Abstract

This study was conducted on forty-six wood apple (Feronia limonia) accessions planted in a randomized block design to evaluate the genetic diversity, quality traits, antioxidant properties, and nutrient composition. Numerous parameters, such as fruit weight (FW), seed number per fruit (SNF), total soluble solids in pulp of fruit (TSSP), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and yield per plant (YP), showed significant heterogeneity in the analysis, suggesting that these qualities could be improved genetically. Both stable and highly variable qualities across accessions were reflected in the coefficient of variation, which varied from 1.94% for root attributes to 132.07% for iron (Fe). To evaluate the possibility of selection in breeding programs, genetic parameters such as genetic and phenotypic coefficients of variation (GCV and PCV), heritability, and genetic advancement were computed. Traits such as FW and SNF exhibited high GCV and heritability, suggesting they are highly heritable and suitable for selection. On the other hand, characteristics such as calcium (Ca) demonstrated low heritability, underscoring the impact of environmental influences. Significant positive and negative correlations were found between several traits using correlation analysis. Fruit length (FL) had strong positive correlations with fruit weight (FW), fruit breadth (FB), and pulp weight (Pu), while iron content (Fe) had negative correlations with many other traits. Seven main components were found using principal component analysis (PCA), and PC1 accounted for 22.74% of the variance, which is a considerable amount of the total variation. Based on genetic diversity, a cluster analysis employing Tocher’s approach divided the accessions into discrete clusters. Cluster 2 had the highest mean values for FW, FL, and YP, indicating that it may be highly productive. The interactions between the variables were further elucidated by the genotypic path analysis, which demonstrated that yield potential was significantly influenced by indirect effects, especially through traits like FB, DSW, and Mg. These findings point out the critical role of precise trait selection in perennial crops, where long breeding cycles demand careful identification and prioritization of yield-associated traits. Emphasizing selection over broader breeding approaches ensures the retention and enhancement of traits that contribute most directly to long-term productivity and crop improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wood apple (Feronia limonia) is a native fruit plant of India that is a member of the Rutaceae family. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, China, Africa, and Southeast Asia are among the tropical and subtropical locations where it is extensively found1. It goes by several regional names in India, including Kavath, Kaith, Kotha, and Kabeet2. The wood apple is a hardy plant that grows naturally in the western Himalayas up to an elevation of roughly 500–600 m. The species is primarily distributed across the semi-arid zones and rain-fed regions of India, with major occurrences in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. All parts of the plant are of economic importance, with fruits used in food and beverage manufacturing, and leaves, bark, stem, and roots employed for various medicinal purposes. Fruit ripens between early October to March3. The plant is known for its adaptability to harsh climatic conditions, thriving in areas with a monsoon climate and distinct dry seasons4.

Among the many benefits of wood apple are its uses in beverages, processed foods (such as murabba, preserves, and chutneys). It has been prized for its digestive, carminative, and anti-diarrheal qualities in Ayurvedic and traditional medicine5. Furthermore, the plant includes bioactive substances that are thought to have medicinal properties, including triterpenoids, alkaloids, phenols, and flavonoids6,7,8,9. Despite its high utility, wood apple remains underutilized commercially in hot semi-arid regions of India and worldwide (Bangladesh, Pakistan, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand ad north eastern Africa). Its resilience and soil reclamation potential position it as a promising crop for future horticultural development in challenging environments10 and can guide varietal improvement, enhance productivity, and promote the adoption of wood apple as a viable commercial crop in resource-limited environments for small and marginal farmers. Fruit pulp contents ranging from 40.4 to 60.6%, sugar contents ranging from 3.26 to 14.3%, and ascorbic acid levels ranging from 2.7 to 20.45 mg, wood apple fruits offer a pleasing sweet-acidic flavor11,12. Wood apples have a lot of potential to improve fruit production and the creation of value-added goods because of their versatility, nutritional advantages, and therapeutic qualities.

For upcoming crop improvement initiatives, it is crucial to characterize the genetic diversity and phenotypic variability in minor fruit crops. Traditional breeding techniques have produced superior variants of many fruit species, providing a solid basis for boosting horticultural production around the world3,11. Its hardy perennial nature and ease of propagation through grafting and budding make wood apple a promising commercial crop for hot semi-arid regions, offering income-generation opportunities for small and marginal farmers.

The nutritional and quality traits evaluated in this study demonstrated the substantial importance for both consumer acceptance and market value of wood apple. Attributes like total soluble solids, acidity, pulp percentage, sugar content and ascorbic acid concentration directly influence flavor, processing suitability, and nutritional benefits. High pulp yield and desirable flavor profiles enhance the potential for value-added products like chutney, fruit juice and pickles while elevated ascorbic acid and other micronutrients contribute to the crop’s functional food potential and enrich antioxidant profile of fruit. By identifying genotypes with superior quality and nutritional profiles, the study provides a foundation for developing cultivars that meet both market preferences and dietary needs, thereby supporting commercialization and promoting wider adoption of wood apple in semi-arid regions.

Although the crop has substantial nutritional and therapeutic potential, it has not yet been thoroughly investigated or exploited for large-scale production. The majority of wood apple plants are seedlings, which provide an excellent opportunity to choose elite genotypes with outstanding fruit quality and yield potential. The purpose of this study is to assess superior genotypes for adaptation, value-added goods, and quality yield production in Western India’s rainfed environment. In addition to assessing the qualitative characteristics of fruits and derived products, it is essential to disseminate this knowledge to farmers and promote the commercial cultivation of superior genotypes under problematic soil conditions. Such efforts would facilitate the wider adoption of wood apple in semi-arid regions, thereby enhancing local economies and improving agricultural productivity.

Materials and methods

Study sites and experimental materials

The research was conducted during 2022–2024 at the experimental wood apple Germplasm Block of the Central Horticultural Experiment Station in Godhra, Gujarat, India (Fig. 1), situated at a latitude of 22.692948°N, longitude of 73.536038° E, and an elevation of 113.12 m above sea level. The various Wood Apple genotypes were created via in situ grafting and were subsequently planted at a 10 × 5 m spacing.

Five plants were used to represent each genotype and these plant developed by used scion of marked mother plant maintained in mother block at the station, with each plant functioning as a replicate. The planting layout conformed to a randomized block pattern. The ages of the trees within the orchard ranged from 13 to 14 years. The minimal descriptors for the Wood Apple germplasm, used for development, consist of 46 genotypes. Genetic profiles were gathered from regions of high biodiversity through surveys and from research institutions in different agroecological zones across the country. The collection sites were visited on two occasions during the flowering stage and again during the ripening phase to assess the morphological and qualitative attributes of the fruits. Shoots from scion trees exhibiting the desired characteristics were harvested in March and April, then grafted in situ at the experimental field of the Station.

The key characteristics used for identifying genotypes involved attributes are presented in supplementary Table 1. The important traits analyzed in the study included fruit length, fruit width, fruit weight, rind thickness, seeds per fruit, fresh seed weight per fruit, dry seed weight per fruit, pulp percentage, reducing sugars, total sugars, total soluble solids (TSS) in the pulp, TSS in the peel, acidity in the pulp, acidity in the peel, vitamin C content in the pulp, vitamin C content in the peel, mineral nutrient composition, protein content in the pulp, seed protein, leaf protein, and yield.

The various genotypes were evaluated under the agricultural climate conditions of a semi-arid region with average annual rainfall of around 750 mm, and maximum temperature fluctuations spanning from 33 °C to 47 °C in the summer to 8–23 °C in the winter. The experimental site had soil consisting of shallow black cotton-to-clay loam, with 143.60 kg/ha of available nitrogen, 7.20 kg/ha of phosphorus, and 144.21 kg/ha of potassium present in the 0–22 cm soil depth. The soil had a pH of 7.20, EC value of 0.39 dS/m, bulk density of 1.32 g/cc, hydraulic conductivity of 0.38 cm/h, and organic carbon content of 0.41%. Throughout the experimentation, each tree was subjected to a consistent application of 40 kg of farmyard manure, 1.00 kg of nitrogen, 0.75 kg of phosphorus, and 1.00 kg of potash in 2nd week of august month in both year.

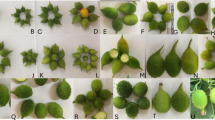

We took photographs of plants or plant parts using a Sony Cyber-Shot digital camera (Japan) from the field repository for creating variability. For various observations, three trees free from pests and diseases were selected to ensure better results. The variability and morphological variation in wood apple germplasm in tree, fruit, leaves, flower, and bark are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and supplementary Table 1. The harvested samples were cleaned with a moist cloth to remove dust and control the field heat. A standard procedure was used for the estimation of tartaric acid (%), reducing sugars (%), non-reducing sugars (%), and total sugars (%), as described in Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC)13.

The dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) procedure was used to measure the ascorbic acid concentration. The value14 was given as mg/100 g fw. Total phenolics were estimated using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent15. To 100 µL of the sample extract (80% ethanol) 2.9 mL of deionized water, 0.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 2.0 mL of 20% Na2CO3 solution were added. The mixture was allowed to stand for 90 min and absorption was measured at 760 nm against a reagent blank in spectrophotometer. Results were expressed as Gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE/100 g fw).

From the digested solution, the plant nutrients including Ca, Mg, and Fewere determined according to the method proposed by Tandon16. Potassium (K) content was estimated by a flame photometer8. The results were expressed in mg/100 g dw.

Statistical analysis

The data and plot analysis were carried out using various packages of Rstudio version 2023.3.0 + 386. The latest available versions of FactoMineR, factoextra, and ggplot2 were used for Principal component analysis17,18. Cluster analysis was carried out with the help of the cluster, factoextra, dendextend, and ggplot2 packages19. The variability analyzed by variability and agricolae and correlation by corrplot20.

These studies sought to better understand genetic diversity, phenotypic relationships, and clustering patterns among the accessions, thus providing data for sensible breeding techniques. First, calculated heritability (ℎ2), genotypic coefficient of variation (GCV), phenotypic coefficient of variation (PCV), genetic advance (GA), and genetic advance as a percentage of mean (GAM). Using the Pandas and NumPy tools, Python constructed these measures to handle and probe the data. The probability of genetic improvement depends on an evaluation of variability; greater values of heritability and GAM indicate features that are fit for selection.

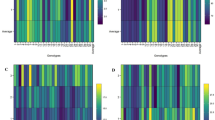

The correlations among these factors were assessed using correlation analysis. Genotypic and phenotypic associations were computed and visualized using heatmaps generated with Python’s seaborn library to reveal trait interdependence, aiding indirect selection in breeding programs. Dimensionality reduction was performed via principal component analysis (PCA) using the scikit-learn suite21,22. Qualitative traits were coded as ordinal categories to integrate with quantitative data, ensuring meaningful contribution to the analysis. Kaiser normalization was applied for scale standardization, and Varimax orthogonal rotation was used to maximize variance in factor loadings, enhancing interpretability. Components with eigenvalues > 1 (Kaiser criterion) were retained23,24. PCA outputs included biplots, 2D score plots, and scree plots, enabling identification of traits contributing most to variance among accessions. Hierarchical clustering, implemented via the SciPy library with seaborn-generated dendrograms and heatmaps, grouped accessions based on trait profiles. Cluster mean analysis and inter- and intra-cluster distances, computed from the D2D^2D2 statistic, quantified genetic diversity and distinguished characteristic features of each group25,26.

Results

The ANOVA results presented in supplementary Table 2 show significant variability in the attributes of forty-six wood apple (Feronia limonia) accessions, with several traits demonstrating highly significant differences.Fruit weight (FW), seed number per fruit (SNF), total soluble solids (TSSP), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and yield per plant (YP) are among the highly significant features (p < 0.01). Significant variation between the accessions is indicated by these attributes’ substantial F-values for both the entries and replications. Fruit length (FL), fruit width (FB), and pulp weight (Pu) are traits that exhibit significant diversity across the accessions and have significant differences at the 5% level. Iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), total solids (TS), and disease resistance (RS) are non-significant features for which no discernible variations were seen among the accessions. Notably, though, substantial variations were discovered at the entry level for iron (Fe) (p < 0.01).The coefficient of variation (C.V.) for the traits varied from 1.94% (RT) to 132.07% (Fe), indicating that some traits have more stable values across the accessions while others show greater variation.

A comprehensive overview of the mean, maximum, minimum, and variance components (genotypic, phenotypic, and environmental variance) for twenty-four attributes of forty-six wood apple (Feronia limonia) accessions is shown in Table 1. The mean values of the qualities vary significantly. For instance, the mean potassium (K) value is 1.59, yet the mean fruit weight (FW) is 244.41 g. Fruit weight (FW) and seed number per fruit (SNF) are two examples of qualities that have very high maximum values (382.92 g and 432.76, respectively), but the minimum values are significantly lower (128.62 g for FW and 192.45 for SNF).

Estimates of environmental (Env. Var.), phenotypic (Pheno. Var.), and genotypic (Geno. Var.) variance are also shown in the Table 1. For example, fruit weight (FW) has a genotypic variance of 2590.57, far larger than its environmental variance of 24.58. This suggests that the variation in fruit weight is mostly due to genetic factors. However, in addition to their genotypic variance, some variables, such as fruit length (FL) and fruit width (FB), also exhibit significant environmental variance, suggesting that environmental factors significantly influence their variation. Low Environmental Variance: Characteristics such as pulp weight (Pu), total soluble solids (TSSPe), and seed number per fruit (SNF) exhibit low environmental variance, suggesting that they are comparatively stable across settings.

Genetic traits

Genetic Coefficient of Variation (GCV), Phenotypic Coefficient of Variation (PCV), Environmental Coefficient of Variation (ECV), Heritability (h2), Genetic Advance (GA), and GA as a percentage of the mean are among the twenty-four genetic parameter estimates for 46 wood apple (Feronialimonia) accessions shown in Table 2. This shows how much genetic variation there is in each attribute. values such as fruit weight (FW, 20.82%) and seed number per fruit (SNF, 17.79%) exhibit significant GCV, indicating substantial genetic variation, but values like iron content (Fe, 86.21%) show an extraordinarily high GCV but may be prone to other complexity. Significant overall variance is also seen in traits with high PCV values, such as fruit weight (FW, 20.92%) and seed number per fruit (SNF, 18.20%).

An estimate of environmental variation is the Environmental Coefficient of Variation (ECV). Low ECV variables, including fruit weight (FW, 2.03%) and seed number (SNF, 3.84%), indicate that environmental influences on these qualities are negligible and that genetic factors play a major role in determining these characteristics. A trait that has a heritability value of 1 (100%) is primarily determined by genetics. For instance, characteristics with high heritability, such as fruit weight (FW, 0.9906) and seed number (SNF, 0.9555), are suitable candidates for breeding selection. On the other hand, calcium (Ca, 0.2699) exhibits low heredity, indicating that environmental variables have a significant impact on its expression.

The anticipated improvement in the trait brought about by selection is known as the genetic progress. Fruit weight (FW, 104.36) and seed number (SNF, 108.39) are two traits that exhibit considerable genetic advancement and suggest substantial room for development through selective breeding. GA expressed as a proportion of the mean: This metric aids in comprehending the relative improvement in genetics. While low values like iron (Fe, 97.07%) demonstrate the difficulty of enhancing such qualities, high values like fruit weight (FW, 42.70%) and yield per plant (YP, 57.75%) indicate that these attributes can undergo significant improvement with selection.

Correlation

Numerous noteworthy positive and negative associations for different Wood Apple features were found in the study. FB (0.8383 **), DSW (0.7522 **), FW (0.6842 **), Pu (0.5072 **), K (0.4151 **), PS (0.4096 **), SNF (0.3349 *), Mg (0.3222 *), and RT (0.317 *) were all strongly positively correlated with the trait FL, for example. Furthermore, FL exhibited positive but non-significant correlations with characteristics such as Ca (0.2564 NS), FSW (0.2546 NS), and TSSPe (0.0782 NS), as well as a significant negative association with Fe (−0.2921 *). Likewise, FB exhibited a substantial negative association with Fe (−0.408 **) and a significant positive correlation with DSW (0.7703 **), FW (0.7652 **), Pu (0.4618 **), RT (0.4024 **), and Mg (0.3605 *).Mg (FW: 0.3576 *, DSW: 0.447 **), Pu (FW: 0.4786 **, DSW: 0.7199 **), DSW (FW: 0.7119 **, DSW: 0.7119 **), and FB (FW: 0.7652 **, DSW: 0.7703 **) all showed favourable associations withother qualities like FW and DSW. On the other hand, negative associations with Fe were noted in DSW (−0.1125 NS) and FW (−0.0444 NS). The study also showed that while SNF had a positive significant correlation with FSW (0.9074 **), it had a negative significant correlation with PP (−0.3167 *) and ViCPe (−0.2963 *). In contrast, traits like RT had positive but non-significant correlations with elements like TSSPe (0.2527 NS), Ca (0.2079 NS), and Mg (0.1651 NS).

Other important characteristics, such as Ca, also demonstrated strong positive associations with Pu (0.7214 **), Mg (0.6235 **), ViCPe (0.62 **), and K (0.6034 **). On the other hand, RS showed a negative non-significant association (−0.2639 NS). While TSSPe demonstrated substantial positive correlations with K (0.3847 **) and FW (0.3331 *), traits such as TSSP also shown a positive significant association with TSSPe (0.6962 **) and AcP (0.299 *). These results demonstrate the complex interrelationships among Wood Apple characteristics, where both strong positive and negative correlations are crucial to the fruit’s development.

Principal component analysis

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) conducted on 24 traits revealed 7 principal components (PCs) with eigenvalues greater than 1 (Fig. 10), accounting for varying degrees of total variance,22.74% for PC1, 12.84% for PC2, 10.18% for PC3, 8.96% for PC4, 7.39% for PC5, 6.03% for PC6, and 4.91% for PC7. Traits like DSW, FL, FB, FW, and Pu showed a positive correlation with the first principal component (PC1), but TSSP, YP, and Fe showed a negative correlation (Fig. 11). PC2 exhibited negative relationships with K, Pu, AcPe, and a number of other characteristics, but strong positive connections with SNF, FSW, FB, and FL. AcPe, AcP, TSSP, ViCP, and TSSPe all showed positive associations in PC3, but PL, TS, PS, YP, and RS showed negative correlations. PC4 had a negative correlation with YP, DSW, Pu, and FB, but a positive correlation with PL, Fe, TSSPe, TSSP, and PP.

FL, PP, ViCPe, and AcPe were found to have negative relationships with PC5, whereas TSSPe, RS, RT, TSSP, and Mg displayed positive connections. ViCPe, ViCP, Pu, SNF, and K showed negative correlations with PC6, while YP, Fe, Mg, FW, and RT showed substantial positive relationships. Finally, PC7 showed negative associations with YP, ViCPe, TSSP, RT, Mg, Fe, and Ca, but positive correlations with Pu, AcPe, AcP, FW, PL, and PP. These results demonstrate the main characteristics affecting the quality and development of Wood Apple fruit.

PCA biplot of traits

This principal component analysis (PCA) biplot illustrates the relationships between different phenotypic and biochemical traits and their contribution to variability (Fig. 12). According to the plot, Principal Component 1 (PC1) accounts for 22.736% of the overall variation, whereas Principal Component 2 (PC2) explains 12.837%. With their lengths signifying the degree of linkage, arrows show the contribution and correlation of attributes. On the positive axis of PC1, traits including FW (fruit weight), FL (fruit length), DSW (dry seed weight), and K (potassium) cluster together and exhibit high relationships, suggesting their relevance and mutual influence. Different dimensions are influenced by traits on the opposing axis, such as FSW (fresh seed weight) and SNF (seed number per fruit). These traits appear to capture orthogonal components of phenotypic variance, based on the divergence of arrows.

PCA scatter plot for accessions

Based on their morphological and biochemical traits, 46 accessions (CHESW-1 to CHESW-46) are distributed along the PC1 and PC2 axes in the scatter plot. The fact that the accessions are dispersed over the four quadrants suggests a high degree of genetic and phenotypic variety. While CHESW-26, CHESW-11, and CHESW-8 are located on the extreme negative side of PC1, accessions like CHESW-1, CHESW-39, and CHESW-32 are situated on the extreme positive axis of PC2. This variance draws attention to the diversity among the accessions and may also show how adaptable or appropriate they are for various environmental settings or breeding goals.

Genotypic path analysis

Variable linkages were found in the genotypic path analysis of the qualities influencing yield potential (Supplementary Table 3). The residual showed that the independent variables accounted for 71.96% of the variation in YP, while the model was unable to explain 28.04% of it. Numerous variables, including FL, FB, FW, and RT, had non-significant direct impacts, and some of them had negative correlations with YP (e.g., FL with r = −0.0931 and RT with r = −0.0834). Nonetheless, a number of characteristics showed favourable indirect impacts via other variables. For instance, despite its negative indirect effects via other qualities like SNF and K, FB had a favourable direct influence on YP (0.2208) and positive indirect effects through variables like PS, DSW, and FSW. Similarly, TSSP had a negative direct effect on YP (−0.20565) but showed positive indirect effects through TSSPe, FSW, and AcP.

Cluster analysis

Clustering of the genetic material using Tocher’s method and Mahalanobis D2 distance revealed distinct groupings, with cluster 2 housing the highest number of genotypes21, followed by cluster 3 with 8 genotypes (Fig. 13). On the other hand, clusters 12, 13, 10, 14, 15, 16, and 11 each contained a single genotype, indicating a high degree of uniqueness or divergence for those genotypes. Traits contributing the most to genetic diversity were FW, with a contribution of 1125.73%, followed by FB at 732.83%, emphasizing the importance of these traits in driving genetic variability within the study material.

Significant diversity was found for several features in terms of trait means across the clusters. The highest FL (99.04), FW (375.58), and YP (119.13) values were found in Cluster 2, suggesting a high potential for productivity. The lowest values for variables such as FB (63.81), FW (143.59), and DSW (4.94) were found in cluster 15, indicating a less favourable genotype for qualities associated to yield. Additionally, Cluster 3 displayed high values for features such as ViCP (33.96), suggesting that it has a significant potential for agronomic attributes. The need of selecting for numerous qualities at the same time in breeding programs to optimize genetic potential and yield outcomes is highlighted by the variety in traits between clusters.

Discussion

The findings from the ANOVA analysis provide insights into the genetic and phenotypic diversity present in the wood apple accessions for various traits. There is a lot of genetic variety among the accessions, which can be used in breeding programs targeted at enhancing important agronomic qualities like fruit weight (FW) and yield per plant (YP), as indicated by the high variance in these traits. Significant differences between accessions are also implied by the substantial F-values for parameters like fruit length (FL) and seed number per fruit (SNF), which could be explained by varying genetic backgrounds or environmental factors. Because they may suggest homogeneity or a lack of diversity in certain qualities among the accessions, the non-significant traits like RS, TS, and Fe are interesting. Either a stable characteristic within the species or external conditions reducing the trait’s variability could be the cause of this. Certain elements, including calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe), have significant coefficients of variation, which implies that they may not be genetically varied within this group of accessions or may be more influenced by external environmental influences27,28. Conversely, low-variation traits like RT and K might be a sign of environmental or genetic stability. All things considered, these findings offer valuable information for locating accessions with desired characteristics for breeding initiatives and additional research into the genetic and environmental elements affecting these characteristics in wood apples.

The data presented in Table 1 suggests substantial genetic and environmental variation in the traits of wood apple accessions, which is important for understanding the potential for selection in breeding programs. The genotypic variance is significantly greater than the environmental variance for numerous characteristics, including fruit weight (FW), seed number (SNF), and total soluble solids (TSSP). This suggests that selection in breeding programs could successfully improve these qualities, which are mostly determined by genetic factors. Alongside genotypic diversity, some variables, such as fruit length (FL) and fruit breadth (FB), exhibit significant environmental variance. This implies that environmental variables have a major influence on these features in addition to genetic influences. Therefore, when choosing for these features, breeders should take the environment into account. Traits such as seed number per fruit (SNF), pulp weight (Pu), and total soluble solids (TSSPe) show relatively low environmental variance, implying that they are more stable and less influenced by environmental fluctuations. This stability can be an advantage for selecting consistent traits across different growing conditions8,27,29,30,31,32,33,34.

The significant variation in traits like fruit weight (FW) and yield per plant (YP) suggests that these attributes offer opportunities for selection and improvement in breeding initiatives aimed at boosting productivity. However, unless exact nutrient content targets are needed, low variance traits like calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe) would not be as useful for breeding. All things considered; this table provides breeders with a starting point for rating highly genetically variable traits while accounting for environmental factors. They are able to create better wood apple varieties by making informed decisions as a result.

Genetic traits

The genetic parameters in Table 2 provide valuable insights into the potential for improving various traits of wood apple through breeding. Fruit weight (FW) and seed number per fruit (SNF) are examples of features that show high GCV and heritability, suggesting that they are mostly genetically influenced. Programs to breed for these features would probably be effective since genetic selection would produce notable advancements. Furthermore, these features’ high genetic advance (GA) indicates that selection might provide significant genetic gains. Conversely, low heritability ratings for variables like calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe) suggest that environmental factors, rather than genetics, have a greater influence on their manifestation. This implies that it might be more difficult to improve certain traits through breeding, and breeding programs aimed at them would have to take environmental factors into consideration or consider other breeding techniques like marker-assisted selection9,14,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41

Certain traits, like pulp weight (Pu) and total soluble solids (TSSPe), exhibit increased environmental variance and relatively low heritability, suggesting that environmental factors may have a bigger impact on these traits. It could be necessary to carefully balance genetic and environmental factors when breeding for these features. Fruit weight (FW) and yield per plant (YP) are two traits that show strong genetic progress as a percentage of the mean, indicating that selection can greatly enhance these features. Breeding efforts seeking to boost productivity should give priority to such features because the anticipated benefits would be significant. The information shows that several wood apple accessions’ features are highly heritable and genetically varied, which makes them perfect candidates for selection-based improvement. To maximize their expression, characteristics with low heritability—like calcium and iron content—may need to be bred using different methods or concentrate on environmental management techniques.

Correlation

The study on Feronia limonia highlights the complex interrelationships among various fruit traits, providing valuable insights for improving cultivation and fruit quality (Fig. 14). Fruit Length (FL) is positively correlated with Fruit Breadth (FB), Fresh Weight (FW), Dry Seed Weight (DSW), and Potassium (K), indicating that larger fruits typically have more developed physiological characteristics. This confirms earlier research that found a correlation between fruit size and increased weight and nutrient accumulation42,43. Remarkably, the negative association (−0.2921) between FL and iron (Fe) suggests that larger fruits may contain less Fe, necessitating additional research on nutrient dynamics44.The notion that seeds development and total fruit size are strongly related is supported by the positive correlation between DSW and FW (0.7119)45. Furthermore, findings from prior studies on the synergistic effects of these nutrients are supported by the substantial positive correlations of potassium (K) and magnesium (Mg) with features like FB, DSW, and FW, which emphasize their involvement in stimulating growth and fruit development27,46,47,48. Calcium (Ca) is essential for fruit quality, perhaps improving texture and nutrient absorption, according to correlations between Ca and pulp content (Pu)49. Moreover, the inverse relationship between calcium and root disease (RS) would suggest that calcium may have a protective effect against problems with root health.

The relevance of sugars and vitamins in fruit quality is highlighted by the significant connections found between Total Soluble Solids (TSSP) and Vitamin C concentration (ViCPe). According to the correlation between TSSP and Acidity (AcP) (0.299), sugar buildup and organic acid metabolism are intimately related, and this has an impact on the fruit’s flavour and nutritional makeup9,36,37,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58.

PCA biplot

The PCA biplot’s arrow grouping and direction reveal important information about the relationships between the attributes. Fruit weight, fruit length, and potassium levels are examples of traits that cluster together, indicating that selection for one may have a beneficial effect on others. This is an important finding for breeding programs aimed at increasing output. On the other hand, the separation of other characteristics, such as the quantity of seeds per fruit, emphasizes the existence of trade-offs that might need to be controlled throughout the selection process. The clustering pattern highlights the significance of phenotypic flexibility in complex contexts, which is consistent with findings by27,48,59 in investigations on other underused crops. While some variables are important predictors of variation, PC1 and PC2’s contributions show that additional PCs could be necessary to capture subtle phenotypic changes.

The effectiveness of the dimensionality reduction made possible by PCA is seen by the scree plot. Principal components with eigenvalues larger than one are frequently kept for significant analysis in accordance with Kaiser’s criterion. In this instance, most of the crucial variation in the data is captured by the first few components, especially PC1 and PC2. From PC3 onward, the explained variance gradually decreased, indicating that these components primarily provide noise or redundant information rather than important information for the differentiation of phenotypic or biochemical traits22,60. Selecting only a few principal components for efficient trait selection in breeding programs and genetic diversity assessments is further supported by the “elbow point” at PC7, where the curve starts to level out. These findings align with previous research27, where PCA was instrumental in reducing complexity for genotype characterization.

Path analysis

The genotypic path analysis results in this study revealed complex relationships between various traits and yield potential (YP), indicating that indirect effects through other traits often played a more significant role than direct effects in influencing YP. In line with recent research that found indirect effects to be more relevant in explaining variance in crop yield potential, it was observed that various traits, including FL, FB, and FW, had non-significant effects on YP61,62. The significance of comprehending not just direct trait interactions but also how they interact with other agronomic factors is highlighted by the fact that, although FB had a favourable direct effect on YP, it had a negative indirect effect through traits like SNF and K. According to earlier research, microelements like Fe have been demonstrated to directly increase yield potential by improving photosynthetic efficiency and nitrogen uptake. Similarly, characteristics like Fe and Mg showed beneficial direct benefits on YP63.

The fact that PS had the biggest direct beneficial impact on YP (1.3176), indicating a crucial role in boosting yield potential, was one of the study’s most important discoveries. This is consistent with earlier studies that highlight how important photosynthesis (PS) and associated characteristics are in determining crop productivity64,65,66. Furthermore, through indirect pathways, features like DSW, TS, and PL also favorably impacted YP, supporting results from previous research that showed how traits like plant structure and seed weight indirectly affect yield67,68,69,70.

The study also revealed that although some variables, such as TSSPe, had favorable direct impacts, their detrimental indirect effects—especially through PP, FL, and FSW—emphasized the intricacy of the interactions between traits that can either increase or decrease yield. These findings pointout the critical role of precise trait selection in perennial crops, where long breeding cycles demand careful identification and prioritization of yield-associated traits. Emphasizing selection over broader breeding approaches ensures the retention and enhancement of traits that contribute most directly to long-term productivity and crop improvement.71,72.

Cluster

Significant genotype diversity was found when the genetic material was clustered using Tocher’s technique and Mahalanobis D2 distance. Cluster 2 had the most genotypes21, followed by cluster 3 with 8. A higher degree of divergence or uniqueness among these groups was indicated by the single genotypes found in the remaining clusters, which included 12, 13, 10, 14, 15, 16, and 11. These results are consistent with earlier research that effectively used Tocher’s method to classify genotypes according to their genetic distance, enabling a deeper comprehension of the genetic structure71,73. Furthermore74, contribution study showed that variables like FW and FB, were important in determining the genetic diversity. Such results reinforce the significance of these traits in genetic improvement programs and their role in enhancing productivity and performance of crops7,27.

Significant variance was found in several significant agronomic traits when the means of the attributes across the clusters were analysed. Similar tendencies have been noted in other crops, and cluster 2 showed the highest values for FL (99.04), FW (375.58), and YP (119.13), suggesting that it may have higher production qualities75,76,77,78. The genotype with the lowest yield potential, however, was cluster 15, which showed the lowest values for FB (63.81), FW (143.59), and DSW (4.94). These outcomes are in line with research demonstrating the importance of characteristics such as FW and FB as potent productivity predictors59. Additionally, Cluster 3 showed high values for certain traits, such ViCP (33.96), which would suggest that it could improve quality traits. According to79, the variability seen in these clusters emphasizes the need to choose genotypes with a wide variety of desirable traits to maximize breeding techniques meant to increase both yield and quality. New genotypes with improved genetic potential for a variety of agronomic traits may result from this strategy.

The genotypes CHESW-6, CHESW-10, CHESW-22, CHESW-27, CHESW-33, CHESW-38, and CHESW-42 exhibited distinctive morphological and nutritional attributes of significance for breeding and value addition. Morphologically, CHESW-6 possessed large leaves and a semi-spreading habit, indicating high photosynthetic potential. CHESW-10 and CHESW-33, both with flattened fruits, represented rare shape variation, with CHESW-33 additionally showing extremely compact foliage suitable for dwarf or container cultivation. CHESW-22, with small leaves and long leaflets on a spreading canopy, offers advantages for high-density planting. Green-fruited types CHESW-27, CHESW-38, and CHESW-42 present unique market appeal; CHESW-27 and CHESW-42 exhibit compact, erect growth with small leaves, while CHESW-38 combines a spreading habit with moderate foliage. Nutritionally, CHESW-6 combined high fruit weight, elevated pulp TSS, and appreciable vitamin C, making it suitable for beverages. CHESW-10 showed a balanced TSS–acidity ratio and attractive fruit surface, enhancing consumer appeal. CHESW-22 was notable for high vitamin C and above-average TSS, ideal for functional foods. CHESW-27 demonstrated moderate acidity, good TSS, and early bearing (third year after planting). CHESW-33 had high pulp recovery and total sugars, suiting dessert and processing purposes. CHESW-38 maintained consistent TSS and vitamin C across seasons. CHESW-42 recorded the highest vitamin C content, erect dwarf growth for high-density planting, bunch-bearing fruits, late maturity, and high yield despite smaller fruit size. The greenish fruit surface of CHESW-27 and CHESW-42 at maturity enhances visual freshness and market appeal. Collectively, these genotypes offer a valuable genetic pool for developing wood apple cultivars suited to specific orchard systems, processing needs, nutritional goals and consumer preferences as well as crop improvement programme in future.

Conclusion

The study on the genetic diversity, morphological, and quality traits of Feronialimonia (wood apple) in semi-arid regions reveals significant variation among the 46 accessions in various traits. High levels of genetic diversity were shown by traits such fruit weight (FW), seed number per fruit (SNF), total soluble solids (TSSP), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and yield per plant (YP), suggesting that they might be used in selective breeding programs. Certain features, such fruit length (FL) and pulp weight (Pu), have significant environmental influences, according to the analysis, indicating that environmental factors can have a big impact on how those qualities manifest. The significance of variables like FW and SNF, which shown high heritability and genetic advancement, making them appropriate candidates for selection in breeding programs aimed at enhancing yield and quality, was further highlighted by the genetic analysis. The principal component analysis (PCA) revealed the intricate correlations between many features and highlighted the major elements affecting the development of wood apple fruit. Additionally, the genetic diversity among the accessions was shown by cluster analysis, which identified unique clusters that might direct the creation of better genotypes for breeding. These findings emphasize the value of preserving a varied Feronialimonia genetic pool for upcoming breeding initiatives and the possibility of enhancing fruit quality and productivity by focused selection. It would be beneficial to conduct additional research on characteristics, such disease resistance and environmental stress tolerance, to create more resilient cultivars that are appropriate for semi-arid environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Janick, J. & Paull, R. E. The encyclopedia of fruit and nuts. CABI Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996684.0000 (2008).

Singh, A. K. et al. Fruit crops of Indian semi-arid regions: significance, conservation and utilization strategies—a review. Curr. Hort. 13(2), 13–27 (2025).

Raut, S. K. Wood Apple (Feronialimonia) in Indian horticulture: a study on growth and production. Hortic. Int. 27 (3), 57–64 (2021).

Jones, E. R. Climate and adaptability of feronialimonia in semi-arid zones. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 38 (2), 150–154 (1992).

Rizvi, S. I. & Mishra, S. Medicinal uses and bioactive constituents of feronialimonia in traditional medicine. Pharmacol. Res. J. 61 (4), 274–279 (2013).

Syakri, R. et al. Bioactive compounds and medicinal properties of feronialimonia. Phytomedicine 82, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153063 (2021).

Yadav, S., Rani, S. & Singh, S. Genetic diversity in plant breeding and its importance. Adv. Plant. Breed. Biotechnol. 8 (2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42287-021-00307-5 (2021).

Metson, A. J. Methods of Chemical Analysis for Soil Survey Samplesvol 12 (Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, 1956).

Kama, R. et al. Identity and diversity of invasive plants affecting the growth of native Lactuca indica. ACS Omega. 8 (20), 17983–17991. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01139 (2023).

Murrinie, E. D., Yudono, P., Purwantoro, A. & Sulistyaningsih, E. Morphological and physiological changes during growth and development of wood-apple (feronialimonia (l.) swingle) fruit. Int. J. Bot. 13, 75–81 (2017).

Ghosh, S. et al. Physiochemical composition of wood Apple (Feronialimonia) fruit and its potential applications in food industry. Food Sci. Technol. 45 (1), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfst.2019.11.001 (2020).

Nguyen, B. T. et al. Benchmarking bulb yield, medicinal sulfur compounds, and mineral nutrition of Garlic varieties. ACS Omega. 9 (45), 45240–45250. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c06678 (2024).

AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. (2005).

Yadav, L. P., Koley, T. K., Tripathi, A. & Singh, S. Antioxidant potentiality and mineral content of summer season leafy greens: comparison at mature and microgreen stages using chemometrics. Agric. Res. 8, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40003-018-0378-7 (2019).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R. & Lamuela-Ranventos, R. Analysis of total phenols other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Method Enzymol. 299, 152–178 (1999).

Tandon, H. L. S. Methods of analysis of soils, plants, waters, fertilizers & organic manures. fertilizer development and consultation organisation, New Delhi. (1993).

Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 24, 417–441 (1933).

Pearson, K. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philosophical Magazine Ser. 6 (11), 559–572 (1901).

Sokal, R. R. & Michener, C. D. A. Statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull. 28, 1409–1438 (1958).

Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R (Posit Software, 2023).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21606-5

Jolliffe, I. T. Principal component analysis for special types of data (pp. 338–372). Springer New York. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-2244

Kaiser, H. F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 23 (3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF0228923 (1958).

Jackson, J. E. A user’s guide to principal components (Wiley, 2005).

Abdi, H. & Williams, L. J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Stat. 2 (4), 433–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.101 (2010).

Kaiser, H. F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20 (1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116 (1960).

Singh, A. K. et al. Descriptors for characterization and evaluation of Bael (Aegle Marmelos (L.) Correa ex Roxb.) germplasm for utilization in crop improvement. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-024-01903-w (2024).

Yadav, L. P. et al. Nutritional, antioxidants and protein profiling of leaves of Moringa Oleifera germplasm. S Afr. J. Bot. 165, 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.01.012 (2024).

Akshay, G., Tayde, U. A., Raut, A. D., Wawkar, Dnyaneshwar, S. & Ravankar Character association studies in wood Apple (Feronialimonia L.) for yield and yield associated traits. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 8 (5), 697–702 (2024).

Kerkar, S., Patil, S., Arya, S., Dabade, A. & Sonawane, S. Limoniaacidissima: versatile and nutritional fruit of India. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538362.2020.1737302 (2020).

Kumar, P. et al. Correlation studies in wood Apple (Feronialimonia L.) in Bundelkhand region of Uttar Pradesh. Indian J. Pure ApplBiosci. 9 (1), 316–321 (2021).

Din, A. et al. Comparative analysis of physical and chemical mutagenesis in Chrysanthemum cv. ‘Candid’: assessing genetic variation and breeding potential. ACS Omega. 8 (46), 43836–43849. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c05723 (2023).

Ali, F. et al. Morphological, biochemical, and molecular characterization of exotic Brassica germplasm. ACS Omega. 8 (47), 44773–44783. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c05688 (2023).

Nawaz, I. et al. High genetic diversity in the Himalayan common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) germplasm with divergence from its center of origin in Mesoamerica and Andes. ACS Omega. 8 (51), 48787–48797. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c05150 (2023).

Yadav, L. P. et al. Genetic diversity, morphological traits, quality traits and antioxidant potentiality of Coccinia grandis germplasm under rainfed semi-arid region. Sci. Rep. 14, 868. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49091-4 (2024).

Noreen, S. et al. Morphological and molecular characterizations of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their influence on soil physicochemical properties and plant nutrition. ACS Omega. 8 (36), 32468–32482. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c02489 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparative study on morphological features and chemical components of wild and cultivated Angelica sinensis based on bionic technologies and chemometrics. ACS Omega, 9(40), 41408–41418. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c04400

Meena, R. et al. Morphological diversity assessment in date palm (Phoenix dectylifera L.) germplasms grown under hot arid region of India. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 1159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07194-2 (2025).

Yadav, L. P. et al. Genetic variability, morphological diversity, and antioxidant potential in gynoecious Coccinia accessions: implications for breeding and biofortification. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 844. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06335-x (2025).

Singh, A. K. et al. Characterization and evaluation of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) germplasm: implications for tree improvement strategies. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 396. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06415-y (2025).

Yadav, L. P. et al. Genetic diversity, morphological and quality traits of Momordica dioica. Sci. Rep. 14, 30241. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81828-7 (2024).

Ming, R., Hou, S. & Zhang, Z. Correlation between fruit size and nutrient concentration in citrus species: implications for breeding. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 133, 26–35 (2019).

Mohsina, J. D. & RaihanaAfroz, M. S. Assessment of nutritional value of Limoniaacidissima L. (Wood Apple). Dhaka Univ. J. Sci. 70 (2), 48–52 (2022).

Kumar, A. & Sharma, V. Nutrient interactions in tropical fruit crops: A study on the effects of iron and calcium on fruit quality. Plant. Nutrient Sci. 41 (4), 209–216 (2020).

Davis, P., Thompson, D. & Kumar, S. Fruit development in tropical trees: A review of factors influencing fruit size and seed weight. J. Trop. Agric. 45 (3), 124–136 (2019).

Singh, G., Sharma, H. & Mehra, R. Role of potassium in plant growth: insights from recent studies on tropical fruit crops. Plant. Growth Regul. 68 (4), 155–163 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Morpho-biochemical characterization and molecular diversity analysis of bael [Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa.] germplasm using gene-targeted molecular markers. Sci. Hortic. 339, 113900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113900 (2025).

Singh, A. K. et al. Genetic diversity assessment of bael (Aegle marmelos) varieties using morphometric, yield, and quality traits under semi-arid conditions. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 1143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06985-x (2025).

Singh, B. & Raj, M. Calcium’s role in fruit development and quality. Hortic. Adv. 52 (3), 112–123 (2021).

Jain, R., Mehta, P. & Sharma, N. Influence of organic acids and sugars on the sensory and nutritional properties of tropical fruits. J. Hortic. Sci. 58 (1), 56–65 (2021).

Khan, M. A., Singh, K., Patel, K. K. & Siddiqui, M. Some physical properties of wood Apple (Feronialimonia L). Recent. Advancement Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2 (1), 79–86 (2019).

Lamani, S., Anu-Appaiah, K. A., Murthy, H. N., Dewir, Y. H. & Rikisahedew, J. J. Analysis of free sugars, organic acids, and fatty acids of wood Apple (Limoniaacidissima L.) fruit pulp. Horticulturae 8 (67). https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8010067 (2022).

Sharma, N. et al. Beneath the rind: A review on the remarkable health benefits and applications of the wood Apple fruit. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29202 (2024).

Dowarah, B., Deb, P., Rana, G. & Sushmitha, K. Fruit physico-chemical studies of some local wood Apple (Limoniaacidissima L.) genotypes. Int. J. Minor. Fruits Med. Aromatic Plants. 7 (1), 53–56 (2021).

Rajangam, J., Sankar, C. & Maheswari, M. U. Characterization and evaluation of wood apple (Feronialimonia L.) genotypes for yield and quality. International Tropical Fruits Network (TFNet). (2022).

Yadav, L. P., Gangadhara, K. & Apparao, V. V. Evaluation of drumstick variety Thar Harsha under rainfed semi-arid conditions for growth, yield and quality along with antioxidant potentiality and nutrient content. S Afr. J. Bot. 148, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2022.04.005 (2022).

Murrinie, L. et al. Application of wood Apple (Feronialimonia) in semi-arid regions for soil reclamation and ecosystem enhancement. J. Hortic. Sci. 29 (1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12345-017-0094-8 (2017).

Taş, A., et al. (2023). Fruit quality characteristics of service tree (Sorbus domestica L.) genotypes. ACS Omega, 8 (22), 19862–19873. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01788

Agarwal, P., Bhandari, A. & Verma, S. Role of morphological and molecular markers in genetic diversity assessment for crop improvement. Int. J. Plant. Breed. 12 (3), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11122-022-1012-5 (2023).

Rashmi Srivastava, N., Mishra & Neetu Mishra. Evaluation of the extraction hours and solvent concentrations on secondary metabolites and antioxidant activity of Feronialimonia fruit. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 12 (3), 463–471 (2021).

Patel, R. R., Yadav, R. K. & Singh, D. Genotypic path analysis and yield potential in rice under drought conditions. Field Crops Res. 272, 108247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108247 (2021).

Zhang, M., Xu, Q. & Wang, J. A path analysis of yield potential and its related traits in soybean under varying water stress conditions. Field Crops Res. 270, 108170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2022.108170 (2022).

Jin, Y., Li, X. & Zhang, W. Micronutrient management in agriculture for improving yield potential and nutritional quality. Agric. Syst. 181, 102796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.102796 (2023).

Sanchez, P. A., Swaminathan, M. S. & Naylor, R. L. The role of photosynthesis in driving global crop productivity. Nat. Sustain. 3 (7), 620–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0532-0 (2020).

Singh, R., Kumar, A. & Gupta, P. Optimizing agronomic traits for enhanced yield potential in wheat: A path analysis approach. Agron. J. 113 (5), 3489–3498. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20571 (2021).

Raut, U. A., Bhuyar, S. A., Bharad, S. G. & Shinde, M. S. Character association studies in wood Apple (Feronia limonia L.) for yield and yield contributing traits. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 13 (12), 10978–10982 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Li, H. & Zhang, Y. Integrated analysis of agronomic traits and their indirect effects on yield in barley. J. Agric. Sci. 159 (2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002185962000045X (2021).

Wu, X., Zheng, Z. & Liu, Y. Induced mutations for improving yield in maize: A path analysis approach. Crop Sci. 62 (3), 1472–1483 (2022).

Lamani, S. & Murthy, H. N. Diversity of wood Apple (Limoniaacidissima L., Rutaceae) genetic resources in South India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 69 (10), 2929–2946 (2022).

Srivastava, R. et al. Influence of fruit stages on chemical compositions, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity of wood Apple (Feronialimonia (L.) Swingle). Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42223 (2025).

Goud, S. B., Yadav, R. S. & Reddy, M. R. Genetic diversity and trait associations in crop improvement. Indian J. Genet. Plant. Breed. 80 (4), 432–444. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijgpb.ijgpb_136_20 (2020).

Rizvi, S. I. & Mishra, N. Traditional Indian medicines used for the management of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/712092 (2013).

Lamani, S. Diversity in tree and fruit traits of wood apple (Limoniaacidissima L.) genetic resources collected from South India. Research Square, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5503-0202. (2022).

Singh, R. K. The D2 statistic and its applications in plant breeding. J. Indian Soc. Agricultural Stat. 33 (1), 1–10 (1981).

Sahu, R. K., Kumar, P. & Das, P. Clustering of genotypes using Mahalanobis D2 distance and its application in breeding. J. Agricultural Sci. Technol. 24 (2), 169–177 (2022).

Shreya, R. et al. Morphological and physiological characteristics of Feronialimonia. J. Trop. Agric. 68 (3), 179–188 (2020).

Sujitha, S. Insights into the invitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of Limonia acidissima fruits. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 11, 1–11 (2021).

Syamsuri Syakri, N. A., Syahrana, A., Ismail, K. A., Tahir & Anshari Masri. A review: testing antioxidant activity on Kawista plants (limonia acidissima l.). Indonesia. J. Med. Sci. 9 (F), 281–287 (2021).

Srinivasan, S., Reddy, B. S. & Narayanasamy, R. Multi-trait selection and genetic improvement of yield and quality in plant breeding programs. Crop Sci. J. 60 (6), 1821–1830. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2019.07.0442 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Director, ICAR-Central Institute of Arid Horticulture, Bikaner, India for providing the necessary facilities for carrying out this experiment and also express our appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-194), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The study was supported byICAR-Central Institute of Arid Horticulture, Bikaner, India for providing the necessary facilities for carrying out this experiment.For APC support, Authors are thankful to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-194), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, VY, AKS & LPY; writing—review and editing, VY, AKS; DSM, LPY, VVAR, AS, PR, NKM, JR, MHS, SA, & SK; Statistical Analysis- SA, MHS, LPY; Funding, Data analysis, Conceptualization, MHS, SA, & SK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Germplasm collection and identification

The germplasm collection and identification were done by Dr. Vikas Yadav, Scientist-Fruit Science and team, ICAR- Central Horticultural Experiment Station (CIAH RS), Vejalpur, Panchmahals (Godhra), Gujarat under the project: Collection, introduction, and evaluation of wood apple and custard apple under semi-arid conditions.

Statement specifying permissions

For this study, we acquired permission to study wood apple issued by the Agricultural and Natural Resources Ministry of India.

Statement on experimental research and field studies on plants

The either cultivated or wild-growing plants sampled comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and domestic legislation of India.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, V., Singh, A.K., Mishra, D.S. et al. Genetic diversity, quality traits, antioxidant properties, and nutrient composition of Feronia limonia accessions from a semi-arid region for breeding and quality improvement. Sci Rep 15, 35352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19356-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19356-1