Abstract

Compare surgical outcomes of Robot‑Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP) between patients with and without depression. This retrospective study included consecutive patients who underwent RARP at three tertiary hospitals between January 2021 and December 2023. Patients were divided into intervention and control groups based on the presence of a confirmed diagnosis of depression and the use of antidepressants for more than six months. prior to surgery. Depression, lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and overall quality of life were assessed using the Self‑Rating Depression (SDS), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and 36‑Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) scales. Other parameters included demographic characteristics, surgery-related indicators, and urinary incontinence. A total of 245 men underwent RARP surgery, and 205 patients (84%) completed the preoperative surveys and were analyzed. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics, initial PSA level, Gleason score, prostate volume, and T staging between the two groups. Additionally, both groups showed significant improvements in SDS scores, IPSS, SF-36-VT scores, and PHQ scores at the sixth month postoperatively compared to those preoperatively (all P < 0.05). Compared to the control group, the intervention group had higher preoperative and postoperative SDS and PHQ scores as well as lower SF-36 VT scores. Although there was no difference in the preoperative IPSS between the two groups, the intervention group had higher postoperative IPSS and lower rates of urinary incontinence recovery (all P < 0.05). Patients undergoing RARP who received preoperative antidepressant treatment for depression showed similar clinical symptom improvement post-surgery compared to those without depression; however, they experienced relatively more severe LUTS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a prevalent solid tumor, ranking second in incidence among male cancers globally, particularly expanding in Asian populations1. With the emergence of new robotic surgical platforms, we are now entering a new era2,3. Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP) has gained popularity due to its linked benefits, including lower perioperative bleeding, diminished postoperative pain, and reduced length of hospital stays4. Nevertheless, recent clinical studies indicate that the enhancements in Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction are not as promising as anticipated in certain PCa patients undergoing RARP5. These inconsistent surgical results have led us to investigate preoperative variables that might influence the clinical outcomes of RARP.

Patients with PCa often have comorbid depression, a condition that can significantly affect their quality of life and overall well-being6. It has been reported that approximately one in six patients with PCa suffer from depression, and about 10% of PCa patients have recent suicidal thoughts7. A meta-analysis of 27 such studies with an average study size of 158 men indicated that the prevalence of clinically significant depression among men diagnosed with PCa ranges from 15% to 18%8. In addition, a nationwide cohort study involving 180,189 diagnosed PCa patients mentioned that among all men with prostate cancer, those with depression have a 50% higher risk of mortality compared to those without depression9. Furthermore, in other surgeries, there had been increasing evidence suggests that uncontrolled preoperative depression is associated with poor surgical outcomes10,11,12. For example, Kahl et al. found that higher preoperative depression ratings were associated with lower physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)13. Due to the significant negative impact of depression on PCa patients, antidepressant treatment might have improved the surgical outcomes of RARP in patients with depression.

Despite the growing interest in RARP, there is a lack of research focusing on the efficacy and safety of antidepressant medications in this surgical context. Elsamadicy et al. demonstrated that preoperative antidepressant therapy notably enhanced postoperative pain management and functional outcomes in depressed patients following cervical surgery14. However, Vashishta et al. and Pahapill et al. suggested that preoperative antidepressant prescriptions are associated with increased opioid prescriptions and outpatient services, and these patients require more attention during the postoperative period and follow-up15,16. Redelmeier et al. reported that patients who used antidepressants in the year prior to surgery experienced a twofold increase in the likelihood of developing postoperative delirium within their study population17. In summary, the safety and effectiveness of preoperative antidepressant therapy for surgeries remains controversial. Although RARP offers unique advantages such as reduced blood loss and faster recovery, its effectiveness in patients with preoperative depression remains to be elucidated.

Therefore, our main hypothesis was that preoperative depression would significantly impact postoperative recovery and care in patients undergoing RARP. We carried out this retrospective study to analyze the variations in depression, Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), and surgical results of RARP between patients without depression and those with depression.

Methods

Patient selection

This research received approval from the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital in Chongqing, China (authorization number: CZLS2022260-A), and was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013, with the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent. This study investigated patients who underwent RARP at three tertiary hospitals between January 2021 and December 2023, and was reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of localized prostate cancer and scheduled to undergo RARP. (2) Preoperative imaging and clinical evaluation confirmed candidacy for surgical treatment without evidence of metastatic disease. (3) Patients who had not undergone any prior prostate surgery before RARP (e.g., transurethral resection of the prostate).Exclusion criteria: (1) Within one month prior to surgery, the use of medications that may affect the efficacy evaluation of antidepressants (such as calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, methotrexate, vitamin K antagonists, and antiplatelet agents, among others.).(2) Patients with a prior history of surgical intervention for prostate cancer.(3) Patients readmitted for recurrent prostate cancer.(4)Patients received radiotherapy/chemotherapy or endocrine therapy prior to surgery.(5)The postoperative data of the patients are incomplete and postoperative survival was less than six months.(6)Did not complete questionnaires related to depression in hospitals.

Finally, all screened patients were divided into the intervention (with depression) and control (without depression) groups. Patients were diagnosed with depression by a psychiatrist who had been on antidepressant therapy for a minimum of six months prior to surgery.

To minimize inter-center variability, the three hospitals adopted a standardized care pathway prior to data extraction. This included: (1) unified eligibility criteria and outcome definitions; (2) standardized perioperative management; and (3) similar postoperative protocols. The confirmation of these measures helped reduce differences across the participating centers to a certain extent.

Preoperative management

Patients first underwent prostate ultrasonography and serological assessments, followed by MRI and transperineal prostate biopsy to confirm prostate cancer. All biopsy results were obtained through transperineal MRI-ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy (targeted + systematic), performed collaboratively by experienced radiologists and urologists. Comorbid conditions such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and hypertension were effectively managed and stabilized prior to RARP.

Surgical method

All patients in this study cohort were treated by experienced surgeons using RARP. The procedures were performed using a fourth‑generation da Vinci Xi Surgical System (Model IS4000, Intuitive Surgical, USA).

All RARP procedures were conducted using the extraperitoneal approach under endotracheal intubation and general anesthesia. The surgeon was situated next to the operating table and the assistant was positioned beside the cart. The patient was initially positioned in the supine orientation. Following the insertion of a Foley catheter, the patient was positioned in the Trendelenburg position, followed by the docking of the patient cart. An incision was made in the peritoneal retroflexion at the vesicorectal recess, allowing for the posterior dissection of the seminal vesicles (SVs) and vasa deferentia (VD). Extended pelvic lymph node dissection (e-PLND) was routinely conducted for all high-risk patients and selectively for some medium-risk patients, based on individual conditions and patient preferences.

Postoperative management

Prophylactic antibiotics were administered for the first three days postoperatively. In this study, cefuroxime sodium at a dose of 1.5 g was routinely administered via intravenous infusion once daily for a duration of 1–3 days following surgery as a prophylactic measure against postoperative infection. The selection of this regimen was based on its broad‑spectrum antimicrobial activity and clinical safety profile. Subsequent adjustments to the antibiotic therapy (either escalated or discontinued) were made in accordance with postoperative monitoring results, including urine culture findings, urinalysis parameters, and the occurrence or absence of postoperative fever, so as to ensure both effective infection control and the prudent use of antibiotics. Urethral catheters were left in place for 2 or 3 weeks after surgery. Follow-ups and data collection are performed at the postoperative 1 month, and at 3 and 6 months postoperatively.

Assessment measures

Preoperative evaluation included age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol history, initial PSA level, prostate volume, Gleason score, T stage, baseline International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)18Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) score19Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) score20and Short Form 36 Health Survey Vitality Scale (SF-36 VT) score21. Surgical-related assessments included the amount of surgical bleeding, operation time, positive surgical margin (PSM), postoperative Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT), radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Data collected during follow-up included SDS scores, IPSS scores, SF-36 VT scores, PHQ scores, and incontinence recovery at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively. Initial PSA was defined as the level measured when the patient first underwent PSA testing; prostate volume was calculated based on the results of enhanced MRI; and patients’ depression status, vitality, and LUTS were evaluated using the SDS, PHQ-9, SF-36 VT, and IPSS, respectively. Incontinence recovery was defined as no longer using urinary pads.

All preoperative questionnaire data were collected within the hospital, with patients completing either electronic or paper questionnaires under the joint assistance of nursing staff and other personnel. Following RARP, patients were asked to return for hospital follow‑up at 3 and 6 months postoperatively, during which staff assisted them in completing the postoperative questionnaires again. For patients who did not return for follow‑up in a timely manner, staff conducted telephone follow‑ups to provide remote assistance in completing the questionnaires, or visited the patients in person to assist them face‑to‑face.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data, such as age, BMI, and initial PSA levels, were subjected to normality testing (Kolmogorov-Smirnov), while all categorical data, such as postoperative ADT and radiotherapy, were analyzed using the chi-square test. A P-value > 0.05 was considered indicative of passing the normality test. Consequently, only two quantitative indicators, age and the initial SF-36 VT score, met the criteria for a normal distribution. Therefore, we utilized SPSS 27.0, to conduct an independent samples t-test for age and the initial SF-36-VT score between the intervention and control groups. For other quantitative indicators that did not pass the normality test (e.g., BMI and initial PSA levels), non-parametric tests were performed. Regression analyses were conducted as sensitivity analyses using R version 4.4.2. These analyses examined the associations between preoperative antidepressant treatment (intervention vs. control) and postoperative outcomes at month 6, including SDS, IPSS, PHQ, SF‑36 VT, and urinary continence recovery. Linear regression models were applied for continuous outcomes and logistic regression models for the binary outcome. Initially, univariate regression analyses were performed for baseline and perioperative variables (T stage, alcohol history, smoking history, Gleason score, PSM, postoperative ADT, postoperative RT, postoperative chemotherapy, age, BMI, initial PSA, prostate volume, operative blood loss, operative time, baseline SDS, baseline IPSS, baseline SF‑36 VT, baseline PHQ). Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into multivariable regression models.

Results

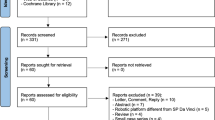

The study was conducted on the medical records of 245 patients, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 205 patients were selected, comprising 80 individuals in the intervention group and 125 in the control group(Fig. 1). The analysis revealed no significant differences between the two groups regarding age (P = 0.67), BMI (P = 0.38), smoking history, alcohol consumption (P = 0.26), initial PSA levels (P = 0.29), Gleason scores (P = 0.79), preoperative IPSS scores (P = 0.36), prostate volume (P = 0.64), and T stage (P = 0.54) (Table 1).

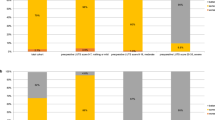

At baseline, the intervention group exhibited significantly higher SF-36-VT scores and lower SDS and PHQ scores than the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1). By the sixth month postoperatively, both groups showed significant improvements in SDS, IPSS, SF-36-VT, and PHQ scores compared to preoperative levels (all P < 0.05) (Table S1). Additionally, the intervention group had higher SDS, IPSS, and PHQ-9 scores at one, three, and six months postoperatively, with these differences being statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Conversely, the intervention group reported lower SF-36-VT scores and less incontinence recovery at one, three, and six months compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Overall, the intervention group consistently exhibited higher depression scores than the control group, along with more severe postoperative LUTS and slower recovery. This suggests that, prior to RARP, preoperative screening for depressive symptoms and antidepressant use, as well as targeted mental health optimization, may be necessary. Tailored prehabilitation strategies could help mitigate these disadvantages and improve postoperative functional recovery.

No significant differences were observed in the positive surgical margin (P = 0.70), blood loss (P = 0.06), operative time (P = 0.73), postoperative ADT (P = 0.94), radiotherapy (P = 0.85), and chemotherapy (P = 0.93) (Table 3).

Tables S2–S6 present the univariate regression results for the preoperative grouping variable (intervention vs. control), baseline data, and perioperative information in relation to SDS, IPSS, SF‑36 VT, PHQ‑9 scores, and urinary continence recovery at 6 months postoperatively. Similar to the results shown in Table 1, baseline SDS/PHQ‑9 and SF‑36 VT levels were the covariates with the greatest influence on the outcomes. These covariates were further adjusted for in the multivariable regression analyses, and the integrated results are summarized in Table 4. After covariate adjustment, preoperative antidepressant use was not significantly associated with urinary continence recovery (P = 0.05), but remained associated with higher SDS scores at 6 months (23.50 [22.10 to 24.91], P < 0.01), higher IPSS scores (2.16 [1.31 to 3.01], P < 0.01), lower SF‑36 VT scores (− 9.52 [− 13.71 to − 5.34], P < 0.01), and higher PHQ‑9 scores (2.03 [0.76 to 3.29], P < 0.01).

Discussion

Key findings

This retrospective study compared perioperative parameters and depressive status before and after RARP between prostate cancer patients with and without depression. We found that, even after receiving antidepressant treatment, patients with depression exhibited higher depression scores and lower vitality both before and after RARP. Following RARP, depressive symptoms were alleviated in both groups.

Our results also indicated that preoperative antidepressant treatment did not increase surgical risks, such as blood loss, operative time, or positive surgical margins, demonstrating its safety in the context of RARP. However, despite having similar preoperative IPSS scores, patients with depression experienced slower postoperative IPSS recovery and lower rates of urinary continence recovery.

Comparison with previous studies and implications

PCa patients, regardless of whether they had depression preoperatively, can achieve favorable perioperative outcomes and improvement in depressive symptoms following RARP. In this study, post-RARP improvements were observed across various metrics including the SDS, IPSS, PHQ, and SF-36VT scores. Based on prior published studies, we speculated that this was related to the following reasons: (1) Considering the high comorbidity of PCa and depression, undergoing RARP could reduce patients’ psychological stress, specifically reflected in the decrease in SDS and PHQ scores22. (2) Evidence suggested that patients underwent RARP typically experience less blood loss and lower transfusion rates postoperatively, along with shorter catheterization duration and reduced hospital stay, which helps accelerate recovery and minimize perioperative stress, and a positive perioperative experience contributes to alleviating patients’ depressive moods23. (3) RARP improved surgical precision through enhanced three-dimensional visualization and fine motor skills, which facilitates the preservation of surrounding nerves, thereby promoting recovery from postoperative urinary incontinence, alleviating patients’ suffering, and positively impacting their mental health24,25. After RARP treatment for PCa, all patients experienced relief from depressive moods, which further supported the correlation between PCa and depression22.

For PCa patients with depression, postoperative LUTS symptoms after RARP are more severe even when they have been receiving regular antidepressant treatment. Although postoperative urinary symptoms were controlled at normal levels, patients with depression had a higher IPSS after RARP, smaller changes in IPSS scores, and lower recovery rates for incontinence. First, this may be related to the higher SDS and PHQ scores in the intervention group, indicating more pronounced LUTS under depressive states26. This conclusion is consistent with those of previous studies. Nilsson et al. noted that men with higher levels of anxiety and depression before prostate biopsy reported more urinary and sexual adverse reactions after RP27. Depression is an independent risk factor for the exacerbation of LUTS in PCa patients9,28. Additionally, Quaghebeur et al. indicated that psychological and emotional factors influence pelvic floor and organ dysfunction, such as LUTS, via the nervous system29. Second, we hypothesized a correlation between the use of antidepressants and slower recovery from incontinence. Carvalho et al. reviewed the clinical evidence of various antidepressants on incontinence and noted that antidepressants can cause or exacerbate incontinence, a phenomenon more common among the elderly30. Similarly, the vitality of patients in the intervention group was consistently lower than that of the control group, which may be related to the greater psychological impact on patients with depression after the diagnosis of PCa31 and poorer LUTS32,33. Therefore, we believe that PCa patients who have been on long-term antidepressant medication experience poorer recovery from LUTS after RARP.

PCa patients with depression should receive additional psychological support during the perioperative period of RARP. In this study, both preoperatively and postoperatively, the intervention group patients exhibited worse outcomes in SDS scores, PHQ scores, and SF-36 VT scores compared to the control group, indicating that although patients with depression received standard antidepressant treatment, this treatment did not control their depressive symptoms and quality of life at the same level as other PCa patients34. One study showed that psychological support combined with pharmacotherapy can improve emotion recognition ability in patients with treatment‑resistant depression and is associated with a reduction in anhedonia symptoms35. This suggests that psychological support plays a positive role in improving emotional processing and overall mental health in patients with depression, which may in turn enhance postoperative recovery. In addition, the feasibility and importance of preoperative depression screening have been demonstrated. Studies have shown that preoperative depression is a frequently overlooked comorbidity, yet it has a significant impact on postoperative outcomes. Identifying depressive symptoms through preoperative screening allows for the provision of individualized perioperative interventions, thereby improving postoperative mood and overall recovery36. Such screening and intervention strategies are equally applicable to patients undergoing RARP.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. This study is fundamentally limited by its retrospective and multicenter design, which inherently carries potential biases typical of such methods, including the lack of random patient allocation, potential variability in care protocols across the three hospitals, and outcomes reported by multiple surgeons, all of which may increase confounding in our results. Additionally, the lack of preoperative data regarding the use of LUTS or specific medications may have affected the functional outcomes of patients. Another limitation is the inherent self-report bias of questionnaire-based studies, and unequal case follow-up may have affected the validity of our findings. Finally, the use and types of antidepressants are entirely determined by psychiatrists, necessitating further prospective studies to clarify the independent effects of specific antidepressants.

Future directions

Firstly, future multicenter prospective randomized controlled trials will be essential to provide high‑level evidence on the relationship between antidepressant use and postoperative recovery following RARP. In addition, elucidating the shared pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the comorbidity of depression and prostate cancer may yield novel therapeutic targets. Finally, the integration of routine psychological screening into the care pathway for patients with prostate cancer is becoming a pivotal step, and incorporating psychological interventions into disease management may play a crucial role in optimizing patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that patients with depression who underwent preoperative treatment with antidepressant medication can achieve similar clinical symptom improvements post-RARP as those without depression, but their postoperative LUTS are relatively more severe. Future studies may benefit from exploring various types of antidepressant medications and their associations with a broader range of clinical outcomes related to RARP.

Data availability

Owing to privacy regulations, please contact the corresponding author for a data request.

References

Nam, J. et al. Propensity score matched analysis of functional outcome in five thousand cases of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy versus high-intensity focused ultrasound. Prostate Int Jun. 12 (2), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prnil.2024.03.004 (2024).

Marino, F. et al. Robot-Assisted radical prostatectomy performed with the novel hugo™ RAS system: A systematic review and pooled analysis of surgical, oncological, and functional outcomes. Journal Clin. Medicine Apr. 26 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13092551 (2024).

Marino, F. et al. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy with the Hugo RAS and Da Vinci surgical robotic systems: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of comparative studies. European Urol. Focus Oct. 24 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2024.10.005 (2024).

Cornford, P. et al. Feb. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II-2020 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. European urology. ;79(2):263–282. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.046

Kohada, Y. et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of long-term postoperative urinary incontinence in patients treated with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: A propensity-matched analysis. International J. Urology: Official J. Japanese Urol. Association Jul. 17 https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.15533 (2024).

Fervaha, G. et al. Depression and prostate cancer: A focused review for the clinician. Urologic Oncology Apr. 37 (4), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.12.020 (2019).

Brunckhorst, O. et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Diseases Jun. 24 (2), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-020-00286-0 (2021).

Crump, C. et al. Long-term Risks of Depression and Suicide Among Men with Prostate Cancer: A National Cohort Study. European urology. 2023/09/01/. ;84(3):263–272. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.026

Crump, C. et al. Mortality Risks Associated with Depression in Men with Prostate Cancer. European urology oncology. Apr 3. ; (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euo.2024.03.012

Wilson, J. M., Schwartz, A. M., Farley, K. X. & Bariteau, J. T. Preoperative depression influences outcomes following total ankle arthroplasty. Foot & Ankle Specialist Aug. 15 (4), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938640020951657 (2022).

Falk, A., Eriksson, M. & Stenman, M. Depressive and/or anxiety scoring instruments used as screening tools for predicting postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery: A pilot study. Intensive & Crit. Care Nursing Aug. 59, 102851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102851 (2020).

Javeed, S. et al. Implications of preoperative depression for lumbar spine surgery outcomes: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open Jan. 2 (1), e2348565. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48565 (2024).

Kahl, U. et al. Health-related quality of life and self-reported cognitive function in patients with delayed neurocognitive recovery after radical prostatectomy: a prospective follow-up study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes Feb. 25 (1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01705-z (2021).

Elsamadicy, A. A., Adogwa, O., Cheng, J. & Bagley, C. Pretreatment of depression before cervical spine surgery improves patients’ perception of postoperative health status: A retrospective, single institutional experience. World Neurosurg. 87, 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.067 (2016). 2016/03/01/.

Vashishta, R. & Kendale, S. M. Relationship between preoperative antidepressant and antianxiety medications and postoperative hospital length of stay. Anesthesia Analgesia Feb. 128 (2), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003910 (2019).

Pahapill, N. K., Monahan, P. F., Graefe, S. B. & Gallo, R. A. Preoperative antidepressant prescriptions are associated with increased opioid prescriptions and health care use but similar rates of secondary surgery following primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a young adult population. Arthroscopy: J. Arthroscopic & Relat. Surg. : Official Publication Arthrosc. Association North. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Association Aug. 40 (8), 2246–2253e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2023.12.030 (2024).

Redelmeier, D. A., Thiruchelvam, D. & Daneman, N. Delirium after elective surgery among elderly patients taking statins. CMAJ: Canadian medical association journal = journal de l’association medicale Canadienne. Sep 23 (7), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080443 (2008).

Quek, K. F., Chua, C. B., Razack, A. H., Low, W. Y. & Loh, C. S. Construction of the Mandarin version of the international prostate symptom score inventory in assessing lower urinary tract symptoms in a Malaysian population. International J. Urology: Official J. Japanese Urol. Association Jan. 12 (1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00988.x (2005).

Dunstan, D. A. & Scott, N. Clarification of the cut-off score for zung’s self-rating depression scale. BMC Psychiatry Jun. 11 (1), 177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2161-0 (2019).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal Gen. Intern. Medicine Sep. 16 (9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Sinha, R., van den Heuvel, W. J. & Arokiasamy, P. Validity and reliability of MOS short form health survey (SF-36) for use in India. Indian J. Community Medicine: Official Publication Indian Association Prev. & Social Medicine Jan. 38 (1), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.106623 (2013).

Sharpley, C. F., Christie, D. R. H. & Bitsika, V. Depression and prostate cancer: implications for urologists and oncologists. Nature Reviews Urology Oct. 17 (10), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-020-0354-4 (2020).

Novara, G. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative outcomes and complications after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. European Urology Sep. 62 (3), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.044 (2012).

Stolzenburg, J. U. et al. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: 12-month outcomes of the multicentre randomised controlled LAP-01 trial. European Urol. Focus Nov. 8 (6), 1583–1590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2022.02.002 (2022).

Ahn, T. et al. Improved lower urinary tract symptoms after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: implications for survivorship, treatment selection and patient counselling. BJU International May. 123 (Suppl 5), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14717 (2019).

Hughes, F. M. Jr., Odom, M. R., Cervantes, A., Livingston, A. J. & Purves, J. T. Why are some people with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) depressed?? New evidence that peripheral inflammation in the bladder causes central inflammation and mood disorders. International J. Mol. Sciences Feb. 1 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032821 (2023).

Nilsson, R. et al. The association between pre-diagnostic levels of psychological distress and adverse effects after radical prostatectomy. BJUI Compass May. 5 (5), 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/bco2.334 (2024).

Crump, C. et al. Sep. Long-term risks of depression and suicide among men with prostate cancer: A National cohort study. European urology. ;84(3):263–272. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.026

Quaghebeur, J., Petros, P., Wyndaele, J. J. & De Wachter, S. Nov. The innervation of the bladder, the pelvic floor, and emotion: A review. Autonomic neuroscience: basic & clinical. ;235:102868. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102868

Carvalho, A. F., Sharma, M. S., Brunoni, A. R., Vieta, E. & Fava, G. A. The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: A critical review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 85 (5), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447034 (2016).

Pinquart, M. & Duberstein, P. R. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine Nov. 40 (11), 1797–1810. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291709992285 (2010).

Vartolomei, L. et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms are associated with clinically relevant depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The Aging Male: Official J. Int. Soc. Study Aging Male Dec. 25 (1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2022.2040981 (2022).

Glaser, A. P. et al. Impact of sleep disturbance, physical function, depression and anxiety on male lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network (LURN). The J. Urology Jul. 208 (1), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000002493 (2022).

Sørensen, A., Jørgensen, K. J. & Munkholm, K. Description of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms in clinical practice guidelines on depression: A systematic review. Journal Affect. Disorders Nov 1. 316, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.011 (2022).

Stroud, J. B. et al. Psilocybin with psychological support improves emotional face recognition in treatment-resistant depression. Psychopharmacology Feb. 235 (2), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4754-y (2018).

Fritz, B. A. & Holzer, K. J. Identifying the blue patient: preoperative screening for depression. British J. Anaesthesia Jul. 133 (1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.04.012 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the urology researchers and psychiatrists involved in this study for their assistance in the diagnosis of depression and medication guidance. We also thank all patients for providing clinical information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linfeng Wang, Qiuchen Li, and Jiajia Jin carried out the conception and design of the research, Yong Huang, Jiang Yu, Rui Sun, Hong Qiao, Qingyu Wu, and Jiajia Jin participated in the acquisition of data. Ziling Wei and Linfeng Wang performed the statistical analysis. Linfeng Wang and Rui Sun drafted the manuscript and Gaojie Zhang, Jiajia Jin participated in revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Li, Q., Sun, R. et al. Impact of preoperative antidepressant use on surgical and functional outcomes of robot assisted radical prostatectomy. Sci Rep 15, 36071 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19943-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19943-2