Abstract

The conversion of iron tailings, a mining solid waste, into conductive concrete aligns with green engineering and supports the development of intelligent construction materials. This study employed a four-factor, four-level orthogonal test to investigate the effects of water-binder ratio, silica fume content, sand-binder ratio, and carbon fiber content on the density, compressive strength, and resistivity of carbon fiber-reinforced iron tailings conductive concrete (CF-ITCC). It is found that the compressive strength of CF-ITCC is linearly positively correlated with the density, and the correlation coefficient is 0.87. When the density ≥ 2300 kg/m3, the strength is generally more than 30 MPa, up to 44.7 MPa. The volume content of carbon fiber > 0.25% gives it excellent conductivity, with a minimum of 616 Ω cm. The sand-binder ratio dominates the density and strength, and the carbon fiber content dominates the resistivity, and the ratio combination of minimum density, maximum strength and optimal conductivity is determined. Microscopically, the hydration products C–S–H gel and calcium hydroxide enhance the strength, and carbon fiber and iron tailings form a conductive network to reduce the resistance. The material has the application value of solid waste resource utilization and intelligent construction, and promotes the innovative practice of engineering materials teaching through interdisciplinary experimental system. This research presents a novel approach for utilizing iron tailings and improving concrete conductivity. Additionally, a composite engineering materials experiment system integrating materials science, construction technology, and environmental engineering was developed. This system expanded traditional teaching frameworks and supported teaching reform by enhancing students’ understanding of engineering materials theory and strengthening their innovative and practical abilities. The multidisciplinary paradigm demonstrates strong application value in ecological governance and engineering education reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the aim of catering to the ever-expanding demand for diverse alloys in our daily lives, the extraction of iron and other metallic ores has been on a steady upward trend globally1. As the iron and steel industry has witnessed rapid advancements in recent years, the iron tailings generated from the ore dressing process have come to constitute a progressively larger proportion of industrial solid waste. It is approximated that for every ton of beneficiated iron ore, 400 kg of tailings are produced2. The extensive accumulation of these iron tailings not only leads to the squandering of valuable land resources but also poses a significant menace to the surrounding ecological environment, potentially giving rise to issues such as soil contamination, water pollution, and vegetation degradation3,4,5,6. Consequently, the proper treatment and comprehensive utilization of iron tailings hold crucial economic and environmental implications. Simultaneously, conductive concrete material has emerged as a focal point of research in the field of building materials at present. Given that iron tailings contain metals with conductive phases, it becomes possible to develop iron tailings conductive concrete (CF-ITCC), which offers a promising avenue for the efficient utilization of industrial waste and drives innovation in the building materials domain.

Currently, the conductive fibers frequently utilized in concrete primarily consist of carbon fibers and steel fibers, as indicated in references7,8,9,10. A multitude of scholars have carried out corresponding scientific investigations on concrete blended with diverse conductive fibers to enhance its conductivity. Wang et al.11 determined that the optimal dosages of conductive media in asphalt concrete were 0.2% carbon fiber and 1.5% graphene, respectively. Donnini et al.12 observed that the resistivity of carbon fiber-reinforced mortar declines over time and attains a constant value at approximately 60 days of curing. Carbon fibers were capable of substantially reducing the resistivity of mortar, with values falling below 150 Ω·cm. Nasr et al.13 discovered that the sole addition of steel fibers and shavings could lower the electrical resistance of crushed concrete, and in the case of a double admixture, the reduction in electrical resistance was more pronounced for concrete with 0.7% and 1% steel fibers and 7% shavings.

Beyond the exploration of the electrical conductivity of concrete, the compressive strength serves as one of the assessment criteria for the mechanical attributes of iron tailings conductive concrete, as documented in references14,15,16,17,18. There are also many examples of using industrial waste to improve the mechanical properties of materials19,20,21,22,23,24. Wang et al.25 determined that cement concrete attains its peak compressive strength when the substitution rate of iron tailings sand reaches 7%. With a compressive strength of 45.88 MPa at a curing age of 7 days, Ferreira et al.26 found that the geopolymer made with iron tailings mineral sand as the aggregate has a higher compressive strength than the matrix geopolymer, suggesting that iron tailing sand can greatly improve the quality of the geopolymer. According to Raza et al.27, the modification method that uses silica fume is quite effective at increasing the recycled aggregate concrete’s compressive strength. When 8% silica fume was added, concrete with 50% and 100% recycled coarse aggregate showed an approximate 9% increase in strength. Compressive strength increased by 2–4% as a result of carbon fiber. By adding 8% silica fume and 0.5% carbon fiber, the compressive strength of concrete made entirely of recycled aggregate increased by 18%.

At present, conventional undergraduate experiments like those in civil engineering materials testing are intricately associated with their corresponding theoretical courses, as demonstrated in28. However, the content of undergraduate laboratory instruction has failed to keep up with the practical demands of scientific research and development. There is an urgent need for more profound and advanced experimental teaching for undergraduate students.

This study proposes innovative solutions in the field of material engineering: through orthogonal experiments and microscopic characterization, the synergistic mechanism of iron tailings dense skeleton and carbon fiber dispersion network is revealed for the first time, and a quantitative control method for mechanical strength and electrical conductivity in conductive concrete is established. This method uses sand-binder ratio to dominate density / strength and carbon fiber content to regulate resistivity, breaking through the limitation of single function of traditional materials. At the same time, a new path of industrial solid waste resource utilization is developed, and an interdisciplinary experimental teaching system integrating material science, environmental engineering and electrical technology is constructed to provide a new paradigm for intelligent construction and sustainable education.

Materials and methods

Raw materials

The constituents of CF-ITCC include ordinary Portland cement (P.O 42.5), silica fume, iron tailings, laboratory tap water, hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose, and a water-reducing agent. The specific water-reducing agent employed was the C1029 polycarboxylic acid water-reducing agent sourced from Falk Stock. This agent presents as a white powder and exhibits a water reduction rate of 30%. The amount of the polycarboxylic acid water-reducing agent utilized was 2% of the total mass of the cementitious materials, which is the combined mass of cement and silica fume.

Cement

The ordinary Portland cement used in the test is from Shaoxing Zhaoshan Building Materials Co., Ltd. The chemical composition shows that the content of calcium oxide is 60.5%, the content of silicon dioxide is 19.3%, the content of alumina is 4.2%, the content of iron oxide is 3.4%, and the content of magnesium oxide is 4.2%.

Silica fume

The silica fume used in the test was from Henan Platinum Casting Materials Co., Ltd. The main chemical composition was SiO2, and its content was 97.6%.

Iron tailings

The iron tailings used in the experiment were from Lizhu Iron Tailings Plant in Shaoxing. The main chemical components were SiO2, MgO, CaO, Fe2O3 and Al2O3, which were 39.3%, 20.5%, 13.8%, 10.8% and 9.4%, respectively.

The theory of closest packing primarily investigates the impact of particle size distribution on the strength of cement stone from the perspective of the fundamental structure of hardened cement stone. In the event that the particle size distribution within the cement and concrete raw material system fails to attain or approximate the particle size distribution necessary for closest packing, it becomes impossible to form hardened cement paste with low porosity and a rationally distributed pore structure during the early stage. Consequently, the strength of the cement paste in the later stage will also be adversely affected. Given that the particle size gradation of natural iron tailings is relatively uniform, the compact stacking treatment of iron tailings can enhance the microstructure and guarantee the attainment of its outstanding engineering performance. This treatment not only optimizes the internal arrangement of the iron tailings particles but also contributes to the overall improvement of the material’s mechanical properties and durability, making it a crucial step in maximizing the potential of iron tailings in concrete applications.

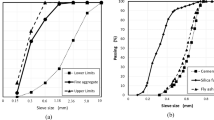

Based on the theory of the tightest accumulation, before the use of iron tailings with reference to the quartz sand particle size for its screening process, quartz sand particle size commonly used is divided into three kinds: 20 mesh–40 mesh (0.850–0.425 mm), 40 mesh–70 mesh (0.425–0.212 mm), 70 mesh–120 mesh (0.212–0.15 mm). The iron tailings particle size was sieved into three parts: coarse sand (1–0.5 mm), medium sand (0.5–0.25 mm), and fine sand (0.25–0.1 mm), and the results of sieving are shown in Fig. 1. In the figure, mF / mM is the mass ratio of fine sand to medium sand, and mC / mF+M is the mass ratio of coarse sand to medium and fine sand (the sum of the mass of medium sand and fine sand). Finally, the combination of mF / mM = 0.8 and mC / mF + M = 0.7 was selected, at which time the bulk density of iron tailings was 1341 kg/m3.

Carbon fiber

The carbon fiber used in the test was selected from Shenzhen Hongda Chang Evolution Technology Co. The length of the selected carbon fibers was 6 mm and the diameter was 7 μm, and their mechanical properties are listed in Table 1.

The key factor for carbon fibers to play an electrically conductive role in concrete is the uniform dispersion of carbon fibers. Li et al.29 found that 200,000 viscosity hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as a dispersant can be effectively dispersed carbon fibers, and the dosage of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose for the carbon fibers 20% of the mass of carbon fibers. Concrete’s mechanical qualities and electrical conductivity can be enhanced by the efficient dispersion of carbon fiber at this dose. As a result, 20% of the mass of carbon fiber was dosed with hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose, which was chosen as the dispersant. Figure 2 depicts hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose, while Table 2 lists its fundamental characteristics. Figure 3 displays the distributed carbon fiber.

Experimental design

Based on the comprehensive analysis of the main factors of previous studies, four main factors are listed in Table 3, which are water-cement ratio (the ratio of the mass of water and cementitious material, and the cementitious material is the sum of the mass of cement and silica fume, W), silica fume admixture (the percentage of silica fume to the mass of cement, G), sand-cement ratio (the ratio of the mass of iron tailings to the mass of cementitious material, I), and the admixture of carbon fibers (the percentage of carbon fibers to the volume of all the materials, C).

Four levels were used for orthogonal tests, and the conventional design table in Table 4 was used to create a total of 16 sets of mixed tests.

Sample preparation

In this study, a cylindrical sample with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 50 mm was used according to Chinese code JTG 3420-202030. The main preparation process is shown in Fig. 4. The preparation process is divided into three steps: the first step is the preparation of the mixture, in turn, the cement, silica fume, water reducing agent dry mixing 2 min, adding iron tailings continue mixing 3 min31. in addition, hydroxymethyl cellulose was dissolved in water to make a viscous solution, and carbon fiber was added to disperse and stir for 4 min to form hairy29. Finally, the fiber solution was mixed with the dry material and stirred for 6 min. The second step is to mold the sample. After the mold is coated with machine oil, it is loaded into the mixture, pressed with a 5t jack, and demoulded with a 3t jack. The third step is sample curing: the sample is first standardly cured for 3d, and then soaked in water for 3d, 7d, 14d and 28d respectively. It should be noted that the surface moisture needs to be dried before testing.

Test methods

Unconfined compressive strength test

The loading rate of the test process is selected with reference to the relevant provisions in the Chinese code JTG3420-202030, and the loading rate of the testing machine is 1kN/s. The testing equipment is UTM7305 compressive testing machine with a range of 300kN, as shown in Fig. 5.

Resistivity test

The resistivity testing apparatus chosen was the TH2810B + LCR digital bridge, adopts AC power supply, and sets the frequency to 10kHZ. The cylindrical specimen was positioned between two parallel electrodes. At each extremity of the cylinder, two layers of conductive sheets were arranged, with the graphite sheet making direct contact with the cylinder’s surface, and then a copper sheet was placed atop the graphite sheet. Eventually, a 465-g metal counterweight was placed on the upper part of the cylinder to guarantee a favorable contact between the cylindrical sample and the electrodes, as depicted in Fig. 6. The resistivity measurement was executed by configuring the test voltage and frequency. Once the reading on the display had stabilized, the resistance value of the sample was recorded for further analysis.

SEM test

A scanning electron microscope manufactured by JEOL was used to test the CF-ITCC samples after 28d of maintenance. Small particles removed from the crushed samples were placed in a freeze dryer to remove excess water and the samples were removed after 24 h. Before the SEM test, an ion sputterer was used to overlay a layer of metallic platinum on the sample surface. The whole test procedure is shown in Fig. 7.

Results and analysis

Analysis of the effect of each factor

The test results of density, compressive strength (28d) and resistivity (3d, 7d, 14d and 28d) of CF-ITCC are summarized in Table 5.

The density of CF-ITCC ranged from 1956 to 2384 kg/m3, the compressive strength ranged from 14.1 to 44.7 MPa, and the resistivities for 3d, 7d, 14d, and 28d ranged from 244 to 16609 Ω cm, 367 to 22863 Ω cm, 99 to 26173 Ω cm, and 616 to 65446 Ω cm, respectively. The resistivity usually increases with the increase of curing time.This is because during the curing process, the pores increase due to the consumption of free water by the hydration reaction, which hinders ion migration; at the same time, hydration products such as C–S–H gel gradually cover and block the conductive path of carbon fiber. In addition, the fiber dispersion state changes from uniform to possible agglomeration, which together leads to a decrease in charge transfer ability.

An in-depth exploration into the relationship between the density and compressive strength of CF-ITCC has been conducted. It has been ascertained that a linear correlation exists between these two parameters. The data points corresponding to the 16 sets of test results are found to lie within the 95% prediction interval, with a relatively high correlation coefficient of 0.87, as illustrated in Fig. 8. Evidently, as the density of the specimen escalates, there is a concomitant upward trend in its compressive strength. The increase of density reduces the porosity and makes the hydration products and distribution more uniform. Specifically, when the density of the specimen reaches 2300 kg/m3, the compressive strength of CF-ITCC predominantly exceeds 30 MPa. Solely from the perspective of the compressive strength criterion, it can be deduced that the specimens in Group 6 and Group 15 exhibit the most optimal fitting ratios, attaining compressive strengths of 44.7 MPa and 44.4 MPa respectively, The two groups show a synergistic optimization effect. The combination of low sand binder ratio (I1 = 0.8) or medium and high silica fume content (G3 = 18%) and high fiber content (C4 = 1%) makes both reach ultra-high strength above 44 MPa. This discovery not only deepens our understanding of the material’s mechanical properties but also provides valuable insights for its practical application and further optimization in relevant engineering fields.

The resistivity of conductive concrete typically exhibits an upward tendency as the curing period lengthens, as reported in11. The resistivity behavior of CF-ITCC is in line with this general conclusion. As depicted in Fig. 9, with the exception of groups 7, 8, 11, 12, and 14, the resistivity values of the remaining groups at the 28-day curing stage are less than 3000 Ω cm. This finding implies that CF-ITCC essentially possesses conductive characteristics. Notably, when the volume doping level of carbon fiber surpasses 0.4%, CF-ITCC is endowed with favorable conductive properties. Merely considering the aspect of electrical conductivity, it can be inferred that the specimens in Group 9 demonstrate the most optimal performance, as their 28d resistivity is a remarkably low 616 Ω cm. This not only showcases the potential of CF-ITCC in electrical applications but also provides a valuable reference for further enhancing its conductivity through precise control of material composition and curing conditions.

The resistivity range of CF-ITCC at 28d is 616 Ω cm-2404 Ω cm after removing several groups of high resistivity mixture ratios. The electrical conductivity of other conductive concrete at 28d curing age is shown in the table. It can be seen that the electrical conductivity of CF-ITCC is excellent (Table 6).

Range analysis and analysis of variance

RA also referred to as intuitive analysis, represents a methodology for dissecting a problem by contrasting the average extreme variance of each factor. The RA value is determined by the disparity between the maximum and minimum of the average effect of a particular factor. Through a comparison of the magnitudes of the extreme variances of various factors, it becomes feasible to identify the principal influencers on a specific indicator among multiple factors and subsequently deduce the optimal combination of factor levels, as elucidated in36. The detailed computational procedures are delineated in Eqs. (1) and (2). This approach offers a practical means of discerning the relative significance of different factors and aids in optimizing the overall performance of a system or process under investigation.

where Ki is the sum of experimental data of level i corresponding to each factor, i = 1, 2, 3, 4 in this experiment. ki is the average effect of level i corresponding to each factor. R is the range of each factor.

Upon the completion of the measurement for each group of samples, the test data were subjected to processing using Eqs. (1) and (2) to obtain the Ki, ki, and R values for each factor. Here, the R value represents the differential impacts of the four factors on the properties of the samples within the current test. Specifically, a larger R value implies a greater extent of influence exerted by the factor on the performance of CF-ITCC, whereas a smaller R value indicates a relatively lesser degree of influence on this particular performance. This quantitative analysis through the derived values provides a clear understanding of the relative significance of each factor in determining the characteristics and performance of CF-ITCC, thereby facilitating a more informed evaluation and optimization of the material’s properties for various applications.

RA has the advantage of promptly determining the optimal combination of factors with respect to specific indicators in the test. However, it fails to distinguish the test results from the test errors, thus rendering it susceptible to inaccuracies. In contrast, ANOVA is predominantly employed for conducting significance tests on the differences between the means of two or more samples. It can more distinctly differentiate the disparities in the test results that are caused by the factor levels and the errors37,38. Consequently, ANOVA and the analysis of extreme variance are mutually contrasting yet complementary, enabling a more accurate determination of the significance of the differences between the factors in the test39. The detailed computational procedures are as follows. The robustness and validity of the study’s conclusions are increased by this combination of analytical techniques, which offer a more thorough and trustworthy way to comprehend the intricate relationships and influences present in the experimental data.

-

(1)

1) Based on the value of Ki in Eq. (1) the sum of squared deviations for each factor can be calculated as in Eq. (3).

$$S_{j} = \frac{{\sum {K_{i}^{2} } }}{m} - \frac{\sum y }{n}$$(3)where, Sj is the sum of squared deviations of the factors. m is the number of trials for each level, m = 4. y is the sum of the indicators. n is the total number of trials.

-

(2)

2) The variance calculation was performed according to Eq. (4) based on the results of Eq. (3).

$$F = \frac{{S_{j} }}{r}$$(4)where, F is the variance of each factor. r is the degree of freedom of each factor, r = 3 in this experiment.

-

(3)

3) The ANOVA table used ☆ to indicate significance, ☆ to indicate significance, and ☆☆ to indicate highly significant. The F.DIST.RT function in Excel software can be used to determine the significance of each factor for CF-ITCC, with P < 0.05 being significant and P < 0.01 being highly significant.

Density

The density measurement outcomes of the 16 groups of samples were meticulously analyzed using both RA and ANOVA. Table 7 displays the comprehensive findings. It is clear from the RA results that each factor’s degree of influence on the density of CF-ITCC is arranged in the following declining order: I > G > W > C. When examining the results obtained from ANOVA, it can be clearly seen that none of these four factors exerts a significant impact on the density of CF-ITCC. The significance ranking of these four factors in terms of their influence on the density, from the most significant to the least, is: I > G > W > C. A comparison with the RA results reveals that the ANOVA findings regarding the density of CF-ITCC are in perfect alignment with those of the extreme variance analysis. This consistency not only validates the reliability of the two analytical methods but also provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors’ roles in determining the density of CF-ITCC, which is crucial for optimizing its formulation and performance in practical applications.

Figure 10 shows the curves of density of CF-ITCC with respect to ki value of each factor. From the figure, it can be seen that I is the most influential factor on the density of CF-ITCC, and the density of the samples with I = 1.2 is reduced by 10% compared to the sample with a I = 0.8. This is because of the strong ability of iron tailing sand to adsorb water, and when the dosing of iron tailing sand increases, the iron tailing sand adsorbs more free water, which makes the cementitious material not fully reacted with water, and the mixture as a whole is in the form of sand, and thus its density is low40. The effects of W and G on the density of CF-ITCC are closer. When the W increased from 0.18 to 0.24, the density of CF-ITCC increased from 2058 to 2231 kg/m3. The effect of G from 10 to 18% on the density of CF-ITCC was close to that of CF-ITCC, and the density of CF-ITCC was 2188 kg/m3. Carbon fiber had the least effect on the density of CF-ITCC. In summary, I, W and G has a greater effect on the density of CF-ITCC, C has the least effect, and the mix ratio with the lowest density is W1G1I3C3.

Compressive strength

Table 8 presents the outcomes of both RA and ANOVA with respect to the compressive strength of CF-ITCC. Upon examining the results of RA, it is apparent that the descending order of the influence exerted by each factor on the compressive strength of CF-ITCC is I > G > C > W. When considering the results obtained from ANOVA, it can be clearly discerned that both factors G and I have a significant impact on the compressive strength of CF-ITCC, whereas factors W and C do not exhibit a significant effect. The ranking of the significant effects of these four factors on compressive strength, from the most pronounced to the least, is I > G > C > W. By comparing the results of RA and ANOVA, it is evident that the RA findings for the compressive strength of CF-ITCC are in concordance with those of the ANOVA. This congruence not only substantiates the reliability of the two analytical methods but also furnishes a more profound understanding of how each factor contributes to the compressive strength of CF-ITCC, thereby providing valuable insights for optimizing its mechanical properties in practical applications.

Figure 11 depicts the graphs demonstrating the fluctuation of the compressive strength of CF-ITCC in proportion to the value of ki for each factor. Evidently, factor I exerts the most important influence on the compressive strength of CF-ITCC. In particular, the specimen’s compressive strength at I = 1.2 decreased by 17.1 MPa in comparison to its compressive strength at I = 0.8, This is due to the excessive adsorption of water by iron tailings, which actually reduces the effective water-cement ratio that can be used for hydration. Although this may slightly increase the strength, the more important effect is that its adsorption leads to insufficient local hydration and interface weakening. The combined effect explains why the high sand-binder ratio significantly reduces the strength. Additionally, factor G significantly affects CF-ITCC’s compressive strength. Interestingly, at G = 18%, the average compressive strength of CF-ITCC reaches its ideal value of 32.8 MPa. Compared to the compressive strengths at G = 10%, 14%, and 22%, this indicates an increase of 101%, 25%, and 23%, This is because the highly active amorphous SiO2 in silica fume reacts with Ca(OH)2 produced by cement hydration to form more C-S–H gels with high strength, which fills the pores, refines the pore structure, and significantly enhances the matrix strength. On the other hand, factors C and W have relatively minor effects on the compressive strength of CF-ITCC. The fluctuations in the average compressive strength of CF-ITCC brought about by these two factors are 2.5 MPa and 2.6 MPa respectively, which account for 59% and 58% of the fluctuations in the average compressive strength of CF-ITCC caused by factor I. In conclusion, factors I and G have a more pronounced effect on the compressive strength of CF-ITCC, while factors C and W have a lesser impact. Moreover, the optimal compressive strength ratio is determined to be W4G3I1C4, providing valuable insights for optimizing the formulation and performance of CF-ITCC in relevant applications.

Resistivity

Table 9 presents the outcomes of both RA and ANOVA regarding the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 3-day curing age. Upon scrutinizing the results of RA, it becomes evident that the descending order of the influence degree of each factor on the resistivity of CF-ITCC is C > I > W > G. It is clearly observable from the RA results that carbon fiber exerts an extremely significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC at this particular curing stage. Additionally, factors W, G, and I also have significant impacts. Specifically, the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 3-day curing age is markedly affected by the carbon fiber. The ranking of the significant effects of these four factors on resistivity, from the most prominent to the least, is C > I > W > G. By comparing the results of RA and ANOVA, it is apparent that the RA findings for the resistivity of CF-ITCC are in harmony with those of the ANOVA. This concordance not only validates the reliability of the two analytical methods but also offers a more comprehensive understanding of how each factor contributes to the resistivity of CF-ITCC during the initial curing period, which is crucial for tailoring its electrical properties to meet specific application requirements.

Table 10 shows the results of RA and ANOVA for the resistivity of CF-ITCC at 7 d curing age. The degree to which each element influences the resistivity of CF-ITCC in descending order is C > W > G > I, according to the polar deviation data. From RA, it can be seen that the carbon fiber has a very significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 7d curing age, while there is no significant influence of W, G and I. The four factors have significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC in descending order. The significant effects of these four factors on resistivity were in descending order C > W > G > I. By comparing with the results of the RA and ANOVA, the RA of CF-ITCC resistivity was in line with the results of the ANOVA.

Table 11 shows the results of RA and ANOVA for the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 14d curing age. The RA results show that, in descending order, each factor’s degree of influence on the CF-ITCC resistivity is C > G > W > I. From the analysis of variance, it can be seen that the carbon fiber has a very significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 14 d curing age, while there is no significant influence of W, G, and I. The four factors have significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC in descending order is C > G > W > I. The significant effects of these four factors on resistivity were in descending order C > G > W > I. By comparing with the results of the RA and ANOVA, the RA of CF-ITCC resistivity was in line with the results of the ANOVA.

Table 12 shows the results of RA and ANOVA of the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 28d curing age. From the results of RA, it can be seen that the degree of influence of each factor on the resistivity of CF-ITCC is C > W > G > I in descending order from RA. The carbon fiber has a very significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC at the 28d curing age, while there is no significant influence of W, G, and I. The four factors have significant influence on the resistivity of CF-ITCC in descending order. The significant effects of these four factors on resistivity were in descending order C > W > G > I. By comparing with the results of the RA and ANOVA, the RA of CF-ITCC resistivity was consistent with the results of the ANOVA.

According to the results of orthogonal experiment and the analysis of conductive mechanism, the excellent conductivity (616 Ω cm at 28d) of group 9 is mainly attributed to its highest carbon fiber content (C = 1.0%) and its effective conductive network, which is the dominant factor. At all curing ages, the contribution of carbon fiber content to resistivity is far greater than other factors.

Figure 12 shows the curves of the resistivity of CF-ITCC with the value of ki of each factor at 3d, 7d, 14d and 28d curing ages. The carbon fiber content (C) is the most critical factor affecting the resistivity of CF-ITCC, and its influence exhibits strong nonlinear characteristics. Especially when C increases from 0.25% to 1.0%, the 28d resistivity decreases by an astonishing 96%. This nonlinear behavior can be mainly explained by seepage theory41. When the carbon fiber content is low (such as C = 0.25 ), the fibers are isolated and dispersed in the matrix or only form a limited disconnected cluster. The electron transport mainly depends on the cement matrix and iron tailings particles with high resistance, resulting in high overall resistivity. With the increase of C, the fiber spacing decreases and the probability of forming conductive clusters increases. When C reaches or exceeds a certain critical threshold, the randomly distributed carbon fibers suddenly form a percolation path throughout the material, and electrons can be efficiently transmitted through this low-resistance path, resulting in a sharp decrease in resistivity by orders of magnitude. This sudden change of resistivity near the critical threshold is a typical sign of seepage phenomenon.

Compared with C = 0.25%, the resistivity of CF-ITCC at C = 1% decreased by 92%, 91%, 94%, and 96% at the curing age of 3d, 7d, 14d, and 28d, respectively. The effects of W, G, and I on the resistivity of CF-ITCC were relatively small. At the age of 3d curing age, the changes in CF-ITCC resistivity caused by these three factors were 296 Ω cm, 251 Ω cm, and 296 Ω cm, respectively, which were 21%, 18%, and 21% of the changes in CF-ITCC resistivity caused by C. At 7d curing age, the CF-ITCC resistivity changes caused by these three factors were 735 Ω cm, 633 Ω cm, and 416 Ω cm, respectively, which were 33%, 28%, and 18% of CF-ITCC resistivity changes caused by C. At 14d curing age, the resistivity changes of CF-ITCC caused by these three factors were 1204 Ω cm, 1200 Ω cm, and 1004 Ω cm, respectively, which were 24%, 24%, and 20% of resistivity changes of CF-ITCC caused by C. At 28d curing age, the CF-ITCC resistivity changes caused by these three factors were 3838 Ω cm, 3939 Ω cm, and 2772 Ω cm, respectively, which were 34%, 35%, and 25% of CF-ITCC resistivity changes caused by C. It can be seen that the change in CF-ITCC resistivity caused by each factor grows as the curing age increases. The optimum mix ratio for resistivity is W4G2I3C4.

According to the calculation of grey correlation analysis32, the grey correlation coefficient of group 15 is 0.785, which has the optimal performance based on density, compressive strength and resistivity, which is consistent with the conclusion of this paper.

SEM analysis

In order to explore the microscopic morphology of CF-ITCC, three groups of representative specimens in the orthogonal test were selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examination. The corresponding images are shown in Fig. 13. Among them, the upper three images are processed by ImageJ software with 500 times the SEM image, the middle three images are enlarged by 500 times the mirror, and the next three images are enlarged by 2000 times. Specifically, Fig. 13a, d, g involve specimens of group 15, Fig. 13b, e, h correspond to specimens of group 12, and Fig. 13c, f, i are related to specimens of group 3. In order to explore the microstructure of CF-ITCC and its relationship with macroscopic properties, based on Table 5 of orthogonal test results, three groups of samples with significant differences and representativeness in 28d compressive strength and 28d resistivity were selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation. Group 15 (W4G3I2C4): represents a combination of high mechanical properties (44.4 MPa) and excellent electrical conductivity (1423 Ω cm), with the highest carbon fiber content (C = 1%). Group 12 (W3G4I2C1): represents a combination of medium mechanical properties (28.2 MPa) and high resistivity (63,112 Ω cm), with the lowest carbon fiber content (C = 0.25%). Group 3 (W1G3I3C3) represents a combination of medium-to-lower mechanical properties (20.7 MPa) and good electrical conductivity (1841 Ω cm), with a high carbon fiber content (C = 0.75%).

The purpose of this selection is to cover the typical variation range of performance in orthogonal design, especially the extreme value and intermediate state of compressive strength and resistivity, and to focus on the influence of carbon fiber content on microstructure, so as to more clearly reveal the relationship between microstructure and macroscopic properties.

After processing 500 times SEM images under the microscope by ImageJ software, we calculated the proportion of the 15th, 12th and 3rd groups of carbon fibers in the selected image area, which were 12%, 0% and 35%, respectively. As can be observed from Fig. 13, within the specimens of group 15 and group 3, multiple fibers are interspersed. This fiber interspersion constitutes the primary cause underlying the relatively small resistivity of CF-ITCC. Concurrently, certain iron tailings are also discernible in the figure. These iron tailings interconnect with the carbon fibers via the concrete matrix, thereby forging a conductive pathway. Moreover, the generated gelled material covers the surface of the fiber. In contrast, the 12th group of specimens incorporated only a meager amount of carbon fibers. Consequently, it is considerably more challenging to detect the presence of carbon fibers traversing the specimen, and the internal structure of this specimen appears more compact and smooth. Notably, in group 15, calcium hydroxide and C–S–H gel can be distinctly identified. These substances serve as the rationale for the elevated compressive strength exhibited by CF-ITCC. This microscopic examination furnishes crucial insights into the internal microstructure of CF-ITCC specimens, elucidating the relationships between their constituent elements and the resultant mechanical and electrical properties, which is instrumental in further optimizing the material’s performance for diverse applications.

FTIR analysis

Figure 14 shows the FTIR spectra of CF-ITCC samples, and groups 15, 12 and 3 are selected for testing. There is an O–H tensile vibration absorption band of calcium hydroxide (CH crystal) at 3448 cm−1, which is formed into silicate phase during cement hydration. After comparison, it was found that the transmittance of the group 15 sample was the most obvious, followed by the group 12, and the last group 3 sample was the weakest. The main reason for this difference is related to the decomposition of the oxygen-containing functional groups of CH crystals and graphene oxide to release CO2, which leads to the formation of carbonates42,43,44. There is a stretching vibration absorption band of CO32− group near 1426 cm−1, which is generated by the reaction of Ca(OH)2 and CO2 in the air45. In the same group, the decrease of group 15 is the most obvious, followed by group 12, and the last group 3 is the weakest, indicating the formation of calcium carbonate in iron tailings. Near 993 cm−1 is the tensile vibration absorption band of the Si–O bond of hydrated calcium silicate (C-S–H gel)46. There are Si–O-Si symmetric bending vibration absorption band of SiO2 and Si–O bending vibration absorption band of SO42− at 459 cm−147,48,49.

Effect of teaching reform

Based on the OBE teaching philosophy, the engineering materials course has two teaching objectives. Course objective 1: To familiarize students with the technical requirements of major civil engineering materials and to develop the ability to perform quality checks on commonly used engineering materials. Course objective 2: Obtain preliminary knowledge of commonly used mathematical and statistical methods such as experimental design, data analysis, and processing, and lay the necessary experimental technical foundation for conducting scientific research and other work. This teaching reform strongly supports the achievement of course teaching objective 2. In 2024, this teaching reform have implemented among students majoring in engineering management and civil engineering. There are a total of 116 students, including 75 boys and 41 girls. Through the course reform, students’ innovation ability has been significantly improved, and their project "Low carbon Modification Technology and Resource Utilization Application of Road Solid Waste" has won the second prize for undergraduate teaching practice achievements in Zhejiang Province, China. According to the method for calculating the achievement of course objectives50,51, the achievement of teaching objective 2 in the engineering materials course was calculated to be 0.82, exceeding the established teaching objective achievement of 0.65. Therefore, the application of orthogonal experimental design in the engineering materials course to iron tailings conductive concrete, exploring its strength and conductivity influence laws, analyzing its micro mechanism, supports the achievement of the teaching objectives of civil engineering materials testing course, and effectively improves students’ innovation ability. At the same time, a new path for the resource utilization of industrial solid waste has been developed, and an interdisciplinary experimental teaching system integrating materials science, environmental engineering, and electrical technology has been constructed, providing a new paradigm for intelligent construction and sustainable education.

Conclusion

-

(1)

There is a linear relationship between the compressive strength and density of CF-ITCC, and the linear formula is y = x2 − 122, R2 = 0.87. When the density of the sample is 2300 kg/m3, the compressive strength of CF-ITCC is basically above 30 MPa. When the volume content of carbon fiber exceeds 0.4%, CF-ITCC will have good electrical conductivity. This clear understanding of the relationships between the compressive strength, density, and carbon fiber doping in CF-ITCC is crucial for optimizing its formulation and performance in various applications, such as in the construction and electronics industries, where materials with specific mechanical and electrical characteristics are required.

-

(2)

According to RA and ANOVA, the sand-cement ratio is the main factor affecting the density and compressive strength of CF-ITCC, and the carbon fiber content is the main factor affecting the resistivity of CF-ITCC. The fit ratio with the minimum density is W1G1I3C3, the optimal fit ratio for compressive strength is W4G3I1C4, and the optimal fit ratio for resistivity is W4G2I3C4.

-

(3)

From the microscopic point of view, the generation of calcium hydroxide and C–S–H gel reacts to the compressive strength properties of CF-ITCC, and carbon fibers react to its electrical conductivity. Carbon fibers penetrate through the concrete and work with iron tailings to form an energized lattice that reduces resistivity. The content of cement hydration reaction products increases to improve the strength of CF-ITCC.

-

(4)

This work focuses on the research hotspot of green building materials. On the one hand, this study carried out secondary reuse of waste iron tailing sand, which greatly solved the problem of iron tailing stockpiling and a series of pollution problems. On the other hand, the conductive concrete can be used for snow melting and deicing of roads and structural health monitoring to meet the requirements of intelligent construction. It involves a number of fields, such as environmental science, materials science and electrical engineering. In terms of sustainable education and technique, this is an effective attempt to improve the teaching of a single laboratory project with favorable pedagogical consequences. By conducting this experiment, students can combine theory and practice in experimental teaching, develop a strong foundation for the development of composite applied talents in colleges and universities, pique their interest in interdisciplinary research, and greatly enhance their overall practical innovation ability.

This study has not yet evaluated the long-term durability of CF-ITCC, such as resistance to chloride ion erosion, humidity change, freeze–thaw resistance, etc. In view of the application scenarios of iron tailings materials in engineering, the performance evolution law of iron tailings materials in harsh environments will be systematically studied in the future to provide data support for engineering applications.

Data availability

Due to confidentiality agreements with the data provider, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CF-ITCC:

-

Carbon fiber-iron tailings conductive concrete

- RA:

-

Range analysis

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- m F :

-

The mass of fine sand

- m M :

-

The mass of medium sand

- m C :

-

The mass of coarse sand

- m F+M :

-

The sum of the mass of medium sand and fine sand

- W :

-

The ratio of the mass of water and cementitious material

- G :

-

The percentage of silica fume to the mass of cement

- I :

-

The ratio of the mass of iron tailings to the mass of cementitious material

- C :

-

The percentage of carbon fibers to the volume of all the materials

- K i :

-

The sum of experimental data of level i corresponding to each factor

- i :

-

Level

- k i :

-

The average effect of level i corresponding to each factor

- R :

-

The range of each factor

- S j :

-

The sum of squared deviations of the factors

- m :

-

The number of trials for each level

- y :

-

The sum of the indicators

- n :

-

The total number of trials

- F :

-

The variance of each factor

- r :

-

The degree of freedom of each factor

- P :

-

Significance

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- C–S–H:

-

Calcium–silicate–hydrate

References

Yang, Y., Yang, Z., Cheng, Z. & Zhang, H. Effects of wet grinding combined with chemical activation on the activity of iron tailings powder. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01385 (2022).

Cao, L., Zhou, J., Zhou, T., Dong, Z. & Tian, Z. Utilization of iron tailings as aggregates in paving asphalt mixture: A sustainable and eco-friendly solution for mining waste. J. Clean. Prod. 375, 134126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134126 (2022).

Wang, C., Ji, Y., Qie, R., Wang, J. & Wang, D. Mechanical performance investigation on fiber strengthened recycled iron tailings concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e02734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02734 (2024).

Ma, B.-g, Cai, L.-x, Li, X.-g & Jian, S.-w. Utilization of iron tailings as substitute in autoclaved aerated concrete: Physico-mechanical and microstructure of hydration products. J. Clean. Prod. 127, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.172 (2016).

Liu, K. et al. Effect of iron ore tailings industrial by-product as eco-friendly aggregate on mechanical properties, pore structure, and sulfate attack and dry-wet cycles resistance of concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01472 (2022).

Lang, W. et al. Splitting behavior of polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced iron ore tailings concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03839 (2024).

Mello, E., Ribellato, C. & Mohamedelhassan, E. Improving concrete properties with fibers addition. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 8(3), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1091167 (2014).

Salahaddin, S. D., Haido, J. H. & Wardeh, G. Rheological and mechanical characteristics of basalt fiber UHPC incorporating waste glass powder in lieu of cement. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(3), 102515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102515 (2024).

Butt, F. et al. Mechanical performance of fiber-reinforced concrete and functionally graded concrete with natural and recycled aggregates. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14(9), 102121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102121 (2023).

Rajkohila, A. & Chandar, S. P. Assessing the effect of natural fiber on mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of high strength concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(5), 102666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2024.102666 (2024).

Wang, Y.-Y., Tan, Y.-Q., Liu, K. & Xu, H.-N. Preparation and electrical properties of conductive asphalt concretes containing graphene and carbon fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 318, 125875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125875 (2022).

Donnini, J., Bellezze, T. & Corinaldesi, V. Mechanical, electrical and self-sensing properties of cementitious mortars containing short carbon fibers. J. Build. Eng. 20, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.06.011 (2018).

Nasr, D. & Bavafa, E. Electrically conductive roller-compacted concrete (RCC) containing BOFS, steel fiber, and steel shaving. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023(1), 6036906. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/6036906 (2023).

Zhao, J., Ni, K., Su, Y. & Shi, Y. An evaluation of iron ore tailings characteristics and iron ore tailings concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 286, 122968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122968 (2021).

Wu, R., Zhang, Y., Zhang, G. & An, S. Enhancement effect and mechanism of iron tailings powder on concrete strength. J. Build. Eng. 57, 104954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j/jobe.2022.104954 (2022).

Chen, Z., Wu, N., Song, Y. & Xiang, J. Modification of iron-tailings concrete with biochar and basalt fiber for sustainability. Sustainability. 14(16), 10041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610041 (2022).

Shi, J. et al. Properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating iron tailings powder and iron tailings sand. J. Build. Eng. 83, 108442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108442 (2024).

Zhao, J., Su, Y., Shi, Y., Wang, Q. & Ni, K. Study on mechanical properties of macro-synthetic fiber-reinforced iron ore tailings concrete. Struct. Concr. 23(1), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202100383 (2022).

Haq, M. Z. U. et al. Taguchi-optimized triple-aluminosilicate geopolymer bricks with recycled sand: A sustainable construction solution. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e02780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02780 (2024).

Haq, M. Z. U. et al. Sustainable geopolymers from polyethylene terephthalate waste and industrial by-products: A comprehensive characterisation and performance predictions. J. Mater. Sci. 59(9), 3858–3889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-024-09447-1 (2024).

Haq, M. Z. U. & Ricciotti, L. Design and development of geopolymer composite bricks for eco-friendly construction. J. Mater. Sci. 60(2), 737–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-024-10540-8 (2025).

Singh, S. et al. Optimization of cementitious composites using response surface methodology: Enhancing strength and durability with rice husk ash and steel fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 22(1), 2502652. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2025.2502652 (2025).

Haq, M. Z. U., Sood, H. & Kumar, R. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)-assisted mechanistic study: pH-driven compressive strength and setting time behavior in geopolymer concrete. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E: J. Process Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241259460 (2024).

Haq, M. Z. U. et al. Performance evaluation of geopolymer masonry units: A hybrid approach combining laboratory testing and AI modeling. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04961 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. The influence of iron tailings powder on the properties on the performances of cement concrete with machine-made sand. Coatings 13(5), 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings13050946 (2023).

Ferreira, I. C. et al. Reuse of iron ore tailings for production of metakaolin-based geopolymers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 4194–4200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.03.192 (2022).

Raza, S. S. et al. Enhancing the performance of recycled aggregate concrete using micro-carbon fiber and secondary binding material. Sustainability. 14(21), 14613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114613 (2022).

Zeng, G. et al. Preparation, characterization and application of novel photocatalytic two-dimensional material membrane: A reform of comprehensive experimental teaching. Sustainability. 15(14), 11342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411342 (2023).

Li, S., Yin, S. & Zhang, Z. Study on the conductive properties of carbon fiber-graphite on fine-grained concrete in TRC. Diam. Relat. Mater. 136, 109933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2023.109933 (2023).

MoTotPsRo, C. Testing Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering (Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China, 2020).

Jiang, P. et al. Study on the electrical conductivity, strength properties and failure modes of concrete incorporating carbon fibers and iron tailings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 36, 522–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2025.03.155 (2025).

John, S. K. et al. Tensile and bond behaviour of basalt and glass textile reinforced geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 72, 106540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106540 (2023).

Ren, Z. et al. Research on the electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of copper slag multiphase nano-modified electrically conductive cementitious composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 339, 127650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127650 (2022).

Dong, S. et al. Electrically conductive behaviors and mechanisms of short-cut super-fine stainless wire reinforced reactive powder concrete. Cement Concr. Compos. 72, 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.05.022 (2016).

Cai, J., Pan, J., Li, X., Tan, J. & Li, J. Electrical resistivity of fly ash and metakaolin based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 234, 117868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117868 (2020).

Yao, W., Mwenya, M., Liu, Y., Yao, Z. & Pang, J. Orthogonal experiment study on mechanical properties of hybrid fibre reinforced shale ceramisite concrete. Tehnički vjesnik 30(2), 660–668. https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20220804113958 (2023).

Geng, H. et al. An orthogonal test study on the preparation of self-compacting underwater non-dispersible concrete. Materials. 16(19), 6599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16196599 (2023).

Jiang, B., Xia, W., Wu, T. & Liang, J. The optimum proportion of hygroscopic properties of modified soil composites based on orthogonal test method. J. Clean. Prod. 278, 123828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123828 (2021).

Zhao, K., Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Feng, Z. & Yang, S. An experimental study on the mixing process and properties of concrete based on an improved three-stage mixing approach. Mater. Struct. 55(5), 134. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-022-01976-y (2022).

Almada, B. S. et al. Evaluation of the microstructure and micromechanics properties of structural mortars with addition of iron ore tailings. Journal of Building Engineering. 63, 105405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105405 (2023).

Chen, B., Wu, K. & Yao, W. Conductivity of carbon fiber reinforced cement-based composites. Cement Concr. Compos. 26(4), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0958-9465(02)00138-5 (2004).

Chintalapudi, K. & Pannem, R. M. R. Enhanced strength, microstructure, and thermal properties of Portland Pozzolana fly ash-based cement composites by reinforcing graphene oxide nanosheets. J. Build. Eng. 42, 102521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102521 (2021).

Yaseen, S. A., Yiseen, G. A. & Li, Z. Synthesis of calcium carbonate in alkali solution based on graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. J. Solid State Chem. 262, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2018.03.005 (2018).

Yaseen, S. A., Yiseen, G. A. & Li, Z. Elucidation of calcite structure of calcium carbonate formation based on hydrated cement mixed with graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. ACS Omega 4(6), 10160–10170. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b00042 (2019).

Vallurupalli, K. et al. Effect of graphene oxide on rheology, hydration and strength development of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 265, 120311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120311 (2020).

Haibin, Y. et al. Experimental study of the effectsof graphene oxide on microstructure and properties of cement paste composite. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 102, 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.07.022 (2017).

Rikard, Y. et al. Early hydration and setting ofPortland cement monitored by IR, SEM and Vicat techniques. Cement Concr. Res. 39(5), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.01.017 (2009).

Li, C. N. et al. Biodegradable poly (lactic acid)/TDI-montmorillonite nanocomposites: preparation and characterization. Adv. Mater. Res. 221, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.221.211 (2011).

Hong, L. C. et al. Preparation and characterization ofbiomimetic mesoporous bioactive glass-silk fibroin composite scaffold for bone tissueengineering. Adv. Mater. Res. 796, 9–14 (2013).

Jiang, P. et al. Testing small-strain dynamic characteristics of expanded polystyrene lightweight soil: Reforming the teaching of engineering detection experiments. Polymers 17(6), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17060730 (2025).

Li, N. et al. College teaching innovation from the perspective of sustainable development: The construction and twelve-year practice of the 2P3E4R system. Sustainability. 14(12), 7130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127130 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded by the First-class College Course of Zhejiang Province ([2020]77-341, [2020]77-343, [2022]3-652, [2022]3-661), and College Virtual Simulation Experiment Project of Zhejiang Province ([2021]7-442).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. supervised the overall research and led the design of the teaching reform framework. H.X. was responsible for the experimental design, data analysis, and figure preparation. W.W. provided technical supervision throughout the project. S.L. carried out the sample preparation and laboratory testing. Y.Y. contributed to the collaborative design of the study and is one of the corresponding authors. N.L. coordinated the integration of educational content and is also a corresponding author. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, P., Hu, X., Wang, W. et al. Preparation and application conductive concrete from iron tailings to the teaching reform in engineering materials courses. Sci Rep 15, 36198 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19934-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19934-3