Abstract

Geographical environmental factors affect the secondary metabolism of plants and regulate rhizosphere microorganisms. However, the metabolite characteristics and rhizosphere microbial composition of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L., AG) from different sources remain unclear. In this study, high-throughput sequencing technology and metabolomics technology were used to analyze the microbial community structure and metabolite content in the rhizosphere soil of AG from different habitats, and the relationships between soil microorganisms and metabolites were analyzed. The results revealed that the diversity of rhizospheric soil bacterial and fungal communities in different habitats was unusual and affected the metabolite content. The bacterial genera strongly correlated with the triterpenoid saponins of AG included Bradyrhizobium and Pseudoxanthomonas. Among these, Bradyrhizobium was strongly negatively correlated with ginsenoside Rg1 (P < 0.001, r = − 0.8204), and Pseudoxanthomonas was strongly positively correlated with (PPD -2 H)-Glc-Glc-malonyl (P < 0.01, r = 0.6305). The fungal genera included Alternaria and Colletotrichum. Alternaria was strongly negatively correlated with ginsenoside F1 (P < 0.001, r = − 0.7434), and Colletotrichum was also strongly negatively correlated with ginsenoside F1 (P < 0.001, r = − 0.7106). The results revealed a complex correlation between rhizosphere-dominant microorganisms and the saponin content of AG, providing a theoretical basis for guiding rational cultivation planning and designing microbial fertilizers to enhance AG quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Panax quinquefolius L. (American ginseng, AG), an important economic crop, has been widely recognized for its potential benefits in combating fatigue and cancer and in protecting the cardiovascular system and enhancing immunity, securing a place in the health product markets of several countries1,2,3. In China, AG is also categorized as a food-medicated homologous species4. The plant contains a variety of medicinally active components, including saponins, polyacetylenes, and polyphenols, among which ginsenosides are considered the primary active ingredients and are particularly valuable for quality assessment5.

China has become the third-largest producer of AG globally, with its main production areas concentrated in Northeast China, Shandong Province, and Shaanxi Province6,7. In this study, Jilin Province (representing Northeast China), Shandong Province and Shaanxi Province were selected as the research objects, with the aim of covering the core planting areas of AG in China8. The three producing areas span significantly different temperature zones and exhibit obvious differences in climatic conditions. The selection of samples with significant differences in climate‒soil assemblages is helpful for revealing the regulatory mechanism of environmental factors on the formation of the rhizosphere microbiome and its metabolites in AG.

Studies have shown that AG from different geographical origins has significant quality differences9with regionally derived environmental variations (e.g., soil properties, climatic conditions, and microbial communities) serving as critical determinants of secondary metabolite profiles and pharmacological efficacy in AG. For example, Shuai et al. reported that the ginsenoside content in AG varies significantly across different cultivation regions, with ginsenosides Rg1, Re, Rg3, and Rh2 identified as potential region-dependent chemical markers10. Zhang et al. employed a mid-level-fusion method that combines hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and ultra-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTRAP-MS/MS) techniques to successfully identify the origins of AG11.

Research indicates that variations in geographical settings and the genetic composition of host organisms can significantly influence the compositional diversity of the rhizosphere microbiome12,13. In turn, rhizosphere microbes can also affect plants, for instance, by increasing their adaptability to the environment and increasing the content of active components within the plant14,15. Although the dominant microbial groups in the rhizosphere soil of ginseng from different production areas are the same, their abundance varies16. Moreover, rhizosphere bacteria are closely related to the adaptability of licorice to saline‒alkali soils and the contents of its effective components, namely, glycyrrhizic acid and glycyrrhizin17. Studies have demonstrated a close association between soil microorganisms and plant secondary metabolism. Aerospace mutagenesis increases the abundance of characteristic microorganisms in the rhizosphere soil of tea plants. This enhancement significantly bolsters soil functionality, improving nutrient transformation capacity and increasing the content of bioavailable soil nutrients. Consequently, this process promotes the synthesis of secondary metabolites in tea plants, stimulates growth, and ultimately increases tea leaf yield18. Parallel observations have emerged in medicinal plant research. Multiomics investigations of Codonopsis pilosula have revealed complex interactions between secondary metabolites (including VOCs and terpenoids) and the root-associated microbiome, with specific bacterial taxa implicated in modulating the production of medicinally relevant compounds such as abscisic acid19.

Therefore, elucidating the relationships between rhizosphere microbes and plant metabolites is crucial for optimizing plant growth and secondary metabolism. Although studies have explored the correlation between the quality of AG and soil microbes, research on the metabolites and soil microbial characteristics of AG from Northeast China and Shandong and Shaanxi Provinces remains insufficient.

In this study, AG from Shandong, Jilin, and Shaanxi Provinces were selected as research subjects, with the aim of (1) assessing the metabolic differences in AG from different production areas using metabolomics technology; (2) analyzing the differences in the rhizosphere microbes of AG from different production areas through amplicon sequencing technology; and (3) exploring the correlations between the contents of ginsenosides in AG and the main microbes. The results of this study will establish a theoretical framework for rationally planning AG artificial cultivation zones and optimizing rhizosphere microbiome functionality to enhance the quality of endophytic resources in AG.

Results

Analysis of secondary metabolites in AG from different regions

LC‒MS/MS was used to analyze the metabolites in 18 AG samples from 3 production areas. A total of 1116 metabolites of 13 classes were identified in all the samples, among which amino acids and derivatives (245; L-aspartic acid, D-ornithine, L-glutamine, etc.), terpenoids (153; ginsenoside Rb1, ginsenoside Rd, pseudoginsenoside F11, etc.), phenolic acids (121; 4-caffeoylshikimic acid, gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, 1-O-rutinoside, etc.), alkaloids (112; 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, 2-phenylacetamide, o-carboxyl-5-hydroxytryptamine, etc.) and other compounds (178; D-fructose 6-phosphate, vitamin B2, noreugenin-7-O-glucoside, etc.) accounted for more than 10% of the total metabolites (Fig. 1A).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to examine the intra- and intergroup variations in AG from different origins. The PCA results revealed that the grouping of the samples was reliable. The samples from the three regions had an obvious tendency to separate, suggesting regional disparities in metabolic composition (Fig. 1B).

The main metabolites in AG were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (Fig. 1C). Significant regional variations were observed in the relative contents of metabolites among AG from the three production areas. Nucleotides and derivatives were highly significantly different (P < 0.01), whereas flavonoids, terpenoids, lipids, organic acids, and saccharides were significantly different (P < 0.05). Compared with the JL and SX samples, the SD samples presented significantly greater relative contents of flavonoids, nucleotides and derivatives (P < 0.01). Compared with SX, JL contained a significantly greater lipid content (P < 0.01), with the contents of nucleotides, derivatives and saccharides being significantly greater than those of SX and SD (P < 0.05). Compared with that of JL, the terpenoid content of SX was significantly greater (P < 0.05).

Orthogonal projections of latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was utilized to assess the differences between two groups (JL vs. SD, SX vs. SD, and SX vs. JL). In these three comparisons, the samples were well distinguished, with the Q2 values for all OPLS-DA models exceeding 0.75. The model verification results revealed that the simulated values of the three models were all lower than the actual values, and the intercept of Q2 on the Y-axis was < 0, indicating that the model was stable and reliable (Supplementary Fig. 1). A total of 234 differential metabolites (DMs) in the 3 comparisons were observed employing variable importance in projection (VIP) ≥ 1, P < 0.05 and a fold change (FC) ≥ 2 or FC ≤ 0.5 as the standards. (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1C). The differentially abundant metabolites in the JL vs. SD, SX vs. SD, and SX vs. JL comparisons numbered 127, 147, and 85, respectively, and the DMs mainly included amino acids and derivatives, phenolic acids, flavonoids, lipids and terpenoids (Supplementary Table 2).

Triterpenoid saponins are considered the main active compounds in AG and are closely related to the quality of AG1. A screening of ginsenosides from the total DMs revealed that ginsenoside Rf, zingibroside R1, oleanolic acid-3-O-xylosyl(1→3)glucuronide and ginsenoside Rh2 were highly abundant in SD. The other saponins were highly abundant in SX (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Microbial diversity in the rhizosphere soils of AG plants from different regions

The amplicon sequence variant (ASV) dilution curves tend to flatten as the amount of data increases (Supplementary Fig. 3). The Good’s coverage of each production area exceeded 0.99 (Table 1), indicating that the amount of sequencing data was reasonable and represented the majority of the microbial community information in the samples.

Analyses of both alpha and beta diversity were employed to assess microbial community diversity. We discovered that the Chao1 and Shannon indices of the fungal microbiota of SX were significantly greater than those of SD and JL (P < 0.05). In the bacterial communities, the Shannon index was significantly greater in the JL group than in the SD and SX groups (P < 0.05). The Chao1 index further indicated greater species richness in JL, followed by SD and SX (Table 1).

On the basis of the unweighted UniFrac distance, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed on the fungal and bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil of AG (Fig. 2). The results revealed distinct segregation in the fungal and bacterial community structures in the rhizosphere soils of AG from the three areas of production.

Analysis of bacterial and fungal community composition

The fungal sequences of the AG soil samples were annotated into 5 phyla. The dominant fungal phylum was Ascomycota, accounting for more than 84.19% of all the sequences (Fig. 3A). The top ten fungal genera in the AG soil samples included Cladosporium, Ilyonectria, Linnemannia, Alternaria, Tausonia, Solicoccozyma, Fusarium, Leucoagaricus, and Colletotrichum (Fig. 3C). Among them, the relative abundance of Cladosporium in the SX sample was significantly greater than that in the SD and JL samples, whereas the relative abundances of Fusarium and Alternaria in the SX sample were the lowest. The relative abundances of Solicoccozyma and Linnemannia were greater in the JL sample. Alternaria, Periconia and Colletotrichum were the dominant genera in the SD samples.

The top ten bacterial phyla of the AG soil samples included Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidota, unidentified_Bacteria, Gemmatimonadota, Cyanobacteria, Myxococcota, and Verrucomicrobiota (Fig. 3B). The dominant fungal phyla were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota, accounting for more than 72.19% of all sequences. The top ten bacterial genera in the AG soil samples included Pseudolabrys, unidentified_Rhizobiaceae, Pseudoxanthomonas, Sphingomonas, Flavobacterium, Sphingobium, Phenylobacterium, Bradyrhizobium, Novosphingobium and unidentified_Cyanobacteria (Fig. 3D). The relative abundance of Sphingobium and Pseudoxanthomonas was notably increased in the SX sample compared with the SD and JL samples. Sphingomonas, Bradyrhizobium and unidentified_Cyanobacteria were the dominant genera in the SD samples. Pseudolabrys and Novosphingobium were the dominant genera in the JL sample.

Interactions between differentially abundant metabolites and microbes

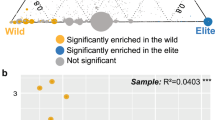

Redundancy analysis (RDA) (Fig. 4) was used to explore the specific effects of the core microbiota at the genus level on the DMs in AG. RDA revealed that axes RDA1 and RDA2 accounted for 33.84% and 18.35% of the variance, respectively. Cumulatively, key microbial genera explained 52.19% of the metabolite variation. The lines of Pseudoxanthomonas, Bradyrhizobium and Alternaria were the longest, indicating that they had the greatest influence on the metabolite variations in AG.

Correlation analysis between the 12 major classes of metabolites in AG and dominant microorganisms revealed that nucleotides and derivatives, terpenoids, and triterpene saponins are notably influenced by microbial activity (Fig. 5A). Nucleotides and derivatives exhibited strong correlations with five core microbes (P < 0.05) and strong correlations with three core microbes (P < 0.01). Terpenoids were strongly associated with six core microbes (P < 0.05) and strongly associated with two core microbes (P < 0.01). Triterpene saponins were strongly correlated with eight core microbes (P < 0.05) and strongly correlated with two additional core microbes (P < 0.01).

Ten bacterial genera presented strong metabolite correlations (Fig. 5B). Bradyrhizobium was negatively correlated with sugars and triterpene saponins but positively correlated with nucleosides. Flavobacterium was strongly positively correlated with terpenoid and triterpene saponins. Phenylobacterium was positively correlated with flavonoids but strongly negatively correlated with sugars. Pseudolabrys exhibited positive lipid correlations but negative associations with terpenoid and triterpene saponins. Pseudoxanthomonas was negatively correlated with nucleotides but strongly positively correlated with terpenes and triterpene saponins. Sphingobium was positively correlated with flavonoids, nucleotides, and organic acids. Unidentified_Cyanobacteria was positively correlated with only flavonoids. Unidentified_Rhizobiaceae was positively correlated with alkaloids, flavonoids, organic acids, terpenes, and triterpene saponins but negatively correlated with lipids. Five fungal genera were strongly correlated with AG metabolites (P < 0.05). Alternaria and Colletotrichum presented positive nucleotide correlations but negative associations with terpenoid and triterpenoid saponins. Fusarium was positively correlated with nucleotide derivatives and organic acids. Ilyonectria presented positive alkaloid but negative lipid correlations. Leucoagaricus was negatively correlated with nucleotides but positively correlated with terpenoid and triterpenoid saponins.

We further compared the relationships between the DMs of saponins and microbes (Fig. 6). Pseudoxanthomonas, Sphingobium, and Bradyrhizobium were strongly positively correlated with most of the saponin DMs (including (PPD-2 H) -Glc -Glc -malonyl, 6′-O-acetyl -ginsenoside Rgl, ginsenoside F1, ginsenoside F2, ginsenoside Rg1, PPT -Glc-Glc-acetyl, sanchirhinoside A4 and yesanchinoside D). Leucoagaricus, Alternaria, Colletotrichum and Fusarium were strongly positively correlated with oleanolic acid -3-O-xylosyl (1→3) glucuronide and ginsenoside Rh2. Flavobacterium was strongly positively correlated with ginsenoside Rf (P < 0.01, r = 0.6930). Zingibroside R1 was strongly positively correlated with Sphingomonas (P < 0.05, r = 0.4757) and unidentified _ Cyanobacteria (P < 0.01, r = 0.7214).

Heatmap of the correlations between major classes of metabolites (A), saponin DMs (B) and core microbes (top 10 bacterial genera and top 10 fungal genera). “*” indicates “P < 0.05”, “**” indicates “P < 0.01”. Red denotes positive correlations, green indicates negative correlations, with color intensity reflecting the strength of the correlation (i.e., magnitude of the correlation coefficient values).

Discussion

Plant growth and developmental processes are significantly modulated by environmental conditions. These ecological drivers govern the biosynthesis and spatial allocation of secondary metabolites across diverse scales6. From a macroecological perspective, bioclimatic variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, solar radiation) substantially shape plant distribution, developmental processes, and adaptive fitness by altering habitat physicochemical properties20. Different species, which exhibit varied adaptations and preferences toward climatic conditions, develop distinct spatial distribution patterns21. Moreover, plant root systems dynamically interact with the soil, facilitating continuous biogeochemical exchange22.

In our study, we systematically analyzed and compared AG roots cultivated from different regions using targeted metabolomics, revealing the diversity in their metabolite profiles. Using PCA and OPLS-DA, we revealed variations in the distribution of metabolites among AG samples from different origins, with significant differences observed, particularly between the SD and SX groups, which presented the greatest number of DMs. Interestingly, the study also revealed significant differences in the microbial community structure between the SD and SX groups. Among the identified metabolites, amino acids and derivatives, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and lipids constituted the majority, which is similar to the findings of Li Rui23. The AG from SD had a relatively high content of phenolic acids, such as chlorogenic acid and cryptochlorogenic acid, which possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities24. The AG from SX had a relatively high content of triterpene saponins, such as ginsenoside Rg1 and ginsenoside F2, which have antifatigue effects and antitumor effects, respectively25,26. The AG from JL is enriched in lipid components, such as lysophosphatidylcholine and oleic acid, which function in regulating lipid metabolism27. Investigating the differences in metabolites among AG from different regions is beneficial for the better development and utilization of AG, and the differentially abundant metabolites identified can also serve as potential chemical markers for assessing ginseng from different production areas.

Rhizosphere microbes are selectively enriched by plants and affect plant metabolism continuously; thus, a strong correlation is noted between rhizosphere microbes and plant metabolites28. The results of this study indicate that although there are differences in the diversity and richness of the rhizosphere soil among ginseng from different regions, the dominant microbial phyla in the three groups of samples are consistent. The dominant microorganisms at the phylum level in the rhizosphere soil of AG were Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Gemmatimonadota, and Bacteroidota, which included Cladosporium, Ilyonectria, Alternaria, Sphingobium, Flavobacterium, and unidentified_Rhizobiaceae. Fusarium is a potential pathogen that causes root rot in AG29. Research has revealed a strong positive correlation between organic acid content and organic acid content in AG, suggesting that organic acids secreted by AG may permeate the soil and subsequently recruit Fusarium30. In this study, fungal microorganisms such as Alternaria, Colletotrichum, and Cladosporium were highly correlated with the contents of terpenoid components and triterpenoid saponins. Alternaria, Cladosporium, and Colletotrichum have also been reported as potential pathogens causing disease in AG31,32. In the present study, Alternaria and Colletotrichum had a negative effect on the accumulation of terpenoids, whereas Cladosporium had a positive effect on the terpenoid content. Sphingobium belongs to Proteobacteria and is considered a potential biomarker of the disease suppressor community33. In this study, we found that the abundance of ginsenoside Rf was strongly positively correlated with a variety of saponins in AG. Flavobacterium is found in the rhizosphere microorganisms of plants such as Panax quinquefolius L., Panax notoginseng, and Panax ginseng34,35,36. Flavobacteriaceae not only promotes plant growth and yield by solubilizing phosphorus, fixing nitrogen, or secreting plant hormones37 but also protects plants from pathogens and improves plant disease resistance38.

In this study, the rhizosphere microbial community of AG was closely related to the content of triterpene saponins in AG. This study revealed strong correlations between Bradyrhizobium, Pseudoxanthomonas, Alternaria, and Colletotrichum and triterpenoid saponin content in AG, which aligns with prior research. For example, Chen et al. demonstrated that biochar treatments modulate key endophytes and rhizosphere microbes to regulate the accumulation of secondary metabolites, including triterpenoid saponins, in AG39. Similarly, Dipsacus asperoides exhibited positive correlations between Dipsacus saponin VI levels and both total endophytic fungal counts and Fusarium sp. abundance40.

However, the relationship between rhizosphere microorganisms and the content of triterpene saponins in AG is complex, as no single microorganism has been found to simultaneously influence the contents of all 12 triterpene saponins, and the effects on different components also differ. For example, the abundance of Bradyrhizobium was strongly negatively correlated with the ginsenoside Rg1 but strongly positively correlated with the ginsenoside Rh2. These findings suggest that complex interactions among rhizosphere microbes collectively influence the contents of metabolites in AG. Thus, whether there is a clear correlation between rhizosphere microbes and AG metabolites needs to be further verified.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and processing

In October 2023, the main roots and rhizosphere soil of AG were collected from major production regions, including Dunhua city, Jilin Province (JL), Wendeng city, Shandong Province (SD), and Liuba city, Shaanxi Province (SX). At each site, six replicate root samples were collected from six plots (10 × 10 m), with each replicate consisting of a composite sample formed by mixing ten individual samples. Large soil clumps were shaken off the roots, and the remaining soil adhering to the root surface (0–2 mm) was gently brushed off to obtain rhizosphere soil41. A total of 18 root samples (6 plots × 3 sites) and 18 soil samples (3 sites × 6 plots) were obtained, and all the samples were collected, transported on dry ice and stored at -80 °C until further experimentation.

Metabolomic analysis

Preparation of the test product solution

The AG samples were freeze-dried and ground into powder using a grinding instrument at 30 Hz for 1.5 min. Then, 50 mg of each powdered sample was dissolved in 1200 µL of precooled (− 20 °C) internal standard extraction solution (70% methanol in water) and vortexed. The mixture was vortexed six times in total (30 s each, at 30-min intervals) and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 3 min. Finally, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane and stored in an injection vial for further analysis.

UPLC and mass spectrometry conditions

Chromatographic separation was performed on a C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) using a gradient of 0.1% formic acid water (solvent A), 0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile (solvent B): 95% B (0–9.00 min); 95–5% B (9.00–14.00 min) at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min, and the injection volume was 2 µL; the column temperature was 40 °C.

The ESI source was operated in both positive and negative ion modes with the following parameters: ion source temperature, 550 °C; ion spray voltage, (IS) 5500 V (positive ion mode)/-4500 V (negative ion mode); ion source gas I (GSI), gas II (GSII) and curtain gas (CUR) were set to 50, 60 and 25 psi, respectively; collision-induced ionization, high; and collision gas (nitrogen), medium.

16 S and ITS rRNA sequencing, sequencing, and processing

Total DNA was extracted from each rhizosphere soil sample using the FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer, and the quality was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA concentrations ranged from 40 to 60 ng/µL, meeting the quality threshold.

The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 27 F (5′-AGRGTTTGATYNTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TASGGHTACCTTGTTASGACTT-3′). The ITS2 region of the fungal rRNA gene was amplified with the primers ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS4R (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). The PCR products were purified, quantified, and used for library preparation. High-throughput sequencing was performed on the Illumina platform (250-bp paired-end reads).

The raw sequence data (fastq files) were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Offline data processing included quality filtering, read merging, and chimera removal to generate high-quality sequences. Denoising was performed using DADA2 (v1.26.0) to obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and their abundance profiles. Taxonomic classification of the bacterial and fungal communities was conducted using the SILVA (v13.2) and UNITE (v8.0) databases, respectively.

Statistical analysis of the metabolome and microbiome

Metabolite profiling (qualitative and quantitative analysis) was conducted using the MWDB database (MetWare Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). All the statistical analyses were performed with R (v 4.2.0). Unsupervised PCA was performed using the base package from R. OPLS-DA were generated using the R package MetaboAnalystR (v1.0.1)42. DMs were identified on the basis of VIP scores from OPLS-DA results and absolute log2-fold change (log2FC) values. The alpha diversity indices (including ASV, Chao1, Shannon, and Good’s coverage) were computed using the R packages phyloseq (v1.40.0) and vegan (v2.6.2). The R package phyloseq (v1.40.0) was also used to calculate the beta diversity on the basis of unweighted UniFrac distances and map the PCoA. The Circos plots were visualized using the ggplot2 package from R. Spearman’s correlation analysis between fungal and bacterial genera (screened at the genus level) and metabolites was performed using the Corrplot package (v0.92), with the results visualized as a heatmap43. RDA was performed using CANOCO (v5.15)44.

Conclusions

The AG samples presented distinct regional metabolite profiles. The SD samples were rich in flavonoids, nucleotides, and organic acids. The JL samples were high in lipids, nucleotides, and saccharides. The SX samples were enriched in terpenoids. The microbial compositions of the rhizosphere also varied significantly by region. Importantly, key microbes (Pseudoxanthomonas, Sphingobium, and Bradyrhizobium) presented strong positive correlations with major triterpene saponin metabolites. These findings enable the targeted utilization of rhizosphere microbial resources to increase AG quality.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI with the primary accession codes PRJNA1199721 and PRJNA1199877.

Abbreviations

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- OPLS-DA:

-

Orthogonal projections of latent structures discriminant analysis

- DMs:

-

Differential metabolites

- PCoA:

-

principal coordinate analysis

- RDA:

-

Redundancy analysis

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ASV:

-

Amplicon sequence variant

- ASVs:

-

Amplicon sequence variants

- VIP:

-

Variable importance in projection

- FC:

-

Fold change

References

Yang, Z. et al. A review for discovering bioactive minor saponins and biotransformative metabolites in Panax quinquefolius L. Front. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.972813 (2022).

Qi, B. et al. Anti-fatigue effects of proteins isolated from Panax quinquefolium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 153 (2), 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.045 (2014).

Edens, R. et al. Exploring the use of Panaxynol from American ginseng to combat intestinal inflammation and colon cancer. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 327 (2), G120–G122. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00135.2024 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Non-destructive geographical traceability of American ginseng using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with a novel deep learning model. J. Food Compos. Anal. 136, 106736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106736 (2024).

Wu, S. et al. Research progress on chemical constituents, biological activities, quality evaluation, and product development of Panax quinquefolium. Acta Pharm. Sinica. 57 (6), 1711–1725. https://doi.org/10.16438/j.0513-4870.2021-1720 (2022).

Tian, L. et al. A systematic review of ginsenoside biosynthesis, Spatiotemporal distribution, and response to biotic and abiotic factors in American ginseng. Food Funct. 15 (5), 2343–2365. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3FO03434H (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Panacis quinquefolii radix: A review of the botany, phytochemistry, quality control, pharmacology, toxicology and industrial applications research progress. Front. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.602092 (2020).

Liao, D. et al. Quality evaluation of Panax quinquefolium from different cultivation regions based on their ginsenoside content and radioprotective effects on irradiated mice. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 1079. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37959-9 (2019).

Pang, S. et al. Discrimination for geographical origin of Panax quinquefolius L. using UPLC Q-Orbitrap MS-based metabolomics approach. Food Sci. Nutr. 11 (8), 4843–4852. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3461 (2023).

Shuai, M. et al. Geographical origin of American ginseng (Panax Quinquefolius L.) based on chemical composition combined with chemometric. J. Chromatogr. A. 1676, 463284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463284 (2022).

Zhang, Z. A. et al. Chemical analysis of mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves treated with jasmonates on nutrition composition and biological activity. Food Chem. 489, 144929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144929 (2025).

Trivedi, P. et al. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18 (11), 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1 (2020).

Zhalnina, K. et al. Soil pH determines microbial diversity and composition in the park grass experiment. Microb. Ecol. 69 (2), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0530-2 (2015).

Bhattacharyya, P. N. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28 (4), 1327–1350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9 (2012).

Yu, J. B. et al. Regulation of secondary metabolites accumulation in medicinal plants by rhizospheric and endophytic microorganisms. M 3(1). https://doi.org/10.48130/mpb-0024-0011 (2024).

He, C. et al. Effects of cultivation soils and ages on Microbiome in the rhizosphere soil of Panax ginseng. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 174, 104397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104397 (2022).

Bao, Y. et al. The impact of salinization on soil bacterial diversity, yield and quality of glycyrrhiza uralensis fisch. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1448301 (2024).

Cheng, W. et al. Aerospace mutagenized tea tree increases rhizospheric microorganisms, enhances nutrient conversion capacity and promotes growth. Plants 14 (7), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14070981 (2025).

Gao, Z. et al. Integrating transcriptome, metabolome and Microbiome to explore the interaction mechanism between secondary metabolites and root-associated bacteria of Codonopsis pilosula. Ind. Crops Prod. 227, 120790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.120790 (2025).

Tang, X. et al. Maximum entropy modeling to predict the impact of climate change on pine wilt disease in China. Front. Plant. Sci. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.652500 (2021).

Razgour, O. et al. An integrated framework to identify wildlife populations under threat from climate change. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18 (1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12694 (2018).

Hu, C. et al. Estimating the spatial distribution of soil properties using environmental variables at a catchment scale in the loess hilly area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (3), 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030491 (2019).

Li, R. et al. Diversity and correlation analysis of endophytes and metabolites of Panax quinquefolius L. in various tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 23 (1), 275. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04282-z (2023).

Jiao, H. et al. Chlorogenic acid alleviate kidney fibrosis through regulating TLR4/NF-қB mediated oxidative stress and inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 335, 118693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2024.118693 (2024).

Tan, X. et al. A large-scale transcriptional analysis reveals herb-derived ginsenoside F2 suppressing hepatocellular carcinoma via inhibiting STAT3. Phytomedicine 120, 155031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155031 (2023).

Lei, C. et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 can reverse fatigue behavior in CFS rats by regulating EGFR and affecting taurine and mannose 6-phosphate metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1163638 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Study on the mechanism of American ginseng extract for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus based on metabolomics. Front. Pharmacol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.960050 (2022).

Chamkhi, I. et al. Is—the rhizosphere a source of applicable multi-beneficial microorganisms for plant enhancement? Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29 (2), 1246–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.032 (2022).

Fan, S. et al. American ginseng root rot caused by fusarium redolens in China. Plant Dis. 105 (9), 2734. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-12-20-2600-PDN (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. P-hydroxybenzoic acid positively affect the Fusarium oxysporum to stimulate root rot in Panax Notoginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 48 (2), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2023.11.005 (2024).

Guan, Y. M. et al. First report of anthracnose of American ginseng caused by Colletotrichum Sojae in Northeast China. Plant Dis. 105 (11), 3755. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-11-20-2440-PDN (2021).

Qiu, C. et al. Genome resource of American ginseng black spot pathogen alternaria Panax. Plant Dis. 106 (3), 1020–1022. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-05-21-0895-A (2022).

Fu, L. et al. Inducing the rhizosphere Microbiome by biofertilizer application to suppress banana fusarium wilt disease. Soil Biol. Biochem. 104, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.10.008 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Soil microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals beneficial effects of ginseng–celandine rotation on the rhizosphere soil of ginseng-used fields. Rhizosphere 23, 100559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2022.100559 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Root rot induces a core assemblage of bacterial microbiome to prevent disease infection in Sanqi ginseng. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 198, 105371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105371 (2024).

Chang, F. et al. Effects of American ginseng cultivation on bacterial community structure and responses of soil nutrients in different ecological niches. 32 (4), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2202.02003 (2022).

Seo, H. et al. The plant-associated Flavobacterium: A hidden helper for improving plant health. Plant. Pathol. J. 40 (3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.RW.01.2024.0019 (2024).

Kwak, M. J. et al. Rhizosphere microbiome structure alters to enable wilt resistance in tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 36 (11), 1117–1117. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1118-1117 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Biochar-induced microbial and metabolic reprogramming enhances bioactive compound accumulation in Panax quinquefolius L. BMC Plant. Biol. 25 (1), 669. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06656-x (2025).

Gong, A. et al. Association between dipsacus saponin VI level and diversity of endophytic fungi in roots of dipsacus Asperoides. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35 (3), 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-019-2616-y (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. The accumulation of active ingredients of polygonatum Cyrtonema Hua is associated with soil characteristics and bacterial community. Front. Microbiol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1347204 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Revealing ecotype influences on Cistanche sinensis: from the perspective of endophytes to metabolites characteristics. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1154688 (2023).

Leng, F. et al. Characterization of root microbial communities associated with Astragalus membranaceus and their correlation with soil environmental factors. Rhizosphere. 25, 100656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2022.100656 (2023).

Braak, C. J. F. et al. Canoco reference manual and user’s guide: software for ordination, version 5.0. (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the local farmers for their kind participation and dedication. Furthermore, we are grateful to the School of Chinese Materia Medica, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, for providing the basic experimental conditions.

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding from the China Environmental Protection Foundation under Grant Agreement No. CEPFQS202169-19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Y.L.: Writing-review and editing, writing-revision draft, writing-revision draft review and editing. X.T.: Data curation, software, writing-review and editing. Y.G.: Methodology, writing-review and editing. Y.X.: Writing-review and editing. M.P.: Writing-review and editing. Z.Z.: Funding acquisition, project administration, conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, L., Li, Y., Tian, X. et al. Shaping of the core microbiome by ginsenosides in American ginseng across diverse habitats. Sci Rep 15, 35702 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19479-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19479-5