Abstract

Rainwater may be contaminated by leaching from roofing materials and industrial activities, rendering it unsuitable for potable use. In this study, the physico-chemical, microbiological and heavy metals parameters were investigated in harvested rainwater quality from various roof types in the urban and rural areas of Enugu State, Nigeria, between April-July, 2018. Metal compositions of asbestos, corrugated iron, Cameroun zinc, Stone-coated tiles and long span aluminium were also assessed. Thirty-six (36) harvested rainwater samples were forwarded to the laboratory after determination of pH, temperature, TDS and electrical conductivity at the point of collection. Titration, Electrometric and spectrophotometric methods of analysis were used. Results were compared with the WHO, USEPA and NSDWQ water quality standards. The weighted arithmetic method was obtained for the assessment of the water quality index. Results for heavy metals (mg/L) gave values which ranged from 0.00 to 0.20, metal concentrations (mg/kg) of digested roofs gave 0.00-63.78, and other parameters gave 6.50–7.60 for pH and Escherichia coli (no detection). The obtained results met the national and global standards except for a few samples. The WQI gave values which ranged from 3.00 to 78.46 and were rated excellent to very poor water quality. It was concluded that harvested rainwater should be treated before drinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is important for all forms of life, and water contamination is a global concern facing the world at large1. Water quality can deteriorate as a result of contamination from natural and anthropogenic activities from the environment, thereby causing water scarcity, which many humans encounter daily, making them depend on harvested rainwater for survival, mostly in the remote areas2. In regions facing the challenges of water scarcity, rainwater harvesting provides important benefits for a sustainable solution by harvesting and storing rainwater for domestic and agricultural purposes3. Rain remains the greatest source of water on earth apart from the existing rivers and oceans2. Rainwater still serves as an alternative source of drinking water for human beings and economic development due to water scarcity facing the globe, especially for the people living in developing countries1,4. Urbanization has elevated impenetrable surfaces, leading to increased peak rain run-off and cases of risk flooding, reducing recession time, impeding groundwater recharge/base flow and having a bad impact and negative influence on the water quality5,6. Accelerating increased growth in urbanization, population, and industrial activities across the globe has significantly affected the atmosphere and environment, thereby contaminating the rainwater quality2,7. Rain is acidic in nature. Rainwater is harvested when rain falls, and it is not free from contamination, usually caused by natural or anthropogenic activities, resulting from severe commercial and industrial activities, which may alter the quality of rainwater by making it highly acidic7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Industrial emissions, road traffic, combustion of fuel, heavy metals, particulate matter and other factors can cause toxicity, thereby contaminating the rainwater quality15,16,17,18. Some researchers have reported that rainwater harvesting from rooftop run-offs can be toxic through leaching of the metal roofing component or materials into the rainwater, depending on the industrial activities of an area, which had a negative effect on the water quality19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Water quality has a lot to do with the general environmental status of any area, depending on the activities of such an area, whether it is an industrial activity area or not, as reported in many scientific publications2. Water quality index measures the frequency, scope, and amplitude of water exceedances and then combines the three measures into one score, and this calculation produces a score between 0 and 100 10. Water quality index (WQI) ratings state that excellent water quality is from 0 to 25, 26–50 (good), 50–75 (poor), and 76–100 (very poor) and unfit for drinking water quality (> 100) by Rao, ICMR and Anjaneyulu26,29,30. Numerous studies by different researchers across the globe have shown that the contamination of rainwater quality is usually caused by natural and anthropogenic activities of an area and also through the medium by which the rainwater is harvested, such as roof types and other sources31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. In Nigeria, rainwater harvesting has become the best approach to address water scarcity and is recognized as a solution to the problem of total dependence on conventional water supply, thereby promoting water conservation and reducing unnecessary floods in the environment2. This research work involved studying the coating materials used in the production of the roof types to find out, if some chemical elements can corrode/leach into the rainwater quality, and also, to check if the evaluated water parameters meet the national and global standards for water quality by NSDWQ, WHO and USEPA44,45,46.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents and solvents used were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma Aldrich, USA) unless otherwise stated. Standard procedures were used to conduct the analyses to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results according to the standard methods by John-De-Zuane and AOAC47,48.

Study area

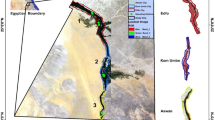

This research work was carried out in Enugu State, Nigeria and the study areas were Okpara Avenue, Enugu North local government area and Olido villages, Enugu-Ezike, Igbo-Eze local government area. Okpara Avenue is in Enugu North local government area (6027’9.60’’N7030’37.20’’E) being the urban area, it is populated by government offices, hotels, big shopping malls like Shoprites/others and different commercial motor parks are situated in this area. Olido village, Enugu-Ezike is in Igbo-Eze local government area (6041’24’’N706’53’’E) which is the rural area does not boast of any industries which can produce effluent bearing acidic gases into the atmosphere except for palm oil milling plants, exhausts of vehicles and power generating sets. Different and numerous plant species and animals are seen by these environments. The rural area supports nature’s forestry, tourism and agriculture which are important for protecting the region. The map of the study area with their coordinates is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Different roof types commonly found in Nigeria

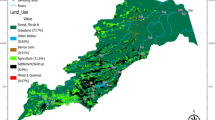

The pictures of the various roof types which are commonly found in Nigeria are long span aluminium, asbestos, corrugated iron, stone-coated tiles and Cameroun zinc roofs. Long span aluminium, Cameroun zinc and corrugated iron roofs are most likely to leach into harvested rainwater as reported by several researchers in their previous findings2,10,20,31. Rainwater was harvested from the above-mentioned roof types, which are shown in Fig. 2 below.

Sample collection and preservation/analysis

All the apparatus and sample containers used were decontaminated with 10% HNO3 solution and were properly rinsed with distilled water several times immediately before usage which was according to the standard methods by John-De-Zuane and AOAC47,48. This study was carried out in Enugu State, Nigeria in both areas during the rainy season from April-July, 2018. Thirty-six (36) harvested rainwater samples from various roofs run-off and control samples (direct) were collected in triplicate using a sterilized containers which the lid were covered with 0.45 microns in diameter sieve above the ground surface in all of the collection locations during the rainfall out in the roof run-offs and in open space for twenty-one (21) days. Immediately after the evaluation of physical characteristics for pH (Handheld Model no: HI98107 (HANNA), temperature, electrical conductivity (EC meter HACH, 44600 electrode) and total dissolved solids (TDS; Handheld TDS meter SUNSHINE, HI 9811-5) which were carried out at the point of sampling. The collected samples were later transferred into already washed plastic containers that were labelled accordingly and properly covered to avoid contamination and kept in the refrigerator at 4 °C immediately. Most of the collected rainwater samples were preserved by adding 3.0 cm3 of Concentrated HNO3 into it. Chemical parameters were analyzed in the collected rainwater samples using an UV-Visible Spectrophotometer 752P (TECHMEL, USA, 752Pro15054) and Flame-Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Dell, ICE 3000 AA02134104) and all other physico-chemical properties were assessed by AOAC and APHA48,49 standard methods.

Sample code and sources of the harvested rainwater

The collected samples were grouped and named as RWEAU/R and RWEFU/R. The samples were divided into two portions as shown in Table 1 below.

Analysis of the chemical composition of the different roof types

Different roof types were analyzed to find out their chemical composition and this was done according to the standard method48,49. Various roofing sheets used in this study were weighed one gram (1.0 g) each using Weighing balance (S-METLER, E-2000, Zurich analytical balance, Switzerland). These measured one gram of the roofing sheets were poured into different conical flasks, beakers and melting crucible pots with their respective labels. Aqua regia in the volume ratio of 3:1 (Conc. HCl; 37%, 30.0 cm3 and HNO3; 70%, 10.0 cm3) was added to each of the containers with their individual labelling for easy identification. These solutions were left to stand for 4 h, each container were subjected to a Bunsen burner fire for severe heating and boiling in a fume cupboard, till there was no trace of boiling sound heard. Each of the subjected beakers/melting crucible pots to heat were placed in a fume cupboard for one (1) day which is 24 h until the samples were digested completely, after that, de-ionized water (50.0 cm3) was added to each of the sample containers, placed on a magnetic stirrer and allowed to cool. These digested samples were filtered using Whatman No.1 filter paper for three consecutive times, to get a clear solution and de-ionized water was added to the clear solution up to the mark level. The operational settings and the analytical conditions of Flame-AAS for aluminium, lead, zinc, chromium and iron determinations as shown in Table 2 below. These digested samples were further analyzed using a Flame-AAS Spectrophotometer (Dell, ICE 3000 AA02134104) as described in the standard method by APHA49.

Assessment of E. coli

E. coli were analyzed in the rainwater samples according to the standard method by AOAC and APHA48,49. Firstly, all glassware and apparatus used were sterilized in the autoclave at 121 °C for 15 min. Cotton wool used in this analysis was decontaminated using ethanol and was used for wiping surfaces. The preparation of Eosin methylene blue agar was carried out, which was later autoclaved at 37 °C and was left at room temperature inside a water bath. Serial dilutions and Peptone water (5.0 cm3) were made, this solution was pipetted into already washed containers and the collected sample (rainwater, 1.0 cm3) was added to the solution in the Petri dishes simultaneously, thereafter, Eosin methylene blue agar (15.0 cm3) was administered to the various plates which were subjected to rigorous mixing by tilting and rotating the sterile containers which were later left to solidify. All procedures were carried out in triplicate. The sample containers for analysis were left for 24 h in an incubator at 37 °C. Immediately after the incubation period of 24 h, the morphology of the growth of bacteria was recorded and then the Gram stain (completed test) was used to determine the E. coli colonies that appeared on the Eosin methylene blue agar plates. The colonies were counted, and the colony-forming units (CFU/mL) were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Mean values generated in this study were done using Microsoft office excel 2010 for mean and standard deviation (SD). Results obtained were analyzed using the descriptive and two-way ANOVA statistical analysis of the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.

Calculation of water quality index (WQI)

This study adopts the weighted arithmetic water quality index method (WAWQIM) to evaluate the harvested rainwater contamination in the urban and rural areas of Enugu State, Nigeria following the method, as it is widely used by several researchers2,27,50. The WQI ratings are stated as follows; when it is above 100 (unfit for drinking), 76–100 (Very bad), 51–75 (Poor), 26–50 (Good) and 0–25 (Excellent). The calculation of WQI was made by using the following Eq. (1) according to Nicholas and Ukoha10;

Where,

Wn = the weightage unit of each parameter obtained as shown in Eq. (2) according to the WHO set standard values; Sn = denotes the WHO limit values for the nth parameter; qn represents the quality ratings obtained using Eq. (3). Vn represents the nth parameter of the given sampling station and Vid is the ideal value of the nth parameter in pure water (Vid for pH = 7 and zero (0) for all other parameters). In the present study, the WQI was calculated using all the rainwater analyzed parameters.

Results and discussion

The results of the different physico-chemical parameters, heavy metals and E. coli assessed in sampled rainwater of Enugu State, Nigeria from the various roof types’ run-offs and direct rainwater (control) as shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Tables S1-S3 while that of the metal composition of the roofs (Table 6 and Table S4) and Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 and the Water Quality Index (WQI) ratings (Table 7 and Table S5) and in Fig. 14 below.

pH

The pH mean values of the control samples ranged from 7.40 ± 0.20 and 7.60 ± 0.20 respectively in both areas, and asbestos roof run-off rainwater gave 7.40 ± 0.20 (urban), which showed slight alkalinity (Table 4 and Table S2) and in Fig. 3. In contrast, other analyzed samples were slightly acidic (6.50 ± 0.10–6.90 ± 0.20) as shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Tables S1-S3. The pH of the control samples when compared with the roof run-off rainwater, there was an indication of a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the values between the control samples (direct) which showed slight alkalinity and that of the roof run-offs (corrugated iron, long-span aluminium, Cameroon zinc and stone-coated tiles roofs) in both areas which presented slight acidity. This was a result of acid rain caused by industrial activities (e.g., emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) from factories or vehicles in these locations. The values obtained in this study for roof run-offs were in agreement with the earlier findings by Emerole et al., who reported slight acidity (6.2–7.6) in harvested rainwater samples from Owerri, Imo State36. Moses et al. also reported harvested rainwater in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State to be showing slight acidity12. Ojo also reported that harvested rainwater in Akure, Ondo State, had acidity as well33. Earlier researchers have reported pH values for harvested rainwater in Nigeria2,7,12,25,33,34,35,37,39,40,41,43showing acidity in the water quality. The values obtained for pH met the national and global standard of 6.5–8.5 for drinking water by NSDWQ, WHO and USEPA44,45,46.

Electrical conductivity

Electrical conductivity mean values from various roof run-off samples ranged from 32.00 ± 4.36–115.00 ± 12.00 µS/cm in both areas (Fig. 4). The electrical conductivity mean values of the control samples, in some of the roof run-offs rainwater were of very low values. The mean values of control samples ranged from 20.33 ± 3.52 and 23.00 ± 4.34 µS/cm in urban and rural areas respectively as presented in Table 4 and Table S2 above. These results were in support of earlier findings that reported lower values in the analyzed samples2,10,13,20,37,43 from Douglas Road, Owerri Municipal Council, Imo State; Maiduguri, Borno State; Warri Refinery Depot, Delta State; Nwaja, Trans-Amadi Industrial Layout in Rivers State, Oke-Lantoro, Abeokuta; and Wukari, Taraba State respectively. The values obtained for electrical conductivity met the national and global standard of 1000–1200 µS/cm for drinking water by NSDWQ, WHO and USEPA44,45,46.

TDS and TSS

Total dissolved solids (TDS) mean values of roof run-off analyzed samples ranged from 29.67 ± 2.52–51.67 ± 3.06 mg/L and 19.00 ± 6.86–67.33 ± 22.50 mg/L for total suspended solids (TSS) respectively (Figs. 5 and 6. TDS and TSS values (mg/L) of the control samples were in the range of 16.67 ± 3.51-25.00 ± 3.76 and 15.67 ± 1.53–17.33 ± 10.10 respectively in both areas. Particulate Matter (PM) in the study area showed less value and there was no reflection on control samples. The obtained results were in accordance with the findings of Chukwuma and Waziri40,41 for TDS and TSS of harvested rainwater from Oko in Anambra State and Maiduguri in Borno State which gave a range of 35.3–43.6 and 95.32-150.32 mg/L respectively which were of lower values.

Colour

The colour mean values of the control samples in both areas ranged from 0.44 ± 0.01–0.48 ± 0.02 TCU respectively (Table 4 and Table S2). Roof run-off harvested rainwater had high values of colour in stone-coated tiles (8.14 ± 2.54–9.45 ± 0.34 TCU), corrugated iron (3.30 ± 2.51–8.59 ± 0.31 TCU) and Cameroon zinc (6.11 ± 2.23–2.56 ± 2.34 TCU) roofs as shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Tables S1-S2 whereas low values of colour were found in long-span aluminium roofs (0.46 ± 0.18–0.97 ± 0.27 TCU) as seen in Table 2. Harvested rainwater collected from Cameroon zinc roofs was within the permissible limits (Tables 3, 4 and 5; Fig. 7). The colour values of control samples when compared with that of the roof run-offs, there was an indication of a high level of influence on the rainwater quality. The high levels of colour in some roof run-offs are caused by micro-pollutants, dust particles and rusted roofs. Emerole et al., 36 reported a high level of colour in harvested rainwater which ranged from 37 to 69 PCU and mean value of 56.25 PCU which differs from the present study values. Some results met with the 5 TCU set standard by WHO44 while some did not whereas all other obtained values meet the standard of 15 TCU (colour) for water quality limits by NSDWQ and USEPA45,46.

Chloride

Roof run-offs had mean chloride values ranging from 7.27 to 10.83 mg/L in the two areas as presented in (Tables 3, 4 and 5; S1-S3) and Fig. 8. Comparing the results obtained, there was evidence of no significant difference observed between the control samples and roof run-offs harvested rainwater. This observation of no significant difference was likely due to less particulate matter, dust, debris, silt and clay on the rooftop because the first flush of the rainfall might have likely cleaned the roofs. The results obtained for control and roof run-off samples are in accord with earlier findings by Chukwuma and Dinrifo40,41 gave lower concentrations of chloride in collected rainwater in Oko, Anambra State and Lagos State, Nigeria.

Alkalinity

The mean alkalinity values of control samples in the urban and rural areas were 20.00 ± 2.00 and 25.33 ± 7.02 mg/L respectively (Table 4 and Table S2). Roof runoffs had mean alkalinity values ranging from 16.00 ± 2.00-48.67 ± 3.06 mg/L in both areas as shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5; Fig. 9. The results obtained showed significant difference (p < 0.05) between asbestos roof run-offs (urban) when compared with the control samples and may be due to increased anthropogenic pollutions in the rooftop run-offs. The results are in accord with earlier findings by Ojo33who presented a lower concentration of alkalinity in harvested rainwater carried out in Akure, Ondo State for direct harvested rainwater from the sky.

Nitrate

Roof run-off harvested rainwater had nitrate mean concentrations (0.46 ± 0.01–9.43 ± 0.34 mg/L) in both areas (Tables 3, 4 and 5; S1-S3 and Fig. 10). Mean values of the control samples gave 0.44 ± 0.01 and 0.48 ± 0.02 mg/L in both areas respectively (Table 4). The obtained results of the roof run-offs and the control samples, when compared, it show that there was evidence of significant difference (p < 0.05) between stone-coated tiles roof, corrugated iron roof (rural), Cameroon zinc roof (urban) runoffs and the control samples. This is likely due to high levels of NOX in anthropogenic emissions and exhaust gas from vehicles that could be transferred into the atmosphere and then to the harvested rainwater. Also, particulate matter bearing NOX seem to be in abundance in the atmosphere/environment. Earlier findings by Ojo, Chukwuma and Moses12,33,40 gave lower concentrations of nitrate in harvested rainwater from Akure in Ondo State; Oko in Anambra State and Uyo in Akwa Ibom State, which are within the range of the present report. However, Emerole et al. 36 reported high values of nitrate (18.0-81.1 mg/L) in Owerri, Imo State collected rainwater samples.

E. coli

The obtained results were not in accordance with the findings reported by Nanji15who found E. coli in their analyzed samples in Enugu State, since E. coli was not found in this study. The values obtained met the limits of 0 cfu/mL for drinking water quality by NSWDQ and WHO44,45.

Heavy metals

The concentrations of heavy metals for control samples indicate the absence of lead (Pb) and aluminium (Al), whereas Chromium (Cr), iron (Fe) and Zinc (Zn) showed some very insignificant quantities (Table 4 and Table S2) and Figs. 11, 12 and 13. Similar results were obtained for Cameroon zinc and stone-coated tiles roofs harvested rainwater are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Tables S1-S3. The heavy metal concentrations (mg/kg) of digested roofs gave 0.00-31.84 (Pb), 0.00-43.45 (Al), 39.22–63.78 (Fe), 0.59–7.04(Zn) and 1.87–6.20 (Cr) as shown in Table 6 and Table S4 above. From the obtained results of the digested roof types, it was observed that, the heavy metals which were found in higher concentration which emanated from the materials used in manufacturing these roofs can leach into the rainwater quality in the presence of acid rain due to the industrial activities of an area/environment having a negative effect on the roofs, causing the roof types to rust, thereby releasing heavy metals into the rainwater which resulted in the contaminating of the water quality. Earlier findings reported 0.08 ± 0.06 mg/L for Pb and Cr (0.03 ± 0.02 mg/L) for direct rainwater in the rural area of Delta State, Nigeria2. Nicholas and Ukoha10 reported in their study that, there was no detection of Pb, Cr and Al in the analyzed direct harvested rainwater from the sky (control) while Fe gave mean values ranging from 0.01 ± 0.00-0.02 ± 0.01 mg/L and 0.01 ± 0.00-0.02 ± 0.00 mg/L for Zn in the urban and rural areas of Rivers State respectively13. The values obtained were not in support of the results of this study. Rainwater from roof run-offs has very low quantities of Pb (0.01 mg/L) and quite insignificant quantities of Cr, Fe, Al and Zn. Aluminium (Al) was not found in any of the roof run-offs analyzed (Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Tables S1-S3). Comparing the rainwater from roof run-offs with the control values, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the results obtained which was observed between corrugated iron, Cameroon zinc and stone-coated tiles roofs (rural) which were as a result of rusting of the roofing materials. Asbestos roof rainwater showed no significant difference (p > 0.05) with the control values due to decreased dust particles in the environment at that collection time, higher stability of the roof materials to corrosion and lesser level of emissions from vehicles and generating sets. Earlier findings reported mean values (mg/L) of heavy metals ranging from 0.02 ± 0.01–0.15 ± 0.04 for Fe, Cr (0.00 ± 0.00-0.01 ± 0.00), Zn (0.01 ± 0.00-0.03 ± 0.00) and Pb (0.00 ± 0.00-0.01 ± 0.00) and Al (0.00 ± 0.00-0.79 ± 0.06) for harvested rainwater from roofs run-offs in Rivers State respectively13. The results were not in accordance with the obtained values but in line with the values of Fe (0.11 ± 0.03–0.14 ± 0.04) for Cameroun zinc roof run-offs and 0.16 ± 0.05 for Fe (stone-coated tiles roof) which were of higher concentrations.

The obtained results for Fe in this study for Cameroun zinc and stone-coated tiles roofs harvested rainwater were in accordance with the findings of Emerole et al., who reported higher values of heavy metals in roofs run-offs harvested rainwater (mg/L) of Fe 2.12 ± 1.17 from Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria36. Earlier findings by Okudo et al. also reported high values of Pb (Emene: 0.58 ± 0.11and Iva Valley: 0.48 ± 0.04) and Cr (Emene: 0.10 ± 0.02) in rainwater samples from Enugu State13 and that of Nanji et al. who also reported higher concentrations of chromium in the road run-off harvested rainwater in Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria15 and were not in support with the values of this study. The values obtained for heavy metals in this study met the threshold limits for drinking water by NSDWQ, WHO and USEPA44,45,46 with the exception of a few samples.

The heavy metals present in the control samples, when compared with that of roof run-offs, showed evidence of a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the results which was seen between corrugated iron roof, Cameroon zinc roof, and stone-coated tiles roof (rural), as a result of rusting of the roofing materials. However, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the direct rainwater and asbestos roof run-off rainwater and this was due to decreased dust particles in the environment at that collection time, higher stability of the roof materials to corrosion and lower level of emissions from vehicles and generating sets.

Water quality index ratings

The water quality index ratings set limits by ICMR and WHO29,45 states that, water quality is said to be excellent when it is ranged between 0 and 25, 51–75 (poor water quality) and 76–100 (very poor water quality). The water quality indexes evaluated in this study yielded values ranging from 3.00 to 78.46 and were rated excellent to very poor water quality. The harvested rainwater from long-span aluminium and corrugated iron roofs in both areas and asbestos roofs (rural) were rated very poor water quality, while all other analyzed samples showed excellent water quality, which was suitable for drinking, irrigation and industrial usage as shown in (Tables 7and Table S5) and Fig. 14 above.

Conclusion

In conclusion, based on the laboratory results obtained in this present study, it was shown that the deposition of heavy metal fragments in the form of dust on rooftops is likely the reason for the increment of metal concentration in the rainwater quality and the components of the roof types do not readily leach into the rainwater except on extended contact in the presence of acid rain. Acid rain can be caused by natural and man-made activities (e.g., emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) from factories or vehicles, and these are the main reasons for the contamination of rainwater quality in our environment. The use of WQI was employed in the evaluation of the rainwater quality and the analysed harvested rainwater showed excellent to very poor water quality by the water quality index ratings in both areas, and since, there was no presence of E. coli in the samples assessed, hence, it was concluded that harvested rainwater can be best and suitable for other domestic purposes but must be treated before drinking. It is recommended that there should be proper monitoring of the environment, and adequate measures must be adopted in these areas in order to control atmospheric pollution and anthropogenic emissions.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data discussed in the research work are available in the manuscript and be availed on request. Contact Eno-obong Sunday Nicholas (the Corresponding author) for the data availability on request.

References

Bilal, H. et al. Geospatial techniques for identifying optimal rainwater harvesting sites to enhance agricultural productivity in hyper arid areas. Agric. Water Manage. 318, 109696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2025.109696 (2025).

Nicholas, E. S., Ukoha, P. O. & Ihiedioha, J. N. Comparative assessment of the effect of storage vessels, thatched roof and industrial activity on harvested rainwater quality in South eastern, Nigeria using water quality index. J. Discover Water. 4, 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-024-00081-1 (2024).

Muhammad, S. W. et al. Drought mitigation and livelihood improvement options through rainwater harvesting structures in a rainfed agricultural systems. Agric. Syst. 230, 104469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2025.104469 (2025).

Athauda, A. A. N. S. & Rathnayaka, R. M. Y.D. Rooftop rainwater harvesting systems for enhancing climate resilience in the dry zone of Sri lanka: A case study of Polpithigama division, Kurunegala district. J. Res. Technol. Eng. 6 (3), 214–225 (2025).

Siyu, L. et al. A framework for creating sustainable rainwater harvesting and reuse strategies for urban landscape irrigation in a changing climate. J. Environ. Manage. 392, 126852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126852 (2025).

Siyu, L., Younggu, H. & Anh, H. N. Enhancing the SWAT model for creating efficient rainwater harvesting and reuse strategies to improve water resources management. J. Environ. Manage. 366, 121829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121829 (2024).

Prieto-Jimenez, D. E. R. et al. A multicriteria decision analysis for selecting rainwater harvesting systems in rural areas: a tool for developing countries. Environ. Sci. Pollu Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33734-8 (2024).

Okudo, C. C., Ekere, N. R. & Okoye, C. O. B. Quality assessment of non-roof harvested rainwater in industrial layouts of Enugu state, South east, Nigeria. Appl. Water Sci. 13, 116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-023-01916-3 (2023).

Sanchez, A. S., Cohim, E. & Kalid, R. A. A review on physicochemical and Microbiological contamination of roof-harvested rainwater in urban areas. Sustain. Water Qual. Ecol. 6 (6), 119–137 (2015).

Nicholas, E. S. & Ukoha, P. O. Evaluation of the effect of different conventional roof types and industrial activity on harvested rainwater in Southern Nigeria. J. Discover Water. 3, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-023-00036-y (2023).

RAIN. Rainwater Harvesting Implementation Network, Water Quality Guidelines. Version 1 Amsterdam the Netherlands. www.rainfoundation.org (2008).

Moses, E. A., Uwah, I. & I, Ebong, G. A. Physico-chemical quality of harvested rainwater from some settlements in uyo, Nigeria. Am. Chem. Sci. J. 16 (3), 1–9 (2016).

Nicholas, E. S. & Ukoha, P. O. Analysis of the impact of Cameroun zinc, Stone-coated tiles, asbestos, corrugated iron roofs and galvanized iron tank on harvested rainwater in South-South, rivers state, Nigeria using water quality index. J. Chem. Soc. Nigeria. 49 (1), 039–055. https://doi.org/10.46602/jcsn.v49i1.952 (2024).

Marszalek, A., Affek, K., Zaleska-Radziwill, M. & Dudziak, M. Integrated ozonation and photocatalysis to remove pollutants for reuse rainwater. Sustainability 16, 5352. https://doi.org/10.3390/su 16135352 (2024).

Nnaji, C. C., Chibueze, C. V., Mama, C. N., Alum, O. L. & Afangideh, C. B. Impact of anthropogenic and environmental conditions on surface Run-off quality: A case study of nsukka, Eastern Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-04799-8 (2023).

Makarram, M. M. T. et al. Perception of coastal citizens on the prospect of Community-based rainwater harvesting system for sustainable. Water Resource Manage. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 198 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107176 (2023).

Tikhatri, D. & Bhattarai, S. S. Impact of climate change on water security and endorsing importance of rainwater harvesting technology in Nepal. American J. Environ. Climate (AJEC). 2 (3), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.54536/ajec.v2i3.1643 (2023).

Mazurkiewicz, K., Jez-Walkowiak, J. & Michalkiewicz, M. Physicochemical and Microbiological quality of rainwater harvested in underground retention tanks. Sci. Total Environ. 814, 152701 (2022).

Ombeni, J. M., Malugu, M. T. & William, J. S. M. Estimation of storage tank capacities for different roofing areas for rainwater harvesting in Dodoma urban. Tanzania Tanzan Jour Eng. Technol. 41 (2), 109–120 (2022).

Eruola, A. O. et al. 1., and Qualitative Assessment of the Effect of Thunderstorm on Rainwater Harvesting from Rooftop Catchments at Oke-Lantoro Community in Abeokuta, Southwest, Nigeria. Resources and Environment 2(1), 27–32 (2012).

Uwineza, A. & Irie, M. Flood analysis for estimating the impact of rainwater harvesting system installation using hydrological models. Case study: Nyabugogo valley, Kigali. J. Arid Land. Stud. 32 (S), 145–149 (2022).

Deng, Y. Pollution in rainwater harvesting: A challenge for sustainability and resilience of urban agriculture. Jour Hazard. Mater. Iett. 2, 100037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazi.2021.100037 (2012).

Vlastos, D. et al. Assessment of the toxic potential of rainwater precipitation: first evidence from a case study in three Greek cities. Sci. Total Environ. 648, 1323–1332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.166 (2019).

Villatane, A. B. et al. Microplastics and anthropogenic debris in rainwater from Bahia Bianca. Argentina Heliyon. 9, e17028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17028 (2023).

Ayenimo, J. G., Adekunle, A. S., Makinde, W. O. & Ogunlusi, G. O. Heavy metal fractionation in roof run-off in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Int. Jour Environ. Sci. Technol. 3 (3), 221–227 (2006).

Rao, C. S., Rao, B. S., Hariharan, A. V. L. N. S. H. & Bharathi, N. M. Determination of water quality index of some areas in Guntur district Andhra Pradesh. Int. J. Appl. Biology Pharm. Technol. I (1), 79–86 (2010).

Alum, O. L. & Okoye, C. O. B. Pollution status of major rivers in an agricultural belt in Eastern Nigeria. J. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08366-3 (2020).

TCEQ-Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Harvesting, Storing, and Treating Rainwater for Domestic Indoor Use. (2007). www.tceq.state.tx.us/publicationsAccessed 12 Oct 2010.

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Manual of Standards of Quality for Drinking Water Supplies. New Delhi. (1975).

Anjaneyulu, Y. Introduction to Environmental Science, BSB Publications, India: Sultan Bazar. 685–690, (1994).

Monika, Z., Justyna, Z., Dorota, P. & Daniel, S. The quality of rainwater collected from roofs and the possibility of its economic use. Resources 9 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9020012 (2020).

Owusu, A. & Asante, R. Rainwater harvesting and primary uses among rural communities in Ghana. Jour. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 10(3), 503–11 https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.059 (2020).

Ojo, O. M. Effects of roofing materials on harvested rainwater quality. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 23 (4), 735–738 (2019).

Aladenola, O. O. & Adeboye, O. B. Assessing the potential for rainwater harvesting. Water Resource Management. 24, 2129–2137 (2010).

Mendez, C., Klenzendorf, B. & Asfor, B. The effect of roofing materials on the quality of harvested rainwater. J. Water Res. 45 (5), 2049–2059 (2011).

Emerole, C. O., Emekaraoha, M. & Emerole, C. G. Quality of harvested rainwater in owerri, Imo state, Nigeria. Int. J. Multidisciplinary Curr. Res. 3, 1162–1166 (2015).

Achadu, O. J., Ako, F. E. & Dalla, C. L. Quality assessment of stored harvested rainwater in wukari, North-Eastern nigeria: impact of storage media. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 7 (5), 25–32 (2013).

Ana, A. & Lidija, T. Analysis of basic Physical-Chemical parameters, nutrients and heavy metals content in surface water of small catchment area of Karašica and vuˇcica rivers in Croatia. Environments 5 (20), 1–27 (2018).

Olowoyo, D. N. Physico-chemical characteristics of rainwater quality of Warri axis of delta state in Western Niger delta region of Nigeria. Jour Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 3 (12), 320–322 (2011).

Chukwuma, E. C., Nzediegwu, C., Okpo, F. I. & Ogbu, K. N. Quality assessment of direct harvested rain water in parts of Anambra state, Nigeria. Int. J. Veterinary Sci. 1 (1), 26–30 (2013).

Dinrifo, R. R., Babatunde, S. O. E., Bankole, Y. O. & Demu, Q. A. Physicochemical properties of rainwater collected from some industrial areas of Lagos state Nigeria. Eur. Jour Sci. Res. 41 (3), 383–390 (2010).

Eroksuz, E. & Rahman, A. Rainwater tanks in multi-unit buildings: a case study for three Australian cities. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 1449–1452 (2010).

Waziri, M., Akinnniyi, J. A. & Ogbodo, O. U. Assessment of the physicochemical characteristics of rain and run-off water in university of Maiduguri- Nigeria staff quarters. Am. J. Sci. Industrial Res. 3 (2), 99–102 (2012).

Nigeria Standard for Drinking Water Standard Nigeria standard for drinking water quality (NSDWQ). Nigerian industrial standard NIS-554-2015. Standard Organ. Nigeria, 1–28, (2015). https://africacheck.org/sites/default/files/Nigerian-Standard-for-Drinking-Water-Quality-NIS-554-2015.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for drinking water quality, 4th edition, Geneva. 472–475 [online]. available at http://www.who.int/en.html [accessed on June, 2014] (2011).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Source Water Assessment, USEPA, Office of Water. Retrieved June, (2012). http://water.epa.gov/infrastructure/drinkingwater/sourcewater/protection/sourcewater.assessments.cfm

John-De-Zuane, P. E. Handbook of Drinking Water Quality: Standards and Control (Van nostrand Reinhold, N.Y (1990).

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Method of Analysis, 15th Edition, Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Washington, DC. (1998).

American Public Health Association (APHA). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd Edition, American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association. Water Environment Federation, (2012).

Noori, N. D. Comparative analysis of weighted arithmetic and CCME water quality index Estimation methods, accuracy and representation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 737 (012174). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/737/1/012174 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged the entire staff of the Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Funding

The authors funded this work. No external funding was received from any agency or organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. S. Nicholas: Writing-original draft, Methodology, conceptualization, analysis. C. C. Okudo: Editing, Methodology, conceptualization, analysis. P. O. Ukoha: Writing-review & editing, supervision, validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicholas, Eo.S., Okudo, C.C. & Ukoha, P.O. Water quality index assessment of toxicity in direct and roofs runoff rainwater in industrial and remote areas of Eastern Nigeria. Sci Rep 15, 36068 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19983-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19983-8