Abstract

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and maintaining an undetectable maternal HIV viral load effectively prevent intrauterine and perinatal HIV transmission 1, 2. However, concerns remain regarding the safety of breastfeeding in infants exposed to maternal ART. This retrospective study analyzed eight breastfed HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants who were followed from January 2015 to July 2022. Maternal ART regimens included abacavir/lamivudine (n = 2), tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (n = 1) or tenofovirdisoproxil/emtricitabine (n = 5) in combinations with rilpivirine (n = 3) (RPV), dolutegravir (n = 2) (DTG), raltegravir (n = 1), darunavir/ritonavir (n = 1), or nevirapine (n = 1). Infants and mothers underwent sequential HIV-PCR testing, complete blood count, and ART drug monitoring in breast milk, infant serum, and maternal serum when available. The relative infant dose (RID) was calculated to assess drug exposure. Hematological parameters were compared with those of 62 HEU formula-fed infants from the same institution. No HIV transmission occurred. ART serum levels in breastfed infants varied significantly, with RPV and DTG levels above the adult target range in two cases. Notably, one infant had RPV levels exceeding the target RID by 633%, leading to cessation of breastfeeding. At four months, mean absolute neutrophil counts were lower in breastfed infants (1,130/µl) compared to formula-fed infants (2,000/µl), with the lowest individual absolute neutrophil counts in the formula-fed group. Despite ART levels above the adult target range in 3 infants, there was no consistent pattern between neutropenia and elevated ART levels. Our findings highlight the substantial variability in infant ART exposure during breastfeeding. Given this variability and the potential for drug accumulation in individual cases, maternal therapeutic drug monitoring should be considered to identify elevated levels early on. In such situations, infant monitoring tailored to the individual may also be warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In resource-rich settings with access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), strict adherence during pregnancy has resulted in a vertical transmission rate of less than 1% among mothers living with HIV (MLWH), provided their viral load is suppressed before birth1.

To reduce the risk of postpartum HIV infection through breastfeeding, recommendations in resource-rich settings with easy access to infant formula advise against initiating breastfeeding. In recent years, however, breastfeeding has been reported to be safe in single-center studies and case reports from Germany and Switzerland2,3,4. Based on the results of the IMPAACT PROMISE study, the German guideline for care of HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants was changed, supporting breastfeeding when the mother’s adherence to ART and successful ART are well documented5,6. A recent European survey of health workers revealed that while more MLWH are choosing to breastfeed, most national guidelines oppose it, and only less than half even address the option at all7.

Though breastfeeding likely promotes important health advantages for both the newborn and the mother, and the associated risk for HIV transmission appears very low, it remains unclear whether the amounts of different antiretroviral drugs transmitted through breast milk can impact on the infant’s health. In a systematic review from 2015, Waitt and colleagues showed that only relatively low levels of non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs) were transferred to the infants’ plasma8. Newer data from the Swiss Mother and Child HIV Cohort Study (MOCHIV) showed a highly variable level of transferred ARTs in the plasma of breast-fed infants2.

Studies from high-income countries indicate that HEU infants may face an increased risk of infections unrelated to HIV. While breastfeeding is known to offer general protective benefits, it is still unclear how exposure to ART during breastfeeding affects the infants’ vulnerability to these other infections9,10.

Here, we present data on ART exposure in a small, single-centre cohort of breastfed HEU infants and its implications for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM).

Methods

HIV-exposed infants were followed at the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Outpatient Clinic at the Department of General Pediatrics according to the current German and European guidelines for HIV-exposed or infected children6,11. MLWH were followed at the department of Infection Medicine, Medical Service Centre Clotten, Freiburg. The following provides a detailed overview of maternal ART regimens: Three mothers (infants 1, 6, and 7) received tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine 245/200 mg (TDF/FTC), and rilpivirine 25 mg (RPV) once daily. Two mothers (infants 2 and 4) were treated with dolutegravir 50 mg (DTG), abacavir 600 mg (ABC), and lamivudine 300 mg (3TC) once daily. The mother of infant 3 received tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine 25/200 mg (TAF/FTC) once daily in combination with nevirapine 200 mg (NVP) twice daily. The regimen for the mother of infant 5 included TDF/FTC 245 mg/200 mg and darunavir 800 mg boostered with ritonavir 100 mg (DRV/r), all administered once daily. The mother of infant 8 was treated with raltegravir 400 mg (RAL) twice daily and TDF/FTC 245/200 mg once daily.

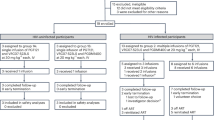

For all HIV-exposed children visits, clinical examinations and blood sampling took place at the age of one, four and 18 to 24 months. Additionally, breastfed infants were seen at 14 days of age and for bi-monthly exams until cessation of breastfeeding. Routine blood tests included blood cell counts with differentials, transaminases, bilirubin at the first presentation, HIV-PCR and at 18–24 months or after cessation of breastfeeding HIV serology was performed. Primary outcome was infant serum drug exposure; breast-milk concentrations served as supportive secondary data. Serum samples of mothers and infants were drawn during visits to our clinic. Neither the timing of maternal drug intake and breastfeeding, nor the timing of the blood samples, was standardized. Therefore, no pharmacokinetic calculations could be performed. When available, additional serum samples of infants or mothers and a breast milk sample were sent to the Drug monitoring laboratory, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine II, University of Würzburg Medical Center, Germany. Antiretroviral drug monitoring for rilpirivine (RPV), nevirapine (NVP), dolutegravir (DTG), raltegravir (RAL) and darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) was performed using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with ultraviolet detection (HPLC-UV) method modified from Charbe et al.12. NRTI concentrations were not measured, as their active forms are intracellular metabolites, which are not detectable with standard plasma-based assays. To assess the infant’s ART drug exposure upon breastfeeding, we calculated the relative infant dose (RID). The RID is a commonly used tool for assessing drug exposure and is calculated by dividing the infant’s ART level by the mother’s ART level, expressed as a decimal or percentage13,14. All information for this study was derived from routine clinical exams and was, when available, retrospectively extracted from the patients’ medical records. As a control group, HEU infants who were not breastfed during the time of January 2015 to June 2022 were included in the analysis. For analysis, the HEU children were divided in 2 groups: HEU breastfed infants (n = 8) and HEU formula-fed infants (n = 62). The retrospective analysis was approved and informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of the University of Freiburg (22-1073-retro). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Data collection and analysis were carried out in Microsoft Excel and R.

Results

Study population

In late 2018, the first MLWH decided to breastfeed her HEU infant. After one month, serum tests revealed RPV levels above the adult target range, which persisted at four months, prompting a recommendation to stop breastfeeding. Following this case, seven additional MLWH chose to breastfeed, and all eight mother-infant pairs were included in this analysis. Sixty-two HEU formula-fed infants seen at our clinic from January 2015 to July 2022 served as a control group for hematological parameters.

Infants 1 and 2 received zidovudine (ZDV) prophylaxis for four weeks. Infants 3–8 received two weeks of ZDV prophylaxis following the publication of new data indicating its safety and lower toxicity15. No HIV transmission was observed in any of the eight breastfed and sixty – two formula fed infants.

Transmission of maternal ART to infant serum

ART drug monitoring was available at some point for all eight HEU breastfed infants. Complete data on ART levels in breast milk, maternal serum and infant serum were available on 13 occasions (Table 1). The RID is used for clinical risk assessment, with a target RID of below 10% indicating a low risk of adverse drug reactions in infants16,17.

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)

RPV was measured in infants 1, 3, 6 and 7 and NVP in infant 7 (Table 1). In infant 1, maternal RPV levels were above the adult target range, corresponding to high serum levels at one and four months, with RIDs of 122% and 633%, respectively. Following cessation of breastfeeding, the infant’s serum levels fell below the detectable range by six months. In infants 6 and 7, the RPV serum levels were consistently below the range of detection, preventing accurate calculation of the RID, but allowing the assumption that the target RID was achieved. The RID for nevirapine in infant 3 was increased at 180% and 171% at 1 month and 4 months of age, respectively.

Integrase inhibitors (INI)

Infants 2 and 4 were exposed to DTG and infant 8 to RAL. In infant 2, serum DTG levels were above the target RID, with an RID of 240% at 4 months, despite maternal DTG levels being within the therapeutic range. In infant 4, DTG levels were consistently below the detectable range, resulting in a target RID of < 10%. In infant 8, the levels of RAL in the mother’s serum and breast milk were both in the adult target range. Correspondingly, the infant’s serum RAL levels remained below the detectable range, resulting in a target RID of < 10%.

Protease inhibitors (PI)

Infant 5 was exposed to DRV/r. The infant’s serum DRV/r levels were always below detectable levels, corresponding to an RID < 1%. Maternal DRV/r levels were in the adult target range on all occasions.

Transmission of maternal ART to breast milk

Drug concentrations were measurable in seven out of 15 (47%) breast milk samples (Table 1). Five of the values fell within the adult trough range: DTG (648 and 680 ng/ml), RAL (293 and 168 ng/ml), and RPV (63 ng/ml). Two exceeded the upper trough limit: RAL at 14 days (1,757 ng/ml) and RPV at four months (4,300 ng/ml). The remaining eight samples were below the assay detection limits (50 ng/ml for NNRTI/INI and 250 ng/ml for PI).

Alteration of hematological parameters in HEU infants

Complete and differential blood counts were analyzed in both HEU breastfed (n = 8) and formula-fed (n = 62) infants. Cases of cytopenia were observed in both groups. Given that all infants received ZDV prophylaxis, these findings may reflect known hematologic side effects of ZDV.

Additional ART exposure through breastfeeding could contribute to further cytotoxic effects. However, due to the small sample size and variability in ART regimens and serum levels, no consistent pattern between ART exposure and hematological changes can be concluded. Detailed neutrophil count comparisons are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1, and corresponding ART serum levels with neutrophil counts are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Comparisons of hemoglobin, thrombocyte, and leukocyte counts are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Discussion

Encouraging breastfeeding among MLWH in high-resource settings is a relatively recent development. Switzerland introduced this approach with its 2018 guideline revision, followed by Germany’s update in September 2020. The updated guidelines reduced barriers and provided clearer recommendations for both healthcare providers and patients.

In our cohort of eight breastfed and 62 formula-fed HEU infants, no cases of perinatal or postnatal HIV transmission occurred. This finding is consistent with other studies of breastfed HEU infants in resource-rich settings with good access to ART2,18,19.

Given the substantial evidence on the low risk of HIV transmission through breastmilk20,21,22, this information can be provided when counselling MLWH on their breastfeeding decision. However, when MLWH inquire about the impact of continued ART exposure by breastfeeding, data remain limited.

Pregnant women are strongly advised to take ART during pregnancy, making in utero exposure to these drugs inevitable. It is crucial to understand that during pregnancy, drug exposure (i.e., serum levels) in both the mother and the child is primarily influenced by maternal drug metabolism and excretion rates rather than those of the fetus. After birth, this dynamic changes, as the infant no longer relies on maternal metabolic capacity. This can result in cases where infant serum levels exceed those found in breast milk or maternal serum, as shown in mother-infant pairs 1 and 2 of this study.

ART levels can be elevated in breast milk, as observed for mother – infant pairs 1 and 8, leading to potentially higher uptake in infants compared to in utero. Drug metabolism in infants depends on glomerular filtration rates and metabolic enzyme activity, both of which can be lower than in adults13,23. Additionally, the duration of breastfeeding can vary significantly and may exceed the typical nine months of pregnancy. Consequently, the combination of drug accumulation in breast milk, reduced drug metabolism in infants, and extended breastfeeding may result in higher drug exposure than during pregnancy. This risk applies to a wide range of drugs, and drug-specific research in infants is limited due to ethical challenges.

The RID is a commonly used tool for assessing infant drug exposure during breastfeeding, with a threshold level below 10% generally assumed to confer little risk of side effects16,17. However, it should be emphasized that for most ART the evidence for this assumption is limited and that, consecutively, RID levels below or above 10% should not be automatically deemed safe or unsafe, respectively.

In the absence of robust and clear evidence, the effects of ART on the breastfed infant need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks, while avoiding unnecessary interruptions to breastfeeding.

Previous reports have also documented elevated levels of NVP in breastfed HEU infants24,25. Neutropenia is a rare side effect of NVP in children, and it can occur spontaneously in infants without identifiable risk26. Notably, infant 3 did not show neutropenia despite elevated NVP levels. RPV concentrations in Infant 1 were markedly elevated, with an RID of 633%, coinciding with maternal serum and breast milk levels well above the adult therapeutic range. Such supratherapeutic RPV concentrations could be due to unrecorded pharmacokinetic modifiers, most likely strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or agents that decrease gastric pH and enhance the absorption of RPV. However, our retrospective dataset lacks details of concomitant medications, preventing a definitive explanation. By contrast, Infant 7, whose mother’s RPV levels remained within the therapeutic window, exhibited minimal infant exposure (RID < 10%). These observations suggest a direct relationship between maternal serum RPV levels and infant exposure. Both RPV and NVP are highly lipophilic and readily transfer into breast milk, as we and other researchers have shown2. Their metabolism primarily depends on CYP3A4, an enzyme with significantly reduced activity in neonates and young infants27. While therapeutic maternal levels may be handled effectively by this limited enzymatic capacity, elevated maternal concentrations could exceed the infant’s metabolic clearance, thereby increasing the risk of drug accumulation.

The integrase inhibitors DTG and RAL are moderately lipophilic compounds capable of crossing biological membranes and entering breast milk. The elevated DTG levels in Infant 2 may reflect delayed metabolic clearance due to age-dependent activity of UGT1A1, a crucial enzyme responsible for integrase inhibitor glucuronidation. UGT1A1 reaches adult glucuronidation activity within the first few months after birth. However, this activity can vary between infants28,29, potentially accounting for the elevated DTG levels observed by us and others30. Although RAL is also metabolised via UGT1A1, no detectable infant serum levels were observed in Infant 8, despite elevated maternal and breast milk concentrations. This may reflect individual metabolic differences.

The low infant serum concentrations of DRV/r, as seen in Infant 5, are consistent with previous reports indicating poor transfer of protease inhibitors into breast milk31,32. Although DRV/r is lipophilic, its high plasma protein binding and possible efflux via breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)25 - which transports substrates into breast milk33 - may limit its transfer.

Unlike HIV-infected adults, who benefit from ART through improved neutrophil counts and haematopoietic recovery, HEU infants have immune systems that are still maturing and may be altered by perinatal ART exposure. The long-term effects of such exposure during critical periods of immune development are not fully understood. Simultaneously, all infants in our study received the recommended ZDV prophylaxis, which is known to cause transient cytopenias. These hematologic changes may mask or confound potential toxicities from other ART agents. Integrase inhibitors, such as DTG and RAL, are considered low risk for direct cytotoxicity but may influence neutrophil function through interaction with RAG1, a gene expressed in neutrophils34,35. Protease inhibitors, such as DRV/r, exhibit anti-apoptotic as well as inhibitory effects on neutrophils, depending on intracellular accumulation and drug concentration35. In both cases interference with immunedevelopment is plausible, yet the clinical relevance of this remains uncertain.

Recent changes to the German guidelines have reduced the recommended duration of neonatal prophylaxis from four weeks to two, and the omission of ZDV prophylaxis is permitted in selected cases. This presents an opportunity to monitor hematological outcomes in the absence of ZDV and to better delineate the potential effects of ART exposure via breastfeeding in the future.

Our findings emphasize the potential importance of TDM in ART exposure during breastfeeding. Current guidelines in high-income countries like Germany or the United Kingdom state that routine HIV-PCR monitoring is mandatory for mother and child; however, TDM is not mentioned. This study does not establish causal links or toxicity thresholds. However, highly elevated infant ART levels suggest that maternal TDM may be justified in select cases - particularly for lipophilic drugs such as RPV and DTG.

Maternal TDM can be integrated into routine viral load assessments with minimal additional burden. Meanwhile, infant TDM poses more challenges due to limited blood volume and sampling feasibility. As significant accumulation was observed in only one infant, routine infant TDM cannot be widely recommended based on the limited available data. However, it should be considered when maternal serum levels are elevated or when clinical symptoms suggest toxicity. If clinically relevant infant drug levels are confirmed, temporary cessation of breastfeeding should be considered. Nevertheless, given the lack of evidence, we strongly recommend that such a decision is not based solely on ART levels, but also on the infant’s clinical appearance, as well as the mother’s needs and wishes.

Another interesting aspect for future research is whether drug levels in breast milk can be a reliable predictor of infant serum levels, thereby providing a non-invasive monitoring option in cases where no blood samples are taken or blood volume is insufficient. However, our study found that low breast milk ART levels did not consistently predict serum levels, as seen with DTG. Whether this holds true for other ARTs remains to be investigated.

It is important to note that the observed serum levels in this study were affected by variable timing of drug intake, breastfeeding and sample collection. Unlike in a controlled pharmacokinetic study, clinical practice rarely allows for the precise coordination of these factors. Unlike medication intake, breastfeeding follows the child’s needs rather than a fixed schedule, and blood draws depend on appointment availability. Consequently, the drug levels measured here reflect real-life variability. These limitations must be considered when interpreting individual serum concentrations. Nevertheless, when maternal TDM is performed, we strongly recommend documenting the timing of drug intake relative to sample collection to improve the reliability of result interpretation.

Further limitations include the reliance on single-point measurements and missing data presents challenges in interpreting ART exposure and its effects. In most cases, information on infant vaccination dates, birth height and weight percentiles, gestational age at birth, co-medications (other than vitamin D), and parental ethnicity was unavailable. Third, specialised assays to detect intracellular NRTIs were unavailable, so these data are absent. Further studies should address the transfer of NRTIs and the related risk of toxicity.

Despite these limitations, the strengths of the study include the examination of multiple ART regimens, offering a broad view of how different ARTs may impact breastfed infants. This diversity of ART exposure provides valuable insights into the pharmacokinetics and safety of breastfeeding while on ART for MLWH.

Conclusions

Our findings emphasize the complexity of antiretroviral drug exposure during breastfeeding, as well as the significant variability in infant drug levels between individuals. Infants with ART levels above the 10% RID highlight the need for personalized monitoring. Due to current limitations in the available data, maternal TDM, particularly for drugs with high lipophilicity or long half-lives, may help to identify risk constellations at an early stage. Future research should focus on defining actionable exposure thresholds for infants, optimizing non-invasive monitoring tools and clarifying the long-term outcomes of ART exposure during breastfeeding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sibiude, J. et al. Update of Perinatal Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Transmission in France: Zero Transmission for 5482 Mothers on Continuous Antiretroviral Therapy From Conception and With Undetectable Viral Load at Delivery. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76(3), e590–e598 (2023).

Aebi-Popp, K. et al. Transfer of antiretroviral drugs into breastmilk: a prospective study from the Swiss Mother and Child HIV Cohort Study. J Antimicrob Chemother 77(12), 3436–3442 (2022).

Kobbe, R. et al. Dolutegravir in breast milk and maternal and infant plasma during breastfeeding. AIDS 30(17), 2731–2733 (2016).

Haberl, L. et al. Not Recommended, But Done: Breastfeeding with HIV in Germany. AIDS Patient Care STDS 35(2), 33–38 (2021).

Flynn, P. M. et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission Through Breastfeeding: Efficacy and Safety of Maternal Antiretroviral Therapy Versus Infant Nevirapine Prophylaxis for Duration of Breastfeeding in HIV-1-Infected Women With High CD4 Cell Count (IMPAACT PROMISE): A Randomized, Open-Label, Clinical Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 77(4), 383–392 (2018).

Behrens, G. Deutsch-Österreichische Leitlinie zur HIV-Therapie in der Schwangerschaft und bei HIVexponierten Neugeborenen. Available from: URL: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/055-002l_S2k_HIV-Therapie-Schwangerschaft-und-HIV-exponierten_Neugeborenen_2020-10-verlaengert.pdf

Keane, A. et al. Guidelines and practice of breastfeeding in women living with HIV-Results from the European INSURE survey. HIV Med 25(3), 391–397 (2024).

Waitt, C. J., Garner, P., Bonnett, L. J., Khoo, S. H. & Else, L. J. Is infant exposure to antiretroviral drugs during breastfeeding quantitatively important? A systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacokinetic studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 70(7), 1928–1941 (2015).

Manzanares, Á. et al. Increased risk of group B streptococcal sepsis and meningitis in HIV-exposed uninfected infants in a high-income country. Eur J Pediatr 182(2), 575–579 (2023).

Afran, L. et al. HIV-exposed uninfected children: a growing population with a vulnerable immune system?. Clin Exp Immunol 176(1), 11–22 (2014).

EACS Guidelines. Available from: URL: (2023). https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-12.0.pdf

Charbe, N. et al. Development of an HPLC-UV assay method for the simultaneous quantification of nine antiretroviral agents in the plasma of HIV-infected patients. J Pharm Anal. 6(6), 396–403 (2016).

Cardoso, E. et al. Maternal drugs and breastfeeding: Risk assessment from pharmacokinetics to safety evidence - A contribution from the ConcePTION project. Therapie 78(2), 149–156 (2023).

Verstegen, R. H. J., Anderson, P. O. & Ito, S. Infant drug exposure via breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 88(10), 4311–4327. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14538 (2022).

Nguyen, T. T. T. et al. Reducing hematologic toxicity with short course postexposure prophylaxis with Zidovudine for HIV-1 exposed infants with low transmission risk. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 38 (7), 727–730 (2019).

Anderson, P. O. & Sauberan, J. B. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 100(1), 42–52 (2016).

Larsen, E. R. et al. Use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Psychiatr Scand Suppl 132(445), 1–28 (2015).

Weiss, F. et al. Brief report: HIV-Positive and breastfeeding in High-Income settings: 5-Year experience from a perinatal center in Germany. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 91 (4), 364–367 (2022).

Levison, J. et al. Breastfeeding Among People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in North America: A Multisite Study. Clin Infect Dis 77(10), 1416–1422 (2023).

Iliff, P. J. et al. Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. AIDS 19(7), 699–708 (2005).

Coovadia, H. M. et al. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. The Lancet 369(9567), 1107–1116 (2007).

Miotti, P. G. et al. HIV transmission through breastfeeding: a study in Malawi. JAMA 282 (8), 744–749 (1999).

Ginsberg, G. et al. Evaluation of child/adult pharmacokinetic differences from a database derived from the therapeutic drug literature. Toxicol Sci. 66(2), 185–200 (2002).

Pressiat, C. et al. High nevirapine levels in breast milk and consequences in HIV-infected child when initiated on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 35(14), 2409–2410 (2021).

Musoke, P. et al. A phase I/II study of the safety and pharmacokinetics of nevirapine in HIV-1-infected pregnant Ugandan women and their neonates (HIVNET 006). AIDS 13(4), 479–486 (1999).

Pollard, R. B., Robinson, P. & Dransfield, K. Safety profile of nevirapine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin. Ther. 20 (6), 1071–1092 (1998).

Robinson, J. F., Hamilton, E. G., Lam, J., Chen, H. & Woodruff, T. J. Differences in cytochrome p450 enzyme expression and activity in fetal and adult tissues. Placenta 100, 35–44 (2020).

Miyagi, S. J. & Collier, A. C. The development of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A1 and 1A6 in the pediatric liver. Drug Metab Dispos 39(5), 912–919 (2011).

Badée, J. et al. Characterization of the Ontogeny of Hepatic UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Enzymes Based on Glucuronidation Activity Measured in Human Liver Microsomes. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59, S42–S55 (2019).

Dickinson, L. et al. Infant Exposure to Dolutegravir Through Placental and Breast Milk Transfer: A Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of DolPHIN-1. Clin Infect Dis 73(5), e1200–e1207 (2021).

Olagunju, A. et al. Breast milk pharmacokinetics of efavirenz and breastfed infants’ exposure in genetically defined subgroups of mother-infant pairs: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis 61(3), 453–463 (2015).

Marzolini, C. & Gray, G. E. Maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis and breastfeeding. Antivir Ther 17(8), 1503–1506 (2012).

Jonker, J. W. et al. The breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) concentrates drugs and carcinogenic xenotoxins into milk. Nat Med 11(2), 127–129 (2005).

Nilavar, N. M. & Raghavan, S. C. HIV integrase inhibitors that inhibit strand transfer interact with RAG1 and hamper its activities. Int. Immunopharmacol. 95, 107515 (2021).

Madzime, M., Rossouw, T. M., Theron, A. J., Anderson, R. & Steel, H. C. Interactions of HIV and antiretroviral therapy with neutrophils and platelets. Front. Immunol. 12, 634386 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their colleagues at PAAD e.V. and DAIG e.V. for insightful discussions of the study results. The technical assistance of Mrs. Ulrike Lenker in the drug monitoring laboratory is thankfully acknowledged.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Theodor-Escherich-Prize from the German Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases to Dr. Spielberger. Dr. Spielberger also received a research grant from Gilead Sciences. The data of this manuscript however was generated before the Gilead Sciences grant was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS, JR, MM and SU conceived the study. BS and MH obtained the ethics approval. BS, AZ, JR, MM, and SU collected and analyzed the data. HK contributed pharmacokinetic data. BS, JR, MF, RE, PH and MH examined pediatric patients, SU, SR and MM examined the mothers. BS and AZ were the principal writers of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spielberger, B.D., Zink, A., Rohr, J.C. et al. Breastfeeding on ART and a closer look at drug transfer to HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Sci Rep 15, 32612 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20259-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20259-4