Abstract

Perovskite-type metal oxides have sparked intense attention owing to their diverse structural, electrical, and catalytic characteristics, making them interesting materials for environmental and biological applications. In this study, Curcuma longa (turmeric) rhizome extract was used as a natural reducing and stabilizing agent to prepare bismuth nickelate nanoparticles (BiNiO3 NPs) using a green manufacturing method. Significant visible light absorption was shown by UV–visible absorption spectroscopy (UV–Vis), which confirmed its photocatalytic application with a predicted band gap of 2.90 eV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed the morphological and structural properties of the resultant nanoparticles and revealed a highly crystalline multiphase perovskite phase consisting of tetragonal (ICDD #96-900-8427) and cubic (ICDD #96-901-3981). The presence of phytochemicals generated from turmeric on the surface of the nanoparticles was confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), by revealing a broadband between 550 and 650 cm−1. The existence of quasi-spherical, rod-like, and pear-shaped nanoparticles with an average particle size of around 15–20 nm was shown by investigations using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). The elemental composition was authenticated by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) by affirming the characteristic peak of O 1s at 529.79 eV. Zone of inhibition investigations confirmed that the BiNiO3 NPs possess strong antibacterial efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus (21.33 mm) and Escherichia coli (22.66 mm). Furthermore, Rhodamine-B (Rh-B) dye was effectively degraded by photocatalytic studies when exposed to visible light, with 93.82% degradation occurring in 100 min. The reduced band gap, surface phytochemical capabilities, and efficient charge separation inside the nanoparticles are the causes of the ensuing enhanced activity. This study demonstrates the potential of turmeric-assisted green-synthesised BiNiO3 NPs as a multipurpose substance for antibacterial and wastewater purification applications, offering a sustainable substitute for conventional chemical synthesis methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing global emphasis on sustainable technologies has spurred the development of multipurpose, ecologically friendly nanomaterials. Conventional chemical methods for creating nanoparticles typically include hazardous chemicals1, toxic solvents2, and large energy expenditures, all of which present serious problems for biological compatibility and environmental safety3,4. Here, green synthesis techniques—particularly those that employ plant-derived phytochemicals—offer a scalable, affordable, and environmentally friendly way to produce functional nanomaterials5,6.

Bismuth perovskites are one of the functional metal oxides that have garnered the most interest due to their wide range of physicochemical characteristics and structural flexibility7. The optical and catalytic characteristics of BiNiO3, a perovskite oxide with the general formula ABO3, where Bi3+ is at the A-site and Ni2+/Ni3+ is at the B-site, are promising8,9. It is a great option for photocatalytic use due to its effective absorption of visible light energy and very narrow band gap (around 1.8–2.0 eV)10. Furthermore, the efficient transfer of charges and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are essential for antibacterial and photocatalytic processes, are made possible by the redox activity of both Bi and Ni ions11,12. Because of these inherent qualities, BiNiO3 is a viable option to address the present problems in the biological and environmental remediation domains.

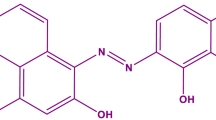

Using plant extracts to synthesize BiNiO3 NPs has emerged as a needed approach to further enhance their biological interaction and sustainability13,14. The enormous variety of secondary metabolites—polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids—found in plants, which act as reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents, is the foundation of plant-mediated synthesis15,16. These biomolecules provide surface capabilities that can control biological activity in addition to aiding in the creation of nanoparticles17. Turmeric is well-known for its high quantity of essential oils, various phenolics, and curcuminoids, particularly curcumin, which have good reducing and biocompatible properties18,19. These elements improve the nucleation and development of nanoparticles by interacting with metal precursors via functional groups such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, and methoxy units20.

Turmeric alone has broad-spectrum antibacterial and antioxidant qualities in addition to being used in the creation of nanoparticles21. Curcumin and related compounds are broad-spectrum antagonists of several infections because they can sequester metal ions, disrupt microbial cell membranes, and prevent the formation of nucleic acids22,23. The creation of materials with inherent biological activity is an extra benefit of including such bioactive chemicals in the nanoparticle production process24. BiNiO3’s redox activity and this biogenic surface alteration may work in concert to enhance the material’s antibacterial and catalytic capabilities25.

Given the rising threat of antibiotic resistance, it is especially crucial to examine the antibacterial properties of BiNiO3 NPs made in this environmentally friendly manner. One of the biggest threats to global public health is the rise of bacterial and fungal diseases that are resistant to many drugs26. One possible remedy for resistant infections in this case is the development of nanomaterials with intrinsic antibacterial action. BiNiO3 NPs may effectively harm microbial cellular structures, disrupt metabolic processes, and induce oxidative stress because of their large surface area, nanoscale size range, and ability to generate ROS27,28. An efficient antibacterial platform may be produced by further enhancing its bioactivity via the combined action of phytochemicals derived from turmeric29. At the same time, since most synthetic dyes are poisonous, carcinogenic, and non-biodegradable, the ecological impact of industrial effluents, more especially, wastewater tainted with colors, has gained more attention30,31,32. One effective, but eco-friendly, method for degrading these contaminants is visible light-induced photocatalysis33,34. BiNiO3 NPs generate electron-hole pairs in response to light, which start redox processes that create superoxide ions and hydroxyl radicals, which further degrade complicated dye molecules into less harmful byproducts35,36. With the help of turmeric extract-derived bio-functional surface properties, green-synthesised BiNiO3 NPs ought to demonstrate improved photocatalytic activity in this situation when exposed to visible light.

Here, we report a green synthesis of BiNiO3 NPs using rhizome extract from Curcuma longa as a biological reducing and stabilizing agent. The production of bifunctional nanoparticles is facilitated by the biocompatible approach, which eliminates the need for harsh conditions or hazardous chemicals. The antibacterial activity studies and visible light-driven photocatalytic Rhodamine-B dye degradation properties of the produced BiNiO3 NPs were examined. These data demonstrate its multifunctional excellence, which holds promise for future uses in environmental clean-up and antibacterial activity.

Experimental

Chemicals and techniques

BiNiO3 NPs are synthesized using bismuth nitrate pentahydrate [Bi(NO3)3·5H2O] and nickel chloride hexahydrate [NiCl2·6H2O] as primary precursors. The structural, functional, optical, and morphological characteristics of the as-prepared BiNiO3 NPs have been examined using various characterization techniques. A Shimadzu 8400 S spectrophotometer was used to perform Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in the 400–4000 cm−1 range to identify the functional groups and validate metal–oxygen bonding. Using Cu Kα radiation and λ = 1.5418 Å, X-ray diffraction (XRD) examination was performed on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer to determine the crystallographic phase, purity, and crystallite size. To assess the optical absorption properties and ascertain the band gap energy, UV-visible absorption spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-2600 UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The same spectrophotometer was also used to monitor the photocatalytic activity of dye degradation by the BiNiO3 NPs. JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope (TEM) provided high-resolution features, was further used to cross-check particle size, shape, and agglomeration behaviour, while the ZEISS EVO 18 scanning electron microscope (SEM) examined surface morphology and particle size. Additionally, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted using a Kratos AXIS Ultra DLD spectrometer with a monochromatic Al Kα (hν = 1486.6 eV) X-ray source to investigate the elemental composition and chemical states of the elements, providing insights into the surface chemistry and oxidation states of Bi and Ni in the nanoparticles.

The characterized data underwent analysis through a range of software tools to ensure precise interpretation. The PXRD data were analyzed utilizing HighScore Plus 3.0.5, developed by PANalytic B.V. in Almelo, The Netherlands (https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/products/category/software/x-ray-diffraction/software/highscore-with-plus-option). Rietveld Refinements were conducted utilizing the FullProf Suite. The crystal structure was obtained from VEST, a freely accessible software (https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889811038970). The morphology was analyzed through FESEM and TEM images utilizing ImageJ, a free software available at https://imagej.net/ij/index.html. The complete RAW data from the characterization underwent analysis and processing for graphical representation utilizing Origin (Pro), Version 2024. OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA.

Preparation of turmeric rhizome extract

With the help of a plant taxonomist (Dr. Murali, University of Mysore), turmeric fingers were gathered from a farmland nearby in the Chamarajanagar district and deposited in the Herbarium lab at the University of Mysore (voucher code: 039-2012). Following three rounds of sterile water washing to clean the outside, the gathered fingers were rubbed with a grater to break them up into little pieces, left to dry in the Sun, and then processed in a grinder to a fine powder. A magnetic stirrer set at 470 rpm was used to mix 50 g of powder with 500 mL of distilled water at 60 °C for 30 min. The mixture was then allowed to cool at room temperature for 30 min. The concentration was then filtered through muslin cloth, and the collected extract was stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C for later use in the experiment.

Synthesis of bismuth nickel oxide bimetallic nanoparticle

1.5 g of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and 1.5 g of NiCl2·6H2O salts were stirred in an aqueous solution at 60° C for 2 h in a magnetic stirrer. At the time of stirring, 100 mL of turmeric rhizome extract was added to the above mixture dropwise. This was followed by cooling for 30 min, filtering using Whatman filter paper, and drying in a hot air oven at 90 °C for 1 h. Thus, the obtained material was finely powdered using a mortar and pestle, and calcinated for 2 h at 500 °C. The powder of bismuth and nickel bimetallic nanoparticles was collected and stored in a microcentrifuge tube for further analysis.

Antibacterial assay

The two pathogenic bacterial strains of Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) were tested for the antibacterial capability of the produced BiNiO3 NPs using the conventional agar well diffusion technique3738. The bacterial cultures were standardized to around 0.5 McFarland standard (∼10⁸ CFU/mL) after being cultivated fresh in the nutrient broth overnight. To create an even confluent lawn of growth, Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates were prepared and uniformly inoculated with the bacterial suspensions using sterile cotton swabs. A sterile cork borer (6 mm diameter) was used to punch four wells on each agar plate. Each well held 50 µL of suspensions of BiNiO3 NPs at concentrations from 200 to 800 µg/mL, respectively. After adding the BiNiO3 NPs, the plates were left at room temperature for 30 min to allow compound diffusion before incubation. After incubation, a digital Vernier caliper was used to measure the zones of inhibition around each well in millimeters (mm), and the average of the three readings was recorded. To ensure there was no external contamination or solvent influence, a control well containing sterile distilled water was also maintained.

Photoassisted degradation of Rhodamine-B dye

The degradation of Rhodamine-B (Rh-B) dye under visible light irradiation was used to examine the green-synthesized BiNiO₃ NPs’ photocatalytic activity39. For all degradation experiments, a stock solution containing 10 ppm of dye in deionized water was used. For every photocatalytic run, 40 mg of the BiNiO₃ catalyst was dispersed in 100 mL of the Rh-B solution in a 250 mL borosilicate beaker. The dark was agitated in the solution for half an hour before lighting to attain adsorption–desorption equilibrium between the catalyst surface and dye molecules. A 250 W tungsten halogen lamp placed at a fixed distance was then used to irradiate the mixture with visible light. To provide the catalyst with uniform light exposure throughout the experiment, constant stirring was ensured to occur.

3 mL aliquots were obtained at regular intervals (usually 10 min), centrifuged for ten minutes at 6000 rpm to separate the catalyst particles, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at the maximum absorption wavelength of Rh-B (λmax = 554 nm). The following formula was used to calculate the efficiency of deterioration (1)40:

Where A0 is the initial absorbance and At is the absorbance at time t. To evaluate the photocatalytic efficacy of the BiNiO3 NPs and ascertain the degradation rates, the data were plotted.

Results and discussion

Absorbance studies

Figure 1 displays the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the synthesized BiNiO3 NPs. The presence of BiNiO3 is confirmed by the maximum absorption peak at 316 nm41. Because of the particle size, the absorption peaks show a slightly broadened peak. According to UV-Vis’s absorption spectra. A small bump was found just above 700 nm in the spectrum, affirming the purity of the produced BiNiO3 NPs. Furthermore, the band gap was estimated by analysing the obtained spectrum through Tauc’s relation (2)42. The obtained result suggests that the estimated band gap is 2.90 eV (insight of Fig. 1), making the synthesized BiNiO3 suitable for photo-assisted processes like catalysis.

Structural studies

The crystalline characteristics of the synthesized BiNiO3 NPs were detailed through an analysis using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). The sample’s polycrystalline nature is confirmed by the observed PXRD pattern (Fig. 2a), which displays a well-known collection of diffraction peaks. Two primary phases are seen in the diffraction pattern, which correspond to the tetragonal structure of Bismoclite (BiClO) (ICDD #96-900-8427) and the cubic structure of Bunsenite (NiO) (ICDD #96-901-3981). The assigned hkl values for the corresponding peaks are mentioned in Table 1.

NiO and BiClO phases indicate that a multiphasic BiNiO3 NPs was formed during synthesis43. The structural data acquired using the VESTA program further helped the identification of these phases, demonstrating cubic symmetry for NiO unit cells and tetragonal symmetry for BiClO (Fig. 2b). Clarifying the inherent characteristics and potential multifunctional uses of the produced BiNiO₃ NPs requires this kind of structural knowledge. Also, three low-intensity impurity peaks that are unrelated to either of the two indexed phases were seen. These would result from unreacted precursors or trace quantities of secondary phases. Despite their very low intensity, these impurities are noteworthy for their completeness and may be improved in further synthesis. Furthermore, the crystallite size was evaluated using Scherrer’s method (3)44,

Where: Dhkl; crystallite size, k; shape factor (0.9), λ; wavelength of the x-rays used, β; Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), and θ: Diffracting angle. The evaluated crystallite size was found to be 16.55 nm, making it suitable for multifunctional applicability.

Functional group assessments

The identification of functional groups of the synthesized BiNiO3 NPs was conducted using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in the range 400–4000 cm−1. Numerous distinctive absorption bands in the turmeric rhizome extract’s FTIR spectra are suggestive of metal–oxygen bonding and lingering organic components that were probably acquired from plant extract or precursors. As depicted in Fig. 3, the stretching vibrations of O–H in adsorbed water molecules or hydroxyl groups on the surface are responsible for a broad band seen around ~ 3400 cm−145. A faint absorption peak about ~ 2920 cm−1 contains C–H stretching vibrations, which is attributed to residual organic species from turmeric extract46. It is possible to explain the distinctive absorption band at 1380–1450 cm−1 to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibration of NO₃− ions, which typically result from the breakdown of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate47. The Bi–O and Ni–O stretching vibrations of the perovskite-type oxide structure, which attest to the production of BiNiO3, are responsible for the strongest peaks in the BiNiO3 NPs spectra, which appear below 1000 cm−1 at around 550–650 cm−148. As is common in vibrations in the BiNiO3 tetragonal lattice, these low-frequency bands verify that Bi and Ni have been successfully incorporated into the oxide network49.

SEM analysis

Figure 4 displays the polydispersed distributions of the particle sizes in addition to the spherical and rod-like, pear-shaped morphology of as-synthesized BiNiO3 NPs. Furthermore, it has been discovered that the oxidation and aggregation of nickel and bismuth oxide nanoparticles are noticeable, most likely because the turmeric rhizome caps the Ni-Bi-O nanoparticles. The smaller, decreased nanoparticles attest to the turmeric rhizome’s ability to be used in the creation of nanoparticles50.

EDAX analysis

The EDAX analysis has been used to authenticate the precursor elements qualitatively, as shown in Fig. 5. The peaks for oxygen, bismuth, and nickel are visible in the photograph. Nonetheless, the compositional % shows that the proportion of bismuth element is higher than that of nickel and oxygen elements. Insights of Fig. 5 provide the weight and the fraction of atoms.

TEM analysis

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to examine the morphology, size, and distribution of the synthesized BiNiO₃ NPs. According to the TEM micrograph indicated in Fig. 6 (a-f), the majority of the nanoparticles had a spheroid shape, smooth surfaces, and a rather uniform size distribution. Because of their high surface energy and inter-particle interactions, nanoscale metal oxides often exhibit loose agglomeration of these spheroid particles. As predicted by the projected crystallite size based on XRD, the mean particle size falls between 15 and 20 nm. Aside from the common spheroid particles, the sample also has a secondary morphology of rod-like shapes dispersed thinly across it. Rod-like characteristics suggest the possibility of anisotropic development during nucleation, which might be controlled by precursor chemistry or synthesis conditions. Both morphologies might work in concert to improve electron transport and surface reactivity. The strong crystallinity of the BiNiO3 nanoparticles is further confirmed by the SAED image depicted in Fig. 6g. High purity and structural integrity are shown by the absence of any discernible secondary phase or amorphous component. Additionally, the lattice d-spacing was evaluated by HRTEM images depicted in Fig. 6h and 6i and found to be 0.346 nm. By permitting a variety of active surface orientations and enhanced light-scattering capabilities, this morphological variation—spheroid and rod-like shapes—may enhance the material’s performance in photocatalysis and sensing applications.

XPS analysis

The oxidation states of the synthesized BiNiO3 NPs were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The high-resolution Bi 4f spectrum (Fig. 7a) exhibits two distinct peaks at 158.88 eV and 164.18 eV, which are associated with Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, respectively. As anticipated, when Bi is present in a perovskite oxide lattice, these binding energies confirm that bismuth (Bi3+) is in the + 3-oxidation state50. Four major peaks can be seen in the Ni 2p spectra (Fig. 7b) at 855.15 eV, 861.26 eV, 872.84 eV, and 879.25 eV. The major peaks at 861.26 eV and 879.25 eV demonstrate the presence of Ni in the + 2 oxidation state typical of nickel in NiO-like environments, but the peaks at 855.15 eV and 872.84 eV are characteristic of Ni+2 ((Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2), while the peaks at 861.26 eV and 879.25 eV are satellite peaks confirming the oxidation state of Ni in the NiO environment51. Lattice oxygen (O2-) has a high peak at 529.79 eV in the O 1 s spectrum (Fig. 7c), whereas surface-adsorbed oxygen species such as hydroxyl groups or oxygen vacancies have a low-intensity peak at 531.38 eV. The development of surface reactivity may be significantly influenced by these oxygen species52. Additionally, peaks at 284.88, 289.08, 293.11, and 295.78 eV are seen in the C 1 s spectrum (Fig. 7d), which are indicative of carbonates, adventitious carbon pollution, and possible surface carbon-oxygen bonds53. The spectra show typical ambient exposure during handling but no interference from carbon species in the lattice. The effective synthesis of BiNiO3 containing Bi3+, Ni2+, and O2- species is often confirmed by the XPS analysis.

Antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial effectiveness of the synthesized BiNiO3 NPs was assessed against two bacterial pathogens—Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive)—using the agar well diffusion method. Nanoparticles have shown a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect, as depicted in Figs. 8(a) and 8(b). Both bacteria showed clear zones of inhibition around wells supplied with 200, 400, 600, and 800 µg of BiNiO3. Zone diameters for S. aureus (Fig. 8a) have shown increased proportionality with concentration, indicating a higher level of bactericidal action. For 600 and 800 µg, the zone diameters were about 17.33 ± 1.15 mm and 21.33 ± 1.15 mm, respectively. The broad-spectrum antibacterial potency of BiNiO3 was shown in the instance of E. coli (Fig. 8b), where a similar pattern was seen with clearly defined zones at all tested doses. The increase in growth inhibition diameter suggests that the nanoparticles interact with cell membranes, causing rupture or ROS production to limit bacterial growth54. The presence of Bi3+ and Ni2+ ions may have an additional impact via ion release processes that compromise bacterial integrity55. Perhaps as a result of differences in their cell wall architectures, S. aureus exhibited a comparatively greater sensitivity to the nanoparticles than E. coli. The findings show that BiNiO₃ nanoparticles are excellent antibacterial agents with promising potential for use in medicine or as antimicrobial coatings.56,57,58

Photocatalytic degradation analysis

A thorough investigation into the light-induced photocatalytic breakdown of Rh-B dye by prepared BiNiO3 NPs revealed the catalyst’s critical role in the breakdown process. The dye’s characteristic absorbance band (at around 550 nm) showed clear degradation in UV-Visible spectroscopy of Fig. 9(a), going from a high initial level to almost nothing within 100 min. The photocatalytic process outperformed the photolysis alone in kinetic measurements, as showcased in Fig. 9(b), eliminating over 93% of the dye in 100 min, compared to less than 10% degradation for the photolysis alone. After the first cycle, the degradation rate with the catalyst reached 93.82% as depicted in Fig. 9(c), demonstrating effective photocatalytic activity, with degradation efficiency increasing linearly with illumination time.

The photocatalyst’s reusability was also evaluated over multiple cycles after several centrifugations and washes with ethanol to remove dye residues, and the results demonstrated exceptional stability and degradation efficiency over the long term. Figure 9(d) indicates a slight decrease in performance from 93.82 to 88.56% over 4 cycles. This is attributed to the surface buildup or loss of a portion of the photocatalyst. These findings provide credence to the photocatalyst’s effectiveness and recyclable nature in removing dye pollutants from water environments, paving the way for additional optimization and mechanistic studies to enhance performance and understand degradation processes better59.

By fitting experimental data into 0th, 1 st, and 2nd -order kinetic models, the degradation kinetics of Rh-B were investigated (Fig. 10). The best linear fit, with an adjusted R² value of 0.8334 for the logarithmic plot (Log(C0/C) v/s illumination time), was found using linear regression of the transformed concentration data against illumination time. A value of 0.01031 min−1 was determined for the first-order rate constant (k). Nevertheless, the experimental data showed significantly weaker correlations with the second-order (1/C vs. time) and zero-order (C0/C vs. time) models, with adjusted R-squared values of 0.48569 for both. The findings show that Rh-B degradation under the studied circumstances is a pseudo-first-order process, with the rate of degradation being directly correlated with the Rh-B concentration. Understanding the reaction process and developing efficient degradation strategies for dye pollutants are both aided by this kinetic data.

The efficacy of photocatalytic degradation was greatly affected by the dosage of the photocatalyst. Figure 11(a) indicates that the degradation efficiency increased significantly from around 45–93% after 100 min of illumination time when the dosage was raised from 10 mg to 40 mg. But when the photocatalyst dosage was increased to 55 mg, the efficiency dropped to about 69%. This suggests that the photocatalytic reaction may be hindered by factors such as increased light scattering or particle agglomeration beyond a certain dose of photocatalyst, which is likely to be around 40 mg in this instance60. The efficiency of degradation was also significantly affected by the original dye concentration, as depicted in Fig. 11(b). The degradation efficiency was approximately 65% at a low dye concentration of 5 ppm. An efficiency of around 93% was achieved at a dye concentration of 10 ppm. But when the dye concentration was raised to 15 ppm and 20 ppm, the efficiency fell to around 62% and 50%, respectively. This indicates that while it’s true that more reactant molecules are available at a higher concentration of a particular dye, there is an optimal concentration beyond which light penetration constraints and reduced active sites availability per dye molecule reduce degradation efficiency61.

Furthermore, the photocatalytic degradation was significantly affected by the solution pH. The pHpzc, or zero charge point, of the catalyst was determined to be 5.3 (Fig. 11c). At a pH of 5.5, the degradation efficiency reached its peak at about 93% following a certain amount of illumination time. Degradation efficiency was reduced a little, by around 70%, at an exceedingly acidic pH of 2.4. Around 65% and 45% of the degrading effectiveness, respectively, was seen after the same period as the pH increased to 7.8 and 9.2, respectively, as indicated in Fig. 11(d). An explanation for the degrading phenomenon that depends on pH is that the ionic nature of the pollutants and changes in the catalyst’s surface charge, concerning pHpzc influence the electrostatic interactions and adsorption at the catalyst surface62. Surface charge and pollutant speciation interact synergistically to enhance adsorption and subsequent photocatalytic degradation, as indicated by the maximum degradation efficiency at around pHpzc.

Benzoquinone (BQ) served as a scavenger for superoxide radicals (O₂•-), ammonium oxalate (AO) was used to scavenge holes (h+), tert-butanol (TBT) acted as a second scavenger for hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) was employed to capture hydroxyl radicals (•OH) to identify the primary reactive species involved in the photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B using BiNiO3 nanoparticles. It is clear from Fig. 12 that the degradation efficiency dropped significantly to 42.58% with IPA, compared to 58.67% with TBT, indicating that hydroxyl radicals play a major role in the photocatalytic process, with IPA being a more effective scavenger for •OH species63. In contrast, the presence of BQ and AO led to relatively minor decreases in degradation efficiency (to 87.54% and 86.47%, respectively), suggesting that both superoxide radicals and photogenerated holes have a minor or secondary contribution to the overall photocatalytic process. All these findings point to hydroxyl radicals as the primary reactive species responsible for dye degradation, with superoxide radicals providing a secondary contribution.

Under visible light, the photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine-B (Rh-B) using green-synthesised BiNiO3 nanoparticles entails a series of redox reactions that are started by photon absorption. BiNiO3 nanoparticles generate electron–hole pairs when exposed to visible light; holes (h+) are left in the VB while electrons (e−) are stimulated from the VB to the CB. The charge carriers produced by photolysis play a crucial role in the start of degradation processes. Scavenger experiments have shown that the primary oxidative species responsible for Rh-B degradation are the highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which are created when the holes (h+) react with water molecules adsorbed on the surface (H2O) or hydroxide ions (OH−). The dye molecules are broken down and oxidized by the •OH radicals, which causes the chromophoric unit to cleave and further mineralize into non-toxic by-products. Superoxide radicals (O2−•) are produced concurrently by the photoexcited electrons (e−) in the CB, reducing adsorbed oxygen on the surface. These radicals may then contribute to the production of additional •OH via intermediary chemistry. However, the primary function of •OH radicals outweigh their contribution. It is also believed that the presence of bioactive phytochemicals from the extract of Curcuma longa helps to sustain the photocatalytic cycle by encouraging charge separation and recombination inhibition64,65.

Plausible degradation pathways

The photocatalytic degradation of Rh-B dye by BiNiO₃ nanoparticles was thoroughly examined using LC-MS measurement of the reaction mixture after 100 min of visible light irradiation. The data in Fig. 13 shows that Rh-B degrades via two major routes. In Pathway-1, the first step is sequential N-deethylation of Rh-B (compound A, C28H31N2O3) to generate intermediate B (C26H27N2O3). Intermediates C (C22H19N2O3), D (C20H14N2O3), and E (C20H15NO3) are formed by further amine demethylation and oxidation. Intermediate E includes chromophore breaking and aromatic ring opening, resulting in F (C19H14O), G (C13H11NO), and benzoic acid as the ultimate low-molecular-weight products of degradation. Similarly, in Pathway-2, Rh-B degrades into intermediate H (C24H23N2O3) via N, N-diethyl group elimination. This is followed by sequential deamination and dealkylation reactions to create intermediates I (C23H23N2O), J (C22H21N2O), and finally K (C21H20NO), indicating severe structural degradation of the dye molecule. These routes unambiguously demonstrate the dye’s step-by-step disintegration via deethylation, ring cleavage, and the formation of simpler, less hazardous aromatic molecules.

The identified intermediates indicate that BiNiO3 NPs possess high photocatalytic activity, attributable to their appropriate bandgap, redox potential, and active surface locations. BiNiO3 is an effective photocatalyst for treating dye-polluted wastewater due to its ability to detoxify and mineralize Rh-B via degradation. Table 2 provides a full review of the degradation intermediates and their relevant structural features, while Fig. 14 depicts the related LC-MS spectral data, representing the fragmentation pattern when the dye undergoes degradation, and its graphical representation is shown in Fig. 15.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a green synthesis of BiNiO3 nanoparticles using Curcuma longa rhizome extract, providing an ecologically friendly alternative to traditional chemical procedures. Turmeric’s phytochemical constituents were effective stabilizing and reducing agents, which promoted the creation of nanoparticles in moderate environments. A highly crystalline multiphase perovskite structure with tetragonal (ICDD #96-900-8427) and cubic (ICDD #96-901-3981) phases was detected by XRD investigation. The UV-Vis spectra confirmed its photocatalytic capabilities by showing strong visible light absorption at a 2.90 eV band gap. The wide band in the FTIR spectrum, which represents metal–oxygen interaction and phytochemical bonding, ranged from 550 to 650 cm−1. The particle sizes ranged from 15 to 20 nm, and the TEM and FESEM revealed quasi-spherical, rod-like, and pear-shaped morphologies. The elemental composition was verified by EDX analysis, which showed the distinctive O 1 s peak at 529.79 eV. Significant antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (21.33 mm) and Escherichia coli (22.66 mm) was observed at 800 µg. Additionally, photocatalytic tests showed that, following 100 min of exposure to visible light, Rh-B dye degraded by 93.82%. The reduced band gap, effective charge separation, and surface phytochemical functions are the causes of the increased activity. These findings support the multipurpose potential of turmeric assisted BiNiO3 nanoparticles for wastewater treatment and antibacterial applications, offering a more environmentally friendly and efficient alternative to chemically produced nanomaterials.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article.

References

Hachem, K. et al. Methods of chemical synthesis in the synthesis of nanomaterial and nanoparticles by the chemical deposition method: A review. BioNanoScience 12 (3), 1032–1057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-022-00996-w (2022).

Jain, K., Takuli, A., Gupta, T. K. & Gupta, D. Rethinking nanoparticle synthesis: A sustainable approach vs. Traditional methods. Chem. – Asian J. 19 (21), e202400701. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.202400701 (2024).

Parveen, K., Banse, V. & Ledwani, L. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: their advantages and disadvantages. AIP Conf. Proc. 1724 (1). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4945168 (2016).

lawal, H., Saeed, S. I., Gaddafi, M. S. & Kamaruzzaman, N. F. Green nanotechnology: naturally sourced nanoparticles as antibiofilm and antivirulence agents against infectious diseases. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025 (1), 8746754. https://doi.org/10.1155/ijm/8746754 (2025).

Irshad, M. A. et al. Challenges and Perspectives of Green Nanotechnology. In J. M. Al-Khayri, T. R. Anju, & S. M. Jain (Eds.), Nanomaterial Green Synthesis (pp. 547–595). Springer Nature Switzerland. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-84643-4_18

Naryal, S. et al. Navigating Sustainable and Healthy Future: Green Nanotechnology, Regulatory Priorities, and Challenges. In R. C. Sobti (Ed.), Role of Science and Technology for Sustainable Future: Volume 2- Applied Sciences and Technologies (pp. 353–369). Springer Nature Singapore. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-5177-8_19

Wang, P. et al. High performance ultraviolet photodetector based on lead-free bismuth perovskite heterojunction. Bull. Mater. Sci. 48 (1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-024-03338-6 (2024).

Eissa, A. M., Elseman, A. M., Misbah, M. H. & El-Kemary, M. Tuning optical properties of sustainable inorganic bismuth-based perovskite materials with organic ligands. J. Mol. Struct. 1321, 140183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.140183 (2025).

Sahoo, L., Behera, S. A., Achary, P. G. R. & Parida, S. K. Exploring the structural, microstructural, dielectric, electrical, and optical properties of lanthanum-modified Bi2FeMnO6 double perovskite for some device applications. Eur. Phys. J. Special Top. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-025-01675-z (2025).

Nguyen, V. Q. et al. Effect of annealing temperature on morphology, optical, and photocatalytic characteristics of hydrothermally synthesized Bi(Ti0.5Co0.5)O3 perovskite nanorods. J. Power Sources. 631, 236240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2025.236240 (2025).

Long, D., Yu, X., Li, W. & Ma, S. One bismuth three benefits: an overview of bismuth-based photocatalysts for energy conversion, environmental treatment and biomedical applications [10.1039/D4MA00493K]. Mater. Adv. 6 (2), 508–526. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4MA00493K (2025).

Soomro, R., Abdelmonem, M., Meli, A. D., Panhwar, M. & Che Abdullah, C. A. A novel plant-based approach for synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles and cancer therapy. Discover Chem. 2 (1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44371-025-00091-5 (2025).

Reddy, M. U., Pachiyappan, J. & Sivamani, S. Chapter 1 - Plant-biomass-based nanomaterials for sustainable energy. In Inamuddin, T. Altalhi, & J. Iqbal (Eds.), Biomass Conversion through Nanomaterials (pp. 1–25). Elsevier. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-24748-4.00001-5

Sawicka, B. Introduction: The Role of Phytochemicals in Drug Discovery. In B. Sawicka, M. Messaoudi, & A. Rebiai (Eds.), Biotechnology and Phytochemical Prospects in Drug Discovery (pp. 1–6). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-2790-5_1

Devra, V. Role of Agroforestry Plants in the Synthesis of Nanoparticles. In D. Jabborova, D. Sarkar, R. S, R. Datta, & S. Singh (Eds.), Nanomaterials in Agroforestry Systems (pp. 19–40). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-1337-3_2

Singh, P. & Singh, R. K. Emerging Nano-Phytochemicals-Based Sustained Drug Delivery System for Cancer Therapeutics. In N. Puranik (Ed.), Nano-formulation of Dietary Phytochemicals for Cancer Management (pp. 375–400). Springer Nature Singapore. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-8005-1_14

Kishore, A., Singh, C. & Kaur*, G. Bio-nanomaterials: An Introduction. In Bio-Nanomaterials in Environmental Remediation (pp. 1–46). (2025). https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527848546.ch1

Kouadri, I., Seghir, B. B., Cherif, N. F. & Rebiai, A. Nanomaterials Synthesis and Medicinal Plant Extracts. In B. Sawicka, M. Messaoudi, & A. Rebiai (Eds.), Biotechnology and Phytochemical Prospects in Drug Discovery (pp. 103–131). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-2790-5_4

Kumar Singh, R., Nallaswamy, D., Rajeshkumar, S. & Varghese, S. S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Neem and turmeric extract and its antimicrobial activity of plant mediated silver nanoparticles. J. Oral Biology Craniofac. Res. 15 (2), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2025.02.005 (2025).

Gangal, A. et al. Green nanotechnology: nanoparticle synthesis using curcuma amada, curcuma caesia, curcuma longa, and curcuma Zedoaria. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 18 (1), 2449122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2024.2449122 (2025).

Roney, M., Huq, A. K. M. M., Rullah, K., Zamri, N. B. & Mohd Aluwi, M. F. F. Curcumin, a bioactive compound of turmeric (Curcuma longa) and its derivatives as α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 83 (1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-024-01477-5 (2025).

Ashaolu, T. J., Can, K. A., Ali, R., Jafari, S. M. & and Recent advancements in Curcumin extraction, chemical/bio-synthesis, purification, and food applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 65 (14), 2714–2730. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2024.2349725 (2025).

Rai, M. & Golinska, P. M., F. C., P., I. A.,and Harnessing bioactive Nanocurcumin and Curcumin nanocomposites to combat microbial pathogens: a comprehensive review. Critical Reviews Biotechnology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2025.2458006

Mukhtar, A. et al. Enhanced role of flower shaped Curcumin loaded ZnO/Ag2O nanocomposites for biological applications. BioNanoScience 15 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-024-01711-7 (2024).

Modupe, O. U. et al. Green hydrothermal synthesis of nickel and zinc-doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles using < em > dalbergiella welwitschii extracts and their biological studies. Heliyon 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40759 (2025).

Ehsan, H. Antibiotic resistance in developing countries: emerging threats and policy responses. Public. Health Challenges. 4 (1), e70034. https://doi.org/10.1002/puh2.70034 (2025).

Panda, L., Pradhan, A., Sahoo, R. K., Achary, P. G. R. & Nanda, B. Impact of plasmonic silver on the perovskite Bi9Ti6FeO27: removal of Tetracycline and antimicrobial activity. J. Mol. Struct. 1321, 140281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.140281 (2025).

Pancotti, A. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of bismuth ferrites nanoparticles in the Inhibition of E. Coli and S. Aureus bacteria. Chem. Biodivers. 22 (1), e202402048. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.202402048 (2025).

Janesomboon, S. et al. Synergistic antibacterial activity of Curcumin and phage against multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 8959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94040-y (2025).

Barik, D. et al. Environmental Pollutants Such as Endocrine Disruptors/Pesticides/Reactive Dyes and Inorganic Toxic Compounds Metals, Radionuclides, and Metalloids and Their Impact on the Ecosystem. In P. Verma (Ed.), Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability (pp. 391–442). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-7221-6_15

Thakur, S., Chandra, A., Kumar, V. & Bharti, S. Environmental Pollutants: Endocrine Disruptors/Pesticides/Reactive Dyes and Inorganic Toxic Compounds Metals, Radionuclides, and Metalloids and Their Impact on the Ecosystem. In P. Verma (Ed.), Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability (pp. 55–100). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-7221-6_3

Kaur, J., Tewari, S., Kaur, A. & Malik, R. Dye and Dye-Containing Hazardous Waste in Water Resource. In H. Gupta, S. Madhav, S. Dhiman, & R. Mishra (Eds.), Emerging Contaminants in Water and Wastewater: Sources and Substances (pp. 179–199). Springer Nature Switzerland. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-82579-8_8

Ayub, A. et al. Advancing Dye Degradation: Integrating Microbial Metabolism, Photocatalysis, and Nanotechnology for Eco-Friendly Solutions. Bacteria, 4(1), 15. (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2674-1334/4/1/15

Champati, A., Sahu, P. K., Naik, B. & Pradhan, A. Unveiling enhanced photocatalytic antimicrobial activity by functional inorganic metal nanocomposite. BioNanoScience 15 (1), 183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-024-01781-7 (2025).

Sen, M. Photo-Redox Reactions: Definition and Classification. In M. Sen & D. Ray (Eds.), Emerging Trends in Photoredox Synthetic Transformation (pp. 1–15). Springer Nature Singapore. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-8205-5_1

Cabanero, D. C. & Rovis, T. Low-energy photoredox catalysis. Nat. Reviews Chem. 9 (1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-024-00663-6 (2025).

El-Khawaga, A. M. et al. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their antibacterial activity and photocatalytic degradation. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 15 (2), 2673–2684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04827-0 (2025).

Abdel-Nasser, A., Fathy, H. M., Badr, A. N., Barakat, O. S. & Hathout, A. S. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with lactobacillus rhamnosus bioactive metabolites: preparation, characterization, and antifungal activity. Heliyon 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41875 (2025).

Kumar, K. J. et al. Fe-doped NiO nanopowders for advanced photochemical applications: synthesis, characterization, photo-assisted dye degradation and latent fingerprint visualization. Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 701, 416991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2025.416991 (2025).

Jhansi, K. & Swaminathan, P. Photocatalytic dye degradation with magnetically recoverable and reusable bismuth ferrite nanoparticles. J. Electron. Mater. 54 (1), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-024-11574-z (2025).

Merugu, R. et al. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of bimetallic silver and copper nanoparticles using fruit pulp aqueous extracts of Moringa oleifera. Materials Today: Proceedings, 44, 153–156. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.549

Majani, S. S. et al. Fe-doped SrZrO3 nanostructures as photocatalyst: Solid-state synthesis and UV-light driven eradication of thymol blue dye. Mater. Res. Bull. 183, 113184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2024.113184 (2025).

Stroyuk, O. et al. Experimental design of (Cs,Rb)2Sn(Bi)Cl6 blue phosphors by cation-substitution-induced lattice strain [10.1039/D4TC03749A]. J. Mater. Chem. C. 13 (5), 2303–2311. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4TC03749A (2025).

Aarti, D. P., Basavaraj, R. B., Reddy, M., Majani, S. S. & M. B., & Multifunctional hybrid red fluorescent nanopigments: photoluminescence, photocatalytic and advanced forensic applications. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.03.156 (2025).

Vignesh, T., Selvakumar, D. & Jayavel, R. Multi-Spectral techniques for detecting adulterants in turmeric powder. Microchem. J. 209, 112830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2025.112830 (2025).

Pasieczna-Patkowska, S., Cichy, M. & Flieger, J. Application of fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in characterization of green synthesized nanoparticles. Molecules 30 (3), 684 (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/30/3/684

Guo, Y. et al. Bio-green synthesis of bismuth oxide nanoparticles using almond gum for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of water pollutants and biocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 300, 140222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.140222 (2025).

Dash, A., Ragavendran, C. & Rajendran, R. Biogenic nickel oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and biomedical potential. Mol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-025-01413-9 (2025).

Kumar, R., Gupta, V. K. & Kumar, U. (Sr1-xCax)2SnO4 microwave dielectric ceramics with Ruddlesden-Popper structure (x = 0–0.06) for microwave application. Next Mater. 8, 100748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxmate.2025.100748 (2025).

Mansoorie, F. N., Bhatt, P., Tewari, A., Kumar, R. & Bag, M. Unveiling the impact of Bi3 + Heterovalent doping on the negative capacitance and ionic conductivity of perovskite single crystals: implication in neuromorphic computing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 17 (2), 4218–4230. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c18821 (2025).

Zhou, Z. et al. Direct Blue-LED Pumped Broadband Long-Wavelength Near-Infrared Emitter Based on Ni2 + Mono-Doped Double Perovskite Materials for Versatile Optical Applications. Laser & Photonics Reviews, n/a(n/a), 2402099. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202402099

Sun, X. et al. Recent advances in perovskite oxides for oxygen evolution reaction: structures, mechanisms, and strategies for performance enhancement. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35 (10), 2416705. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202416705 (2025).

Monti, N. B. D. et al. Effects of Annealing Conditions on the Catalytic Performance of Anodized Tin Oxide for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Nanomaterials, 15(2), 121. (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/15/2/121

Nguyen, H. N. et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanisms of Magnesium-Doped Baghdadite bioceramics for orthopedic implants. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 5 (2), 2400119. https://doi.org/10.1002/anbr.202400119 (2025).

Fakher, S., Westenberg, D. & and Properties and antibacterial effectiveness of metal-ion doped borate-based bioactive glasses. Future Microbiol. 20 (4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460913.2025.2470029 (2025).

Liting, X. et al. Spireoside controls blast disease by disrupting membrane integrity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Rice Sci. 32 (1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsci.2024.10.005 (2025).

Aljuwayd, M. et al. Disinfectants and one health review: the role of reactive oxygen species in the bactericidal activity of Chlorine against Salmonella. One Health. 20, 100989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.100989 (2025).

Chen, C. et al. Antifungal activity of a maleimide derivative: disruption of cell membranes and interference with iron ion homoeostasis. Mycology 16 (1), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2024.2330403 (2025).

Wang, W. et al. Preparation of Recyclable Magnetic Catalyst (Pd/PDA@Fe3O4) and the Catalytic Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol and Rhodamine B. Catalysts, 15(2), 175. (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4344/15/2/175

Anuradha, Singh, A., Seth, R. K., Kumar, P. & Kumar, S. Optimizing operational parameters for improved photocatalytic activity of hematite–rGO nanocomposites in methylene blue dye degradation. Eur. Phys. J. B. 98 (1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/s10051-024-00849-3 (2025).

Ahmad Ramli, S. et al. MoS₂-decorated etched-TiO₂ rods film for superior photocatalytic dye degradation. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 114 (2), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-025-06702-y (2025).

Adaileh, A., Abu-Rayyan, A., Khasawneh, A. & Alahmad, W. A comparative study of GO/TiO2/SiO2 catalysts for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and phenolic compounds. Environ. Qual. Manage. 34 (3), e70058. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.70058 (2025).

Mazarji, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and enhanced photocatalytic dye degradation: optimizing graphene-based ZnO-CdSe nanocomposites via response surface methodology. J. Alloys Compd. 1010, 177999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.177999 (2025).

Thamir, K. H. et al. Hydrothermally synthesized Fe-Doped bismuth oxide/cuo nanocomposites for efficient photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-025-03722-7 (2025).

Remila, A., Shally, V., Parvathiraja, C. & Darwin, T. Exploration of photoactive Cd2 + Substitutions on V2O5 nanoparticles and their catalytic potential against the toxic dye. Iran. J. Sci. 49 (1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40995-024-01704-x (2025).

Acknowledgements

Authors extend their appreciation to JSSSTU and the Director, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Mysuru Campus, for providing instrumentation and infrastructure facilities. The author acknowledges JAIN deemed to be university for providing instrumentation facilities. The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-734), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for their support.

Funding

Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-734), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.K., S.S.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis; K.B.N., S.S.M., B.S., R.K.M., S.H.C., H.A.B., P.B.S.S., S.P.K.: Data curation, Investigations, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation. M.I, K.S.A., C.S., R.G.A., V.S., E.S., S.P.K.: Visualization, Project administration, validation. S.P.K.: Resources, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kishor, B.N., Majani, S.S., Rajeshwari, K.M. et al. Bismuth nickelate nanoparticles synthesized using Curcuma longa rhizome extract as biocidal and photocatalytic agents. Sci Rep 15, 35692 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19626-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19626-y