Abstract

Development of sustainable tourism in the environmentally sensitive mountain regions is a challenging issue that deals with economical, natural, and cultural benefits along with preservation of social-ecological system. Today, the Indian Himalayan Region is experiencing reasonable growth in the pilgrimage tourism sector that necessitates an assessment of carrying capacity and sustainable practices. The present study evaluates the eco-tourism potential and sustainable tourism initiatives in the Char Dham (four shrines) in Uttarakhand state, where tourist numbers have grown from 1 million annually in the early 2000s to over 3 million recently, with a record 5 million visitors in 2023. The research employs multiple criteria decision analysis (MCDA) including geoscientific, bioscientific, socioeconomic, and cultural-historical analyses with 21 sub-indicators. Key findings of the work revealed the tourist carrying capacity of the areas with sustainable daily limits of 15,778 for Badrinath, 13,111 for Kedarnath, 8178 for Gangotri, and 6160 for Yamunotri Dham. Further, correlation analysis between other sub indicators revealed significant positive relationships between natural geosites, economic indicators (MPCE: r = 0.987, p = 0.013; monthly income: r = 1, p < 0.0001), and tourist influx (r = 0.823, p = 0.177), particularly in the areas with high temple concentrations (r = 0.636, p = 0.36). The site suitability assessment results showed varying degree of ecotourism development potential across the study sites. The work provides a comprehensive framework aiming at sustainable tourism harmonizing with local economies and surrounding environment. Recommendations of the work are associated with decentralised, community driven, and eco-friendly tourism strategies aligned with the UN SDGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable tourism has become a cornerstone of global sustainability efforts, contributing significantly to the economy and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The industry accounts for 10% of global GDP and employs one in ten people worldwide, impacting SDGs 12, 8, and 141,2. In this aspect, ecotourism has emerged as a practical approach to balance conservation and economic development3. Further, mountain tourism, representing 15–20% of global tourism, is crucial for sustainable development, with 400–500 million annual visitors4. However, uneven distribution highlights the need for more equitable practices1. Recent sustainable tourism research emphasizes adaptive management strategies to address global challenges like climate change and post-pandemic recovery5,6. Nowadays, the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in the tourism management sector has proven as one of the efficient tools. GIS techniques, viz., overlay analysis, proximity assessment, and terrain analysis are widely used for tourist site suitability, accessibility, and assessment of tourist movement patterns7. The complex relationships between the spatial pattern and trends of tourist arrivals are reported to be analysed with analysis of satellite imagery and digital elevation model along with other factors like temperate and rainfall8. Further, advanced techniques, e.g., geographically weighted regression is also reported with management of tourists using strategies like spatial distribution of accommodation prices9. GIS tools are also reported with the enhancement of informed decision making in areas including sustainable tourism management, resource allocation and destination planning10.

The concept of regenerative tourism has gained attraction, aiming to create positive net impacts on communities and ecosystems, offering a holistic vision for the future of tourism11,12. Further, integrating carrying capacity assessment and strategic planning is also essential for sustainable tourism13,14. Tourism has grown significantly in recent years in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR). In 2022, India hosted about 4.38 million foreign tourists, 106% increase from 2021, and 1,731 million domestic tourists, up from 677 million in 202115. The Kashmir valley witnessed over 1.1 million visitors annually in the last decade (2011–2020). The report also highlights that pilgrim tourism to major shrines like Shri Amarnath Holy Cave and Mata Vaishnav Devi is significantly higher than other forms of tourism, with annual pilgrims ranging from 0.22 million to 11.12 million per annum. Similarly, the Char Dham (four main pilgrimage sites) in Uttarakhand received an estimated 3,477,957 pilgrims in 2019, though this number dropped sharply in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic16. The growing popularity of mountain pilgrimage destinations, coupled with improved accessibility, has led to substantial increase in visitor numbers over the years, presenting both opportunities and challenges for sustainable tourism management in these ecologically sensitive areas.

In need of promoting eco-tourism and/or sustainable tourism, the objectives of the present work are to evaluate eco-tourism potential and promotion of sustainable tourism initiatives in and around the Char Dham (i.e., Kedarnath, Badrinath, Gangotri and Yamunotri) areas of Uttarakhand, India. In the present work, site suitability assessment and sustainable tourism management planning was done for the Char Dham areas considering 10 diverse indices and simultaneously, estimation of tourist carrying capacity and action planning have been also done for promotion of sustainable tourism in the respective areas. The work addresses the gap in the comprehensive tourism assessment for site specific carrying capacity. Novelty of the work lies with the use of multi scale framework for the assessment of site stability that includes wide range of indices starting from climatic variables up to socioeconomic variables of the area. The work also uniquely aligns with UN-SDGs and offers practical, future-oriented recommendations for the study area, that can be further applicable for the sustainable development of alike pilgrim tourist sites. The study will be a valuable scientific and policy tool, providing recommendations for sustainable tourism planning in India and other alpine pilgrimage or heritage destinations across the world.

Study area

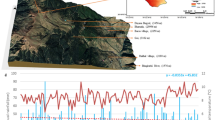

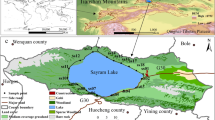

The study area of the present work includes four holy shrines of Char Dham (also known as ‘four abodes’) in Uttarakhand in the northwestern Indian Himalaya (Fig. 1). The Badrinath shrine township is located between the coordinates 30°41′45″ N to 30°45′20″ N latitudes and 79°21′10″ E to 79°32′45″ E longitudes, situated along the River Alaknanda at an altitude of roughly 3,133 m above average mean sea level (amsl). Covering an area of approximately 4.5 km−2, it spreads from Deodarshani in the south to Mana village in the north17,18. Beginning at the meeting point of the Satopanth and Bhagirath Kharak glaciers close to Alkapuri Bank (3,680 m), the River Alaknanda is a significant tributary of the Ganga system. It joins the River Saraswati at Keshav Prayag, which is close to Mana hamlet. The shrine is open from May to November every year. As compared to the local population of roughly 2,500, it draws a sizable number of pilgrims and tourists annually, estimated to be 0.65 million. Badrinath is surrounded by prominent peaks including Nar Parvat (5,828 m), Narayan Parvat (5,965 m), Neelkanth (6,597 m) and Urvashi (4,306 m) and is located in a wide glacial valley of the River Alaknanda19. Among the Char Dham pilgrimage sites, Kedarnath exists with great religious significance in Hinduism. It is situated 3,533 m above mean sea level between 30°44′05″ N and 79°04′02″ E latitude and longitude, respectively. The Chorabari Glacier and its surrounding glaciers, which supply water to the River Mandakini, are close to the temple20. Due to harsh weather conditions, the shrine is accessible only from April to November. The Higher Himalayan Crystalline (HHC) zone, where Kedarnath is located geologically, is primarily composed of high-grade metamorphic rocks with sporadic granite intrusions. These rocks were created under circumstances ranging from amphibolite to lower granulite facies21. Steep topographical gradients define the region, particularly in the vicinity of the Main Central Thrust (MCT), a prominent tectonic border demarcated by river knickpoints that divides the Lesser and Higher Himalayas22. Since the Kedarnath region is situated inside the Himalayan seismic belt and is hence vulnerable to earthquake-related hazards, it is significant from a seismotectonic perspective23. The Gangotri pilgrimage route, which is recognised as an environmentally sensitive area, spreads approximately 4,179.59 km² along the River Bhagirathi watershed in the Uttarkashi district of the Garhwal Himalaya, from the town of Uttarkashi (1,158 m) to the Gomukh Glacier (3,600 m)24. Here, high-altitude lakes like Dodital, Sahastra Tal, and Reinsara Tal, as well as alpine meadows like Dayara Bugyal25, are among the main natural attractions. Every year, from March to November, a large number of Hindu pilgrims visit to the Gangotri shrine26. The River Yamuna is the primary inspiration for the name of the Yamunotri shrine. Located in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand, at coordinates 30.999653° N and 78.462861° E, at an elevation of roughly 6,387 m msl, the Yamunotri shrine is primarily known for the River Yamuna, which rises from the Yamunotri Glacier. This glacier is situated on the western section of the Banderpoonch peaks27. According to geology, the region is a portion of the higher Himalaya, which is structurally thrust along the MCT over the rocks of the Lesser Himalaya.The lithology of the region mainly consists of marble, augen gneiss, and garnet-bearing mica schist, linked to the Munsiari Formation, Chakrata Formation, Rautgara Formation, and Mandhali Formation. The Munsiari, Chakrata, Rautgara, and Mandhali formations are associated with lithology of the region, which is primarily composed of marble, augen gneiss, and garnet-bearing mica schist28,29,30.The boundaries of each shrine were determined within a radius of 10 km from the main river incorporating buffer of the concerned river segment31. The buffer zone is based on a concept of EIA study (Environmental Protection Rules, 1986) in India for the protection and management of natural resources32. Drainage layer was downloaded from open street map data files (http://gis.geojamal.com). In ArchGIS, buffer tool was used to delineate 10 km buffer around the drainage features of the Char Dham.

Study area- geographical expanse and elevation profile of the Char Dham shrines (generated using ArcGIS software (ESRI, CA, USA), https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/trial; Data source: AlOS PALSAR DEM).

Results and discussion

Analysis of thematic layers

Geospatial characteristics of the Char Dham

Geospatial characteristics play a crucial role in mountain tourism by providing valuable insights into terrain, accessibility, and environmental factors that influence visitors’ experience and management of destinations33,34. During geospatial analysis, 3 geological indices were evaluated including elevation, slope, and vegetation cover. Elevation and slope together play an important role in the development of ecotourism sites. As elevation increases, the oxygen content in air falls due to rarification and the likelihood of human survival becomes difficult. Thus, it indicates that relatively lower elevation and slope aspects have higher possibilities of potential for developing ecotourism sites35. In view of the present study, area covered > 4200 m (high) is considered to be less suitable for tourism development. Presence of high altitude area was estimated to be highest in Gangotri (60.69%) followed by Badrinath (49.03%), Yamunotri (44.79%) and Kedarnath (23.37%). In case of slope, area having < 33 degree slope is considered to be suitable for tourism activities. Existence of such area was found to be highest in Badrinath (53.59%) followed by Gangotri (53.31%), Kedarnath (44.57%), and Yamunotri (37.15%). Thereafter, highest area in terms of vegetation cover, was obtained in Yamunotri (54.15%) followed by Kedarnath (47.68%), Badrinath (15.37%) and Gangotri (12.67%) (Table 1).

Change in snow cover in the glaciers and drainage profile

The changing snow cover in glaciers and altered drainage profiles significantly impact mountain tourism by affecting both winter and summer recreational activities. Recent studies have shown that reduced snow cover and glacial retreat not only shorten ski seasons but also lead to increased geohazards and landscape changes, altering hiking trails and mountaineering routes36. Furthermore, these cryospheric changes influence water availability for artificial snow production and other tourism-related infrastructure, necessitating adaptive strategies for sustainable mountain tourism development. In the present study, using monthly maximum snow covered area (SCA) data from August to October, the “snow cover summary” for the glacier regions of each Dham over the period of 18 years, from 2002 to 2020, was analysed. Simultaneously, snow covered area of the four famous glaciers in and around four shrines were analysed. These were: Chorabari Bamak glacier (Kedarnath, 11.91 km2), Bhagirath Kharak glacier (Badrinath, 57.3 km2), Gangotri glacier (Gangotri, 219.97 km2), and Yamunotri glacier (Yamunotri, 2.67 km2). Figure 2 shows SCA for all the glaciers and results depicted that retreat in SCA is the highest in the Gangotri glacier (22.36 m year−1) followed by Yamunotri (20 m year−1), Badrinath (17.32 m year−1) and Kedarnath (14.14 m year−1) during the period 2002–2020 (Fig. 2). In view of determining the distance between drainage networks and ecotourism sites, reclassification process was used. The results reveal that Yamunotri and Gangotri places have an area about 167.36 sq.km. under suitable sites followed by Kedarnath (145.41 sq.km.) and Badrinath (99.98 sq.km.).

Climate

Climate profiles play a crucial role in mountain tourism by influencing visitors’ experiences, activity planning, and destination management strategies. Recent studies have shown that changing climate patterns in mountainous regions are altering traditional tourism seasons, necessitating adaptive measures by tourism operators and policymakers to ensure the long-term sustainability of mountain destinations 37, 38. Furthermore, given the rise in extreme weather events22 like cloudbursts occurred at many places and natural hazards linked to climate change, precise climate profiling has become crucial for risk assessment and mitigation in mountain tourism. Analysis of the climate data (1990–2020) indicates that significant increasing trend (p < 0.01) in the temperature is noticeable in all the sites for three seasons; pre-monsoon (March-May), monsoon (June-September), and post-monsoon (October-November). However, no significant trend was observed for the winter season (December-February) in all the sites. These sites show similar magnitude of temperature changes; 0.041–0.058 °C/year for the pre-monsoon season, 0.022–0.027 °C/year for the monsoon season, and 0.044–0.051 °C/year for the post-monsoon season during the period 1990–2020. Trend analysis of precipitation data showd no significant trend for all the sites except for significant increasing trend in monsoon season for the Yamunotri site where an increase of 9.79 mm/year was observed (Fig. 3; Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Biodiversity

Protected and geologically diverse landscapes represent the beauty of undisturbed nature, and thus, it attracts significant number of tourists, enthusiasts, and nature lovers. In accordance with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a protected area is an unambiguous designated and managed geographical region that is legally or otherwise effectively regulated in order to safeguard ecological services and cultural values associated with nature over the long run39. Further, biodiversity plays a crucial role in mountain tourism by providing unique and diverse ecosystems that attract visitors and support a wide range of recreational activities. The rich variety of flora and fauna in mountain regions not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of these destinations but also contributes to their ecological resilience, making biodiversity conservation essential for the long-term sustainability of mountain tourism40,41. Badrinath shrine lies in the Nanda Devi National Park (82.80% of the total coverage of the study area), Kedarnath in the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (37.73% coverage), Gangotri in Gangotri National Park (10.25% coverage), whereas Yamunotri lies within the proximity of Govind Pashu Vihar National Park and Sanctuary (1.15% coverage).

Geodiversity, places of natural and cultural attraction

Geodiversity concerns about the number and variety of structures such as sedimentary, tectonic, geological materials, minerals, rocks, fossils, and soils. Geodiversity constitutes the substratum in a region, above which the organic activity is settled, wherein the anthropic included. In the present study, geosites were analysed considering two classes, over surface (peaks, glaciers, etc.), and sub surface (caves, hot springs). In total, 5 (over surface) and 6 (sub-surface) tourist sites were identified in Badrinath, 3 (over surface) and 2 (sub-surface) in Kedarnath, 5 (over surface) and 4 (sub-surface) in Gangotri and 3 (over surface) and 4 (sub-surface) in Yamunotri under geo-diversity class. Simultaneously, 5 unique natural sites (alpine pastures, lakes, hill villages) and 10 temples were found in Kedarnath, 7 sites and 6 temples in Badrinath, 10 sites and 3 temples in Gangotri and 6 sites and 1 temple in Yamunotri (Table 2).

Socio-economic status of the local communities

In spite of high influx of tourists, the socio-economic profile of these districts, wherein Char Dham falls, need to be met according to their expectation. According to the Census of 2011, the three districts with the largest populations were Rudraprayag with 2,42,285 (95.87% rural), Uttarkashi with 3,30,086 (92.73% rural), and Chamoli with 3,91,605 (84.69% rural). Wherein, 80.10% of the total population in Uttarkashi, 60.07% of the total population in Chamoli and 53.74% of the total population in Rudraprayag have less than 58.15 USD per month income of a rural household. Among the three districts, Chamoli has the highest number of below poverty line (BPL) families (8.26%) followed by Uttarkashi (8.54%) and Rudraprayag (8.72%). The importance of the study directly reflects the poverty level of the rural poor in terms of income. The Monthly PerCapita Consumer Expenditure (MPCE) of Uttarakhand state, which measures monthly expenditure in Indian rupees, places Uttarkashi in the upper middle poverty group and Rudraprayag and Chamoli in the lower middle poverty group. Whereas, in urban sector of Uttarakhand, Chamoli comes in the lower middle and rest of the two districts fall in the upper middle poverty group (Fig. 4).

Carrying capacity analysis and planning

Tourist carrying capacity

A comprehensive analysis of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Yamunotri and Gangotri is important in terms of assessing inter variability in different aspects of tourism. The current analysis estimates that the actual carrying capacity of the Char Dham for Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri is somewhere between 11,833 and 15,778, 9833 and 13,111, 6133 and 8178, and 4620 and 6160 visitors day−1, respectively (Table 3). According to the information of Department of Tourism, Uttarakhand, during 2021, 243,012, 199,409, 3377 and 33,311 tourists visited Kedarnath, Badrinath, Gangotri and Yamunotri, respectively. The estimation of ~ 1185 visitors day−1 in Kedarnath, ~ 973 visitors day−1 in Badrinath, ~ 165 visitors day−1 in Gangotri and ~ 162 visitors day−1 in Yamunotri showed variability in terms of inflow of tourists. These numbers are fewer because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, if tourists influx for the year 2019 is taken into account, tourist influx estimated to be ~ 6073 visitors day−1 in Badrinath, ~ 4878 visitors day−1 in Kedarnath, ~ 2586 visitors day−1 in Gangotri and ~ 2271 visitors day−1 in Yamunotri (Fig. 5). If we consider the tourist influx from the last 24 years (2000–2024), the visitors have been increased at a rate of 28,784 visitors year−1 in Badrinath, 39,671 visitors year−1 in Kedarnath, 28,784 visitors year−1 in Gangotri, and 28,784 visitors’ year−1 in Yamunotri.

Therefore, the results vividly indicate that the areas are associated with high tourism potential throughout the year. Thus, promotion of sustainable tourism in these areas is a need of the hour within certain regulations in peak season. A comprehensive strategy would simultaneously involve decentralization in nearby satellite locations with the aim of ensuring the ecological and economic security of the area and local communities.

Site suitability assessment and correlation analysis

Based on the analysis of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), site suitability assessment score was estimated for all the Char Dham by considering the field values for all categories and the weightage calculated by the AHP process.

Three suitability classes—highly suitable (1.88–2.68), moderately suitable (0.94–1.88), and marginally suitable (0-0.94)—were represented in each Dham. In Badrinath, Kedarnath and Yamunotri, 42%, 37% and 38% area comes under low suitability zone, followed by 35%, 34% and 37% area under moderate, and 23%, 29% and 25% area under highly suitable zone, respectively (Table 4). In view of the analysis of the results and ecotourism criteria, the recommended sites for ecotourism circuits are succinctly categorized into three groups (Supplementary Table 3). Sites located in zones with significant potential for ecotourism are categorized as highly suitable. By adhering to regulatory restrictions and guidelines, these sites and the associated classified areas could function as the primary ecotourism attractions. Guidelines that might be enforced at these locations encompass restrictions on tourist movement beyond the carrying capacity and rigorous monitoring regarding adherence to the code of conduct. The moderate suitable category, which stands for “moderately ecotourism potential,” grants permission for moderate development, albeit with significant emphasis on meticulous environmental impact assessment and planning for construction work. The aforementioned regions may continue to be classified as ecotourism hotspots on account of passive tourist pursuits, including camping, hiking, bird watching, and site exploration, which involve minimal alteration or derivation from the area. The marginal suitable category, which stands for “marginally suitable for tourism development,” comprises areas that are exceptionally sensitive to ecological changes. Nonetheless, development should be carried out in such a manner that is suitable in terms of reducing the adverse effects on infrastructures. In these regions, one ought to refrain from developing physical structures such as green hotels, lodges, restaurants, and public convenience facilities.

During correlation analysis, significant positive correlation was observed between the parameters unique natural geosites over surface (peaks, glaciers, etc.) and MPCE (Fig. 6) which indicate (r = 1, p < 0.0001) the economic condition of the areas which has positive correlation with unique natural geosites. Further, the parameters depict strong positive correlation with the current tourist influx of the area which include number of temples (r = 0.962, p = 0.038), rural MPCE (r = 0.987, p = 0.013), and monthly income (r = 0.987, p = 0.013). The results vividly indicate the current tourist influx of the areas is mainly dependent on the presence of temples. Simultaneously, estimated tourist carrying capacity of the areas also shows strong positive correlation with the monthly income of the rural households (r = 1, p < 0.0001) and positive correlation with temples (r = 0.636, p = 0.36), rural MPCE of the respective districts (r = 0.905, p = 0.095), and current tourist influx (r = 0.823, p = 0.177). Other parameters like geosites and landscape sites like alpine pastures of the areas depict very less or negative correlation with the present tourist influx indicating the necessity of establishment of nature-based tourism (NbT) in these ecologically sensitive areas.

Discussion

The Char Dham Yatra (journey) significantly contributes to the economy of Uttarakhand state, generating approximately USD 888 million annually and employing 50,000 people42. However, the increasing number of visitors in Char Dham, reaching over 4 million pilgrims in 202243 and an estimation approximately 6 million in 2025 raise prime environmental and management concerns. Kedarnath, alone producing 1.5-2.0 tonnes of daily waste during peak season44,45, aims at launching different waste to energy initiatives like microbial biocomposting from biowaste, reuse of non-biodegradables for developing small waste eco-parks, etc. for promoting sustainable tourism, and balancing economic benefits with ecological preservation. To manage tourism in the area sustainably, the most effective scientific methods is “nip in the bud” approach that needs to be practised at the source of waste or any other pollution generation, together with stringent enforcement of current regulations. The findings of the present study depict the vital interaction mechanism among geospatial analysis, impacts of climate change, socioeconomic elements, and carrying capacity analysis for sustainable tourism development in the Char Dham area. The study region shows varying degrees of tourism compatibility based on vegetation cover, slope, and elevation. Lower elevations, omitting valley bases on either side with a minimum of 100 m, and moderate slopes with best fit approach are included for developing future spots. The Char Dham areas are facing significant challenges associated to climate change as a result of rapidly retreating glaciers, rising temperatures and extreme weather events as cloudbursts that endanger landscapes, human settlements, water resources and biodiversity. Weather radars and other weather forecasting mechanism need to be made available on priority in order to accurately predict extreme weather events in these high-altitude regions, especially in view of the devastating experiences of the tragedies in Kedarnath (16–17 June 2013), Reni village (7 February, 2021), Dharali (5 August 2025), Tharali (23 August 2025), Sahastradhara and Tapkeshwar Mahadev in Dehradun (15 September, 2025) and many others caused by cloudbursts and flash floods. So the results of the study collectively highlight the need for climate driven disaster adaptive tourism action plans for increasing sustainability of these areas.

Sustainable tourism and action plan for the decentralization of tourism

The Department of Economic and Social Affairs defines ‘sustainable tourism’ as ‘a form of tourism that addresses the concerns of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities while considering its present and future economic, social, and environmental impacts’. Tourism addresses multiple sections of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. For instance, SDG 8.9 pertains to the formulation and execution of policies that encourage sustainable tourism, which not only creates employment opportunities but also supports local culture and its products. Similarly, SDG targets 12.b. and 14.7 are focused on creating jobs through sustainable tourism that will give economic benefits to the people. In view of the above objectives, customized actions are required to be implemented in the Char Dham area including development of mountaineering villages for planning of home stays, infrastructural services like adequate car/vehicle parks, and amenities prior to develop a spot or its satellite spot, promotion of adventure tourism destinations, development of community-based responsible tourism and launching sustainable travel mobile App for secure travel. Specific implementation plan for the mentioned strategies is provided in Table 5 and Fig. 7. Further, minimizing the adverse impact of concentrated and localized tourism, decentralization of tiny spots surrounding major spots may be alternate options for planners3. Keeping this in view, potential tourist spots were also identified with classified zones for future development of satellite tourist spots in and around the Char Dham area. Implementing such plan as well as establishment of ecofriendly tourism initiatives will be beneficial for managing the overwhelming tourist rush in the areas by decentralizing them in the suggested satellite spots. This approach will not only reduce continuous pollution loads at a spot or shrine but will also minimize seasonality of tourism in view of changing available tourist resources in different seasons in these locations. Here, available infrastructure, and income of the local communities will suit to all-weather tourism with all-weather roads being under construction to reduce travel time, increase transportation efficiency, less emissions, smooth transit of goods and services, uninterrupted movement of visitors and minimizing congestions. However, regulatory measures like maintenance of carrying capacity, proper management of solid waste46,47, bringing ambient air pollution emissions under prescribed norms through introducing electric rickshaws, car, vehicles, ropeways, etc. also need to be introduced in the Char Dham as well as proposed alternative tourist places surrounding to them. The Hon’ble Prime Minister of India, Mr. Narendra Modi, suggested the idea of “Gham Tapo” (basking in the sunshine) tourism, which Uttarakhand Tourism is also pursuing. The term “Gham” in the local Garhwali language means “sunlight,” while “Tapo” means “basking”. In the Himalayan region, where the sky is clear, local communities typically warm up under bright sunlight during the winter months. On the other hand, smog and other transported aerosol emissions from both inside and outside the region throughout the winter keep the Indo-Gangetic Plain and other adjoining Punjab Plain regions obscure. This noble idea of “basking in the sunshine” may therefore be beneficial from the perspective of tourist health recovery in the form of body warming and ‘vitamin D’, as well as reducing seasonality during the winter months when there are not enough recreational resources available except winter sports like “snow” or “skiing.”

Sites recommended for establishment of ecotourism circuits and sustainable tourism development plan in and around the Char Dham area (generated using ArcGIS software (ESRI, CA, USA), https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/trial).

SDGs and policy directions towards promotion of green tourism

While working towards achieving the SDGs, appropriate policy and planning processes are crucial for local, regional, and national levels. Destinations are likely to be benefitted from the positive effects of tourism components49. At present, the state has launched “Uttarakhand Tourism Policy 2030”, which proposes to develop tourism industry in the state by including 5 sectors, such as, nature and adventure tourism, health and wellness tourism, religious and cultural tourism, heritage tourism and meetings, Incentives, Convention and Exhibitions (MICE) tourism. Further, several other schemes and projects that are presently operational in the areas include, ‘Swadesh Darshan (SD)’ and ‘Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual, Heritage Augmentation Drive (PRASHAD)’ and ‘Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment (SASCI) 2024-25’. The SD and PRASHAD mainly focuses on sustainable and theme specific development of tourism that aligns with the geoscientific, bioscientific, socioeconomic, and cultural-historical indicators of the present study. Whereas, the SASCI is focused on infrastructure development and iconic tourist centres. The current study adequately describes the development of nature-based tourism while addressing the challenges of over tourism and carrying capacity within limit, which are important aspects of sustainable tourism. Here, a concept is important that carrying capacity approach is required for tourist influx as well as with vehicular influx in the areas and equines used for the trek routes. As unlimited vehicles cause air pollution and unhealthy equines are used in trek routes and even their dead bodies are associated with soil and water pollution. Also, policies focused on entry of vehicles only with Bharat Stage VI (BS VI) and/or electric vehicles, empowering nomadic tribes through ecotourism (Radampa and Bhotia in Mana village, Badrinath; Jaad-Bhotiyas in Gangotri) are suggested for the area. Further, infrastructure facilities reading proper monitoring of air, water and soil quality of these pristine areas are urgently needed. Investments are also required for a development of infrastructure in remote mountain regions, particularly in the digitalization of tourism services tapping the local food network and promote sustainable tourism. In addition, a comprehensive tourism marketing strategy is essential. This strategy focuses on creating and expanding markets for tourism while simultaneously developing the necessary infrastructure to support the growth of the industry. It also emphasizes the importance of collaboration between the public and private sectors to leverage resources and expertise. Also, effective promotion of the destination is a key component to attract tourists and maximize revenue generation. By implementing a well-rounded tourism marketing strategy, the aim is to create sustainable economic benefits for the destination and its local communities (Table 6). The small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of travel and tourist industry have the ability to positively influence the environment, economy, and society. In emerging nations, SMEs are crucial for advancing socioeconomic well-being. Micro-entrepreneurship in the tourism sector has been demonstrated to assist socioeconomic growth and conservation goals in the destinations that prioritize nature-based tourism. Given the important role of travel, particularly small-scale travel, plays in the expansion of SMEs, entrepreneurship can help to promote the long-term growth of the tourist industry. A number of SDGs, including SDG 1 on reducing poverty, SDG 4 on improving education, SDG 8 on promoting economic growth and decent work, SDG 12 on responsible production and consumption, and SDG 13 on combating climate change, ought to be undertaken by the commercial sector50. Nonetheless, tourism is a key factor in all 17 goals (Fig. 8).

Database and methodology

This study employed a multidisciplinary approach to assess the Char Dham pilgrim circuits in Uttarakhand, India, integrating geoscientific, bioscientific, socioeconomic, and cultural-historical analyses for the assessment of site suitability. A spatial assessment of tourism resources used 10 main indices encompassing 21 sub-indices, with a distribution emphasizing geological and ecological factors due to their relevance to the pilgrimage routes. The methodology incorporated field surveys, GIS mapping, cartographic analysis, archival research, and literature review. Field evaluations, conducted between 2019 and 2023 at regional and local scales, are focused on selected geosites. This comprehensive approach enabled a systematic evaluation of tourism potential of the region, considering both current conditions and future prospects for sustainable development.

Analysis of thematic layer

The selection of elements or thematic layers constitutes the initial phase of the present investigation51,52,53. Thematic layers mainly taken under consideration were slope, elevation, vegetation, proximity to drainage, retreat of snow cover, climate, biodiversity (including national park or wildlife sanctuary), natural geosites over surface, sub-surface (caves, hot springs), unique natural sites (alipne pastures, lakes, hill villages), cultural places (temples), socio-economic index (rural and urban MPCE, BPL families %, monthly income of highest earning members), and tourist facility (tourist carrying capacity and proximity to road) have been taken into consideration (Fig. 9) for the identification of potential ecotourism sites. Influence of these mentioned layers with the tourism sector is described in Table 7.

Generation of data base

Geospatial characteristics analysis

While planning ecotourism locations, elevation was considered to be a key factor. The sites around the Char Dham were categorized into three elevation classes: low (< 2400 m), moderate (2400–4200 m), and high (> 4200 m). Further, slope of the land surface also influences the construction of potential ecotourism sites. The slope layer was classified into three classes: low (0–16°), moderate (16–33°), and high (> 33°).

Vegetation: This is an essential component for the development of ecotourism sites. Vegetation layer was derived from global map of land use land cover (LULC) dataset which is acquired from ESA Sentinal − 2 imagery at 10 m resolution54.

Proximity to road: Proximity is a spatial analysis tool being used to determine specified distance in view of other factors like road, drainage, settlement, etc55.

Destinations with well-developed transportation systems and convenient access are generally more appealing to tourists56,57. In order to identify suitable ecotourism sites in the Char Dham, ArcGIS software was used to establish three buffer zones from the existing road network spanning distances of 1000 m, 1000–3000 m, and 3000–5000 m.

Proximity to drainage: In view of determining the distance between drainage networks and ecotourism sites, reclassification process was used. Areas with reasonable distance from drainage were given a higher preference to be considered as a potential ecotourism site. Hence, sites within 100–800 m distance58 are suitable, while 800–1600 m are moderately suitable and 1600–3200 m are less suitable.

Proximity to trek: Trekking is such an activity through which one analyses nature at close whether it is pristine or polluted. Char Dham also let tourists to explore its nature through pristine treks and trails59. Based on proximity buffer analysis, trek routes were classified into three buffer zones; 100–600 m, 600–1200 m and 1200–2400 m.

Snow cover change analysis

Snow cover retreat rate of the glacier areas of each Dham was analysed using MODIS aqua (MODIS/006/MYD10A1) and terra (MODIS/006/MOD10A1) daily snow cover datasets (500 m) in the google earth engine’s integrated development environment (IDE), code editor platform60.

The normalized difference snow index (NDSI) algorithm, effective for binary (i.e., delineating between “snow” and “no snow”) monitoring of snow cover, used both datasets. NDSI is defined as the difference in reflectance between wavelengths of visible (green) and shortwave infrared (SWIR) light:

The surface reflectance in the green and SWIR bands, denoted as rgreen and rSWIR, respectively. The range of the index varies − 1 to + 1. Pure snow pixels have a non-destructive strength index (NDSI) that is significantly higher than pixel compositions which contain combined elements (e.g., snow, water, vegetation, bare ground, etc.).

Climate analysis

Since meteorological observation for the study regions started recently, so in view of assessing long-term climate variability, we have used Climate Research Unit (CRU) climate data (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.05/ge/). These have been in well agreement between observed climate data in the mountain terrains. Monthly temperature and precipitation data for the period 1990–2020 were used for the study in all the study sites. Linear regression analysis showed significant growing or decreasing trends in the time series. The significant trend was assessed using coefficient of determination (R2) and p-value < 0.05. In view of discovering seasonal changes in climatic data, the research was carried out for each season: winter (December-February), pre-monsoon (March-May), monsoon (June-September), and post-monsoon (October-November).

Biodiversity & geodiversity analysis

Thereafter, Natural & cultural heritages (peaks, glaciers, etc.), sub-surface (caves, hot springs, etc.) unique sites (alipne pastures, lakes, hill villages, etc.) and location of temples are digitized using high-resolution satellite imageries like Airbus and Maxar technologies through the Google Earth Pro platform and field surveys.

National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary acquired from BHUVAN NRSC site and later their per cent area was computed in ArcGIS.

Socio-economic conditions: District level analysis was carried out using secondary data under review. Parameters like rural MPCE of the district, urban MPCE of the district, % of BPL families in the district, monthly income of the highest earning members in the district (rural households %) were considered for analysis.

Tourist facilities assessment

The areas were analysed by two sub-categories, namely, tourist carrying capacity of the main areas, and road density. Physical Carrying Capacity (PCC), which refers to the utmost number of tourists who could be physically accommodated in or onto a designated area during a specific period of time, was computed in view of the tourist carrying capacity analysis61. Estimations for the PCC were as follows:

Where, PCC denotes physical carrying capacity; A = Area available for tourist use. Between 15% and 20% of the total geographical area is considered for the present tourist activity in accordance with Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation Implementation (URDPFI) guidelines62 along with expert opinion given that the economy and employment of the region are exclusively rely on tourism. The census data pertaining to Badrinath and Kedarnath regions was taken into account for subsequent analysis. The region encompassing Gangotri and Yamunotri shrines is computed using LISS-IV data from 2017.

Au = required area per tourist, or 3 m; Rf = Daily operating time divided by average visit duration.

Also, the Real Carrying Capacity (RCC), which refers to the highest allowable number of visitors to a particular site, can be ascertained once it becomes feasible to calculate the Correction Factors (CF) based on prevailing unique attributes of a site. Consequently, CF is implemented in the PCC as shown below.

RCC represents actual carrying capacity; PCC denotes physical carrying capacity; and Cf signifies correction factors. The formula for determining correction factors is as follows.

The variables Cfx, Lmx, and Tmx represent the correction factors, limiting magnitude, and total magnitude of variable x, respectively.

Driving the normalized weight using AHP

Analytical hierarchy process (AHP) weighting of the subcategories was performed in the subsequent phases. AHP, an approach to multiple criteria decision analysis (MCDA) used in a variety of scientific fields, is a widely recognized methodology. The AHP framework provides a systematic approach to quantifying the pairwise comparison of various decision elements and criteria. In order to rank the value of a criterion map for a pairwise matrix using Saaty’s scale63,64, the opinions of experts were taken into account.

Further, consistency ratio (CR) and normalized weight of different thematic layers were also calculated (Table 8). CR predicts (acceptable value should be < 0.1), the inconsistency of judgments mathematically and calculated by the following equations.

Where, CI = Consistency ratio, RI = Random Index.

Where ⋋ = The largest Eigen value of the matrix, n = represents the number of sub-categories.

Site suitability assessment

Further, site suitability assessment score “Si” in the final stage was evaluated for each Dham based on the linear combination of each used factor’s suitability score as shown in the following equation.

Where ‘n’ indicates number of sub-categories, ‘Wi’ shows multiplication of all associated weights in the hierarchy of “ith” sub-category and ‘Ri’ is a rating given for the defined class of the “ith” sub-category found from the direct assessment. When weighted linear combination is used for Multi Criteria Evaluation (MCE), the sum of assigned weights should be 1 for a defined each category/subcategory. Each factor sub-category layer was classified into 3 suitability classes (i.e., S1, S2, and S3) and their suitability scores were presented in the standardized format ranging from marginally suitable to high suitable. Finally, the total suitability score from each factor was assembled to create site suitability map for ecotourism. The land suitability map for ecotourism created based on the linear combination of suitability score of every index. The GIS-based model for multi-criteria land suitability evaluation for ecotourism is shown in Fig. 2.

However, there have been some of the limitations of the work which mainly include the estimation of carrying capacity which is based on physical parameters and may inadequately accounts for spiritual significance and real experience of the visitors. Though perceptive, the estimates of carrying capacity in the Char Dham area have significant limits that need to be noted. Here, strict geographical limits and LULC analysis only to the temple associated areas form the basis of most estimation. These do not fully consider dynamic elements as seasonal fluctuations, infrastructure adaptation, or socio-cultural impacts. For example, development in tourism infrastructure, better waste management systems, and better crowd control policies might raise the real carrying capacity in use. In addition, behaviour of the visitors and ability of the local ecosystems to withstand human activities are not specifically considered, which could lead to an underestimation of the actual capacity. Moreover, the calculations neglect psychological or economic carrying capabilities reflecting visitors’ contentment or profitability of tourism operations. Seasonal influxes during times of maximum pilgrimage also provide difficulties in matching theoretical capacities with real world situations. The study ignores adaptive tactics that could improve accessibility and usability in less favourable terrain, even while it sets fixed standards for elevation and slope suitability. Therefore, even if the results offer a basic framework for sustainable tourist planning, dynamic assessments and adaptive management techniques should be added to properly address these restrictions. Further, the suggested sustainable tourism strategies in spite of being comprehensive may face implementation challenges due to limited resources and institutional capacities in these remote areas. For future endeavours, extensive engagement of the stakeholders and local participatory approaches are suggested for addressing the present limitations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Publicly available datasets used in this study include: MODIS snow cover data (MODIS/006/MYD10A1 and MODIS/006/MOD10A1) accessed through Google Earth Engine, Climate Research Unit (CRU) climate data available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg Land use land cover data from ESA Sentinel-2 imagery, Drainage layer was downloaded from open street map data files from http://gis.geojamal.com. National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary boundaries from BHUVAN NRSC.

References

Boluk, K. A. & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. Sustainable tourism and the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 30, 1–19 (2022).

Font, X., English, R., Gkritzali, A. & Tian, W. S. A meta-analysis of the contribution of tourism and hospitality to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 256–276 (2023).

Fennell, D. A. Routledge,. Ecotourism (5th ed.) 1-382 (2020). (2020).

Richins, H. & Hull, J. S. (eds) Mountain Tourism: Experiences, communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures (CABI, 2022).

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour Geogr. 22, 610–623 (2020).

Peeters, P. et al. And Postma, A. Research for TRAN Committee Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy responses, European Parliament1–260 (Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, 2022).

Kang, S., Lee, G., Kim, J., & Park, D. Identifying the spatial structure of the tourist attraction system in South Korea using GIS and network analysis: An application of anchor-point theory. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 9, 358–370 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.04.001

Kim, J., Thapa, B., Jang, S. & Yang, E. Seasonal Spatial activity patterns of visitors with a mobile exercise application at Seoraksan National park. South. Korea. 10 (7), 2263 (2018).

Kim, J., Lee, C. K. & Mjelde, J. W. Impact of economic policy on international tourism demand: The case of Abenomics 7 (2020).

Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour Geogr. 22, 467–475 (2020).

Duxbury, N. & Bakas, F. E. Vinagre e Castro, T. Creative tourism development models towards sustainable and regenerative tourism. Sustainability 13, 2 (2021).

Butler, R. W. Tourism carrying capacity research: A perspective Article. Tour Rev. 75, 207–211 (2020).

Gossling, S., Scott, D. & Hall, C. M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 1–20 (2021).

Hon’ble National Green Tribunal (NGT). Report on carrying capacity of eco-sensitive zones in Indian Himalayan Region. Government of India, (2022).

Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. Sustainable Tourism. (2022). https://tourism.gov.in/sustainable-tourism

Paudyal, S., Adhikari, S. & Poudel, K. P. Geospatial modeling for sustainable mountain tourism development: A case study of Annapurna region. Nepal. J. Outdoor Recreat Tour. 39, 100507 (2022).

Bisht, M. P. S., Mehta, M. & Nautiyal, S. K. Geomorphic hazards around Badrinath (Uttaranchal) and control measures. Himalayan Geol. 27 (1), 73–80 (2005).

Khan, A. A., Sinha, K. K. & Chaterjee, A. C. Geology of Alaknanda, Bhagirathi, and Yamuna valleys, Garhwal Himalaya, parts of Chamoli, Tehri, Uttarkashi & Pauri districts, Uttarakhand State, India. Int. J. Adv. Res. 12 (07), 1079–1105 (2024).

Misra, R. C. & Sharma, R. P. Geology of Nandprayag Klippe and Central Crystalline, Kumaon Himalayas. Bulletin, Indian Geological Association, 6(2), 85–96. (1973).

Das, S., Kar, N. S. & Bandyopadhyay, S. Glacial lake outburst flood at Kedarnath, Indian himalaya: A study using digital elevation models and satellite images. Nat. Hazards. 77, 769–786 (2015).

Valdiya, K. S. The Making of India: Geodynamic Evolution816 (Macmillan, 2010).

Seeber, L. & Gornitz, V. River profiles along the Himalayan Arc as indicators of active tectonics. Tectonophysics 92, 335–367 (1983).

Sati, S. P. & Gahalaut, V. K. The Fury of the floods in the North-West Himalayan region: the Kedarnath tragedy. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 4 (3), 193–201 (2013).

Sati, V. P. Carrying capacity analysis and destination development: A case study of Gangotri tourists/pilgrims’ circuit in the himalaya. Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res. 23 (3), 312–322 (2018).

Poudel, S. & Nyaupane, G. P. Biodiversity conservation through community-based mountain tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 42, 100957 (2022).

Trivedi, S., Gopal, K. & Singh, J. Hydrogeochemical attributes of the meltwater emerging from Gangotri glacier. Uttaranchal J. Geol. Soc. India. 76, 105–110 (2010).

Sharma, M. et al. The state of the Yamuna river: A detailed review of water quality assessment across the entire course in India. Appl. Water Sci. 14, 175 (2024).

Prabha Mohan, S., Williams, I. S. & Singh, S. Direct Zircon U–Pb evidence for pre-Himalayan HT metamorphism in the higher Himalayan Crystallines, Eastern Garhwal Himalaya, India. Geol. J. 57 (1), 133–149 (2021).

Gupta, V., Jamir, I., Kumar, V. & Devi, M. Geomechanical characterisation of slopes for assessing rockfall hazards in the upper Yamuna Valley, Northwest higher Himalaya, India. Himalayan Geol. 38 (2), 156–170 (2017).

Valdiya, K. S., Paul, S. K., Chandra, T., Bhakuni, S. S. & Upadhyay, R. C. Tectonic and lithological characterization of Himadri (Great himalaya) between Kali and Yamuna rivers, central himalaya. Himalayan Geol. 20 (2), 1–17 (1999).

Ministry of Environment and Forests. National Environment Policy. Government of India (2006).

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs Government of India. River Centric Urban Planning Guidelines. (2021).

Ahmadi, M., Faraji Darabkhani, M. & Ghanavati, E. A GIS-based Multi-criteria Decision-making approach to identify site attraction for ecotourism development in Ilam Province, Iran. Tour Plan. Dev. 12, 176–189 (2015).

Salim, E., Ravanel, L., Deline, P. & Gauchon, C. A review of melting ice adaptation strategies in the glacier tourism context. J. Outdoor Recreat Tour. 33, 100341 (2021).

Bhatta, K., Ohe, Y. & Ciani, A. Geospatial analysis of tourism potential in the Nepal himalaya. Tour Manag Perspect. 45, 101060 (2023).

Velentza, K. Maritime archaeological Research, Sustainability, and climate resilience. Eur. J. Archaeol. 26(3), 1–19 (2022).

Steiger, R., Posch, E., Tappeiner, G. & Walde, J. The impact of climate change on winter tourism demand, supply, and economic effects: A regional analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 667–686 (2023).

Welling, J., Espiner, S., Walker, J. & Baxter, W. Climate change risk perceptions and adaptation responses of glacier tourism stakeholders in new Zealand. J. Outdoor Recreat Tour. 38, 100487 (2022).

Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management CategoriesIUCN, (2008).

Brilha, J., Pereira, D. & Pereira, P. Geodiversity and biodiversity: two sides of the same coin in nature-based tourism. J. Ecotourism. 22, 115–130 (2023).

Poudel, S. & Nyaupane, G. P. Biodiversity conservation through community-based mountain tourism: A systematic literature review. Tour Manag Perspect. 42, 100957 (2022).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable tourism. (2022). https://sdgs.un.org/topics/sustainable-tourism

Uttarakhand Tourism Department. Uttarakhand tourism development master plan 2007–2022. (2022). https://uttarakhandtourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/document/type/volume-1-executive-summary.pdf

Uttarakhand State Pollution Control Board. District environmental plan Uttarkashi. (2021). https://ueppcb.uk.gov.in/files/2._Draft_Uttarkashi_23rd_november.pdf

Uttarakhand Tourism Department. Tourism policy (2023). https://uttarakhandtourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-06/Tourism-policy-2023.pdf (2023).

Kuniyal, J. C., Jain, A. P. & Shannigrahi, A. S. Solid waste management in Indian Himalayan tourists’ treks: A case study in and around the Valley of flowers and Hemkund Sahib. Waste Manag. 23, 807–816 (2003).

Kuniyal, J. C., Jain, A. P. & Shannigrahi, A. S. Public involvement in solid waste management in Himalayan trails in and around the Valley of Flowers, India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 24, 299–322 (1998).

Biddulph, R. & Scheyvens, R. Introducing inclusive tourism. Tour Geogr. 20, 583–588 (2018).

Rylance, A. S. Ecotourism and the Sustainable Development goals. In Routledge Handbook of Ecotourism (Routledge, 2021).

Kc, B., Dhungana, A. & Dangi, T. B. Tourism and the sustainable development goals: stakeholders’ perspectives from Nepal. Tour Manag Perspect. 38, 100822 (2021).

Kalogirou, S. & Expert systems An application of land suitability evaluation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 26, 89–112 (2002).

Malczewski, J. GIS based landuse suitability analysis: A critical overview. Prog Plan. 28, 4449–4466 (2004).

Karra, K. et al. Global land use / land cover with Sentinel 2 and deep learning in 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing IGARSS 4704–4707IEEE, (2021).

Ahmadi, M., Faraji Darabkhani, M. & Ghanavati, E. A GIS-based multi-criteria decision-making approach to identify site attraction for ecotourism development in Ilam Province, Iran. Tourism Plann. Dev. 12 (2), 176–189 (2015).

Paudyal, S., Adhikari, S. & Poudel, K. P. Geospatial modeling for sustainable mountain tourism development: A case study of Annapurna region, Nepal. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism. 39, 100507 (2022).

Fennell, D. A. Ecotourism (5th ed.). Routledge (2020).

Wu, W., Peng, C., Zhu, B., Wang, J. & Li, W. Suitability evaluation for ecotourism in the Qinling mountains of Shaanxi Province. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 24 (6), 2685–2693 (2015).

Salim, E., Ravanel, L., Deline, P. & Gauchon, C. A review of melting ice adaptation strategies in the glacier tourism context. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism. 33, 100341 (2021).

Steiger, R., Posch, E., Tappeiner, G. & Walde, J. The impact of climate change on winter tourism demand, supply, and economic effects: A regional analysis. J. Sustainable Tourism. 31 (4), 667–686 (2023).

Hall, D. K. & Riggs, G. A. MODIS/Terra Snow Cover Daily L3 Global 500m SIN Grid, Version 6 (NASA National Snow and Ice (Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center, 2016).

Kuniyal, J. C. et al. Dayara Bugyal restoration model in the alpine and subalpine region of the central himalaya: a step toward minimizing the impacts. Sci. Rep. 11, 16547 (2021).

Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Urban and Regional development plan formation and implementation (URDPFI) Guidelines IIA-IIB, Appendices to URDPFI guidelines. (2015). http://mohua.gov.in

Saaty, T. L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: planning, Priority setting, Resource Allocation (McGraw-Hill, 1980).

Bunruamkaew, K. & Murayama, Y. Site suitability evaluation for ecotourism using GIS & AHP: A case study of Surat thani Province, Thailand. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 21, 269–278 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author (J.C.K.) expresses gratitude to the Hon’ble Vice Chancellor, Veer Chandra Singh Garhwali Uttarakhand University of Horticulture and Forestry (VCSG UUHF), Bharsar-246123, Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, India and Dean, College of Forestry, VCSG UUHF, Ranichauri-249199, Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakahnd, India for providing the facilities necessary for the author to successfully complete the work. The authors express their gratitude to the Director, G.B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment (NIHE), Kosi-Katarmal- 263 643, Almora, Uttarakhand for providing facilities in the Institute. The authors also express their gratitude to the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) in National Capital Region and Adjoining Areas, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India for providing necessary facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.K. formulated the manuscript, critically reviewed it and finalised the entire manuscript; J.C.K. and P.M. conceptualized and designed the study. J.C.K., P.M., N.K., R.D., and M.N. conducted field surveys and data collection. P.M. and N.K. performed geospatial analysis and data visualization. J.C.K., P.M., and R.D. analyzed and interpreted the results. J.C.K. and P.M. wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuniyal, J.C., Maiti, P., Kanwar, N. et al. Carrying capacity and strategic planning for sustainable tourism practices in the Char Dham from the Western Himalaya, India. Sci Rep 15, 36340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20166-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20166-8