Abstract

Addressing the issue of sealing failure in liquid hydrogen triple-offset butterfly valves within rocket fuel delivery systems under ultra-low temperature conditions due to insufficient cold shrinkage compensation capability, this paper first proposes a soft-sealing elastic compensation structure. Its sealing performance is evaluated using a thermo-mechanical coupling method. Secondly, sensitivity analysis using the Spearman method identifies key optimization variables: radial offset distance De, third offset angle α, sealing surface width B, and sealing surface interference T. The optimization objectives are the maximum contact stress P1max and average contact stress P1ave during forward sealing, and the maximum contact stress P2max and average contact stress P2ave during reverse sealing. Finally, an optimal Latin hypercube sampling method is used to construct the sample space, and a high-precision RBF surrogate model combined with the NSGA-II algorithm is employed to find excellent Pareto front solutions. After optimization, the Maximum contact stress of the butterfly valve sealing structure during forward sealing decreased by 23.43%, and the average contact stress decreased by 22.41%; during reverse sealing, the Maximum contact stress increased by 51.07%, and the average contact stress increased by 48.83%. The optimized butterfly valve sealing structure achieves reliable bidirectional sealing under liquid hydrogen ultra-low temperature conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of the economy and society, the conflict between economic growth demands and ecological environmental protection has gradually deepened1,2. As one of the most promising clean energies of the 21 st century, hydrogen energy has become a core pathway for the global energy structure’s low-carbon transition due to its characteristics of high energy density, abundant reserves, and zero carbon emissions3,4,5. In hydrogen energy utilization, liquid hydrogen (LH2) is widely used due to its lower required storage pressure and high transportation efficiency6,7. Especially in the aerospace field, LH2 is used as rocket propellant due to its extremely high specific impulse and non-toxic, non-polluting nature. In rocket LH2 fuel delivery systems, butterfly valves serve as key fluid control and shut-off devices, often requiring bidirectional sealing functionality. Their sealing reliability directly impacts system safety. With the continuous development of aerospace technology, the demand for high-performance LH2 butterfly valves is increasing.

Numerous scholars have conducted in-depth research on the sealing performance of cryogenic valves. Zhang et al.8 tested the sealing performance and compressive strain of pneumatic cryogenic control valves at liquid nitrogen temperatures under different sealing stresses. Lin et al.9 established a multi-physics simulation model for the sealing system of a cryogenic ball valve based on fluid-structure interaction (FSI) theory, deeply investigating the influence of the flowing medium on its sealing performance. Kwak et al.10 used the finite element method (FEM) to focus on the influence of key structural parameters of the laminated seal in a cryogenic triple-offset butterfly valve on contact surface pressure. Li et al.11 used FEM to study the temperature distribution of the long-neck bonnet in a cryogenic ball valve and optimized the drip plate structural parameters. Ma et al.12 addressed the issue of uneven stem deformation in ultra-low temperature environments, proposing an improved displacement adjustment compensation method for ultra-low temperature valve sealing by combining the IDA method and FEM. Hou et al.13 used FEM and nonlinear theory to study the sealing performance of a new spherical seal composed of silicone rubber and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) under low-temperature and high-pressure conditions. However, existing research on valve cryogenic sealing performance mainly focuses on conventional cryogenic fields like LNG and liquid nitrogen, while research on nonlinear sealing problems of valves in the ultra-low temperature environment of LH2 is still relatively scarce.

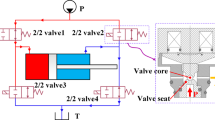

Multi-objective optimization (MOO) can optimize multiple conflicting objectives in engineering design and is an effective method for solving complex engineering problems14,15,16. When the improvement of one objective inevitably leads to the deterioration of others, a Pareto optimal solution can be obtained17,18. All Pareto solutions constitute the Pareto front, from which engineers need to select based on requirements and trade-offs. Corbera S et al.19 proposed an advanced genetic algorithm based on Pareto dominance, performed MOO on the stress, weight, and flow rate of a butterfly valve disc, and proposed an optimal design scheme. Zhong et al.20 used the NSGA-II genetic algorithm for MOO of the dynamic characteristics and structural parameters of a high-speed quick-closing valve. Li et al.21 optimized a molten salt check valve disc based on a thermo-fluid-mechanical coupled topology optimization method, improving the valve’s dynamic performance. Li et al.22 optimized the opening and closing times of a pneumatic pilot-operated high-speed on/off valve using the NSGA-II genetic algorithm, reducing the valve’s operating times. Yu et al.23 used the NSGA-II genetic algorithm to optimize the opening response time and energy loss of a high-speed solenoid valve. Currently, research on valve optimization mostly focuses on lightweight design, reducing opening/closing times, improving sealing performance, and enhancing dynamic characteristics. Research on optimizing the sealing performance and thermo-mechanical structural strength of ultra-low temperature valve sealing structures is relatively insufficient.

In summary, this paper addresses the leakage problem in triple-offset butterfly valves within rocket fuel delivery systems under ultra-low temperature conditions caused by insufficient cold shrinkage compensation capability. A soft-sealing elastic compensation structure composed of a metal seat, PCTFE (Polychlorotrifluoroethylene) soft seat, elastic compensation ring, and other components is designed. Thermo-mechanical coupled nonlinear finite element analysis (FEA) is performed on the butterfly valve sealing structure. To ensure the valve’s bidirectional sealing performance, the sealing structure is optimized. Parametric modeling is used to determine the MOO design variables, and sensitivity analysis on the initial parameters is conducted using the Spearman method. Based on an RBF approximate model and the NSGA-II genetic algorithm, MOO of the forward and reverse sealing performance of the butterfly valve sealing structure is performed. This study provides a theoretical basis and design reference for improving the sealing reliability of butterfly valves under extreme cryogenic LH2 conditions.

Structure of cryogenic liquid hydrogen triple-offset butterfly valve

Liquid hydrogen is transported via tankers, stored in highly insulated fuel tanks, conveyed through cryogenic pipelines and butterfly valves to cryogenic pumps, converted to gaseous hydrogen via heat exchangers, and finally sent to the combustion chamber. The main process flow of the rocket fuel delivery system is shown in Fig. 1.

The core function of the cryogenic LH2 butterfly valve is to precisely control the flow of the medium in the pipeline. Under specific conditions, the valve must achieve fast and reliable pipeline isolation. Its sealing reliability is a key indicator for ensuring the safe operation of the entire delivery system. The main design parameters of the cryogenic butterfly valve in the rocket fuel delivery system are listed in Table 1, and the material parameters of the main components are listed in Table 2.

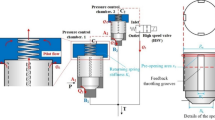

Conventional triple-offset butterfly valves use metal-to-metal sealing pairs. Such sealing structures are prone to cold shrinkage deformation under ultra-low temperatures, leading to uneven contact between sealing surfaces and failure to form the necessary specific sealing pressure. Therefore, an innovative soft-sealing elastic compensation structure is designed, as shown in Fig. 2. It mainly consists of a metal seat, PCTFE soft seat, elastic compensation ring, seat retainer ring, and other components. PCTFE is selected for the soft seat due to its excellent cryogenic properties, including low thermal conductivity, low cold flow, and maintained flexibility at ultra-low temperatures, which are crucial for effective sealing in LH2 environments. The elastic compensation ring has a certain interference fit and is embedded within the PCTFE soft seat.

Figure 3 illustrates the working principle of the soft-sealing elastic compensation structure. During forward sealing (flow direction closing the disc against the seat), the disc is pushed forward by medium pressure, compressing the soft seat. The elastic compensation ring maintains its resilience. During reverse sealing (flow direction trying to open the disc away from the seat), the soft seat contracts due to low temperature. Medium enters the interior of the soft seat through holes in the metal seat. The elastic compensation ring expands under medium pressure, providing compensation to the PCTFE soft seat, ensuring sealing performance. This structure can reduce cold shrinkage deformation of the sealing assembly. However, when the temperature is extremely low, the PCTFE soft-sealing material hardens, affecting its deformation and compensation effectiveness. Therefore, further optimization of the soft-sealing elastic compensation structure is necessary to ensure the bidirectional sealing performance of the triple-offset butterfly valve.

Numerical simulation analysis

Theoretical analysis

Heat transfer theory analysis

In steady-state heat transfer problems, temperature change is independent of time:

Discretizing the object into elements, the temperature field \({T^e}(x,y,z)\) of an element is expressed as an interpolation function of nodal temperatures:

Where \(S(x,y,z)\) is the shape function matrix, and \(z_{T}^{e}\) is the nodal temperature vector:

Where \(T_{1} ,T_{2} , \cdot \cdot \cdot ,T_{n}\) is the nodal temperature value.

he annular gap between the bonnet and stem is simplified in the heat transfer model as a natural convection heat transfer problem in a closed cavity. In the heat transfer model, the annular gap between bonnet and stem is simplified and viewed as a problem of natural convective heat transfer in a closed cavity. The natural flow of fluid in this gap is determined by the \(G{r_\delta }\) (Grashof Number)24 of the length characterized by the thickness of the gap:

Where g is the acceleration due to gravity; av is the volume thermal expansion coefficient of the fluid; Δt represents the temperature difference passing through the gap; δ is the characteristic length; v represents the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

When the temperature difference \(\Delta t\) on both sides of the gap closure interlayer is small and Grδ << 2680, the natural convection effect in the gas medium is weak, and the gas heat transfer in the gap mainly considers heat conduction and heat radiation. Since the radiative heat transfer is proportional to the fourth square of temperature, it is negligible when the temperature difference is very small. For the heat transfer analysis of the annular air insulation, it can be equated to the steady-state thermal conductivity problem of a single-layer cylinder, which is:

Where A is the heat transfer area perpendicular to the heat flow direction; \(\lambda\) is the thermal conductivity; \(\varepsilon\) is the air layer thickness.

Relationship between valve cryogenic shrinkage and temperature gradient

Under ultra-low temperatures, material shrinkage can lead to sealing failure, jamming, or structural damage in valves. Given the thermal expansion/contraction properties of metals, the relationship between cryogenic shrinkage and temperature gradient can be quantified using the thermal expansion coefficient formula.

Linear expansion coefficient αt:

Let \({l_{{t_2}}}\), \({l_{{t_1}}}\) be the component lengths at temperatures t2, t1 respectively. Integrating Eq. (6) gives:

Ultimately:

Let Δt = t2-t1, As the ultra-low temperature medium flows in, the temperature continuously decreases (Δt < 0), Expanding the term \({e^{{\alpha _t}\left( {{t_2} - {t_1}} \right)}}\) in Eq. (8) using Taylor series:

Substituting Eq. (9) into Eq. (8) and neglecting higher-order terms:

LH2 butterfly valves are typically designed at room temperature but used under cryogenic conditions. Therefore, using room temperature (20 ℃) as the reference temperature, the radial and axial shrinkage at the LH2 temperature range (−253 ℃) can be calculated based on the thermal expansion formula, providing a theoretical basis for designing the clearance fits between components of the cryogenic butterfly valve.

Calculation of required specific sealing pressure for valve

Valve sealing performance can be characterized by the specific sealing pressure between the sealing pair. The calculated specific pressure value should be greater than the required specific pressure qMF and less than the allowable specific pressure value [q] of the sealing surface Material. For a sealing pair composed of PCTFE and metal, the allowable specific pressure is 37 MPa. The formula for the required specific pressure is25:

Where P is the valve nominal pressure; bM is the sealing surface width; m and n are coefficients related to the sealing surface material. For PCTFE, m = 1.8, n = 0.9. The calculated required specific pressure is 4.30 MPa.

Model simplification and meshing

To ensure computational efficiency without compromising accuracy, the model is reasonably simplified. Straight pipe sections equal to 5 times the nominal diameter are added upstream and downstream of the butterfly valve to realistically simulate its operating state. Hexahedral-dominant meshing is used for the sealing contact region, while adaptive meshing techniques are applied to other components. To ensure result accuracy, the influence of mesh quantity and quality on calculation results must be balanced. Mesh independence verification is shown in Table 3. When the mesh element count of the triple-offset butterfly valve FE model increases from 2,650,862 to 3,105,435, the Maximum stress value increases from 196.57 MPa to 201.42 MPa (2.47% increase). When increasing from 3,105,435 to 3,745,361 grids, the Maximum stress increases from 201.42 MPa to 213.96 MPa (6.23% increase). Increasing further to 4,085,695 grids raises the Maximum stress to 215.73 MPa (0.83% increase). Finally, increasing to 4,364,546 grids results in a Maximum stress of 217.82 MPa (0.97% increase). Considering both calculation accuracy and solving efficiency, the FE model mesh element count is determined as 3,745,361. The mesh model of the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve is shown in Fig. 4.

Load and boundary condition settings

Thermo-mechanical coupling analysis is used to analyze the sealing of the triple-offset butterfly valve. For the temperature field: The inlet end of the valve body in contact with the fluid is subjected to the medium temperature of −253℃. The upper part of the drip plate is set for natural convection with air (heat transfer coefficient 10 W/(m²·℃), ambient temperature 22℃). The surface below the drip plate is treated as adiabatic. After solving the temperature field, the results are coupled to the structural field. In the structural analysis: The inlet end face of the pipe is constrained in displacement. A medium pressure of 2 MPa is applied to the valve body parts in contact with the fluid. A closing torque of 850 N⋅m is applied to the top of the stem. Due to the interference between the soft seat and the disc, their contact status is set to “Adjust to touch” with a frictional contact relationship (friction coefficient 0.2).

Finite element analysis

Temperature field analysis

As shown in Fig. 5, during forward sealing, the low-temperature zone of the valve is Mainly concentrated in the parts directly contacted by the medium. The temperature changes Little along the flow direction but shows a significant gradient along the axial direction of the stem, increasing uniformly. The temperature at the bottom of the stuffing box is 15.64℃, meeting the requirement of being above 0℃ for ultra-low temperature environments. Figure 6 shows that the temperature field distribution and trend during reverse sealing are essentially the same as during forward sealing. The temperature at the bottom of the stuffing box is 15.65℃, also meeting the requirement.

Thermo-mechanical coupling analysis for forward sealing

Figure 7 shows the contact stress distribution contour for the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve under forward sealing. Under the combined effects of medium temperature, pressure, and the soft-sealing compensation structure, the contact stress distribution on the sealing surface is relatively uniform. However, the Maximum contact stress value at the edge of the sealing surface is 48.10 MPa, exceeding the allowable specific pressure (37 MPa) of the sealing pair material, which can easily cause damage.

Thermo-mechanical coupling analysis for reverse sealing

Figure 8 shows that the Maximum contact stress value on the sealing surface is 19.58 MPa, located in the lower transition region. The contact stress distribution is uneven, with clearly identifiable weak sealing areas, failing to meet sealing requirements.

Comparative analysis of bidirectional sealing performance

As shown in Fig. 9, to deeply investigate the sealing performance of the sealing pair under different conditions, contact stress information from different regions of the sealing surface is monitored. The sealing ring surface is uniformly divided into three equal parts along the flow direction: the large diameter, medium diameter, and small diameter of the sealing ring. Contact stresses are uniformly extracted circumferentially at nodes on the large, small, and medium diameter paths.

As shown in Fig. 10, after uniformly extracting contact stress points along the sealing surface: it is found that when the Forward Sealing, the medium diameter circumferential contact stress shows symmetrical distribution above and below the 90°~270° Line. Along 0°~180°, it is smaller on the left side and larger on the right. The peak contact stress occurs at 30° in the upper transition region. The small diameter circumferential contact stress is larger on the left and smaller on the right along 0°~180°, changing relatively smoothly, with a peak at 225° in the lower transition region. The large diameter circumferential contact stress shows the same distribution pattern as the small diameter, approximately symmetrical along the 0°~180° Line, with the peak occurring at 270° in the straight-face region. During Reverse Sealing, the medium diameter circumferential contact stress changes more drastically, being smaller in the tapered-face region. The peak occurs at 15° in the upper transition region. The small diameter circumferential contact stress is symmetrical along the 90°~270° Line, with a peak at 30° in the upper transition region. The stress amplitude changes significantly in the tapered-face region, and there are areas of zero contact stress in the tapered face, indicating poor sealing. The large diameter circumferential contact stress distribution is similar to the medium diameter, with a peak at 345° in the upper transition region.

Through the above analysis, the forward and reverse sealing performance of the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve differs significantly. Forward sealing can form a sealing band, but the maximum contact stress exceeds the allowable specific pressure of the sealing material, risking damage. During reverse sealing, influenced by the disc cone angle, weak sealing areas exist in the tapered-face and straight-face regions, preventing the formation of an effective sealing band, resulting in poor sealing performance. Optimization is needed by changing parameters such as the disc cone angle, soft seat structural dimensions, and triple-offset structure parameters.

Multi-objective optimization of lh2 triple-offset butterfly valve sealing structure

Multi-objective optimization design method

Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) is used to sample the design variables of the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve sealing structure and calculate the simulation response values. Based on the NSGA-II algorithm, MOO design of the sealing structure is performed to obtain optimal structural dimensions satisfying bidirectional sealing performance. The optimization flowchart is shown in Fig. 11.

Parametric modeling

Design variables

The overall model of the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve is established. Design variables are parameterized by defining equations in the dimension parameters. The sealing structure optimization parameters are shown in Fig. 12, and the symbol mapping relationships for each design variable are listed in Table 4.

The design variables for the sealing structure are:

Objective functions

Reducing the maximum contact stress (P1max) and average contact stress (P1ave) during forward sealing, and increasing the maximum contact stress (P2max) and average contact stress (P2ave) during reverse sealing are selected as optimization objectives.The objective functions can be expressed as:

Among them, qMF<P1ave, P1max, P2ave, P2max< [q], qMF=4.3 MPa, is the necessary specific pressure of the sealing surface of the butterfly valve, and [q] = 37 MPa, which is the allowable specific pressure value of the sealing surface material of the butterfly valve.

Constraints

During the optimization process, based on assembly process requirements, dimensional fit relationships for the soft seat and valve body, and incorporating engineering design experience for triple-offset butterfly valves, reasonable upper and lower limits are set for the optimization parameters. The determined value ranges are shown in Table 5.

Mathematical model

The MOO mathematical model for the triple-offset butterfly valve sealing structure is:

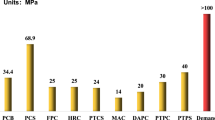

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis evaluates the degree of influence of input variables on output responses in optimization design. When there are many initial design variables affecting the sealing performance of the LH2 butterfly valve, each variable has a different weight of influence. Therefore, sensitivity analysis is performed on the design variables before constructing a high-precision surrogate model. By quantifying the degree of influence of parameters on the optimization objectives, key parameters with significant influence weights are screened as optimization variables. This effectively reduces the computational cost and complexity of the optimization design. 100 sets of experimental samples are designed, and sensitivity analysis yields the sensitivity of each input parameter to the maximum/average contact stresses for forward/reverse sealing, as shown in Fig. 13.

α and T have a significant influence on the reverse average contact stress response variable. B shows high sensitivity regarding its influence weight on the forward average contact stress. De is the radial offset distance. The variables Dh and H have the smallest influence weights on the sealing performance output responses. Therefore, De, α, B, and T are selected as the final optimization design variables.

Design of experiments (DOE)

The Isight multi-disciplinary optimization platform offers various DOE methods, the most common being orthogonal arrays, Latin hypercube design (LHD), and optimal Latin hypercube design (OLHD)26. OLHD, as an efficient method for multi-dimensional space sampling, overcomes the distribution discreteness defects of traditional random LHD through intelligent optimization algorithms. This method dynamically adjusts sample point positions through mathematical optimization iteration, ensuring uniform and dense coverage in high-dimensional variable spaces, effectively improving the space-filling and balance properties of the samples. In engineering applications, OLHD significantly reduces computation time and improves design space exploration efficiency due to its ability to quickly generate high-quality test samples. Furthermore, the sample sets constructed by this method can more accurately capture the complex mapping relationships between input factors and response variables27.

Using the DOE module, experimental design is performed for the sealing structure design variables. To comprehensively explore the design space and obtain better solution domains, OLHD is used to extract 200 sample points, ensuring uniform distribution within the variable space. The actual output response values for each sample point are calculated using FEM software. Sample points and their actual output response values are partially shown in Table 6.

RBF surrogate model establishment and evaluation

RBF surrogate model establishment

The surrogate model between the design variables and the target responses is constructed using the Radial Basis Function (RBF), whose basic form is:

where x represents the input variables; ci denotes the center of the i-th sample point; ϕ is the radial basis function, selected as the Gaussian function; and wi is the corresponding weight coefficient.

The response relationship between design variables and objective functions obtained based on the constructed surrogate model is shown in Fig. 14.

Distribution plots of design variables and output response data. (a) the response surface of De and B to P1max. (b) the response surface of B and α to P1max. (c) The response surface of α and T to P1ave. (d) the response surface of B and T to P1ave. (e) The response surface of De and α to P2max. (f) the response surface of α and B to P2max. (g) The response surface of De and T to P2ave. (h) the response surface of B and T to P2ave.

De is positively correlated with P1max. B is negatively correlated with P1max. Compared to α, B has a smaller influence on P1max. α is positively correlated with P1max. P1ave is positively correlated with both α and T. T has a smaller influence on P1ave. P1ave is negatively correlated with B. α has a very small influence on P2max. De is approximately linearly positively correlated with P2max. The interaction between these two variables is not obvious. B is approximately positively correlated with P2max. P2ave is approximately positively correlated with De and T. B has an insignificant influence on P2ave.

Surrogate model accuracy verification

50 sample points are randomly selected from the DOE sample points for cross-validation. Comparing the FEM simulation values with the RBF surrogate model predicted values effectively assesses the fitting accuracy. The resulting output response error characteristic analysis is shown in Fig. 15. The RBF surrogate model has the highest fitting accuracy for P2max and the lowest for P2ave, but all R² values are greater than 0.9, meeting engineering accuracy requirements.

Multi-objective optimization of sealing performance

NSGA-II algorithm

NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II), a classic algorithm in the field of MOO, ensures convergence through fast non-dominated sorting (classifying the population into hierarchically prioritized Pareto front layers) and an elitism preservation strategy. It uses a crowding distance comparison operator to maintain population diversity28. This prevents the algorithm from stagnating due to population convergence and guides the optimization results to gradually converge to the true Pareto front, enhancing the algorithm’s solution accuracy and efficiency for MOO problems29,30,31. Key parameter settings for this optimization design are: population size 20, iteration count 20, crossover probability 0.9, mutation probability 0.1. The NSGA-II algorithm is used for MOO design of the LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve sealing structure, finally obtaining the Pareto front solutions of the RBF surrogate model. As seen in Fig. 16, the solutions in the Pareto front set are not only uniformly distributed across different value ranges but also show good continuity with smooth transitions between points. Optimal solution points satisfying the three output responses exist within the space.

The internal sealing structure model before optimization is shown in Fig. 17. After optimization and rounding, the internal sealing structure model is shown in Fig. 18.

FEA of optimized sealing structure

Thermo-mechanical coupled FEA is performed again on the optimized cryogenic LH2 triple-offset butterfly valve sealing structure using the same settings as Sect. 3. Figure 19 shows the contact stress distribution contour on the sealing surface during reverse sealing after optimization. A sealing band with pressure greater than the required specific pressure is formed, and the contact stress distribution is more uniform than before optimization. The Maximum contact stress is 36.83 MPa, located on the straight-face side, which is below the allowable specific pressure of the soft-sealing material, avoiding crushing.

Figure 20 shows that the optimized Maximum reverse sealing contact stress is 29.58 MPa, located on the straight-face side, below the allowable specific pressure. The contact stress shows weaker sealing on the tapered-face side and better sealing on the straight-face side. Even in the weaker tapered-face region, a sealing band with pressure greater than the required specific pressure is formed.

A comparison of sealing performance output responses before and after optimization is shown in Table 8. The bidirectional sealing performance of the triple-offset soft-seated butterfly valve is improved after optimization. During forward sealing, the Maximum contact stress decreased by 23.43% compared to before optimization, and the average contact stress decreased by 22.41%. During reverse sealing, the Maximum contact stress increased by 51.07% compared to before optimization, and the average contact stress increased by 48.83%.

Figure 21 shows the circumferential contact stress change on the forward sealing surface before and after optimization. The contact stress distribution around the circumference is more uniform, and the variation amplitude is smoother. Contact stress is higher in the tapered-face and straight-face regions and lower in the upper and lower transition regions. The minimum contact stress is greater than the required specific pressure, forming an effective sealing band. The contact stress distributions along the three paths are generally consistent, showing symmetry along the horizontal axis. The maximum contact stress does not exceed the material’s allowable specific pressure.

Figure 22 shows the circumferential contact stress change on the reverse sealing surface before and after optimization. After optimization, the contact stress on different sealing ring diameters changes, and the distribution around the disc circumference is more uniform, with a smoother variation amplitude compared to before optimization. The contact stress distribution is symmetric along the horizontal plane, being smaller in the tapered-face region. The large diameter region can form an effective sealing band with pressure greater than the required specific pressure.

Conclusion

This paper addressed the problems of sealing surface crushing during forward sealing and failure to achieve reverse sealing in LH2 triple-offset butterfly valves within rocket fuel systems under ultra-low temperature conditions caused by material cold shrinkage. A novel soft-sealing elastic compensation structure was designed, and thermo-mechanical coupled FEA was performed on this structure. To ensure the excellent performance of the soft-sealing elastic compensation structure, MOO research was conducted on the soft-sealing elastic compensation seat. Parametric modeling of the butterfly valve seat was performed, and sensitivity analysis on the initial parameters was conducted using the Spearman method, ultimately determining the MOO design variables. OLHS was used to construct the sample space. Based on an RBF surrogate model and the NSGA-II genetic algorithm, the maximum and average contact stresses on the seat sealing surface during both forward and reverse sealing of the butterfly valve were optimized.

(1) Thermo-mechanical coupled analysis of the LH2 butterfly valve sealing structure revealed that during forward sealing, contact stress distribution was relatively uniform, forming a sealing band. However, the Maximum contact stress of 48.10 MPa exceeded the allowable specific pressure (37 MPa) of the sealing Material, posing a risk of crushing. During reverse sealing, the Maximum contact stress was 19.58 MPa, distribution was uneven, and a clear weak zone existed in the middle of the tapered face, preventing effective sealing.

(2) The optimization objectives were defined as minimizing the maximum contact stress P1max and average contact stress P1ave during forward sealing, and maximizing the maximum contact stress P2max and average contact stress P2ave during reverse sealing. Sensitivity analysis using the Spearman method selected the radial offset De, third offset angle α, sealing surface width B, and sealing surface interference T as the final optimization variables.

(3) OLHS was used to construct sample points and calculate simulation response values. The RBF surrogate model was chosen to replace the FEA model of the soft-sealing elastic seat. P1max showed a positive correlation with De and a, and a negative correlation with B, with B having a smaller influence. P1ave showed a positive correlation with α and T, and a negative correlation with B, with T having a smaller influence. P2max showed an approximate positive correlation with B and an approximate linear positive correlation with De, while α had very little influence, and the interaction between variables was insignificant. P2ave showed an approximate positive correlation with De and T, and the influence of B was not significant.

(4) The NSGA-II genetic algorithm was used to optimize the designed seat structure. After optimization, the Maximum contact stress on the sealing surface during forward sealing is reduced to 36.83 MPa, which is below the allowable bearing pressure of the sealing surface Material, a decrease of 23.43% compared to before optimization. The average contact stress has decreased by 22.41%, avoiding the risk of sealing surface collapse and resulting in a more uniform stress distribution. During reverse sealing, the Maximum contact stress increased to 29.58 MPa, a 51.07% improvement, and the average contact stress increased by 48.83%. Stress distribution is more uniform than before optimization, forming an effective sealing band with pressure greater than the required specific pressure.

In summary, this research can be applied to the bidirectional sealing failure analysis and structural optimization design of cryogenic soft-seated butterfly valves. It provides a theoretical basis and engineering practical reference for the design of high-safety valves in rocket fuel systems, significantly contributing to ensuring the safe operation of aerospace equipment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, T. T. et al. Hydrogen liquefaction and storage: recent progress and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 176, 113204 (2023).

Yu, Z. J., Wu, X. T., Wei, B. H., Sun, Y. H. & Wang, H. Optimization of the future hydrogen supply chain for china: A new design of hydrogen storage and transportation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 105, 701–718 (2025).

Aziz, M. Liquid hydrogen: a review on liquefaction, storage, transportation, and safety. Energies 14, 5917 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Green hydrogen: A promising way to the carbon-free society. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 43, 2–13 (2022).

Lebrouhi, B. E., Djoupo, J. J., Lamrani, B., Benabdelaziz, K. & Kousksou, T. Global hydrogen development-A technological and geopolitical overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 47, 7016–7048 (2022).

Ahmad, S. et al. Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and utilization for energy sector: a current status review. Energy Storage. 101, 113733 (2024).

Jiang, Z., Pan, Q., Xu, J. & Fang, T. Current situation and prospect of hydrogen storage technology with new organic liquid. Hydrogen Energy. 39, 17442–17451 (2014).

Zhang, N., Li, Q., Li, Q., Hu, Z. J. & Hu, K. Seat tightness of pneumatic cryogenic control valve. Sci. China-Technollogical Sci. 56, 2066–2069 (2013).

Lin, Z. H., Lu, J. J., Li, J. Y. & Qian, J. Y. Fluid dynamics and contact stress on hard sealing surface analysis of LNG cryogenic ball valve. ASME-Fluids-Engineering-Division Summer Meeting (FEDSM). Electr Network, AUG10–12 (2021).

Kwak, H. S., Seong, H. & Kim, C. Design of laminated seal in cryogenic triple-offset butterfly valve used in LNG marine engine. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 20, 243–253 (2019).

Li, S. X., Lei, Y., Xu, J. J. & Lou, Y. P. Analysis of influencing factors for temperature of large diameter cryogenic valve and its optimization. International Conference on Design, Manufacturing and Mechatronics (ICDMM2015). Adv. Sci. Technol. Ind. Res. Ctr. 7–18, (2015).

Ma, J. W. et al. An improved displacement adjustment method for overlarge deformation of valve at the cryogenic temperatures. Cryogenics 133, 103702 (2023).

Hou Yongjun; Tang Qian. Wu zhixing; Liu xiaoming. Structural design and performance analysis of a deep-water ball joint seal. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 17, 224–232 (2018).

Kalita, K. et al. Multi-objective exponential distribution optimizer (MOEDO): a novel math-inspired multi-objective algorithm for global optimization and real-world engineering design problems. Sci. Rep. 14. (2024).

Jiang, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, D. & Shi Ling. Online Pareto optimal control of mean-field stochastic multi-player systems using policy iteration. Sci. China-Information Sci. 67, 140202 (2024).

Kumar, S. et al. Patel, pinank. A two-archive multi-objective multi-verse optimizer for truss design. Knowl. Based Syst. 270, 110529 (2023).

Sharma, S. & Kumar, V. A. Comprehensive review on Multi-objective optimization techniques: past, present and future. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 29, 5605–5633 (2022).

Ma, H. P., Zhang, Y. J., Sun, S. Y., Liu, T. & Shan, Y. A comprehensive survey on NSGA-II for multi-objective optimization and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 15217–15270 (2023).

Corbera, S., Olazagoitia, J. L. & Lozano, J. A. Multi-objective global optimization of a butterfly valve using genetic algorithms. ISA Trans. 63, 401–412 (2016).

Zhong, Q., Wang, J. X., Xu, E. G., Yu, C. & Li, Y. B. Multi-objective optimization of a high speed on/off valve for dynamic performance improvement and volume minimization. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 37, 435–444 (2024).

Li, S. X., Ma, T. Q., Shen, H. Y., Yu, M. Y. & Lei, Z. J. Analysis and optimization of the opening dynamic characteristics of molten salt check valves for concentrating solar power. Applide Sciences-basel. 13, 3146 (2023).

Li, T., Zhang, Y. T., Liang, Y. X., Yang, Y. & Jiao, J. Multiobjective optimization research on the response time of a pneumatic pilot-operated high speed on/off valve. Int. J. Appl. Electromagentics Mech. 65, 109–127 (2021).

Yu, Z. Q., Yang, L., Zhao, J. H. & Grekhov, L. Research on Multi-Objective optimization of High-Speed solenoid valve drive strategies under the synergistic effect of dynamic response and energy loss. Energies 17, 300 (2024).

Liu, J., Zhao, C. J., Liu, H. & Lu, W. Q. Numerical study of laminar natural convection heat transfer from a hemisphere with adiabatic plane and isothermal hemispherical surface. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 131, 132–143 (2018).

Li, S. & Zhang, B. Yin huiquan; Zhang jianzheng. Multi-objective optimization of sealing structure of high temperature tri-eccentric butterfly valve. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 51, 107–113 (2023).

Yin, Q., Wu, G. H., Sun, G. & Gu, Y. Multi-objective orbital maneuver optimization of multi-satellite using an adaptive feedback learning NSGA-II. Swarm Evol. Comput. 93, 101835 (2025).

Al-Majali, B. H. & Zobaa, A. F. Analyzing bi-objective optimization Pareto fronts using square shape slope index and NSGA-II: A multi-criteria decision-making approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 272, 126765 (2025).

Deb, K. & Pratap, A. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6, 182–197 (2002).

Xu, Y., Gai, Y. F., Li, H. T. & Han, Q. H. Multi-objective shape-section optimization of free-form latticed shells using the RBF-NSGA-II algorithm. Thin-Walled Struct. 200, 111918 (2024).

Ren, J., Zhu, H. W., Wang, H., Zhao, C. F. & Zhong, J. L. Multi-objective structural optimization of VL seal ring based on insight. 6th Annual International Workshop on Materials Science and Engineering (IWMSE). 17–18, (2020).

Li, W. H., Yao, X. Y., Zhang, T., Wang, R. & Wang, L. Hierarchy ranking method for multimodal multiobjective optimization with local Pareto fronts. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 27, 98–110 (2023).

Funding

The authors thank the supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Research Project: 51569012), the Double First-Class Key Program of Gansu Provincial Department of Education; Gansu Province Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 22CX8GA125) and Gansu Provincial Department of Education (Industrial Support Plan Project: 2025CYZC-048).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuxun Li: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision.Bojiang Yin: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Cong Wei: Conceptualization, Methodology.Wei Li: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation.Lingxia Yang: Conceptualization, Software, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Yin, B., Wei, C. et al. Structural analysis and multi-objective optimization of sealing structure for cryogenic liquid hydrogen triple-offset butterfly valve. Sci Rep 15, 36059 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20095-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20095-6