Abstract

Sunscreens, a primary defense against ultraviolet (UV) radiation, use UV filters to mitigate the harmful effects of UVA and UVB radiation, including DNA damage, skin aging, and cancer. However, organic UV filters like benzophenones, oxybenzone, sulisobenzone, and PABA are persistent pollutants, posing environmental risks due to their incomplete removal by conventional wastewater treatment. This study investigates the encapsulation of hazardous UV filters inside a stable belt[14]pyridine nanobelt to facilitate their removal through host-guest interactions. The higher values of interaction energies (Eint) of the designed host-guest complexes ranging from − 13.70 to −26.11 kcal/mol, ensure the stability of the complexes. Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis reveal the significant role of highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the host nanobelt towards the HOMO and LUMO of complexes, which is confirmed via density of states (DOS) analysis. Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis determines the direction of charge transfer, i.e., from the host towards guest species in all complexes. The highest magnitude of NBO charge is observed for sulisobenzone@belt complex, i.e., 0.022|e|. Electron density difference (EDD) analysis visually illustrate the accumulation of charge density over the guest in all the complexes, i.e., a validation of the direction of charge transfer predicted via NBO analysis. The results of non-covalent interaction index (NCI) and quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analyses reveal that the host-guest complexes are stabilized via van der Waals interactions, and a greater number of bond critical points (BCPs) are found for sulisobenzone@belt i.e., 15. Moreover, the recovery time decreases with increasing temperature and is highest for the complex with greater Eint i.e., 1.4\(\:\times\:\)107 s (at 298 K) for oxybenzone@belt complex. Overall, the study aims to design stable host-guest complexes for effective encapsulation of harmful UV filters, in order to reduce their harmful effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sun protection through the use of sunscreens tends to reduce the occurrence risks of various skin disorders like sunburns, skin cancer and premature aging by absorbing, reflecting or scattering UV radiations1,2. UV filters are commonly used in sunscreen formulations, lowering the risk of the harmful effects of UVA (320–400 nm) and UVB (290–320 nm) light3,4. Studies have shown that the continuous exposure of skin to UVA and UVB radiations has posed significant health risks including thickening of the epidermis and DNA damage, respectively5. Sunscreens are composed of multiple components, usually containing one or more UV filters along with other substances like preservatives and surfactants etc. UV filters are classified on the basis of their nature into organic and inorganic UV filters. Another classification of UV filters is based on the specific range of UV radiations which they absorb or block, i.e., UVA filters, UVB filters and broad-spectrum UV filters6,7,8. The chromophore is an important component in the structure of UV filters. UV filters feature an aromatic ring and a carbonyl group either directly attached to the aromatic core or connected through a carbon-carbon double bond, creating multiple conjugated π-electron systems. The toxicity of the UV filters is determined by their aqueous solubility or hydrophilicity. Moreover, the lipophilic compounds show greater tendency towards bioaccumulation. Organic UV filters are categorized based on their chemical structure, i.e., benzophenones, triazines, derivatives of aminobenzoic acid, salicylic acid, cinnamic acid, benzylidenecamphor, dibenzoylmethane, benzimidazole, and benzotriazole9,10.

Sunscreens enter the wastewaters both directly and indirectly through bathing, swimming and industrial disposal11,12. In a wastewater treatment plant in China, benzophenone, oxybenzone and ethylhexyl salicylate-type UV filters were detected with concentrations ranging from 21 to 2128 ng L− 113. Similarly, in a wastewater treatment plant in United Kingdom, higher concentrations of oxybenzone, octinoxate and octocrylene were determined up to 13,248 ng L− 114. Similar results were obtained through other studies conducted in USA, Japan, Korea and Switzerland15. Filtration, adsorption and other conventional biological processes are already being employed for the degradation and removal of sunscreen filters from wastewaters. The limitations associated with the use of these conventional methods is the low removal efficiency due to the conversion of organic pollutants from one form to the other. Moreover, the literature reveals that the benzophenone and its derivatives can not be efficiently removed from wastewaters through conventional methods8,16,17,18.

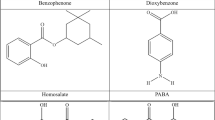

Supramolecular host-guest chemistry is a rapidly developing field, emphasizing the importance of molecular interactions in biomedical and material science applications. These systems rely on non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions, to form well-defined complexes between host molecules (e.g., crown ethers, cyclodextrins, calixarenes, metallacycles, nanobelts, cucurbit[n]urils) and guest compounds19,20,21,22,23. In our study, six host-guest complexes are designed based on belt14pyridine (host) and organic UV filters (guests). The host nanobelt is composed of 14 pyridine units, providing enough space (cavity) for the guests to be encapsulated inside. The theme of the study is the removal of hazardous pollutants through encapsulation inside the macrocyclic belt14pyridine. Moreover, the guests selected in the study are benzophenone, dioxybenzone, homosalate, oxybenzone, PABA, and sulisobenzone, respectively. The study aims the efficient removal of the organic UV filters through encapsulation mechanism. Moreover, the study highlights the nature and strength of interactions between the host and guest species and determination of energy gaps and charge transfer in the complexes.

In supramolecular chemistry, various macrocyclic molecules such as cyclodextrins24, cucurbiturils25, calixarenes26, and resorcinarenes27 have been extensively explored for their host-guest complexation capabilities. While these systems, often composed of bridged repeating units, have shown utility in encapsulating a range of small molecules, typically have non-uniform cavity and imbalanced interactions. In contrast, belt-like macrocycles, such as belt14pyridine, offer a rigid architecture with well-organized internal functionalities and extended π-conjugation, making them exceptional hosts for guests capable of π–π stacking interactions. Moreover, its inherent symmetry, stability, and a limited number of unique structural conformations, constrains guest orientation options and simplifies the modeling and interpretation of host-guest interactions. Keeping all these points in mind, belt14pyridine is selected for the study, instead of other commonly used hosts.

Benzophenone (BP) is an aromatic compound that is used in sunscreens and personal care products as UV filter. BPs can be released into aquatic environments either through recreational activities or from industrial wastewater treatment plants. These compounds pose risks to aquatic ecosystems through hormonal disruption and genotoxicity, affecting both the environment and marine life28. Dioxybenzone, a benzophenone derivative (benzophenone-8) is an aromatic hydrocarbon used as a broad-spectrum UVA and UVB filter in sunscreen formulations. When discharged into aqueous environments, it reacts with chlorine forming harmful by-products. Furthermore, oxybenzone cause toxic reactions in corals and fish in aquatic ecosystems, resulting in reef bleaching to mortality. The North American contact dermatitis group evaluated the products used in sunscreens as a reason of contact dermatitis, of which the oxybenzone was found to be a major allergen (i.e., 70.2%)29. The exposure of oxybenzone (OBZ), i.e., another benzophenone derivative (benzophenone-3) to water bodies has been shown to disrupt metabolic and hormonal pathways in aquatic animals, including changes in lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and behavioral changes, leading to mortality and developmental concerns. Similarly, OBZ affects aquatic plants and algae, inhibiting their growth, altering cellular structure, and reducing photosynthetic activity, with varying degrees of toxicity across different species of plants30.

Sulisobenzone (benzophenone-4), a broad-spectrum sun protection, when discharge into the environment cause potential environmental hazards including oxidative damage, hormonal disruption, and growth inhibition in species like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Daphnia magna18,31. Homosalate or homomenthyl salicylate is a salicylic acid derivative, UVB filter, whereas para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) is aminobenzoic acid derivative. Both homosalate and PABA have shown negative effects on aquatic ecosystems. PABA causes disruption in photosynthetic processes of algae as well as oxidative stress in aquatic organisms. Zhang et al. theoretically investigated the photodegradation of PABA by dissolved oxygen. The study reveals that 1O2 efficiently oxidizes PABA through H abstraction and decarboxylation32. Moreover, the study conducted by Ge et al. provides theoretical and experimental insights into the nitrate-induced photo transformation of benzophenones in aqueous ecosystems33. On the other hand, the homosalate is related to bioaccumulation, endocrine disruption, and toxic effects on marine life, including corals and fish, impairing their growth and reproduction34,35,36. Several approaches are reported in literature for removal of these contaminants from the water bodies.

The organic UV filters can not be efficiently removed from wastewaters by conventional approaches. Several advanced techniques such as membrane separation37, bioremediation38, photodegradation, advanced oxidation processes and adsorption have been employed for the degradation of organic UV filters in water bodies39. Membrane separation technology plays a significant role in the removal of contaminants, particularly UV filters, from wastewater. Among several approaches, reverse osmosis (RO) and nanofiltration (NF) reveal higher efficiency, with RO achieving up to 99% removal, but these methods are more energy-intensive. Hybrid systems like membrane bioreactors (MBRs) involve physical filtration along with biological degradation, offering removal efficiencies as high as 96% for compounds like octocrylene and benzophenone-3 through mechanisms involving sludge adsorption. Adsorption techniques, employing materials like powdered activated carbon (PAC), also show high efficacy (> 95%) for removal of UV filters, employing mechanisms such as hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions39. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), further enhance removal efficiencies (> 98%) by generating reactive oxygen species that degrade contaminants into less harmful by-products40. The photodegradation offers additional pathways for breakdown via direct or indirect photolysis. Comparatively, bioremediation and phytoremediation provide environmentally friendly alternatives by utilizing microorganisms or plants to degrade or absorb these pollutants, but their mechanisms are complex and dependent on various physicochemical factors. Despite these factors, all these processes have some limitations, such as high energy demands, incomplete degradation, or dependence on specific environmental conditions. So, there is a growing need for the development of such methods that can effectively bind and remove these contaminants.

Methodology

This work is based entirely on theoretical modeling using density functional theory (DFT)41. The DFT calculations are performed using ORCA 6.042. The molecular structures of the sunscreen compounds (guests) and belt14pyridine host structure are drawn using GaussView 5.043. Six host-guest encapsulated supramolecular complexes are designed in this study. The host molecule is a pyridine belt composed of 14 pyridine units, i.e., belt14pyridine. The guests are the organic compounds commonly used in sunscreens, namely benzophenone, dioxybenzone, homosalate, oxybenzone, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), and sulisobenzone. Host–guest complexes are formed by placing each guest molecule manually inside the cavity of the host in different conformations and allowed to relax to its best possible position. The geometry optimization is carried out at the wB97X-D3/def2-TZVP and no symmetry constraints are applied. The lowest-energy conformation was selected for further electronic and interaction analysis. ωB97X-D344 is a range-separated DFT functional including Grimme’s dispersion correction (D3). D3 is employed for efficient capturing of non-covalent interactions. The frequency calculations are also performed at ωB97X-D3/def2-TZVP level of DFT. The absence of imaginary frequencies in the output files further confirms that the optimized geometries are present at true minima. Moreover, the other parameters such as frontier molecular orbital (FMO), natural bond orbital (NBO)45, density of states (DOS)46, and electron density difference (EDD)47 are analyzed at the same level of theory. NBO is performed using NBO 7.0 package48. VMD software49 is used for visualizing figures of FMO, DOS and EDD. Interaction energies (Eint) of the most stable host-guest complexes are calculated using the following Eq.

Here, Eint is interaction energy of the designed complex, Ecomplex is the energy of the host-guest complex, whereas Ebelt[14]pyridine and Eorganic UV filter are the energies of host and guest, respectively. The non-covalent interactions in the complexes are determined via non-covalent interaction index (NCI) and quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analyses. Multiwfn 3.8 software50 is used for the generation of 2D and 3D images of NCI. 2D maps depend on electron density (ρ) and the reduced density gradient51, i.e.,

The strength and nature of non-covalent interactions is further elaborated via QTAIM analysis. Multiwfn 3.8 and VMD softwares are employed for the analysis and visualization of QTAIM, respectively. QTAIM analysis involves various topological parameters, i.e., bond critical points (BCPs), electron density ρ(r), Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r), local potential energy G(r), local kinetic energy V(r) and total electron energy density H(r). The total energy density H(r) is sum of local kinetic and potential energies i.e., V(r) and G(r), respectively.

Moreover, the interaction energy (Eint) of individual bonds is calculated via Espinosa approach to further verify the nature of non-covalent interactions. The Eint is calculated as follows,

The values of Eint ranging from 3 to 10 kcal/mol, describe the presence of electrostatic interactions (hydrogen bonding) between the host-guest complexes52,53, whereas the value less than 3 kcal/mol, shows the presence of weak van der Waals interactions. Moreover, the recovery time (\(\:\tau\:\)) is also calculated through transition state theory, employing the following Eq.

Here, \(\:\tau\:\) is recovery time, i.e., the average time a UV filter molecule stays encapsulated within the nanobelt before desorbing. T is temperature of the system, and k is the Boltzmann constant with value of 8.62 × 10− 5 eV K− 1. It relates the average kinetic energy of particles in a gas with the temperature of the gas, Eads is the adsorption energy, υ represents the attempt frequency. Eads is the energy barrier that must be overcome for the UV filter molecule to desorb from the host. Attempt frequency (υ) is the frequency at which the encapsulated UV filter molecule attempts to escape the host cavity. DFT calculations represent molecules in their ground state under idealized (gas-phase or implicit solvent) conditions and may not fully capture solvation effects, and effects from interferents. Moreover, although ωB97X-D3 performs reliably across many systems, its accuracy may vary for specific interaction types. Therefore, while the results offer valuable insights into structure-property relationships, future experimental validation would strengthen the predictive conclusions54.

To evaluate the feasibility of UV filter encapsulation in aqueous environments, quantum molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the semi-empirical extended tight-binding (XTB) method55 implemented in ORCA 6.0. The simulations employed the GFN2-xTB Hamiltonian56, which provides a reasonable balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for large supramolecular systems in explicit solvent. The optimized host-guest complex was solvated with explicit water molecules and simulated for 10,000 steps with a 1.0 fs timestep (10 ps total simulation time). Temperature was maintained at 298.15 K using a CSVR thermostat57 in the canonical ensemble with a 30.0 fs coupling constant, and center of mass motion was removed during the simulation to prevent drift. The relatively short simulation timescale was chosen as an initial assessment of complex stability and guest approach dynamics, with the understanding that complete encapsulation events may require longer timescales or enhanced sampling methods.

Results and discussion

Interaction energies and distances

Six host-guest encapsulated supramolecular complexes are designed in this study. The host molecule is a pyridine belt composed of 14 pyridine units, i.e., belt14pyridine. The guests are the organic compounds commonly used in sunscreens, namely benzophenone, dioxybenzone, homosalate, oxybenzone, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), and sulisobenzone. The guest species are encapsulated inside the host in different configurations in order to interpret the most stable configuration. The interaction energies (Eint) and interaction distances (Dint) of the most stable host-guest complexes are reported in Table 1, while the Eint of other complexes are mentioned in Supporting Information. The optimized geometries along with interaction distances are shown in Fig. 1. The Eint of the complexes range from − 13.70 to -26.11 kcal/mol, which are quite reasonable indicating the stability of the complexes. The Eint for benzophenone@belt complex is -13.70 kcal/mol and the Dint for this complex range from 2.58 to 2.87 Å. The most stable configuration of benzophenone in the belt is the one in which it occupies the central position inside the belt. The range of Dint shows that the interactions between the host and guest specie are the noncovalent interactions. For dioxybenzone@belt complex, Eint and Dint are − 21.75 kcal/mol and 2.36–2.82 Å, respectively. The Dint for dioxybenzone@belt complex are less compared to the former complex (i.e., benzophenone@belt), and the Eint for dioxybenzone@belt complex is greater compared to benzophenone@belt complex.

The Eint and Dint of homosalate@belt complex are − 21.60 kcal/mol and 2.14–2.65 Å, respectively. Similarly, the values of Eint and Dint for oxybenzone@belt complex are − 26.11 kcal/mol and 2.38–2.53 Å, respectively. Moreover, the Eint of PABA@belt complex is -25.45 kcal/mol and the range of Dint is 2.49–2.59 Å. The interaction energy for sulisobenzone@belt complex is -14.38 kcal/mol, i.e., lesser than all the previous complexes except benzophenone@belt complex. The reason can be attributed to the greater interaction distance between the host and guest in this complex. Overall, the complexes with lesser interaction distances between the encapsulated specie and guest nanobelt show the higher values of interaction energies compared to those with greater interaction distances.

In summary, the oxybenzone exhibits the strongest binding (-26.11 kcal/mol) among the studied complexes, benefiting from its extensive π-conjugated aromatic framework and dual polar functionalities (-OH and –C = O). These features enable synergistic π–π stacking driven by dipole attractions with belt’s pyridinic units at interaction distance of ~ 2.38–2.53 Å. PABA@belt (-25.45 kcal/mol) also exhibits extensive π–π stacking, evidenced by widespread green areas (in NCI analysis), and displays moderate dipole–dipole interactions around its –NH₂ and –COOH functionalities. Yet, its aromatic surface and dipole alignment are slightly inferior to oxybenzone’s, resulting in ~ 0.7 kcal less stabilization. Dioxybenzone and homosalate (-21.75 and − 21.60 kcal/mol) still display significant interactions but lack oxybenzone’s optimal aromatic overlap. Moreover, benzophenone (-13.70 kcal/mol) and sulisobenzone (-14.38 kcal/mol) have smaller interaction energies due to the observed highest interaction distances, leading to markedly weaker π–π interactions.

We expect that our computational results are consistent with experimental observations. Powdered activated carbon (PAC) achieves over 95% removal of benzophenone-type filters through dispersion-driven adsorption and hydrophobic interactions, corroborating our identification of π–π and dipole-dipole interactions in UV-filters@belt complexes58. Our theoretical predictions closely reflect experimental trends observed in analogous cyclodextrin-UV filter systems. AVB:β-CD complexes with a molar ratio of 50–100 exhibit the strongest photostability, evidenced by hypochromic/hyperchromic transitions in UV–vis spectra and prolonged stabilization of the diketo tautomer, consistent with our computational identification of strong π–π and dipolar interactions supported by binding energies and NCI analysis59. Similarly, inclusion of oxybenzone in HP-β-CD shows an AL-type phase-solubility behavior with a binding constant around 2047 M⁻¹, reinforcing our structural insights into non-covalent stabilization. Moreover, literature reports the combined experimental and theoretical studies for the formation of inclusion complexes inside the cavity of β-cyclodextrins. The theoretical studies supported the results of experimental analysis60. Elasaad et al. reported the experimental and theoretical studies on α-cyclodextrin–p-aminobenzoic acid complex. Experimental crystal structures confirm a 1:1 inclusion of the benzoic moiety into the cavity, with the amino group solvent-exposed and phase-solubility curves show AL-type behavior. Importantly, computational studies correctly predict this orientation and yield stability constants, consistent with UV-Vis thermodynamics61.

FMO analysis

Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis is performed to get insights into the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and energy gaps (Egap) of the belt, analytes and complexes. Highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) isodensities are shown in Fig. 2, whereas Table 2 shows the values of the energies of HOMO (EHOMO), LUMO (ELUMO) and HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (Egap). The values of EHOMO, ELUMO and Egap for belt14pyridine are − 7.50, -3.58 and 3.92 eV, respectively. The values of EHOMO for the guest species range from − 8.35 to -9.32 eV, i.e., HOMO of the guests lie lower than HOMO of the host. Similarly, the values of ELUMO for the guest species range from − 0.26 to 0.89 eV, i.e., LUMO of the guests are above the LUMO of the host. Therefore, in all the resulting host-guest complexes, the values of both EHOMO and ELUMO are closer to the host, i.e., belt14pyridine compared to the guests.

For belt14pyridine, HOMO isodensities are observed over the N of the pyridine rings, indicating that the electron density is greater on the N atom containing side of the nanobelt. The LUMO isodensities are observed on the other side of the nanobelt, i.e., mostly over C atoms. After encapsulation of the organic compounds inside the belt, there is no difference in the HOMO and LUMO isodensities of the resulting complexes. For benzophenone@belt, dioxybenzone@belt, oxybenzone@belt and sulisobenzone@belt complexes, the HOMO isodensities lie over the N atoms of the belt14pyridine and LUMO isodensities over the C atoms of the belt, i.e., similar to the bare belt. Whereas, for homosalate@belt complex, the HOMO isodensities reside over both the host and guest species. Moreover, the HOMO isodensities for PABA@belt complex reside over the guest PABA molecule, showing guest as the electron rich specie. The energy gaps of the complexes range from 3.73 to 4.07 eV i.e., are closer to the bare belt compared to the guests. Overall, it can be concluded that the HOMO, LUMO levels and energy gaps of complexes closely resemble those of the bare host compared to the guest species, due to the higher values of EHOMO and lower values of ELUMO, respectively.

DOS

Density of states (DOS) spectra analysis is performed to confirm the results of FMO analysis i.e., to analyze the contribution of HOMO and LUMO levels of the host and guest towards the HOMO and LUMO of the encapsulated host-guest complexes. Figure 3 illustrates the DOS spectra of the complexes. The plots show density of states on y-axis and energy on x-axis. The vertical dotted line in the figures shows the HOMO level, whereas the first small red colored line on x-axis after HOMO indicates the position of LUMO. Moreover, the energy difference between the HOMO and LUMO levels specifies the Egap. The total density of states for the host-guest complex is represented by the black colored curves, whereas the partial density of states for the host and guests are represented by red and blue curves, respectively. For benzophenone@belt, the plot clearly indicates the positions of HOMO and LUMO at -7.47 eV and − 3.42 eV, respectively. At the position of HOMO, both the red and blue curves appear, among which the red curve is dominant, indicating the greater contribution of HOMO of the belt towards the HOMO of the complex. However, at LUMO, only red curve appears, and the blue curve diminishes. The presence of only red colored curve at the LUMO demonstrates the contribution of LUMO of the belt towards the LUMO of host-guest complexes. The results obtained by observing the DOS spectra for benzophenone@belt are similar to those obtained via FMO analysis for the complex. A similar pattern is seen for all the other complexes, i.e., the positions of HOMO, LUMO and their contributions towards the HOMO and LUMO of the complexes obtained through DOS analysis is similar to the findings of FMO analysis. The DOS maps for dioxybenzone@belt, oxybenzone@belt, and sulisobenzone@belt, show that both the HOMO and LUMO are derived from the belt. Moreover, for homosalata@belt complex, HOMO is derived from both the host and guest, whereas LUMO is derived entirely from the host. Moreover, for PABA@belt complex, the HOMO and LUMO are derived entirely from guest and host species, respectively. Overall, DOS analysis demonstrate that the HOMO and LUMO of the host-guest complexes originate entirely from HOMO and LUMO of the belt (host) and there is no contribution of the guest molecules towards the HOMO and LUMO of the designed complexes.

NBO

Natural bond orbital (NBO) charge analysis of the complexes is performed to examine the phenomena of charge transfer within the complexes. NBO helps to determine the net magnitude as well as direction of charge transfer, i.e., from host towards guest or vice versa. Before the complexation, the net charge on the individual host and guest species are zero. Table 2 shows that for all the complexes, NBO charges on the guest species after complexation are negative, indicating the direction of charge transfer from the host to the guests. The values of NBO charge range from − 0.007|e| to -0.022|e|, showing a reasonable interaction between the host and guest in the complexes. The NBO charge for dioxybenzone after encapsulation inside the belt is -0.007|e|, followed by -0.014|e| for PABA, -0.015|e| for benzophenone and homosalate, -0.016|e| for oxybenzone and − 0.022|e| for sulisobenzone, respectively. The results of NBO analysis for the complexes indicate the electron withdrawing capability of the guests compared to the host. The magnitude of NBO charges is highest for sulisobenzone@belt complex, due to the greater size of the encapsulated specie. The greater interactions with the belt, results in withdrawal of comparatively greater charge. These results are further confirmed via EDD analysis. Overall, NBO analysis describes the direction of charge transfer, i.e., from host towards the guest for all the designed complexes.

EDD

Electron density difference (EDD) analysis is a visual illustration of the NBO charge transfer. It clearly illustrates the electron donating and accepting regions of both the host and guest in the resulting complex. Figure 4 shows the EDD isosurfaces for the complexes. The blue colored isosurfaces indicate the regions where charge is being accumulated, whereas the red colored isosurfaces indicate the regions where charge is being depleted. For benzophenone@belt complex, the greater number of blue colored patches are seen on the guest specie i.e., benzophenone compared to the red colored patches, indicating the charge accumulation towards the guest. The blue patches are also present on the belt, demonstrating that some regions of the belt also accumulate charge, whereas the greater number of red patches on the belt indicate the overall charge depletion from the belt, which is transferred towards benzophenone.

Similarly, for dioxybenzone@belt complex, the greater blue patches are present over the dioxybenzone compared to the belt. The red patches are evident especially on one side of the belt, where there is greater interaction between the host and guest, demonstrating the overall transfer of charge from belt towards dioxybenzone. A similar behavior is observed for homosalate@belt, oxybenzone@belt and PABA@belt complexes. Moreover, for sulisobenzone@belt complex, the denser isosurfaces are observed on one side of the complex in comparison to the other side. This demonstrates that the overall charge depletion from the belt is mainly due to the charge depletion from that side (showing denser isosurfaces). Overall, the EDD analysis corroborates with NBO analysis, demonstrating the direction of charge transfer from host towards the guests for all the complexes.

NCI

NCI analysis provides an index to identify the non-covalent interactions. 2D and 3D images obtained via NCI analysis are helpful for determination of the nature and strength of non-covalent interactions present between the host and guest in the complexes. NCI usually differentiate the type of interaction through different colors. Red color in the figures represent the steric repulsions, whereas blue and green represent the electrostatic attraction (e.g., hydrogen bonding) and non-covalent interactions (e.g., π-π stacking and dipole-dipole interactions), respectively. 3D and 2D NCI images for the designed complexes in our study are shown in Fig. 5. In 3D image of benzophenone@belt complex, the red and green patches are more obvious. The red patches are present within the host nanobelt, i.e., inside the pyridine rings, showing the presence of repulsive forces within the host molecule. The green patches appear to disperse between the belt and benzophenone. These patches show that the aromatic rings of benzophenone are engaged in π–π interactions with the electron-rich pyridine units of belt. The green patches are denser over the regions where there is greater interaction between the host and guest, i.e., belt and benzophenone. So, the complex, i.e., benzophenone@belt is stabilized by non-covalent interactions between the interacting fragments. The 2D image of benzophenone@belt shows the greater number red and green colored spikes, confirming the presence of steric repulsions and non-covalent interactions in the complex, respectively.

For dioxybenzone@belt complex, 3D image reveals the red colored patches in the pyridine rings of the host and benzene rings of the guest, specifying the regions of steric repulsions. The greater number of green colored patches are present between the belt and dioxybenzone, describing that the guest dioxybenzone is stabilized through non-covalent interactions inside the host belt14pyridine. The patches between the aromatic rings of dioxybenzone and belt specify the existence of π–π stacking interactions, whereas the patches between the polar groups (R-OH, R-O-R) of dioxybenzone and the pyridine units of the belt specify the presence of dipole-dipole interactions between the host-guest species. Moreover, the absence of blue colored patches elaborate the absence of hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions between the host and guest. Similarly, 2D image for the complex shows the denser spikes for this complex. In comparison between the NCI images of benzophenone@belt and dioxybenzone@belt complexes, it can be observed that there are greater number of green colored patches and spikes in the latter complex, indicating its greater stability. The results of NCI analysis for these two complexes corroborate with the results of interaction energy, where the greater Eint is also observed for the latter complex.

Likewise, the results of NCI analysis for the other four complexes show the identical behavior with the previous ones, i.e., in all the designed complexes, red colored patches appear within the pyridine rings of the host (steric repulsions) and greater green colored patches are prominent between the host and guest species (π-π stacking and dipole-dipole interactions), whereas one small blue colored patch is seen in homosalate@belt and sulisobenzone@belt complexes each, demonstrating the presence of electrostatic attractions in these complexes. Similarly, the red and green colored spikes are also evident in the 2D images. So, NCI analysis confirms that all the designed host-guest complexes are stabilized via non-covalent interactions mainly, with greater non-covalent interactions observed for the complexes having greater interaction energies (Eint) and vice versa. Overall, the noncovalent interaction index (NCI) analysis specify that the patches between the aromatic rings of UV filter compounds and belt specify the existence of π–π stacking interactions, whereas the patches between the polar groups (R-OH, R-O-R) of dioxybenzone and the pyridine units of the belt specify the presence of dipole-dipole interactions between the host-guest species. Moreover, the absence of blue colored patches elaborate the absence of hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions between the host and guest. The nature of noncovalent interactions present in benzophenone@belt, dioxybenzone@belt, oxybenzone@belt, and PABA@belt is π–π stacking and dipole-dipole interactions. Moreover, the interactions present in homosalate@belt and sulisobenzone@belt complexes are hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking and dipole-dipole interactions.

QTAIM

Bader ‘s Quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) is a topological analysis that describes the presence of intermolecular interactions within the complexes such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces. QTAIM analysis comprises several topological parameters, i.e., bond critical points (BCPs), electron density ρ(r), Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r), local potential energy G(r), local kinetic energy V(r) and total electron energy density H(r). The strength and nature of the interactions between the host nanobelt and the guest organic compounds can easily be determined by observing the values of these parameters. Figure 6 shows the BCPs of six host-guest complexes, and Table 3 lists the values of QTAIM parameters for the said complexes. BCPs for the complexes range from 9–15 in number. For benzophenone@belt complex, the number of BCPs are 10. These BCPs are present between the H, O, and C atoms of the guest and N and C atoms of the host (i.e., H-N, O-C, C-C, C-N). The values of electron density ρ(r) and Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r) range from 0.0009–0.0118 a.u and 0.003–0.040 a.u respectively. Similarly, the values of local potential energy G(r), local kinetic energy V(r) and total electron energy density H(r) for the complex range from 0.0004–0.0083 a.u, -0.0003 to -0.0058 a.u, and 0.0002–0.0016 a.u respectively. Moreover, the values of -V/G range from 0.19–0.84, i.e., less than 2, indicating that the van der Waals forces are present in the complex. Finally, the values of interaction energies of individual bonds (Eint) range from 0.09–1.82 kcal/mol, which are less than 3, justifying the absence of hydrogen bonding. Hence, it can be concluded that the complex is stabilized via van der Waals forces or non-covalent interactions.

For dioxybenzone@belt complex, the number of BCPs are 15, and the BCPs are mostly present between the H, O and C atoms of the guest and C, H and N atoms of the host. The number of BCPs are greater for this complex compared to the previous one, justifying the greater Eint of dioxybenzone@belt compared to benzophenone@belt complex. Similarly, the values of electron density ρ(r) and Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r) range from 0.0020 to 0.0117 a.u and 0.007–0.049 a.u, respectively. Furthermore, the values of local potential energy G(r), local kinetic energy V(r) and total electron energy density H(r) for the complex range from 0.0012 to 0.0098 a.u, -0.0008 to -0.0074 a.u, and 0.0005–0.0024 a.u, respectively. Likewise, the ratio of -V/G and Eint ranges from 0.60 to 0.83 and 0.25–2.32 kcal/mol, respectively, confirming the existence of noncovalent interactions as predicted by NCI analysis. The range of all the QTAIM parameters for dioxybenzone@belt complex are greater compared to benzophenone@belt, which supports the greater Eint for dioxybenzone@belt.

For homosalate@belt complex, the number of BCPs are 13, which exist mostly between H, C, O of the guest homosalate and N, C, H atoms of the host nanobelt. The values of ρ(r) and ∇2ρ(r) range from 0.0030 to 0.0180 a.u and 0.010–0.064 a.u, respectively. Likewise, values of G(r), V(r) and H(r) range from 0.0019 to 0.0141 a.u, -0.0013 to -0.0121 a.u, and 0.0005–0.0020 a.u, respectively. Moreover, the Eint and -V/G for the complex range from 0.41 to 3.80 kcal/mol and 0.67–0.86, respectively. One value of Eint is greater than 3, i.e., 3.80 kcal/mol, demonstrating that there is one H-bond in the complex, resulting in the greater stability of the complex as predicted via interaction energy analysis.

There are 12 BCPs for oxybenzone@belt complex and the range of values for QTAIM parameters at the BCPs are 0.0036–0.0122 a.u, 0.012–0.047 a.u, 0.0023–0.0094 a.u, -0.0016 to -0.0072 a.u, 0.0006–0.0024 a.u respectively for ρ(r), ∇2ρ(r), G(r), V(r), and H(r). Moreover, the values of Eint and -V/G for the complex range from 0.50 to 2.26 kcal/mol and 0.69–0.82, respectively. The values of the parameters show that the host-guest complex oxybenzone@belt is stabilized via non-covalent or van der Waals interactions. Moreover, there are 9 BCPs for PABA@belt complex. The QTAIM parameters at BCPs connecting PABA and the belt are 0.0034–0.0106 a.u, 0.014–0.039 a.u, 0.0029–0.0082 a.u, -0.0021 to -0.0067 a.u, and 0.0008–0.0016 a.u respectively for ρ(r), ∇2ρ(r), G(r), V(r), and H(r). Similarly, the values of Eint and -V/G for the complex range from 0.66 to 2.10 kcal/mol and 0.72–0.82, respectively, i.e., presence of van der Waals forces is confirmed. Furthermore, there are 11 BCPs for sulisobenzone@belt complex. The parameters ρ(r), ∇2ρ(r), G(r), V(r), and H(r) for sulisobenzone@belt range from 0.0035 to 0.0185 a.u, 0.013–0.057 a.u, 0.0024–0.0128 a.u, -0.0016 to -0.0113 a.u, and 0.0008–0.0017 a.u, respectively. Eint and -V/G for this complex range from 0.50 to 3.54 kcal/mol and 0.67–0.88, respectively, demonstrating the existence of one hydrogen bond at one BCP, and the other non-covalent interactions as the reason of stability of the guest inside the host. Overall, QTAIM analysis confirms the presence of van der Waals forces as the major reason for stability of the designed host-guest complexes. The results are in corroboration with NCI and interaction energy analyses.

Recovery time

Recovery time (τ) is the average time a UV filter molecule stays encapsulated within the nanobelt before desorbing. It is measured in seconds (s). Recovery time for the designed host-guest complexes is studied employing transition state theory at different temperatures i.e., 298, 350 and 400 K. There is a direct relation between recovery time and adsorption or interaction energy (Eint or Eads)62, i.e., a higher Eads indicates stronger host-guest interactions, leading to longer retention times. Additionally, there is also a direct relationship between adsorption (Eads) and desorption energies (Edes). Table 4 shows that the complexes with higher Eads show a greater recovery time and vice versa. Similarly, the complexes with less Edes have lesser recovery time. Moreover, the complexes with greater Eads have greater Edes and vice versa. At temperatures of 298 K, 350 K and 400 K, the values of recovery time range from 1.1\(\:\times\:\)10−2 to 1.4\(\:\times\:\)107 s, 3.5\(\:\times\:\)10−4 to 1.9\(\:\times\:\)104 s, and 3.0\(\:\times\:\)10−5 to 1.8\(\:\times\:\)102 s, respectively. For benzophenone@belt complex, having desorption energy (Edes) of 13.70 kcal/mol, the recovery time at 298, 350 and 400 K is 1.1\(\:\times\:\)10−2, 3.5\(\:\times\:\)10−4, and 3.0\(\:\times\:\)10−5 s, respectively. These values indicate that by increasing the temperature, recovery time is decreased. Similarly, for all the other complexes, an recovery time decrease with increase in temperature. Overall, the recovery time of the complexes show a general trend, i.e., increases with increase in Eads and decreases with increase in temperature.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

Quantum molecular dynamics simulations were performed to address the critical question of whether UV filter molecules can successfully approach and enter the belt14pyridine cavity in realistic aqueous conditions. While static DFT calculations demonstrate thermodynamically favorable host-guest interactions, the dynamic process of guest encapsulation in the presence of competing water molecules requires explicit simulation.

The 10 ps quantum MD simulation at 298.15 K revealed that the belt14pyridine structure remained stable throughout the trajectory, maintaining its cavity geometry despite thermal fluctuations and solvent interactions. Importantly, the UV filter molecule (sulisobenzone) showed directed movement toward the belt cavity, successfully displacing water molecules from the cavity entrance. This displacement indicates that the host-guest interaction is sufficiently strong to overcome the hydration shell around both species.

Although complete encapsulation was not observed within the 10 ps timescale, the observed approach dynamics and water displacement support the thermodynamic favorability predicted by static calculations. These results justify the proposed encapsulation mechanism and suggest that with longer simulation times or enhanced sampling techniques, complete inclusion events would be observable.

Conclusions

This study reports the encapsulation of harmful UV filters as guests inside the host i.e., belt14pyridine. Six complexes are formed, containing belt14pyridine as host and benzophenone, dioxybenzone, homosalate, oxybenzone, PABA, and sulisobenzone as guests. The interaction energies of the host-guest complexes are a proof of their thermodynamic stability, i.e., ranging from − 13.70 to -26.11 kcal/mol. FMO analysis reveal that after encapsulation, the HOMO and LUMO of the complexes originate entirely from HOMO and LUMO of the host nanobelts. Also, the energy gaps of the complexes decrease compared to the energy gaps of the bare guest species. The DOS spectra justifies the results of FMO analysis, through visual illustration of the position of HOMO, LUMO levels and energy gaps. NBO charge analysis determines the net charge transfer towards the guest species after complexation. The greater magnitude of NBO charge transfer is observed for sulisobenzone@belt complex, i.e., 0.022|e| due to greater size and interactions of sulisobenzone with the host nanobelt. EDD analysis provides a visual illustration of charge transfer predicted via NBO charge transfer analysis, i.e., the direction of charge transfer from the host to guest. Moreover, NCI analysis stated the reason behind stability of host-guest complexes as non-covalent interactions, which is further confirmed via QTAIM analysis. NCI reveals a greater number of green colored patches in the vicinity of the guest where it has greater interactions with the host. Similarly, QTAIM analysis further prove the strength and nature of non-covalent interactions. The greater number of BCPs, i.e., 15 are found for dioxybenzone@belt complex, showing greater non-covalent interactions between dioxybenzone and the belt. Furthermore, the recovery time and desorption energy are greater for the complex (oxybenzone) with greater interaction energy, i.e., 1.4\(\:\times\:\)107 s (at 298 K) and 26.11 kcal/mol, respectively. The least recovery time is found for benzophenone@belt complex, i.e., 3.0\(\:\times\:\)10−5 s at 400 K. Thus, it can be concluded that the host belt14pyridine can effectively encapsulate all the guest species, and therefore it can be regarded as a suitable host for complexation with organic UV filters, for the sake of their removal.

Data availability

All the data supporting the manuscript have been added in the supporting information file.

References

Nitulescu, G., Lupuliasa, D., Adam-Dima, I. & Nitulescu, G. M. Ultraviolet filters for cosmetic applications. Cosmetics 10 (4), 101 (2023).

Bernerd, F., Passeron, T., Castiel, I. & Marionnet, C. The damaging effects of long UVA (UVA1) rays: a major challenge to preserve skin health and integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (15), 8243 (2022).

Fivenson, D. et al. Sunscreens: UV filters to protect Us: part 2-Increasing awareness of UV filters and their potential toxicities to Us and our environment. Int. J. Women’s Dermatology. 7 (1), 45–69 (2021).

Guan, L. L., Lim, H. W. & Mohammad, T. F. Sunscreens and photoaging: a review of current literature. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 22 (6), 819–828 (2021).

Ekstein, S. F. & Hylwa, S. Sunscreens: a review of UV filters and their allergic potential, Dermatitis® 34 (3), 176–190 (2023).

Giokas, D. L., Salvador, A. & Chisvert, A. UV filters: from sunscreens to human body and the environment. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 26 (5), 360–374 (2007).

Bens, G. Sunscreens, sunlight, vitamin D and skin cancer. 137–161, (2008).

Moradi, N., Amin, M. M., Fatehizadeh, A. & Ghasemi, Z. Degradation of UV-filter Benzophenon-3 in aqueous solution using TiO 2 coated on quartz tubes. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 16, 213–228 (2018).

Pniewska, A. & Kalinowska-Lis, U. A survey of UV filters used in sunscreen cosmetics. Appl. Sci. 14 (8), 3302 (2024).

Nitulescu, G., Lupuliasa, D., Adam-Dima, I. & Nitulescu, G. Ultraviolet filters for cosmetic applications. Cosmetics 10, 101 (2023).

Tran, H. T. et al. Advanced treatment technologies for the removal of organic chemical sunscreens from wastewater: a review. Curr. Pollution Rep. 8 (3), 288–302 (2022).

Archer, E., Petrie, B., Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. & Wolfaardt, G. M. The fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), endocrine disrupting contaminants (EDCs), metabolites and illicit drugs in a WWTW and environmental waters, Chemosphere 174, 437–446 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Occurrence and behavior of four of the most used sunscreen UV filters in a wastewater reclamation plant. Water Res. 41 (15), 3506–3512 (2007).

Kasprzyk-Hordern, B., Dinsdale, R. M. & Guwy, A. J. Multiresidue methods for the analysis of pharmaceuticals, personal care products and illicit drugs in surface water and wastewater by solid-phase extraction and ultra performance liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391, 1293–1308 (2008).

Downs, C. et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 70 (2), 265–288 (2016).

Weiss, S., Jakobs, J. & Reemtsma, T. Discharge of three benzotriazole corrosion inhibitors with municipal wastewater and improvements by membrane bioreactor treatment and ozonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (23), 7193–7199 (2006).

Gackowska, A. & Studziński, W. Effect of activated sludge on the degradation of 2-ethylhexyl 4-methoxycinnamate and 2-ethylhexyl 4-(dimethylamino) benzoate in wastewater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 231 (4), 158 (2020).

Tsui, M. M., Leung, H., Lam, P. K. & Murphy, M. B. Seasonal occurrence, removal efficiencies and preliminary risk assessment of multiple classes of organic UV filters in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 53, 58–67 (2014).

Mustafa, S. F. Z., Arsad, S. R., Mohamad, H., Abdallah, H. H. & Maarof, H. Host-guest molecular encapsulation of cucurbit [7] uril with dillapiole congeners using docking simulation and density functional theory approaches. Struct. Chem. 32, 1151–1161 (2021).

Maqbool, M. et al. Finely tuned energy gaps in host-guest complexes: insights from belt [14] pyridine and fullerene-based nano-Saturn systems. Diam. Relat. Mater. 150, 111686 (2024).

Maqbool, M., Aetizaz, M. & Ayub, K. Chiral discrimination of amino acids by möbius carbon belt. Diam. Relat. Mater. 146, 111227 (2024).

Maqbool, M. & Ayub, K. Controlled tuning of HOMO and LUMO levels in supramolecular nano-Saturn complexes. RSC Adv. 14 (53), 39395–39407 (2024).

Maqbool, M. & Ayub, K. Chiral recognition of amino acids through homochiral metallacycle [ZnCl 2 L] 2. Biomaterials Sci. 13 (1), 310–323 (2025).

Chen, G. & Jiang, M. Cyclodextrin-based inclusion complexation bridging supramolecular chemistry and macromolecular self-assembly. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (5), 2254–2266 (2011).

Márquez, C., Hudgins, R. R. & Nau, W. M. Mechanism of host – guest complexation by cucurbituril. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (18), 5806–5816 (2004).

Guo, D. S. & Liu, Y. Supramolecular chemistry of p-sulfonatocalix [n] Arenes and its biological applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (7), 1925–1934 (2014).

Steinmetz, M. & Sémeril, D. Molecular modeling is key to understanding supramolecular resorcinarenyl capsules, inclusion complex formation and organic reactions in nanoconfined space. Molecules 30 (12), 2549 (2025).

Zhang, Q., Ma, X., Dzakpasu, M. & Wang, X. C. Evaluation of ecotoxicological effects of benzophenone UV filters: luminescent bacteria toxicity, genotoxicity and hormonal activity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 142, 338–347 (2017).

DiNardo, J. C. & Downs, C. A. Dermatological and environmental toxicological impact of the sunscreen ingredient oxybenzone/benzophenone-3. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 17 (1), 15–19 (2018).

Scheele, A., Sutter, K., Karatum, O., Danley-Thomson, A. A. & Redfern, L. K. Environmental impacts of the ultraviolet filter oxybenzone. Sci. Total Environ. 863, 160966 (2023).

Esperanza, M., Seoane, M., Rioboo, C., Herrero, C. & Cid, Á. Differential toxicity of the UV-filters BP-3 and BP-4 in chlamydomonas reinhardtii: A flow cytometric approach. Sci. Total Environ. 669, 412–420 (2019).

Zhang, S., Chen, J., Zhao, Q., Xie, Q. & Wei, X. Unveiling self-sensitized photodegradation pathways by DFT calculations: A case of sunscreen p-aminobenzoic acid. Chemosphere 163, 227–233 (2016).

Ge, J. et al. Photochemical behavior of benzophenone sunscreens induced by nitrate in aquatic environments. Water Res. 153, 178–186 (2019).

Erol, M. et al. Evaluation of the endocrine-disrupting effects of homosalate (HMS) and 2-ethylhexyl 4-dimethylaminobenzoate (OD-PABA) in rat pups during the prenatal, lactation, and early postnatal periods. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 33 (10), 775–791 (2017).

Wheate, N. J. A review of environmental contamination and potential health impacts on aquatic life from the active chemicals in sunscreen formulations. Aust. J. Chem. 75 (4), 241–248 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Single and mixture toxicity evaluation of avobenzone and homosalate to male zebrafish and H295R cells. Chemosphere 343, 14027 (2023).

Krzeminski, P., Schwermer, C., Wennberg, A., Langford, K. & Vogelsang, C. Occurrence of UV filters, fragrances and organophosphate flame retardants in municipal WWTP effluents and their removal during membrane post-treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 323, 166–176 (2017).

Jain, M. et al. Current perspective of innovative strategies for bioremediation of organic pollutants from wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 344, 126305 (2022).

Ramos, S., Homem, V., Alves, A. & Santos, L. A review of organic UV-filters in wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Int. 86, 24–44 (2016).

Giannakis, S. et al. Effect of advanced oxidation processes on the micropollutants and the effluent organic matter contained in municipal wastewater previously treated by three different secondary methods. Water Res. 84, 295–306 (2015).

Bagayoko, D. Understanding density functional theory (DFT) and completing it in practice. AIP Adv. 4, 12, (2014).

Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U. & Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. The J. Chem. Phys. 152, 22, (2020).

García-Valverde, M., Cordero, N. & de la Cal, E. S. GAUSSVIEW® as a tool for learning organic chemistry. In EDULEARN15 proceedings IATED, 4366–4370. (2015).

Lin, Y. S., Li, G. D., Mao, S. P. & Chai, J. D. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with improved dispersion corrections. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9 (1), 263–272 (2013).

Weinhold, F., Landis, C. & Glendening, E. What is NBO analysis and how is it useful? Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 35 (3), 399–440 (2016).

Toriyama, M. Y. et al. How to analyse a density of States. Mater. Today Electron. 1, 100002 (2022).

Ayub, A. R. et al. Density functional theory (DFT) study of non-linear optical properties of super salt doped Boron nitride cage. Diam. Relat. Mater. 137, 110080 (2023).

Glendening, E. et al. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison. (2018).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14 (1), 33–38 (1996).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33 (5), 580–592 (2012).

Pan, S. et al. Selectivity in gas adsorption by molecular cucurbit [6] uril. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120 (26), 13911–13921 (2016).

Espinosa, E., Molins, E. & Lecomte, C. Hydrogen bond strengths revealed by topological analyses of experimentally observed electron densities. Chem. Phys. Lett. 285, 3–4 (1998).

Mata, I., Alkorta, I., Espinosa, E. & Molins, E. Relationships between interaction energy, intermolecular distance and electron density properties in hydrogen bonded complexes under external electric fields. Chem. Phys. Lett. 507, 1–3 (2011).

Liu, X., Spiekermann, K., Menon, A., Green, W. H. & Head-Gordon, M. Revisiting a large and diverse data set for barrier heights and reaction energies: Best practices in density functional theory calculations for chemical kinetics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. (2025).

Bannwarth, C. et al. Extended tight-binding quantum chemistry methods. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Mol. Sci. 11 (2), e1493 (2021).

Bannwarth, C., Ehlert, S. & Grimme, S. GFN2-xTB—An accurate and broadly parametrized self-consistent tight-binding quantum chemical method with multipole electrostatics and density-dependent dispersion contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15 (3), 1652–1671 (2019).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. The J. Chem. Phys. 126, 1, (2007).

Imamović, B. et al. Stability and removal of benzophenone-type UV filters from water matrices by advanced oxidation processes, Molecules 27 (6), 1874, (2022).

Kuroda, C. et al. Stability and properties of ultraviolet filter avobenzone under its diketo/enol tautomerization induced by molecular encapsulation with β-Cyclodextrin. Langmuir, (2025).

Kicuntod, J. et al. Theoretical and experimental studies on inclusion complexes of pinostrobin and β-cyclodextrins. Sci. Pharm. 86 (1), 5 (2018).

Elasaad, K., Norberg, B. & Wouters, J. Crystallographic, UV spectroscopic and computational studies of the inclusion complex of α-cyclodextrin with p-aminobenzoic acid. Supramol. Chem. 24 (5), 312–324 (2012).

Ahsan, A. & Ayub, K. Theoretical study on the capture of toxic gases by ionic liquids encapsulated in assembled belt [14 [pyridine. J. Mol. Liq. 401, 124649 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU250178].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maria Maqbool wrote the main manuscript and analyzed the dataFaiza Ullah performed all the calculationsNadeem S. Sheikh provided resources and softwaresImene Bayach: Funding acquisitionKhurshid Ayub: Methodology, Review, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maqbool, M., Ullah, F., Sheikh, N.S. et al. Potential of pyridine nanobelt in detecting and trapping of harmful UV filters. Sci Rep 15, 36357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20135-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20135-1