Abstract

Salinity is one of the major abiotic stresses affecting the growth and yield of wheat crops, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions, where irrigation water or soil with high salt content is often present. With increasing soil salinization and abrupt climate change at the global level, identifying salt-tolerant wheat genotypes has become crucial. The present study aimed to characterize and screen the salt tolerance of 25 wheat genotypes at 25, 52, 69, 90, and 118 Days After Sowing (DAS), under field conditions using thermography and bio-physiological parameters. Wheat genotypes were irrigated with saline irrigation water (with threshold EC of 4dSm/m) and performances of the genotypes were monitored using thermal image-based indices e.g., CWSI (Crop Water Stress Index), IG (index of Stomatal Conductance) and bio-physiological parameters i.e., Photosynthesis (Pn), Stomatal conductance (Ig), Transpiration rate, Leaf Area Index (LAI), Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), Relative water content (RWC), Total leaf chlorophyll, Membrane stability index (MSI), Osmotic pressure (OP) of leaf, Leaf Na and K. With these biophysical parameters, a new screening index named as Normalized Salinity Stress Tolerance Index (NSSTI) was developed using different multivariate analysis e.g., Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and Discriminant Analysis (DA). Based on the criteria developed in this study, NSSTI could classify the 25 wheat genotypes for salinity stress into: 6 - tolerant, 16 – moderate, and 3 – sensitive genotypes. DA confirmed the classification by NSSTI with 92–100% accuracy based on canonical discriminant functions. Further, thermal image-derived CWSI and IG differentiated tolerant and sensitive genotypes across all DAS under salt stress conditions. Irrespective of different DAS, NSSTI showed significant (p < 0.01) correlation with CWSI (0.70–0.83) and IG (0.78–0.84). The study also identified transpiration rate, RWC, OP, NDVI, and Pn as important parameters to characterize and screen wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions at different DAS. The newly developed index - NSSTI, exhibited significant (p < 0.01) correlations with wheat yield (0.76–0.84) and biomass (0.73–0.82), indicating the usefulness of NSSTI in evaluating and screening wheat genotypes for salt tolerance. The identified wheat genotypes and key bio-physiological traits can be used in breeding programs to develop advanced salt-tolerant wheat lines. In future, the newly developed salinity stress index NSSTI would play a potential role in the screening and selection of salt-tolerant wheat genotypes under field conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is the second most widely cultivated (2000 m ha) staple food crop that feeds more than 21% of the overall population worldwide. The total wheat produced during 2023–2024 was 784.91 million metric tons in USA1and 1132.92 million tons in India2. The projected growth rate of the population necessitates substantial improvement in wheat production due to the escalating effects of climate change. Salinity is a key abiotic stress that globally affects the crop growth and production of wheat3. Worldwide, about 800 million hectares of cultivable crop land are salt-affected4. They predominantly fall in arid or semiarid provinces, which receive low precipitation, with high evaporation, a poor drainage system, and irrigation practices. Hence, these regions are compelled to use saline irrigation water. In addition, rising water tables also lead to the problem of salinity3,5. Under such environments, plants experience high osmotic stress, further complications like nutrient uptake, and specific ion toxicity, in return, plummets cell turgor and prevents crop growth and productivity4,5,6. Wheat is only moderately tolerant to salinity; the loss in its grain yield exceeds 60% under saline conditions7. Therefore, development/identification of salt stress-tolerant wheat genotypes having the ability to adapt to salt stress is one of the most operative methods to deal with this7. Nonetheless, for a long time, only a limited wheat genotypes with salt tolerance abilities have been extensively used in breeding for developing salt-tolerant genotypes5,8. Hence, there is a need to identify new salt-tolerant germplasms to widen the gene base and to deliver elite resources with broadly adapted genetic backgrounds.

In general, salt-tolerance can be considered as the capability of the genotype to produce acceptable grain yield by completing its life cycle under salinity stress conditions compared to salt-sensitive genotypes8. High concentration of salt in the rhizosphere disturbs the capability of plants to uptake water, which could result in nutritional imbalances and other physiological hindrances9and ultimately reduce the crop growth and yield8. Final yield and biomass have long been considered as the simplest techniques for identifying salt-tolerant genotypes. However, as the salinity tolerance is a complex biological process, consideration of additional valuable physiological parameters would help in better identification of salt tolerance4. Furthermore, salt-tolerance of the crop is growth stage-specific, and the sensitivity of the physiological parameters to salinity stress changes at different crop growth stages10. This creates difficulty in the selection of salt-tolerant indicators and significantly lowers the selection efficiency4,10. Therefore, identification of suitable screening index/criteria using biophysical parameters is essential in identifying resistant wheat genotypes that could be combined into breeding programs for salt-tolerance9.

Several screening indicators for salinity/abiotic stress tolerance have been investigated in different studies. These include plant phenotypic characteristics under salt stress condition of wheat3, germination rate and leaf or root enlargement patterns in Brassica napus under salinity stress11, K+/Na + ratio in wheat under salinity- stress condition7, stomatal conductance12, dry weight of root/shoot and other attributes4, transpiration rate in wheat9, chlorophyll fluorescence13, yield and biomass related attributes5 etc. Additionally, the photosynthetic rate of the leaf blade was found to be a good indicator for characterizing the salt stress in rice12,14. Assessment of salinity stress tolerance in wheat using Stress Tolerance Index (STI) based on relative biomass and yield showed significant variation among the wheat genotypes under non-stress or stress conditions15. For evaluating the salinity stress tolerance in wheat, methods like the subsurface water retention technique (SWRT) by combining a set of suitable bio-physical parameters9; membership function technique by combining the germination rate, length and fresh weight of root and shoot11for identifying salinity tolerance in Indian mustard (B. napus). Similarly, multidimensional screening of wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions was done by using morpho-physiological indices using membership function value and PCA across germination, vegetative, and reproductive stages, both under glasshouse and field conditions13. PCA-based multivariate approaches and agronomic and biochemical parameters were applied to assess salinity tolerance in wheat16. Tolerant/sensitive wheat genotypes were identified using salt tolerance indices (STI), based on Mean productivity and Geometric mean productivity of wheat. It was observed that tolerant genotypes showed a good adaptive response to salinity stress despite low yield per plant, highlighting the significant relationship between grain yield per plant and biochemical parameters. Similarly, wheat lines irrigated with saline water were classified into four groups, i.e., highly tolerant to highly sensitive, based on the yield index variability of wheat genotypes using hierarchical clustering5. The tolerant lines identified were further advanced under salinity stress for identifying salt-tolerant breeding lines. In a hydroponics experiment, using saline nutritional culture, genetic variation in salinity tolerance of wheat genotypes was studied at the seedling stage17. The study used different multivariate analyses, and the results revealed significant variations in plant morpho-physiological parameters, e.g., root weight, shoot length, fresh shoot weight, total plant length, etc., according to the levels of salt stress in different wheat genotypes under a hydroponics system. In general, most of the studies either lacked in comprehensive stage-wise evaluation of wheat genotypes or experiments were not conducted under natural field conditions, which further limited the validation and applicability of the results. Additionally, very few studies only developed or validated robust, criteria-based screening indices for evaluating salt tolerance in wheat genotypes under field conditions.

In particular, previous studies have seldom used biophysical characteristics along with non-destructive thermal image-based indices for assessing the salt tolerance of the wheat genotypes. Under the restricted water supply condition, resulting from elevated salinity levels in the root rhizosphere, crop plants experience physiological drought stress which lead to partial or complete stomatal closure. In general, stomatal closure, transpiration rate, and canopy temperature are interrelated under salinity stress18. When stomata close, the canopy surface temperature increases as evaporative cooling decreases by transpiration process19. Regulation of stomatal activities as well as maintenance of transpiration rate under salinity stress condition varies according to the tolerance level of different wheat genotypes. Therefore, determination of canopy temperature is a valuable non-destructive parameter for monitoring the crop health under abiotic stress condition. This can be effectively done through thermal imaging using thermal camera and further by thermal image-based indices12,20,21. In general, wheat genotypes have various constraints in producing satisfactory grain yield under salinity stress condition6. Thus, the thermal and RGB image-based indices have the potential to characterize salt stress tolerance in wheat18. Different bio-physical parameters of wheat genotypes, grown using saline irrigation water, could be characterized using thermal infrared and RGB images indices with artificial neural networks (ANNs)18. Canopy temperature-based indices showed good and significant correlation with RWC, Chlorophyll content etc18. Salinity stress produce a wide range of variation in canopy temperature and thermal image-based indices e.g., CWSI and IG among the wheat genotypes, hence thermal imaging techniques were used to differentiate salt stress tolerant and sensitive wheat genotypes22. In other studies, combination of multivariate analysis and thermal imaging techniques were explored by incorporating the crop biophysical parameters for identifying drought tolerance in lentil19, water stress tolerance in wheat23, screening growth stages in tomato24. These studies reported that the thermal image-based indices could play a crucial role in characterizing and screening crop genotypes under abiotic stress condition and showed good agreement with the changes in crop yield and biomass. However, limited studies were found that used thermal image based technique in characterizing and screening wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition at different crop growth stages.

Despite intensive efforts, the approaches for screening wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions using multiple biophysical, agronomic, and imaging characteristics are essential to develop precise criteria that can combine the effects of crop growth stage on salinity stress tolerance. The lack of this understanding is among the foremost reasons for the partial success in breeding salt-tolerant wheat genotypes25. Considering all the preceding information, we believe that a combination of thermography and multivariate analysis could integrate the scoring of multiple biophysical traits at different crop developmental stages that could contribute to the effective evaluation of salt tolerance among the different wheat genotypes. Hence, a comprehensive study for screening wheat genotypes at various crop development stages under salt stress conditions using effective bio-physical parameters, yield attributes, thermal image-based indices, and multivariate techniques will add more understanding to the crop improvement and breeding for salt stress tolerance in wheat. Thus the present study was conducted with the following objectives: (1) to study the effect of salinity stress on wheat genotypes at different days after sowing (DAS) by monitoring biophysical parameters, (2) to develop a new screening index i.e., Normalized Salinity Stress tolerance Index (NSSTI) using multivariate techniques for identifying the tolerance of wheat genotypes to salt stress at different DAS, (3) to explore the relationship between the newly developed screening index with thermal image based indices, crop yield and biomass in different wheat genotypes at different DAS under salt stress condition.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

The study was conducted at the experimental farm of the ICAR-Central Soil Salinity Research Institute (CSSRI), Haryana, located at 29°19’7.09” − 29°19’10.0” N in latitude, 76°47’30.011” − 76°48’0.0” E in longitude with an altitude of 231 m above the mean sea level. The climate of the study area is semi-arid to sub-tropical in nature and blessed with monsoonal rainfall with an annual average of 678 mm. The major portion (nearly 81%) of the total yearly rainfall is received from July to October, while the remaining (19%) is received during January to March. The average ambient maximum and minimum temperatures hover around 37.9 °C and 6.2 °C, respectively. The ancient information of the location exhibited extreme salinity/alkalinity levels and unusable quality of groundwater, curbing agrarian activity in the study region.

Experimental details

Field experiments were conducted during the Rabi season (November to March) for two years with 25 wheat genotypes (Table 1), varying in their tolerance to salinity stress, and cultivated in different wheat growing regions of India. All the wheat genotypes used in this study are in a long-term experimental trial to understand their ability to tolerate salinity stress. The crop was sown during mid-week of November during both the experimental years in three replications. The vast area of the region has saline groundwater, where farmers generally take wheat as a staple crop for the winter season. Since groundwater is the major source for irrigation, crop generally suffers from yield loss due to salinity. The area has the water table depth at 15 m, with the groundwater having neutral pH (7.7), and high EC (< 4 to > 13 dS m−1), indicating high salinity with prevalence of Na, Ca, Mg, Cl, SO4, and HCO3 in ionic form. Due to saline groundwater, the soil in the experimental site has higher salinity levels. Such water is used in a cyclic mode with good quality water, preferably to raise salinity-tolerant crops and forestry/fruit plantations. To assess salinity stress of wheat genotypes, and to identify tolerant wheat genotype through newly developed index, saline irrigation water (with EC- 4dSm/m) was mixed with good quality water and then applied to all the wheat genotypes under field condition as the threshold level of salinity tolerance of wheat is 4–6 dSm/m,. Additionally, for proper crop growth, the recommended N, P2O5, and K2O were applied at the rate of 150, 60, and 40 kg ha−1 in the form of Urea, Single Super Phosphate (SSP), and Muriate of Potash (MOP), respectively. Based on the common recommendations, fertilizers were applied in split doses, ensuring adequate nutrient availability throughout the crop growing period.

Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH

To assess the degree of soil salinity of the experimental site, soil EC and pH were measured at 15, 30, and 60 cm soil depth on 20, 60, and 90 DAS using a soil EC meter (Model: LMCM 20) and a pH meter (Model: 10PHM01) following the standard practices.

Biophysical parameters

During the study period, the performances of the wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions were assessed using different biophysical parameters listed in Table 2. All these biophysical parameters have a direct relationship with crop health and indicate crop performance/status under abiotic stress conditions. Standard procedures were followed for collecting all the biophysical parameters as mentioned in Table 2. Except for yield and biomass, all the other bio-physical observations were taken periodically on 25, 52, 69, 90, and 118 DAS during the crop growing period for the two experimental years. Plant physiological parameters like photosynthesis, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance were measured from the fully expanded topmost leaves of each of the wheat genotypes. LAI and NDVI were measured for the whole canopy. Total yield and crop biomass were obtained at the time of harvest from the whole plot. For measuring RWC, total chlorophyll, MSI, osmotic pressure of the leaf, leaf Na and K, destructive samplings were done from each of the wheat genotypes. Simultaneously, the canopy temperature of wheat genotypes was measured using a thermal imaging camera. Different biophysical parameters recorded in this study were taken in three replications for each observation at each DAS so that a statistically adequate number of observations could be collected. Care was taken to collect the samples from plants having uniform crop age and development, and healthy and disease-free plants were maintained to reduce the variability due to stress other than salinity. A flow chart that outlines the work conducted in this study is given in Fig. 1.

Canopy temperature

The thermal images of the wheat canopy were obtained using a handheld thermal camera (Testo 890–1, Testo SE & Co., Germany). The camera is associated with a high-quality wide-angle lens of 42° × 32° and a focal plane array detector with a pixel resolution of 640 × 48020,27. For accurate measurement of the canopy temperature, an emissivity value of 0.95 was set before taking the thermal images of wheat genotypes. In general, thermal images are influenced by high wind speed, relative humidity (RH), air temperature, and solar brightness34,35. Hence, to minimize these effects, thermal images were obtained regularly during bright luminous days, under low windy conditions, preferably between 13.30 and 14.30 h from the nadir view angle. For better interpretation, images were taken from four different locations in each plot.

Thermal image-based stress indices

To understand the status of wheat crop grown under salinity stress conditions, different canopy temperature-based stress indices, e.g., Crop Water Stress Index (CWSI), Thermal index related to stomatal conductance (IG)34,35were calculated using thermal image data as mentioned below:

Where, Tcanopy is the wheat canopy temperature, Twet is the wet leaf temperature covered with water, and Tdry is the dry leaf temperature coated with petroleum gel. Twet and Tdry simulates minimum and maximum leaf transpiration, indicating minimum and maximum canopy temperature boundary under the present open environmental condition36. Normally, the stress indices CWSI are positively related to the crop water stress condition2,3,36whereas IG is inversely related to the stomatal conductance. Representative salinity stress maps of wheat genotypes were also prepared for understanding the spatial variation of salinity stress with inverse distance weighting methodology using ArcGIS.

Parameter normalization & hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA)

Cluster analysis can group dependent variables with similar expression. In this study, HCA was performed using the normalized value of all biophysical parameters of 25 wheat genotypes (as listed in Table 1) grown under salinity stress conditions. Ward’s method of HCA, which works on the principles of Euclidean distance, was used to group the wheat genotypes. The clusters indicate how similar wheat genotypes can be grouped based on their ability to tolerate salinity stress. Before HCA, all the biophysical parameters were normalized using the following formula37:

where the observed values refer to the individual biophysical parameters measured for each genotype, while the minimum and maximum values represent the lowest and highest values, respectively, for each parameter within the corresponding wheat genotype.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and development of a new screening index

PCA is a numerical process that alters several correlated variables into uncorrelated variables37. From PCA, principal components (PCs) were obtained, which were the linear combination of variables that elucidate the largest variance existing in the dataset. PCs are the vectors that represent the best fit of the n observations in p-dimensional space, right-handed to each other23. Normalized biophysical parameters of all the wheat genotypes at different DAS were used to develop a new screening index for evaluating wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions using PCA. To assess the salinity stress tolerance of each genotype, a screening index—termed the Normalized Salinity Stress Tolerance Index (NSSTI)—was developed using a weighted linear combination of normalized biophysical parameters, as defined by the formula given below:

where, Wi is the normalized weight of the ith crop biophysical parameters (derived from PCA communality report), and Xi is the normalized mean value of the ith biophysical parameter in the analogous genotypes.

NSSTI was calculated at different DAS and based on the above calculation, genotypes were identified as tolerant (with NSSTI score > NSSTIavg +SD), moderate (with NSSTIavg +SD > NSSTI score > NSSTIavg - SD), and sensitive (with NSSTI score < NSSTIavg -SD) to salinity stress for that particular stages. Thus, NSSTIavg ± SD indicates upper and lower thresholds for a particular DAS for the 25 wheat genotypes considered in this study.

PCA also identified the most sensitive crop parameters based on their loading values in each principal component (PC), which significantly contributed to explain the variance and in screening the wheat genotypes under salinity stress at each DAS. PCs with eigenvalue ≥ 1 were selected in this study37. Normally, the first PC covers most of the variability present in the data set by showing the highest percentage of variance value. Within each PC, biophysical parameters having values within 20% of the highest loading factor were selected as the most significant or representative parameter for that particular PC. Parameters with the highest factor loading values and strong, statistically significant correlation coefficients were considered representative and selected for further analysis.

Discriminant analysis (DA) of wheat genotypes

DA is a statistical approach that could classify a set of observations into predefined categories38. In this study, DA was used in categorizing wheat genotypes into different classes based on the discriminating function that provides the maximum separation among the classes. The analysis was done in SPSS v 15 using different biophysical parameters from 25 wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress conditions. Additionally, DA also discloses the important biophysical parameters that perform significantly in separating the wheat genotypes into different classes.

Statistical analysis of data

To evaluate the natural response of 25 wheat genotypes to salinity stress over two cropping seasons, the study was conducted under field conditions. Where all the genotypes were sown each year under uniform salinity stress conditions in the same saline field. Data collection of biophysical parameters was done at five stages (25, 52, 69, 90, and 118 DAS) across both years; and measurements were taken in three replications across two seasons. To assess the significant effects and interactions of the three factors, e.g., genotype (G), Year (Y), and days after sowing (time-D), we employed a three-way ANOVA. This permitted us to analyze main effects (G, Y and D); two-way interactions (G x Y, G x D and Y x D); and three-way interaction (G x Y x D). Thus, enabling a comprehensive understanding of genotypes’ performances, varied over time, and between years, under salinity stress conditions. We acknowledge that this was a field-based observational study rather than a formal designed experiment. However, the structured data obtained through genotypes, time, and years explained the use of three-way ANOVA, which is frequently used to analyze such multi-factorial observational datasets to assess significance and interaction effects. The analysis used a mixed-model framework where G and time-D were treated as fixed effects, and year-Y and replications nested within year were treated as random effects. The model was fitted using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) approach implemented via the lmer() function from the lme4 package in R v4.4.3 (R Core Team, 2025). Significance of fixed effects and their interactions was assessed using Type III F-tests with Satterthwaite’s approximation for degrees of freedom, using the lmerTest package. Homogeneity of variances and normality of residuals were checked through residual diagnostic plots. The analyses were performed in R Studio (v4.4.3). Significance in response of different biophysical parameters for all the wheat genotypes was calculated for different days of observation (25, 52, 69, 90, and 118 DAS) for the two study years. Additionally, PCA and discriminant analysis (DA) were carried out using R software (R Core Team, 2025) and SPSS v 15. Thermal image analysis and spatial maps were prepared using IRSoft and ENVI 4.8 software.

Result

Chemical properties of the location (EC and pH content)

Variations in electrical conductivity (EC) at different soil depths (0 to 60 cm) from 22 to 110 DAS for the two study years (Fig. 2a, b, c, and d) showed significant changes. Irrespective of different years, EC was observed to be 18.97–22.96 dSm–1 at the surface soil, while slightly high EC, e.g., 26.70–30.39 dSm−1, was found at 30–60 cm soil depth (Fig. 2a, b). However, EC was around 26.94 dSm−1 within 15–30 cm soil depth. Similarly, soil pH at different soil depths over different days of observations was observed to be in the alkaline range (pH > 7.0). Within surface soil (0–15 cm), pH was around 8.19, while at the deeper layer (30–60 cm), a slightly high average pH of 8.39 was observed (Fig. 2c, d) in the experimental site.

Variations of biophysical parameters of wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions

Salinity stress at different DAS showed a significant effect (p < 0.05) on different biophysical parameters of different wheat genotypes, however, the year of the experiment was not found to be significant for each of the biophysical parameters studied in this experiment (Table 3). The interaction among the genotypes and DAS (G × DAS) was highly significant (p < 0.0001) for different biophysical parameters calculated in this study. As the effect of the experimental

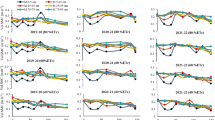

year (Y), as well as their interaction (Y × DAS, and Y × DAS × G), was non-significant; we have used the pooled values of the two consecutive years for further analysis. Pooled values of mean biophysical parameters (LAI, stomatal conductance, osmotic pressure, RWC, leaf Na content) of all the 25 wheat genotypes for the two experimental years, at 25, 52, 69, 90, and 118 DAS showed significant variations (p < 0.05) (Figs. 3 and 4). Irrespective of wheat genotypes, LAI, an important indicator of leaf area growth, was the highest during 69–90 DAS (Fig. 3a). At 69 and 90 DAS, the highest LAI was observed in genotypes ASN_SAN_17 (3.62) and ASN_SAN_06 (3.65) while DBW-246-1 and KRL-283/BH 1146 showed the lowest LAI. However, genotypes KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99 also showed good LAI growth during 69–90 DAS.

In general, NDVI, an indicator of vegetation health, calculated based on the canopy reflectance in Red and Near Infra-Red bands, is > 0.5 for healthy vegetation. In this study, NDVI showed significant (p < 0.05) variation during different days of observation among the wheat genotypes. In this study, the highest NDVI values were observed during the peak vegetative stage to flowering stages in genotypes ASN_CHECK_3 and ASN_CHECK_4, while the lowest values were found in genotypes KRS-1319, KRL-283/BH 1146, and KRL-414 at 52, 69, and 90 DAS, respectively (Fig. 3b). Leaf photosynthesis rate showed significant responses (p < 0.05) among wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress conditions throughout the study periods. Genotypes, ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_1, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_3 showed 39.4–41.4% higher photosynthesis rate (5.21–9.32 µmol CO m−2 s−1) than KRL-283/BH 1146, KRS-1411, HD-3086, KRL-283/KRL 239, KRL-342/PBW-343 (1.07–5.38 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) during 52–90 DAS (Fig. 3c). The degree of stomatal opening and closing decides the gaseous exchange and transpiration rate in crop plants; hence, both stomatal conductance and transpiration rate serve as indicators for plant water status. In the present study, stomatal conductance and transpiration rate showed significant variations (p < 0.05) at different DAS (Fig. 3d, e). In general, ASN_SAN_17 (0.275 mol H2O m−2 s−1, 5.47 mmol H2O m−2 s−1), ASN_SAN_18 (0.213 mol H2O m−2 s−1, 5.69 mmol H2O m−2 s−1) and ASN_SAN_06 (0.288 mol H2O m−2 s−1, 4.9 mmol H2O m−2 s−1) showed the highest values in both stomatal conductance and transpiration rate respectively (Fig. 3d, e) during 52 to 90 DAS respectively, while KRL-119/KRS 626, KRL-99/HD-2851, HD-3086 showed poor performances. Regarding the check genotypes, KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99 showed high values of transpiration rate and stomatal conductance, and DBW-246, KRS-9301/KRL 213, KRL-99/HD-2851, KRS-1411, KRL-283/KRL 239 showed low values (Fig. 3d, e). Osmotic pressure (OP) indicates dissolved solutes in cell sap and is proportional to solute concentration and inversely proportional to the volume of the cell water. Wheat genotype ASN-SAN-09 showed the highest values of osmotic pressure on 69, 90 and 118 DAS (999, 1023.6, 980 mmol/kg, respectively), while the lowest were observed in genotypes KRL-119/KRS 626, KRL-119/KRS 626, KRL-342/PBW-343 (Fig. 3f). Irrespective of the different days of observation, all the check genotypes showed a higher range of osmotic pressure than the other genotypes.

RWC, is an indicator of water balance (water supply to the leaf tissue and water loss via transpiration) within the leaf. RWC of leaves of different genotypes showed significant variations (p < 0.05) during the study period (Fig. 4a). Wheat genotypes ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_1, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-345/KRL 250 showed the highest values of RWC at 25, 52, 69, 90 DAS (Fig. 4a). In general, irrespective of different days of observation, genotypes KRL-283/BH 1146, KRL-99/HD-2851, KRS-1411, HD-3086, KRL-283/KRL 239, and KRL-342/PBW-343 showed 14.34% lower RWC than the check genotypes. Leaf chlorophyll content, which is a measure of greenness, showed significant variations (p < 0.05 or < 0.01) during 25 to 90 DAS. Irrespective of the genotypes, the highest values in total chlorophyll were seen during the mid-vegetative stage during both the experimental years (Fig. 4b). In general, the highest value of total chlorophyll content (5.38 mg g−1) was observed in ASN_CHECK_4 at 69 DAS, and the lowest was in KRS-1319 (0.64 mg g−1). The membrane stability index (MSI) has been widely used to evaluate abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. In this study, significant variations (p < 0.05 or 0.01) in MSI among the genotypes were seen on 25, 69, 90, and 118 DAS under salinity stress conditions (Fig. 4c). Genotype ASN_SAN_06 showed the highest value of MSI both at 25 and 90 DAS (78.51 and 64.87, respectively), and the lowest values were observed in KRS-9301/KRL 213 and KRL-342/PBW-343 (16.67 and 15.28, respectively). In general, during 69–90 DAS, all the check genotypes showed 31.96% more MSI than other genotypes. Nevertheless, irrespective of the days of observations, MSI values of genotypes e.g. KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99 were high.

Variations in mean values of biophysical parameters (a) LAI, (b) NDVI, (c) Photosynthesis rate (Pn), (d) Stomatal Conductance (Ig), (e) Transpiration rate (Trans) and (f) Osmotic pressure of 25 wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition at different days after sowing (DAS) along with significant difference among the genotypes at each DAS. (* sig at p < 0.05, ** sig at p < 0.01, *** sig at p < 0.001, ns- not significant).

Variations in mean values of biophysical parameters (a) (a) Relative water content (RWC), (b) Total chlorophyll, (c) Membrane stability index (MSI), (d) Leaf Na content, (e) Leaf K content, of 25 wheat genotypes (as given in Table 1) under salinity stress condition at different days after sowing (DAS) along with significant difference among the genotypes at each DAS. (* sig at p < 0.05, ** sig at p < 0.01, *** sig at p < 0.001, ns- not significant).

Leaf Na content varied significantly (p < 0.05 at different observations) among the genotypes under salinity stress conditions. (Fig. 4d). Genotypes KRL-119/KRS 626 and HD-3086 showed the highest value of leaf Na at 52 and 69 DAS, respectively, and genotypes ASN_SAN_06 showed the highest leaf K contents at 52 and 69 DAS, respectively. Irrespective of the genotypes, leaf K content showed comparatively high levels during 25–69 DAS and decreased thereafter under salinity stress conditions (Fig. 4f). In general, genotypes ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_1, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_18, ASN_SAN_09, ASN_CHECK_3, ASN_CHECK_2, and ASN_SAN_3 showed comparatively low values of leaf Na and high values of leaf K content under salinity stress conditions.

Hierarchical cluster analysis

The number of clusters of wheat genotypes, created on the basis of within-group similarity, was more than those created with between-group similarity. Three different clusters were obtained from Ward’s method of Hierarchical cluster analysis for the wheat genotypes considered in this study (Fig. 5a). Mean values of all biophysical parameters falling under each cluster were as given in Fig. 5b. Cluster 1, with 7 wheat genotypes (viz., KRL-345, KRL-342, KRL-414, KRL-99, DBW-246-1, KRS-9301, and KRS-1319), showed the lowest mean values of biophysical parameters, while the highest were seen among wheat genotypes falling in cluster 3 (ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_1, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_3, ASN_SAN_06) (Fig. 5a and b). Rest of the genotypes, under cluster 2, showed moderate values of mean biophysical parameters.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the biophysical parameters of wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress condition

To screen the wheat genotypes for salinity stress tolerance at different DAS based on their response in biophysical parameters, the current study developed a new screening index, i.e., NSSTI, and identified the salinity stress tolerance ability of different wheat genotypes. A summary of PCA, analyzed at different DAS using eleven different biophysical parameters obtained from 25 wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress, is given in Table 4. Eigen value > 1 was considered (Brejda et al. 2000) for selecting principal components (PCs) at different DAS. For 25 DAS, four PCs were identified, which cumulatively explained 75.83% of the total variance of the data set (Table 4). Similarly, 4 PCs for 52 DAS, 3 PCs for 69 DAS, 4 PCs for 90 DAS, and 3 PCs for 118 DAS were identified, which explained 75.11%, 70.44%, 76.54%, and 70.40% of the cumulative variance, respectively. PCA also identified important biophysical parameters that played a significant role in characterizing the salinity stress condition of wheat genotypes at different DAS. For this, within each PC, the highest factor loading value of each biophysical parameter was considered as the most important indicator for describing the salinity stress condition. Irrespective of the different DAS considered in this study, under PC1 (which explained the highest variances of the dataset), transpiration rate at 25, 52, 69 DAS, RWC at 90 DAS, and total chlorophyll content at 118 DAS were identified as the highest factor loading parameters under salinity stress conditions. Similarly, under PC2, photosynthesis rate at 25 and 69 DAS, transpiration rate at 90 DAS, osmotic pressure at 118 DAS, and NDVI at 50 DAS were identified to have the highest factor loading values. Under PC 3, RWC at 25 and 69 DAS, leaf K content at 50 DAS, stomatal conductance at 90 DAS, and MSI at 118 DAS were identified to have significance in characterizing salinity stress conditions of wheat genotypes (Table 4). PCA bi-plots (Fig. 6a, b, c, d, and e) for different DAS provide a comprehensive picture of the interrelationship between all measured parameters for evaluating salt tolerance in wheat genotypes. An acute angle among different parameters in the same direction showed a robust relationship between consistent parameters for classifying genotypes and vice versa, with the obtuse angle. A right angle shows no association among parameters, while a straight angle reproduces a negative correlation among them. Genotypes having high association for a specific parameter were plotted closer and along the vector line direction. Based on these principles, genotypes ASN_SAN_13 (G25), ASN_SAN_09 (G21), ASN_CHECK_3 (G22) and ASN_CHECK_2 (G23) associated strongly with MSI, total chlorophyll, NDVI, OP, LAI thus shows better salt tolerance with good membrane stability, higher chlorophyll and greenness at 25 DAS (Fig. 6a). While genotypes: ASN_SAN_17 (G16), ASN_SAN_3 (G24), ASN_CHECK_1 (G17), ASN_SAN_18 (G20), ASN_CHECK_4 (G19) showed strong interrelation with lead Na content, transpiration (Trans), and stomatal conductance (Ig) values at 25 DAS. Genotypes HD-3086 (G8), KRL-99/HD-2851 (G6), KRS-1411 (G7), KRL-283/KRL 239 (G9), KRL-119/KRS 626 (G11), etc., showed low performance with no strong alignment with any single trait vector except leaf K content at 25 DAS. Based on the angular relation at 25 DAS, MSI, RWC, and total chlorophyll showed an acute angle, indicating a strong positive correlation, while leaf Na and K content showed strong negative correlation with opposite angles. Thus, leaf Na content, Transpiration, and IG pointed in the same direction, indicate their potential as stress-sensitive indicators (Fig. 6a). Similarly, for 52 DAS (Fig. 6b), genotypes: ASN_SAN_18 (G20), ASN_SAN_09 (G21), ASN_CHECK_3 (G22) and ASN_CHECK_2 (G23) placed nearer to vector NDVI, LAI, total chlorophyll indicate the moderate tolerance of these genotypes with good canopy health, chlorophyll retention, and greenness. However, genotypes KRS-1319 (G15), KRL-99/HS460/KRL99 (G14), KRL-414 (G3), KRL-342/KRL 304 (G13) etc. showed low-performance under salt stress, with reduced MSI, photosynthetic efficiency and poor stress adaptation. Among the biophysical parameters, Na and K point in opposite directions (52 DAS), indicating a negative correlation, which is physiologically

precise under salt stress condition. Additionally, NDVI, OP, LAI & total chlorophyll showed acute angle indicating positive plant vigor of the associated genotypes (Fig. 6b). At 69 DAS (Fig. 6c), genotypes ASN_SAN_06 (G18), ASN_SAN_17 (G16), ASN_SAN_18 (G20), ASN_SAN_18 (G21), showed strong association with transpiration, Ig, OP, total chlorophyll, indicating higher photosynthetic and water loss traits. In general, genotypes falling in the positive coordinate of PC2 showed a more tolerant nature as compared to genotypes falling in the negative coordinate. MSI and Ig/Na showed a strong negative relationship, indicating well for identifying salt tolerance among the genotypes. Similarly, for 90 and 118 DAS (Fig. 6d and e), genotypes KRL-119/KRS 626 (G11), HD-3086 (G8), KRS-9301/KRL 213 (G4), DBW-246 (G2) etc. concentrated on the left side of the bi-plot, while, ASN_SAN_18 (G20), ASN_CHECK_4 (G19), ASN_SAN_06 (G18), ASN_CHECK_1 (G17), ASN_SAN_17 (G16) more on the right side (Fig. 6d and e) which indicates the variation in their stress tolerance under salinity stress condition.

Normalized salinity stress tolerance index (NSSTI) for screening wheat genotypes at different DAS under salinity stress conditions

Subsequently, the salinity tolerance ability of different wheat genotypes was characterized by the screening index, Normalized salinity stress tolerance index (NSSTI). The newly developed screening index, NSSTI, is a summation of normalized biophysical parameters (Xi) multiplied by the weightage (Wi) of each biophysical parameter for each genotype obtained from the PCA communality report. Table 5 shows the variation of NSSTI score of 25 wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions at 25 DAS (Supplementary file 1, for 52, 69, 90, and 118 DAS). To screen the wheat genotypes, upper (NSSTI Avg + SD) and lower (NSSTI Avg - SD) threshold values were calculated for each stage (Table 6). For 25 DAS, the upper and lower limits were observed to be

0.617 and 0.359, respectively. Thus, genotypes with NSSTI scores > 0.617 were considered tolerant and that of NSSTI < 0.359 were considered sensitive, and genotypes with score values 0.617 > NSSTI > 0.359 were considered moderately tolerant to salinity stress conditions. Accordingly, all the wheat genotypes were classified (Table 6) for different DAS with different colour notation (Red - Sensitive, Yellow- Moderate, and Green - Tolerant). At 25 DAS, wheat genotypes, ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_1, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4 and ASN_SAN_18 were identified as tolerant with NSSTI score > 0.617, however, genotypes KRL-119/KRS 626, HD-3086, KRS-9301/KRL 213 were identified as sensitive with NSSTI < 0.359. Based on their NSSTI score values, some of the genotypes consistently showed to be tolerant (ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_SAN_17) and sensitive (KRS-9301/KRL 213, HD-3086) throughout the different days of observation (Table 6). However, irrespective of different days of observation, some genotypes (i.e., ASN_SAN_3, ASN_SAN_09, ASN_CHECK_1) showed either moderate to tolerant or moderate to sensitive (DBW-246, KRL-119/KRS 626, KRL-283/KRL 239, KRL-99/HD-2851) under salinity stress conditions. Apart from these, KRL-414, KRL-283/BH 1146, KRS-1411, KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99- 99/HS460//KRL99, ASN_CHECK_3, ASN_CHECK_2, ASN_SAN_13 showed moderate sensitivity (during all the days of observations) to salinity stress condition (Table 6).

Discriminant analysis

Discriminant analysis (DA) was performed to explore the ability of biophysical parameters identified as significant through PCA at different DAS, in screening/discriminating wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions. Only significant biophysical parameters, identified under different PCs, at different DAS of wheat genotypes were used for the analysis. Irrespective of different DAS, Box’s M test of equality showed the existence of differences in the covariance matrices among the groups at p < 0.05 (Table 7). In general, based on the performances of canonical discriminant functions (Function 1 & 2), all the wheat genotypes were discriminated into three different groups (Fig. 7). Thus, these two functions could explain the total variability of the dataset. Canonical correlation (Table 7) showed multiple correlations between the biophysical traits and discriminant functions, which indicate the overall fit of the dataset. In this study, canonical correlations of 0.822–0.923 and 0.203–0.546 (Table 7) were obtained for functions 1 & 2, respectively, at different DAS. The square of the canonical correlation indicates the proportion of variance conveyed by the functions. Thus, function 1 could explain 67.56% − 85.19% of variations among the clusters (tolerant, moderate, and sensitive to salinity stress) (Fig. 7a). In the discrimination, all the biophysical parameters played a significant (p < 0.05) role as shown in the structural matrix (Table 8). Wilks’ lambda is an indicator of the efficiency of each function in separating genotypes into different clusters. Wilks’ lambda ranges from 0 to 1; the smaller the value, the better the discriminability of the variable. In this study, a smaller value of Wilks’ lambda (0.204) was observed for functions 1 through 2 (significant; p < 0.000), which represents better discrimination of wheat genotypes into different clusters (Table 7; Fig. 7). In general, chi-square statistics (Table 7) check the hypothesis that the averages of the functions are identical across groups. In this study, low chi-square values (significant, p < 0.05) were observed for functions 1 through 2 (27.25–43.48), which significantly separated wheat genotypes based on their salinity stress tolerance ability (Table 7). Eigenvalue delivers statistics on each of the discriminate. Here, the Eigenvalues for Functions 1 and 2 (Table 7) explained the variance of 83-98.4% and 1.6–17%, respectively. Centroids are the discriminant score for each group, and distinct locations of centroids show high classification accuracy. In this study (Fig. 7a, b, c, d, e), positions of the centroids of each groups (tolerant, moderate or sensitive genotypes) were discrete and well separated from one another with classification accuracy of 92.0%, 96.0%, 84.0%, 100%, and 96.0% for training data set and 76%, 88%, 76%, 96% and 84% during cross validation for 25, 52, 69, 90 and 118 DAS respectively (Fig. 7). In general, the structural matrix of DA and communality values of PCA showed similar results, emphasizing the importance of different biophysical parameters in genotypic discrimination. Additionally, results from the discriminant analysis were also supported by the results obtained from the newly developed Normalized Salinity Stress Tolerance Index (NSSTI) through PCA.

Relation between NSSTI with canopy temperature, thermal image-based indices, crop yield, and biomass

In the current study, PCA-based newly developed index, i.e., NSSTI, and discriminant analysis showed the potential to screen/discriminate wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions. Further, its relationship with thermal image-based stress indices was assessed. Irrespective of different days of observations, a canopy temperature of 11.59–26.62 °C was observed among the wheat genotypes (Fig. 8). However, the highest canopy temperature, i.e., 14.28–23.72 °C, was observed at 90 DAS among the wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions (Fig. 8). In the thermal images (stage 69 DAS), the wheat canopy showed more blue color, which signifies cooler temperature, while yellow to red colors show higher canopy temperature. Similarly, thermal image-based indices i.e., CWSI and IG showed variations at different DAS among wheat genotypes. Irrespective of different days of observations, genotypes like KRS-1411, HD-3086, KRL-283/KRL 239 and KRL-342/PBW-343 showed high values of CWSI and low IG (Fig. 9a, b). On the other hand, all the check genotypes and ASN_SAN_17, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_SAN_18, ASN_SAN_09, ASN_SAN_3, ASN_SAN_13 showed low CWSI and high IG over different DAS. At 69 DAS (Fig. 8), variation in canopy temperatures and thermal images-based indices (CWSI and IG) among tolerant, moderate, and sensitive wheat genotypes was observed under salinity stress conditions. Genotypes like KRS-9301/KRL 213, HD-3086, KRL-342/PBW-343 showed high canopy temperature (19.83, 21.18, and 19.25 °C respectively), high CWSI values (0.91, 0.96, 0.95 respectively, showing more reddish appearances in CWSI spatial map) and low values of IG (0.04, 0.05 and 0.09 respectively, showing more greenish appearances in IG spatial map) at 69 DAS than other genotypes (Fig. 8). While, genotype e.g., ASN_SAN_17, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_CHECK_3 showed much low canopy temperature (with an average of 14.46 °C), low CWSI (0.58, 0.57, 0.52, 0.53 respectively, more greenish color in spatial map) and high value of IG (more reddish color in spatial map) (Fig. 8). In general, the status and response of other wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress conditions can be assessed from the variation in canopy temperature, CWSI, and IG from Figs. 8 and 9. Further, we regressed the newly developed screening index, i.e., NSSTI, with CWSI and IG (Fig. 10a to j) at different DAS for all the wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress conditions. In general, pooled data showed significant (p < 0.05) and high R2 for NSSTI with CWSI (p < 0.001) and NSSTI with IG (p < 0.001) for all the DAS. For both the CWSI and IG, the highest R2 was obtained at 69 DAS. Under the salinity stress condition, significant variation in crop yield and final biomass was obtained among the wheat genotypes (Fig. 11a). Highest crop yield and biomass were obtained in ASN_SAN_17 (3.42 t ha−1 and 8.78 t ha−1 respectively), while the lowest were obtained in DBW-246 (1.14 t ha−1 and 3.83 t respectively) (Fig. 11a). Along with the check genotypes, other genotypes e.g., KRL-345/BH 1146, KRL-283/BH 1146, KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99 showed better yield (2.26–2.65 t ha−1) and biomass (5.97–7.24 t ha−1) under salinity stress conditions. Subsequently, significant correlations (p < 0.001) were observed between the newly developed NSSTI, with crop yield and biomass at different DAS (Fig. 11b). Among the different wheat genotypes considered in this study, the highest correlation of NSSTI with crop yield (0.846, p < 0.001) and biomass (0.823, p < 0.001) was obtained at 21 DAS. However, the correlation coefficient between the newly developed NSSTI with yield and biomass was also found to be the best at 69 DAS.

(a) Variation of crop yield and biomass of wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition. *** shows significant at p < 0.001, Upper cap indicates standard deviation of yield and biomass. (b) Pearson’s correlation between NSSTI and crop yield/biomass for all the wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress condition.

Discussion

Around 6.72 mha area in India (amounting to 2.1% of total geographical area), including 2.34 mha soils in the Indo-Gangetic plains, is salinity-affected39. Soil salinization is a global and dynamic problem and is projected to increase in future under climate change scenarios, viz., rise in sea level and impact on coastal areas, rise in temperature, and increase in evaporation, etc40.. As per the recent report41India is currently nourishing 1.4 billion population, to feed this growing population, more production in terms of staple food is expected from fixed cultivable land. To moderate this detrimental effect, and to achieve better crop yield under salinity stress conditions, identification of tolerant wheat genotypes using suitable screening techniques is the need of the hour7,42. In general, for identifying salinity stress tolerance, breeder considers the seedling stage to be the most critical stage4,7,42. Salinity tolerance is a complex biological event, governed by several physiological factors, growth stages, and genotypic traits; invariably reported to be the most sensitive at the vegetative stage or early reproductive stage43,44. Even though substantial efforts have been made in formulating screening methodologies for characterizing salinity tolerance of wheat genotypes, most of the trials were conducted either under controlled.

environments (greenhouse experiments) or through pot experiments or solution cultures as the growing media. These controlled conditions are not actual representations of a natural saline field, where the crop has to face the spatiotemporal variability of different physicochemical properties, fluctuations in salt content in the rhizosphere, variability due to macro or micro-environmental conditions, etc., at different growth stages9,45,46. Many of these multifaceted conditions confronted by the crop in the field should be considered when plant breeders try to identify the best crop biophysical parameters that can be used for developing screening criteria for salinity tolerance. Wheat is reported to be moderately tolerant to salinity conditions; the loss of grain yield goes above 60% due to unpaid attention to soil salinity9. To date, information regarding characterizing and screening of wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions under field situations at different stages (days after sowing) using different biophysical parameters and thermal imaging techniques is limited. Thus, an attempt has been made to address the majority of these factors in this study.

To assess the salinity stress tolerance abilities of wheat genotypes in different days after sowing, a new screening index, e.g., NSSTI, was developed using multivariate techniques, i.e., HCA, PCA, and DA. Results obtained from this analysis were compared with thermal-based indices like CWSI and IG along with with crop parameters like yield and biomass of different wheat genotypes grown under salinity stress conditions (Fig. 12). The methodology collectively provided a comprehensive and robust framework for evaluating and categorizing the salinity stress tolerance of wheat genotypes at different DAS. These multivariate techniques have a major advantage over univariate models in eliminating noise. The output obtained from the HCA is very easy to interpret and gives a hierarchy that provides more information on a structured cluster than an unstructured set of flat clusters as obtained from k-means clustering. Similarly, discriminant analysis, used in this study, has the potential to classify or discriminate ungrouped cases. Additionally, it also generates a bi-plot to aid better interpretation of the results. Likewise, PCA is a commanding procedure to shrink data dimensionality and help in recognizing the significant parameters from a set of variables. Formerly, efforts were made by different researchers to screen genotypes using different multivariate techniques, to characterize the heat tolerance in wheat47water stress tolerance in wheat23quality characters in barley48finding genotypic origin in coffee49salinity stress in wheat5and drought tolerance in rice genotypes50. However, characterization and screening of wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions at different DAS (analogues to different growth stages) by combining multivariate techniques and thermal imaging will be more useful in crop breeding to identify salinity-tolerant wheat genotypes. Based on the performances of wheat genotypes (as measured through biophysical parameters) under salinity stress conditions, the newly developed index NSSTI could screen wheat genotypes into tolerant (NSSTI score > Upper limit), moderately tolerant (Upper limit > NSSTI score > Lower limit) and sensitive categories (NSSTI score < Lower limit) (Table 6) at different DAS.

Under saline stress situations, crop growth and development are severely affected due to osmotic stress, resulting in water uptake owing to reduced osmotic and matric potentials of the soil7. In salinity-affected soil, Na+ at first comes into the root cells and is subsequently moved to shoots through the transpiration stream in the xylem. Thus, substantial hindrance in plant metabolic activities causes considerable variations in various agronomic and biophysical parameters at different structural levels, which are encouraged by osmotic stress and definite ion toxicities25. In this study, irrespective of genotypes, more accumulation of both Na+ and K+ in leaves was found during, 25 to 69 DAS under salinity stress conditions (Fig. 4d, e), signifying that injury had happened due to osmotic stress and ion toxicity. Among the genotypes, KRS_1319, KRL_119/KRS_626, KRL-342/PBW-343, HD-3086 showed high values of leaf Na content during 25 to 69 DAS, whereas, ASN_SAN_3, ASN_CHECK_2, ASN_CHECK_3, ASN_SAN_09, ASN_SAN_18, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_1, KRL_283/BH 1146, KRS_9301/KRL_213 showed high values of leaf K content during the same period. However, during 90 to 118 DAS, leaf Na content was found to be much less as compared to leaf K content. This might have significantly altered leaf osmotic potential, resulting in an imbalance in water uptake or leaf water content, causing remarkable fluctuations in leaf turgor pressure. This is considered to be the chief factor, along with K+, in controlling stomatal opening7,9,51. In general, stomata in the leaf surface control the exchange of CO2 and water vapor (through transpiration) within the plant system. Reduced stomatal conductance (due to less K+ in the leaf in sensitive genotypes) hampers the leaf photosynthesis and transpiration rates7,52,53. In this study, wheat genotypes, e.g., ASN_SAN_17 (25 DAS, NSSTI- Tolerant), ASN_SAN_06 (52, 69 DAS, NSSTI- Tolerant), ASN_SAN_18 (90, 118 DAS, NSSTI- Tolerant) showed high values of transpiration rate, while that of genotypes KRL-119/KRS 626 (25, 52, 69 DAS, NSSTI- Moderate), KRL-342/KRL 304 (90 DAS, NSSTI- Moderate), KRL-345/BH 1146 (118 DAS, NSSTI- Moderate) showed low values. Similarly, wheat genotypes viz. ASN_SAN_17 (25, 118 DAS, NSSTI- tolerant), ASN_SAN_06 (52, 69 DAS, NSSTI- tolerant), ASN_CHECK_4 (90 DAS, NSSTI- tolerant) showed high stomatal conductance, while, low value was observed in KRL-119/KRS 626 (25, 52, 69 DAS, NSSTI- sensitive to moderate), HD-3086 (69 DAS, NSSTI- sensitive), KRL-99/HD-2851 (118 DAS, NSSTI- moderate). Compared to sensitive genotypes, tolerant genotypes showed lower leaf osmotic pressure, which indicates better osmotic adjustment capability of salinity-tolerant genotypes. In general, accumulation of toxic ions in the leaves and alteration in stomatal activity resulted in similar patterns with lower photosynthesis rate and RWC in sensitive than tolerant genotypes, as reported in previous studies7,9,54. Although osmotic stress inhibits growth and development of both tolerant and sensitive genotypes, the results from the present study suggest that the salinity-tolerant genotypes might possess a more efficient salinity tolerance mechanism than the salinity-sensitive genotypes, which would protect the crop from osmotic injury and the ion toxicity effects of salinity stress7,9. Because of these interconnected processes, most parameters associated with leaf water relations and photosynthesis have been regularly and successfully used as screening standards for assessing salinity tolerance in several crops like wheat9 barley and fabaean52chickpea55rice56quinoa57brassica11sunflower58and cotton54. Reduction in leaf photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate in sensitive wheat genotypes as compared to tolerant wheat genotypes was found under salinity stress conditions in field experiment6. Likewise, the current study identified transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, photosynthesis rate, RWC, and stomatal conductance, etc. as the important parameters under different PCs (Table 4) at different DAS using PCA. Subsequently, the identified parameters further discriminated wheat genotypes using discriminant analysis. Na+ exclusion from the shoot and K+ retention in the mesophyll cell are the major reasons for justifying the salinity tolerance mechanism within the crop plants4,7. Cell membrane stability is another indicator (MSI) that contributes to salinity tolerance. In the current study, tolerant wheat genotypes, viz. ASN_SAN_17, ASN_CHECK_4, KRL_345/KRL 250, ASN_CHECK_2, ASN_SAN_06, showed high MSI than sensitive wheat genotypes KRL_283/BH 1146, KRL_342/PBW_343, KRS_9301/KRL_213 at early to mid-stages. It may be due to more oxidative damage owing to lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane, which reduced the salinity stress tolerance abilities of wheat genotypes4. Furthermore, irrespective of different DAS, oxidative damage might have resulted in more reduction of total leaf chlorophyll content in sensitive genotypes (HD_3086, KRS_1411, KRS_1319, KRS_9301/KRL 213, and DBW_246) than in tolerant wheat genotypes, which maintained stable pigment that helped in more photosynthesis for better growth and development.

In this study, different multivariate analysis e.g., PCA, HCA and DA were performed to assess salt tolerance of wheat genotypes which helped in (i) evaluating salt tolerance using multiple traits; (ii) it increased the accuracy of ranking of genotypes when they were evaluated at different DAS; (iii) it helped in understanding the complex relationships among the genotypes in more understandable way; (iv) it allowed to identify superior genotypes; (v) helped in interrelation among the traits and in identifying best bio-physical indicator at each DAS for screening wheat genotypes. The PCA was used to identify the performance of wheat genotypes under salinity conditions at different DAS. According to Table 4, the most variation among all analyzed variables was explained by the first two PCs, e.g., 52.43–59.76% at different DAS. Previously, PCA was used by many researchers3,9,13,16,17,19,23 to group wheat genotypes under salinity stress and drought stress conditions. The interrelationships among the parameters were examined using the angles between the parameter vectors on the bi-plot of the principal component analyses. Based on this, the current study identified important bio-physical indicator i.e., transpiration rate and photosynthesis both at 25 and 69 DAS, transpiration rate and NDVI at 52 DAS, RWC and transpiration rate at 90 DAS, total chlorophyll content and OP at 118 DAS that performed significantly in characterizing and screening wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition. Hence, PCA identified 6 most significant bio-physical indicators out of 11 bio-physical parameters used in this study, which later discriminated all the wheat genotypes according to their salt stress tolerance abilities. Irrespective of DAS, transpiration rate, RWC, and total chlorophyll content, showed strong association with genotypes having high NSSTI score, while toxic ions (Na+ and K+) showed a negative correlation with the opposite angle, indicating physiological preciseness under salt stress. Our findings are in same line with the previous reports9,13 that showed the leaf water relations parameters (water potential, osmotic potential, and turgor pressure) and the toxic ion concentrations (Na+ and Cl−) were closely related and could serve as complementary screening criteria for salt tolerance in wheat genotypes. Similarly, in the present study parameters like stomatal conductance, harvest index, photosynthesis, transpiration, and NDVI were identified as sensitive for characterizing and screening wheat genotypes under water stress condition, which were validated with thermal image-based indices. The genotypes with lower toxic ion concentrations have greater biomass and yield, and are able to protect their photosynthetic apparatus under saline field conditions16. Therefore, the bio-physical parameters, transpiration rate, NDVI, Na+ content, total chlorophyll, RWC, photosynthesis can be used as individual or interchangeable screening criteria for salt tolerance. Further, using the most significant bio-physical parameters, the present study discriminated wheat genotypes through discriminant analysis at each DAS. Similarly, other studies3,19 used multivariate techniques to evaluate lentil, and wheat genotypes for their heat and drought tolerance. But unlike their study, NSSTI developed in this study has well defined and universal range. The varied performances of wheat genotypes under salt stress conditions distinguished in this work might reflect the consequence of genetic components. Nevertheless, there is a straightforward necessity to inspect genetic variations present inside the germplasm to save a positive level of hereditary variation for future wheat rearing17. Overall, the findings suggested that for studying genetic variation under salinity condition, PCA, and hierarchical cluster analysis, discriminant analysis could be used as dependable methods for screening wheat genotypes and categorizing them into different groups based on the differences in their phenotypic traits.

In general, restriction in the water uptake results in the closing of stomata and a reduction in leaf transpiration rate, which progressively increases leaf temperature27,34. In this study, irrespective of different DAS, high canopy temperature was recorded in sensitive wheat genotypes e.g., DBW_246, KRL-119/KRS 626, KRL-342/PBW-343, HD-3086, KRS-9301/KRL 213 and that of low canopy temperature was found in tolerant genotypes viz., ASN_SAN_3, ASN_SAN_09, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_SAN_17 at 69 DAS (Fig. 8). Further, the increase in leaf temperature was observed to be more prominent in sensitive wheat genotypes as compared to tolerant genotypes grown under salinity stress condition, similar to the observations on trends in elevation of leaf temperature in wheat crop under salinity stress22. The elevation in canopy temperature, as sensed through thermal cameras, gives an indication of impaired crop physiological condition of sensitive wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition at different DAS. Subsequently, thermal image derived stress indices e.g., CWSI and IG (Figs. 8 and 9a and b) showed significant variations (low CWSI and high IG for tolerant genotypes and vice versa) among the wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition. Previous studies, have shown high CWSI as well as canopy temperature for sensitive genotypes of rice12wheat22,23 and lentil19 under abiotic stress condition. In order to characterize the instantaneous crop status under salinity stress condition, image-based stress maps of CWSI and IG developed in this study, further showed significant variations. Thermal imagery is a powerful tool that captures the temperature differences of crop canopies quite rapidly and non-destructively for a large area and has the abilities to distinguish between salinity stress and non-stressed canopy19,21,22,24. Thus, the image-based CWSI and IG maps developed in this study for wheat genotypes characterized the salinity stress effectively at different DAS. Moreover, the newly developed index e.g., NSSTI showed a significant regression coefficient (R2 with CWSI and IG at different DAS (Fig. 10) which indicates the potential of NSSTI to characterize and identify the salinity stress tolerance in wheat genotypes. NSSTI is a comprehensive crop physiological indicator that varied negatively with CWSI and positively with IG among different wheat genotypes at different DAS and showed good performances in screening and discriminating wheat genotypes under salinity stress conditions. In one of the previous study18 the combined use of thermal and RGB imaging was explored in evaluating salt stress tolerance in wheat, where thermal image-based indices showed good relation with crop yield and biomass at varying levels of salinity. Yield and biomass represent the overall impact of abiotic stress condition on crop health and its ability to survive to produce yield. Although salinity stress impacted the crop yield and biomass of both sensitive and tolerant wheat genotypes, in this study, the effect was found to be more detrimental in sensitive than tolerant wheat genotypes. The highest yield (3.42 t ha−1) and crop biomass (8.78 t ha−1), was observed in wheat genotype ASN_SAN_17, while the lowest was observed in DBW-246 (Fig. 11a). Further, the tolerant wheat genotypes, e.g., ASN_SAN_09, ASN_SAN_18, ASN_CHECK_4, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_1, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-345/KRL 250, showed comparatively good yield and biomass than moderate and sensitive genotypes, i.e., KRS-9301/KRL 213, KRL-283/KRL 239, KRL-119/KRS 626, KRS-1319, KRL-99/HD-2851 grown under similar salinity stress conditions (Fig. 11a). The highest and most significant correlation coefficient was found between NSSTI and crop yield and biomass at 25 DAS (0.82 and 0.84), however, the correlation coefficient at 69 DAS also gave significant relation with NSSTI. Based on the NSSTI score, genotypes that showed high NSSTI scores at the earlier stages i.e., 25 to 69 DAS, gave higher yield and biomass than genotypes that showed less NSSTI score (sensitive genotypes) during those periods. Hence, the newly developed NSSTI index identified variability in salinity tolerance of different wheat genotypes at different stages of crop growth and indicated the overall physiological status as shown by the good relation with thermal image-based crop stress indices, crop yield and biomass. Additionally, important crop biophysical parameters were identified that would be suitable for enhancing salinity stress tolerance through breeding strategy in wheat. Thus, NSSTI has the potential to select salinity tolerant/sensitive wheat genotypes at different DAS under salinity stress condition and can be a useful strategy in crop phenotyping. The significant relationship between thermal indices and NSSTI clearly showed that these indices may be used as a proxy for characterizing salinity stress tolerance in future studies and has the potential to be applied in other environments.

Conclusion

In this study, the newly developed salt tolerance screening index NSSTI comprehensively classified 25 wheat genotypes based on their contrasting salt tolerance abilities at different DAS. The measured biophysical parameters and thermal image-based indices showed significant variations at different DAS for all the wheat genotypes considered in this study. Under salinity stress conditions, NSSTI identified wheat genotypes ASN_SAN_17, ASN_SAN_06, ASN_CHECK_4, and ASN_SAN_18 to be tolerant to salinity stress with consistently high NSSTI values at different DAS, and accumulated lesser toxic ions than wheat genotypes having low NSSTI score, e.g., HD-3086, KRS-9301/KRL 21,3 and KRL-119/KRS 626. Moderately tolerant wheat genotypes (KRL-414, KRL-283/BH 1146, KRS-1411, KRL-345/KRL 250, KRL-342/KRL 304, KRL-99/HS460//KRL99) showed in between responses or to some extent more similar to tolerant genotypes at certain DAS. Wheat genotypes that showed high NSSTI scores at earlier stages were able to give maximum yield and biomass. Thermal image-based stress indices (CWSI and IG) exhibited wide range of genotypic variation across different DAS and were able to distinguish tolerant and sensitive wheat genotypes grown under salt stress condition. Based on the variations in canopy temperature, thermal image-based spatial stress map of different wheat genotypes gave a good understanding of salinity stress effects and crop responses. Additionally, NSSTI also showed significant relation with thermal image-based stress indices at different DAS for all the wheat genotypes under salinity stress condition. Thus, the derived index NSSTI can be used in future as a constructive screening and discriminating tool for comparing a large number of genotypes under typical field conditions for characterizing the salt stress tolerance in wheat as well as in other field crops. The identified wheat genotypes could possibly be used in salt tolerance breeding program, and for better understanding of the mechanism of salt stress tolerance in plants. Further work is required to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms of contrasting genotypes under various levels of salinity for successful use in breeding program.

Data availability

Data is available with the corresponding author, will be shared on reasonable request.

References

USDA-United State Department of. Agriculture; grain: world markets and trade-2023, page 22.

MoAFW & DA&FW- Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Department of Agriculture and Farmers. ’ Welfare releases Final Estimates of major agricultural crops for 2023-24. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2058534#:~:text=The%20Wheat%20production%20during%202023,173.21%20LMT%20during%20previous%20year.

Dadshani, S. et al. Multi-dimensional evaluation of response to salt stress in wheat. PLoS One. 14 (9), e0222659 (2019).

Quan, X. et al. Identification and characterization of wheat germplasm for salt tolerance. Plants, 10(2), p.268. (2022).

Moustafa, E. S. et al. Field screening of wheat advanced lines for salinity tolerance. Agronomy, 11(2), p.281. (2021).

Mansour, E. et al. Multidimensional evaluation for detecting salt tolerance of bread wheat genotypes under actual saline field growing conditions. Plants, 9(10), p.1324. (2020).

Tao, R. et al. Evaluating and screening of agro-physiological indices for salinity stress tolerance in wheat at the seedling stage. Frontiers in plant science, 12, p.646175. (2021).

Oyiga, B. C. et al. Identification and characterization of salt tolerance of wheat germplasm using a multivariable screening approach. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 202 (6), 472–485 (2016).

El-Hendawy, S. E., Hassan, W. M., Al-Suhaibani, N. A., Refay, Y. & Abdella, K. A. Comparative performance of multivariable agro-physiological parameters for detecting salt tolerance of wheat cultivars under simulated saline field growing conditions. Frontiers in plant science, 8, p.435. (2017).

Zeng, L. et al. Evaluation of salt tolerance in rice genotypes by physiological characters. Euphytica 129, 281–292 (2003).

Wu, H. et al. An effective screening method and a reliable screening trait for salt tolerance of Brassica napus at the germination stage. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, p.530. (2019).

Wang, M. et al. Using infrared sensor for large area canopy total temperature measurements of rice plants. Appl. Eng. Agric. 29 (1), 115–122 (2013).

Quamruzzaman, M. et al. Multidimensional screening and evaluation of morpho-physiological indices for salinity stress tolerance in wheat. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 208 (4), 454–471 (2022).

Munns, R. & Gilliham, M. Salinity tolerance of crops–what is the cost? New Phytol. 208 (3), 668–673 (2015).

Singh, S. et al. Assessment of multiple tolerance indices for salinity stress in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). J. Agric. Sci. 7 (3), 49 (2015).

Matković Stojšin, M. et al. Assessment of genotype stress tolerance as an effective way to sustain wheat production under salinity stress conditions. Sustainability, 14(12), p.6973. (2022).

Uzair, M. et al. The characterization of wheat genotypes for salinity tolerance using morpho-physiological indices under hydroponic conditions. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 29(6), p.103299. (2022).

El-Hendawy, S. et al. Potential of thermal and RGB imaging combined with artificial neural networks for assessing salt tolerance of wheat genotypes grown in real-field conditions. Agronomy, 14(7), p.1390. (2024).

Biju, S., Fuentes, S. & Gupta, D. The use of infrared thermal imaging as a non-destructive screening tool for identifying drought-tolerant lentil genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 127, 11–24 (2018).

Banerjee, K. & Krishnan, P. Normalized Sunlit Shaded Index (NSSI) for characterizing the moisture stress in wheat crop using classified thermal and visible images. Ecological Indicators, 110, p.105947. (2020).

Singh, R. N., Krishnan, P., Singh, V. K. & Banerjee, K. Application of thermal and visible imaging to estimate stripe rust disease severity in wheat using supervised image classification methods. Ecological Informatics, 71, p.101774. (2022).

Bayoumi, T. Y., El-Hendawy, S., Yousef, M. S., Emam, M. A. & Okasha, S. A. Application of infrared thermal imagery for monitoring salt tolerant of wheat genotypes. J. Am. Sci. 10 (12), 227–234 (2014).

Banerjee, K., Krishnan, P. & Das, B. Thermal imaging and multivariate techniques for characterizing and screening wheat genotypes under water stress condition. Ecological Indicators, 119, p.106829. (2020).

Kumar, S., Krishnan, P., Singh, P. K., Vashisth, A., Benerjee, K. & Kundu, M. Development of Tomato Fruit Stage Index (TFSI) to characterise different fruit growth stages of tomato using multivariate techniques. J. Food Meas. Charact. 18 (2), 980–999 (2024).

Miransari, M. & Smith, D. Sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production in saline fields: a review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 39 (8), 999–1014 (2019).

Krishnan, P. Application of thermal imaging in plant physiological research. In Souvenir e National Conference on Plant Physiology-2014: Frontiers of Plant Physiology Research: Food security and Environmental Challenges, pp 63e64, Organized by ISPP, OUAT, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, from 23e24, Nov, 2014. (2014).

Banerjee, K., Krishnan, P. & Mridha, N. Application of thermal imaging of wheat crop canopy to estimate leaf area index under different moisture stress conditions. Biosyst. Eng. 166, 13–27 (2018).

Gao, B. C. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 58 (3), 257–266 (1996).

Fang, L. et al. Trophic mode-dependent proteomic analysis reveals functional significance of light-independent chlorophyll synthesis in synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Plant. 10 (1), 73–85 (2017).

Krishnan, P., Ravi, I. & Nayak, S. K. Methods for determining leaf chlorophyll content of rice: A reappraisal. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 34, 1030–1033 (1996).

Yamasaki, S. & Dillenburg, L. R. Measurements of leaf relative water content in araucaria angustifolia. Revista Brasilleira De Fisiologia Vegetal. 11 (2), 69–75 (1999).

Sairam, R. K., Shukla, D. S. & Saxena, D. C. Stress induced injury and antioxidant enzymes in relation to drought tolerance in wheat genotypes. Biol. Plant. 40, 357–364 (1997).

Jackson, M. L. Soil Chemical Analysis (Prentice Hall of India Private Limited, 1973).

Jones, H. G. et al. Thermal infrared imaging of crop canopies for the remote diagnosis and quantification of plant responses to water stress in the field. Funct. Plant Biol. 36 (11), 978–989 (2009).

Leinonen, I., Grant, O. M., Tagliavia, C. P. P., Chaves, M. M. & Jones, H. G. Estimating stomatal conductance with thermal imagery. Plant. Cell. Environ. 29 (8), 1508–1518 (2006).

Jones, H. G. Plants and Microclimate: a Quantitative Approach To Environmental Plant Physiology (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Brejda, J. J., Moorman, T. B., Karlen, D. L. & Dao, T. H. Identification of regional soil quality factors and indicators I. Central and Southern high plains. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64 (6), 2115–2124 (2000).

Abdolshahi, R. et al. Integrated selection criteria for drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) breeding programs using discriminant analysis. Field Crops Res. 174, 20–29 (2015).

Arora, S. & Sharma, V. Reclamation and management of salt-affected soils for safeguarding agricultural productivity. J. Safe Agri. 1, 1–10 (2017).

Kumar, P. & Sharma, P. K. Soil salinity and food security in India. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 4, 533781 (2020).

Hertog, S., Gerland, P. & Wilmoth, J. India overtakes China as the world’s most populous country. (2023).

Luo, Q. et al. Transcriptome analysis of salt-stress response in three seedling tissues of common wheat. Crop J. 7 (3), 378–392 (2019).