Abstract

Out-of-equilibrium Rydberg gases exhibit emergent many-body phases due to mode competition. Sustained limit cycle oscillations (OSC) emerge when driven by B-fields at room temperature, forming robust Rydberg dissipative time crystals (DTC). Here we show that DC and AC Stark fields in the sub-kHz regime can be used to precisely shift (DC) or modulate (AC) the oscillation frequency of these DTCs, providing a powerful method for controllable time-domain dynamics in a room-temperature system. The AC Stark modulation induces frequency modulation (FM) of the OSC spectrum, enabling narrowband detection of extremely weak AC electric fields in the sub-kHz regime, with DC fields detected via Stark-induced shifts of the oscillation frequency. With a modest setup, a sensitivity of ~ 7.8µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 at 300 Hz is demonstrated — an ~ 8.7× improvement over state-of-art in the sub-kHz regime. Unlike on-resonant DTC sensing that is limited to operation close to the emergent limit cycle oscillations (10–15 kHz), the present approach is effective in the DC-600 Hz sub-kHz regime. This approach overcomes the size and bandwidth limitations of classical antennas at ultra-low frequencies and establishes a new class of ultra-compact (≪λ/10⁶) Rydberg-based electric-field sensors. These results open opportunities for compact extremely low-frequency (ELF) sensors in remote sensing, communications, geophysics, and biomedical diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Harnessing collective time-domain dynamics in quantum many-body systems may unlock new regimes of sensing, signal processing, and fundamental physics. A compelling example of such dynamics is found in dissipative time crystals (DTCs) — driven, open systems that spontaneously exhibit persistent oscillations and break continuous time-translation symmetry1,2,3. These non-equilibrium phases are stabilized by a balance between external driving and internal dissipation, and are characterized by long-range temporal order and robustness to perturbations4,5,6. Rydberg atomic ensembles are particularly well-suited for exploring DTCs due to their tunable strong interactions and dense spectral structure6. When exposed to magnetic fields (B-fields) at room temperature, these systems can enter a dynamical regime of sustained limit cycle oscillations (OSC), arising from nonlinear mode competition among closely spaced excited states6. This marks the onset of a room-temperature DTC phase, governed by many-body dynamics that extend beyond equilibrium physics7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. The limit cycle oscillation (OSC) frequency is tunable through experimental parameters, showing an inverse scaling with coupling Rabi frequency⁶, and additional control via magnetic field and laser detunings.

These emergent oscillations also offer a new mechanism for electric-field (E-field) sensing at ELF, where methods based on classical antennas become inefficient due to fundamental size and bandwidth constraints. Previous work has shown that Rydberg DTCs can exhibit a sharp collective transition suitable for very-low-frequency (VLF) E-field sensing near the oscillation frequency16. In that approach, external signals were detected by coupling to the intrinsic limit cycle oscillations (OSC), where perturbations near the DTC frequency yielded sensitivity gains via injection locking. In contrast to conventional Rydberg electrometry techniques that rely on finely tuned DC Stark fields and embedded electrodes17this approach does not require optimization of polarizability via a precisely tuned DC field. Building on that foundation, this work demonstrates that both DC and AC Stark fields can be used to precisely shift or modulate the oscillation frequency of Rydberg DTCs. AC Stark modulation induces frequency modulation (FM) of the OSC spectrum, enabling narrowband detection of weak AC E-fields in the sub-kHz regime. This modulation shifts detection away from the low-frequency baseband, imprinting the detected AC signals onto FM sidebands around the OSC frequency and reducing the impact of technical noise in the readout. This sensing mechanism provides sensitivity across the ELF-to-DC spectrum — with a demonstrated sensitivity of ~ 7.8µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 at 300 Hz, an ~ 8.7× improvement over previous highly optimized Rydberg techniques17 based on DC-Stark tuning in the sub-kHz regime. Unlike the recent DTC E-field sensing16 that is limited to operation close to the emergent limit cycle oscillations (10–15 kHz), the present approach is effective in the DC-600 Hz sub-kHz regime.

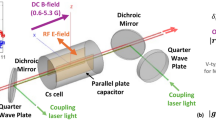

(a) Experimental setup, simulated Stark modulations, energy diagram, and spectrogram measurements. (a) Probe and coupler laser light is counter-propagated in a room-temperature vapor cell containing Cesium atoms. A parallel plate capacitor is embedded in the cell to drive low-frequency electric fields in the sub-kHz regime, and a DC magnetic field (B-field) is used to drive mode-competition at the excited Rydberg states to give limit cycle oscillations (OSC). A reference probe light is used for classical noise reduction. (b) Time-domain simulations of mode-competition between two excited states using a V-type atomic structure, driven additionally by a Stark modulation field at 0.5 Hz (2 s period) is shown within (red) and outside (blue) of the OSC regime. In the OSC regime (red), the field modulates the energy levels of the two excited states and results in a modulation of the OSC frequency in the form of a frequency modulation. (c) Measurements and simulations of OSC at room-temperature is shown for a Stark field at 0.5 Hz, 3.07mV/cm in a spectrogram. The low frequency of the Stark field (0.5 Hz) slowly modulates the OSC frequency and is seen in the spectrogram as an approximately sinusoidal variation at 0.5 Hz. Simulation based on a V-type Stark modulated atom system gives the same behavior. Simulation parameters were chosen for qualitative agreement, not to match the experimental OSC frequency. (d) The energy diagram in the ladder configuration used for experiments are composed of a probe laser driving to the first excited state at 6P3/2 and is detuned by \(\:{\varvec{\varDelta\:}}_{\varvec{p}}/2\varvec{\pi\:}\) = +22 MHz, a coupler driving to 76D5/2 and is detuned by \(\:{\varvec{\varDelta\:}}_{\varvec{c}}/2\varvec{\pi\:}\) = -30 MHz, and a B-field of 4G is used. The Stark field modulates time-dependent shifts in the excited states that perturb the energy differences and OSC frequency. Simulations use a V-type model (gray line).

(a) Limit-cycle oscillations (LCO) at n = 76 and B = 4G under different DC Stark-field (no modulation in Stark field) magnitudes (EDC up to 4.6mV/cm). The OSC frequency shifts gradually from 10.49 kHz to 10.73 kHz due to DC Stark shifting of the Rydberg states where mode-competition, LCO, and OSC arises. (b) A strong AC Stark modulation field (EAC) is turned on with fAC =0.5 Hz for 9.56s and then turned off. Stark-driven modulation of the OSC is seen at 0.5 Hz. Slight departures from a pure sinusoid likely arise from quadratic Stark response, stray static fields adding a linear term, and weak nonlinearities of the limit cycle. When EAC is turned off, the OSC frequency reverts to steady state at ~ 10.8 kHz and is no longer AC modulated. Data in Fig. 2a is available in Supplementary Dataset 1.

Spectrograms and analysis of probe transmission signal to study OSC frequency deviation as a function of AC field magnitude. (a) AC Stark modulation frequency fAC =0.5 Hz and EAC =3.07mV/cm. (b) EAC =1.53mV/cm. (c) EAC =0.31mV/cm. (d) Extracted peak points of each spectrogram dataset is plotted for each, showing gradual reduction frequency deviation. (e) Estimation of modulation depth, β, as a function of EAC. Modulation depth is determined as the ratio of peak deviation to fAC (∆f/ fAC) in percentages. A linear fit (black line), linear fit equation, and error bar is given. Multiple traces in (b) result from higher-order FM sidebands and nonlinear mixing under specific operating conditions. Error bars show the uncertainty in β estimated from the frequency spread in a single measurement; the larger value at 3.07 mV/cm reflects greater oscillation instability at higher drive.

These results establish a new class of ultra-compact E-field sensors that operate at frequencies where the wavelength far exceeds the physical scale of the system (≪λ/10⁶ for sub-kHz RF detectors). The approach circumvents Chu’s limit for electrically small antennas18opening avenues for integrated, atom-based detectors in ELF remote sensing, navigation, communications, and biomedical diagnostics.

In this work, the Rydberg DTC realized meets the four recognized criteria: (1) spontaneous time-translation symmetry breaking, with oscillations emerging intrinsically; (2) long-range temporal order, with persistent phase-coherent oscillations; (3) robustness against perturbations from noise and parameter fluctuations; and (4) a many-body interaction–driven oscillatory phase. These features, experimentally verified in prior Rydberg DTC studies7,16underpin the sensing mechanism presented here. A detailed discussion and supporting references are provided in Supplementary Sect. 1.

Results

Measurements of probe spectrum with OSC under different and higher AC stark modulation frequencies fAC, and with and without a DC offset at fAC =150 Hz (blue vs. red) to show differences in modulation peak. The spectral measurements (as opposed to spectrogram) show frequency modulation (FM) sidebands at ± fAC on either side of the OSC frequency. To simplify comparisons, each are plotted as a function of (horizontal axis) ∆fOSC (OSC shifted and centered at 0 Hz). EAC =1.54mV/cm in all cases. At higher modulation frequencies (e.g.: >300 Hz), peak at fAC gradually reduces in intensity, however the noise base is also reduced from being further away from the skirts of the LCO’s OSC. The DC field of EDC =19.35mV/cm slightly increases the modulation sideband peak at fAC =150 Hz. Extra sidebands at 150 Hz arise from higher-order FM and mode mixing near the critical point; detection is ultimately limited at very low fAC by the OSC bandwidth (estimated about tens of Hz). Data in Fig. 4 is available in Supplementary Dataset 2.

Observed OSC Stark shifts and modulation

Atomic sensors use coherent quantum systems for ultra-sensitive detection19. Rydberg (Cs/Rb) atoms, respond efficiently to microwave and millimeter-wave fields20,21,22. Electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)23 enables detection via laser-driven transmission changes. However, highly sensitive sub-kHz-frequency E-field detection is challenging and impractical due to low photon energy, typically requiring off-resonant or indirect methods17. Previous work has shown that Rydberg DTCs enable sensitive VLF detection via coupling to intrinsic oscillations16. AC Stark modulation of room-temperature Rydberg DTCs is used here to extend this capability to the sub-kHz regime for improved E-field sensitivity.

A probe (~ 852 nm) and coupler (~ 509 nm) laser are counter-propagated in a Cs (Cesium-133) vapor cell (see Fig. 1a) at room-temperature. The probe laser drives to the first excited state at 6P3/2 and is detuned by Δp/2π = +22 MHz, a coupler driving to 76D5/2 and is detuned by Δc/2π = -30 MHz. A B-field of 4G is turned on, giving rise to splitting to sublevels and mode-competition, that results in a OSC6,16 observed in the probe laser transmission (see simulation in Fig. 1b, red). The OSC characteristics and determination of B-field with the present setup is given in a recent article16. When driven by an ELF AC Stark E-field at fAC =0.5 Hz, the OSC time-domain response is modulated at fAC (Fig. 1b, red, simulated). Figure 1c shows experiment (top) and simulated (bottom) results for EAC =3.07mV/cm in a spectrogram (time-frequency). The Stark field, with fAC =0.5 Hz, modulates the OSC frequency, appearing as an approximately sinusoidal variation with a periodicity at 0.5 Hz. The energy diagram is given in Fig. 1d. The B-field drives sublevels \(\left| s \right\rangle\) and \(\:\left|r\right\rangle\) into mode-competition and an OSC emerges. Shifts in the sublevel energies due to Stark modulation dynamically perturb the OSC frequencies. Spectrogram simulations using a V-type atom (gray, Fig. 1d) reproduce experiments closely in Fig. 1c (bottom, simulated). Figure2a shows the steady-state OSC spectrum from the probe transmission (via balanced photodetection, PD power) due to a DC E-field up to EDC =4.6mV/cm. The OSC frequency varies between 10.49 kHz (EDC =0 V/cm) to about 10.72 kHz, showing a direct correlation between DC field amplitude and OSC frequency shift. In Fig. 2b, a strong AC Stark modulation field (EAC) is applied at fAC =0.5 Hz for ~ 9.5s before being switched off. During this period, Stark-driven modulation of the OSC is observed at 0.5 Hz. Once EAC is turned off, the OSC frequency stabilizes at approximately 10.8 kHz, returning to a steady state without AC modulation. Details of the experimental setup and systems are given in Methods and Supplementary Sect. 2.

Sensitivity analysis of AC E-field (EAC) detection via modulation side-band magnitude detection and dependence on DC E-field (EDC). (a) EAC is varied between 1.535mV/cm to 15.35µV/cm for fAC at 150 Hz and 300 Hz. At fAC =150 Hz, measurements are conducted with and without a DC Stark field (blue line is with DC field, EDC =19.35mV/cm, which is close to the optimal point, see (b)). The DC field only slightly increases the signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio (improved sensitivity) at fAC =150 Hz (20.79 µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 with DC field to 26.5 µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 without the DC field). At a higher modulation frequency of fAC =300 Hz without the DC field, the noise-base reduction results in improved sensitivity to as high as 7.88 µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2. (b) The estimated SNR in dB at fAC =150 Hz as a function of EDC is shown for three AC field measurements (EAC of ~ 921µV/cm, ~ 445µV/cm, ~ 104µV/cm). SNR is maximized between EDC ~16–20 mV/cm, with corresponding improvements over zero bias of 4.39 dB, 6.76 dB, and 7.00 dB for the three data sets (mean of 6.05 dB). A resolution bandwidth of 10 Hz is used in all measurements. The SNR drop near EDC ~5–10 mV/cm arise from reduced OSC Q-factor and frequency pulling/re-locking, a behavior dependent on multiple operating parameters and will be investigated in future work. Data in Fig. 5a is available in Supplementary Dataset 3.

Dependence on E-field magnitude and frequency

To study AC Stark E-field magnitude (EAC) dependence, first the spectrogram measurement of the probe transmission spectrum is studied at fAC =0.5 Hz for EAC =3.07, 1.53, 0.31mV/cm in Fig. 3a-c (top to bottom). Due to the strong field and low-frequencies, the frequency deviation (peak-to-peak) is seen to reduce as a function of reduced E-field magnitude. The OSC frequency as a function of time is extracted and shown in Fig. 3d, and the estimation of modulation depth, β, as a function of EAC is given in Fig. 3e. The modulation depth, β, is determined as the ratio of peak deviation to fAC (∆f/ fAC) in percentages. The observed linear (see inset of Fig. 3e) relationship between the inferred modulation depth () and the EAC suggests that the system responds linearly to the electric field magnitude. This linearity enables the system to function as a sensitive detector for measuring E-fields. The AC Stark effect induces periodic shifts in the atomic energy levels, leading to a corresponding modulation of the OSC frequency, characteristic of frequency modulation (FM). Since FM signals encode information in frequency variations via their sidebands, the modulation can be spectrally isolated, allowing the frequency of the modulated component, fAC, to be extracted with high selectivity. Figure 4 studies the probe spectrum of OSC under various AC E-field frequencies (fAC = 150, 300, 450, 600 Hz). For easier comparison, all data are shown as a function of ∆fOSC (OSC shifted and centered at 0 Hz), with EAC = 1.54 mV/cm in all cases. The spectrum shows sidebands at ± fAC of the OSC frequency. At higher modulation frequencies (e.g., > 300 Hz), the peak at fAC gradually decreases in intensity, while the noise floor also reduces as it moves further from the skirts of the OSC. For the 150 Hz measurements, a DC E-field is added and optimized to EDC = 19.35mV/cm as an attempt to favorably sensitize the atoms and maximize the signal-to-noise (SNR) (red, Fig. 4). The DC Stark field slightly enhances the modulation sideband peak.

Sensitivity to AC E-fields and under added DC fields

To study the sensitivity of the technique, the AC Stark E-field magnitude is varied between 1.535mV/cm to 15.35µV/cm for fAC at 150 Hz and 300 Hz with a measurement resolution bandwidth of 10 Hz. Figure 5a shows a sensitivity analysis. At 150 Hz, measurements with and without a DC Stark field (EDC = 19.35mV/cm, near the optimal point) give an EAC field sensitivity of 20.79µVcm⁻¹Hz⁻1/2 and 26.5µVcm⁻¹Hz⁻1/2, with the optimized DC field improving sensitivity by about ~ 27%. At 300 Hz without DC field, spectral noise reduction improves sensitivity to 7.88µVcm⁻¹Hz⁻1/2. Curve fits (black lines) show a log-log fit of measurements, and an analysis of deviation of the measured data from the fits are provided in Supplementary Sect. 3. To study dependence of SNR to DC field, EDC is varied up to 24.57mV/cm for fAC =150 Hz in Fig. 5b. The estimated SNR in dB is shown as a function of EDC for three AC field magnitudes (EAC =921.5,445.3,104µV/cm). SNR peaks between EDC =16mV/cm and 20mV/cm, with an average improvement of 6.05dB using an optimized DC field. The added DC Stark field alters the modulation sensitivity condition, enhancing or suppressing the FM sidebands as it changes how effectively the AC Stark modulation couples to the limit cycle oscillations. Additional data and analysis on power dependence as a function of DC Stark fields are provided in Supplementary Sect. 4.

Discussion

Mode competition in nonequilibrium Rydberg gases unlocks new many-body phases1,2,3giving rise to collective oscillations or limit cycles that are not constrained by the energy levels of individual atoms4,5. Sustained limit cycle oscillations (OSC) emerge when driven by magnetic-fields (B-fields) at room temperature6,16 due to the nonlinear energy shifts and competition between distinct Rydberg sublevels, giving rise to a long-range time crystalline order which manifests as a Rydberg dissipative time crystal (DTC). The sublevels are sensitive to DC or AC Stark E-fields, as they are shifted or modulated by these fields, thus shifting or modulating the OSC frequencies. The AC-Stark driven modulation of the OSC is shown as an effective technique to sense weak AC E-fields in the sub-kHz regime. With a modest setup, a sensitivity of ~ 7.8 µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 for AC signals at 300 Hz, and high-resolution detection to as low as sub-Hz is demonstrated. Even without system optimization, a ~ 8.7× improvement in sensitivity over state-of-art17 Rydberg techniques is demonstrated. Unlike earlier DTC E-field sensing limited to 10–15 kHz16 – at/near the DTC transition where limit cycle oscillations emerge, the present approach excels in the sub-kHz regime (most effective in the DC–600 Hz range). Because sensing is performed at the FM sidebands of the OSC, detection is shifted away from the low-frequency baseband where classical and technical noise dominate. The OSC frequency can be tuned through parameters such as coupling Rabi frequency⁶ or magnetic field, enabling the sensing band to be positioned in quieter spectral regions or matched to specific signal requirements. This approach facilitates the creation of ultra-compact (≪λ/106) E-field detectors, with potential significance for applications in remote sensing, communications, navigation, and biomedical technology where ELF detectors are needed.

The AC Stark-driven modulation drives a frequency modulation (FM) of the OSC frequency and is easily extracted via standard demodulation techniques by detecting the tone at the peak of the modulation sideband. A DC field can selectively enhance the SNR by about 6.05dB (measured for AC signals at 150 Hz), however that is not needed and not used for best-case sensitivity readings of ~ 7.8µVcm− 1Hz− 1/2 at 300 Hz. Numerical simulations are presented using a V-type atomic structure for simplicity. Here AC Stark is used to modulate upper states of the V-type structure and are shown to closely reproduce measured time-frequency dynamics. The approach does not require optimization of the B-field magnitude to achieve any of the stated sensitivities. Furthermore, while the DC Stark field is shown to improve SNR slightly, it is not critically needed and can be avoided to give a simpler configuration compared to existing DC Stark-shift based techniques17.

In practical implementations, the bias magnetic field can be applied using an external coil, and sub-kHz signal coupling can be enhanced by using low-screening cell materials such as monocrystalline sapphire, which has been shown to reduce Stark screening substantially and improve sub-kHz low-frequency field transmission24. Directionality and spatial filtering may be beneficial in certain applications, particularly in higher-frequency Rydberg sensing; such considerations are beyond the scope of this work.

Methods

Mean-field dynamics with Stark modulation

The purpose of the model advanced here is to provide a qualitative description of the frequency modulation (FM) of the OSC frequency. This can be achieved using a simple V-type atomic structure6,16 shown in Fig. 1d. Here the system is similar to the V-type system used to study sustained OSC in Rydberg time-crystals6 but does not require the external on-resonant drive field to externally couple the upper states16. Instead, the atomic structure is modified to include Stark shifts and modulation of the upper states \(\:\left|r\right\rangle\) and \(\:\left|s\right\rangle\) (see Fig. 1d) via an external DC or AC E-field. The Hamiltonian in the rotating frame is:

\(\:\widehat{H}=\frac{{\Omega\:}}{2}{\sum\:}_{i}\left({\widehat{\sigma\:}}_{gr}^{i}+{\widehat{\sigma\:}}_{gs}^{i}+\text{H.c.}\right)-{\sum\:}_{i}\left({{\Delta\:}}_{r}\left(t\right){\widehat{n}}_{r}^{i}+{{\Delta\:}}_{s}\left(t\right){\widehat{n}}_{s}^{i}\right)\)\(\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:+\frac{1}{2}{\sum\:}_{i\ne\:j}{V}_{ij}\left({\widehat{n}}_{r}^{i}{\widehat{n}}_{r}^{j}+2{\widehat{n}}_{r}^{i}{\widehat{n}}_{s}^{j}+{\widehat{n}}_{s}^{i}{\widehat{n}}_{s}^{j}\right)\)

where \(\hat{\sigma }_{{\alpha \beta }}^{i} = \left| {\alpha ^{i} } \right\rangle \left. {\left\langle {\beta ^{i} } \right.} \right]\) is the transition operator (\(\:\alpha\:,\beta\:=g,r,s\)), and \(\hat{n}_{\alpha }^{i} = \left. {\left| {\alpha ^{i} } \right\rangle \left\langle {\alpha ^{i} } \right|} \right]\) (\(\:\alpha\:=r,s\)) denotes the local Rydberg density. \(\:{\Omega\:}\) is the ground-to-excited state Rabi frequency. It is assumed that the interaction strengths, \(\:{V}_{ij}\), is equal in magnitude to simplify development6,16. Since the AC Stark shifting is explicitly time-dependent due to the modulation, the detuning terms for \(\:\left|r\right\rangle\) and \(\:\left|s\right\rangle\) are written as \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{r}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{s}\left(t\right)\). The system evolves on a characteristic timescale \(\:{T}_{sys}\sim\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}\left({{\Omega\:}}^{-1},{\gamma\:}^{-1}\right)\), where \(\:\gamma\:\) decay rate of the excited states, while the AC Stark modulation occurs over \(\:{T}_{mod}\sim{f}_{mod}^{-1}\). The adiabatic approximation condition \(\:{T}_{mod}\gg\:{T}_{sys}\) (or equivalently \(\:{f}_{mod}\ll\:\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}\left({\Omega\:},\gamma\:\right)\)), ensures that the system can continuously adjust to the slowly varying detuning, justifying the quasi-static approximation. The system dynamics are governed by population equations, balancing excitation, decay, and coherence, shaped by interactions and Rabi oscillations. These have been explicitly derived in prior works6,16and as a result are not rederived here. In the mean-field approximation, inter-atom correlations are neglected, allowing factorization of higher-order moments: \(\left\langle {\hat{n}_{r}^{i} } \right.\left. {\hat{\sigma} _{{gr}}^{j} } \right\rangle \approx \left\langle {\hat{n}_{r}^{i} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle \left\langle {\hat{\sigma} _{{gr}}^{j} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle ,\,\left\langle {\hat{n}_{s}^{i} } \right.\left. {\hat{\sigma} _{{gs}}^{j} } \right\rangle \approx \left\langle {\hat{n}_{s}^{i} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle \left\langle {\hat{\sigma} _{{gs}}^{j} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle\) Assuming a uniform spatial distribution where \(\left\langle {\hat{n}_{r}^{i} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle = n_{r}\) and \(\left\langle {\hat{n}_{s}^{i} } \right.\left. {} \right\rangle = n_{s}\), the nonlinear energy shift due to atomic interactions is given by: \(\:{E}_{NL}=\chi\:\left({n}_{r}+{n}_{s}\right)\), where \(\:\chi\:\) captures the atomic interaction strength6. In the adiabatic limit, the mean-field population and coherence equations are:

Theoretical simulations of the imaginary part of \(\:{\varvec{\sigma\:}}_{\varvec{g}\varvec{r}}\) based on the mean-field treatment under varying AC Stark modulations. (a) A generic V-type model is driven to exemplify the LCO’s OSC transients in the < 1ms regime (Ω/γ = 3.29, ∆/δ =±0.32). Outside the OSC regime (∆/δ =+0.32, blue) the ℑ[σgr] rapidly decays within ~ 0.5ms, whereas within the OSC regime (∆/δ =-0.32, red), a self -sustained oscillation emerges. (b) When AC stark modulation with fAC =0.5 Hz (αr/δ = 126.7 and αs/δ=-32.8) is applied, a modulation of ℑ[σgr] is observed (red). (c) Applying an AC Stark modulation field (fAC =0.3 kHz, 0.5 kHz) results in sidebands at ± fAC relative to the OSC frequency when the spectrum of ℑ[σgr] is observed. Reduction in AC field magnitudes (calculated at fAC =0.5 kHz) results in peak modulated signal intensity reduction at ± fAC. For the 0.5 kHz cases (blue, orange, yellow), sideband amplitudes increase with AC field strength, while the purple trace corresponds to 0.3 kHz and is not directly comparable.

with \(\:{\alpha\:}_{r,s}\) being the polarizabilities of states \(\:\left|r\right\rangle\) and \(\:\left|s\right\rangle\). The AC Stark modulation \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{r}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{s}\left(t\right)\) is observed to directly influence the phase evolution of the coherence terms \(\:{\sigma\:}_{gr}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{gs}\), leading to a modulation of the limit cycle oscillations. Since these coherence terms drive population dynamics, their periodic modulation at the Stark shift frequency \(\:{f}_{mod}\) induces corresponding variations in the oscillatory behavior of \(\:{n}_{r}\) and \(\:{n}_{S}\). This can be understood from the phase-dependent terms in the mean-field equations, where the coherence evolves as \(\dot{\sigma }_{{gr,s}} \sim i\left( {\Delta _{{r,s}} \left( t \right) - E_{{NL}} } \right)\sigma _{{gr,s}}\), showing that time-dependent detuning introduces a periodic phase modulation that propagates through the system, modifying the limit cycle oscillations.

Numerically solving the mean-field equations, \(\:\mathfrak{I}\left({\sigma\:}_{gr}\right)\) is extracted which corresponds to probe transmission response from the ground to the intermediate state in experiments. Figure 6 shows the mean-field simulations of for \(\:\mathfrak{I}\left({\sigma\:}_{gr}\right)\) under different AC Stark modulations. Figure 6a, b shows a characteristic transient solution for \(\:\mathfrak{I}\left({\sigma\:}_{gr}\right)\) without OSC (blue), with OSC (red). In this example calculation, \(\:{\Omega\:}/\gamma\:\sim3.2\) and \(\:{\Delta\:}/\delta\:\sim\pm\:0.32\:\)(sign + is expected to show no OSC) is used to simply appreciate the nature of OSC transients (Fig. 6a) and modulation (Fig. 6b). Here \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{r0}={\Delta\:}\) and \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{s0}={\Delta\:}-\delta\:\). When outside the limit-cycle oscillation regime (blue), any initial oscillations decay rapidly, whereas in the OSC regime a self-sustained oscillation is formed (red). Using \(\:{\alpha\:}_{r,s}\) =135.45, -35.15 MHz (computed by diagonalization of the Stark Hamiltonian within a defined basis of nearby states for \(\:j\) =5/2, 3/2), and a EAC =3.3mV/cm AC field at 0.5 Hz, Fig. 6b shows a modulation in the time-domain. The observed humps (red, Fig. 6b) arise from a slow phase modulation due to the time-dependent Stark shift, conceptually due to FM modulation but within the context of nonlinear atomic dynamics. Figure 1c (bottom) showed a time-frequency analysis via a spectrogram, observing the deviation of the OSC frequency as a function of time. Figure 6c studies the spectrum \(\:\mathfrak{I}\left({\sigma\:}_{gr}\right)\) for sub-kHz AC Stark modulated fields. Applying an AC Stark modulation field (fAC =0.3 kHz, 0.5 kHz) introduces sidebands at ±fAC around the OSC frequency (which is at ~8.06 kHz) in the spectrum of \(\:\mathfrak{I}\left({\sigma\:}_{gr}\right)\). Decreasing the AC field magnitude (shown for fAC =0.5 kHz) reduces the intensity of the modulated signal peaks at ±fAC,, demonstrating sensitivity of FM sideband magnitude to AC Stark field magnitude. In Fig. 6c, a DC field of 6.7mV/cm is used to reduce shifts in OSC frequencies.

Experimental setup and approach

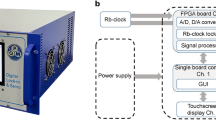

The probe laser drives 6S1/2 F = 4 to 6P3/2 F’=4 transition, with its frequency locked to the hyperfine structure using saturation absorption spectroscopy. The probe wavelength is \(\:{\lambda\:}_{p}\sim\)852.35672 nm, with a linewidth < 58 kHz and detuning \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{p}/2\pi\:\) =+22 MHz. It has a Rabi frequency of \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{p}/2\pi\:\) =13.97 MHz and a 1.1 mm (1/e²) beam diameter. A half-wave plate (λ/2) sets the polarization before a Calcite beam displacer, which generates two orthogonally polarized probe beams with a 2.8 mm offset. A quarter-wave plate (λ/4) ensures slight elliptical polarization, optimized to maximize signal-to-noise for the OSC and AC signals observed via probe balanced-amplified-photodetection (BAP) on a spectrum analyzer (SA). The beams pass through a vapor cell, centered between an embedded parallel-plate capacitor (PPC). The BAP output is split (-3dB RF splitter) between an oscilloscope and SA, with a 20 kHz low-pass filter and a DC-block filter applied to suppress higher-order modes that could distort transient OSC signals, or DC offsets that could overload the SA. The BAP was used to suppress correlated common-mode signals—such as probe laser intensity modulation. Although the reference beam passes through the cell, transit noise is uncorrelated and unsuppressed.

The coupler laser, tuned to the 76D5/2 state, is frequency locked using a cylindrical cavity (50 mm diameter × 100 mm length, finesse \(\:{F}_{c}\sim\)15k placed in a vacuum housing with internal thermal shielding. The Pound-Drever-Hall (PDH) locking technique, combined with electronic sideband (ESB) modulation, stabilizes the coupler laser wavelength (\(\:{\lambda\:}_{c}\sim\)508.80582 nm) and narrows its linewidth to < 100 Hz. The coupler detuning is \(\:{{\Delta\:}}_{c}/2\pi\:\) =-30 MHz, with a Rabi frequency \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{c}/2\pi\:\) =0.85 MHz and 1.3 mm beam diameter. Both probe and coupler lasers are commercial external cavity diode lasers (ECDLs), with the ~ 509 nm coupler generated via second harmonic generation (SHG).

The PPC embedded within the Cs vapor cell has a dimension of 18 × 45 mm, separated by 15 mm. Impedance transfer functions were measured with an impedance analyzer, and a fitted circuit model was used to calculate the relationship between voltage applied to the PPC and the resulting E-field magnitude16. The system was driven under a constant 4G B-field to develop sustained limit-cycle oscillations (OSC) between about 10.49–11 kHz. This B-field was generated by a 30 cm Helmholtz coil, spaced 15 cm apart, driven by a DC supply.

External field-enhancement structures, such as resonant cavities25 or split-ring resonators (SRR)26 could offer improvements in sensitivity; SRR’s are amenable to scaling to sub-kHz and will be studied in the future. Additional details of experimental systems and setup are presented in Supplementary Sect. 2.

Data availability

The following are available as source data: (1) The LCO spectral data at n = 76 and B = 4G under different DC Stark-field (no modulation in Stark field) magnitudes (EDC up to 4.6mV/cm) in Fig. 2a (Supplementary Dataset 1); (2) Measurements of probe spectrum with OSC under different AC Stark modulation frequencies fAC in Fig. 4 (Supplementary Dataset 2); (3) Sensitivity analysis datasets of AC E-field (EAC) detection via modulation side-band magnitude when EAC is varied between 1.535mV/cm to 15.35μV/cm for fAC at 150 Hz and 300 Hz in Fig. 5a (Supplementary Dataset 3). All other data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Darmindra Arumugam (darmindra.d.arumugam@jpl.nasa.gov).

References

Diehl, S. et al. Quantum states and phases in driven open quantum systems with cold atoms. Nature Phys 4, 878–883. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1073 (2008).

Marcuzzi, M., Levi, E., Diehl, S., Garrahan, J. P. & Lesanovsky, I. Universal nonequilibrium properties of dissipative Rydberg gases. Nat. Phys. 113, 210401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.210401 (2014).

Lee, T. E., Häffner, H. & Cross, M. C. Antiferromagnetic phase transition in a nonequilibrium lattice of Rydberg atoms. Phys Rev A. 84(3), 031402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.84.031402 (2011).

Wadenpfuhl, K. & Adams, C. S. Emergence of synchronization in a driven-dissipative hot Rydberg vapor. Phys Rev Lett. 131(14), 143002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.143002 (2023).

Dongsheng Ding et al., Ergodicity breaking from Rydberg clusters in a driven-dissipative many-body system. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl5893 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adl

Wu, X. et al. Dissipative time crystal in a strongly interacting Rydberg gas. Nat. Phys. 20, 1389–1394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02542-9 (2024).

Wilczek, F. Quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160401 (2012).

Krishna, M., Solanki, P., Hajdušek, M. & Vinjanampathy, S. Measurement-Induced Continuous Time Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 150401 (2023).

Carollo, F. & Lesanovsky, I. Exact solution of a boundary time-crystal phase transition: time-translation symmetry breaking and non-Markovian dynamics of correlations. Phys. Rev. A 105, L040202 (2022).

Iemini, F. et al. Boundary time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 035301 (2018).

Nozières, P. Time crystals: Can diamagnetic currents drive a charge density wave into rotation?. Europhys. Lett. 103, 57008 (2013).

Bruno, P. Impossibility of spontaneously rotating time crystals: a no-go theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 070402 (2013).

Nie, X. & Zheng, W. Mode softening in time-crystalline transitions of open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 107, 033311 (2023).

Watanabe, H. & Oshikawa, M. Absence of quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 251603 (2015).

Bakker, L. R. et al. Driven-dissipative time crystalline phases in a two-mode bosonic system with Kerr nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 250401 (2022).

Arumugam, D. Electric-field sensing with driven-dissipative time crystals in room-temperature Rydberg vapor. Sci Rep 15, 13446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97560-9 (2025).

Li, L. et al. Super low-frequency electric field measurement based on Rydberg atoms. Opt. Express 31, 29228–29234 (2023).

Chu, L. J. Physical limitations of omni-directional antennas. J. Appl. Phys. 19(12), 1163–1175. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1715038 (1948).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Holloway, C. L. et al. Broadband Rydberg atom-based electric-field probe for SI-traceable, self-calibrated measurements. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 62, 6169–6182 (2014).

Cox, K. C., Meyer, D. H., Fatemi, F. K. & Kunz, P. D. Quantum-limited atomic receiver in the electrically small regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 110502 (2018).

Anderson, D. A., Sapiro, R. E. & Raithel, G. An atomic receiver for AM and FM radio communication. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.2987112 (2020).

Fleischhauer, Michael and Imamoglu, Atac and Marangos, Jonathan P., Electromagnetically induced transparency: Optics in coherent media, Rev. Mod. Phys., American Physical Society, 77, 2, pg. 633–673, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.633.

Jau, Y. Y. & Carter, T. Vapor-cell-based atomic electrometry for detection frequencies below 1 kHz. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13(5), 054034. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.13.054034 (2020).

Wu, B., Liao, D., Sang, D., Liu, Y. & Fu, Y. Enhancing Sensitivity of an Atomic Microwave Receiver via a Fabry-Perot Cavity. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 73(2), 863–872. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2024.3480459 (2025).

Christopher L. Holloway, Nikunjkumar Prajapati, Alexandra B. Artusio-Glimpse, Samuel Berweger, Matthew T. Simons, Yoshiaki Kasahara, Andrea Alù, Richard W. Ziolkowski; Rydberg atom-based field sensing enhancement using a split-ring resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 16 2022; 120 (20): 204001. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0088532

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge discussions with P. Mao and D. Willey at JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology), A. Artusio-Glimpse, N. Prajapati, C. Holloway, and M. Simons at NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), and K. Cox, D. Meyer, and P. Kunz at ARL (Army Research Laboratory) as part of the NASA Instrument Incubator Program on Rydberg Radars. The research was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NM0018D0004), through the Instrument Incubator Program’s (IIP) Instrument Concept Development (Task Order 80NM0022F0020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A conceived of the experiment and study reported, configured the atomic systems to include lasers and locking systems, and collected and processed all data reported in the text and figures. D.A. also developed all modeling, theoretical derivations and numerical simulations used or reported.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arumugam, D. Stark modulated Rydberg dissipative time crystals at room temperature applied to sub-kHz electric field sensing. Sci Rep 15, 35976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19859-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19859-x