Abstract

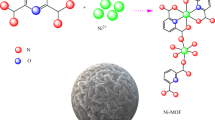

This study presents the synthesis and characterization of a Co–Ni anchored magnetic mesoporous silica hollow sphere as an efficient and eco-friendly nanocatalyst for the preparation of 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives. The hollow and mesoporous architecture of the catalyst provides a large active surface area, enhancing its catalytic performance. The synergistic interaction between cobalt and nickel on the catalyst surface significantly improves its efficiency. The catalyst was thoroughly characterized using FT-IR, XRD, FE-SEM, TEM, EDS, elemental mapping, BET, ICP-OES and VSM techniques. Its magnetic properties facilitate easy separation and recyclability, with minimal loss of activity over multiple cycles. The nanocatalyst was applied in a solvent-free, three-component reaction involving triethyl orthoformate, sodium azide, and aromatic amines at 80 °C, affording the desired 1-substituted tetrazole derivatives in excellent yields (up to 98%). Reaction parameters, including catalyst loading, temperature, and solvent effects were optimized. Additionally, the obtained tetrazole derivatives were identified by their melting points, FT-IR, 1H NMR and 13C NMR analyses. The key advantages of this catalytic system include its reusability, high efficiency under mild conditions, short reaction times, and production of pure products in high yields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tetrazoles are a crucial group of organic compounds that contain nitrogen atoms. They are identified by their five-membered heterocyclic structure, which consists of four nitrogen atoms and one carbon atom. These heterocyclic compounds have various applications in industry, agriculture, and pharmaceuticals1,2. They are used to produce pesticides and herbicides; they are also utilized as explosives and propellants in rocket fuel, and they play a role in some chemical analysis reagents and sensors3,4,5,6,7. Figure 1 displays several drug molecules that contain tetrazole heterocyclic rings. Losartan is used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension). This medication may be prescribed alone or in combination with other drugs to lower the risk of stroke in individuals with hypertension8. Valsartan is an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) prescribed for managing high blood pressure, heart failure, and diabetic kidney disease9. Also, Olmesartan medoxomil, Candesartan, and Candesartan cilexetil have the same medical applications as the previous compounds. Picarbutrazox is a new fungicide developed for crops such as cereals10. Pranlukast is a leukotriene cysteinyl-1 receptor antagonist used to treat asthma and allergy symptoms11. The molecule MBX-2982 affects the level of SREBP-1 proteins in HepG2 cells and is currently in the testing stage12. Oteseconazole is an emerging antifungal medication from the azole class, designed primarily to lower the risk of fungal or yeast infections, particularly vaginal candidiasis, commonly affecting female patients 13.

There are various methods for synthesizing tetrazole derivatives, each with its advantages and disadvantages. One standard method is [2 + 3] cycloaddition reactions. In this method, nitriles and sodium azide are used as raw materials, and it is widely employed due to its simplicity and high efficiency. Sinha et al. have synthesized 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles by preparing a cobalt (II) complex with a tetradentate ligand N,N-bis (pyridin-2-ylmethyl) quinoline-8-amine, and using nitrile derivatives in the presence of sodium azide. For the first time, they used this type of cobalt complex for a [2 + 3] cycloaddition reaction to synthesize 1H-tetrazoles14. Safari et al. have synthesized tetrazole derivatives from N-aryl cyanamides and sodium azide using CuO-NiO-ZnO with ultrasonic and thermal methods15.

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) are also an effective way to synthesize tetrazoles and various heterocycles16,17. Recent developments in nanocatalysts and multicomponent techniques have made the outlook for tetrazole synthesis appear promising. These approaches can decrease production time and costs by allowing multiple reactions to be performed simultaneously in a single step.

Hajra et al. synthesized 1-substituted-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives under solvent-free conditions in one pot using indium triflate. They used amine, trimethyl orthoformate, and sodium azide as precursors for the synthesis of the tetrazoles18. Gómez et al. enhanced the ultrasound-assisted eco-friendly synthesis of 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazoles using isocyanide-based multicomponent click reactions. They obtained yields ranging from good to excellent (71–97%) in reduced reaction times19. In another study, Mashhoori et al. synthesized two different types of tetrazole derivatives by using Schiff base coordinated with Cu(II), which was covalently attached to Fe3O4@SiO2 nanospheres via an imidazolium linker [Fe3O4@SiO2-Im(Br)-SB-Cu(II)]. They prepared various 1-substituted 1H-tetrazole derivatives using aniline, triethyl orthoformate, and sodium azide in water solvent. They successfully synthesized 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles with good yield in aqueous solution, using different aromatic aldehyde derivatives, hydroxylammonium chloride, and sodium azide. They proposed that the reaction takes place through a [3 + 2] cycloaddition mechanism20.

Multicomponent methods and cycloaddition reactions are typically straightforward, rapid, and require no complex steps. The use of nanocatalysts, especially iron, cobalt, and nickel nanoparticles, is essential in the synthesis of tetrazoles. These nanocatalysts have many advantages due to their high active surface area and recyclability.

Over the past few years, many studies have been conducted on the design, preparation, and characterization of catalysts21,22,23 .They facilitate chemical reactions to occur under milder conditions and with greater efficiency without undergoing consumption themselves24,25. These materials are pivotal in many industrial, chemical, and biological processes26,27,28. Furthermore, catalysts reduce the activation energy and time of the reaction, optimize energy consumption, and enhance productivity29,30,31. Catalysts are used in many industrial processes, including producing chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals32,33,34. Due to their nanoscale size and exceptionally high active surface area, nanocatalysts exhibit extraordinary catalytic performance. These materials demonstrate higher efficiency and selectivity in chemical reactions than conventional catalysts35,36.

Moreover, the porous and hollow nanostructures provide precise control over reaction environments and offer a significantly increased density of active catalytic sites37,38,39. These distinctive properties render nanocatalysts highly promising for various applications, including energy conversion and environmental remediation40. Also, the hollow nanostructures are a class of advanced catalytic materials characterized by their unique hollow or porous architectures, such as hollow spheres, nanotubes, or porous frameworks41,42. These structures offer a high surface-to-volume ratio, enhanced mass transfer, and improved performance in various applications, including catalysis, energy storage, drug delivery, and environmental remediation43.

Hollow spherical structures can exist in single-layer or multi-layer cylindrical, cubic, or spherical shapes. They are classified into three types: monolayer spheres, multilayer spheres, and yolk shells. These hollow spheres find extensive applications in drug delivery, biosensors, catalysts, and batteries44. Many catalytic reactions have utilized hollow spherical structures. Their high contact surface area makes them ideal substrates for positioning nanoparticles45,46.

Magnetic catalysts are a class of advanced catalytic materials that leverage their inherent magnetic properties to enable easy recovery and reuse47,48. This unique characteristic significantly reduces operational costs and enhances the overall efficiency of catalytic processes49. Typically, magnetic catalysts consist of magnetic nanoparticles, such as iron oxide (Fe3O4), which are combined with other catalytic materials, including noble metals (platinum, gold, e.g.) or metal oxides50,51. This combination results in highly efficient catalysts that not only exhibit superior catalytic performance but also offer the added advantage of straightforward separation and recyclability, making them highly attractive for diverse industrial and environmental applications28,29.

On the other hand, bimetallic catalysts, composed of two different metals, are one of the most advanced and efficient types of catalysts52,53,54. These catalysts are widely utilized in complex processes, including hydrogenation, chemical synthesis, and hydrocarbon decomposition. Their varied compositions, adjustable activities, high selectivity, and reliable stability across different operating conditions contribute to their broad applicability29. Additionally, by adjusting the metal ratio and designing an appropriate structure, the bimetallic catalysts can significantly enhance their resistance to phenomena such as poisoning or sintering22. Due to environmental challenges and the necessity for sustainable technologies, bimetallic catalysts are recognized as essential components in creating modern chemical processes, and research in this field is continually growing55.

This research introduces a new catalyst designed for synthesizing tetrazole derivatives. Our goal is to develop a highly efficient, eco-friendly, and cost-effective method that overcomes the issues of traditional techniques. This work demonstrates the potential of the proposed catalyst to promote sustainable chemical synthesis, highlighting its importance in both academic and industrial settings.

Experimental

Materials and apparatus

All raw materials and solvents used in this research were of the highest quality and purity, obtained from Merck, Fluka, and Sigma-Aldrich chemical companies. The reaction process was accomplished with thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 F254 plates. The melting points of the synthesized organic compounds were determined using the Thermo Scientific 9200. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded as potassium bromide (KBr) pellets on a Nicolet IMPACT-400 FT-IR spectrophotometer at room temperature in the 4000 and 400 cm−1 range. Proton and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR and 13C NMR) were recorded in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 solvents with trimethylsilane (TMS) as the internal reference using a Bruker DRX-400 spectrometer to determine the samples’ molecular structure and purity. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded by Panalytical X’Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer using the standard CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). The BELSORP-mini II apparatus (Microtrac BEL, Japan) was used to calculate nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and BJH plots at 77 K. Additionally, the magnetic characteristics of the nanocatalyst were investigated using a vibrating sample magnetometer (model VSM 7300, Meghnatis Daghigh Kavir Co., Kashan, Iran) with an applied magnetic field of 15 kOe. This study investigated the surface morphology and local chemical element determination using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) on the Mira 3-XMU apparatus, operating at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

General procedure for preparation of Co–Ni anchored on magnetic mesoporous silica hollow spheres (Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS)

Preparation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles

An ultrasound bath was used to dissolve FeCl3·6H2O (35.55 mmol, 9.60 g) and FeCl2·4H2O (20.20 mmol, 4.00 g) in 90 mL of deionized water. The solution was placed in a 250 mL round-bottom flask, purged with nitrogen gas, and stirred mechanically for 30 min. The solution’s temperature was increased to 90 °C and stirred for an additional 30 min using a mechanical stirrer. 24 mL of 30% ammonia was added to the solution dropwise over 15 min. After 2 h, the reaction was completed, and the solution temperature was allowed to return to ambient temperature. Then, the nanoparticles were separated using an external magnet, and the residue was washed several times with deionized water. The magnetic nanoparticles were dried at 60 °C for 8 h and then placed in a sealed container for future use in subsequent steps.

Preparation of carbon spheres

D-glucose (66.66 mmol, 12.0 g) was dissolved in 80 mL of deionized water to obtain a clear solution. The solution was transferred to a 300 mL Teflon-lined steel autoclave and heated to 180 °C for 5 h. After completing the hydrothermal process, the autoclave was allowed to return to ambient temperature. The contents were then separated using a centrifuge set at 5500 rpm for 5 min and washed several times with deionized water and ethanol. The carbon spheres were dried overnight at 60 °C and then stored.

Preparation of Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres

A 160 mL solution of hydrochloric acid with a pH of 2.3 was prepared, and then Fe3O4 nanoparticles (5.19 mmol, 1.20 g) were added and thoroughly stirred to obtain a homogeneous solution (Solution A). Next, 2 g of carbon spheres were added to 120 mL of a hydrochloric acid solution with a pH of 2.3, which had been prepared in another container and stirred thoroughly (Solution B). Solutions A and B were slowly mixed and stirred vigorously for 6 h. The magnetic carbon spheres were collected using an external magnet and thoroughly washed with deionized water. The magnetic carbon nanospheres (Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres) were dried at 50 °C for 12 h.

Preparation of Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres

In 60 mL of deionized water, CoCl2·6H2O (0.04 mmol, 0.01 g) and NiCl2·6H2O (0.04 mmol, 0.01 g) were added, and the mixture was sonicated for 10 min. The prepared solution from the previous step was slowly added to a solution containing 300 mg of Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres and 50 mL of well-dispersed deionized water. The mixture was then stirred for 10 h using a mechanical stirrer. The Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres were separated from the reaction medium using an external magnet, thoroughly rinsed multiple times with deionized water and ethanol, and dried at 50 °C for 12 h.

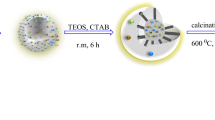

Preparation of Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS

Magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with nickel and cobalt (Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres) were dispersed in 80 mL of deionized water. Then, 60 mL of ethanol, 2 mL of ammonia (30%), and CTAB (0.82 mmol, 0.30 g) were mixed, slowly added to the previously prepared solution, and stirred with a mechanical stirrer for 10 min. The TEOS (1.81 mmol, 0.40 mL) was added to the solution. After 6 h, the nanoparticles covered with silica were separated by an external magnet and washed several times with deionized water and ethanol. The nanoparticles were dried at 50 °C for 12 h, then transferred to a furnace set at 700 °C for 5 h to eliminate the carbon template.

General procedure for the synthesis of 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask, 6 mg of Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst, triethyl orthoformate (1.2 mmol, 1.99 mL), sodium azide (1 mmol, 0.065 g), and aromatic amine (1 mmol) were placed under solvent-free conditions. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for the time indicated in Table 3. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was used to monitor the reaction process. After the end of the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and then diluted with 25 mL of ethyl acetate. Then, the external magnet was used to remove the catalyst. The separated catalyst was washed twice with distilled water and methanol for reuse and dried at 50 °C for 6 h. The resulting sediments were separated from the reaction medium using filter paper. The filtered solution was added to 20 mL of 5 N HCl and mixed. A separatory funnel was then used to separate the organic layer. Then, the organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified through recrystallization from ethanol to form the pure product. The melting points, FT-IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR were utilized to identify the products, and the results were validated.

Spectroscopic and physical data

The FT-IR and NMR spectra of all synthesized compounds are included in the Supplementary Information file (Supplementary Figs. S1–S27).

1-Phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4a); Yellow solid; m.p.: 63–66 °C (Lit. m.p.: 64–65 °C)56; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3050, 1678, 1584, 1488, 757, 696 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.08–7.11 (m, 3H), 7.32–7.34 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.22 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4b); White solid; m.p.: 156–158 °C (Lit. m.p.: 157–158 °C)57; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3152, 1661, 1580, 1485, 829 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.98 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.28 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.08 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Bromophenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4c); White solid; m.p.: 176–178 °C (Lit. m.p.:183–185 °C)58; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3181, 3123, 1697, 1489, 1352, 820 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMS0-d6) δ (ppm): 7.51 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.65 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 9.01 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Methyl phenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4d); Yellow solid; m.p.: 93–95 °C (Lit. m.p.:94–95 °C)57; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3432, 1668, 1505, 1311, 815 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMS0-d6) δ (ppm): 2.31 (s, 3H), 7.01 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.16 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.17 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4e); Yellow solid; m.p.: 113–115 °C (Lit. m.p.: 114–115 °C)57; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3136, 1672, 1503, 1463, 829 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 3.80 (s, 3H), 6.86 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.00 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.05 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Ethylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4f.); White solid; m.p.: 76–78 °C (Lit. m.p.: 77–78 °C)59; FT-IR (KBr): v = 2960, 1662, 1504, 1309, 827 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.99 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.16 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.17 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4g); Cream solid; m.p.: 108–110 °C (Lit. m.p.: 108–110 °C)59; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3088, 1681, 1525, 1427, 875, 737, 673 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.53 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.99 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.06 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.91 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4h); White solid; m.p.: 127–131 °C (Lit. m.p.: 127–131 °C)56; FT-IR (KBr): v = 2995, 1664, 1585, 1501, 1473, 751 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.06–7.08 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.99 (m, 2H), 7.43 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.12 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(4-Chloro-2-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazole (4i); White solid; m.p.: 153–155 °C (New compound); FT-IR (KBr): v = 3356, 1635, 1503, 1407, 818, 723 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.08 (s, 1H), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.32 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.13 (s, 1H tetrazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3); 143.2, 135.9, 130.4, 127.8, 125.3, 121.5, 120.0.

1-(3-Chloro-4-fluorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4j); Orange solid; m.p.: 95–97 °C (Lit. m.p.: 95–97 °C)60; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3169, 1665, 1592, 1491, 889, 822, 760, 689 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.93 (s, 1H), 7.09–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.98 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(3-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4k); White solid; m.p.: 95–96 ºC (Lit. m.p.: 95–96 ºC)57; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3000, 2911, 1663, 1578, 1455, 857, 773, 657 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.97 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.09 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.13–7.15 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.95 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(2,4-Dimethylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4l); White solid; m.p.: 133–135 °C (Lit. m.p.: 133–135 °C)58; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3009, 2916, 1664, 1494, 1301, 812 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 2.26 (s, 1H), 6.99 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.11 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.98 (s, 1H tetrazole).

1-(Naphthalene-1-yl)-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4m); White solid; m.p.:181–183 °C (Lit. m.p.; 181–183 °C)58; FT-IR (KBr): v = 3047, 1659, 1573, 1458, 767 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.23 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.43–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.66 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.86 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.22 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H tetrazole).

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst

The catalyst was prepared through five key steps, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In the first step, glucose was used to synthesize carbon spheres through the hydrothermal method. These spheres serve as the main template for the nanocatalyst. In the second step, Fe3O4 nanoparticles were applied to magnetize the carbon spheres. In the third step, cobalt and nickel were coated onto the surface of magnetic carbon nanospheres. Using cobalt and nickel metals together in the catalyst structure as active sites created a synergistic effect, improving catalyst efficiency. In the fourth stage, a layer of silica and a surfactant (CTAB) covers the surface of the template. Finally, during the thermal treatment, both the carbon template and surfactant decompose, leading to the formation of a mesoporous hollow sphere structure. The nanocatalyst was characterized using several techniques, including FT-IR, XRD, FE-SEM, EDS, elemental mapping, BET, TEM, ICP-OES, and VSM, to confirm its successful synthesis and desired properties.

Figure 3 shows the FT-IR spectra of the carbon spheres, Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres, Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres, SiO2@Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres, and Co–Ni/Fe3O4 @MMSHS. Figure 3a shows a peak observed at around 1300 cm−1, related to the stretching vibrations of the carbon–oxygen (C–O) bond. The absorption peaks observed at 1627 cm−1 and 1383 cm−1 are related to the aromatic rings formed during polymerization. The absorption peak at 1712 cm−1 is due to the stretching vibration of the ketone carbonyl group in the polymerized glucose structure61.

The peaks observed at 2923 cm−1 and 2871 cm−1 are related to the asymmetric stretching and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C-H sp3 bonds. The peak at 3441 cm−1, associated with the stretching vibration of the O–H bond, indicates the presence of alcohol groups in the carbon sphere structure. Figure 3b shows the spectrum of magnetic carbon spheres, which confirms the binding of Fe3O4 nanoparticles to the surface of the carbon spheres. The absorption peaks at 534 cm−1 and 451 cm−1 are associated with the Fe–O stretching vibration band. The FT-IR spectrum in Fig. 3c shows that the absorption peaks observed at 593 cm-1 and 470 cm−1 are related to Co–O and Ni–O, respectively.

Figure 3d shows that the absorption peaks at 1071 cm−1 and 964 cm−1 are related to Si–O–Si and Si–OH, which indicates SiO2 on the nanocatalyst’s surface. Due to the presence of CTAB’s carbon chain as a surfactant in the nanocatalyst’s structure, the intensity of the peaks associated with stretching vibrations of C-H sp3 in the 2918 cm−1 and 2852 cm−1 region increases.

Finally, Fig. 3e displays the calcination process of the nanocatalyst Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS. In this spectrum, all peaks associated with the organic substances from the previous stage have vanished, indicating the successful formation of a mesoporous hollow structure.

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of carbon spheres, Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres, Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanospheres, SiO2@Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanosphere, and Co–Ni/Fe3O4@ MMSHS. As shown in Fig. 4a, the XRD patterns of the synthesized carbon spheres display a broad peak at 2θ = 22°, indicative of their amorphous structure.

Figure 4b displays the XRD patterns of carbon spheres after magnetization. The reduction of the observed amorphous pattern results from coating the carbon sphere’s surface with Fe3O4 nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 4c, adding the cobalt and nickel on the surface of the magnetic carbon spheres increases the structural crystallinity and eliminates the observed amorphous pattern. The XRD diffraction analysis, by JCPDS standards 01-086-2267 and 00-022-1086, confirms the presence of cobalt and nickel nanoparticles in the composite structure. Figure 3d shows the pattern of the silica coating on the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@carbon nanocatalyst. An indistinct peak at 2θ = 25° suggests a silica layer on the catalyst’s surface, confirming the effectiveness of the coating process. Finally, the Fig. 4e presents the XRD pattern of the nanocatalyst after calcination. Removing the carbon template and surfactant from the silica wall of the mesoporous hollow sphere nanocatalyst increases the material’s crystallinity, eliminating the amorphous pattern observed in the previous step.

Table 1 displays the Miller numbers and nanoparticle sizes calculated using the Debye-Scherer formula. It indicates that the average size of nanoparticles on the silica substrate, which act as active sites, is 13 nm.

The field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) technique was used to examine the morphology of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst. The images displayed in Fig. 5a and b are at magnifications of 200 and 500 nm. Figure 5a clearly shows the nanocatalyst’s spherical morphology, while Fig. 5b illustrates the hollowness of the spheres. The catalyst’s hollow structure enhances the specific contact surface, increasing interaction between the raw materials and active sites. This matter results in reduced reaction time and improved efficiency. In image 5b, the wall thickness is measured at 81 nm, which has enhanced the mechanical and physical resistance of the nanocatalyst. Furthermore, the TEM image in Fig. 5c clearly displays the catalyst’s walls and hollow spaces, along with the uniform dispersion of metal nanoparticles that act as active sites.

The histogram shown in Fig. 6 depicts the size distribution of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst. The average size of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS was found to be 388 nm, accompanied by a standard deviation of 95.05 nm.

The energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) technique was used to analyze the percentage of constituent elements in the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst, as shown in Fig. 7. This analysis indicates that approximately 12.07% of the carbon is retained in the structure, which can be due to the organic carbon that remains after calcination. The reported percentage of silicon is 14.52%, related to the silica wall of hollow nanospheres. Furthermore, the measured weight percentages for Fe, Co, and Ni were 22.32%, 0.39%, and 0.12%, respectively. Approximately 50.58% of the sample’s weight is composed of oxygen.

The elemental mapping analysis was conducted to examine the dispersion of elements in the prepared catalyst, and the results are displayed in Fig. 8.

The collected data indicate a suitable distribution of O, Ni, Si, Co, Fe elements across the nanocatalyst. The uniform dispersion of nanoparticles as catalytic active sites boosts the effectiveness of nanocatalysts, ensuring reliable catalytic performance across the entire surface.

In Fig. 9, the specific surface area and pore size distribution of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst were measured using Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis with a nitrogen gas adsorption–desorption technique at 77 K. The BET plot (Fig. 9a) shows that the nanocatalyst’s specific surface area and total pore volume are 204.83 m2/g and 0.1434 cm3/g, respectively. The Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst exhibits type IV adsorption–desorption isotherms according to the IUPAC classification in Fig. 9b. This nanocatalyst displays a hysteresis type H4, characteristic of hollow and mesoporous silica spheres. As shown in Fig. 9c, based on the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method, the pore radius was calculated to be 1.21 nm, and the pore area was estimated to be 18.68 m2/g. The results indicate a larger surface contact area for the catalyst, resulting in enhanced efficiency and shorter reaction times in this work.

Figure 10 presents the vibrating-sample magnetometry (VSM) analysis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles (10a) and the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst (10b) at room temperature. According to Fig. 10a, the magnetic property of the synthesized Fe3O4 nanoparticles was measured to be 63.60 emu/g. After coating the silica layer on the carbon template and calcining it, the magnetic properties of the nanocatalyst were measured at 24.51 emu/g. As a result, the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst can be easily separated from the reaction medium using an external magnet and can be reused after washing.

Evaluation of catalytic activity

The reaction for synthesis of 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4a) was chosen as a model reaction to optimize the reaction conditions. In this synthesis, triethyl orthoformate, sodium azide, and aniline react together in the presence of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst. This optimization process examined the effects of solvent type, temperature, and catalyst amount in the reaction. According to the data in Table 2, the reaction yield under solvent-free conditions, at a temperature of 100 °C, and in the absence of a catalyst, the product yield was very low (Entry 1). Next, the reaction efficiency was examined in different solvents while keeping the reaction time, catalyst amount, and the constant temperature (Entries 2–8 in Table 2). Data indicated that the reaction under solvent-free conditions (Entry 5) resulted in a higher yield; therefore, solvent-free conditions was selected for the best reaction condition. According to entries 9 and 10, by increasing the amount of catalyst to 6 mg, the reaction yield increased, and the reaction showed the same yields at two temperatures of 100 and 80 °C. Reducing the reaction temperature led to a lower product yield (Entries 11 and 12). According to the data in Table 2, the optimal conditions were determined to be solvent-free at a temperature of 80 °C, utilizing 6 mg of Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst (Entry 15).

To investigate the synergistic effect of metals in the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst, the synthesis of 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4a) was chosen as a model reaction under optimized conditions. Based on the information presented in Fig. 11, the mesoporous silica hollow spheres that act as a catalyst substrate without metals did not show any catalytic effect. Fe3O4 nanoparticles on mesoporous silica hollow spheres can act as Lewis acids. The results indicated a 26% yield in the synthesis of 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole. The nickel and cobalt nanoparticles were placed on the surface of magnetic mesoporous silica hollow spheres for investigation. When nickel and cobalt were separately stabilized on the surface of magnetic mesoporous silica hollow spheres, they achieved yields of 62% and 79% for the 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole as product, respectively. In conclusion, the results demonstrated that the combined presence of nickel and cobalt nanoparticles on the surface of magnetic mesoporous silica hollow spheres had a beneficial synergistic effect, significantly enhancing the efficiency of the reaction.

The synthetic results of 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives using Co–Ni/Fe3O4@ MMSHS as a nanocatalyst after optimizing the reaction conditions are shown in Table 3. The synthesis of 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives was achieved using aniline with various substitutions. The anilines used in this research contain different electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups. Table 3 shows that the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst efficiently produced the 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives in high yields at the shortest time. Furthermore, research on the effects of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents showed that the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst exhibits outstanding performance for both categories, achieving a high yield.

Table 4 compares the prepared catalyst with other reported catalysts for the synthesis of 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4a). The results show that the reaction time for the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst is lower than that of all the other catalysts. It was demonstrated a high yield at temperatures above 80 °C, while the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst successfully produced the 1-phenyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole (4a) at temperature of 80 °C, achieving higher yield and lower reaction time (Table 4, entries 2–5 vs. 6). The catalysts in entries 1–5 are functionalized with organic groups, making them vulnerable at higher temperatures and reducing the recovery cycle.

Proposed reaction mechanism

Scheme 1 illustrates the proposed mechanism63 for the synthesis of 1-substituted 1H-tetrazole from triethyl orthoformate, sodium azide, and an aromatic amine by using Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS as a catalyst. In this reaction, cobalt and nickel nanoparticles act as active sites, and all processes occur on their surfaces. These nanoparticles can chelate with the raw materials involved in the reaction, thereby activating them and improving the reaction’s speed and efficiency. In the first step, the oxygen atom of the ethoxy group chelates to the catalyst’s active site. Then, the azide anion attacks the central carbon atom of the triethyl orthoformate, removing the chelated ethoxy group with catalyst, and creates an intermediate I. In the next step, the amine group attacks the central carbon of intermediate I, removing the ethoxy group with the aid of a catalyst to form intermediate II. Next, with the assistance of a catalyst, the intramolecular cyclization occurs on intermediate II, resulting in the formation of intermediate III. In the end, the last ethoxy group chelates with the catalyst, and intermediate III becomes the final product by losing one EtOH molecule.

Reusability

Given the importance of recovering and reusing the catalyst, Fig. 12 depicts the reaction yield for the model reaction (4a) after eight runs with recovered catalyst. After the reaction was completed, the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst was separated from the reaction environment using an external magnet and washed several times with water and methanol to remove any impurities. It was then dried for reuse. Figure 12 shows only a 7% decrease in reaction yield after multiple catalyst recovery runs. The prepared catalyst can be easily recovered and reused, making it an environmentally and economically viable option for industrial applications.

After washing and drying, the recovered catalyst was characterized through FE-SEM, TEM, FT-IR, and XRD analyses. According to the FE-SEM result obtained in Fig. 13a, the catalyst’s morphology did not change after recovery. The TEM image in Fig. 13b showed that the synthesized catalyst maintained its spherical shape and hollow structure after multiple uses, and proper washing of the catalyst prevented poisoning. According to the FT-IR spectrum presented in Fig. 13c, there was no alteration in the functional groups of the catalyst after it was recovered and reused. The XRD pattern (Fig. 13d) of the recovered catalyst did not show any noticeable changes, which indicates the stability of the catalyst’s active sites after recovery and reuse.

The stability of nanoparticles on the catalyst’s surface and the ability to effectively separate the catalyst from the reaction medium were examined through the leaching test (Fig. 14). For this test, the model reaction was used in optimal conditions so that after 3 min, the catalyst was separated from the reaction medium using an external magnet. After separating the catalyst, the reaction was stopped, and no progress was observed in the reaction process. Consequently, the nanoparticles on the surface of the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst exhibit good stability on the substrate, and the magnetic properties of the catalyst ensure complete separation from the reaction medium.

An ICP-OES analysis was performed on the catalyst before and after recovery. The results showed that the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst contained 3.82 × 10–3 molg−1 of Fe, 5.22 × 10–5 molg−1 of Co, and 3.08 × 10–5 molg−1 of Ni. Analysis of two samples indicates that the catalyst remained stable even after eight recovery cycles, with no significant changes detected. The reduction in the percentage of metals present in the catalyst structure after eight recovery steps was observed to be 0.09%, 0.05%, and 0.02% for Fe, Co, and Ni, respectively. The slight variations in the metal content of the nanocatalyst structure demonstrate its extremely high stability.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that the Co–Ni/Fe3O4@MMSHS nanocatalyst significantly enhances the efficiency of producing 1-substituted 1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazole derivatives, achieving yields of up to 98% in a short reaction time. The combination of cobalt and nickel within the catalyst improves its performance, aligning with green chemistry principles by enabling solvent-free reactions at lower temperatures. Additionally, the catalyst’s magnetic properties allow for easy separation and reuse, maintaining high efficiency with only a 7% decrease in yield after multiple cycles. These findings highlight the potential of hollow multimetallic nanocatalysts as sustainable and practical tools for the synthesis of tetrazoles. Future research could further optimize catalyst composition, explore scalability for industrial applications, and develop similar environmentally friendly catalytic systems to broaden their scope and enhance efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Hossein Naeimi repository (naeimi@kashanu.ac.ir).

References

Uppadhayay, R. K., Kumar, A., Teotia, J. & Singh, A. Multifaceted chemistry of tetrazole. Synthesis, uses, and pharmaceutical applications. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 58, 1801–1811 (2022).

Vishwakarma, R., Gadipelly, C. & Mannepalli, L. K. Advances in tetrazole synthesis—an overview. ChemistrySelect 7, e202200706 (2022).

Ding, W.-H. et al. A tetrazole-based fluorescence “turn-on” sensor for Al(iii) and Zn(ii) ions and its application in bioimaging. Dalt. Trans. 43, 6429–6435 (2014).

Popova, E. A., Protas, A. V. & Trifonov, R. E. Tetrazole derivatives as promising anticancer agents. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 17, 1856–1868 (2018).

Neochoritis, C. G., Zhao, T. & Dömling, A. Tetrazoles via multicomponent reactions. Chem. Rev. 119, 1970–2042 (2019).

Klapötke, T. M., Stein, M. & Stierstorfer, J. Salts of 1H-tetrazole–synthesis, characterization and properties. Zeitschrift für Anorg. Allg. Chemie 634, 1711–1723 (2008).

Frija, L. M. T., Ismael, A. & Cristiano, M. L. S. Photochemical transformations of tetrazole derivatives: Applications in organic synthesis. Molecules 15, 3757–3774 (2010).

Sica, D. A., Gehr, T. W. B. & Ghosh, S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of losartan. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 44, 797–814 (2005).

Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1477–1490 (2010).

Olaya, G., Linley, R., Ireland, D., Dorrance, A. & Robertson, A. Sensitivity of 40 Pythium species to the new fungicide Picarbutrazox. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 131, 1137–1143 (2024).

Keam, S. J., Lyseng-Williamson, K. A. & Goa, K. L. Pranlukast. Drugs 63, 991–1019 (2003).

Kwok, D. W. K., Alexander, D., Beeley, N. R. A. & Kelley, D. 6-LB: GPR119 agonist PRM A increases glucagon response to hypoglycemia in rats. Diabetes 72, 6 (2023).

Lanier, C. & Melton, T. C. Oteseconazole for the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A drug review. Ann. Pharmacother. 58, 636–644 (2024).

Babu, A. & Sinha, A. Catalytic Tetrazole synthesis via [3+2] Cycloaddition of NaN3 to organonitriles promoted by Co(II)-complex: isolation and characterization of a Co(II)-diazido intermediate. ACS Omega 9, 21626–21636 (2024).

Atarod, M., Safari, J. & Tebyanian, H. Ultrasound irradiation and green synthesized CuO-NiO-ZnO mixed metal oxide: An efficient sono/nano-catalytic system toward a regioselective synthesis of 1-aryl-5-amino-1 H -tetrazoles. Synth. Commun. 50, 1993–2006 (2020).

Pirouzmand, M., Gharehbaba, A. M., Ghasemi, Z. & Azizi Khaaje, S. [CTA]Fe/MCM-41: An efficient and reusable catalyst for green synthesis of xanthene derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 10, 1070–1076 (2017).

Azizi, S. & Shadjou, N. Iron oxide (Fe3O4) magnetic nanoparticles supported on wrinkled fibrous nanosilica (WFNS) functionalized by biimidazole ionic liquid as an effective and reusable heterogeneous magnetic nanocatalyst for the efficient synthesis of N-sulfonylamidines. Heliyon 7, e05915 (2021).

Kundu, D., Majee, A. & Hajra, A. Indium triflate-catalyzed one-pot synthesis of 1-substituted-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazoles under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 2668–2670 (2009).

Pharande, S. G., Rentería-Gómez, M. A. & Gámez-Montaño, R. Isocyanide based multicomponent click reactions: a green and improved synthesis of 1-substituted 1 H -1,2,3,4-tetrazoles. New J. Chem. 42, 11294–11298 (2018).

Mashhoori, M.-S. & Sandaroos, R. New ecofriendly heterogeneous nano-catalyst for the synthesis of 1-substituted and 5-substituted 1H-tetrazole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 12, 15364 (2022).

Harooni, N. S., Ghasemi, A. H. & Naeimi, H. Efficient and mild synthesis of pyranopyrimidines catalyzed by decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes bearing cobalt, nickel, and copper metals in water. J. Clust. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-022-02374-8 (2022).

Ren, Z. et al. Selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over HZSM-5/CeO2 hybrid catalysts: Relationship between acid structure and reaction mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 358, 130333 (2025).

Varzi, Z. & Maleki, A. Design and preparation of ZnS-ZnFe2O4: A green and efficient hybrid nanocatalyst for the multicomponent synthesis of 2,4,5-triaryl-1 H -imidazoles. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e5008 (2019).

Azizi, S., Soleymani, J. & Hasanzadeh, M. KCC-1/Pr-SO3H: an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for green and one-pot synthesis of 2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one. Nanocomposites 6, 31–40 (2020).

Azizi, S., Darroudi, M., Soleymani, J. & Shadjou, N. Tb2(WO4)3@N-GQDs-FA as an efficient nanocatalyst for the efficient synthesis of β-aminoalcohols in aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 329, 115555 (2021).

Mousavi, S., Naeimi, H., Ghasemi, A. H. & Kermanizadeh, S. Nickel ferrite nanoparticles doped on hollow carbon microspheres as a novel reusable catalyst for synthesis of N-substituted pyrrole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13, 10840 (2023).

Kazempour, S. & Naeimi, H. Bimetallic nanoparticles supported ionic liquid as an effective heterogeneous nanocatalyst for green synthesis of chromenes under solvent-free conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 36, e6903 (2022).

Kharisov, B. I., Dias, H. V. R. & Kharissova, O. V. Mini-review: Ferrite nanoparticles in the catalysis. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 1234–1246 (2019).

Lee, D.-E., Devthade, V., Moru, S., Jo, W.-K. & Tonda, S. Magnetically sensitive TiO2 hollow sphere/Fe3O4 core-shell hybrid catalyst for high-performance sunlight-assisted photocatalytic degradation of aqueous antibiotic pollutants. J. Alloys Compd. 902, 163612 (2022).

Yan, J. MFC aerogel-MNPs composite. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Civil, Structure and Environmental Engineering (Atlantis Press, 2016). https://doi.org/10.2991/i3csee-16.2016.63

Hassanpour, H. & Naeimi, H. Sonocatalysis green synthesis of indeno[1,2-b]indolone derivatives using CuFe2O4@CS-SB nanocomposite as a reusable catalyst under mild conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.7406 (2024).

Alipour, A. & Naeimi, H. Design, fabrication and characterization of magnetic nickel copper ferrite nanocomposites and their application as a reusable nanocatalyst for sonochemical synthesis of 14-aryl-14-H-dibenzo[a,j]xanthene derivatives. Res. Chem. Intermed. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-023-04981-0 (2023).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Asgharnasl, S., Mehraeen, S., Amiri-Khamakani, Z. & Maleki, A. Guanidinylated SBA-15/Fe3O4 mesoporous nanocomposite as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of pyranopyrazole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 11, 19852 (2021).

Zuin, V. G., Eilks, I., Elschami, M. & Kümmerer, K. Education in green chemistry and in sustainable chemistry: perspectives towards sustainability. Green Chem. 23, 1594–1608 (2021).

Maleki, A., Hajizadeh, Z. & Salehi, P. Mesoporous halloysite nanotubes modified by CuFe2O4 spinel ferrite nanoparticles and study of its application as a novel and efficient heterogeneous catalyst in the synthesis of pyrazolopyridine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 9, 5552 (2019).

Chen, J.-F., Ding, H.-M., Wang, J.-X. & Shao, L. Preparation and characterization of porous hollow silica nanoparticles for drug delivery application. Biomaterials 25, 723–727 (2004).

Naeimi, H. & Mohammadi, S. Synthesis of 1H-isochromenes, 4H-chromenes and orthoaminocarbonitrile tetrahydronaphthalenes by CaMgFe2O4 base nanocatalyst. ChemistrySelect 5, 2627–2633 (2020).

Hassanpour, H. & Naeimi, H. Fabrication and characterization of inorganic–organic hybrid copper ferrite anchored on chitosan Schiff base as a reusable green catalyst for the synthesis of indeno[1,2-b]indolone derivatives. RSC Adv. 14, 17296–17305 (2024).

Ahghari, M. R., Soltaninejad, V. & Maleki, A. Synthesis of nickel nanoparticles by a green and convenient method as a magnetic mirror with antibacterial activities. Sci. Rep. 10, 12627 (2020).

Farazin, A., Mohammadimehr, M., Ghasemi, A. H. & Naeimi, H. Design, preparation, and characterization of CS/PVA/SA hydrogels modified with mesoporous Ag2O/SiO2 and curcumin nanoparticles for green, biocompatible, and antibacterial biopolymer film. RSC Adv. 11, 32775–32791 (2021).

Mohammadi, S. & Naeimi, H. A synergetic effect of sonication with yolk-shell nanocatalyst for green synthesis of spirooxindoles. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 14, 345–357 (2021).

Jamkhande, P. G., Ghule, N. W., Bamer, A. H. & Kalaskar, M. G. Metal nanoparticles synthesis: An overview on methods of preparation, advantages and disadvantages, and applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 53, 101174 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Rod-based urchin-like hollow microspheres of Bi2S3: Facile synthesis, photo-controlled drug release for photoacoustic imaging and chemo-photothermal therapy of tumor ablation. Biomaterials 237, 119835 (2020).

Ghasemi, A. H. & Naeimi, H. Design, preparation and characterization of aerogel NiO–CuO–CoO/SiO2 nanocomposite as a reusable catalyst for C-N cross-coupling reaction. New J. Chem. 44, 5056–5063 (2020).

De, S., Zhang, J., Luque, R. & Yan, N. Ni-based bimetallic heterogeneous catalysts for energy and environmental applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3314–3347 (2016).

Zarei, M. & Naeimi, H. Design, preparation and characterization of magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with chitosan/Schiff base and their use as a reusable nanocatalyst for the green synthesis of 1 H-isochromenes under mild conditions. RSC Adv. 14, 1407–1416 (2024).

Zare, M. & Moradi, L. Preparation and modification of magnetic mesoporous silica-alumina composites as green catalysts for the synthesis of Some Indeno[1,2-b]Indole-9,10-Dione derivatives in water media. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42, 6647–6661 (2022).

Kermanizadeh, S., Naeimi, H. & Mousavi, S. An efficient and eco-compatible multicomponent synthesis of 2,4,5-trisubstituted imidazole derivatives using modified-silica-coated cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with tungstic acid. Dalt. Trans. 52, 1257–1267 (2023).

Cao, C.-Y., Cui, Z.-M., Chen, C.-Q., Song, W.-G. & Cai, W. Ceria hollow nanospheres produced by a template-free microwave-assisted hydrothermal method for heavy metal ion removal and catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 9865–9870 (2010).

Azizi, S., Soleymani, J. & Hasanzadeh, M. Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles supported on amino propyl-functionalized KCC-1 as robust recyclable catalyst for one pot and green synthesis of tetrahydrodipyrazolopyridines and cytotoxicity evaluation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5440 (2020).

Azizi, S., Shadjou, N. & Hasanzadeh, M. KCC-1 aminopropyl-functionalized supported on iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles as a novel magnetic nanocatalyst for the green and efficient synthesis of sulfonamide derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5321 (2020).

Shaabani, R. & Naeimi, H. Preparation and characterization of copper ferrite functionalized graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite as an effective and reusable catalyst for synthesis of Spirooxindol Quinazolinone derivatives. J. Clust. Sci. 35, 2445–2457 (2024).

Zhu, M., Tang, J., Wei, W. & Li, S. Recent progress in the syntheses and applications of multishelled hollow nanostructures. Mater. Chem. Front. 4, 1105–1149 (2020).

Zahir, M. H., Irshad, K., Islam, A., Shaikh, M. N. & Hossain, M. M. A hierarchical porous matrix containing hollow MgO microspheres for solar thermal energy storage applications. J. Energy Storage 105, 114679 (2025).

Naeimi, H. & Mohammadi, S. Synthesis of 1 H -isochromenes, 4 H -chromenes, and ortho-aminocarbonitrile tetrahydronaphthalenes from the same reactants by using metal-free catalyst. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57, 50–59 (2020).

Jafari, A., Heydari, S., Ariannezhad, M., Ahmadi, S. & Habibi, D. Removal of the Cd(II), Ni(II), and Pb(II) ions via their complexation with the uric acid-based adsorbent and use of the corresponding Cd-complex for the synthesis of tetrazoles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 786, 139195 (2022).

Habibi, D., Nasrollahzadeh, M. & Kamali, T. A. Green synthesis of the 1-substituted 1H–1,2,3,4-tetrazoles by application of the Natrolite zeolite as a new and reusable heterogeneous catalyst. Green Chem. 13, 3499 (2011).

Naeimi, H. & Kiani, F. Ultrasound-promoted one-pot three component synthesis of tetrazoles catalyzed by zinc sulfide nanoparticles as a recyclable heterogeneous catalyst. Ultrason. Sonochem. 27, 408–415 (2015).

Karimi Zarchi, M. A. & Nazem, F. Cross-linked poly (4-vinylpyridine) supported azide ion as a versatile and recyclable polymeric reagent for synthesis of 1-substituted-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazoles. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 11, 91–99 (2014).

Potewar, T. M., Siddiqui, S. A., Lahoti, R. J. & Srinivasan, K. V. Efficient and rapid synthesis of 1-substituted-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazoles in the acidic ionic liquid 1-n-butylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Tetrahedron Lett. 48, 1721–1724 (2007).

Ansari, M., Ghasemi, A. H. & Naeimi, H. Efficient synthesis of tetrazoles via [2 + 3] cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by cobalt–nickel on magnetic mesoporous hollow spheres. RSC Adv. 15, 18535–18547 (2025).

Ghamari Kargar, P. & Bagherzade, G. The anchoring of a Cu (ii)–salophen complex on magnetic mesoporous cellulose nanofibers: green synthesis and an investigation of its catalytic role in tetrazole reactions through a facile one-pot route. RSC Adv. 11(31), 19203–19220 (2021).

Salimi, M., Esmaeli-nasrabadi, F. & Sandaroos, R. Fe3O4@Hydrotalcite-NH2-CoII NPs: A novel and extremely effective heterogeneous magnetic nanocatalyst for synthesis of the 1-substituted 1H–1, 2, 3, 4-tetrazoles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 122, 108287 (2020).

Xue, W., Yang, G., Karmakar, B. & Gao, Y. Sustainable synthesis of Cu NPs decorated on pectin modified Fe3O4 nanocomposite: Catalytic synthesis of 1-substituted-1H-tetrazoles and in-vitro studies on its cytotoxicity and anti-colorectal adenocarcinoma effects on HT-29 cell lines. Arab. J. Chem. 14, 103306 (2021).

Sajjadifar, S., Zolfigol, M. A. & Chehardoli, G. H. Boron sulfuric acid as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of 1-substituted 1H–1, 2, 3, 4-tetrazoles in polyethylene glycol. Eurasian Chem. Commun. 2, 812–818 (2020).

Kal-Koshvandi, A. T., Maleki, A., Tarlani, A. & Soroush, M. R. Synthesis and characterization of ultrapure HKUST-1 MOFs as reusable heterogeneous catalysts for the green synthesis of tetrazole derivatives. ChemistrySelect 5, 3164–3172 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the University of Kashan for supporting this work by Grant No. 159148/85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maryam Ansaria and Amir Hossein Ghasemi wrote the main manuscript text and Maryam Ansaria, Amir Hossein Ghasemi and Hossein Naeimi prepared all figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, M., Ghasemi, A.H. & Naeimi, H. Cobalt–nickel supported on magnetic mesoporous silica hollow spheres for efficient synthesis of tetrazole derivatives under solvent-free conditions. Sci Rep 15, 35650 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19534-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19534-1