Abstract

Gears are subjected to external excitation alternating loads, and the Micro-Textured Meshing Interface (MTMI) will share larger contact stresses during the warship Power Rear Transmission System (PRTS) torsional process. The current elastoplastic interface load-bearing contact model ignores the time-dependent changes of textured element Micro-Convex Peaks (MCP) base diameter, which is usually regarded as a certain constant value, and which is extremely inconsistent with the time-varying characteristics of MCP matrix diameter of actual MTMI, which leading to the deviation of load-bearing analytical values determined by the current contact model from actual data. A generalized Thermo-Elastic Hydrodynamic Lubrication (TEHL) contact load-bearing model with Interface Micro Texture (IMT) is proposed, and the contact area between all MCPs across the MTMI is represented by the equivalent scale factor parameter, and the shape distribution density function is modified to ensure that the MCP is solved integrally. A mathematical model of meshing Anti-Scuffing Load-Bearing Capacity (ASLBC) in a TEHL steady state is derived to reveal the correlation between contact stiffness and damping of meshing MTMI under alternating loads influence, which provides a theoretical basis and data reference for homogeneous Interface Enriched Lubrication (IEL) effect improvement and meshing ASLBC enhancement of contact IMT for the PRTS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A micro-textured gear unit is the warship PRTS. High-speed and heavy-duty gear transmission system for large warship, as shown in Fig. 1. An excellent lubrication and load-bearing regulation of MTMI have been well recognized, teeth surface micro-texture seems to be a penalty area for gears, which is attributed to the traditional perception of similarity between meshing interface micro pitting and texturing units1,2. The gear surface micro-texturing is applied to the interface to modulate time-varying meshing stiffness and enhance lubrication enrichment effect, thereby improving meshing load-bearing performance3,4. The current elastoplastic interface load-bearing contact model ignores the time-dependent changes in the base diameter of the texturing MCP, which is usually recognized as a constant value, which is extremely inconsistent with the time-varying characteristics of the base diameter of the MCP elements in the actual MTMI, thus leading to the deviation of the load-bearing resolved values determined by the current contact model from the actual data.

As the core component for torque transmission, gears possess diverse sizes, high load-bearing capacity, and high efficiency, which are of vital importance in determining the reliability and accuracy of the PRTS5. In the case of the PRTS operating under special environments, it is confronted with extreme usage conditions such as high and low temperatures, deep-sea pressure, strong acids and alkalis and other extreme conditions of use. The maximum pressure in the deep sea reach over 200 to 300 MPa, which is 2000 to 3000 times that of atmospheric pressure. The marine environment brings challenges such as acid and alkali corrosion to PRTS.

The deep-sea gearbox is exposed to alternating environments of high temperature, high humidity, high salt fog and seawater spray for a long time in the alternating environment, which causes serious electrochemical corrosion problems6. Deep-sea gears are subjected to contact fatigue and scuffing load-bearing capacity in service, as shown in Fig. 2. High-end equipment requires gears with greater load-bearing capacity and serviceability, and controlling the load-bearing capacity of deep-sea gears has become critical. Although advanced processing technologies such as surface hardening and precision machining improve the gear load-bearing capacity, they still cannot meet the ever-increasing service life and load-bearing capacity requirements, and frequent equipment accidents caused by insufficient gear strength are common, which makes the gear load-bearing capacity become a key bottleneck restricting the performance and reliability of PRTS.

The gear directly affects the overall performance of the PRTS. The meshing domain, where the frictional heat causes a sharp increase in teeth surface temperature, leads to the rupture of the interfacial oil film layer and consequently lubrication failure. This results in rigid contact between the metal MTMI, an increase in the friction coefficient between the teeth surfaces, and a rapid rise in the instantaneous contact temperature of meshing interfaces. The gear profile and the lubrication state between the teeth surfaces change, and the metal teeth surfaces is torn off along the high-speed sliding direction, resulting in scuffing load-bearing failure7,8,9. Even short-term overloading, improper lubrication, or excessive temperature rise causes serious damage to the teeth profile and further deteriorate the lubrication state between the meshing interfaces. Considering the harsh real-time working conditions of warship PRTS, gear damage and failure often occur or originate from the microscopic interface of the teeth surfaces. Scuffing load-bearing fatigue of the MTMI frequently leads to gear lubrication failure. Traditional design methods, which are based on Hertzian contact theory and assumptions such as smooth surfaces, no lubrication, isothermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication, and homogeneous elastic materials, are no longer capable of accurately predicting the lubrication characteristics and load-bearing performance of gears in warship PRTS. Therefore, it is necessary to deeply explore the evolution of lubrication characteristics in heavily loaded line contact interfaces and the correlation mechanism with the load-bearing performance of MTMI. This will provide a scientific basis and theoretical reference for enhancing the TEHL characteristics of the meshing interfaces under real-time full working conditions of the PRTS and for accurately assessing the ASLBC of the MTMI.

The warship PRTS is a high-speed and heavy-load gear transmission system. The MTMI are typically in a mixed lubrication state characterized by the coexistence of boundary and thin-film fluid lubrication10,11,12. The state cannot generate a sufficient lubricating film to completely separate the MTMI. This is especially true under high dynamic operating conditions or during start-stop operations, where the characteristics of the MTMI have a significant impact on lubrication behavior and load-bearing capacity. The meshing pair interface consists of two parts: direct contact of MCP and the load-bearing capacity of the TEHL film13,14,15. The contact morphology IMT is a new idea and method to analyze the scientific issues related to gear lubrication and load-bearing capacity in warship PRTS. The lubrication and load-bearing effects in the meshing time domain process are not negligible16. The key technology is that the appropriate IMT can generate a coupling effect of “Secondary enrichment lubrication” and “Micro-hydrodynamic load-bearing”. However, the heat flux generated by alternating friction of the MTMI cause a significant increase in teeth temperature, which in turn alters the stable state mechanism of the warship PRTS meshing interface TEHL17,18,19. This includes multi-scale parameters such as IMT lubrication enrichment characteristics, time-varying thermoelastic deformation, transient thermal expansion, thermomechanical coupling of stress structure, interface morphology IMT configuration characteristics, and distribution density20.

In the field of warship PRTS research, an urgent and critical scientific issue that needs to be explored is how to reasonably design the IMT of MTMI under real-time full operating conditions to improve the IEL characteristics and enhance the key performance of ASLBC. It is also essential to construct a universal mathematical model for mixed lubrication of MTMI, simulate and solve the core variables, and verify and calibrate them through full operating condition experiments. This research aims to reveal the mechanism of the IEL effect of mixed TEHL meshing IMT and optimize the multi-scale parameter design of the micro-element configuration. Additionally, it seeks to explore the influence of mechanisms and patterns of the geometric characteristics and directional parameters of MTMI on IEL properties, in order to improve ASLBC to adapt to the high contact line loads during alternating meshing time domain. The research on the IEL mechanism and ASLBC of mixed TEHL meshing IMT is of great theoretical significance and practical application value for the development of the tribodynamics of MTMI in high-speed and heavy-load gear transmission systems.

Steady-state TEHL textured interface load-bearing contact modeling

Key assumptions and applicable conditions for the proposed model

The model assumes a linear-elastic half-space, thereby ignoring plastic deformation of interfacial materials and any non-uniform thermal expansion driven by temperature gradients. The lubricant is taken as incompressible and Newtonian; its pressure–viscosity response is captured by the Roelands equation, while shear-thinning is introduced via an equivalent scaling factor. Non-planar-interface density corrections are admissible only when the radius of curvature far exceeds the film thickness (surface-roughness wavelength > 10 h₀, with h₀ the central film thickness). Local cavitation arising from severe roughness is disregarded. Thermal-resistance differences between solid bodies are neglected, and a uniform heat-flux distribution is imposed within the contact zone. Model bounds are set by the following dimensionless limits:

-

Hertzian contact pressure ≤ 1.5 GPa (above which plastic deformation must be considered).

-

Entrainment velocity ∈ [0.1, 10] m s⁻1 (boundary-slip effects need validation at the lower end, and inertial terms must be coupled at the upper end).

-

RMS (Root-Mean-Square) roughness ≤ 0.3 µm and asperity slope < 0.1 (to prevent asperity penetration of the lubricant film).

-

Correction factor ∈ [0.8, 1.2]; nonlinear responses beyond this interval require experimental calibration.

The model deliberately excludes interface-failure regimes under extreme conditions (Hertzian pressure > 2.0 GPa, RMS roughness > 0.5 µm, or starved lubrication), for which coupling to elastoplastic deformation or mixed-lubrication models is necessary.

Constructing an interface load-bearing contact model based on fractal theory

The MTMI of the warship PRTS are in continuous contact, the actual micro-contact area is much smaller than the macroscopic theoretical meshing domain area. This research is based on the meshing IMT fractal theory and investigates the temporal variation of single MCP within load-bearing contact domain and unveiling the evolving trends of actual contact changes in MCP on non-macroscopically smooth interfaces. The mathematical relationship between the actual contact interface domain and the true MTMI loads are determined by solving the distribution density function of the differential MCP elements using integration. Figure 3 illustrates the mathematical model of the correlation between height deformation and individual differential MCP elements protrusions on the MTMI. The MCP elements deform transiently under the cyclic excitation loads on the textured interface, considering the different heights of the MCP elements and the different loads-bearing, the true deformation values of the MCP elements are limited within the range of \(0 - \delta\). The teeth profile of the meshing gear pair of a single MCP elements within the contact interface domain is usually approximated by a cosine function (with the single base length set as \(l\)). Based on the description of the three-dimensional profile characteristics of the MTMI using a bivariate function21,22,23, it is expressed as:

where, \(z\left( {x,y} \right)\) represents the height function of the three-dimensional textured interface profile (the profile height of a single MCP element), \(G\) is the amplitude of the height of the MCP elements of the MTM,\(D\) represents the fractal dimension,\(\varphi\) denotes a constant value that is not less than 1.0, \(\phi_{m,n}\) denotes a uniformly distributed random phase within the interval [0, 2π], generated by a random number generator. Its role is to ensure that the frequency components of the meshing interface profile do not spatially overlap.\(h\) is the sampling profile length of the MTMI (the diameter of the base of a single MCP element), \(M\) represents the number of overlapping regions of the interface profile, \(n\) is the distribution index of random frequency of the interface profile (where \(n_{\max }\) is the maximum value of the random frequency distribution index),\(n_{\max }\) is the random phase when interface profile is uniformly distributed.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, when the MCP of the textured contour are subjected to the interface normal contact pressure, the actual deformation height of the MCP is designated as \(\omega\), the distance between the apex of the MCP and its base is defined as \(\delta\), the base diameter of the MCP is represented as \(h\), the transverse contour diameter is denoted as \(h_{t}\), the actual contour diameter is \(h_{r}\), the transverse contact area \(a\) of a single MCP is described as:

where,\(\rho\) represents the radius of curvature of a single MCP, thereby allowing the calculation of the radius of curvature at position \(x = 0\) of the MCP (see Expression 2).

Based on the actual textured interface contact area and combined with related thermo-elastoplastic deformation studies24,25,26, it is demonstrated that when the textured interface is subjected to external alternating excitation loads, it inevitably coexists with a single MCP at the critical stage of elastic deformation. The critical deformation amount \(\omega_{l}\) of a single MCP is expressed as27:

where,\(E\) represents the base material comprehensive elastoplastic modulus, and \(\frac{1}{E} = \frac{{(1 - \nu_{1}^{2} )}}{{E_{1} }} + \frac{{(1 - \nu_{2}^{2} )}}{{E_{2} }}\) holds true,\(\nu_{1,2}\) denotes the Poisson’s ratio;\(K\) describes the correlation coefficient between the hardness value and the yield strength \(\sigma_{y}\).

By combining Eqs. (4) and (5), it is described as:

The critical contact area \(a_{l}\) of the cross-section of a single MCP is expressed as:

According to the classical Hertz contact theory, the elastic contact load \(P_{E} (\omega )\) of a single MCP subjected to alternating excitation loads leading to elastoplastic deformation is expressed as28:

By combining Eqs. (2) and (4) and substituting Eq. (8), we obtain:

Single MCP load-bearing contact model

The aim is to establish the correlation between each MCP and its maximum peak value, in order to achieve an integrable solution for the total elastic load of all MCP across the entire contact area of the textured interface. Set the maximum MCP contact base diameter of the textured interface as \(H_{\max }\), and let \(H_{\max t}\) represent the maximum truncated diameter of the MCP profile. By considering the cosine expression of the height profile of the MCP, the formula for the maximum value of the MCP profile is obtained as follows:

Considering the maximum micro-unit peak contact base diameter \(H_{\max }\) of the textured interface and combining it with the calculation formula for the contact area of the micro-unit peaks, the actual bearing contact area of the textured interface is expressed as:

where,\(a_{H}\) represents the contact area of the textured interface with the maximum MCP contact base diameter \(H_{\max }\), the contact area of the remaining micro-unit peaks is indirectly calculated using \(H_{\max t}\).

By introducing the contact equivalent proportionality factor \(\varepsilon_{b} = \frac{{h_{t} }}{h}\), the expression (3) is transformed into:

From the above equation, it is concluded that the contact area of micro-unit peaks with different morphological scales can necessarily be obtained by the corresponding equivalent proportionality factor \(\varepsilon_{b}\), that is,

\(a = \frac{{h^{2} }}{\pi }\left\{ {1 - \cos \left( {\frac{{\pi h_{t} }}{2h}} \right)} \right\} = \frac{{h^{2} }}{\pi }\left\{ {1 - \cos \left( {\frac{{\pi \varepsilon_{b} }}{2}} \right)} \right\} = \frac{{H_{\max }^{2} }}{\pi }\left\{ {1 - \cos \left( {\frac{{\pi H_{\max t}^{2} }}{{2H_{\max } }}} \right)} \right\}\) holds true.

Thus, the base diameter \(h\) of each micro-unit peak is expressed as29:

By substituting the above equation into Eq. (9), the elastic contact load \(P_{E} (\omega )\) caused by the elastoplastic deformation of a single micro-unit peak under alternating excitation loads can be solved30:

Let \(\chi = \left\{ {1 - \cos \left( {\frac{{\pi \varepsilon_{b} }}{2}} \right)} \right\}^{{{D \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {D 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}}}\), while \(\chi\) represents the correlation function with the contact equivalent proportionality factor \(\varepsilon_{b}\). By simplifying the above Eq. (14), we obtain:

Micro-unit peak morphology distribution density function correction model

In the alternating meshing region of the warship PRTS, the teeth surface contact area with micro-unit peak morphology distribution cannot accurately reflect the actual IMT contact area. Based on the fractal model, the contact distribution characteristics of the MCP are described in the form of a micro-unit density function, which is expressed as:

where,\(\alpha_{{H_{\max } }}\) represents the contact area of the maximum micro-unit peak base diameter \(H_{\max }\),\(J(\alpha )\) is the distribution density function of the non-curved surface contact area.

Considering the curvature variation characteristics of non-flat interfaces, their contact area will also change accordingly, as shown in Fig. 4. Unlike the distribution density model of non-curved surface contact areas, the curved surface contact area is not less than \(\alpha\), and the number of micro-unit peaks decreases, meaning the total number does not exceed \(\alpha^{{ - {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$D$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {D 2}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}}}\). By introducing the curved micro-unit peak contact coefficient \(\varepsilon_{J}\) and deriving the spherical interface contact area distribution formula \(J(\alpha )\), the initial area distribution density function \(J^{\prime}(\alpha )\) is further corrected31,32.

where, curved surface microelementary peaked body contact coefficient \(\varepsilon_{J} = \left( {\frac{{S_{L} }}{{\sum {S_{n} } }}} \right)^{{K_{0} }}\),\(S_{L}\) represents the theoretical non-flat interface contact area, and \(S_{L} = B_{1} \left( {\frac{\Omega (F,E)C}{{K_{0} }}} \right)^{{B_{2} }}\) holds,\(B_{1}\) and \(B_{2}\) denote parameters related to the geometric characteristics of the non-flat interface morphology.\(F\) represents the contact width of the micro-element convex peak body.\(\Omega (F,E)\) represents a function related to the interface material (parameter \(E\)) and its contact form (parameter \(F\)), and \(C\) represents the normal contact load between the interfaces.\(\sum {S_{n} }\) represents the total contact area of any number of non-flat interfaces, and its expression is \(\sum {S_{n} } = S_{1} \pm S_{2} \pm \cdots \pm S_{n}\)(where the plus sign indicates external meshing, and the minus sign indicates internal meshing).\(K_{0}\) represents the comprehensive curvature parameter, and \(K_{0} = X_{1} + X_{2} + X_{3} + X_{4}\) exists.\(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) denote the principal curvatures of the normal cross-section of the upper non-flat interface, while \(X_{3}\) and \(X_{4}\) denote the principal curvatures of the normal cross-section of the lower non-flat interface.

Analysis of lubrication load-bearing characteristics considering textured interface contact model

Analysis of contact teeth surface stiffness and damping

Based on the transient process of gear meshing in the warship PRTS, and considering the textured interface contact model, the multi-scale parameter correlation of the TEHL textured interface is determined to analyze the time-varying meshing load-bearing characteristics (i.e., meshing stiffness and viscous damping characteristics)33. Figure 5 shows the geometric parameter analysis model of an involute gear with textured interface meshing contact, aiming to determine the characteristic parameters of the textured interface and the analytical parameters of lubrication properties at key meshing positions during the alternating contact process of the teeth surface. This model is used to solve the contact stiffness and viscous damping of the meshing interface. The time-varying key parameters during the meshing process are the meshing dynamic force, sliding velocity, and radius of curvature. Point \(O\) represents any contact position on the teeth profile of the meshing surface. \(V_{1}\) and \(V_{2}\) are the velocities of the pinion and gear at the position of point \(O\), respectively. Points \(O_{1}\) and \(O_{2}\) are the geometric centers of the pinion and gear, respectively. Line \(K_{1} K_{2}\) represents the common tangent of the base circles.\(r_{b1}\) and \(r_{b2}\) are the base circle radii of the two gears, respectively.\(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the meshing rotation angles of the two gears, respectively. The radius of curvature at the contact point \(O\) is expressed as:

Here, the equivalent radius of curvature at the meshing point is \(\rho_{e} = {{\rho_{1} \rho_{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\rho_{1} \rho_{2} } {(\rho_{1} + \rho_{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {(\rho_{1} + \rho_{2} }})\). Given the rotational speeds of the two gear shafts as \(n_{1}\) and \(n_{2}\), the tangential velocity at the meshing point on the teeth surface is expressed as:

Under alternating excitation loads, the meshing teeth surfaces are in a time-varying contact state, and the load borne during the transmission process originates from multiple meshing teeth. This leads to the exploration of the load distribution law among the meshing teeth surfaces34. The variation curve of the load distribution coefficient between the meshing teeth surfaces of the warship PRTS is shown in Fig. 6. The load distribution coefficient at the initial point of the actual contact profile of the meshing teeth surface is the smallest, with two teeth participating in the meshing state. In the Double Teeth Contact (DTC) region, the load between the teeth surfaces increases and exhibits a linear distribution growth. The double-teeth meshing ends when a single tooth enters the initial meshing state. From the lowest point to the highest point of single-tooth meshing, only one pair of teeth bears the steady-state load, and the meshing node is located in the middle of the Single Tooth Contact (STC) region.

The end of the single-tooth meshing state marks the beginning of the meshing-in of a new tooth pair (i.e., the double-teeth meshing state), and the meshing process terminates at the tooth tip. During this transient process, the load between the meshing teeth surfaces decreases and exhibits a linear trend. Based on the proposed TEHL analytical model, the contact stiffness and damping of the meshing tooth surface interface are solved. Using the gear parameters provided in Table 1 as research data, the influence of slip velocity and alternating load factors on the contact stiffness and damping of the meshing interface is explored. The variations in tooth surface contact stiffness and damping under different meshing interface slip velocities are analytically determined, as shown in Fig. 7.

As shown in Fig. 7, as the slip velocity at the meshing interface increases, the contact stiffness and damping of the tooth surface exhibit a decreasing trend. When the meshing region transitions from the Single Tooth Contact (STC) domain to the Double Tooth Contact (DTC) domain, the contact stiffness and damping of the tooth surface undergo a sudden step-like change. Specifically, the contact damping initially increases and then decreases, while in the meshing-in STC region, the contact stiffness shows a decreasing rather than an increasing trend. When the DTC transitions back to the STC, the contact stiffness and damping of the tooth surface sharply decrease, reaching a minimum point, after which they gradually increase and then decrease again, forming a local minimum within a specific range.

This phenomenon can be explained as follows: when the relative slip velocity between the transient interfaces of the meshing tooth surfaces approaches zero, the hydrodynamic fluid film becomes extremely thin, and the contact area of the micro-peaks increases. As a result, the influence of the micro-peaks dominates the contact stiffness and damping. Generally, the direct contact stiffness of the tooth surface is much smaller than the stiffness of the hydrodynamic fluid film. Moreover, a decrease in the slip velocity of the tooth surface leads to an increase in the amplitude of time-varying fluctuations in the contact stiffness and damping of the meshing interface.

The variations in tooth surface contact stiffness and damping under different meshing interface loads are analytically determined, as shown in Fig. 8. From the figure, it can be observed that as the meshing interface load increases, the tooth surface contact stiffness and damping also increase. Similar to the influence of slip velocity on tooth surface contact stiffness and damping, the time-varying trends of both stiffness and damping are nearly identical under varying loads. Compared to the effects of slip velocity, the influence of different meshing interface loads on tooth surface contact stiffness and damping is more consistent, with similar amplitude fluctuations. This indicates that the distribution characteristics of the hydrodynamic fluid film and its thickness dominate the values of tooth surface contact stiffness and damping. Furthermore, within the meshing domain, the distribution of hydrodynamic film pressure and film thickness has a more significant impact on slip velocity.

Analytical solution for tooth surface meshing stiffness and interface contact damping

Based on the aforementioned numerical analysis of tooth surface contact stiffness and damping, combined with the initial contact tooth surface meshing stiffness and damping, the tooth surface meshing stiffness and interface contact damping under TEHL conditions are further solved. The influence of slip velocity and alternating load on the variation trends of tooth surface meshing stiffness and interface contact damping is analyzed. The time-varying patterns are illustrated in Fig. 9.

As shown in the figure, when the slip velocity increases, the interface meshing stiffness and damping decrease. The variation amplitude of the interface meshing stiffness is less pronounced compared to the significant fluctuations in damping. Additionally, abnormal fluctuations in amplitude are observed during the transition between STC and DTC, or at the initial meshing-in and meshing-out stages. The transition from DTC to STC intensifies the time-varying damping, and during the alternating stages of STC and DTC, the slip velocity decreases, accompanied by a reduction in damping and large amplitude fluctuations.

Figure 10 illustrates the time-varying relationship between the interface meshing stiffness and damping under different tooth surface loads. As shown in the figure, as the load on the tooth surface increases, the time-varying meshing stiffness and damping of the interface also increase. Compared to the results of slip velocity analysis, the variation amplitude of meshing stiffness and damping exhibits larger and more pronounced fluctuations. Particularly in Fig. 10a, when the meshing region transitions from the DTC to the STC, a sudden change in meshing stiffness occurs.

This change becomes more significant as the tooth surface load decreases, which is attributed to the reduction in meshing stiffness under TEHL conditions. Additionally, meshing damping is significantly influenced by the tooth surface load. During the alternating transition between STC and DTC (or at the initial meshing-in and meshing-out stages), the amplitude of damping shows abnormal fluctuations, as depicted in Fig. 10b. When transitioning from DTC to STC, the interface meshing damping undergoes a sudden change, and the amplitude variation trends under different teeth surface loads are almost similar. Overall, the time-varying patterns of interface meshing damping under different tooth surface loads are generally consistent, with only slight differences observed in the time-varying trends within the DTC region.

Under TEHL conditions, modifications such as profile fitting optimization or edge trimming are often performed along the meshing length direction of the tooth surface interface to reduce and suppress stress concentration. Additionally, considering the finite length of the actual contact line on the meshing tooth surface, these meshing characteristics will influence the analysis of the contact interface ASLBC.

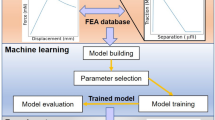

Simulation analysis of the influence of texture parameters on the load-bearing performance of MTMI

Considering the characterization parameters of surface textures, the equations for contact load and contact area between MTMI are derived. The influence of material parameters, friction coefficients, and peak amplitudes of MCP bodies on the normal stiffness, viscous damping, and ASLBC of the meshing interface is analyzed. The intrinsic relationship between the microscopic morphology of textures and the load-bearing characteristics of meshing tooth surfaces is established. Based on the derived mathematical model of textured interface contact and simulated using MATLAB, the time-varying trends of ASLBC under different texture parameters are revealed. This aims to determine the optimal texture parameters, thereby guiding the design of micro-textured patterns on meshing teeth surfaces to enhance the operational stability and service life of warship PRTS under alternating and complex working conditions.

Simulation analysis of the influence of fractal dimension on meshing load-bearing performance

Considering different fractal dimensions \(D\) and using MATLAB simulations, the relationship between the textured tooth surface load and the actual interface contact area within the meshing region is analyzed. As shown in Fig. 11a, under the same meshing load, as the contact interface area increases, the unit micro-area decreases, and the load-bearing capacity of the tooth surface improves. The results indicate a proportional linear relationship between the textured tooth surface load and the actual interface contact area. The analysis also reveals that as the fractal dimension \(D\) increases, the slope of the variation curve gradually rises and reaches its maximum at fractal dimension \(D = 1.50\), thereby demonstrating that the textured tooth surface exhibits optimal ASLBC at this fractal dimension. From Fig. 11b, it can be observed that at fractal dimension \(D > 1.50\), if the slope of the variation curve shows a declining trend, it indicates the existence of an optimal constant value for this fractal dimension. Specifically, when the fractal dimension of the interface texture is \(D = 1.50\), the meshing tooth surface achieves the best ASLBC.

Correlation law between textured surface loads and actual interfacial contact area in meshing domains with different fractals (a), (b) Actual interface contact area affects load characteristics variation of textured surface (c), (d) Time-varying trend of elastomer share of contact area in meshing domains.

From Figs. 11c and d, it can be concluded that as the contact area of the textured interface increases, the proportion of elastic micro-elements in the contact area of the meshing region gradually rises. However, as the fractal dimension increases, the proportion of elastic elements in the contact area shows a declining trend. This decline is particularly significant at fractal dimension \(D < 1.50\), further illustrating that an increase in fractal dimension leads to a sharp rise in the number of plastic deformations caused by the peaks of the micro-elements.

Simulation analysis of the influence of interface friction coefficient on meshing load-bearing performance

The time-varying influence of the interface friction coefficient on the load-bearing characteristics of the contact area is not significant, as shown in Fig. 12. Based on traditional contact mechanics theory, the tangential contact load of the meshing tooth surface is significantly constrained by the interface friction coefficient, while the normal contact load is less affected by it. Therefore, optimizing the interface friction coefficient does not significantly improve the meshing load-bearing performance.

Simulation analysis of the influence of micro-texture scale parameters on meshing load-bearing performance

Based on the numerical simulation of the tooth surface meshing model, the TEHL performance of the textured interface under sliding contact in warship PRTS gears is analyzed for different micro-texture scale parameters. The characteristics of the medium layer film, friction coefficient, and medium film pressure at the meshing interface are examined in relation to the geometric parameters of the texture morphology, such as pit radius, depth, peak height of micro-convex bodies, and the width-to-diameter ratio of concave-convex micro-elements. The time-varying trends of these parameters are analyzed to determine the mechanism by which micro-texture scale parameters influence the lubrication properties and load-bearing performance of the MTMI. This analysis aims to guide the micro-texture topology design and functional optimization of the contact interface in warship PRTS meshing teeth surfaces.

Simulation analysis of the influence of pit micro-element radius on load-bearing performance

Figure 13a illustrates the time-varying relationship of the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the interface under different pit micro-element radii during the sliding contact transient of textured meshing teeth surfaces. As shown in the figure, the time-varying curve of the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the MTMI exhibits a gradually decreasing trend. The rate of change slows down at the initial stage of TEHL meshing and then accelerates until the end of the meshing process. Comparing the time-varying curves of the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio under different pit micro-element radii, it is evident that when the depth of the pit micro-elements and the height of the convex peak micro-elements are held constant, an increase in the Pit Micro-Element Radius (PMER) leads to a gradual increase in the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the MTMI. This is particularly evident under TEHL conditions, where an increase in the PMER promotes the accumulation of hydrodynamic fluid within the textured micro-elements, resulting in an increase in the medium layer film thickness. However, the rate of increase diminishes significantly as the PMER further increases.

Bearing characteristics of pit microelement radius (a) Time-varying between interface minimum dielectric layer film thickness ratio with different pits microelement radii (b) Time-varying trend of dielectric layer film pressure and pressure of microelement peaks at pits microelement radii (c) Cloud view of interfacial dielectric layer film pressure with pits microelement radii.

Figure 13b depict the time-varying relationships of the hydrodynamic medium layer film pressure and the MCP pressure within the meshing time domain. The results indicate that the hydrodynamic medium layer film pressure initially increases gradually and then decreases sharply during the meshing process. In contrast, the MCP pressure increases rapidly within the steady-state meshing region. This behavior is attributed to the gradual reduction of the meshing gap as the steady-state meshing transient progresses, with the medium layer film pressure playing a dominant role. As the medium layer film pressure increases, the MCP pressure initially emerges and then rises sharply, while the medium layer film pressure gradually diminishes. Comparing the two pressures, it is observed that as the PMER increases, the initial emergence of both the medium layer film pressure and the MCP pressure is progressively delayed. This can be explained by the fact that larger pit micro-elements store more lubricant, which provides sufficient medium layer film pressure to meet the normal load requirements of the TEHL interface during the meshing transient. Further increasing the PMER does not significantly improve the lubrication and friction performance but may instead inhibit the torque transmission capacity of the meshing pair. Specifically, when the PMER exceeds a certain threshold, the stored lubricant within the pit micro-elements increases the medium layer film pressure, leading to a gradual reduction in the peak pressure of the micro-convex elements.

In Figs. 13c, an appropriate PMER can increase the hydrodynamic medium layer film thickness to some extent and improve lubrication and friction performance. However, an excessively large PMER results in the stored lubricant within the texture still bearing a portion of the normal load at the end of the meshing transient, thereby reducing the frictional torque at the interface and affecting the torque transmission capacity.

In summary, the results indicate that an appropriate pit micro-element configuration can effectively reduce the interface friction coefficient under TEHL conditions during the meshing transient, thereby minimizing sliding friction and contact losses. Based on the scale factor of the PMER, if the PMER is too small, the moment at which the medium layer film pressure decreases occurs earlier, weakening the normal load-bearing capacity provided by the medium layer film and exacerbating interface friction and wear. Conversely, if the PMER is too large, it increases the shear friction coefficient of the medium layer film during the initial meshing stage, leading to higher frictional energy losses. Additionally, at the end of the meshing transient, the medium layer film provides a certain load-bearing capacity, which reduces the peak contact pressure of the MCP and negatively impacts torque transmission.

Simulation analysis of the influence of pit micro-element depth on load-bearing performance

Assuming the PMER and the height of the MCP texture are constant, the time-varying relationships of the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio, medium layer film pressure, and MCP texture pressure during the alternating contact transient of meshing teeth surfaces under different pit micro-element depths are illustrated in Fig. 14. As shown in Fig. 14a, when the pit micro-element depth increases, the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the interface exhibits a gradually decreasing trend, which is opposite to the effect of the PMER. An increase in the PMER prolongs the contact transient during which the micro-convex peak texture bears pressure. This trend is similar to the influence of the PMER on the medium layer film thickness ratio. Specifically, a larger PMER allows for the accumulation of more hydrodynamic fluid, enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the medium layer film. Consequently, this delays the time domain during which the MCP texture bears the load.

Bearing characteristics of pit microelement depth (a) Time-varying between interface minimum dielectric layer film thickness ratio with pits microelement depth (b) Time-varying trend of dielectric layer film pressure and pressure of microelement peaks at pits microelement depth (c) Cloud view of interfacial dielectric layer film pressure with pits microelement depth.

As shown in Figs. 14b and c, when the meshing tooth surface operates under TEHL conditions and the PMER is relatively small, the medium layer film pressure is not significantly affected by changes in the pit micro-element depth. This can be attributed to the fact that, under TEHL conditions, the medium layer film thickness at the meshing interface provides sufficient load-bearing capacity, thereby mitigating the influence of the PMER on the minimum medium layer film pressure. Consequently, the effect of the pit micro-element depth becomes more pronounced. Additionally, as the PMER increases, the influence of the pit micro-element depth on the pressure of the MCP texture gradually diminishes.

Simulation analysis of the influence of micro-convex peaks texture height on load-bearing performance

Assuming the PMER and depth are constant, the time-varying relationships among the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio, medium layer film pressure, and MCP texture pressure during the alternating contact transient of meshing tooth surfaces under different MCP texture heights are illustrated in Fig. 15. As shown in Fig. 15a, as the height of the MCP texture increases, the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the interface exhibits a gradually decreasing trend. This is attributed to the fact that the MCP texture increases the surface roughness of the tooth, leading to a reduction in the minimum medium layer film thickness ratio. Excessively high MCP textures can cause the tooth surface to prematurely enter TEHL contact at higher sliding speeds during the meshing transient, thereby exacerbating friction and wear. When the PMER is very small, excessively high MCP textures can also result in an excessively low minimum medium layer film thickness ratio at the interface during the meshing transient, making it difficult to meet the required medium layer film load-bearing capacity under TEHL conditions.

Bearing characteristics of pits with microelement convex peak height (a) Time-varying relationship between interface minimum dielectric layer film thickness ratio (b) Time-varying trend of dielectric layer film pressure and pressure of microelement peaks (c) Cloud view of interfacial dielectric layer film pressure.

As shown in Figs. 15b and c, when the height of the MCP texture increases, the pressure of the MCP emerges prematurely, thereby activating the anchoring effect of the MCP to enhance frictional contact and increase the friction coefficient at the MTMI. This is intended to achieve greater torque transmission capacity. When the PMER increases, the pressure of the MCP is delayed, indicating that optimizing the matching values of the MCP texture height and radius through coordinated control can improve the torque transmission capacity of the meshing pair. Additionally, appropriately increasing the height of the MCP texture can mitigate the influence of the PMER scale on the peak pressure of the micro-convex texture. As the height of the MCP texture continues to increase, the rate of decline in the maximum peak pressure difference gradually stabilizes.

Discussion of the results

This study is the first to introduce micro element texture into the homogeneous IEL regulation of the MTMI of warship PRTS to control meshing ASLBC. The proposed novel lubrication and load-bearing evaluation method is original and is expected to break through the limitations of heavy-load gear fatigue and scuffing failure in the warship PRTS, making it immune to the exacerbation of friction and wear caused by changes in lubrication characteristics at the meshing interface. Guided by the actual needs and problems of the warship PRTS gears, this research proposes a new method for evaluating ASLBC with IMT based on the regulation of homogeneous IEL characteristics on the meshing tooth surface. This method has the potential to form a systematic and independent intellectual property system, providing a theoretical foundation and analytical tools for the study of structural design, processing methods, transmission efficiency, lubrication characteristics, fatigue life, and reliability of existing warship PRTS gears.

Conclusion

This topic investigates the load-bearing characteristics of textured interfaces under TEHL conditions. A generalized contact load-bearing model for MTMI under TEHL is proposed, incorporating an equivalent contact scale factor. This factor represents the contact area of all micro-convex peaks on the meshing tooth surface using the peak with the highest micro-convex body, and modifies the morphological distribution density function to ensure integrability for micro-convex bodies. A distribution density function for the micro element texture in the contact area of the meshing interface is established, enabling more accurate analysis of the actual contact area of the MTMI. A mathematical model for the load-bearing performance of textured meshing interfaces under steady-state TEHL conditions is derived, revealing the relationship between load and the contact stiffness of textured teeth surfaces as well as the damping of the meshing interface. This provides a theoretical foundation and data reference for optimizing the IEL effect of MTMI and enhancing the ASLBC of the contact IMT. Based on the research findings, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

The meshing interface load and sliding velocity govern the tooth surface contact stiffness and interface contact damping with similar time-varying patterns. The distribution characteristics of the hydrodynamic fluid medium layer and its film thickness dominate the values of tooth surface contact stiffness and interface contact damping. Meanwhile, the distribution of hydrodynamic fluid film pressure and the layer thickness have a more pronounced influence on the sliding velocity within the meshing region.

-

(2)

An increase in the fractal dimension leads to a sharp rise in the number of plastic deformations caused by the peaks of the micro element texture. As the fractal dimension increases, the proportion of elastic elements in the contact area shows a declining trend.

-

(3)

Under TEHL conditions with a small Pit Micro-Element Radius (PMER), the medium layer film pressure is minimally affected by changes in the pit micro-element depth. The medium layer film thickness at the MTMI provides sufficient load-bearing capacity, thereby reducing the influence of the PMER on the minimum medium layer film pressure. Consequently, the effect of the pit micro-element depth becomes more pronounced. Additionally, as the PMER increases, the influence of the pit micro-element depth on the pressure of the micro-convex peak texture gradually diminishes.

The research findings will help address the limitations of previous studies on the time-varying friction TEHL characteristics of warship PRTS, which did not fully consider the micro-topography of the rolling/sliding transition points/lines in the contact interface. The study explores how to regulate the multi-scale characterization parameters of IMT to achieve optimal interface lubrication characteristics and load-bearing performance. This breakthrough overcomes the poor effectiveness of traditional lubrication under harsh operating conditions. Gear surfaces with MTMI maintain a low-friction state at the contact interface for an extended period. This provides the possibility for enriched lubrication and anti-scuffing load-bearing capacity of meshing gear surfaces under high-speed and heavy-load extreme operating conditions in warship PRTS35,36,37 (Ref. 35: This study investigates the effects of micro-textured gear surfaces on enhancing anti-scuffing load-bearing capacity under thermoelastohydrodynamic lubrication (TEHL) conditions. A combined numerical and experimental approach is employed to evaluate lubrication performance under high-load operating regimes. The results demonstrate that optimized micro-textures significantly improve lubricant film stability while reducing friction and wear. Ref. 36: Presents rigorous analytical and experimental investigations into the influence of micro-textures on lubrication performance and load distribution. Demonstrates that tailored surface morphology can markedly enhance hydrodynamic pressure generation and wear resistance. Ref. 37: A groundbreaking surface engineering technique is reported, combining microbial jet machining with mask patterning. The method achieves highly precise and customizable micro-textures for enhanced tribological functionality.). Investigating the evolution mechanism of IEL characteristics under the influence of multi-scale characterization parameters, and coupling the stress field, film thickness field, and temperature field with macroscopic parameters such as configuration and load distribution, as well as micro-scale parameters such as micro-asperity peaks and texture direction, will provide theoretical and technical support for further improving the ASLBC of meshing gear surfaces in warship PRTS. This is a research work of practical significance.

Data availability

All relevant data are provided within the manuscript.

References

Özdemir, M. N., Kılıç, V. & Ünlüsoy, Y. S. A new contact & slip model for tracked vehicle transient dynamics on hard ground. J. Terrramech. 73, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jterra.2017.07.001 (2017).

Liu, W. L., Ni, H. J., Wang, P. & Chen, H. L. Investigation on the tribological performance of micro-dimples textured surface combined with longitudinal or transverse vibration under hydrodynamic lubrication. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 174, 105474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.105474 (2020).

Guilbault, R. & Lalonde, S. A stochastic prediction of roughness evolution in dynamic contact modelling applied to gear mild wear and contact fatigue. Tribol. Int. 140, 105854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2019.105854 (2019).

Croccolo, D., De Agostinis, M., Olmi, G. & Vincenzi, N. A practical approach to gear design and lubrication: A review. Lubricants 8(9), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants8090084 (2020).

Tu, Zh. R., Meng, X. K., Ma, Y. & Peng, X. D. Shape optimization of hydrodynamic textured surfaces for enhancing load-carrying capacity based on level set method. Tribol. Int. 162, 107136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2021.107136 (2021).

Marques, P. M. T., Marafona, J. D. M., Martins, R. C. & Seabra, J. H. O. A continuous analytical solution for the load sharing and friction torque of involute spur and helical gears considering a non-uniform line stiffness and line load. Mech. Mach. Theory 161, 104320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2021.104320 (2021).

Chen, W., Lei, Y., Fu, Y. & Hou, L. A study of effects of tooth surface wear on time-varying mesh stiffness of external spur gear considering wear evolution process. Mech. Mach. Theory 155, 104055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2020.104055 (2021).

Zhao, J., Sheng, W., Li, Z., Zhang, H. & Zhu, R. Effect of lubricant selection on the wear characteristics of spur gear under oil-air mixed lubrication. Tribol. Int. 167, 107382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2021.107382 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Uncertainty propagation of correlated lubricant properties in gear tribodynamic system. Tribol. Int. 179, 107812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.107812 (2023).

Cheng, G. et al. Study on the dynamic characteristics of gears considering surface topography in a mixed Lubrication State. Lubricants 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants12010007 (2024).

Sánchez, M. B., Pleguezuelos, M. & Pedrero, J. Strength model for bending and pitting calculations of internal spur gears. Mech. Mach. Theory 133, 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2018.12.016 (2019).

Černe, B., Petkovšek, M., Duhovnik, J. & Tavčar, J. Thermo-mechanical modeling of polymer spur gears with experimental validation using high-speed infrared thermography. Mech. Mach. Theory 146, 103734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.103734 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Understanding the mechanism of load-carrying capacity between parallel rough surfaces through a deterministic mixed lubrication model. Lubricants 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants10010012 (2022).

Chang, X. et al. Study on hydrodynamic lubrication and friction reduction performance of spur gear with groove texture. Tribol. Int. 177, 107978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.107978 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Research on the time-varying mesh stiffness method and dynamic analysis of cracked spur gear system considering the crack position. J. Sound Vib. 548, 117505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2022.117505 (2023).

Cao, P., Li, Q., Feng, K. & Qin, Y. Dynamic modeling of spur gear transmission system with evolutive coupling fault of fatigue crack and wear. Eng. Fail. Anal. 156, 107820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107820 (2024).

Zhang, N. et al. Deep-sea soft soil and deep-sea mining vehicle interaction: From soil properties to locomotion performance. Appl. Ocean Res. 154, 104372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2024.104372 (2025).

Ammosov, L., Mönkkönen, K. & Suvanto, M. Precise fabrication of microtextured stainless steel surfaces using metal injection moulding. Precis. Eng. 62, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2019.11.012 (2020).

Zhao, J., Hou, L., Li, Z., Zhang, H. & Zhu, R. Prediction of tribological and dynamical behaviors of spur gear pair considering tooth root crack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 135, 106145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106145 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. A deterministic model of surface profile degradation for evaluating time-varying mesh stiffness and dynamic responses of spur gear considering tooth surface wear evolution. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 225, 112313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.112313 (2025).

Codrignani, A., Savio, D., Pastewka, L., Frohnapfel, B. & Ostayen, R. V. Optimization of surface textures in hydrodynamic lubrication through the adjoint method. Tribol. Int. 148, 106352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2020.106352 (2020).

Wang, X. G., Huang, H., Song, J. Y., Wang, Y. M. & Ruan, J. F. Numerical analysis of friction reduction and ATSLB capacity of lubricated MTMI with textured micro-elements. Lubricants 11(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants11020078 (2023).

Meng, F. M., Yu, H. Y., Gui, C. & Chen, L. Experimental study of compound texture effect on acoustic performance for lubricated textured surfaces. Tribol. Int. 133, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2018.12.036 (2019).

Rajput, H., Atulkar, A. & Porwal, R. Optimization of the surface texture on piston ring in four-stroke IC engine. Mater. Today Proc. 44(1), 428–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.752 (2021).

Galda, L., Sep, J., Olszewski, A. & Zochowski, T. Experimental investigation into surface texture effect on journal bearings performance. Tribol. Int. 136, 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2019.03.073 (2019).

Liu, H. L., Liu, H. J., Zhu, C. C. & Parker, R. G. Effects of lubrication on gear performance: A review. Mech. Mach. Theory 145, 103701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.103701 (2020).

Wang, X. G., An, S. Y., Wang, Y. M., Ruan, J. F. & Ji, S. E. TEM fitting considering TEPs of contact interface of meshing gear. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 35(10), 4443–4457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-021-0915-3 (2021).

Petare, A. C., Mishra, A., Palani, A. & Jain, N. K. Study of laser texturing assisted abrasive flow finishing for enhancing surface quality and microgeometry of spur gears. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 101, 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2944-3 (2019).

Xing, Y. Q. et al. Numerical analyses of rectangular micro-textures in hydrodynamic lubrication regime for sliding contacts. Meccanica 56, 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11012-020-01296-x (2021).

Rosenkranz, A., Grützmacher, P. G., Gachot, C. & Costa, H. L. Surface texturing in machine elements-A critical discussion for rolling and sliding contacts. Adv. Eng. Mater. 21, 1900194. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.201900194 (2019).

Wos, S., Koszela, W. & Pawlus, P. Comparing tribological effects of various chevron-based surface textures under lubricated unidirectional sliding. Tribol. Int. 146, 106205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2020.106205 (2020).

Sivayogan, G., Dolatabadi, N., Johns-Rahnejat, P., Rahmani, R. & Rahnejat, H. Non-newtonian thermo-elastohydrodynamics and sub-surface stress field of high-performance racing spur gears. Lubricants 10(7), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants10070146 (2022).

Gupta, N., Tandon, N., Pandey, P. K., Vidyasagar, K. ECh. & Kalyanasundaram, D. Tribodynamic studies of textured gearsets lubricated with fresh and MoS2 blended greases. Tribol. Int. 165, 107247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2021.107247 (2022).

Kaneta, M., Matsuda, K. & Nishikawa, H. The causes of asymmetric deformation of surface roughness asperities in elastohydrodynamic lubrication contacts. J. Tribol. 144(6), 061601. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4052255 (2022).

Ruan, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y. & Li, C. Study on anti-scuffing load-bearing thermoelastic lubricating properties of meshing gears with contact interface micro-texture morphology. J. Tribol. 144(10), 101202. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4054400 (2022).

Wang, X., Ruan, J., Wang, Y. & Zou, W. Analytical and Experimental Research of Lubrication Load-Bearing Characteristics of Microtextured Meshing Interface. Materials 18(4), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18040845 (2025).

Ruan, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y. & Zou, W. Mask-guided microbial jet machining: An approach for fabricating functionalized textured interfaces. J. Tribol. 24, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4069248 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Huaqiao University (HQU) and Heilongjiang Institute of Technology (HLJIT) for their support. Authors sincerely appreciate all participants for their contributions.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation Sponsored Project (Project Approval Number: 52475257), the Nation-al Key Research and Development Program Project (Grant No. 2023YFB3406301), the Fund Project for Technological Field of National Defense Science and Technology Plan 173 (2024-JCJQ-JJ-2020) and (2024-JCJQ-JJ-2043), the Marine Propulsion Research and Development (MPRD) Program (Grant No. MG20220203).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X. G. Wang. and Y. M. Wang; methodology, W. Q. Zou; software, J. F. Ruan; validation, X. G. Wang, Y. M. Wang and J. F. Ruan; formal analysis, W. Q. Zou; investigation, J. F. Ruan; resources, Y. M. Wang; data curation, W. Q. Zou; writing—original draft preparation, W. Q. Zou and X. G. Wang; writing—review and editing, X. G. Wang, Y. M. Wang and J. F. Ruan; visualization, J. F. Ruan; supervision, J. F. Ruan and W. Q. Zou; project administration, Y. M. Wang and W. Q. Zou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication. We would like to declare on behalf of our co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All the authors listed have approved of the manuscript that is enclosed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruan, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y. et al. Study on TEHL contact load bearing characteristics of micro-textured meshing interface for warship PRTS. Sci Rep 15, 35539 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19612-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19612-4