Abstract

This study investigates the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the polyline-shaped large-span double-layer grid space structures subjected to progressive collapse. A grid model was designed and fabricated to represent a typical area of a large-span double-layer grid space structure from a specific engineering project. Three representative locations were selected to simulate failure of the test model, and dynamic collapse tests were conducted. In the tests, four conditions were considered: D1 (120 kg, failure at A), D2 (120 kg, failure at B), D3 (120 kg, failure at C), and D4 (200 kg, failure at C). The dynamic response of the structure under various conditions was studied by comparing strain, displacement, and failure patterns derived from the test analysis. Furthermore, the collapse process and mechanism of the structure were analyzed. The results indicate that the upper chord rods are key components in collapse resistance design. Under test conditions D4, significant vertical displacement occurred, and out-of-plane deformation increased markedly after the lateral constraints were removed, causing the structure to tilt towards the side without a failure device. The strain and displacement changes were most significant under test conditions D3 and D4, especially near the failure locations. Under condition D3, the strain change is 1109 microstrain larger than that before the failure, with the maximum vertical displacement increase being 59.109 mm. Under condition D4, the strain change is -1126 microstrain larger than that before the failure, with the maximum vertical displacement increase being 74.795 mm. Through multi-condition testing, the collapse mechanisms at different failure locations in the structure were clarified. The failure of web members and lower chord rods led to a redistribution of internal forces, but the effect on the double-layer grid structure was minimal. After the failure of the upper chord rods, significant displacements occurred near the failure location, and buckling of surrounding members was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-span space structures, with their advantages of wide coverage and large spatial volume, are well-suited to meet the growing demands of engineering applications driven by current socio-economic development. As a result, they have been widely used in the construction of various buildings, such as sports venues, airport terminals, train stations, and industrial factories. However, when subjected to accidental or extreme loads, these structures may experience progressive collapse, which can lead to significant damage and losses1. For example, in 2009, the Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin Stadium in Malaysia, which cost 270 million Malaysian ringgit and had been open for only one year, experienced a roof collapse, resulting in significant economic losses. In 2011, during the expansion of the De Grolsch Veste FC Twente stadium in the Netherlands, a roof collapse occurred, leading to the deaths of two individuals2. In recent years, the summary articles on the research results of building resistance to progressive collapse3,4,5,6,7 found that they mainly focused on the progress of research on the collapse resistance of frame structures, and scholars have carried out many researches on the resistance to progressive collapse of frame structures8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Additionally, Adam et al.1 have pointed out in their work that while much of the current research is concentrated on frame structures, there is relatively less research dedicated to large-span space structures. Therefore, conducting research on the progressive collapse resistance of large-span space structures is of significant importance.

Grid structures, as a class of large-span spatial frameworks, can be categorized into single-layer and multi-layer grid space structures based on their configuration. Progressive collapse resistance of grid structures has been extensively studied15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. For the single-layer grid structure, Tian et al.15 conducted experimental and numerical analyses on the collapse resistance of the structures and studied their collapse mechanisms. Subsequently, they explored methods to enhance the progressive collapse resistance of single-layer space grids, proposing various strengthening techniques to improve their collapse performance16,17. They also developed a method for evaluating the collapse resistance of single-layer grid space structures18.

Research on multi-layer grid space structures has primarily concentrated on double-layer grid space systems25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. For instance, Sheidaii et al.25 analyzed the sensitivity of double-layer grid space structures to initial defects and their impact on collapse behavior. Fu et al.26 investigated the importance of components in a double-layer grid space structure, studying whether progressive collapse occurs when certain components fail or supporting columns collapse. They proposed an effective method for mitigating progressive collapse by reinforcing the grid lines and connecting the support pairs across the structure. Chen et al.27,28, focusing on the demolition of double-layer grid space structures, conducted studies where key load-bearing components were removed one by one to measure the overall structural response. They investigated the redistribution of internal forces under different demolition load conditions and proposed a progressive collapse demolition method. Liu et al.29,30 proposed an innovative double-layer grid space structure in which the cables and supports are connected in series along the lower chord. Through experimental and finite element analyses, they found that this new design significantly enhanced the collapse resistance of the double-layer grid structure.

In double-layer grid space structures, there are three main system types: the crossed truss system, the four-pyramid system, and the triangular pyramid system37. Of these systems, the four-pyramid configuration has been extensively studied owing to its attributes, including uniform internal force distribution within the members, standardized roof panel specifications, and straightforward construction processes. Consequently, the majority of studies on progressive collapse resistance have concentrated on this system. However, a review of the existing literature indicates that research has predominantly focused on regular four-pyramid grid structures, with limited attention given to large-span double-layer grid structures specifically tailored to meet distinct design and functional requirements, which is often represented in the structural form of a polyline-shaped grid structure.

Furthermore, existing studies predominantly employ finite element analysis and numerical simulation as the principal theoretical methods for investigating collapse behavior. Conversely, experimental research has largely concentrated on simulating component failure under static loading conditions, while investigations into dynamic collapse behavior remain relatively scarce.

To overcome the limitations in existing research on the progressive collapse resistance of double-layer grid space structures, this study focuses on a real-world double-layer grid space structure as its basis. A representative grid model was meticulously designed and constructed to replicate collapse behavior. Failure scenarios were simulated at three representative locations of the test model, followed by comprehensive dynamic collapse tests. Through comparative analysis of strain, displacement, and failure modes derived from experimental results, this study examines the dynamic response of the structure under varying loading conditions and elucidates the collapse process and underlying mechanisms.

Experimental overview

Structure overview

The double-layer grid space structure is predominantly composed of three distinct member types: upper chord rods, web members, and lower chord rods. In contemporary studies on the progressive collapse resistance of standard double-layer grid space structures, the most extensively examined systems are those constructed using four-pyramid grids, characterized by uniform specifications and a regular, unvarying layout. In these structures, the upper and lower chord rods are arranged neatly within their respective planes, with uniform dimensions, and the web members have consistent lengths and arrangements. A schematic diagram of such a structure is shown in Fig. 1.

The polyline-shaped double-layer grid space structure studied in this paper is also composed of the three types of members: upper chord rods, web members, and lower chord rods. However, to meet specific design requirements, the lengths of the upper and lower chord rods are not entirely uniform within their respective planes, and the grid formed by the upper chord rods does not follow a completely uniform pattern. The lengths and arrangement of the web members are also not fully consistent. A schematic diagram of this polyline-shaped structure is shown in Fig. 2.

Model design

In the actual engineering project, this substructure represents the typical arrangement of most single frames. Considering the scale ratio and the constraints of the experimental site, a single-frame substructure was selected for testing to investigate its collapse performance. In this study, a scaled-down physical model test was conducted to investigate the progressive collapse resistance of the structure under loading. The prototype-to-model similarity was established based on the principles of similitude theory. A geometric similarity ratio of 1:10 was adopted, which determined the dimensions of the scaled model. All steel tube sections adopted a dimension of \(\Phi\)15.0 mm×1.0 mm. The selected layout of the single-frame model is representative of a typical area within the project, as shown in Fig. 3.

The study focuses on this large-span double-layer grid space structure. Based on the grid layout pattern, an experimental model of a polyline-shaped double-layer grid space structure with a span of 4.0 m was fabricated. All steel tubes in the model are made of No. 20 seamless steel pipes38, and the material for the welded ball joints is Q235B steel. The cross-sectional dimensions of the upper and lower chord rods and web members are Φ15.0 mm × 1.0 mm. The model dimensions are shown in Fig. 4.

The actual welded hollow ball specifications include a diameter of 40 mm, a wall thickness of 2.0 mm, and a total of 32 balls. The connection form and specific dimensions of the welded hollow ball are shown in Fig. 5.

The statistics of the cross-sectional dimensions and the number of each rod in the model are shown in Table 1.

Material property tests were conducted on the members. The loading and measurement methods followed the GB/T 228.1–2021 standard, “Tensile Testing of Metallic Materials—Part 1: Test Methods at Room Temperature”39. The material performance test and stress-strain curves are shown in Fig. 6. The test results are shown in Table 2.

Failure device

Accurately simulating the instantaneous failure of critical components is a key factor determining the success or failure of the experiment. After an extensive investigation into current methods for simulating the instantaneous failure of critical components in grid structure experiments, it was found that techniques such as jack loading/unloading or rod cutting are commonly employed. However, these methods introduce additional disturbances to the large-span grid structure during the simulation process. Based on a review of the relevant literature, the instantaneous failure device adopted for this experiment is shown in Fig. 740.

The effectiveness of this device was validated. When the clamping device is used to lock the two segments of the steel head, the forces at that moment are shown in Fig. 8.

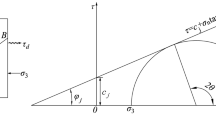

In the entire force diagram, three different internal forces are involved: the axial force F1transmitted through the rod, the clamping force F2 provided by the clamping device, and the reaction force F3 generated between the serrated contact surfaces of the steel head due to the interaction of the two internal forces. The equilibrium equations are shown in Eq. (1) and Eq. (2).

As mentioned above, when the three forces are in equilibrium, the rod can effectively transmit internal forces. When the clamping device is released, the provided clamping force F2 disappears, causing the load transfer equilibrium system of the initial failure device to fail. The serrated steel heads shift relative to each other, resulting in the instantaneous failure of the rod. Therefore, the opening and closing of this device can effectively simulate both the normal operation and instantaneous failure of the rod.

From the above analysis, the key to this experiment lies in whether the clamping device can achieve instantaneous failure. Two different types of clamping devices were used in this experiment: hose clamps and self-locking pliers, as shown in Fig. 9. If no test is conducted at the selected location, the hose clamp is used for clamping. If a test is conducted, the self-locking pliers are used for clamping. The use of the two different clamping devices during the experiment is shown in Fig. 10.

The nut at the rear end of the handheld handle can adjust the clamping opening, thereby controlling the clamping force, while the black handle functions as a quick-release switch. During the test, the member intended to simulate instantaneous failure was clamped using the self-locking pliers, whereas members not subjected to instantaneous failure were clamped with hose clamps to ensure normal load transfer. When the handheld handle is fully closed, the self-locking pliers grip the serrated steel head and form a self-locking mechanism. Activating the black handle allows the plier to release rapidly, thereby achieving instantaneous failure of the target member.

Failure location selection

All the members are divided into the upper chord group, the web member group, and the lower chord group according to their positions. The finite element static load-bearing analysis is carried out on a single large-span polygonal quadrangular pyramid grid, and the resulting stress contour plot is shown in Fig. 11. According to the magnitude of stress and displacement, it is found that the upper chord and lower chord in the middle part are important members in the respective groups. At the same time, in order to understand the influence of the failure of the side members on the structure, the members near the support are selected as the important members in the web member group. The initial failure introduction device is arranged on the important members of each group. At the same time, in order to achieve the effect of the comparative test, the same part is selected to introduce the initial failure device, which is distributed as shown in Fig. 12.

Test conditions and loading scheme

Based on preliminary calculations, four different test conditions were designed for this experiment, including three dynamic response tests in the elastic stage and one dynamic response test under failure loading. In the finite element analysis, the dynamic response of the structure under lower chord failure was investigated while remaining within the elastic stage. Accordingly, in the experimental design, the applied load was controlled to ensure that the structure stayed in the elastic stage when the lower chord failed. The dynamic response tests in the elastic stage involve applying an appropriate load to the test model. Once the structure reaches a uniform and stable stress, the initial failure introduction device is triggered, and the dynamic responses at the test measurement points are recorded. The dynamic response test under failure loading is conducted after the elastic stage tests. A brief analysis of the test results is performed to identify the failure location with the greatest impact on the structure. The load is then completely removed, and the structure is allowed to stabilize before continuing with the test. The specific test conditions are detailed in Table 3.

The aforementioned test conditions D1, D2, and D3 are dynamic response tests conducted while the structure is in the elastic stage, after which the structure remains operational. Test condition D4 involves applying a failure load to the structure and conducting a dynamic collapse test.

The welded hollow balls at both ends of the lower chord of the prepared polyline-shaped double-layer spatial grid structure test model are welded to the steel supports. The steel supports are then welded to two test bearing platforms, and the dimensions of the steel supports are shown in Fig. 13.

Since the test is conducted on a single structure, particular attention is paid to the out-of-plane constraints to ensure their reliability. Scaffolding is used to provide these constraints, positioned tightly against both ends of the structure and secured with couplers to achieve the required stability.

The loading process utilizes a suspended platform constructed from steel cables, steel plates, and fasteners. The suspension points of the platform are set at the upper chord connection nodes, as shown in Fig. 14. Steel plates serve as placement platforms, while fasteners secure critical positions. To achieve staged loading, weights of corresponding masses are gradually added to the suspended platform in batches. This method effectively simulates the mass-following behavior during the failure process of specific components and avoids unloading issues that may arise when using jacks or similar loading methods.

Test recording equipment is positioned on both sides of the test site to ensure the safety of personnel and equipment throughout the testing process. The overall layout of the test model is shown in Fig. 14, and the test site layout is illustrated in Fig. 15.

Test plan

During the test, strain and displacement data at critical locations of the structure are primarily monitored and collected. For strain measurements, strain gauges are adhered along the axial direction on the outer surface of the rods. A total of 28 strain measurement points are set (A1-A14, where An-1 and An-2 represent the upper and lower surfaces of the rod at strain measurement point An, respectively).

The displacement measurements consist of two components. First, cable displacement sensors are used at two measurement points (C1 and C2) to collect displacement data at these locations under each test condition. Second, displacement measurements near the failure device introduction locations are collected using a high-speed camera and the DIC dynamic measurement system. These measurements record displacement data under each test condition at three points (C3-C5, where C5 is further divided into C5-1 and C5-2, representing displacements under conditions D3 and D4, respectively).

The layout of the strain and displacement measurement points is shown in Fig. 16. The DH5908 and DH3822 dynamic strain and signal testing analysis systems were used for data acquisition. Numerical analysis and subsequent experimental verification confirmed that the primary frequency of the structure is lower than the sampling rates of both systems, thus meeting the test requirements. For the collection of in-plane vertical dynamic displacements of the test model, cable displacement sensors and a high-speed camera were used for recording.

Test results and analysis

Experimental phenomena

In the three test conditions during the elastic phase, structural deformation under conditions D1 and D2 was found to be negligible after the load was applied. During the subsequent dynamic response tests, it was observed that the structure experienced only minor vertical displacement at the moment the failure device was triggered. After stabilization, the structure continued to function normally. Under test condition D3, at the moment the failure device was triggered, the entire structure exhibited significant vertical displacement in-plane. Out-of-plane, the structure initially tilted towards the failure location, and after internal force redistribution, it tilted in the opposite direction, away from the failure location. However, due to the lateral constraints set in this experiment, the structure stabilized and continued to function normally. After unloading, the entire structure returned to its elastic state and restored its original configuration prior to the application of test condition D3, allowing for subsequent evaluations under other test conditions.

For test condition D4, the initial experimental phenomena were similar to those of condition D3. However, compared to D3, D4 exhibited larger in-plane vertical displacement and more pronounced out-of-plane deformation. After unloading, the upper chord rods of the structure underwent irreversible plastic deformation, with noticeable bending. A comparison of the in-plane conditions before and after the D4 test is shown in Fig. 17.

After the completion of test condition D4, the structure exhibited significant deformation, undergoing plastic deformation, and was unable to continue functioning normally. After recording all relevant data, preparations were made to dismantle the structure. Before completing the test, a comparison was made of the out-of-plane deformation before and after the test under condition D4. It was observed that before the removal of the lateral constraints, no noticeable out-of-plane displacement occurred. After removal, significant deformation appeared out-of-plane, with a slight tilt towards the side without the failure device. This verified the reliability of the lateral constraint device used in the experiment. Fig. 18 shows the comparison of out-of-plane conditions before and after the test.

Strain analysis

Based on the similarity of strain variations at the same cross-section and the structural symmetry of the experimental model, representative strain measurement points were selected from the 28 strain gauges. The measured strain values (ε) before and after failure under test conditions D1, D2, and D3 during the elastic phase are shown in Table 4.

According to the results in Table 4, significant differences exist in the impact of different test conditions on the structural strain. The dynamic response tests under test condition D1 had the least impact on the structural strain, while test condition D3 resulted in the most significant strain changes. Test condition D2 exhibited moderate strain variations.

Under the working condition D1, the A1-1 measuring point is located at the upper part of the bar introducing the failure position, and the A3-1 measuring point is located at the lower chord position near the failure bar. When the bar fails, the internal force of the structure is redistributed, resulting in a sudden change in the strain at A1-1 and A3-1, from positive strain to negative strain rapidly. In addition, the strain direction of other measuring points did not change after the internal force redistribution, but the strain values were increased compared with those before the failure. Under working condition D2, except for several measuring points, the strain data of other measuring points before and after the start-up of the failure device are not much different from those of working condition D1. When the failure device is started, the strain of A6-1, A7-1 and A8-1 measuring points near the failure position changes abruptly, and the stress mode changes. Under the working condition D3, the strain data of the structure changes significantly before and after the failure. Multiple measuring points are affected by the internal force redistribution caused by the failure of the bar, resulting in a sudden change in the strain data and a change in the strain direction.

Overall, the strain response was most intense under test condition D3, followed by the effect of test condition D2, while test condition D1 exhibited localized strain changes and a general increase in strain. Analysis focused on the strain curves exhibiting noticeable changes, primarily those under test conditions D1 and D3, as shown in Fig. 19. It can be observed that strain energy is released instantaneously, with structural members experiencing impact, causing a rapid increase in strain. Subsequently, the strain-time curve stabilizes, indicating that the internal forces have redistributed to a state of equilibrium.

The fluctuations observed in Fig. 19 are mainly attributed to the limitations of the dynamic data acquisition instrument, which inevitably introduces noise into the raw measurements. To reflect the measurement situation, the original curve is presented in the figure, while filtered data were used in the subsequent analysis to minimize the influence of noise.

It can be seen that the closer to the failure position, the more obvious the strain mutation and the larger the strain value; in the working condition D3, the strain change value of the bar corresponding to the measuring point A8 is the most obvious, and the strain change is 1109 microstrain larger than that before the failure. The strain changes at the positions of the measuring points A6-1, A7-1 and A10-1 are 555, −474 and − 306 microstrain larger than those before the failure, respectively. The strain changes of the other measuring points have a certain mutation, but the amount of change is not larger than that of the above measuring points.

From the strain curves of each three strain measuring points under the two working conditions of Fig. 19, it can be seen that all the strain curves are divided into four stages, namely, static stability stage, dynamic impact stage, dynamic vibration stage and strain balance stage. Under the working condition D1, the average value of the strain readings at each stage is taken. When the strain of the static stability stage of A1-1, A2-1 and A3-1 before the failure of the web member is 32, 20 and 65 microstrain respectively, the strain jumps to −270, −68 and − 78 microstrain respectively when the web member suddenly fails to enter the dynamic impact stage. Subsequently, due to the structural damping, the dynamic vibration stage is entered, and the strain is reduced to −235, −48, −57 microstrain, respectively. Finally, due to the internal force redistribution of the structure, it enters the strain balance stage. Under the working condition D3, the specific strain curve patterns are basically the same. The average value of the strain readings at each stage is taken. When the strain of the static stability stage of A6-1, A7-1 and A8-2 before the failure of the upper chord is −87, −17 and 132 microstrain, respectively, the strain jumps to 673, −552 and 1340 microstrain respectively when the upper chord suddenly fails to enter the dynamic impact stage. Subsequently, due to the structural damping, the dynamic vibration stage is entered, and the strain is reduced to 468, −491, and 1241 microstrain, respectively. Finally, due to the internal force redistribution of the structure, it enters the strain balance stage.

Under test condition D4, in addition to the aforementioned selection criteria, strain gauges that can accurately describe the phenomenon were chosen as the focus for data analysis. The measured strain data is shown in Table 5.

It is found that the strain energy is released instantaneously, the strain increases sharply, and the maximum strain mutation is − 1126 microstrain, which appears at the A8 measuring point as the same as the working condition D3. Then the strain time history curve tends to be horizontal, and the internal force redistribution of the structure reaches a stable equilibrium state. In order to more intuitively see the change trend of structural strain under the test condition D4 and understand the change rule, the strain of A7-1 and A8-1 measuring points with large variation is selected as the object, and the extracted strain time history curve is shown in Fig. 20. Among them, it can be seen from Fig. 20 that the average strain values of the four stages of the two strain measuring points are : the compressive strains of A7-1 and A8-1 in the static stability stage are − 34 and − 126 microstrain, respectively. At the moment of sudden failure of the upper chord, the dynamic impact is entered, and the compressive strains are abruptly changed to − 677 and − 1350 microstrain, respectively. Subsequently, the dynamic vibration stage is carried out, and the compressive strain gradually decreases to − 577 and − 1252 microstrain.

Displacement analysis

Under test conditions D1 and D2, the displacements ∆ before and after failure at selected locations are shown in Table 6. The data obtained under test conditions D3 and D4 are presented in Table 7. The recorded data consists of two main parts: displacement measurements at two points (C1 and C2) using cable displacement sensors, and additional displacement data collected using a high-speed camera and DIC dynamic measurement system. Displacement measurements were taken near the failure device introduction locations for each test condition, with corresponding data recorded for each condition. A total of three measurement points and four sets of data were collected. The data recorded at measurement point C3 corresponds to test condition D1, while the data recorded at C4 corresponds to test condition D2. Measurement point C5 is divided into two sub-points, C5-1 and C5-2, based on the test conditions, representing displacements under test conditions D3 and D4, respectively.

Since the measurements at C3, C4, C5-1, and C5-2 were recorded by the DIC system, which requires high memory capacity, only pre- and post-failure data were captured. As a result, the displacement before failure at these measurement points is close to zero, enabling the observation of displacement changes before and after failure. For measurement points C1 and C2, initial displacements under load were recorded using cable displacement sensors. The initial displacements were similar under test conditions D1, D2, and D3, with an initial displacement of approximately 1.684 mm at C1 and 1.804 mm at C2. Under test condition D4, the initial displacements were approximately 4.015 mm at C1 and 4.481 mm at C2. To facilitate comparison with the DIC system, the displacement was zeroed before activating the failure device. The displacement changes before and after failure are shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Based on the data shown in Tables 6 and 7, It can be seen that the dangerous components of the structure are located in the upper chord, and the upper chord is more sensitive to load than the web and the lower chord. The displacement change before and after the failure under the test condition D1 is small, and the displacement change in the test condition D2 is in the middle position. The displacement changes before and after the failure of the data measured under the test conditions D3 and D4 are obvious. Therefore, according to the data in the table, the displacement time history curve of D1 to D4 test conditions excluding the initial displacement of the holding stage is extracted, as shown in Fig. 21.

It can be seen from Fig. 21 that two kinds of equipment are used to measure the displacement. Under the condition of the failure of the web member, the initial failure device is placed in the middle of the web member, which is divided into two sections. When the web member located at the edge suddenly fails, the force mode of the welded hollow ball near the failure position changes, and it will be subjected to the force along the direction of the web member at the moment of failure. The displacement measuring point C3 at this position will have a small displacement downward. Because the C1 and C2 measuring points are located at the upper chord far away from the failure position, when the edge web member suddenly fails, the influence on it is small and the displacement change is small. Under the condition of the failure of the lower chord, there are the following rules: the failure position is located in the middle of the lower chord. Because the grid structure is a typical flexural member, the deformation of the middle position is greater than that of the two sides, so the reading of the displacement measuring point C4 near the failure position is greater than that of the displacement measuring point C1 and C2 at the upper chord. In the two conditions of the failure of the upper chord, the displacement mutation size has the following rules: the displacement change of the C5-1 measuring point and the C5-2 measuring point recorded by the DIC is the largest, the displacement change of the C2 measuring point is the second, and the displacement change of the C1 measuring point is the smallest. The reason for this situation is related to the mechanical performance of the structure. The closer to the middle part of the structure, the greater the displacement, so there will be a situation where the displacement at C5-1 is greater than the displacement at C2.

Collapse mechanism analysis

This experiment involves the design of three different structural components: upper chord rods, lower chord rods, and web members. Accordingly, collapse mechanism analysis is performed based on both experimental and finite element results. When failure occurs in the web member, as observed under test condition D1, a force analysis diagram for the corresponding structural location is shown in Fig. 22. Under the loading condition, the web member suddenly fails, causing the internal forces F2 and F2’ it carries to be redistributed to the rods connected to the web member. This results in an increase in the internal forces at both ends of the failed web member. However, due to the layout characteristics of the double-layer grid structure, the arrangement of the web members is highly redundant, and their failure has minimal impact on the overall structure.

When the failure position appears on the lower chord, corresponding to the situation of the test condition D2, the corresponding position of the structure is selected to draw the force analysis diagram as shown in Fig. 23. The most direct force analysis diagram of the lower chord in the observation diagram shows that under normal force conditions, the lower chord suddenly fails. Because the load F1 is applied to the upper chord node in this test, when the internal force is transmitted to the lower chord, the lower chord mainly transmits the internal force to the supports at both ends. The failure position of the lower chord selected by the test condition D2 is located in the middle of the structure. When it suddenly fails, the internal forces F2 and F2’ originally passed to the support through the lower chord are re-transmitted to the support through the two lower chords connected to it. At the same time, due to the structural characteristics of the double-layer grid, when the bar fails, the overall structure will undergo downward deformation.

Based on the experimental structure and finite element analysis results, it can be concluded that the structure exhibits a significant collapse when the upper chord members fail. Therefore, under test conditions D3 and D4, force analysis diagrams of the local structural locations corresponding to the failure sites are drawn, as shown in Fig. 24. By observing the experimental phenomena and combining them with the force analysis, it is evident that the selected upper chord rod failure location is the most prominent point for dynamic collapse in this experiment.

Due to the direct application of load F1, the internal forces F2 and F2’ in the selected rods are relatively large. When the rod fails suddenly, the forces F2 and F2’ acting on it are redistributed to the connected rods, increasing their internal forces. For the surrounding upper chord members, the unbalanced internal forces cause the forces near the failed rod to become larger. Upon failure, there will be a displacement towards the failure location, followed by internal force redistribution, which gradually balances the forces on both sides. For the surrounding web members, the load they bear increases abruptly when the rod fails, and then gradually stabilizes.

Based on the test and finite element results of the single-bay structure, the collapse mechanism of large-span double-layer grid roof structures is analyzed. Given that multi-bay structures exhibit good lateral resistance, and considering the collapse mechanism analysis of the single-bay structure mentioned above, only the failure of the upper chord is considered in this study. Additionally, based on the overall structural arrangement, two failure scenarios are analyzed: one where the failure occurs at the edge and the other at the center.

When the failure occurs at the edge, small vertical displacements are observed on the side of the structure where failure occurs. Meanwhile, the upper chord and web members near the central part of the structure will experience partial buckling. When the failure occurs at the center, the web member on the side of the failure location will buckle, and the surrounding upper chord members will exhibit certain vertical displacements. The lower chord member will also experience bending at the failure location.

Conclusion

This study conducted dynamic collapse tests on polyline-shaped large-span double-layer grid space structures under four different working conditions. Based on the test results, the test phenomena, strain, displacement and collapse mechanism under four different working conditions were analyzed. The following can be summarized from the study as follows:

-

(1)

By designing three different failure device introduction locations, the specific behavior of the structure during progressive collapse after failure at various positions was clarified. It was found that the upper chord rods are critical components in the collapse resistance design of this structure, providing valuable insights for designers when considering the collapse resistance design of polyline-shaped large-span double-layer grid space structure.

-

(2)

The experimental results demonstrate that under test conditions D1 and D2, the structural deformation during the elastic phase was negligible, and only minor vertical displacements were observed when the failure device was activated. The structure remained stable and continued to function normally after internal force redistribution. Under test condition D3, significant vertical displacement was observed in-plane, and the structure initially tilted towards the failure location before redistributing internal forces and stabilizing in the opposite direction. Due to lateral constraints, the structure maintained stability. For test condition D4, larger vertical and out-of-plane deformations were observed, with the upper chord rods undergoing irreversible plastic deformation. After unloading, the structure failed to return to its original configuration and could no longer function. The removal of lateral constraints caused noticeable out-of-plane displacement, which verified the effectiveness of the lateral constraint system.

-

(3)

Based on the strain data obtained from the collapse experiments conducted under four different working conditions. Under the elastic phase, the D3 condition induced the largest strain change, with a maximum of 1109 microstrain at point A8-2. Under the D1 and D2 conditions, the strain changes were more localized, with moderate variations in the vicinity of the failure region. All conditions exhibit four levels of strain evolution: static stabilization, dynamic shock, dynamic vibration, and equilibrium; indicating a rapid redistribution and eventual stabilization of internal forces. A similar trend to that of Case D3 was observed for D4, with a peak change of −1126 microstrain at point A8-1, further confirming that failure at this location has the greatest impact on the continuous collapse resistance of the grid structure.

-

(4)

Among the four test conditions, the displacement changes before and after failure exhibited distinct patterns. Under D1, the growth values at points C1 and C2 were only 0.439 mm and 0.510 mm, respectively, indicating limited deformation. For D2, displacements increased moderately, with C2 reaching 36.510 mm. In contrast, significant displacement mutations were observed under D3 and D4. Under D3, point C2 showed a displacement growth of 57.729 mm, while under D4, C5-2 reached the maximum value of 74.795 mm. Overall, upper chord members experienced the most pronounced displacement changes, confirming their higher sensitivity to failure compared to web and lower chord members. Moreover, displacement amplitudes were larger near mid-span failure locations, reflecting the flexural characteristics of the grid structure.

-

(5)

The progressive collapse mechanism of the structure was clarified through experimental investigations. In single-span configurations, web member failure triggered a redistribution of internal forces, though the overall impact was limited due to the double-layer grid’s structural characteristics. Lower chord failure led to downward deformation of the structure, but the displacement was relatively small. In contrast, upper chord failure caused a significant increase in internal forces near the failure location, resulting in localized inward displacements and subsequent force redistribution that gradually reached equilibrium. The surrounding web members experienced abrupt load increases followed by stabilization. In multi-span structures, failures near the structure’s edge caused noticeable displacements and web member buckling, whereas failures at central locations produced smaller deformations and less pronounced buckling behavior.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Adam, J. M., Parisi, F., Sagaseta, J. & Lu, X. Research and practice on progressive collapse and robustness of Building structures in the 21st century. Eng. Struct. 173, 122–149 (2018).

Kabando, E. K. & Gong, J. An overview of long-span Spatial grid structures failure case studies. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 20, 1137–1152 (2019).

Alshaikh, I. M. H., Abadel, A. A. & Alrubaidi, M. Precast RC structures’ progressive collapse resistance: current knowledge and future requirements. Struct 37, 338–352 (2022).

Pang, B., Wang, F., Yang, J., Nyunn, S. & Azim, I. Performance of slabs in reinforced concrete structures to resist progressive collapse. Struct 33, 4843–4856 (2021).

Kiakojouri, F., De Biagi, V., Chiaia, B. & Sheidaii, M. R. Progressive collapse of framed Building structures: current knowledge and future prospects. Eng. Struct. 206, 110061 (2020).

Alshaikh, I. M. H., Bakar, B. H. A., Alwesabi, E. A. H. & Akil, H. M. Experimental investigation of the progressive collapse of reinforced concrete structures: an overview. Struct 25, 881–900 (2020).

Azim, I., Yang, J., Bhatta, S., Wang, F. & Liu, Q. Factors influencing the progressive collapse resistance of RC frame structures. J. Build. Eng. 27, 100986 (2020).

Ding, L. & Chen, J. Physically-based collapse failure criteria in progressive collapse analyses of random-parameter multi-story RC structures subjected to column removal scenarios. Eng. Struct. 325, 119379 (2025).

Ding, L., Chen, J. & Caspeele, R. Dynamic sensitive failure mode in the progressive collapse of RC structures subjected to column removal scenarios. Eng. Struct. 323, 119301 (2025).

Guo, Y. et al. Study on progressive collapse of overall structure based on numerical simulation method and prediction of structural collapse. J. Build. Eng. 99, 111416 (2025).

Rakhsha, F., Hatami, S., Gorji Azandariani, M., Alipour Mansourkhani, A. & Davani, M. Resistance of eccentric braced steel frames against progressive collapse and overload factor. Struct 70, 107933 (2024).

Shi, Y. & Jiang, R. Experimental investigation on progressive collapse performance of RC substructures under blast loading. Struct 70, 107803 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Qin, W., Wang, J., Xi, Z. & Fan, X. Theoretical and numerical insights into shear performance of steel- and SFCB-reinforced concrete beam-column structures in progressive collapse-resisting design. Struct 71, 108181 (2025).

Yi, F. et al. Experimental study on progressive collapse behavior of frame structures triggered by impact column removal. Eng. Struct. 321, 119022 (2024).

Tian, L., Wei, J. & Hao, J. Anti-progressive collapse mechanism of long-span single-layer Spatial grid structures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 144, 270–282 (2018).

Wei, J., Tian, L. & Hao, J. Improving the progressive collapse resistance of long-span single-layer Spatial grid structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 171, 96–108 (2018).

Tian, L., Wei, J. & Hao, J. Optimisation of long-span single-layer Spatial grid structures to resist progressive collapse. Eng. Struct. 188, 394–405 (2019).

Tian, L., Wei, J. & Hao, J. Method for evaluating the progressive collapse resistance of long-span single-layer Spatial grid structures. Int. J. Adv. Steel Constr. 15, 1–14 (2019).

Tian, L., He, J., Zhang, C. & Bai, R. Progressive collapse resistance of single-layer latticed domes subjected to non-uniform snow loads. J. Constr. Steel Res. 176, 106433 (2021).

Jihong, Y. & Nian, Q. Progressive collapse simulation based on DEM for single-layer reticulated domes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 128, 721–731 (2017).

Bai, C., Tian, L., Zhong, W. & Xu, G. Numerical simulation and performance evaluation of compression members in long-span single-layer Spatial grid structures constrained by steel bars. Struct 65, 106804 (2024).

Kolakkattil, R., Tsavdaridis, K. D. & Sanjeevi, A. J. A state-of-the-art review of progressive collapse research and guidelines for single-layer lattice shell structures. Struct 56, 104945 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Feng, R. & Cai, Q. Study on the collapse performances of fabricated single-layer Spatial network structures based on discrete beam elements. Thin-Walled Struct. 186, 110657 (2023).

Zhong, Y., Feng, R. & Ning, X. Study on the member fracture and collapse performance of single-layer grid structures using discrete solid element method. J. Build. Eng. 78, 107737 (2023).

Sheidaii, M. R. & Gordini, M. Effect of random distribution of member length imperfection on collapse behavior and reliability of flat double-layer grid space structures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 18, 1475–1485 (2015).

Fu, F. & Parke, G. A. R. Assessment of the progressive collapse resistance of double-layer grid space structures using implicit and explicit methods. Int. J. Steel Struct. 18, 831–842 (2018).

Chen, Z., Li, J., Zhang, S., Yue, Q. & Huang, S. Progressive collapse demolition of double-layer space truss under different demolition load conditions. Eng. Struct. 294, 116753 (2023a).

Chen, Z., Li, J., Zhang, S., Yue, Q. & Huang, S. Study on progressive collapse demolition method of double-layer space truss. J. Constr. Steel Res. 210, 108060 (2023b).

Liu, W., Zeng, B., Zhou, Z. & Zhang, Y. Progressive collapse resistance prediction of truss string structures under key chord failure. J. Constr. Steel Res. 212, 108285 (2024).

Liu, W., Zeng, B., Zhou, Z. & Li, X. Investigation on the progressive collapse resistance and failure mechanism of truss string structure with alternate cables. J. Build. Eng. 99, 111590 (2025).

Chenaghlou, M. R., Kheirollahi, M. & Mirzaei, M. Enhancing the seismic ductility and strength reduction factor of double-layered vaulted Spatial shells incorporating buckling-restrained compound truss elements. Struct 72, 108220 (2025).

Nie, G. et al. Shaking table test on progressive collapse of the double-layer cylindrical reticulated shell with infilled wall. Struct 67, 106946 (2024).

Nie, G., Zhang, C., Li, D., Chen, Q. & Wang, Z. Collapse of the Spatial double-layer cylinder shell by experimental study. Eng. Struct. 245, 112862 (2021).

Zhang, H., Lu, J., Wu, X. & Li, N. Progressive collapse behavior of large-span truss string structures subjected to cable failure. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 28, 1379–1391 (2024).

Tian, L., Bai, C. & Zhong, W. Experimental study and numerical simulation of partial double-layer latticed domes against progressive collapse in member-removal scenarios. Struct 29, 79–91 (2021).

Vazna, R. V. & Zarrin, M. Sensitivity analysis of double layer diamatic dome space structure collapse behavior. Eng. Struct. 212, 110511 (2020).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Code for design of grid space structures (JGJ 7-2010). (2010).

Standardization Administration of China. Seamless steel tubes for structural use (GB 8162 – 2018). (2018).

Standardization Administration of China. Metallic materials: tensile testing: part1 1: method of test at room temperature (GB/T 228. 1–2021 ). (2021).

Ding, B. D. et al. Dynamic experimental study on the progressive collapse of grid space structures based on failure of critical members. J. Vib. Shock. 34 (23), 106–114 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Open Fund of Industry Key Laboratory of Traffic Infrastructure Security Risk Management (Changsha University of Science and Technology) (21KB10) and the Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (24B0307).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongjie Liu, Yongjin Lv and Fuming Wang wrote the manuscript. Gang Li and Zhixuan Zhou prepared the FEA. Lei Liu and Bida Pei prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Lv, Y., Wang, F. et al. Dynamic experimental study on anti-progressive collapse of polyline-shaped large-span double-layer grid space structure. Sci Rep 15, 35999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19837-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19837-3