Arnite® grades with 20–50 wt% GF)32.

In analysing the results of the mechanical tests, it is important to remember that the tested materials were recyclates based on bottle-grade PET, which is a demanding material to process. The results should be considered satisfactory. The standard deviations from the test results for all the tested materials were small, indicating the replicability of the sample composition and the stability of processing parameters.

The potential applications for these materials, which are being investigated by our research group, are very broad. Focusing on load-bearing elements, we can list chain links33, anchor systems34, connectors17,18, and even bridge components35 that enforce interaction between the bridge structure and the ground. In this study, particular attention is given to anchor systems already manufactured from fibre-reinforced polymers (FRPs), which typically consist of a thermoset matrix reinforced with continuous fibres36. These include facade cladding anchors, bonded anchors embedded in cementitious grouts, and structural connectors subjected to tensile and shear loads. According to standard design guidelines for construction fixings37,38, composite anchors are expected to achieve tensile strength above 80–100 MPa, shear strength exceeding 60–80 MPa, and maintain bond integrity under sustained loading conditions. The composites characterised in this study, particularly those with 30–40 wt% AR-GF, reached tensile strengths of up to 140 MPa and flexural strengths of up to 234 MPa. These values significantly exceed typical tensile requirements and indicate good overall load-bearing performance. Composites containing 30–50 wt% GF safely surpassed the design thresholds for manufacturing anchors used in fastening facade cladding of buildings, as defined in our proprietary patents17,18. As noted in the Introduction, the selection of PET among thermoplastic matrices was justified for this application due to its favourable creep resistance, dimensional and shape stability, and other relevant performance characteristics. However, further research is needed to evaluate the performance of the manufactured composites under application-specific loading conditions, including long-term durability (creep, fatigue, and ageing resistance). As part of the ongoing LIDER research project38, the applicability of bonded anchors manufactured from the developed composites is being further evaluated for use in civil engineering, particularly in systems embedded in cementitious and rock substrates. The use of thermoplastic rPET allowed for complex anchor geometries to be realised through injection moulding and orientation-controlled design, enabling targeted reinforcement in critical load-bearing zones. For reliable lifetime prediction of short fibre-reinforced polymers, it is essential to account for local stress fields, fibre orientation anisotropy, stress concentrations, and the local variation of stress ratios39. Recognising that long-term performance depends strongly on geometry and boundary conditions, the current phase of the project includes dedicated fatigue, creep, and accelerated ageing tests aimed at validating the durability of application-specific designs. Ageing studies of the produced composites and anchors are in progress, including exposure in an ageing chamber and in alkaline environments. Pull-out behaviour is also investigated.In contrast to pultrusion, which limits the shape of anchors made with continuous fibres, injection moulding enables the design of mechanically interlocking geometries that enhance bonding with the substrate. As a result, the anchor’s shape may have a greater influence on bond performance than the intrinsic properties of the composite material. Moreover, injection moulding technology enables overmoulding and encapsulation34, which provides an opportunity to further enhance the tensile and shear strength of the components. This approach may prove particularly beneficial for structural applications that require complex stress states and high-performance anchorage. It is worth noting that, in the course of developing additional functionalities of the composites presented here, two patent applications have been submitted to the Polish Patent Office: “Thermoplastic Composite” (application no. P.452128) and “Method for Obtaining a Thermoplastic Composite” (application no. P.452131).

In the present study, no LCA or related environmental assessments were performed for the investigated composites. However, data provided by the rPET supplier, along with other literature evidence, support the sustainability potential of these materials. Recent LCA and MCI studies on PET recycling demonstrate significant environmental benefits of substituting virgin PET with recycled PET, with reductions of up to ~ 60% in greenhouse gas emissions and ~ 85% in fossil resource use, depending on allocation assumptions40. Earlier studies by Shen et al. reported more modest reductions (typically 20–30%), likely due to lower collection rates, less efficient recycling technologies, and more conservative system boundaries used in LCA modelling41. While the highest material value is retained in Bottle-to-Bottle recycling, and Bottle-to-Fiber routes also exhibit high circularity (MCI ~ 0.5–0.7 when fully optimised)40, our study highlights an alternative pathway: the use of 100% rPET in durable construction components. This approach aligns with circular economy principles by diverting rPET from packaging streams toward a high-value, long-life application. It should be emphasised that the construction industry is identified as a major contributor to global carbon emissions42. Therefore, the search for materials with a reduced carbon footprint is especially important in this particular sector. The Alpla Group, which owns PRT Radomsko—the supplier of rPET used in the present study—has received certification from EY denkstatt GmbH, confirming that their rPET has a carbon footprint of 0.45 kg CO₂-eq/kg, whereas the carbon footprint of virgin PET amounts to 2.15 kg CO₂-eq/kg. This represents a difference of 1.7 kg CO₂-eq/kg of material, corresponding to a 79% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions43. Food-contact rPET grades are widely available, alongside non-food-contact rPET grades that possess analogous processing and performance properties but have not undergone food safety testing and are therefore less expensive. These non-food-contact rPET grades represent promising candidates for the matrices of composites such as those investigated in this study.

Conclusions

The research results indicate the potential for using rPET reinforced with alkaline-resistant glass fibres (GF) in civil engineering as part of the green manufacturing trend. Mechanical tests demonstrated that GF significantly enhanced the properties of bottle waste-derived rPET, rendering it a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional engineering materials. The beneficial effects of modification with GF were observed for composites containing 30–50 wt% GF, particularly in terms of flow characteristics, crystallisation kinetics, tensile and flexural strength, elastic modulus, and abrasion resistance. The rPET/GF composites exhibited good fibre/matrix bonding. Compounding did not lead to excessive fragmentation of the fibres, which could cause a sudden decrease in strength parameters. Despite the relatively low aspect ratio, AR-GF enabled effective reinforcement of rPET compared to other structural thermoplastic composites. Regarding the micromechanical models tested, the tensile modulus of the composites closely aligned with the Halpin-Tsai longitudinal modulus, indicating a significant orientation of the fibres in the direction consistent with the primary injection direction. The introduction of fibres improved the impact strength without a notch, and it did not significantly affect the tensile strain at break. Admittedly, all tested materials were brittle, but to a degree similar to that of commercial PET composites. This work has demonstrated that the analysed rPET/GF composites can potentially be applied in broadly defined civil engineering, including injection-moulded anchoring systems designed for cementitious and rock substrates, owing to the straightforward method of composite preparation and their excellent mechanical properties. Furthermore, the utilisation of waste materials such as rPET aids in reducing the carbon footprint and aligns with the trend of green engineering and manufacturing, which has been strongly promoted in recent years.

Data availability

The datasets utilised and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Directive, E. U. 2018/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 94/62/EC on Packaging and Packaging Waste — European Environment Agency (2018).

Circular Economy for Plastics – European Study 2024. Plastic Europe, (2024).

Frounchi, M. Studies on degradation of PET in mechanical recycling. Macromol. Symp. 144, 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/MASY.19991440142 (1999).

Scelsi, L. et al. Review on composite materials based on recycled thermoplastics and glass fibres. Plast. Rubber Compos. 40, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1179/174328911X12940139029121 (2011).

Panowicz, R. et al. Properties of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) after thermo-oxidative aging. Mater. (Basel). 14, 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/MA14143833 (2021).

Karthik, G., Balaji, K. V., Venkateshwara, R. & Rahul, B. Eco-friendly recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate) material for automotive canopy strip application. SAE Tech. Pap. https://doi.org/10.4271/2015-01-1304 (2015).

Worku, B. G. & Alemneh Wubieneh, T. Composite material from waste poly (ethylene terephthalate) reinforced with glass fiber and waste window glass filler. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev. 16 https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2023.2169081 (2023).

Mondadori, N. M. L., Nunes, R. C. R., Canto, L. B. & Zattera, A. J. A. Composites of recycled PET reinforced with short glass fiber. J. Thermoplast Compos. Mater. 25, 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892705711412816 (2012).

Kráčalík, M. et al. Effect of glass fibers on rheology, thermal and mechanical properties of recycled PET. Polym. Compos. 29, 915–921. https://doi.org/10.1002/PC.20467 (2008).

Monti, M. et al. Enhanced impact strength of recycled pet/glass fiber composites. Polym. (Basel). 13, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM13091471 (2021).

Giraldi, A., Bartoli, J. R., Velasco, J. I. & Mei, L. H. I. Glass fibre recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate) composites: mechanical and thermal properties. Polym. Test. 24, 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLYMERTESTING.2004.11.011 (2005).

Benmokrane, B., Wang, P., Ton-That, T. M., Rahman, H. & Robert, J. F. Durability of glass fiber-reinforced polymer reinforcing bars in concrete environment. J. Compos. Constr. 6, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2002)6:3(143) (2002).

Peled, A., Bentur, A. & Mobasher, B. Textile Reinforced Concrete - Modern Concrete Technology Vol. 1, ISBN 9780367866914 (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017).

Paul, S., Gettu, R., Naidu Arnepalli, D. & Samanthula, R. Experimental evaluation of the durability of glass textile-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 406, 133390. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2023.133390 (2023).

TRL 4.0 Competition Results - Innovation Incubator. https://www.transfer.edu.pl/pl/aktualnosci,10,wyniki-konkursu-trl-4-0,1657.chtm (Accessed 27 Nov 2024).

Government Program. - Innovation Incubator 4.0 TRL. https://www.gov.pl/web/nauka/inkubator-innowacyjnosci-40 (Accessed 27 Nov 2024).

Byrdy, A., Majka, T. M. & Pielichowski, K. Anchor for Fastening Building Facade Cladding - Patent PL243713 2019.

Byrdy, A., Majka, T. M. & Pielichowski, K. Anchor for Fastening Building Facade Cladding - Patent PL243714 2019.

Kumar, K. S., Ghosh, A. K. & Bhatnagar, N. Mechanical properties of injection molded long fiber polypropylene composites, part 1: tensile and flexural properties. Polym. Compos. 28, 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.20298 (2007).

Serrano, A. et al. Study on the technical feasibility of replacing glass fibers by old newspaper recycled fibers as polypropylene reinforcement. J. Clean. Prod. 65, 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.003 (2014).

Manera, M. Elastic properties of randomly oriented short fiber-glass composites. J. Compos. Mater. 11, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199837701100208 (1977).

Affdl, J. C. H. & Kardos, J. L. The Halpin-Tsai equations: A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 16, 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.760160512 (1976).

Broughton, W. R. Characterization of Nanosized Filled Particles in Polymeric Systems: A Review. (2008).

Korczynskyj, Y., Harris, S. J. & Morley, J. G. The influence of reinforcing fibres on the growth of cracks in brittle matrix composites. J. Mater. Sci. 16, 1533–1547. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02396871 (1981).

Zhou, D. et al. A modified Halpin–Tsai model for predicting the elastic modulus of composite materials. AIP Adv. 14 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0160256 (2024).

Huang, D., Zhao, X. A. & Generalized Distribution Function of fiber orientation for injection molded composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 188 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.107999 (2020).

Oliver-Ortega, H. et al. Stiffness of bio-based polyamide 11 reinforced with softwood stone ground-wood fibres as an alternative to polypropylene-glass fibre composites. Eur. Polym. J. 84, 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURPOLYMJ.2016.09.062 (2016).

Espinach, F. X., Julián, F., Alcalà, M., Tresserras, J. & Mutjé, P. Alpha-Starch Composites Vol. 9 (2014).

Delgado-Aguilar, M. et al. Bio composite from bleached pine fibers reinforced polylactic acid as a replacement of glass fiber reinforced polypropylene, macro and micro-mechanics of the Young’s modulus. Compos. Part. B Eng. 125, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.05.058 (2017).

Liu, B., Feng, X. & Zhang, S. M. The effective Young’s modulus of composites beyond the Voigt estimation due to the Poisson effect. Compos. Sci. Technol. 69, 2198–2204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.06.004 (2009).

Mortazavian, S. & Fatemi, A. Effects of fiber orientation and anisotropy on tensile strength and elastic modulus of short fiber reinforced polymer composites. Compos. Part. B Eng. 72, 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.11.041 (2015).

MatWeb Advanced Search. Melt Flow / Charpy Impact, Unnotched / Tensile Strength, PET, GF. https://www.matweb.com/search/AdvancedSearch.aspx (Accessed 16 July 2024)

Ostrowski, K. A. & Spyrowski, M. Technical chains in civil and urban engineering: review of selected solutions, shaping, geometry, and dimensioning. Appl. Sci. 15, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137600 (2025).

Ostrowski, K. A. & Piechaczek, M. (eds) [In Press] Composite Bonded Anchor – Overview in the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions. Appl. Sci. (2025).

Spyrowski, M. M., Ostrowski, K. A. & Furtak, K. Transition effects in bridge structures and their possible reduction using recycled materials. Appl. Sci. 14, 11305. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142311305 (2024).

Ren, Y., Wang, H., Guan, Z. & Yang, K. Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 62 https://doi.org/10.1515/RAMS-2022-0287 (2023).

EAD 330499-00-0601 - Bonded Fasteners For Use In Concrete (2017).

ETAG 001 - Metal Anchors For Use In Concrete. European Organisation for Technical Approvals (2013).

Kanters, M. J. W., Douven, L. F. A. & Savoyat, P. Fatigue life prediction of injection moulded short glass fiber reinforced plastics. Procedia Struct. Integr. 19, 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROSTR.2019.12.076 (2019).

Chairat, S. & Gheewala, S. H. Life cycle assessment and circularity of polyethylene terephthalate bottles via closed and open loop recycling. Environ. Res. 236, 116788. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVRES.2023.116788 (2023).

Shen, L., Nieuwlaar, E., Worrell, E. & Patel, M. K. Life cycle energy and GHG emissions of PET recycling: change-oriented effects. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 16, 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11367-011-0296-4 (2011).

Labaran, Y. H., Mathur, V. S., Muhammad, S. U. & Musa, A. A. Carbon footprint management: A review of construction industry. Clean. Eng. Technol. 9, 100531. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLET.2022.100531 (2022).

Excellent CO2 Balance | PET Recycling Team - A Member of the ALPLA Group. https://petrecyclingteam.com/en/excellent-co2-balance (Accessed 24 July 2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to our industrial partners: Grupa Azoty SA, which assisted us with extrusion compounding and provided support and advice; KLGS Sp. z o.o. for helping us with the injection moulding of the samples and offering professional counsel; and Alpha Technology Sp. z o. o. for their cooperation in the production of anchors.

Funding

This research was funded by a project supported by the National Centre for Research and Development, Poland [Grant no. LIDER14/0270/2023 “Composite non-conductive chain with an anchoring system (COMPCHAIN)”] and as part of the government project Innovation Incubator 4.0 TRL [Number POIR.04.04.00-00-0004/15 entitled “Modification of the technology for manufacturing a non-conductive electric charge chain, especially an insurance chain on an industrial scale”] of the Republic of Poland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and review of the manuscript. K.A.O. was responsible for conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, writing, funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision. M.S. contributed to the conceptualisation, investigation, and writing. P.R. was involved in investigation, data analysis, visualisation, and both drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ostrowski, K.A., Romańska, P. & Spyrowski, M. Material properties of recycled PET composites for structural anchoring and other civil engineering applications. Sci Rep 15, 36550 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19291-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19291-1