Abstract

Land use (LU) change has become one of the primary sources of regional carbon emissions. Investigating the spatiotemporal characteristics and future trends of LU carbon emissions is of great significance for optimizing LU structures, formulating emission reduction policies, and developing a low-carbon economy in the region. Based on data of six LU types and energy consumption from 2000 to 2022 in Xinjiang, this study employs methods such as the LU transfer matrix and land dynamic state to analyze the spatiotemporal changes in LU and carbon emissions in Xinjiang. The results indicate the following: From 2000 to 2022, Xinjiang’s LU has undergone significant structural adjustments. The areas of cropland, forest, water, and impervious have continuously expanded, while the areas of grassland and barren have decreased. According to the LU transfer matrix, from 2000 to 2022, in Xinjiang’s land transitions, grassland mainly transforms into forest. Forest predominantly converts into cropland. Cropland mainly changes into grassland. Water primarily shifts to barren. Barren mainly transforms into cropland. Carbon emissions in Xinjiang accelerated from 2000 to 2022. The annual net carbon emissions growth exceeded 10%, reaching 1.623 billion tons in 2022. Impervious emissions were the primary source of this increase. In contrast, the total carbon sequestration capacity of terrestrial ecosystems increased slowly during this period. Further research indicates that Xinjiang’s carbon emissions generally diffuse from Urumqi outwards to the east and west. Notably, the emission center shows a trend of shifting towards the southwest. The study classifies Xinjiang into four zones based on indicators like net carbon emissions and economic contribution: the low-carbon development zone, the carbon intensity control zone, the carbon sink functional zone, and the high-carbon optimization zone. It then proposes differentiated development strategies for these areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land serves as the foundation for human survival and development, with its utilization patterns and carbon emission effects remaining research focal points in fields such as geography, environmental science, and resource management. Beyond providing a space for human production activities, land is also a medium for the growth of flora and fauna. The various natural resources it harbors, including water and mineral resources, are the foundations of human existence1,2. These resources not only support the economic activities of human societies but also maintain ecological balance and ensure biodiversity3,4. As the scope of human production activities continues to expand, there have been profound changes in LU practices. The acceleration of urbanization and industrialization has led to the conversion of a significant amount of land originally used for agriculture, forestry, or natural ecosystems into impervious, resulting in increasingly strained land resources. Concurrently, irrational LU practices, such as over-cultivation and deforestation, have not only undermined the natural ecological functions of the land but also triggered a series of ecological and environmental issues, including soil erosion, land desertification, and a reduction in biodiversity.

Xinjiang, as the largest provincial administrative region in China, boasts abundant land resources and a diverse range of ecosystems. However, the region’s harsh natural environment and relatively weak economic foundation render LU and carbon emissions particularly complex and critical issues. In recent years, the rapid economic development and continuous population growth in Xinjiang have led to profound changes in LU structure and spatial configuration. The reduction in carbon sink areas and the expansion of carbon source areas, caused by these LU changes, pose severe challenges to the ecological environment and sustainable development of Xinjiang.

Existing research has revealed the characteristics and mechanisms of LU change from multiple scales and dimensions. Liu et al. analyzed the basic characteristics and spatial patterns of LU change in China from 1990 to 20105. Huang examined the relationship between carbon emissions and LU6. Yang et al. studied the transformation and gradient effects of LU in Shaanxi Province based on LU data7. Liu investigated the impact of LU on ecosystem services in the Yellow River Basin8. In the study of LU carbon emissions, Wei et al. used Geographical Weighted Regression (GWR) and other models to explore the spatiotemporal evolutionary characteristics and influencing factors of LU carbon emissions in Guangzhou9. Wang researched the regional flow of LU change and carbon storage in China based on LU and carbon density data10. Moreover, certain studies provided a more detailed classification of LU type; for example, Patel explored the relationship between LU change and agricultural economic growth in India11. Su studied the net carbon sequestration changes of cropland in Shandong Province12. Some scholars have also focused on the spatial changes in agricultural LU and carbon emissions from urban LU13,14, all of which reflect the deepening and broadening of research. However, current research faces two significant limitations. Firstly, regional coverage is uneven, with inadequate attention given to ecologically fragile areas, such as arid regions. Specifically, Xinjiang, a key arid region in Northwest China, exhibits distinct LU and carbon emission characteristics due to its unique climate and geography. Yet, studies on this topic remain fragmented, lacking comprehensive analysis. Secondly, studies often concentrate on single factors or specific local areas. For instance, Zhao et al. examined only how LU change in Xinjiang affects ecosystem service value15. Li and Wang et al. separately investigated land cover change in the Aksu region and the Tarim River Basin16,17. These studies fail to fully capture the spatiotemporal patterns of LU carbon emissions in Xinjiang, as well as the spatial features of its carbon balance zones.

This study analyzes the dynamic changes in LU and carbon emissions based on LU data from 14 cities in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. The findings contribute to revealing the spatiotemporal evolutionary traits of LU in Xinjiang, offering a scientific basis for the rational utilization and planning of land resources. This study’s marginal contribution is systematically integrating LU and carbon emission data across all of Xinjiang, overcoming the geographical fragmentation found in previous research. By employing spatiotemporal dynamic analysis and carbon balance zoning, it reveals the distinctive mechanisms of LU carbon emissions in arid regions, offering a new perspective for regional ecological conservation and low-carbon development.

Study area and data

Study area

Xinjiang encompasses 14 prefectures (cities), covering an area of 1.6649 million square kilometers, approximately one-sixth of China’s total area. With a permanent population of 25.98 million, it is in the western part of the arid region in Northwest China (74° 41′–96° 18′ E, 34° 22′–49° 33′ N). Situated in the interior of the Eurasian continent, Xinjiang is a vital component of the arid zone in Central Asia. An overview of the study area is provided in Fig. 1. In 2023, Xinjiang’s GDP reached 1.91 trillion RMB (approximately 270 billion USD). The primary industry contributed about 14% to this total. The region produces over 90% of China’s cotton. Its specialty fruit industry and animal husbandry are thriving. By the end of 2023, Xinjiang’s permanent resident population was approximately 25.98 million, with ethnic minorities accounting for more than 50% of the total (The data are sourced from the Xinjiang Statistical Bureau). Xinjiang’s topographical pattern is characterized by “three mountains and two basins,” namely, the northern Altay Mountains, the central Tianshan Mountains, and the southern Kunlun Mountains, which enclose the Junggar Basin and the Tarim Basin. This configuration gives rise to a unique combination of mountainous, oasis, and desert ecosystems18. Although Xinjiang is rich in land resources, its complex terrain includes various geomorphic types such as high mountains, basins, deserts, and grasslands. Its grassland resources serve as a significant base for animal husbandry. The climate in Xinjiang is complex and variable, with a unique water cycle, rendering the ecological environment extremely vulnerable. In the global context of arid regions, Xinjiang holds unique representativeness. Changes in its ecosystems, water resources, and climatic characteristics not only affect the local ecological environment and economic development but also have a significant impact on global climate change and ecosystem balance.

Research data

The data used in this study are all derived from public databases. Sources of LU data, energy consumption, and economic statistics by province and city are listed in Table 1.

The CLCD dataset from Wuhan University encompasses nine land types. In this study, LU types are consolidated and categorized into six types: Cropland, Forest, Grassland, Water, Impervious, and Barren.

Research methodology

Calculation of land carbon emission

The carbon emissions from Cropland, Forest, Grassland, Water, and Barren are calculated directly using the carbon emission coefficient method. The carbon emission from Impervious is calculated using an indirect method. The carbon emission coefficients for Cropland, Forest, Grassland, Water, and Barren are 0.422, − 0.612, − 0.021, − 0.235, − 0.005 (t/hm2), respectively20,21,22,23. A negative carbon emission coefficient indicates carbon sequestration, while a positive coefficient indicates carbon emission. The calculation method for LU carbon emission is as follows:

Among these, \(\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{\text{i}}\:\)represents the carbon emission coefficient for different land types, and \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{i}\text{t}}\)(hm2) represents the area of different land types in various regions.

Drawing on the research of relevant scholars, this study calculates the carbon emission from Impervious based on the energy consumption of raw coal, coke, natural gas, crude oil, gasoline, diesel, kerosene, fuel oil, and liquefied petroleum gas in Xinjiang24,25. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{{\upgamma\:}}_{\text{i}}\:\)represents the conversion coefficient for different types of energy to standard coal. For solid fuels, it is the weight of standard coal required per kilogram of energy consumed, and for gaseous fuels, it is the weight of standard coal required per cubic meter of energy consumed. \(\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{i}}\) represents the carbon emission coefficient for different types of energy, and \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{i}\text{t}}\:\)represents the consumption of different types of energy in various regions. The energy consumption is converted into standard coal for calculation. The conversion coefficients and carbon emission coefficients for various types of energy are presented in Table 226,27,28.

Calculation of land area by type

This study analyzes the LU data in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022 by integrating LU transfer matrices and LU dynamics. The principles of LU transfer matrices and LU dynamics are detailed in references29,30. Additionally, ArcGIS 10.8 is employed to process the reclassified LU raster data for the years 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2022. The Raster Calculator tool is used to compute and export the data.

Economic contribution rate of LU carbon emission

The economic contribution rate of carbon emissions (ECE) indicates the degree to which a region’s carbon emissions influence its economic benefits. The expression formula is as follows31:

Among them, \(\:{\text{G}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the GDP of the i region in Xinjiang, \(\:\text{G}\) denotes the total GDP of the 14 regions in Xinjiang.\(\:{\text{C}\text{E}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the LU carbon emission of the i region in Xinjiang, and \(\:\text{C}\text{E}\) denotes the total LU carbon emission of the 14 regions in Xinjiang. \(\:\text{E}\text{C}\text{E}\)>1 denotes a higher economic contribution rate of carbon emission, meaning a larger contribution to economic benefits. 0<\(\:\text{E}\text{C}\text{E}\)< 1 denotes a lower economic contribution rate of carbon emission, implying a smaller contribution to economic benefits.

Ecological carrying coefficient of LU carbon sequestration

The carbon absorption ecological carrying coefficient (ECS) measures the strength of a region’s carbon sequestration capacity, with the specific expression as follows:

Among them,\(\:{\text{C}\text{S}}_{\text{i}}\)denotes the carbon sequestration amount through LU in the i region of Xinjiang, and \(\:\text{C}\text{S}\) denotes the total carbon sequestration amount through LU across the 14 regions of Xinjiang. \(\:\text{E}\text{C}\text{S}\)>1 denotes that the region contributes relatively more to overall carbon absorption than to overall carbon emissions. This suggests the region possesses a strong LU carbon absorption capacity, absorbing more carbon than it emits. Consequently, it exerts a positive influence on the overall carbon balance. 0 < \(\:\text{E}\text{C}\text{S}\)< 1 denotes that the region’s contribution to overall carbon absorption is less than its contribution to overall carbon emissions. The carbon absorbed is proportionally smaller compared to the carbon emitted, reflecting insufficient ecosystem carbon sequestration capacity. Consequently, in the overall carbon balance, this region may potentially contribute to a relative burden.

Standard deviational ellipse (SDE)

The standard deviational ellipse (SDE) is a classic spatial statistical technique. It reveals the central location, spread, and orientation of the spatial distribution of geographic features like LU changes, carbon emission sources, and population distributions. In LU and carbon emission studies, this method identifies the spatial clustering patterns and their temporal changes for various land cover types or carbon emission hotspots. The SDE identifies the mean center of spatial, direction angle, and standard deviation distance, forming an ellipse that outlines their primary distribution area.The mean center indicates the spatial distribution center of the elements. Its calculation formula is32:

The rotation angle (\(\:{\uptheta\:}\)) indicates the primary direction of the element distribution. Its calculation formula is:

The calculation formula for the standard deviation along the x-axis is:

The calculation formula for the standard deviation along the y-axis is:

Here, n is the number of elements, \(\:({\text{x}}_{\text{i}},{\text{y}}_{\text{i}})\) is the coordinate of the \(\:\text{i}\) element, and \(\:{\omega\:}_{i}\) is the weight for the \(\:\text{i}\) element’s coordinate. \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{x}_{i}}={x}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{x}\), \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{y}_{i}}={x}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{x}\), \(\:{\uptheta\:}\) is the azimuth angle of the ellipse.

Results analysis

Analysis of the area changes of different land types in Xinjiang

Research using CLCD dataset (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4417809) of xinjiang in 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2026, 2022, the land use status data for the raw data, The area changes of cropland, forest, grassland, impervious and barren in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022 were fabricated by reclassifying land use types using ArcGIS10.8 software (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Based on the land area data presented in Table 3, the overall trend shows a continuous increase in cropland, forest, water, and impervious, with a decrease trend in grassland. The area of barren also exhibits a downward trend, but its area increased after 2020. Table 3 shows the dynamic changes in LU area in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. The expansion of impervious areas was the most significant. Between 2000 and 2022, their area increased by 4145.468 km2, with an average annual growth of 188.430 km2. Cropland expanded continuously from 2000 to 2016, increasing by a total of 25,782.98 km2. However, it decreased between 2016 and 2020 before increasing again by 2022. Water first increased and then decreased. It grew by 7483.10 km2 from 2000 to 2016, but declined by 5078.73 km2 from 2016 to 2022. Cropland expanded continuously from 2000 to 2016, increasing by a total of 25,782.98 km2. However, it decreased between 2016 and 2020 before increasing again by 2022. Water first increased and then decreased. It grew by 7483.10 km2 from 2000 to 2016, but declined by 5078.73 km2 from 2016 to 2022. Barren first decreased and then increased. It decreased by 27,005.373 km² from 2000 to 2016. Subsequently, its area started to increase, adding 10,892.911 km² from 2016 to 2022. However, overall from 2000 to 2022, there was a net decrease of 16,112.409 km². Analyze the reasons, from the perspective of natural factors, the Xinjiang region is ecologically fragile, characterized by sparse vegetation and diverse types of soil erosion with complex interactions. The interplay of water, wind, and frost actions exacerbates the issue of soil erosion. Additionally, the region’s climate, marked by frequent winds and scarce rainfall, intensifies the wind erosion. Regarding human factors, the pastoral industry in Xinjiang is well-developed, yet some herding practices employed by pastoralists over the long term have led to excessive depletion of grassland vegetation and severe soil erosion. This has resulted in overgrazing and significant degradation of grasslands, leading to a sharp reduction in grassland area and an escalating conflict between grazing animals and vegetation. Population growth and the inappropriate development and utilization of water and soil resources have also been significant contributors to the destruction of surface vegetation and the intensification of soil erosion.

The LU transition matrixes in Xinjiang

The shift matrix for LU changes in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022 is presented in Table 4. With respect to the changes in grassland, a total of 114,555 km2 of grassland was converted to other land types. The main transformations were into forest, cropland, and barren, with 67,705 km2 of grassland converting to barren. This shift may be attributed to the well-developed livestock industry in Xinjiang, where overgrazing could lead to the degradation of pastures. According to Xinjiang’s livestock statistics (in 2022, the inventory of pigs, cattle, and sheep reached 59.8565 million, an increase of 6.5% from the previous year), livestock numbers have been continuously increasing. This has led to the increasingly prominent issue of livestock carrying capacity exceeding the standard. This undeniably accelerates the process of grassland desertification and severely damages the grassland ecosystem.

In terms of forest changes, 8286 km2 of forest has been converted to other land types, with more than 85% being transformed into cropland. This reflects the increasing demand for agricultural products as Xinjiang’s population grows and living standards rise. To meet this demand, some forests have been converted into cropland. This expansion of agricultural land aims to increase food production. However, the reduction in forests may also lead to issues such as soil erosion and climate change.

With respect to the changes in cropland, a total of 18,110 km2 of cropland has been converted to other land uses. Of this, nearly 75% was transformed into grassland. This data fully demonstrates the significant success of the cropland conversion to grassland policy in Xinjiang. After 2002, Xinjiang officially launched large-scale implementation of this policy, gradually converting cropland in ecologically fragile areas into grassland. The implementation of this policy helps restore grassland ecosystems, improve the regional ecological environment, and also promotes the sustainable development of animal husbandry, achieving a positive interaction between ecological protection and economic development.

Regarding the changes in water, a total of 15,140 km2 of water has been converted to other land uses, with more than 75% transformed into barren. This indicates a significant degradation of water in Xinjiang. On one hand, this may be influenced by Xinjiang’s natural environmental factors, such as arid climate and high evaporation. On the other hand, human activities like excessive groundwater extraction and irrational water resource allocation have accelerated the shrinkage and degradation of water. This adversely affects aquatic ecosystems, as well as the ecological environment and economic development in surrounding areas.

In terms of the changes in barren, a total of 84,216 km2 of barren has been converted to other land uses. This mainly includes grassland, cropland, and impervious. This indicates that over the past two decades, Xinjiang has experienced rapid economic development and urbanization. Specifically, 68,581 km2 of barren has been transformed into grassland. This indicates that Xinjiang has taken proactive and effective measures in ecological governance and restoration. For example, large-scale afforestation, grass planting, and desertification control projects have been implemented. These efforts transformed vast barren into ecologically functional grassland, thereby improving the regional ecological environment and enhancing the land’s ecological value. Simultaneously, economic growth requires more land for agricultural expansion to ensure food security and agricultural product supply. Urbanization also demands extensive impervious for infrastructure, housing, and industrial development. These factors drive the conversion of barren into cropland and impervious, contributing to Xinjiang’s socio-economic development.

Analysis of the temporal and spatial evolution of the LU carbon emissions in Xinjiang

The carbon emissions from cropland, forest, grassland, water, and barren in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022 are obtained through LU data. Subsequently, the indirect carbon emissions from impervious in Xinjiang are calculated based on energy consumption data. This results in the total carbon emissions from LU in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022 (as shown in Fig. 3). Temporally, the net carbon emissions from LU in Xinjiang increased from 15,886.954 thousand tons in 2000 to 162,302.518 thousand tons in 2022, with an annual growth rate exceeding 10%, demonstrating a strong growth trend. In contrast, the total carbon absorption in Xinjiang grew slowly from − 3317.309 thousand tons in 2000 to − 3607.063 thousand tons in 2022. Compared with other studies, Zhang Ruqian et al. found that the net carbon emissions from LU in Xinjiang increased to 1.269 × 108 tons from 2000 to 2018, which is relatively close to the data in this study33.

Table 5 presents the total carbon emissions (absorption) from various types of land in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. Viewing the total carbon emissions (absorption) by land type, the emissions from cropland and impervious in Xinjiang have been continuously increasing, with the growth rate of carbon emissions from impervious being particularly rapid. This, to some extent, reflects the rapid economic development and significant urbanization in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. The rapid economic development has led to increased industrial, commercial, and residential energy demands. As urbanization accelerates, urban construction and infrastructure continue to improve, expanding the scale of impervious, which has resulted in the rapid growth of carbon emissions from this land type. The carbon absorption of forest, grassland, and water has remained relatively stable during the study period, with forest and water showing a slow growth trend in carbon absorption, while grassland carbon absorption has shown a declining trend.

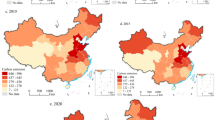

Figure 4 illustrates the evolutionary trend of carbon emissions across 14 cities in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. Spatially, the main concentration of LU carbon emissions is in the eastern and western regions, with Urumqi at the center. The distribution of carbon emissions in these cities generally corresponds to their economic output, suggesting a strong correlation between economic development and carbon emissions. From 2000 to 2008, Urumqi and Karamay were the primary contributors to LU carbon emissions. As urbanization intensified around Urumqi, LU carbon emissions rose sharply. By 2022, the number of major cities with significant LU carbon emissions in Xinjiang increased from 2 to 6, predominantly in the eastern and western parts of the region. This shift indicates a changing pattern of LU carbon emissions, expanding beyond traditional economic centers to more cities.

In terms of the growth rate of LU carbon emissions, both Yili and Hami have experienced a remarkable surge, ascending from the third tier in 2000 to the first tier in 2022, demonstrating a strong growth trend. Geographically, Yili is a pivotal corridor connecting Xinjiang with Central Asia, West Asia, and Europe, offering unique location advantages and serving as an important platform for foreign trade and border cooperation. Hami, situated in the eastern part of Xinjiang, is a key node city on the Silk Road Economic Belt. Its strategic location and convenient transportation make it a pivotal city for Xinjiang to enhance connectivity with inland regions and neighboring countries. With the advancement of the national “Belt and Road” initiative and the rapid development of Xinjiang, both Yili and Hami are set to have broader development prospects.

To further analyze the spatial changes in LU carbon emission in Xinjiang, ArcGIS 10.8 software was used to create standard deviation ellipses and shifts in the center of gravity for LU carbon emission from 2000 to 2022 (as shown in Fig. 5). The spatial distribution of LU carbon emission in Xinjiang exhibits a significant east-west trend. From 2000 to 2022, the standard deviation ellipses of LU carbon emission in Xinjiang primarily encompass cities such as Urumqi, Changji, and Karamay, which are important economic centers in the region and likely have relatively high levels of LU carbon emission.

As indicated in Fig. 5, the center of gravity of LU carbon emission in Xinjiang shows an overall migration trend from the central-northern part of the region towards the southeast from 2000 to 2022. The regional differences in economic development across Xinjiang are pronounced, with the central-northern areas mainly engaged in traditional agriculture, animal husbandry, and tourism, which consume less energy. In contrast, the southeastern areas are dominated by industry, services, and other sectors with higher energy demands. This difference in industrial structure may lead to changes in LU patterns and carbon emission intensity, thereby influencing the migration of the carbon emission center of gravity in Xinjiang.

Spatial pattern analysis of LU carbon balance in Xinjiang

Figure 6 presents the locational map of carbon balance in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2022. From 2000 to 2012, regions in Xinjiang that achieved carbon balance were primarily those with weaker economic development, such as Hetian. These areas, characterized by lower population densities and slower expansion of impervious and cropland, had a relatively low energy demand. This resulted in the carbon emission from impervious and cropland being less than the carbon sequestration by forests and grasslands.

After 2012, all 14 regions in Xinjiang entered the non-carbon balance zone, indicating an accelerated pace of urban construction in Xinjiang. On one hand, the increase in population density led to the expansion of impervious and an increased demand for energy, thereby raising carbon emissions from impervious and cropland. On the other hand, due to the expansion of population and economic activities, there was a reduction in forested and grassland, leading to a decline in carbon sequestration capacity and disrupting the original state of carbon balance.

Therefore, while amidst the process of rapid urban expansion, Xinjiang should comprehensively consider how to balance economic development with environmental protection. On one hand, it is imperative to augment efforts in ecological protection and restoration to rehabilitate and augment the carbon sequestration capabilities of natural ecosystems. On the other hand, the development of a low-carbon economy and circular economy should be considered to improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions.

Xinjiang territorial spatial planning

Using formulas (3) and (4), the ECE and ECS values for Xinjiang’s 14 regions were calculated. Based on these coefficients, the regions were categorized into carbon sink functional areas, low-carbon economic areas, carbon intensity control areas, and high-carbon optimization areas (Fig. 7), and the criteria for the functional area classification are outlined in Table 6. This zoning serves as a reference for future carbon emission reduction policies and development strategies in various regions across Xinjiang.

For Xinjiang’s main functional zone planning, the study divides the areas based on development content into optimized development zones, key development zones, major agricultural product production zones, and key ecological function zones, as shown in Fig. 5.

-

(1)

Low carbon development areas. From 2000 to 2022, Xinjiang has had a total of 6 regions, including Hetian, consistently designated as low-carbon development areas, reflecting an effective balance between the economy and ecological health. These regions, mainly in southern and northwestern Xinjiang, are characterized by extensive agricultural and pastoral activities, large land areas, and low population densities, making them conducive to agricultural production. Their distance from the economic center has curtailed the growth of high-energy, high-emission industries, and facilitating the development of a unique model of ecological agriculture and pastoralism due to their unique geographical location. To be specific, in southern Xinjiang, regions like Hetian use water resources from rivers such as the Tarim to support irrigation and specialty agriculture, thereby creating local agricultural brands. In the northwestern part of Xinjiang, regions like Yili Valley, with its vast grasslands and forests, have developed a balanced agriculture and pastoral economy, promoting both economic and ecological benefits. These regions need to continue to enhance eco-agriculture and pastoralism. With improved technology and management, leveraging abundant natural resources will enhance specialized farming and quality pastoralism. It is essential to protect the environment, preserve biodiversity, and ensure sustainable agriculture.

-

(2)

Carbon Intensity Control Zone. These regions exhibit high economic contribution for carbon emissions but exhibit low ecological carrying coefficients. Turpan was the primary area, and then transitioned to Urumqi and Akesu. exhibit high economic contribution to carbon emissions but low ecological carrying capacity. Initially, Turpan was identified as a carbon intensity control area before transitioning to a high-carbon optimization area, reflecting economic challenges and a decline in carbon emission efficiency. Conversely, Urumqi and Akesu shifted from high-carbon to carbon intensity control areas, indicating improved emission efficiency and a move towards sustainable development. These areas should adopt strategies to align economic growth with environmental protection, enhancing carbon emission efficiency and promoting a greener economy.re transitioning to a high-carbon optimization area, reflecting economic challenges and a decline in carbon emission efficiency. Conversely, Urumqi and Akesu shifted from high-carbon to carbon intensity control areas, indicating improved emission efficiency and a move towards sustainable development. These areas should adopt strategies to align economic growth with environmental protection, enhancing carbon emission efficiency and promoting a greener economy.

-

(3)

Carbon Sink Functional Zone. These regions feature high ecological carrying coefficients but low economic contribution coefficients for carbon emissions. Initially, areas such as Altay and Hami were classified as carbon sink functional areas. Over time, Altay transitioned to a low-carbon development area, indicating enhanced economic efficiency of carbon emissions through industrial upgrading while preserving the ecological environment. Hami, however, not only failed to optimize its industrial structure and develop low-carbon industries, but the growth of high-pollution and high-consumption industries also impaired the region’s ecological carrying coefficient to some extent. These areas should promptly adjust their industrial structures, phase out outdated production capacity, and foster the development of low-carbon and environmentally friendly emerging industries.

-

(4)

High Carbon Optimization Zone. Regions in this category have low ecological carrying coefficients and economic contribution coefficients for carbon emissions, often facing significant environmental pressure and transformation challenges during economic development. Initially, these areas primarily included cities in the northeast and west, later becoming more concentrated in the northeast. Early on, regions such as Karamay and Changji were dominant; their resource endowments led to a relatively simplistic industrial structure dominated by industrial and resource-based industries. Over time, cities like Akesu have gradually moved out of the high carbon optimization areas, while some cities in the northeast continue to face substantial environmental pressure and transformation challenges due to difficulties in industrial structure adjustment and transformation. Karamay’s economic development is closely linked to the oil and petrochemical industry. On November 28, 2023, the National Development and Reform Commission designated Karamay as one of the first batch of pilot cities for carbon peak, providing a significant opportunity for its green and low-carbon transformation. Regions such as Changji, Turpan, and Hami are also actively promoting industrial transformation, upgrading, and green, low-carbon development. These areas should take proactive measures to drive industrial transformation and upgrading, as well as green and low-carbon development, while also advancing ecological environmental protection and governance efforts.

Conclusion and discussion

Conclusion

-

(1)

From 2000 to 2022, the area of cropland, forest, water, and impervious in Xinjiang has shown an overall trend of continuous expansion, while grassland and barren have continuously contracted. Over the 20-year period, the area of cropland in Xinjiang has increased by 41.97%, forest by 26.41%, water by 5.63%, and impervious by 361.52%. Conversely, the areas of grassland and barren have decreased by 5.08% and1.44%, respectively.

-

(2)

From 2000 to 2022, Xinjiang experienced a conversion of 114,555 km2 of grassland into other land types, with 59.10% of this conversion being to barren. A total of 8286 km2 of forest was transformed into other land types, with 95.18% of this area being converted to grassland. The conversion of 18,110 km2 of cropland resulted in 74.95% being transformed into grassland. An area of 15,140 km2 of water was converted to other land uses, with 75.07% being transformed into barren. Additionally, a total of 84,216 km2 of barren was converted to other land uses, with 81.43% of the barren being transformed into cropland.

-

(3)

From 2000 to 2022, the LU carbon emissions in Xinjiang have shown a trend of continuous expansion without any sign of deceleration. This is primarily due to the excessive growth in carbon emissions from impervious. The carbon emissions (absorption) from cropland, forest, water, and barren have remained relatively stable overall. The net carbon emissions in Xinjiang increased from 15,886.954 × 102 tons in 2000 to 162,302.518 × 102 tons in 2022, with an annual growth rate exceeding 10%, indicating a strong growth trend. The carbon emissions from impervious increased from 16,628.671 × 102 tons in 2000 to 162,247.399 × 102 tons in 2022, with a growth rate exceeding 11%, which is higher than the growth rate of Xinjiang’s net carbon emissions. The total carbon absorption in Xinjiang grew slowly from − 3317.309 × 102 tons in 2000 to − 3607.063 × 102 tons in 2022.

-

(4)

From 2000 to 2022, the LU carbon emissions of the 14 cities in Xinjiang display an east-west spatial pattern, characterized by a diffusion from Urumqi as the central point towards both the eastern and western regions. The spatial distribution of these emissions generally aligns with the spatial distribution of the cities’ economic output. Notably, Yili and Hami exhibit a significant growth trend in carbon emissions. The migration of the carbon emission center of gravity indicates a trend of LU carbon emissions in Xinjiang shifting towards the southwest.

-

(5)

According to carbon balance analysis, the scope of the low-carbon development areas in Xinjiang has been gradually expanding from 2000 to 2022, while the number of high-carbon optimization areas has been decreasing. Specifically, most cities in the southern and eastern parts of Xinjiang have consistently remained within the low-carbon development areas. Urumqi and Akesu are transitioning from high-carbon optimization areas to low-carbon development areas. In contrast, the results for Turpan and Hami indicate the opposite trend.

Discussion

-

(1)

Ecological significance of LU change.

Significant changes in Xinjiang’s LU types reflect a balancing act between ecological protection and development needs. Large-scale conversions of grassland to forest and cropland may pose ecological risks and affect the livelihoods of nomadic peoples. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the ecological, economic, and social benefits of LU transformation. Reasonable LU planning should be formulated. Conversions of grassland to forest should have clear proportional thresholds. While controlling the pace of conversion in ecologically sensitive areas, mixed forest-grassland models should be promoted. Vegetation proportions should be configured based on local practical experience, balancing the enhancement of carbon sequestration capacity and the assurance of grassland carrying capacity. For the conversion of forest to cropland, an assessment system for water conservation coefficients should be established. When forest reduction significantly impacts groundwater recharge, approvals for cropland expansion shall be suspended. Simultaneously, a cropland replacement policy should be implemented in key watersheds, compensating for forest occupation through saline-alkali land improvement and enhancing water efficiency with supporting water-saving facilities.

-

(2)

Industry-driven economic transformation.

LU change directly reflects regional economic development. Urbanization and metropolitan expansion have led to a surge in Xinjiang’s cropland and impervious. A high-carbon-dependent development model has caused carbon emissions to grow by over 10% annually. Most of this increase comes from impervious. This indicates that Xinjiang urgently needs economic transformation. On one hand, establish “carbon intensity” control standards for impervious. This aims to reduce carbon emissions per unit area for new impervious development. The implementation of building large-scale photovoltaic bases in suitable areas and installing supporting power facilities will promote the low-carbon transformation of the energy structure. On the other hand, optimize agricultural industrial chains like cotton textiles and forestry products. Promote low-carbon planting techniques such as water-saving irrigation. Provide government subsidies to farmers adopting low-carbon practices. Also, subsidize low-carbon agricultural product processing industries. This helps offset the costs of emission reduction.

-

(3)

Urban carbon emission management strategy.

Urban carbon emissions from LU vary spatially across Xinjiang. Therefore, differentiated carbon emission management policies should be formulated based on local conditions. This promotes coordinated regional development. Urumqi, as the central city, accounts for over 30% of the region’s carbon emissions. This is highly correlated with its economic output. Secondary cities like Ili and Hami, as “Belt and Road” nodes, have seen rapid carbon emission growth due to large infrastructure investments. To address this, a three-tiered control strategy is needed: For the core area, Urumqi, promote emission reductions in energy-intensive industries like steel and chemical manufacturing. Limit the expansion of these industries. Offer policy incentives to enterprises that meet carbon emission targets through performance assessments. For secondary cities like Ili and Hami, establish a carbon emission budgeting system. Incorporate the carbon emissions of new projects into land transfer conditions. For ecological zones like Altay and Bayingolin, implement a carbon sink compensation mechanism. Calculate the carbon sequestration capacity of natural forests. Industrial cities should purchase these carbon sinks. The funds raised should be used for ecological protection and relocation support. Additionally, enhance the carbon emission monitoring network using tools like satellite remote sensing. This enables spatially precise control.

This study has the following limitations: Firstly, due to data availability and spatial analytical capabilities, the research was unable to investigate carbon emissions and their zoning at the county level in Xinjiang. Future scholars with interest in this area may conduct more comprehensive studies to explore aspects not covered in this paper. Secondly, constrained by methodological limitations, the LU carbon emission coefficients employed in this paper were based on previous scholarly research. Carbon emission coefficients can vary slightly across different regions. Finally, regarding the efficiency of carbon emissions from LU, decoupling models and other measurement models can also be adopted. Interested scholars in the future can delve deeper into the examination of carbon emission.

Data availability

All data are fully available without restriction. The datasets are taken from several public repository, Wuhan University CLCD Dataset (http://irsip.whu.edu.cn/resources/CLCD.php), Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Science Data Center (http://www.resdc.cn), Xinjiang Statistical Yearbook (https://tjj.xinjiang.gov.cn/tjj/tjfw/list_tjfw.shtml).

References

Li, W., Yang, C., Wang, L. & Feng, B. National attractive territorial area: a national spatial planning strategy reshaping regional patterns. J. Nat. Resour. 35, 501–512 (2020).

Sun, X., Zhou, H. & Xie, G. E. Services and their values of Chinese agroecosystem. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 17, 55–60 (2007).

Nagendra, H., Reyers, B. & Lavorel, S. Impacts of land change on biodiversity: making the link to ecosystem services. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 503–508 (2013).

Haines, Y. R. Land use and biodiversity relationships. Land. Use Policy. 26, 178–186 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics,patterns and causes of land use changes in China since the late 1980s. Acta Geogr. Sin. 69, 3–14 (2014).

Huang, S., Xi, F., Chen, Y., Gao, M. & Ren, C. Land use optimization and simulation of low-carbon-oriented—A case study of Jinhua. China Land. 10, 1020 (2021).

Yang, S., Li, L., Ma, J. & Guo, W. Land use transitions and its terrain gradient effects based on production-living-ecological spaces in Shaanxi Province during 1990–2020. Arid Zone Res. 41, 1249–1258 (2024).

Liu, B., Pan, L., Yue, Q., Xiao, G. & Li, J. Land use and land cover change in the yellow river basin from 1980 to 2015 and its impact on the ecosystem services. Land 10, 1080 (2021).

Wei, J., Mei, Z., Ma, J. & Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of Land-Use carbon emissions in Guangzhou. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 31, 298–307 (2024).

Wang, S., Zhou, S., Wu, R., Feng, K. & Hubacek, K. Interregional flows of embodied carbon storage associated with land-use change in China. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 114, 1526–1545 (2024).

Patel, S. K., Verma, P. & Shankar, S. G. Agricultural growth and land use land cover change in peri-urban India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 1–17 (2019).

Su, H. et al. Relationship between net carbon sequestration change and cultivated land use benefit of cultivated land use in Shandong Province. Scientia Geogr. Sinica. 44, 864–873 (2024).

Carpio, A., Ponce-Lopez, R. & Lozano-García, D. F. Urban form, land use, and cover change and their impact on carbon emissions in the Monterrey metropolitan area, Mexico. Urban Clim. 39, 100947 (2021).

Zhang, R., Matsushima, K. & Kobayashi, K. Can land use planning help mitigate transport-related carbon emissions? A case of Changzhou. Land. Use Policy. 74, 32–40 (2018).

Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Bo, X., Li, Y. & He, Z. Land use change and its impact on ecosystem service value in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020. J. Tianjin Normal Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 43, 53–60 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Land cover change in Aksu region of Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 26, 172–179 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution of land use and human activity intensity in the Tarim River Basin, Xinjiang. Geol. China. 51, 203–220 (2024).

Shi, Q. et al. Landscape classification system based on climate, landform, ecosystem: a case study of Xinjiang area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 34, 3359–3367 (2014).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3907–3925 .

Zhang, C. et al. Spatial-temporal characteristics of carbon emissions from land use change in yellow river delta region, China. Ecol. Ind. 136, 108623 (2022).

Houghton, R. A. et al. Carbon emissions from land use and land-cover change. Biogeosciences. 9, 5125–5142 (2012).

Sun, H., Liang, H., Chang, X., Cui, Q. & Tao, Y. Land use patterns on carbon emission and Spatial association in China. Econ. Geogr. 35, 154–162 (2015).

Xu, Y., Guo, N., Ru, K. & Fan, S. Characteristics and optimization strategies of territorial space zone in Fujian province, China based on carbon neutrality. J. Appl. Ecol. 33, 500–508 (2022).

Li, Y., Wei, W. & Zhou, J. Changes in land use carbon emissions and coordinated zoning in China. Environ. Sci. 44, 1267–1276 (2023).

Meng, H., Zhang, X., Du, X. & Du, K. S. Heterogeneity of the characteristics and influencing factors of Energy-Consumption-Related carbon emissions in Jiangsu Province based on DMSP-OLS and NPP-VIIRS. Land 12, 1369 (2023).

Gui, D., He, H., Liu, C. & Han, S. Spatio-temporal dynamic evolution of carbon emissions from land use change in Guangdong Province, China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 156, 111131 (2023).

Wei, Y. & Chen, S. Spatial correlation and carbon balance zoning of land use carbon emissions in Fujian Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41, 5814–5824 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Spatial and temporal evolution characteristics of carbon emission from land use and influencing factors in Gansu Province. Environ. Sci. 45, 5040–5048 (2024).

Wang, J., Chen, Y., Shao, X., Zhang, Y. & Cao, M. Land-use changes and policy dimension driving forces in china: present, trend and future. Land. Use Policy. 29, 737–749 (2012).

Wang, P., Li, R., Liu, D. & Wu, Y. Dynamic characteristics and responses of ecosystem services under land use/land cover change scenarios in the Huangshui river basin, China. Ecol. Ind. 144, 109539 (2022).

Xia, S. & Yang, Y. Spatio-temporal differentiation of carbon budget and carbon compensation zoning in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration based on the plan for major Function-oriented zones. Acta Geogr. Sin. 71, 679–696 (2022).

Li, S., Bing, Z. & Jin, G. Spatially explicit mapping of soil conservation service in monetary units due to land use/cover change for the three Gorges reservoir area, China. Remote Sens. 11 (4), 468 (2019).

Zhang, Q., Li, P. & Xu, L. Effects of urbanization on carbon emission from land use in Xinjiang and their coupling relationship. Acta Ecol. Sin. 42, 5226–5242 (2022).

Funding

This work is supported by the Major Projects of the Ministry of Education (Grant Number: 22JZDZ021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, J.H.; Funding acquisition, L.Z.; Investigation, J.H.; Methodology, J.H.; Project administration, L.Z.; Resources, J.H.; Software, M.S.; Supervision, L.Z.; Writing-original draft, M.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Song, M. & Zhang, L. Spatial and temporal evolution of land use carbon emission and carbon balance zoning: evidence from Xinjiang China. Sci Rep 15, 35705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19475-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19475-9