Abstract

This study builds a framework for the green transformation of manufacturing from the dual perspectives of “technological empowerment” and “institutional regulation.” It integrates digital technology, environmental regulation, and their synergy. Using panel data from 30 Chinese provinces during 2012–2023, we apply a PVAR model to explore the dynamic transmission paths among these factors and the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing. The results show: (1) Digital technology has a phased effect on transformation: it inhibits in the short term, improves in the mid-term, and promotes in the long term, reflecting an accumulating response mechanism. (2) Environmental regulation mainly drives transformation efficiency in the short term through incentives, but its effect weakens in the long run. (3) A strong synergy between digital technology and environmental regulation has not yet emerged in the medium and long term, and their joint effects remain limited. (4) The main driving force of green and low-carbon transformation comes from internal development momentum. Compared with environmental regulation, digital technology shows much stronger explanatory power, while the marginal contribution of regulation remains small. This study suggests embedding digital tools into regulatory mechanisms, enhancing the long-term incentives of environmental regulation, and promoting cross-regional data integration to build a dual-driven model for green and low-carbon manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Against the backdrop of the “dual carbon” strategy and the accelerated advancement of new industrialization, the deep integration of digital technology and green development has become a critical issue for China in achieving high-quality growth. In April 2025, the Cyberspace Administration of China and other ministries jointly issued the “Key Tasks for Promoting Digital-Green Coordinated Transformation in 2025,” which further emphasizes the importance of synergizing digital technology and environmental regulation to empower green and low-carbon development across industries. On the one hand, digital technology enhances information transmission efficiency, strengthens system coordination capabilities, and reduces transaction costs, thereby providing foundational support for green innovation, environmental governance optimization, and improved resource utilization efficiency1,2,3. On the other hand, green transition imposes higher requirements on governance precision, response efficiency, and institutional flexibility, prompting a shift from traditional regulatory models toward more intelligent, flexible, and collaborative approaches4,5.

China offers an illustrative setting to investigate how digital technology and environmental regulation jointly shape the process of green transformation. As the largest manufacturing economy and one of the top carbon emitters worldwide, China faces both strong domestic imperatives to meet its “dual carbon” goals and the broader challenge of managing industrial upgrading under significant regional disparities. The manufacturing sector contributes a large share of national GDP and energy consumption, making its transition toward low-carbon development both urgent and consequential. By analyzing China’s experience, this study highlights how a large developing economy with uneven technological advancement and complex institutional structures navigates the green transition. The results are also informative for other developing and transitional economies, which encounter comparable trade-offs between digital innovation, environmental sustainability, and industrial restructuring. In this sense, the Chinese case provides broader lessons that enhance the international relevance of the research.

In recent years, the impact of digital technology and environmental regulation on green and low-carbon development in the manufacturing sector has garnered widespread attention in academic circles. Existing studies have explored how digital transformation and regulatory tools influence green transformation from multiple dimensions, such as energy efficiency, environmental performance, and green innovation, and have provided empirical evidence and policy implications regarding the pathways through which green and low-carbon performance is enhanced6,7,8,9. However, from an overall perspective, the current literature still presents three main limitations: First, most studies rely on static regression models, which are inadequate in capturing the time-lagged and stage-specific effects between variables, often neglecting the differential responses of policy and technological shocks across temporal scales. Second, the analysis of digital technology and environmental regulation is often conducted in isolation, lacking systematic identification of their interactive effects in the process of green transformation in manufacturing. Third, there is a lack of studies based on dynamic modeling perspectives to explain the relative importance of variables and to compare their contribution levels, making it difficult to offer clear guidance for policy resource allocation.

In response to the above issues, the main contributions of this study are as follows: First, from the dual perspective of “technological empowerment” and “institutional regulation,” this study constructs a theoretical framework for green transformation that integrates digital technology, environmental regulation, and their synergistic mechanism. This framework highlights how the two drivers promote the efficiency of green and low-carbon transformation in manufacturing through production factor reconfiguration, green technology diffusion, institutional constraints, market incentives, information feedback, and resource allocation pathways. Second, on the empirical side, a PVAR model is established to identify the bidirectional causal relationship and dynamic response paths among the core variables. It further analyzes the asymmetric impact and interaction characteristics of digital technology and environmental regulation on green and low-carbon transformation in manufacturing. Third, building on the theoretical framework and empirical findings, this study contributes by transforming the identified synergistic mechanism between digital technology and environmental regulation into concrete policy implications. Specifically, it highlights how embedding digital tools into regulatory processes and strengthening long-term institutional incentives can operationalize a “dual-driven” model for green and low-carbon manufacturing.

The subsequent sections are organized as follows: Section 2 systematically reviews high-quality literature on digital technology, environmental regulation, and green development, summarizing key findings and identifying research gaps. Section 3 analyzes, at the theoretical level, the mechanism through which digital technology, environmental regulation, and their synergy affect the green and low-carbon transformation of the manufacturing industry. Section 4 describes the model design and research framework, including data sources, indicator selection, and variable measurement methods, and explains the settings and testing steps of the PVAR model. Section 5 presents the empirical analysis, including panel unit root tests, optimal lag selection, Granger causality tests, impulse response function analysis, and variance decomposition, offering a detailed assessment of the interrelationships among the three variables, as well as the timing and contribution of their respective effects on green performance. Section 6 concludes the study and provides policy implications and directions for future research.

Literature review

The promotion mechanism of digital technology for green development

In recent years, academic research on the role of digital technologies in promoting green development has deepened. Existing studies have shown that digital innovation can significantly impact urban green development by optimizing energy structures, upgrading industrial structures, and fostering digital-intelligent integration in cities10,11. At the enterprise level, digital technologies enhance firms’ resource integration capabilities, thereby reducing uncertainty and trial-and-error costs associated with green R&D and encouraging greater investment in green innovation12,13.

From a micro perspective, the digital literacy of top executives improves firms’ strategic flexibility and technological absorptive capacity, which in turn enhances their environmental performance. Moreover, digital technologies can also improve corporate environmental responsibility by strengthening environmental information disclosure and public supervision14,15. In addition, digital transformation has been empirically shown to improve corporate ESG performance, with both formal and informal environmental regulations at the regional level playing a positive moderating role in this mechanism16,17. Song et al. (2024)18, using evolutionary game theory and system dynamics models, emphasized the critical role of the synergy between digital economy and corporate value co-creation in driving green innovation. They also noted that environmental regulation and green subsidies further reinforce this effect when backed by strong policy support. Zhang and Tan (2025)19, based on panel data from 285 prefecture-level cities, found that the “Broadband China” initiative significantly improved urban green total factor productivity. They concluded that digital infrastructure promotes green innovation, optimizes resource allocation, and enhances public governance capacity, thereby enabling this effect to materialize.

The impact mechanism of environmental regulation on green performance

Environmental regulation has demonstrated a significant nonlinear mechanism in promoting green performance20,21, which varies across regulation types and implementation structures. Existing studies have explored regulatory tools from the perspectives of heterogeneity in policy pathways and institutional designs22,23, thereby enriching the theoretical understanding of how environmental regulation drives green performance. For instance, based on data from Chinese listed companies, some studies have shown that environmental regulation can stimulate corporate green innovation activities, indirectly improving operational performance, thereby embodying a so-called “innovation compensation” effect24.

Other research has further suggested that a sound institutional foundation and a well-functioning information disclosure system are conducive to enhancing the long-term and stable effect of environmental regulation on corporate environmental performance25,26. In addition, empirical evidence based on industrial-level data from several provinces has identified the differential impacts of regulatory tools and regional heterogeneity in driving green and low-carbon transitions. Some studies have revealed the existence of an “inverted U-shaped” effect of individual regulatory tools, where excessive intensity may hinder performance improvement. Meanwhile, the interaction of multiple policy instruments (e.g., “command-control and market-based instruments,” or “regulation mix and voluntary mechanisms”) can exert a synergistic effect on promoting industrial green transitions27.

The synergistic mechanism between digital technology and environmental regulation

Against the backdrop of the deep integration of digitalization and green transformation, academic attention has gradually shifted from “unidirectional driving” to “systematic synergy” in exploring the dual relationship between digital technology and environmental regulation. Recent studies increasingly focus on the internal mechanisms and synergistic pathways of digitalization’s impact on green performance, covering resource allocation, policy adaptation, and institutional coordination.

At the enterprise level, the synergy between the digital economy and green finance has been shown to produce a “1 + 1 > 2” effect28. Some studies, based on the “technology–factor–industry” framework, verify that the coordinated development of the digital economy and new quality productive forces is driven by technological innovation, optimized allocation of production factors, and the multi-dimensional interaction of industrial transformation29. Other scholars also reveal that enterprise digitalization and green development coordination levels can be enhanced through optimized resource allocation and cost reduction, thereby improving overall factor productivity and driving production factor restructuring for sustainable value creation30. Digital transformation has also been proven to significantly promote pollution reduction and carbon mitigation synergy effects (SRPC), with the effect being more prominent among enterprises receiving environmental subsidies or classified as state-owned31.

At the regional level, studies focusing on the spatial pattern and coupling mechanisms of digital economy and green innovation collaboration have found that the spatial coordination of the two tends to exhibit a “stepwise decreasing pattern” from the eastern to northeastern, central, and western regions, and that regional imbalance issues may gradually be alleviated over time. Regional disparities have been identified as the main contributors to overall differences32,33.

Other scholars, based on GTWR models, have demonstrated a significant coupling relationship between digital infrastructure and green governance policies. Green finance development, intelligent monitoring systems, and public digital participation are key supporting paths for this coupling effect34. The synergy between digital technology and environmental regulation is also found to promote urban green performance through channels such as industrial structure upgrading, resource reallocation, and enhancement of public environmental participation, with the effect being more pronounced in the eastern region35.

The level of coordination within the entrepreneurial ecosystem has also shown a positive impact on regional green performance, where alignment mechanisms are key driving factors36. Spatial panel model analyses have further revealed significant positive spillover effects in the performance of regional environmental governance stemming from the interaction between environmental regulation and digital development levels in neighboring areas37. Additionally, the synergy mechanism of digital and green development can also contribute to employment growth by enhancing regional innovation and entrepreneurship capacity and the quality of human capital investment38.

In summary, existing academic research on the relationship between digital technology and environmental regulation has gradually formed three relatively clear directions. First, studies explore how digital technologies can optimize resource allocation, strengthen environmental information governance and production organization capabilities, and thereby improve green innovation and environmental performance. Second, research focuses on how environmental regulations promote green transformation through incentives such as encouraging green investment and improving institutional mechanisms like green finance. Third, recent studies have expanded to examine the coordination mechanisms between digital technologies and green development, revealing multiple interactive pathways from firm-level behavior to regional governance. These studies provide both theoretical insights and empirical evidence for understanding the synergy between “technology empowerment” and “institutional coordination” in driving green development. Although the above studies offer valuable inspiration for understanding the multidimensional drivers of green transformation, most findings are still based on static mechanisms focusing on identifying causality or estimating aggregate effects. They lack systematic analyses of the dynamic interactions, lagged effects, and relative contributions of digital technologies and environmental regulation in improving green performance within the manufacturing sector. Therefore, this study introduces a PVAR model to examine, from a dynamic systems perspective, the time-sequenced impact pathways and interaction effects of technological and regulatory factors on the total factor productivity of green manufacturing. It aims to reveal the temporal heterogeneity and coordination potential of these variables across different time horizons.

Theoretical mechanism analysis

The reconfiguration effect of element allocation by digital technology

Digital technology, as an important engine for promoting the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing, is fundamentally reflected in the reconfiguration and optimized allocation of traditional production factors39.

First, digital technology, through the introduction and expansion of data elements, breaks the boundaries and allocation methods of traditional production factors, achieving dynamic linkage and efficient matching between elements. On one hand, digitalization enhances the visibility of information and the transparency of processes in enterprise production and manufacturing, improving the timeliness and accuracy of resource scheduling and production decision-making. On the other hand, through the digital management and integration of traditional elements such as labor, capital, and energy, the efficiency of resource allocation is further optimized40.

Second, digital technology expands the connotation and application boundaries of green and low-carbon elements, enabling new elements such as green technology, green products, and green services to be efficiently integrated into the enterprise production and manufacturing system. For example, digital infrastructures such as industrial internet, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things lower the threshold for the diffusion of green technology and collaborative innovation41, providing support for the flow and integration of green and low-carbon elements within and between enterprises.

Third, digital technology, by breaking the existing structure of element combinations, promotes the reallocation of resources, information, and technology on a larger scale and with higher efficiency, building new momentum for enterprise green development and forming a digital-driven logic for the reconfiguration of green elements.

Therefore, it can be inferred that digital technology contributes to the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing through the mechanisms discussed above. Based on this logic, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Digital technology promotes the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing through production factor reconfiguration, green technology diffusion, and efficiency improvements.

The constraint-and-incentive effect of environmental regulation

Environmental regulation affects the transformation path of green and low-carbon manufacturing through the dual mechanism of “institutional constraints” and “market incentives.” On one hand, command-and-control regulation constructs a rigid constraint framework by setting enterprise emission limits, enforcing mandatory standards, and increasing penalties for violations, thereby compelling enterprises to carry out pollution control and green investment under the pressure of avoiding regulatory risk, thus promoting green transformation of production processes through external institutional constraints42. On the other hand, market-based regulation releases price signals and resource allocation mechanisms through carbon trading, green credit, emission trading, tax incentives, and other means, guiding enterprises to take environmental benefits into account while pursuing economic gains43. This not only enhances the economic incentives for enterprises’ green transformation, but also strengthens their willingness for innovation and green investment44, thereby improving the efficiency of green and low-carbon transformation.

Accordingly, environmental regulation is expected to improve transformation efficiency by providing both institutional constraints and market incentives. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2

Environmental regulation improves the efficiency of green and low-carbon transformation in manufacturing through institutional constraints and market incentives.

Coupling effect of the dual system synergy between digital technology and environmental regulation

As two key driving forces for promoting the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing, the digital technology system and the environmental regulation system are coupled not only through functional complementarity, but also through mutually reinforcing synergy mechanisms.

First, digital technology has enhanced the enforcement effectiveness and feedback efficiency of environmental regulation35. Traditional environmental regulatory policies face problems such as “difficulty in policy implementation,” “high regulatory costs,” and “information asymmetry” in practice, while the introduction of digital technology breaks the information barriers between the government, enterprises, and the public, realizing precise transmission and dynamic supervision of environmental regulation. This not only improves the efficiency of policy implementation, but also reduces the obstacles caused by information asymmetry, thereby enhancing the incentive or punitive effect of environmental regulation.

Second, the feedback from environmental regulation has also shaped the direction and depth of digital technology application. Under the pressure of regulation, enterprises face more complex and stringent policy requirements, which not only forces them to actively adopt digital technology to improve environmental performance, but may also result in allocating more digital resources toward green design, clean production, and other green and low-carbon areas, promoting the transition of digital technology from generalized application to embedded use in green scenarios.

Finally, the coupling of the dual systems of digital technology and environmental regulation forms a synergistic driving system advantage, strengthening the endogenous motivation for the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing. Under a shared goal orientation, the digital system and regulatory system realize coupled coordination through mechanisms such as policy guidance, technological empowerment, information feedback, and resource allocation45, jointly promoting the shift of enterprise green and low-carbon transformation from “external regulation-driven” to “endogenous mechanism-driven.” On one hand, the regulatory system provides directional guidance and normative standards for green transformation, ensuring that the transformation “stays on course”; On the other hand, the digital system provides tools and capabilities, ensuring that the green transformation “moves quickly.” The synergy between the two helps alleviate uncertainties and resource misallocation during transformation, and can improve the systemic efficiency and sustainability of the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing.

Given the complementary and mutually reinforcing effects of digital technology and environmental regulation, it is reasonable to anticipate that their synergy generates stronger and more sustained impacts than either factor alone. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3

The synergy between digital technology and environmental regulation generates stronger and more sustained effects on the green and low-carbon transformation of manufacturing compared with their independent impacts.

The synergistic mechanism between digital systems and regulatory systems is illustrated in Fig. 1, which depicts the theoretical framework guiding this study.

Research design

Data sources and processing

This study selects 30 provincial-level administrative regions in China (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan to ensure data completeness) as the research sample. It constructs a balanced panel dataset spanning 2012–2023 at the provincial level, covering key variables such as digital technology development, environmental regulation efficiency, and total factor productivity (TFP) of green manufacturing. For years with missing data, linear interpolation and moving average techniques are applied to ensure continuity and structural balance of the dataset.

Indicators related to digital technology are mainly derived from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Labor Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook, and China Internet Development Report. Environmental regulation indicators are sourced from the China Environment Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Urban Statistical Yearbook, and the North China University of Technology’s Environmental Law and Regulation Database. Data on the green TFP of manufacturing are primarily obtained from the China Environment Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Labor Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, as well as the EDGAR Carbon Emissions Database.

Although certain indicators are available at the prefecture level, this study adopts provincial-level data for two main reasons. First, provincial statistics provide a longer time span (2012–2023) with consistent coverage of key variables such as digital technology, environmental regulation, and manufacturing performance, while prefecture-level data often suffer from severe missing values, inconsistent statistical standards, and limited availability. Second, provincial-level indicators capture the overall intensity of regional digitalization and regulatory implementation, thereby providing a comprehensive view of macro-level policy and technological drivers. Moreover, the dependent variable in this study—the green total factor productivity (GTFP)—is calculated specifically for the manufacturing sector, ensuring that the analysis reflects the transformation of manufacturing rather than the entire regional economy. Using provincial-level manufacturing data enables us to capture aggregate trends and regional heterogeneity in green transformation across regions. Future research may extend the analysis to prefecture-level or firm-level data to further validate the conclusions.

Selection of indicators

Digital technology

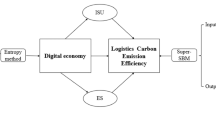

Against the backdrop of promoting governance modernization through digital transformation, quantifying the regional level of digital technology development has become an important component for evaluating new-type productive factors46,47. Unlike traditional measurement methods such as informatization level or internet penetration rate, this study draws on existing research methodologies and indicator selection procedures48,49. From the four dimensions of foundational infrastructure, technological innovation, application scenarios, and diffusion performance, we construct the following evaluation indicator system for the development level of digital technology (Table 1):

In terms of data processing, all indicators were first positively standardized using the min-max normalization method. Then, the entropy method was employed to determine dynamic weights, aiming to eliminate subjective interference and highlight heterogeneity characteristics50,51. Ultimately, the composite index reflects each province’s development level of digital technology across the four stages of foundation, capability, application, and performance. To determine the contribution of each dimension, the entropy method was employed to calculate indicator weights annually. The values reported in Table 1 represent the average weights over the period 2012–2023. This approach ensures that indicators with greater cross-provincial and intertemporal variability are assigned higher weights, thereby enhancing the objectivity and interpretability of the composite digital technology index.

Environmental regulation

To scientifically depict the allocation efficiency between resource input and governance output in the environmental regulation process, this study innovatively introduces the Expected Slack-Based Measure (EBM) model to conduct an in-depth assessment of provincial environmental regulation efficiency. Compared with traditional DEA and SBM models52, the EBM model not only offers a more detailed characterization of input–output slacks during the efficiency calculation process, but also improves upon the conventional DEA model’s inability to differentiate frontier units53, enabling effective ranking even among high-efficiency regions. This significantly enhances the model’s ability to distinguish efficiency levels54 and reflect applied value, making it particularly suitable for evaluating environmental regulation efficiency involving undesirable outputs, as in this study. In summary, unlike conventional DEA models, the EBM approach explicitly incorporates slack variables and undesirable outputs, which allows for a more accurate and policy-relevant evaluation of environmental regulation efficiency under green development constraints.

The variable \(\rho\) represents the overall score of environmental regulation efficiency (objective function). \({\lambda _j}\) denotes the linear combination weight, and \(x,y,b\) represent input factors, expected outputs, and undesirable outputs, respectively. The variables \({s^ - }\), \({s^+}\), and \({s^b}\) are corresponding slack variables (used to capture surplus or insufficiency).

Drawing on relevant studies55,56,57, the model includes associated input-output indicators, which are shown in Table 2. To improve the robustness of the results, this paper uses the MaxDEA9 software to model and calculate the indicators. The final super-efficiency scores obtained are used to reflect the resource allocation efficiency of environmental regulation in the sample provinces, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent coupling coordination analysis with the level of digital technology.

In addition to the EBM-based efficiency index of environmental regulation, this study introduces several proxy indicators to capture the heterogeneity of regulation types and intensity. Specifically, command-and-control regulation (CBR) is proxied by the number of local environmental regulations, market-based regulation (MBR) is proxied by pollution levy (or environmental tax) revenues as a share of GDP, and regulatory intensity (ERD) is measured by the ratio of industrial pollution control investment to GDP. These supplementary variables are incorporated into the robustness analysis to test whether the main conclusions remain valid under different measures of environmental regulation.

Efficiency of green and low-carbon transformation in manufacturing

To evaluate the green development efficiency of China’s manufacturing sector under the combined influence of digital technology and environmental regulation policies58, this study adopts the SBM-ML model incorporating undesirable outputs. The model is applied to 30 provincial-level administrative regions in China over the period 2012–2023, to measure manufacturing Green Total Factor Productivity (MGTFP). Based on the traditional SBM (Slack-Based Measure) framework, this method supports multiple inputs, multiple expected outputs, and multiple undesirable outputs in an integrated manner, effectively addressing the limitations of the traditional directional DEA model in handling slack variables59,60. Moreover, by introducing the ML index, it further enables the dynamic and time-sequential analysis of efficiency.

In this study, “Manufacturing Green Total Factor Productivity (MGTFP)” is defined as an extension of traditional total factor productivity (TFP) that incorporates both expected and undesirable outputs into the productivity measurement framework. Unlike traditional TFP, which only considers inputs such as capital, energy, and labor relative to desired output (e.g., industrial added value), MGTFP explicitly accounts for environmental constraints by integrating undesirable outputs such as CO2emissions, industrial wastewater, SO2, solid industrial waste, and industrial dust. Compared with broader concepts like “green efficiency” or “low-carbon productivity,” MGTFP is operationalized through the SBM-ML model with dynamic decomposition, which allows for a systematic evaluation of resource allocation efficiency, environmental regulation effects, and technological progress within the manufacturing sector. To illustrate the annual dynamics more clearly, Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the national-level average trends of digital technology (DT), environmental regulation (ER), and manufacturing green total factor productivity (MGTFP) from 2012 to 2023.

Referring to the methodologies of Zhang et al. (2022) and Cheng et al. (2022)61,62, the model parameter settings used in this study are shown in Table 3. The input variables include manufacturing fixed capital stock, total energy consumption, and number of employees. The expected output is industrial added value, while undesirable outputs include emissions of carbon dioxide, industrial wastewater, sulfur dioxide, solid industrial waste, and industrial dust (particulate matter), covering five types of pollutants. The model operates under the Variable Returns to Scale (VRS) assumption, allowing for a more realistic reflection of heterogeneity among provinces63. The ML index is decomposed into technical efficiency change (EC) and technological progress (BPC). To ensure comparability, all monetary indicators (including industrial added value) are deflated to constant prices using the GDP deflator, with 2011 set as the base year (MGTFP = 1). This guarantees that MGTFP is calculated on a real-value basis, eliminating distortions from price fluctuations. This study sets 2011 as the base year (with MGTFP = 1) and calculates Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP) for China’s manufacturing sector during 2012–2023 using panel data. To ensure data comparability, all monetary indicators are adjusted to constant prices, and perpetual inventory methods are used to estimate capital stock, with standardized conversions for units across years. According to relevant theoretical and empirical studies, this method demonstrates strong rigor and stability in measuring green efficiency and technological progress64,65, thereby providing reliable data support and methodological foundation for the PVAR framework constructed in this paper based on low-carbon manufacturing.

Model setting and method selection

To further explore the dynamic impact of digital technology development and environmental regulation on the performance of low-carbon transformation in the manufacturing sector, this study constructs a Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR) model to empirically analyze causal pathways and dynamic responses. As an extension of the traditional VAR model, the PVAR model allows for the simultaneous inclusion of individual fixed effects and time effects, thereby enhancing the accuracy and stability of the estimation results66. Furthermore, this method does not rely on prior assumptions regarding causality, nor does it require a clear distinction between endogenous and exogenous variables, making it suitable for capturing the internal interactions and feedback loops among multiple variables.

Additionally, the PVAR model introduces more observational information, increases the degrees of freedom, effectively controls for individual heterogeneity in panel data, and helps uncover the complex dynamic structures among multiple system variables67. Compared with static panel models (e.g., fixed effects), which cannot capture feedback loops, and dynamic GMM models, which mainly handle single-equation dynamics and require strict instruments, the PVAR framework is more suitable here. It treats all variables as endogenous, incorporates individual and time effects, and explicitly models the dynamic interactions among digital technology, environmental regulation, and manufacturing transformation. This makes PVAR the most appropriate method for analyzing their complex, time-lagged synergy.

In the empirical analysis, this study first conducts panel unit root and stationarity tests, followed by estimation of the PVAR model, then impulse response and variance decomposition analysis. The estimation process employs the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to enhance the estimation accuracy and stability. Impulse response functions are used to identify the dynamic effects triggered by shocks to a single variable, revealing the transmission paths and persistence of its influence on other variables. Meanwhile, variance decomposition evaluates the degree of explanation of shocks within the model, further clarifying the relative importance of different shocks68,69. Specifically, this study selects green total factor productivity (GTFP) in the manufacturing industry as the dependent variable, with digital technology level (DT) and environmental regulation efficiency (ER) as the main explanatory variables. The PVAR model is constructed accordingly:

In this model, \({Y_{it}}\) represents a column vector containing three endogenous variables: the level of digital technology, environmental regulation efficiency, and green total factor productivity (GTFP) in the manufacturing sector. \({A_k}\) denotes the coefficient matrix corresponding to the k-th lag, while p indicates the maximum lag order selected for the model. \({\mu _i}\) and \({\lambda _t}\) represent the individual and time fixed effects, respectively, and \({\varepsilon _{it}}\) is the random disturbance term.

Empirical results and discussion

Given that the green total factor productivity (MGTFP) of the manufacturing industry reflects both its low-carbon efficiency and its dependence on technological application and environmental governance, this study sets digital technology development level (DT) and environmental regulation intensity (ER) as explanatory variables. A dynamic panel PVAR model is constructed with MGTFP as the explained variable to depict the interactive influence paths of DT and ER on the green efficiency of manufacturing.

Panel unit root tests

To ensure the robustness and interpretability of the PVAR model estimation results, this study conducts panel unit root tests and performs differencing treatment on the relevant variables. The results show that the green total factor productivity (MGTFP) of the manufacturing industry is stationary in its original form (I(0)), while digital technology development level (DT) and environmental regulation efficiency (ER) are first-order integrated series (I(1)). The detailed test statistics are reported in Table 4, which presents the results of the LLC, Fisher-ADF, and Fisher-PP tests and confirms the mixed integration orders of the variables. Considering that differencing I(0) variables may result in the loss of information—particularly long-term equilibrium information—this study retains MGTFP in its original form and performs first-order differencing on DT and ER (denoted as dDT and dER, respectively), thus forming a mixed-order variable structure for the PVAR model. This approach aligns with mainstream practices in current research. As noted by Love and Zicchino (2006) and Abrigo and Love (2016)70,71, it is acceptable for variables in PVAR applications to be of different integration orders, provided the overall system maintains stability. Therefore, this study ultimately constructs a PVAR model using MGTFP, dDT, and dER, which not only meets the stationarity requirement of the data but also maximally retains the interpretive significance of the explained variables.

Economically, dDT and dER should be interpreted as annual marginal changes rather than absolute levels. Specifically, dDT reflects the incremental improvement of digital technology compared with the previous year, capturing the short-term acceleration of digitalization and technology diffusion. Similarly, dER indicates the marginal tightening or relaxation of environmental regulation efficiency relative to the previous year, reflecting yearly adjustments in enforcement intensity and policy performance.

Determination of the optimal lag order

Before constructing the PVAR model, it is necessary to determine the optimal lag order to ensure that the model can accurately capture the dynamic relationships among the variables. This study adopts the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQIC) to determine the optimal lag order of the model. The results are shown in Table 5. According to the AIC (–18.328112) and HQIC (–18.895592), the model performs best at lag 1. However, when the lag order is set to 2 or 3, the information criteria return non-numeric values (Not a Number) or extremely negative values. This is due to the relatively short time dimension of the panel data used in this study (12 years). This phenomenon is also acknowledged in some existing literature. When a high lag order is selected, the rapid increase in the number of model parameters may lead to a non-invertible covariance matrix, resulting in convergence failure or invalid estimation outcomes, which in turn causes the information criteria functions to fail to compute properly72,73. Therefore, this study selects lag order 1 for model construction and subsequent analysis to ensure the robustness of the model estimation.

PVAR model analysis

Based on the conclusion that the optimal lag order is 1, this study constructs a PVAR(1) model with manufacturing green total factor productivity (MGTFP), digital technology level (dDT), and environmental regulation efficiency (dER) as endogenous variables. The estimation results obtained through the system GMM approach are shown in Table 6.

From the MGTFP equation, the lag term of MGTFP itself (L1.MGTFP) has a significantly positive impact on its current value (coefficient = 0.460, p < 0.05), indicating that MGTFP exhibits strong self-sustainability. The lagged change in digital technology (L1.dDT) has a significantly negative effect on MGTFP (-3.512, p < 0.05), suggesting that in the short term, digital technology advancement may inhibit green total factor productivity in manufacturing due to factors such as resource allocation and investment costs74. Meanwhile, the lagged change in environmental regulation efficiency (L1.dER) has a significantly positive impact on MGTFP (0.311, p < 0.05), indicating that appropriate adjustments in environmental policies can effectively enhance green efficiency in the short term—supporting the “Porter Hypothesis”75.

However, in the two equations involving changes in digital technology level (dDT) and environmental regulation efficiency (dER) as dependent variables, none of the lagged explanatory variables reached statistical significance. This suggests that historical changes in green total factor productivity in manufacturing do not induce short-term feedback on digital technology or environmental regulation adjustments. This result may be interpreted in two ways: on the one hand, improvements in digital technology primarily stem from long-term industrial policy support, fiscal subsidies, and enterprise investment, rather than short-term increases in MGTFP76,77; on the other hand, adjustments in environmental regulation have institutional lags and are mainly driven by central and local government policies, making it difficult to influence green productivity in the short run52,78.

Overall, the results of the PVAR(1) model reveal that there exist significant dynamic interactions among digital technology (DT), environmental regulation (ER), and green total factor productivity (MGTFP) in the manufacturing sector. Specifically, changes in DT and ER have statistically significant but opposite effects on MGTFP, indicating that these two factors play different roles in the process of low-carbon transformation in manufacturing. Meanwhile, the feedback paths among variables are asymmetric—MGTFP does not exhibit significant reverse effects on DT and ER—suggesting structural asymmetry in the internal endogenous system, which highlights the exogenous nature of policy and technological pathways in driving green transformation in manufacturing.

To further verify the stability of the above PVAR(1) model and ensure the validity of impulse response and variance decomposition analyses, this study conducts a characteristic root unit circle test. This method determines whether all the characteristic roots of the system matrix lie within the unit circle, thereby verifying whether the model satisfies the condition for stability79,80. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the companion matrix’s characteristic roots, indicating that all characteristic roots lie within the unit circle, thus confirming that the established PVAR(1) model is stable.

To further verify robustness, we conducted a single-equation System GMM estimation, and the results are reported in Supplementary Table 1. The estimation confirms the persistence of MGTFP and the significantly positive effect of digital technology (dDT), while changes in environmental regulation efficiency (dER) remain statistically insignificant. The diagnostic tests support the validity of the estimation: AR(1) is significant, as expected, and AR(2) is marginally significant, suggesting that the results should be interpreted with some caution but remain within an acceptable range. Both Hansen and Sargan tests fail to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the instruments are valid, although the high Hansen p-value reflects the relatively large number of instruments. Overall, the robustness check suggests that the PVAR model results are reliable. This additional estimation helps to address potential endogeneity concerns, particularly reverse causality and omitted variable bias. By using lagged instruments within the System GMM framework, the robustness of the baseline PVAR results is further reinforced.

Granger causality test

Granger causality tests can reflect the “predictive ability” of each variable in a time series—whether past values can significantly improve the prediction accuracy of another variable—but do not represent true causality mechanisms81,82. Therefore, the Granger causality path in this study serves only as a statistical reference for judging dynamic correlations and potential mechanisms among variables.

Table 7 presents the Granger causality test results based on the PVAR(1) model. The results show that both the digital technology level (dDT) and environmental regulation efficiency (dER) exhibit significant Granger causality with green total factor productivity (MGTFP), with p-values of 0.020 and 0.016 respectively—both statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that the historical data variations of these two variables can statistically predict changes in MGTFP, suggesting that digitization and regulatory optimization may act as important exogenous driving forces in the green transformation of manufacturing. In contrast, MGTFP does not exhibit significant Granger causality on dDT or dER (p > 0.2), implying that MGTFP primarily reflects the impact of institutional and technological changes over time, rather than serving as a reverse driving factor.

Impulse response function

The empirical results of the impulse response functions are reported in Fig. 3, showing the dynamic interactions among DT, ER, and MGTFP.

When dDT is subject to a positive shock from its own unit, it shows a significant positive response in the first period, followed by a gradual decline and approaching zero in the second period. This reflects that digital technology lacks short-term self-reinforcement capability, and its long-term effect is unclear. When dER is subjected to a positive shock from dDT, it shows a clear negative response in the first period and gradually decreases toward zero by the fourth period. This indicates that the negative impact of digital technology on environmental regulation mainly occurs in the early stages, showing a tendency toward a positive response in the mid-to-long term. However, dDT’s response to MGTFP exhibits a significant negative shock in the first period, with the negative effect gradually diminishing, turning to a positive value around the third period, and reaching near zero or slightly positive after the fifth period. This suggests that digital technology exerts a suppressive effect on green total factor productivity in the short term, but as technological dividends align with green production in the medium to long term, the positive impact becomes more evident.

dER’s response to dDT shows a slight positive effect, but with a relatively small amplitude, and the confidence interval gradually crosses zero. This indicates that environmental regulation does not statistically significantly promote digital investment by enterprises. When dER is positively shocked by its own unit, it demonstrates a typical decaying dynamic response path, with the strongest impact in the first period and stabilizing around the third period. This reflects the short-term volatility of environmental policies. Notably, dER’s response to MGTFP shows an immediate positive feedback in the first period, which gradually weakens but remains within the positive response interval, indicating short-term effectiveness with an increasingly diffused impact.

The response of MGTFP to dDT exhibits a “rise-fall-stabilize” pattern. In the first period, a shock to MGTFP rapidly triggers a positive response in dDT, but it quickly turns into a negative response by the second period, reaching a trough in the third period. It then gradually rises and approaches zero. Although the confidence interval is relatively wide, this pattern suggests that MGTFP’s stimulus effect on digital technology in the short term is unstable and may even exhibit a negative feedback response. The response of MGTFP to dER shows a brief positive promotion effect in the first period, a slight decline in the second period, and approaches zero from the third to the tenth period. This indicates that the promoting effect of green total factor productivity on environmental regulation policy is only effective in the short term, while its long-term impact is unclear. In contrast, a shock to MGTFP itself reaches its peak positive value in the first period and then shows a gradual declining trend. However, it remains within the positive range throughout all ten periods, reflecting that MGTFP demonstrates good dynamic stability.

To provide a clearer quantitative perspective, we further summarize the approximate peak (or valley) magnitude and the timing of maximum responses observed in the impulse response functions. The results, reported in Supplementary Table 5, indicate that the negative effect of digital technology on MGTFP reaches its lowest point (around − 0.08) in Period 2 before gradually recovering, while the positive effect of environmental regulation peaks (around + 0.05) in Period 3 and remains above zero throughout the horizon. Meanwhile, MGTFP itself exhibits strong persistence, with a peak in Period 1 that gradually declines but remains positive ( ~ + 0.03) by Period 10. These findings quantitatively confirm the dynamic asymmetry and varying time lags of the effects identified in the IRF analysis.

Variance decomposition

To better identify the sources of fluctuations in each variable and the explanatory power of each variable in the PVAR(1) model described above, this study conducts variance decomposition analysis on dDT, dER, and MGTFP. Table 8 presents the dynamic contribution of different shocks to the forecast error variance of each variable over the next 10 periods, revealing how various shocks influence the dynamics of different variables over time.

Firstly, the fluctuations in MGTFP are mainly driven by its own shocks, maintaining a dominant role throughout the 10-period forecast horizon. In the first period, the explanatory power of MGTFP for its own forecast error variance reaches 95.47%, slightly decreasing to 92.33% by the fifth period and remaining at 92.18% in the tenth period, showing only minor declines. This indicates that MGTFP possesses strong endogenous explanatory power, while the influence of external variables is limited. The changes in MGTFP primarily reflect a “self-driven” characteristic in the model.

Secondly, the explanatory power of dDT for MGTFP is relatively weak but exhibits a certain degree of accumulation. Its contribution rises from 2.55% in the second period to 5.69% in the fifth period, reaching 5.84% by the tenth period, indicating a gradual upward trend. This suggests that while digital technology has limited direct short-term effects on green productivity, its cumulative impulse response gradually becomes apparent in the mid to long term, playing a progressive promoting role.

In contrast, the explanatory power of dER for MGTFP starts low and remains stable at around 1.98% throughout periods 1 to 10. This implies that environmental regulation has limited explanatory power for MGTFP in the model and does not strengthen over time, reflecting that its impulse effects are mainly short-term and lack dynamic accumulation capacity.

As for the other two variables, fluctuations in dDT and dER are predominantly explained by their own shocks. Taking dDT as an example, over 96% of its forecast error variance is self-explained across 10 periods (ranging from 96.62% to 96.64%), indicating that digital technology development during the sample period is primarily driven by internal factors, with minimal external disturbances. Similarly, fluctuations in dER are also largely self-explained, with the 10-period ratio stabilizing between 84.56% and 94.91%, suggesting that environmental regulation is relatively weakly influenced by external factors in the model framework.

Robustness test

To further ensure the robustness of the empirical findings, this study supplements the baseline PVAR analysis with alternative measures of environmental regulation that capture regulatory heterogeneity and intensity. Specifically, command-and-control regulation (CBR) is proxied by the number of local environmental regulations, market-based regulation (MBR) is proxied by pollution levy (or environmental tax) revenues as a share of GDP, and regulatory intensity (ERD) is proxied by the ratio of industrial pollution control investment to GDP. The PVAR model is re-estimated by replacing the EBM-based efficiency index with these alternative indicators. The results (reported in Supplementary Table 2) show that the main conclusions remain qualitatively unchanged: digital technology continues to exert a short-term negative effect on MGTFP but a positive effect in the long run, while environmental regulation—regardless of type or intensity—plays a facilitating role in green and low-carbon transformation. These robustness checks confirm that the baseline findings are not sensitive to the specific measure of environmental regulation, thereby strengthening the reliability of the empirical results.

To address concerns that the composite index of digital technology may mask heterogeneous effects across sub-dimensions, the PVAR model was re-estimated by substituting four disaggregated indicators: foundational infrastructure (DT₁), technological innovation (DT₂), application scenarios (DT₃), and diffusion performance (DT₄). The results (Supplementary Table 3) again confirm the robustness of the baseline findings. All four sub-dimensions exhibit significant short-term inhibitory effects on MGTFP, but environmental regulation remains significantly positive, and MGTFP maintains strong persistence.

To further examine the synergistic effect between digital technology and environmental regulation, this study incorporates an interaction term (dDT × dER) into the PVAR model. The estimation results (Supplementary Table 4) show that the interaction term is positive and statistically significant (coefficient = 0.150, p < 0.1), indicating that the joint improvement of digital technology and environmental regulation yields incremental gains in manufacturing green total factor productivity (MGTFP), beyond the independent effect of each factor. Moreover, the coefficients of digital technology and environmental regulation remain consistent in both sign and significance compared with the baseline results, confirming that the observed synergy is not an artifact of model specification but reflects substantive complementarity and mutual reinforcement between the two factors. This finding provides robust empirical support for the proposed “dual synergy mechanism.”

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Main conclusions

This study, from the dual perspective of “technological empowerment” and “institutional regulation,” constructs a theoretical framework for green transformation that encompasses the paths of digital technology development and environmental regulation, as well as their synergistic mechanisms. It emphasizes the coupling effect and influence pathways between digital systems and regulatory systems. The framework systematically explains how digital technology stimulates green potential in manufacturing through production factor restructuring and green technology diffusion, while environmental regulation guides enterprises toward low-carbon behavior through institutional constraints and market incentives. Together, they form a synergistic driving force and jointly enhance the efficiency of green and low-carbon transformation in manufacturing. At the empirical level, based on panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2012 to 2023, this study adopts a PVAR(1) model to analyze the time-sequence interaction relationships among digital technology (dDT), environmental regulation (dER), and manufacturing green total factor productivity (MGTFP). The main conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

Digital technology and environmental regulation play a significant leading role in driving MGTFP. Granger causality test results indicate that both digital technology and environmental regulation exhibit strong causal relationships with MGTFP, suggesting that these two external variables possess predictive and explanatory power during the transformation toward green manufacturing. In contrast, the reverse causality from MGTFP to dDT and dER is not statistically significant, confirming that MGTFP mainly acts as a response variable within the model structure. This empirical evidence statistically supports the conclusion that digital technology and environmental regulation serve as exogenous variables that positively influence green productivity.

-

(2)

The impact of digital technology follows a phased pattern of “short-term suppression followed by mid-to-long-term promotion.” dDT has a significant short-term negative impact on MGTFP due to initial negative shocks. However, the effect gradually weakens and shifts to a positive influence, reflecting a clear “delayed promotion” pattern. This indicates that digital technology may initially face issues such as mismatch with production or lag in adoption, leading to short-term inefficiencies, but its promotional effect becomes more evident as it matures.

-

(3)

The policy effects of environmental regulation are primarily short-term and lack long-term explanatory power. dER shows a short-term positive impact on MGTFP, but this effect rapidly converges to zero. The PVAR(1) results suggest that environmental regulation policies mainly produce short-term tuning effects and lack stable long-term driving forces. The variance decomposition results show that the explanatory power of dER for MGTFP stabilizes around 1.98% throughout the 10 periods, indicating limited fluctuation and contribution. This implies that for continuous improvement of green productivity, more coordination in long-term regulatory strategies is needed.

-

(4)

Green total factor productivity in manufacturing exhibits strong endogenous characteristics. Variance decomposition results show that MGTFP’s own shocks consistently explain over 92% of its variance, reflecting its strong internal dynamic stability. This implies that the evolution of green productivity is predominantly driven by historical inertia and endogenous factors, while external variables have limited explanatory power. However, the effectiveness of policy and technology in boosting green productivity may still be underestimated in early stages of adoption.

-

(5)

The self-dynamics of digital technology and environmental regulation are relatively stable, with minimal influence from external variables. dDT and dER both exhibit over 96% self-explanatory power, indicating that their fluctuations are mainly driven by internal mechanisms. This reflects that while digitalization and regulation have certain effectiveness in the short term, their mutual interaction is still at a nascent stage, and a high-level dynamic coordination mechanism has not yet been formed in the long term.

Policy recommendations

To better leverage the synergistic role of digital technology and environmental regulation in promoting the low-carbon transformation of manufacturing, this study proposes the following policy recommendations based on the above empirical results and conclusions:

-

(1)

Strengthen the Guiding Role of Digital Technology in the Green Transformation of Manufacturing. The findings indicate that digital technology has a lagged but positive effect on green total factor productivity, suggesting it holds significant potential for medium- and long-term improvement. Therefore, efforts should be made to accelerate the construction of digital infrastructure, improve digital transformation in manufacturing, and implement supportive policies for digital upgrading. This includes promoting applications of AI, the Industrial Internet, and intelligent manufacturing technologies in emission-reduction scenarios to enhance the technical content and system integration of green productivity improvements. At the regional level, the differentiated deployment of digital infrastructure should be promoted to enable embedded applications of digitalization in key areas of manufacturing, such as energy consumption management, carbon emission monitoring, and pollution source tracing. At the same time, policy tools such as fiscal guidance, financial incentives, and platform support could be considered to steer local manufacturing actors to shift their digital investment logic from “efficiency and cost reduction” to “supporting green and low-carbon goals,” thereby alleviating the issues of delayed responses and marginal volatility commonly observed in the early stages of digital empowerment for green manufacturing transformation.

-

(2)

Enhance the Sustained Driving Force of Environmental Regulation and Strengthen Medium- and Long-Term Incentives. On one hand, a long-term incentive mechanism should be established, such as tax reductions or exemptions based on carbon performance, green credit systems, and carbon trading quota allocation, to guide long-term green investments by manufacturing enterprises. On the other hand, emphasis should be placed on the digitalization of policy enforcement, using big data and the Internet of Things to improve the precision and flexibility of regulatory policies. This will enhance enterprises’ responsiveness and willingness to comply with environmental regulations. At the same time, environmental regulatory policies should be further optimized in terms of stability, incentive design, and contextual adaptability. A performance-oriented regulatory assessment mechanism could be improved, and a diversified toolkit combining “information disclosure + market-based incentives + flexible enforcement” could be established to enhance manufacturers’ willingness to respond to green initiatives and to broaden their strategic choices for transition paths. In regions with significant differences in energy structures and industrial types, the differentiated and region-specific implementation of regulatory policies may also be considered.

-

(3)

Promote the construction of a collaborative governance mechanism between digital technologies and environmental regulation, and leverage the synergistic advantage of the “Technology–Institution” dual-engine driving model. Although both currently show positive impacts on MGTFP, they lack long-term interaction effects. It is recommended to strengthen the mechanism of “technological empowerment of regulation” by promoting interdepartmental collaboration and information sharing among environmental protection, industry, and technology authorities. This would enhance the implementation effectiveness of environmental regulation through digital means and help establish a new “digital + green” integration-driven model. Meanwhile, at the policy design level, efforts should be made to coordinate digitalization strategies with green governance policies and to strengthen cross-departmental and cross-level policy coordination. At the level of governance implementation, it is advisable to establish data-sharing mechanisms within regional digital platforms for manufacturing, and to promote pilot projects that integrate digital supervision with environmental law enforcement, thereby facilitating an intelligent upgrade in environmental governance capacity. In addition, the policy feedback mechanism concerning the involvement of digital technologies in environmental regulation needs to be further reinforced to ensure the long-term stability of their synergistic effects, thus laying a governance foundation for green and high-quality development in the manufacturing sector.

To further enhance the applicability of the policy implications, this study extends the discussion to account for heterogeneity across firms and regions. Specifically, differentiated recommendations are proposed for enterprises of varying ownership structures and industrial orientations. For example, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) may prioritize compliance assurance and technological upgrading in line with national carbon reduction strategies, whereas small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) require greater financial support, technical assistance, and incentive mechanisms to overcome cost constraints. Moreover, high-emission industries should focus on pollution abatement and cleaner production, while low-carbon or emerging sectors are encouraged to integrate digital technology with green innovation to consolidate their comparative advantages. At the regional level, policy design should recognize differences in economic development and industrial composition—promoting tailored environmental and digital transformation strategies that strengthen local pathways toward sustainable manufacturing.

Research limitations and future research directions

The limitations of this study and the directions for future research are as follows:

-

This study is based on provincial-level panel data at the empirical level, which can reflect the evolutionary trends of regulatory policies and digital technologies at the regional level. However, it is difficult to reveal the actual transmission mechanisms at the micro-enterprise level or to examine behavioral heterogeneity among firms in responding to regulations or applying technologies. Future research could integrate micro-level survey data or firm-level databases to conduct multi-layered mechanism analysis.

-

Future research can be further expanded in three directions. First, the internal structure of the coordination mechanism can be examined in more depth by introducing more refined indicators such as the intensity index of environmental regulatory policies and the penetration rate of digital technologies, in order to depict the interactive evolution between digital elements and regulatory instruments. Second, in the spatial dimension, possible regional spillover effects or cross-regional coordination effects of digital technologies and environmental policies can be explored. Methods such as spatial PVAR models may be employed to identify the diffusion mechanisms of such policies. Third, from a theoretical perspective, the framework of how digital technologies empower green institutions and how the two coordinate can be further developed, with a focus on the boundary conditions and transmission mechanisms of institutional change involving technological intervention. Through these extensions, it is expected that the dynamic patterns of the “Technology + Institution” synergy in driving the regional manufacturing sector’s green transition under the context of high-quality development can be further revealed.

-

Furthermore, this study also acknowledges limitations in terms of external validity and generalizability. The empirical results are derived from provincial-level data of China’s manufacturing sector, which may not be directly applicable to other sectors such as services or energy-intensive industries, or to different institutional environments outside China. Regional heterogeneity within China—for instance, disparities in digital infrastructure, regulatory enforcement, and industrial structure—also implies that the observed mechanisms may vary across provinces. Therefore, the conclusions of this study should be regarded as context-specific. Future research could enhance external validity by conducting cross-sectoral comparisons, examining heterogeneity across regions with varying industrial compositions, and carrying out international comparative studies to test the robustness of the identified mechanisms under diverse institutional contexts.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- DT:

-

Digital technology level

- dDT:

-

The first-differenced digital technology level

- ER:

-

Environmental regulation efficiency

- dER:

-

The first-differenced environmental regulation efficiency

- MGTFP:

-

Green Total Factor Productivity of Manufacturing Industry

References

Liu, X., Liu, F. & Ren, X. Firms’ digitalization in manufacturing and the structure and direction of green innovation. J. Environ. Manage. 335, 117525 (2023).

Wang, M. & Teng, W. Digital innovation and firm environmental performance: the mediating role of supply chain management capabilities. Front. Psychol. 13, 897080 (2022).

Li, S. et al. How does the innovation of digital and green technology integration promote corporate environmental performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 99, 104035 (2025).

Deng, T., Zhang, K. & Shen, Z. J. M. A systematic review of a digital twin city: A new pattern of urban governance toward smart cities. J. Manage. Sci. Eng. 6 (2), 125–134 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Digital government and corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 104379 (2025).

Hu, J., Sun, Q. & Wang, W. The role of green and digital technology convergence on carbon emission reduction: evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1490657 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Digital technology, green innovation, and the carbon performance of manufacturing enterprises. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1384332 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Digital economy, environmental regulation and corporate green technology innovation: evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (21), 14084 (2022).

Zhao, X. & Qian, Y. Does digital technology promote green innovation performance?. J. Knowl. Econ. 15 (2), 7568–7587 (2024).

Huang, J., Chen, X. & Zhao, X. How digital technology reduces carbon emissions: from the perspective of green innovation, industry upgrading, and energy transition. J. Knowl. Econ. 1–33 (2024).

Xiao, Y. et al. Digital economy and green development: empirical evidence from china’s cities. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1124680 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Assessing the effect of urban digital infrastructure on green innovation: mechanism identification and spatial-temporal characteristics. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 11 (1), 1–14 (2024).

Yu, J. & Hu, W. The impact of digital infrastructure construction on carbon emission efficiency: considering the role of central cities. J. Clean. Prod. 448, 141687 (2024).

Jiang, F. Digital transformation and green innovation: the mediating role of green management disclosure and the moderating role of institutional pressure. J. Gen. Manage. 03063070241308100. (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Digital transformation and environmental information disclosure in china: the moderating role of top management team’s ability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 33 (8), 8456–8470 (2024).

Huang, C. Digital transformation and corporate ESG performance: research based on a capability-motivation dual framework. PloS One. 20 (6), e0325295 (2025).

Wang, J. Digital transformation, environmental regulation and enterprises’ ESG performance: evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 32 (2), 1567–1582 (2025).

Song, G., Wang, F. & Dong, F. Can digital economy foster synergistic increases in green innovation and corporate value? Evidence from China. PLoS One. 19 (6), e0304625 (2024).

Zhang, X. & Tan, Y. Digital empowerment: unlocking the’synergy barrier’of government-enterprise-public air pollution control. Energy Rep. 13, 4846–4865 (2025).

Liu, G. & Guo, L. How does mandatory environmental regulation affect corporate environmental information disclosure quality. Finance Res. Lett. 54, 103702 (2023).

Xie, R., Yuan, Y. & Huang, J. Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on green productivity: evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 132, 104–112 (2017).

Wang, X. & Shao, Q. Non-linear effects of heterogeneous environmental regulations on green growth in G20 countries: evidence from panel threshold regression. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 1346–1354 (2019).

Zheng, Y., Zhou, Z. & Zhou, F. The Non-Linear effect of dual environmental regulation on urban green total factor productivity: evidence from 284 cities in China. Sustainability 16 (12), 4894 (2024).

Feng, L. et al. Dynamic correlation of environmental regulation, technological innovation, and corporate carbon emissions: empirical evidence from China listed companies. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–17 (2025).

Hu, J. et al. Environmental information disclosure and firms’ green total factor productivity: evidence from new ambient air quality standards in China. Atmosphere 16 (2), 155 (2025).

He, G., Jiang, H. & Zhu, Y. The effect of digital technology development on the improvement of environmental governance capacity: A case study of China. Ecol. Ind. 165, 112162 (2024).

Jingrong, D. et al. Analysis of the influence and coupling effect of environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 25873 (2024).

Wang, R. & Zhao, W. Synergistic dance of digital economy and green finance on carbon emissions: insights from China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 22 (3), 213–229 (2024).

Jin, W. et al. Digital economy, green finance, and carbon emissions: evidence from China. Sustainability 17 (12), 5625 (2025).

Chen, D. et al. The impact of Digital–Green synergy on total factor productivity: evidence from Chinese listed Companies. Sustainability 17 (5), 2200 (2025).

Chong, Y. et al. Digital transformation and synergistic reduction in pollution and carbon Emissions——An analysis from a dynamic capability perspective. Environ. Res. 261, 119683 (2024).

Bai, D. et al. Impact mechanisms and Spatial and Temporal evolution of digital economy and green innovation: A perspective based on regional collaboration within urban agglomerations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 207, 123613 (2024).

Liu, Y., Li, J. & Li, P. Understanding the coupling coordination between the digital economy and High-Quality development in henan, China. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 9 (1), 1491–1499 (2024).

Shi, Y. & Yang, B. The coupling and coordinated development of digital finance and green finance under the vision of dual carbon and the examination of carbon emission reduction effect. Sustainable Futures. 7, 100217 (2024).

Xiufan, Z., Shi, Y. & Meng, L. Research on the mechanism and path of the coupling of digital technology and environmental regulation to promote urban green efficiency. Sustainable Cities Soc. 116, 105906 (2024).

Guo, Y., Zhang, K. & Xu, J. Coupling coordination degree of entrepreneurship and green development with digital transformation in China. Digit. Econ. Sustainable Dev. 3 (1), 1–18 (2025).

Yu, T. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution and drivers of coupling coordination between digital infrastructure and inclusive green growth: evidence from the Yangtze river economic belt. J. Environ. Manage. 376, 124416 (2025).

Li, Q., Ge, J. & Fan, H. Unveiling the impact of synergy between digitalization and greening on urban employment in China. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 27773 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. How does digital transformation drive green total factor productivity? Evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 406, 136954 (2023).

Yang, G. et al. Impact of digital transformation on enterprise carbon intensity: the moderating role of digital information Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (3), 2178 (2023).

Xu, B. et al. Digital governance and the low-carbon transition: evidence from double machine learning. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 12 (1), 1–14 (2025).

Zhou, C., Han, Y. & Zhang, R. Can command-and-control policy drive low-carbon transition in energy-intensive enterprises?-a study based on evolutionary game theory. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1247780 (2023).

Wei, T., Zhu, Q. & Liu, W. The effect of Market-Based environmental regulations on green technology Innovation—The regulatory effect based on corporate social Responsibility. Sustainability 16 (11), 4719 (2024).

Liu, J. H. et al. Impact of heterogeneous environmental regulation on manufacturing sector green transformation and sustainability. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 938509 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Can the synergy of digitalization and greening boost manufacturing industry chain resilience?? Evidence from china’s provincial panel Data. Sustainability 16 (22), 9866 (2024).

Xin, Y. et al. Measurement of the integration level between the digital economy and industry and its impact on energy consumption. Energy Econ. 126, 106988 (2023).

Elfaki, K. E. & Ahmed, E. M. Digital technology adoption and globalization innovation implications on Asian Pacific green sustainable economic growth. J. Open. Innovation: Technol. Market Complex. 10 (1), 100221 (2024).