Abstract

This study examined the associations between different domains of physical activity, leisure-time (LTPA), occupational (OPA), and transportation-related (TPA), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk among U.S. adults. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2008 through March 2020 were used. Physical activity was self-reported using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. Weekly minutes of LTPA, OPA, and TPA were calculated and categorized as: <150, 150–299, and ≥ 300 min. CVD was defined as self- or proxy-reported heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, or stroke. Weighted multivariable logistic regression was used to assess associations. Six sensitivity analyses were conducted. Meeting the physical activity guidelines (≥ 150 min/week) through LTPA or TPA was associated with significantly lower odds of CVD, 22% [OR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.70–0.88] and 40% [OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.50–0.72], respectively. This was supported by sensitivity analyses. In a separate dose-response analysis, individuals engaging in twice the recommended minimum (≥ 300 min/week) experienced even greater reductions in CVD risk, with 30% lower odds for LTPA [OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.60–0.80] and 41% lower odds for TPA [OR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.47–0.74]. In contrast, OPA was not significantly associated with CVD risk at any activity level. Among U.S. adults, higher LTPA and TPA are associated with lower CVD risk, particularly at higher levels of activity. In contrast, OPA does not show the same protective effect. The associations between physical activity and CVD risk vary by context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains one of the leading causes of illness and death worldwide, placing a substantial burden on global health systems and economies1. Over the past few decades, the number of people living with CVD has nearly doubled, from 271 million in 1990 to 523 million in 2019 2. Despite progress in diagnosis and treatment, CVD-related deaths have continued to rise, increasing from 12.1 million in 1990 to 18.6 million in 20192. This growing trend is largely driven by population aging and ongoing exposure to major risk factors2. Among the modifiable lifestyle factors, physical activity stands out as a key element in preventing and managing CVD3. Regular physical activity is not only linked to a lower risk of developing CVD but also helps slow disease progression and improve long-term outcomes for those already living with the condition3,4.

While the protective effects of physical activity on cardiovascular health are well established, not all forms of physical activity appear to offer the same benefits. Physical activity occurs across various domains, including leisure-time physical activity (LTPA), occupational physical activity (OPA), and transportation-related physical activity (TPA)5. LTPA is typically voluntary and includes recreational sports or structured exercise, often accompanied by sufficient rest and recovery6. In contrast, OPA consists of physical tasks performed as part of one’s job, which are often repetitive, performed under time constraints, and may involve inadequate recovery7,8. TPA primarily includes walking or cycling as a means of commuting9. Emerging evidence suggests that the health impacts of physical activity may vary depending on the domain5,10,11,12.

Although prior research has explored the associations between OPA and LTPA and CVD, existing studies often face methodological limitations. For example, in a U.S. study, OPA was assessed using Likert-scale responses on exertion and standing/walking at work8, an approach that does not quantify activity volume and limits comparability with guideline-based recommendations, which are typically time-based. TPA, a distinct and increasingly relevant domain, has seldom been evaluated concurrently with other physical activity domains in the same population8,13. Moreover, some studies relied on a narrow range of survey years8,13, limiting temporal scope and generalizability. These limitations highlight the need for further research using time-based metrics across all activity domains and broader data coverage to better understand how different types of physical activity relate to CVD risk.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the associations between different physical activity domains (LTPA, OPA, and TPA) and the risk of CVD in U.S. adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007–2020. Specifically, we first assessed whether meeting the current physical activity guidelines was associated with CVD risk, and then explored potential dose-response relationships across different activity levels. Given that sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, educational attainment, poverty-income ratio (PIR), and marital status may influence both physical activity behaviors and CVD risk, we also evaluated whether the associations between physical activity and CVD risk differed across these characteristics. By differentiating among physical activity domains and investigating subgroup differences, we sought to provide more comprehensive insights into how specific patterns of physical activity influence cardiovascular health, ultimately informing more targeted and effective public health strategies.

Study population

This cross-sectional study utilized data from the NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html). NHANES is a nationally representative survey designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. It employs a complex, multistage probability sampling method to select participants from the non-institutionalized civilian population across the United States. Data collection involves structured interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. The survey protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Committee, and all data is publicly available. Therefore, no additional ethical approval was required for this secondary analysis.

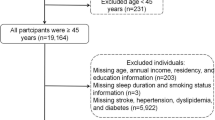

To minimize the potential impact of altered physical activity patterns due to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic, we restricted our analysis to data collected before the pandemic, specifically, from the 2007–2008 cycle through March 2020. After excluding individuals with missing data on key exposure variables (physical activity measures) or outcome variables (CVD conditions), a total of 37,879 participants aged 20 years and older were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Physical activity

Physical activity levels were assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), a validated instrument developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). This questionnaire captures information on the frequency (days per week), duration (minutes per day), and intensity (moderate or vigorous) of physical activity across three distinct domains: OPA, TPA, and LTPA. To estimate total energy expenditure, vigorous-intensity physical activity was converted into an equivalent amount of moderate-intensity activity, with one minute of vigorous activity counted as two minutes of moderate activity, an approach supported by previous research16. Using this conversion, we calculated the total weekly minutes of OPA and LTPA by doubling the time spent in vigorous activity and adding it to the time spent in moderate activity. TPA, which primarily included walking and cycling, was classified as moderate in intensity.

In line with the 2020 WHO physical activity guidelines, adults, including those with chronic conditions, are advised to engage in 150 to 300 min of moderate-intensity activity, 75 to 150 min of vigorous-intensity activity, or an equivalent combination each week17. Based on these recommendations, participants were initially categorized into two groups: (1) those who met the minimum recommended activity level (≥ 150 min/week of moderate-intensity equivalent activity), and (2) those who did not (< 150 min/week). For further analysis, we classified participants into three groups based on total weekly activity: (1) less than 150 min, (2) 150 to 299 min, and (3) 300 min or more.

Cardiovascular diseases

CVD served as the primary outcome in this study and was defined as the presence of at least one of the following self-reported conditions: heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, or stroke. In NHANES, information on these conditions was collected through structured interviews, based on either self-report or proxy-report. Participants were identified as having CVD if they answered “yes” to specific questions corresponding to each condition: heart failure (MCQ160b), coronary heart disease (MCQ160c), angina (MCQ160d), heart attack (MCQ160e), and stroke (MCQ160f). For analytical purposes, individuals reporting a diagnosis of any of these conditions were classified as having CVD.

Covariates

We adjusted for a range of potential confounders that could influence physical activity levels or CVD outcomes. These included sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle behaviors, and chronic health conditions (Supplementary material, Table S1). Sociodemographic variables consisted of age (categorized as < 65 and ≥ 65 years), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (Mexican American, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other), marital status (Married/Living with Partner, Widowed/Divorced/Separated, or Never Married), educational attainment (< 9 years, 9–12 years, and > 12 years), and PIR. PIR was grouped into three categories: low income (PIR < 1), middle income (1 ≤ PIR < 4), and high income (PIR ≥ 4)18.

Lifestyle-related factors included body mass index (BMI), smoking status (never, former, or current), and alcohol consumption. BMI was classified into four groups according to WHO guidelines. Alcohol consumption was defined based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: men who consumed no more than two drinks per day and women who consumed no more than one were classified as moderate drinkers, while those who exceeded these limits were considered heavy drinkers19. Due to a substantial amount of missing data on alcohol use, participants with missing values were categorized separately. Chronic conditions considered in the analysis were hypertension, diabetes, and cancer.

Statistical analysis

Survey weights were applied to account for NHANES’s complex multistage sampling design, ensuring that the findings are generalizable to the broader U.S. population. We compared participant characteristics between individuals with and without CVD. For continuous variables, results were reported as means with standard deviations (mean ± SD) and compared using independent t-tests. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages and analyzed using chi-square tests. To assess the associations between physical activity across three domains and CVD, we conducted weighted multivariable logistic regression analyses. Three models were constructed: the crude model included no covariates; Model I adjusted for sociodemographic factors; and Model II further adjusted for lifestyle variables and chronic conditions. Additionally, we conducted prespecified subgroup analyses to describe the association between physical activity and CVD risk across sociodemographic factors and performed interaction tests to formally evaluate effect modification. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2). A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

In our primary analysis, we applied multiple imputation for all covariates except alcohol consumption. To assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses: (1) a complete-case analysis excluding participants with any missing data; (2) an analysis excluding alcohol consumption as a covariate while adjusting for all other variables; and (3) a multiple imputation analysis that included alcohol consumption, with all missing values imputed using chained equations under the assumption of missing at random. Additionally, we conducted further sensitivity analyses to test the consistency of our results: (4) models additionally adjusted for other physical activity domains; (5) categorization of physical activity time based on tertiles instead of guideline-based thresholds; and (6) assessment of the joint associations of LTPA, TPA, and OPA. Together, these analyses allowed us to evaluate the robustness of our findings under varying model specifications, covariate adjustments, and assumptions about missing data, particularly concerning alcohol consumption.

Results

A total of 37,879 participants were included in the analysis, with a mean age of 49.83 years (SD: 17.77), and 51.59% were female (Table 1). Compared to participants without CVD, those with CVD were more likely to be older, male, Non-Hispanic White, have a lower level of education, a higher BMI, a history of chronic conditions, and a history of smoking or current smoking status. Additionally, individuals with CVD more often reported engaging in less than 150 min of physical activity per week across all three physical activity domains.

The associations between physical activity domains and CVD were examined using weighted logistic regression (Table 2). In the crude model, participants who met the recommended ≥ 150 min of weekly physical activity had significantly lower odds of CVD compared to those who engaged in less than 150 min. These associations remained significant for LTPA and TPA after adjusting for sociodemographic factors (Model I) and further adjusting for lifestyle behaviors and chronic health conditions (Model II). However, OPA of ≥ 150 min per week was not significantly associated with reduced CVD risk in the fully adjusted model. Specifically, participants reporting ≥ 150 min of LTPA had a 22% lower likelihood of CVD [OR: 0.78 (95% CI: 0.70–0.88)], and those reporting ≥ 150 min of TPA had a 40% lower likelihood [OR: 0.60 (95% CI: 0.50–0.72)].

To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, results from the complete-case analysis and the model excluding alcohol consumption as a covariate were consistent with those of the primary analysis (Supplementary Tables S2–S3). We further included alcohol consumption in the imputation process and found similar associations (Supplementary Table S4). Additional sensitivity analyses also confirmed the robustness of our results: adjusting for other physical activity domains (Supplementary Table S5), categorizing physical activity time using tertiles rather than guideline-based thresholds (Supplementary Table S6), and examining the joint associations of LTPA, OPA, and TPA (Supplementary Table S7). In the joint analysis, compared with the reference group (low LTPA and low OPA), only the group with high LTPA and low OPA had a significantly lower risk of CVD (OR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.70–0.94). High OPA alone or in combination with high LTPA was not associated with a statistically significant reduction in CVD risk. A similar pattern was observed in the joint analysis of TPA and OPA. These findings are consistent with the primary results and further support the robustness of our conclusions across different model specifications and assumptions.

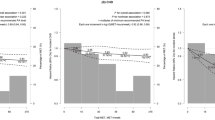

To explore potential dose-response relationships, weekly minutes of physical activity were categorized into three groups: <150 min, 150–299 min, and ≥ 300 min (Fig. 2). After full adjustment for covariates, compared to those reporting < 150 min of weekly LTPA, participants engaging in 150–299 min had a 9% lower odds of CVD [OR: 0.91 (95% CI: 0.77–0.98)], and those with ≥ 300 min had a 30% lower odds [OR: 0.70 (95% CI: 0.60–0.80)]. A similar pattern was observed for TPA: participants with 150–299 min and ≥ 300 min per week had 39% [OR: 0.61 (95% CI: 0.45–0.81)] and 41% [OR: 0.59 (95% CI: 0.47–0.74)] lower odds of CVD, respectively, compared to those with < 150 min. In contrast, OPA was not significantly associated with lower CVD risk in any duration category.

Figure 3 presents subgroup analyses and interaction tests for the association between LTPA and CVD by age, sex, PIR, marital status, and education. An inverse association between ≥ 150 min of LTPA and CVD was observed in most subgroups, although it was not statistically significant among participants who were married or living with a partner, and among those with PIR < 1 or PIR ≥ 4. A statistically significant interaction was observed only for marital status, indicating that the association between LTPA and CVD differed by marital status, whereas no significant effect modification was found for the other sociodemographic factors. Similarly, Fig. 4 shows subgroup analyses for TPA, where the interaction tests were not significant. The significantly inverse association between ≥ 150 min of TPA and CVD was consistent across all subgroups except those who had never been married.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, we found that meeting the minimum recommended level of physical activity (≥ 150 min per week) through LTPA or TPA was significantly associated with lower odds of CVD, compared to individuals who did not meet the guidelines. Moreover, a clear dose-response relationship was observed: those engaging in ≥ 300 min per week, double the current recommendation, experienced greater reductions in CVD risk. These findings suggest that not only meeting but exceeding physical activity recommendations may confer additional cardiovascular benefits. In contrast, OPA showed no significant association with CVD risk across different duration categories, reinforcing the idea that the health effects of physical activity vary by context.

Our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that the health benefits of physical activity are domain-specific. LTPA, which is typically voluntary, structured, and includes adequate rest, has been consistently linked to a wide range of positive health outcomes. For example, a prospective study from Finland found that individuals engaging in high levels of vigorous LTPA (> 3 h per week) had a reduced risk of all stroke subtypes compared to those who were inactive20. This finding is supported by another study showing that higher LTPA levels are inversely associated with the risk of transient ischemic attack21. A meta-analysis further reported that greater participation in LTPA is associated with a 23% lower risk of stroke, a 27% lower risk of heart failure, and an 18% lower risk of myocardial infarction22.

The benefits of LTPA extend beyond cardiovascular health. A large cohort study found that higher levels of LTPA were associated with reduced risks for 13 different types of cancer, including a 42% lower risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and a 10% lower risk of breast cancer23. In mental health, a cross-sectional study from China reported that individuals with higher LTPA levels had a 21% lower likelihood of experiencing depression24. Likewise, a U.S.-based cross-sectional study found that greater engagement in LTPA was associated with healthier blood cholesterol profiles25. Additionally, another study reported that individuals who engaged in moderate levels of vigorous LTPA (more than 4 h of physical activity per week) had a 33% lower risk of developing diabetes, while those with high levels of vigorous LTPA (> 3 h per week) had a 39% lower risk, compared to inactive individuals26.

Similarly, TPA, often achieved through walking or cycling for commuting, has been shown to offer health benefits, likely due to its moderate intensity and regular nature. A study using NHANES 2007–2010 data examined the association between TPA and health outcomes, finding that compared to individuals without TPA, those engaging in low (1–149 min) and high (≥ 150 min) levels of TPA had lower BMI and waist circumference27. Additionally, high TPA (≥ 150 min) was associated with a 31% reduced risk of hypertension and diabetes27. Another study also found that higher levels of TPA were linked to an 18% lower odds of myocardial infarction22. In line with these findings, our study identified a dose-response relationship between TPA and CVD, with greater weekly engagement in TPA corresponding to progressively lower odds of CVD.

Conversely, no significant cardiovascular benefits were observed for OPA, even at higher levels of activity. This finding aligns with the so-called “physical activity paradox”, which suggests that physical exertion performed as part of one’s occupation may not confer the same health benefits as leisure-time activity and may even be detrimental28. OPA often involves repetitive tasks, prolonged standing, physical strain, and limited recovery time, all of which can contribute to physiological stress rather than protection29. For instance, a study among Danish workers found that men in the highest quartile of OPA had a 79% increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to those in the lowest quartile30. Another study, also conducted in Denmark, objectively assessed OPA and LTPA in blue-collar workers and used heart rate monitors to evaluate heart rate and heart rate variability during sleep as markers of autonomic regulation. The results showed that both higher OPA and LTPA were inversely associated with autonomic regulation during sleep, and that the beneficial effects of LTPA were diminished in workers with high levels of OPA, suggesting that occupational strain may counteract the positive impact of recreational physical activity31,32. Consistent with this, our joint analysis revealed that only individuals with high LTPA and low OPA experienced a significantly lower risk of CVD, while high OPA alone or in combination with high LTPA was not associated with a significant risk reduction. A similar pattern emerged in the joint analysis of TPA and OPA, where cardiovascular benefits were observed only among those with high TPA and low OPA. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that OPA may not only lack cardiovascular benefit but may also attenuate the protective effects of other forms of physical activity.

Another interesting finding is that the association between LTPA and CVD varied significantly by marital status. Specifically, meeting the recommended ≥ 150 min per week of LTPA was significantly associated with a lower risk of CVD among individuals who were widowed, divorced, separated, or never married, but not among those who were married or partnered. One possible explanation is that married or partnered individuals may already experience a lower baseline CVD risk due to protective factors such as emotional support and healthier lifestyles33, which could attenuate the additional benefits of LTPA in this group. In contrast, individuals who are unmarried, separated, or widowed may lack these protective social and behavioral factors33, making physical activity a more prominent and independent contributor to cardiovascular health. Additionally, studies have shown that couples tend to exhibit similar cardiovascular risk profiles, especially in diet and exercise habits, making it harder to isolate the specific impact of LTPA among married or partnered individuals34. Relationship quality may also play a role, those in strained partnerships may experience stress-related CVD risk, potentially offsetting the benefits of LTPA35.

Moreover, in this study, CVD encompasses five diseases (angina, heart attack, stroke, congestive heart failure, and chronic heart disease), which, while having distinct pathophysiologies, share common risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, that are closely linked to physical inactivity, as well as similar clinical outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality36. Given these shared characteristics, we grouped them under a single CVD category to increase statistical power and provide a broader understanding of the relationship between physical activity and CVD risk. While this approach enhances power, it may obscure important differences between the pathologies, potentially leading to an oversimplification of the associations observed. Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting our findings, as the results may not fully reflect the nuances of each individual pathology within the CVD spectrum.

Our study offers several strengths, including the use of a large, diverse, and nationally representative sample, detailed assessment of physical activity across domains, and extensive adjustment for potential confounding factors. By examining LTPA, OPA, and TPA separately, we provide more nuanced insights into how physical activity context may shape its health effects, information that could help refine public health recommendations.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and reverse causality cannot be ruled out. Individuals with pre-existing CVD may reduce their overall physical activity, including both LTPA and TPA, due to health-related limitations or concerns about exacerbating their condition. However, OPA may be less affected, as it is primarily influenced by the physical demands of their occupation, which may not be easily adjusted based on personal choice. It is also possible that higher levels of OPA could initially be associated with higher CVD risk. Yet, due to reverse causality, individuals with CVD might eventually reduce their OPA as their condition progresses, which could explain the lack of a significant relationship observed in our study.

Second, all physical activity measures and CVD diagnoses were self-reported, which may introduce recall or misclassification bias. These biases may differentially affect the three domains: OPA is likely more accurately reported due to its structured nature37, while LTPA may be overestimated due to recall or social desirability bias38 and TPA may vary depending on daily routine and reporting accuracy39. Third, we did not capture the intensity, context, or continuity of physical activity, nor did we assess occupational stress, all of which may further influence the observed associations. Lastly, although we adjusted for many potential confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured factors cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

This study shows that meeting or exceeding the recommended levels of LTPA and TPA is associated with a lower risk of CVD among U.S. adults, with even greater benefits observed at higher levels of activity. Promoting active transportation (e.g., walking or cycling) and encouraging regular participation in LTPA could be effective strategies to reduce CVD risk. In contrast, no significant association was found for OPA, which may not confer cardiovascular benefits due to its repetitive, static, or time-pressured nature. To mitigate CVD risk in high-OPA workers, incorporating regular breaks, task variation, and ergonomic support should be considered.

Data availability

The data used in this study are publicly available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) at [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html](https:/www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html) (accessed on May 1, 2025).

References

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021 (2020).

2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. In Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018).

Nystoriak, M. A. & Bhatnagar, A. Cardiovascular effects and benefits of exercise. Front Cardiovasc. Med 5, 1425 (2018).

Lian, Y. & Luo, P. Association between various physical activity domains and overall cancer risk, National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2007–2018. PLoS One. 19, e0308099 (2024).

Fong, J. H. Leisure-time physical activity and its correlates in a multi-ethnic sample of adults over age 50 in Singapore. BMC Public. Health. 21, 379 (2021).

Scarabottolo, C. C. et al. Analysis of different domains of physical activity with health-related quality of life in adults: 2-year cohort. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 20, 71 (2022).

Holtermann, A. et al. Self-reported occupational physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: importance for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 42, 291–298 (2016).

Evans, J. T., Phan, H., Buscot, M. J., Gall, S. & Cleland, V. Correlates and determinants of transport-related physical activity among adults: an interdisciplinary systematic review. BMC Public. Health. 22, 1519 (2022).

Yao, K. Association between domain-specific physical activity and triglycerideglucose (TyG) index among US adults: evidence from NHANES 2007–2018. BMC Public. Health. 25, 159 (2025).

Steinbrink, G. M., Martinez, J., Swartz, A. M., Cho, C. C. & Strath, S. J. Is all physical activity equal? Investigating the total and domain-specific relationships between physical activity and cardiometabolic health in U.S. Adults (NHANES 2013–2018). BMC Public. Health. 24, 3363 (2024).

Holtermann, A., Krause, N., van der Beek, A. J. & Straker, L. The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 149–150 (2018).

Quinn, T. D. et al. Occupational physical activity and cardiovascular disease in the united States. Occup. Environ. Med. 78, 724–730 (2021).

Van’t Hof, J. R. et al. Association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with sociodemographic characteristics and health beliefs among a Community-Based sample of African American adults in Minnesota. Mayo Clin. Proc. 97, 46–56 (2022).

Pharr, J. R., Lough, N. L. & Terencio, A. M. Sociodemographic determinants of physical activity and sport participation among women in the united States. Sports 8, 96 (2020).

Rey Lopez, J. P., Sabag, A., Martinez Juan, M., Rezende, L. F. M. & Pastor-Valero, M. Do vigorous-intensity and moderate-intensity physical activities reduce mortality to the same extent? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 6, e000775 (2020).

Bull, F. C. et al. World health organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451 (2020).

Odutayo, A. et al. Income disparities in absolute cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular risk factors in the united states, 1999–2014. JAMA Cardiol. 2, 782 (2017).

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (2020). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/.

Hu, G. et al. Leisure time, occupational, and commuting physical activity and the risk of stroke. Stroke 36, 1994–1999 (2005).

Hall, C. et al. Occupational and leisure-time physical activity differentially predict 6-year incidence of stroke and transient ischemic attack in women. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 45, 267–279 (2019).

Raza, W., Krachler, B., Forsberg, B. & Sommar, J. N. Health benefits of leisure time and commuting physical activity: a meta-analysis of effects on morbidity. J. Transp. Health. 18, 100873 (2020).

Moore, S. C. et al. Association of Leisure-Time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 816 (2016).

Qie, R. et al. Physical activity domains and patterns with risk of depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional study in China. J. Affect. Disord. 337, 120–127 (2023).

Lian, Y. & Luo, P. The association between different leisure-time physical activity patterns and the non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2018. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 336 (2024).

Hu, G. et al. Occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Finnish men and women. Diabetologia 46, 322–329 (2003).

Furie, G. L. & Desai, M. M. Active transportation and cardiovascular disease risk factors in U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 43, 621–628 (2012).

Temporelli, P. L. Is physical activity always good for you? The physical activity paradox. Eur. Heart J. Supplements. 23, E168–E171 (2021).

Pronk, N. Physical activity paradox: providing evidence-based guidance while closing research gaps. Br. J. Sports Med. 58, 932–933 (2024).

Holtermann, A. et al. Occupational physical activity and mortality among Danish workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 85, 305–310 (2012).

Hallman, D. M., Birk Jørgensen, M. & Holtermann, A. On the health paradox of occupational and leisure-time physical activity using objective measurements: effects on autonomic imbalance. PLoS One. 12, e0177042 (2017).

Gallagher, J. & Carr, L. J. Leisure but not occupational physical activity and sedentary behavior associated with better health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, e774–e782 (2021).

Dhindsa, D. S., Khambhati, J., Schultz, W. M., Tahhan, A. S. & Quyyumi, A. A. Marital status and outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 30, 215–220 (2020).

Shiffman, D., Louie, J. Z., Devlin, J. J., Rowland, C. M. & Mora, S. Concordance of cardiovascular risk factors and behaviors in a multiethnic US nationwide cohort of married couples and domestic partners. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2022119 (2020).

Manfredini, R., Cappadona, R., De Giorgi, A. & Fabbian, F. To marry or not. Am. J. Cardiol. 123, 1185 (2019).

Frąk, W. et al. Pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases: new insights into molecular mechanisms of atherosclerosis, arterial hypertension, and coronary artery disease. Biomedicines 10, 1938 (2022).

Ainsworth, B. E., Richardson, M. T., Jacobs, D. R., Leon, A. S. & Sternfeld, B. Accuracy of recall of occupational physical activity by questionnaire. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 52, 219–227 (1999).

Luo, J. & Lee, R. Y. W. Opposing patterns in self-reported and measured physical activity levels in middle-aged adults. Eur. J. Ageing. 19, 567–573 (2022).

Adams, E. J. et al. Reliability and validity of the transport and physical activity questionnaire (TPAQ) for assessing physical activity behaviour. PLoS One. 9, e107039 (2014).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bingwen Huang and Linlin Wang were responsible for conceptualization and methodology. Bingwen Huang, Canye Lin, and Yuhuan Feng conducted the formal analysis. Shanshan Cai and Mujuan Zhao were responsible for validation. Chaochao Hu contributed to visualization. All authors contributed to writing the original draft and reviewing/editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, and a written consent form was received from each participant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, B., Lin, C., Feng, Y. et al. Association between physical activity domains and cardiovascular diseases among US adults: evidence from NHANES 2007–2020. Sci Rep 15, 35341 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19419-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19419-3