Abstract

With increasing adoption of residue retention over soil surface, there is an urgent need to investigate the effect of residue on soil water moderation and soil temperature distribution during crop growth period. Therefore, an investigation was carried out on wheat crop, grown under long term experiment integrating a dual strategy of field experiment and crop simulation modelling. The major aim of the present study was to simulate the conservation agriculture effects on soil water profile and soil thermal regime in wheat crop under maize based cropping system using APSIM—Agriculture Production System Simulator) model. The experiment followed a split plot design with three replications, evaluating two tillage practices: zero tillage with residue retention (ZT + R) and conventional tillage with residue incorporation (CT + R). . The APSIM model was calibrated using measured data from the 2018–19 cropping season and validated with independent datasets from 2019–20. Model performance was rigorously evaluated using statistical metrics such as the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), normalized RMSE (nRMSE), Willmott’s index of agreement (D-index), and mean bias error (MBE). The results indicated that the model accurately simulated crop phenology, leaf area index, aboveground biomass, and grain yield under both tillage treatments. Results of validation of APSIM model showed good agreement for simulated soil temperature (RMSE = 1.12–1.87 °C, nRMSE = 0.08–0.12 and R2 = 0.67–0.71) and soil water (RMSE = 0.017–0.031 cm3cm-3, nRMSE = 0.07–0.13 and R2 = 0.66—0.80) in both CT + R and ZT + R treatments. Simulated soil water content (SWC) was lower in the CT + R treatment compared to ZT + R. The model simulated transpiration and drainage were higher under ZT + R, whereas evaporation was greater in CT + R, reflecting the influence of residue management and tillage on soil moisture dynamics. APSIM showed that the soil temperature was more in CT + R than ZT + R for 0–60 cm soil depth. Additionally, diurnal fluctuations in soil temperature were more pronounced in the surface layer (0–15 cm) than in the deeper layer (45–60 cm) under both treatments. The analysis demonstrated the capabilities of APSIM to capture the effect of tillage practices and cropping system on soil water profile, temperature changes and crop growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intensive tillage practices have led to reduction in SOC and degradation of soil physical properties. Therefore, conservation agriculture (CA) is an emerging resource saving technology. It is the most feasible option for crop production along with sustainable maintenance of the environmental quality1. It aims to enhance soil moisture conservation and regulate soil temperature by maintaining crop residues on the soil surface2. Resource-saving technologies such as no tillage, reduced or minimum tillage, subsoil tillage, and subsoil tillage with residue incorporation have been widely adopted across the globe to improve soil health, enhance water use efficiency, and promote sustainable agricultural practices3,4. Conservation agriculture (CA) might alleviate the influence of dry periods5, increase crop yields4, as well as upgrade soil biological and physico-chemical properties6. Therefore, in recent years, researchers have increased their focus to devise the most efficient conservation practice to produce higher crop yield7.

Soil water and soil temperature are critical variables in land surface processes that influence the exchange of moisture and energy between the soil and plant atmosphere8,9. They also regulate key biological and physico-chemical processes such as evaporation, soil aeration, and microbial activity. Due to the huge spatiotemporal changes in soil moisture and temperature (mainly by heterogeneous soil properties), these data are rarely recorded in the field experiments. However, this hydro-thermal information is indispensable in simulating the hydrological processes. Simultaneous measurement of soil water and temperature under field condition by direct method is time consuming and expensive. Simulation models can serve as powerful tools for understanding the dynamics of soil hydrothermal properties within the crop root zone, which can assist in judicious scheduling of irrigation in different crops under diverse soil types.

The Agricultural Production Systems Simulator (APSIM) is a dynamic, daily time-step simulation model that combines management and biophysical modules into a central processor to simulate crop, development, growth and yield, and also their interactions with soil processes such as water balance, nutrient cycling (particularly nitrogen and carbon), soil temperature dynamics, and residue decomposition10.The APSIM model can simulate the dynamics of temperature, soil water, C, N, and P during different management conditions. The APSIM model has been extensively calibrated and validated for wheat production across diverse agroecological zones worldwide, including Australia11,12, Europe13, Africa14, North America15, Tunisia16, Central Morocco17, Northern Europe18 and China19. These studies consistently demonstrate APSIM’s robustness in accurately simulating wheat phenology, biomass accumulation, grain yield, and the dynamics of water and nitrogen under varying climatic conditions and management practices. Despite its widespread global application, the use of the model in India’s primary wheat-growing region—the Indo-Gangetic Plains, has been relatively limited. In India, a study by Mohanty et al.20 demonstrated that the APSIM model effectively simulated crop growth and soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics over a 43-year long-term experiment in Vertisol soils of central India. Similarly, Bana et al.21 demonstrated that the APSIM model effectively simulates crop performance, phenological development, and the impacts of conservation agriculture (CA) practices within the rice–wheat cropping system (RWCS), highlighting its robustness in capturing CA-induced effects. However, most of these efforts have focused primarily on yield prediction and less on the simulation of soil moisture and temperature regimes under conservation agriculture. The potential of APSIM to simulate the integrated soil hydrothermal behavior in CA systems remains largely unexplored, particularly under long-term experimental setups. Therefore, the present study was conducted to (i) calibrate and validate the APSIM model to simulate the growth of wheat crop under maize based cropping system (ii) evaluate the effects of CA practice on soil water and soil temperature profiles.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

This study was conducted under a long-term CA experiment initiated during the Kharif season of 2008 at ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR-IARI), New Delhi, located at 28°35′ N latitude and 77°12′ E longitude. The experimental site is located in a semi-arid climatic region, characterized by hot, dry summers and cold winters with irregular rainfall distribution. May and June are the hottest months, with mean maximum temperatures ranging from 40 °C to 46 °C, while January is the coldest month, with mean minimum temperatures between 6 °C and 8 °C. The area receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 650 mm, with about 80% occurring during the southwest monsoon season from July to September.

Different soil properties used for simulation in APSIM wheat crop model are presented in Table 1. The soil texture at the experimental site is sandy loam for surface layer (0–15 cm) with sand content more than 64%. Bulk density increases with depth under both treatments, indicating higher compaction in subsurface layers. Notably, zero tillage with residue retention (ZT + R) shows slightly lower bulk density in the topsoil compared to conventional tillage (CT + R), suggesting better soil structure and porosity under ZT + R.

Experimental details

The Maize-wheat-mungbean (MWMb) cropping system was practised in the research plot of size 16.5 × 4.0 m employing two distinct tillage practises, namely zero tillage with crop residue retention (ZT + R) and conventional tillage with residue incorporation (CT + R). In zero tillage, seed was directly sown into untilled soil using a ZT planter with inverted 'T' tynes. In the conventional tillage treatment, ploughing was done using a disc harrow, accompanied by a spring tyne cultivator and rotavator. At harvest, approximately 30% of the preceding maize crop residue was retained on the soil surface in the ZT + R plots, while an equivalent amount was incorporated into the soil in the CT + R plots. The remaining residues were removed from the experimental plots.

In the present study, which was conducted during the 7–8th and 10–11th years of a long-term experiment, observations were made over two consecutive years under two distinct tillage practices: zero tillage with residue retention (ZT + R) and conventional tillage with residue incorporation (CT + R). Seeds were procured from the Pusa seed counter, ICAR-IARI, New Delhi, India. The wheat cultivar HD-2967 was sown on 3rd November and 24th October in the first and second years, respectively, using a seed rate of 100 kg ha⁻1 and a recommended row spacing of 22.5 cm. Harvesting was carried out on 13th April and 6th April, respectively. Five irrigations with a depth of 50–55 mm were given in both the treatments at various phenological stages: crown root initiation, tillering, jointing, flowering, and grain filling stage. A fertilizer dose of 120 kg N, 60 kg P₂O₅, and 40 kg K₂O per ha-1 was applied. The entire quantity of P₂O₅ and K₂O was incorporated at the time of sowing, while nitrogen was applied in a split application, 50% (60 kg N ha⁻1) at sowing, and the remaining 50% was applied in two equal splits at the first and third irrigation events. Weed growth in ZT + R plots was restricted by spraying glyphosate @ 1.0 kg ha-1 before sowing and using Cladinofop @ 60 g ha-1 at 30 days after sowing (DAS). To control weed, manual weeding was done in CT + R plots on 35DAS.

APSIM model description

The Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator (APSIM) is a dynamic cropping systems modelling framework comprising a suite of interconnected modules that simulate biophysical and management processes in farming systems12,22. Its modular design enables flexible integration of components such as crop growth, irrigation, nutrient dynamics, and soil processes through a central simulation engine (Fig. 1). In this study, APSIM was parameterized using detailed management practices, recorded climate datasets, site-specific soil characteristics, and observed crop performance data collected in the field.

Parameterization of the model

Simulation of wheat crop growth was carried out by linking weather (MET), crop (wheat), soilWAT (soil water), and canopy modules with APSIM 7.10 model engine. Certain input parameters that are either difficult to measure directly or associated with a degree of uncertainty, such as crop varietal characteristics which were calibrated within scientifically reasonable bounds to improve model reliability and ensure accurate simulation outcomes. The model was calibrated using field experimental data collected during the year 2018–19 cropping season. Simulated outputs were compared with observed field data, and statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the model’s performance.

Daily weather data, such as minimum net solar radiation (Rad, MJ m-2), minimum (Tmin) and maximum (Tmax) air temperature (°C), and rainfall (mm) were obtained from meteorological observatory, IARI, New Delhi. Daily meteorological data from 1st October 2018 to 31st April 2019 and 1st October 2019 to 31st April 2020 were used to calculate annual amplitude in monthly temperature (AMP) and average ambient temperature (TAV). The “tav amp” files were utilised as input into the MET.

Plant biophysical parameters (phenology, grain yield, above-ground biomass, LAI, and root biomass) and soil parameters from the first year of observation (2018–19) were used for model calibration. The simulation incorporated initial site conditions, local soil and weather data, and management practices to accurately represent the experimental setup. Leaf Area Index (LAI) of the crops was measured weekly using a plant canopy analyzer (LAI-2200, LICOR Inc., Nebraska, USA). On each sampling date, a minimum of five measurements were recorded from different locations within each plot, and their mean value was used to represent the LAI for that plot. Above-ground biomass was estimated at regular intervals based on weekly measurements. In wheat plots, plant population density was determined by counting the number of plants within a 30 cm linear section. Biomass sampling was conducted at the same locations used for visual observations. Roots were washed with water after uprooting the plants from the field to remove attached soil. Plants were separated into different components—leaf, stem, root, and panicle—and oven-dried at 65 °C for at least 48 h or until a constant dry weight was achieved. Initial conditions of experimental site, local soil and weather parameters and management conditions were used for simulating the model. A total of 7 observed aboveground biomass and 13 LAI data points were used for model calibration to ensure accurate simulation of crop growth dynamics.

Parameterization of crop cultivars

The APSIM crop simulation model utilized specific crop and cultivar parameters, including thermal time requirements for various phenological stages, effective tillers per plant, biomass partitioning coefficients, root and leaf biomass, LAI, final biomass, and grain yield. These cultivar-specific coefficients are essential for accurately simulating crop growth and development. Wheat module requires genetic coefficients that characterise the features of cultivar growth and development. These coefficients were modified to obtain a proper agreement (within 10%) between simulated and observed values for crop phenology, aboveground biomass, LAI, root biomass, and grain yield. Model calibration began with the adjustment of phenological parameters, as accurate simulation of crop developmental stages forms the foundation for reliable predictions of biomass accumulation and grain yield. Calibrated coefficients are given in Table 2.

Parameterization of soil properties in the model

APSIM’s soil module requires measurable soil parameters such as field capacity (FC), soil layer thickness, soil organic carbon (SOC), soil texture, soil moisture content, bulk density (BD), permanent wilting point (PWP), pH, saturated hydraulic conductivity, Electrical Conductivity (EC), soil temperature (ST), ammonical and nitrate nitrogen content of soil. For wheat, the root penetration parameter (XF, 0–1) and root water extraction coefficient (KL) were set to default values from the APSIM crop descriptor files.

For simulation of soil water, APSIM-SOILWAT module requires input parameters such as bulk density, field capacity, permanent wilting point and saturated soil moisture and saturated hydraulic conductivity. In addition to the above parameters, other key soil parameters such as soil albedo (SALB), layer drainage rate coefficient (SWCON), and the evaporation parameters- first stage of soil evaporation (U) and second stage of soil evaporation (CONA), were determined during the calibration process to enhance the accuracy of soil water and energy balance simulations. In addition, some crop specific parameter like crop’s lower limit of water extraction was also obtained. Soil temperature was simulated using the SOILTEMP module, which requires input of boundary layer conductance, ranging from 0 to 100 J s⁻1m⁻2 K⁻1 for accurate representation of heat transfer between the soil surface and the atmosphere. All these soil parameters considered in the present study are given in Table 3. Soil water content at depths of 0–15, 15–30, 30–45 and 45–60 cm was determined using the gravimetric method. Soil samples collected with a screw auger in aluminum cans were weighed, oven-dried at 105 °C for at least 24 h, and reweighed. Soil moisture (%) was calculated as:

SM (%) = 100 × (Mw − Md) / Md,

where Mw is the wet weight and Md is the dry weight of the sample.

Soil temperature (ST) in ZT + R and CT + R plots was recorded at 10 and 20 cm depths using a platinum resistance digital thermometer (PT100), with a resistance range from 100 Ω at 0 °C to 138.4 Ω at 100 °C. Measurements were taken after stabilization of readings. For each soil depth, 13 soil moisture and 8 soil temperature observations were collected at different intervals during 2018–19 and used for model calibration.

Model validation

Following parameterization and calibration, the model was validated to assess its overall performance. This validation step was carried out using an independent dataset of crop and soil parameters collected during the second year of observation (2019–20). A total of 7 observations for aboveground biomass and 10 for LAI were employed for model validation. Similarly, 8 soil moisture and 9 soil temperature observations recorded for each depth during 2019–20 were utilized for model validation. Simulated outputs were compared with observed data for crop phenology and productivity, providing further verification and enhancing the reliability of the model.

Model evaluation

Performances of the APSIM model was evaluated using statistical parameters including coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), normalized RMSE (nRMSE), Willmott’s index of agreement (D-index), and mean bias error (MBE).The mathematical expression of these parameters are as expressed below:

where Oi and Pi are the observed and predicted values, Ō is the mean of observed values, \(\overline{P }\) is the mean of predicted values, n is the number of data points23,24. Model performance for grain yield was evaluated by calculating the difference and absolute deviation between simulated and observed yield values for each treatment25.

Results

Model calibration

Crop phenology

For both ZT + R and CT + R treatments, simulated and observed results showed good agreement for the dates of emergence, flowering and physiological maturity (Table 4). In ZT + R, both simulated and observed emergence, occurred at 9 DAS, simulated flowering occurred 4 days before observed flowering, and simulated physiological maturity occurred 7 days before observed maturity. However, in CT + R, both the simulated emergence and flowering occurred 1 day after observed date of emergence, and flowering, while, simulated physiological maturity occurred 5 days earlier to actual maturity. The model simulated time series of crop phenology is compared with observed data in the Fig. 2.

Aboveground biomass, root biomass and leaf area index

In ZT + R, wheat leaf area index (LAI), biomass and root biomass showed good agreement between observed and simulated values during model calibration (Fig. 3).In general, R2 was found high (0.93 and 0.94) with low nRMSE (0.19 and 0.18) for aboveground biomass and root biomass respectively (Fig. 3a & b). The D index (0.96 and 0.97) and mean biased error (MBE) (-1096 and 2.28) were observed indicating good agreement between observed and simulated values. Likewise, the model accurately simulated LAI with R2 = 0.89, RMSE = 0.87, nRMSE = 0.33, D-index = 0.93, and MBE = 0.56, indicating strong agreement with observed values (Fig. 3c).

Similarly, for CT + R, high correlation was observed between simulated and observed aboveground biomass, root biomass and LAI (Fig. 4). The model showed good agreement with observed values, with LAI (nRMSE = 0.16, D-index = 0.97), aboveground biomass (nRMSE = 0.22, D-index = 0.97), and root biomass (nRMSE = 0.22, D-index = 0.96).

Grain yield

Wheat yield for ZT + R treatment showed good agreement with observed data as indicated by less difference (260 kg ha−1) with an underestimation of 5.61% from observed yield (Table 5). In case of CT + R, the difference was 390 kg ha-1 with an underestimation of 9.35%.

Water content and temperature of soil

A significant agreement was observed between model predicted and field observed soil water content in both ZT + R and CT + R treatments. Under the ZT + R practice, model performance metrics ranged as follows: R2 = 0.69–0.76, RMSE = 0.02–0.031 mm mm⁻1, nRMSE = 0.09–0.15, D-index = 0.68–0.82, and MBE = 0.003–0.025, indicating moderate predictive accuracy with slight overestimation. In contrast, under CT + R, the model showed slightly improved performance with R2 = 0.71–0.75, RMSE = 0.013–0.027 mm mm⁻1, nRMSE = 0.061–0.14, D-index = 0.77–0.92, and MBE = -0.002–0.019, reflecting better agreement with observed value (Table 6).

Simulated soil temperature showed good agreement with observed values under both ZT + R and CT + R treatments at 0–30 cm depth. For ZT + R, model performance metrics were R2 = 0.79–0.83, RMSE = 0.84–0.96 °C, nRMSE = 0.062–0.070, D-index = 0.80–0.90, and MBE = 0.39–0.52 °C, indicating a slight overestimation. In CT + R, values were R2 = 0.76–0.79, RMSE = 0.70–0.88 °C, nRMSE = 0.049–0.065, D-index = 0.89–0.90, and MBE = -0.25 to 0.16 °C, suggesting improved accuracy.

Model validation

Aboveground biomass, root biomass and LAI

The observed and simulated aboveground biomass, root biomass and LAI were compared as time series for both ZT + R and CT + R treatments. In ZT + R, all evaluated parameters showed strong agreement between simulated and observed values during model validation (Fig. 5). Aboveground biomass and root biomass exhibited high R2 (0.95 and 0.96, respectively) and low nRMSE values (0.14 and 0.15), indicating high model accuracy (Fig. 5a & b). The mean bias error (MBE = -13.55) and D index (D = 0.98) further confirmed the reliability of the simulation. Similarly, good agreement was observed for LAI (R2 = 0.94; nRMSE = 0.12) under ZT + R (Fig. 5c).

Under CT + R, the model also showed good predictive performance. Aboveground biomass, root biomass, and LAI demonstrated strong agreement with observed data, with R2 values of 0.96, 0.83, and 0.95, and corresponding nRMSE values of 0.12, 0.079, and 0.15, respectively (Fig. 6a–c), indicating robust model performance.

Grain yield

In both the treatments, grain yield was simulated well by the APSIM wheat model (Table 7). In general, the model underestimated grain yield by 4.78% for CT + R and 9.92% for ZT + R. The predicted grain yield in ZT + R was 5240 kg ha-1, in comparison to 5760 kg ha-1 observed grain yield, while the predicted grain yield in CT + R was 4810 kg ha-1 and that of observed was 5040 kg ha-1.

Soil water dynamics

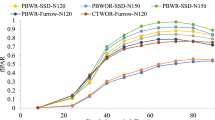

The simulation of soil water content by the model was relatively good for both the treatments. In ZT + R, simulated soil water content (SWC) increased rapidly after irrigation or rainfall and progressively reduced thereafter (Fig. 7). Simulated SWC data also exhibited the recharging of soil profile after irrigation or rainfall. Overall, R2 ranged from 0.66–0.76 with RMSE of 0.017–0.031 mm mm-1 for all soil depths (0–60 cm) in ZT + R treatment (Fig. 8). The nRMSE, D index and MBE ranged from 0.07–0.13, 0.81–0.93 and -0.004 – 0.02, respectively in ZT + R representing the good performance of the APSIM model. For top soil layer (0–15 cm), significant agreement was observed between simulated and observed SWC compared to deeper layers in ZT + R and R2 decreased from 0.76 at 0–15 cm to 0.66 at 45–60 cm soil depth. SWC was slightly over-predicted in the 15–30 cm layer.

In addition, the model showed peaks of increased SWC after rainfall/irrigation events in CT + R treatment (Fig. 9). Simulated SWC was lower in CT + R than ZT + R due to more loss of water through evaporation. For all the soil depths (0–60 cm), R2 ranged from 0.66–0.80, RMSE ranged from 0.02–0.03 mm mm-1 and nRMSE ranged from 0.09–0.12 indicating significant agreement among the simulated and observed SWC (Fig. 10). Meanwhile, the D index for all soil depths, ranged from 0.87–0.91and MBE from -0.007 -0.014. The agreement between simulated and observed SWC was better for top layers, 0–45 cm compared to deeper layer (45–60 cm). There was a slight under-prediction of SWC in the 15–30 cm soil layer.

The simulated water balance components are presented in Fig. 11. Simulated transpiration and drainage were higher in ZT + R over CT + R while evaporation was higher in CT + R. These parameters were used for the computation of soil water balance (Table 8). As we know that plants use less than 1% water for metabolic activity and remaining lost as transpiration so, plant water uptake was considered as transpiration. Results showed that water uptake was higher in ZT + R (15.58 cm) than CT + R (11.42 cm). Drainage was higher in ZT + R (23.31 cm) than CT + R (18.97 cm) plots. However, soil evaporation was just the reverse, higher in CT + R (14.68 cm) than ZT + R (6.37 cm). For ZT + R and CT + R, an inaccuracy of 6.28 and 7.64 cm was detected between input and output, respectively.

Soil temperature

In the ZT + R treatment, simulated soil temperature (ST) during the crop season (1–156 DAS) ranged from 9.41–23.4 °C, 11.03–19.99 °C, 12.8–19.6 °C, and 13.0–18.0 °C at soil depths of 0–15, 15–30, 30–45, and 45–60 cm, respectively (Fig. 12a). In comparison, CT + R exhibited slightly higher STs, ranging from 9.7–24.6 °C, 11.1–22.1 °C, 12.6–19.9 °C, and 13.3–18.4 °C at the same respective depths throughout the crop season (Fig. 12b).

Diurnal fluctuations in soil temperature were more pronounced in the surface layer (0–15 cm) than in the deeper layer (45–60 cm) across both treatments. The temporal trend of simulated ST in CT + R was similar to that in ZT + R. During the early crop growth period (1–27 DAS), ST was higher in the 0–15 cm layer than in the 15–30 cm layer. Between 28–103 DAS, the 0–15 cm layer generally recorded lower ST compared to the 15–30 cm layer. From 104 DAS until maturity, the 0–15 cm layer again showed higher temperatures. In both treatments, the lowest simulated ST was observed on 60 DAS at both depths.

The performance of the model in simulating ST was evaluated at 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm depths using field observed data. The comparison between simulated and observed ST for both ZT + R and CT + R treatments, along with the 1:1 line, is presented in Fig. 13(a–d). For the ZT + R treatment, the R2 ranged from 0.67 to 0.71, with RMSE values between 1.12 and 1.87 °C across both soil depths (0–30 cm). The nRMSE, D-index, and MBE ranged from 0.08–0.12, 0.89–0.91, and − 0.32–0.13, respectively, indicating good agreement between simulated and observed values.

In the CT + R treatment, R2 ranged from 0.69 to 0.70, while RMSE values varied between 1.13 and 1.55 °C. The corresponding nRMSE, D-index, and MBE ranged from 0.08–0.11, 0.88–0.91, and 0.23–0.56, respectively, demonstrating significant agreement between observed and simulated ST. However, the model showed a tendency to slightly overpredict ST in both depths under CT + R. Overall, model performance was generally better at the 15–30 cm depth compared to the 0–15 cm depth in both tillage treatments.

Discussion

The APSIM model simulates the composite interaction between weather, soil and various management practices. Hence, it acts as a decision tool in taking critical decisions with respect to crop management. In the present study, APSIM model version 7.10 was used for calibration with the field measured plant parameters (aboveground biomass, grain yield, root biomass and LAI) and soil properties (soil temperature and soil water content) during the first year of observation and its performance was evaluated for the above parameters during the second year of observation. Even if the APSIM model, cannot completely think through the intricacy of different factors that influence crop production26, the results of the present research show that model is appropriate for predicting the crop growth as well as soil properties like soil moisture and soil temperature of each soil layer in wheat crop.

The accuracy of simulating crop phenological development stages plays a pivotal role in determining the reliability of crop yield predictions. Consequently, phenology simulation is prioritized as a fundamental step in the model calibration process27. The predicted phenological stages closely matched the observed dates under both tillage treatments. In ZT + R, the simulated timing of all developmental stages was comparable to those under CT + R. As with most crop models, APSIM-Wheat estimates phenology based on thermal time, calculated from cumulative degree days using air temperature. However, this approach does not account for the modifying effect of surface mulch on soil temperature in the seed zone, which can influence germination, crop development, and growth rates25. During model calibration and validation, the aboveground biomass, root biomass and LAI indicated good correlation between simulated and observed values in both the treatments considered in this study. Validation of the model showed, high R2, with low values of nRMSE in both the treatments for aboveground biomass and root biomass in wheat crop. Likewise, a good agreement was observed for LAI, during model validation in wheat crop. Similar trends were found in numerous studies21,25,28,29,30. In general, the leaf area development in APSIM model is based on sigmoidal function of thermal time31; however, in this study, the observed LAI followed a power function for wheat crop compared to the sigmoidal function. This might be a reason for the under estimation of LAI of wheat crop. Similar observations were made by Garrido et al.32 and Brown et al.31, where they observed underestimated LAI in wheat crops by APSIM.

In this study, the simulated grain yield exhibited a slight deviation from the observed values during the validation under both ZT + R and CT + R treatments. Similar underestimation of grain yield using APSIM model was observed by Archontoulis et al.33 and Masikati et al.34. The main cause for the deviation from the observed grain yield could be due to the default parameter values in the APSIM simulator which are related with the radiation use efficiency (RUE)35. Similarly, Asseng et al.11 observed an underestimating of grain production under water stress conditions, which was attributed to the insufficient remobilization of stored pre-anthesis carbohydrates into the grain fraction, in the model. Thus, the current study revealed that the APSIM model could simulate the aboveground biomass and grain yield for wheat crop under zero tillage and conventional tillage conditions. Additionally, the APSIM model simulated a positive effect of residue retention on wheat grain yield, and this result was highly consistent with field-observed data, demonstrating the model’s reliability in capturing the beneficial impacts of conservation practices. Similar inferences under comparable situations were made by other researchers36,37,38,39. Higher simulated grain yield under ZT + R was linked to increased simulated transpiration in wheat crop, which is similar to the observations made by Balwinder-Singh et al.40.

Under both the treatments (ZT + R and CT + R) considered in this study, the APSIM-SOILWAT module accurately predicted soil water content. The APSIM simulated SWC which augmented rapidly after irrigation or rainfall, and progressively decreased subsequently. This reduction in SWC after irrigation/rain was mainly due to crop water uptake and evaporation in ZT + R and CT + R, respectively. The simulated SWC was higher under the ZT + R compared to CT + R, primarily due to enhanced soil moisture conservation associated with surface residue retention and less evaporation from soil25,41. In wheat, there was a slight over-prediction of SWC in the 15–30 cm soil depth under ZT + R, while the model is under predicting SWC for same layer in CT + R. This may be attributed to the persistent uncertainty in water retention parameters, primarily arising from the spatial heterogeneity of soil properties33. SWC overestimation or underestimation in the 0–60 cm soil profile may have been induced by inaccuracies related to the greater variability of field data42,43. This is due to modification between the actual and simulated daily evaporation rates in the model. These changes are caused by uncertainty in model inputs like the water flow parameter (SWCON), which governs the movement of water after irrigation or rain. The incorporation of user-defined root water uptake coefficient (root hospitality elements) in the model resulted in good estimates of the simulated root system over time44. Hence, model predicted SWC showed good agreement with the field observed data in deeper layer. Similar trends were identified by Yang et al.30 where they used APSIM to analyse the consequence of conservation agriculture practices on soil water dynamics, water productivity and ET under maize-winter and wheat-soybean rotation system. Another study by Connolly et al.45 also showed that APSIM-SWIM model can successfully be used to assess the effects of infiltration and soil–water relations on crop production. The result is highly consistent with Balwinder-Singh et al.25 evaluated the APSIM model to study the effects of mulch and irrigation management on wheat in Punjab, India, and reported an absolute RMSE of 0.05 cm3 cm⁻3 and a normalized RMSE of 25.2% for the surface layer (0–15 cm). Chaki et al.41 also reported that the SOILWAT2 module accurately simulated soil water dynamics under shallow water table conditions, with RMSE ranging from 0.010–0.015 cm3 cm⁻3 (15–30 cm) and 0.014–0.019 cm3 cm⁻3 (60–75 cm). Similarly, DSSAT model was used to simulate soil water for 0–20 cm soil depth under zero tillage, conventional tillage and reduced conventional tillage conditions and was found to give “moderate” to “good” agreement with observed values (d = 0.81–0.91; nRMSE = 15.3–20.0%) for simulated SWC46.

Soil water balance simulated in this study using APSIM model under both the treatments of wheat crop showed less difference between inputs (R/I, Initial SWC) and outputs (Evaporation, plant water uptake, drainage and final SWC). The difference between simulated water balance input and output parameters was 2.7–7.64 cm. It may be due to the fact that the APSIM-SOILWAT module is just like a tipping bucket type module which uses permanent wilting point as lower limit and field capacity as upper limit. ZT + R had higher root water uptake than CT + R in wheat crop. Similar results were found in drainage (ZT + R > CT + R), while the reverse was observed in soil evaporation, i.e. higher in CT + R than ZT + R. This is due to the fact that residue retention over soil surface leads to lesser evaporation losses, allowing a higher transpiration, better root proliferation and maximum radiation interception. Likewise, Balwinder-Singh et al.25 also observed lower simulated evaporation loss under conservation tillage practices using APSIM model, because this model takes into account the effects of residue retention on decreasing evaporation as well as increasing transpiration. Hence, the benefits of conservation tillage practice could be accurately demonstrated using the APSIM simulator47,48,49 .

Soil temperature of each layer was simulated using APSIM-SoilTemp module, which employs an energy-balance algorithm and the movement of soil heat to deeper layers50. This module uses ambient temperature from the APSIM-Met module, along with input data from the APSIM-SOILWAT module, including soil water content, bulk density, and soil layer depth. The effect of residue retention on the soil surface is evaluated by examining changes in heat flow, as indicated by the difference between actual and potential evaporation rates.

In the present study, the simulated soil temperature for the wheat crop ranged from 9.41- 23.4 ˚C in ZT + R for 0–60 cm soil profile during entire crop season (1–156 DAS) while in CT + R, it ranged from 9.7–24.6˚C. The simulated soil temperature was found to be significantly higher in CT + R than ZT + R. This occurred mostly as a result of increased surface exposure to incoming solar radiation combined with low soil water content in the soil profile51. In ZT + R, residue retention acts as a barrier to the incident radiation resulting in less energy load over the soil surface per unit area. Rai et al.52 reported higher simulated maximum daytime temperature (40–44 °C) and low night-time temperature (20–25 °C) in CT over ZT. They have also observed higher soil temperature wave amplitude at 5 cm than at 20 cm soil depth. In addition, the amplitudes of soil temperatures under both ZT + R and CT + R treatments decreased with increasing soil depth, consistent with the findings of Rai et al.52 and Liu et al.53.The surface soil temperature was 5–6 °C higher under thin polythene than under no polythene, but these differences declined as soil depth increased54,55. Similar observations were also noticed by Zhang et al.56 and Wilson and Jasa57.

Results showed that the simulated soil temperature was high at early season and decreased at 27 DAS. A standing crop canopy created an insulating layer for incident solar radiation resulting reduction in solar energy per unit area of soil which leads to lower soil temperature58. The simulated soil temperature again increased at crop maturity in both the treatments. In general, the soil temperature fluctuation was more in 0–15 cm layer than in 45–60 cm which was attributed to the lower thermal conductivity in upper layers in comparison to the deeper soil layer59. Another reason is the higher SWC of deeper layers as compared to 0–15 cm layer which leads to lesser fluctuations in simulated soil temperature over time.

The comparison of simulated and observed ST along with 1:1 line showed good agreement (in terms of various statistical parameters) in both the treatments. Similarly, Chauhan et al.60 found close proximity between predicted soil temperature and field observed values (R2 ≥ 0.80) from 30 DAS until maturity using the APSIM-SoilTemp module. In maize, Archontoulis et al.35 showed that the simulated soil temperature performed well in the surface soil layer (0–20 cm) with RMSE of 2.8 °C and R2 of 0.86 using APSIM.

Conclusion

We conducted an investigation to understand the long term impacts of residue retention on wheat yield, soil moisture, and soil temperature under a maize-based cropping system, utilizing the APSIM (Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator), which is a process-based crop modeling framework. The model was calibrated using data from the year 2018–19 and was subsequently validated with data from the 2019–20, focusing on two tillage treatments: conventional tillage with residue incorporation (CT + R) and zero tillage with residue retention (ZT + R). The study demonstrated that the APSIM model effectively simulated key crop growth parameters, including phenology, leaf area index, aboveground biomass, and grain yield under both treatments. Model validation showed strong agreement between simulated and observed values for soil water and temperature, with normalized RMSE values ranging from 0.07 to 0.13 and D-index from 0.81 to 0.93. These performance metrics indicate that the model effectively captures soil moisture and thermal dynamics across different tillage practices. Simulation findings indicated that the ZT + R treatment consistently increased wheat performance, yielding more aboveground biomass, better soil water retention, and decreased fluctuations in soil temperature compared to CT + R. These results highlight the beneficial effects of conservation practices on crop growth and soil hydrothermal regime. The research demonstrates the effectiveness of the APSIM-Wheat model in precisely simulating crop growth and soil hydrothermal processes within the contexts of conservation agriculture. This highlights, its potential as a decision-support tool to enhance yield and water use efficiency, identify yield-limiting factors, and develop sustainable crop management plans, especially in the context of climatic change.

Data availability

Data generated from this research work will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AMP:

-

Annual amplitude in monthly temperature

- APSIM:

-

Agriculture production system simulator

- CA:

-

Conservation agriculture

- C:

-

Carbon

- CONA:

-

Second stage of soil evaporation

- CT + R:

-

Conventional tillage with residue incorporation

- D index:

-

Index of agreement

- DAS:

-

Days after sowing

- EC:

-

Electric conductivity

- FC:

-

Field capacity

- IGP:

-

Indo-Gangetic Plains

- KL:

-

Root water extraction coefficient

- LAI:

-

Leaf area index

- MBE:

-

Mean bias error

- MWMb:

-

Maize-wheat-mungbean

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- nRMSE:

-

Normalized root mean square error

- Oi:

-

Observed values

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- PWP:

-

Permanent wilting point

- R/I:

-

Rainfall/irrigation

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- SALB:

-

Soil albedo

- Si:

-

Simulated values

- SOC:

-

Soil organic carbon

- ST:

-

Soil temperature

- SWCON:

-

Layer drainage rate coefficient

- SWC:

-

Soil water content

- TAV:

-

Average ambient temperature

- Tmax:

-

Maximum air temperature

- Tmin:

-

Minimum air temperature

- U:

-

First stage of soil evaporation

- XF:

-

Root penetration parameter

- ZT + R:

-

Zero tillage with residue retention

References

Kassam, A., Friedrich, T. & Derpsch, R. Global spread of conservation agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 76, 29–51 (2018).

Fowler, R. & Rockström, J. Conservation tillage for sustainable agriculture: an agrarian revolution gathers momentum in Africa. Soil Tillage Res. 61, 93–108 (2001).

Bhan, S. & Behera, U. K. Conservation agriculture in India – Problems, prospects and policy issues. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2, 1–12 (2014).

Awada, L., Lindwall, C. W. & Sonntag, B. The development and adoption of conservation tillage systems on the Canadian Prairies. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2, 47–65 (2014).

Barron, J. Dry spell mitigation to upgrade semi-arid rainfed agriculture: Water harvesting and soil nutrient management for smallholder maize cultivation in Machakos, Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, Institutionen för systemekologi (2004).

Indoria, A. K., Rao, C. S., Sharma, K. L. & Reddy, K. S. Conservation agriculture – a panacea to improve soil physical health. Curr. Sci. 112, 52–61 (2017).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. Conservation agriculture effects on soil organic carbon accumulation and crop productivity under a rice–wheat cropping system in the western Indo-Gangetic Plains. Eur. J. Agron. 70, 11–21 (2015).

Jackson, T., Mansfield, K., Saafi, M., Colman, T. & Romine, P. Measuring soil temperature and moisture using wireless MEMS sensors. Measurement 41, 381–390 (2008).

Jahanfar, A., Drake, J., Sleep, B. & Gharabaghi, B. A modified FAO evapotranspiration model for refined water budget analysis for Green Roof systems. Ecol. Eng. 119, 45–53 (2018).

Keating, B. A. et al. An overview of APSIM, a model designed for farming systems simulation. Eur. J. Agron. 18, 267–288 (2003).

Asseng, S. et al. Performance of the APSIM-wheat model in Western Australia. Field Crops Res. 57, 163–179 (1998).

Meinke, H., Hammer, G. L., Van Keulen, H. & Rabbinge, R. Improving wheat simulation capabilities in Australia from a cropping systems perspective III. The integrated wheat model (I_WHEAT). Eur. J. Agron. 8, 101–116 (1998).

Rötter, R. P., Carter, T. R., Olesen, J. E. & Porter, J. R. Crop–climate models need an overhaul. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 175–177 (2011).

Dimes, J. P. & Revanuru, S. Evaluation of APSIM to simulate plant growth response to applications of organic and inorganic N and P on an Alfisol and Vertisol in India. ACIAR Proc. 1998, 118–125 (2004).

Timsina, J. & Humphreys, E. Applications of CERES-rice and CERES-wheat in research, policy and climate change studies in Asia: a review. Agric. Syst. 117, 315–369 (2006).

Bahri, H. et al. Assessing the long-term impact of conservation agriculture on wheat-based systems in Tunisia using APSIM simulations under a climate change context. Sci. Total Environ. 692, 1223–1233 (2019).

Briak, H. & Kebede, F. Wheat (Triticum aestivum) adaptability evaluation in a semi-arid region of Central Morocco using APSIM model. Sci. Rep. 11, 23173 (2021).

Kumar, U., Hansen, E. M., Thomsen, I. K. & Vogeler, I. Performance of APSIM to simulate the dynamics of winter wheat growth, phenology, and nitrogen uptake from early growth stages to maturity in Northern Europe. Plants 12, 986 (2023).

Tan, Y. et al. Application of APSIM model in winter wheat growth monitoring. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1500103 (2024).

Mohanty, M. et al. Soil carbon sequestration potential in a Vertisol in central India — results from a 43-year long-term experiment and APSIM modeling. Agric. Syst. 184, 102906 (2020).

Bana, R. S. et al. Identifying optimum residue levels for stable crop and water productivity and carbon sequestration under a conservation agriculture based rice–wheat system. Soil Tillage Res. 232, 105745 (2023).

Holzworth, D. P. et al. APSIM–evolution towards a new generation of agricultural systems simulation. Environ. Model. Softw. 62, 327–350 (2014).

Banerjee, K., Krishnan, P. & Mridha, N. Application of thermal imaging of wheat crop canopy to estimate leaf area index under different moisture stress conditions. Biosyst. Eng. 166, 13–27 (2018).

Banerjee, K., Krishnan, P. & Das, B. Thermal imaging and multivariate techniques for characterizing and screening wheat genotypes under water stress condition. Ecol. Indic. 119, 106829 (2020).

Balwinder-Singh, G. D., Humphreys, E. & Eberbach, P. L. Evaluating the performance of APSIM for irrigated wheat in Punjab. India. Field Crops Res. 124, 1–13 (2011).

Peake, A. S., Huth, N. I., Carberry, P. S., Raine, S. R. & Smith, R. J. Quantifying potential yield and lodging-related yield gaps for irrigated spring wheat in sub-tropical Australia. Field Crops Res. 158, 1–14 (2014).

Gaydon, D. S. et al. Evaluation of the APSIM model in cropping systems of Asia. Field Crops Res. 204, 52–75 (2017).

Farré, I., Robertson, M. J., Walton, G. H. & Asseng, S. Simulating phenology and yield response of canola to sowing date in Western Australia using the APSIM model. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 53, 1155–1164 (2002).

Chimonyo, V. G. P., Modi, A. T. & Mabhaudhi, T. Simulating yield and water use of a sorghum–cowpea intercrop using APSIM. Agric. Water Manag. 177, 317–328 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Modelling the effects of conservation tillage on crop water productivity, soil water dynamics and evapotranspiration of a maize–winter wheat–soybean rotation system on the Loess Plateau of China using APSIM. Agric. Syst. 166, 111–123 (2018).

Brown, H. E. et al. Plant modelling framework: software for building and running crop models on the APSIM platform. Environ. Model. Softw. 62, 385–398 (2014).

Garrido, A., Rey, D., Ruiz-Ramos, M. & Mínguez, M. I. Climate change and crop adaptation in Spain: consistency of regional climate models. Clim. Res. 49, 211–227 (2011).

Archontoulis, S. V., Miguez, F. E. & Moore, K. J. A methodology and an optimization tool to calibrate phenology of short-day species included in the APSIM PLANT model: application to soybean. Environ. Model. Softw. 62, 465–477 (2014).

Masikati, P., Manschadi, A., Van Rooyen, A. & Hargreaves, J. Maize–mucuna rotation: An alternative technology to improve water productivity in smallholder farming systems. Agric. Syst. 123, 62–70 (2014).

Archontoulis, S. V., Miguez, F. E. & Moore, K. J. Evaluating APSIM maize, soil water, soil nitrogen, manure, and soil temperature modules in the Midwestern United States. Agron. J. 106, 1025–1040 (2014).

Sidhu, H. S., Humphreys, E., Dhillon, S. S., Blackwell, J. & Bector, V. The Happy Seeder enables direct drilling of wheat into rice stubble. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 47, 844–854 (2007).

Singh, Y. H. S., Manpreet-Singh, E., Kukal, S. S. & Brar, N. K. Straw mulch, irrigation water and fertiliser N management effects on yield, water use and N use efficiency of wheat sown after rice. Permanent Beds Rice-Residue Manage. Rice-Wheat Syst. Indo-Gangetic Plain 7, 171 (2006).

Chakraborty, D. et al. Effect of mulching on soil and plant water status, and the growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in a semi-arid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 95, 1323–1334 (2008).

Saha, S. et al. Effect of tillage and residue management on soil physical properties and crop productivity in maize (Zea mays)–Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) system. Indian J. Agr. Sci. 80, 679–685 (2010).

Balwinder-Singh, E. H., Gaydon, D. S. & Eberbach, P. L. Evaluation of the effects of mulch on optimum sowing date and irrigation management of zero till wheat in central Punjab India using APSIM. Field Crops Res. 197, 83–96 (2016).

Chaki, A. K. et al. How we used APSIM to simulate conservation agriculture practices in the rice–wheat system of the Eastern Gangetic Plains. Field Crops Res. 275, 108344 (2022).

de Faria, R. T. & Madramootoo, C. A. Simulation of soil moisture profiles for wheat in Brazil. Agric. Water Manag. 31, 35–49 (1996).

Mohanty, H. K., Mahapatra, M. M., Kumar, P., Biswas, P. & Mandal, N. R. Modeling the effects of tool shoulder and probe profile geometries on friction stirred aluminum welds using response surface methodology. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 11, 493–503 (2012).

Keating, B. S., Meinke, H., Probert, M. E., Huth, N. I. & Hills, I. G. NWheat: documentation and performance of a wheat module for APSIM. Tropical Agriculture Technical Memorandum No. 9. (CSIRO Tropical Agriculture, Indooroopilly, Australia, 2001).

Connolly, R. D., Bell, M., Huth, N., Freebairn, D. M. & Thomas, G. Simulating infiltration and the water balance in cropping systems with APSIM-SWIM. Soil Res. 40, 221–242 (2002).

Liu, S. et al. Modelling crop yield, soil water content and soil temperature for a soybean–maize rotation under conventional and conservation tillage systems in Northeast China. Agric. Water Manag. 123, 32–44 (2013).

Monzón, J. P., Sadras, V. O. & Andrade, F. H. Fallow soil evaporation and water storage as affected by stubble in sub-humid (Argentina) and semi-arid (Australia) environments. Field Crops Res. 98, 83–90 (2006).

Choudhary, V. K., Kumar, P. S. & Bhagawati, R. Response of tillage and in situ moisture conservation on alteration of soil and morpho-physiological differences in maize under Eastern Himalayan region of India. Soil Tillage Res. 134, 41–48 (2013).

Busari, M. A., Kukal, S. S., Kaur, A., Bhatt, R. & Dulazi, A. A. Conservation tillage impacts on soil, crop and the environment. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 3, 119–129 (2015).

Campbell, G. S. Soil physics with BASIC: transport models for soil–plant systems (Elsevier, 1985).

Flerchinger, G. N., Sauer, T. J. & Aiken, R. A. Effects of crop residue cover and architecture on heat and water transfer at the soil surface. Geoderma 116, 217–233 (2003).

Rai, V. et al. Modelling soil hydrothermal regimes in pigeon pea under conservation agriculture using Hydrus-2D. Soil Tillage Res. 190, 92–108 (2019).

Liu, B., Zhou, W., Henderson, M., Sun, Y. & Shen, X. Climatology of the soil surface diurnal temperature range in a warming world: annual cycles, regional patterns, and trends in China. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002220 (2022).

Maity, P. Studies on thermal properties of soils and modeling of heat conduction under different soil management practices. PhD thesis, ICAR–Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi (2008).

Maity, P. & Aggarwal, P. Variation of thermal properties of sandy loam soil under different management practices. Indian J. Agr. Sci. 82, 181 (2012).

Zhang, X., Chen, S., Liu, M., Pei, D. & Sun, H. Improved water use efficiency associated with cultivars and agronomic management in the North China Plain. Agron. J. 97, 783–790 (2005).

Wilson, R. G. & Jasa, P. J. Ridge plant system: weed control (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension, 2007).

Dekker, L. W. & Ritsema, C. J. Effect of maize canopy and water repellency on moisture patterns in a Dutch black plaggen soil. Plant Soil 195, 339–350 (1997).

Johnson, M. D. & Lowery, B. Effect of three conservation tillage practices on soil temperature and thermal properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 49, 1547–1552 (1985).

Chauhan, Y. et al. Using APSIM-soiltemp to simulate soil temperature in the podding zone of peanut. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 47, 992–999 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE), Government of India, the Director of ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, for the facilities to conduct this research, the Graduate School IARI for granting Mr. Brijesh Yadav with a Research Fellowship, and ICAR-IIMR for assistance in conducting this long-term study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BY collected, analysed the data and manuscript writing; PK interpreted the data and manuscript writing; CMP conducted the experiment, KB collected the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, B., Krishnan, P., Parihar, C.M. et al. Modelling crop growth and soil hydrothermal regimes under conservation agriculture using APSIM-wheat. Sci Rep 15, 36362 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20211-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20211-6