Abstract

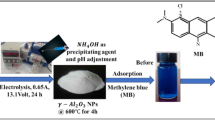

The persistent presence of reactive dyes in textile wastewater poses a significant environmental challenge due to their resistance to conventional treatment methods. In this study, a novel Curcumin-functionalized MIL-88 A metal-organic framework (MOF) was synthesized using a green, ethanol-based method for the enhanced removal of reactive blue dye from aqueous solutions. The composite was characterized using FTIR, XRD, FESEM, EDS, BET, and UV–vis spectroscopy. FTIR analysis confirmed successful curcumin functionalization, XRD patterns showed the retention of MIL-88 A crystallinity, and FESEM revealed well-defined spindle-shaped particles with curcumin coating. EDS indicated increased carbon content, while BET analysis demonstrated enhancements in surface area (from 32.35 to 39.70 m²/g) and pore volume (from 0.2816 to 0.3582 cm³/g), improving the material’s adsorption performance. Under optimized UV-assisted conditions (pH 4, 0.080 g adsorbent, 50.953 min), the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite achieved a removal efficiency of 99.98% in the first cycle and a maximum adsorption capacity of 80.89 mg/g based on Langmuir isotherm fitting. Kinetic studies showed that the pseudo-second-order model best described the adsorption behavior, suggesting chemisorption as the dominant mechanism. Isotherm modeling indicated that the Freundlich model provided the best fit, implying multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface. These results confirm a synergistic removal mechanism involving both adsorption and photodegradation. The Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite thus represents a promising, reusable candidate for sustainable wastewater treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The textile industry is a major consumer of water, utilizing between 25 and 250 m³ of water per ton of product, depending on the processes involved1. In the early 20th century, synthetic dyes largely replaced natural dyes due to their ease of synthesis, low cost, color stability, and versatility2. These dyes are widely applied in fabric dyeing, paper printing, leather processing, pharmaceuticals, color photography, cosmetics, plastics, food additives, petroleum products, and various industrial applications2. Many synthetic dyes, including azo, anthraquinone, and triphenylmethane classes, are toxic, mutagenic, and resistant to degradation, posing significant environmental and health hazards when discharged into water bodies. For example, dyes such as malachite green3, methyl orange4, and resorcinol5 have been shown to persist in aquatic environments and interfere with photosynthesis and aquatic life. Reactive blue dyes, specifically, are known for their high water solubility and structural stability due to sulfonate and azo functional groups, making them particularly difficult to remove by conventional means6. Therefore, novel adsorbent systems capable of targeting such persistent dyes are urgently needed7.As one of the largest producers of dyes, the textile industry generates wastewater characterized by high Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) and a diverse range of colors8. The Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) to COD ratio in this effluent is approximately 0.25, indicating that most compounds are non-biodegradable and potentially toxic to aquatic life9,10. Due to their high solubility, reactive dyes pose a major environmental challenge, with approximately 50% discharged into wastewater at concentrations of 10–200 mg·L⁻¹11. Reactive dyes, characterized by azo bonds and sulfonate groups, are particularly resistant to biodegradation and conventional treatment methods12. Following azo dyes, reactive dyes are the second most common dye type in textile applications, primarily used for dyeing yarn, wool, and polyamide fibers13. Their solubility makes them persistent in aquatic environments, where they pose significant economic and ecological risks10. Conventional wastewater treatment methods, such as coagulation and sedimentation, struggle to remove these dyes effectively14. However, adsorption has emerged as a promising, cost-effective, and efficient technology for dye removal, producing minimal secondary pollution15,16. Recent advances have utilized low-cost adsorbents, including natural materials, bio-adsorbents, and industrial or agricultural wastes17. For instance, eggshells—a widely available food industry byproduct—have shown potential as natural adsorbents for dyes and phenolic compounds due to their CaCO₃ composition and functional groups like –OH, –C = O, PO₄³⁻, amines, and amides18,19,20. Additionally, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have gained attention as highly tunable adsorbents with tailored pore sizes and adsorption properties, achieved by varying organic ligands and metal ions during synthesis21,22,23,24,25. MOFs offer diverse applications, including water purification, toxic gas removal, gas storage, catalysis, and energy storage due to their highly tunable structures and multifunctional properties26,27,28,29,30,31. Recent studies have explored MOF-based composites with enhanced environmental remediation capabilities, particularly in dye adsorption and photodegradation. For instance, sulfonated MIL-101(Cr), UiO-66-based hybrids, and ZIF-67@GO composites have demonstrated high efficiency in removing pollutants such as malachite green and methyl orange from aqueous media32,33,34. These composites benefit from increased surface area, porosity, and reactivity, often showing synergistic removal effects. In addition to these materials, recent studies have demonstrated the promising performance of novel adsorbent systems combining metal-organic frameworks, clays, and organic functional groups for efficient dye removal and photocatalysis. For example, functionalized porous composites have shown high removal efficiencies and improved reusability in wastewater systems35,36. Hybrid nanomaterials and engineered interfaces have also been explored for their synergistic dye degradation potential under light-assisted conditions37,38. Additionally, clay-based and bio-inspired materials continue to receive attention due to their low cost, abundance, and structural versatility39,40. These developments highlight the growing demand for multifunctional and eco-compatible materials in advanced wastewater treatment. Additionally, broader reviews have addressed the emerging role of MOFs in sustainable water purification41. These advances further highlight the need for cost-effective, bio-compatible MOF systems capable of tackling persistent pollutants through both adsorption and degradation pathways. MOFs, with their high surface areas and tunable pore sizes, have shown superior performance in dye removal compared to traditional adsorbents42. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as highly effective adsorbents for dye removal due to their high surface areas (up to 7000 m²/g), tunable pore sizes, and versatile functionalization capabilities22,42. For instance, MOF-235 has demonstrated 87% removal efficiency for methylene blue at pH 5 over 90 min43, while MIL-101 and UiO-66 have shown promise for cationic dyes, achieving 70–90% removal efficiencies, attributed to their large pore volumes (up to 1.6 cm³/g) and robust frameworks42,44. However, these MOFs face significant limitations, including limited stability in acidic or alkaline environments, which restricts their applicability in diverse industrial wastewater conditions26,42. Additionally, high synthesis costs and the lack of synergistic adsorption-photodegradation mechanisms limit their scalability and effectiveness for complex dye mixtures, such as reactive blue, which is highly soluble and resistant to conventional treatments12,42. These challenges highlight critical research gaps, including the need for cost-effective, eco-friendly MOFs with enhanced stability across a wide pH range and the ability to combine adsorption with photocatalytic degradation. The integration of natural compounds, such as curcumin, known for its phenolic and carbonyl groups that enhance radical generation and dye adsorption45, into MOFs remains underexplored, presenting an opportunity to address these limitations.

In this study, we introduce a novel Curcumin-functionalized MIL-88 A metal–organic framework (MOF), designed to address the key limitations of conventional MOFs in textile wastewater treatment. Traditional MOFs often suffer from high synthesis costs, limited stability across diverse pH ranges, and insufficient catalytic activity under ambient conditions26,42,44. To overcome these drawbacks, our approach integrates the photoactive and eco-friendly properties of curcumin—a natural compound with phenolic and carbonyl groups that enhance radical generation and dye adsorption45—with the high surface area and structural tunability of MIL-88 A. The resulting composite leverages a dual removal mechanism: (i) adsorption via chemisorption and π–π interactions at active surface sites, and (ii) UV-assisted photodegradation driven by curcumin-generated reactive oxygen species. This synergy enables the Curcumin/MIL-88 A nanocomposite to achieve a remarkable 99.98% removal efficiency for reactive blue dye under optimized conditions (pH 4, 50.9 min UV exposure), surpassing the performance of previously reported MOFs such as MOF-235, MIL-101, and UiO-6643,44. The major objectives of this study are: (1) to synthesize and characterize the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite using a green and scalable method; (2) to evaluate its performance in removing reactive blue dye across a range of operational conditions; (3) to elucidate the synergistic adsorption–photodegradation mechanism through experimental evidence and kinetic/isotherm modeling; and (4) to assess its reusability and potential for industrial-scale wastewater treatment. This research offers a sustainable and high-efficiency approach to address persistent dye pollution, bridging the gap between bio-inspired materials and advanced water purification technologies.

Experiments

Materials

Turmeric powder (used for curcumin extraction) was purchased from a local market in Tehran, Iran. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification: fumaric acid (C₄H₄O₄, ≥ 99%), iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6 H₂O, ≥ 98%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥ 98%), dimethylformamide (DMF, C₃H₇NO, anhydrous, 99.8%), and ethanol (C₂H₅OH, ≥ 99.5%, analytical grade). Reactive Blue Dye (commercial grade) was used as received, and deionized water was used throughout all synthesis and experimental procedures.

Characterization

A Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–visible spectrophotometer was used to evaluate the effect of the nanoabsorbent on reaction progress and the removal efficiency of reactive blue dye from model water and wastewater samples. The UV spectrophotometer was set to 592 nm for reactive blue dye measurements. In this instrument, solution absorbance was measured using a quartz cell with a 1 cm path length. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained using a Bruker VERTEX 70 FT-IR spectrophotometer. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded with a PANalytical X’Pert Pro device, while a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM), model TESCAN MIRA3, was employed to characterize the morphology, surface properties, and surface imaging of the nanoabsorbent.

Design of experiments (DOE)

Design-Expert software (version 11.0.3, DX) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) were utilized for experimental design and optimization, respectively. The effects of pH, reactive blue dye concentration, nanoporous Curcumin/MIL-88 A mass (in grams), and reaction time on the removal efficiency of reactive blue dye were investigated. RSM is a widely recognized and standard method for optimizing such systems46.

2.3.1. Effects of pH, Pollutant Concentration, Nanoporous Mass, and Reaction Time on Pollutant Removal in Water and Wastewater Models.

Initial operating conditions were derived from previous studies to assess the influence of key variables on reactive blue dye removal. Following preliminary tests, the software determined the confidence intervals for each variable. The evaluated ranges were as follows: pH from 1 to 13, reactive blue dye concentration from 10 to 145 mg·L⁻¹, nanoporous Curcumin/MIL-88 A mass from 0.01 to 0.08 g, and reaction time (UV Exposure Time) from 1 to 60 min. Specific reactive blue dye concentrations of 10, 35, 55, 100, and 256 mg·L⁻¹ were also tested. To prepare these solutions, specified concentrations were dissolved in deionized water within 25 mL volumetric flasks. After inputting these parameters into the Design-Expert software, an experimental plan was generated, and the proposed design was obtained and presented in Table 1.

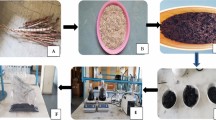

Synthesis of nanoporous MIL-88 A

A solution containing 10 mmol of FeCl₃·6 H₂O and 10 mmol of Fumaric acid dissolved in 50 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF), along with 4 mL of 2 M sodium hydroxide, was stirred for 1 h and then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. The mixture was heated at 150 °C for 48 h using a hotplate with magnetic stirring. This procedure was adapted from the synthesis protocol reported by Chalati et al.47. Subsequently, the resulting material was filtered and washed three times consecutively with water and ethanol. The obtained precipitate was then dried at 70 °C for 24 h in an oven. A schematic overview of the synthesis steps is presented in Fig. 1 in supporting information file to visually illustrate the simplicity and eco-friendly nature of the process.

Synthesis of Curcumin extract from turmeric

To prepare the curcumin extract, 15 g of turmeric powder and 100 mL of ethanol were heated in a beaker at 70 °C for 30 min with continuous stirring. A temperature of 70 °C was selected based on previous studies showing enhanced extraction efficiency in this range due to improved solubility of curcumin and disruption of plant cell walls48. Although ethanol has a boiling point of 78.5 °C, solvent loss was minimized by using a loosely covered system and limiting the exposure time. Alternative extraction methods (e.g., ultrasonic or microwave-assisted techniques) were not considered in order to preserve the simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness of the process. The resulting yellow-orange solution was then filtered and used to functionalize MIL-88 A. This method was adapted from the procedure described by Jebarani et al.45.

Synthesis of green nanoporous curcumin/MIL-88 A

A mixture of 5 g of MIL-88 A and 100 mL of curcumin extract was added to a reflux flask and refluxed for 15 h using a reflux apparatus. Refluxing was conducted at 70 °C, consistent with the curcumin extraction temperature. The resulting Functionalized precipitate was then filtered and washed three times consecutively with water and ethanol. The precipitate was dried at ambient temperature for 12 h. To enhance clarity and provide a visual summary of the synthetic pathway, a schematic diagram has been included in Fig. 2 in supporting information file, illustrating both the green extraction of curcumin from turmeric and the subsequent reflux-assisted functionalization of MIL-88 A.

Elimination studies

The removal of reactive blue dye from model water and wastewater samples was performed using nanoporous Curcumin/MIL-88 A under UV Light irradiation. The maximum absorption wavelength of reactive blue dye in this study was determined to be 592 nm. In a standard procedure for dye removal, 0.008 g of nanoporous Curcumin/MIL-88 A adsorbent was added to 20 mL of a 100 mg·L⁻¹ reactive blue dye solution. The mixture was stirred at 70 rpm using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for durations ranging from 1 to 60 min. The UV-assisted removal process was conducted in a simple reactor equipped with a UV lamp to evaluate the performance of the nanoporous adsorbent. The pH was adjusted using 0.2 M NaOH and 0.2 M HCl solutions. Removal efficiency was calculated as a function of time according to Eq. 149:

Where C₀ and C represent the initial concentration and the concentration of reactive blue dye (in mg·L⁻¹) at time t, respectively.

To determine the optimal conditions for the performance of the nanoporous Curcumin/MIL-88 A adsorbent, various parameters were investigated, including the mass of synthesized nanoporous adsorbent (0.004–0.02 g), reactive blue dye concentration (10–145 mg·L⁻¹), and pH (1–13).

Results and discussion

XRD analysis

Figure 1 presents the XRD patterns of MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A. The characteristic diffraction peaks of MIL-88 A align well with those reported in previous studies50,51. The XRD pattern of MIL-88 A washed with ethanol differs from that of the sample washed with water, with the primary distinction being the intensity of prominent peaks between 10.8° and 12°. This variation is also influenced by the washing method applied to the precipitate in the final synthesis step52. Additionally, prior reports indicate that functionalization can alter the XRD pattern of such compounds53. The XRD pattern of Curcumin/MIL-88 A reveals that functionalization with curcumin does not significantly alter the core structure of MIL-88 A; however, minor shifts in peak positions and intensity variations indicate successful functionalization without disrupting the core MIL-88 A framework. Additionally, pure curcumin typically exhibits broad diffraction peaks in the range of 12° to 18° (2θ), attributed to its semi-crystalline nature. In the XRD pattern of Curcumin/MIL-88 A, small shifts and broadening within this region can be observed, which are absent in the pristine MIL-88 A. These features suggest the successful incorporation of curcumin molecules on the MOF surface. Although curcumin does not form a crystalline phase in the composite, its interaction with MIL-88 A causes measurable modifications in diffraction intensity and peak position. These observations Further confirm surface Functionalization without structural disruption. These modifications confirm the incorporation of curcumin onto the surface. Notably, the characteristic peaks of pure curcumin appear in the range of 12–18°.

The presence of sharp peaks in the XRD patterns confirms the crystallinity of the synthesized nanoporous materials. The nanoparticle sizes of the samples were calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation (Eq. 2)54:

where D is the average crystallite size (in nm), k is the Scherrer constant (0.89), λ is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the diffraction angle (in degrees) corresponding to the peak position, and β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak (in radians)52.

Using Eq. 2, the nanoparticle sizes of nanoporous MIL-88 A were determined to range from 44.21 to 72.40 nm, with an average size of 66.19 nm. For the functionalized Curcumin/MIL-88 A, the nanoparticle sizes ranged from 17.04 to 88.55 nm, with an average size of 46.72 nm, consistent with field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) results.

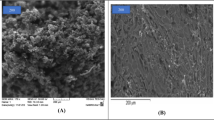

Morphological, elemental, surface interaction analysis and X-ray mapping analysis of MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of nanoporous MIL-88 A and functionalized Curcumin/MIL-88 A are presented in Fig. 2. The images clearly show that MIL-88 A exhibits a spindle-shaped morphology, consistent with previous reports52,53. The particles appear as elongated hexagonal rods with relatively uniform size distribution, with an average particle size of approximately 125 nm. After functionalization with curcumin, a slight increase in surface roughness and a reduction in particle uniformity are observed, suggesting successful surface modification. The primary crystalline morphology remains intact, although the average diameter of the nanoparticles shows a slight decrease.

These morphological changes, along with the increased carbon content confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Fig. 3(a) and (b)), indicate the effective incorporation of curcumin onto the MIL-88 A structure. The EDS patterns further verify the presence of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and iron (Fe) in both samples, with a notable increase in carbon content after functionalization, while the oxygen signal remained stable or slightly reduced. Among the detected elements, carbon showed the highest relative abundance, whereas iron was the least represented.

As illustrated schematically in Fig. 2, the reaction between MIL-88 A and curcumin molecules results in a ligand exchange process on the surface of the spindle-shaped MIL-88 A structures. Owing to its bidentate diketone configuration, curcumin effectively replaces fumaric acid ligands on the MIL-88 A surface. This exchange is corroborated by FTIR spectra, where the characteristic C = O stretching vibration near 1670 cm⁻¹ (associated with free fumaric acid) disappears in the Curcumin/MIL-88 A spectrum. Additionally, the absence of new peaks above 1670 cm⁻¹ confirms that no esterification occurred, making ligand exchange the most likely mechanism. This substitution introduces new functional groups and results in a chemically modified MIL-88 A surface with enhanced reactivity.

The distribution of elements and the increased presence of carbon and oxygen on the surface of the Curcumin/MIL-88 A photoactive nanocomposite crystalline network are illustrated through elemental mapping patterns in Fig. 3((c) and (d)). The colored dots in Fig. 3(c) and (d) indicate uniform coverage and confirm the incorporation of curcumin molecules onto the photoactive nanocomposite surface. Carbon and oxygen, the primary constituents of the photoactive nanocomposite, exhibit the most significant presence, as evidenced by their predominant representation in the X-ray mapping images.

FT-IR analysis

Figure 4 presents the Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra of nanoporous MIL-88 A and functionalized Curcumin/MIL-88 A, respectively. A broad absorption band around 3422 cm⁻¹ is observed in both spectra, attributed to water absorption and O–H stretching from surface hydroxyl groups53. The MIL-88 A spectrum shows a strong peak near 1670 cm⁻¹ (highlighted in green), which corresponds to the C = O stretching vibrations of free carboxylic acid groups from fumaric acid at the particle surface55,56,57. In the Curcumin/MIL-88 A spectrum, this carbonyl peak is significantly diminished or absent, suggesting that surface-bound fumaric acid groups have been replaced during the functionalization process.

The absorption bands at 1398 cm⁻¹ and 1613 cm⁻¹ are associated with symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxyl group (–COOH) in fumarate, respectively, and are typical indicators of bridging ligands in metal-organic framework (MOF) structures55,56,57. In the Curcumin/MIL-88 A spectrum, a new absorption band appears at 1510 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to C = C stretching vibrations from the aromatic rings in curcumin50,52,56. This shift further supports the incorporation of curcumin molecules.

The characteristic peaks at 1214 cm⁻¹ (C–C stretching) and 985 cm⁻¹ (C–H bending) in MIL-88 A shift to 1216 cm⁻¹ and 977 cm⁻¹ in Curcumin/MIL-88 A, respectively. Fe–O vibrational modes also shift from 549 to 672 cm⁻¹ to 519–675 cm⁻¹, suggesting slight structural modifications upon curcumin coordination50,52,56. These shifts confirm that while the MOF core remains largely intact, curcumin molecules have chemically interacted with the MIL-88 A framework.

The yellow-highlighted band associated with O–H vibrations from fumaric acid also decreases in intensity after functionalization, providing further evidence that surface carboxylic acid groups originally bound to Fe centers were exchanged with curcumin Ligands. Due to its conjugated bidentate diketone structure, curcumin can effectively coordinate with Fe ions, forming strong chelating bonds. The stretching vibrations of complexed diketone groups typically appear in the 1500–1630 cm⁻¹ region, consistent with the observed peaks.

In addition, the FTIR spectrum of Curcumin/MIL-88 A shows broad bands in the 3200–3400 cm⁻¹ range, assigned to the O–H stretching vibrations of phenolic groups in curcumin. Shifts and intensity changes in bands around 1100–1300 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C stretching) and 1500–1600 cm⁻¹ (C = C aromatic stretching) further confirm successful functionalization50,53,55,56,57,58. Overall, the spectral differences between MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A confirm the exchange of surface ligands and introduction of curcumin without disrupting the MOF’s crystalline structure.

BET/BJH analysis

The surface area, textural properties, and pore diameter of the mesoporous materials were determined using nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms, with calculations performed via the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) methods. The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms for MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A are presented in Fig. 5(a and b). The BET surface area and pore structure of the synthesized materials are critical parameters that influence their adsorption and catalytic properties. After curcumin Functionalization, the BET surface area increased from 32.35 to 39.70 m²/g, and the total pore volume also slightly increased. This enhancement can be attributed to the presence of curcumin molecules that prevent particle aggregation and may introduce additional micropores or structural irregularities. Moreover, curcumin’s functional groups can interact with the surface of MIL-88 A, leading to better dispersion and increased accessibility of active sites. The wall thickness also increased significantly, from 0.4550 to 7.8590 nm, likely due to the formation of an organic layer around the MOF structure and the potential partial blocking of smaller pores, which contributes to apparent thickening in BJH analysis. These findings indicate that curcumin acts not only as a surface functional agent but may also contribute to structural modification at the pore wall level.

According to the IUPAC classification, the nitrogen adsorption isotherm for MIL-88 A corresponds to Type IV, featuring a characteristic H3 hysteresis loop in the relative pressure range (P/P₀) of 0.40–0.99. The hysteresis loop closes near P/P₀ = 0.4, indicative of mesoporous materials with micropores exhibiting capillary condensation. The BET and BJH parameters of the samples are summarized in Table 2.

Interestingly, BET results showed a slight increase in both surface area and pore volume after curcumin functionalization, contrary to the common expectation of pore blockage upon guest molecule loading. This behavior is likely due to surface-level modifications rather than internal pore occupation. Curcumin molecules may have contributed to improved particle dispersion and altered surface morphology, generating new mesoporous regions or interstitial voids between MOF particles. Furthermore, the planar aromatic structure of curcumin may have stabilized the composite and reduced agglomeration, thereby exposing more surface area for N₂ adsorption. The unchanged pore diameter supports the conclusion that the intrinsic microporous framework of MIL-88 A was preserved during functionalization.

The wall thickness of the mesoporous structure was calculated using Eq. 359:

where d₁₀₀ is the interplanar spacing (in nm) derived from the Bragg angle (2θ) for the (100) reflection, and DBJH is the pore diameter (in nm) determined by the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method.

As shown in Fig. 5(c and d), both MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A exhibit mesoporous structures with pore sizes ranging approximately from 2 to 35 nm. However, the BJH plot for Curcumin/MIL-88 A demonstrates a consistently higher incremental pore volume (dVp\drp), especially in the range above 20 nm. This indicates enhanced mesopore accessibility and a greater overall pore volume after curcumin functionalization, despite the average pore diameter remaining constant. The observed increase is attributed to structural modifications such as improved particle dispersion and the formation of interparticle voids, which are consistent with the BET results in Table 2.

Zeta potential

As the surface charge (positive or negative) increases, the suspension of particles in a medium is enhanced due to heightened repulsive forces between particles. Conversely, when the charge decreases and approaches zero, repulsive forces diminish, leading to particle aggregation, cluster formation, and subsequent settling. The charge density at a given point is determined by the difference in ion concentration and is related to the zeta potential and electric potential at the interface with the surrounding medium. In this study, MIL-88 A synthesized using dimethylformamide (DMF) as a solvent exhibited an average zeta potential of + 2.26 mV, attributed to an excess of free iron sites on its surface. After functionalization with curcumin, the zeta potential of Curcumin/MIL-88 A increased to + 4.87 mV, indicating improved particle dispersion and a higher surface charge density. This increase is attributed to the presence of curcumin’s polar functional groups, such as phenolic hydroxyl and keto groups, which contribute additional surface electronegativity and stability in suspension. Pure MIL-88 A likely possesses both free iron sites and sites coordinated with fumaric acid, terminating in carboxylate groups, with a slight predominance of iron sites contributing to the net positive charge. Upon functionalization with curcumin to form Curcumin/MIL-88 A, the surface area increases, enhancing the accessibility of free iron sites. This results in a significant increase in the dispersion and suspension of iron ions60,61.

To further elucidate the role of electrostatic interactions in dye adsorption, the zeta potential of MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A was measured across a pH range of 2 to 11 (Fig. 6). The zeta potential of Curcumin/MIL-88 A gradually decreased from + 28 mV at pH 2 to − 27 mV at pH 11, indicating a surface charge reversal and an isoelectric point (IEP) near pH 5.5. This trend confirms that the composite retains a positively charged surface under acidic conditions, favoring electrostatic attraction with the negatively charged sulfonate groups of the reactive blue dye. Conversely, under alkaline conditions, the negative surface charge results in repulsive forces, reducing adsorption efficiency. This behavior strongly supports the observed optimal dye removal at pH 4 and reinforces the role of pH-dependent surface charge in the adsorption mechanism of the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite.

TGA-DTA curves

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves for MIL-88 A and Curcumin/MIL-88 A are presented in Fig. 7. The weight loss of MIL-88 A (initial mass: 1.224 mg) with increasing temperature can be divided into three distinct stages.

For MIL-88 A, the first stage, from room temperature to approximately 131 °C, exhibits a weight loss of 25.33% (0.266 mg), attributed solely to the evaporation of water or residual solvent, likely trapped within the structure. In the second stage (131–451.67 °C), a weight loss of 40.98% (0.501 mg) occurs, primarily due to the combustion of organic ligands, leading to the gradual degradation and collapse of the organic framework. In the third stage, further weight loss with increasing temperature is negligible, as only inorganic components (e.g., iron oxides) remain after the combustion of organic material. The DSC-TGA curves indicate that the organic structure degrades progressively across multiple stages. Up to 282 °C, the weight loss is minimal (approximately 5%), with a gradual slope, demonstrating significant thermal stability below this temperature.

For Curcumin/MIL-88 A, the first stage, from room temperature to approximately 134 °C, shows a weight loss of 16.25% (0.199 mg), also attributed to the evaporation of water or residual solvent trapped within the structure. In the second stage (134–437 °C), a weight loss of 34.81% (0.426 mg) is observed, resulting from the combustion of organic ligands and the subsequent collapse of the organic framework. In the final stage, weight loss with increasing temperature is insignificant, as only inorganic residues (e.g., iron oxides) remain after organic combustion. According to the DSC-TGA curves, the organic structure degrades gradually in several stages. Up to 375.6 °C, the weight loss is Limited to approximately 5.8% with a gentle slope, indicating enhanced thermal stability compared to pure MIL-88 A.

Statistical analysis

According to Table 1, the highest color degradation is observed in Experiment 21, with a value of 99.98%, while the lowest degradation occurs in Experiment 4, with a value of 23.14%. The primary differences between these upper and lower limits are attributed to variations in pH and the intensity of ultraviolet (UV) light radiation. In this system, the materials exhibit linear interactions, meaning that, within a specific range, the percentage of color degradation increases proportionally with increases in pH and UV radiation, without the influence of moderating or intervening variables. Consequently, the behavior of the material is predictable and follows a natural trend.

A key factor in this process is the initial dye concentration in the solution. In Experiment 21, where the dye concentration is minimal, the highest degradation efficiency is achieved. Conversely, in experiments with higher dye concentrations, the greatest degradation occurs in Experiment 20, with 20 min of UV radiation and an acidic pH. Overall, the degradation of this dye is enhanced in an acidic environment, suggesting that acidic conditions facilitate the breakdown of its molecular structure.

The validity of the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) model, designed according to Table 3 for this study, yielded a p-value less than 0.05 (specifically 0.0025), indicating a statistically significant difference in the effects of the variables on dye degradation. Thus, it can be concluded that pH, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, initial dye concentration, and adsorbent mass significantly influence degradation efficiency. Furthermore, the F-test statistic for UV radiation increased to 19.77, exceeding the overall model statistic, suggesting that UV radiation has the most substantial impact on dye degradation among the variables tested.

In interpreting the ANOVA results (Table 3), we considered p-values less than 0.05 as statistically significant. This threshold indicates that the corresponding variable has a meaningful and non-random influence on the dye degradation process. For example, UV exposure (p = 0.0005) and pH (p = 0.0034) were found to have highly significant effects, confirming their critical role in enhancing adsorption efficiency. In contrast, variables such as dye concentration (p = 0.0890) and some interaction terms (e.g., AC, AD) showed p-values above 0.05, suggesting a less pronounced individual effect. Nevertheless, these variables may still contribute to system performance when considered in combination. This interpretation supports the robustness of the model and helps prioritize the most influential operational parameters.

Although the ANOVA results indicate a significant lack of fit (p = 0.0469), this should be interpreted cautiously. The low pure error and the strong significance of both the overall model (p = 0.0025) and key factors such as UV radiation and pH suggest that the quadratic model still provides a meaningful approximation of the system behavior. Furthermore, the regression plot and normal probability plot demonstrate good alignment and residual distribution, indicating that the model predictions remain reliable. The significant lack of fit may arise from subtle nonlinearities or interactions beyond second-order terms; however, these are not expected to compromise the overall conclusions or the practical applicability of the optimized conditions.

Key statistical indicators were calculated to evaluate the performance and predictive power of the RSM quadratic model. The coefficient of determination (R²) was found to be 0.8149, indicating that over 81% of the response variability can be explained by the model. The adjusted R² value of 0.6874 accounts for the number of model terms and confirms model stability, while the predicted R² of 0.5122 indicates reasonable agreement between predicted and experimental values. Additionally, the Adequate Precision ratio was 9.02, well above the minimum desirable value of 4.0, confirming that the model has a strong signal-to-noise ratio and is suitable for navigating the design space. These values collectively support the reliability of the developed model for predicting reactive blue dye degradation.

The mathematical model for this experimental design is presented in Eq. 4:

A normal probability plot illustrates the extent to which variables conform to a normal distribution. Even with normally distributed data, some moderate deviations are expected. A distinctive “S”-shaped curve, easily recognizable in the plot, suggests that applying a transfer function to the dependent variable or model response could improve the analysis. According to Fig. 8(a), the variables exhibit a nearly linear distribution on the normal probability plot. Given that the data points closely align with a straight line, the variables influencing the degradation of reactive blue dye demonstrate normal behavior.

The Box-Cox plot is a diagnostic tool used to identify the most suitable power transformation (lambda, λ) for the response variable. The lowest point on the plot corresponds to the optimal lambda value that minimizes the residual sum of squares in the transformed model. When the ratio of the maximum to minimum response values exceeds 3, applying a power transformation can significantly enhance model fit. According to Fig. 8(b), the ratio of the maximum to minimum response values is exactly 3, suggesting that further improvement through a power transformation may be Limited. The 95% confidence interval for lambda is also depicted in the plot. Based on Fig. 8(b), the current lambda value establishes an effective mathematical relationship between the variables and is deemed appropriate for this study.

Regression analysis is a statistical method used to estimate relationships between variables, allowing the strength of these relationships to be classified as weak, moderate, or strong. In this study, Fig. 8(c) demonstrates that the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable is strong. This is evidenced by the fact that all test responses (the dependent variable) fall within the predicted range of the linear regression model. A stronger relationship between variables in an experiment enhances the accuracy of the predicted response.

Identifying the effects of variables on dye degradation

Three-dimensional (3D) response surface plots, derived from experimental data, were used to visualize the influence of process variables and their interactions on the degradation efficiency of reactive blue dye (Fig. 9).

Figure 9(a) demonstrates that the highest degradation occurs at 60 min of UV radiation and under strongly acidic pH conditions, indicating the process performs optimally when both irradiation time and acidity are maximized.

Figure 9(b) illustrates that an increase in dye concentration, when combined with lower pH, results in improved degradation efficiency. This suggests that acidic conditions facilitate the breakdown of the dye’s molecular structure, enhancing its susceptibility to degradation.

In Fig. 9(c), the combined effects of adsorbent dosage and pH are shown. The plot reveals that increasing the adsorbent mass under acidic conditions significantly improves treatment efficiency. This indicates a synergistic effect, where low pH enhances degradation and higher adsorbent loading boosts active site availability.

Figure 9d) shows that maximum degradation is achieved when UV irradiation is increased and the initial dye concentration is minimized. This implies that lower contaminant load combined with greater photonic energy input enhances the degradation kinetics.

According to Fig. 9(e), optimal degradation occurs when both the adsorbent mass and UV radiation are at their highest levels, as indicated by the bright orange region on the plot. This emphasizes the strong dependence of degradation efficiency on combined adsorptive and photocatalytic effects.

Lastly, Fig. 9(f) reveals that maximum degradation is observed when the adsorbent mass is increased and the initial dye concentration is low, further confirming that an excess of active adsorption sites relative to the dye molecules promotes efficient removal.

Three-dimensional response surface plots illustrating the effects and interactions of key operational parameters on the degradation efficiency of reactive blue dye using Curcumin/MIL-88 A under UV-assisted conditions: (a) Effect of UV exposure time and pH, (b) Effect of initial dye concentration and pH, (c) Effect of adsorbent dose and pH, (d) Effect of dye concentration and UV exposure, (e) Effect of UV exposure and adsorbent dose and (f) Effect of adsorbent dose and dye concentration.

To complement the 3D response surface plots and provide a clearer comparison of individual parameter effects, we generated corresponding percentage-based bar graphs (See Fig. 3 in supporting information file). These bar plots present the dye removal efficiency at low, medium, and high levels of each factor — pH, UV exposure time, dye concentration, and adsorbent dose — as optimized by RSM. This visualization aids intuitive understanding while supporting the quantitative analysis presented in the 3D interaction plots.

The strong influence of pH is attributed to the surface charge behavior of Curcumin/MIL-88 A. At acidic pH (particularly around 4), the MOF surface becomes positively charged, which enhances electrostatic attraction with the negatively charged sulfonate groups in Reactive Blue dye. In contrast, under basic conditions, surface charge inversion leads to electrostatic repulsion, reducing dye removal efficiency. The impact of UV exposure is also significant; longer exposure promotes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from curcumin, such as singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals, which contribute to the photodegradation of adsorbed dye molecules. Increasing adsorbent dosage improves dye removal due to the greater number of active sites, while elevated initial dye concentrations can exceed the available adsorption capacity, leading to saturation and reduced efficiency.

Isotherm models

In order to describe the adsorption equilibrium behavior of reactive blue dye onto Curcumin/MIL-88 A, four classical isotherm models were applied: Langmuir62, Freundlich63, Temkin64, and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R)65. These models are commonly used to represent monolayer adsorption, multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, energy distribution, and adsorption energy estimation, respectively.

Adsorption isotherms define the equilibrium relationships between an adsorbent and the adsorbate in solution66,67,68,69. The correlation coefficient (R²) and error function values were employed to assess the thermodynamic behavior of the reactions, specifically their fit and convergence. Using the experimental data, monolayer adsorption isotherms for all systems were calculated and are presented in Table 4, which identifies the best-fitting isotherms based on minimal error and maximum correlation.

Among the four isotherm models evaluated, the Freundlich model yielded the highest correlation coefficient (R² = 0.9964), indicating that the adsorption occurs on a heterogeneous surface via multilayer coverage. This is consistent with previous findings on MOF-based adsorbents70,71. The value of 1/n = 0.5274 also confirmed favorable adsorption behavior. In contrast, the Langmuir model showed lower correlation (R² = 0.9421), suggesting a limited contribution from monolayer adsorption on homogeneous sites. The Temkin model provided insight into adsorbate–adsorbent interactions, while the Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) model helped estimate the adsorption energy, indicating that the process likely involves a combination of physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms.

The fitted parameters for each isotherm model, along with their correlation coefficients (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) values, are summarized in Table 5.

The Freundlich model, exhibiting the highest R² value (0.9964), best described the adsorption equilibrium, indicating a heterogeneous surface and multilayer adsorption. The 1/n value of 0.5274 suggests favorable adsorption (as 0 < 1/n < 1), while KF reflects high adsorption capacity on the heterogeneous surface. The Langmuir model estimated a maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) of 5.87 mg/g, but the fit was poorer (R² = 0.9421), implying that monolayer adsorption is not the dominant mechanism. The Temkin and D–R models showed moderate to weak fits, supporting that the interaction is not uniform and that chemisorption with varied binding energies is likely involved.

where \(\:{q}_{exp}\) is the experimental adsorption capacity, \(\:{q}_{model}\) is the value predicted by the isotherm model, \(\:\stackrel{-}{{q}_{exp}}\) is the mean of experimental values, and \(\:n\) is the number of data points.

10. Kinetic models

To evaluate the adsorption behavior of reactive blue dye over time, a comprehensive kinetic study was conducted. The experimental data were analyzed using various kinetic models, including first-order, second-order, pseudo-first-order, and pseudo-second-order formulations. The results are summarized in Table 6, with further detailed parameters presented in Table 7 (linear regression) and Table 8 (non-linear regression).

For a more robust analysis, both linear and non-linear regression approaches were applied to four widely used kinetic models: Blanchard (pseudo-second-order), Elovich, pseudo-first-order (Lagergren), and intra-particle diffusion (IPD)67,68,69,70. Among the linear models (Fig. 10), the Blanchard model exhibited the highest correlation coefficient (R² = 0.9878), indicating that the adsorption of dye onto the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite is primarily governed by chemisorption mechanisms. This suggests that the adsorption process likely involves valence forces or electron sharing between dye molecules and curcumin functional groups.

To increase model accuracy and validate the kinetic assumptions, non-linear regression was also performed using the same model equations. The non-linear Blanchard model again provided the best fit (R² = 0.9955), reinforcing its reliability as the most representative model for describing the adsorption kinetics. The Elovich and pseudo-first-ordermodels also showed improved R² values under non-linear conditions, while the IPD model consistently exhibited the weakest fit in both regression methods.

Overall, these results confirm that the adsorption process follows a pseudo-second-order kinetic model, emphasizing the predominance of chemical interactions. The Elovich model’s moderate fit supports the presence of surface heterogeneity and potential activation energy barriers, which are common in heterogeneous catalytic systems. On the other hand, the weaker fits of the pseudo-first-order and IPD models suggest that physisorption and intra-particle diffusion are not the dominant mechanisms in this system.

These interpretations align with findings from similar adsorption studies involving curcumin- and MOF-based adsorbents73,74. The quality of the model fits and comparative behavior are visually depicted in Fig. 11, which presents the non-linear regression plots for all four kinetic models and highlights the agreement between experimental data and theoretical predictions.

11. Optimum value version

Various amounts of synthesized Curcumin/MIL-88 A nanosorbent (0.01–0.08 g) and reactive blue dye solutions with concentrations of 10, 35, 55, 100, and 145 mg·L⁻¹ were prepared across a pH range of 1–13. To achieve these specified concentrations, 25 mL of each reactive blue solution was dispensed into borosilicate glass (BG) bottles. Different masses of Curcumin/MIL-88 A were then added to the BG bottles containing the reactive blue dye, and the mixtures were immediately transferred to a reactor. The samples were subjected to ultraviolet (UV) Light irradiation on a magnetic stirrer at 70 rpm for 40 min at room temperature. The equilibrium adsorption capacity was calculated using Eq. 749:

where qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mass of pollutant adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent, in mg·g⁻¹), C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of the pollutant (in mg·L⁻¹), respectively, V is the solution volume (in L), and W is the adsorbent mass (in g).

The optimal conditions for reactive blue dye removal were determined as follows: an adsorbent mass of 0.080 g, an initial reactive blue dye concentration of 73.11 mg·L⁻¹, a pH of 4 for the water and wastewater samples, and an optimal reaction time of 50.935 min. The synthesis of the Curcumin/MIL-88 A photoactive nanocomposite required a maximum reaction time of 48 h, suggesting it could serve as a viable alternative to conventional adsorbents. Under the optimal conditions (C₀ = 73.11 mg·L⁻¹, Cₑ = 0.012 mg·L⁻¹, V = 0.025 L, W = 0.08 g), the adsorption capacity (qe) was calculated to be 22.84 mg·g⁻¹. In addition, the Langmuir isotherm model estimated a theoretical maximum adsorption capacity (qₘₐₓ) of 80.89 mg/g, as presented in Table 5. While qₑ reflects the experimental uptake under optimized test conditions, qₘₐₓ represents the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity under ideal conditions. This distinction helps quantify both the practical performance and the full adsorption potential of the composite, demonstrating its strong capacity for pollutant removal. The optimal conditions for the test achieving maximum dye degradation are summarized in Table 9.

The degradation performance of Curcumin/MIL-88 A was evaluated under varying operational parameters to determine their individual effects on dye removal efficiency. At a pH of 4, the material achieved the highest removal rate of 99.98%, attributed to strong electrostatic interactions between the positively charged surface and the anionic dye. As the pH increased to 9 and above, efficiency declined to 79.5%, Likely due to surface charge repulsion. Increasing the adsorbent dosage from 0.01 g to 0.08 g improved dye removal from 68.4 to 99.98%, indicating that more active sites were available for adsorption. Similarly, UV exposure time was a critical parameter: at 10 min, the removal efficiency was 60.1%, while at the optimal 50.935 min, it reached 99.98%, highlighting the significant role of photocatalytic enhancement. In terms of dye concentration, maximum removal occurred at 73.11 mg·L⁻¹ (99.98%), whereas higher concentrations (e.g., 145 mg·L⁻¹) resulted in decreased efficiency (74.2%), likely due to saturation of active sites. These findings are quantitatively visualized in the newly added bar graphs (See Fig. 3 in supporting information file), which complement the 3D surface plots by showing the removal trends at low, medium, and high levels of each factor.

To isolate the contribution of each component in the composite, separate experiments were conducted using pure MIL-88 A and pure curcumin under identical conditions. As shown in Table 10, MIL-88 A alone removed 63.2% of the dye, and curcumin alone achieved 71.4% removal. In contrast, the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite exhibited a significantly enhanced removal efficiency of 99.98%. This highlights the synergistic interaction between the MOF structure and curcumin functional groups, supporting the proposed dual adsorption–photodegradation mechanism.

Beyond enhancing adsorption kinetics, UV exposure also likely contributed to photodegradation of the dye. Curcumin is a natural photosensitizer known to produce reactive oxygen species under UV light, such as singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals75. When incorporated into the MIL-88 A framework, curcumin’s photoactivity can be enhanced by the MOF’s high surface area and light-absorbing properties. This synergy likely promotes the breakdown of dye molecules in solution, complementing adsorption with partial photodegradation. Therefore, the observed removal efficiency under UV light reflects a dual mechanism: surface adsorption and light-driven chemical degradation. Similar photocatalytic enhancements under UV treatment have been reported for MOF-based or hybrid photocatalysts in dye removal applications76,77.

Based on the combined results of kinetic modeling, isotherm fitting, and UV optimization experiments, several mechanisms appear to contribute to the removal of reactive blue dye by Curcumin/MIL-88 A. The excellent fit to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model suggests that chemisorption plays a dominant role, involving valence forces or electron sharing between dye molecules and functional groups on the composite surface. The Freundlich isotherm fit further supports multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface, indicating the presence of high-energy and low-energy binding sites. Additionally, under acidic conditions (pH 4), electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged dye molecules and positively charged surface sites on MIL-88 A enhances dye uptake. The aromatic structure of curcumin may also facilitate π–π stacking interactions with the dye’s aromatic rings. Finally, the role of UV irradiation in photodegradation, as evidenced by optimized removal under UV exposure, suggests that photoinduced oxidative degradation contributes to the overall dye removal through reactive oxygen species generation. This multipronged mechanism aligns well with prior studies on curcumin-MOF composites70,78,79.

Table 11 provides a performance comparison of the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite with other reported adsorbents for dye removal, highlighting its high efficiency and fast operation under UV conditions.

Based on our findings, dye removal by Curcumin/MIL-88 A occurs via a dual mechanism. In the absence of UV light, the dominant mechanism is adsorption, as supported by the pseudo-second-order kinetics and Freundlich isotherm fit. Under UV irradiation, curcumin’s photosensitizing ability enhances dye removal through photodegradation, generating reactive oxygen species that break down dye molecules. Therefore, the overall removal efficiency results from the synergy between these two mechanisms, which has now been consistently described throughout the manuscript.

12. Reusability study

To evaluate the practical applicability of the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite, its reusability was assessed over four adsorption–desorption cycles under identical experimental conditions. After each cycle, the used adsorbent was recovered by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and distilled water, dried at 60 °C, and reused. As shown in Fig. 12, the removal efficiency slightly decreased from 99.98% in the first cycle to 93.2% by the fourth, indicating reasonable structural stability and reusability. This performance trend is consistent with previous studies on MOF-based dye adsorbents, such as ZnFe₂O₄@MOF hybrids and modified ZIF-8 composites83,84, and confirms the potential of Curcumin/MIL-88 A for repeated use in water treatment applications.

1 proposed adsorption and photodegradation mechanism

The removal of Reactive Blue dye by the Curcumin-functionalized MIL-88 A composite occurs through a synergistic dual mechanism involving both adsorption and photodegradation. Under acidic conditions (optimal at pH 4), the composite surface becomes positively charged, promoting strong electrostatic attraction with the anionic sulfonate groups of the dye. Additionally, π–π stacking interactions between the aromatic rings of curcumin and the dye molecules further enhance adsorption affinity. Kinetic modeling confirmed that chemisorption is the dominant adsorption mechanism, while the Freundlich isotherm model indicated multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface.

To differentiate between adsorption and photodegradation pathways, UV–vis spectroscopy was employed to monitor dye removal at 592 nm. In the absence of UV light (dark conditions), the composite achieved a removal efficiency of 71–75%, indicating that adsorption alone plays a substantial role. However, under UV irradiation, the removal efficiency increased significantly to 99.98%, highlighting the critical contribution of photodegradation. Comparative experiments showed that MIL-88 A alone removed 63.2% of the dye, curcumin alone achieved 71.4%, and the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite reached 99.98%, confirming a synergistic interaction between the two components.

This enhanced performance is attributed to curcumin’s photosensitizing capability, which under UV light generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as singlet oxygen (^1O₂) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH). These ROS oxidize and degrade dye molecules adsorbed on the composite surface. Therefore, the high removal efficiency results from the combined effects of surface adsorption and light-driven oxidative degradation, establishing the composite as a highly effective and sustainable material for wastewater treatment.

The interactions between the adsorbents and Reactive Blue dye molecules are schematically illustrated in Fig. 13. In the case of MIL-88 A, the dominant mechanism is ionic interaction between the carboxylic acid groups of surface-bound fumaric acid and the amine groups of dye molecules, resulting in ammonium–carboxylate ionic bonds. In contrast, the Curcumin/MIL-88 A composite exhibits not only ammonium–phenolate interactions between the dye and phenolic groups of curcumin, but also a diverse range of π–π stacking interactions between the benzene rings of curcumin and the aromatic rings of the dye molecules. This broader interaction profile significantly increases the adsorption affinity of the composite, thereby improving the overall dye removal efficiency.

Conclusion

Curcumin-functionalized MIL-88 A was successfully synthesized as an eco-friendly metal-organic framework (MOF) with superior adsorption performance for reactive blue dye removal, achieving 99.98% efficiency under optimized conditions (pH 4, 60 min UV exposure). Functionalization with curcumin significantly enhanced surface area, pore size, and adsorption capacity, making it more effective than MIL-88 A alone. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) confirmed the strong influence of pH, UV exposure, adsorbent dosage, and dye concentration on removal efficiency. Additionally, the adsorbent exhibited stability across various pH levels, including alkaline conditions, making it a promising candidate for large-scale industrial wastewater treatment. With its cost-effective synthesis, high efficiency, and sustainable nature, Curcumin/MIL-88 A presents an innovative and practical solution for water purification challenges, with potential for broader wastewater applications and industrial scalability. This study also provides detailed insight into how operational parameters such as pH, UV exposure, dye concentration, and adsorbent dose influence adsorption capacity and removal efficiency, confirming the practical viability of Curcumin/MIL-88 A for environmental applications.

4. Nomenclature.

All of the parameter’s value and Greek letters have been listed in Table 1 in supporting information file.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dos Santos, A. B., Cervantes, F. J. & Van Lier, J. B. Review paper on current technologies for decolourisation of textile wastewaters: perspectives for anaerobic biotechnology. Bioresour. Technol. 98 (12), 2369–2385 (2007).

Moubasher, H. A. Optimization of peroxidase production of Humicola grisea Traaen and its application in biodegradation of textile dyes.

Shah, H. U. R. et al. Water stable graphene oxide metal-organic frameworks composite (ZIF-67@ GO) for efficient removal of malachite green from water. Food Chem. Toxicol. 154, 112312 (2021).

Naseem, K. et al. Investigation of catalytic potential of sodium Dodecyl sulfate stabilized silver nanoparticles for the degradation of Methyl orange dye. J. Mol. Struct. 1262, 132996 (2022).

Ahmad, K. et al. Towards sustainable water purification: MOFs as a promising solution to eliminate toxic water pollutant resorcinol. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 237 (10), 1669–1689 (2023).

Ahmad, K. et al. Metal organic framework (KIUB-MOF-1) as efficient adsorbent for cationic and anionic dyes from brackish water. J. Mol. Struct. 1242, 130898 (2021).

Khan, M. et al. Fabrication of CuWO4@ MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite for efficient OER and photodegradation of methylene blue. Heliyon, 10(23), e40546 (2024).

Alinsafi, A. et al. Electro-coagulation of reactive textile dyes and textile wastewater. Chem. Eng. Process. 44 (4), 461–470 (2005).

Sevimli, M. F. & Sarikaya, H. Z. Ozone treatment of textile effluents and dyes: effect of applied Ozone dose, pH and dye concentration. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnology: Int. Res. Process. Environ. Clean. Technol. 77 (7), 842–850 (2002).

Goodhead, T. & Abowei, M. Sewage treatment and utilization. Int. J. Prev. Control Industrial Pollution. 7 (1), 1–14 (2021).

Sarkar, A. Dyeing Technologies for Denim Garments, in Denimp. 271–285 (Elsevier, 2015).

Periyasamy, A. P. Recent advances in the remediation of textile-dye-containing wastewater: prioritizing human health and sustainable wastewater treatment. Sustainability 16 (2), 495 (2024).

Arslan-Alaton, I., Gursoy, B. H. & Schmidt, J. E. Advanced oxidation of acid and reactive dyes: effect of Fenton treatment on aerobic, anoxic and anaerobic processes. Dyes Pigm. 78 (2), 117–130 (2008).

Kathi, S. & Mahmoud, A. E. D. Trends in effective removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater: A comprehensive review. Desalination Water Treat., 317, 100258 (2024).

George, G., Ealias, A. M. & Saravanakumar, M. P. Advancements in textile dye removal: a critical review of layered double hydroxides and clay minerals as efficient adsorbents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (9), 12748–12779 (2024).

Ihenetu, S. et al. Pollution and health risks assessment of ground water sources around a waste disposal site in Owerri West local government area of Imo state. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 11 (9), 1560–1573 (2020).

Zannagui, C. et al. Design, characterization and investigation of heavy metal ions removal by new cellulose-ether based adsorbent. Moroccan J. Chem. 8 (1), pJChem8N–12020332 (2020).

Abunah, D. et al. Physicochemical removal of heavy metals from contaminated water using recyclable montmorillonite cellulose nanocomposite. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 10 (12), 1349–1361 (2019).

Manyatshe, A. & Sibali, L. L. A review on egg waste-based adsorbents for the removal of organic and inorganic contaminants from aqueous solution. Heliyon, 11(3), e42278 (2025).

Chowdhury, S. & Das, P. Utilization of a domestic waste—eggshells for removal of hazardous malachite green from aqueous solutions. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. 31 (3), 415–425 (2012).

Fu, Y. & Viraraghavan, T. Fungal decolorization of dye wastewaters: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 79 (3), 251–262 (2001).

Rowsell, J. L. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal–organic frameworks: a new class of porous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 73 (1–2), 3–14 (2004).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Achieving high density of adsorbed hydrogen in microporous metal organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 17 (22), 2703–2706 (2005).

Chen, B. et al. High H2 adsorption in a microporous metal–organic framework with open metal sites. Angew. Chem. 117 (30), 4823–4827 (2005).

Rosi, N. L. et al. Hydrogen storage in microporous metal-organic frameworks. Science 300 (5622), 1127–1129 (2003).

Hayat, A. et al. Recent advance in MOFs and MOF-based composites: synthesis, properties, and applications. Mater. Today Energy, 41, 101542. (2024).

Zhan, X. Q. et al. Ligands-coordinated Zr-based MOF for wastewater treatment. Nanomaterials 8 (9), 655 (2018).

Ahmad, K. et al. MOFs@ COFs composites: advances, challenges, and multifunctional applications in emerging technologies. Hybrid. Adv. 9, 100419 (2025).

Maqsood, K. et al. Synthesis and photocatalytic degradation efficiency of MgFe2O4@ CuO nanocomposite for bromophenol blue dye removal. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 72 (4), 390–400 (2025).

Abbas, S. et al. Cutting-edge metal-organic frameworks: revolutionizing the adsorptive removal of pharmaceutical contaminants from water. Rev. Inorg. Chem., https://doi.org/10.1515/revic-2024-0119 (2025).

Ahmad, K. et al. Engineering of zirconium based metal-organic frameworks (Zr-MOFs) as efficient adsorbents. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B. 262, 114766 (2020).

Cevik, E. et al. Metal organic frameworks embedded polymeric membranes: A comprehensive review on application in water purification and seawater desalination. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 116215, p (2025).

Iqbal, A. et al. Ultrahigh adsorption by regenerable iron-cobalt core-shell nanospheres and their synergetic effect on nanohybrid membranes for removal of malachite green dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (3), 107968 (2022).

Iqbal, A. et al. Highly robust multilayer nanosheets with ultra-efficient batch adsorption and gravity-driven filtration capability for dye removal. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 109, 287–295 (2022).

Eleryan, A. et al. Isothermal and kinetic screening of Methyl red and Methyl orange dyes adsorption from water by Delonix regia biochar-sulfur oxide (DRB-SO). Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13585 (2024).

Khalil, A. et al. Magnetic pomegranate peels activated carbon (MG-PPAC) composite for acid orange 7 dye removal from wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 14 (8), p–178 (2024).

Nazir, M. A. et al. Synthesis of bimetallic mn@ ZIF–8 nanostructure for the adsorption removal of Methyl orange dye from water. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 165, 112294 (2024).

Nazir, M. A. et al. Heterointerface engineering of water stable ZIF-8@ ZIF-67: adsorption of Rhodamine B from water. Surf. Interfaces. 34, 102324 (2022).

Nazir, M. A. et al. Surface induced growth of ZIF-67 at Co-layered double hydroxide: removal of Methylene blue and Methyl orange from water. Appl. Clay Sci. 190, 105564 (2020).

Shahzad, K. et al. Synthesis of nanoadsorbent entailed mesoporous Organosilica for decontamination of Methylene blue and Methyl orange from water. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 103 (20), 8799–8812 (2023).

Farooq, M. et al. Characterization and adsorption study of biosorbents for the removal of basic cationic dye: kinetic and isotherm analysis. Desalination Water Treat. 160, 333–342 (2019).

Mane, P. V. et al. Unveiling cutting-edge advances in high surface area porous materials for the efficient removal of toxic metal ions from water. Prog. Mater. Sci. 101314, p (2024).

Haque, E., Jun, J. W. & Jhung, S. H. Adsorptive removal of Methyl orange and Methylene blue from aqueous solution with a metal-organic framework material, iron terephthalate (MOF-235). J. Hazard. Mater. 185 (1), 507–511 (2011).

Uddin, M. J., Ampiaw, R. E. & Lee, W. Adsorptive removal of dyes from wastewater using a metal-organic framework: A review. Chemosphere 284, 131314 (2021).

Jebarani, A. H. et al. Fabrication and optimization of curcumin-multiwalled carbon nanotube (C-MWCNT) conjugate reinforced electrospun polyacrylonitrile membrane for water treatment applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (34), 46652–46668 (2024).

Zarrinabadi, E. et al. Environmental effects of enhancement of mechanical and hydrophobic properties of polyester fabrics using silica/kaolinite/silver nanocomposite: a facile technique for synthesis and RSM optimization. EurAsian J. Biosci. 12 (2), 437–450 (2018).

Chalati, T. et al. Optimisation of the synthesis of MOF nanoparticles made of flexible porous iron fumarate MIL-88A. J. Mater. Chem. 21 (7), 2220–2227 (2011).

Li, S. et al. Chemical composition and product quality control of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). (2011).

Nezhad, P. A. et al. Optimized electrospun Schiff-base alumoxane/pan nanofibers for lead and cadmium adsorption: characterization & RSM analysis. J. Polym. Res. 32 (2), 51 (2025).

Liu, N. et al. Ultrathin graphene oxide encapsulated in uniform MIL-88A (Fe) for enhanced visible light-driven photodegradation of RhB. Appl. Catal. B. 221, 119–128 (2018).

Amaro-Gahete, J. et al. Fast ultrasound-assisted synthesis of highly crystalline MIL-88A particles and their application as ethylene adsorbents. Ultrason. Sonochem. 50, 59–66 (2019).

Fu, H. et al. Room-temperature Preparation of MIL-88A as a heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalyst for degradation of Rhodamine B and bisphenol a under visible light. Mater. Res. Bull. 125, 110806 (2020).

Ren, G., Zhao, K. & Zhao, L. A Fenton-like method using ZnO doped MIL-88A for degradation of methylene blue dyes. RSC Adv. 10 (66), 39973–39980 (2020).

Bensemlali, M. et al. Novel synthesis of nanocalcite from phosphogypsum and cesium carbonate: control and optimization of particle size. Eng 5 (2), 932–943 (2024).

Mellot-Draznieks, C. et al. Very large swelling in hybrid frameworks: a combined computational and powder diffraction study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (46), 16273–16278 (2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Coupling of heterogeneous advanced oxidation processes and photocatalysis in efficient degradation of Tetracycline hydrochloride by Fe-based mofs: synergistic effect and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 369, 745–757 (2019).

Yu, D. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic ozonation of organic pollutants using an iron-based metal-organic framework. Appl. Catal. B. 251, 66–75 (2019).

Lin, K. Y. A., Chang, H. A. & Hsu, C. J. Iron-based metal organic framework, MIL-88A, as a heterogeneous persulfate catalyst for decolorization of Rhodamine B in water. RSC Adv. 5 (41), 32520–32530 (2015).

Ali, N. S., Albayati, T. M. & Salih, I. K. Studying the kinetics and removal mechanism of the methylene blue dye in a continuous adsorption process using prepared mesoporous materials. Water Pract. Technol. 19 (7), 2799–2815 (2024).

Albayati, N. & Kadhom, M. Preparation of functionalised UiO-66 metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) nanoparticles using deep eutectic solvents as a benign medium. Micro Nano Lett. 15 (15), 1075–1078 (2020).

Mejia-Ariza, R. & Huskens, J. The effect of PEG length on the size and guest uptake of PEG-capped MIL-88A particles. J. Mater. Chem. B. 4 (6), 1108–1115 (2016).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40 (9), 1361–1403 (1918).

Freundlich, H. Adsorption in solids. Z. Phys. Chem. 57, 385–470 (1906).

Temkin, M. Kinetics of ammonia synthesis on promoted iron catalysts. Acta Physiochim URSS. 12, 327–356 (1940).

Dubinin, M. The equation of the characteristic curve of activated charcoal. in Dokl Akad. Nauk. SSSR 55, 327–329 (1947).

Rani, R. et al. Enhanced hydrothermal stability of Cu MOF by post synthetic modification with amino acids. Vacuum 164, 449–457 (2019).

Rahmati, M. et al. Cu–curcumin/MCM-41 as an efficient catalyst for in situ conversion of carbazole to fuel oxygenates: A DOE approach. J. Nanostructure Chem. 12 (3), 307–327 (2022).

Kamani, M. et al. Promotion of catalytic properties of Vanillin loaded MCM-41 by Cu (I) and Cu (II) for enhanced removal of Quinoline contaminants. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 65 (2), 4833–4841 (2020).

Fard, N. E. & Fazaeli, R. Optimization of operating parameters in photocatalytic activity of visible light active ag/tio 2 nanoparticles. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A. 92, 2835–2846 (2018).

Foo, K. Y. & Hameed, B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156 (1), 2–10 (2010).

Dong, Q., Wei, Q. & Tang, Z. Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2): an Emerging Multifunctional Nanomaterial for Sensing and Removal of Agricultural Contaminants4p. 173–192 (ACS Agricultural Science & Technology, 2024). 2.

Usgodaarachchi, L. et al. SWCNT functionalised with poly (vinyltriazole): a method to determine the optimal stoichiometry through adsorption kinetics and isotherms. in 2024 Spring Meeting of the European Materials Research Society (E-MRS). (2024).

Chatterjee, S. & Woo, S. H. The removal of nitrate from aqueous solutions by Chitosan hydrogel beads. J. Hazard. Mater. 164 (2–3), 1012–1018 (2009).

Zhou, Y. et al. Recent advances for dyes removal using novel adsorbents: a review. Environ. Pollut. 252, 352–365 (2019).

BB, A. Curcumin: the Indian solid gold. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 595, 1–75 (2007).

Guo, Y. et al. UV-light promoted formation of Boron nitride-fullerene composite and its photodegradation performance for antibiotics under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 410, 124628 (2021).

Al Azzi, P., Kurdi, R. E. & Patra, D. Curcumin encapsulation in aluminum fumarate Metal–Organic frameworks for enhanced stability and antioxidant activity. ACS Omega. 9 (51), 50561–50569 (2024).

Wu, S. et al. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of Tetracycline over TiO2. Chem. Eng. J. 382, 122842 (2020).

Vo, T. K. et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of MgFe2O4-decorated UiO-66 (Zr)-NH2 composites for collaborative adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of Tetracycline. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 39 (9), 2532–2541 (2022).

Namasivayam, C. & Kavitha, D. Removal of congo red from water by adsorption onto activated carbon prepared from Coir pith, an agricultural solid waste. Dyes Pigm. 54 (1), 47–58 (2002).

Annadurai, G., Juang, R. S. & Lee, D. J. Use of cellulose-based wastes for adsorption of dyes from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 92 (3), 263–274 (2002).

Neppolian, B. et al. Solar/UV-induced photocatalytic degradation of three commercial textile dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 89 (2–3), 303–317 (2002).

Hegde, V. et al. Functional porous Ce-UiO-66 MOF@ keratin composites for the efficient adsorption of Trypan blue dye from wastewater: A step towards practical implementations. Chem. Eng. J. 461, 142103 (2023).

Elsherbiny, A. S. et al. Efficiency and selectivity of cost-effective Zn-MOF for dye removal, kinetic and thermodynamic approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (49), 106860–106875 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nima Valinejad for his advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Masoumehalsadat Rahmati drafted the main manuscript.Mina Kamani supervised the study.Ali Rostami edited, reviewed, and corrected the data and manuscript.Ali Ashraf Derakhshan proposed the novel aspects of the study.Samin Mozafari prepared the figures for the study.Mohadeseh Sarhadi and Mohana Mousavi edited the manuscript.All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahmati, M., Kamani, M., Rostami, A. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of Curcumin functionalized MIL-88 A metal organic framework for reactive blue dye removal optimized by response surface methodology. Sci Rep 15, 35652 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19556-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19556-9