Abstract

Yet studies fail to consider how a lack of concordance among sexual orientation, gender identity, and intent to marry or date a woman hinders the improvement of HIV prevention outcomes. We sought to explore the overlap of the three variables and examine associations between each aspect and HIV prevention outcomes among college students MSM. A cross-sectional study was conducted in six cities in Zhejiang province in 2022. All subjects were recruited by four community-based organizations, reporting sexual orientation, HIV knowledge, HIV self-testing, Post-exposure Prophylaxis(PEP), and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Among 671 participants, 43.8%(294/671) reported a gay identity along with a male identity and no intent to marry or date a woman. The structural equation model showed that the effect of sexual orientation on the intent to marry or date a woman is positive (β = 0.035, p< 0.001); After controlling 4 confounders, sexual orientation had a negative effect on HIV self-testing (β=−0.129, p < 0.01), HIV knowledge (β=−0.099, p < 0.01); There was partial mediating effect of marriage intention on the influence of sexual orientation on HIV knowledge (β = 0.021, 95CI%:0.001–0.046), have taken PEP (β = 0.019, 95CI%:0.002 ~ 0.040) and ever heard of PrEP (β=−0.023, 95CI%:−0.048–0.003). For college students MSM, sexual orientation may affect HIV prevention outcomes both directly and indirectly through attitudes toward marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

College students who are men and who have sex with men (MSM) have been markedly affected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic1,2,3. The prevalence of HIV infection among college students MSM has been calculated as 2–4%, which is 100 times that in other male students4. Zhejiang Province in southeast China has a low prevalence of HIV infection in the general population, but a high burden in MSM. college students MSM had an HIV higher positive rate, accounting for more than 90% of all student patients4. The high prevalence of HIV infection among college students MSM might lead to an HIV epidemic among their female sexual partners, which is another public health challenge.

The 95-95-95 strategy was developed by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and has been introduced in many countries5. Based on this strategy, HIV prevention outcomes, including abundant timely knowledge of HIV/AIDS status, access to HIV testing, Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP), Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), are important positive factors to reduce HIV transmission6,7. In China, PEP is more advanced than PrEP. For example, every city in Zhejiang Province has at least one PEP clinic with standardized services; However, PrEP is still only in the stage of publicity. Medicine can be purchased through Internet hospitals, and few offline hospitals have them.

These measures have greatly promoted HIV prevention measures and service for men who have sex with men, and their utilization rate over the last decade8,9,10. However, college students MSM have had poor access to medication and insufficient sources of information and resources related to HIV testing, PEP, and PrEP11,12. Therefore, to cope with changes in the epidemic, research on HIV prevention outcomes for college students MSM is important.

Sexual orientation and gender identity are independent fundamental characteristics of an individual’s sexual identity13. Sexual orientation refers to the enduring pattern of sexual or romantic intentions for and relationships with people with particular gender identities14. Gender identity refers to a person’s innermost concept of self as male, female, or something else and can be the same as or different from one’s physical sex15. The intention to marry or date a woman could indicate intention to have sex with a woman or it could indicate social norms to traditional marriage since gay marriage is not legal in China. Sex with a woman might be a much more accurate term. However, the number of college students MSM having sex with woman in this study was small, only seven subjects, accounting for 1.0% (unreported).

These three variables might be both interrelated and distinct from each other13,16. For instance, sexual orientation might affect one’s attitude to marrying or dating woman. The three variables are all related to being bisexual at some future point13,16. At the same time, there are also conflicts among the variables; for example, some gay men want to marry or date women. This could lead to new avenues of HIV transmission that need to be explored.

Previous studies have examined relationships between sexual orientation, gender identity, and HIV service utilization among MSM17,18, although few studies have identified the mode and size of the effects of the three variables on HIV prevention outcomes, especially in college students MSM. Limited studies were found in China. However, due to the significant differences in cultural, economic, and educational backgrounds between China and foreign countries, localization research should be vigorously carried out.

Inspired by the intersectionality framework19, we predicted that there would be internal relations in sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman among college students MSM. We also hypothesized that there are associations between sexual orientation, gender identity, attitude to marriage, and HIV prevention outcomes (i.e., HIV knowledge, HIV testing, PrEP, and PEP). Therefore, this study explored relationships among the three variables to identify the mode and size of the effect on HIV prevention outcomes.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study examined college students MSM between March and July 2022 in Zhejiang Province. Criteria for subject enrollment: male who has had anal or oral intercourse with a male; aged 18 years and older; studying in college or university; and consented to participate in the study.

Study design and data collection

College students MSM were enrolled by four local community-based organizations (CBOs) in Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jinhua, and Jiaxing, which serve more than 60% of all MSM in Zhejiang Province. In study Design, during the survey Design phase, 30 students participated in the modification of the survey questionnaire. These CBOs provide professional services such as HIV counseling, testing, and prevention interventions for local MSM, including college students MSM. Recruitment announcements were published through gay networks, such as the social application “Blued/WeChat/Tencent” and through the testing service studio of CBOs for MSM. Participants completed interviewer-administered surveys conducted by the CBOs through an electronic questionnaire. All participants were asked to scan a two-dimensional code and were directed to an electronic informed consent form. The electronic questionnaire was given after providing informed consent. All participants received face-to-face training before completing the questionnaire. Cellphone numbers were used to filter duplication, and no duplicated participants were found.

The sample size was calculated based on the rate of finding sex partners online, which ranges from 40 to 60%, with an α of 0.05. According to the formula for cross-sectional surveys: N = 400*(1-p)/p, the minimum sample size for this study was estimated at 600 people.

Measures

The three variables, sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman, were self-evaluated. To measure sexual orientation, participants were asked, “What do you think your sexual orientation is?” Four responses were provided: “gay”, “bisexual”, “straight”, and “uncertain”. To assess gender identity, participants were asked, “What do you consider your psychological gender to be?” There were four possible responses: “female”, “male”, “both”, and “uncertain”. For analytical purposes, we combined the responses “female”, “both”, and “uncertain” as “other”. intention to marry or date a woman was assessed by asking, “Do you plan to date or marry a woman in the future?”; participants could answer “marry a woman”, “date a woman”, “both”, or “neither”. For analytical purpose, we combined the responses “marry a woman”/”date a woman”/”both” as “yes”.

HIV prevention outcomes

Self-designed five statements were used to evaluate HIV knowledge: (1) Men who have sex with men are the most seriously affected by HIV in China; the answers were Right (correct)/Wrong/Don’t know. (2) Men not using condoms occasionally will not be infected with HIV; the answers were Right/Wrong (correct)/Don’t know. (3) Within 96 h after high-risk behavior, preventive medication can be administered, with the best effect within 2 h; the answers were: Right (correct)/Wrong/Don’t know. (4) Which of the following sexual roles is more likely to be infected with HIV? The answers were: Insertive/Receptive (correct)/Equal/Don’t know; (5) Does sexual use of stimulants increase the risk of HIV infection? The answers were: Right (correct)/Wrong/Don’t know. One point was given for each correct answer. The HIV knowledge score ranged from 0 to 5 and was divided into 0–4 and 5 for the analysis. The cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.482; the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) valule was 0.526.

PEP refers to “having taken medicine to prevent HIV infection after risky behavior”. The subjects were asked “Have you heard of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis?” and, “Are you willing to take preventive medicine before AIDS exposure?” The answers were: Yes/no/never heard. “Never heard” was defined as “never heard of PrEP”. The others were defined as “have heard of PrEP”. To assess recent HIV self-testing history the subjects were asked, “Until now, how many times have you been tested for HIV?” Specific numbers need to be filled in.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (number 2022-014-02). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) 25.0 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive analyses were used to describe the demographic characteristics of all college students MSM and HIV prevention outcomes. We examined the overlap of sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman by Chi-square tests. Univariate and backwards multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify associations between sexual orientation, gender identity, intention to marry or date a woman, and HIV prevention outcomes, controlling for four confounders (registered permanent residence (1-Zhejiang province, 2-Others), education level(1-Junior college, 2-Bachelor or Master’s), age(1–18–20, 2–21–23, 3-≧24), and monthly living expenses(1 − 0–1500,2-1501–2000,3-> 2000)). There are few missing data in this study, which were not included in the analysis.

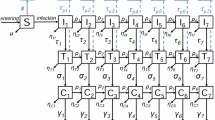

The mediation model used in this study refers to the research of Cabanas-Sánchez20. The path diagram is shown in Fig. 1. Based on the references and analysis above, we assumed that sexual orientation (X) has a direct effect on HIV prevention outcomes (Y), and an indirect effect on HIV prevention outcomes (Y) through the intention to marry or date a woman (M), in which intention to marry or date a woman plays a mediating role. The total effect (c) is divided into direct (c’) and indirect (ab) effects. c’ is the effect of X on Y by controlling M; a is the effect of X on M; b is the effect of M on Y by controlling X. e1, e2, and e3 are regression residuals. Using IBM SPSS AMOS 25.0 to construct structural equation models for the mediation effect analysis. The percentile bootstrap method was used to test the significance of the direct and mediating effects and to calculate the 95% CI in a model sampled 5000 times. The model was adjusted for the four confounders (registered permanent residence(1-Zhejiang province, 2-Others), education level(1-Junior college, 2-Bachelor or Master’s), age(1–18–20, 2–21–23, 3-≧ 24), and monthly living expenses(1 − 0–1500,2-1501–2000,3-> 2000)). P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Intermediate effect model diagram of sexual orientation, intent to marry or date a woman and HIV prevention-promoting outcomes showed the Intermediate effect model diagram of sexual orientation, intent to marry or date a woman and HIV prevention outcomes. The diagram was designed based on the results of Tables 2, 3 and 4. Structural equation models was constructed to verify whether the model is valid. The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see:.

Results

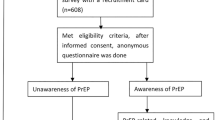

In total, 701 individuals initially enrolled in this study. Of these, 19 participants were under age of 18 and 682 (97.3%) were eligible and completed the questionnaire. Seven participants missing key information in the questionnaire were excluded. Of the remaining 675 participants, four who self-reported as heterosexual men were also excluded. Ultimately, a total of 671 college students MSM were analyzed.

Sociodemographic characteristics and HIV prevention outcomes

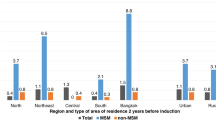

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics and the association between HIV prevention outcomes and sociodemographic characteristics for college students MSM in Zhejiang Province. Overall, 65.9% (442/671) reported that Zhejiang Province was their registered permanent residence; 69.3% (465/671) were currently pursuing a bachelor’s or Master’s Degree; their mean age was 21.5 (range 18–32) years; and 27.1% (181/671) had monthly Living expenses exceeding 2000 RMB. Most of the sample self-identified as “gay” (73.3%, 492/671); 76.2% (511/671) reported a male identity. One third (31.4%, 211/671) reported an “intention to marry or date a woman”.

Examining the status of HIV prevention outcomes, 16.2% (109/671) of the sample scored 5 points for HIV knowledge; 72.9% (476/653) reported engaging in HIV self-testing; 9.1% (61/671) reported having previously used PEP; and 84.5% (567/671) reported hearing about PrEP.

The proportion who “scored 5 points for HIV knowledge” differed by sexual orientation; the proportion who “have engaged in HIV self-testing” differed by age and sexual orientation; the proportion who “have taken PEP” differed by “intention to marry or date a woman”; the proportion who “have heard of PrEP” differed by registered permanent residence, education level, and intention to marry or date a woman. All the differences were significant (p < 0.05, chi-square test); Table 1.

Overlap of sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman

Table 2 shows the overlap across measures of sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman. Across the sample, 43.8% (294/671) reported a gay identity along with a male identity and no intention to marry or date a woman. Of the 211 who intended to marry or date a woman, 53.1% (112/211) were gay men and 27.0% (57/211) reported a female or other identity. Among gay men, about 22.8% (112/492) reported an intention to marry or date a woman. Of the 179 men who were bisexual or of uncertain sexual orientation, 55.3% reported an intention to marry or date a woman. We compared the above three variables pairwise using chi-square tests. This showed that 21.1% (104/492) of the gay group and 55.3% (99/179) of the bisexual/uncertain group intended to marry or date a woman (χ2 = 64.479, p < 0.001). No relationships between sexual orientation and gender identity or gender identity and intention to marry or date a woman were observed (p > 0.05).

Relationships between sexual orientation, gender identity, intention to marry or date a woman and HIV prevention outcomes

Tables 3 and 4 describe the results of univariate and multivariate associations between sexual orientation, gender identity, intention to marry or date a woman, and HIV prevention outcomes (HIV knowledge, have engaged in HIV self-testing, have taken PEP, and have heard of PrEP) adjusted for education level, age, registered permanent residence, and monthly living expenses. Here, bisexual/uncertain identity (aOR = 0.450, 95% CI: 0.258, 0.786, p = 0.005) and intention to marry or date a woman (aOR = 1.601, 95% CI: 1.012, 2.532, p = 0.044) were related to HIV knowledge. Bisexual/uncertain identity (aOR = 0.556, 95% CI: 0.380, 0.814, p = 0.003) was associated with self-testing for HIV compared with gay men. intention to marry or date a woman (aOR = 0.563, 95% CI: 0.366, 0.866, p = 0.009) was associated with having heard of PrEP. No associations between sexual orientation, gender identity, intention to marry or date a woman, and having taken PEP were observed. We also did not find significant associations between any measures of gender identity and HIV prevention outcomes.

Total, direct, and mediating effects of sexual orientation and intention to marry or date a woman on HIV prevention outcomes

After controlling for four confounders, the models revealed that sexual orientation had negative effects on HIV knowledge (β = − 0.099, p < 0.01) and HIV self-testing (β = − 0.129, p < 0.01). After controlling for sexual orientation, an intention to marry or date a woman had positive effects on HIV knowledge (β = 0.065, p < 0.05) and have taken PEP (β = 0.058, p < 0.05) and a negative effect on have heard of PrEP (β = − 0.071, p < 0.05). The effect of sexual orientation on the intention to marry or date a woman was positive (β = 0.035, p < 0.001). The bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the mediating effect of intention to marry or date a woman on HIV knowledge, have taken PEP, or heard of PrEP do not include 0 (Table 5).

Discussion

The topic was more discussed for special groups, such as homeless and unstably housed women, or black cisgender sexual minority men, and less specifically for MSM student groups21,22,23. Many studies have shown that sexual orientation is one of the factors influencing high-risk sexual behaviors of HIV infection, but less complex relationship models such as mediation effect have been considered. In this study, we explored the overlap of the three variables(sexual orientation, gender identity, intention to marry or date a woman) and internal relationship between them. We also examined associations between the three variables and HIV prevention outcomes, based on the mediation model.

Relationships between sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman

We found that for gay participants, roughly one quarter of gay men reported an intention to marry or date a woman, while almost half of bisexual/other sexual orientation men reported no intention to marry or date a woman. Redd Driver’s study revealed that only a small proportion of black sexual minority men reported overlap in their sexual identity, sexual attraction, and sexual behavior, which was lower than results of this study23. In this study, for those identified as male, almost half of them reported as gay and no intention to marry or data a woman. The divergence across aspects of sexual orientation among MSM may reflect the influence of oppressive intersecting macro-level stigmas (e.g., racism, homophobia, and biphobia)24,25. In China, people have a relatively limited understanding of sexual orientation, which could be affected by attitudes encouraged by traditional culture, such as a low tolerance for bisexual or gay people, and the feeling that a son should have a baby to carry on his family name26. This study provides quantitative results, but further research is needed to explore the factors causing disparity.

Using chi-square testing, we found a preliminary association between sexual orientation and an intention to marry or date a woman among college students MSM, while no relationship was found between gender identity and the other two variables. Research in China showed that those self-identified as bisexual reported a greater intention to marry or date a woman27. With social changes, however, the pressure from society and family is gradually decreasing, which is why half of the bisexual students in this study did not plan to marry or date a woman. Student identity might be another important reason why they had no intention of marrying or dating a woman.

We hypothesized that gender identity would be associated with sexual orientation and attitude toward marriage. The association between gender identity and sexual orientation among sexual minority groups have been widely discussed and have been shown to be related to each other in many countries such as Europe28,29, but this association was not found in this study, Compared to sexual orientation, people pay less attention to gender identity in China. In this social context, an individual’s understanding of their own gender is relatively limited and has not yet had an impact on sexual orientation or attitude regarding marrying or dating women.

Effects of sexual orientation, gender identity, and intention to marry or date a woman on HIV prevention outcomes

Our study provided a clear picture of the impact of sexual orientation, gender identity, and the intention to marry or date a woman on HIV prevention outcomes. Our results suggest that sexual orientation has a direct effect on HIV knowledge and HIV self-testing. Those reporting bisexual/uncertain sexual orientation tend to undergo less self-testing and have less HIV knowledge, in contrast to a study of SMM23, but consistent with other studies23,30. In Zhejiang Province, the majority of HIV information transmission and HIV self-testing services are supported by CBOs and less by voluntary counselling and testing clinics. Compared with gay men, bisexual men and bisexuals have fewer opportunities and less frequent contact with CBOs, especially college students. Furthermore, bisexual students tended to be more afraid of having others discover their sexual orientation31. Those who had disclosed their sexual orientation to some or all of the members of their network were more aware of PrEP than their counterparts, who reported lower levels of disclosure32. The unique health and intervention needs of these subjects should be studied, especially for those who face barriers when accessing services.

We also found a mediating effect of sexual orientation on HIV knowledge through intention to marry or date a woman in another direction. Intending to marry a woman implies taking on more responsibility to protect their spouse and baby, and that more attention is paid to the acquisition of HIV knowledge27. However, there was no mediating effect of sexual orientation on HIV self-testing through intention to marry or date a woman. The most likely reason for this finding might be that many factors affect the use HIV self-testing, such as the accessibility of the service or stigma33,34.

It should be noted that since the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the HIV knowledge scale is only 0.482, its internal consistency is not particularly high. This may indicate that the results only reflect part of the knowledge level rather than the overall knowledge level. In this study, Only 40% of respondents answered Question 3 correctly, while over 90% answered Question 2 correctly.

PEP and PrEP are effective at preventing HIV infection. However, no study has examined the effects of sexual orientation on the acceptance or use of PrEP/PEP among college students MSM. However, many studies have revealed a relationship between sexual orientation and PrEP among MSM in general35,36. Research on American MSM showed that bisexual participants were 2.1 times less likely to be prescribed PrEP than gay men35.

Our multivariate logistic regression analyses showed a mediating effect of sexual orientation on having taken PEP and having heard of PrEP via intention to marry or date a woman, while no direct effect of sexual orientation on the outcomes was observed. intention to marry or date a woman was the key factor. Interestingly, the effect of intention to marry or date a woman had opposite effects on having heard of PrEP and having taken PEP. College students MSM who reported an intention to marry or date a woman were more likely to report having taken PEP and having never heard about PrEP. We believe that this is related to service accessibility and urgency37. In Zhejiang, approximately 90 hospitals are designated PEP hospitals, with at least one in each county. These institutions have unified management requirements for medication and follow-up. By contrast, PrEP does not have such standardized management. Furthermore, less contact with CBOs and insufficient key information on HIV in schools may explain their insufficient information on PrEP38.

Our findings suggest that a comprehensive examination of sexual orientation among college students MSM is urgently required, not just by means of one or two measures in observational and interventional HIV-related research. Public health researchers have failed to address the health risks associated with sexual orientation adequately, and the need for corresponding differentiated intervention policies among college students MSM. To improve the effectiveness of intervention, identifying unique subgroups and developing tailored programs that address multi-level factors may help improve the situation among college students MSM.

The study findings should be viewed in the context of the study’s limitations. Firstly, it was a cross-sectional study, which weakens the ability to make causal inferences. Secondly, the CBOs used convenience sampling, which is not representative of all college students MSM. We increased the variety of sample sources (online and offline) to offset this deficiency. Thirdly, self-reported data may lead to information bias. Face-to-face training before investigation may reduce the bias. Fourthly, the internal consistency of the HIV knowledge assessment scale is relatively low, and a more scientifically designed knowledge scale needs to be developed. Fifthly, there is a possibility of residual confounding given that we only controlled for four individual-level factors in the multivariate models. Future longitudinal studies should control for more confounders, including network-level and structural factors, when examining associations between sexual orientation and HIV prevention outcomes.

Conclusions

Currently, MSM students in southeastern cities of China face conflicts in their sexual orientation, gender identity, and marital attitudes. Sexual orientation had a direct effect on HIV knowledge, HIV self-testing. intention to marry or date a woman had a mediating effect on HIV knowledge, uptake of PEP and ever heard of PrEP. HIV prevention services should be provided specifically for different groups of MSM students, such as more knowledge and testing services for those bisexual and intend to marry or date a woman, and PrEP knowledge training for those with no intention to marry or date a woman.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths: Firstly, very few studies have explored the relationship between the sexual.

orientation, sexual behavior, and marital attitudes of college students MSM. Secondly, the structural equation model was used to identify the direct effect, mediating effect and the size of the impact between the sexual orientation, sexual behavior, and marital attitudes.This is a more in-depth study.

Limitations: Firstly, it was a cross-sectional study, which weakens the ability to make causal inferences. Secondly, convenience sampling was used, which is not representative of all college students MSM. Thirdly, self-reported data may lead to information bias. Fourthly, there is a possibility of residual confounding given that we only controlled for four individual-level factors in the multivariate models.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- CBOs:

-

community-based organizations

- PEP:

-

Post-exposure Prophylaxis

- PrEP:

-

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Product and Service Solution

References

Milligan, C., Cuneo, C. N., Rutstein, S. E. & Hicks, C. Know your status: results from a novel, student-run HIV testing initiative on college campuses. AIDS Educ. Prev. 26, 317–327 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Predictors of HIV and syphilis among men who have sex with men in a Chinese metropolitan city: comparison of risks among students and non-students. PLoS One. 7, e37211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037211 (2012).

Li, M. et al. HIV-positive men are more likely to be hyper linked within college student social network - northeast china, 2017–2018. China CDC Wkly. 4, 951–955 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. The first 90: progress in HIV detection in Zhejiang province, 2008–2018. PLoS One. 16, e0249517 (2021).

Gupta, S., Granich, R. & Williams, B. G. Update on treatment as prevention of HIV illness, death, and transmission: sub-Saharan Africa HIV financing and progress towards the 95-95-95 target. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 17, 368–373 (2022).

Choi, E. P. H., Wong, J. Y. H. & Fong, D. Y. T. Disparities between HIV testing levels and the self-reported HIV-negative status of sexually active college students. J. Sex. Res. 56, 1023–1030 (2019).

Simon, K. A. et al. HIV information avoidance, HIV stigma, and medical mistrust among black sexual minority men in the Southern united states: associations with HIV testing. AIDS Behav. 28, 12–18 (2024).

Molin,a, J. M. et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre- exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 4 (9), e402–e410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30089-9 (2017).

O’Donnell, S., Tan, D. H. S. & Hull, M. W. New Canadian guideline provides evidence-based approach to non-occupational HIV prophylaxis. CJEM 21, 21–25 (2019).

De, B. G. J. et al. Is reaching 90-90-90 enough to end AIDS? Lessons from Amsterdam. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 14, 455–463 (2019).

Calabrese, S. K. et al. A closer look at racism and heterosexism in medical students’ clinical decision-making related to HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): implications for PrEP education. AIDS Behav. 22, 1122–1138 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Cascade analysis of awareness, willingness, uptake and adherence with regard to PrEP among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in china: A comparison between students and non-students. HIV Med. 25, 840–851 (2024).

Bjarnadottir, R. I., Bockting, W., Trifilio, M. & Dowding, D. W. Assessing sexual qrientation and gender identity in home health care: perceptions and attitudes of nurses. LGBT Health. 6, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0030 (2019).

Lhomond, B., Saurel-Cubizolles, M. J. & Michaels, S. A multidimensional measure of sexual orientation, use of psychoactive substances, and depression: results of a National survey on sexual behavior in France. Arch. Sex. Behav. 43, 607–619 (2014).

Steensma, T. D., Kreukels, B. P. C. & de Vries, A. L. C. Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. Gender identity development in adolescence. Horm. Behav. 64, 288–297 (2013).

Khayambashi, S. et al. Gender identity and sexual orientation affect health care satisfaction, but not utilization, in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. Relat. Disord. 37, 101440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.101440( (2020).

Datta, D., Dange, A., Rawat, S., Kim, R. & Patel, V. V. HIV testing by gender identity among sexually active transgender-, intersex-, and hijra individuals reached online in India. AIDS Behav. 27, 3150–3156 (2023).

Closson, K. et al. HIV leadership programming attendance is associated with PrEP and PEP awareness among young, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in vancouver, Canada. BMC Public. Health 19, 429 ; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6744-y(2019).

Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public. Health. 102, 1267–1273 (2012).

Cabanas-Sánchez, V. et al. Associations of total sedentary time, screen time and non-screen sedentary time with adiposity and physical fitness in youth:the mediating effect of physical activity. J. Sports Sci. 37, 839–849 (2019).

Timmins, L. et al. Sexual identity, sexual behavior and pre-exposure prophylaxis in black cisgender sexual minority men: the N2 cohort study in Chicago. AIDS Behav. 25, 3327–3336 (2021).

Flentje, A., Brennan, J., Satyanarayana, S., Shumway, M. & Riley, E. Quantifying sexual qrientation among homeless and unstably housed women in a longitudinal study: identity, behavior, and fluctuations over a three-year period. J. Homosex. 67, 244–264 (2020).

Driver, R. et al. Sexual orientation, HIV vulnerability-enhancing behaviors and HIV status neutral care among black cisgender sexual minority men in the deep south: the N2 cohort study. AIDS Behav. 27, 2592–2605 (2023).

Brewer, R. et al. An exploratory study of resilience, HIV-related stigma, and HIV care outcomes among men who have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV in Louisiana. AIDS Behav. 24, 2119–2129 (2020).

Baugher, A. R. et al. Black men who have sex with men living in States with HIV criminalization laws report high stigma, 23 U.S. Cities, 2017. AIDS 35, 1637–1645 (2021).

Wen, G. & Zheng, L. Relationship status and marital intention among Chinese gay men and lesbians: the influences of minority stress and culture-specific stress. Arch. Sex. Behav. 49, 681–692 (2020).

Wu, W. et al. Potential HIV transmission risk among spouses: marriage intention and expected extramarital male-to-male sex among single men who have sex with men in hunan, China. Sex. Transm Infect. 96, 151–156 (2020).

Cilveti-Lapeira, M., Rodríguez-Molina, J. M. & López-Trenado, E. Key aspects in the development of gender identity and sexual orientation according to trans and gender diverse people: a qualitative approach. Cult. Health Sex. 27, 992–1006 (2025).

Morandini, J. S., Menzies, R. E., Moreton, S. G. & Dar-Nimrod, I. Do beliefs about sexual orientation predict sexual identity labeling among sexual minorities? Arch. Sex. Behav. 52, 1239–1254 (2023).

Kamusiime, B. et al. Take services to the people: strategies to optimize uptake of PrEP and harm reduction services among people who inject drugs in Uganda. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 19 (13). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-024-00444-y (2024).

Sun, C. J., Tobin, K., Spikes, P. & Latkin, C. Correlates of same-sex behavior disclosure to health care providers among black MSM in the united states: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 31, 1011–1018 (2019).

Watson, R. J., Eaton, L. A., Maksut, J. L., Rucinski, K. B. & Earnshaw, V. A. Links between sexual orientation and disclosure among black MSM: sexual orientation and disclosure matter for PrEP awareness. AIDS Behav. 24, 39–44 (2020).

Luo, W. et al. Development of an agent-based model to investigate the impact of HIV self-testing programs on men who have sex with men in Atlanta and Seattle. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 4, e58. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.9357.1 (2018).

Kwan, T. H., Chan, D. P. C., Wong, S. Y. S. & Lee, S. S. Implementation cascade of a social network-based HIV self-testing approach for men who have sex with men: cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e46514. https://doi.org/10.2196/46514 (2023).

Carter, G., Staten, I. C., Woodward, B., Mahnke, B. & Campbell, J. PrEP prescription among MSM U.S. Military service members: race and sexual identification matter. Am. J. Mens Health. 16, 15579883221133891. https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883221133891 (2022).

Owens, C. et al. Facilitators and barriers of Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among rural men who have sex with men living in the Midwestern U.S. Arch. Sex. Behav. 49, 2179–2191 (2020).

Nguyen, L. H. et al. A qualitative assessment in acceptability and barriers to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: implications for service delivery in Vietnam. BMC Infect. Dis 21, 472 ; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06178-5(2021).

Blair, K. J. et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis use, HIV knowledge, and internalized homonegativity among men who have sex with men in brazil: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 6, 100152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100152 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of four local community-based organizations (the Coastal, Glowworm-light, Love, and Blue-sky public welfare groups) for their assistance with enrollment and data collection for the study and thank the participants who volunteered their time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. designed the study, conducted the statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript, drew the figure, and revised the manuscript. X. Z, J. J., Y.X., J.X. Y., W. C. took part in the data collection and quality control. X.H. P., C.L. C. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Zhou, X., Jiang, J. et al. The effect of sexual orientation, gender identity, and marital intention on HIV prevention outcomes among MSM students in Southeast China. Sci Rep 15, 35338 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19336-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19336-5