Abstract

The growing demand for sustainable packaging, stricter regulations on non-biodegradable plastic waste, and increasing consumer awareness of environmental pollution are driving the development of water-soluble packaging materials. This study investigates the potential of lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) derived from spruce kraft lignin (SKL) and eucalyptus kraft lignin (EKL), as functional additives in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based films to achieve an optimal balance between high transparency and effective UV protection. To improve LNP dispersion within the PVA matrix, hydrophobic domains were introduced into lignin via acetylation, as confirmed by ³¹P NMR spectroscopy. The morphology of the nanoparticles was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The resulting PVA–LNP nanocomposite films exhibited excellent transparency and outstanding UV-shielding capabilities. UV–Vis spectroscopy confirmed the UV-blocking performance of the films, revealing that EKL-derived nanoparticles (EKL-C1) enhanced UV absorption more than eightfold compared to neat PVA, while SKL-derived nanoparticles (SKL-C1) achieved a 6.5-fold increase. This superior performance can be attributed to the higher syringyl (S) unit content and abundant methoxy groups in EKL-C1, which can improve UV absorption efficiency. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) further demonstrated smoother surface morphologies for EKL-C1-containing films, indicating improved nanoparticle dispersion and reduced aggregation. Mechanical testing before and after UV exposure confirmed the suitability of the films for packaging applications. These findings highlight the potential of lignin-based nanocomposite films as eco-friendly packaging and coating materials, offering a unique combination of high transparency and robust UV protection while, providing valuable insights into the structure–property relationships of lignin nanoparticles in biodegradable polymer films.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, water-soluble packaging has gained a particular attention among manufacturers of consumer goods. This trend is driven by increasing global consumer awareness of environmental issues such as plastic pollution and the accumulation of synthetic, non-biodegradable materials, as well as stricter government regulations on waste management1. According to a report by Future Market Insights, the water-soluble packaging market is predicted to reach US$ 4,786 million by 20332, making it a key contributor to the circular economy with a strong emphasis on sustainability and waste reduction. Major companies are investing in research to diversify the application of water-soluble packaging materials and improve of their performance.

Currently, among water-soluble polymers, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) is the most widely produced3. PVA is a hydrophilic, synthetic, biodegradable polymer obtained by polymerizing vinyl acetate into polyvinyl acetate, followed by hydrolysis of the acetate groups. It is one of the few vinyl polymers that are soluble in water and ultimately biodegradable4. In natural conditions, the hydroxyl groups in PVA are first oxidized to diketones, which are then hydrolized at the carbon‑carbon diketone bonds. In the final step, microorganisms degrade the polymer completely into to CO2 and H2O5. PVA is well known for its excellent film-forming and adhesive properties. Its main industrial applications include the textile industry, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products. It has also gained significant attention in the field of advanced multifunctional packaging, mainly due to its non-toxicity, biodegradability, and high transparency. The safety of PVA has been confirmed by the FAO/WHO Joint Committee of Experts on Food Additives6,7. After industrial use, PVA is typically transported via wastewater to treatment plants, where it undergoes degradation. However, when applied in agriculture, it tends to persist in the soil and exhibits low biodegradability8. Therefore, it is important to identify effective fillers that can enhance the properties of PVA, resulting in more environmentally friendly final material.

Lignin is a promising filler for PVA foils. As the second most abundant biomass resource in plants, it is relatively inexpensive and widely available9. Commercially, Lignin is a by-product of the pulp and paper industry, which produces more than 50 million tons of lignin annually. Most of it is burned as a low-value fuel to recover energy and chemicals – a necessary step in the kraft pulping process, which leads to severe resource underutilization. However, with the development of modern extraction technologies such as LignoBoost and LignoForce, it is now possible to isolate a portion of lignin from black liquor, making it increasingly available for value-added applications10.

Lignin possesses a unique chemical structure, rich in functional groups such as hydroxyl, methoxyl, carboxyl groups, carbonyl, and quinone groups. These functional groups enable its application in polymer materials, where it can impart valuable properties such as ultraviolet (UV) absorption, antibacterial activity and antioxidant properties11. Among these, UV protection is particularly deserves special attention12,13,14,15,16,17. Lignin’s excellent UV absorbing capacity is attributed to its aromatic rings, methoxy groups, and conjugated double bonds18,19,20.

Pure PVA has poor resistance to UV radiation and undergoes degradation upon exposure to UV light21, which compromises the structural integrity and long-term performance of PVA-based coatings. To enhance UV stability and extend material durability, lignin, particularly in the form of lignin nanoparticles (LNPs), can be incorporated into the PVA matrix due to its strong UV-absorbing capacity. In addition to improving UV resistance, the use of lignin contributes to the sustainable development of bio-based nanocomposites and supports biomass valorization by utilizing an abundant industrial byproduct22,23,24.

It is important to note that strong hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions within lignin can lead to agglomeration and irregular distribution of hydrophobic and polar groups in lignin aggregates. This, in turn, reduces the miscibility between lignin and PVA, potentially causing macroscopic phase separation. On the other hand, based on the observations provided by25, lignin is still capable of forming hydrogen bonds with PVA, even though the blend system remains immiscible. To improve miscibility between lignin and PVA, lignin must be homogeneously distributed within the PVA matrix. This can be effectively achieved by incorporating lignin in the form of nanoparticles26,27. This improves interfacial compatibility and enhances the barrier properties of the resulting composite. The improved interaction between the polymer matrix and lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) can be attributed to their increased specific surface area and abundance of surface-active sites, which facilitate better dispersion and integration within the host matrix28,29. Another key factor influencing miscibility is the structure of lignin, particularly the presence of hydroxyl groups. A higher content of ether linkages and hydroxyl groups can promote better miscibility with PVA30,31,32.

The novelty of this study lies in the use of acetylated lignin nanoparticles derivied from two distinct sources, spruce and eucalyptus, to develop transparent PVA foils with significantly enhanced UV-shielding properties. By improving nanoparticle dispersion through acetylation and establishing a correlation between lignin structure and UV absorption performance, this work offers new insights into the structure–function relationship in biopolymer composites. The comparative analysis, combined with a proposed UV-blocking mechanism, distinguishes this work from prior studies and highlights lignin’s potential as a sustainable additive for high-performance biodegradable packaging material.

Materials and methods

Materials

LignoBoost spruce kraft lignin (SKL) and LignoBoost eucalyptus kraft lignin (EKL), extracted from the corresponding black liquors using LignoBoost technology, were kindly provided in powder form (95% dry) by Stora Enso and Suzano pulp and paper companies. PVA was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Mw 13,000–23,000, 87–89% hydrolyzed).

Acetylation of lignin samples

The acetylation of lignin was carried out according to the method by26. Initially, 1 g of dried kraft Lignin, obtained from either Norway spruce or eucalyptus, was dispersed in 30 mL of pyridine until fully dissolved. Subsequently, 20 mL of acetic anhydride was gradually added in three equal portions at three-hour intervals after adding pyridine. The reaction mixture was continuously stirred at high speed for 30 h. Upon completion, the dark solution was Transferred into 500 mL of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid and left to precipitate in an ice bath for 30 min. The precipitate was then collected using a 0.45 μm nylon filter, thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and left to dry on the filter at room temperature for 48 h.

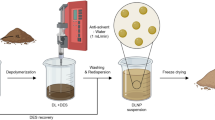

Synthesis of lignin nanoparticles (LNPs)

Acetylated lignin samples were dissolved in a mixture of acetone and water (4:1, v/v) to prepare a solution with a Lignin concentration of 1 mg/mL. To eliminate undissolved particles and potential aggregates, the solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. While stirring at a moderate speed, four volumes of deionized water were gradually added dropwise to the Lignin solution to induce nanoprecipitation. The mixture was then stirred continuously for two days, allowing the acetone to fully evaporate. The final Lignin concentration in the nanoparticle suspension was 0.24 mg/mL33.

Preparation of foils

A total of 5.0 g of poly(vinyl alcohol) and 90 ml of distilled water were placed in a 250 ml three-necked flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a thermometer, and a reflux condenser. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min and then left to stand for 24 h. Subsequently, the contents of the flask were heated to 80–85 °C and stirred at 300 rpm for 3 h using a mechanical stirrer. The resulting clear aqueous PVA solution was diluted with distilled water to a final volume of 100 ml. The films were cast in Petri dishes with a diameter of 8 cm. The prepared samples were then placed in a dryer and left for 24 h. Increasing amounts of the solution of LNPs were incorporated into the PVA matrix, as shown in Table 1. The final thickness of the lignin/PVA films was approximately 0.3 mm on average.

Methods

The functional groups in lignin samples were quantified using 31P NMR spectroscopy, following established methods34,35. Around 28–32 mg of the original (SKL and EKL) or acetylated (SKL-C1 and EKL-C1) Lignin sample was dissolved in 100 µL each of DMF and pyridine. Endo-N-hydroxy-5-norbornene-2,3-dicarboximide (40 mg/mL) was used as an internal standard, and chromium (III) acetylacetonate (5 mg/mL) acted as a relaxation reagent. Phosphorylation was performed with 2-chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaphospholane, and the derivatized sample was dissolved in CDCl₃ before analysis. 31P NMR spectra were recorded using inverse-gated proton decoupling with a 90° pulse angle, a 10 s delay time, and 256 scans, with a total acquisition time of 29 min.

A transmission electron microscope (TEM) was utilized to examine the core-shell structure of lignin nanoparticles. Imaging was conducted using a Hitachi HT7700 series instrument (Hitachi, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 100.0 kV and an emission current of 8.0 µA.

SEM micrographs were taken using an FEI Phenom-World scanning electron-ion microscope. The AFM images were recorded using the Veeco Nanoscope V microscope (USA) for the surface mapping of the fabricated materials and to calculate the average (Ra) and the root mean square (Rq) roughnesses.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the films were obtained using a Thermo Nicolet 8700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a Smart Orbit™ diamond ATR and a DTGS (deuterated triglycine sulfate) detector. The DTGS detector ensured stable signal performance within the mid-infrared spectral range (4000–400 cm−1). After applying baseline correction, ATR adjustment, and scaled normalization, the processed spectra were equivalent to transmission spectra.

UV-Vis electronic absorption spectra of nanocomposite foils were recorded using a dual-beam UV-Vis Cary 300 Bio spectrophotometer (Varian), which includes a thermostatted tray for a 6 × 6 Peltier block. The instrument allows for measurements in different solutions as well as in polymer coatings, as was necessary for this study, using a specialized attachment designed for solid samples. Temperature regulation during the measurements was controlled by a thermoelectric probe (Cary Series II from Varian).

The UV-blocking efficiency of PVA and PVA-LNP composite films was assessed using a Shimadzu UV-2600 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere. The spectra of films, normalized to a thickness of 0.3 mm, were recorded over a wavelength range of 200–600 nm. All measurements were baseline-corrected using the empty sample compartment (air).

The average transmittance (\(\:\stackrel{-}{T})\) was estimated from the Eq. (1):

where T is measured transmittance.

The average transmittance of UVC (275–200 nm), UVB (320–275 nm), UVA (400–320 nm), and visible light (600–400 nm) was estimated14.

Color variation was assessed using a Konica Minolta C544e scanner36. The CIELAB color variables—L*, a*, and b*, as defined by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE, 1965)37 —were analyzed. Here, L* represents lightness, while a* and b* denote the red/green and blue/yellow color dimensions, respectively.

Polymer coatings were applied to a white standard plate and scanned. The obtained images were processed using Online Photoshop to extract x, y, and z color coordinates, which were then converted into L*, a*, and b* values using an online calculator38.

The color difference (ΔE*) among coatings was calculated using Eq. (2), PVA resin without lignin served as the control:

Three random measurements were taken on the surface of each coating to ensure reproducibility.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a TGA/SDTA 851 METTLER TOLEDO apparatus. The thermal degradation characteristics of PVA and LNPs-containing PVA films were assessed by analyzing 5–10 mg of each sample. The measurements were conducted in a nitrogen atmosphere (50 ml/min) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min, covering temperature range from 25 °C to 800 °C.

The mechanical properties of the prepared films, tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break, were measured using a Zwick Roell Z010 testing machine (Ulm, Germany).

To evaluate the impact of lignin incorporation on the environmental stability of the films, samples (50 mm × 10 mm × 0.3 mm; five replicates per composition) were subjected to accelerated aging in an Atlas Xenotest® Alpha + chamber equipped with a xenon arc lamp and a daylight filter system to simulate natural sunlight. The exposure conditions were set to an irradiance of 60 W/m² (300–400 nm), chamber temperature of 38 °C, black standard temperature of 65 °C, relative humidity of 50%, and a total exposure time of 100 h, following ASTM G155. After aging, all samples were conditioned at 23 °C and 50% relative humidity for 24 h prior to mechanical testing to ensure consistent measurement of their mechanical performance.

Results and discussions

Properties of LNPs

To enhance the compatibility of lignin with the hydrophilic PVA matrix and improve its dispersion, acetylation was performed to reduce the hydroxyl content and increase the hydrophobicity of lignin. This modification is expected to alter the interfacial interactions within the composite system, potentially enhancing the material’s optical and mechanical properties26. The functional groups of lignins before and after acetylation were quantified using 31P NMR, and the results are presented in Table 2. The content of aliphatic hydroxyls (Aliph-OH), total phenolic hydroxyls (Ph-OHtot), condensed and non-condensed guaiacyl units (G-OH), and syringyl units (S-OH), as well as p-hydroxyl-OH in the lignin samples, were measured and calculated. Both lignins contain significantly higher amounts of Ph-OHtot in comparison to Aliph-OH. SKL, derived from softwood, is characterized by higher G-OH content, which results in a highly branched and cross-linked structure. EKL, derived from hardwood, contains a significant amount of S-OH, which results in a more linear and less cross-linked structure39. SKL also contains a higher content of p-hydroxyl-OH. As a result of the modification, over 90% of aliphatic and phenolic hydroxyl groups were consumed during acetylation.

Nanoparticles from unmodified lignin tend to form larger, more aggregated particles due to their hydrophilic nature and strong intermolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding). In contrast, acetylated lignin results in smaller, more uniform particles with improved dispersion stability, particularly in organic solvents and non-polar polymer matrices. Nanoparticles from acetylated lignin have been prepared and investigated for a range of applications40 including in antifogging coatings and structural color films41, as a possible vehicle for photosensitizing molecules42, and as a biomarker43.

The core–shell structure and well-defined spherical shape of the acetylated LNPs in this study were confirmed using TEM (Fig. 1). Minimal nanoparticle aggregation was observed, likely due to the consumption of hydroxyl groups during acetylation, which increases surface hydrophobicity and reduces hydrogen bonding. The uniform spherical structure and narrow size distribution of LNPs highlight their potential as sustainable nanofillers for the development of nanocomposite films.

Properties of nanocomposite foils

ATR/FTIR spectroscopy

To investigate the interactions between the components of the foils, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was used. Figure 2 presents the ATR-FTIR spectra of pure PVA film (Ref) and composite foils containing different amounts of LNPs from (a) spruce and (b) eucalyptus. The PVA films show a characteristic absorption band corresponding to the stretching of hydroxyl groups at 3298 cm−144. A notable blue shift was observed with increasing LNP content in the nanocomposite foils, with the hydroxyl stretching band shifting from 3298 cm⁻¹ to 3314 cm⁻¹ for spruce-derived lignin (SKL) and to 3316 cm⁻¹ for eucalyptus-derived lignin (EKL) at the highest LNP concentrations. Additionally, the peak at 1086 cm−1 corresponding to C-O stretching vibrations changed slightly with the introduction of LNPs. The blue-shift phenomenon in FTIR spectroscopy refers to a shift towards higher vibrational energy frequencies, which is usually observed in hydrogen-bonded complexes45,46.

SEM studies

SEM was used to examine the surface morphology of the tested samples at the microscopic level (Figs. 3 and 4). The reference sample exhibited the most continuous and uniform surface structure. In contrast, samples containing LNPs showed some irregularities, and more pronounced surface variations were observed in those incorporating SKL-C1 nanoparticles. These micro-scale changes may be a consequence of structural modifications occurring at the nanoscale. LNPs likely tend to agglomerate within the PVA matrix. Considering the origin of lignin, the steric arrangement of lignin molecules may influence the overall topography of the film.

AFM analysis

To better understand the effect of LNPs addition on the surface topography of the obtained films, the AFM method was used, enabling observations at the nanoscale. The obtained images provide three-dimensional information, including the surface roughness parameters of the foils. AFM images are depicted in Fig. 5. The method used allowed us to confirm the presence of lignin nanoparticles on the surface of the tested materials and to determine the change in their roughness. The arithmetic roughness (Ra) and the root-mean-squared roughness (Rq) are common parameters used to describe roughness. The reference sample is characterized by smooth surface topography with Ra = 0.411 nm and Rq= 0.522 nm. For lignin-containing representative samples, the following roughness parameters were obtained: Ra= 0.452 nm and Rq= 0.791 nm (15EKL-C1) and Ra= 0.647 nm and Rq= 1.26 nm (15SKL-C1). Therefore, concerning the reference sample, a greater increase in the Rq than in Ra parameter was observed, which might indicate the presence of spikes on the surface of the tested samples. A different arrangement of lignin nanoparticles was also observed in the case of EKL-C1 and SKL-C1. Concerning EKL-C1, they had a rounded structure, while in the case of SKL-C1, they were more slender structures. This phenomenon may be related to the structure of EKL-C1, derived from hardwood, which contains a significant number of S-units, resulting in its more linear and less cross-linked structure and, therefore, lower roughness of the obtained foil. The roughness of the foil and the arrangement of the LNPs in the PVA matrix may be crucial for its functional properties, particularly concerning UV-shielding properties.

The discrepancy between TEM (spherical, ~ 100 nm particles) and AFM (irregular shapes, increased roughness) can be attributed to nanoparticle agglomeration and deformation during the film-forming process. SKL-C1 exhibits a greater tendency to aggregate due to its branched, guaiacyl (G)-unit-rich structure, whereas EKL-C1, with a more linear, syringyl (S)-unit-rich composition, shows improved dispersion and smoother surfaces, contributing to superior UV-shielding performance. The size and morphology of agglomerates further influence UV-blocking behaviour by affecting chromophore accessibility and light scattering, with smaller, well-dispersed particles (as in EKL-C1) enhancing both UV absorption and visible light transparency.

UV-blocking performance of PVA-LNP foils

PVA–LNP composite films exhibiting superior UV-shielding performance hold significant potential for use in packaging applications17. Figure 6 presents the electronic absorption spectra of pure PVA (used as a reference) and nanocomposite foils containing lignin nanoparticles from acetylated softwood (SKL-C1) and hardwood (EKL-C1). The spectra, recorded in the 240 nm range and extending beyond the visible region, reveal clear difference depending on foil composition, primarily related to the type and concentration of LNPs used.

The solid red line in Fig. 6 corresponds to the UV-Vis spectrum of the pure PVA film, which matches Literature reports. The absorption increases with decreasing wavelength starting around 400 nm, with a pronounced peak at approximately 277 nm and an additional enhancement near 323 nm. According to the established Literature, the peak at 277 nm is attributed to the n→π* electronic transition of carbonyl groups in the polymer’s structure, while the enhancement near 330 nm corresponds to the π→π* electronic transition47.

Upon incorporation of SKL-C1 and EKL-C1 nanoparticles into polymer matrix, a clear increase in absorbance was observed. The extend of light absorption depended primarily on the type of nanoparticles used, as well as their concentration. Notably, the addition of the EKL-C1 nanoparticles resulted in higher absorbance increase compared to the corresponding additions of SKL-C1. In both cases, the adsorption bands with maxima around 275 and ~ 330 nm were significantly enhanced. This effect is attributed to the presence of lignin, whose molecular structure includes functional groups capable of both the n→π* and π→π* electronic transitions (Fig. 6). The highest levels of light absorption were, as expected, observed in samples containing the highest concentration of nanoparticles. It should be noted, however, that the most effective absorption was recorded in foil containing EKL-C1 nanoparticles. In fact, the third concentration level of the EKL-C1 already produced higher absorbance than the fourth concentration level of SKL-C1 (Fig. 6). This phenomenon, consistent with previous studies36, is attributed to the unique structural characteristics of lignin. The incorporation of lignin nanoparticles from both spruce and eucalyptus enabled the foils efficiently absorb UV light, in line with our initial assumptions.

Additionally, the spectra for both types of nanocomposites foils showed only minimal extension into the visible light region, indicating a relatively sharp boundary for photoprotective activity. Lignin inherently contains a variety of functional groups, such as hydroxy (phenolic and aliphatic), methoxy, carbonyl, and carboxy groups, which form extensive chromophoric systems capable of absorbing both UV and visible and light. In the UV range specifically, its absorption ability is primarily attributed carbonyl groups (C=O) and aromatic rings48. The extensive conjugation in lignin molecules enhances this effect, establishing lignin as an effective natural UV-blocking agent when incorporated into polymer matrices49,50. In the present study, the addition of lignin nanoparticles significantly enhanced the UV absorption capacity of the base PVA polymer, delivering improved photoprotection51.

In summary, UV-Vis spectroscopy revealed that the addition of spruce and eucalyptus Lignin nanoparticles had a significant and measurable impact on the photoprotective properties of the analyzed materials, particularly in the UV range. Compared to pure PVA, samples containing eucalyptus Lignin nanoparticles showed more than an 8-fold increase in UV Light absorption, while those with spruce Lignin nanoparticles showed an approximately 6.5-fold increase within the tested concentration range. These results highlight the strong potential of lignin nanoparticles, especially EKL-C1, as effective additives for enhancing UV protection in polymer films, supporting their applicability for commercial use in UV-sensitive packaging solutions.

Taking into consideration different regions of UV radiation, the UV-Vis transmittance spectra of PVA and PVA-LNP foils are additionally presented in Fig. 7.

Normalized transparency spectra* of PVA films without (Ref) and with varying concentrations of LNP SKL-C1 (a) and EKL-C1 (b). *T/Tmax is used to express the transmittance at each wavelength relative to the maximum transmittance, which allows for a standardized comparison of light transmission across different samples and wavelengths.

As previously mentioned, pure PVA (Ref) foil exhibited high Transmittance across the UV spectrum, indicating a lack of inherent UV-blocking properties. However, the incorporation of LNPs significantly reduced Light Transmittance, particularly in the UV region. Both EKL- and SKL-based PVA foils demonstrated notable UV protection. At 2% LNP content, the composite foils partially shielded the UVA range (400–320 nm) and effectively blocked most of the UVB (320–275 nm) and UVC (275–200 nm) regions for both types of LNPs. As the LNPs content increased, UV-shielding efficiency improved, with foils containing 15% LNP-C1 effectively blocking most UVA radiation and fully shielding the UVB and UVC spectra.

Figures 8 and 9 highlight the superior UV-shielding ability of foils containing nanoparticles from EKL-C1 compared to those containing SKL-C1. This enhancement can be attributed to the presence of syringyl units in EKL, which are rich in the methoxyl groups – functional moieties known to improve UV resistance (Table 2)39,52.

According to53, the shielding efficiency at characteristic wavelengths of 365 nm and 550 nm serves as a reliable metric for quantifying light-filtering capabilities (Figure S1). Similarly, studies54,55 have attributed the superior anti-UV performance of composite films to the oxygen-containing groups attached to aromatic rings in LNPs. Despite the light yellow coloration introduced by LNPs (Table S1), the composite foils maintained good transparency in the visible spectrum (λ > 400 nm), with Transmittance not falling below 74% for SKL-C1 and 69% for EKL-C1 (Figure S2). Variations in light absorption properties likely due to the interplay between nanoparticle concentration and dispersion, without significantly compromising optical clarity.

The degree of nanoparticle agglomeration within the PVA matrix significantly affects the UV-shielding properties of the foils. As shown by TEM and AFM analyses, EKL-C1 nanoparticles exhibit better dispersion and lower surface roughness compared to SKL-C1, which tends to form larger aggregates due to its branched, G-unit-rich structure. This improved distribution of EKL-C1 enhances chromophore accessibility and reduces light scattering losses, contributing to superior UV absorption. These findings highlight the importance of controlling nanoparticle aggregation during film formation to optimize the UV-protective performance of lignin-based PVA composites for sustainable packaging applications.

Colorimetric properties

The addition of lignin nanoparticles affected the color properties of the nanocomposites. As shown in Table 3, increasing SKL content resulted in higher yellowness (b*) and reduced whiteness (L*). Conversely, EKL-C1 series foils exhibited a trend of increasing redness (a*) with higher EKL content. These differences align with the distinct properties of SKL and EKL, as noted in prior studies56,57. Specifically, EKL LNPs are primarily composed of S/G-units and carbohydrates, whereas SKL LNPs have a lower carbohydrate content and are rich in aliphatic side chains.

Minimal changes in film color were observed with LNP addition, regardless of lignin type (Table S1). Slight trends toward increased yellowness were detected for both SKL-C1 and EKL-C1 series as nanoparticle content increased, confirming the suitability of these composites as environmentally friendly protective coatings for food packaging applications.

Figure 9 reveals a linear relationship between LNP content and color parameters: r = 0.95 for a* (SKL-C1) and r = 0.99 for b* (EKL-C1). These correlations may enable rapid monitoring of LNP content during manufacturing.

Thermal studies

Thermal resistance of the coating materials plays an important role in determining their usability. The thermal stability of the obtained foils was studied by means of thermogravimetric analysis. TG and DTG curves of the reference sample, nanocomposite foils with SKL-C1 and EKL-C1, are presented in Figs. 10 and 11. It is visible that pure PVA and LNP-containing PVA films show a similar trend of weight loss. For all the tested samples, three regions of mass loss are visible. The first stage, with the temperature of maximum thermal decomposition of 100 °C, is related to the loss of moisture or low molecular weight compounds. The second and major mass loss region is related to the structural degradation of PVA, mainly involving the dehydration of hydroxyl groups and the formation of volatile organic compounds and conjugated, unsaturated polyenes. In the third mass loss region (starting at around 395 °C in this study, with a maximum degradation rate at about 430 °C), polyene residues degrade into alkenes and alkanes, as well as aromatics through intramolecular cyclization58,59,60,61. The introduction of LNPs (especially EKL-C1) slightly influences the temperature with the fastest degradation rate (Tmax). Lignin addition can be beneficial due to its charring ability and therefore increasing fire resistance of polymer coating materials. Additionally, good thermal stability as well as hydrogen bonding between LNPs and PVA that can restrict the free movement of PVA chain segments62 characterize the presence of aromatic structural units in LNP molecules.

Mechanism of UV blocking

The UV-blocking mechanism of PVA-LNP foils primarily relies on absorption rather than reflection or scattering, as supported by experimental data and previous studies45. LNPs absorb ultraviolet photons, converting their energy into heat through hydrophilic chromophores such as methoxy, phenolic hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups present on the nanoparticle surface50. The generated heat is gradually dissipated from the nanocomposite films without degrading the PVA matrix.

A slight increase in light transmittance at the UVC spectrum (Fig. 8) suggests that UV blocking is not influenced by particle size (e.g., via reflection), as acetylated SKL and EKL nanoparticles have similar size and shape (Fig. 1). Instead, the chromophoric groups within lignin molecules are likely responsible for UV absorption, as indicated by the correlation between increased yellowness (b*) and reduced UV transmittance (Figs. 8 and 9).

According to RGB color theory, yellow and blue light combine to produce white light when their intensities are balanced63,64,65. In this context, lignin nanoparticles function as yellow pigments, selectively absorbing blue light and regulating high-energy visible light transmission. As a result, the nanocomposite films remain opaque to UV light (λ < 400 nm) while maintaining high transparency in the visible spectrum (λ = 400–600 nm).

Mechanical properties

Since the foils proposed in this study are intended for use as food packaging, it is essential to assess their mechanical strength to verify their ability to withstand the stresses and loads that arise from environmental factors and packaged products. The mechanical properties of foils enriched with lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) derived from spruce (SKL-C1) and eucalyptus (EKL-C1) at various concentrations were compared with those of the reference PVA foil (without nanoparticles). The results are summarized in Fig. 12a and b as well as in Table S2.

The incorporation of lignin nanoparticles, regardless of their source, had only a limited impact on the elongation at break of the foils. For SKL-C1 containing foils, increasing the Lignin content from 2 to 15 wt% resulted in a nearly Linear decrease in elongation, ranging from approximately 9% to 17%. In contrast, EKL-C1 containing foils exhibited a non-linear trend: elongation increased at intermediate concentrations and reached a maximum at 10 wt%, exceeding the value of the reference sample by 4%. These differences suggest distinct interactions between the two types of lignin nanoparticles and the PVA matrix.

The Young’s modulus of the foils fluctuated within the range of − 21% to + 21% for SKL-C1 and − 26% to + 64% for EKL-C1 relative to the reference film. These variations may reflect uneven dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix. Nevertheless, the overall trend toward increased modulus, particularly pronounced for EKL-C1, suggests that LNP incorporation generally enhances the stiffness of the polymer, implying a reduced flexibility with higher lignin content.

A gradual decline in tensile strength was observed with increasing nanoparticle content in both SKL- and EKL-based foils. This trend is consistent with previous findings66 and may be attributed to structural irregularities caused by LNP agglomeration. Despite this reduction, all measured values remained within the acceptable range for food packaging applications.

Ultraviolet (UV) irradiation is a well-known cause of photochemical damage and degradation in both food products and packaging materials. Packaging with UV-protective properties can help maintain food quality, enhance safety, and extend shelf life. Lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) are established UV-absorbing fillers, and their incorporation into PVA foils in this study aimed to enhance UV resistance. However, UV exposure can also lead to degradation of the polymer itself67. To assess the durability of the developed foils, mechanical properties were evaluated before and after UV exposure.

As shown in Fig. 12b, all tested parameters, tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break, decreased following UV in all samples. This outcome is consistent with UV-induced polymer degradation. Nonetheless, the LNP-containing foils demonstrated greater resistance to UV-related deterioration compared to the reference PVA film, highlighting the protective role of lignin nanoparticles68.

Further insights were gained from SEM micrographs of representative foils (PVA, 15SKL-C1, and 15EKL-C1) before and after UV exposure (Fig. 13). The reference foil exhibited a higher number and larger size of cracks following irradiation. In contrast, the SKL-C1- and EKL-C1-containing foils showed significantly fewer cracks, indicating that both types of LNPs contribute to enhanced durability and reduced photodegradation. Notably, SKL-C1 foils displayed more pronounced cracking than EKL-C1 foils, suggesting that EKL nanoparticles offer superior reinforcement, likely due to their better dispersion (TEM, Fig. 1b) and smoother surface morphology (Ra = 0.452 nm, Fig. 5).

Taken together, these findings confirm the potential of PVA–LNP composite films, particularly those containing EKL-C1, for use in flexible food packaging applications. Their balanced mechanical properties, combined with improved UV stability, highlights their suitability for protecting food products while maintaining structural integrity during storage and handling.

Barrier properties of PVA and LNP-enhanced PVA foils

An essential criterion in the selection of food packaging systems is their barrier performance, which determines the material’s ability to resist the transmission of gases (O₂, CO₂, and N₂), water vapor, light, and aroma compounds. These barrier properties are critical for maintaining the quality, safety, and shelf life of packaged products by preventing spoilage, contamination, and degradation. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) is well known for its excellent gas barrier properties, chemical resistance, and favorable optical and physical characteristics, highliting its strong potential as a biodegradable high-barrier coating for food packaging films69. However, PVA’s high sensitivity to moisture can significantly compromise its barrier performance, particularly under conditions of elevated humidity or in applications involving fresh foods70.

To address this limitation, kraft lignins have emerged as promising additives due to their intrinsic hydrophobic properties, which can reduce the water sensitivity of PVA films and improve their water vapor permeability (WVP), as supported by several studies32,71. Barrier parameters such as WVP and oxygen permeability (OP) are critical metrics, as they define the material’s ability to protect contents from external environmental factors. Previous studies have reported that the WVP of neat PVA films ranges from (9.9 × 10⁻⁴ to 4.9 × 10⁻⁴ g mm⁻¹ day⁻¹ atm⁻¹)72, while the OP of pure PVA has been measured at 0.12 ± 0.04 cm² m⁻² atm⁻¹ day⁻¹ MPa73.

The incorporation of lignin nanoparticles (LNPs), particularly acetylated types such as SKL-C1 and EKL-C1, is expected to improve water vapor barrier properties by reducing the hydrophilicity of the composite film. For example, Zhang et al. (2020)32 demonstrated that incorporating 5 wt% lignin into PVA reduced the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) by approximately 189% compared with neat PVA. Similarly, Yang et al. (2024)74 reported that pure PVA films exhibited a WVTR of 6.9 g∙m⁻²∙h⁻¹ and a WVP of 3.24 × 10⁻⁷ g∙m m⁻² Pa h⁻¹ The addition of lignin nanoparticles led to a moderate reduction in WVTR. However, they also observed that excessive LNP content could lead to particle aggregation, disrupting uniform dispersion within the matrix and slightly increasing WVP values due to reduced densification and water retention capacity.

The source of lignin also plays a crucial role in determining barrier improvements. According to Lin et al.39, hardwood lignins (e.g., EKL) generally deliver superior barrier properties compared to softwood lignins (e.g., SKL) due to their more linear molecular structure and higher methoxyl group content, which further decreases water affinity. In addition to improving water vapor resistance, lignin nanoparticles enhance oxygen barrier properties by creating tortuous diffusion pathways and reinforcing the polymer matrix through hydrogen bonding. Phansamarng et al. (2024)75 confirmed that increasing lignin loading in films consistently reduced oxygen permeability, thereby strengthening their protective function against oxidative degradation in packaged foods.

Collectively, literature findings underscore that lignin nanoparticles, particularly those derived from hardwood-derived sources such as EKL-C1, significantly enhance the barrier performance of PVA-based films by reducing both WVP and OP. These results align with the present study, confirming the potential of acetylated SKL-C1 and EKL-C1 nanoparticles to improve the barrier properties of PVA foils and support the development of sustainable, high-performance food packaging materials.

Summary of key findings

A detailed comparison of PVA foils containing lignin nanoparticles from spruce (SKL-C1) and eucalyptus (EKL-C1) is presented in Table 4. EKL-C1-based foils consistently outperformed SKL-C1 foils in UV-shielding efficiency, surface smoothness (AFM), and nanoparticle dispersion (TEM). Both types of lignin underwent extensive acetylation (> 90% hydroxyl group conversion), but EKL-C1 showed slightly lower residual hydroxyl content, indicating a marginally higher degree of acetylation.

These differences likely contributed to the improved compatibility of EKL-C1 nanoparticles with the hydrophilic PVA matrix, resulting in less agglomeration and more homogeneous dispersion in the films. Additionally, the syringyl-rich structure of EKL, with its higher methoxyl group content, is known to enhance UV absorption. These combined factors explain the superior UV-blocking and structural properties observed for EKL-C1-based foils.

Colorimetric and mechanical tests further confirmed that both SKL-C1 and EKL-C1 composites retained high transparency and flexibility, with EKL-C1 films showing slightly greater resistance to UV-induced degradation. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of acetylated hardwood-derived lignin nanoparticles as effective functional additives for biodegradable, light-protective packaging materials.

Overall, the comparative evaluation demonstrates the superior performance of EKL-C1-based foils in terms of UV protection, nanoparticle dispersion, and structural integrity. These results confirm the potential of acetylated LNPs, particularly those derived from eucalyptus, as effective functional additives for sustainable, biodegradable packaging.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful development of UV-protective, transparent, and biodegradable PVA foils using acetylated lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) derived from spruce and eucalyptus. The incorporation of LNPs significantly enhanced the UV-shielding performance of PVA, with eucalyptus-derived EKL-C1 nanoparticles showing superior results due to their higher methoxyl content and more uniform dispersion in the polymer matrix.

Comprehensive characterization, including UV-Vis spectroscopy, AFM, TEM, and FTIR, confirmed that both lignin source and nanoparticle distribution play key roles in determining foil performance. EKL-C1-based films achieved stronger UV-blocking, smoother surfaces, and improved structural stability compared to SKL-C1. Mechanical and aging tests further underscored the effectiveness of LNPs in enhancing durability.

These findings highlight the potential of lignin nanoparticles, particularly from hardwood sources, as sustainable, high-performance additives for advanced packaging materials. The improved mechanical stability after UV exposure makes these composites promising candidates for protecting light-sensitive products, while also supporting lignin valorization and circular material strategies. Although barrier properties were not directly measured in this study, previous research suggests that well-dispersed lignin nanoparticles may also contribute to enhanced barrier performance in similar polymer systems.

Future research could focus on scaling up production, evaluating long-term UV stability, and exploring other applications for lignin-based nanocomposites. Tailoring lignin modification strategies and assessing alternative lignin sources may further enhance material performance and extend their potential in sustainable packaging and related fields.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ghosh, K. & Jones, B. H. Roadmap to biodegradable plastics—current state and research needs. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 6170–6187. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00801 (2021).

e-resource 1. Water-soluble Packaging Market: A detailed analysis of the Water-soluble Packaging Market by Polymers, Surfactants, and Fibers. https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/water-soluble-packaging-market

Ramaraj, B. Crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) and starch composite films. II. Physicomechanical, thermal properties and swelling studies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 103, 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.25237 (2007).

Chiellini, E., Corti, A., D’Antone, S. & Solaro, R. Biodegradation of Poly (vinyl alcohol) based materials. Prog Polym. Sci. 28 (6), 963–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6700(02)00149-1 (2003).

Li, Y., Li, S. & Sun, J. Degradable poly(vinyl alcohol)-based supramolecular plastics with high mechanical strength in a watery environment. Adv. Mater. 33, e2007371. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202007371 (2021).

Haghighi, H. et al. Characterization of Bionanocomposite films based on gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol blend reinforced with bacterial cellulose nanowhiskers for food packaging applications. Food Hydrocoll. 113, 106454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106454 (2021).

Oun, A. A., Shin, G. H., Rhim, J. W. & Kim, J. T. Recent advances in Polyvinyl alcohol-based composite films and their application in food packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 34, 100991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100991 (2022).

Julinová, M. et al. Lignin and starch as potential inductors for biodegradation of films based on poly(vinyl alcohol) and protein hydrolysate. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 95 (2), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2009.10.008 (2010).

Northey, R. A., Glasser, W. G. & Schultz, T. P. (eds) Lignin: historical, biological, and materials perspectiVes; ACS Symposium Series 742; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, (2000).

Dessbesell, L., Paleologou, M., Leitch, M., Pulkki, R. & Xu, C. Global lignin supply overview and kraft lignin potential as an alternative for petroleum-based polymers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 123, 109768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.109768 (2020).

Zheng, L. et al. Understanding the relationship between the structural properties of lignin and their biological activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 190, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.168 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Facile fabrication of transparent lignin sphere/pva nanocomposite films with excellent UV-Shielding and high strength performance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 189, 635–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.167 (2021).

Li, X., Liu, Y., Ren, X., Transparent & Ultra-Tough, P. V. A. Alkaline lignin films with UV shielding and antibacterial functions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 216, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.188 (2022).

Zhang, X., Liu, W., Yang, D. & Qiu, X. B. Supertough and strong biodegradable polymeric materials with improved thermal properties and excellent UV-Blocking performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.188 (2019).

Korbag, I. & Saleh, M. Studies on the formation of intermolecular interactions and structural characterization of Polyvinyl alcohol/lignin film. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 73, 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2016.1143700 (2016).

Nizamov, R. et al. Optical assessment of lignin-containing nanocellulose films under extended sunlight exposure. Cellulose https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-025-06380-7 (2025).

Yang, W., Ding, H., Qi, G. & Ma, P. Highly transparent pva/nanolignin composite films with excellent UV shielding, antibacterial and antioxidant performance. React. Funct. Polym. 162 (5), 104873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.104873 (2021).

Tran, M. H., Phana, D. P. & Lee, E. Y. Review on lignin modifications toward natural UV protection ingredient for lignin-based sunscreens. Green. Chem. 23, 4633–4646. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1GC01139A (2021).

Lv, S. et al. Lignin-based anti-UV functional materials: recent advances in Preparation and application. Iran. Polym. J. 32, 1477–1497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13726-023-01218-0 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Lignin-containing biodegradable UV-blocking films: a review. Green. Chem. 25, 9020–9044. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3GC02908E (2023).

Ko, H. U. et al. Poly(vinyl alcohol)-lignin blended resin for cellulose-based composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 135, 46655. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.46655 (2018).

Ratnawati, R., Wulandari, R. & Istiqomah, A. Biodegradable plastics from pva/starch/lignin blend: mechanical properties, water absorption, and biodegradability. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 24 (4), 224–231 (2023).

Ramadhan, M. H., Nurrahman, A., Steven, S. & Mardiyati, Y. Enhancing mechanical properties, degradation rate, and water resistance of bioplastic lignin/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) by fractionation of lignin. Emergent Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42247-024-00805-y (2024).

Abdullah, Z. W., Dong, Y., Davies, I. J. & Barbhuiya, S. P. V. A. PVA blends, and their nanocomposites for biodegradable packaging application. Polym. -Plast Technol. Eng. 56, 1307–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/03602559.2016.1275684 (2017).

Kubo, S. & Kadla, J. F. The formation of strong intermolecular interactions in immiscible blends of Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) and Lignin. Biomacromolecules 4 (3), 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm025727p (2003).

Gordobil, O., Delucis, R., Egüés, I. & Labidi, J. Kraft lignin as filler in PLA to improve ductility and thermal properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 72, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.01.055 (2015).

Gordobil, O., Egüés, I., Llano-Ponte, R. & Labidi, J. Physicochemical properties of PLA lignin blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 108, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.01.002 (2014).

Ewulonu, C. M., Liu, X. R., Wu, M. & Huang, Y. Ultrasound-assisted mild sulphuric acid ball milling Preparation of lignocellulose nanofibers (LCNFs) from sunflower stalks (SFS). Cellulose 26, 4371–4389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02382-4 (2019).

Yang, M. et al. Green Preparation of lignin nanoparticles in an aqueous hydrotropic solution and application in biobased nanocomposite films. Holzforschung 75 (5), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2020-0021 (2021).

Beaucamp, A., Wang, Y., Culebras, M. & Collins, M. N. Carbon fibres from renewable resources: the role of the lignin molecular structure in its blendability Wiot Hbiobased poly(ethyleneterephthalate). Green. Chem. 21, 5063–5072. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9GC02041A (2019).

Xiong, F., Wu, Y., Li, G., Han, Y. & Chu, F. Transparent nanocomposite films of lignin nanospheres and poly(vinyl alcohol) for UV-absorbing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.7b04108 (2018).

Zhang, X., Liu, W., Liu, W. & Qiu, X. High performance pva/lignin nanocomposite films with excellent water vapor barrier and UV-Shielding properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 142, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.129 (2020).

Pylypchuk, I. V., Riazanova, A., Lindström, M. E. & Sevastyanova, O. Structural and molecular-weight-dependency in the formation of lignin nanoparticles from fractionated soft- and hardwood lignins. Green. Chem. 23, 3061–3072. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0GC04058D (2021).

Granata, A. & Argyropoulos, D. S. 2-Chloro-4,4,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,3,2-Dioxaphospholane, a reagent for the accurate determination of the uncondensed and condensed phenolic moieties in lignins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43, 1538–1544. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00054a023 (1995).

Argyropoulos, D. S. Quantitative Phosphorus-31 NMR analysis of lignins, a new tool for the lignin chemist. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 14 (1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773819408003085 (1994).

Goliszek, M., Podkościelna, B., Smyk, N. & Sevastyanova, O. Towards lignin valorization: lignin as a UV-protective bio-additive for polymer coatings. Pure Appl. Chem. 95 (5), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2022-1209 (2023).

e-resource 2. Method of measuring and specifying colour rendering properties of light sources | CIE https://cie.co.at/publications/method-measuring-and-specifying-colour-rendering-properties-light-sources (1965).

e-resource 3. https://cielab.xyz/colorconv

Lin, M. et al. Revealing the structure-activity relationship between lignin and anti-UV radiation. Ind Crops Prod 174, 114212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114212 (2021).

Qian, Y., Deng, Y., Qiu, X., Lia, H. & Yang, D. Formation of uniform colloidal spheres from lignin, a renewable resource recovered from pulping spent liquor. Green. Chem. 16, 2156–2163. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3GC42131G (2014).

Henn, K. A. et al. Transparent lignin nanoparticles for superhydrophilic antifogging coatings and photonic films. J. Chem. Eng. 475, 145965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.145965 (2023).

Marchand, G., Fabre, G., Maldonado-Carmona, N., Villandierc, N. & Leroy-Lhez, S. Acetylated lignin nanoparticles as a possible vehicle for photosensitizing molecules. Nanoscale Adv. 2, 5648–5658. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NA00615G (2020).

Robbins, E. et al. Porphyrin-loaded acetylated lignin nanoparticles as a remarkable biomarker emitting in the first optical window. J. Porphyr. Phthalocya. 26 (08n09), 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1088424622500377 (2022).

Zheng, Q., Osei, P. O., Shi, S., Yang, S. & Wu, X. Green fabrication of nanocomposite films using lignin nanoparticles and PVA: characterization and application. Food Biosci. 59, 104022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104022 (2024).

Zierkiewicz, W., Czarnik-Matusewicz, B. & Michalska, D. B. Shifts and unusual intensity changes in the infrared spectra of the enflurane···acetone complexes: spectroscopic and theoretical studies. J. Phys. Chem. A. 115 (41), 11362–11368. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp205081r (2011).

Oliveira, B. G., de Araújo, R. C. M. U. & Ramos, M. N. A theoretical study of blue-shifting hydrogen bonds in π weakly bound complexes. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 908 (1–3), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theochem.2009.05.013 (2009).

Shehap, A. M. Thermal and spectroscopic studies of Polyvinyl alcohol/sodium carboxy Methyl cellulose blends. Egypt. J. Solids. 31 (1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.21608/EJS.2008.148824 (2008).

Arias-Ferreiro, G. et al. Lignin as a High-Value Bioaditive in 3D-DLP Printable Acrylic Resins and Polyaniline Conductive Composite. Polymers 14, 4164. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194164

Sirviö, J. A. & Visanko, M. Highly transparent nanocomposites based on Poly(vinyl alcohol) and Sulfated UV-Absorbing Wood Nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 20 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00427 (2019). 2413 – 2420.

Tian, D. et al. Lignin valorization: lignin nanoparticles as High-Value Bio-Additive for multifunctional nanocomposites. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 10, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0876-z (2017).

Skulcova, A. et al. UV/Vis spectrometry as a quantification tool for lignin solubilized in deep eutectic solvents. BioRes 12 (3), 6713–6722. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.12.3.6713-6722 (2017).

Liang, T. et al. New insights into greener skin healthcare protection: lignin nanoparticles as additives to develop natural-based sunscreens with high UV protection. Carbon Resour. Convers. 7 (4), 100227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crcon.2024.100227 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. High strength and multifunctional polyurethane film incorporated with lignin nanoparticles. Ind. Crops Prod. 177, 114526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114526 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Zhang, J. Protection materials: ultraviolet shielding, high energy visible light filtering and visible light transparency PETG composite films. Plast. Rubber Compos. 44 (9), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743289815Y.0000000032 (2015).

Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Xie, M., Lu, F. & Yue, F. U. V. Resistance properties of lignin influenced by its Oxygen-Containing groups linked to aromatic rings. Biomacromolecules 26 (1), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.4c01246 (2024).

Goliszek-Chabros, M., Xu, T., Bocho-Janiszewska, A., Podkościelna, B. & Sevastyanova, O. Lignin nanoparticles from softwood and hardwood as sustainable additives for broad-spectrum protection and enhanced sunscreen performance. Wood Sci. Technol. 59 (60). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-025-01659-1 (2025).

Pylypchuk, I. V. et al. High-Molecular-Weight fractions of Spruce and Eucalyptus lignin as a perspective Nanoparticle-Based platform for a therapy delivery in liver cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 817768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.817768 (2022).

Rowe, A. A., Tajvidi, M. & Gardner, D. J. Thermal stability of cellulose nanomaterials and their composites with Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 126, 1371–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-016-5791-1 (2016).

Magalhaes, M. S., Toledo, R. D. & Fairbairn, E. M. R. Durability under thermal loads of Polyvinyl alcohol fibers. Materia-Rio De Janeiro. 18 (4), 1587–1595 (2013).

Lu, J., Wang, T. & Drzal, L. T. Preparation and properties of microfibrillated cellulose Polyvinyl alcohol composite materials. Compos. Part. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 39 (5), 738–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2008.02.003 (2008).

Sin, L. T., Rahman, W., Rahmat, A. R. & Mokhtar, M. Determination of thermal stability and activation energy of Polyvinyl alcohol-cassava starch blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 83 (1), 303–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.07.049 (2011).

Cao, X. S., Lin, X. L., Li, B. Y., Wu, R. C. & Zhong, L. Interpretation of the phenolation and structural changes of lignin in a novel ternary deep eutectic solvent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 264, 130475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130475 (2024).

Ford, A. & Roberts, A. Colour space conversions. Technical report, Westminster University, London, August (1998).

Ibraheem, N. A., Hasan, M. M., Khan, R. Z. & Mishra, P. K. Understanding color models: A review. ARPN J. Sci. Technol. 2 (3), 2225–7217 (2012).

Stiles, W. S. & Wyszecki, G. Color Science Concepts and Methods, Quantitative Data and Formulae. Wiley Classics Library (John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2000).

Shah, Y. A. et al. Mechanical properties of Protein-Based food packaging materials. Polym. (Basel). 15 (7), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15071724 (2023).

Feng, H., Wang, W. & Miao, P. Influence of ultraviolet irradiation on the physical and mechanical properties of strain-hardening cement-based composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04895 (2025).

Jiang, T., Qi, Y. & Zhang, W. Y. J. Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation. e-Polymers 19, 499–510 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly-2019-0053

Espinosa, E. et al. PVA/(ligno)nanocellulose biocomposite films. Effect of residual lignin content on structural, mechanical, barrier and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 141, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.262 (2019).

Barbato, A. et al. Biodegradable films with Polyvinyl alcohol/polylactic Acid + Wax double coatings: influence of relative humidity on transport properties and suitability for modified atmosphere packaging applications. Polymers 15 (19), 4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15194002 (2023).

Yang, W., Qi, G., Kenny, J. M., Puglia, D. & Ma, P. Effect of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Lignin Nanoparticles on Mechanical, Antioxidant and Water Vapour Barrier Properties of Glutaraldehyde Crosslinked PVA Films. Polymers 12, 1364. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061364

Mohammad Mahdi Dadfar, S., Kavoosi, G. & Mohammad Ali Dadfar, S. Investigation of mechanical properties, antibacterial features, and water vapor permeability of Polyvinyl alcohol thin films reinforced by glutaraldehyde and multiwalled carbon nanotube. Polym. Compos. 35 (9), 1736–1743. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.22827 (2014).

Ding, J., Zhang, R., Ahmed, S., Liu, Y. & Qin, W. Effect of sonication duration in the performance of Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan bilayer films and their effect on strawberry preservation. Molecules 24, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24071408 (2019).

Yang, H. et al. Excellent facile fabrication of PVA and lignin nanoparticles from wheat straw after novel DES-THF pretreatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecul. 281 (2), 136238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136238 (2024).

Phansamarng, P., Bacchus, A., Pour, F. H., Kongvarhodom, C. & Fatehi, P. Cationic lignin incorporated Polyvinyl alcohol films for packaging applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 221, 119217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119217 (2024).

Acknowledgements

M.G-Ch. acknowledges support from the WIRE COST Action (CA20127), funded by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, www.cost.eu).O.S. and T.X. acknowledge funding from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW) through the Wallenberg Wood Science Center (WWSC 3.0: KAW 2021.0313).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing, Visualization; N.S.: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing- Review & Editing, Visualization; T.X.: Investigation; A.M.: Investigation, Formal Analysis; B.P.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration; O.S.: Resources, Writing- Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration;

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goliszek-Chabros, M., Smyk, N., Xu, T. et al. Lignin nanoparticle-enhanced PVA foils for UVB/UVC protection. Sci Rep 15, 35735 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19753-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19753-6