Abstract

The ambitious target of halving carbon emissions by 2030 is a challenging goal, but the United States is making gradual progress. The sufficiency of energy resources, energy expenditure, and policy uncertainties in economies can be key determinants of achieving this goal. This study aims to empirically investigate the dynamic relationship between carbon dioxide emissions and the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) in the United States. The analysis is based on monthly frequency data derived from annual datasets spanning the period from 1985 to 2022. Empirical testing is conducted using an advanced non-parametric technique, multivariate quantile on quantile regression (QQR). The findings indicate a negative impact of the energy security index and energy expenditure on carbon dioxide emissions, as well as a significant adverse influence of EPU on emissions. This paper recommends policies, reforms, and interventions related to energy awareness, energy conservation, the promotion of green energy, reforming the energy structure, reducing energy consumption, technology improvement, and better management of the EPU to reduce emission levels in the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States is the world’s largest economy and the second-largest emitter of carbon dioxide1. As the second-largest emitter, rigorous efforts and policy undertakings are underway in the USA to achieve a 50% reduction in carbon emissions from 2005 by 20302. A variety of factors influence carbon emissions, and this paper focuses on the nexus between carbon emissions and variables such as economic policy uncertainty, energy security, and energy expenditure. Literature on the above nexus is active, but many of the researchers are divided. This research gap is addressed in this paper, with a particular focus on the economy of the United States.

Economic policy uncertainty is a dominant factor affecting carbon emissions3,4. Atsu and Adams5 also support the notion that EPU influences carbon emissions. Economic policy uncertainty has a significant impact on carbon emissions in the US economy, and bidirectional causality between CO2 emissions and economic policy uncertainty has been identified in the US economy6. Wang, Xiao, and Lu7 have empirically tested the nexus between economic policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emission in the US economy using the autoregressive-distributed lag (ARDL) model, on data for the period from 1960 to 2016, and found a long-term positive association between economic policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emission in the US economy. Similarly, a study on the nexus between economic policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emissions in the US economy, using data from 1985 to 2017, has identified that economic policy uncertainty enhances carbon emissions8. The empirical evidence from a panel Granger causality analysis, using data on the G7, by Pirgaip and Dinçergök9, for the period 1998–2018, has identified unidirectional causality between economic policy uncertainty and carbon emissions in the USA and Germany. The study results of Ahmed et al.10 also show that reducing economic policy uncertainty is essential for reducing carbon emissions in the US economy.

Holistic approaches are crucial for reducing carbon emissions associated with energy expenditure. The findings of Johnsen and Unander11, related to the blended and coordinated deployment of system engineering and a macroeconomic model for reducing energy demand in the Norwegian residential sector, are unlikely to have a significant impact on the economy. Researchers, such as Vorwald12, have identified energy usage as the most critical contributor to global warming, and approximately 30% of carbon emissions in the United States originate from existing buildings; all these point out the need for managing energy consumption in buildings in the USA. Energy usage in buildings accounts for approximately 40% of a building’s operating costs. New energy technologies with a special focus on the green building concept are inevitable for better energy usage, energy efficiency, and emission reduction from buildings in the USA12,13. Burtraw, Walls, and Blonz14 have indicated that 40% of the carbon dioxide emissions in the United States of America are from the electricity sector. Electricity consumption accounts for approximately 31.2% of total direct energy expenditure by households in the USA. The results of research on the impact of economic policy uncertainty on carbon emissions in the US, using the bootstrap ARDL approach, by Syed and Bouri15, indicate a positive nexus between EPU and carbon emissions in the short term and a negative impact in the long run.

The energy security index can play a significant role in evaluating and monitoring energy security in economies16. However, several methodological challenges have been identified in creating a comprehensive energy security index17. The energy security index can also be used for reducing carbon emissions, but the relationship is under-researched. Moreover, the energy security index can be used for evaluating individual countries and for comparing energy security among nations18,19. Furthermore, the energy security index has several dimensions.

This chapter of introduction is followed by a literature review, which utilizes thematic formats and Scopus resources. The third chapter discusses research methodology. The fourth chapter includes empirical testing of data and results. The discussion of research findings is the fifth unit, and the final unit is the conclusion, which also includes a discussion of promising niches for further research.

Furthermore, unlike prior studies that rely on single-variable quantile-based analyses, our approach isolates the pure effect of each independent variable while controlling for the influence of the others, providing a more realistic and policy-relevant understanding of emission dynamics. We also validate our findings with robustness checks using both Quantile Regression comparisons and Kernel-based Regularised Least Squares (KRLS), which further reinforces the reliability and novelty of our analytical framework.

This methodological integration, to the best of our knowledge, is one of the first empirical applications of MQQR in the context of environmental economics, focusing on carbon emissions within the US energy-economic policy nexus.

This study seeks to answer the following core questions: (i) What is the nature of the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions and the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) in the US? (ii) Do these relationships exhibit non-linear and asymmetric characteristics across the distribution of emissions? To investigate these, the study applies a novel non-parametric multivariate quantile on quantile regression approach. The findings reveal a significant non-linear and asymmetric impact: while ESI and EPU generally contribute to lowering emissions, EE is positively associated with emissions. These insights are crucial for targeted policy formulation aimed at meeting the USA’s 2030 carbon reduction goals.

While the literature presents several studies examining the relationship between carbon emissions and factors such as energy expenditure and economic policy uncertainty, minimal empirical research has integrated the role of the Energy Security Index (ESI) into this nexus using robust non-parametric frameworks. Existing studies primarily rely on linear or bivariate approaches, often neglecting the complex interdependence and asymmetric behaviour among these variables. This study fills a critical gap by employing a novel multivariate quantile-on-quantile regression (QQR) method to simultaneously analyse the dynamic and nonlinear relationships between carbon dioxide emissions, ESI, energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) in the United States. This approach not only captures distributional dependencies but also provides deeper insights into tail behaviours, thereby contributing both methodological advancements and contextual relevance to the environmental economics literature.

Literature review

This paper is based on Scopus resources, and the Boolean operators used for this research are “carbon dioxide” emission, OR CO2 emission; AND "energy security index", OR “energy expenditure”, OR "economic policy uncertainty". The records are downloaded on 30/01/2024. A systematic review of downloaded resources from the Scopus database is conducted to prepare the literature review section.

The search was conducted on a topic basis and yielded 174 records, comprising 151 articles and seven conference papers. In the first step, the duplicates and anonymous articles are removed. Twelve duplicates and twenty-five anonymous records are removed in this step. The remaining 137 records are evaluated by reading the title and abstract, and twenty-two records without abstracts are detected and removed. Moreover, 64 records, which are irrelevant to this discussion, are also excluded. The details of paper screening and selection are shown in (Fig. 1).

The major themes of this research are shown in (Fig. 2). The nexus between carbon emission and each of the variables under study (nexus between carbon emission and energy expenditure; carbon emission and economic policy uncertainty; carbon emission and energy security index) has been taken as the theme for discussion.

Carbon dioxide emission and energy expenditure

Energy expenditure does influence carbon emissions. Dehdar et al.20 conducted a detailed study of the determinants of carbon emissions in the USA and identified an adverse effect of energy expenditure on carbon emissions. Energy efficiency is crucial for achieving the goal of reducing energy expenditure21. Usman, Nwani and Ozkan22 have indicated that household energy efficiency can play a significant role in the clean electricity transition in the United States by reducing emissions and energy expenditure. Moreover, energy expenditure specifically for reducing carbon emissions is another variable to be considered in the management of carbon dioxide emissions. et al.23 have suggested CO2 capture and utilisation for CO2 disposal in an effective and cost-efficient manner. Carbon dioxide emission reduction models with minimal energy cost are the objective of many empirical and innovative research studies. Based on a detailed study of energy expenditure and associated CO2 emissions in the United Kingdom, Chitnis and Hunt24 have expressed the opinion that measures like taxes can be effective for reducing future energy expenditure in the economy.

Carbon dioxide emissions from power plants are a significant issue that needs to be addressed in emission management. Unrestricted energy expenditure, especially on unclean, may enhance carbon emissions. Similarly, technology also plays a significant role in controlling carbon emissions through energy expenditure25. Researchers such as Janssen and De Vries25 and Xu et al.26 share the opinion that technological innovations and policy measures are necessary for achieving emission goals and reducing energy expenditure. Horn and Steinberg27 have suggested a zero-emission power plant with the lowest energy expenditure. Similarly, Mori et al.28 have suggested a power plant fitted with a pre-combustion carbon dioxide removal system with limited energy expenditure.

Improving building energy efficiency through building reforms and reconstruction can be one of the best solutions for reducing energy expenditure and carbon emissions29. The sustainability of natural hazard mitigation measures is essential, as repair or reconstruction actions have a significant impact on energy expenditure and emissions30. The use of thin films can be an effective measure for energy savings and reducing carbon dioxide emissions in buildings31. User behaviour management can also be a strategy for reducing energy expenditure and carbon emissions32.

Biofuels are another alternative for significantly reducing carbon emissions from energy expenditure33,34,35. Klein36 and Zschernig37 have highlighted the potential of using power-heat-coupling (KWK) facilities to reduce carbon emissions and energy expenditure. Researchers, such as Labreuche et al.38, believe that no-tillage agricultural methods can be highly effective in reducing energy consumption, energy expenditure, and carbon dioxide emissions, while also improving energy balance. Mayyas et al.39 have recommended lightweight vehicle design for reducing energy expenditure and carbon emissions.

Carbon dioxide emission and energy security index

In addition to traditional measures to capture energy security, the “energy security index” is an innovative measure to assess the energy security of economies. The energy security index is relevant to carbon reduction. Researchers, such as Liu et al.40, consider the energy security index a suitable measure of correlated energy security about carbon emissions. Firdaus et al.41 utilised energy security data to assess the energy security of the Indonesian economy. Similarly, Golušin, Schlör, and Hake42 have discussed “the Economic index of energy security” to capture all costs and estimations related to energy consumption. The research on energy security in Japan analysed energy security using supporting parameters like the energy supply security: dependency index, intensity index, local production index, and composite index43. Similarly, the energy security performance of selected commonwealth nations was studied using the parameters of energy availability, energy affordability, energy and economic efficiency, and environmental stewardship.

Carbon dioxide emission and economic policy uncertainty

The empirical research using the Panel Pooled Mean Group-Autoregressive Distributed lag model (PMG-ARDL), among resource-rich economies, by Adams et al.44, has identified long-run cointegration between economic policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emission, and the results of panel causality analysis indicated a bidirectional relationship between monetary policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emission.

The empirical study by Adedoyin et al.45 on 32 sub-Saharan nations, spanning the period from 1996 to 2014, has shown that economic policy can enhance carbon emissions, and the moderation of economic policy uncertainty is essential for reducing emissions in this region. The empirical results from a study based on OECD nations show a positive association between economic policy uncertainty and carbon emissions in PMG-ARDL estimation. The Dumitrescu and Hurlin causality results indicate that one-way causality exists between CO2 emissions and economic policy uncertainty. The positive impact of EPU on carbon emissions is also stated in the works of Ali et al.46,47, and48. The results of49 have identified a positive relationship between EPU and carbon emissions, indicating a 0.047% increase in CO2 emissions in developing countries for every one per cent increase in EPU. The empirical study conducted in both developed and developing economies, using the ARDL model by50, has indicated a positive impact of EPU on carbon emissions in both sets of economies. The other studies that identified the positive effects of economic policy uncertainty on carbon emissions include the works of51,52,53,54,55,56,57 and58.

The results of the ARDL simulation model-based study on the Chinese economy, conducted by Abbasi and Adedoyin59, have shown a statistically insignificant relationship between economic policy uncertainty and CO2 emissions. The results of a study by Liu and Zhang60 on the above nexus in the Chinese economy, as well as similar research on the same nexus by Khan61, have also found insignificance in the relationship between EPU and carbon emissions.

A study on the nexus between economic policy uncertainty and carbon dioxide emissions among the top ten carbon-emitting nations, using the PMG-ARDL modelling approach, has identified that the world uncertainty index (WUI) affects CO2 emissions in both the short and long run. In the short term, a 1% increase in economic policy uncertainty leads to a 0.11% decrease in carbon emissions. In the long run, a 1% rise in economic policy uncertainty leads to a 0.12% increase in carbon emissions. Researchers such as Chen, Shen, and Wang 3 have empirical evidence of the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty on carbon emissions, indicating that a higher level of EPU results in lower per capita carbon emissions, especially in emerging economies. Similarly, the adverse impacts of EPU on carbon emissions are indicated in the works of Syed et al.62,63, and64. The Autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) bound test, by Adedoyin and Zakari65, using data from 1985 to 2017 for the UK economy, has found a short-term reduction in carbon emissions due to economic policy uncertainty.

Data and methodology

Data

We have expanded the explanation for converting annual data to monthly frequency using the quadratic match-sum method. This method was chosen because it ensures that the monthly interpolated values aggregate exactly to the original annual totals, preserving the integral structure of the data. Additionally, it maintains a smooth temporal transition, which is particularly suited for economic and environmental indicators that typically follow gradual trends rather than abrupt changes. This ensures better compatibility with non-parametric estimations where data smoothness is crucial. The present study utilizes data collected from various sources for the selected indicators summarized in (Table 1). The annual data is collected from 1985 to 2022.

To explore the dynamics of carbon dioxide emissions (CE) from the perspective of the Energy Security Index (ESI), Energy Expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU), we consider the following econometric model:

To ensure the data smoothing and remove the inherent heteroskedasticity of the dataset under study, the dataset was log-transformed. The annual frequency of the time series variables was converted to monthly frequency (January 1985–December 2022) via the quadratic match-sum method to procure satisfactory dataset observations to perform empirical analysis66,67.

The selection of the 1985–2022 period is based on two key rationales. Firstly, 1985 marks the earliest availability of consistent and reliable data for the core indicators (Energy Security Index, Energy Expenditure, Economic Policy Uncertainty, and Carbon Emissions) across all selected sources. Secondly, this time frame captures multiple economic cycles, energy policy reforms, and climate action milestones, including significant U.S. environmental regulations and energy transitions that impact carbon emissions. This range allows a robust assessment of long-term dynamics and structural shifts in the energy-environment-policy nexus.

Methodology

Quantile regression—particularly the multivariate quantile-on-quantile regression (QQR)—is employed in this study due to its ability to capture non-linear, asymmetric relationships that vary across different quantiles of the distributions of both dependent and independent variables. Given the non-normality and heteroskedasticity observed in the data, traditional mean-based regression models would fail to uncover the underlying distributional dependencies. QQR is especially suitable for understanding how the impact of energy-related and policy uncertainty indicators on carbon emissions changes across different emission levels, which aligns with the study’s objective of revealing nuanced, tail-specific dynamics rather than average effects.

The popularly applied Quantile on Quantile regression methodology68 is a bivariate non-parametric approach to assess the relationship between the quantiles of the dependent time series variable and those of the independent time series variable’s quantiles. The methodology captures the underlying non-linearity and non-normality of the dataset, providing robust estimates. The general Quantile-on-Quantile regression model for the relationship between q-quantile of the dependent time series variable Y and p-quantile of the independent time series variable X is represented in Eq. (2).

wherein the quantile grid range is given by (0,0.95) and represents the error term. Equation (2) captures the entire dependence structure between time series Y and X through their respective distributions.

As discussed, the QQR is a bivariate regression analysis methodology and may ignore other important factors affecting the dependent time series variable. Recently, the methodology was modified by69 to incorporate multiple (> 2) independent time series variables. The new methodology captures the dependence between quantiles of dependent time series variables and multiple (> 2) independent time series variables thereby capturing the pure effect of each of the independent variables adjusted to the effect of other time series variables.

The multivariate QQR model for dependent time series Z and the series of independent time series variables, \({(X}_{1},\dots ,{X}_{N})\), for N > 2, across quantiles in the grid (0,0.95) is given by:

where \(\left({p}_{1},\dots ,{p}_{N}\right)\) represents the quantiles of \({(X}_{1},\dots ,{X}_{N})\) respectively and \(q\) represents the quantile of the time series variable Z. The bandwidth was chosen to be 0.05. The modified model for our study variables is given by

Robustness tests

We further validate the strength and robustness of our proposed MQQR model by comparing it with standard quantile regression (QR) and applying kernel-based regularized least squares (KRLS), a machine learning-based method that confirms the non-linear and asymmetric relationships our method reveals. To verify the validity of our multivariate quantile on quantile estimates two robustness tests were applied:

Multivariate non-parametric quantile on quantile regression estimates Vs quantile regression estimates

Traditionally the widely used linear quantile regression model70 is applied to check the reliability of Bi-variate Quantile on Quantile regression. The process involves fitting the qth conditional quantile of dependent time series variable, Y, on the independent time series variable X with the linear quantile regression defined by:

where parameter \({\beta }_{0}^{q}={\beta }_{0}\) is the intercept and the regression estimator of the slope, \({\beta }_{1}^{q}={\beta }_{1}\) is a function of q.

The bi-variate QQR estimates decompose QR estimates and the relationship between QR and QQR estimates in general is given by the following:

The suitability of the fit indicated if the averaged QQR estimates are equal to QR estimates for appropriate model fit.

Similarly applying the same approach, the robust fit of our Multivariate Quantile on Quantile regression estimates is indicated if the averaged multivariate QQR estimates given in Eq. (8) for the model defined in Eq. (4) are equivalent to the multivariate Quantile regression estimates defined in Eq. (7)

Machine learning algorithm—kernel based regularized least squares (KRLS)

The non-parametric machine learning method, KRLS71, is employed to detect non-linear relationships among the time series indicators, independent of linearity or the functional form of the model. The methodology is efficient in determining the asymmetric effect (s) of the set of independent time series indicators on the dependent time series indicator.

The KRLS methodology involves estimating the function given by

Which can be re-defined as

where, kernel \(k({x}_{i},{x}_{j})\) is estimated by Gaussian kernel given as:

The choice coefficients (d) are similar to the \({\beta }_{i}\) coefficients in linear regression.

The problem of choosing \({d}_{i}\) is resolved by the method of regularization and the Eq. (9) reduces to:

The matrix K is a symmetric and positive semi-definite. In general, the weights, d, are chosen by applying Tikhonov regularization problem given by

With

The best-fitting approximation is given by \({{Y}^{*}=Kd}^{*}\)

The flow of empirical analysis is represented in (Fig. 3).

Empirical analysis

The descriptive statistics and test of normality are summarized in (Table 2). All the variables were observed to be non-normally distributed as per the results of Jarque Bera’s test of normality.

The results of stationarity tests: augmented dickey-fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) unit root tests performed at the level and first difference are reported in (Table 3). The results of unit roots analysis indicated all the variables to be stationary in first order.

The results of the BDS test of non-linearity are summarized in Table 4 for embedding dimension (m) = 2, 3, 4 & 5. The results indicate that all the variables were non-linearly distributed at a 5% level of significance.

The results from the BDS test and Jarque–Bera tests depict the variables under exhibit non-linearity and non-normality and hence Multivariate Quantile on Quantile Regression is one of the best techniques for analysis.

Further, the non-parametric multivariate quantile on quantile (QQR) regression is applied to explore the effect of the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on the carbon-di-oxide emissions (CE).

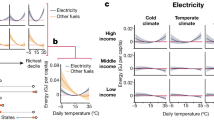

The traditional bivariate QQR is also applied, and the graphs of comparison are plotted and presented in Fig. 4 for comparisons.

The graphs presented in Fig. 4 depict the impacts of the Energy security index (ESI), Energy Expenditure (EE), and Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) on Carbon-di-oxide Emissions (CE) is different for the multivariate model \(CE=f\left(ESI,EE,EPU\right)\) as compared to the bivariate models \(CE=f(ESI)\), \(CE=f(EE)\) and \(CE=f(EPU)\).

These results throw insight into the fact that how misleading the results can be if the effects of other factors are not considered. Further, the multivariate QQR estimations indicate that the effects of ESI, EE, and EPU are non-linear and asymmetric.

Figure 4a depicts that the effect of the energy security index (ESI) on carbon dioxide emissions (CE) was observed to be positive for the quantile range [0.05–0.30] and at upper tails [0.9–0.95] of CE emissions while for quantile range [0.35–0.85] the impact was observed to be negative. The strength of negative correlation was observed in the range (−0.03 to −0.09), indicating a weak correlation. In contrast, that of positive correlation was observed to be (0.18 to 0.35), suggesting that, overall, the positive impact of the energy security index was observed on Carbon dioxide emissions. The effects of ESI on CE were observed to be significant for quantiles (0.1,0.15) based on the results of Multivariate Quantile regression analysis.

Figure 4b depicts that the effect of energy expenditure (EE) on carbon dioxide emissions (CE) was observed to be positive for all quantiles of CE emissions and negative only for upper quantiles [0.85 -0.95] of EE. The strength of negative correlation was observed in the range (-0.037 to -0.057), indicating a weak correlation, while that of positive correlation was observed to be (0.02 to 0.18), indicating an overall positive impact of energy expenditure on Carbon dioxide emissions. The effects of EE on CE were observed to be significant for all quantiles (0.20–0.90) based on the results of multivariate quantile regression analysis.

Figure 4c depicts the effect of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on carbon dioxide emissions (CE), positive for quantile [0.5,0.55] and at quantile [0.85–0.95] of CE emissions. In contrast, for other quantiles, the impact was observed to be mostly negative. The strength of negative correlation was observed in the range (-0.00015 to -0.0008), indicating a weak correlation, while that of positive correlation was observed to be (0 to 0.00034), indicating that the overall positive impact of economic policy uncertainty was observed on Carbon dioxide emissions. The effect of EPU on CE was observed to be non-significant for all quantiles based on the results of multivariate quantile regression analysis.

To check the validity of the multivariate QQR estimates the robustness tests as stated above are applied.

-

1.

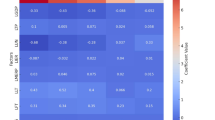

Figure 5 illustrates the multivariate QR slope coefficients and the averaged multivariate QQR estimates across the quantiles of carbon dioxide emissions (CE) on the quantile grid (0, 0.95). The trend of both multivariate QR and QQR estimates is observed to be similar, which confirms the validity of the multivariate QQR results.

-

2.

Secondly, the machine learning algorithm, Kernel-based regularised least squares (KRLS), was applied to the dataset. The pointwise marginal effects of the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) across data points of carbon dioxide emissions (CE) are presented in Fig. 6, while the computed average marginal estimates of these time series indicators on Carbon dioxide emissions (CE) are summarised in (Table 5).

The results summarized in Table 5 indicate that ESI, EE, and EPU have a significant nonlinear impact on CE. The effect of the Energy Security Index is observed to be negative on Carbon dioxide emissions, with a 1% increase in ESI resulting in a decrease of approximately 0.33% in emissions. Similarly, the impact of Energy Expenditure was observed to be positive, indicating a 1% increase in EE, causing Emissions to increase significantly by 0.53%. In contrast, economic policy uncertainty was observed to have a significant negative impact on emissions, with a 1% increase in EPU resulting in a 0.11% decrease in emissions. The overall R2 was observed to be 79% indicating a good fit at a 5% level of significance.

Discussion

This research has empirically tested the influence of “energy security index”, energy expenditure”, and “economic policy uncertainty” on carbon dioxide emissions from the United States of America, from 1985 to 2022, using a novel non-parametric multivariate quantile on quantile regression. Additionally, the results of Multivariate Quantile Regression are compared with those of traditional bivariate quantile regression. A significant difference has been observed by comparing the results of “traditional bivariate Quantile on Quantile Regression” and “multivariate quantile on quantile regression”.

For the energy security index (ESI), we now highlight that the limited direct literature on ESI’s impact on carbon emissions has been supplemented by discussing methodological contributions, such as the application of multivariate QQR, offering a nuanced understanding not previously captured.

For energy expenditure (EE), we have expanded comparisons with previous works including Horn and Steinberg27, Mori et al.28, and Mayyas et al.39, affirming the consistency of our results with the general consensus that lower energy expenditure contributes to reduced emissions. At the same time, we acknowledged that our findings differ from Dehdar et al.20, and provided possible reasons for these discrepancies (refer to paragraph 3, Section “Discussion”).

Regarding economic policy uncertainty (EPU), we have critically discussed the bifurcation in prior research findings—some of which indicate a positive link (e.g., Adedoyin et al.45,50,51), while others report a negative or insignificant relationship (e.g., Abbasi and Adedoyin59, Adedoyin and Zakari65). We placed our results within this context, emphasizing the contribution of our non-linear, quantile-based approach in reconciling these differing conclusions by revealing asymmetric effects across quantiles.

The results of traditional bivariate Quantile on Quantile Regression” on the dynamics between the energy security index and carbon dioxide emissions show the overall positive impact of the energy security index on carbon dioxide emissions, especially on the quantile range [0.05–0.30] and at upper tails [0.9–0.95]. The results of “multivariate quantile on quantile regression” on the dynamics between the energy security index and carbon dioxide emissions show a significant impact of the energy security index on carbon dioxide emissions for quantiles (0.1 and 0.15). Minimal literature has directly addressed the nexus between the energy security index and carbon emissions.

The results of traditional bivariate Quantile on Quantile Regression” on the dynamics between Energy Expenditure and carbon dioxide emissions, observed a significant positive impact for all quantiles, except the upper quantiles [0.85 -0.95] of EE. The results of “Multivariate Quantile on Quantile Regression” on the dynamics between energy expenditure and carbon dioxide emissions show a significant impact of Energy Expenditure on carbon dioxide emissions for all quantiles (0.20–0.90). The findings on the above relation are in line with the findings of Horn and Steinberg27, Mori et al.28, Mayyas et al.25,39, and37, who discussed that carbon emissions can be reduced by reducing energy expenditure. The findings of33,34,35 are also in line with this paper. However, these results contradict the conclusions of Dehdar et al.20.

The results of traditional bivariate quantile on quantile regression” on the dynamics between economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and carbon dioxide emissions show the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on carbon dioxide emissions. The results of “Multivariate quantile on quantile regression”, on the dynamics between Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) and carbon dioxide emissions, show a significant impact of Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) on carbon dioxide emissions. The results align with the findings of Adedoyin and Zakari3,62,63,65, and64, who reported a negative association between carbon emissions and EPU. Contradicting the above results, the findings of Abbasi and Adedoyin59,60,61 have obtained insignificance in the relation between EPU and carbon emission. Similarly, the results of this research contradict with findings of Adedoyin et al.45,46,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57, and47,48, and48 who has obtained a positive association between EPU and emissions.

The results of the robustness tests (machine learning algorithm: Kernel-based Regularised Least Squares; and multivariate QR slope coefficients) confirm the validity of the multivariate QQR estimates in this study. Moreover, the results of this empirical research have identified the significant non-linear impact of ESI, EE, and EPU on CE. The negative effects of ESI on Carbon dioxide emissions can cause a decrease in emissions of 0.33% for every 1% increase in ESI. Approximately. Similarly, a 1% increase in EE can result in a 0.53% increase in emissions, indicating a positive impact. The EPU has a significant negative effect on emissions, with a 1% increase in EPU causing emissions to decrease by 0.11%. We emphasize how our model, when compared with bivariate QQR, produces markedly different results, highlighting the significance of considering joint impacts rather than isolated ones. This comparison supports the added explanatory power and accuracy of the MQQR.

Policy relevance of non-linear findings

The observed non-linear effects of the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on carbon emissions offer significant insights for U.S. climate and energy policymaking. The finding that improvements in ESI are associated with reductions in CO₂ emissions—particularly at moderate to high quantiles—supports policies aimed at diversifying energy sources, improving grid resilience, and investing in renewable infrastructure. This aligns well with the U.S. Department of Energy’s emphasis on energy independence and security in recent policy frameworks.

Furthermore, the positive relationship between EE and emissions at most quantiles suggests that increasing energy consumption, particularly if sourced from non-renewables, undermines emission reduction efforts. These findings reinforce the importance of demand-side management policies such as energy efficiency standards, tax incentives for green technologies, and carbon pricing mechanisms.

The asymmetric and predominantly negative impact of EPU on emissions reveals complex behavioral and investment dynamics. While uncertainty may temporarily suppress emissions due to reduced economic activity or postponed energy investments, relying on elevated uncertainty is not a sustainable or desirable policy strategy. Instead, stable and transparent policy environments should be prioritized to ensure long-term emission reduction through informed investments in clean technologies.

Collectively, our findings highlight the necessity for nuanced, quantile-specific policy interventions that go beyond linear assumptions, thereby offering empirical support for more flexible and adaptive climate governance in the United States.

Conclusion

This study explored the impact of the energy security index (ESI), energy expenditure (EE), and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on carbon dioxide emissions (CE) in the United States from 1985 to 2022. Using a novel non-parametric multivariate Quantile-on-Quantile regression approach, the study revealed significant non-linear and asymmetric relationships between the variables. Robustness tests confirmed the model’s validity. Notably, ESI exhibited a negative association with emissions, EE showed a positive effect, and EPU demonstrated a complex but generally negative influence. These empirical insights build upon the literature review, data analysis, and methodology discussed in the previous chapters.

Policy implications

The United States of America is making positive progress towards its ambitious goal of halving carbon emissions by 2030. Holistic approaches are employed for reducing carbon emissions. Diversified factors influence the carbon emission targets. This paper analyses the impact of carbon emissions in the USA, examining the variables of energy security index, energy expenditure, and economic policy uncertainty.

The results of this paper indicate a significant non-linear relationship between the energy security index, energy expenditure, economic policy uncertainty, and carbon dioxide emissions. Moreover, the results indicate the adverse effects of ESI on Carbon dioxide emissions, the positive impact of energy expenditure on carbon emissions, and that EPU has a significant adverse effect on emissions. The US planners and administrators should focus on improving energy security, implementing interventions to achieve higher positions in the energy security index, reducing energy expenditure, and effectively managing economic policy uncertainties. Economic policy uncertainty has a negative relationship with emissions; therefore, high EPU cannot be encouraged as a means of reducing emissions. This policy recommends prioritising energy security and energy expenditure as key aspects for the US economy.

The US economy needs to address several challenges in managing the energy security index, energy expenditure, and economic policy uncertainty for reducing carbon emissions. Energy efficiency and energy conservation should focus on enhancing energy security and reducing energy expenditure. The dependency on unclean fuels should be reduced by promoting renewable energy sources and switching to modern power generation plants to lower emissions. Additionally, building reforms can be planned to reduce energy expenditure. The scope for carbon taxing and enhancing user awareness for energy conservation, energy security, and limiting energy wastage can be planned. The US economy is the biggest in the world. Economic policies play a significant role in the US economy. However, a negative association between EPU and carbon emissions suggests that higher EPU is required to reduce emissions, which cannot be accommodated.

Policy implications suggest that U.S. planners should strengthen energy security, reduce unnecessary energy expenditure, and manage policy uncertainty carefully to meet emission reduction targets. Interventions promoting clean energy adoption, energy-efficient technologies, and building reforms can help achieve sustainable environmental outcomes.

Limitations and future research

This paper is not free from limitations. This paper does not focus on the challenges associated with the management of the nexus between the carbon emission of the USA and the variables, energy security index, energy expenditure, and economic policy uncertainty, which can be taken up in future research. This study is limited to the U.S. context and focuses on three key variables. It does not address the operational challenges in managing these indicators or incorporate other potentially influential factors such as technological innovation, environmental regulation, or renewable energy consumption.

This paper on the nexus between the carbon emissions of the USA and the variables of energy security index, energy expenditure, and economic policy uncertainty has significant scope for further research. The discussion on promising themes for additional research on this topic has academic, administrative, and research benefits. The model of this research can be replicated in other economies or groups of nations to gain a better understanding of the relationship between these variables.

About research on energy security and the energy security index, future researchers can focus on measures to enhance and diversify energy resources. Researchers can evaluate the alternatives for improving energy security. Similarly, researchers can plan for cleaning the energy structure of the US economy as well. Promising research themes are available for further exploration, particularly those related to technology integration in power sectors and building reforms aimed at energy reduction. User awareness is of great importance, and researchers can work on developing interventions to educate and motivate users to consume less energy and promote smart energy usage. Researchers can also work on developing strategies for better management of economic policy uncertainty factors for reducing carbon emissions, without compromising economic growth. The proposed model can be extended to other economies or regional blocs to examine its generalizability. Future studies may also integrate additional covariates—such as climate policy stringency, green finance metrics, or innovation indices—to enrich the analysis and policy relevance. Further, exploring sector-specific emissions could provide a more granular understanding of dynamics within industry, transportation, or residential energy use.

Data availability

The data will be available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Zhang, M. et al. Does economic policy uncertainty, energy transition and ecological innovation affect environmental degradation in the United States?. Econ. Res. Ekonomska Istrazivanja 36 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2023.2177698 (2023).

Wang, C., Abbasi, K. R., Irfan, M., Ben-Salha, O. & Bandyopadhyay, A. Navigating sustainability in the US: A comprehensive analysis of green energy, eco-innovation, and economic policy uncertainty on sectoral CO2 emissions. Energy Rep. 11, 5286–5299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2024.05.014 (2024).

Chen, Y., Shen, X. & Wang, L. The heterogeneity research of the impact of EPU on environmental pollution: empirical evidence based on 15 countries. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084166 (2021).

Shabir, M., Ali, M., Hashmi, S. H. & Bakhsh, S. Heterogeneous effects of economic policy uncertainty and foreign direct investment on environmental quality: cross-country evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (2), 2737–2752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15715-3 (2022).

Atsu, F. & Adams, S. Energy consumption, finance, and climate change: Does policy uncertainty matter?. Econ. Anal. Policy 70, 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.03.013 (2021).

Nakhli, M. S., Shahbaz, M., Ben Jebli, M. & Wang, S. Nexus between economic policy uncertainty, renewable & non-renewable energy and carbon emissions: Contextual evidence in carbon neutrality dream of USA. Renew. Energy 185, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.046 (2022).

Wang, Q., Xiao, K. & Lu, Z. Does economic policy uncertainty affect CO2 emissions? Empirical evidence from the United States. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12 (21), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219108 (2020).

Danish, R. U. & Khan, S. U. D. Relationship between energy intensity andCO(2)emissions: Does economic policy matter?. Sustain. Dev. 28 (5), 1457–1464. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2098 (2020).

Pirgaip, B. & Dinçergök, B. Economic policy uncertainty, energy consumption and carbon emissions in G7 countries: evidence from a panel Granger causality analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (24), 30050–30066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08642-2 (2020).

Ahmed, Z., Cary, M., Shahbaz, M. & Vo, X. V. Asymmetric nexus between economic policy uncertainty, renewable energy technology budgets, and environmental sustainability: Evidence from the United States. J. Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127723 (2021).

Johnsen, T. A. & Unander, F. F. Norwegian residential energy demand: Coordinated use of a system engineering and a macroeconomic model. Model. Identif. Control 17 (3), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.4173/mic.1996.3.2 (1996).

Kilinc-Ata, N., Camkaya, S., Akca, M., & Topal, S. The impact of uncertainty in economic policy on the load capacity factors in China and the United States (US): New evidence from novel Fourier bootstrap ARDL approach. J. Sustain. Res. 7 (1), (2025).

Vorwald, R. New energy technologies for high-performance buildings. Energy Eng. J. Assoc. Energy Eng. 108 (2), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01998595.2011.10389016 (2011).

Burtraw, D., Walls, M. & Blonz, J. Distributional Impacts of Carbon Pricing Policies in the Electricity Sector (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Syed, Q. R. & Bouri, E. Impact of economic policy uncertainty on CO2 emissions in the US: Evidence from bootstrap ARDL approach. J. Public Aff. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2595 (2022).

Franki, V. & Viskovic, A. Energy security, policy and technology in South East Europe: Presenting and applying an energy security index to Croatia. Energy 90 (1), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.07.087 (2015).

Sovacool, B. K. The methodological challenges of creating a comprehensive energy security index. Energy Policy 48, 835–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.02.017 (2012).

Erahman, Q. F., Purwanto, W. W., Sudibandriyo, M. & Hidayatno, A. An assessment of Indonesia’s energy security index and comparison with seventy countries. Energy 111, 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.05.100 (2016).

Gasser, P. A review on energy security indices to compare country performances. Energy Policy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111339 (2020).

Dehdar, F., Fuinhas, J. A., Karimi Alavijeh, N., Nazeer, N. & Zangoei, S. Investigating the determinants of carbon emissions in the USA: a state-level analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (9), 23023–23034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23831-x (2023).

Suerkemper, F. et al. Benefits of energy efficiency policies in Thailand: an ex-ante evaluation of the energy efficiency action plan. Energy Effic. 9 (1), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-015-9357-z (2016).

Usman, O., Nwani, C. & Ozkan, O. Role of household energy efficiency in shaping policy directives toward clean electricity transition in the United States: A nonparametric multivariate QQR approach. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2024.103741 (2024).

Xie, H. et al. Simultaneous mineralization of CO2 and recovery of soluble potassium using earth-abundant potassium feldspar. Chin. Sci. Bull. 58 (1), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-012-5466-7 (2013).

Chitnis, M. & Hunt, L. C. What drives the change in UK household energy expenditure and associated CO2 emissions? Implication and forecast to 2020. Appl. Energy 94, 202–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.01.005 (2012).

Janssen, M. A. & De Vries, B. Climate change policy targets and the role of technological change. Clim. Change 46 (1–2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005661220604 (2000).

Xu, G. et al. Techno-economic analysis and optimization of the heat recovery of utility boiler flue gas. Appl. Energy 112, 907–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.04.048 (2013).

Horn, F. L. & Steinberg, M. Control of carbon dioxide emissions from a power plant (and use in enhanced oil recovery). Fuel 61 (5), 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-2361(82)90064-3 (1982).

Mori, Y., Masutani, S. M., Nihous, G. C., Vega, L. A. & Kinoshita, C. M. Pre-combustion removal of carbon dioxide from hydrocarbon-fuelled power plants. Fuel 72 (9), 1293–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-2361(93)90128-O (1993).

Ilić, M. Z. Revitalization of architectural objects by means of energy efficiency improvement: An economic case analysis. Energy Build 93, 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.02.012 (2015).

Padgett, J. E. & Tapia, C. Sustainability of natural hazard risk mitigation: Life cycle analysis of environmental indicators for bridge infrastructure. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 19 (4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000138 (2013).

Yousif, K. M. Energy savings and Environmental Benefits from Solar Window Film for Buildings in Kurdistan of Iraq (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Huang, H., Wang, H., Hu, Y. J., Li, C. & Wang, X. Optimal plan for energy conservation and CO2 emissions reduction of public buildings considering users’ behavior: case of China. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.125037 (2022).

Herrera, C. G. Fatty acid methyl esters as diesel fuel. Economic, ecological and energetic implications; [Ésteres metílicos de ácidos grasos como carburantes. Implicaciones económicas, ecológicas y energéticas]. Grasas Aceites 46 (2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.3989/gya.1995.v46.i2.914 (1995).

Wu, H.-L. et al. Experimental research on gasoline engine fueled with biomass pyrolysis oil upgraded in supercritical ethanol. (Zhejiang Daxue Xuebao)/J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 49 (1), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.3785/j.issn.1008-973X.2015.01.020 (2015).

Kupczyk, A., Tucki, K., Sikora, M., Zubrzycka, M. & Bączyk, A. Comparison of energy expenditures and CO2 emissions in the process for manufacturing compressed methane from corn silage and manure and for production of bioethanol from corn; [Porównanie nakładów energetycznych i emisji CO2 w procesach wytwarzania sprężonego metanu z kiszonki kukurydzianej i gnojowicy oraz bioetanolu z kukurydzy]. Przem. Chem. 95 (8), 1624–1629. https://doi.org/10.15199/62.2016.8.43 (2016).

Klein, H. Power-heat-refrigeration-coupling. KWKK: A module for sustainment?; [KWKK. Kraft-wärme-kälte-kopplung: Ein modul der nachhaltigkeit?]. BWK - Energie-Fachmagazin 53 (1–2), 51–53 (2001).

Zschernig, J. Power-heat-coupling. Power-heat-coupling in the pluralistic heating market; [Kraft-wärme-kopplung. Kraft-wärme-kopplung im pluralistischem wärmemarkt]. BWK - Energie-Fachmagazin 53 (3), 59–63 (2001).

Labreuche, J., Lellahi, A., Malaval, C. & Germon, J.-C. Impact of no-tillage agricultural methods on the energy balance and the greenhouse gas balance of cropping systems; [Impact des techniques culturales sans labour (TCSL) sur le bilan énergétique et le bilan des gaz à effet de serre des systèmes de culture]. Cahiers Agric. 20 (3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1684/agr.2011.0492 (2011).

Mayyas, A., Omar, M., Hayajneh, M. & Mayyas, A. R. Vehicle’s lightweight design vs. electrification from life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean Prod. 167, 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.145 (2017).

Liu, J. L., Fu, J., Wong, S. S. & Bashir, S. Energy security and sustainability for the European union after/during the Ukraine Crisis: A perspective. Energy Fuels https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c02556 (2023).

Firdaus, A., Machfud, A. S. & Achsani, N. A. Measuring Indonesia’s energy security level in the context of biodiesel agroindustry. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 9 (6), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.8255 (2019).

Golušin, M., Schlör, H. & Hake, J.-F. Case study: Economic Index of Energy Security - Monetization of all Costs Approach (Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2013).

Ozkan, F., Erdal, L., Pektas, A. O. & Ozkan, O. The energy security of Japan: Causality analyses. Energy Sour. Part B 11 (11), 1006–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567249.2014.931485 (2016).

Adams, S., Adedoyin, F., Olaniran, E. & Bekun, F. V. Energy consumption, economic policy uncertainty and carbon emissions; causality evidence from resource rich economies. Econ. Anal. Policy 68, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.09.012 (2020).

Adedoyin, F. F., Ozturk, I., Agboola, M. O., Agboola, P. O. & Bekun, F. V. The implications of renewable and non-renewable energy generating in Sub-Saharan Africa: The role of economic policy uncertainties. Energy Policy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112115 (2021).

Ali, S., Jiang, J., Ahmad, M., Usman, O. & Ahmed, Z. A path towards carbon mitigation amidst economic policy uncertainty in BRICS: an advanced panel analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20004-8 (2022).

Khan, Y., Hassan, T., Kirikkaleli, D., Xiuqin, Z. & Shukai, C. The impact of economic policy uncertainty on carbon emissions: evaluating the role of foreign capital investment and renewable energy in East Asian economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (13), 18527–18545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17000-9 (2022).

Xue, C., Shahbaz, M., Ahmed, Z., Ahmad, M. & Sinha, A. Clean energy consumption, economic growth, and environmental sustainability: What is the role of economic policy uncertainty?. Renew. Energy 184, 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.006 (2022).

Borojo, D. G., Yushi, J. & Miao, M. The impacts of economic policy uncertainties on carbon dioxide emissions of emerging and low-income developing countries: the moderating role of institutional quality. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 18 (11), 5408–5431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2021-1044 (2023).

Iqbal, M., Chand, S. & Ul Haq, Z. Economic policy uncertainty and CO2 emissions: a comparative analysis of developed and developing nations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (6), 15034–15043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23115-4 (2023).

Ayad, H., Sari-Hassoun, S. E., Usman, M. & Ahmad, P. The impact of economic uncertainty, economic growth and energy consumption on environmental degradation in MENA countries: Fresh insights from multiple thresholds NARDL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (1), 1806–1824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22256-w (2023).

Ali, K., Du, J., Kirikkaleli, D., Olah, J. & Altuntas, M. Do green technological innovation, financial development, economic policy uncertainty, and institutional quality matter for environmental sustainability?. All Earth 35 (1), 82–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/27669645.2023.2200330 (2023).

Farooq, U., Gillani, S., Subhani, B. H. & Shafiq, M. N. Economic policy uncertainty and environmental degradation: the moderating role of political stability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (7), 18785–18797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23479-7 (2023).

Balsalobre-Lorente, D., Nur, T., Topaloglu, E. E. & Evcimen, C. The dampening effect of geopolitical risk and economic policy uncertainty in the linkage between economic complexity and environmental degradation in the G-20. J. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119679 (2024).

Mushtaq, M. et al. How does economic policy uncertainty impact CO2 emissions? Investigating investment’s role across 22 economies (1997–2021). Energy Rep. 11, 5083–5091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2024.04.069 (2024).

Cui, X. et al. Do geopolitical risk and economic policy uncertainty cause CO2 emissions in BRICS? The role of institutional quality and energy productivity. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 38 (5), 1685–1699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-023-02646-3 (2024).

Owusu, S. M., Chuanbo, F. & Qiao, H. Examining economic policy uncertainty’s impact on environmental sustainability: Insights from nordic nations. J. Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141688 (2024).

Wei, F., Sial, M. S., Haider, S. N. & Matac, L. M. Nexus of economic policy uncertainty, economic expansion and clean energy consumption and their role in carbon neutrality of emerging economies. Geol. J. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.4688 (2023).

Dai, P. F., Xiong, X. & Zhou, W. X. A global economic policy uncertainty index from principal component analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 40, 101686 (2021).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, Z. How does economic policy uncertainty affect CO2 emissions? A regional analysis in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (3), 4276–4290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15936-6 (2022).

Khan, Q. R. From industrialization to dehumanization: understanding the deriving forces of environment and implications for sustainable development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30 (59), 123396–123411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30983-x (2023).

Syed, Q. R., Bhowmik, R., Adedoyin, F. F., Alola, A. A. & Khalid, N. Do economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical risk surge CO2 emissions? New insights from panel quantile regression approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (19), 27845–27861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17707-9 (2022).

Ayhan, F., Kartal, M. T., Kilic Depren, S. & Depren, O. Asymmetric effect of economic policy uncertainty, political stability, energy consumption, and economic growth on CO2 emissions: evidence from G-7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25665-7 (2023).

Durani, F., Bhowmik, R., Sharif, A., Anwar, A. & Syed, Q. R. Role of economic uncertainty, financial development, natural resources, technology, and renewable energy in the environmental Phillips curve framework. J. Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138334 (2023).

Adedoyin, F. F. & Zakari, A. Energy consumption, economic expansion, and CO2 emission in the UK: The role of economic policy uncertainty. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140014 (2020).

Liguo, X., Ahmad, M. & Khattak, S. I. Impact of innovation in marine energy generation, distribution, or transmission-related technologies on carbon dioxide emissions in the United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 159, 112225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112225 (2022).

Shahbaz, M., Abbas Rizvi, S. K., Dong, K. & Vo, X. V. Fiscal decentralization as new determinant of renewable energy demand in China: The role of income inequality and urbanization. Renew. Energy 187, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.01.064 (2022).

Sim, N. & Zhou, H. Oil prices, US stock return, and the dependence between their quantiles. J. Bank Financ 55, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.01.013 (2015).

Alola, A. A., Özkan, O. & Usman, O. Examining crude oil price outlook amidst substitute energy price and household energy expenditure in the USA: A novel nonparametric multivariate QQR approach. Energy Econ. 120, 106613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106613 (2023).

Koenker, R. W. & Bassett, G. Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46 (1), 33–50 (1978).

Hainmueller, J. & Hazlett, C. Kernel regularized least squares: Reducing misspecification bias with a flexible and interpretable machine learning approach. Polit. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt019 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sanjeet Singh: Writing, Conceptualization, Pooja Bansal: Data collection, Analysis, Sireesha Nanduri: Writing, Investigation, Mohd Shukri Ab Yajid: Software, Methodology, Navin Kedia: Supervision, Review writing, Ati Priya: Writing, Investigation, S Srinadh Raju: Writing, Conceptualization, A Bhowmik: Methodology, Review writing,

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, S., Bansal, P., Nanduri, S. et al. Exploring CO2 emission dynamics in relation to energy security, expenditure and policy uncertainty using Quantile-on-Quantile regression: case study from USA. Sci Rep 15, 35647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19565-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19565-8