Abstract

This research introduced a cost-efficient and eco-friendly sustainable geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane produced using a non-hydrothermal technique optimized for treating textile wastewater. A new geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane for microfiltration (macroporosity) was generated by activating metakaolin with sodium hydroxide and silica fume. The design of the experiment methodology (full factorial and response surface methodology) was used to identify the most effective parameters and optimize membrane separation performance. The optimum membrane showed the maximum normalized permeability and turbidity reduction of 0.57 and 97.98%, respectively, at 1.2 bar pressure, 59.6 °C feed temperature, and 1.73 L/min. Fouling analysis utilizing resistance-in-series indicated that membrane resistance (57.04%) and cake layer resistance (26.5%) were the primary contributors to overall filtration resistance. Among the four analyzed fouling models (Hermia models), the cake filtration model is the most appropriate for calculating the permeate flux of real wastewater filtration. Removal of the cake layer and backwashing with distilled water effectively regenerated the membrane, restoring over 97.4% of the initial flux and around 99.5% of turbidity reduction across four successive cycles. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and elemental mapping validated the structural integrity and cleanability of the membrane, while performance remained consistent across repeated filtration-regeneration cycles. In comparison to traditional ceramic membranes, the engineered geopolymer-zeolite composite exhibited comparable separation efficiency, easy fabrication free of sintering, and significant potential for industrial wastewater recovery applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is essential to human well-being and survival to have access to water, and many industries depend on it. Various economic and human activities put pressure on water resources1. One part of developing and managing water resources is wastewater reclamation and reuse, which offers a creative and different choice for agriculture, municipalities, and industries2. Water recycling was considered a superior solution for water shortages due to cheaper costs and on-site wastewater treatment3. Due to increased wastewater reuse studies, membrane separation processes have advanced dramatically in recent years4. Microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), and reverse osmosis (RO) are the four categories of pressure-driven membrane processes that are available, depending on the size of particles rejected by the porous membranes5,6,7,8.

Compared to polymeric membranes, ceramic membranes have exhibited better performance, longer-lasting service, stronger mechanics, and more heat and chemical resistance. However, ceramic membranes have a higher production cost than common polymeric ones9.

The capabilities of the ceramic membrane make it possible to use ceramic MF as a pretreatment process before NF and RO10,11. The performance of NF decreases over time due to concentration polarization and fouling, posing significant problems for continuous operation and increasing costs12. The presence of fouling is a serious hindrance to the common use of nanofiltration technology; however, it could be reduced by using MF as a pretreatment, which decreases bacteria, colloids, and turbidity levels. Furthermore, MF prevents a long-term decline in NF flux, significantly impacting cost12,13.

It should be noted that MF membranes are highly prone to being fouled by foreign species as a consequence of physical, biological, and chemical interactions between fouling components and the membrane surface14 in which the pollutants block membrane pores, reducing water flux and/or quality. Adsorption and precipitation of the fouling components on the membrane surface and in the membrane pores, totally or partially block membrane pores, resulting in flux decline and a decrease in the separation factors15.

The fouling and flux decline in the MF membranes are more considerable than in the other membranes, like UF or RO, due to the unique morphology and pore character of the MF membranes. Fouling in microfiltration is unavoidable and is one of the major shortcomings of the microfiltration process that limits the permeate flux considerably15. The management of feed pretreatment and operating conditions, selecting membrane material/surface modification, and cleaning procedures are the strategies that can be employed in MF membrane filtration processes to reduce the membrane fouling16. Backwash is one of the most used methods for cleaning the fouled membranes to extend the membrane’s efficiency in operation time. This mechanical method involves the periodic reversible passing of permeate through the membrane from the permeate to feed side direction to remove contaminants that have been built up on the membrane’s surface (mostly as a cake-layer) as well as within the membrane pores. The benefits of backwash as a fouling control method include the absence of chemicals for membrane cleaning, the potential for a semi-continuous separation process, and the low cost and energy consumption17.

One of the challenges in membrane technology is selecting the best material for membrane fabrication. A sustainable, environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and energy-efficient membrane technology remains to be developed18. Two different strategies have been followed for this issue: application of bio-based polymeric membranes (BPMs) due to their acceptable performance and longevity within a suitable degradation profile18 and application of low-cost or waste materials for membrane fabrication as an upcycling strategy19,20,21.

In this regard, geopolymers have been considered as a membrane material due to their sustainability, low-cost precursors, high strength, free-sintering, and easy manufacture22 using an alkali-soluble aluminosilicate precursor such as metakaolin (MK), fly ash, and pozzolan, and an alkali activator23.

Furthermore, numerous recent studies have employed geopolymer-zeolite composites as membranes24,25,26. Geopolymer-zeolite composites are prepared via different methods including hydrothermal processes at 180 °C24,25, using circulating fluidized bed fly ash (CFBFA) as a precursor with hydrothermal treatment to separate Cr(VI) ions from water solutions24, hydrothermal method using alkali-activated fly ash to form a combination of crystalline analcime (ANA) zeolite and amorphous geopolymer25 and using the zeolite particles as seeds26 however, most of mesoporous and microporous membranes have been fabricated using hydrothermal and zeolite seeding methods24,25,26. Aside from the aforementioned methods for preparing geopolymer zeolite composites, an alternative approach exists that allows for the simultaneous production of zeolites and geopolymer without needing a hydrothermal process. This method functions at temperatures under 100°C and is affected by the SiO2/Al2O3 molar ratio, curing temperature, and alkali concentration27. In our previous work, the geopolymer and geopolymer-zeolite composite filters were prepared using MK as a precursor, activated by a mixture of SF and sodium hydroxide27. Silica fume (SF), as an inexpensive silica source, was used for the geopolymerization process and can act as a reinforcing agent in the geopolymer matrix, improving compressive strength and modifying pore size28.

In continuing our research on geopolymer membranes, in the current study, the membrane performance of geopolymer-zeolite composites was investigated through screening and response surface methodology design (RSM). The full factorial design determines the most effective variables among feed pressure, feed temperature, wastewater concentration, and feed flow rate on real textile industry wastewater permeability and turbidity reduction. The identified variables on membrane performance are optimized by applying central composite design (CCD) for RSM. For investigating the fouling of the fabricated membranes, a general fouling study is performed on the fabricated membranes, including determination of pure water flux, followed by membrane filtration of the desired wastewater and measuring the stable permeate flux, followed by a cleaning procedure (physical cake removal followed by back-washing), and finally measuring the pure water flux for the regenerated geopolymer-zeolite composites membrane. The procedure allowed us to determine the different fouling resistance formed for the fabricated membrane by the wastewater filtration. Best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which the fabrication of geopolymer-zeolite composite, application for filtration of real wastewater, and analysis of the fouling are performed.

Materials and experimental analysis

Materials

Silica fume (micro-silica) containing a specific 18 m2/g surface area, comprising 96.12 wt.% SiO2 was procured from Ferroalloy Company in Lorestan, Iran, and utilized as a silica source. MK, an aluminosilicate precursor, was obtained by calcinating kaolin from Zettlitz, Czech Republic, at 700 °C for 3 h. The XRF analysis of MK is given in Table S1. Dr. Mojallali Company (Tehran, Iran) supplied sodium hydroxide (NaOH) with a purity of 95%.

A sample of textile wastewater, with the initial turbidity of 155 NTU, containing many basic colors employed for coloring acrylic fibers, was donated by a textile company located in Tehran, Iran. The characteristics of textile wastewater are shown in Table S2. In Fig. S1, the particle size distribution of wastewater is presented. The distribution suggests that particles measuring 2.054 µm represent 10% of the total, particles measuring 9.679 µm for 50%, and particles measuring 87.725 µm for 90%. A small amount of the real textile wastewater was dried in an oven at 100°C to eliminate water, and the resulting powder was subsequently calcinated in a furnace at 700°C for three hours. The wastewater lacks organic matter, and only minerals remain after heating at 700°C. The outcomes of the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of the resulting particle (after calcination) are displayed in Table S3. Also, the loss of ignition (LOI) was 37%.

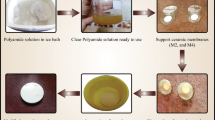

Preparation of geopolymer and geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane

First, an alkali activator was made by adding SF to the sodium hydroxide solution, and after 8 h at room temperature, a sodium silicate solution was obtained.

The prior publication27 indicates that variations in geopolymer preparation parameters, including the Na2O/Al2O3 molar ratio, the proportion of SF content, and the curing temperature, influence the phase structures, resulting in the formation of distinct phases (geopolymer and geopolymer-zeolite composite). These phase structures, therefore, affect the compressive strength and permeability of pure water. This paper examined the performance of five membranes selected based on criteria (compressive strength > 20 MPa and pure water permeability > 50 L/m2.h.bar) previously reported. The preparation parameters, phase structure (geopolymers and geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane), average pore size, and porosity of five membranes, as detailed in the previous article, are presented in Table 1. Table 1 shows that five membrane samples were designated as GP (or GPZ)-aS-bN-cT, where a, b, and c represent the Na2O/Al2O3 molar ratios, SF/MK ratios, and curing temperature, respectively. GP denoted the geopolymers, while the geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane was demonstrated by GPZ.

The Geopolymer paste was created by combining MK and an alkali activator; thereafter cast in a circular Teflon mold measuring 2.5 cm in diameter and 5 mm in height. Air bubbles were released from the samples by vibrating them. The membrane samples were subsequently stored in a humid chamber with a relative humidity of greater than 95% for three hours at 60 °C. Finally, a 24-h hydrothermal cure at 60 °C was applied after the samples were demolded.

Characterization methods

The membrane surfaces were examined using a scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Tescan Mira3, Czech Republic). Also, the chemical composition of the membrane samples was detected using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and elemental mapping analysis. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of samples was conducted using Spectrum One from PerkinElmer, USA, implementing the KBr pellet method throughout the wave number range of 400–4000 cm-1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) with CuKα radiation in the 2θ range of 5–80° and a step size of 0.01 was used for assessing the crystal structure of samples using a Bruker D8 Advance from Germany. The turbidity of wastewater is assessed utilizing Digimed (HDM-TU).

Membrane performance evaluation

Figure 1 depicts filtration experiments to investigate membrane performance using a microfiltration pilot in crossflow filtration mode at pressures ranging from 1.2 to 2 bar and a feed tank containing 4L of textile effluent. A PID-controlled electrical heater with a Pt-100 temperature sensing element was applied to control the feed tank temperature at the desired set point.

The feed pressure was governed by a diaphragm pump (Soft water YT-2000, Taiwan), and the feed flow rate before the membrane module was quantified using a rotameter (Shllj, China) and modified by a precision regulating needle valve. The membranes with a 4 mm effective thickness and a 25 mm diameter were installed in a module and sealed with an O-ring. To regulate the upstream membrane pressure, the rejection was directed via a back-pressure regulator (Parker Hannifin, USA).

Equation 1 was used to calculate the permeate flux J (L/h. m2), and the permeability Lp (L/h. m2.bar) was derived by measuring the change of water flux with transmembrane pressure (Eq. 2) 29.

The permeate volume (m3), the filtration time (h), and the filtration surface area (m2) are represented by the symbols V, t, and S.

Equation 3 was used to compute the turbidity reduction (RT)30.

where Tpermeate represents the permeate turbidity, and Tfeed represents the feed turbidity of the wastewater samples.

The Darcy and Hagen–Poiseuille for parallel cylindrical pores are the governing equations for the fabricated MF membranes31. The resistances-in-series model could be applied to determine the resistance against permeation (membrane and fouling resistances)32. The permeate flux is calculated by Eq. 433.

where Jv, ΔP, µ, and Rt represent the volumetric permeate flux (m3.m-2.s-1), feed pressure (Pa), permeate viscosity (Pa.s), and total hydraulic resistance to permeation (m-1), respectively.

Design of experiment (DOE)

Screening designs were used to determine which parameter impacts the separation membrane performance34. A 2k factorial design was used to evaluate the impact of parameters on the final responses and their interactions35. The feed pressure, feed temperature, feed flow rate, and feed concentration were considered effective parameters in the two levels. The study examined two responses: R1, which represents the normalized permeability measured by dividing the steady-state wastewater permeability by the pure water permeability, and R2, which represents the reduction in turbidity. When the membrane was exposed to wastewater, there was a significant decrease in flux at the beginning of each experiment, which could be attributed to the accumulation of particles on the membrane surface, fouling or blocking the membrane pore, until it reached a nearly steady-state flux (WWPf) after several minutes of operation. Minitab Software v.17 was used to design the experiments and analyze the results statistically. Thirty-two runs included 24 full factorials with two replications suggested by the software.

After identifying the most influential variables on responses, a central composite design (CCD) was utilized to optimize the responses using Minitab Software version 17. The parameters and their levels are shown in Table S4.

Fouling investigation

The resistance-in-series model indicates that the overall hydraulic resistance contains four resistances, as in Eq. 532.

where Rm, Rc, Rr, and Rir denote the membrane resistance, cake layer resistance, reversible fouling resistance, and irreversible fouling resistance, respectively. The deposited cake that develops on the membrane surface is linked to Rc. The backwashing process opens blocked membrane pores, which causes Rr. Rir occurs when particles are trapped or adsorb into membrane pores and cannot be opened after backwashing. Membrane resistance was obtained by determining the pure water flux at the desired pressure and temperature. Four main parameters must be considered when estimating resistance: steady-state pure water flux in the clean membrane, permeate flux in the wastewater, pure water flux after cake removal, and pure water flux after backwashing32.

Hermia introduced four fouling models for porous membranes: complete pore blocking, intermediate blocking, standard blocking, and cake formation. Equation 6 is the general Hermia equation for predicting the time-dependent permeate flux at constant pressure filtration32.

where V is the cumulative permeate volume, K and n denote the fouling mechanism constant coefficients (n = 2 for complete blocking, 1 for intermediate blocking, 3/2 for standard blocking, and 0 for cake formation)32. The slope and intercept of the linear form of the cumulative volume of permeate) vs. time can be used to calculate the model’s parameters. The regression coefficient (R2) was used to find the best match between experimental data and the model predictions32,36.

The hydraulic resistance values (Eq. 5) were calculated under the optimum conditions obtained in CCD, and the fouling mechanism (Eqs. 6) of the geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes was identified.

Results and discussion

Investigation of the performance of five membranes

In this section, the geopolymer and geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes with the specifications of Table 1 were prepared, and their performance was compared. Figure 2 displays the pure water permeability, wastewater permeability, permeation decline, and turbidity reduction of the five prepared membranes in Table 1. The highest pure water permeability was recorded for GPZ1-8S-1N-60 T (180 L/m2hbar), followed by GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T (144 L/m2hbar), which are geopolymer-zeolite composites. The minimum pure water permeability (110 L/m2hbar) was obtained for GP3-15S-1N-60 T.

Zeolite could form during the geopolymerization reaction at temperatures between 60 and 80 ℃. The nano nucleus could grow into large, extremely developed zeolite crystals through the geopolymer’s three-dimensional network structure37. Therefore, the pore size was increased in the geopolymer-zeolite composite, and increased pure water permeability. The study conducted by Shao et al.25 found that analcime zeolite in the geopolymer structure leads to larger channels or cavities. These channels had critical pore diameters ranging from 30–150 nm and 1–2 µm. This is believed to be advantageous as it helps to decrease membrane resistance and enhance water flux. The geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane (GPZ2-10S-1N-60T) comprises amorphous geopolymer and crystalline zeolite A. With an average pore size of 400 nm, this membrane acted as a microfilter without requiring hydrothermal treatment27. The membrane described in the Shao et al. 25 paper was specifically designed for nanofiltration and needed hydrothermal treatment.

The five membranes were utilized for treating textile wastewater at a pressure of 1.2 bar and a feed flow rate of 1 L/min at ambient temperature in a crossflow setup, and steady-state wastewater permeability is illustrated in Fig. 2. The highest observed steady-state wastewater permeability of 77 L/m2hbar was seen in GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T, while the lowest permeability of 55 L/m2hbar was recorded in GP5-15S-1N-80 T membrane. Microcracks developed as the curing temperature was elevated from 60 to 80 °C in 15 wt.% SF28. The microcracks were blocked by wastewater particles, resulting in fouling and decreased wastewater permeability.

For the five membranes shown in Fig. 2, the corresponding permeation decline was calculated by dividing the difference between the final and initial wastewater permeability by the initial wastewater permeability. The decline in the permeation value indicates the impact of membrane fouling on the membrane flux. The membrane GP3-15S-1N-60 T showed the lowest flux decline of 9%, possibly attributed to its smallest diameter values of 327 nm27, which reduced internal pore blockage.

For five membranes, the turbidity reduction was found using Eq. 2 after 2 h of operation (at 1.2 bar, 1 L/min feed flow rate, and 25 °C feed temperature). The geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane of GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T achieved a maximum turbidity reduction of 95.5%. To understand the performance of these five membranes in membrane filtration of real wastewater, the cumulative volume of the permeate for each membrane is measured and reported in Fig. 3.

A linear increase in the cumulative volume was observed for all membranes. The maximum and the minimum values for the cumulative permeate volume were observed for GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T and GP4-15S-0.8N-70 T membranes, respectively. Consequently, the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane that was chosen for its superior performance has a pure water permeability of 144 L/m2hbar, a wastewater permeability of 77 L/m2hbar, a turbidity reduction of 95.5%, and a permeation decline of 44%. The geopolymer-zeolite composite exhibited superior membrane performance due to the geopolymer and zeolite’s concurrent features.

Characterization of the prepared GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane

The membrane GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T was characterized due to its superior performance, but detailed characterizations of other membranes can be found in our previous publications27.

Fig. S2 demonstrates the XRD pattern of MK and the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane. A broad peak in the 2θ range between 20 and 40° can be seen in the precursor metakaolin, which denotes the amorphous phase. This broad peak lies between 20 and 30° in the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane. The transition of the broad peak in the synthesized samples indicates the emergence of a new amorphous phase known as a geopolymer38. During the polycondensation phase of geopolymer production, an amorphous sodium-alumino-silicate-hydrated (N-A-S–H) was produced. Therefore, the shift of the broad peak in the XRD pattern of the synthesized GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane is due to the formation of a new amorphous phase of N-A-S–H39.

Additionally, the XRD analysis of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane demonstrated zeolite A (Card No. 01–083-2151) and amorphous phases, which are named a geopolymer-zeolite composite. The zeolite phase was formed rather than an amorphous geopolymer when the molar ratio of SiO2/Al2O3 < 3 and Na2O/Al2O3 ≥ 1. Under this condition, Na+ ions were more likely to participate closely in the zeolite charge-balancing process when SiO4 and AlO4 were linked40. Therefore, the synthesized sample tends to form zeolite rather than amorphous phases. Wan et al.41 prepared a geopolymer from MK as an aluminosilicate precursor and SF in alkali activator as a silica corrector and found through the XRD analysis that zeolite A has been formed at a SiO2/Al2O3 = 2 and Na2O/Al2O3 = 1. An incomplete calcination of the kaolin is represented by the K phase in the XRD pattern with card numbers 78–211042. It should be noted that the quartz impurity in the MK precursor with card number 065–0466 does not participate in geopolymerization reactions, so the peak associated with the quartz phase can also be observed in the XRD pattern of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane43.

Based on Fig. S2, the intensity of the peaks related to quartz in the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane was lower than that of metakaolin, which can be explained by quartz’ low solubility in sodium hydroxide. The crystallization intensity in XRD patterns decreased as some quartz dissolved in sodium hydroxide, resulting in geopolymerization reactions on the quartz sample44.

The FTIR spectra of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane and MK as a precursor are depicted in Fig. S3. It can be observed in the MK spectrum that the 480 and 800 cm-1 bands are related to the T-O bending vibration tetrahedral TO4 (T = Al or Si tetrahedral) and Al-O in octahedral AlO6, respectively45. A broken structure of metakaolin occurs during geopolymerization in the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane, resulting in the decreased intensity of both bands, especially the 800 cm-1 band45. The absorption band in GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane at around 724 cm-1 is related to the symmetric and asymmetric vibration of Si–O-Al and Si–O-Si, which creates a connection between AlO4 and SiO4 in the geopolymer structure46. The broadband at 850–1350 cm-1 indicates the symmetric stretching vibration of Si–O-T (T = Si or Al) in the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane sample after polycondensation or geopolymerization. Additionally, GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane shows absorption bands at 850–1350 and 2900–3800 cm-1, indicating aluminosilicate gel formation46. The band at 560 cm-1, corresponding to the exterior connecting vibrations of the TO4 (T = Al or Si) tetrahedra in the double rings of zeolite A, occurred in the synthesized sample and was verified by the XRD results47.

In the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane, the absorption band at 1440 cm-1 is associated with the O-C-O asymmetric stretch mode, which is not observed in the MK spectrum48. The change in the position of the asymmetric Si–O-T stretching band in metakaolin from 1092 to 1000 cm-1 indicates the formation of geopolymer or zeolite in the synthesized sample48. Hydroxyl stretching vibrations and H-OH bonds are observed at 1651 and 3440 cm-1, which are related to hydroxyl (OH-) and water adsorbed in the gel49.

Fig. S4 displays the synthesized GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane’s pore size and volume distribution curves measured by MIP. According to the results of this study, the average pore diameter, porosity percentage, total cumulative volume, and specific surface area of this membrane are 400.07 nm, 34.12%, 265.62 mm3/g, and 13.84 m2/g, respectively, which are located in the MF range. The pore size is in the mesopore range when metakaolin-based geopolymer is activated by sodium silicate50. A self-supporting membrane with silicate sodium and a H2O/ Na2O molar ratio of 18 had a 60 nm average pore size51. According to Nmiri. et al.52 and Oshani. et al.28, the average pore size of metakaolin-based geopolymer with silica fume instead of silicate sodium was 220 nm (6 wt.% SF) and 327 nm (15 wt.% SF), respectively. This paper demonstrated that forming zeolite in the geopolymer matrix resulted in a bigger size (400 nm) than the geopolymer structure alone.

Fig. S5 shows the SEM images of the cross-section of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane. Particles with a cubic shape, marked by arrows, are uniformly and regularly distributed on the surface of geopolymers. A cubic structure of zeolite A was observed in SEM in the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane. The cubic structure matched zeolite A, as the EDS analysis indicated in our previous study28.

The FTIR and XRD (Fig. S2 and Fig. S3) investigations validate that the integration of zeolite A into the geopolymer matrix alters the chemical structure and enhances the membrane’s microstructure, hence facilitating permeation and optimizing microfiltration performance. The zeolite crystals function as spacers within the geopolymer matrix, interrupting the dense network25 as observed in SEM and creating supplementary transport routes. Turbidity can be decreased by the size-exclusion-based separation process, which retains the suspended particles from real wastewater larger than the membrane pore size.

Result of screening design

This section examined the screening design of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane. The experiment array and the levels of parameters are shown in Table 2. Only two levels were considered for the parameters. There are two wastewater concentration levels (C), one of which is the initial concentration (Co), which has a value of 1, and the other is 0.25 Co, which has a value of 0.25.

The steady permeability of the wastewater was the first design response; however, as the membrane has different permeability under different operating conditions, the dimensionless permeability (steady state wastewater/pure water permeability) was defined and used as the first response (R1), and turbidity reduction as the second response (R2), as shown in Table 2. The R-squared values for R1 and R2 were 0.999 and 0.9995, respectively, which are excellent.

Table 3 displays the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance). results for R1 and R2. The impact of operational parameters (P, Q, T, and C) on membrane performance (two responses) was statistically assessed in this study using ANOVA. The proposed model is significant with 95% confidence since its p-value is less than 0.0553. Also, the p-values of the lack of fit for R1 and R2 were 0.336 and 0.428, respectively, which are above 0.05 and insignificant54.

It is generally assumed that factors and interactions with p-values less than 0.05 are significant, and the lower the p-value, the greater the effect on the responses53. Table 3 shows that feed pressure, temperature, and feed flow rate have a greater impact on the responses than feed concentration. However, their contributions to the final responses, calculated from the SS of each factor divided by the total SS of all parameters, were considerably different.

The results showed that the feed flow rate had the largest impact on the responses, with contributions of 90.03% and 83.12% to R1 and R2, respectively. Feed Pressure (P) and Temperature (T) had statistically significant impacts (p < 0.05); however, their contributions were considerably reduced. The smallest contributions were observed for feed concentration, with the contributions of 0.02% and 0.03% to R1 and R2, respectively. Therefore, the feed concentration factor was nullified in the optimization design (the next design). The lack-of-fit test for both models yielded p-values of 0.336 (R₁) and 0.428 (R₂), signifying no significant lack of fit, hence affirming the models’ adequacy. The interaction PQ (Pressure × Flow Rate) exerted a moderate influence on both responses, with a contribution of about 0.17–0.25%. The three-way interaction P × C × Q exhibited statistical significance (p < 0.005), suggesting possible synergy among the variables within particular operational ranges.

The mean responses for R1 and R2 are shown in Fig. S6. According to the result, R1 was highest at 2 bar, while R2 was highest at 1.2 bar. Due to a higher driving force, higher feed pressure can increase R155. However, the turbidity reduction decreased by increasing pressure, which means a lower separation ability of the membrane at higher pressures. It could be attributed to higher concentration polarization at the membrane surface at higher pressures56. Increasing the feed temperature to 60 °C raises R1 and decreases R2. Temperature rise reduces feed solution viscosity and expands membrane pores, leading to higher permeability and reduced turbidity57. A significant change in R1 was observed with an increase in the feed flow rate. The higher feed flow rates enhance the liquid stream and shear forces on the surface of the membrane, reducing the concentration polarization and limiting the particle deposition and, consequently, cake formation on the membrane surface, enhancing both R1 and R 32.

Pore size and pore size distribution significantly affect MF membranes’ permeability and rejection capabilities58. The GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane is constructed with an average pore size of 400 nm (0.4 µm), which is smaller than the particle size of the solute (as indicated in Table 1). Consequently, this membrane effectively retains solute particles larger than 0.4 µm, demonstrating commendable performance. The feed flow rate is the most effective parameter in R1 and R2, as indicated by the screening design results.

The feed flow rate range is crucial for assessing between 0.5 and 1.75 l/min, compared to other parameters. It appears that R1 and R2 are affected by hydrodynamic conditions rather than feed concentration, rendering the impact of feed concentration negligible.

Optimization of the operating condition

In this section, the membrane performance was modified using CCD for the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane, taking into consideration three parameters: Pressure, Temperature, and feed flow rate, which all have a significant impact on the responses in the screening design. For optimization of the operating condition, 20 runs with six replications were proposed by the CCD design, where the experimental condition, actual measured responses (R1 and R2), and predicted responses are shown in Table 4.

The responses and design matrix were obtained through experimental design for the geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane. The quadratic models fit the experimental data very well, as illustrated by the R-sq values of 0.9984 and 0.9786 for dimensionless permeability and turbidity reduction, respectively. The adjusted R-sq values for these two models are 0.9982 and 0.9687, confirming the quadratic models’ accuracy. R1 (normalized permeability) and R2 (turbidity reduction) are defined as Eqs. 7 and 8.

The ANOVA results, presented in Table 5, were conducted to investigate the influence of feed pressure, feed temperature, and feed flow rate on R1 and R2. The model exhibited great significance (p-value = 0) for R1 and R2. It was concluded that P, T, Q, and Q2 were the most significant model terms for R1; P, T, Q, Q2, P2, and T2 were significant for R2, with p-values less than 0.05. The feed flow rate (Q) was the most influential term, with F = 7902.71 for R1 and F = 448.07 for R2. The p-values for lack of fit were 0.189 and 0.536 for R1 and R2, which were insignificant.

The residual plots for R1 and R2 are shown in Fig. S7. A normal probability plot (Fig. S7a, b) resembles a straight line, demonstrating a normal distribution of residues. Additionally, the residual versus the fit plot (Fig. S7c, d) and the residuals versus the ordered plot (Fig. S7e, f) show that residuals are independent because they are randomly distributed on both sides of the zero line59.

The effects of operating parameters, including pressure, temperature, and feed flow rate, on R1 and R2 are shown in Fig. 4. At a fixed temperature of 42.5 °C (center point), pressure and feed flow rate were investigated on R1 and R2 (Fig. 4a, c). The relationship between feed pressure and flow rate exhibited a curve, indicating that feed pressure and flow rate variations substantially influence R1. R1 increased with feed pressure above 1.6 bars and flow rate above 1.2 l/min, reaching more than 0.85 (Fig. 4 b). On the other hand, R2 comes higher than 96% when the pressure is below 1.5 bar (near minimum), and the flow rate is above 1.4 l/min (Fig. 4d). Maximum feed flow and pressure inhibit concentration polarization and cake formation, increasing R1. However, Increases in these two values simultaneously decreased separation ability and turbidity reduction (R2).

The 3D response surface plots and the 2D contour plots for (a, b) an interaction between feed pressure and feed flow rate for R1, (c, d) an interaction between pressure and feed flow rate for R2, (e, f) an interaction between pressure and temperature for R1, (g, h) an interaction between pressure and temperature for R2, (i, j) an interaction between feed flow rate and temperature for R1, (k, l) an interaction between feed flow rate and temperature for R2.(use color in print).

Pressure and temperature variations had a linear relationship, so a variation in feed pressure and temperature has a smaller impact on R1 in Fig. 4e than a variation in feed pressure and flow rate (Fig. 4a). The maximum R1 was observed at temperatures above 50 °C and pressures above 1.9 bar, as shown in Fig. 4f. In contrast, feed pressure and temperature significantly impacted R2 because their relationship was a curve. As depicted in Fig. S5 h, the temperature and pressure must be at their lowest values for R2 to attain its maximum value (> 94%).

In Fig. 4i, k, R1 was enhanced by elevating the flow rate and temperature values; however, the temperature changes had a low effect on R2. As shown in Fig. 4j, the maximum of R1 (more than 0.6) was observed at the highest feed flow rate (> 1.2 L/min) and highest temperature (> 45 °C). However, the maximum of R2 (94–96%) was exhibited at all temperatures and highest feed flow rates (about 1.4 -16 L/min); therefore, temperature variations have little effect on R2 (Fig. 4l).

For R1, the optimum operating conditions that offer minimum fouling effects are P = 2 bar, T = 59.6 °C, and Q = 1.73 L/min. Under these optimum conditions, the dimensionless permeability = 0.74, and the turbidity reduction was 90.40. The optimum operating condition for attaining the highest turbidity reduction is P = 1.2 bar, T = 25.3 °C, Q = 1.73 L/min, which results in nearly 100% turbidity reduction and dimensionless permeability = 0.33 Optimizing the MF process to simultaneously maximize steady-state wastewater permeability /pure water permeability and turbidity reduction results in dimensionless permeability = 0.57 and turbidity reduction of 97.87% with desirability equal to 1.00, which was found as 1.2 bar as feed pressure, 59.6 °C as feed temperature, and 1.73 L/min as feed flow rate.

The membrane filtration was performed at the predicted condition using the real wastewater to validate the model’s predicted optimum conditions, and the responses R1 and R2 were determined. The experimental R1 and R2 were measured as 0.58 and 96.2%, respectively, which showed an error of 1.75% and 1.7% for R1 and R2, respectively, revealing excellent agreement with the model-predicted values.

Fouling study

This section examined the membrane resistance of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60T membrane under the optimal operating conditions of the CCD. The particular contribution of membrane resistance is provided in Table 6. The results revealed that more than 57% of the total resistance was attributed to membrane resistance (Rm), followed by cake formation (26.5%) and reversible pore blockage (15.03%). The reversible pore-blocking resistance, mainly due to the adsorption of particles on the pore wall, contributed to only 1.43% of the total resistance, which is negligible.

These results corroborate the findings reported in a previous study by Moravia et al.60 and Pertile et al.61 on the fouling of MF, indicating that Rm had the largest resistance, more than 50% of Rt. It is natural for the ceramic and geopolymer membranes because they are very thick (in the order of several millimeters) compared to the polymeric membranes, which are very thin (in the order of a few hundred micrometers). The large RC and Rr show that the feed wastewater contained solid particles larger than the membrane’s pore diameter, and they formed a cake layer on the membrane surface or blocked the pore’s entrance. However, they could be reduced by the increase in the feed crossflow velocity, as explained before60. Elevated feed pressures may raise Rc and Rr by forcing solutes and solid particles to gather on the membrane surface, forming a denser cake layer.

These agree with the optimization results, in which low feed pressure and high feed flow rate have been introduced as the optimum operating parameters.

An ideal membrane for application in the industry should have high permeability, low flux decline, low fouling tendency, high solute rejection, and high flux recovery32. In this regard, cyclic filtration and the regeneration of the fouled membrane operations were investigated using a geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane as the optimum membrane and under optimum operating conditions obtained in the previous step, and real wastewater as the feed. Table 7 presents the results of the steady-state wastewater permeability and the resistance values for four 1h cyclic runs. The results showed negligible permeability decline (2.66%) and turbidity reduction after four cycles, so it could be considered constant. Either steady-state wastewater permeability or the resistances remained nearly unchanged, and it could be concluded that backwashing is completely effective in permeability recovery, which is very common in commercial inorganic membranes practice.

To find a model for fouling the geopolymer membrane, four fouling models (Hermia models) were examined. The results of fitting the models with the experimental data, taken by an optimum membrane at optimum operating conditions, are presented in Fig. 5. The results of the regression of the models show that the cake filtration model is the most suitable model for estimating the filtration of real wastewater permeate flux. The cake filtration model had the highest predictive capability for flux drop in the microfiltration of oil-in-water emulsions utilizing ceramic membranes, corroborated by similar findings from Vasanth et al.62.

Examination of the Hermia models for the microfiltration of textile wastewater at a pressure of 1.2 bar, a temperature of 59.6 °C, and a feed rate of 1.73L/min, (a) the Complete Blocking Model (CBM), (b) the Intermediate Blocking Model (IBM), (c) the Standard Blocking Model (SBM), and (d) the Cake Formation Model (CFM).

Figures 6 and 7 show SEM images and elemental analysis of the clean, fouled (cake-contained), surface cleaned (cake-removed), and backwashed membrane surfaces. Figure 6a shows the clean surface of the membrane, which is porous. The elemental analysis (Fig. 7a) reveals a uniform distribution of Si, Al, Na, O, and a minor amount of C from silica fume impurity. The EDS line scan of the cleaned produced geopolymer membrane (Fig. S8) indicated the C was less than 10wt.%.

Figure 6b shows a fouled membrane after microfiltration of textile wastewater. This image reveals that a thick layer of suspended particles has been applied to the membrane surface. It could be observed that the porosity of the cake layer was significantly lower than that of the clean membrane. According to Fig. 7b, the layer contains much more carbon material than the clean membrane because of the organic compounds of the dyes. Fig. S8 shows an increase in C content of the membrane surface with the cake layer due to organic particle deposition.

The membrane surface was examined by removing the cake with soft tissue fabric, and some pores were found to be opened, confirming pore-blocking during filtration (Fig. 6c). Carbon tracking on the membrane surface (Fig. 7c) shows a smaller C content than Fig. 7b. In Fig. S8, the EDS line of the surface membrane after removing the cake layer shows a lower C content than the surface membrane with the cake layer; however, it was still more than 10 wt.%, which indicates some pores are still blocked.

Following the backwashing with distilled water, the membrane surface became clean, and nearly all blocked pores were opened. No significant pore-blocking on the cleaned membrane confirms the effectiveness of backwashing (Fig. 6d). Based on Fig. S8, the C content of the membrane surface after backwashing was the lowest among all samples (less than 5 wt.%), nearly equal to the pristine membrane. Hence, the applied strategy for the regeneration of the fouled membrane was able to regenerate the membrane completely.

Table 8 illustrates the features of geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes with ceramic and geopolymer membranes for treating industrial textile wastewater. The performance of ceramic membranes with two layers is greater; however, the fabrication of geopolymer membranes is simpler and needs no calcination. The majority of the geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes that have been published are for nanofiltration. However, in this study, MF was prepared without hydrothermal methods and with changes in the preparation parameters. Zeolite in the geopolymer matrix has the potential to alter the microstructure of the membrane, thereby enhancing its performance.

Cost analysis

Table 9 displays the cost of raw materials used in the fabrication of the GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T membrane, which is then compared to the kaolin ceramic membrane to facilitate a more accurate cost comparison. Kaolin-based ceramic membranes are typically priced at $150 to $300 per m2 ref2,66. The primary reason for this high cost is the extensive energy requirements for sintering, which usually happens at temperatures between 1000 and 1200 °C67. Additionally, the necessity of specialized equipment, including extruders, cast shaping systems, and high-temperature calcination furnaces, contributes to the cost51.

On the other hand, the geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane (GPZ2-10S-1N-60 T) that was developed in this study is fabricated at temperatures that do not exceed 60 °C and requires no sintering, extrusion, or molding equipment, or other costly high-temperature processing facilities69. The cost advantage of geopolymer-based membranes is substantial as a consequence of this distinction. The total estimated production cost for the geopolymer-zeolite membranes is approximately $50 to $70 per m2, accounting for both raw materials and processing costs. The fabrication costs of geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes can be reduced by a minimum of 60 to 80 percent when compared to conventional ceramic membranes.

The geopolymer synthesis process, which employs basic, low-energy apparatus such as mixers, molds, and curing chambers, is highly adaptable to large-scale production in terms of scalability. This process involves alkali activation followed by mild curing. The procedure is especially appropriate for use in wastewater treatment equipment, as it does not necessitate modern facilities. Additionally, the membrane regeneration process, which is entirely dependent on easy backwashing techniques, as illustrated in Table 7 and Section "Optimization of the operating condition", offers effective long-term reuse and significantly reduces operational expenses in practical applications.

Conclusion

The development of a cost-effective and sustainable geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane for textile wastewater microfiltration is demonstrated in this research, which offers significant value-added contributions. This membrane requires no hydrothermal treatment or high-temperature sintering. The fabricated membrane maintains outstanding turbidity reduction (> 96%) and fouling resistance through simple backwashing, exhibits high permeability (165 L/ m2h.bar), and is constructed using low-cost metakaolin and silica fume.

A full factorial screening design was examined on the geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane for the effect of operating variables such as applied pressure, feed temperature, wastewater concentration, and feed flow rate on the normalized permeability and turbidity reduction. The results showed that the feed concentration (in the considered range) had little effect on the responses, so it was deleted from the list of effective parameters for optimization. According to the CCD-RSM design, the optimal conditions for achieving normalized permeability = 0.57 and turbidity reduction = 97.87% were 1.2 bar of feed pressure, 59.6 °C of feed temperature, and 1.73 L/min of feed flow rate, with a desirability. The resistance-in-series model revealed that the primary fouling mechanism was cake formation, and Hermia model fitting confirmed cake layer deposition as the dominant flux decline mechanism. Backwashing proved highly effective, recovering more than 97% of the initial flux over four cycles. The membrane’s potential as a viable pretreatment option for industrial wastewater reuse has been demonstrated by its consistent performance, low cost, and sustainable fabrication process. This is especially applicable in textile applications, where NF membranes necessitate low turbidity input.

Data availability

Data will be available upon request by the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- C:

-

Wastewater concentration (a.u.)

- jo :

-

Initial permeate flow values in Eq. (6) (units depend on the fouling mechanism)

- Jv :

-

Volumetric permeate flux (m3/m2. S)

- K:

-

Constant in Eq. (6) (units depend on the parameter n in Eq. (6))

- nL:

-

Constant in Eq. (5) (units depend on the fouling mechanism)

- P:

-

Feed pressure (Pa)

- Q:

-

Feed flow rate (L/min)

- R2 :

-

Regression coefficient

- Rc :

-

Cake layer resistance (m-1)

- Rir :

-

Irreversible membrane resistance (m-1)

- Rm :

-

Membrane resistance (m-1)

- Rr :

-

Reversible membrane resistance (m-1)

- Rt :

-

Total resistance (m-1)

- Rτ :

-

Turbidity reduction

- S:

-

Filtrate surface area (m2)

- T:

-

Filtration time (s)

- T:

-

Curing temperature (°C)

- Tf :

-

Feed temperature (°C)

- Tfeed :

-

Turbidity of feed

- Tpermeate :

-

Turbidity of permeate

- V:

-

Permeate volume (m3)

- ρ:

-

Permeate density (kg/m3)

- µ:

-

Permeate viscosity (pure water: 0.001 Pa.s; permeate: 0.00114 Pa.s)

- CCD:

-

Central composite design

- MF:

-

Microfiltration

- MK:

-

Metakaolin

- NF:

-

Nanofiltration

- RO:

-

Reverse osmosis

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- R-sq:

-

R-squared

- R-sq (adj):

-

Adjusted R-squared

- R-sq (pred):

-

Predicted R-squared

- SF:

-

Silica fume

- UF:

-

Ultrafiltration

References

Voulvoulis, N. Water reuse from a circular economy perspective and potential risks from an unregulated approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2, 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2018.03.005 (2018).

Lu, W. & Leung, A. Y. T. A preliminary study on potential of developing shower/laundry wastewater reclamation and reuse system. Chemosphere 52, 1451–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00491-0 (2003).

Tang, C. Y. et al. Potable water reuse through advanced membrane technology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10215–10223. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b00562 (2018).

Wu, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Zheng, X. & Chen, Y. Municipal wastewater reclamation and reuse using membrane-based technologies: A review. Desalin. Water Treat. 224, 65–82. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2021.26929 (2021).

Isawi, H. Synthesis of graphene oxide–silver (GO–Ag) nanocomposite TFC RO membrane to enhance morphology and separation performances for groundwater desalination (case study Marsa Alam area – Red Sea). Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 187, 109343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2023.109343 (2023).

Ebrahimi, M., Kujawski, W. & Fatyeyeva, K. Fabrication of polyamide-6 membranes—The effect of gelation time towards their morphological, physical, and transport properties. Membranes 12, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12040315 (2022).

Isawi, H. Evaluating the performance of different nano-enhanced ultrafiltration membranes for the removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 31, 100833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100833 (2019).

Isawi, H. Using zero-valent iron/thin film composite (ZNVI/TFC) membrane for brackish water desalination and purification. Surfaces Interfaces 54, 105237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.105237 (2024).

Świerczek, K., Kołodziej, Z. & Jaworska, K. Comparison of polymeric and ceramic membranes performance in the process of micellar enhanced ultrafiltration of cadmium(II) ions from aqueous solutions. Chem. Pap. 67, 380–388. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11696-012-0266-9 (2013).

Saini, P., Bulasara, V. K. & Reddy, A. S. Performance of a new ceramic microfiltration membrane based on kaolin in textile industry wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. Commun. 206, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2018.1434305 (2019).

Bhattacharya, P. et al. Combination technology of ceramic microfiltration and reverse osmosis for tannery wastewater recovery. Water Resour. Ind. 3, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wri.2013.06.002 (2013).

Barredo-Damas, S., Alcaina-Miranda, M. I., Iborra-Clar, M. I. & Mendoza-Roca, J. A. Application of tubular ceramic ultrafiltration membranes for the treatment of integrated textile wastewaters. Chem. Eng. J. 192, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.03.056 (2012).

Van der Bruggen, B., Mänttäri, M. & Nyström, M. Drawbacks of applying nanofiltration and how to avoid them: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 63, 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2008.05.010 (2008).

Xiao, T. et al. Membrane fouling and cleaning strategies in microfiltration/ultrafiltration and dynamic membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 318, 123977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.123977 (2023).

Cai, C., Sun, W., He, S., Zhang, Y. & Wang, X. Ceramic membrane fouling mechanisms and control for water treatment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-022-1573-5 (2023).

Escobar, I. C. & Van Der Bruggen, B. Fouling control on microfiltration/ultrafiltration membranes: Effects of morphology, hydrophilicity, and charge. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132, 42168. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.42168 (2015).

Jankowska, K. et al. Effect of backwash as a strategy for biofouling control in the submerged ceramic membrane bioreactor for high-density cultivations: Process optimization and fouling mechanism at pilot scale. Sep. Purif. Technol. 338, 124882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.124882 (2024).

Mehrabian, M. & Kargari, A. Bio-based nonporous membranes: Evolution and benchmarking review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2023.04.018 (2023).

Karimi, Z. & Rahbar-Kelishami, A. Preparation of highly efficient and eco-friendly alumina magnetic hybrid nanosorbent from red mud: Excellent adsorption capacity towards nitrate. J. Mol. Liq. 368, 120751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120751 (2022).

Karimi, Z. & Rahbar-Kelishami, A. Efficient utilization of red mud waste via stepwise leaching to obtain α-hematite and mesoporous γ-alumina. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35813-0 (2023).

Isawi, H. Using zeolite/polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate nanocomposite beads for removal of some heavy metals from wastewater. Arab. J. Chem. 13, 5691–5716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.06.003 (2020).

Ge, Y., Yuan, Y., Wang, K., He, Y. & Cui, X. Preparation of geopolymer-based inorganic membrane for removing Ni2⁺ from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 299, 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.08.021 (2015).

Matsimbe, J., Olukanni, D., Dinka, M. & Musonda, I. Geopolymer: A systematic review of methodologies. Materials (Basel) 15, 6852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15196852 (2022).

He, P. Y., Zhang, Y. J., Chen, H., Han, Z. C. & Liu, L. C. Low-cost and facile synthesis of geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane for chromium(VI) separation from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 392, 122359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122359 (2020).

Shao, N., Tang, S., Li, S., Chen, H. & Zhang, Z. Defective analcime/geopolymer composite membrane derived from fly ash for ultrafast and highly efficient filtration of organic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 388, 121736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121736 (2020).

Zhang, Y. J., Chen, H., He, P. Y. & Li, C. J. Developing silica fume-based self-supported ECR-1 zeolite membrane for seawater desalination. Mater. Lett. 236, 538–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2018.10.062 (2019).

Oshani, F., Kargari, A., Norouzbeigi, R. & Mahmoodi, N. M. Role of fabrication parameters on microstructure and permeability of geopolymer microfilters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 210, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2023.11.010 (2024).

Oshani, F., Allahverdi, A., Kargari, A., Norouzbeigi, R. & Mahmoodi, N. M. Effect of preparation parameters on properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer activated by silica fume-sodium hydroxide alkaline blend. J. Build. Eng. 60, 104984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104984 (2022).

Manni, A. et al. New low-cost ceramic microfiltration membrane made from natural magnesite for industrial wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 103906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103906 (2020).

Beqqour, D. et al. Enhancement of microfiltration performances of pozzolan membrane by incorporation of micronized phosphate and its application for industrial wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 102981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.102981 (2019).

Mulder, M. Basic Principles of Membrane Technology (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996).

Manouchehri, M. & Kargari, A. Water recovery from laundry wastewater by the cross-flow microfiltration process: A strategy for water recycling in residential buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 168, 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.032 (2017).

Quezada, C., Estay, H., Cassano, A., Troncoso, E. & Ruby-Figueroa, R. Prediction of permeate flux in ultrafiltration processes: A review of modeling approaches. Membranes (Basel) 11, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11030208 (2021).

Antony, J. Screening designs. In Design of Experiments for Engineers and Scientists (ed. Antony, J.) (Elsevier, 2014).

Montgomery, D. C. & Jennings, C. L. An overview of industrial screening experiments. In Screening: Methods for Experimentation in Industry, Drug Discovery, and Genetics (eds Montgomery, D. C. & Jennings, C. L.) (Springer, 2006).

Ghalami Choobar, B., Alaei Shahmirzadi, M. A., Kargari, A. & Manouchehri, M. Fouling mechanism identification and analysis in microfiltration of laundry wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 102935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.102935 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer utilizing waste completely decomposed granite. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e01739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e01739 (2023).

Jurado-Contreras, S., Bonet-Martínez, E., Sánchez-Soto, P. J., Gencel, O. & Eliche-Quesada, D. Synthesis and characterization of alkali-activated materials containing biomass fly ash and metakaolin: Effect of the soluble salt content of the residue. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 22, 121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-022-00421-2 (2022).

Walkley, B., Ke, X., Husseina, O. & Provis, J. L. Thermodynamic properties of sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N–A–S–H). Dalton Trans. 50, 13968–13984. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1DT01976A (2021).

Juengsuwattananon, K., Winnefeld, F., Chindaprasirt, P. & Pimraksa, K. Correlation between initial SiO₂/Al₂O₃, Na₂O/Al₂O₃, Na₂O/SiO₂ and H₂O/Na₂O ratios on phase and microstructure of reaction products of metakaolin–rice husk ash geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 226, 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.259 (2019).

Wan, Q. et al. Geopolymerization reaction, microstructure, and simulation of metakaolin-based geopolymers at extended Si/Al ratios. Cem. Concr. Compos. 79, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.01.014 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Quantitative kinetic and structural analysis of geopolymers. Part 1: The activation of metakaolin with sodium hydroxide. Thermochim. Acta 539, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2012.03.021 (2012).

Cao, R., Fang, Z., Zheng, F., Jin, M. & Shang, Y. Study on the activity of metakaolin produced by traditional rotary kiln in China. Minerals 12, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12050636 (2022).

Nenadović, S. et al. Structural, mechanical, and chemical properties of low-content carbon geopolymer. Sustainability 14, 4885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094885 (2022).

Poggetto, G. D. et al. FT-IR study, thermal analysis, and evaluation of the antibacterial activity of an MK-geopolymer mortar using glass waste as fine aggregate. Polymers (Basel) 13, 2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172970 (2021).

Mohamed, H. et al. Mechanical and microstructural properties of geopolymer mortars from meta-halloysite: Effect of titanium dioxide TiO₂ (anatase and rutile) content. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03329-8 (2020).

Krol, M., Minkiewicz, J. & Mozgawa, W. IR spectroscopy studies of zeolites in geopolymeric materials derived from kaolinite. J. Mol. Struct. 1126, 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.07.078 (2016).

Anove, K. M. et al. Physico-chemical and mineralogical characterizations of two Togolese clays for geopolymer synthesis. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 10, 331–349. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmmce.2022.104020 (2022).

Li, J., Yang, L., Rao, F. & Tian, X. Gel evolution of copper tailing-based green geopolymers in marine-related environments. Materials (Basel) 15, 4589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15134589 (2022).

Okada, K. et al. Water retention properties of porous geopolymers for use in cooling applications. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 29, 1917–1923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2008.10.009 (2009).

Xu, M. et al. Preparation and characterization of a self-supporting inorganic membrane based on metakaolin-based geopolymers. Appl. Clay Sci. 115, 254–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2015.08.015 (2015).

Nmiri, A., Duc, M., Hamdi, N., Yazoghli-Marzouk, O. & Srasra, E. Replacement of alkali silicate solution with silica fume in metakaolin-based geopolymers. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 26, 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-019-1794-7 (2019).

Tohidian, E., Zokaee Ashtiani, F. & Kargari, A. Optimization of the condition for the fabrication of a two-layer integrated skin polyetherimide nanofiltration membrane. J. Water Process Eng. 34, 101176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.101176 (2020).

Sadeghian, M., Sadeghi, M., Hesampour, M. & Moheb, A. Application of response surface methodology (RSM) to optimize operating conditions during ultrafiltration of oil-in-water emulsion. Desalin. Water Treat. 55, 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.922561 (2015).

Hassani, H. A. et al. Nanofiltration process on dye removal from simulated textile wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 5, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03326037 (2008).

Arzani, M., Mahdavi, H. R., Azizi, S. & Mohammadi, T. Performance evaluation of mullite ceramic membrane for oily wastewater treatment using response surface methodology based on Box-Behnken design.. J. Oil Gas Petrochem. Technol. 5, 25–40 (2018).

Khan, F. et al. Optimal clarification of apple juice using crossflow microfiltration without enzymatic pre-treatment under different operation modes. NUST J. Eng. Sci. 9, 18–22 (2016).

Siddiqui, M. U., Arif, A. F. & Bashmal, S. Permeability-selectivity analysis of microfiltration and ultrafiltration membranes: Effect of pore size and shape distribution and membrane stretching. Membranes 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes6010007 (2016).

Salar-García, M. J., de Ramón-Fernández, A., Ortiz-Martínez, V. M., Ruiz-Fernández, D. & Ieropoulos, I. Towards the optimisation of ceramic-based microbial fuel cells: A three-factor three-level response surface analysis design. Biochem. Eng. J. 144, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2019.01.011 (2019).

Moravia, W. G., Amaral, M. C. S. & Lange, L. C. Evaluation of landfill leachate treatment by advanced oxidative process by Fenton’s reagent combined with membrane separation system. Waste Manag. 33, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.08.016 (2013).

Pertile, C., Zanini, M., Baldasso, C., Andrade, M. Z. & Tessaro, I. C. Evaluation of membrane microfiltration fouling in landfill leachate treatment. Mater. Res. 21, e20170915. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2017-0915 (2018).

Vasanth, D., Pugazhenthi, G. & Uppaluri, R. Cross-flow microfiltration of oil-in-water emulsions using low-cost ceramic membranes. Desalination 320, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2013.03.016 (2013).

Jedidi, I. et al. Elaboration of new ceramic microfiltration membranes from mineral coal fly ash applied to wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 172, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.06.144 (2009).

Elomari, H. et al. Elaboration and characterization of flat membrane supports from Moroccan clays: Application for the treatment of wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 56, 3994–4002. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.980333 (2015).

Belgada, A. et al. Optimization of phosphate/kaolinite microfiltration membrane using Box-Behnken design for treatment of industrial wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 104972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.104972 (2021).

Mohammadi, T. & Pak, A. Effect of calcination temperature of kaolin as a support for zeolite membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 30, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5866(02)00177-1 (2003).

Hubadillah, S. K. et al. Fabrications and applications of low-cost ceramic membrane from kaolin: A comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 44, 4538–4560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.11.211 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.O. wrote the Original Draft of the manuscript text and prepared all figures and tables. A.K. supervised, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. R.N. reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.M.M. investigated and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oshani, F., Kargari, A., Norouzbeigi, R. et al. Performance optimization and fouling study of geopolymer-zeolite composite membranes for sustainable textile wastewater treatment. Sci Rep 15, 35463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19349-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19349-0