Abstract

Bound states in the continuum represent a unique optical phenomenon characterized by extremely high-quality factors and low energy losses, offering great potential for high-sensitivity sensing applications. In this study, we investigated the optical properties of nanoporous silica substrates (NSS) and nanoporous silicon dimer (NSD) structures with varying porosity percentages in different refractive index environments. The results demonstrate that the combined architecture achieves high refractive index sensitivity (\(S=830\,\text{nm}/\text{RIU}\)) and an exceptionally high figure of merit (\(FOM=4078\,{\text{RIU}}^{-1}\)). The lower refractive index of the NSS accelerates the decay of localized quasi-bound states in the continuum evanescent modes into the substrate, channeling the field into the surrounding medium, while the NSD further boosts local field intensity. The nanoporous medium structure design presented in this work offers a new strategy for developing high-performance refractive index sensors, deepening our understanding of nanoporous materials for optical sensing, and updating valuable theoretical and technical support for the practical sensor design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of nanophotonics, bound states in the continuum (BIC) have garnered significant attention as a unique physical phenomenon1,2. With advances in micro- and nano-fabrication technologies, research on BIC has gradually expanded into emerging fields such as on-chip integrated photonic devices and topological photonics, demonstrating broad application prospects3,4,5,6,7. BICs are characterized by their presence within the continuous radiation spectrum of open systems; however, due to specific symmetry or topological protection mechanisms, they can effectively decouple from external radiation fields1,8. This attribute endows BICs with exceptionally high quality (high-Q), theoretically approaching infinity. It is important to note that BICs are essentially non-radiative “dark modes”, meaning they cannot directly interact with the external radiation9,10. To fully exploit the potential of BICs in photonic devices, they must be controllably converted into quasi-bound states in the continuum (QBIC). This transformation not only retains the narrow linewidth features of the original BICs but also enhances the interaction between light and matter.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in QBIC applications. In the field of biochemical sensing, high-sensitivity techniques based on QBIC have enabled single-molecule detection, which is crucial for the precise identification of biomolecules11,12,13. In quantum optical systems, QBIC has been employed to construct strongly coupled frameworks, thereby advancing quantum optics technology14,15. The QBIC exhibits high harmonic conversion efficiency, which has recently enabled enhanced second-harmonic generation in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers and compact, polarization-invariant metadevices for biosensing and nonlinear optics, paving the way for advances in frequency conversion, optoelectronics, and on-chip photonic integration16,17. Additionally, QBIC offers innovative approaches for developing low threshold nanolasers, potentially revolutionizing laser technology18,19.

For practical applications, extracting QBIC resonances with high-Q from symmetry-protected BICs has mostly been achieved by slightly breaking the structure symmetry. Previous studies include either slightly perturbing the excitation field symmetry using oblique incidence20,21 or introducing structural asymmetry at the \(\Gamma\) point22,23,24. An alternative effective strategy employs an all‑electric superlattice metasurface, which leverages guided mode resonance coupling through precise relative displacement tuning to convert BIC states into QBIC modes25. The metasurface unit cell can be composed of the silicon nanodisk dimer arranged in a rectangular lattice on the silica substrate26,27. By adjusting the spacing between these nanodisk dimers, QBIC resonances can be triggered, offering a controllable platform for further device applications. However, the electromagnetic energy in these structures is predominantly confined within the dielectric, resulting in a relatively low evanescent field out-coupling efficiency, which greatly limits their application in biochemical sensing.

In recent years, dielectric metasurfaces based on quasi-bound states in the continuum (QBIC) induced by symmetry breaking have shown great promise for high-Q sensing. However, their practical sensitivity is often limited by the strong field localization within the dielectric resonators, which restricts field overlap with the external environment. For instance, Wang et al. designed a crescent-shaped dielectric metasurface that achieved a Q factor over 1000 but only a refractive index sensitivity of 180 nm/RIU11. To address this issue, metal-dielectric hybrid metasurfaces have been explored. Luo et al. proposed a tetramer structure incorporating gold elements, which enhanced the sensitivity to 450 nm/RIU28. While this approach improves the sensor’s response to environmental changes, the inherent ohmic loss in metallic components degrades the Q factor, and the use of expensive noble metals (e.g., Au) raises concerns about fabrication cost and scalability.

To overcome the performance bottlenecks of current refractive index sensors, this study introduces an innovative design of a nanoporous-dielectric-based metasurface that simultaneously enhances high-Q and near-field sensitivity. The design incorporates a nanoporous structure with aperture sizes ranging from 2 to 8 nm, efficiently reducing the effective refractive index of both the substrate and the dimer materials29,30,31,32. By exciting quasi-bound states QBIC within the continuous spectrum, the structure produces a significantly enhanced electric field distribution near the target environment and the dimer configuration. Furthermore, the tailored reconfiguration of the electric field within the nanoporous structure not only broadens the optical field coverage in the sensing area but also boosts the detection sensitivity. Simulation results indicate that at a wavelength of 1373.5 nm, the sensor achieves a significantly optimized performance with a sensitivity33 of \(S =\Delta \lambda /\Delta n= 830\,\text{nm}/\text{RIU}\) and a Q factor of \(Q =\lambda /FWHM= 5.97\times {10}^{3}\) with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.23 nm. Our work, which is currently simulation-based, demonstrates a significant improvement in overall performance as quantified by the figure of merit34 (\(FOM=S/FWHM=4078\,\text{RIU}^{-1}\)). It outperforms previously reported dielectric metasurfaces in both experimental results and simulation studies documented in the literature35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. A comprehensive comparative analysis, encompassing both simulation and experimental data from prior studies, is provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Information. This pore-modulated photonic nanostructure thus offers a promising new approach and technological pathway for developing the next-generation highly efficient and stable optical sensors.

Structural design and optical characteristics

In this study, a three-dimensional finite-difference time-domain (3D-FDTD) method was employed to design and simulate the metasurface. A transverse electric (TE)-polarized plane wave, incident along the z-axis, was used as the excitation source, spanning a spectral range of 1300–1500 nm to fully cover the QBIC resonance near 1373.5 nm. To ensure accurate field resolution near subwavelength features, a non-uniform meshing scheme was adopted, with the minimum mesh size set to 5 nm. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in the x–y plane to replicate the metasurface’s periodicity, while perfectly matched layers (PML) were implemented along the z-axis to absorb outgoing waves and suppress artificial reflections, thereby mimicking an open system.

First, we simulated a silicon nanopillar dimer array fabricated on a 3000 nm-thick silicon dioxide substrate (refractive index \({n}_{Si{O}_{2}}=1.46\)), as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The optical constants of silicon were accurately determined using a J. A. Woollam M-2000DI spectroscopic ellipsometer over the wavelength range of 190–1700 nm, ensuring the reliability of the material parameters. The cylindrical design was chosen for the nanopillars due to its cost-effectiveness and high precision manufacturing benefits24,27. The metasurface unit cell was configured with periods of \({P}_{x}=1000\,\text{nm}\) and \({P}_{y}=500\,\text{nm}\), a silicon pillar diameter \(D=300\,\text{nm}\), a height \(h=180\,\text{nm}\), and refractive index of environmental medium \({n}_{e}\). When the dimers were arranged periodically with a separation \({L}_{0}={P}_{x}/2=500\,\text{nm}\), no resonance peak appeared in the transmission spectrum due to the complete decoupling of the BIC mode from the incident plane wave. To convert the BIC into observable QBIC, we introduced a subwavelength displacement perturbation (\(\Delta L=L-{L}_{0}\)) that breaks the translational symmetry25. This observation, indicated by the red curve in Fig. 1b, confirms the presence of a symmetry-protected BIC and validates our theoretical predictions. As \(\Delta L\) increases, the resonance linewidth in the transmission spectrum gradually broadens and the Q factor decreases. Compared to traditional symmetry-breaking approaches induced by geometric deformations (such as pillar truncation or size asymmetry), this displacement-tuning QBIC method exhibits higher control precision and stability26.

Excitation characteristics of QBIC in two different structures. (a) Silicon dimer structure on a silica substrate, where the centre-to-centre distance between the two nanodisks (\(L\)) equals \({L}_{0}\), which is half of the period in the x-direction (\({P}_{x}/2\)). Adjusting the relative positions of the nanodisks in the dimer enables the excitation of QBIC states. The unit cell has periods of \({P}_{x}=1000\,\text{nm}\) and \({P}_{y}=500\,\text{nm}\), with a cylinder diameter \(D=300\,\text{nm}\) and height \(h=180\,\text{nm}\). (b) Transmission spectrum for various \(\Delta L\), illustrating the transition from BIC to QBIC. (c) NSD structure with 30% porosity percentage, having the same dimensions as silicon dimer in (a) but with the substrate replaced by an NSS with the same 30% porosity percentage. (d) Transmission spectra of the NSD structure on the 30% NSS under different \(\Delta L\).

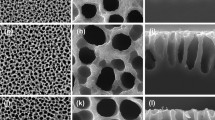

To further optimize the overall performance of the QBIC mode in silicon nanopillar dimers on a silicon dioxide substrate, we propose an innovative nanoporous structure metasurface design, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. Specifically, the conventional dense \(Si{O}_{2}\) substrate is replaced by the nanoporous silica substrate (NSS) with a pore diameter of \(4.2\pm 0.2\,\text{nm}\) and a 30% porosity percentage. Meanwhile, the silicon nanopillar dimer is converted into the nanoporous silicon dimer (NSD) with the same pore dimensions and porosity, while maintaining the environmental refractive index of \({n}_{e}=1.35\). Building upon our group’s prior experimental achievements in nanoporous metamaterial fabrication29,30, we adopted the corresponding material parameters in the present simulation study. In our earlier experimental studie31,32, we achieved precise control over porosity percentage (6.7%-63.9%) and pore size (1.2–9.3 nm) by adjusting sputtering parameters such as power, bias voltage, and deposition time. The optical constants obtained from these nanoporous structures were used as inputs for the simulation models in this work. To improve structural robustness and mitigate practical issues such as contamination during photolithography and pore clogging during sensing, we propose a conformal coating of ~ 5–10 nm silicon (for porous silicon) or silica (for porous silica). This encapsulation strategy is expected to enhance the chemical stability and reusability of the metasurfaces, making them more suitable for real-world applications.

Comparing the transmission spectra in Fig. 1b,d shows that both the modified structure and the original design exhibit QBIC characteristics with high-Q. To systematically understand the discrepancies introduced by the nanopores, we will examine the differences in field control mechanisms and refractive index response between the two designs (with and without nanopores) in the following sections, aiming to better grasp their fundamental physics and potential applications.

As shown in Fig. 2a, we first simulated a silicon nanopillar dimer structure on a silica substrate, with geometric parameters (period, diameter, height) referenced from previously reported experimental design, serving as a baseline to assess performance differences introduced by nanoporous modifications. It can be seen from Fig. 2d, at \({n}_{e}=1.35\), the transmission spectrum exhibits a distinct resonance absorption peak at 1461.5 nm with the FWHM of 0.29 nm, corresponding to a Q factor \(Q=5.04\times {10}^{3}\). The simulation results (Fig. 2g) indicate that changes in the refractive index of the environment perturb the field localization of the QBIC mode, resulting in a redshift of the resonance wavelength. As shown in Fig. 2j, at a surrounding refractive index of \({n}_{e}=1.37\) and a resonance wavelength of 1465.3 nm, the structure exhibits a Q factor of \(Q = 3.26 \times 10^{3}\), a refractive index sensitivity of \(S=260\,\text{nm}/\text{RIU}\), and an overall \(FOM = 544\,{\text{RIU}}^{ - 1}\). These findings reveal an inherent trade-off in dielectric metasurfaces while high-Q enhance spectral resolution, the excessive confinement of the electric field within the dielectric limits its interaction with the surrounding sensing medium, thereby restricting sensitivity improvements. This observation aligns well with theoretical predictions regarding the localization characteristics of QBIC modes reported in the literatures36,37,38.

Optimization of unit cell designs for three different dimer configurations and their responses to changes in environmental refractive index. (a) Structure 1: A silicon dimer structure on a silica substrate, serving as a baseline to assess performance differences introduced by nanoporous modifications. (b) Structure 2: A silicon dimer structure on an NSS with 30% porosity, which enhances sensitivity to environmental changes. (c) Structure 3: A further optimized design featuring an NSD with 30% porosity on an NSS (also 30% porosity percentage). This configuration not only strengthens the local electromagnetic field but also improves sensor sensitivity. (d)–(f) Transmission spectra of the three structures measured when \({n}_{e}=1.35\). (g)–(i) Transmission spectra of the three structures as \({n}_{e}\) varies from 1.33 to 1.37. (j)–(l) Calculated refractive index sensitivity \(S\) and FOM for the three structures for different \({n}_{e}\).

To overcome the trade-off between sensitivity and Q factor in dielectric metasurfaces, this study proposes a stepwise optimization strategy. First, as illustrated in Fig. 2b, the dense silicon dioxide substrate is replaced with an NSS featuring a pore diameter of 4.2 nm and a 30% porosity percentage, while the silicon dimer structure remains unchanged. The transmission spectrum for \({n}_{e}=1.35\) can be seen from Fig. 2e. As shown in Fig. 2h,k, this design increases the refractive index sensitivity to \(S=580\,\text{nm}/\text{RIU}\), an improvement of 223% compared to the original structure, and achieves \(FOM=742\,{\text{RIU}}^{-1}\). The results demonstrate that the nanoporous structure effectively lowers the substrate’s refractive index from 1.46 to 1.33, enhancing the refractive index contrast between the substrate and the environment, thereby making the QBIC mode more sensitive to environmental changes.

Furthermore, as visualized in Fig. 2c, we replaced the silicon dimer with a nanoporous silicon nanopillar dimer, featuring a pore diameter of 4.2 nm and a porosity of 30%, thereby forming a dual-nanoporous heterogeneous structure. The transmission spectrum for \({n}_{e}=1.35\) can be seen from Fig. 2f. Simulation results (Fig. 2i,l) indicate that this configuration achieves an ultra-high Q factor of \(Q=5.97\times {10}^{3}\) at 1373.5 nm, while also exhibiting an exceptional sensitivity of \(S=830\text{ nm}/\text{RIU}\). Consequently, the overall FOM reaches up to \(4078\,{\text{RIU}}^{-1}\), which is significantly superior to that of the silicon nanopillar dimer metasurface based on a silica substrate (\(FOM=544\,{\text{RIU}}^{-1}\)), representing a 7.5-fold improvement over its optimum value.

Notably, unlike conventional silicon dimer structures on top of the silica substrate, the dual-nanoporous dimer structure does not exhibit a reduction in its Q factor when the environmental refractive index (\({n}_{e}\)) increases from 1.33 to 1.37, in contrast, the Q factor is further enhanced. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the effective refractive index change induced by the added pores, which redistributes and further strengths the local electric field intensity to optimize the interaction between light and matter. Consequently, even in higher refractive index environments, the structure maintains excellent sensing performance. This feature lays a solid physical foundation for achieving wide-range, high-precision refractive index sensing, effectively resolving the inherent trade-off between sensitivity and Q factor observed in traditional dielectric metasurfaces.

To delve into the underlying physical mechanisms responsible for the differences in refractive index sensitivity among the three metasurface designs, we conducted detailed calculations of the electric field distribution of the QBIC mode at an environmental refractive index of \({n}_{e}=1.35\) (as shown in Fig. 3). The xy-plane electric field distributions at the resonance wavelengths (Fig. 3a–c) clearly demonstrate that the NSD structure, utilizing an NSS, exhibits the most pronounced local field enhancement compared to the other two configurations. Furthermore, analysis of the xz-plane electric field distributions (Fig. 3d–f) indicates that the selection of substrate and dimer materials significantly influences the spatial distribution of the electric field and its contribution to refractive index sensitivity.

Schematic representations of the electric field distributions for three different dimer unit structures under specific environmental conditions. (a–c) The xy-plane electric field distributions at the resonant wavelengths for each unit cell when \({n}_{e}=1.35\). (d–f) The corresponding xz-plane electric field distributions under the same conditions.

Specifically, for the conventional silicon dimer structure on a silica substrate (Fig. 3d), the electric field is primarily concentrated within the substrate and along the surfaces of the dimer pillars. Although this highly concentrated energy distribution yields a high Q factor, the weak interaction between the electric field and the surrounding environment results in a lower refractive index sensitivity. This observation illustrates that while a high Q factor can enhance spectral resolution, an overly localized electromagnetic field distribution limits the evanescent field penetration depth, thereby reducing the overall sensitivity of the sensor.

In contrast, when the silicon dimer is integrated with an NSS (Fig. 3e), it supports quasi-bound states in the continuum, generating highly localized modes that decay evanescently with a decay length dictated by the refractive index contrast. By lowering the substrate’s effective refractive index, the decay on the substrate side is accelerated, which effectively funnels the electromagnetic field into the environment medium. Moreover, the interface between the high- and low-index regions acts as a barrier, significantly reducing energy leakage into the substrate and enhancing field confinement. Notably, the NSD structure built on an NSS (Fig. 3f) not only retains the advantages of the previous configuration but also exhibits a more pronounced local field enhancement. In this optimized design, the electric field is concentrated not only within the dimer gap but also extends into the overlying sensing environment, creating a broader interaction region between light and matter. This expansion enables the sensor to probe a larger volume of the analyte and sensitively capture minute changes in the refractive index. Since the core mechanism of refractive index sensing relies on the interaction between light and the surrounding medium, the enhanced localized field allows more light energy to interact effectively with the medium, significantly boosting both detection sensitivity and precision. This phenomenon explains why the NSD structure on an NSS achieves the highest refractive index sensitivity (\(S=830\text{ nm}/\text{RIU}\)) and outstanding sensing performance.

To further elucidate the field distribution characteristics, we present one-dimensional electric field line profiles extracted from the two-dimensional field maps along \(y=0\) in the xy-plane and \(x=0\) in the xz-plane, as shown in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Information. These profiles provide a more quantitative view of field enhancement, highlighting regions of intense electric field localization. Compared to the conventional design, the NSD structure on an NSS demonstrates a marked shift of field concentration toward the sensing interface and into the environment. This spatial redistribution increases the overlap between the electromagnetic field and the analyte region, thereby improving the sensor’s interaction strength and ultimately enhancing its refractive index sensitivity. These results underscore the critical role of nanostructural and substrate engineering in tailoring the field environment for optimal sensing performance.

Furthermore, we systematically investigated the impact of varying porosity percentages on the sensor performance. Figure 4a illustrates the three-dimensional configuration of the NSD placed onto the NSS. According to effective medium theory, subwavelength nanopores (with pore diameters smaller than \(\lambda /10\)) can be treated as an anisotropic homogeneous medium. Their effective dielectric tensor can be characterized using the effective medium theory as follows45,46:

here \({\varepsilon }_{\text{air}}\) is the dielectric constant of air, \({\varepsilon }_{d}\) the dielectric constant of the dielectric matrix, and \(f\) the porosity.

Optical constants of nanoporous structures, with a focus on the refractive index variation at different porosities. (a) Schematic illustration of the nanoporous structures in silicon and silica, along with the corresponding dimer configuration. (b) and (c) The refractive index of the nanoporous silicon structure in the xy-plane and along the z-direction, respectively (with the pores oriented along the z-axis). (d) and (e) The refractive index variations with porosity for the nanoporous silica structure in the xy-plane and z-direction, respectively.

Figure 4b–e illustrate how the effective refractive indices of nanoporous silicon and nanoporous silica structures vary with porosity. For the nanoporous silicon structure at a working wavelength of 1373.5 nm, as the porosity increases from 10 to 40%, the in-plane effective refractive index (\({n}_{x, y}\)) decreases linearly from 3.21 to 2.46, while the out-of-plane refractive index (\({n}_{z}\)) drops from 3.33 to 2.78. This trend indicates that increasing porosity significantly enhances the anisotropy in the material’s optical properties. Similarly, for the nanoporous silica structure under the same conditions, \({n}_{x, y}\) gradually decreases from 1.435 to 1.316, and \({n}_{z}\) decreases from 1.448 to 1.317. By fine-tuning the porosity, we can precisely control the optical characteristics of the nanoporous structures, thereby effectively optimizing the referred sensor’s performance.

Discussions

Now we will talk about impact of dimer and substrate porosity on optical performance of structures integrated with the NSD and the NSS. Figure 5a–d present the transmission spectra of an NSS with varying porosity percentages (10%-40%) integrated with a silicon dimer structure, where the silicon elements maintain a fixed 30% porosity percentage, under different environmental refractive indices ranging from 1.33 to 1.37. Figure 5e–h illustrate the xz-plane electric field distributions at resonance wavelengths for NSS with varying porosity percentages in an environment with a refractive index of 1.35. As porosity increases, the region of enhanced electric field gradually extends from the substrate into the detection medium, and the field intensity also increases significantly.

Impact of substrate porosity on the optical performance of the structure. (a)–(d) Display the transmission spectra of NSS with porosity percentages ranging from 10 to 40% as \({n}_{e}\) varies. (e)–(h) The xz-plane electric field distributions at the resonant wavelength for NSS with porosity percentages from 10 to 40% as \({n}_{e}=1.35\).

As shown in Fig. 5a, when the NSS has a low porosity percentage (e.g., 10%), its effective refractive index is relatively high, resulting in the absence of distinct resonance peaks in the transmission spectrum under the given structural parameters. As the porosity increases to 20%, resonance peaks become observable. However, because the substrate’s refractive index remains higher than that of the surrounding environment, it cannot effectively suppress the localized field of the QBICs from entering the substrate. As shown in Fig. 5f, a significant portion of the field penetrates the substrate, leading to reduced refractive index detection sensitivity.

Increasing the porosity to 30% further lowers the substrate’s effective refractive index, effectively suppressing the localized field of the QBICs from entering the substrate. As seen in Fig. 5g, most of the field is distributed in the detection medium. However, when the porosity is too high (40%), in a solution environment with an environmental refractive index of 1.37, the Q factor becomes excessively high, making it difficult to observe the transmission peak (Fig. 5d), which is detrimental to the sensor’s signal contrast. Therefore, considering both sensing performance and signal stability, an NSS with 30% porosity is considered optimal.

We previously discussed the impact of substrate porosity on sensor performance. Now, we investigate the role of NSD porosity. Figure 6a–d display the transmission spectra of NSD structures with porosity percentages ranging from 10 to 40%, integrated onto the NSS substrate with a fixed 30% porosity percentage, under various environmental refractive indices (1.33–1.37).

Impact of dimer material porosity on the optical performance of the structure. (a)–(d) The transmission spectra for nanoporous silicon materials with porosity percentages ranging from 10 to 40% as \({n}_{e}\) is varied. (e)–(h) The x–z plane electric field distributions at the resonant wavelength for nanoporous silicon materials with porosity percentages from 10 to 40%, simulated as \({n}_{e}=1.35\).

Theoretical calculations indicate that as the porosity of the silicon dimer increases, the Q factor of the resonance peak significantly improves. This enhancement is attributed to the reduced effective refractive index of the dimer at higher porosities, which intensifies light field localization and strengthens the interaction between light and the analyte.

However, when porosity of NSD reaches 40%, as shown in Fig. 6d, an abnormally high Q factor is observed in a high refractive index environment (\({n}_{e}=1.37\)), leading to an upward shift in the transmission dip position. This shift diminishes the sensor’s signal contrast and may adversely affect detection accuracy and reliability in practical applications.

Further investigation into the electric field distribution reveals that, as shown in Fig. 6e–h, the intensity of the localized field significantly rises as porosity increases. However, excessively high porosity may compromise structural stability and signal accuracy. Considering all factors, an NSD structure with 30% porosity percentage offers an optimal balance, maintaining a high Q factor while ensuring good signal contrast and structural stability.

Conclusion

In this study, numerical simulations were employed to explore the application of nanoporous-material-based metasurfaces in refractive index sensing. The integration of NSS with NSD significantly enhanced mode localization, resulting in more strongly confined QBICs. Additionally, this nanoporous configuration restricted the penetration of localized fields into the substrate, thereby increasing the field distribution within the environmental region and making the QBIC modes more sensitive to environmental changes. We systematically analyzed the optical performance of combined structures with varying porosity percentages of NSS and NSD, including transmission spectra and electric field distribution characteristics, to elucidate the trade-off between the Q factor and sensitivity. The results indicate that a porosity of 30% in both NSS and NSD achieves an optimal balance, ensuring a high Q factor while maintaining good signal contrast. These findings provide important theoretical and technical support for designing high-performance refractive index sensors and advancing the development of high-sensitivity optical sensing technologies based on metasurfaces, with potential far-reaching impacts on frontier fields such as biochemical sensing, quantum optics, and nonlinear optics.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1(9), 16048 (2016).

Azzam, S. I. & Kildishev, A. V. Photonic bound states in the continuum: from basics to applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2001469 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Customizing 2.5d out-of-plane architectures for robust plasmonic bound-states-in-the-continuum metasurfaces. Adv. Sci. 10(7), 2206236 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Plasmonic bound states in the continuum for unpolarized weak spatially coherent light. Photonics Res. 11(2), 260 (2023).

Shalaev, V. M., Boltasseva, A., Kildishev, A. V. & Azzam, S. I. Formation of bound states in the continuum in hybrid plasmonic-photonic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121(25), 253901 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Metasurface engineering through bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 14024 (2019).

Liang, Y. et al. Bound states in the continuum in anisotropic plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 20(9), 6351–6356 (2020).

Gölz, T. et al. Revealing mode formation in quasi-bound states in the continuum metasurfaces via near-field optical microscopy. Adv. Mater. 36(38), 2405978 (2024).

Schiattarella, C. et al. Directive giant upconversion by supercritical bound states in the continuum. Nature 626, 765–771 (2024).

Muhammad, N., Su, Z., Jiang, Q., Wang, Y. & Huang, L. Radiationless optical modes in metasurfaces: recent progress and applications. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 192 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. All-dielectric crescent metasurface sensor driven by bound states in the continuum. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31(46), 2104652 (2021).

Schiattarella, C. et al. High-q photonic aptasensor based on avoided crossing bound states in the continuum and trace detection of ochratoxin a. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 12, 100262 (2022).

Jahani, Y. et al. Imaging-based spectrometer-less optofluidic biosensors based on dielectric metasurfaces for detecting extracellular vesicles. Nat. Commun. 12, 3246 (2021).

Sipahigil, A. et al. An integrated diamond nanophotonics platform for quantum-optical networks. Science 354(6314), 847–850 (2016).

Wang, T., Li, Z. & Zhang, X. Improved generation of correlated photon pairs from monolayer WS2 based on bound states in the continuum. Photonics Res. 7(3), 341–350 (2019).

Bernhardt, N. et al. Quasi-BIC resonant enhancement of second-harmonic generation in WS2 monolayers. Nano Lett. 20(7), 5309–5314 (2020).

Kühner, L. et al. Radial bound states in the continuum for polarization-invariant nanophotonics. Nat. Commun. 13, 4992 (2022).

Wu, M. et al. Bound state in the continuum in nanoantenna-coupled slab waveguide enables low-threshold quantum-dot lasing. Nano Lett. 21(22), 9754–9760 (2021).

Hwang, M. et al. Ultralow-threshold laser using super-bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 12, 4135 (2021).

Fan, K., Shadrivov, I. V. & Padilla, W. J. Dynamic bound states in the continuum. Optica 6(2), 169–173 (2019).

Ha, S. T. et al. Directional lasing in resonant semiconductor nanoantenna arrays. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13(11), 1042–1047 (2018).

Lepeshov, S., Liu, M., Bogdanov, A., Kivshar, Y. & Koshelev, K. Asymmetric metasurfaces with high-q resonances governed by bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121(19), 193903 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. High-q quasibound states in the continuum for nonlinear metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123(25), 253901 (2019).

Yesilkoy, F. et al. Ultrasensitive hyperspectral imaging and biodetection enabled by dielectric metasurfaces. Nat. Photonics 13(6), 390–396 (2019).

Shi, T., Deng, Z., Tu, Q., Cao, Y. & Li, X. Displacement-mediated bound states in the continuum in all-dielectric superlattice metasurfaces. PhotoniX 2, 7 (2021).

You, S. et al. Quasi-bound states in the continuum with a stable resonance wavelength in dimer dielectric metasurfaces. Nanophotonics 12(11), 2051–2060 (2023).

Zhong, H. et al. Toroidal dipole bound states in the continuum in asymmetric dimer metasurfaces. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11(3), 31404 (2024).

Luo, M. et al. High-sensitivity optical sensors empowered by quasi-bound states in the continuum in a hybrid metal–dielectric metasurface. ACS Nano 18(8), 6477–6486 (2024).

Gao, J. et al. Template-free growth of well-ordered silver nano forest/ceramic metamaterial films with tunable optical responses. Adv. Mater. 29(16), 1605324 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Air nanocolumn-SiO2 composite film with adjustable anisotropic refractive index. Mater. Today Phys. 26, 100722 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Vertically-aligned ag nanowire array-based metamaterial with high refractive index and low-dispersion in the infrared band. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12(2), 2301334 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Direct growth of vertically orientated nanocavity arrays for plasmonic color generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30(32), 2002287 (2020).

Becker, J., Trügler, A., Jakab, A., Hohenester, U. & Sönnichsen, C. The optimal aspect ratio of gold nanorods for plasmonic bio-sensing. Plasmonics 5(2), 161–167 (2010).

Sreekanth, K. V. et al. Extreme sensitivity biosensing platform based on hyperbolic metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 15(6), 621–627 (2016).

Li, N. et al. Ultrasensitive metasurface sensor based on quasi-bound states in the continuum. Nanophotonics 14(4), 485–494 (2025).

Xu, Y., Yang, Y., Li, H. & Ren, L. Dynamic colorimetric sensing with all-dielectric metasurfaces governed by bound states in the continuum. J. Mater. Chem. C 13(4), 1747–1756 (2025).

Xu, R. & Takahara, J. Highly sensitive and robust refractometric sensing by magnetic dipole of si nanodisks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120(20), 201104 (2022).

Chen, W., Li, M., Zhang, W. & Chen, Y. Dual-resonance sensing for environmental refractive index based on quasi-BIC states in all-dielectric metasurface. Nanophotonics 12(6), 1147–1157 (2023).

Romano, S. et al. Label-free sensing of ultralow-weight molecules with all-dielectric metasurfaces supporting bound states in the continuum. Photonics Res. 6(7), 726–733 (2018).

Ndao, A. et al. Differentiating and quantifying exosome secretion from a single cell using quasi-bound states in the continuum. Photonics Res. 9(5), 1081–1086 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-quality-factor multiple fano resonances for refractive index sensing. Opt. Lett. 43(8), 1842–1845 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. All-dielectric refractive index sensor based on fano resonance with high sensitivity in the mid-infrared region. Results Phys. 24, 104129 (2021).

Jing, Z., Jiaxian, W., Lizhen, G. & Weibin, Q. High-sensitivity sensing in all-dielectric metasurface driven by quasi-bound states in the continuum. Nanomaterials 13(3), 505 (2023).

Hu, J., Lang, T., Hong, Z., Shen, C. & Shi, G. Comparison of electromagnetically induced transparency performance in metallic and all-dielectric metamaterials. J. Lightwave Technol. 36(11), 2083–2093 (2018).

Elser, J., Wangberg, R., Podolskiy, V. A. & Narimanov, E. E. Nanowire metamaterials with extreme optical anisotropy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89(26), 261102 (2006).

Yan, R. et al. Effective excitation of bulk plasmon-polaritons in hyperbolic metamaterials for high-sensitivity refractive index sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 10(13), 5200–5209 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LY24A040001, LZ25E010001), the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (No. 2024C01243(SD2)) and the Ningbo Youth Science and Technology Innovation Leading Talent Project (No. 2023QL001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W. D., R. X., D. Y., G. W., J. G., H. C. and S. T. wrote the main manuscript text and W. D. and S. T. prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, W., Xin, R., Yang, D. et al. Nanoporous-structured metasurface refractive index sensor employing quasi-bound states in the continuum. Sci Rep 15, 36245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20142-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20142-2