Abstract

To mitigate problems such as injection water channeling, abrupt water breakthrough, rapid decline in oil production accompanied by an abrupt rise in water cut, and poor mobilization of matrix oil that commonly arise in low-permeability fractured reservoirs after conventional water flooding, many Chinese oilfields have implemented chemical profile modification. However, the produced water used to prepare these chemicals contains high concentrations of divalent metal cations especially Fe2+ which dramatically reduce the gel viscosity and thus degrade the conformance control performance. To address this issue, we developed a deep profile conformance control system tailored to the produced water from the Xingshugang block. We optimized both the type and concentration of each component in the formulation: a polymer concentration of 1000 mg/L TS1600; a chromium-based crosslinker at 130 mg/L; thiourea as an oxygen scavenger at 1000 mg/L; 1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-diphosphonic acid (HEDP) as a metal ion chelating agent at 60 mg/L; and formaldehyde as a biocide at 100 mg/L. Laboratory tests demonstrated that, when prepared with produced water, the system forms a gel with a viscosity of 3704 mPa·s, achieves a plugging rate of 86.0%, and contributes to an enhanced oil recovery (EOR) of 17.82%. These results indicate that the proposed deep profile conformance control system exhibits excellent salt tolerance and enhanced profile modification performance in the presence of divalent metal ions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

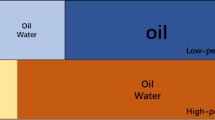

After the industrial production of water flooding and polymer flooding in a major oil reservoir of Xingshugang Oilfield, a large pore flow area appeared. To further achieve enhance oil recovery, salt-surfactant-polymer ternary composite flooding is needed for this type of oil reservoir. In order to improve the utilization rate of chemical agents and reduce ineffective cycles, large-scale deep profile control is required before chemical flooding to block large pores1,2. Commonly used deep profile control and displacement systems include cross-linked polymer weak gels3,4 pre-crosslinked gel particles5,6 colloidal dispersion gels7,8 etc. Among these, weak gel systems were initially applied in the Daqing Oilfield and have been widely implemented in multiple blocks. The polymer within weak gels acts as a displacement phase to mitigate unfavorable mobility ratios during water flooding, thereby improving displacement efficiency and demonstrating remarkable recovery enhancement9,10. This study focuses on weak gel-based profile control agents formulated with polymer-dominated compositions. Deborah et al.11 studied the influence of temperature and sodium chloride concentration on the gelling performance of polyacrylamide/chromium ion weak gel system. The results showed that the gelation time of weak gel system was shortened with the increase of temperature and NaCl concentration. Willhite et al.12 prepared a kind of polyacrylamide/chromium ion type weak gel, which was applied in the field of Arbuckle Oilfield in Kansas, the United States, and measured the reservoir permeability before profile control and flooding, measured the bottom hole flow pressure during profile control and flooding, and calculated the pressure change value after the profile control and flooding measures. The results showed that the water cut of the produced wells was significantly reduced, and the profile control and flooding effect was obvious. However, these problems still exist at present. (1) Deep profile control and flooding measures need to inject large dose of polymer weak gel, which is costly; (2) HCO3− ions and Ca2+ions in the polymer weak gel injected into the formation are easy to scale, and the strength of the weak gel in the formation environment will gradually decline, and the effective period of the measures is short13,14,15,16,17,18. To achieve efficient resource utilization, the movable gel system for deep profile control is prepared with produced water. Due to the aging of pipeline equipment, the produced water has high salinity and is rich in Fe2+, which deteriorates the gelation performance of deep profile control and displacement agent19,20,21. The key factors determining the effectiveness of deep profile control (and displacement) include the system’s shear resistance, gelation viscosity, thermal stability22. The components of produced water have a significant impact on the gelation viscosity of conventional anionic polyacrylamide. When produced water is used as water for weak gel system preparation, the quality of produced water will affect the initial viscosity and long-term stability of polymer. A higher initial viscosity and better viscosity stability (higher viscosity retention) are the key factors to measure whether the produced water treatment system can achieve effective plugging23,24,25,26. Currently, research on utilizing produced water for formulating deep profile control and displacement systems remains relatively limited. Moreover, regarding the influence of Fe2+, existing studies mostly focus on enhancing the salt tolerance of polymers to maintain system viscosity. However, the primary mechanism by which Fe2+ causes damage is actually through initiating free radical reactions that lead to the degradation of the polymer backbone. Therefore, to ensure the effectiveness of profile control and water shutoff, it is of significant importance to further investigate effective treatment methods for metal cations (especially Fe2+) in produced water and to develop compatible profile control and displacement systems27,28,29.

The effects of different components in produced water on the gelling performance of the deep profile conformance control system with anionic polyacrylamide polymer as the main agent are studied systematically. Different types of salt-resistant polymers are selected for comparison with anionic polymers of different molecular weights, and suitable polymer hosts, cross-linking agents and metal cation complexing agents, as well as other components of the deep profile conformance control system are screened. The formulation was systematically evaluated in terms of thermal stability, shear resistance, injectability, and sealing performance to ensure that the formulation of the deep profile conformance profile control system meets the requirements of plugging fractures in low-permeability fractured reservoirs and high-permeability layers, and has good stability. At last, the oil displacement effect of the deep profile conformance control system were evaluated. The deep profile conformance control system suitable for the reservoir physical properties and produced water quality of a certain block in Xingshugang Oilfield was preferred.

Experimental section

Materials

TS1900 (molecular weight: 19,000,000 Da, analytical grade) and TS1600 (molecular weight: 16,000,000 Da, analytical grade) were obtained from Daqing Zaichuang Technology Co., Ltd. TS1200 (molecular weight: 12,000,000 Da, analytical grade) and DS800 (molecular weight: 8,000,000 Da, analytical grade) were acquired from Daqing Chemical Co., Ltd. Thiourea (analytical reagent) and hydroxyethylidene diphosphonic acid (HEDP, 96%) were sourced from Shanghai Eien Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Chromium(III) chloride (CrCl₃, 99%) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃, ≥ 99.5%) were supplied by Shanghai Haohong Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. Lactic acid (80%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%), and aqueous ammonia (25% v/v) were provided by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Aluminum chloride hydrate (AlCl₃·H₂O, ≥ 98%) was procured from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Sodium chloride (NaCl, 99.5%) and phenol (analytical reagent) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. and Shanghai Jizhi Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. respectively. Formaldehyde (≥ 34.5 wt%) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. The produced water used in this study was sourced from reinjection water in the Xingshugang block, with its major ionic components listed in Table 1.

Instruments

Electronic balance (Model ALC-210) was supplied by Sartorius AG. Viscometer (Model LVDV-II + P) was acquired from Brookfield Engineering Laboratories. Thermostatic incubator (ZJ-HK series) was obtained fromSuzhou Zhongjie Electric Heating Equipment Co., Ltd. Rotary vane vacuum pump (Model 2XZ-8B) was purchased from Shanghai First Vacuum Pump Co., Ltd. Mechanical stirrer (Model unspecified) was procured from ZIBO ZHONG RONG Chemical Equipment Co., Ltd. Dual-cylinder constant-rate/displacement pump (Model HBS-S50/70) was sourced fromYangzhou Huabao Petroleum Instrument Co., Ltd. Air compressor (Model OTS-550) was provided by Hebei Xinji Testing Instrument Co., Ltd.

Preparation of crosslinker

Preparation of phenol-formaldehyde resin crosslinker

Phenol (5 g) was placed in a three-necked flask and heated at 50 °C until fully molten. Sodium hydroxide (0.6 g) was then added, and the mixture was stirred for 20 min. Subsequently, 8.6 g of formaldehyde aqueous solution (37 wt%) was introduced, and the reaction temperature was raised to 60 °C and maintained for 50 min. Thereafter, an additional 0.3 g of sodium hydroxide was added, and the reaction was continued at 70 °C for 20 min. A further 2.2 g of formaldehyde solution (37 wt%) was then added, followed by heating to 90 °C and reacting for 30 min (Fig. 1). The resulting product was diluted to a final volume of 100 mL with deionized water to afford a phenol-formaldehyde resin crosslinker solution with a concentration of 56.9 g/L.

Preparation of aluminum-based crosslinker

Deionized water (30 mL) was introduced into a flask, followed by the slow addition of 4.8 g of Al(OH)3·6H2O under continuous stirring until complete dissolution was achieved. A mixed solution of 4.8 g of citric acid and 2.5 g of lactic acid was then slowly added while stirring was maintained. After 4 h of reaction, ammonia solution was added dropwise until the pH reached 3.6–4.1 (Fig. 2). The final solution was diluted to 100 mL with deionized water, yielding an aluminum-based crosslinker with a concentration of 5.4 g/L.

Preparation of chromium-based crosslinker

Chromium chloride (1.6 g) was dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water in a beaker, followed by the addition of 2.7 g of lactic acid under stirring for 30 min. Sodium hydroxide solution was then added gradually until the pH reached 5–6, after which sodium bicarbonate solution was used to further adjust the pH to 6.5-7 (Fig. 3). The resulting solution was aged at 60 °C for 72 h in a thermostatic chamber. Finally, the solution was diluted to 100 mL with deionized water to obtain a chromium-based crosslinker with a concentration of 5.2 g/L.

Viscosity measurement experiment

A specific volume of deep profile control solvent was prepared using a volumetric flask and transferred into a beaker. The pre-weighed polymer was added and dissolved under stirring using a mechanical stirrer. After complete dissolution, the solution was aged without stirring for approximately 2 h. Following the aging period, the polymer solution was stirred again, and the pre-weighed crosslinker was added. The prepared profile control agent was then subjected to an initial viscosity measurement using a rotational viscometer in a 45 °C constant temperature water bath. The sample was subsequently placed in a 45 °C incubator, and its viscosity was periodically recorded to monitor gelation behavior over time.

Injectivity evaluation experiment

The freshly prepared profile control agent was first measured for its initial viscosity using a viscometer and recorded. It was then subjected to mechanical stirring to simulate shear conditions, reducing its viscosity to 50% of the original value. A core sample was vacuumed and saturated with simulated formation water. Water flooding was performed at a constant flow rate of 0.15 mL/min until pressure stabilized, at which point the pressure value was recorded and used to calculate the core’s water permeability. Subsequently, 1 pore volume (1 PV) of the profile control agent was injected at the same flow rate. After pressure stabilization, the value was recorded, and the core was aged in a 45 °C incubator to allow gel formation. After gelation, water flooding was resumed until pressure stabilized again. Based on the pressures before and after gelation, the resistance factor and residual resistance factor were calculated. The plugging rate of the profile control system was determined by comparing the core water permeability before and after treatment.

Core flooding experiment

The core was vacuumed for 6–8 h and saturated with prepared simulated formation water. It was then saturated with residual oil until no water was produced at the outlet and a stable pressure was observed at both ends of the core. The inlet and outlet valves were closed, and the initial water saturation was calculated. The core was placed in a 45 °C incubator for 3 days. Water flooding was conducted at a rate of 0.15 mL/min and stopped when the water cut reached 98%. Deep profile control treatment was then implemented by injecting 0.15 PV of the formulated profile control system according to the experimental plan. The core was then aged at 45 °C for 12 h to allow gelation. After gel formation, post-flooding was performed until no more oil was produced at the outlet, at which point the experiment was terminated (Fig. 4).

Results and discussion

Optimization of polymer type

From a molecular design perspective, enhancing the temperature and salinity resistance of polymers can be achieved through the following strategies: (1) Incorporation of functional structural units with temperature- and salt-resistant properties into the polymer backbone for example, introducing groups into polyacrylamide that inhibit hydrolysis, chelate multivalent cations, and increase the rigidity and hydration capacity of polymer chains; (2) Synthesis of associative polymers with specific interactions between functional groups such as hydrogen bonding, Coulombic forces, and hydrophobic associations resulting in defined molecular and supramolecular structures that endow the polymer with enhanced thermal and salt resistance; (3) Lightly crosslinked polymers, in which the presence of crosslinked structures improves chain rigidity, salt tolerance, and viscosity-building ability. Based on these strategies, five polymers with excellent temperature and salt resistance, namely TS1900, TS1600, TS1200, TS1000, and DS800, were selected for investigation30. The general structures of TS1900, TS1600, TS1200, and TS1000 are shown in Fig. 5a, while that of DS800 is shown in Fig. 5b. All of these polymers contain sulfonic acid groups, which remain dissociated even in high-salinity environments. Their interactions with Na2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ do not lead to precipitation, thereby preventing chain contraction. In addition, the electrostatic repulsion between sulfonic acid groups helps maintain backbone extension and enhances the viscosity of the polymer solution31,32. To evaluate their rheological properties, solutions were prepared using a chromium-based crosslinker and produced water components from the Xing Shugang block (free of iron ions), and the viscosity results are presented in Fig. 6. The TS1900, TS1600, and TS1200 polymers maintained viscosities above 500 mPa·s after 30 days, indicating good gel stability. Although the TS1000 polymer formed a gel within two days, the final gel viscosity was relatively low below 500 mPa·s suggesting limited long-term performance. The DS800 polymer exhibited poor gelation performance, likely due to the short side chain length and the negative influence of certain components in the reinjected produced water, which hindered effective crosslinking with the chromium-based crosslinker. Based on these results, TS1900, TS1600, TS1200 and TS1000, were selected as the candidate polymers for further investigation in subsequent studies.

Optimization of crosslinker type and concentration

Weak gels are characterized by relatively low initial viscosity. By adjusting the type and formulation of the crosslinker, the gelation time can be effectively controlled, allowing the system to pass through small pore throats and reach the deep zones of the reservoir before gelation occurs. This prevents premature plugging near the wellbore and enhances the profile control agent’s ability to penetrate deeper into the formation. Currently, commonly used crosslinkers include phenol-formaldehyde resin crosslinker, aluminum-based crosslinker, and chromium-based crosslinker33,34,35. To identify the most suitable crosslinker, the effect of each on the gelation behavior of polymer TS1600 was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 7, the maximum viscosities achieved by the phenol-formaldehyde, aluminum-based, and chromium-based crosslinking systems were 556 mPa·s, 934 mPa·s, and 3124 mPa·s, respectively. The chromium-based crosslinker system exhibited significantly higher viscosity than the others, primarily because Cr3+ can coordinate with carboxyl groups on the polymer chains. In addition, the hydrolysis of chromium ions in water generates Cr(OH)2+ species, which undergo condensation to form hydroxo bridges (Cr-OH-Cr). These hydroxo bridges, together with the coordination interaction, establish a three-dimensional network36 structure that results in a gel with enhanced stability and viscosity (Fig. 8a). In contrast, Al3+ can only coordinate with polymer chains without forming hydroxo bridges, leading to weaker gel viscosities (Fig. 8b). Similarly, phenolic resin forms covalent bonds with the polymer, but its crosslinking density is limited by the number of functional groups (Fig. 8c), resulting in lower gel viscosities37,38. Therefore, a chromium-based crosslinker was selected, and its concentration was further optimized. As shown in Fig. 9, the viscosity of the system increased with chromium-based crosslinker concentration up to 130 mg/L. Beyond this point, the increase in viscosity was marginal, and at 200 mg/L, a decline in viscosity was observed. This reduction is attributed to the excessive electrostatic shielding effect of surplus chromium ions, which suppresses the necessary repulsive forces between polymer chains. This promotes ineffective aggregation or non-crosslinked associations of polymer chains, ultimately disrupting the uniform gel network and resulting in a physically unstable system with flocculent or precipitated structures. Considering both cost and gel performance, the chromium-based crosslinker concentration of 130 mg/L was selected as the optimal formulation for subsequent applications.

Additives

The performance of weak gel deep profile control systems can be significantly affected by various reservoir factors such as dissolved oxygen, microbial activity, salinity, and metal ions39. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate oxygen scavengers, metal ion chelating agents, and biocides into the formulation to enhance the stability of the deep profile control system in a targeted manner.

Oxygen scavenger

In the gelation system, dissolved oxygen can oxidize Cr3+ to CrO42− and Cr2O72−, both of which lack crosslinking capability, leading to a substantial reduction in gel viscosity. Commonly used oxygen scavengers include phenylphosphonic acid, butylated hydroxytoluene, thiourea, and mercaptobenzimidazole39. Among them, thiourea exhibits structural stability under high-temperature conditions (≤ 150 °C), is not prone to decomposition or deactivation, and is compatible with chromium-based crosslinker without disrupting the crosslinking kinetics40. Therefore, thiourea was selected as the oxygen scavenger, and its effect on gel viscosity at different concentrations was evaluated, as shown in Fig. 10. For the TS1600 profile control system prepared with produced water, the gel viscosity increased with thiourea concentration. During this process, thiourea preferentially reacted with dissolved oxygen, thereby reducing its concentration, significantly slowing down the formation of Cr6+ from the crosslinker, maintaining crosslinking activity, and delaying gelation time. However, when the thiourea concentration exceeded 1200 mg/L, the increase in viscosity became negligible compared to that at 1000 mg/L. Therefore, considering both performance and economic efficiency, a thiourea concentration of 1000 mg/L was selected as optimal for the formulation.

Chelating agent

During the preparation of the gel system, metal ions such as Fe2+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are commonly present in the produced water. These metal ions can shield the electrostatic repulsion along the polymer chains, leading to chain curling and a consequent decrease in solution viscosity. Among them, Fe2+ can further react with dissolved oxygen to generate hydroxyl radicals, which initiate oxidative chain scission reactions of the polymer, resulting in chain breakage and a significant reduction in molecular weight. Therefore, the detrimental effect of Fe2+ on system viscosity is much greater than that of other divalent cations39. To suppress this effect, metal ion chelating agents are typically introduced into the system. By forming chelate complexes with Fe2+, they prevent Fe2+ from reacting with dissolved oxygen to produce radicals. Common chelating agents include phosphates, alkanolamines, aminocarboxylates, hydroxycarboxylates, and organophosphonates. Among them, phosphates decompose at high temperatures, alkanolamines exhibit weak chelation ability, and aminocarboxylates as well as hydroxycarboxylates have poor thermal stability. Organophosphonates, on the other hand, exhibit strong chelation capacity and good thermal stability, but their cost is relatively high. Considering the typically high reservoir temperatures, this study selected 1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-diphosphonic acid (HEDP) as the chelating agent, owing to its superior thermal stability. The chelation mechanism between HEDP and Fe2+ is illustrated in Fig. 11. To further optimize the system performance, the effect of HEDP concentration was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 12. At a concentration of 30 mg/L, the chelation between divalent cations and HEDP was insufficient, resulting in low gel viscosity. As the HEDP concentration increased, the gel viscosity gradually increased. When the concentration reached 90 mg/L, the viscosity exhibited little difference compared with that at 60 mg/L, indicating that the chelation reaction between divalent metal ions and HEDP was essentially complete. Therefore, an HEDP concentration of 60 mg/L was selected for subsequent experiments.

Biocide

Bacteria present in the produced water can degrade the polymer, leading to a decrease in system viscosity39. Formaldehyde, as an efficient and inexpensive biocide, has demonstrated excellent antibacterial performance in practical applications and can effectively inhibit bacterial degradation of the polymer41. Therefore, in this study, formaldehyde was selected as the biocide to suppress bacterial activity, thereby delaying the degradation of the deep profile control system and maintaining its performance stability. A TS1600 polymer-based formulation was prepared using produced water, and formaldehyde was added at concentrations of 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, and 150 mg/L. The duration of gel stability after formation was evaluated, as shown in Fig. 13. The results indicate that system stability improved with increasing formaldehyde concentration. However, the improvement plateaued beyond 100 mg/L, with no significant gain in performance at 150 mg/L. Consequently, the optimal concentration of formaldehyde was determined to be 100 mg/L.

Injectivity and plugging performance evaluation

The plugging performance of four polymer flooding systems TS1000, TS1200, TS1600, and TS1900 (Table 2) was evaluated through core flooding experiments by analyzing injection pressure changes and calculating the residual resistance factor (RRF). Both the RRF and plugging rate reflect the variation in core permeability before and after gel placement, serving as key indicators of a gel system’s ability to reduce the permeability of porous media.

The residual resistance factor (RRF) was calculated using Eq. (1):

where:

\(\:\varDelta\:{P}_{p}\) Pressure differential during initial water flooding.

\(\:\varDelta\:{P}_{w}\) Pressure differential during subsequent water flooding after gel placement.

The plugging rate (\(\:\eta\:\)) was calculated using Eq. (2) :

The core injection pressures and RRFs for the four polymer systems are shown in Fig. 14; Table 3. Results indicate that as the molecular weight of the polymer increases, both the subsequent water injection pressure and plugging rate improve. In particular, TS1900, with the highest molecular weight among the tested polymers, exhibited the most significant plugging effect, achieving a plugging rate of 95.3%. It also recorded the highest post-gelation injection pressure and a residual resistance factor of 21.9.

However, field operations typically consider RRF values above 15 to be problematic, as such high resistance can hinder the subsequent injectivity of chemical flooding agents. Therefore, while TS1900 demonstrates superior plugging performance, its high RRF may present practical limitations42. Consequently, all four systems TS1000, TS1200, TS1600, and TS1900 were retained for further evaluation, with a particular focus on balancing plugging performance and field injectivity requirements.

Thermal stability

The reservoir temperature in the Xingshugang field is 45 °C. To assess the thermal stability of the selected formulations under reservoir conditions, the gelled samples were maintained at 45 °C and their viscosities were monitored for 100 days. As shown in Fig. 15, the TS1000, TS1200, and TS1600 systems exhibited viscosity reductions of 40.47%, 34.38%, and 26.49%, respectively, relative to their peak gel viscosities (attained on Day 5). Despite these declines, the residual viscosities remained comparable to the initial gel strengths, demonstrating that all three formulations possess good thermal stability at 45 °C.

Oil recovery performance

Following polymer screening, core-flooding tests were conducted using the TS1000, TS1200, and TS1600 formulations at the ratios specified in Table 2. The oil recovery curves are presented in Fig. 16. During the initial water‐flooding stage, both water cut and oil recovery rose rapidly with injected pore volumes, then gradually plateaued. Prior to chemical injection, the water‐flood recoveries for the TS1000, TS1200, and TS1600 systems were 33.58%, 32.45%, and 29.22%, respectively. Upon injection of the salt-ternary emulsion systems, a pronounced reduction in water cut was observed compared to the salt-ternary system alone. After subsequent water‐flooding, the cumulative recoveries using TS1000, TS1200, and TS1600 reached 45.88%, 47.64%, and 47.04%, corresponding to EOR of 12.53%, 15.19%, and 17.82%. Of the three, the TS1600 system achieved the highest EOR performance.

Comparison with previous studies

We reviewed recent studies aimed at improving the stability of gel systems when using produced water containing Fe2+ (Table 4). Tang et al.43 enhanced the salt tolerance of polymers to mitigate the charge-shielding effect of Fe2+, but this approach failed to address polymer backbone degradation caused by Fe2+-induced free radicals. Zheng et al.37 introduced oxidizing agents to convert Fe2+ into Fe3+; however, this method may exacerbate the susceptibility of Cr3+ to oxidation, thereby eliminating its crosslinking activity. In contrast, the present work prevents free-radical formation through the chelation of Fe2+ by HEDP, and further enhances system stability with the addition of thiourea and formaldehyde. Compared with previous studies, the proposed system demonstrates superior viscosity retention and plugging rate (Table 4).

Conclusions

The experimental results indicate that TS1900, despite producing very high gel viscosity, cannot penetrate the matrix pore throats and thus is unsuitable for deep profile conformance control system. Conversely, DS800 yields insufficient viscosity due to the inhibitory effects of produced water constituents on gelation and also fails to meet performance requirements. The optimized profile control system comprises TS1600 polymer crosslinked with 130 mg/L chromium-based crosslinker, 1000 mg/L thiourea as oxygen scavenger, 60 mg/L HEDP as metal-ion chelator, and 100 mg/L formaldehyde as biocide. Among the candidates, the TS1600 formulation demonstrated the best overall performance: a core plugging rate of 83.9%, only a 26.49% viscosity loss after 100 days at 45 °C, and an EOR of 17.82%.

The system developed in this study was primarily designed to address the viscosity reduction of gel profile control systems caused by Fe2+ in produced water. By screening appropriate crosslinkers and polymers, the target viscosity was achieved. In terms of additives, thiourea was employed as an oxygen scavenger to prevent the oxidation of Cr3+, HEDP was introduced as a chelating agent to inhibit Fe2+ induced radical generation and subsequent polymer degradation, and formaldehyde was used as a biocide to suppress the microbial degradation of polymers in produced water. This work provides a reference for preparing gel profile control systems using produced water with high Fe2+ concentrations. However, the current formulation employs formaldehyde as the biocide, which is associated with certain toxicity. Therefore, future development of the system should focus on exploring less toxic alternatives to replace formaldehyde.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

References

Dong, L. et al. Study on the plugging ability of polymer gel particle for the profile control in reservoir. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 37, 34–40 (2015).

Abe, K., Seddiqi, K. N., Hou, J. & Fujii, H. Experimental performance evaluation and optimization of a weak gel Deep-Profile control system for sandstone reservoirs. ACS Omega. 9, 7597–7608 (2024).

Chang, H. L. et al. Successful field pilot of in-depth colloidal dispersion gel (CDG) technology in Daqing oil field. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 9, 664–673 (2006).

Jiang, J., Rui, Z., Hazlett, R. & Lu, J. An integrated technical-economic model for evaluating CO2 enhanced oil recovery development. Appl. Energy. 247, 190–211 (2019).

Li, J. G. et al. Application of profile control and displacement of aluminum crosslinking dispersed gel in Daqing oilfield after polymer displacement. 26 (2004).

Shi, J. et al. Viscosity model of preformed microgels for conformance and mobility control. Energy Fuels. 25, 5033–5037 (2011).

Zhang, J., Wang, S., Lu, X. & He, X. Performance evaluation of oil displacing agents for primary-minor layers of the Daqing oilfield. Pet. Sci. 8, 79–86 (2011).

Surguchev, L., Koundin, A., Melberg, O., Rolfsvåg, T. A. & Menard, W. P. Cyclic water injection: improved oil recovery at zero cost. Pet. Geosci. 8, 89–95 (2002).

Xu, B., Zhang, J. & Hu, X. The delayed crosslinking amphiphilic polymer gel system based on multiple emulsion for in-depth profile control. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 38, 1242–1246 (2017).

Sun, F. et al. Effect of composition of HPAM/Chromium(III) acetate gels on delayed gelation time. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 37, 753–759 (2015).

Jordan, D. S., Green, D. W., Terry, R. E. & Willhite, G. P. The effect of temperature on gelation time for polyacrylamide/chromium (III) systems. Soc. Petrol. Eng. J. 22, 463–471 (1982).

Willhite, G. P. & Pancake, R. E. Controlling water production using gelled polymer systems. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 11, 454–465 (2008).

Chang, Y. Deep Conformance Control Technology for Fractured Reservoirs: Development and Application. Degree thesis (Southwest Petroleum University, 2006).

Bai, B., Liu, X. & Li, Y. Recent advances in chemical conformance control technologies for Chinese oilfields. Oil Drill. Prod. Technol. 20, 64 (1998).

Li, Z., Yang, G. & Song, J. Development of a weak-gel deep fluid diversion and displacement agent for high water-cut oil and gas reservoirs. Nat. Gas Technol. Econ. 3, 46–48 (2009).

Zhang, Y. Factors influencing the gelation performance of weak-gel systems. Nat. Gas Oil 31, 70 (2013).

Dai, C. et al. Influencing factors of delayed cross-linking system in deep profile control. J. J. China Univ. Pet. 34, 149 (2010).

Yao, E. et al. High-temperature-resistant, low-concentration water-controlling composite cross-linked polyacrylamide weak gel system prepared from oilfield sewage. ACS Omega. 7, 12570–12579 (2022).

Wang, K., Kong, H., Fu, G. & Li, W. Gelation behavior of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide/chromium lactate in oilfield produced water. Oilfield Chem. 33, 240–243 (2016).

Fu, T. Research on depth profile control optimization technology under the condition of suitable for sewage of Chaoyang ditch oil field. Degree thesis (Northeast Petroleum University, 2013).

Khormali, A., Ahmadi, S., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Karami, A. Evaluating the efficacy of binary benzimidazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel using multi-modal analysis and optimization techniques. Results Eng. 26, 104671 (2025).

Zhao, X., Yu, Q., Yan, F., She, Q. & Yang, C. Formulation and performance evaluation of an organochromium weak-gel system for deep profile control. Special Oil Gas Reserv. 20, 114 (2013).

Terry, R. E., Huang, C., Green, D. W., Michnick, M. J. & Willhite, G. P. Correlation of gelation times for polymer solutions used as sweep improvement agents. Soc. Petrol. Eng. J. 21, 229–235 (1981).

Yuan, G. & Luo, H. Review of influences of sewage water quality on polymer solution viscosity. Chem. Eng. 33, 73–78 (2019).

He, R. Experimental study on the combination of deep conformance control and cyclic water injection to improve the oil recovery of lowpermeability fractured reservoirs. Degree thesis (Northeast Petroleum University, 2021).

Yuan, R., Li, Y., Li, C., Fang, H. & Wang, W. Study about how the metal cationic ions affect the properties of partially hydrolyzed hydrophobically modified polyacrylamide (HMHPAM) in aqueous solution. Colloids Surf., A. 434, 16–24 (2013).

Gaillard, N., Giovannetti, B. & Favero, C. Improved Oil Recovery using Thermally and Chemically Protected Compositions Based on co- and ter-polymers Containing Acrylamide. Paper presented at the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA (2010).

Wu, C., Dong, H., Su, G., Yang, H. & Yu, X. The effect of the structure of functional monomers on the resistance of copolymers to Fe2+ and S2. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 212, 110309 (2022).

Ahmadi, S., Khormali, A. & Kazemzadeh, Y. A critical review of the phenomenon of inhibiting asphaltene precipitation in the petroleum industry. Processes 13, 212 (2025).

Zhao, X., Yu, Q., Yan, F. & She, Q. Study and performance evaluation of deep profile control system of organic chromium week gel. Special Oil Gas Res. 3, 114–117 (2013).

Jiang, H. et al. Amphiphilic polymer with ultra-high salt resistance and emulsification for enhanced oil recovery in heavy oil cold recovery production. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 252, 213920 (2025).

Artykova, Z., Beisenbayev, O., Issa, A. & Kydyraliyeva, A. Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids. Open. Eng. 15, 20240097 (2025).

Fang, J. et al. Research progress of high-temperature resistant functional gel materials and their application in oil and gas drilling. Gels 9, 34 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Functional gels and chemicals used in oil and gas drilling engineering: A status and prospective. Gels 10, 47 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. The advances of organic chromium based polymer gels and their application in improved oil recovery. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 282, 102241 (2020).

Dang, Z., Zhang, G., Lai, X., Wang, L. & Wang, L. Preparation and evaluation of polyacrylamide plugging gel for high salinity oilreservoir. Fine Chem. 1, 11 (2025).

Zheng, M., An, K., Fan, G. & Li, W. Adaptability of polymer gel with oilfield wastewater. Chem. Bioeng. 34, 46–49 (2017).

Cheng, L. et al. Development of a high-strength and adhesive polyacrylamide gel for well plugging. ACS Omega 7, 6151–6159 (2022).

Cao, G. et al. Research on the formulation system of weak gel and the influencing factors of gel formation after polymer flooding in Y1 block. Processes 11, 1405 (2022).

Qiao, W., Zhang, G., Jiang, P. & Pei, H. Investigation of polymer gel reinforced by oxygen scavengers and Nano-SiO2 for flue gas flooding reservoir. Gels 9, 268 (2023).

McLelland, W. G. Results of Using Formaldehyde in a Large North Slope Water Treatment System. Paper presented at the SPE Western Regional Meeting, Anchorage, Alaska, May (1996).

Yuan, F., Song, Q., Ji, F. & Li, H. Seepage and oil displacement rules of polymers with different curing degrees in porous media. Oilfield Chem. 41, 288–295 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Experiment and application of movable gel prepared by recycled produced water. IOP Conf.Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 474, 052098 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 12002083 for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Y.: Investigation Writing—original draft, Review & Editing; G. C.: Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing; Y. L.: Investigation Writing—original draft, Review & Editing; T. H.: Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, S., Cao, G., Lin, Y. et al. Deep mobile profile control agent for iron-containing reservoirs prior to salinity-based ternary flooding. Sci Rep 15, 36224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20164-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20164-w